Abstract

Background

The safety of radiotherapy techniques in the treatment of vestibular schwannoma (VS) shows a high rate of tumor control with few side effects. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) may have a potential relevance to the recurrence of VS. Further research is still needed on the key genes that determine the sensitivity of VS to radiation therapy.

Materials and Methods

Transcriptional microarray data and clinical information data from VS patients were downloaded from GSE141801, and vascular-related genes associated with recurrence after radiation therapy for VS were obtained by combining information from MSigDB. Logistics regression was applied to construct a column line graph prediction model for recurrence status after radiation therapy. Pan-cancer analysis was also performed to investigate the cooccurrence of these genes in tumorigenesis.

Results

We identified eight VS recurrence-related genes from the GSE141801 dataset. All of these genes were highly expressed in the VS recurrence samples. Four collagen family genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) were further screened, and a model was constructed to predict the risk of recurrence of VS. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses revealed that these four collagen family genes play important roles in a variety of biological functions and cellular pathways. Pan-cancer analysis further revealed that the expression of these genes was significantly heterogeneous across immune phenotypes and significantly associated with immune infiltration. Finally, Neuropeptide Y (NPY) was found to be significantly and negatively correlated with the expression of COL5A1, COL3A1, and COL4A1.

Conclusions

Four collagen family genes have been identified as possible predictors of recurrence after radiation therapy for VS. Pan-cancer analysis reveals potential associations between the pathogenesis of VS and other tumorigenic factors. The relevance of NPY to VS was also revealed for the first time.

1. Introduction

Vestibular schwannoma (VS) is a benign tumor that originates from the auditory nerve sheath and accounts for 8% to 10% of intracranial tumors with a similar incidence on the left and right sides, and occasionally bilateral [1]. VS is most common in adults, 30-50 years old; however, there is no significant gender difference. The main clinical manifestations are pontocerebellar horn syndrome and increased intracranial pressure. When the size of the tumor is small, patients will experience tinnitus, hearing loss, and vertigo on one side, and a few patients will become deaf after a longer period. As the tumor continues to grow, the patient will experience facial muscle twitching, reduced lacrimal secretion, facial numbness, reduced pain and touch, a weakened corneal reflex, and other symptoms [2]. Surgery is currently the main treatment option [3]; however there are many risks associated with surgical treatment, such as cerebrospinal fluid leakage with an incidence of around 2% to 30% [4].

Surgical treatment of VS no longer focuses solely on total removal of the tumor, but instead on protecting neurological function, reducing the incidence of postoperative complications, and improving the patient's post-operative quality of life. As a result, some of the newer VS treatments include microsurgery, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSRT), and targeted drug therapy [5–8]. The choice of different treatment modalities greatly impacts prognosis, functional preservation, and long-term quality of life. This has necessitated the medical staff that treats VS to grow from a single neurosurgeon to a multidisciplinary treatment team. The SRS and FSRT technologies are new technologies born out of this multidisciplinary collaboration. With the accumulation of long-term clinical treatment data and practical experience, the safety of SRS technology for treating VS has fewer side effects and a high tumor control rate [5–8]. In conclusion, radiotherapy shows great potential advantages as an alternative to surgery, taking into account patient comfort, quality of life, cost of treatment, and avoidance of potential surgical complications (i.e., meningitis, hemorrhage, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, hearing, and neurological collateral damage).

However, 34.7% of VS patients relapsed after SRS treatment [9]. Therefore, further research is still needed on the efficacy of radiotherapy for different types of VS. [10, 11] Several studies have examined the transcriptomic profile of different types of VS, but few have systematically explored the genes associated with SRS efficacy [12–15]. Indeed, if the molecular biological features associated with VS recurrence can be identified, more precise VS treatments can be achieved. The GSE141801 dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database analyzes the transcriptomic profile of tumors between patients with VS who relapsed after radiation therapy alone and another group of patients who underwent direct surgery without radiation therapy [16].

Tumor recurrence after radiotherapy is closely related to vascular infiltration. Tumor recurrence areas have higher vascular and cell density, and vascular infiltration plays an important role in the development of tumors [17, 18]. The relationship between vascular infiltration and vestibular Schwannoma has been revealed in recent years [19, 20]. We speculate that excessive vascular infiltration may be associated with recurrence of VS after radiotherapy. Exploring angiogenic genes can help reveal the mechanism of VS recurrence.

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is a 36 amino acid peptide that is widely distributed in the central and peripheral nervous systems. NPY infiltration is a manifestation of innervated tissues and cells [21]. Neuropeptides also have an effect on vascular development, and neuropeptides such as NPY are widely distributed in the perivascular area [22, 23]. Now, upregulation of NPY has been found to be associated with abnormal vascular function [24]. We speculate that NPY may have a potential relevance to the recurrence of vestibular schwannoma by regulating vascular-related function.

In this study, we used bioinformatics analysis to obtain genes associated with VS recurrence and studied important genes associated with angiogenesis among them and NPY. Pan-cancer analysis investigated the commonality of these genes in tumorigenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Download and Preprocessing

We downloaded transcriptome microarray data and corresponding clinical data from the GSE141801 dataset for 67 patients with VS; of these, nine patients relapsed after radiation therapy and 58 patients were a first diagnosis. We transformed the microarray gene names according to the microarray platform file and then obtained the gene expression matrix. The angiogenesis-associated gene set was retrieved and downloaded from the MSigDB database (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp). 226 angiogenesis-related genes were downloaded and collated from the MSigDB database. The 33 pan-cancer transcriptome expression data, immune subtypes, tumor microenvironment score data, and clinical information data from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were downloaded from UCSC Xena (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/).

2.2. Differentially Expressed Genes

The limma package performed batch correction of gene expression on intersample microarrays and tested for differences between the postradiotherapy relapse and nonradiotherapy groups. Differential genes were filtered by FDR < 0.05 and log2FC > 1. GO and KEGG performed a pathway enrichment analysis of up- and downregulated genes in the tumor tissue, respectively.

2.3. Angiogenesis-Related Genes

We performed intersection analysis between differential genes and the set of angiogenesis-related genes. We then obtained the angiogenesis-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Heat and volcano maps were used to demonstrate the gene expression and fold change of angiogenesis-related DEGs.

2.4. Logistic Regression Model Construction for Predicting Recurrence Rates after Radiation Therapy

Univariate and multifactorial logistic regression analyses were used for the analysis of angiogenesis-related DEGs and clinical characteristics. The filtering criterion of risk factors for recurrence after radiotherapy was P < 0.1, and risk factors were then screened for use in constructing logistic regression models. Next, we further constructed a nomogram to calculate the probability of recurrence after radiotherapy in VS patients for ease of use in the clinic.

2.5. Clinical Predictive Model Validation

The Caret package was used to split the entire dataset into training and test groups by 7 : 3. The model was trained in the training group and then validated in the test group. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and C-index were used to assess the predictive classification ability of the model in the training group, the overall cohort, and the test group. C-indices between 0.7 and 1.0 represented good predictive performance of the model. A calibration curve was also produced to assess the calibration of the model. Finally, decision curves were used to assess the net benefit at different probability thresholds and also to assess the clinical usability and safety of the nomogram and the model.

2.6. Pan-Cancer Analysis

We performed a pan-cancer analysis of the genes included in the model in the TCGA database. First, we performed differential gene expression analysis of the included genes in pan-cancerous and corresponding paracancerous tissues. Correlation with heat maps was used to demonstrate the relationship between incorporated gene expressions in pan-cancerous tissues. Cox proportional regression models divided tumor patients into the high- and low-expression groups by median gene expression, and the KM method was then used to perform survival curve mapping. Finally, the relationship between genes incorporated into the model, immune-related features, and tumor microenvironment scores were further analyzed.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistics were plotted using R software (version 4.0.5). All statistical defaults were bilateral, while P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The ROCR package was used to plot ROC curves; the Hmisc package was used to calculate the C-index. The rms package was used for plotting the nomograms and calibration curves. The rmda package was used to plot the decision curve analysis (DCA) curves.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Differences between the Recurrence Group and the First Diagnosis Group after Radiotherapy

The research flow chart is shown in Figure 1. The results of the differential analysis of gene expression in both groups of patients were saved in Supplementary table 1, and a total of 265 DEGs were obtained. GO and KEGG functional pathway analysis results are presented in a bar chart (Supplementary Figure 1), and Table 1 shows the top 10 up- and downregulated pathways in KEGG.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the analysis process. ARGS: angiogenesis-related genes; DEGs: differentially expressed genes; TME: tumor microenvironment.

Table 1.

Up- and downregulated pathways in KEGG.

| Description | Adjust P value | geneID | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up | Nicotine addiction | P < 0.001 | GRIA1/CACNA1A/GRIA4/GABRA1/GRIA2/GABRD |

| Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling | P < 0.001 | ADCY2/GNG4/GRIA1/CACNA1A/GRIA4/GABRA1/GRIA2/ADCY1/GABRD | |

| GABAergic synapse | P < 0.001 | ADCY2/GNG4/CACNA1A/GABBR2/GABRA1/ADCY1/GABRD | |

| Morphine addiction | P < 0.001 | ADCY2/GNG4/CACNA1A/GABBR2/GABRA1/ADCY1/GABRD | |

| Circadian entrainment | P < 0.001 | ADCY2/GNG4/GRIA1/RYR3/GRIA4/GRIA2/ADCY1 | |

| Glutamatergic synapse | P < 0.001 | ADCY2/GNG4/GRIA1/CACNA1A/GRIA4/GRIA2/ADCY1 | |

| cAMP signaling pathway | 0.001 | ADCY2/GRIA1/SOX9/ATP1B1/GABBR2/GRIA4/PPP1R1B/GRIA2/ADCY1 | |

| Insulin secretion | 0.001 | ADCY2/ATP1B1/KCNN3/SNAP25/PCLO/ADCY1 | |

| Adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes | 0.003 | ADCY2/PPP1R1A/ATP1B1/TNNC1/AGT/ADCY1/SCN4B | |

| Synaptic vesicle cycle | 0.006 | CACNA1A/SYT1/CPLX1/SNAP25/ATP6V1G2 | |

| Down | ECM-receptor interaction | P < 0.001 | COL4A2/COL4A1/ITGA2/ITGB4/COL1A2/LAMB1/LAMA2/FREM2/FRAS1 |

| Protein digestion and absorption | P < 0.001 | COL4A2/COL4A1/COL1A2/COL5A1/COL28A1/COL3A1/COL15A1 | |

| Focal adhesion | P < 0.001 | COL4A2/COL4A1/BIRC3/ITGA2/ITGB4/COL1A2/LAMB1/LAMA2 | |

| Small cell lung cancer | P < 0.001 | COL4A2/COL4A1/BIRC3/ITGA2/LAMB1/LAMA2 | |

| Amoebiasis | P < 0.001 | COL4A2/COL4A1/COL1A2/LAMB1/LAMA2/COL3A1 | |

| Human papillomavirus infection | P < 0.001 | COL4A2/COL4A1/ITGA2/ITGB4/COL1A2/LAMB1/LAMA2/FZD8 | |

| AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | P < 0.001 | COL4A2/COL4A1/TGFBR2/COL1A2/COL3A1 | |

| PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | P < 0.001 | COL4A2/COL4A1/ITGA2/ITGB4/COL1A2/LAMB1/LAMA2/ERBB3 | |

| Relaxin signaling pathway | 0.002 | COL4A2/COL4A1/TGFBR2/COL1A2/COL3A1 | |

| Proteoglycans in cancer | 0.012 | ITGA2/RRAS/COL1A2/ERBB3/FZD8 |

3.2. Angiogenesis-Related DEGs

Venn diagrams and volcano plots (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)) showed that the eight DEGs were also angiogenesis-related genes. All eight of these DEGs were highly expressed in the recurrence group after radiation therapy. Table 2 shows the analysis of variance for these eight DEGs, and the heat map (Figure 2(c)) shows their expression of in tumor tissue and their relationship with clinical traits. These results suggest that the high expression of these eight DEGs is associated with recurrence after radiation therapy.

Figure 2.

Results of differential and intersection analysis. (a) Venn diagram showing eight genes after taking intersection of DEGs and ARGs. (b) Volcano diagram showing differential and intersection genes. (c) Heat map showing expression of intersecting genes in tumor tissue and relationship to clinical traits.

Table 2.

Eight different expression genes.

| Id | logFC | t | P value | Adjust P value | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL4A1 | -1.30 | -5.30 | 1.42E − 06 | 1.00E − 03 | 5.11 |

| STARD13 | -1.25 | -4.66 | 1.54E − 05 | 2.64E − 03 | 2.91 |

| TGFBR2 | -1.01 | -4.38 | 4.34E − 05 | 3.81E − 03 | 1.97 |

| COL1A2 | -1.38 | -4.29 | 5.95E − 05 | 4.18E − 03 | 1.68 |

| COL5A1 | -1.10 | -4.25 | 6.69E − 05 | 4.40E − 03 | 1.57 |

| PLA2G4A | -1.26 | -3.62 | 5.72E − 04 | 1.15E − 02 | -0.37 |

| COL3A1 | -1.34 | -3.05 | 3.28E − 03 | 3.24E − 02 | -1.93 |

| COL15A1 | -1.19 | -2.97 | 4.12E − 03 | 3.73E − 02 | -2.13 |

3.3. Single- and Multifactor Logistic Regression Analysis

All characteristics were included for single- and multifactor logistic regression analyses (Table 3). Seven genes (COL4A1, STARD13, COL5A1, PLA2G4A, COL3A1, COL15A1, and TGFBR2) were filtered for multivariate analysis at P < 0.1, and the final four collagen family genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) were retained for further analysis.

Table 3.

Uni- and multilogistics regression analyses for recurrence after radiation.

| Variables | Unilogistics regression | Multilogistics regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | β | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| COL4A1 | -3.485 | 0.031 (0.001-0.309) | 0.012 | -6.812 | 0.001 (0-0.258) | 0.065 |

| STARD13 | -1.355 | 0.258 (0.07-0.579) | 0.008 | 0.613 | 1.847 (0.141-114.581) | 0.670 |

| TGFBR2 | -2.171 | 0.114 (0.009-0.531) | 0.052 | -6.969 | 0.001 (0-1.695) | 0.177 |

| COL1A2 | -1.773 | 0.17 (0.008-0.703) | 0.198 | |||

| COL5A1 | -1.682 | 0.186 (0.025-0.593) | 0.043 | -10.102 | 0 (0-0.066) | 0.045 |

| PLA2G4A | -0.870 | 0.419 (0.193-0.758) | 0.010 | -0.365 | 0.694 (0.046-9.363) | 0.766 |

| COL3A1 | -0.551 | 0.577 (0.281-0.903) | 0.037 | 4.460 | 86.455 (3.837-16515.578) | 0.020 |

| COL15A1 | -0.627 | 0.534 (0.282-0.884) | 0.025 | 3.490 | 32.775 (2.271-5105.412) | 0.058 |

| Tumor_subtype (CYS) | ||||||

| NF2 | 0.731 | 2.077 (0.223-45.81) | 0.553 | |||

| SPO | 0.223 | 1.25 (0.171-25.518) | 0.847 | |||

Note: β is the regression coefficient.

3.4. Construction and Evaluation of the Logistics Regression Model

COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1 were included for logistic regression model construction. The weights and statistical differences of the included factors in the constructed logistics regression model are shown in Table 4. A nomogram was used to calculate the likelihood of recurrence after radiotherapy according to a logistics regression model (Figure 3(a)), and a calibration graph evaluated the calibration of the fit of the model predictions and the actual classification (Figure 3(b)). Figure 4(a) shows the ROC curves and area under the curve (AUC) values for the model in the training set, test set, and overall cohort, respectively (training set: 0.964, validation set: 0.889, and entire cohort: 0.941). Table 5 shows the C-index for the three groups and ranges from 0.889-0.964, indicating that this model had good predictive classification efficacy. The DCA curve demonstrated that the model had a good range of reliability and safety in clinical prediction (Figure 4(b)). These results above show that the model has excellent predictive power. Therefore, the four collagen family genes were further screened by combining the clinical information provided from the database with the results of univariate and multivariate logistic analyses and were used to construct a prediction model for the risk of recurrence of VS.

Table 4.

Prediction factors for recurrence after radiation.

| Variables | Prediction model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| (intercept) | 48.356 | 1.00E + 21 (6.21E + 08 − 1.49E + 42) | 0.011 |

| COL5A1 | -5.393 | 0.005 (0-0.429) | 0.042 |

| COL3A1 | 3.812 | 45.238 (3.515-1849.766) | 0.014 |

| COL4A1 | -6.648 | 0.001 (0-0.068) | 0.007 |

| COL15A1 | 1.525 | 4.596 (0.933-42.261) | 0.098 |

Note: β is the regression coefficient.

Figure 3.

(a) Nomogram showing the column line graph prediction model for recurrence after radiotherapy. (b) Calibration graph showing the calibration of the prediction model.

Figure 4.

(a) ROC curves showing the classification and predictive efficacy of the predictive model. (b) DCA curves showing the range of clinical predictive safety.

Table 5.

C-index of the nomogram prediction model.

| Dataset group | C-index of the prediction model | |

|---|---|---|

| C-index | The C-index (95% CI) | |

| Training set | 0.964 | 0.908-1 |

| Validation set | 0.889 | 0.707-1 |

| Entire cohort | 0.941 | 0.878-1 |

3.5. Pan-Cancer Analysis

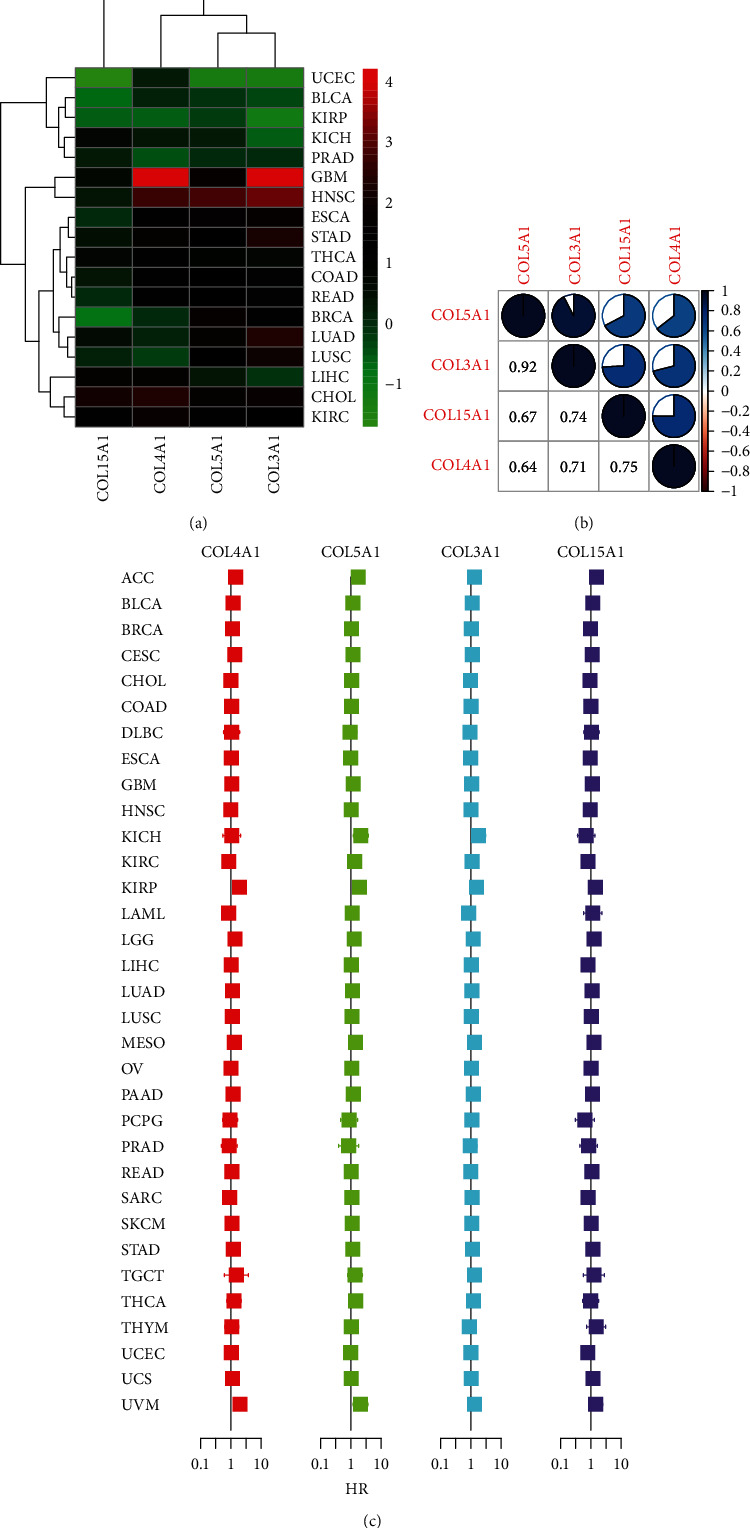

We further explored the expression of these four genes in pan-cancer and their role in the tumor microenvironment. Figures 5(a)–5(d) show that these four genes were relatively highly expressed in pan-cancerous tissues compared to their paracancerous counterparts. Figure 6(a) shows how the expression of these four genes was relatively high in GBM, HNSC, STAD, LUAD, and CHOL and relatively low in UCEC, BLCA, KIRP, and PRAD, and Figure 6(b) shows the positive correlation between the expressions of these four genes in the pan-cancerous tissue.

Figure 5.

Box plot showing the expression of the four genes in the pan-cancerous tissue and its paracancerous tissues.

Figure 6.

(a) Heat map showing the expression of the four genes in pan-cancerous tumor tissue. (b) Correlation heat map showing the correlation results of the expression of the four genes in pan-cancerous tissue. (c) Cox analysis showing the results of the four genes in pan-cancerous survival analysis. Intersection with the midline represents no statistical significance.

3.6. Survival Analysis

We applied the KM method and Cox proportional regression models to the survival analysis of four genes in pan-cancer. Figure 6(c) shows the results of applying cox regression analysis to the four genes in the pan-cancer. The HR and significance results of these four genes for pan-cancer were shown in Figure 6(c). Figure 7 shows the statistically significant differences in the survival analysis of these four genes in MESO, KIRP, and LGG (P < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Survival curves showing the results of four genes in MESO, KIRP, and LGG (KM method).

3.7. Immune Subtypes and the Tumor Microenvironment

We performed differential analysis and correlation analysis of these four genes and tumor immune subtypes with tumor microenvironment scores. In these 33 cancers, these four genes differed significantly in the six tumor immune subtypes (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, and C6) (P < 0.05), Figure 8(a)). These four genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) and the stromal, immune, and total scores in the tumor microenvironment were significantly correlated in most tumors (Figures 8(b)–8(d)).

Figure 8.

The results of the analysis of variance and correlation analysis demonstrate the relationship between the four genes and (a) the tumor immune subtype and (b–d) the tumor microenvironment score. Blanks in the heat map represent no statistically significant differences in correlation analysis.

3.8. Correlation of NPY with Collagen Family Genes and Vestibular Schwannoma Recurrence after Radiotherapy

Four collagen family genes (COL3A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, and COL15A1) were significantly positively correlated with each other (Figure 9(a)). Low expression of COL4A1 and COL5A1 was associated with recurrence of vestibular schwannoma, while high expression of NPY was associated with recurrence of vestibular schwannoma (Table 6). In addition, these genes were not significantly associated with age and sex (Figures 9(b) and 9(c)). These results suggest that NPY is significantly associated with four collagen family genes (COL3A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, and COL15A1) and recurrence after radiotherapy for vestibular schwannoma.

Figure 9.

Correlation of NPY with collagen family genes and tumor recurrence after radiotherapy. Correlation analysis of NPY, COL3A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, and COL15A1 with each other (a). Differential expression of these genes (NPY, COL3A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, and COL15A1) in different ages and genders.

Table 6.

The basic characteristics of the patients.

| Characteristic | First diagnosis | Relapsed | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 58 | 9 | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.888 | ||

| 9 (13.4%) | 1 (1.5%) | ||

| Female | 20 (29.9%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Male | 29 (43.3%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Age, n (%) | 1.000 | ||

| 9 (13.4%) | 1 (1.5%) | ||

| <40 year | 26 (38.8%) | 4 (6%) | |

| >40 year | 23 (34.3%) | 4 (6%) | |

| COL3A1, median (IQR) | 8.91 (8.61, 9.31) | 8.92 (8.35, 9.48) | 0.720 |

| COL4A1, median (IQR) | 8.4 (8.09, 8.68) | 7.9 (7.44, 8.1) | <0.001 |

| COL5A1, median (IQR) | 8.42 (8.15, 8.71) | 8.13 (7.66, 8.16) | 0.009 |

| COL15A1, median (IQR) | 8.81 (8.24, 9.22) | 8.56 (7.72, 8.66) | 0.108 |

| NPY, median (IQR) | 2.38 (2.27, 2.52) | 2.63 (2.51, 2.66) | 0.005 |

4. Discussion

In this study, genes associated with VS recurrence were obtained using bioinformatics analysis. To investigate the role of angiogenic genes in this process, we obtained a collection of angiogenesis-related genes at MSigDB and intersected them with differentially expressed genes from the GSE141801 dataset. Eight genes were obtained for univariate and multifactorial logistic analyses, and four genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) were screened. A column line graph prediction model was constructed by applying logistic regression to predict the recurrence status after radiation therapy. To further investigate the commonality of these genes in tumorigenesis, pan-cancer analysis was used to explore the role of these four target genes in tumor development. Finally, the relevance of NPY to vestibular schwannoma was also revealed for the first time.

We identified eight genes from the GSE141801 dataset that were highly expressed in the VS recurrence samples (including: COL15A1, COL4A1, COL1A2, COL5A1, COL3A1, STARD13, TGFBR2, and PLA2G4A). Four collagen family genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) were further screened by combining the clinical information provided by the database with the results of univariate and multifactorial logistic analyses, and a prediction model for the risk of recurrence of VS was constructed accordingly. These four collagen family genes were found to be highly expressed in most tumor tissues. There was significant heterogeneity in the expression of these genes in different immunophenotypes. We assessed the association of these four collagen family genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) with immune infiltration using three scoring systems (including: ESTIMATEScore, StromalScore, and StromalScore). With the exception of ACC, LAML, and SARC, all of these genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) were found to be significantly associated with immune infiltration. KEGG and GO enrichment analyses revealed that these four collagen family genes played important roles in a variety of biological functions and cellular pathways. Furthermore, NPY was found significantly associated with four collagen family genes (COL3A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, and COL15A1) and recurrence after radiotherapy for VS.

M2-type macrophages in VS are associated with angiogenesis and tumor growth [25]. Collagen cleavage leads to increased macrophage adhesion and promotes macrophage infiltration. [26] The expression of three collagen family genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, and COL4A1) was negatively correlated with the expression of NPY, which was found to promote the migration of macrophages in collagen in vitro [27]. The crosstalk between collagen production and radiotherapy has been studied extensively [16, 17]. We have revealed an important function of these four collagen family genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) in VS, and their high expression may be associated with VS radiotherapy recurrence. Mutations in COL3A1 are associated with the development of mesothelioma. [28] High expression of COL4A1 is associated with poor prognosis in renal papillary cell carcinoma [29]. In lower-grade glioma, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL5A1 are associated with patient prognosis and tumor progression [30, 31]. Also, the prognosis of mesothelioma is associated with COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1. In addition, COL3A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, and COL15A1 are associated with immune infiltration in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, breast cancer, mesothelioma, and other tumors [32–35]. We performed differential analysis and correlation analysis of these four genes (COL3A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, and COL15A1) and tumor immune subtypes with tumor microenvironment scores. Our results are consistent with previous studies, showing that these four genes and the stromal scores, immune scores, and total scores in the tumor microenvironment are significantly correlated in most tumors. We used bioinformatics analysis to obtain genes associated with VS recurrence and vascularity, and the pan-cancer analysis allowed the commonality of these genes in tumorigenesis to be studied. Therefore, our database-based pan-cancer analysis suggests that these four collagen family genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) have commonality with the progression of various tumors.

Low expression of COL4A1 and COL5A1 was associated with recurrence of vestibular schwannoma; while high expression of NPY was associated with recurrence of vestibular schwannoma. NPY was found to promote the migration of macrophages in collagen in vitro [27]. Recent studies have shown that these four collagen family genes (COL3A1, COL4A1, COL5A1, and COL15A1) are regulated by macrophages [27, 36, 37]. We speculate that NPY may influence VS angiogenesis by affecting macrophages to regulate the expression of COL5A1, COL3A1, and COL4A1. This hypothesis needs to be tested by further studies.

There are various methods of staging for VS. Among them, Koos grading method should be used in the future. According to the size of the tumor, VS can be classified into 4 grades. In grade 1, tumor is confined to the internal auditory tract; in grade 2, tumor invades the pontocerebellar horn, diameter ≤ 2 cm; in grade 3, tumor occupies the pontocerebellar horn pool without brainstem displacement, ≤3 cm; and in grade 4, huge tumor, >3 cm, with brainstem displacement. And the specific mechanisms by which these four collagen family genes are associated with recurrence after radiation therapy for VS remains unstudied. In the future, VS-related single-cell RNA-seq would validate our findings. Second, the association of these four collagen family genes with NPY has not been elucidated. Third, more cellular and animal experiments need to be performed to further explore the mechanisms involved. In addition, we have only focused on the expression abundance of these genes; consequently, gene polymorphisms also need to be explored. Third, all the data are from the database and we will need sufficient specimens from the clinic in the future to verify this conclusion. In addition, patients who have not relapsed after radiotherapy should be selected as controls versus those who have relapsed after radiotherapy, which will improve the scientific validity of future studies. Therefore, future cohort studies and controlled population-based pathology studies are necessary.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the expression of four angiogenesis-related collagen family genes (COL5A1, COL3A1, COL4A1, and COL15A1) was a predictor of recurrence after radiation therapy for VS. Pan-cancer analysis also revealed their potential correlation with the progression of other tumors, revealing an association between the pathogenesis of VS and other tumorigenic factors. And the relevance of NPY to VS was also revealed for the first time.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the HwaMei Hospital.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

Adrenocortical carcinoma

- BLCA:

Bladder urothelial carcinoma

- BRCA:

Breast invasive carcinoma

- CESC:

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- CHOL:

Cholangiocarcinoma

- COAD:

Colon adenocarcinoma

- DEGs:

Differentially expressed genes

- DLBC:

Lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- ESCA:

Esophageal carcinoma

- FSRT:

Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy

- GBM:

Glioblastoma multiforme

- GEO:

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GO:

Gene Ontology

- LGG:

Brain lower-grade glioma

- HNSC:

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- KEGG:

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- KICH:

Kidney chromophobe

- KIRC:

Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

- KIRP:

Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma

- KM:

Kaplan-Meier

- LAML:

Acute myeloid leukemia

- LIHC:

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- LUAD:

Lung adenocarcinoma

- LUSC:

Lung squamous cell carcinoma

- MESO:

Mesothelioma

- NPY:

Neuropeptide Y

- OV:

Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma

- PAAD:

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- PCPG:

Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma

- PRAD:

Prostate adenocarcinoma

- READ:

Rectum adenocarcinoma

- ROC:

Receiver operating characteristic

- SARC:

Sarcoma

- SKCM:

Skin cutaneous melanoma

- SRS:

Stereotactic radiosurgery

- STAD:

Stomach adenocarcinoma

- TCGA:

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TGCT:

Testicular germ cell tumors

- THCA:

Thyroid carcinoma

- THYM:

Thymoma

- UCEC:

Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

- UCS:

Uterine carcinosarcoma

- UVM:

Uveal melanoma

- VS:

Vestibular schwannoma.

Data Availability

Readers may contact the corresponding author to obtain the original data if desired.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Qingyuan Shi1 and Xiaojun Yan contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: GEO database differential analysis of GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. Supplementary Table 1: the results of the differential analysis of gene expression in both groups of patients.

References

- 1.Adib S. D., Ebner F. H., Bornemann A., Hempel J. M., Tatagiba M. Surgical management of primary cerebellopontine angle melanocytoma: outcome, recurrence and additional therapeutic options. World Neurosurgery . 2019;128:e835–e840. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halliday J., Rutherford S. A., McCabe M. G., Evans D. G. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of vestibular schwannoma. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics . 2018;18(1):29–39. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2018.1399795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aihara N., Yamada H., Takahashi M., Inagaki A., Murakami S., Mase M. Postoperative headache after undergoing acoustic neuroma surgery via the retrosigmoid approach. Neurologia Medico-Chirurgica (Tokyo) . 2017;57(12):634–640. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2017-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishman A. J., Marrinan M. S., Golfinos J. G., Cohen N. L., Roland J. T., Jr. Prevention and management of cerebrospinal fluid leak following vestibular schwannoma surgery. The Laryngoscope . 2004;114(3):501–505. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200403000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hani U., Bakhshi S., Shamim M. S. Steriotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association . 2020;70(5):939–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arthurs B. J., Lamoreaux W. T., Mackay A. R., et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: tumor control and functional preservation in 70 patients. American Journal of Clinical Oncology . 2011;34(3):265–269. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181dbc2ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foote K. D., Friedman W. A., Buatti J. M., Meeks S. L., Bova F. J., Kubilis P. S. Analysis of risk factors associated with radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma. Journal of Neurosurgery . 2001;95(3):440–449. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.3.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rykaczewski B., Zabek M. A meta-analysis of treatment of vestibular schwannoma using gamma knife radiosurgery. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). . 2014;18(1):60–66. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.39840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abouzari M., Goshtasbi K., Sarna B., et al. Prediction of vestibular schwannoma recurrence using artificial neural network. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. . 2020;5(2):278–285. doi: 10.1002/lio2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leksell L. The stereotaxic method and radiosurgery of the brain. Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica . 1951;102(4):316–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailo M., Boari N., Franzin A., et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery as primary treatment for large vestibular schwannomas: clinical results at long-term follow-up in a series of 59 patients. World Neurosurgery . 2016;95:487–501. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Przybylowski C. J., Baranoski J. F., Paisan G. M., et al. CyberKnife radiosurgery for acoustic neuromas: Tumor control and clinical outcomes. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience . 2019;63:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2019.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flickinger J. C., Lunsford L. D., Linskey M. E., Duma C. M., Kondziolka D. Gamma knife radiosurgery for acoustic tumors: multivariate analysis of four year results. Radiotherapy and Oncology . 1993;27(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90127-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowe J. G., Radatz M. W., Walton L., Hampshire A., Seaman S., Kemeny A. A. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery for unilateral acoustic neuromas. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry . 2003;74(11):1536–1542. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu C. H., Chen C. M., Cheng P. W., Young Y. H. Acute sensorineural hearing loss in patients with vestibular schwannoma early after cyberknife radiosurgery. Journal of the Neurological Sciences . 2019;399:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gugel I., Ebner F. H., Grimm F., et al. Contribution of mTOR and PTEN to radioresistance in sporadic and NF2-associated vestibular schwannomas: a microarray and pathway analysis. Cancers (Basel) . 2020;12(1):p. 177. doi: 10.3390/cancers12010177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarosz-Biej M., Smolarczyk R., Cichoń T., Kułach N. Tumor microenvironment as a "game changer" in cancer radiotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2019;20(13):p. 3212. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarco N., Norton E., Quiñones-Hinojosa A., Guerrero-Cázares H. Overlapping migratory mechanisms between neural progenitor cells and brain tumor stem cells. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences . 2019;76(18):3553–3570. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson L. B., Jorgensen L. N., Adawi D., et al. The effect of preoperative radiotherapy on systemic collagen deposition and postoperative infective complications in rectal cancer patients. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum . 2005;48(8):1573–1580. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straub J. M., New J., Hamilton C. D., Lominska C., Shnayder Y., Thomas S. M. Radiation-induced fibrosis: mechanisms and implications for therapy. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology . 2015;141(11):1985–1994. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-1974-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams R. M., Singh J., Sharkey K. A. Innervation and mast cells of the rat exorbital lacrimal gland: the effects of age. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System . 1994;47(1-2):95–108. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connat J. L., Busseuil D., Gambert S., et al. Modification of the rat aortic wall during ageing; possible relation with decrease of peptidergic innervation. Anat Embryol (Berl). . 2001;204(6):455–468. doi: 10.1007/s429-001-8002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barr-Agholme M., Modéer T., Luthman J. Immunohistological study of neuronal markers in inflamed gingiva obtained from children with Down's syndrome. Journal of Clinical Periodontology . 1991;18(8):624–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1991.tb00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi B., Shin M. K., Kim E. Y., et al. Elevated neuropeptide Y in endothelial dysfunction promotes macrophage infiltration and smooth muscle foam cell formation. Frontiers in Immunology . 2019;10:p. 1701. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu W., Peng S., Shi Y., Li L., Song Z., Lin S. NPY promotes macrophage migration by upregulating matrix metalloproteinase-8 expression. Journal of Cellular Physiology . 2021;236(3):1903–1912. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazur A., Holthoff E., Vadali S., Kelly T., Post S. R. Cleavage of type I collagen by fibroblast activation protein-α enhances class A scavenger receptor mediated macrophage adhesion. PLoS One . 2016;11(3, article e0150287) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu W. Q., Peng S., Wan X. Q., Lin S., Li L. Y., Song Z. Y. Physical exercise inhibits atherosclerosis development by regulating the expression of neuropeptide Y in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Life sciences . 2019;237:p. 116896. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pagano M., Ceresoli L. G., Zucali P. A., et al. Mutational profile of malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) in the phase II RAMES study. Cancers (Basel). . 2020;12(10):p. 2948. doi: 10.3390/cancers12102948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F., Guo P., Dong K., Guo P., Wang H., Lv X. Identification of key biomarkers and potential molecular mechanisms in renal cell carcinoma by bioinformatics analysis. Journal of Computational Biology . 2019;26(11):1278–1295. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2019.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Y., He J., Guo Y., Tao H., Pu F., Li Y. Identification of genes related to low-grade glioma progression and prognosis based on integrated transcriptome analysis. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry . 2020;121(5-6):3099–3111. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng T., Gong Y. Z., Wang X. K., et al. Use of genome-scale integrated analysis to identify key genes and potential molecular mechanisms in recurrence of lower-grade brain glioma. Medical Science Monitor . 2019;25:3716–3727. doi: 10.12659/MSM.913602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y., Li Z. Y., Zhou G. Q., Sun Y. An immune-related gene prognostic index for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research . 2021;27(1):330–341. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu P., Yan F., Zhao Y., et al. Green tea polyphenol EGCG attenuates MDSCs-mediated immunosuppression through canonical and non-canonical pathways in a 4T1 murine breast cancer model. Nutrients . 2020;12(4):p. 1042. doi: 10.3390/nu12041042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H., Yang M., Wang Q., Song F., Li X., Chen K. The new identified biomarkers determine sensitivity to immune check-point blockade therapies in melanoma. Oncoimmunology. . 2019;8(8):p. 1608132. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1608132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox B., Tsamou M., Vrijens K., et al. A co-expression analysis of the placental transcriptome in association with maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and newborn birth weight. Frontiers in Genetics . 2019;10:p. 354. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witherel C. E., Sao K., Brisson B. K., et al. Regulation of extracellular matrix assembly and structure by hybrid M1/M2 macrophages. Biomaterials . 2021;269:p. 120667. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simões F. C., Cahill T. J., Kenyon A., et al. Macrophages directly contribute collagen to scar formation during zebrafish heart regeneration and mouse heart repair. Nature Communications . 2020;11(1):p. 600. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14263-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: GEO database differential analysis of GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. Supplementary Table 1: the results of the differential analysis of gene expression in both groups of patients.

Data Availability Statement

Readers may contact the corresponding author to obtain the original data if desired.