Hypertension, defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥80 mmHg, is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). In the US, approximately 25% of reproductive age women have hypertension.1 Of these, less than half are aware of their diagnosis, and when diagnosed, only 10% have their blood pressure controlled.1 Further, racial differences exist with over half of African-American women 20 years of age and older having hypertension.1 Selecting the appropriate hormonal contraception in women with hypertension is important since several of these contraceptives increase blood pressure and, in those with established hypertension, increase the risk for stroke and myocardial infarction (MI). This clinical insight provides guidance in selecting hormonal contraception given that hypertension is considered a relative contraindication and many contraceptive options exist.

Diagnosis

Identifying the degree of hypertension and associated risk factors is important when recommending hormonal contraception for pregnancy prevention. Proper technique and the accurate measurement of blood pressure (BP) during 2-3 office visits, on multiple occasions at home, or using 24-hour ambulatory monitoring must be obtained. Recent updates to the blood pressure guidelines by the American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) now define normal BP as < 120/80 mmHg; elevated BP as SBP 120-129 mmHg and DBP < 80 mmHg; stage I hypertension as SBP 130-139 mmHg or DBP 80-89 mmHg; and stage II hypertension as BP > 140/90 mmHg.2 Given the updated definition of hypertension and change in BP goals, the number of adults age 20 – 44 years diagnosed with hypertension increased from 10.9 million to 24.7 million.3 The newly defined stage I hypertension is treated with lifestyle modification only rather than with medications.

Evidence

Ethinyl estradiol is the estrogen component of combined hormonal contraceptives (CHC) that increases the risk of CVD in a dose-dependent response. Ethinyl estradiol is a potent synthetic estrogen that has vascular and hepatic effects resulting in increased vascular resistance, pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory effects, and cause dyslipidemia, all of which have a role in the pathogenesis of CVD.4 Blood pressure is increased by CHC because of the increased hepatic production of angiotensinogen activating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS).4 Nonoral preparations of CHC such as transdermal preparations, vaginal ring, and injections have been less studied in women with hypertension, however the risks are thought to be comparable to those of combined oral contraceptives (COC). COC cause hypertension in up to 2% of women, with an average increase of SBP by 7-8 mmHg with older COC and less differences with newer and lower dose 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol COC.4 Women with established hypertension who use COC are at higher risk of stroke and MI than normotensive non-users, however the absolute risk is relatively low among women of reproductive age.5 Although COC use is associated with increased risk of venous thromboembolism, a history of hypertension with COC use has no effect on this risk.

The progestin component of CHC varies among the different hormonal contraception and within progestin-only contraceptives (POC), which include progestin-only pills (POP), levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD), subdermal implant, and the injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Depending on the progestin component, there are variable effects on the coagulation cascade, but overall they do not have the same thrombotic effect as estrogen. While POC have no effect on blood pressure, there is limited evidence that the injection DMPA increases lipoproteins and in women with hypertension may increase the risk of stroke.6,7 Less is known about the progestin-only IUD and implant.

When progestins are used in COC, only minor differences in CVD risk are seen among the different progestin components. Drospirenone, a novel progestin, is structurally similar to spironolactone and acts as an antagonist of aldosterone receptors with an anti-diuretic effect, which may neutralize the RAAS induction caused by estrogen.4 Drospirenone in COC decreases mean BP in women with mild hypertension, however it has been associated with slight increase risk of venous thromboembolism compared to COC containing other progestins, although this does not influence recommendations.8

Guidelines for Treatment

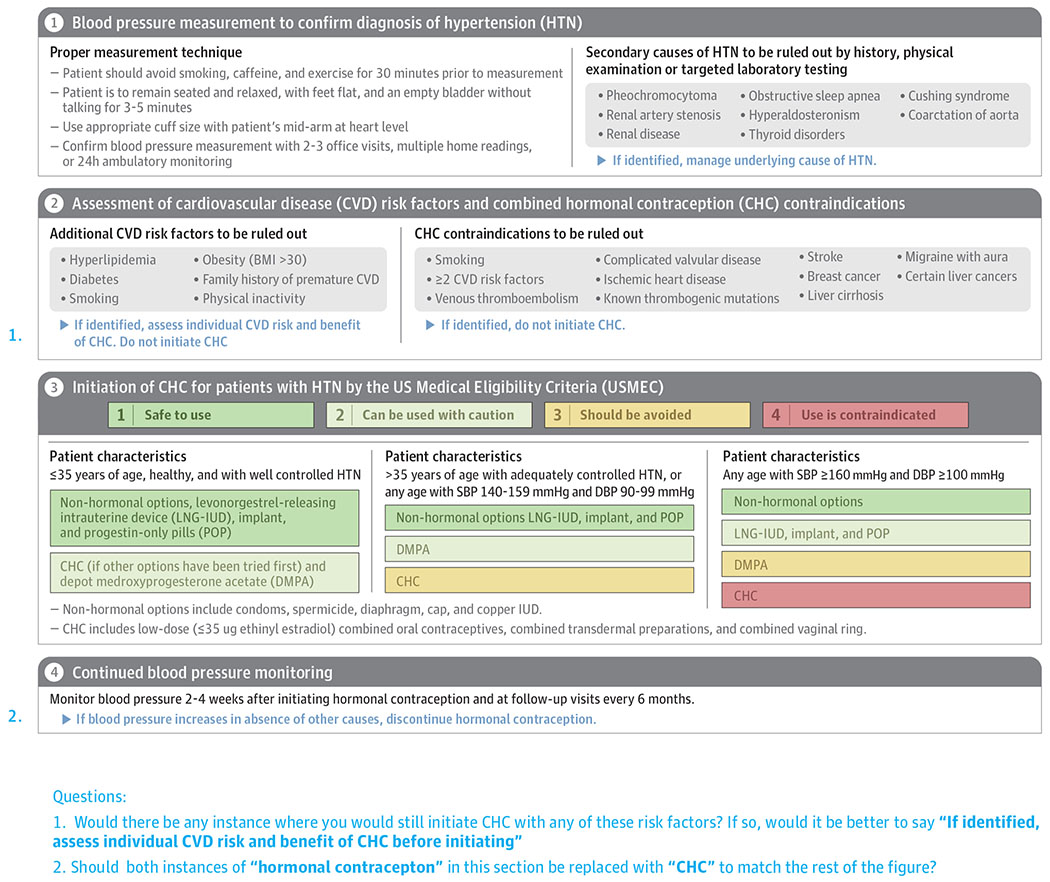

The approach to selecting which hormonal contraception to use in women with hypertension includes: an accurate blood pressure, assessment of risk factors, and consideration of age and degree of hypertension (Figure). The U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria (USMEC) for Contraceptive Use provides the most comprehensive recommendations for women with underlying medical conditions as classified into four categories: 1, no restriction (method can be used); 2, advantages generally outweigh risks; 3, risks usually outweigh the advantages; and 4, unacceptable health risk (method not to be used).7 For CHC, these recommendations do not differentiate between progestin type, includes only ethinyl estradiol doses ≤ 35 μg, and combines transdermal preparations and the vaginal ring. The various POC forms are assessed separately, however the progestin-types are grouped together. For hypertension, recommendations are based on the assumption that no other CVD risk factors exist and on previous blood pressure guidelines, therefore they do not provide recommendations for the updated stage I hypertension.2

Figure.

Approach to Initiating Hormonal Contraception in Women with Hypertension

In 2019, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a Practice Bulletin which included the updated BP guidelines but ACOG continues to endorse USMEC given the need for research in the newly defined stage I hypertension.8 ACOG further provides a consensus opinion with an age cutoff, stating that for healthy women ≤ 35 years old with well-controlled hypertension who do not accept or tolerate POP, a trial of CHC may be allowed.8 For women >35 years of age with adequately controlled BP or women of any age with SBP 140 – 149 mmHg and DBP 90 – 99 mmHg, POC are relatively safe options, with a slight increased risk with DMPA compared to the other POC, and CHC should be avoided. For women with BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg, CHC are contraindicated and POC (other than DMPA) are safer options. Frequent monitoring of BP within 2-4 weeks is important after the initiation of CHC, and CHC should be promptly stopped if BP increases in the absence of other causes. Changes to BP are reversible and may return to pretreatment levels within 3 months of discontinuation.9 Non-hormonal contraception such as condoms, spermicide, diaphragm, and the copper IUD do not affect blood pressure and can be considered in women with any stage of hypertension.

Conclusion

Hypertension is a modifiable risk factor for CVD in women. For women with hypertension, certain hormonal contraception increases the risk of stroke and MI. Choosing the appropriate type of hormonal contraception for women with hypertension is based on age and degree of hypertension. POC are generally safe in women with hypertension, while COC should be prescribed carefully and in women 35 and younger. Research is needed to understand how the updated AHA/ACC Guidelines for BP might change hormonal contraception management given the new definition of stage I hypertension and how different antihypertensives may affect the CVD risk of hormonal contraceptives. In addition, further studies are needed to understand the safety profiles of the nonoral preparations and ultra-low dose (i.e. 10 mcg ethinyl estradiol) hormonal contraception in women with hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute K23HL127262, the Louis B. Mayer Foundation, Edythe L. Broad Women’s Heart Research Fellowship, and the Barbra Streisand Women’s Cardiovascular Research and Education Program, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Virani Salim S, Alonso A, Benjamin Emelia J, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–e596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2199–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muntner P, Carey Robert M, Gidding S, et al. Potential US Population Impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA High Blood Pressure Guideline. Circulation. 2018;137(2):109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shufelt CL, Bairey Merz CN. Contraceptive hormone use and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(3):221–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis KM, Mohllajee AP, Martins SL, Peterson HB. Combined oral contraceptive use among women with hypertension: a systematic review. Contraception. 2006;73(2):179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glisic M, Shahzad S, Tsoli S, et al. Association between progestin-only contraceptive use and cardiometabolic outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(10):1042–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports 2016;65(3):1–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 206: Use of Hormonal Contraception in Women With Coexisting Medical Conditions. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;133(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chasan-Taber L, Willett Walter C, Manson JoAnn E, et al. Prospective Study of Oral Contraceptives and Hypertension Among Women in the United States. Circulation. 1996;94(3):483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]