Abstract

HPPK, which directly precedes DHPS in the folate biosynthetic pathway, is a promising but chronically under-exploited anti-microbial target. Here we report the identification of new S. enterica HPPK inhibitors, offering potential for new resistance circumventing S. enterica therapies as well as avenues for diversifying the current HPPK inhibitor space.

In this study we report the first inhibitors of Salmonella enterica HPPK. The compounds identified are structurally distinct from E.coli and S. aureus HPPK inhibitors, and offer new opportunities for expanding HPPK inhibitor space.

Gram-negative enterobacteria, belonging to the genus Salmonella, are one of the leading causes of food-borne disease globally. The most prevalent and problematic non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) serovars, S. typhimurium and S. enteritidis, belong to the subspecies, S. enterica.1 While most S. enterica infections are self-limiting and remain localised to the gastrointestinal tract, in some instances, systemic invasion of S. enterica leads to bacteraemia, which is a life-threatening condition.2 The fatality rate of S. enterica induced bacteraemia is particularly high in areas of low sociodemographic development, and amongst young children, the elderly, immunocompromised individuals and those infected with malaria.3–5 While the current arsenal of clinically approved antimicrobial agents have proven effective therapies for NTS, the constant emergence of multidrug resistant strains of S. enterica is limiting their efficacy.6–8 Therefore, the identification and validation of new anti-microbials with efficacy against S. enterica is considered to be a high priority.9 The microbial folate biosynthetic pathway is commonly exploited for the development of new antimicrobial agents, particularly through dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) inhibitors often in combination with dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitors.10–12

Hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin pyrophosphokinase (HPPK, Fig. 1) directly precedes DHPS in the folate biosynthetic pathway, and catalyses the transfer of pyrophosphate from ATP to 6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin (HP) in the presence of Mg2+. Inhibiting the function of HPPK therefore represents an alternative means of disrupting folate biosynthesis and is thus considered a promising target for antimicrobial drug discovery.15,16 The fold of apo HPPK forms a large cavity, roughly 26 Å long, 10 Å wide and 10 Å deep, which accommodates sequential binding of both the ATP and HP substrates. When bound with HPPK, the endogenous HP, occupies a narrow binding pocket, located in the catalytic cleft close to the catalytic loops (Fig. 1B). Here it intercalates between Phe54 and Phe124, positioning itself to interact with residues 43–46 on catalytic loop 2, Asn56 and Asp96 on β3 and β1 respectively, as well as a pi-cation interaction with Arg122 on the α3-helix. ATP occupies the remainder of the catalytic cleft, where the nucleoside portion occupies a pocket surrounded by the α-2 helix and β-strands 4 and 6. Here it forms a litany of electrostatic interactions, including multiple interactions with Ile99, Arg111 and Thr113 respectively, and orientates the pyrophosphate region towards HP, interacting with numerous residues including Arg122 and Tyr117. Finally, the Mg2+ ion required for catalysis is coordinated by Asp96 and 98. Substrate binding initiates structural rearrangement, where loops 2 and 3 fold over and seal the catalytic site in its active conformation.17,18 Structural data has suggested that inhibitor binding at the active site, restricts the formation of the active conformation, thus accounting at least partially for their activity.16,19

Fig. 1. A. A cartoon rendering showing an overlay of the modelled SeHPPK (blue) with the YpHPPK (yellow, PDB ID 2QX0). Relevant alpha helixes, beta strands and catalytic loops as previously reported by Li et al. are labelled.13 B. Binding region of HP, ATP and Mg2+ (green spheres) within the catalytic cleft of Yp HPPK, highlighting conserved residues (Phe54, Asp96, Asp98, Ile99, Arg11, Thr113, Arg122, and Phe124) that are known to be critical for ligand binding, as well as catalytic loops 2 and 3. Residue numbering here and throughout manuscript as per that reported for YpHPPK.14.

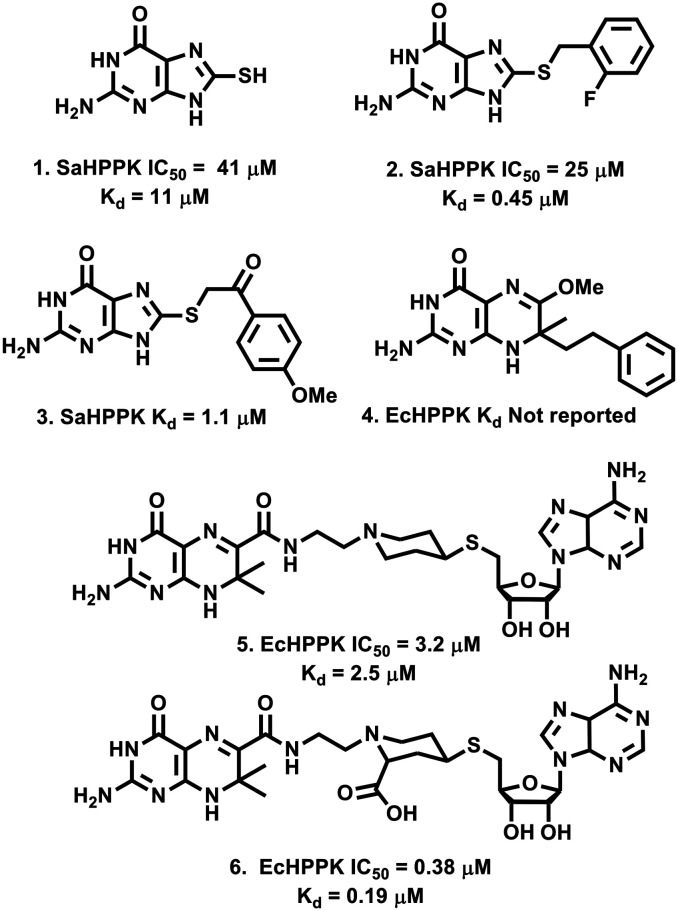

While structural data of HPPK isoforms from numerous microbial pathogens have been reported,14,20–23 to date HPPK drug discovery has primarily focussed on identifying inhibitors of either the Staphylococcus aureus, or Escherichia coli isoforms. Compounds reported to date fall into one of only three categories, namely the mercaptopurine based inhibitors, (e.g.1–3, Fig. 2), substituted pterin analogues (4) or bisubstrate inhibitors (e.g.5 and 6) all of which closely resemble the HPPK endogenous ligands.16,19,24–28

Fig. 2. Structures of some reported Sa and EcHPPK inhibitors.

Considering its promise as an antibacterial target, and the stagnant pipeline of new antimicrobials with activity against Salmonella, we sought to identify inhibitors of S. enterica HPPK (SeHPPK) as potential antimicrobial agents. Given the fairly narrow chemical space explored for the identification of HPPK inhibitors, we were interested in exploring a wider range of chemical scaffolds, which hold promise against this target. To that end, we reasoned that virtual screening could prove fruitful in identifying new scaffolds with HPPK inhibitory potential, whose activity could be validated in vitro. In the absence of any available X-ray crystal structure of SeHPPK, our study required the construction of a suitable HPPK homology model. The SeHPPK sequence was accessed from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, WP_023178310.1, GI: 554677281) reference sequence (RefSeq) database29–31 and a template identification protocol was set to automatically identify matching templates with the HHSearch within the PRotein Interactive MOdeling (PRIMO) pipeline.32

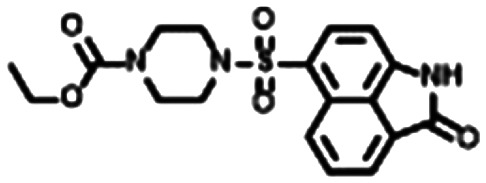

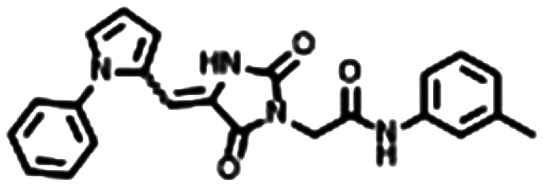

From these criteria, Yersinia pestis HPPK (YpHPPK, PDB ID 2QX0, 1.80 Å),14 which shared 66% sequence identity and 96% sequence coverage with the SeHPPK target sequence was deemed the best template to be used in the calculation of the homology model. We performed a stereochemical and overall structure geometry quality validation of the homology model using Procheck,33,34 ProSA,35 and Verify 3D.36 The subsequent SeHPPK homology model was deemed adequate with a satisfactory Z-dope score of −1.785 and a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.35 Å from the template (Fig. 1). With our model in hand, we proceeded to conduct a virtual screen with AutoDock Vina,37 with our docking search area spanning the entire catalytic site. Using a previously reported docking method and compound filtering criteria,38 a total of 5107 commercially available drug-like compounds, selected from the ZINC15 library39 were screened. In addition, for the purposes of validation, HP was docked against the SeHPPK model, where it was predicted to bind with a similar pose to HP (Fig. S1†). Given that the majority of reported HPPK inhibitors have been identified against E. coli HPPK (EcHPPK), for the purposes of comparison, the docking experiment was also conducted against a corresponding EcHPPK isoform (PDB ID 1Q0N, 1.25 Å). Compounds were ranked according to docking energy, and designated into one of three groups. 1. Lowest energy docking against SeHPPK (group 1); 2. Lowest energy docking against EcHPPK; 3. Lowest cumulative AutoDock binding energies against both isoforms (Table 1). The top three compounds from each cluster (7–15, Table 1), were selected for in vitro biological evaluation. Superficial interrogation of these ligands, showed that all compounds featured a high degree of aromaticity, with fused ring systems being particularly prevalent.

Top three ligands from each group identified from virtual screening.

| Compound no. | Structure | SeHPPK | EcHPPK | SeHPPK docking scoreb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energy (kcal m−1)a | ||||

| Group 1 | ||||

| 7 |

|

−9.4 | −9.1 | −5.03 |

| 8 |

|

−9.4 | −9.6 | −5.55 |

| 9 |

|

−9.4 | −9.1 | −4.95 |

| Group 2 | ||||

| 10 |

|

−8.4 | −9.2 | −6.20 |

| 11 |

|

−9.0 | −10.3 | −4.37 |

| 12 |

|

−7.8 | −9.7 | −4.31 |

| Group 3 | ||||

| 13 |

|

−9.6 | −10.2 | −4.45 |

| 14 |

|

−9.5 | −10.0 | −4.77 |

| 15 |

|

−9.9 | −9.9 | −4.23 |

Binding energy calculated with AutoDock Vina.

Docking score calculated with Schrödinger software suite.

Following the development and optimisation of luminescence based kinase assays for both HPPK isoforms,25,40 all nine compounds were subjected to a single concentration (50 μM) inhibition screen (Fig. 3). In correspondence with the virtual screening data, compounds 7–9 from group 1 were found to be the most active inhibitors of SeHPPK, and appeared to be selective over EcHPPK. Whilst retaining slightly superior SeHPPK inhibitory activity, compounds 10 and 11, from group 2 were found to be the most efficient inhibitors of EcHPPK, while compound 12, which displayed some SeHPPK inhibitory activity was inactive against EcHPPK.

Fig. 3. Luminescence enzymatic activity assay results for inhibition of S. enterica and E. coli HPPK. *The best performing compound (7) was found to have an IC50 of 10.4 μM (±1.14). Assays conducted in technical triplicate.

Interestingly, compounds 13–15 from group 3, were found to be inactive against both HPPK isoforms. As the most active SeHPPK inhibitor identified in the single concentration screen, 7, was selected for dose-dependent assay, against SeHPPK where it was found to possess an IC50 of 10.4 μM (±1.14), which was in line with that previously reported for the mercaptopurine based HPPK inhibitors, and was considered a particularly encouraging result. As the focus of our study was the identification of SeHPPK inhibitors, the encouraging biological activity observed here, warranted a more thorough structural investigation. Accordingly, a more refined docking study was performed on SeHPPK, this time using Glide SP from the Schrödinger software suite41 (docking parameters can be found in the ESI). The SeHPPK homology model was imported to the Maestro interface and the enzymes were typed with the OPLS3e force field parameters.42 For both enzyme models, the binding site was selected to include all amino acids in the catalytic and ATP binding sites, including an additional 20 Å binding radius. Upon docking, multiple output conformations were sampled, followed by a refining geometry minimisation and binding energy calculations using Prime MM-GBSA, whilst applying the USGB solvation model.43 While the variable molecular mechanics parameters used in the separate docking models, meant that the binding energies did not necessarily correlate (Table 1), both docking methods predicted similar biding poses for the respective small molecules at the HPPK catalytic site (e.g. Fig. S2 and S3†). In order to appropriately interrogate our in silico data, we conducted a brief survey of the binding modes of HPPK inhibitors reported in the PDB. Despite resembling ATP, X-ray-co crystal data showed the mercaptopurine containing inhibitors (illustrated here by compound 3, Fig. 4A) bind at the HP region of the catalytic cleft, without disrupting ATP binding. Here the guanine moiety occupies the same aromatic pocket (Phe54, Phe124) as HP, and interacts with residues on both catalytic loops 2 and 3. Importantly, the aromatic thiol extensions interact with the conserved Arg122, which given its dual interaction with HP and ATP is a critical residue for catalytic activity.26

Fig. 4. X-ray co-crystals structures of compound 3 (A, PDB ID 4M5J) and 6 (B, PBD ID 7KDO) bound to EcHPPK, highlighting key electrostatic interactions, at their respective binding sites. Both compounds interact with the key Arg122, while compound 6 forms additional interactions with ATP binding residues His116 and Tyr117.

Similarly, compound 4 was also found to occupy the same region, with its phenyl ethyl arm forming a π-cation interaction with Arg122 (Fig. S4†).28 Unsurprisingly, bisubstrate inhibitors occupy the entire catalytic cleft, which is likely the reason for their generally superior activity. Importantly, X-ray co-crystal data showed, that while compound 5 formed a number of key interactions across the cleft, it did not interact with Arg122, nor did it form any direct interactions with catalytic loop 3 (Fig. S5†). While compound 6 (Fig. 4B) also did not directly interact with loop 3, the carboxylic acid moiety, introduced on the piperidine ring was shown to form a salt bridge with Arg122, in addition to electrostatic interactions with His116 and Tyr117, and was offered as the reason for the vastly improved activity of compound 6.19 The predicted binding mode of 7 to SeHPPK, showed that like HP and the ‘monosubstrate’ inhibitors, it neatly occupied the Phe54, Phe124 pocket, where it formed an important double H-bond to Arg122. From this position, the aromatic amide arm was able to form a series of electrostatic interactions with Leu46, Gln49 and Gln51 located in catalytic loop 2. Interestingly, this predicted binding arrangement precluded interaction with catalytic loop 3 (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the benzoindolone portion of 8, was predicted to nestle itself in the Phe54, Phe124 pocket, where it too formed dual π-cation interactions with Arg122 (Fig. 5B). This portion of the molecule was further anchored in place by a series of electrostatic interactions with Asn56 and the important Mg2+ coordinating Asp96 and Asp98 residues. The ethyl carboxylate portion orientated towards the catalytic loops also forming H-bonds with Leu46 and Gln51. However, in contrast to 7, the ethyl chain also forms a series of H-bonds with the backbone carbonyls of residues 89–91 located in catalytic loop 3. Importantly, the benzoindolone portion of inactive analogue 13, was predicted to bind in a similar orientation to that of 8 (Fig. S6†). However the absence of the ethyl carboxylate region, precludes the formation of electrostatic interactions with catalytic loop 3. Furthermore, interaction of Gln51 with the morpholine oxygen, slightly alters the orientation of the benzoindolone ring, away from Arg122, which may account for its lack of activity. Like 7 and 8, the phenyl portion of 12 is positioned between Phe54 and Phe124, again facilitating H-bond formation with Arg122 as well as halogen bond with Asp96. The 8-nitro quinoline portion again orientates toward the catalytic loops, forming a string of electrostatic interactions with residues in loop 2, while a single electrostatic interaction with the backbone carbonyl of Trp90 in loop 3 is predicted (Fig. S7†).

Fig. 5. Predicted binding modes of the most active SeHPPK inhibitors 7 (A) and 8 (B). Both ligands occupy the same binding region as HP, as well as compounds 3 and 4, where in addition to interactions with residues on loops 3 and/or 2, both interact with key residue Arg122.

Compound 11 is predicted to occupy a similar binding pose to 12, including a double H-bond interaction with Arg122, albeit with fewer electrostatic interactions, with loop2 (Fig. S8†). In contrast, the binding positions of the comparatively more linear ligands 9 and 10 avoided any interaction with the catalytic loops, and instead were predicted to bind bound across β4, β6 and α2 in the vicinity of the ATP binding site. Importantly however, the benzofuran region of 10, orientated toward the Phe54, Phe124 pocket, facilitating the formation of H-bonds with Arg122 and Tyr117. The phenyl region was predicted to form an edge-face π–π interaction with His116, thus orientating the terminal sulphonamide moiety to form a series of H-bonds with Ile99, Arg111 and Thr113 (Fig. S9†). Compound 9 was also predicted to bind in this region of the catalytic site, with the toluene methyl interacting with the Phe54, Phe124 pocket, and the remainder of the molecule forming electrostatic interactions with Asp98, Ile99, Thr113, His116, Tyr117 and Arg122, in a similar fashion to compound 6 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Predicted binding mode of 9, which in addition to occupying the aromatic binding pocket, interacted with several residues required for the binding of ATP and compound 6, including Arg122, His116, Tyr117, Thr113 and Ile99.

Conclusions

In summary, HPPK represents a promising and underexplored target for the development of novel anti-microbial therapies. Through a virtual screen of the ZINC15 library and subsequent in vitro validation, we describe the identification of six promising SeHPPK inhibitors. The most active compound from the single concentration screen, 7, was found to have an IC50 of 10.4 μM, which is in line with previously reported activity of the mercaptopurine HPPK inhibitors. Docking analysis of the six SeHPPK inhibitors showed that four of these compounds (7, 8, 11 and 12) occupy a similar region of the binding cleft, near the catalytic loops, while 9 and 10, were predicted to bind away from the catalytic loops, preferring to occupy the ATP region. Interrogation of these predicted binding poses, in conjunction with X-ray co-crystal data of known HPPK inhibitors, suggested that HPPK inhibitory activity is heavily influenced by interaction with Arg122. Furthermore, inhibitory compounds need not necessarily interact strongly with the catalytic loops but rather an interaction with Arg122, and at least one other region of the catalytic cleft is sufficient to disrupt HPPK activity. In conclusion, the compounds discussed in this communication are the first reported inhibitors of SeHPPK and hold potential for further optimization into S. enterica inhibitors. Furthermore, these compounds also represent new HPPK inhibitory scaffolds, and in conjunction with the structural insight gained here, offer the opportunity to expand the structural diversity of multi pathogen HPPK inhibition beyond the current narrow scope occupied by ATP and HP based ligands, including for the development of new bisubstrate inhibitors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Research Foundation of South Africa (NRF) under the CSUR programme (Grant Number 116305), the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) under a Self-Initiated Research Grant (the views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of the SAMRC) Rhodes University, the University of KwaZulu-Natal flagship initiative and Future Leaders – African Independent Research (FLAIR), a partnership between the African Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society that is funded by the UK Government as part of the Global Challenge Research Fund (GCRF). RM gratefully acknowledge post-doctoral support from the NRF (Grant number 120771). We also thank the Centre for High Performance Computing (CHPC) for access to Schrodinger's modelling suite.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d1md00237f

References

- Kolovskaya O. S. Savitskaya A. G. Zamay T. N. Reshetneva I. T. Zamay G. S. Erkaev E. N. Wang X. Wehbe M. Salmina A. B. Perianova O. V. Zubkova O. A. Spivak E. A. Mezko V. S. Glazyrin Y. E. Titova N. M. Berezovski M. V. Zamay A. S. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:1564–1572. doi: 10.1021/jm301856j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargun A. Sassone-Corsi M. Zheng T. Raffatellu M. Nolan E. M. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021;7:1248–1259. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morpeth S. C. Ramadhani H. O. Crump J. A. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:606–611. doi: 10.1086/603553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. E. Pak G. D. Aaby P. Adu-Sarkodie Y. Ali M. Aseffa A. Biggs H. M. Bjerregaard-Andersen M. Breiman R. F. Crump J. A. Cruz Espinoza L. M. Eltayeb M. A. Gasmelseed N. Hertz J. T. Im J. Jaeger A. Parfait Kabore L. Von Kalckreuth V. Keddy K. H. et al. . Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;62:s23–s31. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanaway J. D. Parisi A. Sarkar K. Blacker B. F. Reiner R. C. Hay S. I. Nixon M. R. Dolecek C. James S. L. Mokdad A. H. Abebe G. Ahmadian E. Alahdab F. Alemnew B. T. T. Alipour V. Allah Bakeshei F. Animut M. D. Ansari F. Arabloo J. et al. . Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019;19:1312–1324. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30418-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Yang B. Wu Y. Zhang Z. Meng X. Xi M. Wang X. Xia X. Shi X. Wang D. Meng J. Food Microbiol. 2015;46:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Brostromer E. Xing D. Jin J. Chong S. Ge H. Wang S. Gu C. Yang L. Gao Y. Q. Su X.-D. Sun Y. Xie X. S. Science. 2013;339:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.1229223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuezobe I. A. Oshun P. O. Odigwe C. C. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;14:CD001167. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001167.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piddock L. J. V. MedChemComm. 2019;10:1227–1230. doi: 10.1039/C9MD90010A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham A. Derrick J. P. BioEssays. 2002;24:637–648. doi: 10.1002/bies.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;1:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne C. R. Antibiotics. 2014;3:1–28. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics3010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. Felczak K. Shi G. Yan H. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12573–12581. doi: 10.1021/bi061057m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczyk J. Li Y. Cherry S. Alexandratos J. Wu Y. Shaw G. Tropea J. E. Waugh D. S. Yan H. Ji X. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2007;63:1169–1177. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907047452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrick J. Iliades P. Simpson J. S. Macreadie I. Open Enzyme Inhib. J. 2008;1:12–33. doi: 10.2174/1874940200801010012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra S. Dolezal O. Collins B. M. Newman J. Simpson J. S. Macreadie I. G. Fernley R. Peat T. S. Swarbrick J. D. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczyk J. Shi G. Yan H. Ji X. Structure. 2000;8:1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing X. Genbin S. Xin C. Honggao Y. Xinhua J. Structure. 1999;7:489–496. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G. Shaw G. X. Zhu F. Tarasov S. G. Ji X. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021;29:115847. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnumsub P. Jaruwat A. Talawanich Y. Noytanom K. Liwnaree B. Poen S. Yuthavong Y. FEBS J. 2020;287:3273–3297. doi: 10.1111/febs.15196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig M. Dale G. E. D'arcy A. Danel F. Fischer S. Gray C. P. Jolidon S. Müller F. Page M. G. Pattison P. Oefner C. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;287:211–219. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemble C. W. Mehta P. K. Mehra S. Li Z. Nourse A. Lee R. E. White S. W. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M. C. Iliades P. Fernley R. T. Berglez J. Pilling P. A. Macreadie I. G. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:655–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun M. K. Hoagland D. Kumar G. Waddell M. B. Rock C. O. Lee R. E. White S. W. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:2157–2165. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M. L. Chhabra S. Wang Z.-C. Debono A. Dolezal O. Newman J. Pitcher N. P. Rahmani R. Cleary B. Barlow N. Hattarki M. Graham B. Peat T. S. Baell J. B. Swarbrick J. D. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:9612–9626. doi: 10.1021/jm501417f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M. L. Pitcher N. P. Lee M. D. DeBono A. J. Wang Z.-C. Harjani J. R. Rahmani R. Cleary B. Peat T. S. Baell J. B. Swarbrick J. D. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:5248–5263. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G. Blaszczyk J. Ji X. Yan H. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:1364–1371. doi: 10.1021/jm0004493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stammers D. K. Achari A. Somers D. O. N. Bryant P. K. Rosemond J. Scott D. L. Champness J. N. FEBS Lett. 1999;456:49–53. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00860-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary N. A. Wright M. W. Brister J. R. Ciufo S. Haddad D. McVeigh R. Rajput B. Robbertse B. Smith-White B. Ako-Adjei D. Astashyn A. Badretdin A. Bao Y. Blinkova O. Brover V. Chetvernin V. Choi J. Cox E. Ermolaeva O. et al. . Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D733–D745. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brister J. R. Ako-Adjei D. Bao Y. Blinkova O. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D571–D577. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova T. Dicuccio M. Badretdin A. Chetvernin V. Nawrocki E. P. Zaslavsky L. Lomsadze A. Pruitt K. D. Borodovsky M. Ostell J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatherley R. Brown D. K. Glenister M. Bishop Ö. T. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A. Rullmann J. A. C. MacArthur M. W. Kaptein R. Thornton J. M. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A. MacArthur M. W. Moss D. S. Thornton J. M. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederstein M. Sippl M. J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:407–410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthy R. Bowei J. Einsenberg D. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:396–404. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O. Olson A. J. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimuda M. P. Laming D. Hoppe H. C. Bishop O. T. Molecules. 2019;24:142. doi: 10.3390/molecules24010142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling T. Irwin J. J. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015;55:2324–2337. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worzella T. Gallagher A. J. Lab. Autom. 2007;12:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jala.2006.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger Release 2020-1, Maestro, LLC, New York, NY, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Roos K. Wu C. Damm W. Reboul M. Stevenson J. M. Lu C. Dahlgren M. K. Mondal S. Chen W. Wang L. Abel R. Friesner R. A. Harder E. D. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019;15:1863–1874. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Abel R. Zhu K. Cao Y. Zhao S. Friesner R. A. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2011;79:2794–2812. doi: 10.1002/prot.23106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.