Abstract

Barrier epithelial cells lining the mucosal surfaces of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts interface directly with the environment. As such, these tissues are continuously challenged to maintain a healthy equilibrium between immunity and tolerance against environmental toxins, food components, and microbes. An extracellular mucus barrier, produced and secreted by the underlying epithelium plays a central role in this host defense response. Several dedicated molecules with a unique tissue-specific expression in mucosal epithelia govern mucosal homeostasis. Here, we review the biology of Inositol-requiring enzyme 1β (IRE1β), an ER-resident endonuclease and paralogue of the most evolutionarily conserved ER stress sensor IRE1α. IRE1β arose through gene duplication in early vertebrates and adopted functions unique from IRE1α which appear to underlie the basic development and physiology of mucosal tissues.

Introduction

One third of the cellular proteome enters the secretory pathway and matures in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).1 Consequently, tight ER quality control measures are required to ensure that nascent polypeptide chains are properly folded and processed for secretion. When the ER is unable to meet the folding demands, misfolded proteins accumulate causing ER stress. To deal with this, cells induce an unfolded protein response (UPR) to slow translation, expand the ER, upregulate chaperones to aid in folding, and amplify the capacity to process misfolded proteins for degradation. The initial aim of the UPR is to restore proteostasis. If the cell is unable to resolve folding stress, the UPR transitions from an adaptive (survival) response to a terminal response that signals for cell death.2

In mammals and other metazoans, the UPR is orchestrated by three ER transmembrane proteins: Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1 (IRE1), PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), and Activating Transcription Factor 6 (ATF6). These UPR sensors detect imbalances in the folding demand and capacity of the ER via their luminal sensing domains, and activate cytoplasmic signaling cascades with transcriptional and translational outputs that mediate the UPR.3

The IRE1 branch is the most evolutionarily conserved UPR pathway in metazoans and the only UPR pathway in yeast. IRE1 contains a luminal stress-sensing domain, a single pass transmembrane domain, and cytosolic kinase and endonuclease domains (Fig. 1). In the absence of ER stress, IRE1 is retained in an inactive state.4 Upon activation by ER stress, the IRE1-endonuclease domain catalyzes an unusual splicing event in the mRNA transcript encoding X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1).5 This leads to the translation of a spliced isoform, XBP1s, which functions as a key transcription factor mediating the UPR. In addition, IRE1 can degrade other mRNA species in a process termed regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD).6,7 Both IRE1-mediated XBP1 splicing and RIDD endonuclease activities may functionally contribute to maintaining and restoring normal proteostasis.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of yeast IRE1 and human IRE1α and IRE1β.

All three IRE1 proteins share a similar overall structure, containing a luminal sensor domain, a transmembrane (TM) and juxtamembrane (JM) domain and the cytoplasmic enzymatic kinase and endonuclease domains. Numbers indicate % identity to the corresponding domain of human IRE1β.

Mammals express two IRE1 paralogues: IRE1α (gene name ERN1) and Inositol-requiring enzyme 1β (IRE1β) (gene name ERN2).8,9 IRE1α functions as a ubiquitous ER stress sensor and mediator of the UPR, and the IRE1α-XBP1 signaling pathway is comparatively well understood (although by no means complete, see also recent reviews.2,4,10–12) The function of IRE1β, on the other hand, remains largely enigmatic. The expression of IRE1β is restricted to epithelial cells lining mucosal surfaces, such as the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts,13,14 and the function of IRE1β appears to be distinct from IRE1α. This poses the questions of when and how these paralogues diverged, how their functions now relate to one another, and why IRE1β function is restricted to mucosal surfaces. Mucosal epithelia are highly specialized tissues that serve as barriers between the host and the environment, and the emergence of a second IRE1 isoform specifically in these tissues suggests a role for IRE1β in how the epithelium interfaces with the outside world. This review focuses on the physiologic role, cellular function, and evolution of IRE1β in mucosal homeostasis.

Physiologic role of IRE1β in mucosal homeostasis

Within the gastrointestinal epithelium of mice, Ern2 mRNA, and IRE1β protein are detected throughout the gastrointestinal tract, with highest levels observed in the colon and stomach.14,15 Expression is enriched specifically in the epithelial fraction of the colon, as assessed by isolation of epithelial cells released from the mucosa by EDTA-treatment of colon tissue.15 Single cell analysis of the murine small intestine epithelium reveals that Ern2 transcripts are predominantly expressed in goblet cells (Fig. 2), reaching expression levels that are up to 50-fold higher than those of Ern1.16,17 This was confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy on cryosections of mouse colon revealing specific staining of IRE1β in goblet cells, but not in absorptive cell types.14 The predominant expression of IRE1β in goblet cells might be linked to the presence of an expanded ER compared to other cell types. Yet, IRE1α is not enriched to the same extent as IRE1β suggesting a specific role for IRE1β in goblet cell function.16

Fig. 2. IRE1β is enriched in mucus-secreting cells in the gastrointestinal tract and airways.

Representation of ERN2 expression levels based on available single cell datasets. Red indicates detection of high expression levels, blue indicates absence of expression. Top panel (airways). ERN2 transcript is readily detected in goblet cells and club cells of the large and small airways, and weakly detected in ciliated cells.31 Bottom panel (intestinal tract). ERN2 transcript is mostly detected in goblet cells, with additional (lower) expression reported in Paneth, and enteroendocrine cells.16

Goblet cells are specialized secretory cells that produce mucin glycoproteins, the main component of the mucus layers protecting the epithelium from environmental factors.18 The in vivo data on the Ern2−/− mice are consistent with a role for IRE1β in goblet cell homeostasis and mucin biosynthesis. The ileum of Ern2−/− mice contains fewer MUC2+ cells compared to wild type controls,19 MUC2 being a hallmark for goblet cells. Whether this is due to a block in goblet cell differentiation, a block in MUC2 production (hence loss of MUC2 as assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis) or a defect in goblet cell survival remains as yet unclear. The reduction in the number of MUC2+ cells in the ileum of Ern2−/− mice is similar, to some extent, to mice with intestine-specific deletion of Xbp1, suggesting that IRE1β may function through XBP1 in goblet cells.19 Another study revealed that loss of IRE1β results in accumulation of misfolded MUC2 precursor proteins in the ER of immature goblet cells (i.e., secretory progenitor cells). The defect in MUC2 maturation and its retention in the ER led to marked ER abnormalities and signs of ER stress in secretory progenitor cells, located at the base of the crypt.14 Mechanistically, loss of IRE1β leads to a stabilization of Muc2 mRNA and the authors postulated that degradation of excess Muc2 mRNA by IRE1β endonuclease activity is essential to ensure proper mucus homeostasis. Interestingly, both Tsuru et al. and Tschurtschenthaler et al. showed that these defects were specific for Ern2−/− mice and were not observed in mice with intestine-specific deletion of Ern1,14,19 suggesting that IRE1β is serving a unique role in goblet cells that is not fulfilled by IRE1α. Notably, several studies have demonstrated that goblet cells are not a functionally homogeneous population throughout the gastrointestinal tract (for example sentinel goblet cells located at the top of the colon crypts20 or goblet cells forming goblet cell-associated antigen passages or GAPs in the small intestine.21) It is currently unknown whether IRE1β performs similar functions in all goblet cell subtypes, but it seems to be expressed to a similar extent in most goblet cell types examined.22

While the data suggest a role for IRE1β in goblet cells, it is unclear if IRE1β functions in other cell types of the intestinal epithelium. Expression of Ern2 transcript is lower in other secretory cell types and substantially lower in absorptive lineages (Fig. 2 and ref. 16) Still, as an enzyme, even low levels of IRE1β could contribute to proteostasis in other lineages. In Paneth cells, which are highly specialized secretory cells, IRE1β may serve a compensatory role with IRE1α. Single gene deletion of either Ern1 or Ern2 in vivo does not have any effect on Paneth cell morphology compared to WT controls. However, compound deficiency of both paralogues led to a complete collapse of the secretory compartment and absence of lysozyme IHC staining (i.e., loss of Paneth cells), mimicking mice with epithelial deletion of Xbp1.19 This suggests that IRE1β and IRE1α function in splicing XBP1 may overlap and compensate for each other in this cell type. IRE1β may also function in absorptive cells, where Ern2 transcript expression is lowest. Genetic deletion of Ern2 has an impact on lipid metabolism in the small intestine—a function primarily attributed to absorptive enterocytes—where IRE1β is proposed to post-transcriptionally regulate Mttp mRNA stability via RIDD.23 Thus, although highly enriched in goblet cells and associated with mucin biosynthesis, IRE1β could function more broadly in other aspects of intestinal homeostasis.

IRE1β plays an overall protective role in mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Ern2−/− mice show increased sensitivity to DSS colitis.14 While the extent of inflammation is similar in WT and Ern2 deficient animals, loss of IRE1β results in an earlier onset, impaired recovery, and increased mortality following injury.15 This could be due to defects in goblet cells and/or mucus function in Ern2−/−. Along these lines, Muc2-deficient mice (and other models with defects in mucin biosynthesis) are also more susceptible to colonic injury.24,25 In addition to chemically induced colitis, IRE1β protects against IRE1α-driven inflammation in a Crohn’s disease (CD)-like mouse model. In this case, hyperactivation of IRE1α in Atg16l1;Xbp1ΔIEC mice drives CD-like ileitis, whereas IRE1β provides a protective function in this model.19 As inflammation in this specific model likely originates in Paneth cells,26 it may not be related to a role for IRE1β in mucus homeostasis. Instead, this model is consistent with the proposed role of IRE1β as a dominant negative suppressor of IRE1α under conditions of ER stress,17 where loss of IRE1β may enable IRE1α activation to drive inflammation. However, this mechanism has not been tested in vivo and further studies are needed to evaluate how IRE1β protects against colitis in these and other models.

It is largely unknown what role IRE1β might play in human gastrointestinal disease. IRE1β expression is reduced in colorectal cancer (Broad Firehose data browser https://gdac.broadinstitute.org/), and decreased IRE1β levels are associated with worse clinical outcome.27 In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), ERN2 mRNA expression is decreased in rectal biopsies from individuals with ulcerative colitis (UC)28—though the molecule has not yet been implicated in IBD by genome wide association studies. This is consistent with a role for IRE1β in goblet cells and the associated reduction in mucus secretion seen clinically in patients with UC.29 Recent single cell analysis of human colon epithelial cells from individuals with UC shows that other cell types besides goblet cells also express IRE1β,30 implicating other functions, at least in inflamed tissues.

As in the GI tract, IRE1β expression is associated with mucus-producing cells in the airway epithelium (Fig. 2). IRE1β expression is found in the nasopharynx, trachea, and bronchus, all of which contain goblet cells and other mucus-producing cells, whereas expression was not found in mouse lung parenchyma or lung alveoli that lack goblet cells.13,31 In vivo, Ern2−/− mice have been reported to show decreased mucus cell content and goblet cell numbers in the nasopharynx. When challenged with ovalbumin (OVA) in an allergic airway inflammation model, IL13 levels, and eosinophilic cell counts were similar as in WT littermates, but in contrast, they did show significantly reduced mucus production as monitored by PAS and MUC5B staining.13 The mucus phenotype was not linked to an IRE1α-mediated ER stress response, but rather to induction of XBP1s via IRE1β endonuclease activity and a putative XBP1-target gene, Agr2, that is required for mucin biosynthesis and mucus production. Notably, Ern2 expression is highly correlated with expression of Agr2 and the goblet cell transcription factor Spdef, whereas Ern1 is not.32 However, while the fundamental role of AGR2 to drive mucin production upon OVA challenge was confirmed in a separate study, this did not appear to depend on XBP1 splicing.33 Unlike the gastrointestinal epithelium where the mucus layer provides a protective barrier (and loss of that barrier is associated with human disease, such as UC), overproduction of mucus in the airway epithelium is a hallmark of asthma and cystic fibrosis (CF) and contributes to disease pathophysiology. Notably, IRE1β expression is increased in bronchial epithelia obtained from individuals with asthma and CF compared to tissue from healthy individuals.13,32 As these studies point towards a potential role for IRE1β in driving lung inflammatory pathologies, further mechanistic studies on the function of IRE1β in asthma models are warranted.

Overall, the in vivo studies on IRE1β expression implicate a role for the protein in development, maintenance, and functional regulation of epithelial barriers lining mucosal surfaces. Secretory cell types of the barrier epithelium, especially goblet cells, express IRE1β to a much higher degree explaining the tissue distribution and likely functions in supporting enhanced protein secretion. Additionally, other cell types forming the epithelial barrier of the intestine express IRE1β, especially when inflamed, though with some evidence for function in normal physiology. Exactly how IRE1β function contributes to epithelial cell biology in these different contexts is still not fully defined.

Function and regulation of IRE1β endonuclease activity

Given the apparent role of IRE1β in mucosal homeostasis, it is important to consider how IRE1β functions to fulfill this role—what is the specific activity that IRE1β contributes to and how is it distinct from IRE1α to necessitate having a second paralogue in epithelial cells at mucosal surfaces. Because IRE1α and IRE1β are so highly homologous, we frame this section by first discussing the structure and function of the more well studied and ubiquitously expressed paralogue IRE1α.

IRE1α, conserved endonuclease with two major outputs

Just like IRE1β, IRE1α is a single pass type I transmembrane protein with an ER luminal N-terminal sensor domain (LD), a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic C-terminal effector kinase and endonuclease domain (Fig. 1). Two different models have been proposed to explain how ER stress is detected through the LD of IRE1.4,34 The first model, the chaperone binding model, posits that IRE1 is kept in an inactive, monomeric state by binding to the heat shock protein (HSP70) chaperone BIP.4,35–37 Upon accumulation of client proteins, BIP becomes sequestered and dissociates from the UPR sensors, which leads to their (default) dimerization and subsequent autophosphorylation and activation. This model is—amongst others—supported by observations that maximal UPR activation is correlated with a shortage of BIP, rather than accumulation of client proteins in the ER per se.38,39 The second, more recent model was put forth upon crystallization of the LD of yeast IRE1, which revealed the presence of a peptide binding groove traversing the IRE1LD interface.40,41 The direct binding model posits that unfolded proteins directly bind to IRE1, which is—amongst others—supported by in vitro studies showing that addition of peptide ligands to dilute solutions of recombinant yeast IRE1LD induce a shift towards higher order species.42 The two models are not mutually exclusive and were reconciled in the so-called ratiometric ER stress-sensing model, in which the ratio between BIP and client proteins was postulated to determine the outcome of the UPR.38,39 In brief, UPR transducers are in the OFF state when bound to BIP, which keeps them in a monomeric inactive form, and in the ON state when bound to client proteins, which further stabilizes their oligomeric conformation. Finally, emerging evidence indicates that IRE1 can also be activated by so-called lipid bilayer stress,43–45 independent of its luminal domain. Through an amphipathic helix (AH) in its transmembrane domain IRE1 “senses” the composition of the ER membrane. More dense packing of the ER membrane (due to an increase in cholesterol levels or saturated lipids for example), would result in an increased energetic cost to “squeeze” the membrane, lowering the threshold for dimerization and clustering.43 Of note, IRE1β has also been postulated to become activated in conditions of high cholesterol,23 although at first sight the AH domain does not appear to be conserved in IRE1β.

Whatever the upstream trigger is, it is widely accepted that dimerization of the LD brings together two or more cytosolic effector domains, enabling transphosphorylation of the kinase domain in a face-to-face configuration. This allosterically activates the IRE1-endonuclease domain by stabilizing the dimer interface necessary for RNase activity in a back-to-back configuration.41,46,47 Notably, this can also be achieved by adding ATP competitive inhibitors that inhibit IRE1 kinase activity but at the same time strengthen the IRE1 dimer interface, revealing that the phosphotransfer as such is not needed for IRE1 activation; rather activation is driven by a conformational change in the kinase domain provoked by nucleotide binding.48–51

The RNase activity of IRE1 is highly cooperative, indicating that full RNase activity is achieved only upon assembly of more than two IRE1 molecules, which is supported by crystal structures,47,52 in vitro studies, and by cellular data revealing the presence of IRE1 foci in the ER upon activation by ER stress triggers.53,54 Oligomerization of IRE1 molecules is believed to stabilize a composite RNA binding pocket that recruits XBP1 (HAC1 in yeast) mRNA accommodating one stem loop per IRE1 dimer.47,52 This places the scissile phosphate in direct contact with the catalytic residues cleaving the scissile bond and initiating the unconventional splicing of XBP1/HAC1 mRNA. The two mRNA fragments are religated by tRNA ligase.55–57 Spliced XBP1 encodes a transcription factor called XBP1s, which plays a prominent role in the UPR, driving expression of genes involved in protein quality control such as chaperones, foldases or members of the ER-associated degradation system (ERAD) as well as lipid biosynthesis enzymes.58,59 Together, these pathways jointly contribute to restore ER homeostasis.60

More recently a second IRE1-endonuclease dependent output has been described. In ill-defined conditions IRE1 targets several mRNA species for degradation, supposedly as an alternative mechanism to lower folding load.6,7 The mRNA sequence important for cleavage resembles the consensus sequence earlier identified for XBP1, and consists of a stable stem loop structure with specific conserved residues in the loop.61–63 The free 5′ and 3′ ends are then rapidly degraded by cellular exoribonucleases.23

So far, it remains unclear which mRNAs are targeted for degradation and why. Compared to Drosophila, where ER localization seems sufficient (although not always necessary62) to ensure degradation,64 RIDD specificity in mammalian species seems to be more narrow. RIDD is especially prominent upon overexpression of IRE1 or upon loss of XBP1 in tissue-specific knockout models, which drives hyperactivation of IRE1.65–67 Several theories prevail on the physiological role of IRE1-mediated RIDD. It has been postulated that the switch from XBP1 splicing to RIDD determines cell fate and mediates the transition from a pro-survival role of IRE1 towards a pro-apoptotic role.68 In line with this, later studies revealed that RIDD targets select miRNAs for decay, which leads to stabilization of specific pro-apoptotic factors like caspase-2 or thioredoxin interacting protein TXNIP1.69,70 In HeLa cells, IRE1β was found to mediate RIDD dependent decay of 28S rRNA, which was suggested to explain its toxicity upon overexpression.71 RIDD does not play a pro-apoptotic role in every cell type though and in dendritic cells RIDD even protects from cell death in conditions of XBP1 deficiency.72 In many cell types, RIDD is considered as a back-up mechanism to prevent from proteotoxic stress when other UPR mechanisms fail. In this regard, it has been postulated that in “normal” conditions IRE1 would target XBP1 as its preferred substrate. Only when all XBP1 would be consumed and IRE1 would still be active, its endonuclease activity would switch to RIDD and degrade abundant mRNA species as a way to avoid overwhelming of the ER.73 It can be envisioned that tuning the mRNA levels of prominent ER folding clients such as proinsulin in pancreas islet cells or lipid metabolic enzymes in hepatocytes helps to balance the mRNA pool to folding capacity in the ER. Also in physiological conditions, this could play a beneficial role. How RIDD-mediated fine-tuning of mRNA levels is regulated is still poorly understood and whether distinct oligomeric/dimeric conformations of IRE1 are needed to mediate XBP1 splicing versus RIDD output also awaits further investigation.68,74

Comparison of IRE1α and IRE1β endonuclease activity

Human IRE1β shares a relatively high degree of sequence homology with IRE1α71 (Fig. 1), suggesting that it likely adopts similar overall structure and, by extension, functions for each of the domains. However, there are notable differences in sequence (discussed further below, also see Supplementary Tables 1–5 for a detailed overview), and as there are no crystal structures available for IRE1β it is unknown how aspects of their structures may diverge.

Most studies are consistent with the idea that IRE1β, like IRE1α, can digest XBP1 mRNA in vitro48,75 and enable XBP1 splicing in cells17 to amplify the secretory pathway. In vivo, IRE1β appears to mediate XBP1-dependent mucus production in the airway epithelium following allergen stimulation, contributing to disease.13 Overexpression of mouse9,75 or human IRE1β17 increases basal levels of XBP1 splicing and XBP1s-dependent gene expression in cultured cells even in the absence of endogenous IRE1α. However, in these in vitro models, overexpression of IRE1β results in less XBP1 splicing compared to overexpression of IRE1α at similar protein levels, suggesting that IRE1β may have weaker enzymatic activity.17 Consistent with this, when compared to purified IRE1α, purified full-length IRE1β has substantially weaker steady-state endonuclease activity for a model XBP1 stem loop.17 Gray et al. propose that this is due to impaired oligomerization of IRE1β in cells and an altered pattern of phosphorylation, including the lack of phosphorylation at conserved serine residues in the activation loop that are known to be important for maximal IRE1α endonuclease activity.17,76 On the other hand, Feldman et al. report that the purified cytosolic domain of IRE1β, when tested in vitro, has similar if not greater endonuclease activity than the cytosolic domain of IRE1α.48 These disparate lines of evidence could mean that regions outside the cytosolic domain modulate IRE1β endonuclease activity in the context of the full-length protein or that other differences in the expressed and purified IRE1β molecules affect the enzymatic readout (e.g., phosphorylation status, affinity tags, expression hosts, etc.).

It has been widely thought that IRE1β has preferential RIDD activity,71,77 largely based on the evidence that human IRE1β, compared to IRE1α, appeared to have weaker activity for cleavage of an XBP1 substrate but stronger activity for digestion of 28S rRNA.71,77 Domain swap experiments also suggested that the IRE1β endonuclease domain was better tuned for the RIDD output whereas IRE1α endonuclease domain conferred preference for XBP1 substrates.77 Additional IRE1β-dependent RIDD targets have now been identified that are distinct from those of IRE1α,78 further implicating enhanced (or unique) RIDD function for IRE1β and that this may play a physiologic role in vivo (e.g., Muc2 in mucus homeostasis and Mttp in chylomicron secretion).14,23 Still, IRE1β can splice XBP1 mRNA, and because the cellular readouts for XBP1 splicing and RIDD are not directly comparable, we cannot yet conclude that IRE1β has a preference for enzymatically cleaving one substrate over another. More detailed kinetic analyses of the enzymatic activity of IRE1α and IRE1β are needed to fully assess their relative activities and substrate specificities.

Impact on ER stress and the UPR signaling at mucosal surfaces

In vivo, the small intestine and colon of mice lacking IRE1β have elevated markers of ER stress and an UPR, suggesting that IRE1β may function to restrict UPR signaling under homeostatic conditions.14,19 Intestinal epithelial cell lines and organoids that express IRE1β also have a dampened UPR to ER stress stimuli, and expression of IRE1β in cell models is sufficient to suppress stress-induced IRE1α activation and XBP1 splicing.17 We have proposed that IRE1β can interact directly with IRE1α oligomers, thereby forming hetero-oligomers. As such, IRE1β acts as a dominant negative suppressor of IRE1α signaling, where IRE1β has weaker intrinsic endonuclease activity unresponsive to ER stress agonists.17 It is possible that in vivo IRE1β acts to restrict UPR signaling and downstream inflammatory sequelae in epithelial cells lining mucosal surfaces, which are intimately and chronically exposed to environmental stimuli. We note again, however, that under stress, IRE1β can still contribute to XBP1 splicing and/or RIDD activity as a means to adapt the epithelial cell’s protein folding capacity and restore mucosal homeostasis.

How IRE1β activity is regulated in these conditions remains an open question. In a side-by-side comparison of IRE1α versus IRE1β, IRE1β showed smaller responses to common chemical inducers of ER stress (see also Table 1).17 As mentioned above, this is associated with reduced levels of phosphorylation and impaired oligomerization compared to IRE1α—both of which are hallmarks of stress-induced IRE1 activation.17 Nonetheless, IRE1β appears to directly bind unfolded proteins,79 and it could potentially respond to other environmental cell stressors chronically present at mucosal surfaces. For instance, there are several examples where IRE1β is affected by dietary components. This includes a role for IRE1β in tuning chylomicron secretion in response to high-fat, high-cholesterol diet,23 increased IRE1β expression and XBP1 splicing associated with colonic inflammation following high-fat diet,80 and increased IRE1β expression in response to ER stress from prolonged exposure to dietary emulsifiers.81 Other dietary exposures as well as gut microbes, toxins, and viruses may all have an impact on epithelial cell ER function and thus affect IRE1β activity. Further studies are needed to determine how different environmental stressors (either acute or chronic) affect IRE1β activity in relevant epithelial cell models.

Table 1.

Activating triggers of IRE1.

| Yeast | Vertebrate IRE1α | Vertebrate IRE1β | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIP dissociation is required, but not sufficient for activation. |

BIP dissociation is sufficient for activation. BIP binding is modulated by accessory factors (HSP47, ERDJ4). |

BIP binding has been both observed and contested. |

Bertolotti et al.37 Oikawa et al.100 Oikawa et al.101 Oikawa et al.79 Amin-Wetzel et al.36 Sepulveda et al.102 |

| Unfolded proteins and model peptide substrates bind the MHC-I-like groove. | MHC-I groove appears absent, but unfolded proteins/peptides bind IRE1α and may induce a conformational change. This notion has been contested. | Unfolded proteins may be a ligand, presence of MHCI-like groove unknown. |

Credle et al.40 Zhou et al.95 Gardner and Walter42 Oikawa et al.79 Karagöz et al.34 Amin-Wetzel et al.35 |

| Lipid bilayer stress is sensed by the amphipathic helix (AH). | Lipid membrane perturbation activates IRE1α, it contains an AH. |

AH not readily observed. IRE1β-mediated RIDD upon high cholesterol diet. |

Volmer et al.45 Ariyama et al.103 Halbleib et al.43 Iqbal et al.23 |

| PDIA-mediated regulation unknown. | PDIA’s 1 and 6 regulate IRE1α activity. | PDIA-mediated regulation unknown. |

Groenendyk et al.104 Eletto et al.105 Eletto et al.106 Yu et al.107 |

| Ire1 is activated by classical ER stress inducers (Tun, Thap, etc). | IRE1α is activated by classical ER stress inducers (Tun, Thap etc). | IRE1β does not respond to classical ER stress agents (Thap). |

Cox et al.108 Tirasophon et al.8 Grey et al.17 |

The references given here illustrate the differences between the IRE1 homologues and paralogues. This list is not exhaustive, and many other colleagues have contributed to elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of IRE1 proteins. We apologize that we could not include every single reference here.

AH amphipathic Helix, BIP binding immunoglobulin protein, ERDJ4 endoplasmic reticulum DNA J domain-containing protein 4, HSP47 47 kDa heat shock protein, IRE1 inositol-requiring enzyme 1, MHC major histocompatibility complex, PDIA protein disulfide isomerase family A, RIDD regulated IRE1-dependent decay, Thap thapsigargin, Tun tunicamycin.

Evolution of IRE1β at mucosal surfaces

The existing literature points to a role for IRE1β in epithelial homeostasis at mucosal barriers. In particular, the evidence points to a role in maintaining proteostasis in highly secretory cells and in aspects of secretion associated with absorptive lineages through different enzymatic activities. These activities are also expected for IRE1α, and the question remains as to why two IRE1 paralogues are needed to fulfill these roles at mucosal surfaces? One hypothesis, is that IRE1β and IRE1α evolved to segregate RIDD and XBP1 splicing activities in mucosal tissues. Yeasts strains only have the IRE1 branch of the UPR. In some yeast strains, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, IRE1 has evolved to exclusively splice the XBP1 homolog HAC1 to orchestrate the UPR,55,82,83 whereas others, such as IRE1 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (which lacks a HAC1/XBP1-like signaling arm) functions solely via RIDD to regulate proteostasis.84 So, IRE1β may have evolved from an ancestral form more similar to S. pombe IRE1 with dominant RIDD activity. Evidence in favor of this is that IRE1β has RIDD targets that are unique from IRE1α—though IRE1β-mediated XBP1 splicing is important as well. A second idea is that maintaining proteostasis in highly secretory epithelial cells, such as goblet and Paneth cells of the intestine, is absolutely critical for epithelial integrity and two IRE1 paralogues are required to compensate for one another in case one mechanism fails. As discussed above, there is evidence for this idea. However, such functional redundancy does not exist in other highly secretory and equally essential cell types (e.g., pancreatic acinar cells, B cells). IRE1β, in fact, appears to function in some contexts that are not equivalently served by IRE1α (so functions may exist beyond merely compensatory). A third hypothesis is that IRE1β evolved in response to the complexity and dangers present at the host-environment interface, where mucosal epithelial cells are chronically exposed to dietary components, allergens, bacteria, and viruses. This is consistent with a role for IRE1β in mucus production13,14 which itself is regulated by the mucosal environment and provides a key barrier function intrinsic to host defense at mucosal surfaces. In addition, IRE1β provides mechanisms to tune how epithelial cells respond to chronic ER stress stimuli. However, many organisms have epithelial tissues that interface with the environment, and it is unknown if additional IRE1 paralogues have evolved in all instances.

To identify the evolutionary origins of IRE1β in mammals, we analyzed IRE1 sequences from a range of eukaryotes. As can be seen from the evolutionary tree prediction (Fig. 3), two distinct IRE1 paralogues are found only in vertebrates. Yeast, worms, flies, and the sea squirt all contain only one form of IRE1. Notably, IRE1β in vertebrates did not evolve from distinct ancestral forms of IRE1 that are distinct in terms of their XBP1 splicing versus RIDD activities as is the case for IRE1 in S. cerevisiae compared to S. pombe.84 Instead, the evolutionary analysis suggests that IRE1 paralogues in higher eukaryotes may have arisen from whole genome duplication events, which are thought to be the basis for the complex genomes in vertebrates.85,86

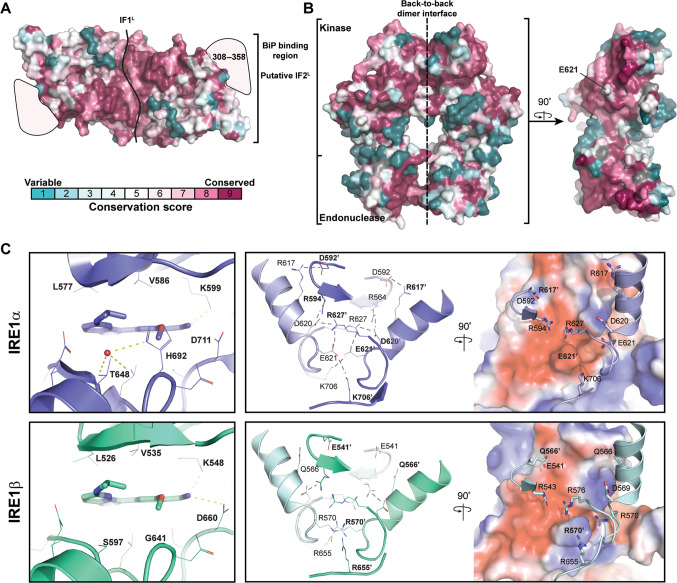

Fig. 4. Impact of sequence variation on IRE1β structure and function.

a, b Sequence conservation was mapped onto the surface of human IRE1α luminal domain (a, pdb 2hz695) and cytosolic domains (b, pdb 4z7h.51) Conservation and coloring was calculated using ConSurf server96,97 with multiple sequence alignment from Fig. 3. c Close-up view of putative interactions in (left panel) nucleotide binding pocket and (right panel) back-to-back dimer interface for IRE1β model (generated from 4z7h template using MODELER.98,99). In the dimer representation individual protomers are colored in darker and lighter (IRE1α) blue or (IRE1β) green. Residues are labeled with BOLD’ (e.g., R627′) and REGULAR (e.g., R627) font for the different protomers. The surface rendering shows the electrostatic potential (Negative–Neutral–Positive, Red–White–Blue) mapped onto the solvent excluded surface of one protomer with key interacting residues shown in cartoon and stick representation for the other protomer at the interface. Residues in cartoon view are labeled with regular type face black lettering (e.g., D592), and the position of residues on the surface rendering are labeled with bold type face black lettering (e.g., R617′).

Fig. 3. Phylogenetic tree of IRE1 and IRE1-like sequences from selected organisms.

A multiple sequence alignment of 96 IRE1 and IRE1-like coding sequences was made using MAFFT.92 A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed with IQ-TREE93 and visualized with FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Numbers indicate bootstrap values.94 The scale bar for the branch lengths represents genetic distances in the number of estimated nucleotide substitutions per site.

After whole genome duplications, the genomes progressively return to a diploid structure where most duplicated genes are lost. For a duplicated gene to be retained, it is typical that the duplicated genes divide their function through subfunctionalization or one paralogue adopts a novel function through neofunctionalization.87 Neofunctionalization could occur when one paralogue has a relaxed selective pressure that allows it to acquire mutations resulting in a new function. The longer branch lengths for IRE1β compared to IRE1α suggest that the evolutionary pressure on these paralogues is distinct, and that IRE1β has accumulated sequence variations (compared to IRE1α) that may allow for a novel function at mucosal surfaces. This is consistent with findings from Grey et al. where a non-conserved position near the nucleotide binding site in the kinase domain (H692 in human IRE1α and G641 in human IRE1β) reduces phosphorylation, impairs oligomerization, and confers weaker endonuclease activity for IRE1β17 (see Box 1 for more details). Additional sequence variations surrounding the nucleotide binding pocket have been exploited in the design of paralogue-specific inhibitors.48 In Supplementary Tables 1–5, we summarize many of the non-conserved positions in the luminal, transmembrane, juxtamembrane, kinase, and endonuclease domains of IRE1β and IRE1α, and we speculate on the impact they may have on structural, functional and/or regulatory features of IRE1β versus IRE1α (see Box 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–5).

Alongside the accumulation of amino-acid sequence variation, selective pressure will also lead to divergence in expression patterns caused by promoter sequence variation.88 In the case of IRE1β, expression is restricted to epithelial cells at mucosal surfaces. Although IRE1α is expressed in all cell types including those that express IRE1β, IRE1β expression appears much higher when in the same cell. Further studies are needed to define how IRE1β expression is regulated in distinct cell populations at the transcriptional and epigenetic levels. Comparison of ERN2 and ERN1 promoter regions for putative transcription factor binding sites and analysis of ChIP-seq datasets suggest enrichment of particular TFs in the IRE1β promoter that are associated with secretory lineages. One notable example is KLF4, which is required for goblet cell maturation.89 Thus, it is likely that a combination of unique transcriptional regulation (in particular in response to environmental stimuli) along with sequence and perhaps structural variations through evolution have tuned IRE1β’s function at mucosal surfaces.

Finally, it is interesting to speculate further on what selection pressure necessitated the need for IRE1β at mucosal surfaces. There is an obvious link to goblet cells and mucus production—a defining feature of a mucosal surface—either at homeostasis or in response to environment triggers such as allergens, microbes, or dietary components. Notably, a mucus-based system of barrier immunity has evolved specifically in vertebrates, and in particular mammals, as a means to separate microbes and environmental components from the epithelium. Invertebrates such as worms, flies, and the sea squirt—all of which have a single copy of IRE1—do not use a mucus-based system to separate the environment from their epithelium. Instead, they rely on a chitin-based system of barrier immunity. In Ciona intestinalis (sea squirt), an invertebrate in the Chordate phylum, digesta is encased in a chitin-based membrane, which together with secreted mucins (from the pharynx, not intestinal goblet cells) keeps luminal content away from the epithelial layer.90 But even within vertebrates there is remarkable variation in the evolutionary pressure on IRE1β sequences. Mammalian IRE1β appears to have undergone the most variation compared to its IRE1α counterpart (Fig. 3), which when considered with its tissue-specific expression clearly implicates a unique role for IRE1β in mucosal homeostasis and regulating how the epithelium interfaces with the environment. Lower vertebrates such as fish, however, which in most cases have two copies of IRE1, appear somewhat intermediate to the mammalian paralogues. It is notable that IRE1β, like IRE1α, is ubiquitously expressed in medaka fish.91 Additionally, fish utilize both chitin and mucins in barrier function.90 So, while speculative, this poses an interesting question for how IRE1β evolved and diverged from IRE1α in different vertebrates based on their adaptation of a mucus-based system of barrier immunity. Further studies are needed to evaluate and compare IRE1β stress-sensing and endonuclease activities from different species along the vertebrate lineage. But, at least in mammals, it seems likely that IRE1β function in combination with other features of mucus-producing goblet cells may have evolved for this defining feature of innate host defense.

Box 1 Evolution of IRE1β sequence and potential impact on its function and regulation.

There is a relatively high degree of sequence homology between IRE1β and IRE1α for the luminal, kinase, and endonuclease domains (Fig. 1). However, there are notable divergences in sequence throughout the luminal and cytosolic domains (Fig. 4a, b, Supplementary Tables 1–5). The most sequence divergence in the luminal domain is found distal to the dimerization interface, including an unresolved flexible region that is involved in BIP binding and an alternative dimerization interface IF2L34,35. This suggests there may be differences in stress-sensing mechanisms for IRE1β and IRE1α. In the kinase and endonuclease domains many important catalytic and regulatory motifs are highly conserved. However, divergent positions near the nucleotide binding pocket and at key interfaces may affect activity. For example, the divergent amino-acid G641 in human IRE1β (H692 in hIRE1α, Fig. 4cleft panel) is associated with reduced phosphorylation, impaired oligomerization, and weaker endonuclease activity.17 In fact, differences in amino acids surrounding the nucleotide binding pocket have been exploited in the design of IRE1β-specific kinase inhibitors.48 In addition, IRE1β has non-conserved substitutions at the kinase domain “back-to-back” dimer interface that mediates an active kinase-endonuclease domain conformation.51,109 This includes Q566 (R617 in IRE1α) and R570 (E621 in IRE1α) that remove salt bridges from the dimer interface and potentially introduce destabilizing electrostatic interactions (Fig. 4c, right panel). Although in our modeled IRE1β dimer structure, steric clashes would necessitate alternative interface packing interactions that may accommodate such substitutions. Nevertheless, IRE1β may have acquired these and other sequence variations (see also Supplementary Table S1 for a full overview) to tune stress-sensing and endonuclease activities specifically for its role at mucosal surfaces.

Concluding remarks

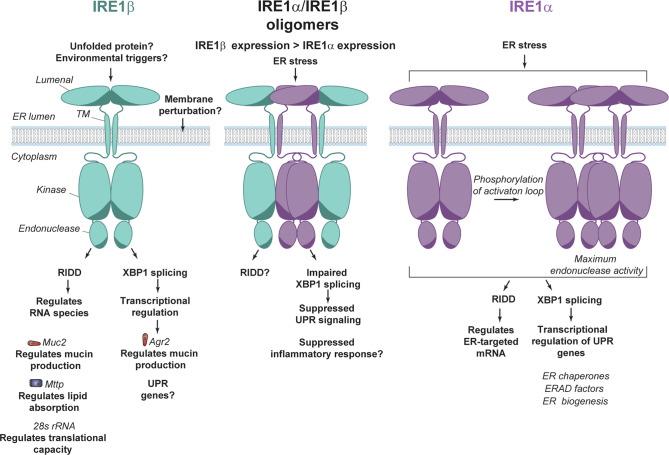

Whole genome duplication events in vertebrates gave rise to two IRE1 paralogues, IRE1α and IRE1β. IRE1α retained its ancestral function in vertebrates, while IRE1β exhibits neofunctionalization in the mucosal environment (a schematic of IRE1α and IRE1β function is depicted in Fig. 5). IRE1β is substantially enriched in goblet cells, but whether the influence of IRE1β is limited to secretory cells in the mucosa remains largely unexplored.

Fig. 5. Schematic summarizing the function of IRE1β in mucosal homeostasis.

IRE1β contributes to XBP1 splicing and/or RIDD activity to maintain mucosal homeostasis in goblet cells (via regulation of Muc2 and Agr2) and enterocytes (via regulation of Mttp). In cells where both isoforms are present, IRE1β interacts with IRE1α oligomers in a manner to suppress stress-induced XBP1 splicing. In comparison with IRE1α, IRE1β displays reduced phosphorylation, impaired oligomerization, and a weaker endonuclease activity.

While it is clear from in vivo experiments that IRE1β is essential in maintaining mucosal homeostasis,13–15,19 the molecular details of IRE1β’s activity remain obscure. Based on the evidence found in both structural analysis and in vitro experiments,17 it appears that IRE1β behaves as a weak XBP1-splicing endonuclease due to key residues not being conserved between IRE1α and IRE1β. Still, even though there is ample evidence for IRE1β-mediated RIDD in vivo,14,23 even weak IRE1β-mediated XBP1 splicing may be physiologically relevant.13 This indicates that IRE1β may have a broad range of effects in mucosal epithelia and future investigations will reveal more molecular details on this new player in intestinal homeostasis.

Outstanding questions

Does IRE1β function similarly in all goblet cell subtypes, and does it play a role in other cell types lining mucosal surfaces? What transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms control tissue and cell-type specific expression of IRE1β in mucosal epithelial cells?

Is IRE1β activated by ER stress? What other cellular and environmental triggers (e.g., lipids, microbiota, IL13, allergens) regulate IRE1β expression and activity? If not activated by ER stress, how does basal IRE1β signaling differ from stress-induced signaling typically seen with IRE1α?

What are the contributions of IRE1β XBP1 splicing and RIDD activity to mucosal homeostasis? How are these processes activated, what are the physiologic targets, and how do conformation/oligomerization status regulate the functional output?

How has evolution of IRE1β sequence tuned its stress-sensing and endonuclease activities in comparison to IRE1α? What impact do non-conserved positions have on IRE1β structure and regulation?

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R37DK048106 (W.I.L.), K01DK119414 (M.J.G.), Harvard Digestive Disease Center (P30DK034854, W.I.L.), and Harvard Digestive Disease Center Pilot and Feasibility Grant (M.J.G.). The S.J. Lab is supported by an ERC Consolidator Grant (DCRIDDLE-819314), FWO program grants (G017521N and G063218N) and an EOS grant (G0G7318N). E.C. was supported in part by a FWO Aspirant grant (11Z5615N). We thank Arthur Zwaenepoel for his assistance with phylogenetic tree construction and Prof Dr. Pieter De Bleser for his insights into comparative genomic analysis and transcription factor analysis. We thank Prof. Lars Vereecke for his critical reading of the paper.

Author contributions

C.D.N. performed evolutionary tree analysis. M.J.G. and M.S. performed sequence analysis. E.C., M.S., W.I.L., M.J.G., and S.J. wrote the review paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Eva Cloots, Mariska S. Simpson.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Sophie Janssens, Michael J. Grey.

Contributor Information

Sophie Janssens, Email: Sophie.janssens@irc.vib-ugent.be.

Michael J. Grey, Email: Michael.Grey@childrens.harvard.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41385-021-00412-8.

References

- 1.Uhlen M, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hetz C, Papa FR. The unfolded protein response and cell fate control. Mol. Cell. 2018;69:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hetz C, Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:421–438. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preissler, S. & Ron, D. Early events in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol.1110.1101/cshperspect.a033894 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollien J, et al. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 2009;186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollien J, Weissman JS. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2006;313:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1129631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tirasophon W, Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. A stress response pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus requires a novel bifunctional protein kinase/endoribonuclease (Ire1p) in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1812–1824. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang XZ, et al. Cloning of mammalian Ire1 reveals diversity in the ER stress responses. EMBO J. 1998;17:5708–5717. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams CJ, Kopp MC, Larburu N, Nowak PR, Ali MMU. Structure and molecular mechanism of ER stress signaling by the unfolded protein response signal activator IRE1. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019;6:11. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frakes AE, Dillin A. The UPR(ER): sensor and coordinator of organismal homeostasis. Mol. Cell. 2017;66:761–771. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman OI, Haller D. ER stress and the UPR in shaping intestinal tissue homeostasis and immunity. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2825. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martino MB, et al. The ER stress transducer IRE1beta is required for airway epithelial mucin production. Mucosal. Immunol. 2013;6:639–654. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuru A, et al. Negative feedback by IRE1beta optimizes mucin production in goblet cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:2864–2869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212484110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertolotti A, et al. Increased sensitivity to dextran sodium sulfate colitis in IRE1beta-deficient mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2001;107:585–593. doi: 10.1172/jci11476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haber AL, et al. A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature. 2017;551:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature24489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grey, M. J. et al. IRE1beta negatively regulates IRE1alpha signaling in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Cell Biol.21910.1083/jcb.201904048 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Birchenough GM, Johansson ME, Gustafsson JK, Bergstrom JH, Hansson GC. New developments in goblet cell mucus secretion and function. Mucosal. Immunol. 2015;8:712–719. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tschurtschenthaler M, et al. Defective ATG16L1-mediated removal of IRE1alpha drives Crohn’s disease-like ileitis. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:401–422. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birchenough GM, Nyström EE, Johansson ME, Hansson GC. A sentinel goblet cell guards the colonic crypt by triggering Nlrp6-dependent Muc2 secretion. Science. 2016;352:1535–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDole JR, et al. Goblet cells deliver luminal antigen to CD103+ dendritic cells in the small intestine. Nature. 2012;483:345–349. doi: 10.1038/nature10863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyström, E. E. L. et al. An intercrypt subpopulation of goblet cells is essential for colonic mucus barrier function. Science37210.1126/science.abb1590 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Iqbal J, et al. IRE1beta inhibits chylomicron production by selectively degrading MTP mRNA. Cell Metab. 2008;7:445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heazlewood CK, et al. Aberrant mucin assembly in mice causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and spontaneous inflammation resembling ulcerative colitis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Sluis M, et al. Muc2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for colonic protection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:117–129. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adolph TE, et al. Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2013;503:272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature12599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang Y, et al. Expression of inositol-requiring enzyme 1β is downregulated in colorectal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017;13:1109–1118. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haberman Y, et al. Ulcerative colitis mucosal transcriptomes reveal mitochondriopathy and personalized mechanisms underlying disease severity and treatment response. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:38. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07841-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Post S, et al. Structural weakening of the colonic mucus barrier is an early event in ulcerative colitis pathogenesis. Gut. 2019;68:2142–2151. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smillie CS, et al. Intra- and inter-cellular rewiring of the human colon during ulcerative colitis. Cell. 2019;178:714–730.e722. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vieira Braga FA, et al. A cellular census of human lungs identifies novel cell states in health and in asthma. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1153–1163. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0468-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen G, et al. IL-1β dominates the promucin secretory cytokine profile in cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2019;129:4433–4450. doi: 10.1172/jci125669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schroeder BW, et al. AGR2 is induced in asthma and promotes allergen-induced mucin overproduction. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012;47:178–185. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0421OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karagöz, G. E. et al. An unfolded protein-induced conformational switch activates mammalian IRE1. eLife610.7554/eLife.30700 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Amin-Wetzel, N., Neidhardt, L., Yan, Y., Mayer, M. P. & Ron, D. Unstructured regions in IRE1α specify BiP-mediated destabilisation of the luminal domain dimer and repression of the UPR. eLife810.7554/eLife.50793 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Amin-Wetzel N, et al. A J-protein Co-chaperone recruits BiP to monomerize IRE1 and repress the unfolded protein response. Cell. 2017;171:1625–1637.e1613. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, Ron D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:326–332. doi: 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakunts, A. et al. Ratiometric sensing of BiP-client versus BiP levels by the unfolded protein response determines its signaling amplitude. eLife610.7554/eLife.27518 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Vitale, M. et al. Inadequate BiP availability defines endoplasmic reticulum stress. eLife810.7554/eLife.41168 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Credle JJ, Finer-Moore JS, Papa FR, Stroud RM, Walter P. On the mechanism of sensing unfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:18773–18784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509487102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korennykh A, Walter P. Structural basis of the unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;28:251–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gardner BM, Walter P. Unfolded proteins are Ire1-activating ligands that directly induce the unfolded protein response. Science. 2011;333:1891–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.1209126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halbleib K, et al. Activation of the unfolded protein response by lipid bilayer stress. Mol. Cell. 2017;67:673–684.e678. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho, N. et al. Stress sensor Ire1 deploys a divergent transcriptional program in response to lipid bilayer stress. J. Cell Biol.21910.1083/jcb.201909165 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Volmer R, van der Ploeg K, Ron D. Membrane lipid saturation activates endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response transducers through their transmembrane domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:4628–4633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217611110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali MM, et al. Structure of the Ire1 autophosphorylation complex and implications for the unfolded protein response. EMBO J. 2011;30:894–905. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee KP, et al. Structure of the dual enzyme Ire1 reveals the basis for catalysis and regulation in nonconventional RNA splicing. Cell. 2008;132:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feldman HC, et al. Development of a chemical toolset for studying the paralog-specific function of IRE1. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019;14:2595–2605. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Papa FR, Zhang C, Shokat K, Walter P. Bypassing a kinase activity with an ATP-competitive drug. Science. 2003;302:1533–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1090031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Concha NO, et al. Long-range inhibitor-induced conformational regulation of human IRE1α endoribonuclease activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015;88:1011–1023. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joshi A, et al. Molecular mechanisms of human IRE1 activation through dimerization and ligand binding. Oncotarget. 2015;6:13019–13035. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Korennykh AV, et al. The unfolded protein response signals through high-order assembly of Ire1. Nature. 2009;457:687–693. doi: 10.1038/nature07661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belyy V, Tran NH, Walter P. Quantitative microscopy reveals dynamics and fate of clustered IRE1α. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020;117:1533–1542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915311117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li H, Korennykh AV, Behrman SL, Walter P. Mammalian endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor IRE1 signals by dynamic clustering. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:16113–16118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010580107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cox JS, Walter P. A novel mechanism for regulating activity of a transcription factor that controls the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1996;87:391–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jurkin J, et al. The mammalian tRNA ligase complex mediates splicing of XBP1 mRNA and controls antibody secretion in plasma cells. EMBO J. 2014;33:2922–2936. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sidrauski C, Cox JS, Walter P. tRNA ligase is required for regulated mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1996;87:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Acosta-Alvear D, et al. XBP1 controls diverse cell type- and condition-specific transcriptional regulatory networks. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/mcb.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moore K, Hollien J. Ire1-mediated decay in mammalian cells relies on mRNA sequence, structure, and translational status. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015;26:2873–2884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-02-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moore KA, Plant JJ, Gaddam D, Craft J, Hollien J. Regulation of sumo mRNA during endoplasmic reticulum stress. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e75723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oikawa D, Tokuda M, Hosoda A, Iwawaki T. Identification of a consensus element recognized and cleaved by IRE1 alpha. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6265–6273. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gaddam D, Stevens N, Hollien J. Comparison of mRNA localization and regulation during endoplasmic reticulum stress in Drosophila cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2013;24:14–20. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-06-0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hur KY, et al. IRE1alpha activation protects mice against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:307–318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osorio F, et al. The unfolded-protein-response sensor IRE-1alpha regulates the function of CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:248–257. doi: 10.1038/ni.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.So JS, et al. Silencing of lipid metabolism genes through IRE1alpha-mediated mRNA decay lowers plasma lipids in mice. Cell Metab. 2012;16:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Han D, et al. IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent. Cell Fates. Cell. 2009;138:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lerner AG, et al. IRE1 alpha induces thioredoxin-interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metab. 2012;16:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Upton JP, et al. IRE1α cleaves select microRNAs during ER stress to derepress translation of proapoptotic Caspase-2. Science. 2012;338:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1226191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iwawaki T, et al. Translational control by the ER transmembrane kinase/ribonuclease IRE1 under ER stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:158–164. doi: 10.1038/35055065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tavernier SJ, et al. Regulated IRE1-dependent mRNA decay sets the threshold for dendritic cell survival. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017;19:698–710. doi: 10.1038/ncb3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Anken, E., Bakunts, A., Hu, C. A., Janssens, S. & Sitia, R. Molecular Evaluation of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis meets humoral immunity. Trends Cell Biol.10.1016/j.tcb.2021.02.004 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Tam AB, Koong AC, Niwa M. Ire1 has distinct catalytic mechanisms for XBP1/HAC1 splicing and RIDD. Cell Rep. 2014;9:850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Calfon M, et al. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prischi F, Nowak PR, Carrara M, Ali MM. Phosphoregulation of Ire1 RNase splicing activity. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3554. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Imagawa Y, Hosoda A, Sasaka S, Tsuru A, Kohno K. RNase domains determine the functional difference between IRE1alpha and IRE1beta. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:656–660. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maurel M, Chevet E, Tavernier J, Gerlo S. Getting RIDD of RNA: IRE1 in cell fate regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014;39:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oikawa D, Kitamura A, Kinjo M, Iwawaki T. Direct association of unfolded proteins with mammalian ER stress sensor, IRE1beta. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e51290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gulhane M, et al. High fat diets induce colonic epithelial cell stress and inflammation that is reversed by IL-22. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28990. doi: 10.1038/srep28990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Laudisi F, et al. The food additive maltodextrin promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress-driven mucus depletion and exacerbates intestinal inflammation. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;7:457–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chapman RE, Walter P. Translational attenuation mediated by an mRNA intron. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:850–859. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kawahara T, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced mRNA splicing permits synthesis of transcription factor Hac1p/Ern4p that activates the unfolded protein response. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:1845–1862. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.10.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kimmig P, et al. The unfolded protein response in fission yeast modulates stability of select mRNAs to maintain protein homeostasis. eLife. 2012;1:e00048. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dehal P, Boore JL. Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Holland, L. Z. & Ocampo Daza, D. A new look at an old question: when did the second whole genome duplication occur in vertebrate evolution? Genome Biol.1910.1186/s13059-018-1592-0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Lynch M, Force A. The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics. 2000;154:459–473. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.1.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tirosh I, Bilu Y, Barkai N. Comparative biology: beyond sequence analysis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007;18:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Katz JP, et al. The zinc-finger transcription factor Klf4 is required for terminal differentiation of goblet cells in the colon. Development. 2002;129:2619–2628. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nakashima K, et al. Chitin-based barrier immunity and its loss predated mucus-colonization by indigenous gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3402. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05884-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ishikawa, T. et al. Unfolded protein response transducer IRE1-mediated signaling independent of XBP1 mRNA splicing is not required for growth and development of medaka fish. eLife610.7554/eLife.26845 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. UFBoot2: improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;35:518–522. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhou J, et al. The crystal structure of human IRE1 luminal domain reveals a conserved dimerization interface required for activation of the unfolded protein response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:14343–14348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606480103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Glaser F, et al. ConSurf: identification of functional regions in proteins by surface-mapping of phylogenetic information. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:163–164. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Landau M, et al. ConSurf 2005: the projection of evolutionary conservation scores of residues on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W299–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Webb B, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2016;54:5.6.1–5.6.37. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Oikawa D, Kimata Y, Kohno K. Self-association and BiP dissociation are not sufficient for activation of the ER stress sensor Ire1. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:1681–1688. doi: 10.1242/jcs.002808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Oikawa D, Kimata Y, Kohno K, Iwawaki T. Activation of mammalian IRE1alpha upon ER stress depends on dissociation of BiP rather than on direct interaction with unfolded proteins. Exp. Cell Res. 2009;315:2496–2504. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sepulveda D, et al. Interactome screening identifies the ER luminal chaperone Hsp47 as a regulator of the unfolded protein response transducer IRE1α. Mol. Cell. 2018;69:238–252. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ariyama H, Kono N, Matsuda S, Inoue T, Arai H. Decrease in membrane phospholipid unsaturation induces unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22027–22035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Groenendyk J, et al. Interplay between the oxidoreductase PDIA6 and microRNA-322 controls the response to disrupted endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra54. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Eletto D, Eletto D, Dersh D, Gidalevitz T, Argon Y. Protein disulfide isomerase A6 controls the decay of IRE1α signaling via disulfide-dependent association. Mol. Cell. 2014;53:562–576. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Eletto D, Eletto D, Boyle S, Argon Y. PDIA6 regulates insulin secretion by selectively inhibiting the RIDD activity of IRE1. FASEB J. 2016;30:653–665. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-275883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yu J, et al. Phosphorylation switches protein disulfide isomerase activity to maintain proteostasis and attenuate ER stress. EMBO J. 2020;39:e103841. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019103841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Feldman HC, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the allosteric inhibition of IRE1α with ATP-competitive ligands. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016;11:2195–2205. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.