Abstract

In the small intestine, Na:H (NHE3) and Cl:HCO3 (DRA or PAT1) exchangers present in the brush border membrane (BBM) of absorptive villus cells are primarily responsible for the coupled absorption of NaCl, the malabsorption of which causes diarrhea, a common symptom of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Inducible nitric oxide (iNO), a known mediator of inflammation, is increased in the mucosa of the chronically inflamed IBD intestine. An SAMP1/YitFc (SAMP1) mouse, a spontaneous model of chronic ileitis very similar to human IBD, was used to study alterations in NaCl absorption. The SAMP1 and control AKR mice were treated with I-N(6)-(1-Iminoethyl)-lysine (L-NIL) to inhibit iNO production, and DRA/PAT1 and NHE3 activities and protein expression were studied. Though Na:H exchange activity was unaffected, Cl:HCO3 activity was significantly decreased in SAMP1 mice due to a reduction in its affinity for Cl, which was reversed by L-NIL treatment. Though DRA and PAT1 expressions were unchanged in all experimental conditions, phosphorylation studies indicated that DRA, not PAT1, is affected in SAMP1. Moreover, the altered phosphorylation levels of DRA was restored by L-NIL treatment. Inducible NO mediates the inhibition of coupled NaCl absorption by decreasing Cl:HCO3 but not Na:H exchange. Specifically, Cl:HCO3 exchanger DRA but not PAT1 is regulated at the level of its phosphorylation by iNO in the chronically inflamed intestine.

Keywords: SAMP1/YitFc, inflammatory bowel disease, Na:H exchange, Cl:HCO3 exchange, NHE3, DRA, PAT1, inducible nitric oxide

Introduction

The principal function of the small intestine is to absorb electrolytes, nutrients, and fluid. In the normal mammalian small intestine, the preponderance of existing evidence suggests that villus cells absorb while crypt cells secrete. Villus cells possess Na:H (sodium proton exchanger-3 [NHE3]) and Cl:HCO3 (downregulated in adenoma [DRA] or putative anion transporter-1 [PAT1]) exchange in the brush border membrane (BBM), which facilitates coupled NaCl absorption by these cells.1–3 In contrast, small intestinal crypt cells only have a Cl:HCO3 and Cl channel on the BBM and thus are not capable of coupled NaCl absorption. Although one study has suggested the presence of Cl-dependent Na:H exchange in rat colonic crypt cells, it has not been demonstrated in small intestinal crypt cells in any species to date.4 Thus, the regulation of intestinal NaCl absorption is at the level of Na:H and/or Cl:HCO3 exchange in the villus cells of the small intestine.

The most important sequelae of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) include malabsorption of nutrients and electrolytes resulting in malnutrition, diarrhea, and weight loss.5 Inflammatory bowel disease is the most common chronic diarrheal disease in the United States, afflicting 1.5 million Americans annually. The incidence of Crohn’s disease (CD, 19.2 per 100,000 persons-years) and ulcerative colitis (UC, 20.2 per 100,000 persons-years) has progressively increased in the last 5 decades.6 Inflammatory bowel disease primarily consists of Crohn’s disease, in which chronic transmural inflammation can occur anywhere in the digestive tract, or ulcerative colitis, which is characterized by chronic mucosal inflammation of the colon. Although the specific etiology of IBD remains largely unknown, it involves complex interaction between the genetic factors of the host with environmental or microbial factors leading to abnormal immune responses.7–11 Of these, immune inflammatory mediators such as eicosanoids, including prostaglandins and leukotrienes, neuropeptides, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), in addition to playing an important role in the development of IBD, are also known to alter intestinal absorptive transport processes.12–14

Nitric oxide (NO) is one of the smallest and most biologically active signaling molecules and is an important immune inflammatory mediator that plays a critical role in the onset and progression of intestinal inflammation.15, 16 Inducible NO (iNO), produced by the enzyme iNO synthase (iNOS), produces a variety of deleterious consequences in human IBD, such as causing and worsening of mucosal inflammation and affecting the absorption and secretion of electrolytes, nutrients, and fluid.15–17 Furthermore, it has been shown that the inhibition of iNO production reduces intestinal inflammation and ameliorates tissue damage, thus establishing the role of iNO as an important mediator of inflammation in IBD.18–20

The SAMP1/YitFc mouse strain is a recombinant-inbred mouse that spontaneously develops ileitis and hence does not require any biological or chemical agent to induce inflammation. It is an ideal model for investigating the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation and impaired nutrient and electrolyte absorption because it has many similarities to Crohn’s disease with relevance to the location of the disease, morphological alterations, and response to conventional therapy.21 Therefore, this model of IBD was used in this study to determine how iNO may regulate coupled NaCl absorption in the chronically inflamed intestine. Given this background, the aim of this study was to decipher iNO-mediated functional and molecular mechanisms of regulation of coupled NaCl absorption in the intestinal villus cell of SAMP1/YitFc mice.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Model of Chronic Ileitis

Male SAMP1/YitFc (SAMP1) mice and the control AKR/J (AKR) male mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were kept in 12 hours light/12 hours dark cycle with controlled temperature, humidity, and free access to water and food. After a week of acclimatization, the animals were included in the study at 10 weeks of age. The SAMP1 and AKR mice were treated with l-N(6)-(1-Iminoethyl)-lysine (L-NIL; 0.1 mg/day/kg body weight for 2 days) to inhibit inducible nitric oxide, and the mice were euthanized at the end of the second day of treatment with excess carbon dioxide exposure. All the animal studies described in the study were done according to the ethical regulations and guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Marshall University (IACUC reference number: 743).

Villus Cell Isolation

Intestinal villus cells from AKR and SAMP1 mice were isolated by calcium chelation technique.3 Briefly, the distal small intestine extracted from these mice were filled with cell isolation buffer (0.15 mM EDTA, 112 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 2.4 mM K2HPO4, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.5 mM β-hydroxybutyrate, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol; gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2; pH 7.4) and incubated in 37 °C water bath for 3 minutes, followed by gentle palpitation for another 3 minutes to facilitate cell separation. The isolation buffer with the isolated villus cells was then drained from the intestine and centrifuged at 100 g for 3 minutes. The cell pellet thus obtained was flash frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until experimental use.

Brush Border Membrane Vesicle Preparation and Uptake Experiments

Villus cell brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) were prepared using a previously described method of Mg++ precipitation and differential centrifugation.1 To determine Cl:HCO3 exchange activity, BBMV thus prepared were incubated in either a vesicle medium (VM1) containing 5 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMG) gluconate, 50 mM HEPES-Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KHCO3, and gassed with 5%CO2-95%N2 or a vesicle medium (VM2) containing 5 mM NMG gluconate, 50 mM HEPES-Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM K-gluconate, and gassed with 100% N2. These BBMV were used to perform chloride uptake experiments using rapid-filtration technique as previously described. The uptake reaction was started by adding 5 μL of vesicle in VM1 to 95 μL reaction mixture containing 5 mM NMG 36Cl− (Radioactive Hydrogen Chloride), 15 mM potassium gluconate, and 50 mM MES-Tris (pH 5.5). The vesicle in VM2 was added to the same reaction mixture as described previously but with 1 mM of 4,4-Diisothiocyanatostilbene-2, 2-disulfonic acid disodium salt (DIDS), a potent inhibitor of anion exchangers. The uptake was stopped at 1 minute with the addition of an ice-cold stop solution containing 50 mM HEPES-Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 0.10 mM MgSO4, 50 mM potassium gluconate, and 100 mM NMG gluconate. Each reaction mixture was then filtered on a 0.45μm-Millipore (HAWP) filter, which was then washed with 5 mL of the ice-cold stop solution. The filter was then added to a vial containing 4 mL of Ecoscint A scintillation fluid (National Diagnostics), followed by determination of radioactivity in a Perkin Elmer Tri-Carb LSC 4910TR Scintillation Counter. The uptake numbers were calculated as HCO3 dependent DIDS sensitive 36Cl− uptake to determine Cl:HCO3 exchange activity.

To determine BBMV Na:H exchange activity, BBMV (5 μL) was suspended in a reaction buffer containing 300 mM mannitol, 50 mM Tris-MES (pH 5.5), or 50 mM Tris-HEPES (pH 7.5) and incubated in 95 μL of reaction medium containing 300 mM mannitol, 50 mM Tris-HEPES (pH 7.5), and 1 mM 22NaCl with or without 1 mM amiloride. The uptake was stopped by the addition of an ice-cold stop solution containing 300 mM mannitol and 50 mM Tris-HEPES (pH 7.5). The uptake experiments were performed for 1 minute, followed by the rapid filtration process and radioactivity determination as described previously.

Kinetic Studies: Cl:HCO3 Exchange

Kinetic experiments were performed with intact villus cells isolated from SAMP1 and AKR mice from all experimental conditions. The isolated cells (100 mg) were suspended in buffers containing 5 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMG) gluconate and 50 mM HEPES-Tris (pH 7.5) with 100 mM KHCO3 or 100 mM K-gluconate. The uptake reaction was started by adding the suspended cells to a reaction mixture containing 5 mM NMG 36Cl−, 150 mM potassium gluconate, 50 mM MES-Tris (pH 5.5), and varying concentrations of HCl (0.5 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM, 15 mM, 25 mM, and 50 mM) with or without 1 mM DIDS. The uptake was stopped at 30 seconds with the addition of an ice-cold stop solution containing 50 mM HEPES-Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 0.10 mM MgSO4, 50 mM potassium gluconate, and 100 mM NMG gluconate. Each reaction mixture was then filtered on a 0.65-μm Millipore (DAWP) filter, and the filter was processed as described previously to determine radioactivity. Uptake numbers obtained from these experiments were used for nonlinear regression data analysis in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) to obtain Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters Vmax and Km.

Western Blot Studies

Villus BBM protein extracts prepared from control and L-NIL treated SAMP1 and AKR mice, were separated on a homemade 8% poly acrylamide gel, and transferred to BioTrace PVDF membrane. To determine the immunoreactive protein levels of DRA and PAT1, membranes were probed with mice-reactive anti-DRA (sc-34939, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. USA) and anti-PAT1-specific (sc-26728, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. USA) antibodies. Specific secondary antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase enzyme were used to bind to DRA and PAT1-bound primary antibodies before detecting chemiluminescence with ECL Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). The protein density of the DRA and PAT1-specific protein expressions were quantitated with a densitometric scanner FluorChemTM instrument (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Histology and Immunofluorescence Studies

A small portion of the distal small intestine was fixed in neutral-buffered formalin (10% vol/vol) and embedded in paraffin. Deparaffinized sections of 5-µm thickness were obtained from these fixed tissue using a microtome. These sections were then mounted on glass slides, hydrated with graded ethanol, and were used either for hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E; Electron microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) or for immunofluorescence studies. Light microscope images of H&E-stained sections were captured with a Moticam5 camera. For immunofluorescence studies, sections were hydrated and incubated at 95°C for 10 minutes in 10 mM of sodium citrate buffer (pH 6) for antigen retrieval.22 After washing with PBST (0.05% Tween-20 in phosphate buffered saline), sections were incubated in blocking buffer (2% bovine serum albumin) for 1 hour at room temperature. The sections were then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with antichicken DRA primary antibody (custom antibody services provided by Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), at 1:100 dilution and anti-PAT1 primary antibody (sc:515230, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. USA) at 1:100 dilution. Excess antibody was removed by washing with PBST and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat antichicken (A11039; Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, California) or Alexa Fluor 594 goat antimouse (A11032; Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, California) for DRA and PAT1, respectively, at 1:500 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then washed thrice in PBST, and the nucleus was stained with 4, 9, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in Fluor shield mounting medium (ab104139, Abcam PLC, Cambridge, MA, USA); and images were observed with EVOS FL Cell imaging system and quantified by using Image J software.

Immunoprecipitation and Phosphorylation Studies

Villus cell protein extracts were precleared by the addition of 3 mg of protein A agarose beads for 1 hour at 4°C. For immunoprecipitation, to 100 µg of each of the protein extract, anti-DRA antibody (sc-376187, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. USA) or anti-PAT1 antibody (sc-515230, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. USA) was added and incubated overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with 3 mg of protein A agarose beads at room temperature for 1 hour. The immune adsorbents were then washed 3 times with ice-cold RIPA buffer followed by the addition of 50 μL of sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue) and incubation for 30 minutes at 22°C. The immunoprecipitated protein released in the sample buffer was then resolved by gel electrophoresis and probed with anti-p-serine (ab9332, Abcam PLC, Cambridge, MA, USA) or anti-p-threonine (ab9337, Abcam PLC, Cambridge, MA, USA) or anti-p-tyrosine (ab9319, Abcam PLC, Cambridge, MA, USA) antibodies to detect the phosphorylation levels of the specific amino acids in the immunoprecipitated DRA or PAT1 proteins. The density of the phosphorylation levels of the DRA and PAT1 proteins were quantitated with a densitometric scanner FluorChemTM instrument (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Protein Estimation

For all the experiments conducted in this study, protein levels were determined using Bio-Rad DCTM Protein Assay Reagent (Hercules, CA, USA). Protein levels of whole cell and BBM protein preparations for Western blot and immunoprecipitation studies were determined on a Nanodrop 2000C Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

In this study, all the uptake data are presented as means ± SE. The “n” number in each data set represents a triplicate of uptake experiments, where each triplicate was performed using cells isolated from a different animal. For statistical analysis of each data set, Student t test was performed. The data were considered significant if the P value between 2 experimental groups was <0.05.

Ethical Considerations

All the animal studies described in the article were done in accordance with the procedural and ethical regulations of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Marshall University (IACUC reference number: 743).

Results

Effect of Chronic Enteritis on the Morphology of SAMP1 Mouse Intestine

Histological demonstration of the H&E-stained cross-sections of AKR and SAMP1 mice is shown in Figure 1. AKR mouse ileum was represented by minimal intra-epithelial immunocytes, long villi, and short crypts. The SAMP1 cross-section, however, demonstrated increased intra-epithelial lymphocytes, villus blunting, and crypt hypertrophy, which are characteristic of chronically inflamed intestine as seen in human IBD.

Figure 1.

Ileal cross-sections of the AKR and SAMP1 mice. Hematoxylin and eosin stained (A) AKR and (B) SAMP1 mouse intestine. The SAMP1 mouse intestine shows crypt hypertrophy, villus blunting, and increased intra-epithelial lymphocytes characteristic of IBD.

Effect of Chronic Enteritis and L-NIL Treatment on BBM Cl:HCO3 Exchange

Defined as HCO3-dependent and DIDS-sensitive 36Cl- uptake, Cl:HCO3 exchange activity was present in the BBM of ileal villus cells from both AKR and SAMP1 mice. There was a significant decrease in Cl:HCO3 exchange in SAMP1 mice villus cells compared with AKR mice villus cells (Fig. 2, 266 ± 3.6 pmol/mg protein·min in AKR and 80 ± 10 in SAMP1). To test the hypothesis that iNO may regulate NaCl absorption during chronic ileitis, SAMP1 and AKR mice were treated in vivo with iNO synthase inhibitor L-NIL. Treatment with L-NIL completely reversed the inhibition of Cl:HCO3 exchange in SAMP1 mice and had no effect on the AKR mice (Fig. 2: 216 ± 35 pmol/mg protein·min in SAMP1+L-NIL and 241 ± 22 in AKR+L-NIL).

Figure 2.

Effect of chronic enteritis and L-NIL treatment on Cl:HCO3 exchange in villus cell BBMV. The Cl:HCO3 exchange, defined as HCO3-dependent and DIDS-sensitive uptake of 36Cl-, was significantly decreased during spontaneous ileitis in SAMP1 mice (n = 3, *P < 0.05). This inhibition was reversed back to normal by in vivo L-NIL treatment. L-NIL had no effect on Cl:HCO3 exchange activity in AKR mice (n = 3).

Effect of Chronic Enteritis and L-NIL Treatment on BBM Na:H Exchange

Because coupled classical NaCl absorption in the small intestine is thought to be mediated by the dual operation of Na:H and Cl:HCO3 exchange on the BBM of villus cells, we next looked at Na:H exchange. Defined as pH-dependent and ethylisopropyl amiloride (EIPA)-sensitive uptake of 22Na, Na:H exchange was present in both AKR and SAMP1 mice. But unlike Cl:HCO3 exchange, Na:H exchange remained unaffected in SAMP1 mice compared with the control AKR mice (Fig. 3: 243 ± 13 pmol/mg protein•min in AKR and 257 ± 10 in SAMP1). Further, L-NIL did not have any effect on Na:H exchange in both SAMP1 and AKR (Fig. 3: 234 ± 6 pmol/mg protein·min in SAMP1+L-NIL and 213 ± 8 in AKR+L-NIL).

Figure 3.

Effect of L-NIL treatment on Na:H exchange activity in BBMV. Na:H exchange, defined as pH-dependent and EIPA-sensitive Na uptake, was present comparably in both AKR and SAMP1 mice villus cell BBMV (n = 3). This indicated that Na:H exchange was unaffected by chronic intestinal inflammation in SAMP1 mice. Further, L-NIL had no effect on Na:H exchange in SAMP1 or AKR mice.

Cl:HCO3 Exchange Kinetic Studies

To determine the mechanisms of inhibition of Cl:HCO3 exchange during intestinal inflammation in SAMP1 mice and the effect of L-NIL treatment on Cl:HCO3 exchange, kinetic parameters were determined. Figure 4 shows 36Cl- uptake as a function of increasing concentrations of extracellular Cl at 30 seconds. It was seen that 36Cl- uptake was stimulated as the concentration of extracellular chloride increased, which then became saturated. Table 1 shows the kinetic parameters derived from the kinetic experiments. As seen in Table 1, the affinity (1/Km) of Cl:HCO3 exchange for 36Cl-, was significantly decreased in the villus cells from SAMP1 mice compared with the control, but this decreased affinity was completely restored to normal in the villus cells obtained from L-NIL treated SAMP1 mice.

Figure 4.

Cl:HCO3 exchange kinetic studies. 36Cl- uptake is shown as a function of increasing concentrations of extracellular Cl- at 30 seconds. In all the experimental conditions, as the concentration of extracellular chloride was increased, the uptake of 36Cl- was also stimulated and subsequently became saturated (n = 4). Table 1 shows the kinetic parameters derived from the kinetic experiments. As seen in Table 1, the affinity (1/Km) of Cl:HCO3 exchange for Cl- was significantly decreased in the villus cells from SAMP1 mice compared with the control, but this decreased affinity was completely restored to normal in the villus cells obtained from L-NIL treated SAMP1 mice.

Table 1.

Kinetic Parameters for Cl:HCO3 Exchange

| AKR | SAMP1 | SAMP1+L-NIL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| K m (mM) | 10.45 ± 0.7* | 19.2 ± 0.25# | 10.58 ± 1.3* # |

| V max (nmol/mg protein• 30 seconds) | 1.39 ± 0.08 | 1.61 ± 0.02 | 1.33 ± 0.09 |

Quantitation of Cl:HCO3 Exchangers (DRA or PAT1) Protein by Western Blot Analysis

Western blot experiments were done to determine the effect of iNO inhibition on DRA and PAT1 protein expression. Both DRA and PAT1 have been shown to mediate Cl:HCO3 exchange in different parts of the intestine. Thus, we first quantitated BBM DRA protein levels in villus cells (Fig. 5). Western blot studies showed that BBM DRA protein levels were not affected in SAMP1 mice villus cells nor were they affected by L-NIL treatment in AKR or SAMP1 mice. Densitometry analyses of the western blot data demonstrated that the DRA protein levels were unaltered in all the experimental conditions, indicating that the inhibition of Cl:HCO3 exchange in SAMP1 mice by iNO was not secondary to diminished BBM exchanger numbers but rather altered affinity of the exchanger for Cl-. Western blot studies also showed that BBM PAT1 protein levels were also not affected in SAMP1 mice villus cells, nor were they affected by L-NIL treatment in AKR or SAMP1 mice (Fig. 6). Western blot densitometry analyses demonstrated that the inhibition of Cl:HCO3 exchange activity mediated by PAT1 in SAMP1 mice by iNO was also not due to diminished BBM exchanger numbers but rather due to altered affinity of the exchanger for Cl-.

Figure 5.

Effect of L-NIL on villus cell Cl:HCO3 exchanger DRA protein expression in SAMP1 mouse intestine. Western blot studies revealed that BBM DRA protein level was not affected in SAMP1 mice villus cells nor was it affected by L-NIL treatment in AKR or SAMP1 mice (n = 3), which was further confirmed by the densitometry analyses.

Figure 6.

Effect of L-NIL on villus cell Cl:HCO3 exchanger PAT1 protein expression in SAMP1 mouse intestine. Western blot studies revealed that BBM PAT1 protein level was not affected in SAMP1 mice villus cells nor was it affected by L-NIL treatment in AKR or SAMP1 mice. Western blot densitometry analyses confirmed these findings (n = 3).

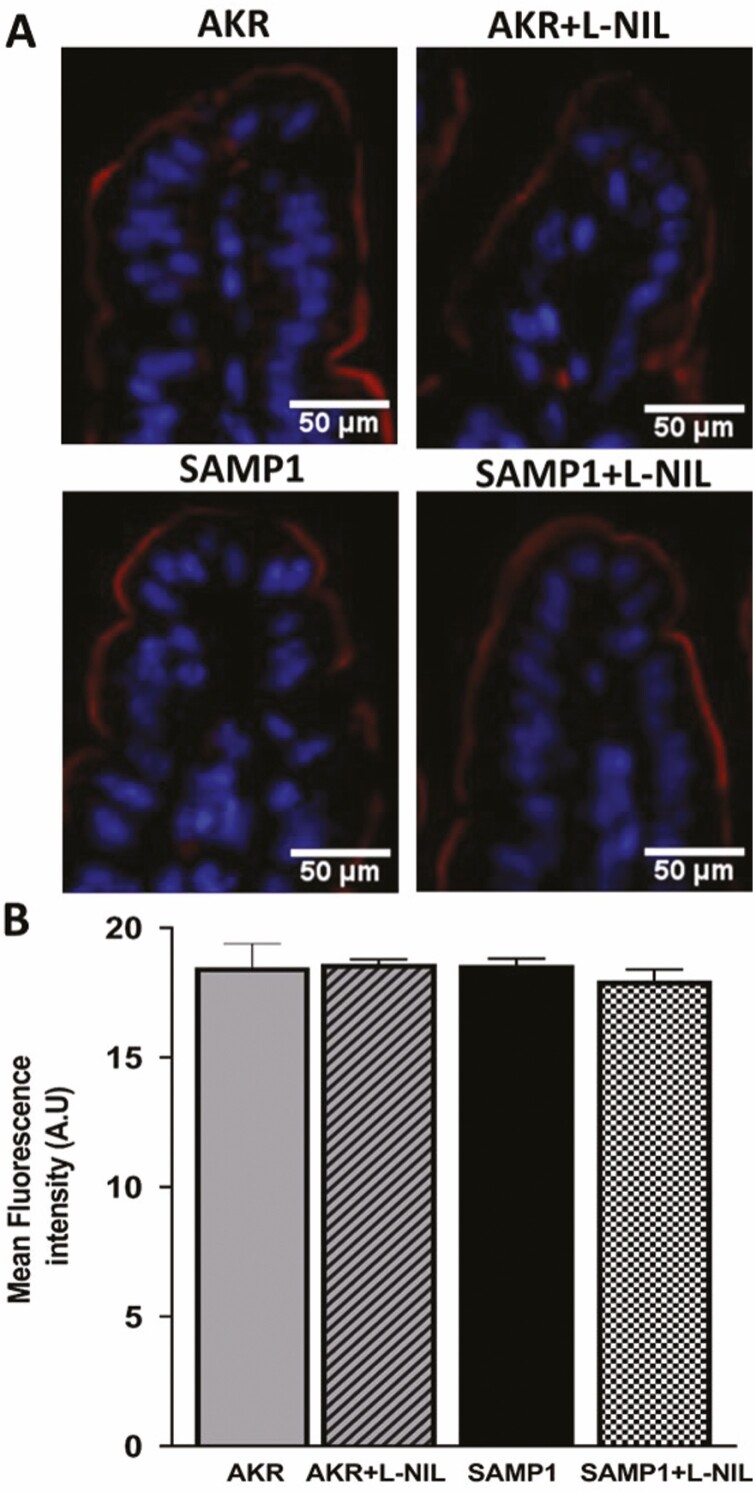

Immunofluorescence Studies of DRA and PAT1 in SAMP1 Mouse Intestine

Immunofluorescence studies were performed to determine the cellular expression of DRA and PAT1 in distal ileal sections. The levels of DRA protein in the BBM of villus cells was similar in AKR and SAMP1 (Fig. 7A) mice, and L-NIL treatment had no effect on DRA in either AKR or SAMP1 (Fig. 7A). The quantitation of DRA fluorescence levels confirmed these findings (Fig. 7B). Further, levels of PAT1 protein in the BBM of villus cells were similar in AKR and SAMP1 (Fig. 8A), and L-NIL treatment had no effect on PAT1 levels in either AKR or SAMP1 (Fig. 8A) mice. The quantitation of PAT1 fluorescence levels confirmed these findings (Fig. 8B). In conjunction with the kinetic studies and western blot studies of the BBM, the immunofluorescence studies clearly demonstrate that the mechanism of inhibition of Cl:HCO3 exchange in the chronically inflamed intestine, mediated by DRA and/or PAT1, is at the level of the affinity of the transporter for Cl-.

Figure 7.

Immunofluorescence studies of DRA in SAMP1 mouse intestine. The levels of DRA protein in the BBM of villus cells was similar in AKR and SAMP1 mice, and L-NIL treatment had no effect on DRA in either AKR or SAMP1 mice. B, Densitometric quantitation of DRA fluorescence levels confirmed these findings (n = 4). Images were captured at 10x magnification.

Figure 8.

Immunofluorescence studies of PAT1 in SAMP1 mouse intestine. Levels of PAT1 protein in the BBM of villus cells was similar in AKR and SAMP1 mice, and L-NIL treatment had no effect on PAT1 levels in either AKR or SAMP1 mice. B, The quantitation of PAT1 fluorescence levels confirmed these findings (n = 4). Images were captured at 10x magnification.

Phosphorylation Studies of DRA and PAT1 in SAMP1 Mouse Intestine

Alterations in affinity are generally secondary to altered glycosylation or phosphorylation of the transporter. Western blot studies showed that the molecular weight of neither DRA nor PAT1 changed in SAMP1 mice villus cells. This indicates that the change in affinity is not secondary to altered glycosylation. Therefore, we looked at the phosphorylation of both DRA and PAT1. As demonstrated in Figure 9A, the phosphorylation of serine residues in DRA is increased in villus cells from SAMP1 mice. This increased phosphorylation is reversed back to normal by in vivo treatment with L-NIL. Further, as shown in Figure 9B, the phosphorylation of threonine residues in DRA is also increased in villus cells from SAMP1 mice. Finally, this increased phosphorylation is also reversed back to normal by in vivo treatment with L-NIL. Of note, the phosphorylation levels of tyrosine residues in the DRA protein remained undetected in all experimental conditions. These results indicate that the altered affinity of Cl:HCO3 exchange in villus cells from the chronically inflamed intestine may be secondary to altered phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues of DRA. Because PAT1 is also known to mediate Cl:HCO3 exchange, its role in the altered affinity of chloride absorption at the protein level was determined. As shown in Figure 10, the phosphorylation of serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues in PAT1 was barely detectable in the control AKR mice and was unaffected in villus cells from SAMP1 mice and in L-NIL-treated animal villus cells. These results indicate that the altered affinity of Cl:HCO3 exchange in villus cells from the chronically inflamed intestine is not secondary to altered phosphorylation of PAT1. Thus, the altered affinity of Cl:HCO3 exchanger in the chronically inflamed intestine mediated by iNO is a result of altered phosphorylation of DRA.

Figure 9.

Phosphorylation studies of DRA in SAMP1 mice intestine. A, Phosphorylation levels of serine residues in DRA was increased in villus cells from SAMP1 mice. This increased phosphorylation was reversed back to normal by in vivo treatment with L-NIL (n = 3, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.01). B, the phosphorylation of threonine residues in DRA was also increased in villus cells from SAMP1 mice. This increased phosphorylation was also reversed back to normal by in vivo treatment with L-NIL (n = 3, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.01).

Figure 10.

Phosphorylation studies of PAT1 in SAMP1 mouse intestine. The phosphorylation levels of serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues in PAT1 were barely detectable in AKR mice and were unaffected in villus cells from SAMP1 mouse. Treatment with L-NIL had no effect on the phosphorylation of PAT1 in AKR or SAMP1 mice villus cells (n = 3).

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated that Cl:HCO3 activity is significantly downregulated in ileal villus cells from SAMP1 mouse model of chronic intestinal inflammation. Moreover, normalization of iNO levels reversed the inhibition of Cl:HCO3 activity to its normal levels. The mechanism of inhibition of Cl:HCO3 by iNO was secondary to a reduction in the affinity of the exchanger for Cl- and not due to altered BBM exchanger numbers. Of the 2 Cl:HCO3 exchangers in the intestine, DRA not PAT1 seems to be regulated by iNO in the chronically inflamed intestine. Further, altered phosphorylation seems to be the specific mechanism by which DRA’s affinity is affected by iNO in chronic enteritis. Finally, Na:H exchange, which along with Cl:HCO3 exchange is known to mediate coupled NaCl absorption, is unaffected in the chronically inflamed intestine. Thus, the traditional coupled NaCl absorptive pathway may not be via the malabsorption of Na and Cl, which is known to result in one of the most common and disabling symptoms of the IBD—diarrhea.

Of the other sodium absorptive pathways present in the villus cells of the small intestine, Na-glucose cotransport is the most prominent one, because glucose is the most abundant dietary nutrient. Na-glucose is predominantly absorbed by the Na-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1; SLC5A1) present in the BBM of the absorptive villus. The Na-glucose co-transporter SGLT1 is perhaps even more potent a transporter for Na because, unlike Na:H exchange which exchanges 1 Na for each H, SGLT1 transports 2 Na for each glucose. The Na-glucose co-transporter SGLT1 is an active secondary transport process for which the necessary Na gradient is provided by Na/K-ATPase present on the basolateral membrane (BLM) of villus cells. Therefore, SGLT1 activity can be regulated at the level of the cotransporter and/or at the level of BLM Na/K-ATPase. The SGLT1 has been demonstrated to be inhibited in a rabbit model of chronic small intestinal inflammation resembling IBD.23 The SGLT1 has also been shown recently to be inhibited in the villus cells from the SAMP1 mouse model of chronic ileitis.24, 25 In both these models of IBD, though the activity of villus cell Na/K-ATPase was decreased, it was not the only reason for the decrease in SGLT1 activity. In fact, SGLT1 activity was decreased at the level of the BBM as a result of a decrease in the number of BBM SGLT1 cotransporters without a change in its affinity for glucose. Recent studies have also demonstrated that in SAMP1 villus cells, iNO inhibits SGLT1 by downregulating SGLT1 cotransporter numbers in the BBM.25 Inducible nitric oxide is also known to mediate its effects by combining with superoxide to form peroxynitrite (OONO), a potent oxidant, which is known to be significantly increased in inflamed mucosa. Peroxynitrite has been shown to inhibit SGLT1 activity in vitro in rat intestinal epithelial cells (IEC-18 cells).19 In this particular study, OONO-mediated inhibition of SGLT1 was also due to a significant decrease in SGLT1 protein expression at the BBM. Given all of these observations, as shown in Figure 11, it is reasonable to hypothesize that although the traditional coupled NaCl absorption via Na:H and Cl:HCO3 exchange may not be responsible for NaCl malabsorption in the IBD intestine, a novel new coupling of SGLT1 with DRA, possibly mediated by iNO, may be the etiology of diarrhea of IBD.

Figure 11.

Novel model of coupled NaCl absorption. In normal mammalian small intestine, traditional coupled NaCl absorption occurs via the dual operation of Na:H and Cl:HCO3 exchange on the BBM of absorptive villus cells. In the chronically inflamed intestine, this traditional NaCl absorption is likely not altered; however, a novel coupling of Cl:HCO3 exchange with Na-glucose cotransport and the inhibition of both seems to mediate the inhibition of the novel coupled NaCl absorption, leading to diarrhea of IBD. Also, malabsorption of chloride in SAMP1 mice is mediated by altered phosphorylation of DRA, likely through intracellular signaling pathway(s) activated by iNO.

Inflammatory bowel disease is known to affect more than 3 million patients in the Western hemisphere, and its incidence has been increasing steadily over the last 5 decades.6 Though the exact etiology of IBD is not known, IBD is known to occur in a genetically susceptible host, and when environmental factors affect the intestinal microbiota, immune response is dysregulated resulting in altered intestinal absorption and secretion. The mucosa of the IBD intestine is characterized by recurring inflammation, which is known to lead to malabsorption of nutrients and electrolytes and secretion of fluid and electrolytes.5, 26–29 These alterations in electrolyte and fluid handling in the IBD intestine results in its most common and disabling symptoms, such as malnutrition, diarrhea, and weight loss. The suggestion here that the inhibition of Cl:HCO3 exchange and Na-glucosecotransport mediated by iNO in the SAMP1 mouse intestine certainly is consistent with electrolyte (NaCl), nutrient (glucose), and fluid malabsorption.

It has been demonstrated through various experimental animal models of IBD and in human IBD that sustained iNO production is highly detrimental,30–34 and the increased expression of iNO in IBD has been shown to be regulated at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels by pro-inflammatory cytokines.30, 35 Moreover, several studies have established a positive correlation between increased mucosal iNO production and increased mucosal and systemic levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ in IBD.36–38 Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown that the pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β stimulate iNO production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from CD and UC patients, suggesting that human PBMCs may possibly be another source of nitric oxide in IBD.36, 39 All these studies suggest that cytokines modulate iNOS expression in the mucosa of IBD, thus playing in a vital role in the progression of inflammation. A variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to be increased in the mucosa of SAMP1 mice as early as 4 weeks of age.21 In the present study, it is not known which specific cytokine may regulate increased iNO production in inflamed mucosa of SAMP1 mice. Future studies will decipher the identity of the specific cytokine that may be involved in the increased production of iNO in SAMP1 mice.

In the present study, in vivo treatment of SAMP1 mice with L-NIL to reduce iNO levels reversed the inhibition of Cl:HCO3 exchange in villus cells. The mechanism of downregulation of Cl:HCO3 was due to diminished affinity of the exchanger for Cl- not altered BBM transporter numbers. This functional mechanism by which Cl:HCO3 was downregulated in the chronically inflamed intestine was restored when iNO levels were reduced to normal levels in the SAMP1 mice. In the control AKR mice, L-NIL had no effect on Cl:HCO3 exchange. The altered affinity of Cl:HCO3 was not due to altered glycosylation status of the protein but rather due to altered phosphorylation levels. These studies provided additional important insights: though phosphorylation of DRA was altered during chronic intestinal inflammation which was reversed by L-NIL treatment, no such changes were seen with PAT1. This indicates that (1) DRA rather than PAT1 is responsible for altered Cl:HCO3 activity in the chronically inflamed intestine and (2) iNO mediates the unique regulation of DRA in the chronically inflamed intestine while having no effect on PAT1. Nitric oxide is known to regulate its target proteins by activating the cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-mediated protein kinase G (PKG) pathway, and this may be the intracellular signaling pathway likely responsible for the altered phosphorylation of DRA in IBD. Indeed, we have previously demonstrated that NO can regulate Na-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 through altered glycosylation mediated by NO-activated PKG pathway.40 We have also demonstrated through in vitro studies that Na-absorptive mechanisms such as NHE3 and SGLT1 may regulate each other through unique molecular mechanisms, either at the level of the transporter gene expression or at the level of the transporter protein, through NO-mediated PKG pathway.41

Conclusion

In conclusion, in the SAMP1 mouse model of IBD, Cl:HCO3 exchange, specifically, DRA, is inhibited by iNO. However, Na:H exchange is unaltered, suggesting that traditional coupled NaCl absorption via these 2 exchangers may not be affected and thus is not the rationale for electrolyte malabsorption resulting in diarrhea of IBD. In contrast, an inhibition of a novel coupled NaCl absorptive pathway mediated by DRA and SGLT1, resulting in an even more potent reduction in NaCl absorption in as much as SGLT1 absorbs twice as much Na as NHE3, may be the cause of diarrhea in the IBD intestine.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to thank Dr. Usha Murughiyan for her editorial assistance in this manuscript preparation.

Supported by: This work was supported by Veteran’s Administration Merit Review grant BX003443-01 and NIH grants DK-67420, DK-108054, and P20GM121299-01A1 to author US.

Author contribution: SA, BP, and SA performed experiments. SA and BP analyzed data and interpreted results of experiments and revised the manuscript. US conceived and designed the study, revised manuscript, and approved final version of manuscript.

References

- 1. Knickelbein R, Aronson PS, Schron CM, et al. Sodium and chloride transport across rabbit ileal brush border. II. Evidence for Cl-HCO3 exchange and mechanism of coupling. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:G236–G245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knickelbein RG, Aronson PS, Dobbins JW. Membrane distribution of sodium-hydrogen and chloride-bicarbonate exchangers in crypt and villus cell membranes from rabbit ileum. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:2158–2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sundaram U, Knickelbein RG, Dobbins JW. pH regulation in ileum: Na(+)-H+ and Cl(-)-HCO3- exchange in isolated crypt and villus cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:G440–G449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Binder HJ, Singh SK, Geibel JP, et al. Novel transport properties of colonic crypt cells: fluid absorption and Cl-dependent Na-H exchange. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol. 1997;118:265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Binder HJ, Ptak T. Jejunal absorption of water and electrolytes in inflammatory bowel disease. J Lab Clin Med. 1970;76:915–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769–2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134:743–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Franzosa EA, Sirota-Madi A, Avila-Pacheco J, et al. Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ananthakrishnan AN, Bernstein CN, Iliopoulos D, et al. Environmental triggers in IBD: a review of progress and evidence. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro, G. Immunological regulation of electrolyte transport. In: Lebenthal E, Duffey M, eds. Textbook of Secretory Diarrhea. New York, NY, USA: Raven Press, 1990, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sartor RB, Powell DW. Mechanisms of diarrhea in intestinal inflammation and hypersensitivity: immune system modulation of intestinal transport. In: Field M, ed. Diarrheal Diseases. New York, NY, USA: Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc.; 1991, 75–114. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simon F, Garcia J, Guyot L, et al. Impact of interleukin-6 on drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in intestinal cells. AAPS J. 2019;22:16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Korhonen R, Lahti A, Kankaanranta H, et al. Nitric oxide production and signaling in inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2005;4:471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kubes P, McCafferty DM. Nitric oxide and intestinal inflammation. Am. J Med. 2000;109:150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kröncke KD, Fehsel K, Kolb-Bachofen V. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in human diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:147–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arthur S, Sundaram U. Inducible nitric oxide regulates intestinal glutamine assimilation during chronic intestinal inflammation. Nitric Oxide: Biol Chem. 2015;44:98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Manoharan P, Sundaram S, Singh S, Sundaram U.. Inducible nitric oxide regulates brush border membrane Na-glucose co-transport, but not Na: H exchange via p38 MAP kinase in intestinal epithelial cells. Cells 2018;7: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCafferty DM, Mudgett JS, Swain MG, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase plays a critical role in resolving intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology 1997;112:1022–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pizarro TT, Pastorelli L, Bamias G, et al. SAMP1/YitFc mouse strain: a spontaneous model of Crohn’s disease-like ileitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:2566–2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Manoharan P, Coon S, Baseler W, et al. Prostaglandins, not the leukotrienes, regulate Cl(-)/HCO(3)(-) exchange (DRA, SLC26A3) in villus cells in the chronically inflamed rabbit ileum. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1828:179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sundaram U, Coon S, Wisel S, et al. Corticosteroids reverse the inhibition of Na-glucose cotransport in the chronically inflamed rabbit ileum. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G211–G218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palaniappan B, Sundaram S, Mani K, et al. Sa1177-unique regulation of sodium-glucose Co-transport by inducible nitric oxide in a spontaneous mouse model of chronic ileitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:S-269. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Palaniappan B, Sundaram S, Arthur S, et al. Inducible nitric oxide regulates na-glucose Co-transport in a spontaneous SAMP1/YitFc mouse model of chronic ileitis. Nutrients. 2020;12. doi: 10.3390/nu12103116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hardee S, Alper A, Pashankar DS, et al. Histopathology of duodenal mucosal lesions in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: statistical analysis to identify distinctive features. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2014;17:450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Conrad MA, Carreon CK, Dawany N, et al. Distinct histopathological features at diagnosis of very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:615–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Archampong EQ, Harris J, Clark CG. The absorption and secretion of water and electrolytes across the healthy and the diseased human colonic mucosa measured in vitro. Gut. 1972;13: 880–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Powell D. Immunophysiology of intestinal electrolyte transport. Compr Physiol 2010, 591–641. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kolios G, Valatas V, Ward SG. Nitric oxide in inflammatory bowel disease: a universal messenger in an unsolved puzzle. Immunology. 2004;113:427–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lundberg JO, Hellström PM, Lundberg JM, et al. Greatly increased luminal nitric oxide in ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1994;344:1673–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boughton-Smith NK, Evans SM, Hawkey CJ, et al. Nitric oxide synthase activity in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Lancet 1993;342:338–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miller MJ, Sadowska-Krowicka H, Chotinaruemol S, et al. Amelioration of chronic ileitis by nitric oxide synthase inhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hogaboam CM, Jacobson K, Collins SM, et al. The selective beneficial effects of nitric oxide inhibition in experimental colitis. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:G673–G684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aktan F. iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production and its regulation. Life Sci. 2004;75:639–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rafa H, Saoula H, Belkhelfa M, et al. IL-23/IL-17A axis correlates with the nitric oxide pathway in inflammatory bowel disease: immunomodulatory effect of retinoic acid. J Interf Cytok Res. 2013;33:355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Obermeier F, Kojouharoff G, Hans W, et al. Interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma)- and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-induced nitric oxide as toxic effector molecule in chronic dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116:238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Soufli I, Toumi R, Rafa H, et al. Overview of cytokines and nitric oxide involvement in immuno-pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther.. 2016;7:353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rafa H, Amri M, Saoula H, et al. Involvement of interferon-γ in bowel disease pathogenesis by nitric oxide pathway: a study in Algerian patients. J Interf Cytok Res. 2010;30:691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arthur S, Coon S, Kekuda R, et al. Regulation of sodium glucose cotransporter SGLT1 through altered glycosylation in the intestinal epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1838: 1208–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Palaniappan B, Sundaram U. Direct and specific inhibition of constitutive nitric oxide synthase uniquely regulates brush border membrane Na-absorptive pathways in intestinal epithelial cells. Nitric oxide: Biol Chem 2018;79:8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]