Abstract

Family-based preventive interventions have been found to prevent youth internalizing symptoms, yet they operate through diverse mechanisms with heterogeneous effects for different youth. To better target preventive interventions, this study examines the effects of the Familias Unidas preventive intervention on reducing internalizing symptoms with a universal sample of Hispanic youth in a real-world school setting (i.e., effectiveness trial). The study utilizes emerging methods in baseline target moderated mediation (BTMM) to determine whether the intervention reduces internalizing symptoms through its impact on three distinct mechanisms: family functioning, parent stress, and social support for parents. Data are from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial of 746 Hispanic eighth graders and their parents assessed at baseline, 6-, 18- and 30-months post-baseline. BTMM models examined three moderated mechanisms through which the intervention might influence 30-month adolescent internalizing symptoms. The intervention decreased youth internalizing symptoms through improvements in family functioning in some models, but there was no evidence of moderation by baseline level of family functioning. There was some evidence of mediation through increasing social support for parents for those intervention parents presenting with lower baseline support. However, there was no evidence of mediation through parent stress. Post-hoc analyses suggest a possible cascading of effects where improvements in support for parents strengthened parental monitoring of youth and ultimately reduced youth internalizing symptoms. Findings support the intervention’s effects on internalizing symptoms in a universal, real-world setting, and the value of BTMM methods to improve the targeting of preventive interventions. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCTO1038206, First Posted: December 23, 2009.

Keywords: internalizing symptoms, Hispanic, youth, prevention, moderated mediation

U.S. Hispanic adolescents report high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms, also referred to as internalizing symptoms (Anderson & Mayes, 2010). Elevated internalizing symptoms during this developmental period can cause impairments in health, academic and social realms, as well as risk for poor long-term outcomes (Bertha & Balasz, 2013; National Academies, 2019). Hispanic adolescents and their families are often exposed to chronic economic, immigration, and acculturative stressors known to exacerbate the risk of internalizing symptoms among young people (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Yoshikawa, Aber & Beardslee, 2012) making preventive interventions critical for this group.

Familias Unidas is a preventive intervention with effects on drug use and sexual risk behaviors among Hispanic youth across universal, selective, and indicated samples (Prado & Pantin, 2011; Prado et al., 2012). While not specifically targeting internalizing symptoms, the intervention has documented “crossover effects” on internalizing symptoms among high-risk youth, including youth with externalizing and conduct problems, aggressive behaviors, and delinquency (Perrino et al., 2016a; 2016b). A synthesis study pooling data from multiple Familias Unidas trials and youth at different risk levels also found effects on youth internalizing problems for youth whose families were low on family functioning (Perrino et al., 2014). However, this intervention’s crossover effects on internalizing symptoms have not yet been examined in an exclusively universal sample nor in an effectiveness trial, defined as a study implemented in a real-world setting without the strict controls of an efficacy trial (Gartlehner, Hansen, Nissman, Lohr & Carey, 2006). Exploring intervention effects on internalizing symptoms in a universal sample is important because the intervention may yield protective effects for youth more broadly during a key developmental risk period, not just for those already showing behavioral problems. Further, examining effects in a real-world setting builds confidence that communities can deliver the intervention on their own, promoting dissemination of evidence-based interventions and advancing public health.

Yet, to enhance the impact of interventions, it is also important to clarify the mechanisms by which interventions operate, particularly for youth presenting with specific needs for the various intervention targets. Familias Unidas is guided by Ecodevelopmental Theory which contends that adolescent behavioral problems are influenced by risk and protective factors in their environmental contexts (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). These include family, peer and school microsystems, as well as broader exosystem factors that influence youth through impacts on parents (Prado & Pantin, 2011). Key Familias Unidas intervention targets include family functioning, a multi-dimensional construct made up of family communication, positive parenting and parental monitoring. Other intervention targets include parent stress and support for parents.

Existing studies show that Familias Unidas improves family functioning (Prado et al., 2007), which has been found to mediate the relationship between the intervention and youth behavioral health (see Prado & Pantin, 2011). Specifically, family communication is a mechanism by which Familias Unidas operates to reduce internalizing symptoms in youth with externalizing behavior problems (Perrino et al., 2016a; 2016b). Good family communication and similarity of views can promote positive mental health outcomes among adolescents, as can positive parenting practices, such as parental responsiveness and approval of youth (DeVore & Ginsburg, 2005; Garthe, Sullivan & Kliewer, 2015; Kerr & Stattin 2000; Sheeber et al., 2007; Yap & Jorm, 2015). Another component of positive family functioning is parental monitoring of children and their peer relations (Yap et al., 2016). Poor peer relationships increase risk for internalizing problems in adolescence, given peers’ importance during this life period (National Academies, 2019). Yet, when parents are involved and monitor their children appropriately, especially through communication, this can protect youth mental health (Hamza & Willoughby, 2011; Kerr and Stattin, 2000). Monitoring provides opportunities for parents to guide and support youth as they navigate peer challenges. Parents can also encourage social connectedness, which has protective effects on depression and anxiety (National Academies, 2019).

Alternative mechanisms by which Familias Unidas operates have yet to be tested, such as improvements in parents’ experiences of stress and support. Delivered through multi-family parent groups that can enhance support and buffer parenting and other stress, the intervention can bolster parents’ ability to practice positive parenting and strengthen family functioning (Prado & Pantin, 2011). Parents are more likely to engage in good parenting and report positive family functioning when their stress levels from different sources are low and when they receive social support (Ge et al, 1994; Lippold, Glatz, Fosco & Feinburg, 2018; Restifo & Bögels, 2009). Cultural stress in Hispanic immigrants can ultimately affect youth internalizing symptoms (Anderson & Mayes, 2010), while support is protective for parents (Ayón, 2011). Experiences of limited parental support and high parenting stress are related to poor child outcomes (Huang et al., 2014). One study of youth with externalizing behavior problems found that Familias Unidas was especially effective in reducing youth drug and sexual risk behaviors when parents had high stress and low social support (Prado et al., 2012). Yet, the intervention’s impact on parent stress and support in universal samples has not been examined, nor whether intervention-generated parental support and stress reductions influence youth internalizing symptoms.

Baseline target moderated mediation models (or BTMM) are an emerging analytic approach to address these consequential questions (Howe, Beach, Brody & Wyman, 2016). BTMM uses moderated mediation analyses to explore whether baseline levels of proximal intervention targets moderate the effect of the intervention on outcomes through the mediators. If proximal targets are assessed at baseline, and targets are malleable by the intervention, BTMM analyses can be used to identify for whom preventive interventions are most effective and how they operate, thereby informing efforts to optimize and strengthen interventions. First, BTMM results may point to compensatory effects where individuals who enter an intervention low on a target mediator make greater gains on the mediator, and thus benefit more from the intervention, than those who enter with moderate to high levels of the mediator (Howe, 2019). A second possible finding is that individuals already at moderate to high levels of the mediator further enhance their level of the mediator through intervention and experience greater overall benefits than those who are lower on the mediator, a case where the healthy become healthier. Finally, iatrogenic effects may be uncovered by BTMM analyses if findings show that individuals with high levels of a baseline mediator have poorer outcomes. A valuable extension of BTMM is “cascading mediation models,” where more than one intervention-targeted mediators are assessed in temporal sequence to elucidate intervention leverage points.

In this study, we conduct secondary data analyses to: 1) determine whether Familias Unidas has crossover effects on youth’s internalizing symptoms as tested in a universal, real-world setting (i.e. public schools) in youth presenting with a range of internalizing risks; and 2) using BTMM models, examine whether adolescents presenting with differing levels of family functioning, parent stress and social support for parents experience reductions in adolescent internalizing symptoms through distinct intervention-generated mechanisms. We hypothesize that exposure to Familias Unidas will result in decreased adolescent internalizing symptoms through improvements in family functioning, reductions in parent stress, and increases in social support for parents. We further hypothesize that youth with lower baseline family functioning, greater parental stress and lower social support for parents will benefit more from the intervention through improvements in these intervention mechanisms, consistent with the compensatory model noted above. Where there is evidence of BTMM, we conduct post-hoc analyses to examine cascading mediators by which the intervention works for those showing different baseline intervention needs. Findings inform whether and how this intervention promotes youth mental health. Results also demonstrate the potential that BTMM analyses hold to strengthen preventive interventions, as well as methodological challenges to attend to.

Method

Research Design

This research is a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial of the Familias Unidas intervention which took place from September 2010 to June 2014 (Estrada et al., 2017). Participants were followed for nearly three years. In an effectiveness trial like this one, intervention effects are examined in a real-world setting, without the controls of an efficacy trial (Gartlehner et al., 2006). The intervention was delivered through the public school system by school mental health personnel. Adolescents were eligible for the study if they: identified as being of Hispanic origin, were in eighth grade at baseline, lived with an adult primary caregiver who was willing to participate, lived within the catchment areas of the participating schools, and planned to live in South Florida for the entire study period.

Adolescents and their parents were recruited and randomized to a control or intervention condition. We used stratified randomization within the schools to balance the two condition groups with respect to gender and risky behaviors (i.e., lifetime illicit drug use and lifetime sexual activity). The control condition involved “prevention as usual,” the standard education and services available to Miami-Dade County Public School students; these consisted of six lessons focused on HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections. Science teachers delivered the lessons in the control condition. The three-month intervention for the experimental condition was delivered through eight parent group sessions comprised of 12-15 parents per group, and four family sessions with parents and youth that took place in the evenings at school (Table 1). Utilizing the Ecodevelopmental Model (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999) and a participatory learning approach, parents learn from each other and offer mutual support to become empowered to work with their adolescents about preventing health risks such as drug use and sex without a condom. Sessions address strengthening family functioning, including family communication, positive parenting practices, and monitoring. Parents are encouraged to exchange contact information and create a support network with group members. A description of the intervention has been published (e.g., Estrada et al., 2017). The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Miami’s Institutional Research Board (IRB), and the Miami Dade County School’s Research Board. Parents provided informed consent and adolescents provided assent to participate.

Table 1.

Familias Unidas Session Outline

| Family Session #1 | Engagement and Orientation |

| Group Session #1 | Family Functioning: Parental Investment in Adolescent Worlds |

| Group Session #2 | Family Functioning: Enhancing Communication Skills |

| Family Session #2 | Family Communication |

| Group Session #3 | Family Functioning: Family Support and Behavior Management |

| Group Session #4 | Family Functioning: Parental Monitoring of Peer World |

| Group Session #5 | Adolescent Substance Use: Attitudes, Beliefs, Intentions & Peer Pressure |

| Family Session #3 | Family Functioning: Parental Monitoring of Peer World and Adolescent Substance Use |

| Group Session #6 | Family Functioning – Parental Investment in Adolescent’s School |

| Group Session #7 | Adolescent Risky Sexual Behavior: Attitudes, Beliefs, Intentions & Peer Pressure |

| Family Session #4 | Adolescent Risky Sexual Behavior |

| Group Session #8 | Prevention Has To Be Achieved All Over Again Everyday |

Participants were assessed at baseline, 6-, 18- and 30-months post-baseline, with parents compensated $40, $45, $50, and $55, respectively, for each assessment completed. Adolescents were compensated one, two, three, and four movie tickets, respectively, for each assessment completed. All follow-up assessments occurred after completion of the intervention.

Participants

A total of 746 adolescent and parent dyads participated in the trial. Adolescents had a mean age of 13.8 years (SD = 0.66). Approximately 48% were girls and 45% were born outside the U.S. For parents, the mean age was 41 years (SD = 6.3). Nearly 83% of parents were women, 88% were born outside the U.S., and 68% had annual family incomes below $30,000.

Measures

Socio-demographics.

Adolescents and parents were asked their age, gender and country of birth. Parents also responded to questions about annual family income.

Adolescent internalizing symptoms (outcome variable).

The internalizing subscale of the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach, 1991) was used to assess internalizing symptoms during the prior 6 months. This 30-item subscale is a self-report measure with a three-point Likert scale for each item ranging from 0 (Not True), 1 (Somewhat or Sometimes True), or 2 (Very True or Often True). The internalizing problems variable is the sum of three subscales: 1) anxious-depressed (α = .86 at baseline), 2) withdrawn (α= .78 at baseline), and 3) somatic complaints (α = .82 at baseline). Possible scores ranged from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating greater internalizing symptoms. Prior research has found generalizability of YSR scores across cultures and high concurrent validity with measures of depressive symptoms (de Groot, Koot, & Verhulst, 1996).

Family Functioning was assessed using a single latent variable created from the following three parent-reported measures:

Family communication was measured with a three-item scale from the Family Relations Scale assessing communication and perceived similarity of views with one’s family members (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1997). Responses were scored on a 4-point scale from 0 = Not at all True to 3 = Almost Always or Always True. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.68.

Positive parenting was measured using a 9-item subscale from the Parenting Practices Scale that assesses parent responses to youth behaviors and positive parenting practices (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, Huesmann, 1996). Responses were scored on a 5-point response scale from 0 = Never to 4 = Always. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is 0.71.

Parental monitoring was measured with a 5-item scale assessing parental monitoring, youth supervision and parent relations with peers (Pantin, 1996). Responses were scored on a 5-point scale from 0 = Not at All to 4 = Extremely often. The scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86.

Parent Stress was assessed using parent reports on the Hispanic Stress Inventory (Cervantes et al., 1991). Questions consisted of two parts including whether the person has experienced a particular situation and if so, the degree of stress/tension that was felt as a result of that situation. For the current analyses, only the first part of the questions was utilized. The sum score consisted of 25 items (range of 0 – 25) which evaluates the experience of cultural, family, marital, immigration and economic/ occupational stressors in the last 3 months. Response options were 0= No and 1 = Yes. The scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75.

Social Support for Parents was assessed with the Social Provisions Scale, a 12-item parent measure that assesses five dimensions of social support, including guidance, reliable alliance, reassurance of worth, attachment, and social integration (Russell et al., 1984). Questions focus on support from friends, family, and a special person. Responses were rated on a seven-point scale scored from 1 = Very strongly disagree to 7 = Very strongly agree. The items were summed to create a single support score. The scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93.

Analysis Plan

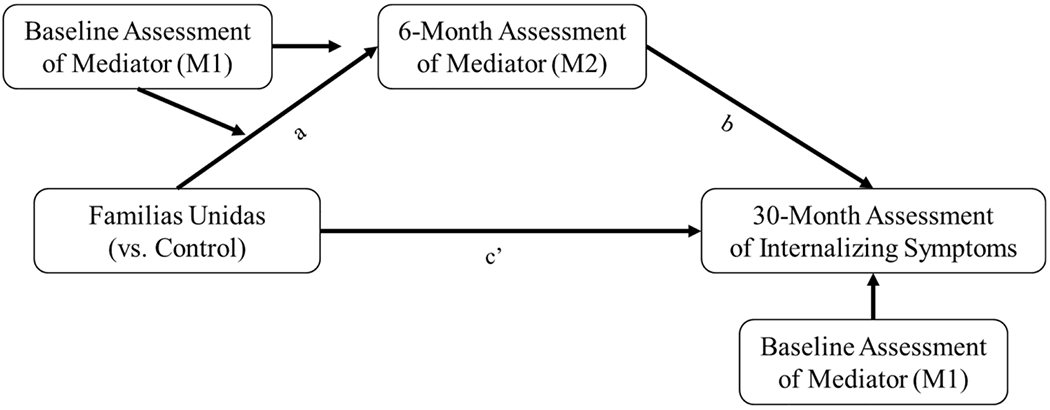

Analyses began with statistical comparisons across the two intervention conditions (Familias Unidas vs. Control) to confirm there were no baseline differences on internalizing symptoms, family functioning, parent stress, and support for parents. We then estimated total effect of the intervention on the adolescent internalizing symptom outcome by regressing the outcome on intervention condition. Structural equation models were used to estimate the BTMM model in Figure 1 for each of the hypothesized mediators: family functioning, parent stress, and social support for parents. All models involving internalizing symptoms were adjusted for gender to reduce variance in the outcome due to known gender differences (girls = 1, boys = 0; Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003). Model fit for the BTMM, where available, was considered adequate when CFI > 0.95 and RMSEA < .06 (Hu & Bender, 1999). Tests of the intervention by mediator interaction were also conducted to identify the presence of separate ‘b’ path effects for intervention and control conditions under the potential outcomes causal mediation framework (MacKinnon, Valente, & Gonzalez, 2020). Full information maximum likelihood was used throughout so that all available data were included in the analyses. Retention from baseline to 30 months was 83% on the primary outcome (adolescent internalizing symptoms) and 94% on the parent measures (baseline to 6 months). There was no evidence of significant differential attrition by intervention assignment on parent or adolescent measures. All analyses were conducted using Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017).

Figure 1.

Baseline Target Moderated Mediation Model

Results

There were no significant differences across intervention conditions at baseline for social support for parents (t = −1.74, p = .08), parent stress (t = 1.55, p = .12), internalizing symptoms (t = 0.17, p = .86), parental monitoring (t = 0.26, p = .79) or positive parenting (t = 1.64, p = .10). The baseline mean value of family communication was higher among control participants (t = −2.19, p = .03). However, the regression of the latent variable for family functioning (made up of family communication, parental monitoring and positive parenting measures) on intervention condition was not statistically significant (b = 0.017,p = 0.84), suggesting no mean difference on the family functioning latent variable. Previous research using these data show the two intervention conditions were balanced on other covariates as well (Estrada et al., 2017). The baseline distributions were predominantly skewed toward higher levels of family functioning and social support for parents, and lower levels of parent stress, representative of a universal sample.

Total effects.

Familias Unidas did not have a significant total effect on adolescent internalizing symptoms at 30 months relative to control condition (b = 0.60, p = .40).

Family functioning.

The association between intervention condition and six-month latent family functioning (a-path) demonstrated a positive, significant association between Familias Unidas and family functioning relative to the control condition (b = 0.19, p < .001). When controlling for baseline family functioning, gender and the intervention, six-month family functioning had a negative, non-significant association with adolescent internalizing symptoms at 30 months (b = −4,58, p = .51; b-path). However, the standard error on the b-path was very large (SE = 6.94). The correlation between baseline and six-month latent family functioning was very high (r = 0.89), likely contributing to the elevated standard error in the model. Model 1a (Table 2) shows the BTMM results without regressing the outcome on baseline family functioning. In this model, the b-path was statistically significant (b = −1.97, p < .01) and had a smaller standard error (SE = 0.72). There was no evidence of a significant intervention by mediator interaction. The findings from Model 1a are consistent with previous studies of Familias Unidas showing evidence of a significant indirect effect of Familias Unidas on internalizing symptoms through family communication (Perrino, et al., 2016a; 2016b). Baseline levels of family functioning did not moderate the association between intervention condition and six-month family functioning in either model, so the BTMM hypothesis was not supported.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the Baseline Target Moderated Mediation Models

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Model 1: Family Functioning | Model 1a: Family Functioning | Model 2: Parent Stress | Model 3: Social Support | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| b | SE | p | b | SE | P | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | ||

| M2 | Intervention (a) | 0.19 | 0.05 | < .001 | 0.19 | 0.05 | < .001 | −0.60 | 0.38 | .12 | 9.19 | 4.40 | .04 |

| M1 | 0.93 | 0.11 | < .001 | 0.90 | 0.08 | < .001 | 0.60 | 0.05 | < .001 | 0.70 | 0.05 | < .001 | |

| Intervention*M1 | −0.15 | 0.13 | .27 | −0.12 | 0.10 | .25 | 0.08 | 0.06 | .14 | −0.13 | 0.06 | .03 | |

| Y | Intervention (c’) | 1.42 | 1.50 | .35 | 0.94 | 0.70 | .18 | 0.53 | 0.71 | .45 | 0.52 | 0.71 | .47 |

| M2 (b path) | −4.58 | 6.94 | .51 | −1.97 | 0.72 | < .01 | 0.06 | 0.13 | .67 | −0.07 | 0.04 | .04 | |

| M1 | 2.45 | 6.35 | .70 | -- | -- | -- | 0.11 | 0.13 | .37 | 0.03 | 0.04 | .50 | |

| Gender | 3.22 | 0.70 | < .001 | 3.20 | 0.71 | < .001 | 3.14 | 0.71 | < .001 | 2.98 | 0.71 | < .001 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| R2 for M2 | 0.84 | 0.13 | < .001 | 0.81 | 0.09 | > .001 | 0.45 | 0.03 | < .001 | 0.37 | 0.03 | < .001 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| R2 for Y | 0.07 | 0.05 | .18 | 0.06 | 0.02 | .01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | .01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | .01 | |

Note. Bolded values are significant at p < .05. M2 is the mediator at 6 months. M1 is the mediator at baseline. Model fit: Model 1: CFI and SRMR are not available due to interaction terms involving latent variables. Model 2: CFI = 1.000, SRMR = 0.008, RMSEA = < .0001. Model 3: CFI = 0.993, SRMR = 0.012, RMSEA = 0.04. Gender is coded 1 for males, 2 for females.

Parent stress.

Model fit for the BTMM with parent stress as the mediator was good (CFI = 1.000; RMSEA < 0.001; SRMR = 0.01; Table 2). The direct effect of intervention condition on six-month parent stress (a-path) was not statistically significant (b = −0.60, p = .12), and was not moderated by baseline parent stress (b = 0.08, p = 0.14). Six-month parent stress was not associated with 30-month adolescent internalizing symptoms (b-path; b = 0.06, p = .67). Thus, the BTMM hypothesis was not supported for parent stress.

Social support for parents.

The BTMM structural equation model with social support for parents as the mediator had good fit (CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.01; Table 2). Baseline social support for parents significantly moderated the path between intervention condition and six-month social support for parents (b = −0.13, p = .03). Six-month social support for parents had a negative, significant effect on 30-month adolescent internalizing symptoms (b = −0.07, p = .04; b-path). There was no evidence of a significant intervention by mediator interaction. We used the Johnson-Neyman technique to probe the interaction for both the path from intervention condition to six-month social support for parents (moderated a-path), and the full indirect effect of intervention condition to 30-month adolescent internalizing through social support for parents (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). Figure 2a demonstrates that the association between intervention condition and six-month social support for parents is most positive and significantly different from zero at the lowest levels of baseline social support for parents, consistent with the BTMM compensatory hypothesis. Figure 2b shows the indirect effect of the intervention on internalizing symptoms through social support for parents is most negative at the lowest levels of social support for parents, again consistent with the compensatory hypothesis. The confidence intervals for this indirect effect included zero across the range of baseline social support values represented in the data.

Figure 2. Plots of (a) the direct effect of intervention condition on six-month parent social support and (b) the indirect effect of intervention condition on 30-month internalizing through six-month parent social support.

Note. Straight lines in the middle of the figure represent the parameter estimate; curved lines represent the 95% confidence interval around the parameter estimate.

Post-hoc analyses.

In post-hoc analyses, we considered whether parental monitoring at 18-months operated as a mechanism through which improvements in social support for parents influenced adolescent internalizing symptoms. There was evidence for parental monitoring as a distal mediator between six-month social support for parents and 30-month adolescent internalizing symptoms. Six-month social support for parents was positively and significantly associated with 18-month parental monitoring (b = 0.07, p < .001). Parental monitoring at 18-months was negatively and significantly associated with adolescent internalizing symptoms at 30 months (b = −0.28, p < .001) controlling for gender, intervention condition, and 18-month parent social support. This suggests a possible cascading of mediation effects for Familias Unidas.

Discussion

This study found that Familias Unidas delivered in a universal, real-world setting had crossover effects on youth internalizing symptoms, reducing these symptoms through its positive influence on family functioning. Application of the emerging analytic methods of baseline target moderated mediation (BTMM) and cascading mediation analyses allowed a deeper understanding of the intervention’s effects. These showed evidence that among families in which parents experienced low social support, the intervention impacted youth internalizing symptoms through increasing parent social support. Moreover, improvements in support for parents strengthened parental monitoring of youth, eventually reducing youth internalizing symptoms. Both the substantive and methodological findings have the potential to improve preventive interventions and address mental health in vulnerable adolescents, such as Hispanics.

The Substantive Research Question.

As noted, analyses of this universal effectiveness trial indicate that compared with control families, youth participating in Familias Unidas benefited from the intervention by showing decreased internalizing symptoms. These benefits occurred through the indirect effect of the intervention via improved family functioning. This is consistent with findings from prior Familias Unidas efficacy trials of youth with externalizing problems (Perrino et al., 2016a; 2016b), and further supports the centrality of positive family functioning for youth mental health (Restifo & Bögels, 2009; Yap & Jorm, 2015). Addressing this malleable, common protective factor for youth behavioral health through universal interventions is warranted to promote broad reach of the intervention and potentially reduce mental health disparities (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Yoshikawa, Aber & Beardslee, 2012).

Building on these overall findings, the BTMM analyses offer a more fine-grained understanding of how Familias Unidas operates for those presenting with specific intervention needs. The significant effect of the intervention on youth internalizing symptoms through family functioning was not moderated by baseline family functioning levels. Thus, all families, regardless of their initial family functioning, benefitted from intervention-generated gains in family functioning, suggesting this intervention should be delivered universally.

However, reductions in parent stress, a second mechanism through which Familias Unidas was expected to work, did not mediate the effects of the intervention on youth internalizing symptoms. Exposure to the intervention was not associated with levels of parent stress at six months, and effects did not vary by initial levels of parent stress. This absence of intervention impact on parent stress, even for high stress families, may be related to the fact that some sources of stress are not targeted by the intervention, for example, economic stress. The intervention focuses on reducing parenting stress and on buffering the effects of stress through social support. The study’s stress measure provides a global score encompassing cultural, economic, family, and other forms of stress. Quite possibly, a domain-specific approach focusing on intervention-targeted parenting stress may have yielded different results.

The findings provide some evidence that baseline social support for parents moderated the effect of the intervention on youth internalizing symptoms at 30-months through improvements in social support for parents at six-months, demonstrating a compensatory effect. That is, parents initiating Familias Unidas with lower levels of social support reported greater post-intervention gains in support. Subsequently, levels of six-month parent social support were associated with lower youth internalizing symptoms at 30-months. This finding is in line with research that parents who feel supported are better able to parent compared to those lacking support (Lippold, Glatz, Fosco & Feinberg, 2018; Byrnes & Miller, 2012). A group-delivered intervention like Familias Unidas can help enhance social support networks, which are invaluable for immigrant and disadvantaged parents. Doing so can help diminish internalizing symptoms in youth. It makes sense that promoting social connectedness would benefit parents lacking support yet would not impact those who already have supports in place. Interventionists may consider screening parents on support at program start and helping participants develop sustainable support networks that continue post-intervention. A precision prevention approach (August & Gewirtz, 2019) might consider monitoring levels of parent social support throughout the intervention, offering additional interventions to those with suboptimal support to ensure they make the gains needed to realize beneficial long-term outcomes.

Post-hoc analyses allowed further specification of how the intervention operates temporally to promote youth mental health in families showing initial specific intervention needs. These revealed a cascading effect that extended the impact of social support for parents to their improved ability to monitor their children. As before, among families in which parents were initially low on social support, Familias Unidas improved support at 6-months. Higher levels of social support were then associated with higher levels of youth monitoring at eighteen-months, and ultimately higher levels of parental monitoring were associated with lower levels of youth internalizing symptoms at thirty-months. In other words, when parents experienced more support, they were more likely to monitor adolescents and their peer relationships, which was ultimately associated with lower internalizing symptoms among youth.

Support for parents is important, especially among immigrant, socio-economically disadvantaged parents (Ayón, 2011). Moreover, monitoring youth has important implications for youth internalizing symptoms (Kerr & Stattin, 2010). Balanced parenting styles that include warmth, structure, and appropriate monitoring have been linked to better youth mental, behavioral and emotional outcomes (Garthe, Sullivan & Kliewer, 2015; Restifo & Bögels, 2009; Yap & Jorm, 2015). It is noteworthy that child monitoring can involve both individual and collective efforts (Byrnes & Miller, 2012). This intervention may improve individual skills or activate individual motivation to monitor but may also increase collaboration with other parents in child monitoring. Future trials would benefit from tracking both individual and collective monitoring to determine how each contributes to greater impact.

Study Limitations.

The findings are subject to several limitations. First, self-reported measures are potentially influenced by bias. Though latent variables (e.g., family functioning) adjust for some forms of measurement error, observed measures may have error despite meeting accepted measurement criteria. Second, lack of random assignment to the level of the mediator limits our ability to draw strong causal conclusions about the intervention’s effect on the outcome through the mediator. In most models, we were able to adjust for the baseline mediator as a proxy control for historical confounds. Third, although we met the joint significance criteria for mediation (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002) through social support among parents reporting low support at baseline, the confidence intervals for the indirect effect contained zero at all levels of the baseline moderator. This highlights an important limitation for testing BTMM effects: under-representation of participants at extreme values on the baseline target can lead to weak hypothesis testing in that region of the distribution. Future studies may consider oversampling parents reporting lower levels of baseline social support to better understand the intervention impact for these parents. Despite these limitations, findings suggest important signals about this specific impact of Familias Unidas on parent and youth outcomes.

The Application of Emerging Methods.

Baseline targeted moderated mediation studies such as this one probe intervention mechanisms of action to help us better understand whether vulnerable youth and families respond to interventions differently based on their initial level of the intervention target. When supported, compensatory BTMM hypotheses enhance our understanding of intervention mechanisms by demonstrating the intervention’s effectiveness at improving levels of the target mediator, triggering beneficial long-term outcomes for families who need it the most. Support for compensatory BTMM hypotheses also underline the importance of ensuring participants are acquiring the required levels of the intervention’s mediators or “active ingredients.” For instance, precision prevention approaches that monitor a family or individual’s level of the mediator during the course of the intervention can allow adjustments or augmentation to the intervention if needed to help participants obtain the proper level of the mediator to ensure optimum long-term outcomes. This could be done through a priori protocols such as adaptive interventions empirically derived from sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (Lei, Nahum-Shani, Lynch, Oslin, & Murphy, 2012).

The ability to address BTMM research questions may be limited by under-representation of participants with extreme values of the target variable at baseline. Thus, researchers intending to examine BTMM hypotheses should ensure samples include participants representing all levels of the intervention target at baseline. Additionally, as was demonstrated here with family functioning, when participants begin the intervention with high baseline levels of the target mediator, there is little room for improvement or change on the mediator. The resulting high correlations between baseline and post-intervention assessment of the mediator can lead to issues of multicollinearity for the outcome model and make it difficult to test the b-path of the mediation model. Finally, cascading mediation models such as this study’s post-hoc analyses represent one of many possible extensions to the BTMM model that may further enhance the optimization of preventive interventions to best meet youth needs.

Conclusion.

Familias Unidas was beneficial in reducing internalizing symptoms among Hispanic youth in this universal effectiveness trial through intervention-generated improvements in family functioning. This is important because Hispanic and disadvantaged youth are at elevated risk of internalizing symptoms and poor longer-term outcomes (Anderson & Mayes, 2010). The fact that the intervention showed a crossover effect on internalizing symptoms in a real-world setting is consequential. It demonstrates that communities can effectively implement these interventions to promote diverse aspects of youth mental, emotional and behavioral health. The fact that this occurred in a universal setting suggests interventions can influence adolescents, irrespective of risk level, during a key period for the development of mental health problems. Screening parents for social support, monitoring improvements in support during intervention, and ensuring sustainability of supportive social networks is especially important for these parents in helping protect their adolescents from poor mental health. Findings suggest that delivering this intervention to universal samples is a worthwhile approach to enhancing resilience of at-risk youth during this sensitive period of mental health risks.

Funding.

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant # K01 DA046516 (Ahnalee Brincks, Principal Investigator) and grant # R01 DA025192 (Guillermo Prado, Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Ethics Approval. This study represents a secondary analysis of data that was obtained through a study approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards indicated by the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and amendments that followed.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest nor competing interests.

Consent to Participate: As noted in the manuscript, parents provided informed consent and adolescents provided assent to participate.

References

- Achenbach TMC (1991). Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, & Mayes LC (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 338–348. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, & Gewirtz A (2019). Moving toward a precision-based, personalized framework for prevention science: Introduction to the special issue. Prevention Science, 20(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C (2011). Latino families and the public child welfare system: Examining the role of social support networks. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(10), 2061–2066. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.05.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Gladstone TRG, Wright EJ, & Cooper AB (2003). A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: Evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics, 112(2), e119–e131. 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertha EA, & Balasz J (2013). Subthreshold depression in adolescence: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22, 589–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes HF, & Miller BA (2012). The relationship between neighborhood characteristics and effective parenting behaviors: The role of social support. Journal of Family Issues, 33(12), 1658–1687. 10.1177/0192513X12437693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, & Salgado de Snyder N (1991). The Hispanic Stress Inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3(3), 438–447. 10.1037/1040-3590.3.3.438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot A, Koot H, & Verhulst F (1996). Cross-cultural generalizability of the youth self-report and teacher’s report form cross-informant syndromes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24(5), 651–664. 10.1007/BF01670105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVore ER, & Ginsburg KR (2005). The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 17(4), 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada Y, Lee TK, Huang S, Tapia MI, Velázquez MR, Martinez MJ, Pantin H, Ocasio MA, Vidot DC, Molleda L, Villamar J, Stepanenko BA, Brown CH, & Prado G (2017). Parent-centered prevention of risky behaviors among Hispanic youths in Florida. American Journal of Public Health, 107(4), 607. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthe R, Sullivan T, & Kliewer W (2015). Longitudinal relations between adolescent and parental behaviors, parental knowledge, and internalizing behaviors among urban adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(4), 819–832. 10.1007/s10964-014-0112-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Nissman D, Lohr KN, & Carey TS (2006). A simple and valid tool distinguished efficacy from effectiveness studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 59(10), 1040–1048. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GH, & Simons RL (1994). Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 30(4), 467–483. 10.1037/0012-1649.30.4.467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, & Huesmann LR (1996). The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(2), 115–129. 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza C, & Willoughby T (2011). Perceived parental monitoring, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(7), 902–915. 10.1007/s10964-010-9604-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GW (2019). Using baseline target moderation to guide decisions on adapting prevention programs. Development and Psychopathology, 31(5), 1777–1788. doi: 10.1017/S0954579419001044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GW, Beach SRH, Brody GH, & Wyman PA (2016). Translating genetic research into preventive intervention: The baseline target moderated mediator design. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1911–1911. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Costeines J, Kaufman J, & Ayala C (2014). Parenting stress, social support, and depression for ethnic minority adolescent mothers: Impact on child development. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 255–262. 10.1007/s10826-013-9807-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, & Stattin H (2000). What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology, 36(3), 366–380. 10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H, Nahum-Shani I, Lynch K, Oslin D, & Murphy SA (2012). A “SMART” design for building individualized treatment sequences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 14.1–14.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold MA, Glatz T, Fosco GM, & Feinberg ME (2018). Parental perceived control and social support: Linkages to change in parenting behaviors during early adolescence. Family Process, 57(2), 432–447. 10.1111/famp.12283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological methods, 7(1), 83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Valente MJ, & Gonzalez O (2020). The correspondence between causal and traditional mediation analysis: The link is the mediator by treatment interaction. Prevention Science, 21(2), 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2017). Mplus User’s Guide. In (Eighth Edition ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/25201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H (1996). Ecodevelopmental measures of support and conflict for Hispanic youth and families. Miami, FL: University of Miami School of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Brincks A, Howe G, Brown C, Prado G, & Pantin H (2016a). Reducing internalizing symptoms among high-risk, Hispanic adolescents: Mediators of a preventive family intervention. Prevention Science, 17(5), 595–605. 10.1007/s11121-016-0655-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Pantin H, Huang S, Brincks A, Brown CH, & Prado G (2016b). Reducing the risk of internalizing symptoms among high-risk Hispanic youth through a family intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Family Process, 2016; 55, 91–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Pantin H, Prado G, Huang S, Brincks A, Howe G, Beardslee W, Sandler L, & Brown C (2014). Preventing internalizing symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: A synthesis across Familias Unidas trials. Prevention Science, 15(6), 917–928. 10.1007/s11121-013-0448-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of educational and behavioral statistics, 31(4), 437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Cordova D, Huang S, Estrada Y, Rosen A, Bacio GA, Leon Jimenez G, Pantin H, Brown CH, Velazquez MR, Villamar J, Freitas D, Tapia MI, & McCollister K (2012). The efficacy of Familias Unidas on drug and alcohol outcomes for Hispanic delinquent youth: Main effects and interaction effects by parental stress and social support [Supplement]. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 125(Supplement 1), S18–S25. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, & Pantin H (2011). Reducing substance use and HIV health disparities among Hispanic youth in the USA: the Familias Unidas program of research. Psychosocial Intervention, 20(1), 63–73. 10.5093/in2011v20n1a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restifo K, & Bögels S (2009). Family processes in the development of youth depression: Translating the evidence to treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(4), 294–316. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Cutrona CE, Rose J, & Yurko K (1984). Social and emotional loneliness: An examination of Weiss’s typology of loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6), 1313–1321. 10.1037/0022-3514.46.6.1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, & Coatsworth JD (1999). An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz MD, Hartel CR (Eds.), Drug Abuse: Origins & Interventions. APA, Washington, DC, 331–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Davis B, Leve C, Hops H, & Tildesley E (2007). Adolescents’ relationships with their mothers and fathers: Associations with depressive disorder and subdiagnostic symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 144–154. 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesman LR, & Zelli A (1997). Assessment of family relationship characteristics: A measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychological Assessment, 9(3), 212–223. 10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MBH, & Jorm AF (2015). Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalizing problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 424–440. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MB, Morgan AJ, Cairns K, Jorm AF, Hetrick SE, & Merry S (2016). Parents in prevention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of parenting interventions to prevent internalizing problems in children from birth to age 18. Clinical Psychology Review, 50, 138–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, & Beardslee WR (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth. American Psychologist, 67(4), 272–284. 10.1037/a0028015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]