Abstract

Several Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-negative Burkitt lymphoma-derived cell lines (for example, BL41 and Ramos) are extremely sensitive to genotoxic drugs despite being functionally null for the tumor suppressor p53. They rapidly undergo apoptosis, largely from G2/M of the cell cycle. 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine labeling experiments showed that although the treated cells can pass through S phase, they are unable to complete cell division, suggesting that a G2/M checkpoint is activated. Surprisingly, latent infection of these genotoxin-sensitive cells with EBV protects them from both apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, allowing them to complete the division cycle. However, a comparison with EBV-immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (which have functional p53) showed that EBV does not block apoptosis per se but rather abrogates the activation of, or signalling from, the checkpoint in G2/M. Furthermore, analyses of BL41 and Ramos cells latently infected with P3HR1 mutant virus, which expresses only a subset of the latent viral genes, showed that LMP-1, the main antiapoptotic latent protein encoded by EBV, is not involved in the protection afforded here by viral infection. This conclusion was confirmed by analysis of clones of BL41 stably expressing LMP-1 from a transfected plasmid, which respond like the parental cell line. Although steady-state levels of Bcl-2 and related proteins varied between BL41 lines and clones, they did not change significantly during apoptosis, nor was the level of any of these anti- or proapoptotic proteins predictive of the outcome of treatment. We have demonstrated that a subset of EBV latent gene products can inactivate a cell cycle checkpoint for monitoring the fidelity and timing of cell division and therefore genomic integrity. This is likely to be important in EBV-associated growth transformation of B cells and perhaps tumorigenesis. Furthermore, this study suggests that EBV will be a unique tool for investigating the intimate relationship between cell cycle regulation and apoptosis.

The majority of effective anticancer chemotherapeutic agents are genotoxins which work by causing DNA damage, either by directly modifying DNA or inhibiting DNA metabolic enzymes (18, 55). Such agents can activate several different biochemical pathways, including those featuring c-Abl tyrosine kinase, c-Jun amino-terminal kinases, and the tumor suppressor p53. However, because it appears to be activated in response to all genotoxic agents, p53 is widely considered to be the major sensor of genotoxic stress (8, 20, 37). Damage to DNA, the depletion of ribonucleotide pools, and hypoxia all lead to the accumulation and activation of nuclear p53. This increase in the stability of p53 appears to be the critical link between DNA damage, cell cycle checkpoints, and programmed cell death (apoptosis). Cells with wild-type p53 typically respond to genotoxic stress by arresting in G1 and sometimes G2/M of the cell cycle or undergoing apoptosis. Although the biochemical details of the G1 checkpoint are reasonably well understood, the precise roles of p53 in G2/M arrest and in the activation of apoptosis are far less clearly defined (6, 31, 35).

Mutation of p53 occurs in over half of human tumors (27), and such mutants are generally defective in the ability to induce growth arrest and apoptosis (31, 35). Moreover, since p53-deficient rodent cells are resistant to a diverse group of anticancer drugs and radiation, this led to the view that loss of the p53 apoptosis function is responsible for cross-resistance to anticancer agents (17, 38–40, 57).

Although the hypothesis that cells die from cancer treatment due to apoptosis largely controlled by wild-type p53 is very attractive, several reports suggest that the status of p53 does not always affect sensitivity to DNA-damaging drugs (5). Also, there have been a number of reports of tumor-derived cells which are null for p53 function but are readily induced to undergo apoptosis by genotoxic drugs and/or ionizing radiation. It is perhaps no coincidence that the cells studied were all of hematological origin: T-lymphoma cells from p53−/− mice (49), human promyelocytic leukemia HL60 cells (23), human Burkitt B-lymphoma cells (2), and human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (51) are all induced to undergo p53-independent apoptosis; in each case, it was concluded that this might be activated from a checkpoint in G2/M of the cell cycle.

Although the DNA damage response mechanisms in G2/M are well defined for yeast, relatively little is known about the molecular events in mammalian cells (24, 46, 55). It is assumed that G2/M cell cycle targets are largely conserved between yeast and mammals. The best example of this is in the control of G2-to-M progression. Recent studies have shown that tyrosine phosphorylation of the human Cdc2 prevents entry into mitosis in the presence of damaged or unreplicated DNA (4, 28). Furthermore, the human homologue of Chk1 is phosphorylated in response to DNA damage and binds to and phosphorylates human Cdc25C phosphatase. This allows binding of a 14-3-3 protein to Cdc25C which inactivates the latter and is thought to lead to a G2 arrest by preventing the dephosphorylation of Cdc2. However, DNA damage responses in mammalian cells are complex: other levels of G2 control (including p53 [6]) are thought to operate; in addition, mitotic checkpoints may be involved (46). The relationship between the induction of apoptosis and G2/M checkpoints is not well understood; nevertheless, survivin, an inhibitor of apoptosis protein, has recently been shown to counteract a default induction of apoptosis in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (36). Although this finding suggests that the control of apoptosis and progression of the cell cycle are intimately linked throughout the cycle, little is known about the molecular mechanisms which connect the two.

In vitro, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) can induce the continuous proliferation of a subset of resting human B cells. The resulting immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) are similar in phenotype to physiologically activated B lymphoblasts and express nine latent viral proteins: nuclear antigens EBNA1, -2, -3A, -3B, and -3C and EBNA-LP and the latent membrane proteins LMP-1, LMP-2A, and LMP-2B (29). In addition to inducing continuous cell division, it has been suggested that these latent proteins may also facilitate cell survival by suppressing the apoptotic program.

The first indication that EBV latent gene expression might enhance B-cell survival by antagonizing cell death, rather than inducing proliferation, came when it was realized that the sensitivity of type 1 Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cell lines (which express only EBNA1) and many EBV-negative BL cell lines when grown in vitro resulted from their tendency to suddenly undergo apoptosis if culture conditions were suboptimal. On the other hand, BL cells which had drifted in culture to a type 3 latency (expressing all of the known viral latency-associated proteins) were, like LCLs, relatively resistant to a variety of triggers of apoptosis, including serum deprivation and Ca2+ ionophores. Cultured EBV-negative BL cells converted to the latency type 3 state by infection with the B95-8 strain of EBV also became more resistant; however, those converted with the mutant P3HR1 virus (which fail to express EBNA2, EBNA-LP, and the latent membrane proteins) were not protected (22). Generally, BL type 1 cells express relatively little of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, and transfection of Bcl-2 could enhance the survival of these cells. The EBV gene capable of mimicking transfected Bcl-2 was the LMP-1 gene, and it appeared to do so by inducing endogenous Bcl-2 expression (26). Subsequently it was shown that LMP-1 may contribute to the survival of B cells latently infected with EBV by at least two other mechanisms. There are numerous reports that LMP-1 can activate the transcription factor NF-κB (15, 29), and one consequence of this is induction of the A20 zinc finger protein. A20 has been shown to provide protection from apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and it has been suggested that in epithelial cells it might suppress p53-mediated death (19, 32, 43). Also, there has been a report that LMP-1 can induce the expression of the inhibitor of apoptosis, Mcl-1 (56). A further link between LMP-1 and the death/survival apparatus was revealed when its association with TNF receptor (TNFR)-associated factors and its similarities to CD40 were elucidated (7, 11, 13, 30). LMP-1 may constitutively activate growth/survival signals via TNFR-associated factor molecules independently of TNFR or CD40 ligation and thus contribute to the suppression of apoptosis via pathways which involve neither Bcl-2, Mcl-1, nor A20.

DNA tumor viruses such as simian virus 40, adenovirus, and human papillomavirus encode oncoproteins which interact with the tumor suppressor p53. The function of p53 is suppressed by all three viral oncoproteins: p53 is inactivated by the simian virus 40 T antigen and by the adenovirus E1B 55K protein and is degraded in response to human papillomavirus type 16 E6 (53). In contrast, although EBV can very efficiently immortalize resting B cells to produce LCLs, there is no evidence to suggest that EBV gene expression interferes with the function of p53 in these continuously proliferating cells (2, 3, 10, 33, 45). During infection of normal human resting primary B cells, EBV gene expression activates transcription of the p53 gene to a level similar to that in mitogen-treated cells; this produces a normal, physiologically tolerable, low level of p53 which is compatible with proliferation. This process also primes the cells for activation of p53-mediated apoptosis if the proliferating B cells are subsequently treated with DNA-damaging drugs such as cisplatin (2, 3). It seems, therefore, that LMP-1 has antiapoptotic activity in certain situations but does not inhibit the p53-mediated DNA damage response in LCLs. Consistent with this failure of LMP-1 to universally suppress apoptosis, its expression in LCLs does not block Fas-mediated death (14).

Although EBV latent gene expression actually sensitizes LCLs to p53-mediated apoptosis initiated from G1/S, here we show that in converted BL cells—which are functionally null for p53—EBV can inhibit the activation of the apoptosis program from a G2/M checkpoint normally activated by genotoxic drugs. A function(s) of latent EBV either specifically protects against a p53-independent form of apoptosis or, more likely, abrogates the activation of or signalling from a G2/M cell cycle checkpoint. This activity neither involves nor requires LMP-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and genotoxin treatments.

Ramos BL cell line and the EBV P3HR1-converted lines AW-Ramos and EHRB-Ramos were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine, and 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL) and maintained at 37°C in a 10% CO2 incubator. All other cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine, and 10% Serum Supreme (BioWhittaker, Wokingham, United Kingdom) and maintained at 37°C in a 10% CO2 incubator. Cell lines were routinely fed at a dilution of 1:4; for experimental analysis, cells were diluted to a concentration of 3 × 105/ml 24 h prior to manipulation. Cisplatin (David Bull Laboratories, Mulgrave, Australia), doxorubicin (Pharmacia, Amersham, United Kingdom), etoposide (Bristol-Myers, Hounslow, United Kingdom), and camptothecin (Sigma, United Kingdom) were each titrated for ability to induce apoptosis by dose-response experiments in the BL41 cell line.

Viral infection of Ramos cells.

Cells (107) were incubated in 1 ml of EBV (purified by ultrafiltration from the marmoset B95.8 cell line) for 2 h at 37°C in a 10% CO2 incubator. Mock-infected cells were incubated in supplemented RPMI 1640 medium. All cells were then diluted to 106/ml overnight, and the total volume was diluted 1:3 in medium. After 3 days, cells were diluted to 3 × 105/ml before experimental manipulation.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, Complete protease inhibitor) for 10 min on ice. After centrifugation at 4°C for 10 min, the supernatant was removed and protein concentration was estimated colorimetrically using the Bio-Rad detergent-compatible assay. Then 50 μg of protein was added to an equal volume of 2× SDS protein sample buffer (60 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 2% [wt/vol], SDS, 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 2% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol, 2% bromophenol blue) and loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels [7.5% gels for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and p53; 12.5% for the Bcl-2 family of proteins; 10% for EBV antigens]. Gels were transferred for 4 h at 4°C onto a Protran nitrocellulose membrane. Nonspecific antibody binding was prevented by blocking in PBS–0.05% Tween 20–5% Marvel (PBS-M) for 1 h. After incubation with rabbit primary polyclonal antibody (PAb) overnight at 4°C, membranes were washed in changes of PBS–0.05% Tween 20 for a total of 1 h, incubated with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:2,000 in PBS-M) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 1 h, then washed as previously, and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) as recommended by the supplier.

For primary monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), an intermediate incubation with rabbit anti-mouse PAb (1:1,000) was performed before washing and addition of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:10,000) for 25 min before visualization.

Antibodies.

Rabbit PAb to PARP was from Boehringer Mannheim, Lewes, United Kingdom. Mouse MAb to Bcl-2 was from DAKO, High Wycombe, United Kingdom. MAb DO-1 to p53 was a gift from Xin Lu, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom.

PAbs to Bax (N-20) and Mcl-1 (S-19) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., San Diego, Calif. Anti Bcl-X PAb (AF800) was from R&D, Minneapolis, Minn. The MAb to EBNA2 (PE-2) was from DAKO. Human serum to the type II strain of EBV was a gift from Paul Farrell, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research. MAb S12 was used to detect LMP-1 (41), and MAb JF186 was used to detect EBNA-LP (16).

FACS analysis.

For estimation of population cell cycle distribution by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), cells were washed twice in PBS, spun at 2,000 rpm for 3 min, resuspended in 500 ml of ice-cold 70% ethanol, and resuspended in 500 ml of propidium iodide (PI) solution (18 μg of PI and 8 μg of RNase A per ml; stock reagents from Sigma) or stored at −20°C until analysis.

BrdU labeling.

Cells were incubated with 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (Sigma) at a concentration of 10 μM for 1 h, after which the pulse was washed out with prewarmed sterile PBS and cells were resuspended in fresh medium containing no label. Cisplatin was immediately added to the flasks, and 2 × 106 cells were harvested at each time point, centrifuged at 1,300 rpm for 5 min, washed twice in 2 ml of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, and resuspended in 500 μl of ice-cold 70% ethanol on ice for 30 min before storage at −20°C or direct analysis. Cells were washed in PBS before thorough resuspension in 750 μl of 2 N HCl containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature (RT) to denature the labeled, double-stranded DNA. Acid was neutralized by resuspending cells in 750 μl of 0.1 M sodium tetraborate (pH 8.5) and incubation at RT for 5 min. Cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 20 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, United Kingdom), which was then further diluted with 380 μl of 1% BSA–0.5% Tween 20–PBS. After incubation in the dark at RT for 30 min, cells were washed twice in 0.5% Tween 20–PBS and resuspended in 500 μl of PI solution.

Acridine orange staining.

A total of 8 × 104 cells were harvested, washed in PBS twice, and resuspended in acridine orange (1 μg/ml in PBS; Sigma) before mounting on slides (Shandon, Pittsburgh, Pa.) and visualization on a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) at 488 nm.

TUNEL.

For terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) analysis, cells were analyzed using an FITC in situ cell death detection kit (Boehringer Manheim). Briefly, 2 × 106 cells were harvested at each time point and resuspended in 200 μl of PBS. An equal volume of freshly made 2% formaldehyde–PBS solution was added, and cells were fixed for 30 min at RT with agitation. Cells were washed twice in PBS and stored in 500 μl of 80% ethanol until analysis. After washing in PBS, cells were permeabilized with 100 μl of 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate for 5 min on ice. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 90 min in a ratio of enzyme to FITC label solution as instructed by the manufacturer before a final wash in PBS and resuspension in PI solution. All analyses were performed on a FACSort flow cytometer using CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson).

EBNA-LP–TUNEL double staining.

One million cells were harvested from Ramos or Ramos cells newly infected with EBV prior to and 16 h after addition of cisplatin. Cells were washed in PBS, and cytospins of 8 × 104 cells were made. After air drying, cells were fixed in methanol-acetone (1:1) for 20 min at −20°C. After rehydration in PBS for 10 min, cells were permeabilized and analyzed by TUNEL as described above. Following two washes in PBS, cytospins were incubated with anti-EBNA-LP antibody JF186 (1:10) for 1 h, washed in PBS, and then incubated with tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (1:50) for 1 h. All antibody incubations were at RT in a humid chamber. After a final wash, slides were mounted in Citifluor (Citifluor, London, United Kingdom) and visualized for TUNEL and EBNA-LP positivity on a Zeiss Axiovert 100M confocal imaging microscope using excitation wavelengths of 488 and 543 nm, respectively. Images were processed using Zeiss LSM510 software.

RESULTS

Three BL-derived cell lines, BL41, Ramos, and Louckes, were previously identified as being very sensitive to cisplatin-induced apoptosis despite being functionally null for p53 (2). Due to mutation and loss of heterozygosity, the cells of all three lines express only a single p53 allele encoding a protein which is transcriptionally defective and, in the case of BL41 (p53, Arg248Gln) and Ramos (p53, Ile254Asp) has been shown to be defective for the induction of apoptosis when expressed ectopically (2). After 16 h of treatment with cisplatin, these BL-derived cells did not appear to arrest in G1 after treatment with cisplatin, nor was a significant sub-G1 population—normally characteristic of apoptosis—revealed by flow cytometry (2). The data were consistent with earlier reports that cisplatin could sometimes induce apoptosis from G2 in some murine tumor cells (48). In the present study, initially BL41 and then Ramos cells were used to investigate further the nature of this p53-independent apoptosis which is induced by cisplatin and apparently activated in G2 or M of the cell cycle.

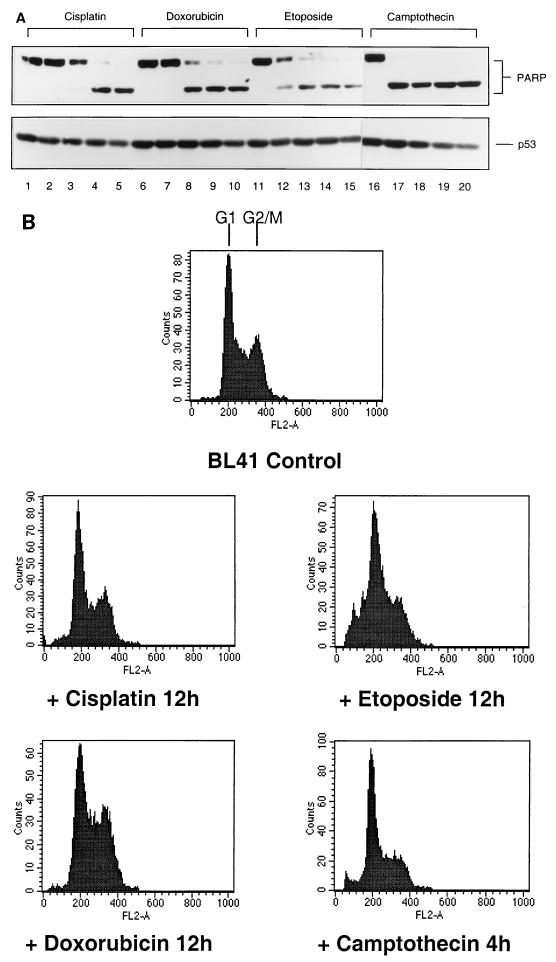

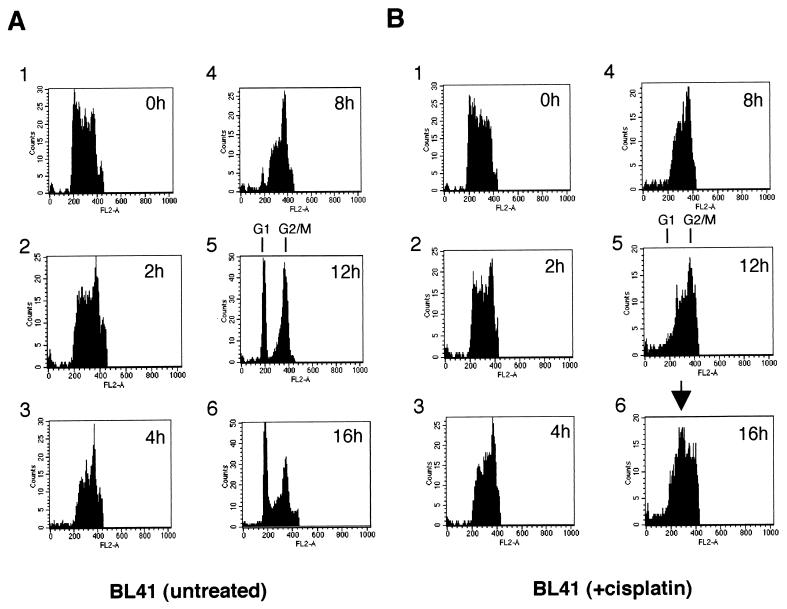

Various genotoxic drugs induce PARP cleavage but not a significant sub-G1 population in BL41 cells.

Various recent reports have shown that activation of CPP32 (Yama or caspase 3) is increased in many cells undergoing apoptosis, and the proteolytic cleavage of one of its substrates, PARP, is now widely accepted as a hallmark of apoptosis (9, 25, 52). To determine whether the apoptosis which is apparently associated with G2/M in BL41 cells was characterized by cleavage of PARP and also generally associated with DNA damage in these cells, we performed experiments with cisplatin and three other genotoxic drugs and analyzed the results by Western blotting. Doxorubicin (adriamycin; which cross-links DNA), etoposide (a DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor), and camptothecin (a DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor) were all tested for their effect on BL41 cells. All four drugs induced nearly complete or complete proteolytic cleavage of PARP from 110 to 89 kDa within 12 h or less (Fig. 1A). Samples of the cells from the time point first showing 100% cleavage of PARP were collected, stained with PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 1B). It should be noted that by this time the majority of cells in each drug-treated culture also appeared apoptotic by morphological criteria (data not shown and Fig. 6B, center panel).

FIG. 1.

Various genotoxic drugs induce PARP cleavage but not necessarily a sub-G1 population in FACS analysis. BL41 cells were treated for 16 h with genotoxins (cisplatin, 10 μg/ml; doxorubicin, 5 μg/ml; etoposide, 10 μg/ml; camptothecin, 3 μg/ml). (A) Cells were harvested at 4-h intervals and assessed for PARP cleavage by Western blotting: (0 h [tracks 1, 6, 11, and 16], 4 h [tracks 2, 7, 12, and 17], 8 h [tracks 3, 8, 13, and 18], 12 h [tracks 4, 9, 14, and 19], and 16 h [tracks 5, 10, 15, and 20]). (B) Samples were also subjected to FACS analysis for cell cycle distribution. Cell cycle profiles corresponding to time points at which PARP cleavage was judged to be 100% are shown.

FIG. 6.

(A) Electronically gated BrdU-labeled BL41/B95.8 cells. The data presented in Fig. 5 were electronically gated as described for Fig. 2. Note the reemergence of a BrdU-labeled G1 population of cisplatin-treated BL41/B95.8 cells (right column, 12h and 16h) which is absent in treated parental BL41 cells (middle column). (B) Morphology as shown by acridine orange staining. BL41 cells treated with cisplatin for 16 h (center) all have a characteristic apoptotic morphology. Untreated BL41 and cisplatin-treated BL41/B95.8 cells show the regular nuclear morphology of healthy proliferating B cells.

As with cisplatin treatment, these apoptotic cells produced cell cycle profiles which were very similar to those of the proliferating, untreated BL41 cells (Fig. 1B, top panel). The exception in this particular experiment were the cells treated with etoposide, which showed a minor increase in the sub-G1 population (<10%)—but by the criterion of PARP cleavage, 100% of these cells were already apoptotic. All of these data are consistent with cisplatin, doxorubicin, etoposide, and camptothecin activating p53-independent apoptosis late in the cell cycle, in G2 or mitosis, when the cells have duplicated their DNA and have a 4N content. Activation of this checkpoint is not restricted to cisplatin but appears to be generally associated with chemical agents which induce DNA strand breaks.

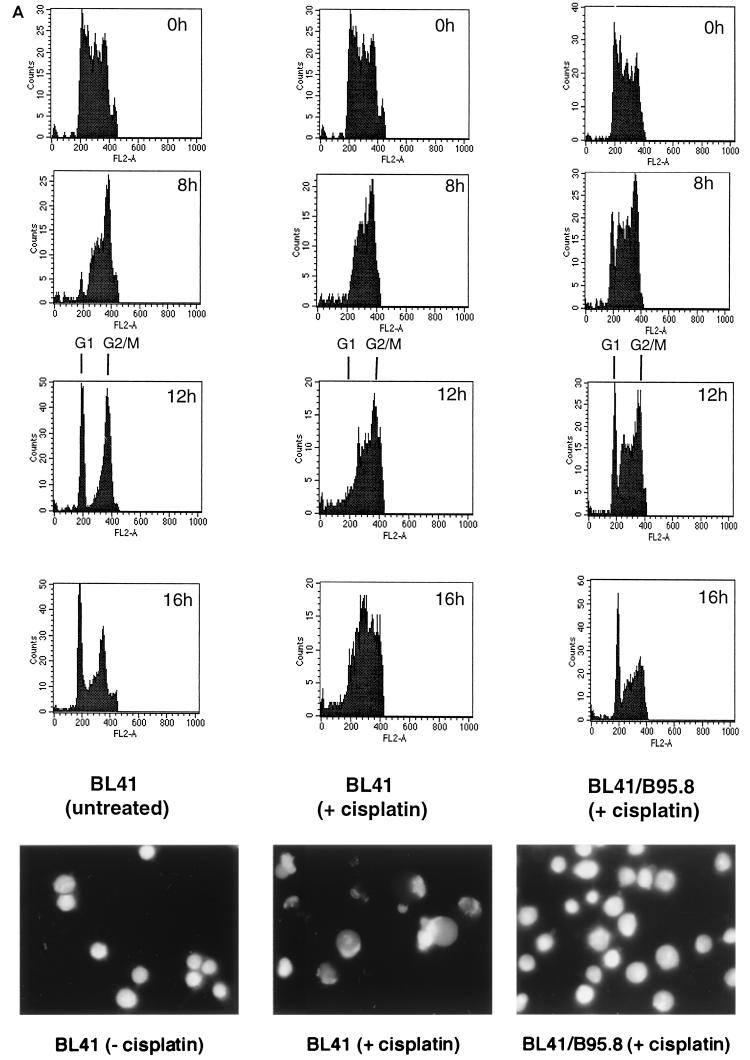

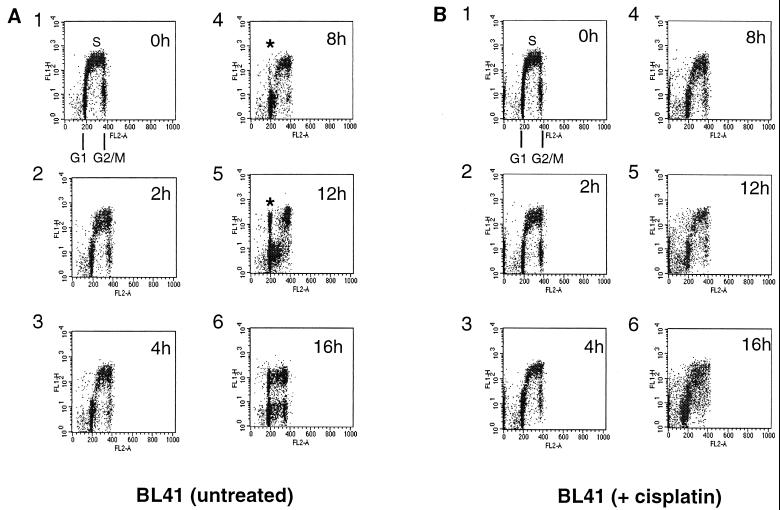

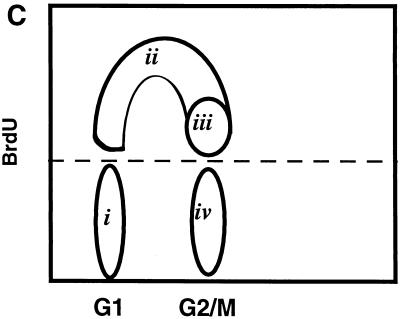

BL41 cells treated with cisplatin after BrdU incorporation pass through S phase but do not reenter G1.

To investigate further the nature of these cell cycle phenomena, a multiparameter flow cytometric assay was devised to establish more precisely the fate of BL41 cells after treatment with cisplatin. Cells were incubated for 1 h in growth medium containing BrdU; after the excess BrdU was washed out, the cells were placed back in normal medium. After further incubation with or without cisplatin, cells were stained with an FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody to identify cells undergoing DNA synthesis during the pulse period and PI to stain the total DNA and show their cell cycle distribution. An example of such an experiment is shown in Fig. 2. The proliferating, untreated BL41 cells shown in Fig. 2A, panel 1 (0h), were replaced in normal growth medium after a 1-h BrdU pulse. The cells which were synthesizing DNA during this labeling period can be seen as the FITC-positive S-phase population. These cells are shown schematically as ii and iii in Fig. 2C. During the following 12 h, this labeled population of cells passes through G2/M; the cells undergo cytokinesis, complete cell division, and reappear as a BrdU-labeled G1 (2N) population. Some of this population then enters a second S phase (since BrdU-labeling) between 12 and 16 h (Fig. 2A, panels 5 and 6).

FIG. 2.

After treatment with cisplatin (10 μg/ml), BL41 cells pass through S phase but do not divide and reenter G1. BL41 cells were pulsed with BrdU and harvested at time intervals shown in the top right of each plot prior to staining with FITC-labeled anti-BrdU antibody (y axis) and PI (x axis). (A) Untreated cells. An asterisk indicates cells which have traversed S and completed mitosis since the start of the experiment. (B) Cells incubated in the presence of cisplatin. Note the absence of cells which have completed mitosis. (C) Schematic diagram of asynchronously growing cells labeled with BrdU. (i) G0/G1 cells which did not incorporate BrdU during the labeling period; (ii) labeled cells in early- and mid-S phase; (iii) cells in late S phase and G2/M; (iv) unlabeled cells in G2/M. The area above the dotted line was electronically gated to examine progression of S-phase cells through the cell cycle during the course of the subsequent experiments.

Figure 2B shows the cells which were treated with cisplatin after the BrdU pulse. At 4 h, there is little difference between this population and the untreated population (compare Fig. 2A, panel 3, with Fig. 2B, panel 3). In contrast, by 8 h it is apparent that cisplatin treatment prevents the cells from completing cell division; a BrdU-labeled G1 does not emerge. This is even more pronounced by 12 h (compare Fig. 2B, panel 5, with Fig. 2A, panel 5).

After 16 h, the untreated cells can be seen as two discrete populations, labeled and unlabeled, each distributed in all phases of the cell cycle. However, the cells treated with cisplatin appear to be accumulating in S phase, and the unlabeled G1 population is apparently increasing. At this stage, by the criteria of PARP cleavage and morphology (see Fig. 6B, center panel), most of these cells have undergone apoptosis. We conclude that this distribution of cells must have derived from 4N cells in which chromatin condensation has occurred and nuclease has been activated, and as a consequence the DNA has a reduced affinity for both PI and anti-BrdU antibody. The apparently expanded G1 population in fact consists largely of 4N cells with an apoptotic morphology.

When the cells which stained positive for BrdU were electronically gated (as shown schematically in Fig. 2C) and plotted as a cell cycle histogram (cell number versus PI staining), the emergence of a labeled G1 is very obvious in the untreated cells. The increase in an apoptotic population derived from 4N (G2/M) cells, which becomes superimposed on S phase (indicated with an arrow in Fig. 3B, panel 6) and to a lesser degree the G1 phase, becomes very obvious in the cisplatin-treated cells (compare panels 6 in Fig. 3A and B and also Fig. 2A and B).

FIG. 3.

BL41 cells treated with cisplatin fail to complete mitosis and instead undergo apoptosis. Cells were electronically gated as described for Fig. 2C. A significant proportion of untreated BrdU-labeled BL41 cells (A) have returned to G1 phase by 12 h, while BL41 cells treated with cisplatin (B) are unable to complete mitosis (compare graphs 5 in panels A and B). The apparent increase in cells in S phase (indicated with an arrow) in graph 6 is derived from cells which have undergone apoptosis from G2/M.

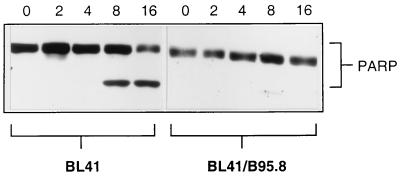

BL cells latently infected with B95.8 EBV are protected from apoptosis induced by genotoxins.

Latent infection with EBV has been shown to protect some EBV-negative BL cells from apoptosis induced by either reduced serum or the action of Ca2+ ionophores. The EBV protein largely thought to be responsible for this antiapoptotic activity is LMP-1 (see the introduction). However, we previously showed that expression of the same complement of latent EBV genes (see the introduction and below) does not protect EBV-immortalized B-LCLs, which are wild type for p53, from apoptosis induced by a range of genotoxins (2, 3). To investigate the effect of EBV on the p53-independent apoptosis seen in BL41, we treated cells stably infected with the B95.8 strain of EBV with cisplatin and compared their response with that of the parental line. As expected, Western blot analysis of BL41 showed considerable proteolytic cleavage of PARP by 8 h after addition of cisplatin. However, even after 16 h of exposure to cisplatin, Western blots of the converted BL41/B95.8 cells showed no trace of PARP cleavage (Fig. 4). Consistent with these cells failing to undergo apoptosis, very few, if any, cells with the distinctive morphology of apoptotic lymphocytes were detected by microscopic examination of the cultures up to 20 h after addition of cisplatin (Fig. 6B, right panel). By these criteria, EBV latent gene expression had prevented apoptosis induced by this genotoxin. Similar experiments performed with doxorubicin, etoposide, and camptothecin produced similar results: protection from genotoxin-induced apoptosis by EBV (data not shown). However, it should be noted that these EBV-carrying cells are capable of undergoing apoptosis in response to other stimuli such as ceramide and H2O2 (our unpublished observations).

FIG. 4.

EBV protects against cisplatin-induced apoptosis. BL41 and BL41/B95.8 cells were incubated with cisplatin (10 μg/ml), harvested at 4-h intervals, and assessed for PARP cleavage by Western blotting. Note the complete absence of PARP cleavage even at 16 h in the EBV-positive cells. The BL41/B95.8 cells used were judged to be 100% EBV positive by immunofluorescence staining with an anti-EBNA-LP MAb (not shown).

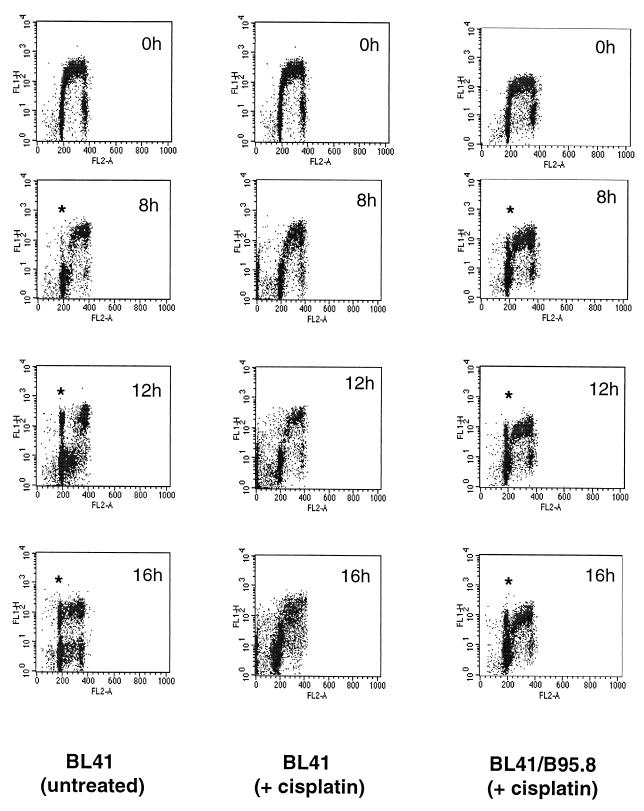

EBV latent gene expression suppresses the G2/M checkpoint.

To determine the effect of EBV latent gene expression on the cell cycle responses to genotoxic damage, we performed further experiments in which the behavior of the BrdU-labeled cells was monitored in the presence and absence of cisplatin. BL41/B95.8 cells were pulse-labeled as described above, and then cisplatin was added to half of the sample. The outcome of treatment can be compared with similar treatment of BL41 cells and with untreated BL41 cells in Fig. 5 and 6A. Sixteen hours after the addition of cisplatin, the labeled, EBV-infected BL41/B95.8 cells have reemerged from G2/M to produce a BrdU-positive G1 population similar to that seen in the untreated BL41 cells. Expression of EBV latency genes in these BL-derived cell lines produces cells in which the G2/M checkpoint is apparently suppressed. The cells behave almost as if cisplatin had not been added to the medium since a significant proportion of the population complete the cell division cycle (see also Fig. 9A, bottom left-hand panel). It should be noted that anti-EBNA-LP immunofluorescence staining showed that 100% of the BL41/B95.8 cells were latently infected with EBV (data not shown). Figure 6B shows that 16 h posttreatment, BL41 cells are almost exclusively apoptotic and therefore cannot be cycling (Fig. 6B, compare left and middle panels), while BL41/B95.8 cells appear morphologically normal at the same time point (Fig. 6B, right panel).

FIG. 5.

BL41/B95.8 cells complete cell division after treatment with cisplatin (10 μg/ml). While by 12 h a significant proportion of untreated BL41 cells have completed mitosis (asterisk, 12 h), cisplatin-treated cells are unable to do so and instead undergo apoptosis (middle column). However, latent infection with EBV allows BL41 cells to complete mitosis in the presence of cisplatin (right column).

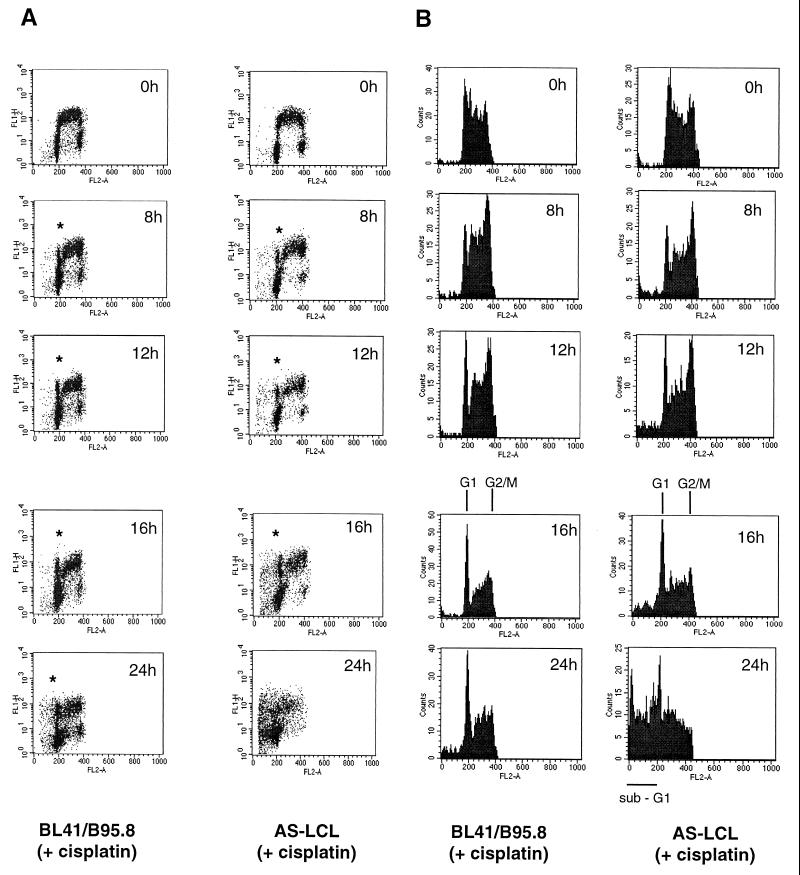

FIG. 9.

LCLs treated with cisplatin (10 μg/ml) also traverse G2/M but subsequently die from G1/S. BrdU labeling experiments were as described for Fig. 2. (A) Both BL41/B95.8 cells and AS-LCL cells are able to complete mitosis in the presence of cisplatin (indicated by asterisks). (B) The appearance of cells with G1 DNA content after electronically gating confirmed this. However, AS-LCLs (presumably due to activation of p53 at the G1/S transition) subsequently undergo apoptosis and exhibit a sub-G1 distribution (B, 24h, right column).

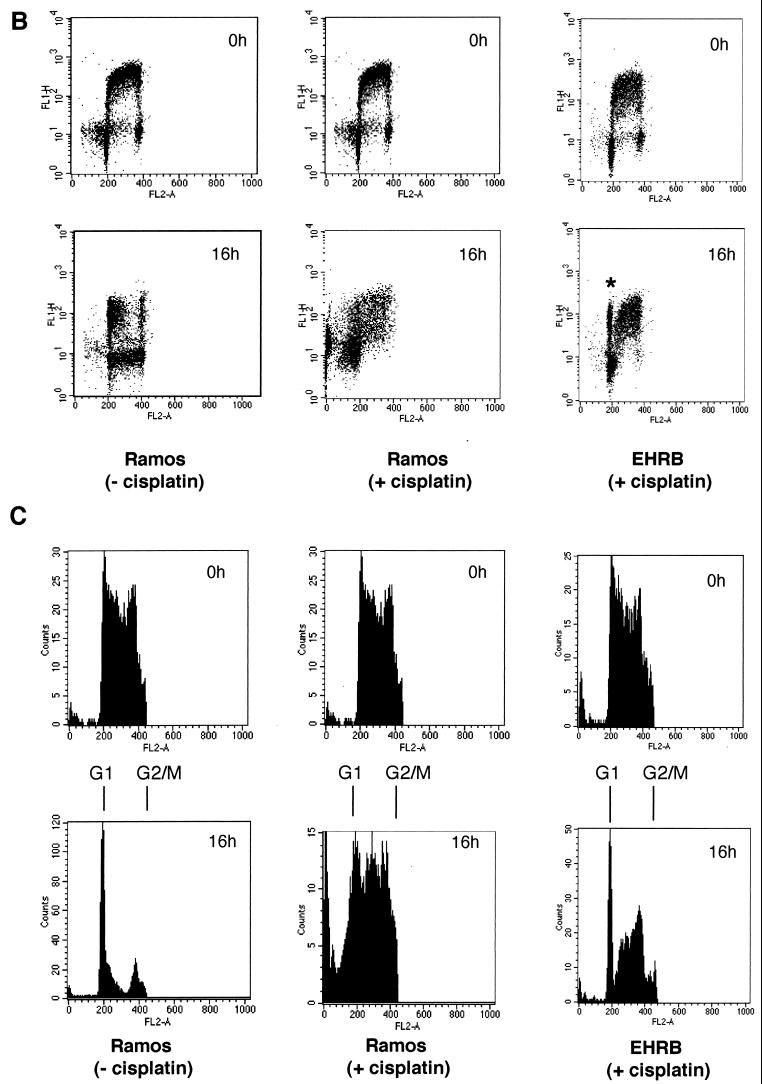

De novo infection of Ramos cells with EBV confers resistance to cisplatin-induced apoptosis.

To eliminate the possibility that protection in the established cell lines was due to an unknown selection process occurring after infection, we infected both BL41 and another cisplatin-sensitive BL cell line, Ramos, with the B95.8 strain of EBV and evaluated their response to cisplatin 72 h after infection. There was no significant increase in cell death in the infected cell cultures compared to mock-infected cells, and infection of Ramos cells consistently yielded a higher percentage of EBV-positive cells than infection of BL41 cells (data not shown); therefore, B95.8-infected Ramos cells were chosen for further investigation.

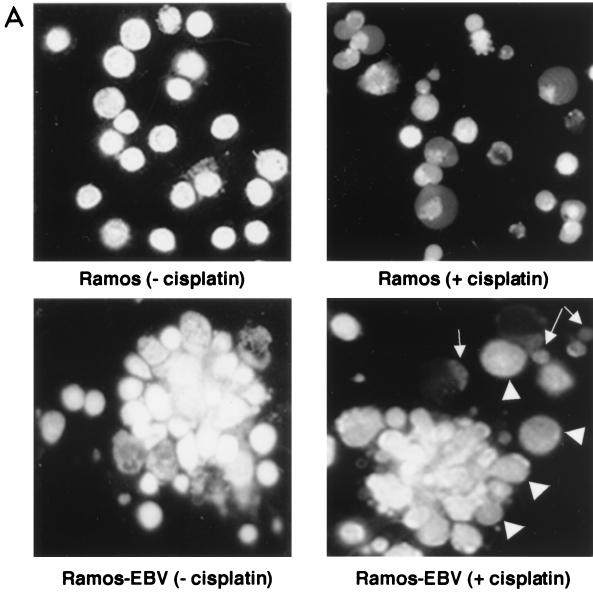

Untreated parental Ramos cells were morphologically normal after acridine orange staining (Fig. 7A, upper left panel), while the untreated, EBV-infected Ramos (Ramos-EBV) culture exhibited significant numbers of cell aggregates, reminiscent of the phenotype induced by infection of primary B cells with EBV (Fig. 7A, lower left panel). Upon treatment with cisplatin, nearly all parental Ramos cells appeared apoptotic (Fig. 7A, upper right panel). In the Ramos-EBV culture, although there were a number of cells showing nuclear condensation characteristic of apoptosis (Fig. 7A, lower right panel), occasional single cells and the majority of cells within the aggregates appeared morphologically normal (Fig. 7A, lower right panel). This suggested that infection of Ramos with EBV afforded protection against cisplatin-induced apoptosis.

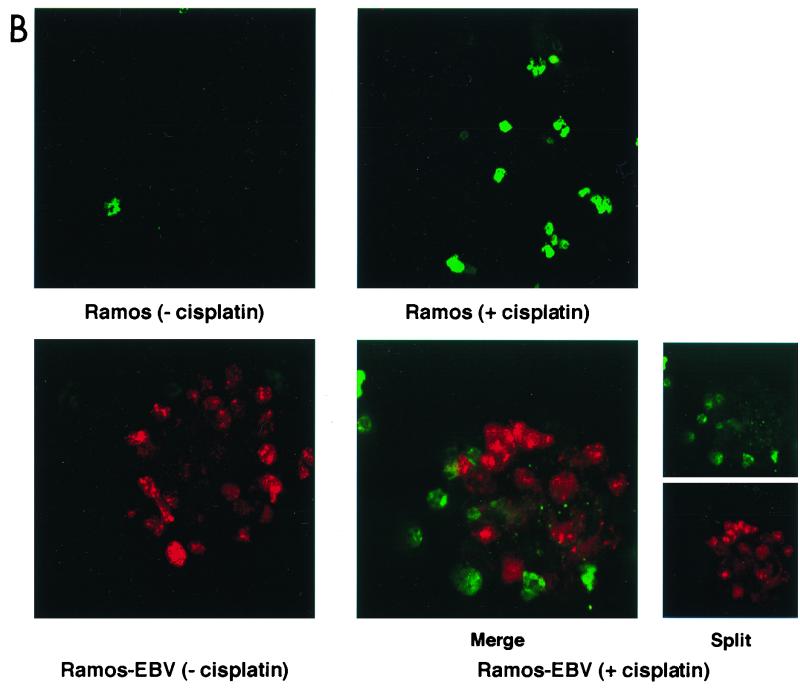

FIG. 7.

De novo infection of Ramos cells with B95.8 EBV confers resistance to cisplatin-induced apoptosis. (A) Cells were harvested and stained with acridine orange before (left) or 16 h after (right) incubation with cisplatin. Note the aggregation of cells in the infected Ramos culture which is characteristic of EBV infection of B cells (lower left). While uninfected Ramos cells treated for 16 h with cisplatin (upper right) are almost all apoptotic, cells within the aggregates in the infected cells appear morphologically normal (lower right, arrowheads), with occasional single apoptotic cells (arrows). (B) Confocal microscopy after dual staining of parental Ramos (upper panels) and infected Ramos (lower panels) cells with TUNEL for apoptosis (green) and EBNA-LP as a marker of EBV gene expression (red). The majority of parental, uninfected Ramos cells are TUNEL positive after treatment with cisplatin (upper right). In the Ramos-EBV cells treated with cisplatin, there was no colocalization of TUNEL and EBNA-LP staining (merged image, lower right panels). The split image clearly shows that cellular TUNEL and EBNA-LP staining are mutually exclusive and that the effect was not simply due to a masking of one fluorescence with the other.

Figure 7B shows the result of double staining infected and uninfected cells for apoptosis using TUNEL (green) and for the presence of EBV with an antibody directed against EBNA-LP, an early marker of EBV infection (red). Strikingly, the majority of EBNA-LP staining in untreated Ramos-EBV cells was found in cells within the aggregates (Fig. 7B, lower left panel), suggesting that the aggregation observed in acridine orange-stained Ramos-EBV cells was indeed a consequence of viral infection. Although there was a very low level of apoptosis in uninfected Ramos cells (Fig. 7B, upper left panel), after 16 h of treatment with cisplatin, there was a 14-fold increase in TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 7B, upper right panel, and data not shown). In the Ramos-EBV culture, TUNEL positivity increased only fourfold after treatment and was detected only in EBV-negative cells; conversely, EBV-positive cells were always negative for TUNEL staining (Fig. 7B, lower right panels, merged and split images). This pattern of staining was also evident in cells not localized to aggregates (data not shown). The EBV-positive cell aggregates appeared similar in untreated and treated Ramos-EBV (Fig. 7B, compare lower panels). The mutually exclusive pattern of EBNA-LP and TUNEL staining clearly demonstrates that the presence of EBV can protect against genotoxin-induced apoptosis in these cells.

EBV does not protect against apoptosis per se.

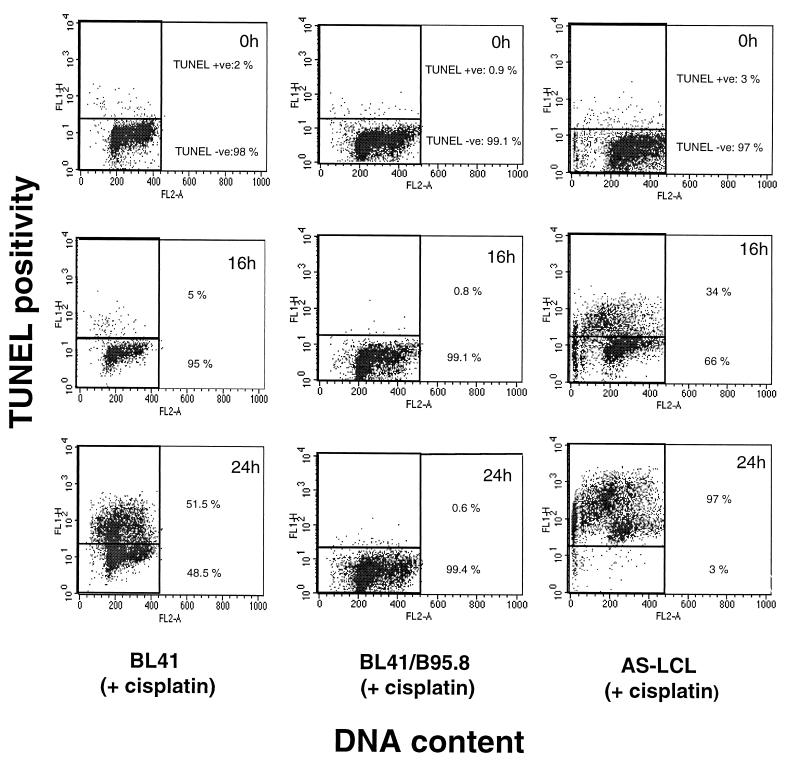

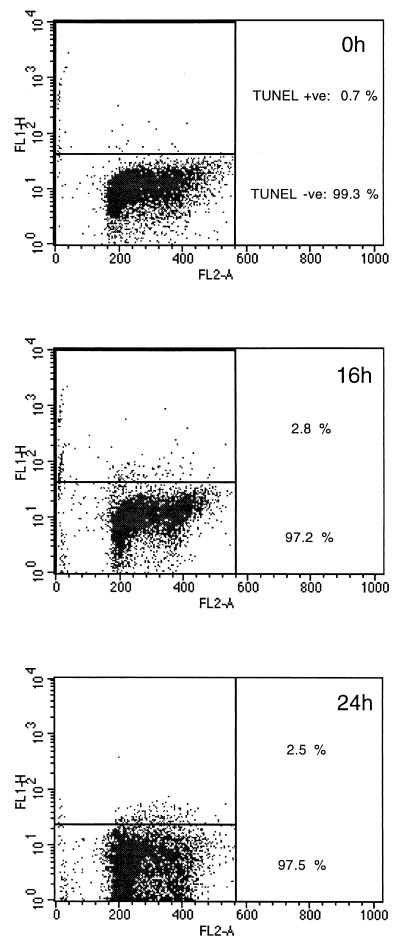

The data shown in Fig. 8 again demonstrate that EBV does not protect from the consequences of DNA damage in all B cells. TUNEL analysis performed here confirmed our previous observations that LCLs may die quite rapidly by apoptosis in response to cisplatin (Fig. 8) (2, 3). Although AS-LCLs express the same group of EBV genes as the B95.8-converted BL lines, they are almost 100% TUNEL positive 24 h after treatment with cisplatin (Fig. 8, right panels). In contrast, BL41/B95.8 cells, after a similar exposure to the drug, remain completely negative for TUNEL staining (Fig. 8, middle panels). In the p53-positive setting of LCLs, EBV does not suppress apoptosis.

FIG. 8.

EBV cannot prevent genotoxin-induced apoptosis per se. In an independent measure of apoptosis, cells were treated with cisplatin (10 μg/ml) before harvesting at the indicated time points and assessed for apoptosis (y axis) using FITC-labeled nucleotide incorporation (the TUNEL assay) and DNA content using PI (x axis). Consistent with PARP cleavage data (Fig. 4), BL41/B95.8 cells are protected against cisplatin-induced apoptosis (compare middle and left columns). However, expression of the same viral latent genes in the lymphoblastoid cell line AS-LCL (right column) is unable to protect these cells from genotoxin-induced apoptosis.

LCLs also traverse G2/M but subsequently die from G1/S.

Normal human B cells stimulated by mitogens (e.g., interleukin-4 and anti-CD40) arrest in both G1 and G2/M when exposed to cisplatin, but LCLs treated in the same way undergo apoptosis largely from the G1/S boundary (2, 3). Since LCLs express the same set of EBV latent genes as BL41/B95.8, a prediction based on the experiments described above is that a significant number of LCLs will complete cell division after cisplatin treatment; EBV should be able to override the G2/M checkpoint(s). Figure 9 illustrates that this is indeed the case. Sixteen hours after treatment with cisplatin, a BrdU-labeled population of AS-LCLs are able to complete cell division and cells emerge as a labeled G1 population in a way which is almost indistinguishable from the behavior of BL41/B95.8. However, between 16 and 24 h, the LCLs which have completed cell division then undergo apoptosis from G1 and so produce a significant sub-G1 peak in the flow cytometric analysis of the BrdU-labeled and unlabeled populations (Fig. 9, bottom panels).

LMP-1 expression is neither sufficient nor necessary to protect BL cells from apoptosis or G2/M arrest induced by genotoxins.

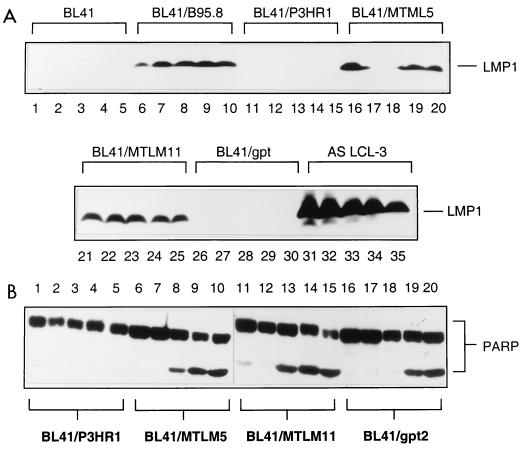

As outlined above, EBV LMP-1 has been reported to protect cells from apoptosis. It has been suggested variously that this is because LMP-1 can induce the expression of antiapoptotic factors Bcl-2 (26, 42), A20 (19, 32), and Mcl-1 (56) and/or because it can mimic ligation of CD40 at the surface of B cells (7, 30). To investigate the role of LMP-1 in the repression of the p53-independent apoptosis and/or cell cycle arrest described here, the responses of various sublines of BL41 to cisplatin were examined. The expression of LMP-1 in various lines analyzed in this study is shown in Fig. 10A.

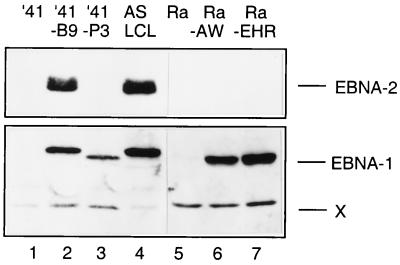

FIG. 10.

LMP-1 is not required or necessary for protection. (A) Western blots showing LMP-1 was not expressed in uninfected BL41 cells (tracks 1 to 5), cells infected with P3HR1 virus (tracks 11 to 15), or cells transfected with empty vector (tracks 26 to 30) but was expressed at constant levels in cells infected with B95.8 virus (tracks 6 to 10) and cells transfected with LMP-1 expression vectors, BL41/MTLM-5 (tracks 16 to 20) and BL41/MTLM-11 (tracks 21 to 25) (54). The level of LMP-1 expression in an LCL is shown for comparison (tracks 31 to 35). The apparent lack of expression in tracks 17 and 18 resulted from faulty transfer of protein to the nitrocellulose filter. Each set of five lanes represents a time course over 16 h after the addition of cisplatin. Samples were taken every 4 h. (B) Western blots showing PARP cleavage from the same time course. BL41/MTLM-5 and -11 cells expressed levels of LMP-1 similar to the level produced by BL41/B95.8 and were as sensitive to cisplatin-induced apoptosis as the empty vector control, BL41/gpt. Conversely, BL41/P3HR1 cells expressed no LMP-1; they were protected against cisplatin-induced apoptosis.

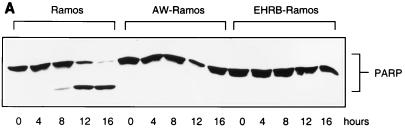

As judged by the cleavage of PARP (Fig. 10B) and examination of cell morphology (data not shown), two clones of BL41—which express LMP-1 from stably maintained plasmids—are as prone to undergo apoptosis when treated with cisplatin as a vector-transfected control clone and the parental BL41 cells (Fig. 10B, compare BL41/MTLM5 and BL41/MTLM11 with BL41/gpt and with BL41 in Fig. 1A). Although the level of LMP-1 expressed in these lines is much lower than in LCLs, it is comparable to that detected in BL41/B95.8 (Fig. 10A). In a parallel experiment, a subline of BL41 converted with the P3HR1 strain of EBV appeared to be protected from apoptosis as efficiently as one converted with B95.8 virus. This was confirmed by TUNEL analysis (Fig. 11). BL41/P3HR1 cells express neither LMP-1 nor the main viral transactivator protein, EBNA2 (see also Fig. 13). The ability of P3HR1 virus to protect as well as B95.8 was confirmed in two Ramos sublines converted with P3HR1 virus: AW-Ramos and EHRB-Ramos. Both of these cell lines also fail to undergo apoptosis, as judged by PARP cleavage (Fig. 12A) and morphology (data not shown) or arrest in G2/M (Fig. 12B and C) after treatment with cisplatin. The patterns of EBNA expression (Fig. 13) validated the various lines as being converted with the appropriate virus.

FIG. 11.

The P3HR1 strain of EBV prevents apoptosis in BL41 cells, as judged by TUNEL assay. Independent confirmation that P3HR1 virus protects against genotoxin-induced apoptosis was obtained using the TUNEL assay as described for Fig. 8. Note complete absence of TUNEL positivity even 24 h after treatment.

FIG. 13.

Western blots of sublines to validate the viral strains in the latently infected cells. The B95.8 strain of EBV expresses the nuclear antigens EBNA1 and EBNA2, and these were detected in both BL41/B95.8 and an LCL established with this virus (tracks 2 and 4, respectively). P3HR1 does not express EBNA2 due to a genomic deletion; the presence of virus was instead confirmed by immunoblotting infected BL41 and Ramos BL cell lines with human serum which detected EBNA1 (tracks 3, 6, and 7). It should be noted that an EBNA1 protein with an electrophoretic mobility slightly faster than that from B95.8 (X) is characteristic of a cross-reactive cellular protein recognized by the human serum.

FIG. 12.

The P3HR1 strain also prevents apoptosis and allows cell division in Ramos cells treated with cisplatin (10 μg/ml). (A) A Western blot showed that although Ramos cells were sensitive to cisplatin-induced apoptosis as measured by PARP cleavage, two independent sublines of Ramos infected with the P3HR1 strain of EBV (AW- and EHRB-Ramos) were protected over the same 16-h time course. (B) After exposure to cisplatin, Ramos cells fail to complete mitosis [compare 16h Ramos (+ cisplatin) and (− cisplatin)], whereas the P3HR1 EBV-infected EHRB-Ramos cell line is able to complete mitosis [EHRB (+ cisplatin); the asterisk indicates the labeled G1 cells]. (C) Cell cycle profiles of BrdU-labeled populations were electronically gated as described for Fig. 2.

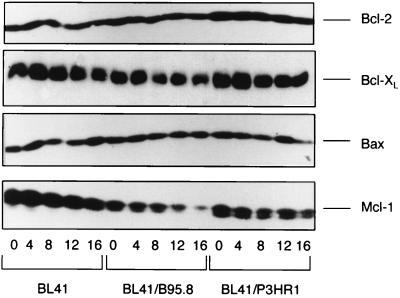

The levels of Bcl-2 and related proteins do not change when BL41 cells undergo apoptosis, and they are not predictive of the outcome of drug treatment.

It has been shown that the stoichiometry of interactions between Bcl-2 family members can determine whether cells survive or die following apoptotic stimuli (50). Moreover, expression of latent EBV genes can in certain circumstances induce the expression of Bcl-2, Mcl-1, and A20 (see above). To determine whether the sensitivity to cisplatin of BL41 and the two converted lines (BL41/B95.8 and BL41/P3HR1) was related to the level of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bax, or Mcl-1 that each expresses, a series of Western blot analyses were performed. The results revealed that there was no significant difference in the levels of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, or Bax, either in comparison of the parental BL41 with the converted cells or following treatment of each with cisplatin (Fig. 14). A significant reduction in the level of Mcl-1 was detected in the converted lines relative to the parental BL41, and consistently we saw a modest depletion of Mcl-1 protein in all three lines following treatment with cisplatin (Fig. 14). Since a reduction occurred in the resistant converted cells to a similar degree as in the parental line, this phenomenon is clearly not directly linked to apoptosis. We conclude that the levels of these Bcl-2-related proteins was not predictive of the outcome of drug treatment. However, it should be noted that it was not possible to measure the levels of A20 protein because no suitable antibody was available.

FIG. 14.

Western blots showing the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins. BL41 and BL41 cell lines infected with the B95.8 or P3HR1 strain of EBV were exposed to cisplatin (10 μg/ml) for 16 h, and levels of Bcl-2 and related proteins was determined from samples taken at 4-h intervals. Levels of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL and the proapoptotic protein Bax are similar and remain unchanged in all three cell lines during the experiment. The levels of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 decreased slightly in all three cell lines.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that in at least two Burkitt lymphoma-derived cell line genotoxins activate a G2/M checkpoint which prevents the completion of cell division and triggers the apoptosis program in a p53-independent manner. We showed for the first time that the activation of this checkpoint—or the downstream signalling pathway to the apoptosis molecular machinery—is specifically suppressed by expression of a subset of EBV latent gene products (see below). The cell lines which were investigated in detail (BL41 and Ramos) both express a single mutant p53 allele which is completely inactive for the wild-type functions of transactivation and apoptosis induction (2). Moreover, once it was clearly established that these cells underwent apoptosis from G2/M in response to cisplatin and that sublines latently infected with EBV completed cell division, it was possible to determine whether EBV could disrupt the checkpoint in p53-positive B cells. Although the checkpoint was actually revealed in a setting which is null for wild-type p53 function, we now believe that it can be activated in a p53-positive setting and that here also it is suppressed by EBV. Mitogen-stimulated normal cells arrest in both G1 and G2/M in response to genotoxins such as cisplatin (2). In contrast, B-LCLs which were immortalized by EBV failed to arrest in G2/M, suggesting that again EBV suppressed a checkpoint (Fig. 9). However, in the LCLs, because the p53 checkpoint is retained and therefore apoptosis occurs largely from G1/S, the suppression in this setting is revealed only by the multiparameter flow cytometry used here.

The nature of the p53-independent pathway which signals from damaged DNA to the apoptosis program has not been addressed in this study. However, the recent demonstration that cisplatin can induce two parallel death response pathways, one dependent on p53 and the other dependent on its close relative p73, merits consideration. Several reports (1, 21, 58) indicate that although p53 and p73 are regulated by distinct mechanisms, both are involved in DNA damage responses. The activation of p73 involves the c-Abl tyrosine kinase and also requires a functional DNA mismatch repair system. It is possible this pathway is activated in the p53-independent responses reported here for BL41 and Ramos and that it may be therefore a specific target of EBV. The status of p73, c-Abl, and the mismatch repair capability of these cell lines is currently under investigation. However, it should be noted that mutant p53 proteins, similar to those found in BL41 and Ramos, often bind to and inactivate p73 (12). A third parallel pathway cannot be discounted.

The effect of EBV infection in these cells is remarkably robust. For more than 24 h after treatment with highly damaging doses of each of four different genotoxic drugs, EBV gene expression appears to protect nearly 100% of cells from apoptotic death and allow the completion of mitosis and cytokinesis. This phenotype was seen in both B95.8- and P3HR1-infected cells from a variety of different laboratories. Furthermore, we have clearly shown that the protection by EBV was evident 3 days after infecting Ramos cells with the B95.8 strain of EBV (Fig. 7). These experiments convincingly show that EBV, and not selection in culture, is responsible for the resistant phenotype.

Since the expression of all known latent EBV genes in LCLs does not prevent apoptosis mediated by wild-type p53, we suggest that it is unlikely that the apoptosis machinery itself is being inhibited in these BL cells. The data are more consistent with some EBV gene product(s) interfering with a G2 phase or mitotic checkpoint which here is linked to a default apoptosis pathway. The target cellular molecules in this system are not known, although the Chk1/Cdc25C/Cdc2 pathway is an attractive candidate. Since P3HR1 virus protects as well as B95.8, several EBV genes can be eliminated as viral effectors (Table 1). EBNA2, LMP-2, and full-length EBNA-LP cannot be necessary, however; perhaps most surprising was the demonstration that LMP-1, the best-characterized antiapoptotic latent EBV protein, has no role in the protection shown here. Again this is consistent with EBV modulating cell cycle regulation rather than execution of the apoptosis program. In addition to EBNA1 and the EBNA3 family of proteins (3A, B, and C), the small untranslated EBV-encoded RNAs and the orphan BamHI region A rightward transcripts require investigation. One or a combination of these viral products has a previously unknown and unsuspected but profound effect on B-cell biology. Our recent observation that EBNA3C can interfere with a mitotic checkpoint may prove to be relevant in this context (44).

TABLE 1.

EBV gene expression in EBV-infected BL41 cells

| Genea | Expression

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BL41/P3HR1 | BL41/B95.8 | |

| EBNA1 | + | + |

| EBNA2 | − | + |

| EBNA-LP | − (truncated) | + |

| EBNA3A | + | + |

| EBNA3B | + | + |

| EBNA3C | + | + |

| LMP-1 | − | + |

| LMP-2b | − | + |

| BARTsb | + | + |

| EBERsb | + | + |

BARTs, BamHI rightward transcripts; EBERs, EBV-encoded RNAs.

Results not confirmed in this study.

The development of BL is multifactorial and very complex, and the precise role played by EBV is still controversial (34, 47). It is therefore difficult and perhaps premature to speculate on the role of EBV and the G2/M checkpoint in BL tumorigenesis. However, this study has highlighted an unforeseen mechanism through which EBV can modulate a cell cycle checkpoint or specifically inhibit the activity of downstream effectors. Such a checkpoint must be important for monitoring the timing and fidelity of cell division, and its modulation could therefore be very important in EBV-associated growth transformation of B cells. EBV should prove to be a unique tool for dissecting this aspect of cell proliferation and survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Rowe (Cardiff), G. Klein (Stockholm), C. Gregory (Nottingham), and Kirsten Knox (Oxford) for cell lines and G. J. Inman for helpful comments during preparation of the manuscript.

We are very grateful to the MRC for financial support through a Ph.D. studentship to M.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agami R, Blandino G, Oren M, Shaul Y. Interaction of c-Abl and p73alpha and their collaboration to induce apoptosis. Nature. 1999;399:809–813. doi: 10.1038/21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allday M J, Inman G J, Crawford D H, Farrell P J. DNA damage in human B cells can induce apoptosis, proceeding from G1/S when p53 is transactivation competent and G2/M when it is transactivation defective. EMBO J. 1995;14:4994–5005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allday M J, Sinclair A, Parker G, Crawford D H, Farrell P J. Epstein-Barr virus efficiently immortalizes human B cells without neutralizing the function of p53. EMBO J. 1995;14:1382–1391. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blasina A, Paegle E S, McGowan C H. The role of inhibitory phosphorylation of CDC2 following DNA replication block and radiation-induced damage in human cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1013–1023. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown J M, Wouters B G. Apoptosis, p53, and tumor cell sensitivity to anticancer agents. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1391–1399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, Waldman T, Zhou S, Brown J P, Sedivy J M, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1998;282:1497–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch L K, Bishop G A. The EBV transforming protein, latent membrane protein 1, mimics and cooperates with CD40 signaling in B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162:2555–2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canman C E, Kastan M B. Signal transduction. Three paths to stress relief. Nature. 1996;384:213–214. doi: 10.1038/384213a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casciola-Rosen L, Nicholson D W, Chong T, Rowan K R, Thornberry N A, Miller D K, Rosen A. Apopain/CPP32 cleaves proteins that are essential for cellular repair: a fundamental principle of apoptotic death. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1957–1964. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W, Cooper N R. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 and latent membrane protein independently transactivate p53 through induction of NF-κB activity. J Virol. 1996;70:4849–4853. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4849-4853.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devergne O, McFarland E C, Mosialos G, Izumi K M, Ware C F, Kieff E. Role of the TRAF binding site and NF-κB activation in Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1-induced cell gene expression. J Virol. 1998;72:7900–7908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7900-7908.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Como C J, Gaiddon C, Prives C. p73 function is inhibited by tumor-derived p53 mutants in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1438–1449. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eliopoulos A G, Dawson C W, Mosialos G, Floettmann J E, Rowe M, Armitage R J, Dawson J, Zapata J M, Kerr D J, Wakelam M J, Reed J C, Kieff E, Young L S. CD40-induced growth inhibition in epithelial cells is mimicked by Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP1: involvement of TRAF3 as a common mediator. Oncogene. 1996;13:2243–2254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falk M H, Trauth B C, Debatin K M, Klas C, Gregory C D, Rickinson A B, Calender A, Lenoir G M, Ellwart J W, Krammer P H, et al. Expression of the APO-1 antigen in Burkitt lymphoma cell lines correlates with a shift towards a lymphoblastoid phenotype. Blood. 1992;79:3300–3306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell P J. Signal transduction from the Epstein-Barr virus LMP-1 transforming protein. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:175–177. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finke J, Rowe M, Kallin B, Ernberg I, Rosen A, Dillner J, Klein G. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 5 (EBNA-5) detect multiple protein species in Burkitt's lymphoma and lymphoblastoid cell lines. J Virol. 1987;61:3870–3878. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3870-3878.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher D E. Apoptosis in cancer therapy: crossing the threshold. Cell. 1994;78:539–542. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Siede W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fries K L, Miller W E, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 blocks p53-mediated apoptosis through the induction of the A20 gene. J Virol. 1996;70:8653–8659. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8653-8659.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giaccia A, Kastan M. The complexity of p53 modulation: emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2973–2983. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gong J G, Costanzo A, Yang H Q, Melino G, Kaelin W G, Jr, Levrero M, Wang J Y. The tyrosine kinase c-Abl regulates p73 in apoptotic response to cisplatin-induced DNA damage. Nature. 1999;399:806–809. doi: 10.1038/21690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregory C D, Dive C, Henderson S, Smith C A, Williams G T, Gordon J, Rickinson A B. Activation of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes protects human B cells from death by apoptosis. Nature. 1991;349:612–614. doi: 10.1038/349612a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han Z, Chatterjee D, He D M, Early J, Pantazis P, Wyche J H, Hendrickson E A. Evidence for a G2 checkpoint in p53-independent apoptosis induction by X irradiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5849–5857. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartwell L H, Kastan M B. Cell cycle control and cancer. Science. 1994;266:1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He J, Whitacre C M, Xue L Y, Berger N A, Oleinick N L. Protease activation and cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: an integral part of apoptosis in response to photodynamic treatment. Cancer Res. 1998;58:940–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson S, Rowe M, Gregory C, Croom-Carter D, Wang F, Longnecker R, Kieff E, Rickinson A. Induction of bcl-2 expression by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 protects infected B cells from programmed cell death. Cell. 1991;65:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90007-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollstein M, Shomer B, Greenblatt M, Soussi T, Hovig E, Montesano R, Harris C C. Somatic point mutations in the p53 gene of human tumors and cell lines: updated compilation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:141–146. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin P, Gu Y, Morgan D O. Role of inhibitory CDC2 phosphorylation in radiation-induced G2 arrest in human cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:963–970. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kieff E. Epstein-Barr Virus and its replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2343–2396. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilger E, Kieser A, Baumann M, Hammerschmidt W. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated B-cell proliferation is dependent upon latent membrane protein 1, which stimulates an activated CD40 receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:1700–1709. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko L J, Prives C. p53: puzzle and paradigm. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1054–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laherty C D, Hu H M, Opipari A W, Wang F, Dixit V M. The Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 gene product induces A20 zinc finger protein expression by activating nuclear factor kappa B. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24157–24160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lalle P, Moyret-Lalle C, Wang Q, Vialle J M, Navarro C, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Magaud J P, Ozturk M. Genomic stability and wild-type p53 function of lymphoblastoid cells with germ-line p53 mutation. Oncogene. 1995;10:2447–2454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenoir G, Bornkamm G. Burkitt's lymphoma, a human model for the multistep development of cancer: proposal for a new scenario. Adv Viral Oncol. 1987;6:173–205. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine A J. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li F, Ambrosini G, Chu E Y, Plescia J, Tognin S, Marchisio P C, Altieri D C. Control of apoptosis and mitotic spindle checkpoint by survivin. Nature. 1998;396:580–584. doi: 10.1038/25141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Z G, Baskaran R, Lea-Chou E T, Wood L D, Chen Y, Karin M, Wang J Y. Three distinct signalling responses by murine fibroblasts to genotoxic stress. Nature. 1996;384:273–276. doi: 10.1038/384273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowe S W, Bodis S, McClatchey A, Remington L, Ruley H E, Fisher D E, Housman D E, Jacks T. p53 status and the efficacy of cancer therapy in vivo. Science. 1994;266:807–810. doi: 10.1126/science.7973635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe S W, Ruley H E, Jacks T, Housman D E. p53-dependent apoptosis modulates the cytotoxicity of anticancer agents. Cell. 1993;74:957–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowe S W, Schmitt E M, Smith S W, Osborne B A, Jacks T. p53 is required for radiation-induced apoptosis in mouse thymocytes. Nature. 1993;362:847–849. doi: 10.1038/362847a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mann K P, Staunton D, Thorley-Lawson D A. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded protein found in plasma membranes of transformed cells. J Virol. 1985;55:710–720. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.3.710-720.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okan I, Wang Y, Chen F, Hu L F, Imreh S, Klein G, Wiman K G. The EBV-encoded LMP1 protein inhibits p53-triggered apoptosis but not growth arrest. Oncogene. 1995;11:1027–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Opipari A W, Jr, Hu H M, Yabkowitz R, Dixit V M. The A20 zinc finger protein protects cells from tumor necrosis factor cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12424–12427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parker, G. A., R. Touitou, and M. J. Allday. Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-3C can induce nuclear division divorced from cytokinesis. Oncogene, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Pokrovskaja K, Okan I, Kashuba E, Lowbeer M, Klein G, Szekely L. Epstein-Barr virus infection and mitogen stimulation of normal B cells induces wild-type p53 without subsequent growth arrest or apoptosis. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:987–995. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhind N, Russell P. Mitotic DNA damage and replication checkpoints in yeast. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80118-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruf I K, Rhyne P W, Yang H, Borza C M, Hutt-Fletcher L M, Cleveland J L, Sample J T. Epstein-Barr virus regulates c-MYC, apoptosis, and tumorigenicity in Burkitt lymphoma. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1651–1660. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sorenson C M, Barry M A, Eastman A. Analysis of events associated with cell cycle arrest at G2 phase and cell death induced by cisplatin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:749–755. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.9.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strasser A, Harris A W, Jacks T, Cory S. DNA damage can induce apoptosis in proliferating lymphoid cells via p53-independent mechanisms inhibitable by Bcl-2. Cell. 1994;79:329–339. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strasser A, Huang D C, Vaux D L. The role of the bcl-2/ced-9 gene family in cancer and general implications of defects in cell death control for tumourigenesis and resistance to chemotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1333:F151–F178. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strasser-Wozak E M, Hartmann B L, Geley S, Sgonc R, Bock G, Santos A J, Hattmannstorfer R, Wolf H, Pavelka M, Kofler R. Irradiation induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in p53-deficient lymphoblastic leukemia cells without affecting Bcl-2 and Bax expression. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:687–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tewari M, Quan L T, O'Rourke K, Desnoyers S, Zeng Z, Beidler D R, Poirier G G, Salvesen G S, Dixit V M. Yama/CPP32 beta, a mammalian homolog of CED-3, is a CrmA-inhibitable protease that cleaves the death substrate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Cell. 1995;81:801–809. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vousden K H. Regulation of the cell cycle by viral oncoproteins. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6:109–116. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1995.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang F, Gregory C, Sample C, Rowe M, Liebowitz D, Murray R, Rickinson A, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein (LMP1) and nuclear proteins 2 and 3C are effectors of phenotypic changes in B lymphocytes: EBNA-2 and LMP1 cooperatively induce CD23. J Virol. 1990;64:2309–2318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2309-2318.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J Y. Cellular responses to DNA damage. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:240–247. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang S, Rowe M, Lundgren E. Expression of the Epstein Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 causes a rapid and transient stimulation of the Bcl-2 homologue Mcl-1 levels in B-cell lines. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4610–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinstein J N, Myers T G, O'Connor P M, Friend S H, Fornace A J, Jr, Kohn K W, Fojo T, Bates S E, Rubinstein L V, Anderson N L, Buolamwini J K, van Osdol W W, Monks A P, Scudiero D A, Sausville E A, Zaharevitz D W, Bunow B, Viswanadhan V N, Johnson G S, Wittes R E, Paull K D. An information-intensive approach to the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Science. 1997;275:343–349. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan Z M, Shioya H, Ishiko T, Sun X, Gu J, Huang Y Y, Lu H, Kharbanda S, Weichselbaum R, Kufe D. p73 is regulated by tyrosine kinase c-Abl in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. Nature. 1999;399:814–817. doi: 10.1038/21704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]