Abstract

The attachment of calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM) crystals to renal tubules is thought to be one of the critical steps of kidney stone formation. Patterns of phosphatidylserine (DPPS) bilayers and osteopontin (OPN) were fabricated on silica substrates through a combination of micro-contact printing technique and fusion of lipid vesicles to create spatially organized surfaces of lipids and proteins that may mimic renal tubule surfaces while allowing direct visualization of the competition for COM attachment to compositionally different regions. In the case of DPPS-OPN patterns, micron-sized COM crystals dispersed in saturated aqueous calcium oxalate solutions attached preferentially to the OPN regions, in agreement with other in vitro studies that have suggested a binding affinity of OPN to COM crystal surfaces. COM crystals attached with nearly equal coverage to OPN and DPPS surfaces alone, suggesting that the preferential segregation of COM crystals to the OPN regions on the patterned surfaces reflects reversible attachment of micron-sized COM crystals capable of Brownian motion. These attached microcrystals then grow larger over time during immersion in the supersaturated calcium oxalate solutions. Free OPN, a major constituent in urine, adsorbs on COM crystals and suppresses attachment to DPPS, suggesting a link between OPN and reduced attachment of COM crystals to renal epithelium. This patterning protocol can be expanded to other urinary molecules, providing a convenient approach to ranking the effects of biomolecules on COM crystal attachment and the pathogenesis of kidney stones.

Graphical Abstract

The primary constituent of kidney stones in patients with urolithiasis is calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM).1 Previous investigations have suggested that osteopontin (OPN), a urinary protein with substantial anionic character, is a potent inhibitor of COM crystallization.2 In vitro studies revealed that renal cell membrane and renal brush-border membrane vesicles are involved in crystallization of calcium oxalate, suggesting that lipids also play a critical role in kidney stone formation.3 Reports of COM nucleation and growth on self-assembled lipid monolayers reveal that the negatively-charged phosphatidylserine (PS) interface is a strong promoter of COM crystallization.4 Understanding the effects of urinary proteins and lipids among other biomolecules on COM crystallization is essential for determining their roles in stone formation and unraveling the mechanism of stone formation.

The attachment of COM crystals to renal tubules is one of four critical steps of stone formation (nucleation, attachment, growth and aggregation). OPN has been suggested to play a role in stimulating adhesion of crystals to cells in the early stages of urolithiasis,5 but OPN also has been suggested to suppress crystal attachment to cell membranes due to repulsive interactions between anionic sidechains on OPN adsorbed on crystal surfaces and renal tubular cell surface receptors, which contain anionic phospholipids, sialic acid containing glycoproteins, and hyaluronan.6 Consequently, the role of OPN in COM crystal attachment to cell membrane remains unclear. Langmuir monolayer, surfactants, and vesicles have been used as model systems to study the formation of calcium oxalate stones.3,4,7 These systems, however, do not always capture the structure of the fluidic cellular membrane in the presence of other biomolecules, particularly if spatial organization and competitive binding among various binding sites, including protein adsorbed on either crystal or epithelial surfaces, is an important factor. Herein we describe a methodology based on patterned surfaces that enables direct comparison of the affinity of COM crystals for 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DPPS) bilayers and OPN, which reveals that OPN binds strongly to COM as well as a diminished affinity of OPN when OPN is adsorbed on the COM surfaces.

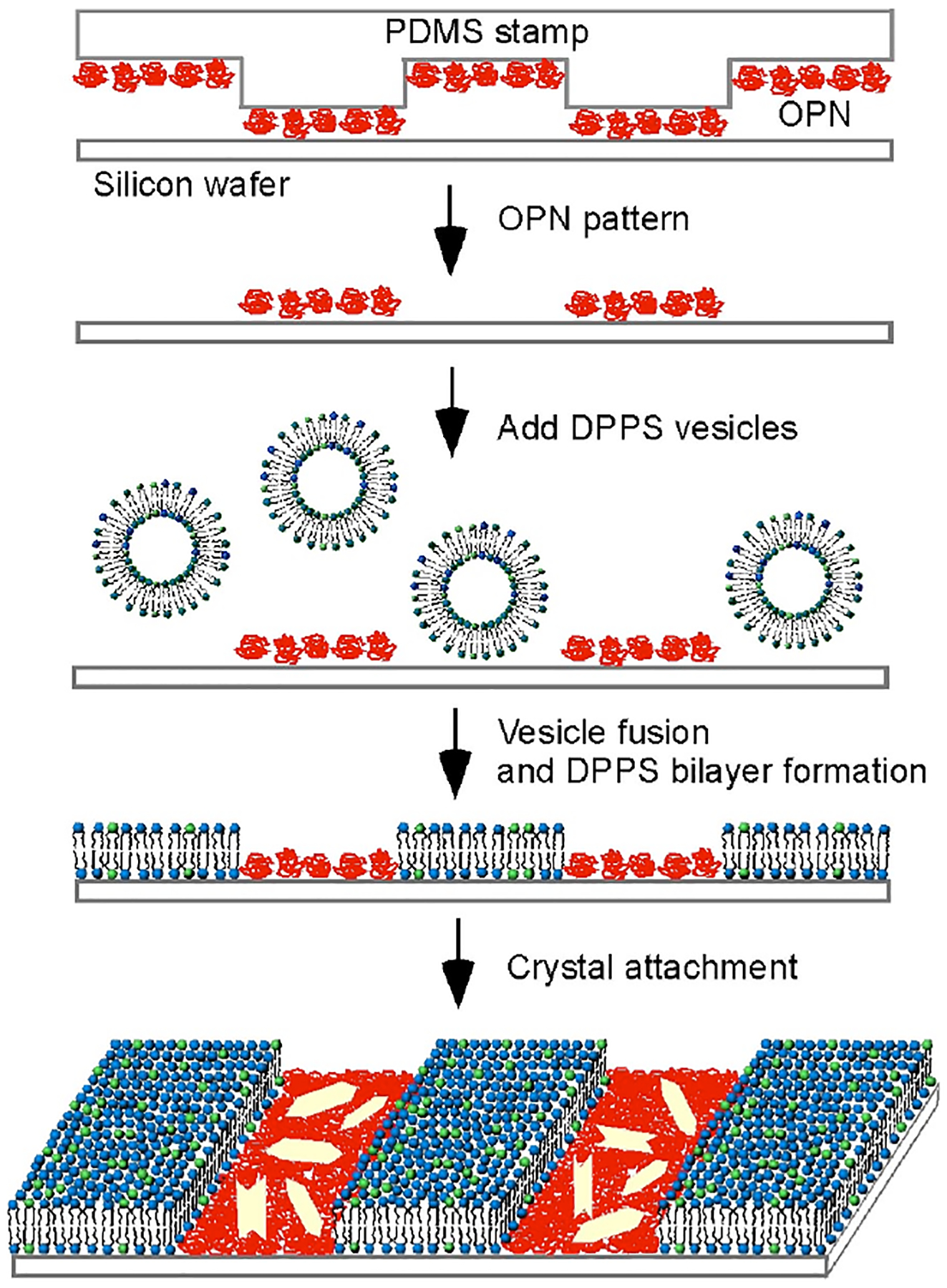

Patterned surfaces of DPPS bilayers and OPN were created through a combination of micro-contact printing8 and fusion of lipid vesicles,9a a protocol that has been used for the fabrication of patterned surfaces of phosphatidylcholine bilayers and bovine serum albumin.9b Micron-wide grids or stripes of OPN, labeled with Texas Red, were prepared on a silicon wafer using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps fabricated by standard photolithography methods. Subsequent exposure of the OPN patterned surface to unilamellar vesicles comprising DPPS and 2 mol% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-carboxyfluorescein (DOPE-CF) generated lipid bilayer membranes in corrals surrounded by the existing OPN grids through fusion on the bare regions of the substrate (Figure 1). Excess vesicles and weakly bound protein were then removed by thorough rinsing with water.

Figure 1.

Scheme for attachment of COM crystals to DPPS-OPN patterned surface.

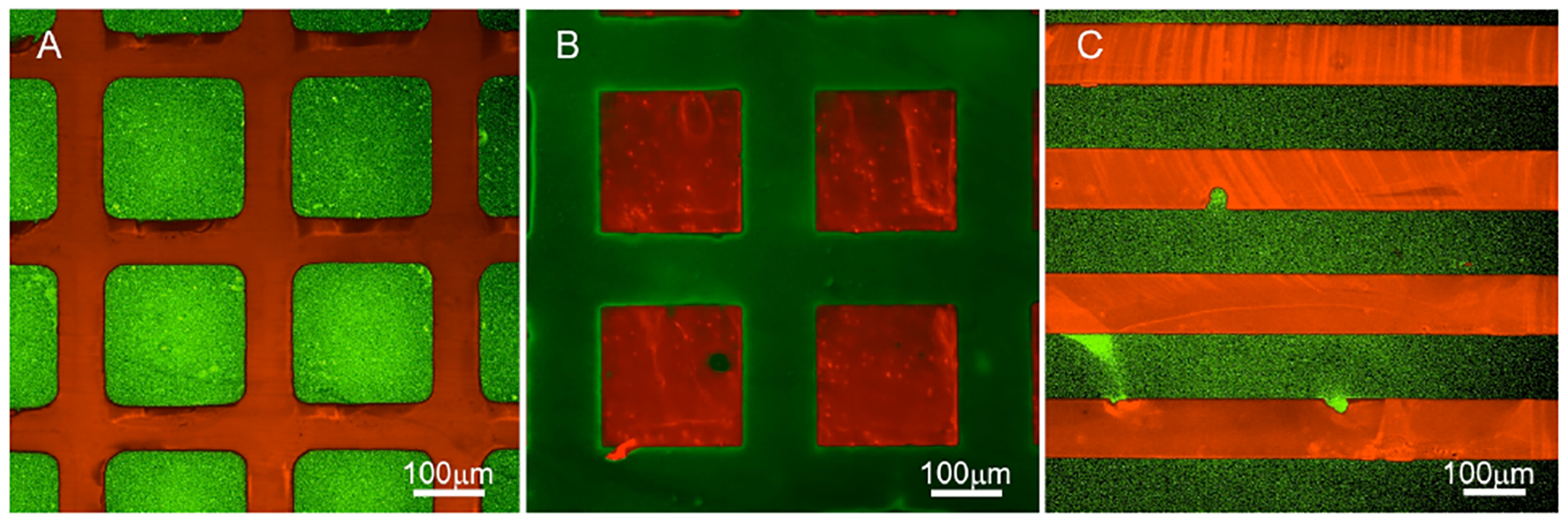

The fidelity of the DPPS-OPN pattern formation was confirmed by epifluorescence microscopy, which revealed the carboxyfluorescein chromophore (green) in lipid regions and the Texas Red chromophore (red) in the OPN regions (Figure 2). Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of OPN patterns alone on silicon revealed that the height of the OPN gridlines was approximately 2 nm with respect to the underlying surface (Figure S1). This measurement, which is consistent with a single layer of immobilized OPN molecules, confirms the persistence and integrity of the printed OPN regions.

Figure 2.

Epifluorescence of DPPS-OPN patterned surfaces. The DPPS bilayer is labeled with 2% DOPE-CF (green) and OPN with Texas Red. (A) 200 μm squares of DPPS bordered by 70 μm-wide grids of OPN. (B) 200 μm squares of OPN bordered by 100 μm-wide grids of DPPS. (C) 100 μm-wide alternating stripes of DPPS and OPN.

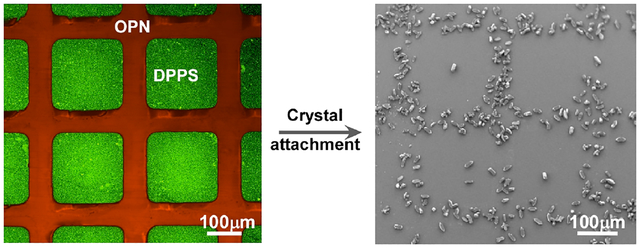

COM crystal attachment to DPPS and OPN was investigated by immersion of a patterned silicon wafer in an aqueous solution containing 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM calcium oxalate (relative supersaturation σ = 5) at 60°C contained in a sealed reservoir. This temperature was chosen in order to maintain the DPPS bilayer in a fluid state (solid-fluid phase transition temperature of DDPS is Tm = 54° C). Circular dichroism of OPN solutions revealed no detectable change in protein conformation. The wafer was immersed in a vertical orientation to avoid gravitational settling of crystals. After 24 hours the wafer was removed from the reservoir, and optical microscopy revealed selective attachment of COM crystals to the OPN regions (Figure 3), independent of pattern dimensions and configuration (i.e., stripes or grids). Additional investigations revealed that attachment of the COM crystals actually occurred immediately upon immersion, with segregation of COM crystals on the OPN regions becoming clearly distinct after 60 minutes (Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Optical microscopy images of the crystals attached to OPN regions on DPPS-OPN patterned surface depicted in Figure 2.

The size of COM crystals attached to the OPN regions increased with substrate immersion time. At the early stages (~ 2 min), the COM crystals attached to the OPN regions measure, on average, 3 μm in length. These attached crystals grow to nearly 6 μm after 60 min (Figure S2) and 10–20 μm after 24 hours (Figure S3). COM crystals collected from fresh 1mM CaOx solutions measured ~3 μm in length (Figure S4A), suggesting that the crystals observed on the OPN regions attached as mature crystals, migrating to these regions through Brownian motion,10 rather than growing from nuclei that had formed preferentially on OPN. The increase in size of the attached crystals at longer immersion times was consistent with the sizes of crystals harvested from the solution at periodic intervals (Figure S3 and S4B).

Interestingly, under the same conditions used for the patterned substrates, COM crystals attached with equal coverage to a bare silicon wafer, and wafers coated with OPN or DPPS alone (Figure S5). These observations suggest reversible binding of COM microcrystals at the early stages, coupled with Brownian motion, resulting in preferred segregation of the crystals on the OPN regions. The unique binding preference of COM for OPN is revealed further by uniformly dispersed COM crystals on patterns of human serum albumin (HSA) and the DDPS bilayer (Figure S6).

Previous reports have revealed that OPN influences the adhesion characteristics of the (100) face,11a reduces the growth rate of the (010) face,12 and alters the crystal habit through binding at edges adjoining the {100} and {121} faces, all consistent with adsorption of OPN on COM.13 As expected, the immobilized OPN does not affect the crystal habit or growth rate (compared to solution), but the crystals appear to attach to the OPN regions predominantly through the (100) face, which is consistent with previous observations that this face is the most adhesive toward anionic species.11b

In order to examine the role of free OPN (in solution) on COM crystal attachment to DPPS, a silicon wafer coated with a DPPS bilayer alone was immersed in the same growth medium as above but with 5 μg/ml OPN. This resulted in fewer COM crystals on the DPPS bilayer than in the absence of free OPN (Figure S7), consistent with electrostatic repulsion between anionic OPN adsorbed on COM and the negatively charged DPPS bilayer. As DPPS can be regarded as a mimic of a cell membrane, this observation suggests that the inhibition of COM stone formation by free OPN is associated with suppressed attachment of crystals to renal epithelial cell membranes.6 The attached COM crystals also were smaller (~5 μm) in the presence of free OPN, consistent with the COM crystal growth inhibition by OPN observed in vitro. The attached crystals also exhibited the well-documented dumbbell habit in the presence of free OPN.

The preferential attachment of COM crystals to the OPN regions of DPPS-OPN patterned surfaces illustrates that OPN is more competitive for crystal attachment than DPPS. Moreover, these experiments demonstrate that free OPN, which is a major constituent in urine, adsorbs on COM crystals and suppresses attachment to DPPS, suggesting a link between OPN and reduced attachment of COM crystals to renal epithelium. Although the studies presented here are limited to surface-confined DPPS and OPN, this patterning protocol may provide a convenient approach to understanding the effects of other biomolecules, either alone or integrated with DPPS bilayers, on COM crystal attachment and the pathogenesis of kidney stones.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (NIDDK R01-DK068551) and the NYU Molecular Design Institute.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experiment details of COM crystallization on hybrid surfaces and characterization of hybrid surfaces and crystals. This materials is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Mandel NS; Mandel GS J. Urol 1989, 142, 1516–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Herring LC J. Urol 1962, 88, 545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wesson JA; Johnson RJ; Mazzali M; Beshensky AM; Stietz S; Giachelli C; Liaw L; Alpers CE; Couser WG; Kleinman JG; Hughes JJ Am. Soc. Nephrol 2003, 14, 139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fasano JM; Khan SR Kidney Int. 2001, 59, 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talham DR; Backov R; Benitez IO; Sharbaugh DM; Whipps S; Khan SR Langmuir 2006, 22, 2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Yamate T; Kohri K; Umekawa T; Amasaki N; Isikawa Y; Iguchi M; Kurita T Eur. Urol 1996, 30, 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamate T; Kohri K; Umekawa T; Iguchi M; Kurita TJ Urol. 1998, 160, 1506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Asplin JR; Arsenault D; Parks JH; Coe FL; Hoyer JR Kidney Int. 1998, 53, 194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kumar V; Farell G; Lieske JC J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 2002, 13, 388A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lieske JC; Huang E; Toback FG Am. J. Physiol 2000, 278, F130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tunika L; Addadi L; Gartia N; Füredi-Milhofera HJ Cryst. Growth 1996, 167, 748. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia YN; Tien J; Qin D; Whitesides GM Langmuir 1996, 12, 4033. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Sackmann E Science 1996, 271, 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kung LA; Kam L; Hovis JS; Boxer SG Langmuir 2000, 16, 6773–6776. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma V; Park K; Srinivasarao M Mat. Sci. & Eng. R 2009, 65, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Sheng XX; Jung TS; Wesson JA; Ward MD Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2005, 102, 267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sheng X; Ward MD; Wesson JA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Jung T; Sheng XX; Choi CK; Kim WS; Wesson JA; Ward MD Langmuir 2004, 20, 8587–8596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Qiu SR; Wierzbicki A; Orme CA; Cody AM; Hoyer JR; Nancollas GH; Zepeda S; De Yoreo JJ Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2004, 101, 1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taller A; Grohe B; Rogers KA; Goldberg HA; Hunter GK Biophysical J. 2007, 93, 1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.