Abstract

Humanin (HN) is a mitochondrial-derived peptide that protects many cells/tissues from damage. We previously demonstrated that HN reduces stress-induced male germ cell apoptosis in rodents. HN action in neuronal cells is mediated through its binding to a trimeric cell membrane receptor composed of glycoprotein 130 (gp130), IL-27 receptor subunit (IL-27R, also known as WSX-1/TCCR), and ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor subunit (CNTFR). The mechanisms of HN action in testis remain unclear. We demonstrated in ex-vivo seminiferous tubules culture that HN prevented heat-induced germ cell apoptosis was blocked by specific anti-IL-27R, anti-gp130, and anti-EBI-3, but not by anti-CNTFR antibodies significantly. The cytoprotective action of HN was studied by using groups of il-27r−/− or ebi-3−/− mice administered the following treatment: (1) vehicle; (2) a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of HN peptide; (3) testicular hyperthermia; and (4) testicular hyperthermia plus HN. We demonstrated that HN inhibited heat-induced germ cell apoptosis in wildtype but not in il-27r−/− or ebi-3−/− mice. HN restored heat-suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation in wildtype but not il-27r−/− or ebi-3−/− mice. Dot blot analyses showed the direct interaction of HN with IL-27R or EBI-3 peptide. Immunofluorescence staining showed the co-localization of IL-27R with HN and gp130 in Leydig cells and germ cells. We conclude that the anti-apoptotic effects of HN in mouse testes are mediated through interaction with EBI-3, IL-27R, and activation of gp130, whereas the role of CNTFR needs further studies. This suggests a multicomponent tissue-specific receptor for HN in the testis and links HN action with the IL-12/IL-27 family of cytokines.

Keywords: humanin, spermatogenesis, apoptosis, EBI-3, IL-27Rα, STAT3, humanin-receptor, signal transduction, mouse

The cytoprotective effects of HN in mouse testes are mediated via binding with EBI-3, IL-27R, and activation of gp130. This suggests there is a multicomponent tissue-specific HN receptor in the testis and links HN with the IL-12/IL-27 family of cytokines.

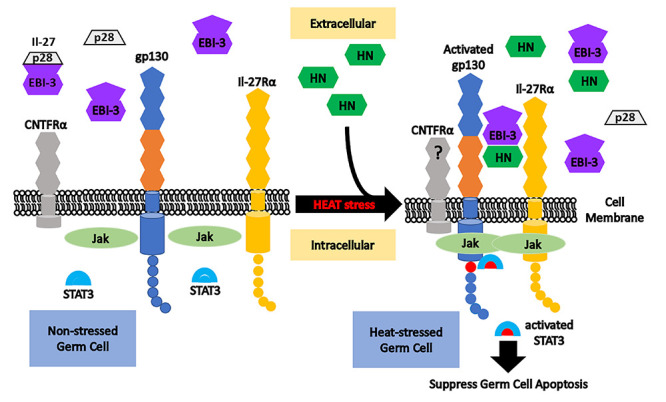

Graphical abstract

Model of humanin (HN) interaction with EBI-3, IL-27Rα, and gp130 in male germ cells at baseline and after heat induced stress. Under nonstressed condition (left part), free EBI-3 may bind with p28 to form cytokine IL-27, while IL-27Rα and gp130 may combine with each other to form the IL-27 receptor. CNTFRα may bind gp130 and IL-27Rα to form the HN membrane receptor in neuronal cells. After heat stress in the testis, exogenous HN binds with EBI-3 and interacts with gp130 plus IL-27Rα to activate the downstream Jak/STAT3 pathway. Activated STAT3 suppresses heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis. In our study, the role of CNTFRα cannot be concluded definitely. Our data suggest a different multicomponent and tissue-specific receptor for HN in the testis and linking HN action with the IL-12/IL-27 family of cytokines.

Introduction

Germ cell apoptosis occurs spontaneously during spermatogenesis or can be induced in mice [1–7], rats [8–14], monkeys [15, 16], and men [17–19] by a variety of apoptotic stimuli including testicular hyperthermia, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3), gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (GnRH-A) and testosterone (T) (suppressing both endogenous gonadotropins and subsequently intratesticular T) [20, 21], or chemotherapies [22–25]. HN is an anti-apoptotic, putatively mitochondrial-derived peptide that protects cells from stress/injury in neuronal tissue [26–34], heart and vasculature [35–38], blood-derived cells [39], pancreas [40], and the testis [22, 24, 25, 41–43]. We have previously demonstrated that HN partially prevents GnRH-A or chemotherapy induced male germ cell apoptosis in rodents [22, 24, 25, 41–43].

A previously proposed mechanism of HN action on prevention of neuronal cell death is through binding to a tripartite neuro-cytokine-related membrane receptor composed of glycoprotein 130 (gp130), IL-27 receptor subunit α (IL-27Rα, also known as WSX-1 or T cell cytokine receptor, TCCR), and ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor subunit α (CNTFRα). This trimeric receptor activates the STAT3 signaling pathway [31, 44–46]. IL-27Rα is found in immune cells, CNTFRα in neuronal cells, whereas gp130 is the essential subunit for multiple cytokine receptors belonging to the IL-6/IL-12 family of which IL-27 is a member [47]. It remains unknown whether the three components IL-27Rα/gp130/CNTFRα of HN receptor are required for the cytoprotective action of HN in other tissues including male germ cells, or whether HN interacts with other interleukin receptor subunits to mediate its effects. IL-27Rα and gp130 are both subunits of IL-27 receptor.

The cytokine IL-27 is a heterodimeric cytokine consisting of two independent subunits: p28 (also known as IL-30) and Epstein–Barr virus-induced gene 3 (EBI-3). EIB-3 predominantly binds to p28 but also binds to P35 subunit of IL-12, and p28 signals independently of EBI3 [48]. IL-27 is structurally related to IL-6 or IL-12 cytokine families [48–57]. Activation of the IL-27 receptor complex consisting of IL-27Rα subunit and gp130 [48–50] stimulates the downstream signaling pathway involving the transcription factors termed signal transducer and the activator of transcription-1 (STAT1) and STAT3 [50, 51, 54, 55]. IL-27 may show diverse immune regulatory activities under different conditions [55] and has been demonstrated to have dual roles in both the induction and inhibition of inflammation [56, 57] as well as in cancer biology [48–50, 52].

The present studies utilized experimental models previously established in our laboratory where HN prevented transient hyperthermia-induced apoptosis of germ cells in mouse ST cultures (ex vivo) [22] and in mice (in vivo). Our goal was to examine whether HN action on the male germ cells required: (1) binding to its proposed IL-6/IL-12-like trimeric receptor; and (2) interaction with IL-27 component EBI-3. Our data suggest that (1) the cytoprotective effects of HN on male germ cells are mediated via membrane receptor subunits gp130 and IL-27Rα (and activating STAT3 phosphorylation), while the role of CNTFRα is not clear; and (2) the interaction of HN with EBI-3 is necessary for the protective effect of HN against heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis. We conclude that the physical interaction of HN with EBI-3 and binding to membrane receptor subunits gp130 and IL-27Rα plays a predominant role for the cytoprotective action of HN against heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis. This is the first report that the IL-27 component, EBI-3, is involved in HN’s action which further suggests connections between HN and cytokine network.

Material and methods

Ethics statement

Animal handling and experimentation were in accordance with the recommendation of American Veterinary Medical Association and were approved by the animal care and use review committee at the Lundquist Institute at the Harbor-University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center.

Animal experimental protocol

Adult (12 week old) male wild-type mice (C57BL6/J) from Jackson Lab (Bar Harbor, Maine) were used for ex vivo seminiferous tubule culture study. Adult male il-27α knockout mice (gift from Dr Chris Saris, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and age-matched wild-type (C57BL6/N) mice from Jackson Lab were used for studying the role of IL-27Rα in HN’s cytoprotective effects on germ cells. Adult male ebi-3 knockout and age-matched wild-type (C57BL6/NJ) mice from Jackson Lab were used for studying whether EBI-3 potentiates HN’s cytoprotective actions on male germ cells. All mice were housed in a standard animal facility under controlled temperature (22 °C) and photoperiod of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness with free access to food and water.

To investigate the functional roles of HN membrane receptor subunits IL-27Rα, GP-130, and CNTFRα in the HN’s cytoprotective action on male germ cells, we performed experiments using IL-27Rα, GP-130, and CNTFRα blocking antibodies in an ex vivo ST culture system. Ten to twelve ST segments from one wild-type mouse were immersed into the culture medium in triplicates for each experiment and exposed to heat stress at 43 °C for 15 min in the presence and absence of HN and different blocking antibodies to the components of the putative HN receptor. Each experiment was repeated 6–8 times with the same age mice. The role of IL-27 component EBI-3 in the HN’s cytoprotective activity was studied using the same ST ex vivo culture system.

For the in vivo studies of the contribution of IL-27Rα or EBI-3 to HN action, age-matched adult male il-27rα (12–28 weeks old) or ebi-3 (12 weeks old) knockout or the corresponding wild-type mice were divided into four groups (n = 4 or 5/group per experiment) and received one of the following treatments: (1) vehicle (control); (2) a single IP injection of HN peptide at a dose of 40-mg/kg body weight (BW) (HN); (3) testicular hyperthermia (43 °C for 15 min; Heat); and (4) testicular hyperthermia plus HN IP injection (Heat + HN). All animals were sacrificed 6 h after treatment.

Tissue preparation

Both control and experimental animals were injected with heparin (130 IU/100 g BW, IP) 15 min before a lethal injection of sodium pentobarbital (200-mg/kg BW, IP) to facilitate testicular perfusion using a whole-body perfusion technique [13]. After perfusion with saline, one testis was removed and weighed. Portions of testicular parenchyma were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for western blotting. The contralateral testis was fixed by vascular perfusion with Bouin’s solution, collected, weighed, and processed for routine paraffin embedding for either in situ detection of apoptosis or co-immunofluorescence staining.

ST culture and flow cytometry assessment

Mice were injected with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (200-mg/kg BW, IP) and the testes were harvested. Testicular tissues were microdissected in Petri dishes containing tissue culture medium (Nutrient Mixture Ham’s F10; Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), supplemented with 0.1% of human serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich Co LLC, St. Louis, MO) and 10-mcg/ml gentamicin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) [14]. Light segments of ST (~2 mm in length, containing early and late Stages XI–IV of the seminiferous epithelium, susceptible to heat stress) were isolated under the microscope and transferred to 6-well culture plates containing 2 ml/well serum-free culture medium. ST (10–12 segments per well, in triplicates) were heated at 43 °C for 15 min to induce germ cell apoptosis. Heat-treated groups were incubated with (1) HN (10 mcg/ml); (2) scrambled peptide (SP) (10 mcg/ml); (3) HN (10 mcg/ml) + anti-gp130 neutralization antibody (1.0 mcg/ml, Cat#AF468, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN); (4) HN (10 mcg/ml) + anti-IL-27Rα antibody (1.0 mcg/ml, gift from Dr Masaaki Matsuoka, Tokyo, Japan); or (5) HN (10 mcg/ml) + anti-CNTFRα neutralization antibody (1.0 mcg/ml, Human Cat#AF-303-NA, or Rat Cat#AF-559-NA R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN); and (6) HN (10 mcg/ml) + anti-EBI-3 antibody (1.0 mcg/ml, Cat#124694, Abcam plc, Cambridge, MA). (7) HN (10 mcg/ml) + goat IgG (1.0 mcg/ml, Cat#AB-108-C, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) or HN (10 mcg/ml) + rabbit IgG (1.0 mcg/ml, Cat#AB-105-C, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) were used as negative control for the neutralization antibodies described above. The plates were then incubated at 34 °C for 16 h with 5% CO2.

After 16-h incubation, segments of ST from all the groups were collected from each well, digested into single cell suspension, and analyzed by flow-cytometry to detect germ cell apoptosis. In brief, seminiferous tubule fragments were digested by 0.25% collagenase, filtered by the cell strainer (BD Falcon REF352340, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and collected with a new set of tubes. After centrifuge and washing twice with PBS for 10 min, cells were resuspended into 100 mcL of binding buffer and stained with 5-mcL Annexin V conjugated APC (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and 5 mcL of 7-AAD (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in the dark for 15 min on ice. Tubes with nonstained cells or stained with APC only or 7-AAD only were used as background controls; 400-mcL binding buffer was added to each tube and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis (BD FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Western blotting analysis

Western blotting was performed as described previously [58, 59]. In brief, proteins were denatured and separated by a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After transferring, the Immuno-blot PVDF Membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was blocked for 1 h and then probed using anti-STAT3 (Cat#9139) or anti-pSer727 STAT3 (Cat# 9134, Cell signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA) overnight at 4 °C with constant shaking. After washing, membrane was then incubated with an anti-mouse (for STAT3 antibody, Cat#sc-2069, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-rabbit (Cat#NA934V, for all other antibodies, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) IgG-HRP secondary antibody. All antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer. For immunodetection, the membrane was incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence solutions per the manufacturer’s specifications (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and exposed to Hyperfilm ECL (Denville Scientific Inc., Metuchen, NJ).

Assessment of apoptosis

In situ detection of cells with DNA strand breaks was performed in Bouin’s-fixed, paraffin-embedded testicular sections by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated deoxy-UTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) technique [60, 61] using an ApopTag-peroxidase kit (Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, CA). Enumeration of the nonapoptotic Sertoli cell nuclei with distinct nucleoli and apoptotic germ cells was quantified at stages I–IV (early stages) and stages XI–XII (late stages) of the seminiferous epithelial cycle using an Olympus BH-2 microscope (New Hyde Park, NY). Stages were identified according to the criteria proposed by Russell et al. [62] for paraffin sections. The rate of germ cell apoptosis (apoptotic index) was expressed as the number of apoptotic germ cells per Sertoli cells [60].

Dot blotting assessment

Dot blotting was used to determine in vitro direct HN interaction with the IL-27 receptor subunit IL-27Rα; IL-27 component EBI-3, p28, and IL-12 family components p35 and p40 [63]. Peptides of interest and respective controls were spotted onto nitrocellulose (NC) membrane (Pierce, Rockford, IL) at 1 mcL per spot and then allowed to dry. In IL-27Rα experiment, the peptides spotted on membrane included: HN peptide (1, 2, and 5 nmol, GeneMed Synthesis Inc., San Antonio, TX), SP (1, 2, and 5 nmol, a nonbinding partner of HN used as negative control; GeneMed Synthesis Inc., San Antonio, TX), BAX (mouse full long sequence used as positive control, 1, 2, and 5 mcg, ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd. Rehovot, Israel), IL-27Rα (1, 2, and 5 mcg, with Human IgG Fc tail, Sigma-Aldrich, MO), and Human IgG Fc (1, 2, and 5 mcg, negative control for IL-27Rα peptide tail, Sigma-Aldrich, MO). In the EBI-3, p28, p35, and p40 experiment, the peptides spotted on membrane included: HN peptide (1, 2, and 5 nmol), SP (1, 2, and 5 nmol, negative control; GeneMed Synthesis Inc., San Antonio, TX), BAX (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg, positive control), EBI-3 (with Human IgG Fc tail), p28, p35, and p40 (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg, all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, MO), and Human IgG Fc (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg, negative control for EBI-3 peptide tail, Sigma-Aldrich, MO). After blocking the nonspecific sites by 0.2% I-block (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for 3 h at room temperature, the NC membranes were incubated with test peptides (HN peptide, 5 mcg/ml) overnight at 4 °C with gentle rocking. After washing in 0.3% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline, the NC membranes were incubated with the primary antihuman HN antibody (Cat#H2414, Sigma-Aldrich Co LLC, St. Louis, MO) overnight 4 °C with gentle rocking. Following incubation with secondary antirabbit antibody (Cat#NA934V, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), the membranes were washed, incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence solutions per the manufacturer’s specifications (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), and exposed to Hyperfilm ECL (Denville Scientific Inc., Metuchen, NJ).

Immunofluorescence analyses

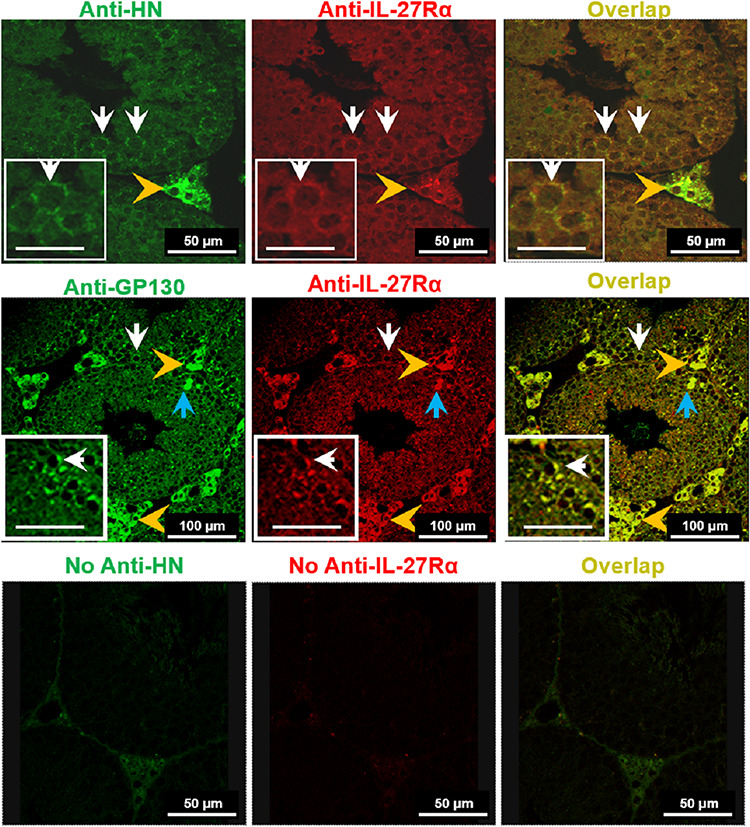

Co-localization of IL-27Rα with humanin or gp130 in the testis was detected by confocal microscopy using double immunostaining as previously described [59]. In brief, after deparaffinization and rehydration, testicular sections were treated with blocking serum at room temperature. After washing the slides, sections were incubated with the affinity purified antihumanin antibody (1:100, gift from Dr Pinchas Cohen) or anti-gp130 antibody (Cat#sc-656, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 h followed by goat antirabbit Alexa 633-labeled secondary antibody (Cat#A-21070, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with a goat polyclonal anti-IL-27Rα antibody (Cat#sc-47065, 1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4 °C overnight followed by donkey antigoat FITC secondary antibody (Cat#sc-2024, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 30 min. For negative controls, sections were treated only with secondary antibody, and no signals were detected (Figure 6, bottom panel). il-27rα knockout mouse testis slide was used as negative control for determining IL-27Rα antibody specificity and no staining signals were detected (data not shown). Con-focal imaging was performed using a Leica TCS-SP-MP con-focal microscope equipped with a 488-nm argon laser for the excitation of green fluorophores (FITC) and a 633-nm helium-neon laser for the excitation of red fluorophores (Alex 633).

Figure 6 .

Co-localization of HN and IL-27Rα or IL-27Rα with gp130 in testes. Con-focal images of mouse testis from heat plus HN-treated mice exhibited HN immunoreactivity (green), IL-27Rα (red), and co-localization of HN and IL-27Rα (yellow) in both Leydig cells (Upper panel, Scale bar, 50 μm) and germ cells (Upper panel insets, Scale bar, 25 μm). Middle panel showed con-focal images of testis from heat plus HN-treated mouse exhibited gp130 (green), IL-27Rα (red), and co-localization of gp130 and IL-27Rα (yellow) in both Leydig cells (Middle panel, Scale bar, 100 μm) and germ cells (Middle panel inserts, Scale bar, 50 μm). [Gold arrowheads point to Leydig cells; white arrowheads germ cells; and light blue arrowheads apoptotic germ cells.] Bottom panel showed negative controls with no anti-HN antibody (secondary antibody label green), no anti-IL-27Rα antibody (secondary antibody label red), and co-localization showing no florescent signal in germ cells and weak background signal in Leydig cells (Bottom panel, Scale bar, 50 μm).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SigmaStat 12.0 Program (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). The Student–Newman–Keuls test after one-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to test for statistical significance. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

IL-27Rα and gp130 neutralizing antibodies blocked HN’s effect on heat-induced germ cell apoptosis

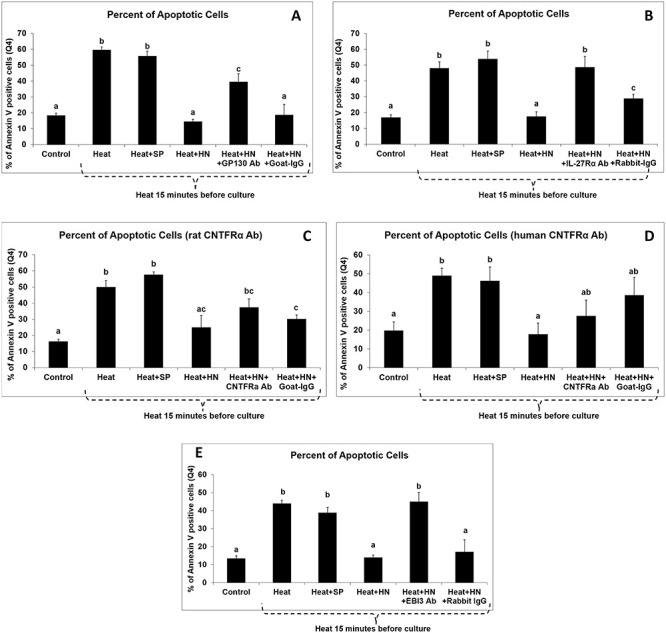

Heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis in ex vivo seminiferous tubule culture was significantly decreased despite variation from different experiments by co-incubation with 10-mcg/ml HN peptide but not by SP (Figure 1A–D). Anti-gp130 (Figure 1A) antibody significantly blocked the protective effect of HN peptide on apoptosis (P < 0.05), whereas goat IgG had no effect on germ cell apoptosis. Anti-IL-27Rα (Figure 1B) antibody significantly blocked the protective effect of HN peptide on germ cell apoptosis (P < 0.05). In contrast, anti-CNTFRα neutralizing antibodies (either rat or human specific) similar to Immunoglobulin G did not significantly decrease the cytoprotective effect of HN on germ cells (Figure 1C and D). The specificity of both anti-CNTFRα receptor antibodies was demonstrated as both antibodies neutralized the effect of CNTF peptide in neuroendocrine beta cells (NIT-1 cell line) and ST (see Supplementary Figure S1A and B).

Figure 1 .

Effect of anti-gp130, anti-IL-27Rα, anti-CNTFRα, and anti-EBI-3 antibodies on the cytoprotective effect of HN against heat-induced germ cell apoptosis. Mouse ST were treated with vehicle (Control), heat (Heat), heat plus SP (Heat + SP), heat plus HN peptide (Heat + HN), heat plus HN peptide plus anti-gp130 (Heat + HN + gp130) (A), or heat plus HN peptide plus anti-IL-27Rα (Heat + HN + IL-27Rα) (B), or heat plus HN peptide plus anti-CNTFRα antibodies (Heat + HN + CNTFRa) (C and D), or heat plus HN peptide plus anti-EBI-3 (Heat + HN + EBI-3) (E) as described in experimental procedures. Apoptotic cell numbers were determined by flow-cytometry with double staining with 7-AAD and Annexin V conjugated APC. Compared with negative control, anti-gp130 (A), anti-IL-27Rα (B), anti-EBI-3 (E), but not anti-CNTFRα (C and D) antibodies, blocked the protective effect of HN on heat-induced germ cell apoptosis. Heat + HN peptide + normal IgG (Heat + HN + IgG) was used as negative control. Values are means ± SEM. Means with unlike superscripts are significantly (P < 0.05) different.

EBI-3 antibody blocked HN effect on heat-induced germ cell apoptosis

Heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis in ex vivo seminiferous tubule cultures was significantly decreased by co-incubation with 10-mcg/ml HN peptide but not by SP (Figure 1E). Anti-EBI-3 (Figure 1E) antibody significantly blocked the protective effect of HN peptide on apoptosis (P < 0.05), whereas rabbit IgG had no effect on germ cell apoptosis.

HN prevents heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis in wild-type mice but not in il-27rα or ebi-3 knockout animals

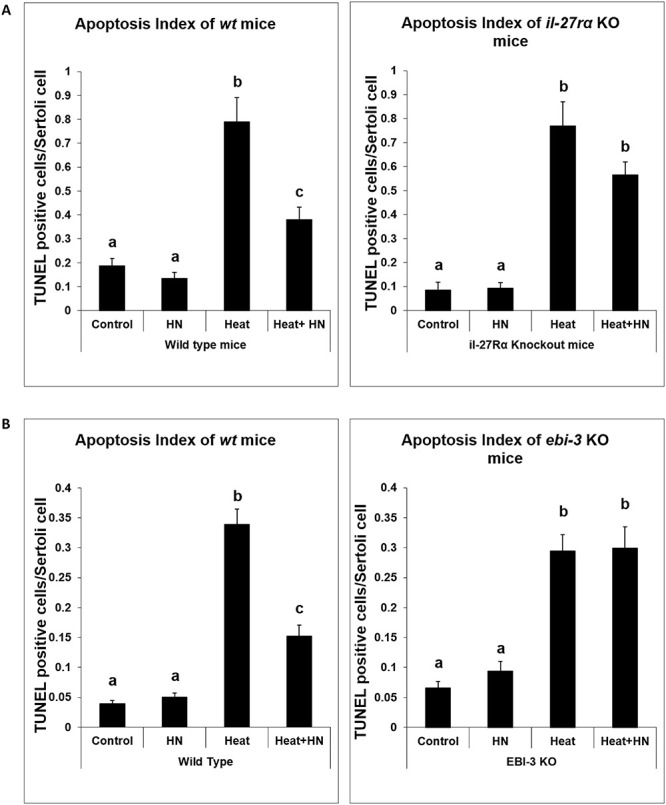

In il-27rα knockout versus wild-type mice experiment, testicular hyperthermia increased germ cell apoptosis primarily at early and late stages of seminiferous epithelial cycles in wt mice (Figure 2A, left panel: 0.79 ± 0.10, TUNEL positive germ cell/Sertoli cell; P < 0.01 compared with wt control group, 0.17 ± 0.03). HN partially suppressed heat-induced germ cell apoptosis (Figure 2A, left panel: 0.38 ± 0.05, P < 0.01 compared with heat-treated group). In il-27rα knockout mice, heat significantly induced germ cell apoptosis (Figure 2A, right panel: 0.77 ± 0.10; P < 0.01 compared with knockout non-heated group, 0.09 ± 0.02) mainly at early and late stages. HN was not effective in preventing heat-induced apoptosis (Figure 2A, right panel: 0.56 ± 0.06, P > 0.05 compared with heat treatment group).

Figure 2 .

Effect of HN on heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis in wild-type and il-27rα or ebi-3 knockout mice. Both wild-type and il-27rα or ebi-3 knockout mice were treated with vehicle (Control), Humanin peptide (HN), heat (Heat), and heat plus HN peptide (Heat + HN) as described in experimental procedures. Male germ cell apoptosis was detected by TUNEL staining and expressed as the number of TUNEL positive germ cells per Sertoli cell. HN prevented heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis in wild-type mice (A and B, left panel, P < 0.05), whereas in il-27rα knockout animals, HN did not significantly prevent heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis (A, right panel, P > 0.05). In ebi-3 knockout animal, HN also did not prevent heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis (B, right panel, P > 0.05).

In ebi-3 knockout versus wild-type mice, testicular hyperthermia increased germ cell apoptosis primarily at early and late stages of seminiferous epithelial cycles in wt mice (Figure 2B, left panel: 0.34 ± 0.03 TUNEL positive germ cell/Sertoli cell; P < 0.01 compared with wt control group, 0.04 ± 0.01). Heat-induced germ cell apoptosis was partially inhibited by synthetic HN administration in wt mice (Figure 2B, left panel: 0.15 ± 0.02, P < 0.01 compared with heat-treated group). In ebi-3 knockout mice, heat significantly induced germ cell apoptosis (Figure 2B, right panel: 0.30 ± 0.03; P < 0.01 compared with knockout nonheated group, 0.07 ± 0.01) mainly at early and late stages; while HN did not prevent heat-induced apoptosis (Figure 2B, right panel: 0.30 ± 0.04, P > 0.05 compared with heat treatment group).

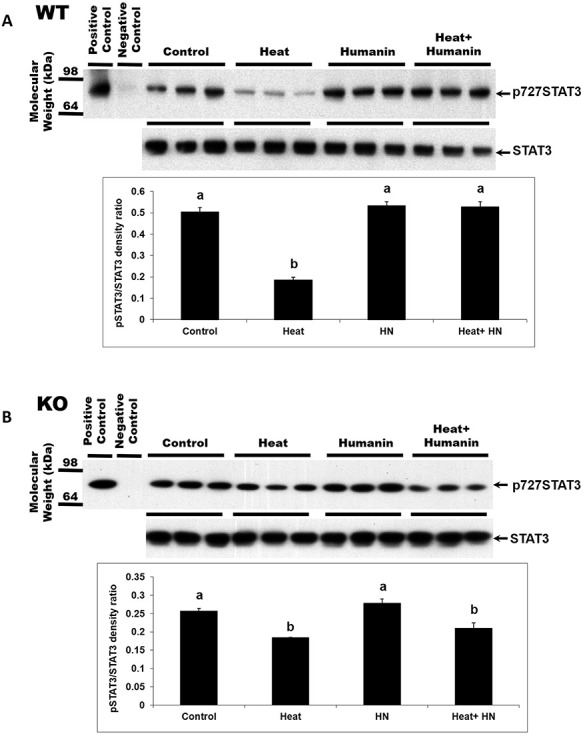

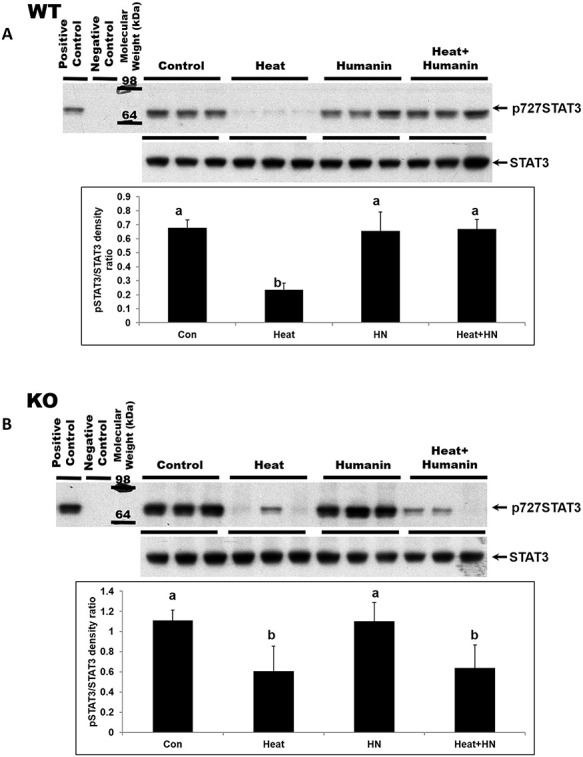

HN treatment restored heat-suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation

STAT3 has 2 phosphorylation sites—Ser727 and Tyr705. Phosphorylation of these 2 sites leads to the activation of STAT3. Immuno-blot analyses on testis homogenates showed that STAT3 expression did not significantly change with HN treatment under basal conditions in both wt and il-27rα knockout mice (Figure 3A and B). Heat treatment suppressed Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 in testes in both the wt and il-27rα knockout mice (P < 0.05, Figure 3A and B). HN treatment restored the expression of Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 that was suppressed by heat treatment (P < 0.05) in the testes of wt mice (Figure 3A) but not in il-27rα knockout animals after heat exposure (Figure 3B).

Figure 3 .

Effect of HN on the heat-suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation in wild-type and il-27rα knockout mice. STAT3 phosphorylation of total testicular lysates was detected by western blot. Mice were treated with vehicle (Control), HN peptide (HN), heat (Heat), and heat plus HN peptide (Heat + HN) as described in experimental procedures. (A) In wild-type mice, phosphorylated STAT3 (p727) decreased after heat treatment (P < 0.05). HN combined with heat treatment restored STAT3 phosphorylation. (B) In il-27rα knockout mice, phosphorylated STAT3 decreased after heat treatment. HN combined with heat treatment did not restore STAT3 phosphorylation to the control or HN treated levels. Values are means ± SEM. Means with unlike superscripts are significantly (P < 0.05) different.

Immuno-blot analyses on testis homogenates also confirmed the similar changes of STAT3 phosphorylation in wt and ebi-3 knockout mice (P < 0.05, Figure 4A and B). STAT3 expression had no significant change with HN treatment under basal conditions in both wt and ebi-3 knockout mice (Figure 4A and B). Heat treatment suppressed Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 in testes in both the wt and ebi-3 knockout mice (P < 0.05, Figure 4A and B). HN treatment restored the expression of Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 that was suppressed by heat treatment (P < 0.05) in the testes of wt mice (Figure 4A) but not in ebi-3 knockout animals after heat exposure (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 .

Effect of HN on the heat-suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation (p727) in wild-type and ebi-3 knockout mice. STAT3 phosphorylation of total testicular lysates was detected by western blot. Mice were treated with vehicle (Control), HN peptide (HN), heat (Heat), and heat plus HN peptide (Heat + HN) as described in experimental procedures. (A) In wild-type mice, phosphorylated STAT3 decreased after heat treatment (P < 0.05). HN combined with heat treatment restored STAT3 phosphorylation. (B) In ebi-3 knockout mice, phosphorylated STAT3 decreased after heat treatment. HN combined with heat treatment did not restore STAT3 phosphorylation to the control or HN treated levels. Values are means ± SEM. Means with unlike superscripts are significantly (P < 0.05) different.

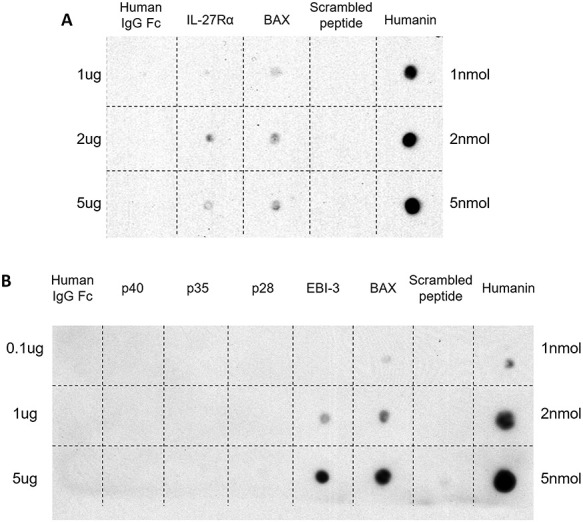

Direct interaction between HN and IL-27Rα

To determine if HN interacts directly with IL-27Rα in vitro, we performed dot blot experiments where increasing concentrations of HN, SP, BAX, IL-27Rα, and human IgG Fc fragment were spotted on a membrane and then incubated sequentially with HN, rabbit anti-HN antibody, antirabbit secondary antibody, and ECL plus reporting reagent. Figure 5A demonstrates that HN interacted with BAX (positive control) and IL-27Rα but not with SP and human IgG Fc (negative controls).

Figure 5 .

HN and IL-27Rα or EBI-3 interaction detected by dot blot. (A) The peptides used for dot blots included: humanin (HN 1, 2, and 5 nmol), SP (1, 2, and 5 nmol, peptide with the same amino acid as HN but scrambled was used as negative control), BAX (1, 2, and 5 mcg, positive control), IL-27Rα (1, 2, and 5 mcg), and human IgG Fc (1, 2, and 5 mcg, negative control for IL-27Rα). Dot blots confirmed the interaction between HN and IL-27Rα. (B) The peptides used for dot blots included: humanin (HN 1, 2, and 5 nmol), SP (1, 2, and 5 nmol, negative control), BAX (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg, positive control), EBI-3 (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg), p28 (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg), p35 (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg), p40 (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg), and human IgG Fc (0.1, 1, and 5 mcg, negative control for EBI-3). Dot blots confirmed the specific interaction between HN and EBI-3.

Direct interaction between HN and EBI-3 but not IL-27 or IL-12 cytokine components

To examine whether HN interacts directly with EBI-3 in vitro, we performed dot blot experiments where increasing concentrations of HN, SP, BAX, EBI-3 (IL-27 component), p28 (IL-27 component), p35, p40 (other components of the IL-12 cytokine family), and human IgG Fc fragment were spotted on a membrane and then processed. Figure 5B demonstrates that HN interacted with BAX (positive control) and EBI-3 but not with p28, p35, p40, SP, and human IgG Fc (negative controls).

Co-localization of HN with IL-27Rα and IL-27Rα with gp130 in testis

Testicular sections from all treatment groups were immunostained for HN and IL-27Rα. As shown in Figure 6 upper panel, after heat exposure, IL-27Rα and HN co-localized both in germ cells and Leydig cells (see insets). IL-27Rα also co-localized with gp130 in Leydig cells and germ cells (Figure 6, middle panel, see insets). There was no staining when primary antibodies to HN and IL-27Rα were not used (Figure 6, bottom panel). We could not perform HN, IL-27Rα, and gp130 co-staining with EIB-3 because of the limited availability of secondary antibodies selection from different species to avoid cross reactivity with endogenous mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG).

Discussion

HN is an endogenous peptide that protects against Alzheimer Disease (AD)-related and non-AD-related neuronal cell death [26–34]. A putative trimeric receptor was demonstrated in the neuronal cell membranes, which mediates the neuroprotective activity of HN. This trimeric receptor belongs to the IL-6 neuro-cytokine receptor family (with three subunits: CNTFRα, IL-27Rα, and gp130) and mediates its action via the STAT3 phosphorylation [44–46, 64]. Glycoprotein 130 (gp130) is a common transmembrane subunit of many cytokine receptors belonging to the IL-6/IL-12 receptor family of which IL-27 is a member. IL-27 has two components—p28 and EBI-3. The IL-27Rα/gp130 heterodimeric receptor complex plays a critical role in cytokine IL-27 signal transduction through STAT1 and 3 mainly [65–68]. CNTF is another component of IL-6/IL-12 heterodimeric cytokine family that activates a receptor comprising of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored nonsignaling subunit, CNTFRα, and two signaling transmembrane chains—leukemia inhibitory factor receptor b (LIFRb) and gp130 [69–73]. Binding of IL-6/IL-12 family cytokines to their receptors triggers intracellular signal cascades including Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT signaling pathways [71, 74, 75]. HN-induced anti-apoptotic effects in AD in vitro and in vivo depend on the activation of STAT3 [27, 31, 44–46]. Binding of HN to the proposed trimeric receptor has only been shown in neuronal cells. As IL-27Rα and gp130 are both IL-27 receptor subunits, we studied the role of the IL-12 heterodimeric cytokine components EBI-3, p28, p35, and p40 in the cytoprotective action of HN in the testis. HN has also been shown to have other mechanisms of action. Exogenous HN can be taken up by cells in culture and localizes in cytoplasmic compartments and mitochondria [76]. HN acts intracellularly by binding to BAX preventing its translocation to the mitochondria to initiate apoptosis [77]. HN also binds intracellularly to IGFBP-3 which may prevent IGFBP-3 action [78]. Additionally, HN has been shown to bind the formyl peptide receptor-like receptor [79].

In this study, we found that HN prevented heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis both ex vivo and in vivo. HN restored heat-suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation in the testis. This is consistent with our previous finding that HN prevented GnRH-A-induced apoptosis by reversing the GnRH-A-suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation [41]. Our prior data support that the anti-apoptotic effect of HN in male germ cell acts via STAT3 phosphorylation suggesting that HN may interact with the cell membrane cytokine receptor complex CNTFRα/WSX1/gp130 to activate the downstream STAT3 pathway [30, 44–46].

Using ex vivo mouse seminiferous tubule culture system, in this study, we showed that neutralizing antibodies against gp130 and IL-27Rα prevented the cytoprotective action of HN in reducing heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis. We used the il-27rα knockout mice to further validate the role of IL-27Rα in the cytoprotective effect of HN in heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis. HN prevented heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis via restoring STAT3 phosphorylation in wild-type mouse. In il-27rα knockout animals, HN was able to neither protect male germ cells from heat-induced apoptosis nor restore STAT3 phosphorylation. We further confirmed our finding by showing the direct interaction of HN and IL-27Rα in dot blot assay. Immunofluorescent co-staining studies support that HN and IL-27Rα co-localized in germ cells and Leydig cells after heat treatment. We also found that IL-27Rα and gp130 co-localized in germ cells and Leydig cells. However, two neutralizing antibodies against CTNFRα did not significantly change the cytoprotective action of HN against heat-induced germ cell death. We did not further investigate the role of CTNFRα as null mutant mice are not viable [80] and we did not generate a testis-targeted null mutant or a knock-down animal to extend the studies. From our observation, HN predominantly interacts with gp130 and IL-27Rα and activates STAT3 to exert its anti-apoptotic action on male germ cells under stress.

In addition to requiring the IL-27 heterodimeric cytokine receptor subunits gp130 and IL-27Rα, our results suggested that IL-27 cytokine component EBI-3 may play an important role in the action of HN. We demonstrated that EBI-3 blocking antibody suppressed the cytoprotective action of HN on male gem cells in ex vivo mouse seminiferous tubule cultures. Our subsequent experiment with ebi-3 knockout mice provided further evidence that without EBI-3 expression, the cytoprotective effect of HN in heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis was compromised. In ebi-3 knockout animals, HN was unable to protect heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis and restore STAT3 phosphorylation. The direct and specific interaction of HN and EBI-3 was confirmed in dot blot assay, whereas p28, p35, and p40, the other components of IL-12 cytokine family, had no interaction with HN.

Our results in the present study support that EBI-3 is an interacting partner facilitating HN interaction with gp130/IL-27Rα receptor and activating the downstream STAT3 pathway to mediate its cytoprotective action in male germ cells. EBI-3 is one of the component of IL-27, the other one is p28. Membrane bound IL-27Rα and gp130 form the IL-27 receptor [49]. The interaction between EBI-3 and gp130/IL-27Rα had been shown to be essential for IL-27 and its receptor mediated signaling pathway in immune cells [48, 56, 81]. It is known that EBI-3 functions as a soluble cytokine-receptor-like molecule and together with p28 (a cytokine like peptide) forms the heterodimeric cytokine IL-27 that modulates both T and B cells through heterodimer receptor consisting of two subunits, gp130 and IL-27Rα [56, 82]. IL-27 binding with the gp130/IL-27Rα complex activates the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which mainly involves STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation [50]. IL-27R has immune-enhancing activities such as mediating Th1 polarization [65, 83], inducing IFN-γ production [84], promoting IL-10 production [85], and increasing cytotoxic T lymphocyte generation and proliferation [86, 87]. IL-27 also has anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory functions including inhibition of Th2, innate lymphoid cell-2 (ILC2), and Th17 responses [88, 89]; induction of type-1 regulatory (Tr1) T cells and the upregulation of PD-L1 [90, 91]; and expression of IL-10 [92–94]. Importantly, HN functionally related molecules, EBI-3, IL-27Rα, and gp130, are key members of IL-27 and IL-27R complex and may also be involved in cytokines IL-6/IL-12 function. Thus, our results suggest that HN may be a cytokine involved in immune regulation in response to stresses.

The mechanism of HN action may include the binding to cell surface receptors activating intracellular signaling pathways and/or directly be taken up into cytoplasmic compartment activating the mitochondria-mediated anti-apoptotic cascades [38]. Our present data showed that EBI-3 (an IL-27 component) and IL-27Rα and gp130 (both IL-27 receptor subunits) are components of HN-receptor complex in male germ cells that mediates the cytoprotective effect of HN, although the role of CNTFRα cannot be completely excluded. Because gp130 is the common subunit in IL-6 receptor family for signal transduction [47], the membrane receptor subunit IL-27Rα and IL-27 component EBI-3 may play more specific roles in HN protective effects in mouse testis. While our data are compelling, we cannot exclude that other subunit(s) may be involved in HN receptor assembling. The difference in HN receptor subunits between neuronal and male germ cell suggests that HN may have tissue-specific receptor subunits in different organs. Taking into consideration our published data and work from other group demonstrating that HN binds IGFBP-3 [78] and BAX [77, 95, 96], we conclude that the mechanism of anti-apoptotic effect of HN on male germ cells is mediated through both membrane receptor and mitochondria-associated pathways. We speculate that tissue-specific HN membrane receptors may be a target of drug development where agonists may protect male germ cells from stress-induced death (e.g. testicular hyperthermia, hormonal deprivation, and chemotherapeutic agents), and antagonists may accelerate germ cell death for male contraception development.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the cytoprotective action of HN on heat-induced male germ cell apoptosis is mediated by interactions with the IL-27 component EBI-3, and predominantly with a receptor complex composed of the membrane bound subunits IL-27Rα and gp130 and subsequent activation of STAT3 signaling pathways. HN, the mitochondrial-derived small anti-apoptotic peptide, is important in the regulation of germ cell homeostasis, balancing germ cell proliferation against germ cell death which may be important in testicular stress and male fertility. Our data also suggest that HN may be a cytokine interacting with the IL-6/IL-12 family proteins to exert different actions in different tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Vince Atienza for technical assistance.

Grant Support:This study supported by the Endocrinology, Metabolism and Nutrition Training Grant (T32 DK007571) and UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR000124) at The Lundquist Institute and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

Contributor Information

Yue Jia, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, The Lundquist Research Institute and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA; Department of Pathology, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA.

Ronald S Swerdloff, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, The Lundquist Research Institute and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA.

YanHe Lue, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, The Lundquist Research Institute and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA.

Jenny Dai-Ju, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, The Lundquist Research Institute and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA.

Prasanth Surampudi, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, The Lundquist Research Institute and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA.

Pinchas Cohen, USC Davis School of Gerontology, Ethel Percy Andrus Gerontology Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Christina Wang, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, The Lundquist Research Institute and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Author contributions

YJ, RSS, and CW designed research; YJ, YL, PS, and JD-J performed experiment and analyzed data; YJ, YL, RSS, PC, and CW wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Reid BO, Mason KA, Withers HR, West J. Effects of hyperthermia and radiation on mouse testis stem cells. Cancer Res 1981; 41:4453–4457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gasinska A, Hill S. The effect of hyperthermia on the mouse testis. Neoplasma 1990; 37:357–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockett JC, Mapp FL, Garges JB, Luft JC, Mori C, Dix DJ. Effects of hyperthermia on spermatogenesis, apoptosis, gene expression, and fertility in adult male mice. Biol Reprod 2001; 65:229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang M, Jiang M, Bi Y, Zhu H, Zhou Z, Sha J. Autophagy and apoptosis act as partners to induce germ cell death after heat stress in mice. PLoS One 2012; 7:e41412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JH, Park SJ, Kim TS, Park HJ, Park J, Kim BK, Kim GR, Kim JM, Huang SM, Chae JI, Park CK, Lee DS. Testicular hyperthermia induces unfolded protein response signaling activation in spermatocyte. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013; 434:861–8666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul C, Teng S, Saunders PT. A single, mild, transient scrotal heat stress causes hypoxia and oxidative stress in mouse testes, which induces germ cell death. Biol Reprod 2009; 80:913–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinha Hikim AP, Lue Y, Yamamoto CM, Vera Y, Rodriguez S, Yen PH, Soeng K, Wang C, Swerdloff RS. Key apoptotic pathways for heat-induced programmed germ cell death in the testis. Endocrinology 2003; 144:3167–3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan VR, Brown IR. The effect of hyperthermia on the induction of cell death in brain, testis, and thymus of the adult and developing rat. Cell Stress Chaperones 2002; 7:73–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanter M, Aktas C, Erboga M. Heat stress decreases testicular germ cell proliferation and increases apoptosis in short term: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Toxicol Ind Health 2013; 29:99–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaushik K, Kaushal N, Mittal PK, Kalla NR. Heat induced differential pattern of DNA fragmentation in male germ cells of rats. J Therm Biol 2019; 84:351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman A, Rodríguez-Casuriaga R, González-López E, Capoano CA, Santiñaque FF, Geisinger A. MTCH2 is differentially expressed in rat testis and mainly related to apoptosis of spermatocytes. Cell Tissue Res 2015; 361:869–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha Hikim AP, Wang C, Leung A, Swerdloff RS. Involvement of apoptosis in the induction of germ cell degeneration in adult rats after gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist treatment. Endocrinology 1995; 136:2770–2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lue YH, Sinha Hikim AP, Swerdloff RS, Im P, Taing KS, Bui T, Leung A, Wang C. Single exposure to heat induces stage-specific germ cell apoptosis in rats, role of intratesticular testosterone (T) on stage specificity. Endocrinology 1999; 140:1709–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vera Y, Erkkila K, Wang C, Nunez C, Kyttanen S, Lue Y, Dunkel L, Swerdloff RS, Sinha Hikim AP. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in apoptotic signaling of murine and human male germ cells after hormone deprivation. Mol Endocrinol 2006; 20:1597–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lue Y, Wang C, Liu YX, Hikim AP, Zhang XS, Ng CM, Hu ZY, Li YC, Leung A, Swerdloff RS. Transient testicular warming enhances the suppressive effect of testosterone on spermatogenesis in adult cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia Y, Sinha Hikim AP, Swerdloff RS, Lue YH, Vera Y, Zhang XS, Hu ZY, Li YC, Liu YX, Wang C. Signaling pathways for germ cell death in adult Cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) induced by mild testicular hyperthermia and exogenous testosterone treatment. Biol Reprod 2007; 77:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazarus BA, Zorgniotti AW. Thermoregulation of the human testis. Fertil Steril 1975; 26:757–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dada R, Gupta NP, Kucheria K. Spermatogenic arrest in men with testicular hyperthermia. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen 2003; S1:235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Cui YG, Wang XH, Jia Y, Sinha HA, Lue YH, Tong JS, Qian LX, Sha JH, Zhou ZM, Hull L, Leung Aet al. . Transient scrotal hyperthermia and levonorgestrel enhance testosterone-induced spermatogenesis suppression in men through increased germ cell apoptosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92:3292–3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruwanpura SM, McLachlan RI, Stanton PG, Loveland KL, Meachem SJ. Pathways involved in testicular germ cell apoptosis in immature rats after FSH suppression. J Endocrinol 2008; 197:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha Hikim AP, Swerdloff RS. Temporal and stage-specific changes in spermatogenesis of rat after gonadotropin deprivation by a potent gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist treatment. Endocrinology 1993; 133:2161–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia Y, Ohanyan A, Lue YH, Swerdloff RS, Liu PY, Cohen P, Wang C. The effects of humanin and its analogues on male germ cell apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. Apoptosis 2015; 20:551–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia Y, Lue Y, Swerdloff RS, Lasky JL, Panosyan EH, Dai-Ju J, Wang C. The humanin analogue (HNG) prevents temozolomide-induced male germ cell apoptosis and other adverse effects in severe combined immuno-deficiency (SCID) mice bearing human medulloblastoma. Exp Mol Pathol 2019; 109:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surampudi P, Chang I, Lue Y, Doumit T, Jia Y, Atienza V, Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Wang C. Humanin protects against chemotherapy-induced stage-specific male germ cell apoptosis in rats. Andrology 2015; 3:582–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lue Y, Swerdloff R, Wan J, Xiao J, French S, Atienza V, Canela V, Bruhn KW, Stone B, Jia Y, Cohen P, Wang C. The potent humanin analogue (HNG) protects germ cells and leucocytes while enhancing chemotherapy-induced suppression of cancer metastases in male mice. Endocrinology 2015; 156:4511–4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiba T, Hashimoto Y, Tajima H, Yamada M, Kato R, Niikura T. Neuroprotective effect of activity-dependent neurotrophic factor against toxicity from familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutant SOD1 in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci Res 2004; 78:542–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto Y, Niikura T, Tajima H, Yasukawa T, Sudo S, Ito Y, Kita Y, Kawasumi M, Kouyama K, Doyu M, Sobue G, Koide Tet al. . A rescue factor abolishing neuronal cell death by a wide spectrum of familial Alzheimer’s disease genes and Aβ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98:6336–6341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kariya S, Takahashi N, Ooba N, Kawahara M, Nakayama H, Ueno S. Humanin inhibits cell death of serum-deprived PC12h cells. Neuro Report 2002; 13:903–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kariya S, Hirano M, Nagai Y, Furiya Y, Fujikake N, Toda T. Humanin attenuates apoptosis induced by DRPLA proteins with expanded polyglutamine stretches. J Mol Neurosci 2005; 25:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuoka M, Hashimoto Y, Aiso S, Nishimoto I. Humanin and colivelin, neuronal-death-suppressing peptides for Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. CNS Drug Rev 2004; 12:113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuoka M. Humanin, a defender against Alzheimer’s disease? Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov 2009; 4:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimoto I, Matsuoka M, Niikura T. Unravelling the role of humanin. Trends Mol Med 2004; 10:102–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu X, Chua CC, Gao J, Hamdy RC, Chua BH. Humanin is a novel neuroprotective agent against stroke. Stroke 2006; 37:2613–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, Chua KW, Chua CC, Liu CF, Hamdy RC, Chua BH. Synergistic protective effects of humanin and necrostatin-1 on hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Brain Res 2010; 1355:189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bachar AR, Scheffer L, Schroeder AS, Nakamura HK, Cobb LJ, Oh YK, Lerman LO, Pagano RE, Cohen P, Lerman A. Humanin is expressed in human vascular walls and has a cytoprotective effect against oxidized LDL-induced oxidative stress. Cardiovasc Res 2010; 88:360–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung SS, Van Nostrand WE. Humanin rescues human cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells from Abeta-induced toxicity. J Neurochem 2003; 84:266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muzumdar RH, Huffman DM, Calvert JW, Jha S, Weinberg Y, Cui L, Nemkal A, Atzmon G, Klein L, Gundewar S, Ji SY, Lavu Met al. . Acute humanin therapy attenuates myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010; 30:1940–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lue Y, Gao C, Swerdloff R, Hoang J, Avetisyan R, Jia Y, Rao M, Ren S, Atienza V, Yu J, Zhang Y, Chen Met al. . Humanin analog enhances the protective effect of dexrazoxane against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018; 315:H634–H643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang D, Li H, Yuan H, Zheng M, Bai C, Chen L, Pei X. Humanin delays apoptosis in K562 cells by down-regulation of P38 MAP kinase. Apoptosis 2005; 10:963–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoang PT, Park P, Cobb LJ, Paharkova-Vatchkova V, Hakimi M, Cohen P. The neurosurvival factor humanin inhibits beta-cell apoptosis via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation and delays and ameliorates diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Metabolism 2010; 59:343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia Y, Lue YH, Swerdloff R, Lee KW, Cobb LJ, Cohen P, Wang C. The cytoprotective peptide humanin is induced and neutralizes Bax after pro-apoptotic stress in the rat testis. Andrology 2013; 1:651–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lue Y, Swerdloff R, Liu Q, Mehta H, Hikim AS, Lee KW, Jia Y, Hwang D, Cobb LJ, Cohen P, Wang C. Opposing roles of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 and humanin in the regulation of testicular germ cell apoptosis. Endocrinology 2010; 151:350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moretti E, Giannerini V, Rossini L, Matsuoka M, Trabalzini L, Collodel G. Immunolocalization of humanin in human sperm and testis. Fertil Steril 2010; 94:2888–2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuoka M, Hashimoto Y. Humanin and the receptors for humanin. Mol Neurobiol 2010; 41:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hashimoto Y, Kurita M, Aiso S, Nishimoto I, Matsuoka M. Humanin inhibits neuronal cell death by interacting with a cytokine receptor complex or complexes involving CNTF receptor α/WSX-1/gp130. Mol Biol Cell 2009; 20:2864–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto Y, Kurita M, Matsuoka M. Identification of soluble WSX-1 not as a dominant-negative but as an alternative functional subunit of a receptor for an anti-Alzheimer's disease rescue factor Humanin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009; 389:95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones LL, Vignali DA. Molecular interactions within the IL-6/IL-12 cytokine/receptor superfamily. Immunol Res 2011; 51:5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carl JW, Bai XF. IL27: its roles in the induction and inhibition of inflammation. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2008; 1:117–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hunter CA, Kastelein R. Interleukin-27: balancing protective and pathological immunity. Immunity 2012; 37:960–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fabbi M, Carbotti G, Ferrini S. Dual roles of IL-27 in cancer biology and immunotherapy. Mediators Inflamm 2017; 2017:3958069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Q, Regulation LJ. Immune function of IL-27. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016; 941:191–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kourko O, Seaver K, Odoardi N, Basta S, Gee K. IL-27, IL-30, and IL-35: a cytokine triumvirate in cancer. Front Oncol 2019; 9:969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones GW, Hill DG, Cardus A, Jones SA. IL-27: a double agent in the IL-6 family. Clin Exp Immunol 2018; 193:37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoshida H, Hunter CA. The immunobiology of interleukin-27. Annu Rev Immunol 2015; 33:417–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall AO, Silver JS, Hunter CA. The immunobiology of IL-27. Adv Immunol 2012; 115:1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morishima N, Mizoguchi I, Okumura M, Chiba Y, Xu M, Shimizu M, Matsui M, Mizuguchi J, Yoshimoto T. A pivotal role for interleukin-27 in CD8+ T cell functions and generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010; 2010:605483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshida H, Miyazaki Y. Regulation of immune responses by interleukin-27. Immunol Rev 2008; 226:234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jia Y, Castellanos J, Wang C, Sinha-Hikim I, Lue Y, Swerdloff RS, Sinha-Hikim AP. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in male germ cell apoptosis in the rat. Biol Reprod 2009; 80:771–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson C, Jia Y, Wang C, Lue YH, Swerdloff RS, Zhang XS, Hu ZY, Li YC, Liu YX, Hikim AP. Role of caspase 2 in apoptotic signaling in primate and murine germ cells. Biol Reprod 2008; 79:806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sinha Hikim AP, Rajavashisth TB, Sinha Hikim I, Lue Y, Bonavera JJ, Leung A, Wang C, Swerdloff RS. Significance of apoptosis in the temporal and stage-specific loss of germ cells in the adult rat after gonadotropin deprivation. Biol Reprod 1997; 57:1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinha Hikim AP, Lue Y, Diaz-Romero M, Yen PH, Wang C, Swerdloff RS. Deciphering the pathways of germ cell apoptosis in the testis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2003; 85:175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Russell L. Movement of spermatocytes from the basal to the adluminal compartment of the rat testes. Am J Anat 1977; 148:313–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jia Y, Lee KW, Swerdloff R, Hwang D, Cobb LJ, Sinha Hikim A, Lue YH, Cohen P, Wang C. Interaction of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 and BAX in mitochondria promotes male germ cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:1726–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hashimoto Y, Suzuki H, Aiso S, Niikura T, Nishimoto I, Matsuoka M. Involvement of tyrosine kinases and STAT3 in Humanin-mediated neuroprotection. Life Sci 2005; 77:3092–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pflanz S, Timans JC, Cheung J, Rosales R, Kanzler H, Gilbert J, Hibbert L, Churakova T, Travis M, Vaisberg E, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JDet al. . IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4(+) T cells. Immunity 2002; 16:779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pflanz S, Hibbert L, Mattson J, Rosales R, Vaisberg E, Bazan JF, Phillips JH, McClanahan TK, Waal Malefyt R, Kastelein RA. WSX-1 and glycoprotein 130 constitute a signal-transducing receptor for IL-27. J Immunol 2004; 172:2225–2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshida H, Hamano S, Senaldi G, Covey T, Faggioni R, Mu S, Xia M, Wakeham AC, Nishina H, Potter J, Saris CJ, Mak TW. WSX-1 is required for the initiation of Th1 responses and resistance to L. major infection. Immunity 2001; 15:569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Villarino AV, Huang E, Hunter CA. Understanding the pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of IL-27. J Immunol 2004; 173:715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davis S, Aldrich TH, Valenzuela DM, Wong VV, Furth ME, Squinto SP, Yancopoulos GD. The receptor for ciliary neurotrophic factor. Science 1991; 253:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davis S, Aldrich TH, Stahl N, Pan L, Taga T, Kishimoto T, Ip NY, Yancopoulos GD. LIFR beta and gp130 as heterodimerizing signal transducers of the tripartite CNTF receptor. Science 1993; 260:1805–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ip NY, Nye SH, Boulton TG, Davis S, Taga T, Li Y, Birren SJ, Yasukawa K, Kishimoto T, Anderson DJ. CNTF and LIF act on neuronal cells via shared signaling pathways that involve the IL-6 signal transducing receptor component gp130. Cell 1992; 69:1121–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ip NY, McClain J, Barrezueta NX, Aldrich TH, Pan L, Li Y, Wiegand SJ, Friedman B, Davis S, Yancopoulos GD. The alpha component of the CNTF receptor is required for signaling and defines potential CNTF targets in the adult and during development. Neuron 1993; 10:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tormo AJ, Letellier MC, Lissilaa R, Batraville LA, Sharma M, Ferlin W, Elson G, Crabé S, Gauchat JF. The cytokines cardiotrophin-like cytokine/cytokine-like factor-1 (CLC/CLF) and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) differ in their receptor specificities. Cytokine 2012; 60:653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taga T, Kishimoto T. Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol 1997; 15:797–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boulay JL, O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Molecular phylogeny within type I cytokines and their cognate receptors. Immunity 2003; 19:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sreekumar PG, Ishikawa K, Spee C, Mehta HH, Wan J, Yen K, Cohen P, Kannan R, Hinton DR. The mitochondrial-derived peptide Humanin protects RPE cells from oxidative stress, senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016; 57:1238–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guo B, Zhai D, Cabezas E, Welsh K, Nouraini S, Satterthwait AC, Reed JC. Humanin peptide suppresses apoptosis by interfering with Bax activation. Nature 2003; 423:456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ikonen M, Liu B, Hashimoto Y, Ma L, Lee KW, Niikura T, Nishimoto I, Cohen P. Interaction between the Alzheimer's survival peptide humanin and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 regulates cell survival and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100:13042–13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ying G, Iribarren P, Zhou Y, Gong W, Zhang N, Yu ZX, Le Y, Cui Y, Wang JM. Humanin, a newly identified neuroprotective factor, uses the G protein-coupled formylpeptide receptor-like-1 as a functional receptor. J Immunol 2004; 172:7078–7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeChiara TM, Vejsada R, Poueymirou WT, Acheson A, Suri C, Conover JC, Friedman B, McClain J, Pan L, Stahl N, Ip NY, Yancopoulos GD. Mice lacking the CNTF receptor, unlike mice lacking CNTF, exhibit profound motor neuron deficits at birth. Cell 1995; 83:313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Duan Y, Jia Y, Wang T, Wang Y, Han X, Liu L. Potent therapeutic target of inflammation, virus and tumor: focus on interleukin-27. Int Immunopharmacol 2015; 26:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aparicio-Siegmund S, Garbers C. The biology of interleukin-27 reveals unique pro- and anti-inflammatory functions in immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2015; 26:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lucas S, Ghilardi N, Li J, de Sauvage FJ. IL-27 regulates IL-12 responsiveness of naive CD4+ T cells through Stat1-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100:15047–15052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mayer KD, Mohrs K, Reiley W, Wittmer S, Kohlmeier JE, Pearl JE, Cooper AM, Johnson LL, Woodland DL, Mohrs M. Cutting edge: T-bet and IL-27R are critical for in vivo IFN-gamma production by CD8 T cells during infection. J Immunol 2008; 180:693–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Batten M, Kljavin NM, Li J, Walter MJ, Sauvage FJ, Ghilardi N. Cutting edge: IL-27 is a potent inducer of IL-10 but not FoxP3 in murine T cells. J Immunol 2008; 180:2752–2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Salcedo R, Stauffer JK, Lincoln E, Back TC, Hixon JA, Hahn C, Shafer-Weaver K, Malyguine A, Kastelein R, Wigginton JM. IL-27 mediates complete regression of orthotopic primary and metastatic murine neuroblastoma tumors: role for CD8+ T cells. J Immunol 2004; 173:7170–7182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schneider R, Yaneva T, Beauseigle D, El-Khoury L, Arbour N. IL-27 increases the proliferation and effector functions of human naïve CD8+ T lymphocytes and promotes their development into Tc1 cells. Eur J Immunol 2011; 41:47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Artis D, Villarino A, Silverman M, He W, Thornton EM, Mu S, Summer S, Covey TM, Huang E, Yoshida H, Koretzky G, Goldschmidt Met al. . The IL-27 receptor (WSX-1) is an inhibitor of innate and adaptive elements of type 2 immunity. J Immunol 2004; 173:5626–5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Miyazaki Y, Inoue H, Matsumura M, Matsumoto K, Nakano T, Tsuda M, Hamano S, Yoshimura A, Yoshida H. Exacerbation of experimental allergic asthma by augmented Th2 responses in WSX-1-deficient mice. J Immunol 2005; 175:2401–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pot C, Apetoh L, Awasthi A, Kuchroo VK. Induction of regulatory Tr1 cells and inhibition of T(H)17 cells by IL-27. Semin Immunol 2011; 23:438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meka RR, Venkatesha SH, Dudics S, Acharya B, Moudgil KD. IL-27-induced modulation of autoimmunity and its therapeutic potential. Autoimmun Rev 2015; 14:1131–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Awasthi A, Carrier Y, Peron JP, Bettelli E, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M, Weiner HL. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:1380–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stumhofer JS, Silver JS, Laurence A, Porrett PM, Harris TH, Turka LA, Ernst M, Saris CJ, O'Shea JJ, Hunter CA. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:1363–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fitzgerald DC, Zhang GX, El-Behi M, Fonseca-Kelly Z, Li H, Yu S, Saris CJ, Gran B, Ciric B, Rostami A. Suppression of autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system by interleukin 10 secreted by interleukin 27-stimulated T cells. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:1372–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhai D, Luciano F, Zhu X, Guo B, Satterthwait AC, Reed JC. Humanin binds and nullifies Bid activity by blocking its activation of Bax and Bak. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:15815–15824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Luciano F, Zhai D, Zhu X, Bailly-Maitre B, Ricci JE, Satterthwait AC, Reed JC. Cytoprotective peptide humanin binds and inhibits proapoptotic Bcl-2/Bax family protein BimEL. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:15825–15835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.