Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a highly heterogeneous inflammatory musculoskeletal (MSK) disease. PsA affects a wide range of tissues including the peripheral joints, axial skeleton, and enthesis (region where a tendon, ligament, or joint capsule inserts onto the bone) and is associated with dactylitis (swelling of an entire digit) (1). In addition, the majority of patients have skin psoriasis and some level of nail involvement (2). The impact of the disease on patients’ lives is similarly heterogeneous and affects physical function, work productivity, social participation, emotional wellbeing, and fatigue (3). Measuring this heterogenous disease requires the employment of a variety of outcome measures.

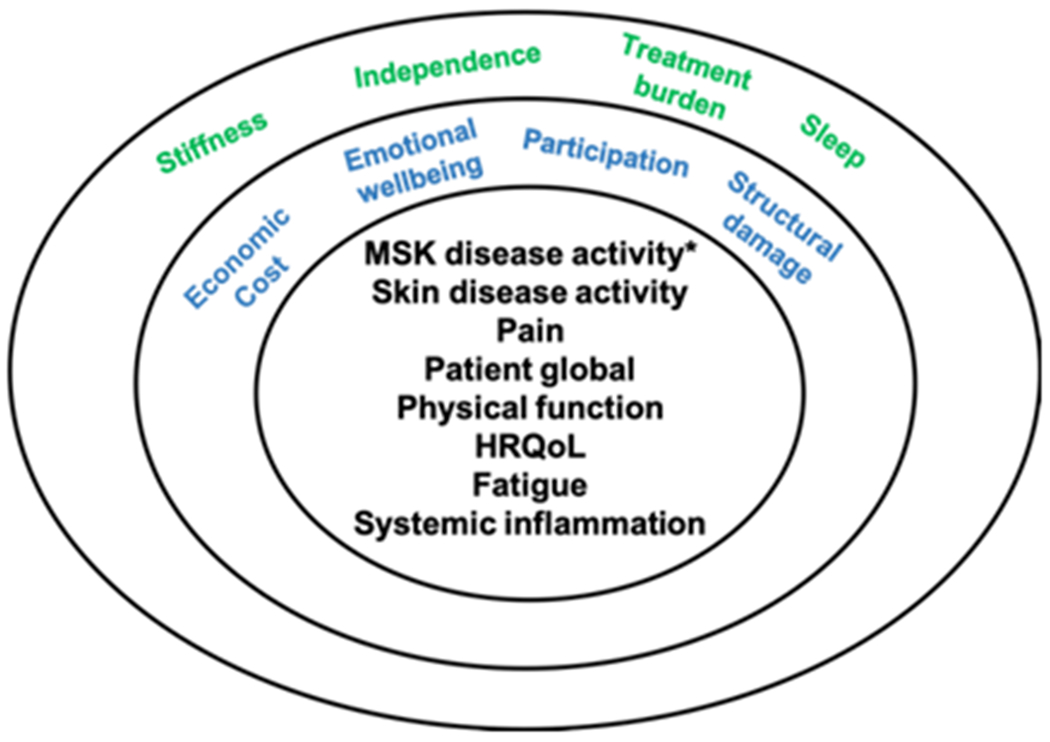

Deciding on what to measure is challenging in a complex disease such as PsA. The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and PsA (GRAPPA)-Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) working group developed a Core Domain Set (Figure 1) to specify which key domains should be measured in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and longitudinal observational studies (LOS) for PsA (3). Among the domains included in the core outcome set, MSK disease activity is considered one of the most important for both patients and clinicians (3). The MSK disease activity domain includes peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spine symptoms (among those with spinal involvement). Other domains included in the center circle (mandatory domains for PsA RCTs and LOS) include skin disease (encompassing both psoriasis and psoriatic nail disease), patient pain assessment, patient global assessment (PtGA) of disease, physical function, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), fatigue, and systemic inflammation. At some point in the life cycle of trials to test the efficacy of a new drug, the recommendation is to also measure economic cost, emotional wellbeing, participation, and structural damage (i.e., via imaging). Finally, several measures were placed on the research agenda, including stiffness, independence, treatment burden, and sleep (3).

Figure 1. GRAPPA-OMERACT Core Outcome Measure Set for Assessment of PsA in RCTs and LOS.

The core set was revised in 2016 with input from patients, clinicians, and researchers and was endorsed by OMERACT. The MSK disease activity item includes peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spine symptoms.

Abbreviations: GRAPPA: Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis; OMERACT: Outcome Measures in Rheumatology; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; RCTs: randomized controlled trials; LOS: longitudinal observational studies; MSK: musculoskeletal; HRQoL: health-related quality of life.

In this paper, we will review the key measures for assessment of PsA. We will focus primarily on measures with a sufficient body of evidence for the instrument and will use the GRAPPA-OMERACT Core Outcome Set to walk through instruments to measure these domains. Additionally, we will discuss composite measures that combine two or more of these domains. When addressing physical function, several of the patient-reported outcomes are available, including HRQoL, patient pain assessment, fatigue, emotional wellbeing, and participation. Many of these are covered in greater detail in other chapters, but we will discuss the instruments in the context of their use in PsA. Additionally, measurement of axial disease is covered in greater detail in chapter 3. Due to space considerations, we have decided not to review the psychometric properties of imaging modalities in PsA (4, 5). Finally, it is important to recognize that there are no gold standards for disease activity in PsA. Thus, in discussing construct validity, we generally use the concept of convergent validity (a component of construct validity) where a measure should be correlated with other measures of the same or similar constructs.

Peripheral Joint Assessments

Inflammatory arthritis is one of the key features of PsA. As in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the joints are assessed using a swollen and tender joint count. However, unlike RA, different joints may be involved (i.e., feet and distal interphalangeal joints are more commonly involved), and there is more often an asymmetric pattern in PsA compared to the characteristically symmetric pattern in RA. At OMERACT 2018, the psychometric properties of the joint counts were reviewed in detail (6). While the 28-joint count is commonly used in clinical practice (and the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) remains a key measure for the European Medicines Association) and the 76/78-swollen and tender joint counts (SJC76/TJC78) have been used in clinical trials, the 66/68-swollen and tender joint counts (SJC66/TJC68) were endorsed as the joint counts to be used in the assessment of PsA in RCTs and LOS. We differentiate the key joints involved in Table 1. In this review, we will focus on the psychometric properties of the SJC66/TJC68. Psychometric properties of the 28-joint count can be reviewed in the Mease et al. 2011 (6, 7). Overall, the critical difference among the joint counts is the joints involved (and the lack of content validity for 28-joint count) and the poor performance of the 28-joint count in patients with oligoarticular disease (making up approximately half of patients with PsA) (8). While the responsiveness is similar between the joint counts, if we are aiming for remission or low disease activity, we cannot use the lower joint count, particularly among patients with polyarticular disease (9).

Table 1.

Comparison of Joint Counts Commonly Used in PsA

| 66/68 | 76/78 | 28 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMJ(s) | X | X | |

| SC(s) | X | X | |

| AC(s) | X | X | |

| Glenohumeral(s) | X | X | X |

| Elbow(s) | X | X | X |

| Wrist(s) | X | X | X |

| CMC(s) | X | ||

| MCP(s) | X | X | X |

| Finger PIP(s) | X | X | X |

| DIP(s) | X | X | |

| Hip(s)* | X | X | |

| Knee(s) | X | X | X |

| Ankle(s) | X | X | |

| Mid-foot (feet) | X | X | |

| MTP(s) | X | X | |

| Toe PIP(s) | X | X | |

| Toe DIP(s) | X |

Number of items: While 68 joints are examined, swelling of the hip cannot be assessed, so only 66 may be considered swollen.

Response options/Scale: The scale is a simple sum of the number of tender joints (0-68) and swollen joints (0-66).

Recall period for items: At the time of the assessment (current).

Abbreviations: PsA: psoriatic arthritis; TMJ: temporomandibular joint; SC: sternoclavicular; AC: acromioclavicular; CMC: carpometacarpal; MCP: metacarpophalangeal; PIP: proximal interphalangeal; DIP: distal interphalangeal; MTP: metatarsophalangeal.

Description

Purpose: The goal of the peripheral joint count is to quantify the burden of synovitis and/or joint inflammation through palpation of the joints. While the swollen joint count is most consistent with our concept of synovitis, tenderness of the joints may likewise indicate inflammation.

Content: Pressure is applied by the assessor using approximately 4 kg/cm2 of pressure (sufficient to blanch the tip of the assessor’s fingernail) (7). Joints assessed are shown in Table 1. The joint and enthesis are near each other anatomically. Thus, training is required for assessing joint counts, particularly prior to clinical studies.

Practical application

Method of administration: The joint counts are performed as a part of the physical examination and may be captured on a simple scoring sheet (paper or electronic).

Scoring: Each joint is scored as tender or not tender and swollen or not swollen (binary). Each set is summed.

Time to complete: The entire exam can be completed with approximately 2 minutes for a trained investigator with the assistance of a recorder. It may take longer if examining and recording (~5 min).

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: Ceiling effects are not generally a problem as patients enrolled in trials have a mean tender joint count of 20 and swollen joint count of 12. The counts are often much lower in clinical practice and longitudinal observational cohort studies. Patients with low joint counts at baseline (i.e., in oligoarticular disease), have little room to improve so there is some evidence of a floor effect (9).

Reliability: The tender joint count has been found to have better interrater reliability than the swollen joint count (10, 11). This may be related to the fact that patients are involved in assessing tenderness (i.e., they report when pain exists in the joints upon pressure), whereas, in joints that are deformed, it can be difficult to detect swelling.

Validity: The SJC66/TJC68 has content validity and construct validity (6). Patients felt that, for the joint count to be a valid assessment of their disease, it must include an assessment of the feet (which are not assessed in the 28-joint count) (6).

Responsiveness: Across clinical trials, joint counts had moderate responsiveness in patients receiving active treatment (standardized response mean (SRM) range 0.5-0.7) (9). The joint counts are less responsive in patients with oligoarticular disease, however.

Minimally clinically important difference: While this was presented at OMERACT 2018, the reported study has not yet been published.

Generalisability: Applicable to all patients with PsA.

Use in clinical trials: The SJC66/TJC68 are key outcome measures in clinical trials and are the hinge of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria (i.e., ACR20) as well as other composite measures of disease activity (12). In order to achieve the outcome of response (based on ACR20, a Boolean criteria), patients must have an improvement of 20% in both the tender joint count and swollen joint count and three of five additional measures.

Critical appraisal:

Despite the concern for lower interrater reliability of the swollen joint count and the lack of responsiveness in patients with lower joint counts at baseline, the SJC66/TJC68 are among the most commonly used measures of disease activity in PsA and are the endorsed measure for peripheral arthritis in PsA (6).

Enthesitis Assessments

Enthesitis is inflammation at the region where a tendon, ligament, or joint capsule inserts onto the bone (13). In PsA, some work has suggested that, in PsA and SpA, enthesitis precedes synovitis. Thus, enthesitis is hypothesized to be an important pathophysiologic aspect of all spondyloarthritis, including PsA. However, identifying the presence of enthesitis is challenging. In clinical practice and clinical trials, we identify enthesitis by the presence of tenderness when palpating the site. However, several studies have demonstrated a relatively low concordance between clinical examination and imaging assessment (and even between types of imaging) (14). Furthermore, there is an increasing recognition that central sensitization is an important contextual factor in assessing enthesitis as patients with central sensitization often have generalized tenderness (15–17). Despite these challenges, clinical enthesitis measures have demonstrated responsiveness in clinical trials.

A number of different clinical enthesitis indices have been developed and many of these have been borrowed from ankylosing spondylitis (AS), most of which have focused on axial sites. Over time, the field has been shifting toward using measures that focus on peripheral sites as peripheral enthesitis is more common than axial sites in PsA (18). Thus, we will not discuss in detail the Mander/Newcastle Enthesitis Index (MEI) or the Maastrict AS Enthesis Score (MASES), both of which have been used in PsA trials, or the San Francisco Index and Berlin Index (Major), which are AS measures that have not been used in PsA RCTs (7). We will focus on the two most commonly used enthesitis measures in PsA today: the Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI) and the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) index. All of these measures are compared in Table 2.

Table 2.

Enthesitis Indices

| SPARCC | MASES | LEI | 4-Point | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Costochondral | X | |||

| 7th Costochondral | X | |||

| Greater Tuberosity of Humerus | X | |||

| Lateral Epicondyle | X | X | ||

| Medial Epicondyle | X | |||

| Posterior-superior Iliac Spine | X | |||

| Anterior-superior Iliac Spine | X | |||

| Iliac Crest | X | |||

| 5th Lumbar Spinous Process | X | |||

| Greater Trochanter | X | |||

| Quadriceps Insertion | X | |||

| Inferior Patella | X | |||

| Tibial Tuberosity | X | |||

| Medial Condyle Femur | X | |||

| Achilles | X | X | X | X |

| Plantar Fascia | X | X |

Abbreviations: SPARCC: Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada; MASES: Maastrict Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesis Score; LEI: Leeds Enthesitis Index.

Adapted from Mease P, Arthritis Care and Research, 2011 with permission.

Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI)

Description

Purpose: The LEI was specifically developed for PsA (unlike the others, which were developed for AS). The final sites were identified based on a stepwise data reduction technique (19).

Content: Similar to the joint count, approximately 4 kg/cm2 of pressure is applied to the areas of interest and the total number of regions in which the patient ascribes to tenderness is counted. See Table 2 for specific sites.

Number of items: 6 enthesial sites in total (3 bilateral sites).

Scale: The scale is 0-6.

Recall period for items: At the time of the assessment (current).

Practical application

Method of administration: Performed as a part of the physical examination and may be captured on a simple scoring sheet (paper or electronic).

Scoring: The score is the sum of sites counted as tender (each site is a binary assessment of tender or not tender).

Time to complete: Takes up to 1 minute to complete.

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: This has not been explicitly described in papers to date. However, one could imagine that it could have both floor and ceiling effects. Approximately 50% or more patients enrolled in PsA RCTs do not have active enthesitis at enrolment. Many clinical trials have examined enthesitis resolution among those with enthesitis at baseline as an alternative to change in the LEI score.

Reliability: Interrater reliability for the LEI is overall quite good (ICC 0.81-0.82) (20, 21).

Validity: There is limited data on content validity. Construct validity is difficult to establish given a lack of a reference standard. However, there is good correlation among the clinical enthesitis indices (19).

Responsiveness: Among patients receiving active treatment, enthesitis measures improve (19). SRMs have not been calculated for LEI.

Minimally clinically important difference: Has not been established.

Generalisability: Applicable to all patients with PsA.

Use in clinical trials: LEI has been used in several trials now and has demonstrated responsiveness and clinical trial discrimination (22). Notably, however, use of this score has not always resulted in significant differences between treatment and placebo (23, 24).

Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Index

Description

Purpose: The SPARCC was developed for patients with SpA, and most of the patients in the development study had axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA) (25). In developing this index, the most frequent sites of power Doppler ultrasound (US) were selected.

Content: Approximately 4 kg/cm2 of pressure is applied to the areas of interest, and the total number of regions in which the patient ascribes to tenderness are counted. See Table 2 for specific sites.

Number of items: 18 enthesial sites in total (9 bilateral sites); note that the distal patella and tibial tuberosity are counted as one if either or both are tender, leading to a score of 0-16.

Scale: The scale is 0-16.

Recall period for items: At the time of the assessment (current).

Practical application

Method of administration: Performed as a part of the physical examination and may be captured on a simple scoring sheet (paper or electronic).

Scoring: The score is the sum of sites counted as tender (each site is a binary assessment of tender or not tender).

Time to complete: Takes 2-3 minute to complete.

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: As with LEI, this has not been explicitly described in papers to date.

Reliability: Interrater reliability for the SPARCC is good (intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) 0.67 in one study and ICC 0.81 in another).

Validity: There is limited data on content validity. Construct validity is difficult to establish given a lack of a reference standard. However, there is good correlation among the clinical enthesitis indices (19).

Responsiveness: Among patients receiving active treatment, enthesitis measures improve (19) and have differentiated between active therapies (26). SRMs have not been calculated for SPARCC.

Minimally clinically important difference: Has not been established.

Generalisability: Applicable to all patients with PsA.

Use in clinical trials: SPARCC has now been used in several trials and has demonstrated clinical trial discrimination. In fact, in three trials, SPARCC was able to differentiate between treatment groups when LEI was not able to do so (26–28). This difference was likely related to the small number of sites involved at baseline when using the LEI and the lack of room to improve. In one of these trials, the first trial in PsA to specifically focus on enthesitis, resolution of enthesitis by SPARCC was the primary outcome (28).

Critical appraisal:

Both SPARCC and LEI are equally used in RCT and LOS and both are equally accepted for measurement of clinical enthesitis at this time.

Dactylitis Assessments

Dactylitis (also known as a “sausage digit”) is characterized by swelling of an entire finger or toe from the base to the tip. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or US, dactylitis is characterized by synovitis, tenosynovitis, enthesitis, and soft tissue swelling. Dactylitis is a key feature of PsA and spondyloarthritis, more broadly. Dactylitis has been assessed in a variety of ways in clinical trials (29). The most commonly used measures in PsA RCTs include dactylitis count, dactylitis severity score (DSS), and the Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI). Historically, mean change in these measures was reported, and more recently, complete resolution has also been reported. The purpose of all of these instruments is to quantitatively measure dactylitis.

Total dactylitis count (0-20) has also been used in several studies.(11) Some studies have defined this count as the total tender digits with dactylitis (10) with some of the total digits presumed to have dactylitis regardless of tenderness (i.e., Clegg Index) (30). Dactylitis count has not been well studied as an outcome measure.

Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI)

Description

Content: The LDI utilizes a tool known as a dactylometer to measure the circumference and tenderness of all digits (31).

Number of items: 20 digits are examined for size and tenderness.

Response options/Scale: This is a continuous measure that does not have a standard scoring range as it depends on the baseline size of the patient’s digits.

Recall period for items: At the time of the assessment (current).

Cost to use: Each dactylometer costs 30 GBP, plus 8 GBP for international shipping (at the time of writing this paper in January 2020).

How to obtain: The tool can be obtained from www.mie-uk.com.

Practical application

Method of administration: The assessor marks which digits are affected and then measures those affected and the contralateral digit around the proximal phalanx as close as possible to the web space. The affected digits are palpated at the level of the proximal phalanx with moderate pressure and the response is categorized as follows: 0=no tenderness, 1=tender, 2=tender and winces, and 3=tender and withdraws.

Scoring: The ratio of the circumference between each affected digit and the contralateral digit is calculated for each affected digit. (If both are involved, the comparison measurement is taken from a table provided) (31). This is combined with the tenderness score for each affected digit and then a sum of each affected digit is calculated. Only digits with a circumference ratio of >10% are counted as dactylitis. A higher score is associated with worse dactylitis.

Administrative burden: This measure takes up to 10 min to complete.

Adaptations: A modification, known as the LDI basic, replaces the 0-3 scale with a binary presence/absence of tenderness.

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: Because this is based on measurements and proportion difference from the contralateral side, there are not floor and ceiling effects.

Reliability: Interobserver and intraobserver reliability (ICCs 0.7-0.9 and 0.84, respectively) are relatively high.

Validity: The LDI is strongly correlated with other measures of dactylitis and moderately correlated with swollen joint count, suggesting good construct validity (30).

Responsiveness: This measure improves over time with treatment (30). SRM has not been calculated.

Minimally clinically important difference: Not established.

Use in clinical trials: Has been used in PsA trials, successfully differentiating between treatment and placebo groups.

Critical appraisal:

While this method is more quantitatively rigorous than other methods, it also takes longer to complete. Additionally, when both digits are involved, the table values are provided for men and women but do not take into account body mass index or any other factors.

Dactylitis Severity Score (DSS)

The DSS gives each digit a score of 0 to 3 (no dactylitis, mild, moderate, and severe) and sums the score for each digit for a final score ranging from 0-60 (32). This score was originally developed and used in the Infliximab Multinational PsA Controlled Trial (IMPACT) in PsA (33) and has since been used in several trials. The DSS is able to discriminate between treatment and placebo. More detailed psychometrics have not been described.

Spine Assessments

Sacroiliitis and/or spondylitis affects approximately 20-40% of patients with PsA (2). This is often referred to as AxPsA or PsA spondylitis (34). There are not yet clear definitions of AxPsA. Currently, axial symptoms of PsA are often measured using similar measures to those in AxSpA (addressed in chapter 3) just as treatment of AxSpA is generally extrapolated from AxSpA. The most commonly used measures of spinal manifestations include the Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI). However, the BASDAI has been found to correlate with overall disease activity in PsA, which suggests that it is not specifically measuring axial disease. In fact, only one question on the BASDAI is specific to axial symptoms (35, 36). Similarly, the Bath AS Function Index (BASFI) is also correlated with other functional measures in PsA, which suggests that it is also not specific for spine symptoms. The Bath AS Metrology Index (BASMI) is occasionally used but has relatively little change over time (see AxSpA chapter 3). Finally, the AS Quality of Life Index (ASQoL) is used within one of the composite measures (Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (CPDAI)) but has not been specifically studied in PsA.

The first trial to address AxPsA was recently presented. In this study, patients with PsA (meeting ClASsification criteria for PsA (CASPAR) criteria) who have clinician-diagnosed axial disease, a BASDAI>4, and a spinal pain (visual analog scale (VAS)) of >40/100 were enrolled. This trial used endpoints similar to those used in AxSpA (Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society Criteria (ASAS) 20). There remains much to be learned about how to optimally measure axial symptoms in PsA. This is an active area of investigation in a collaborative study between GRAPPA and ASAS.

Skin Assessments

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition and is present in the majority of patients with PsA. The most common form of psoriasis is plaque psoriasis (i.e., psoriasis vulgaris). Less common variants include guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular psoriasis. Inverse (or intertriginous) psoriasis occurs in the axilla, between skin folds, and in genital areas. Plaque psoriasis is assessed by the degree of erythema, induration, and scale, as well as the extent/area of disease, which is most often calculated as body surface area (BSA). In calculating BSA, the patient’s palm (full open hand including fingers) is 1% and the total percentage of area involved is quantified as the total percentage (i.e., the number of the patient’s palms of psoriasis). Most patients with PsA have mild psoriasis (BSA <3%), approximately 25% have moderate disease (3-10%), and approximately 12-15% have severe psoriasis (12-15%), similar to the distribution of psoriasis extent in patients with psoriasis but without PsA (37). The average BSA in a rheumatology clinical population is approximately 2%. In order to best assess psoriasis response in PsA trials, some require that patients have at least one measurable target lesion.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)

Description

Purpose: The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) is a quantitative assessment of psoriasis burden. PASI is the primary outcome measure used in psoriasis trials and is frequently a key secondary or co-primary outcome in PsA RCTs.

Content: Includes both the severity (erythema, induration, and scaling) and extent (BSA), weighted by body part.

Number of items: Four assessments for each of four body areas (head, trunk, upper extremities, and lower extremities) is provided. The assessments are erythema, induration, and scale (each assessed as 0-4 using a standardized scale), and the number of palms/percentage of each area is categorized (0 = 0%, 1 = <10%, 2 = 10-29%, 3 = 30-40%, 4 = 50-69%, 5 = 70-89%, and 6 = 90-100%).

Response options/Scale: The scale is 0-72.

Recall period for items: At the time of the assessment (current).

Practical application

Method of administration: The skin is examined (with patient in a gown) and the scores recorded on a scoring sheet (paper or electronic).

Scoring: Each area is assessed separately, the scores for each area are calculated and then each area is weighted based on the surface area of that body part (head = 0.1, upper extremities = 0.2, trunk = 0.3, lower extremities = 0.4). The four areas are then combined into a single score. The formula is shown below:

Where E = erythema, I = induration, S = scaling.

Time to complete: Approximately 5 minutes.

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: There is a floor effect, particularly in PsA studies given the relatively low burden of psoriasis compared to dermatology studies. There is not a ceiling effect; rarely are PASI scores >40.

Reliability: Dermatology trialists trained to calculate PASI scores have high intrarater and interrater reliability (38, 39). The reliability when performed by rheumatologists is lower but this is improved with training (10, 11). GRAPPA has developed training videos for rheumatologists (www.grappanetwork.org). Training significantly improves reliability of these assessments (40).

Validity: PASI scores are moderately correlated with other measures of psoriasis severity including the physician global assessment (PGA) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), a patient-reported outcome (PRO), which suggests that PASI has construct validity (41, 42). Furthermore, in psoriasis trials, greater reductions in PASI are associated with greater improvements in quality of life (43).

Responsiveness: Overall, PASI is responsive, is the reference standard for measuring psoriasis improvement in studies (44), and has excellent responsiveness in psoriasis and PsA clinical trials (45). PASI is not as responsive when PASI is less than 10 at baseline (46). In PsA trials, PASI is generally only applied in patients with a BSA >3%.

Minimally clinically important difference: Not established. The minimally clinically important difference may be challenging for PASI as important differences may depend on baseline scores (i.e., starting at a high PASI, a change of 3 points is likely less notable than a change of 3 when the baseline score is low) (47).

Translations/adaptations: A patient self-administered version of PASI has been developed and is valid and reliable (48).

Use in clinical trials: The most common outcome in psoriasis clinical trials is PASI75, or a 75% improvement in the PASI score. As psoriasis therapies have continued to improve, PASI90 and PASI100 are often reported.

Critical appraisal:

PASI is a reliable and valid instrument for the measurement of psoriasis burden, particularly among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. The responsiveness is limited among patients with mild psoriasis (which comprises a large proportion of patients with PsA). The use of PASI in rheumatology clinical practice is often limited by the time to calculate the score and the need for the patient to remove his or her clothing.

Physician Global Assessment (PGA)

While PASI is the most commonly used measure of psoriasis burden in trials and observational studies, a PGA of psoriasis burden is also often used (49). There are many different versions of the psoriasis PGA. Typically, the PGA rates psoriasis from clear to severe but scales vary and generally range from 0-4, 0-5, and 0-6. Some PGA scores instead combine the scores of the erythema, induration, and scaling of a target lesion, and average the three scores (50). These are much simpler to use and are generally strongly correlated with PASI (49). However, the reliability of BSA and PGA were both lower among rheumatologists than the reliability for PASI.(11)

PGAxBSA

Because PASI can be time consuming, an alternative to PASI, the product of the PGA and BSA, has been developed (51). In this measure, the PGA is assessed on a scale from 0-5 (0=clear, 1=almost clear, 5=severe). PGAxBSA is strongly correlated with PASI (rho = 0.78-0.9), and there is excellent agreement between PASI 50/75/90 and PGAxBSA 50/70/90. The responsiveness is also quite similar (effect size −0.94 vs −1.53 for PGAxBSA and PASI, respectively, at 24 weeks in the Psoriasis Randomized Etanercept STudy in Subjects with PsA Generaisability (PRESTA) and PRISTINE trials) (45). To our knowledge, this has not yet been used as an outcome in a clinical trial. However, this may be a more feasible outcome measure for clinical practice and/or LOS than PASI.

Nail Assessments

Up to 80% of patients with PsA have psoriatic nail disease compared to 50% of patients with psoriasis. (Nail involvement may be more often associated with PsA as the nail bed is the insertion of an enthesis.) These nail changes can be associated with embarrassment and/or pain. Nail changes associated with psoriasis are often the result of inflammation involving either the nail matrix or the nail bed (Table 3). Inflammation in the nail matrix may result in pitting, leukonychia, lunular red spots, and nail plate crumbling. Inflammation in the nail bed may result in onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis, “oil-drops”, salmon spots, or splinter haemorrhages. Current nail indices utilize these features to grade nail involvement. Most nail assessments focus on the fingernails as it is much harder to differentiate between psoriatic nail dystrophy and fungal nail dystrophy in the toenails. The purpose of the nail assessments is to quantify nail disease burden in PsA.

Table 3.

Signs of Nail Inflammation Used in Nail Measures

| Signs of Nail Inflammation Used in Nail Measures | |

|---|---|

| Nail Matrix Inflammation Signs | Nail Bed Inflammation Signs |

|

| |

| Pitting* | Onycholysis* |

| Leukonychia* | Subungual hyperkeratosis* |

| Red spots in the lunula* | Splinter hemorrhages* |

| Nail plate crumbling* | Oil drop dyschromia (also known as salmon patches)* |

| Beau lines | |

| Onychomadesis | |

Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI)

Description

Content: The NAPSI is the most comprehensive nail assessment used in clinical trials. The fingernail is divided into four quadrants. For each quadrant, one point is assigned for a nail matrix abnormality and one point for a nail bed abnormality (as described above), allowing for a total of 8 points per nail.

Number of items: 8 items are scored for each nail.

Response options/Scale: For each quadrant, one point is given for the presence of a nail bed feature and a nail matrix feature.

Recall period for items: At the time of the assessment (current).

Practical application

Method of administration: Each nail is scored, and the scores are recorded on a scoring sheet (paper or electronic).

Scoring: 0-80 (Up to 8 points per fingernail), or if toenails are included, 0-160.

Time to complete: May take 5-10 min to complete depending on the severity of the nail disease and the number of nails involved.

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: Among patients with active nail disease, there should not be significant floor and ceiling effects although this has not been specifically examined.

Reliability: There is good interrater reliability for the NAPSI among trained assessors (ICC 0.78) (52). However, the interrater reliability is higher for the nail bed features compared to the nail matrix features (0.87 vs 0.58) (52). The reliability is much lower among untrained rheumatologists but improves after training (10, 53).

Validity: NAPSI has been found to have a moderate correlation with the Nail Assessment in Psoriasis and PsA (NAPPA), a PRO of nail severity and impact (54). This suggests construct validity. Validity of the NAPSI instrument has not been formally tested.

Responsiveness: The measure is responsive in that the score improves with therapy, but this has not been formally tested (although this could be calculated from a recent trial utilizing NAPSI) (55).

Minimally clinically important difference: Not established.

Use in clinical trials: The NAPSI was the primary outcome used in trials directed at the nails (55, 56). The measure differentiated well between treatment and placebo among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and nail dystrophy (55). An advantage of the measure is the continuous measure. In Elewski et al., the primary outcome was a 75% improvement in the baseline NAPSI score (NAPSI75) at 26 weeks, which also differentiated well between treatment and placebo. Another trial comparing two doses of etanercept used the NAPSI of a single fingernail as the primary outcome and found that the scores (range 0-8) significantly improved with both doses (57).

Adaptations: The modified NAPSI is discussed below. Other modifications include using the NAPSI for one target nail (as in Elewski et al.) or four target nails.

Critical appraisal:

NAPSI is the original nail assessment method and among the most commonly used in trials and nail psoriasis studies. A recent nail consensus guideline proposed the NAPSI as the preferred measure in trials of psoriatic nail dystrophy but could not achieve 90% consensus on this statement. However, in the guideline statement, the group used NAPSI to define mild versus moderate to severe disease for treatment guidelines (where NAPSI<20 is considered mild disease) (58). The panel notes that more data is needed to fully inform this decision and that this may change in the future, particularly as other measures such as the NAPPA and modified NAPSI are better studied.

Modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (mNAPSI)

Description

Content: The modified NAPSI (mNAPSI) is a modification of the NAPSI to make it simpler and easier for clinical practice. This measure is often used in PsA clinical trials (59) and has advanced as a better measure for use in clinical practice (58).

Number of items: Seven items are scored for each fingernail (Table x).

Response options/scale: Nail features are broken into groups. Some are scored from 0-3 and others are scored as present or absent. Specific instructions on how to grade each element are provided in the appendix of the original paper (60). Briefly, first, a score is given for the proportion of the nail affected by onycholysis or oil drop dyschromia (0-3). Second, a score is given for the number of pits (graded as 0-3) and for the proportion of the nail with crumbling (0-3). Third, the following four features are scored as present or absent (1 or 0): leukonychia, splinter haemorrhage, nail bed hyperkeratosis, and red spots in the lunula. Last, the scores are added together.

Recall period for items: At the time of the assessment (current).

Practical application

Method of administration: Performed as a part of the physical examination and may be captured on a simple scoring sheet (paper or electronic).

Scoring: The scores for each fingernail are summed together for a score ranging from 0-130 (0-13 for each nail).

Time to complete: Takes 5 minutes or less to complete.

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: Not examined.

Reliability: Good interrater reliability in the original development study (60) and in a study comparing reliability among rheumatologists and dermatologists.(11)

Validity: mNAPSI is correlated with other measures of nail disease including a patient global nail severity (rho 0.55-0.67), suggesting construct validity (60, 61). It is also strongly correlated with the NAPSI itself, the parent instrument from which it was derived (60).

Responsiveness: Not formally tested. The scores improve with effective therapy.

Minimally clinically important difference: Not established.

Use in clinical trials: The mNAPSI has been used in clinical trials of PsA and differentiated well between therapy and placebo (62).

Critical appraisal:

Overall, this is a shorter instrument to complete compared to NAPSI but needs further validation.

Other Nail Measures

The PGA of nail disease is the most commonly used measure in clinical practice and in LOS (63). This has also been used in clinical trials and was found to improve significantly compared to placebo at 24 weeks (64). In one study, the interrater reliability of the PGA was quite high (ICC 0.92) (61).

Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) in PsA

A recent systematic literature review performed a COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN)-based review of all available PROs in PsA (65). We will reference this review for several available PROs. Additionally, in other chapters within this issue, the psychometric properties of several of the instruments are covered in more detail and will therefore not be covered in detail in this chapter.

Patient Global Assessment (PtGA) of Disease Activity

The purpose of the PtGA of disease activity is to capture the patient’s overall experience of their disease. Some form of a patient global assessment is used in most rheumatic diseases and it is among the most commonly used patient-reported outcome measures in PsA. However, it can be difficult to fully understand what the global assessment score means, especially in a disease with heterogeneous manifestations such as PsA. Furthermore, depending on the way in which the question is framed, the patient’s answer to the question may be different. Additionally, the patient may have difficulty understanding how to answer this question and may ask the coordinator whether or not they should include the joints and the skin as well as the disease impact and the answer back to the patient may vary. Because of this, in 2008, GRAPPA developed a recommended wording for the PtGA, based on a multi-center study involving 319 patients from 10 countries. (66). The recommended ideal is to ask three PtGA questions: 1) “In all the ways in which your PSORIASIS and ARTHRITIS, as a whole, affect you, how would you rate the way you felt over the past week?” (rated Excellent to Poor on a VAS from 0 to 100). 2) “In all the you’re your ARTHRITIS affect you, how would you rate the way you felt over the past week?” (rated Excellent to Poor on a VAS from 0 to 100). 3) “In all the ways your PSORIASIS affects you, how would you rate the way you felt over the past week?” (rated Excellent to Poor on a VAS from 0 to 100).(66). However, recognizing the impracticality of asking all 3 questions in clinical studies or practice, it was recommended to at least ask the first question, encompassing all of the ways that PsA affects the patient. This question is the recommended single question to employ in the calculation of several comprehensive composite measures of PsA, including MDA, VLDA, PASDAS, and CPDAI. The validated question to be employed in the calculation of the arthritis-focused composite measures, the ACR response, DAPSA, cDAPSA, DAS28, and CDAI is the second of these 3 questions, i.e. “in all the ways your ARTHRITIS affects you”.

Description

Content: The PtGA has been worded in numerous ways within clinical trials and observational studies as discussed above.

Number of items: 3.

Response options/scale: 0-100 visual analog scale.

Recall period for items: Varies as well; may be for today but more commonly over the past week.

Cost to use: None.

How to obtain: The wording is provided above and in the original paper (66).

Practical application

Method of administration: Self-administered (paper or electronic).

Scoring: While traditionally a VAS, a numeric rating scale (0-10) has also been used (67, 68).

Respondent time to complete: 1-2 minutes.

Administrative burden: Burden associated with measuring a VAS on paper is minimized by using an electronic version using a sliding ruler.

Translations: In the original study, study coordinators in Italy, Hungary, Germany, Brazil, and Spain assisted with translation and back translation (66).

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: Minimal floor and ceiling effects (66).

Reliability: Test-retest reliability is high (ICC 0.87) (66).

Validity: The PtGA has moderate to strong correlation with other measures of disease from the patient perspective (35, 67, 68).

Responsiveness: The PtGA is responsive with SRMs >0.6 across several trials, was able to detect change in clinical trials, and can detect differences between treatment and placebo (69).

Minimally clinically important difference: Kwok et al. found that the minimally important difference (MID) for the patient global (defined as “overall wellbeing with respect to PsA”) on a scale from 0-100 was −11.3 among patients who reported feeling better or worse than the prior visit (70).

Generalisability: Studies to develop the instrument were performed in an international cohort of patients with PsA, increasing generalisability.

Use in clinical trials: The PtGA is an important piece of several composite measures (discussed below) and one of the criteria in the ACR response criteria (i.e., ACR20). It is thus included in some form in all PsA RCTs and LOS, as well as often within clinical practice.

Critical appraisal

The patient global, in its many forms but most recently in the GRAPPA-endorsed form, is the most commonly used PRO in PsA. Even using the first question of the GRAPPA PtGA as a single item, Lubrano et al. found that this instrument is a reliable measure of low disease activity (LDA) and thus represents a simple tool for use in clinical practice (71). It remains challenging to fully understand what patients incorporate into the meaning of “all the ways in which PsA affects you.” Talli et al. found that the global assessment reflects both the physical and psychological aspects of disease (i.e., anxiety, coping ability, and work and/or leisure activities). It may be the psychological aspects of disease that cause a well described dissociation between the physician and PtGA in approximately 30% of patients with PsA (72, 73).

Patient Pain Assessment

While there are now many ways to assess pain (i.e., pain interference, pain intensity), the most commonly used pain assessments in PsA RCTs and LOS use only one question and most often a VAS (0-100 ranging from no pain to most severe pain) or NRS (0-10). The pain assessment is a part of nearly all of the composite measures (discussed below) and also part of the ACR response criteria. The individual pain assessment items have been relatively understudied in PsA with lacking data on reliability and validity (15, 65). Self-reported pain may be flawed by lack of specificity. For example, if a patient has pain arising from degenerative spine disease, central sensitization pain, or other etiologies, in addition to pain arising from clinical domains specific for PsA, the patient may not be able to discern how to rate PsA-specific pain and may only be able to report on aggregated pain experience. To adjust for the concomitant presence of pain due to central sensitization, the Corrona PsA registry, as well as some recently initiating PsA trials are incorporating a self-report questionnaire that is designed to ascertain the presence and severity of central sensitization/fibromyalgia pain (Mease, Ogdie personal communication).

Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

There are both disease-specific and generic quality of life measures. In PsA, the PsA Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire is a recently developed disease-specific HRQoL measure. The most commonly used generic HRQoL measure (in RCTs) is the Short Form 36 (SF36). The generic measures of HRQoL are covered in another chapter and will not be discussed in detail here.

PsA Impact of Disease (PsAID) Questionnaire

The PsAID is a unique PRO in PsA in that it was created in collaboration with a panel of 13 patients with PsA. The patients devised the content for the items. A series of questions was then developed from the proposed content and tested in 474 patients (74). Several studies have since followed, and the PsAID was the first provisionally endorsed PRO in the PsA core outcome measurement set, matched to HRQoL, by OMERACT in 2018 (75–77) The provisional endorsement was due to the fact that RCTs had not yet incorporated the measure. However, the first trial incorporating the PsAID has now been published, which satisfies this criteria (77).

Description

Content: The PsAID has two versions: a 9-item version for use in clinical trials and a 12-item version for use in clinical practice. The items in the 9-item version include pain, fatigue, skin problems, work and/or leisure activities, functional capacity, discomfort, sleep disturbance, coping, and anxiety. The 12-item version contains the same questions but adds three additional items on embarrassment and/or shame, social participation, and depression. Each item is framed as “Circle the number that best describes the ___ that you felt due to your psoriatic arthritis during the last week” (or similar based on the domain).

Number of items: 12 or 9 depending on the version.

Response options/Scale: 0-12 or 0-9 depending on which scale is used. The response options are on a numerical rating scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 ranging from none or no difficulty to very poorly, extreme, or extreme difficulty.

Recall period for items: Over the past week.

Cost to use: No cost.

How to obtain: As the PsAID was developed by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the questionnaire can be found on the EULAR products and tools website (https://www.eular.org/tools_products_.cfm).

Practical application

Method of administration: Self-administered questionnaire on paper or in an electronic format.

Scoring: For simplicity, the 12-item questionnaire is weighted using whole numbers for easy scoring in clinic. The 9-item questionnaire has more complex weighting. The calculations are given in the original publication (74).

Respondent time to complete: Approximately 3-5 min.

Translations: The PsAID was translated into 12 languages for the original study (English, Estonian, Flemish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Norwegian, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, and Turkish).

Psychometric information:

Floor and ceiling effects: Floor and ceiling effects were low (1% and 0%, respectively) (74).

Reliability: Test-retest reliability was found to be high in two studies (74, 78).

Validity: The PsAID has good content validity as it matches the way patients define disease impact (74, 78). PsAID also has good construct validity in that it is moderately correlated with the PtGA, as well as several other PROs, and strongly correlated with the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID3), another measure of disease impact (35, 79).

Responsiveness: Responsiveness is good overall with SRM 0.74 for PsAID 12 (78) and 0.9 and 0.91 for PsAID9 and PsAID12, respectively, in the original study (74).

Minimally clinically important difference: The preliminary minimally clinically important difference for PsAID9 is −3.6 and −3.0 for PsAID12 (74).

Generalisability: Given the development of this tool by and with patients across twelve countries and many languages, this is considered a generalizable tool.

Use in clinical trials: The PsAID was used as a secondary outcome measure in one clinical trial to date and was able to differentiate well between treatment and placebo (75).

Critical appraisal

Overall the PsAID is an excellent tool with good validity and reliability as well as discriminative ability. A recent study also found that some of the items are valid for use as an individual tool with good responsiveness (78). While there are concerns about the use of the phrase “due to your PsA” in each item and how that changes the meaning of the question, overall this instrument has proven to be useful in monitoring PsA.

Additional measures of quality of life have also been used. Two of the most commonly used have included the PsA Quality of Life Index (PsAQoL) (80). This is a proprietary questionnaire that requires a fee to use, reducing feasibility. However, the measure has good measurement properties overall. Among the generic quality of life measures (discussed in more detail in chapter x), the SF36 is the most commonly used measure in PsA trials and is reported as a physical function component and a mental health component (81). The questionnaire is 36 items and has a cost for use, which reduces feasibility for lower budget studies. The Short Form 12 (SF12) has been substituted for the SF36 in some cases although it is also proprietary (82).

Physical Function

Measurement of physical function is covered in more detail in chapters 21 and 22. Briefly, in PsA, the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)-Disability Index remains the most commonly used measure in PsA RCTs. This questionnaire has been validated in PsA (65, 83). The MCID for the HAQ in PsA has been determined to be 0.35 (7, 83, 84). Additional questionnaires that measure function have also been used in PsA, including the modified HAQ (mHAQ) and the Multidimensional HAQ (MDHAQ), a portion of the RAPID3 questionnaire (35, 85, 86). The HAQ-S, with 6 additional questions related to spinal function, is highly correlated with the HAQ in a general PsA population (87). Its potential utility in PsA patients with axial disease is currently being assessed in the Corrona registry and clinical trials.

Fatigue, Emotional Wellbeing, and Participation

Fatigue, emotional wellbeing, and participation are clearly very important domains in PsA, particularly for patients living with the disease, but also commonly encountered by physicians (3, 88–92). Instruments addressing these three domains are reviewed in chapters 19 (fatigue), 20 (sleep), 23 (participation), 30 (depression) and 31 (anxiety). Several of these instruments, particularly for fatigue and participation, have been studied in PsA including the Fatigue Severity Scale, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Fatigue (FACIT-F), and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI).

Systemic Inflammation

Acute phase reactants, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), are commonly used clinically in managing PsA and are also a key criterion within some composite indices, including the ACR response criteria. Use of acute phase reactants to measure systemic inflammation in PsA was recently reviewed by Elmamoun et al. (93). Overall, as instruments, the data for the psychometric properties of CRP in particular are weak at best, in part due to the need for additional studies.

Physician Global Assessment of PsA (PhGA)

The PhGA is commonly used across diseases. In general, the PhGA takes into account the full clinical picture and incorporates patient feedback (94). This measure attempts to put a number on the clinician’s overall gestalt of how the patient is doing. As with the patient global, there are numerous ways in which this has been phrased. Cauli et al. recommend splitting the PhGA into three separate questions in PsA: one that considers overall disease (MSK and skin), one that considers the MSK disease only, and one considers the skin disease only. When using the VAS scale from 0-100, the Cauli study found high interrater reliability (ICC 0.87, 0.86, and 0.78, respectively). As with the patient global, it is often impractical to ask all three questions, in which case the first question encompassing MSK and skin should be asked. In composite measures which are more comprehensive, this is the PhGA to be employed; for arthritis-specific composite measures, the query focused on arthritis is more appropriate. Additionally, the PhGA has good responsiveness and discrimination in clinical trials and is a key piece of some of the composite measures discussed below, including the ACR20. However, given the discrepancy with the patient global in some circumstances (as discussed above) and the variety of other physician-assessed measures in the Core Domain Set, the PhGA is not included in the 2016 PsA Core Domain Set (3).

Composite Indices in PsA

American College of Rheumatology Response Criteria (ACR20/50/70)

Description

Purpose: A binary response measure developed by rheumatology investigators for rheumatoid arthritis trials and adapted to measure levels of peripheral arthritis improvement in PsA.

Content: A binary outcome reflecting those who achieve a 20%, 50%, or 70% improvement in both joint counts, plus 3 additional measures: physician global, patient global, patient pain, function, and CRP/erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (12).

Number of items: 7 (2 compulsory and 3/5 remaining items).

Scale: Binary outcome.

Recall period for items: PROs usually one-week recall.

Cost to use: Free to use.

How to obtain: Constituent items widely available.

Practical application

Method of administration: ACR responses can be scored using paper or electronic applications. Requires physical examination, patient VAS scales/questionnaires, and laboratory measure (CRP/ESR).

Scoring: Each threshold (20/50/70) requires that percentage improvement from baseline in tender and swollen joint counts and 3 of the remaining 5 measures (plus 3 of the following: physician global, patient global, patient pain, function, and CRP/ESR) (12).

Respondent time to complete: Joint count plus 5-10 minute questionnaires.

Administrative burden: Significant as percentage change must be calculated in 7 items.

Translations: Available in many languages.

Psychometric information

Floor and ceiling effects: Not applicable (binary measure).

Reliability: The components are well validated.

Validity: Face validity for peripheral arthritis but does not reflect wider disease activity.

Responsiveness: Shows response from high baseline disease activity. Responsive to change, differentiates drug and placebo (95, 96), and ACR20 shows maximal differentiation between drug and placebo over EULAR or PsA Response Criteria (PsARC) responses (96).

Minimally clinically important difference: ACR20 considered a minimally clinically important difference.

Generalisability: Validated and tested in polyarticular PsA but does not perform as well in oligoarticular disease. Only valid for those with high baseline disease to show significant improvement. Not helpful in long-term monitoring or those with low levels of disease at baseline.

Use in clinical trials: Most common primary outcome for clinical trials in PsA.

Critical appraisal

The ACR20/50/70 outcomes effectively measure response (improvement) in peripheral PsA and perform well in polyarticular disease (96). They rely on measures at two timepoints and require high baseline disease activity. ACR outcomes are used in most clinical trials and are commonly required by regulators as the primary endpoint in registration studies. Clinical usability is limited as they do not perform well monitoring stable or fluctuating disease over time and require reasonably complex calculations.

Minimal Disease Activity (MDA)

Description

Purpose: A composite disease activity state that reflects “that state of disease activity deemed a useful target of treatment by both the patient and physician, given current treatment possibilities and limitations” (97).

Content: The criteria state that patients are in MDA if they achieve 5 of the 7 criteria: tender joint count ≤1, swollen joint count ≤1, enthesitis count ≤1, PASI ≤1 or BSA ≤3, patient global visual analogue score (VAS) ≤20mm, patient pain VAS ≤15mm, and HAQ ≤0.5 (98).

Number of items: 7 items (4 physician-assessed, 3 PROs).

Scale: Binary outcome.

Recall period for items: PROs usually one-week recall.

Cost to use: Free to use.

How to obtain: Constituent items widely available.

Practical application

Method of administration: MDA can be scored using paper or electronic applications. The GRAPPA app provides an MDA calculator that is free to download. Requires physical examination and patient VAS scales/questionnaires.

Scoring: Binary outcome based on achieving 5 of the 7 cutpoints. If all 7 are met, patient is classified as very LDA (VLDA).

Respondent time to complete: Joint count, enthesitis score, skin score, plus 5-10 minutes questionnaires.

Administrative burden: Low as each item only assessed for one cut point.

Translations: Available in many languages.

Psychometric information

Floor and ceiling effects: Not applicable (binary measure).

Reliability: The components are well validated.

Validity: Face validity for overall PsA disease activity. Reflects key domains of PsA encompassing core outcome set of 2008 (99), correlates well with patient and physician opinion of disease control (100). Low levels of residual active disease among patients in MDA (101–106). Good correlation with other multi-domain measures (101, 102, 107).

Responsiveness: Good responsiveness to change and able to differentiate drug/placebo (101, 102, 108–110) and active comparators (111, 112). Good responsiveness in LOS (113).

Minimally clinically important difference: Binary outcome, so not applicable.

Generalisability: Valid in most subtypes of PsA with validity data in polyarticular and oligoarticular disease. Contains measures of enthesitis and psoriasis to measure other domains.

Use in clinical trials: Commonly used in post-hoc analysis. Recently used as key secondary outcome (Study of Etanercept And Methotrexate (SEAM)-PsA trial) (111). Used as the target of treatment in the Tight Control of PsA (TICOPA) trial confirming the benefit of a treat to target approach in PsA (114).

Critical appraisal

The MDA (and VLDA) criteria are useful measures of good disease control and can be used as a treatment target. They are binary and therefore do not provide any continuous measure of disease activity. They include multiple domains reflecting the variety of PsA phenotypes and are valid in polyarticular and oligoarticular disease. They are useful in clinical practice to guide treatment and are increasingly being used in clinical trials to guide therapeutic strategy and as a key secondary outcome.

Disease Activity in PsA (DAPSA)

Description

Purpose: The Disease Activity in PsA (DAPSA) is a composite measure of peripheral joint disease activity

Content: DAPSA comprises of tender and swollen joint counts (0-66/68), patient arthritis global score and pain score (0-10cm), and a CRP. If the CRP is not included it is called the clinical or cDAPSA. The four/five items are added together without weighting (115).

Number of items: 4 or 5.

Scale: The score ranges from 0 to over 154 in theory.

Recall period for items: PROs usually one-week recall.

Cost to use: Free.

How to obtain: Constituent items widely available.

Practical application

Method of administration: DAPSA can be scored using paper or electronic applications. Requires physical examination, patient VAS scales, and laboratory measure (CRP).

Scoring: Response criteria and cut points for disease states have been proposed. For response, 50, 75, and 85% reductions in DAPSA have been shown to be similar to ACR20/50/70 responses. For defining disease activity, DAPSA scores of ≤4 define remission, 4-14 LDA, 14.1-28 moderate disease activity, and >28 high disease activity. For cDAPSA, the thresholds are slightly lower with the cut-offs between states falling at 4, 13, and 27 (116).

Respondent time to complete: The time taken to score is minimal although the components require a full joint count and two brief patient questions. The inclusion of CRP can also be difficult if results are not available.

Administrative burden: Minimal.

Translations: Global VAS available in many languages.

Psychometric information

Floor and ceiling effects: None demonstrated.

Reliability: The reliability of the DAPSA is good as the components are well validated.

Validity: The measure reflects peripheral disease activity in PsA well with a full joint count as recommended in PsA. However, it does not include measures of other disease domains such as psoriasis and enthesitis. It shows good correlation with other joint measures (114, 117) but not other domains (116, 118). Remission is associated with low residual articular disease, but other domains can remain active (104–106, 119).

Responsiveness: Good responsiveness to change in trials able to differentiate drug and placebo (101, 108, 115, 119), but effect size lower than PsA Disease Activity Score (PASDAS) in most trial post-hoc analysis (101, 119, 120). Lower responsiveness than other composite disease measures in LOS (121). No differentiation seen in two active comparator studies including the recent SEAM-PsA trial (111, 122).

Minimally clinically important difference: Minimally clinically important difference has not been defined, but a reduction of 50% in the score is equivalent to an ACR20 (116).

Generalisability: Developed and tested in predominantly polyarticular peripheral arthritis. May not be sensitive to change in oligoarthritis as scores limited by low joint counts and does not reflect other disease domains.

Use in clinical trials: Tested in post-hoc analysis and some studies as secondary outcome.

Critical appraisal

The DAPSA is a good measure of articular disease in polyarticular PsA and includes a full 68/66 joint count. It is quick and easy to assess particularly if the cDAPSA is used and the assessor does not require a CRP result. It can provide both a measure of current disease activity and response measures. Useful in clinical practice to assess polyarticular peripheral arthritis. Further data required to assess use in trials.

Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (CPDAI)

Description

Purpose: A continuous composite disease activity measure (123) based on the GRAPPA treatment recommendations grid (124).

Content: Five domains (peripheral arthritis, psoriasis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial disease) each assessed using a physical examination measure and a PRO to assess impact.

Number of items: 9 items (tender/swollen joint count, enthesitis count, dactylitis count, PASI, BASDAI, ASQOL, HAQ, DLQI).

Scale: 0-15 in total with each domain scored 0-3 (none, mild, moderate, severe).

Recall period for items: PROs usually one-week recall.

Cost to use: Free.

How to obtain: Constituent items widely available.

Practical application

Method of administration: CPDAI can be scored using paper or electronic applications. Requires physical examination, patient VAS scales, and questionnaires.

Scoring: Domains are each scored 0-3 based on cut-offs derived from the literature. Components are summed to give a total score (0-15) (123). Cut offs proposed for near-remission (<2) and LDA(<3 or 4) (125).

Respondent time to complete: Joint count, enthesitis count, dactylitis count, PASI, plus 10-minute questionnaires.

Administrative burden: Low as each domain has simple cut-offs and score is easily summed.

Translations: Available in many languages.

Psychometric information

Floor and ceiling effects: Floor effects unlikely as this would require no active disease. Ceiling effect potentially seen in severe disease.

Reliability: The components are well validated.

Validity: Development and cut points for each domain score are eminence and not evidence based. Reflects key domains of PsA and uses measures of both disease activity and impact. Good correlation with other multi-domain measures (101, 117, 123, 125, 126) and lower correlation with pure joint measures (117), which is to be expected as it reflects additional domains of disease.

Responsiveness: Good responsiveness to change and differentiates drug/placebo (101, 108, 119) and active comparators (122, 127). Also good responsiveness in LOS (121). Effect size smaller than PASDAS (101, 119, 120) in clinical trial post-hoc analysis. Sensitive to change in skin disease as is well confirmed in post-hoc analysis of the PRESTA dataset (122).

Minimally clinically important difference: Not defined.

Generalisability: Valid in most subtypes of PsA and encompasses all key PsA domains.

Use in clinical trials: Used in multiple post-hoc analyses but lower effect size than other multi-domain composite measures. Able to identify change related to domains other than peripheral arthritis.

Critical appraisal

The CPDAI is a validated multi-domain composite measure that encompasses all key domains of PsA. It is relatively easy to use in trials or clinical practice but takes a little longer to assess than other composites with more questionnaires required. It is responsive to change but usually found to have slightly lower effect size than other multi-domain composite measures. A relatively small scoring range may produce some ceiling effect. Limited use in clinical practice but often calculated in post-hoc trial analysis.

PsA Disease Activity Score (PASDAS)

Description

Purpose: A composite disease activity measure developed using similar methodology to the RA and AS DAS scores.

Content: A weighted score consisting of physician-assessed items (physician global VAS, tender/swollen joint count, enthesitis count, dactylitis count), PROs (patient global VAS and SF36 PCS), and a laboratory variable (CRP).

Number of items: 8.

Scale: Theoretically around 0.4 to 11.

Recall period for items: PROs usually one-week recall.

Cost to use: Free, SF36 available free from the RAND Corporation.

How to obtain: Constituent items widely available.

Practical application

Method of administration: PASDAS can be scored using paper or electronic applications. Requires physical examination, PROs, and a CRP value.

Scoring: Components are summed using a complex weighted formula. PASDAS can be used to calculate validated response criteria: good response is reduction from baseline of ≥1.6 and final score of ≤3.2; moderate response is either of these criteria or reduction of ≥0.8 with a final score of <5.4; poor response is neither (128). Validated cut points for disease activity are available: ≤1.9 is remission, ≤3.2 is LDA, <5.4 is moderate disease activity, and ≥5.4 is high disease activity.

Respondent time to complete: Joint count, enthesitis count, dactylitis count, plus 10-minute questionnaires.

Administrative burden: Complex formula requires electronic calculator or app.

Translations: Available in many languages.

Psychometric information

Floor and ceiling effects: None demonstrated.

Reliability: The components are well validated.

Validity: Face validity for overall PsA disease activity. Choice of components and relative weighting are evidence-based. Reflects key domains of PsA except for skin psoriasis. Good correlation with other multi-domain measures (101, 125, 126).

Responsiveness: Good responsiveness to change in clinical trial datasets differentiating drug/placebo (101, 108, 119) and active comparators (111, 112, 127). Effect size usually highest of the newer composite measures (compared to DAPSA, CPDAI, and GRAPPA Composite Exercise (GRACE)) (101, 119).30 Good responsiveness in LOS (121).

Minimally clinically important difference: Not defined. Moderate response is reduction of ≥1.6.

Generalisability: Valid in most subtypes of PsA including polyarticular and oligoarticular disease. Encompasses most key PsA domains except for skin. Heavily driven by patient and physician global allowing flexibility of score, and post-hoc analysis in SEAM-PsA has shown that different components contribute to the response in different patients appropriately.

Use in clinical trials: Widely used in post-hoc analyses of clinical trials with maximal effect size in all analyses.

Critical appraisal

The PASDAS is an evidence-driven composite measure of disease activity that is validated in multiple datasets and populations. It has a high effect size making it ideal for clinical trials, and it can adapt to different patients with different items driving the response. The only limitation is that it does not include a direct measure of skin disease. It is widely used in trial analysis and may start to become a primary outcome in the future. In clinical practice, the complex formula has limited feasibility, but the use of calculators or databases can make PASDAS practical in routine clinics.

GRAPPA Composite Exercise (GRACE) Score

Description

Purpose: A composite disease activity measure developed using key domains in PsA from the OMERACT core set of 2008 and utilising desirability functions for each measure (129).

Content: A simple sum of domains transformed by desirability functions consisting of physician-assessed items (tender/swollen joint count, PASI) and PROs (patient global/skin/joint VAS, HAQ, and PsAQoL).

Number of items: 8.

Scale: 0-10.

Recall period for items: PROs usually one-week recall.

Cost to use: Free.

How to obtain: Constituent items widely available.

Practical application

Method of administration: GRACE can be scored using paper or electronic applications. Requires physical examination and PROs.

Scoring: Components are transformed according to published desirability functions to give a score of 0 (totally unacceptable) to 1 (normal). They are combined in a simple sum and transformed by subtracting from 1 and multiplying by 10 to give a score of 0-10. GRACE can be used to calculate validated response criteria: good response is reduction from baseline of ≥2 and final score of ≤2.3; moderate response is either of these criteria alone or reduction of baseline of ≥1 and final score of <4.7; poor response is neither (128). Limited cut points for disease activity are data driven but with limited validation: ≤2.3 is LDA, <4.7 moderate disease activity, ≥4.7 high disease activity.

Respondent time to complete: Joint count, PASI, plus 5-minute questionnaires.

Administrative burden: Complex transformation to desirability functions easier using electronic calculator or app.

Translations: Available in many languages.

Psychometric information

Floor and ceiling effects: Not defined

Reliability: The components are well validated.

Validity: Face validity for overall PsA disease activity. Good correlation with other multi-domain measures (101).

Responsiveness: Good responsiveness to change in clinical trial datasets differentiating drug/placebo (101, 119, 120) and active comparators (127). Effect size usually only second to PASDAS when compared with other composite measures (101, 119, 120). Good responsiveness in LOS (121).

Minimally clinically important difference: Not defined.

Generalisability: Limited data available to date but good performance in clinical trial datasets (mostly polyarticular PsA).

Use in clinical trials: Limited post-hoc analyses showing good effect size.

Critical appraisal

The GRACE is the least studied composite index in PsA despite strong development methodology. It encompasses key domains (joints and skin) alongside three patient VAS scores to identify disease activity and impact. More data is needed before this can be recommended for use in interventional trials or observational studies, but initial data are promising.

Conclusions

Over the past ten years, there has been significant progress in our understanding of measurement properties of instruments in PsA. Numerous valid and reliable instruments for the measurement of various aspects of PsA now exist, including composite measures for measurement of overall disease activity (130–132). In this paper, we have summarized the most commonly used instruments and their measurement properties (Table 4 and Table 5). The GRAPPA-OMERACT group is continuing to work to examine measurement properties for these instruments and to identify the best sets of outcome measures for not only traditional RCTs but also pragmatic trials and longitudinal observational studies.

Table 4:

Practical Applications

| Measure | Number of Items | Content/Domains | Method of Administration | Recall Period | Response Format | Range of Scores | Score Interpretation | Availability of Normative Data | Cross-cultural Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Outcome Measures | |||||||||

| SJC66/TJC68 | 66 and 68 sites | MSK disease activity: peripheral arthritis | Paper or electronic | Current | Physical examination | SJC: 0-66 TJC: 0-68 |

Not defined | N/A as disease-specific measure | N/A as physical examination |

| Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI) | 6 sites | MSK disease activity: enthesitis | Paper or electronic | Current | Physical examination | 0-6 | Not defined | N/A as disease-specific measure | N/A as physical examination |

| SPARCC Enthesitis Index | 18 sites | MSK disease activity: enthesitis | Paper or electronic | Current | Physical examination | 0-16 | Not defined | N/A as disease-specific measure | N/A as physical examination |

| Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI) | 20 digits, size and tenderness | MSK disease activity: dactylitis | Paper or electronic | Current | Physical examination | Not defined | Not defined | N/A as disease-specific measure | N/A as physical examination |

| Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) | 4 scores, 4 areas | Skin activity: psoriasis | Paper or electronic | Current | Physical examination | 0-72 | Score of >10 generally considered moderate to severe psoriasis. | N/A as disease-specific measure | N/A as physical examination |

| Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) | 0-8 for each nail, 10-20 nails | Skin activity: nails | Paper or electronic | Current | Physical examination | Fingers only: 0-80; fingers and toes: 0-160 | NAPSI<20 Is considered mild disease | N/A as disease-specific measure | N/A as physical examination |

| Modified NAPSI (mNAPSI) | 13 for each nail, 10-20 nails | Skin activity: nails | Paper or electronic | Current | Physical examination | Fingernails: 0-130 | Not defined | N/A as disease-specific measure | N/A as physical examination |

| Patient Global Assessment (PtGA) | 1-3 | Patient global | Paper or electronic | 1 week | Questionnaire | 0-100 VAS or 0-10 NRS | Cut off of <20 used in minimal disease activity | N/A as disease-specific measure | Yes |

| Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) | 9 or 12 | Disease-specific HRQoL | Paper or electronic | 1 week | Questionnaire | 0-10 | <4 is considered a patient-acceptable symptom state | N/A as disease-specific measure | Yes |

| Composite Outcome Measures | |||||||||

| ACR20/ 50/ 70 (12) | 7 | Joints global pain function APR | Paper | 1 week | Physical examination, questionnaires, and laboratory test | Binary | Binary | N/A as disease-specific measure | Limited data although used internationally |

| MDA (98) | 7 | Joints enthesitis skin global pain function | Paper, electronic, or GRAPPA app | 1 week | Physical examination and questionnaires | Binary | ≥5/7 cutpoints met = MDA; all 7/7 cutpoints met = VLDA | N/A as disease-specific measure | Limited data although used internationally |

| DAPSA/ cDAPSA (115) | 5/ 4 | Joints global pain | Paper or electronic | 1 week | Physical examination, questionnaires, and laboratory test | 0-154 | Remission≤4 LDA≤14/13 ModDA≤28/27 HighDA≥28/27 |

N/A as disease-specific measure | Limited data although used internationally |

| CPDAI (123) | 9 | Joints enthesitis skin dactylitis axial | Paper or electronic | 1 week | Physical examination and questionnaires | 0-15 | Near-remission ≤2 LDA≤3 or 4 |

N/A as disease specific measure | Limited data although used internationally |

| PASDAS (129) | 8 | Joints global enthesitis dactylitis QoL APR | Paper or electronic | 1 week | Physical examination, questionnaires, and laboratory test | 0.4-11 | Near rem≤1.9 LDA ≤3.2 ModDA ≤5.4 HighDA>5.4 |

N/A as disease specific measure | Limited data although used internationally |

| GRACE (129) | 8 | Joints skin global function QoL | Paper | 1 week | Physical examination and questionnaires | 0-10 | Not available | N/A as disease specific measure | Limited data although used internationally |