Abstract

Rationale: Ambient ultrafine particles (UFPs; with an aerodynamic diameter < 0.1 μm) may exert greater toxicity than other pollution components because of their enhanced oxidative capacity and ability to translocate systemically. Studies examining associations between prenatal UFP exposure and childhood asthma remain sparse.

Objectives: We used daily UFP exposure estimates to identify windows of susceptibility of prenatal UFP exposure related to asthma in children, accounting for sex-specific effects.

Methods: Analyses included 376 mother–child dyads followed since pregnancy. Daily UFP exposure during pregnancy was estimated by using a spatiotemporally resolved particle number concentration prediction model. Bayesian distributed lag interaction models were used to identify windows of susceptibility for UFP exposure and examine whether effect estimates varied by sex. Incident asthma was determined at the first report of asthma (3.6 ± 3.2 yr). Covariates included maternal age, education, race, and obesity; child sex; nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and temperature averaged over gestation; and postnatal UFP exposure.

Measurements and Main Results: Women were 37.8% Black and 43.9% Hispanic, with 52.9% reporting having an education at the high school level or lower; 18.4% of children developed asthma. The cumulative odds ratio (95% confidence interval) for incident asthma per doubling of the UFP exposure concentration across pregnancy was 4.28 (1.41–15.7), impacting males and females similarly. Bayesian distributed lag interaction models indicated sex differences in the windows of susceptibility, with the highest risk of asthma seen in females exposed to higher UFP concentrations during late pregnancy.

Conclusions: Prenatal UFP exposure was associated with asthma development in children, independent of correlated ambient NO2 and temperature. Findings will benefit future research and policy-makers who are considering appropriate regulations to reduce the adverse effects of UFPs on child respiratory health.

Keywords: prenatal, ultrafine particles, child asthma, sex-specific, sensitive windows

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Ambient ultrafine particles (UFPs; with an aerodynamic diameter < 0.1 μm) may exert greater toxicity than other pollution components because of their enhanced oxidative capacity and ability to translocate systemically. Studies examining associations between prenatal UFP exposure and childhood asthma risk remain sparse, with no prior studies having been conducted in the United States.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This is the first U.S. study to link prenatal UFP exposure with asthma development in children while accounting for sex-specific effects. Prenatal UFP exposure was associated with asthma development in children, independent of correlated ambient NO2 and temperature. Findings will benefit future research and policy-makers who are considering appropriate regulations to reduce the adverse effects of UFPs on child respiratory health.

Coordinated functioning of interactive networks are central to optimal lung development and maintenance of respiratory health (1). Regulatory systems susceptible to environmental programming, including the neuroendocrine, autonomic, and immune-function systems, influence disease vulnerability. Subcellular components impacting asthma expression (e.g., mitochondria) (2, 3) are also targets (4). Starting in utero, environmental factors, including air pollutants, can organize these processes toward enhanced pediatric disorders, including asthma (5, 6).

Studies linking prenatal air pollution exposures and childhood asthma largely consider criteria pollutants, which are routinely monitored to assess air quality, specifically particulate matter (PM) with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) (7–10). Although mechanisms are multifactorial, oxidative stress plays a central role in air pollution toxicity (11). Ambient ultrafine particles (UFP; with an aerodynamic diameter < 0.1 μm) may exert greater toxic effects than these other components because of their larger surface area–to–mass ratio, enhanced oxidative capacity, deeper lung penetration, and ability to more readily translocate to the systemic circulation (12, 13). Prospective studies examining associations between UFP exposure, starting in pregnancy, and childhood asthma remain sparse. Moreover, because ultrafine PM is not regulated, UFPs are not monitored at regulatory stations, limiting the capacity to estimate long-term exposures (14). Studies linking UFP exposure with child health have focused on short-term exposure because of a lack of adequate spatiotemporal modeling (15).

Lavigne and colleagues (16) developed a spatiotemporal UFP land-use regression (LUR) model for Toronto, Ontario, Canada, which was based on mobile monitoring (2 wk in summer and 1 wk in winter focused on the morning/evening rush hours on weekdays) and used a scaling approach to expand temporal coverage over a 9-year period. For each participant, UFP exposure estimates were assigned for each week of pregnancy at the centroid of the postal code (i.e., approximating a city block). Analyses combining data from a province-wide birth registry (160,541 singleton live births) with health administrative data found an association between prenatal UFP exposure, particularly in the second trimester, and greater asthma risk. Associations remained when adjusted for PM2.5 and NO2 in separate models. Although the study had notable innovations (17), the spatial and temporal resolution of the exposure models (i.e., city block, nondaily estimations, limited scope of the UFP monitoring campaign) could result in exposure misclassification due to spatial and temporal misalignment (18). Moreover, a cumulative body of evidence will be needed to advance the regulation of UFPs. Notably, UFPs differ from more widely studied pollutant components in that they behave differently in the air and have different elevation patterns in relation to time and across geographic areas. Thus, examining associations between prenatal UFP exposure and child asthma risk in additional geographic locations is an important contribution to building this evidence base.

We leveraged a validated spatial–temporal UFP model (14) combined with data from two pregnancy cohort studies constituting a lower-income, ethnically mixed urban sample in the northeastern United States to examine associations between the daily average prenatal UFP exposure and incident childhood asthma, adjusting for correlated pollutant and climate-related exposures. Novel modeling approaches for UFPs allowed accurate daily estimations while providing residence-level exposures. We implemented data-driven methods to flexibly identify windows of susceptibility in relation to UFP effects. Effect modification by sex was examined. Some of the results of these analyses have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (19).

Methods

Participants were mothers and full-term (⩾37 weeks’ gestation) singleton-born children from two pregnancy cohort studies residing in the relevant catchment area and enrolled within a timeframe for which UFP estimates could be assigned over gestation and 1 year postnatally (i.e., starting on January 1, 2003). Both cohorts, led by our team of investigators, used parallel enrollment procedures and standardized assessment methods.

The ACCESS (Asthma Coalition on Community, Environment and Social Stress) project enrolled 989 English- or Spanish-speaking pregnant women ⩾18 years of age receiving routine prenatal care at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), Boston Medical Center, and the East Boston Community Health Center at 24.3 ± 9.9 weeks’ gestation between August of 2002 and July of 2009. Of these, 955 gave birth to a live-born infant and continued follow-up. Procedures were approved by human studies committees (HSCs) at BWH and Boston Medical Center.

The PRISM (Programming of Intergenerational Stress Mechanisms) study recruited 390 English- or Spanish-speaking women ⩾18 years of age receiving prenatal care from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the East Boston Community Health Center at 21.4 ± 9.1 weeks’ gestation from March of 2011 to December of 2013. Women reporting intake of ⩾7 alcoholic drinks/wk before pregnancy or any alcohol drinks after pregnancy recognition were excluded. Procedures were approved by the HSCs at BWH with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, ceding review to BWH. In both studies, mothers provided written consent in their primary language.

Analyses included mother–child dyads from the ACCESS (n = 252) and PRISM (n = 124) studies with data on UFP exposure and children’s asthma. Characteristics for those included in the analyses were generally similar to those of the overall cohort participants (see the online supplement). Analyses were approved by the HSC at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Children’s Asthma Outcome

Maternally reported asthma in children was ascertained through interviews at approximately 4-month intervals from birth to age 30 months and then annually thereafter. Incident asthma was determined at the first affirmative report of any of the following (3.6 ± 3.2 yr): “Has your child ever had asthma [since birth]?”; “Has your baby been hospitalized overnight for asthma [since birth]?”; “Has a doctor or healthcare provider ever said that your baby had asthma?”; or “Does your baby currently take medicine for his or her asthma?”

Prenatal Air Pollution Exposures

Predicted daily ambient pollutant concentrations across gestation and the first postnatal year were derived for each participant on the basis of their validated geocoded residential address updated for moves, as previously detailed (20).

UFP exposure.

Particle number concentrations (PNCs), a common metric used to characterize the total amount of submicron particles with little mass, served as a proxy of ambient UFP exposure. The PNC was estimated by using an hourly resolution longitudinal model (14) composed of 1) a LUR spatial-factor model, which was developed by using both fixed-site and mobile monitoring data and accounted for spatial variation at a 20-m resolution, and 2) a reference-site model specific to the study area, which accounted for temporal variation at an hourly resolution on the basis of multiple meteorological parameters. Monitoring campaigns (21) and model performance (14) are detailed elsewhere. Briefly, for developing reference-site models, PNCs were monitored continuously (24 h/d, 7 d/wk) in two separate locations, corresponding to two different area-specific models—one for Chelsea (northeast portion of the study area) and one for Boston (southwest portion of the study area). Monitoring occurred from December of 2013 to May of 2015 at the reference site in Chelsea and from December of 2011 to November of 2013 at the reference site in Boston. During the periods of reference-site monitoring, PNCs were also measured via mobile monitoring with the Tufts Air Pollution Monitoring Laboratory (described in Reference 22) in each study area. Mobile monitoring was performed for 46 days in Chelsea and 48 days in Boston in 4- to 6-hour shifts on each monitoring day and between 05:00 and 21:00 hours on all days of the week and in all seasons. Data acquired during mobile monitoring were used to build the LUR-based spatial-factor model. Model performance was stable outside the window of measurement years; for example, Pearson correlations between the model’s hourly predictions and an independent measurement site in the study area (23) ranged between 0.53 and 0.74 over a 9-year retrospective period (2003–2011) and between 0.69 and 0.71 during 2 prospective years (2014–2015).

The UFP models were built from data sets that were influenced primarily by local traffic. The mobile monitoring routes in each study area included both busy urban streets and arterial roadways as well as residential streets with relatively less traffic. Likewise, stationary monitors were located in areas strongly influenced by local traffic conditions. Nonetheless, monitoring occurred under a wide range of conditions; therefore, traffic was not the only UFP source represented. For example, during certain wind conditions, we observed that Logan Airport impacted measurements (24, 25). In addition, models included a term for measured SO2 concentrations as a proxy to account for secondary UFP formation processes.

NO2 exposure.

NO2 exposure was estimated via a validated hybrid model using satellite data, a chemical transport model (GEOS-Chem) and land-use variables, calibrating with ground monitoring data to make predictions at 1 × 1–km grid cells, as described previously (26). A neural network was used to model nonlinearity and interactions between variables, allowing for finer spatial and temporal characterization of patterns of exposure within an urban environment. Model performance was good, demonstrating a cross-validated R2 of 0.79 overall, a spatial R2 of 0.84, and a temporal R2 of 0.73.

PM2.5 exposure.

Temporally and spatially resolved PM2.5 estimates were derived as previously detailed (27). The method uses Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer satellite–derived aerosol optical depth (AOD) measurements for model calibration (stage 1) alongside advanced geostatistical methods when the AOD is not available (stage 2). In stage 1, we combined remote sensing data with traditional LUR predictors and a geospatial smoothing technique to yield daily PM2.5 estimates. The model calibrates the relationship between the satellite-measured AOD and the ground-level monitor–measured PM2.5 with a 1 × 1–km grid cell. Exposure estimates were generated by using linear mixed models with random slopes and intercepts for each day to account for variation in the satellite-to-ground calibration. A second model (stage 2) estimated exposures on days when AOD measures were unavailable (e.g., because of cloud cover, snow, etc.; ranging between 70% and 75% of all observations, depending on region) by using within-season spatial smoothing and the time-varying mean from local ground monitors. Model performance was excellent (mean out-of-sample R2 = 0.88). The spatial (R2 = 0.87) and temporal (R2 = 0.87) components of the out-of-sample results also presented good fits to the withheld data. In addition, our model showed very little bias in the predicted concentrations (slope of predictions vs. withheld observations = 0.99).

Covariates

Women reported age, race, education, and prepregnancy weight (kilograms) and height (meters) at enrollment; each child’s sex, gestational age, and date of birth were extracted from medical records. Maternal atopy was based on a reported history of asthma, eczema, and/or hay fever. Obesity was defined as a body mass index ⩾30 kg/m2. Gestational age was based on maternally reported last menstrual period and obstetrical estimates from the first trimester ultrasound; if the discrepancy was >2 weeks, obstetrical estimates were used. Women reported smoking prenatally as well as secondhand smoke exposure on the basis of other smokers in the home. Prenatal daily temperature was derived by using a model that calibrated Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer satellite surface temperature measurements to air temperature monitors by using LUR (28). NO2 (Spearman correlations of 0.68, 0.60, and 0.69 [P < 0.0001 for all] for the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively) and temperature (Spearman correlations of −0.8, −0.76 and, −0.79 [P < 0.0001 for all] for the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively) were correlated with UFP exposures across pregnancy and were included in the analyses. PM2.5 was not highly correlated with UFPs (Spearman correlations of 0.07, 0.01, and 0.16 [P = 0.15, 0.79, and <0.001, respectively]) and was not considered further in the analyses.

Analysis

We estimated the association between daily average prenatal UFP exposure and asthma incidence by using Bayesian distributed lag interaction models (BDLIMs) (29) and examined differences in both the magnitude and the timing of effects by child sex. This approach assumes that UFP effects in any given exposure window are linear on the logit scale but allows effects to vary nonlinearly across exposure windows. Elevated time-dependent effects represent windows of susceptibility.

The logistic BLDIM for child i (i = 1, . . ., n) who is sex j (j =1 for female, and j = 0 for male) is:

where πi is the probability of the asthma outcome, is the weighted exposure, and is the covariate regression term for subject i, respectively; aj is a fixed sex-specific intercept; and βj is the regression coefficient characterizing the sex-specific association between the weighted UFP exposure and children’s asthma status. The wjt terms identify windows of susceptibility, whereas βj represents the cumulative effect. When weights are constant, using the model is equivalent to using exposure averaged over pregnancy. However, when the weight varies by time, the model assigns greater relative weight to some periods. Briefly, the model uses a smooth orthonormal basis based on the joint distribution of the time-resolved exposure data to smooth the wjt terms (see online supplement for greater detail).

We considered four patterns of effect modification by allowing βj (effect magnitude) and/or the weights wjt (windows of susceptibility) to be sex-specific or the same for both sexes: 1) males and females have different windows of susceptibility, and the within-window association between prenatal UFP exposure and children’s asthma also differs by sex; 2) males and females have different windows of susceptibility but have the same within-window association; 3) males and females have the same windows of susceptibility, but there is a different association between the prenatal UFP exposure and children’s asthma within the window; and 4) males and females have the same windows of susceptibility and within-window association (i.e., no modification). Analyses were conducted by using the “regimes” package in R (version 4.0.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing [29]). Posterior model probabilities were used to help select which of models (1–4) above fit the data best. We considered covariates previously linked to both ambient pollution exposure and childhood asthma risk but not on the causal pathway and confirmed covariates on the basis of the formulation of a directed acyclic graph (30) (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). Models were adjusted for the minimal sufficient adjustment sets for estimating the total effect of prenatal UFP exposure on child asthma, including maternal age, education, race, and obesity; child sex; the average temperature across pregnancy; the NO2 level averaged over pregnancy; and postnatal UFP concentrations averaged over the first year of the child’s life. Finally, sex was considered as a effect modifier. Multiple imputation generating 10 iterations was implemented by using the “mice” package in R (31, 32) to account for missingness in maternal race/ethnicity (4.8%), education (6.4%), atopy (10.1%), and obesity (11.1%). UFP concentrations were transformed with log base 2 to reduce the skewness, and model results are expressed as the odds ratio (OR) of child asthma onset per doubling of the UFP exposure. A multivariate logistic regression model jointly considering trimester-averaged UFP exposures in relation to child asthma was run in a secondary analysis for comparison with the BDLIM results. Sensitivity analyses further adjusted for cohort (ACCESS vs. PRISM) as well as for prenatal smoking and secondhand smoke exposure (major indoor pollution sources), and findings were substantively the same (data not shown).

Results

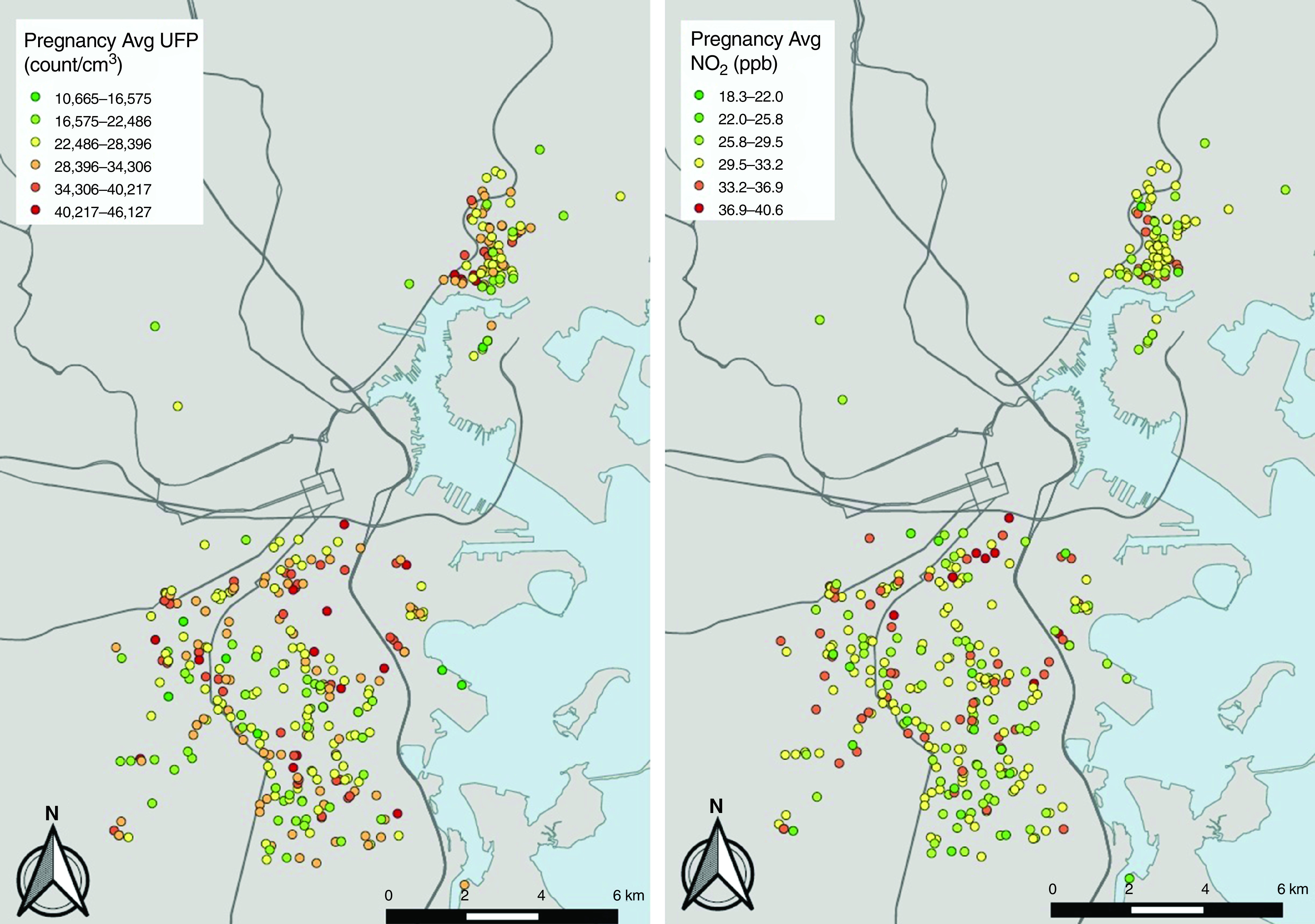

Variability in UFP and NO2 exposures averaged over pregnancy are depicted in Figure 1. Table 1 summarizes sample characteristics. Women were primarily minorities (37.8% Black, 43.9% Hispanic), and 52.9% reported having an education at the high school level or lower. Sixty-nine (18.4%) children developed asthma, which impacted more males than females (22.3% vs. 14.6%, respectively; P = 0.053). There were no significant differences in pollutant exposures based on sex.

Figure 1.

Variability in predicted concentrations of UFPs (left panel) and NO2 (right panel) averaged across the gestational period on the basis of the residential addresses of cohort participants included in analyses. Lines depict major roadways. Avg = average; UFP =ultrafine particle.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (ACCESS n = 252; PRISM-Boston n = 124)

| All Children (N = 376) | Child Sex |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 192) | Male (n = 184) | ||

| Maternal age at enrollment, yr, median (IQR) | 26.8 (22.5–31.9) | 26.9 (22.5–31.9) | 26.7 (22.5–31.9) |

| Maternal prepregnancy obesity, yes, n (%)* | 122 (32.4) | 65 (34.9) | 57 (31.0) |

| Maternal education, ⩽12 yr, n (%) | 199 (52.9) | 105 (54.7) | 94 (51.1) |

| Maternal race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 33 (8.8) | 16 (8.3) | 17 (9.2) |

| Black | 142 (37.8) | 71 (37.0) | 71 (38.6) |

| Hispanic | 165 (43.9) | 89 (46.4) | 76 (41.3) |

| Other/mixed | 36 (9.6) | 16 (8.3) | 20 (10.9) |

| Maternal atopy, yes, n (%)† | 141 (37.5) | 68 (35.4) | 73 (39.7) |

| Prenatal smoking, yes, n (%) | 42 (11.2) | 19 (9.9) | 23 (12.5) |

| Secondhand smoke exposure, yes, n (%) | 83 (22.1) | 34 (17.7) | 49 (26.6) |

| Child asthma, yes, n (%) | 69 (18.4) | 28 (14.6) | 41 (22.3) |

| Child sex, M, n (%) | 184 (48.9) | — | — |

| Prenatal ambient air pollution, median (IQR) | |||

| UFPs, counts/cm3 | 27,842 (24,033–32,302) | 27,477 (24,251–32,128) | 28,187 (23,747–33,085) |

| NO2, ppb | 31.3 (28.9–32.7) | 31.2 (28.9–32.6) | 31.4 (28.9–32.7) |

| Temperature, °C | 11.5 (9.1–13.6) | 12.2 (9.9–13.9) | 10.7 (8.7–13.4) |

Definition of abbreviations: ACCESS = Asthma Coalition on Community, Environment and Social Stress; BMI = body mass index; IQR = interquartile range; PRISM = Programming of Intergenerational Stress Mechanisms; UFP = ultrafine particle.

Maternal prepregnancy obesity is defined as a BMI ⩾30 kg/m2.

Maternal atopy is defined as a history of asthma, eczema, and/or hay fever.

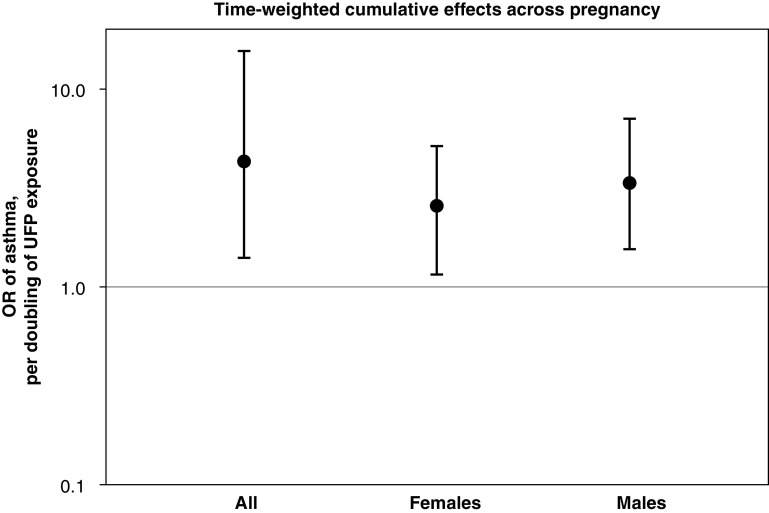

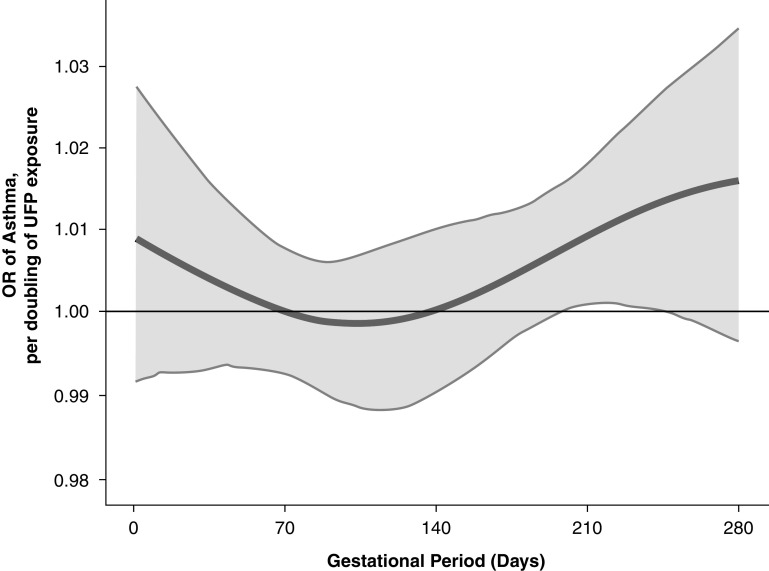

Time-weighted cumulative associations between UFPs and child asthma are shown in Figure 2. The cumulative OR (95% confidence interval) of UFP exposure across pregnancy was 4.28 (1.41–15.7) per doubling of the UFP concentration across pregnancy for the overall sample. Cumulative ORs were similar in males and females. The time-varying association between UFP exposure and child asthma risk are shown in Figure 3. In the overall sample, the BDLIM identified a significant association between increased UFP exposure later in pregnancy (28–35 weeks’ gestation) and increased odds of asthma.

Figure 2.

Time-weighted cumulative effects (odds ratios [ORs]) per doubling of the ultrafine particle (UFP) level across pregnancy on childhood asthma onset estimated by using Bayesian distributed lag interaction models, accounting for both sensitive windows and within-window effects. The models were adjusted for maternal age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, education, prepregnancy obesity, averaged prenatal NO2, averaged prenatal temperature, and averaged UFPs over the first postnatal year (as well as for child sex for the model of the overall sample). Cumulative ORs were significant in both males (OR, 3.37 [95% confidence interval, 1.55–7.06]) and females (OR, 2.56 [95% confidence interval, 1.15–5.11]).

Figure 3.

Odds ratios (ORs) (95% confidence intervals) per doubling of the ultrafine particle (UFP) concentration estimated by using a Bayesian distributed lag interaction model demonstrating the relationship of prenatal UFP exposure and children’s asthma. The model was adjusted for maternal age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, education, prepregnancy obesity, averaged prenatal NO2, averaged prenatal temperature, child sex, and averaged UFPs over the first postnatal year. The x-axis demarcates the gestational age in days. The y-axis represents the OR of developing asthma per doubling of the prenatal UFP exposure. The solid line represents the predicted OR, and the gray area indicates the 95% confidence interval.

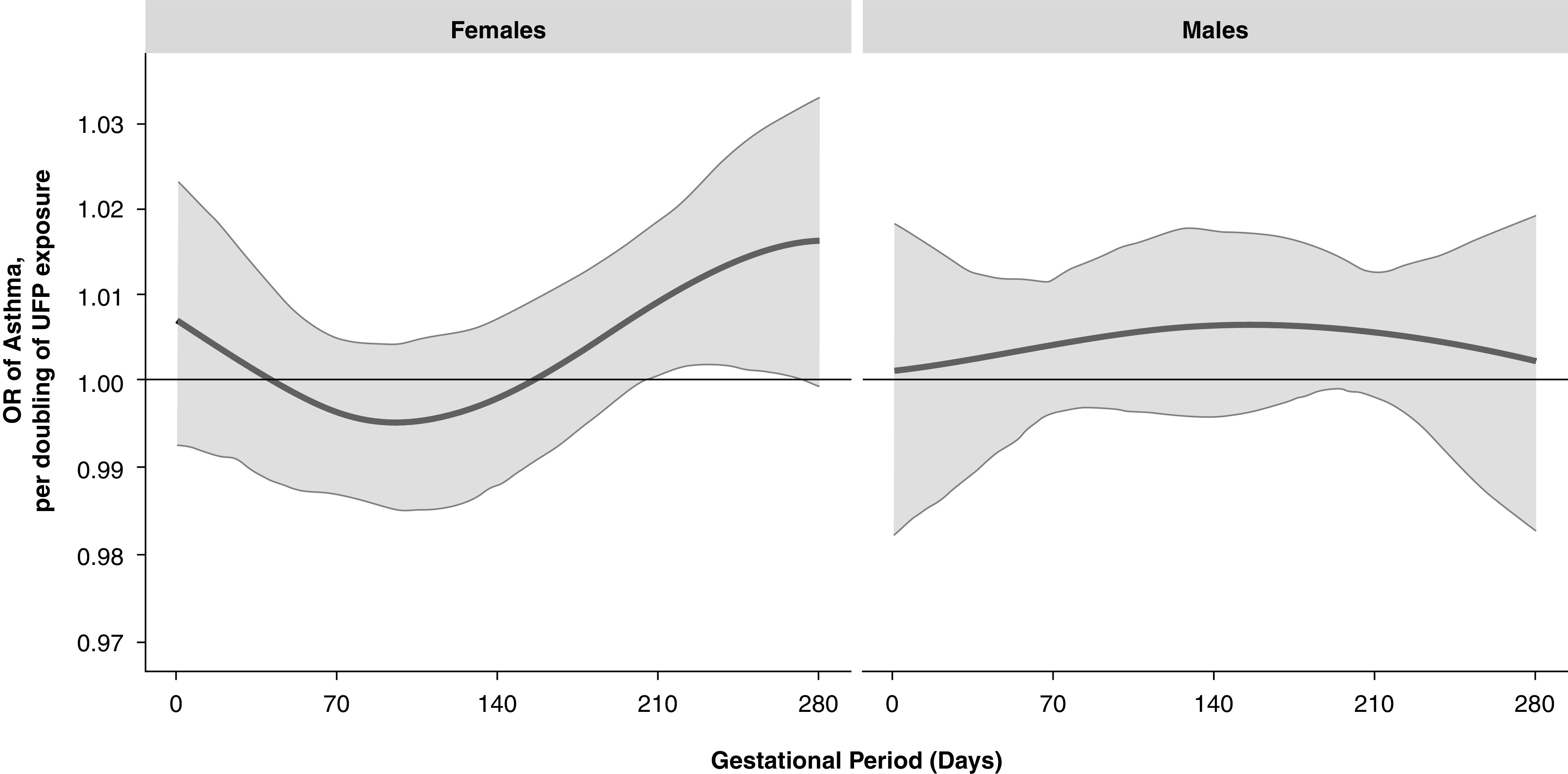

Effect modification by child sex was next examined (Figure 4). On the basis of the posterior model probability and deviance information criterion, the model indicated sex differences in both the sensitive windows and the magnitude of the cumulative association between UFP exposure and childhood asthma. The normalized posterior density of 0.74 supported this as the best-fitting pattern of effect modification. For females, we found the highest risk of childhood asthma when there had been exposure to higher UFP concentrations during the third trimester. For males, all windows of exposure were estimated to be equally important, with risk elevated across the entire pregnancy. Although associations did not reach statistical significance, the persistently elevated risk contributed to the significant overall time-weighted cumulative effect across pregnancy demonstrated in Figure 2 for males. Results from logistic regression modeling using trimester-specific exposure averages were generally consistent, finding that the windows of susceptibility overall was in the third trimester and that this association was most evident in females (Table E1).

Figure 4.

Odds ratios (ORs) (95% confidence intervals) per doubling of the ultrafine particle (UFP) concentration estimated by using a Bayesian distributed lag interaction model demonstrating the sex-specific relationships of prenatal UFP exposure and children’s asthma (left panel, females; right panel, males). The model was adjusted for maternal age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, education, prepregnancy obesity, averaged prenatal NO2, averaged prenatal temperature, and averaged UFPs over the first postnatal year. The x-axis demarcates gestational age in days. The y-axis represents the OR of developing asthma per doubling of the prenatal UFP exposure. The solid line represents the predicted OR, and the gray area indicates the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

This is the first U.S. study to link prenatal UFP exposure with asthma development in children while accounting for sex-specific effects. Although the model examining cumulative UFP effects over gestation showed that both males and females were impacted, models examining sex-specific effects identified a windows of susceptibility in late pregnancy for females, whereas all windows of exposure were important among males.

These analyses extend work linking prenatal ambient UFP exposure and childhood asthma risk in North America. Noteworthy differences in UFP exposure estimation in our work, compared with Lavigne and colleagues (16), are inclusion of additional meteorological parameters that impact UFPs (wind direction and stability class), validation of hourly estimates with independent long-term (14-yr) UFP monitoring data, and UFP monitoring over all time periods of the day on weekdays and weekends. Indeed, the latter may account for why estimated UFP levels in Toronto were higher than those estimated by using our model in the northeastern United States. Our modeling approach also provides more finely resolved UFP exposure data with respect to residence locations and day-to-day variability assessed over longer periods of time. Notably, Lavigne and colleagues (16) found no correlation between UFPs and either NO2 or PM2.5. We found a moderate correlation between UFP and NO2 estimates, whereas UFP concentrations were not correlated with PM2.5. These differences may, in part, be explained by differences in air pollution sources as well as dispersion and depletion processes in the Toronto study area compared with our study area. UFPs are present at highest concentrations near major roadways because of combustion emissions from gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles. In contrast, source apportionment studies in Boston report that most of the PM2.5 mass is sulfate or secondary organic particles transported from distant sources. Our NO2 and UFP prediction models reflect more local roadway combustion contributions, whereas our PM2.5 model captures the long range–transported particles and hence has lower correlation with locally generated UFPs.

The Toronto study found the strongest risk for asthma to be associated with second-trimester UFP exposure, which was followed by a weaker association with third-trimester exposure, although they did not consider sex-specific effects (16). We found that the strongest association between prenatal UFP exposure and asthma in children was in the third trimester, and sex-specific analysis showed that this was driven by females. The BDLIM provides greater flexibility for capturing peaks in the time-varying exposure effect, accounting for more acute changes in exposure and resulting in more powerful inferences, as exemplified through comparison with logistic regression models examining trimester-averaged associations. Although these two strategies yield similar patterns of effects, distributed lag approaches yield more powerful tests of associations because trimester-based approaches average effects from windows of susceptibility with those from periods of no effect, attenuating effect estimates (33). Analyses that more precisely identify windows of susceptibility for exposures (29), combined with knowledge of the molecular and cellular changes contributing to airway development occurring in the identified windows, can provide insights into the underlying mechanisms. The identification of sex-specific windows of vulnerability can help elucidate the etiology of sex differences in the expression of asthma, which remains poorly understood (34, 35).

Mechanisms underlying the effects of airborne particles in fetal development likely involve both indirect (e.g., intrauterine oxidative stress) and direct (e.g., particle translocation) routes. Increased airway and systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in pregnant mothers more highly exposed to particulate air pollution contribute to indirect pathways (1). A recent study finding black carbon particles in villous tissue, indicating that the placental barrier is permeable to airborne particulates, supports more direct routes (36). UFPs may be particularly toxic, given their enhanced oxidative capacity and ability to be more readily translocated (12, 13).

The etiology of the observed sex-specific effects is unclear. Overlapping research shows that particulate-induced oxidative stress disrupts molecular processes involved in lung maturation, including telomere–mitochondrial aging, epigenetics, and gene expression (37, 38) in a sex-specific manner (20, 39, 40). For example, sex-specific gene expression in the developing lung transcriptome (41) and differential regulation of microRNA expression between sexes (42) are described. Recent studies demonstrate sex-specific associations between particular air pollutant exposures in utero and mitochondrial and telomere biomarkers, dosimeters of cumulative oxidative stress at the maternal–fetal interface (20, 38, 43). PM, in particular ultrafine fractions, may have endocrine-disrupting properties contributing to sex differences (44). Disruption in reproductive hormones can alter asthma risk; for example, decreased maternal progesterone during pregnancy has been linked to allergic airway disease among females (45) but not among males. Future studies are needed to corroborate our findings and further examine these mechanisms to better understand the observed sex differences.

The current study has notable strengths, including our environmental assessment methods providing validated hybrid prediction models for daily ambient exposures with high spatial resolution (20 × 20–m grid for UFPs) and ability to adjust for correlated ambient NO2 and temperature. The implementation of data-driven methods to more flexibly identify sensitive windows enhanced the power to detect effects compared with more traditional methods. Research links particulate air pollution with reduced gestational age, which in turn is associated with increased childhood asthma risk (46, 47). Thus, our analyses that restricted on this potential intermediary (i.e., including full-term births, ⩾37 weeks’ gestation) likely underestimates the total effect of UFPs on asthma risk. Some limitations are also worth noting. Although maternally reported early-onset child asthma may result in misclassification, the observed higher incidence in males relative to females (22.3% vs. 14.6%) is consistent with the well-documented natural history of early-life asthma. It is also worth noting prior evidence demonstrating that ambient particulate air pollution exposure is more significantly associated with early-onset asthma (0–3 yr) than later-onset asthma (48), which may reflect enhanced vulnerability to programming effects during critical periods of development, including gestation. Although we adjust for tobacco smoke exposure, we do not fully adjust for household characteristics and other indoor sources and activities that influence indoor UFPs (cooking/heating using gas or fossil fuels, burning candles), and we do not account for indoor infiltration of UFPs of outdoor origin; however, our group and others have demonstrated significant infiltration of UFPs of outdoor origin in homes (24, 49, 50). We also acknowledge that gathering information to assess indoor sources and activities over the long periods of exposure analyzed in the current study would be challenging and present their own possibility of exposure error. In addition, there may be other environmental influences that covary with UFPs that were not considered.

Prenatal exposure to ambient UFPs was associated with asthma development in children, independent of correlated pollutants (NO2) and other climate variables (temperature). Studies differentiating effects associated with UFP exposures from those related to correlated particle size fractions and gaseous copollutants advance the necessary evidence base to move toward regulation of ambient UFPs (51).

Footnotes

ACCESS (Asthma Coalition on Community, Environment and Social Stress) was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 ES010932, U01 HL072494, R01 MD006086, and R01 HL080674; biostatistical support was funded by grants UH3 OD023337, P30 ES023515, and UL1 TR001363 and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant P30 ES000002; and PRISM (Programming of Intergenerational Stress Mechanisms) was funded by grants R01 HL095606, R01 HL114396, and R01 ES030302. B.A.C. was supported by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency grant RD-835872-01; the content of the work is the responsibility of the grantee and does not represent official views of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency does not endorse the services mentioned herein. J.L.D. and M.C.S. were funded by National Institutes of Health grant P01 AG023394 and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant P50 HL105185.

Author Contributions: R.J.W. contributed to project conception, design, supervising analyses, data interpretation, and leading the writing of the manuscript. H.-H.L.H and Y.-H.M.C. conducted analyses, participated in the interpretation of results, and contributed to the writing. B.A.C. provided statistical expertise for guiding and interpreting analytical findings and contributed to the writing. I.K. and J.S. provided NO2, particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm, and temperature exposure estimates; participated in the interpretation of results; and contributed to revisions of the manuscript. M.C.S., N.H., and J.L.D. provided the ultrafine particle estimates, participated in the interpretation of results, and contributed to the writing.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202010-3743OC on May 20, 2021

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Wright RJ, Brunst KJ. Programming of respiratory health in childhood: influence of outdoor air pollution. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25:232–239. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32835e78cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ornatowski W, Lu Q, Yegambaram M, Garcia AE, Zemskov EA, Maltepe E, et al. Complex interplay between autophagy and oxidative stress in the development of pulmonary disease. Redox Biol. 2020;36:101679. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ten VS, Ratner V. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and pulmonary dysfunction: current progress and future directions. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2020;34:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sotty J, Kluza J, De Sousa C, Tardivel M, Anthérieu S, Alleman LY, et al. Mitochondrial alterations triggered by repeated exposure to fine (PM2.5-0.18) and quasi-ultrafine (PM0.18) fractions of ambient particulate matter. Environ Int. 2020;142:105830. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dai Y, Huo X, Cheng Z, Faas MM, Xu X. Early-life exposure to widespread environmental toxicants and maternal-fetal health risk: a focus on metabolomic biomarkers. Sci Total Environ. 2020;739:139626. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu X, Zhang J, Yang X, Zhang Y, Chen Z. The role and potential pathogenic mechanism of particulate matter in childhood asthma: a review and perspective. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:8254909. doi: 10.1155/2020/8254909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bose S, Chiu YM, Hsu HL, Di Q, Rosa MJ, Lee A, et al. Prenatal nitrate exposure and childhood asthma: influence of maternal prenatal stress and fetal sex. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1396–1403. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0421OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hsu HH, Chiu YH, Coull BA, Kloog I, Schwartz J, Lee A, et al. Prenatal particulate air pollution and asthma onset in urban children: identifying sensitive windows and sex differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:1052–1059. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0658OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu W, Huang C, Cai J, Fu Q, Zou Z, Sun C, et al. Prenatal and postnatal exposures to ambient air pollutants associated with allergies and airway diseases in childhood: a retrospective observational study. Environ Int. 2020;142:105853. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yan W, Wang X, Dong T, Sun M, Zhang M, Fang K, et al. The impact of prenatal exposure to PM2.5 on childhood asthma and wheezing: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27:29280–29290. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gangwar RS, Bevan GH, Palanivel R, Das L, Rajagopalan S. Oxidative stress pathways of air pollution mediated toxicity: recent insights. Redox Biol. 2020;34:101545. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ohlwein S, Kappeler R, Kutlar Joss M, Künzli N, Hoffmann B. Health effects of ultrafine particles: a systematic literature review update of epidemiological evidence. Int J Public Health. 2019;64:547–559. doi: 10.1007/s00038-019-01202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li N, Georas S, Alexis N, Fritz P, Xia T, Williams MA, et al. A work group report on ultrafine particles (American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology): why ambient ultrafine and engineered nanoparticles should receive special attention for possible adverse health outcomes in human subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simon MC, Naumova EN, Levy JI, Brugge D, Durant JL. Ultrafine particle number concentration model for estimating retrospective and prospective long-term ambient exposures in urban neighborhoods. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54:1677–1686. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. da Costa E Oliveira JR, Base LH, de Abreu LC, Filho CF, Ferreira C, Morawska L. Ultrafine particles and children’s health: literature review. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2019;32:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lavigne E, Donelle J, Hatzopoulou M, Van Ryswyk K, van Donkelaar A, Martin RV, et al. Spatiotemporal variations in ambient ultrafine particles and the incidence of childhood asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1487–1495. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1976OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wright RJ, Coull BA. Small but mighty: prenatal ultrafine particle exposure linked to childhood asthma incidence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1448–1450. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0506ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zeger SL, Thomas D, Dominici F, Samet JM, Schwartz J, Dockery D, et al. Exposure measurement error in time-series studies of air pollution: concepts and consequences. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:419–426. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wright RJ, Hsu HHL, Chiu YHM, Coull BA, Simon MC, Hudda N, et al. Prenatal maternal ambient ultrafine particle exposure and incident childhood asthma [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:A1097. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202010-3743OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brunst KJ, Sanchez-Guerra M, Chiu YM, Wilson A, Coull BA, Kloog I, et al. Prenatal particulate matter exposure and mitochondrial dysfunction at the maternal-fetal interface: effect modification by maternal lifetime trauma and child sex. Environ Int. 2018;112:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simon MC, Hudda N, Naumova EN, Levy JI, Brugge D, Durant JL. Comparisons of traffic-related ultrafine particle number concentrations measured in two urban areas by central, residential, and mobile monitoring. Atmos Environ (1994) 2017;169:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Padró-Martínez LT, Patton AP, Trull JB, Zamore W, Brugge D, Durant JL. Mobile monitoring of particle number concentration and other traffic-related air pollutants in a near-highway neighborhood over the course of a year. Atmos Environ (1994) 2012;61:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.06.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas K, Hardy RD, Lazrus H, Mendez M, Orlove B, Rivera-Collazo I, et al. Explaining differential vulnerability to climate change: a social science review. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 2019;10:e565. doi: 10.1002/wcc.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hudda N, Simon MC, Zamore W, Durant JL. Aviation-related impacts on ultrafine particle number concentrations outside and inside residences near an airport. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:1765–1772. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hudda N, Simon MC, Zamore W, Brugge D, Durant JL. Aviation emissions impact ambient ultrafine particle concentrations in the greater Boston area. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:8514–8521. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b01815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Di Q, Amini H, Shi L, Kloog I, Silvern R, Kelly J, et al. Assessing NO2 concentration and model uncertainty with high spatiotemporal resolution across the contiguous United States using ensemble model averaging. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54:1372–1384. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kloog I, Chudnovsky AA, Just AC, Nordio F, Koutrakis P, Coull BA, et al. A New hybrid spatio-temporal model for estimating daily multi-year PM2.5 concentrations across northeastern USA using high resolution aerosol optical depth data. Atmos Environ (1994) 2014;95:581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kloog I, Nordio F, Coull BA, Schwartz J. Predicting spatiotemporal mean air temperature using MODIS satellite surface temperature measurements across the Northeastern USA. Remote Sens Environ. 2014;150:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson A, Chiu YM, Hsu HL, Wright RO, Wright RJ, Coull BA. Bayesian distributed lag interaction models to identify perinatal windows of vulnerability in children’s health. Biostatistics. 2017;18:537–552. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxx002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Textor J, van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, Liskiewicz M, Ellison GT. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ‘dagitty’. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1887–1894. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, Leaf PJ. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20:40–49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilson A, Chiu YM, Hsu HL, Wright RO, Wright RJ, Coull BA. Potential for bias when estimating critical windows for air pollution in children’s health. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:1281–1289. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laffont S, Guéry JC. Deconstructing the sex bias in allergy and autoimmunity: from sex hormones and beyond. Adv Immunol. 2019;142:35–64. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. De Martinis M, Sirufo MM, Suppa M, Di Silvestre D, Ginaldi L. Sex and gender aspects for patient stratification in allergy prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1535. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bové H, Bongaerts E, Slenders E, Bijnens EM, Saenen ND, Gyselaers W, et al. Ambient black carbon particles reach the fetal side of human placenta. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3866. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11654-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saenen ND, Martens DS, Neven KY, Alfano R, Bové H, Janssen BG, et al. Air pollution-induced placental alterations: an interplay of oxidative stress, epigenetics, and the aging phenotype? Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:124. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0688-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosa MJ, Hsu HL, Just AC, Brennan KJ, Bloomquist T, Kloog I, et al. Association between prenatal particulate air pollution exposure and telomere length in cord blood: effect modification by fetal sex. Environ Res. 2019;172:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pomatto LCD, Carney C, Shen B, Wong S, Halaszynski K, Salomon MP, et al. The mitochondrial Lon protease is required for age-specific and sex-specific adaptation to oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 2017;27:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martens DS, Cox B, Janssen BG, Clemente DBP, Gasparrini A, Vanpoucke C, et al. Prenatal air pollution and newborns’ predisposition to accelerated biological aging. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:1160–1167. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kho AT, Chhabra D, Sharma S, Qiu W, Carey VJ, Gaedigk R, et al. Age, sexual dimorphism, and disease associations in the developing human fetal lung transcriptome. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:814–821. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0326OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mujahid S, Logvinenko T, Volpe MV, Nielsen HC. miRNA regulated pathways in late stage murine lung development. BMC Dev Biol. 2013;13:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee AG, Cowell W, Kannan S, Ganguri HB, Nentin F, Wilson A, et al. Prenatal particulate air pollution and newborn telomere length: effect modification by maternal antioxidant intakes and infant sex. Environ Res. 2020;187:109707. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Novák J, Vaculovič A, Klánová J, Giesy JP, Hilscherová K. Seasonal variation of endocrine disrupting potentials of pollutant mixtures associated with various size-fractions of inhalable air particulate matter. Environ Pollut. 2020;264:114654. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hartwig IR, Bruenahl CA, Ramisch K, Keil T, Inman M, Arck PC, et al. Reduced levels of maternal progesterone during pregnancy increase the risk for allergic airway diseases in females only. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014;92:1093–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Klepac P, Locatelli I, Korošec S, Künzli N, Kukec A. Ambient air pollution and pregnancy outcomes: a comprehensive review and identification of environmental public health challenges. Environ Res. 2018;167:144–159. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Machado Júnior LC, Passini Júnior R, Rodrigues Machado Rosa I. Late prematurity: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2014;90:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lau N, Smith MJ, Sarkar A, Gao Z. Effects of low exposure to traffic related air pollution on childhood asthma onset by age 10 years. Environ Res. 2020;191:110174. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Miller SL, Facciola NA, Toohey D, Zhai J. Ultrafine and fine particulate matter inside and outside of mechanically ventilated buildings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:128. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fuller CH, Brugge D, Williams PL, Mittleman MA, Lane K, Durant JL, et al. Indoor and outdoor measurements of particle number concentration in near-highway homes. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013;23:506–512. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Baldauf RW, Devlin RB, Gehr P, Giannelli R, Hassett-Sipple B, Jung H, et al. Ultrafine particle metrics and research considerations: review of the 2015 UFP workshop. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:105413. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]