Abstract

This study explores scholars’ approaches to measure performance in nonprofit human service organizations. While acknowledging that each human service organization’s unique mission makes it challenging to create a generalizable model across all nonprofit human service organizations, we propose three multidimensional frameworks for performance measurement derived from survey and qualitative data of organizations in this subsector. The frameworks will help researchers and practitioners rethink, adapt to, and reflect on the implications of their current methods of program performance measurement. While contributing to the academic discussion on the measurements used to evaluate human service organizations’ program performance, our research also offers important insights for researchers, managers, marketers, board members, and funders to use moving forward.

Keywords: Multidimensional frameworks, Performance models, Human service organizations, Performance measurement, Program performance

Introduction

Nonprofit organizations measure program outcomes for several reasons. Many rely on metrics to determine program effectiveness, budget projection accuracy, and mission achievement (Behn, 2003). Often, nonprofit organizations publicize their intended and unintended successes to the clients they serve and potential donors and stakeholders they wish to influence to increase client and donor bases. As nonprofit organizations face increasing pressure to fundraise, anecdotal evidence shows that effective nonprofits with measurable results will attract more funding. With the pressure to show results, there has been an ongoing interest and call for research on program performance and outcome measurement, and this is especially true for human service organizations (Bryan & Brown, 2015; Stone & Cutcher-Gershenfeld, 2002).

Human service organizations “share an overall goal of improving their clients’ quality of life by providing assistance aimed at resolving the crisis, creating stability, or fostering development and improvement” (Mensing, 2017, p.207). This broad conceptualization captures organizations in varying service areas from economic development to group homes, from family services to emergency assistance, from senior services to childcare. While this definition does not limit human service organizations’ work to the third sector, this study focuses specifically on nonprofit human service organizations. While there are many ways to categorize nonprofit human service organizations, one useful illustration is the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities’ (NTEE) ‘Core Codes’ which identifies eight subgroups of human service organizations including crime and legal-related; employment, food, agriculture, and nutrition; housing and shelter; public safety, disaster preparedness and relief; recreation and sports; youth development; and human services (National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities, 2020).

Given the variety of organization types in the broader category of human service organizations, standardization and generalizability program outcome measurement is nearly impossible. While the literature exploring the successes and failures of human service organizations is extensive, nonprofit practitioners and researchers face many challenges in their program outcome measurement approaches. These challenges illustrate the diversity of research approaches in this field. Even the most straightforward task of finding a standard definition of program effectiveness and efficiency is problematic (see Sowa et al., 2004; Mitchell, 2015).

As a result of the multidimensional and socially constructed nature of evaluating organizational performance and program outcomes (Herman & Renz, 2008; Williams & Taylor, 2012), few academic articles examine researchers’ methodological practices and processes in determining the best way to measure program outcomes in human service organizations (Bryan & Brown, 2015; Packard, 2010; Stone & Cutcher-Gershenfeld, 2002). Thus, we ask the following questions: How do nonprofit scholars measure program performance in nonprofit human service organizations? What practices and processes exist to measure successes and failures in these organizations? Is there a “best” way for researchers to operationalize the measurement of the program performance?

This research aims to advance knowledge on program outcome measurement in nonprofit human service organizations while acknowledging that each organization’s unique mission makes it challenging to create a generalizable model across all nonprofit human service organizations. Using survey and qualitative data on outcome measurement from a subset of nonprofit human service organizations, we propose three multidimensional frameworks to measure program performance. The frameworks will help researchers and practitioners rethink and reflect on the implications of their current methods of program performance measurement. While contributing to the academic discussion on the measurements used to evaluate human service organizations’ program performance, our research also offers important insights for researchers, managers, marketers, board members, and funders to use moving forward.

Literature Review

Performance measurement, the tool with which organizations can measure their progress toward achieving their goals or mission, has inspired wide-ranging literature within the nonprofit sector and the public and private sector literature. This study contributes to this body of literature by exploring the nature of multidimensional performance measurement in human service nonprofit organizations, specifically. This literature review will explore human service organizations to set parameters for the organizations included in the study, provide an overview of the literature on performance measurement in nonprofit organizations, and look more closely at multidimensional performance measurement specific to human service nonprofit organizations.

Understanding Performance and the Limitations

Much like performance measurement, the literature describes performance itself as a vast and multidimensional concept. Poister (2008) describes the components of performance, including “effectiveness, operating efficiency, productivity, service, quality, customer service, and cost-effectiveness” (p.3). Berman (2015) suggests that organizational “performance is about keeping public and nonprofit organizations up-to-date, vibrant, and relevant to society” (p.3). As such, the varying dimensions of performance are leveraged by nonprofit professionals and scholars to show stakeholders their value and achievements toward overarching goals (Micheli & Kennerley, 2005; Micheli & Mari, 2014). Given the vast nature of performance overall, the measures and indicators developed to describe and quantify it are equally extensive.

Despite the broad nature of performance definitions, they all relate back to a common core, success in relation to an organization’s objectives and goals (Cho & Dansereau, 2010; Tomal & Jones, 2015). In nonprofit human service organizations, performance itself may be the measurement of organizational progress against mission attainment, but performance can also take into account factors and norms external to the organization (i.e., legal measures, environmental complexity, technical requirements) (Andrews et al., 2006; Richard et al., 2009). When organizations undertake performance measurement, the choice of which factors to measure, both internal and external to the organization, dictate the scope of the evaluation. (Buonomo et al., 2020).

Nonprofit human service organizations undertake measuring performance to define the multidimensional aspects of performance through performance indicators, observe them in light of organizational activity, and measure progress toward overarching organizational goals (Poister, 2008). Although each of these steps is a critical way of describing organizational worth to stakeholders, there are limits to this process. In the words of Osborne and Gaebler (1992), “what gets measured gets done.” Performance measurement impacts nonprofit professionals and scholars’ understanding of organizational progress and success (Poister, 2008). Once performance measurement occurs, it becomes more challenging to consider the components of organizational performance that have not been measured (Poister, 2008; Micheli & Kennerley, 2005; Micheli & Mark, 2014). Therefore, organizations tend to focus more attention on the components of performance that are being measured at the expense of those that are not (Micheli & Kennerley, 2005; Micheli & Mari, 2014). Understanding performance, and the activity of performance measurement undertaken by nonprofit organizations, shape our understanding of progress toward organizational goals.

Performance Measurement

Next, we explore the multidimensional measures of program performance within the nonprofit literature. After reviewing how scholars have addressed performance measurement in nonprofit organizations, we conclude by looking more closely at human service nonprofit organizations’ performance measures.

Nonprofit Performance Measurement

For years, nonprofit scholars and practitioners alike struggled to measure performance because the for-profit business models that relied upon financial statements alone were insufficient (Beamon & Balcik, 2008; Forbes, 1998; Henderson et al., 2002). More recent performance measurement approaches had to overcome this nonprofit constraint to display performance measures taking into account much more than financial well-being in the for-profit sense, creating a multidimensional understanding of performance (Ebrahim, 2005; Henderson et al., 2002; Herman & Renz, 2008; Kaplan, 2001; Sowa et al., 2004).

Much of the literature on nonprofit performance measurement undertakes the creation, application, and analysis of performance measurement frameworks. These frameworks help nonprofit practitioners develop performance measurement systems (Rouse & Putteril, 2003) and lend some understanding of the many dimensions of nonprofit performance measurement.

One such multidimensional approach to performance measurement developed in the early 2000s, known as the Balanced Scorecard, considers the financial and internal perspectives, customer perspectives, and organizational learning and growth (Chan, 2004; Kaplan, 2001).

The more traditional financial standards of performance, such as debt ratios, rates of overhead spending, budget size, and precise financial controls (Kaplan, 2001), are included from the financial perspective. The internal processes consider innovation and measurable operating performances, such as organizational capacity. The customer perspective relies on “market share, customer retention, new customer acquisition, and customer profitability” (Kaplan, 2001, p.357). In the nonprofit space, these “customers” are “clients.” Finally, the organizational learning and growth perspective measures employee motivation, capacity, and mission alignment. The balanced scorecard has been used in many sectors and applied to the nonprofit sector throughout the literature (Chan, 2004; Gumbus & Wilson, 2004; Messeghem et al., 2018; Niven, 2008; Perkins & Fields, 2010; Ronchetti, 2006).

Another framework, known as the Multidimensional and Integrated Model of Nonprofit Organizational Effectiveness, looks at nonprofit effectiveness at two levels; management and programmatic, each broken down into capacities and outcomes (Sowa et al., 2004). The first level, management capacity, captures the “characteristics that describe an organization and the actions of managers within it” (Sowa et al., 2004 p.714), such as leadership attitude, leadership evaluations, leadership tenure, staff turnover, and strategic planning and board performance (Brown, 2005; Green & Griesinger, 1996). Meanwhile, the programmatic level focuses on services provided, intervention strategies, and program capacity.

Frameworks such as those proposed by Sowa et al. (2004) and Kaplan (2001) provide a valuable mechanism for organizing and conceptualizing nonprofit performance measurement. However, there is a wealth of literature that expands the performance measurement categories, as mentioned above. The literature addresses the need for performance measurement to be aligned with the organizational mission (Sheehan Jr., 1996; Sawhill & Williamson, 2001). It also broadens how nonprofit organizations can balance financial measures like fundraising efficiency, continuous improvement, and public support (Lu et al., 2020; Ritchie et al., 2007). A 2016 study by Willems suggests that within the nonprofit setting, the mental models of nonprofit leadership impact organizational performance. They measured facets like leadership team dynamics and stakeholder involvement in decision-making to impact nonprofit performance in moments of crisis (Willems, 2016). Not only is leadership attitude impactful, but so is the experience (positive or negative) of the clients served (Carman, 2007). Still, others focus on the social connection between an organization and its community, specifically their ability to leverage social capital (Moldavanova & Goerdel, 2018).

Recently, nonprofit organizations are connecting organizational resilience to performance. Organizational resilience is defined as “the dynamic capability of an enterprise, which is highly dependent on its individuals, groups, and subsystems, to face immediate and unexpected changes in the environment with proactive attitude and thought, and adapt and respond to these changes by developing flexible and innovative solutions” (Kamalahmadi & Parast, 2016, p. 124). Specific to nonprofit organizations, organizational residence is “the ability of an organization to respond and adapt to incremental changes and sudden disruptions while also constantly anticipating and preparing for future challenges in order to sustainably meet [the organization’s] mission” (Quad Innovation Partnership, 2020, p. 2). Organizational resilience has been measured through a variety of key performance indicators that differ depending on the type of organization, including financial security, ability to innovate, strength of an organization’s mission, personnel and culture, collaboration and community outreach, diversity, and organizational values among many others. Given the nature of the nonprofit sector with competing organizations working on similar causes and competing for resources, in addition to the recent pitfalls and consequences of externalities such as the coronavirus pandemic, it is important to consider the factors that might determine a nonprofit organization’s resilience in the sector.

Nonprofit Human Service Organization Performance Measurement

The breadth of literature on performance measurement provides a convincing argument for the multidimensional nature of nonprofit performance measurement, and this is especially applicable to nonprofit human service organizations whose missions widely vary (Carnochan et al., 2014; Kim, 2005). The diversity of clients served makes identifying appropriate measures even more challenging (Carnochan et al., 2014). Many social service nonprofits have resigned to the most straightforward measure of organizational performance; the number of people served (Carman, 2007). However, there are numerous other performance measurements identified in the literature.

LeRoux and Wright (2010) suggest overcoming the hurdles facing these organizations by including client perspectives in creating performance measures, providing staff with access to the data they need and creating a diversity of funding streams. Sufficient program funding and effective and efficient resource allocation, and staff motivation and commitment to the program have also been identified as significant factors in determining the success or failure of nonprofit human service organization programming (Packard, 2010). Scholars also measure the professionalism of nonprofit human service organization staff related to performance and found a positive relationship between performance and employee empowerment, control, equity, training, and working conditions (Schmid, 2002).

In the past, nonprofit organizations, including those in the human services space, have struggled to create meaningful organizational and programmatic performance measures. The response to this hardship has been to create a multidimensional understanding of performance measurement that considers organizational finances, like in the for-profit sector, and nonprofit leadership, management, programs, funding, and clients.

Proposed Multidimensional Frameworks for Performance Measurement

This section proposes three multidimensional frameworks to measure the performance of nonprofit human service organizations. The frameworks are derived from the constructs and variables discussed in the literature above in addition to survey data on the characteristic used to evaluate the program effectiveness of 396 nonprofit human service organizations. Survey data were collected by Excellence in Giving's (2020) Nonprofit Analytics Program and include both qualitative and quantitative metrics of program effectiveness. In addition, survey and qualitative data from a study on nonprofit organizational resilience in human service organizations are also used to develop the frameworks since resiliency is often determined by performance indicators. The resiliency study was conducted by the Quad Innovation Partnership (2020) to identify the factors that define and determine organizational resilience. The survey data and qualitative information collected from the organizational resilience study were analyzed and compared to existing frameworks in the nonprofit performance measurement literature, creating three new multidimensional frameworks to measure nonprofit human service program performance.

The multidimensional frameworks below focus on the constructs of financial performance, clients served, and organizational resilience. Since the three constructs are closely related, the frameworks include similar variables but are distinct from one another. The proposed frameworks are intended to assist future researchers and practitioners as they develop dynamic measurement systems that track performance over time. We anticipate the frameworks can also be used to compare program outcomes between organizations. In the following subsections, we describe each multidimensional framework, offer insights into potential ways to operationalize the framework’s components, and discuss its advantages and limitations. We must note, however, that the frameworks offered below are only a starting point for practitioners and researchers. Individual organizations will need to determine whether variables in the framework are specific to their organization and whether essential variables are missing. Since human service organizations come in many sizes and forms, the frameworks are to be used as a starting point that can be built upon and adapted to each organization’s needs.

Financial Performance Framework

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the financial performance framework consists of seven financial indicators that would allow a scholar or practitioner to gain insight into a nonprofit human service organization’s success. As exemplified by the fundraising diversity and overhead spending indicators, the framework highlights the importance of a variety of funding sources and a willingness to pay for fundraising and qualified leaders when measuring a nonprofit human service organization’s financial success. The proposed framework also highlights the importance of measuring the number of individual donors and the organization’s size through public financial support and capacity indicators. All of the financial performance framework components can be operationalized from information that most human service nonprofit organizations track. Financial capacity may be more challenging to operationalize, but potential options include total income plus total expenses, total income, or total program service expenses.

Fig. 1.

A visualization of the financial performance framework

A strength of the financial framework is that it allows scholars and practitioners to create an easily operationalizable measure of an organization’s performance. Most, if not all, of our proposed indicators are easily operationalized, as illustrated from the Excellence in Giving (2020) survey and qualitative data. Examples include easily accessible debt to equity measures and funding source data. Many variables in the financial framework can be operationalized from information nonprofit human service organizations provide to the Internal Revenue Service in the U.S. and other governing agencies. A weakness of the financial performance measurement framework is that it is internally focused.

Clients Served Performance Framework

The clients served performance framework in Fig. 2 predicts that size, quality, and leaders’ attitudes are associated with the number of clients served in a human service organization. With more staff, nonprofits can serve more people. Financial capacity is also an essential component of the clients served framework since financial stability increases the number of clients served. Finally, social capital and the community characteristics where the organization works are also critical in affecting the number of clients served. An organization’s standing in a community and the characteristics of that community can affect the number of people willing to come to that organization for a service while impacting its ability to attract donors and influence public perception surrounding its mission. Social capital and community characteristics could be operationalized through coding of an independently conducted survey given to a diverse array of community members. Special care should be given to how those community members are selected.

Fig. 2.

A visualization of the clients served performance framework

While not as easy to operationalize as the financial performance framework, many of the components in the clients served framework are derived from information that most human service nonprofit organizations track. Quantitative examples include staff and organizational size, operating budget size, and financial security. Many organizations also qualitatively assess the attitudes of leaders by tracking media releases or through personal contact. The more conceptual variables, such as attitudes of leaders and social capital levels, may require surveying staff, clients, or community members. A weakness of this framework is that some of the components of the framework are difficult to operationalize.

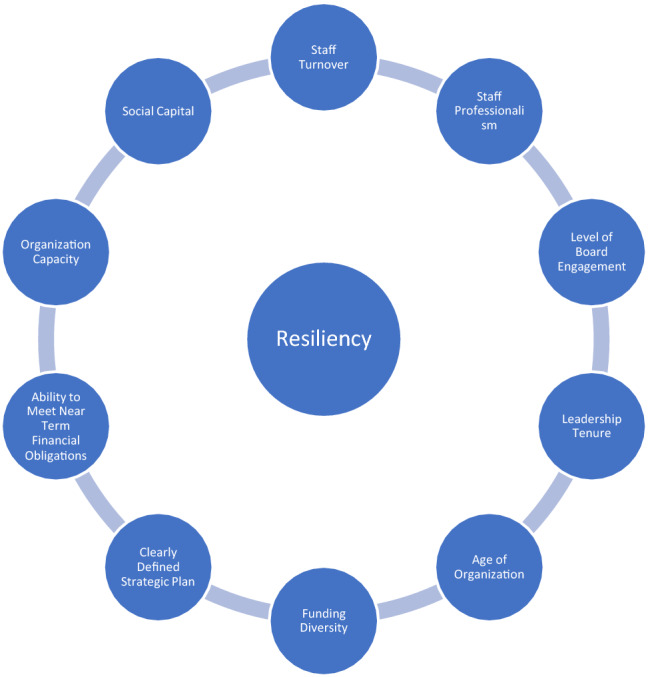

Resiliency Framework

As shown in Fig. 3, the resiliency framework consists of ten indicators that will allow a scholar or practitioner to gain insight into a nonprofit human service organization’s resiliency. While the financial and clients served frameworks are conventional organizational performance approaches, the resiliency framework attempts to build a dynamic measure of performance that captures the organization’s more intangible aspects.

Fig. 3.

A visualization of the resiliency framework

The resiliency framework adopts components from the financial and clients served frameworks, including funding diversity, organizational capacity, and social capital. However, the resiliency framework also highlights the importance of longevity when determining an organization’s resilience. Indicators of longevity include the age of organizations, leadership tenure, and staff turnover. Another common theme seen in our resiliency framework is the importance of qualified and active staff and board members. Actively engaged, quality team members are more likely to have planned for unusual issues that may arise, problem-solving in real-time, and learning from previous mistakes going forward. As indicated by an organization’s ability to meet its near-term financial obligations and the capacity of an organization, financial success is also predicted to be associated with a nonprofit human service organization’s resiliency.

The variables in this framework may be the hardest to operationalize. Many of the components in this framework are relatively abstract, such as staff professionalism. Scholars and practitioners attempting to operationalize this framework should search for proxy variables that could measure the indicators proposed in this framework. This could include measuring the proportion of staff with a master’s degree or above or certification in their professional field for staff professionalism. More accessible variables to operationalize are staff turnover rates and the ability to meet short-term financial obligations.

The idea of resiliency as a performance measure is undoubtedly hard to operationalize. Resiliency as an outcome could be operationalized quantitatively by the number of years the organization has existed or the number of significant financial or global shocks the organization has weathered. An organization could self-determine what these financial/global shocks are for themselves if this framework is only applied to one organization.

A vital strength of the resiliency framework is that its indicators may be used as a marketing tool for donors. Nonprofit human service organizations can showcase their ability to survive or remain resilient, despite unforeseen external and internal issues that may occur. A weakness of this framework is the difficulty in defining resilience and at what point an organization is resilient. Like the clients served, model, scholars, and practitioners should be creative when attempting to operationalize the resiliency framework.

Summary

Our review of existing frameworks in the nonprofit literature shows that nonprofit human service organizations struggle to find meaningful ways to measure performance. Many of the frameworks researchers and practitioners use are adapted from the private sector or other nonprofit subsectors (Beamon & Balcik, 2008; Forbes, 1998; Henderson et al., 2002). Most are insufficient when measuring performance. Thus, we set out to develop useful multidimensional frameworks that reflect nonprofit human service organizations’ work and that can be adapted to each individual organization. We believe the three frameworks above will be useful tools for performance measurement in financial performance, clients served, and organizational resilience. The frameworks are created from an analysis of the evaluation and resiliency data of nonprofit human service organizations. While this article only provides an overview of the three frameworks’ variables and constructs, we encourage and challenge nonprofit scholars to operationalize and test each model so that we may learn from one another in our efforts to advance research approaches in our field.

Conclusions

Moving forward, in research and practice, we should remain cognizant of the implications of the program performance measures utilized. Reliance on any particular framing to others’ expense can have a significant impact on other equally worthy goals of an organization. For example, overreliance on financial performance measures can force decisions to stop services to a client population or unnecessarily increase caseloads. Whereas overreliance on clients served or resiliency can be more costly. Testing these frameworks in future research, and developing a scoring rubric for each framework, can help further refine their efficacy in practice; thus creating opportunities to develop clear operationalizations of the more abstract concepts such as staff professionalism, social capital, and leaders’ attitudes. There are various methodological approaches in assessing the performance in human service organizations, and organizations should seek to balance programmatic goals with stakeholder and community input. This brief exploration of the methods that human service organizations measure performance and how researchers have investigated it provides an assessment of the current practices and research in the field and will help students, practitioners, and scholars alike evaluate their performance measures and further understand the sector.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript. No funding was received for conducting this study. No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article

Data Availability

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Human or Animal rights

No research involving human participants. Data are secondary dataset.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Katrina Miller-Stevens, Email: katrina.millerstevens@coloradocollege.edu.

Zachariah Benevento-Zahner, Email: z_beneventozahner@coloradocollege.edu.

Gabrielle L’Esperance, Email: gehenderson@unomaha.edu.

Jennifer A. Taylor, Email: Taylo2ja@jmu.edu

References

- Andrews R, Boyne GA, Walker RM. Subjective and objective measures of organizational performance: An empirical exploration. Public Service Performance; 2006. pp. 14–34. [Google Scholar]

- Beamon BM, Balcik B. Performance measurement in humanitarian relief chains. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 2008;11(2):101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Behn RD. Why measure performance? Different purposes require different measures. Public Administration Review. 2003;62(5):586–606. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WA. Exploring the association between board and organizational performance in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2005;15(3):317–339. doi: 10.1002/nml.71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TK, Brown CH. The individual, group, organizational, and community outcomes of capacity-building programs in human service nonprofit organizations: Implications for theory and practice. Human Service Organizations: Management Leadership Governance. 2015;39(5):426–443. [Google Scholar]

- Buonomo I, Benevene P, Barbieri B, Cortini M. Intangible assets and performance in nonprofit organizations:A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman JG. Evaluation practice among community-based organizations: Research into the reality. American Journal of Evaluation. 2007;28(1):60–75. doi: 10.1177/1098214006296245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carnochan S, Samples M, Myers M, Austin MJ. Performance measurement challenges in nonprofit human service organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2014;43(6):1014–1032. doi: 10.1177/0899764013508009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LY. Performance measurement and adoption of balanced scorecards. A survey of municipal governments in the USA and Canada. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 2004;17(3):204–221. doi: 10.1108/09513550410530144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, Dansereau F. Are transformational leaders fair? A multi-level study of transformational leadership, justice perceptions, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly. 2010;21(3):409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim A. Accountability myopia: Losing sight of organizational learning. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2005;34(1):56–87. doi: 10.1177/0899764004269430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Excellence in Giving. (2020). Nonprofit analytics program, Retrieved from. https://www.excellenceingiving.com/nonprofit-analytics

- Forbes DP. Measuring the unmeasurable: Empirical studies of nonprofit organization effectiveness from 1977 to 1997. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 1998;27(2):183–202. doi: 10.1177/0899764098272005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green JC, Griesinger DW. Board performance and organizational effectiveness in nonprofit social services organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 1996;6(4):381–402. doi: 10.1002/nml.4130060407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbus A, Wilson T. Designing and implementing a balanced scorecard: Lessons learned in nonprofit implementation. Clinical Leadership & Management Review. 2004;18(4):226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson DA, Chase BW, Woodson BM. Performance measures for NPOs. Journal of Accountancy. 2002;193(1):63. [Google Scholar]

- Herman RD, Renz DO. Advancing nonprofit organizational effectiveness research and theory: Nine theses. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2008;18(4):399–415. doi: 10.1002/nml.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamalahmadi M, Parast MM. A review of the literature on the principles of enterprise and supply chain resilience: Major findings and directions for future research. International Journal of Production Economics. 2016;171:116–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RS. strategic performance measurement and management in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2001;11(3):353–370. doi: 10.1002/nml.11308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SE. Balancing competing accountability requirements: challenges in performance improvement of the nonprofit human services agency. Public Performance & Management Review. 2005;29(2):145–163. doi: 10.2307/3381265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoux K, Wright NS. Does performance measurement improve strategic decision making? Findings from a national survey of nonprofit social service agencies. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2010;39(4):571–587. doi: 10.1177/0899764009359942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Shon J, Zhang P. Understanding the dissolution of nonprofit organizations: A financial management perspective. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2020;49(1):29–52. doi: 10.1177/0899764019872006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messeghem K, Bakkali C, Sammut S, Swalhi A. Measuring nonprofit incubator performance: Toward an adapted balanced scorecard approach. Journal of Small Business Management. 2018;56(4):658–680. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Micheli P, Kennerley M. Performance measurement frameworks in public and nonprofit sectors. Production Planning & Control. 2005;16(2):125–134. doi: 10.1080/09537280512331333039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Micheli P, Mari L. The theory and practice of performance measurement. Management Accounting Research. 2014;25(2):147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.mar.2013.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moldavanova A, Goerdel HT. Understanding the puzzle of organizational sustainability: Toward a conceptual framework of organizational social connectedness and sustainability. Public Management Review. 2018;20(1):55–81. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1293141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities. (2020). NTEE core codes (NTEE-CC) overview. Retrieved from. https://nccs.urban.org/project/national-taxonomy-exempt-entities-ntee-codes

- Niven PR. Balanced scorecard: Step-by-step for Government and nonprofit agencies. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Packard T. Staff perceptions of variables affecting performance in human service organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2010;39(6):971–990. doi: 10.1177/0899764009342896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DC, Fields D. Top management team diversity and performance of Christian churches. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2010;39(5):825–843. doi: 10.1177/0899764009340230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quad Innovation Partnership. (2020). Organizational resilience, Retrieved from https://www.quadcos.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Organizational-Resilience-Sept-2020.pdf

- Richard PJ, Devinney TM, Yip GS, Johnson G. Measuring organizational performance: Towards methodological best practice. Journal of Management. 2009;35:718–804. doi: 10.1177/0149206308330560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie WJ, Kolodinsky RW, Eastwood K. Does executive intuition matter? An empirical analysis of its relationship with nonprofit organization financial performance. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2007;36(1):140–155. doi: 10.1177/0899764006293338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ronchetti JL. An integrated Balanced Scorecard strategic planning model for nonprofit organizations. Journal of Practical Consulting. 2006;1(1):25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse P, Putterill M. An integral framework for performance measurement. Management Decision. 2003;41(8):791–885. doi: 10.1108/00251740310496305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhill JC, Williamson D. Mission impossible?: Measuring success in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2001;11(3):371–386. doi: 10.1002/nml.11309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid H. Relationships between organizational properties and organizational effectiveness in three types of nonprofit human service organizations. Public Personnel Management. 2002;31(3):377–395. doi: 10.1177/009102600203100309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan RM., Jr Mission accomplishment as philanthropic organization effectiveness: Key findings from the excellence in philanthropy project. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 1996;25(1):110–123. doi: 10.1177/0899764096251008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sowa JE, Selden SC, Sandfort JR. No longer unmeasurable? A multidimensional integrated model of nonprofit organizational effectiveness. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2004;33(4):711–728. doi: 10.1177/0899764004269146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone MM, Cutcher-Gershenfeld S. Challenges of measuring performance in nonprofit organizations. In: Flynn P, Hodgkinson VA, editors. Measuring the impact of the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit and civil society studies (An International Multidisciplinary Series) Boston, MA: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tomal DR, Jones KJ. A comparison of core competencies of women and men leaders in the manufacturing industry. The Coastal Business Journal. 2015;14(1):13. [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, Taylor JA. Resolving accountability ambiguity in nonprofit organizations. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 2012;24:559–580. doi: 10.1007/s11266-012-9266-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.