Abstract

Major depression is an episodic disorder which, for many individuals, has its onset in a distinct change of emotional state which then persists over time. The present article explores the utility of combining a dynamical systems approach to depression, focusing specifically on the change of state associated with episode onset, with a self-regulation perspective, which operationalizes how feedback received in the ongoing process of goal pursuit influences affect, motivation, and behavior, for understanding how a depressive episode begins. The goals of this review are to survey the recent literature modeling the onset of a depressive episode and to illustrate how a self-regulation perspective can provide a conceptual framework and testable hypotheses regarding episode onset within a dynamical systems model of depression.

Introduction

Major depression continues to pose a substantial public health challenge, in terms of mortality, morbidity/comorbidity, and societal costs [1]. Yet as new perspectives on psychopathology emerge, their application to specific disorders can lead to insights for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention [2,3]. Dynamical systems and network models of psychiatric disorders provide a rich context for mechanism-focused experimental research, with the dual purpose of increasing our understanding of each disorder and then translating new findings into effective interventions [4,5]. The goals of this brief review are to survey the recent literature modeling the onset of a depressive episode and to illustrate how a self-regulation perspective can provide a conceptual framework and testable hypotheses regarding episode onset within a dynamical systems model of depression. With the increased availability of experience sampling and neuroimaging data in addition to behavioral, self-report, and clinician assessments, it may be possible to advance our understanding of depression through application of models and data-analytic technologies that can account for both linear and nonlinear/reciprocal causal influences [6,7].

Dynamical systems and network models of depression

The episodic nature of depression requires an approach to etiology that can account for the qualitative change in state that individuals experience as they move into (and out of) a depressive episode [8], ideally so that intervention can be provided before that transition occurs [9]. Dynamical systems and network models of psychopathology emphasize that psychiatric disorders can be construed as organized collections or networks of elements or symptoms that, once instantiated, tend to maintain themselves [10,11]. These models characterize mental disorders not as collections of symptoms per se, but as dynamic patterns of associations among symptoms that have both a logical and temporal structure [12]. Networks characteristically maintain a coherent and stable state, and some energy or disruption is required to cause a shift into a different (and also potentially stable) state [13]. Thus, the conceptual challenge is to identify the factors that lead to a change in state culminating in a depressive episode – specifically, from euthymic to dysthymic [14,15]. In traditional models of etiology, some combination of diatheses and stressors causes a disorder called depression, which then causes symptoms. From a systems perspective, stressors trigger reactions and symptoms that in turn activate other symptoms, potentially leading to a change in state that itself is the disorder [16].

Epidemiological and experimental data consistently show that a majority of individuals who have met diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode experienced a relatively discontinuous change in mood, motivation, and behavior as an episode begins [17]. This pattern, in turn, suggests the possibility of a state transition within a dynamic system. Such a system is composed of multiple interacting nodes or elements whose associations vary in strength and direction of influence over time. The system becomes vulnerable to a transition from a stable adaptive state to a stable dysphoric/maladaptive state after sufficient perturbation from one or more stressors [18,19]. There also is evidence that response to treatment for depression often follows a similar discontinuous transition pattern [20]. However, this depressive-onset-as-phase-transition hypothesis has been challenging to test experimentally, in part because doing so requires clear operationalization of a target brain/behavior system within which to observe such transitions, as well as controlled manipulations which approximate cumulative or catastrophic stress [21].

Recent applications of dynamical systems and network theories to depression suggest that human brain/behavior systems, particularly those involved in motivation and mood regulation, are characteristically stable but can become less so under chronic or intense stress [22]. This principle is illustrated by the familiar notion of a tipping point [23]. In the context of depression, brain-behavior systems, when exposed to a gradual increase in stress over time, may undergo a relatively abrupt shift into a qualitatively distinct state in which mood and motivation stabilize at a dysfunctional level (dysphoric mood, inadequate approach motivation) [24]. This shift from a euthymic to a dysthymic state, termed critical slowing down, is both descriptive (denoting a clinical presentation in which the individual manifests greater dysphoric affect, reduced goal pursuit, lower energy level, etc.) and technical (hypothesizing that the system’s capacity for adjustment to perturbation is diminished and the correlations among system elements/symptoms are increased) [25]. As was originally hypothesized five decades ago, depression can be construed as a functional disorder in which the behavioral, experiential, and neural mechanisms associated with reward sensitivity and reinforcement become hypoactive [26]. Given that these systems phenomena derive from properties of feedback loops, feedback-based theories of mood regulation and vulnerability may offer ways to operationalize key concepts and conduct robust experimental tests of the critical slowing down phenomenon in depression [27,28].

Depression and self-regulation

The concept of self-regulation is used in psychology and related disciplines to describe the processes by which people initiate, maintain, and control their own thoughts, behaviors, or emotions, with the intention of producing a desired outcome or avoiding an undesired outcome [29]. Self-regulation incorporates both genetically-based and learning-based mechanisms and operates in the pursuit of motivationally significant goals, notably approach and avoidance goals that lead to nurturance and security [30]. Regulatory focus theory (RFT) is a well-validated theory of human self-regulation that proposes two brain/behavior systems for goal pursuit, the promotion and prevention systems, which operate to maximize positive outcomes and minimize negative outcomes respectively [31]. Both behavioral and neuroimaging data support the assertion that the two systems are functionally discriminable and nonredundant with temperament-based systems for spatiotemporal approach and avoidance [32,33,34]. RFT has been applied to conceptualizing a broad range of self-regulation failures, including depression and related forms of internalizing psychopathology such as generalized anxiety disorder [35].

The construct of self-regulation offers a powerful conceptual basis for testing basic and translational hypotheses about psychopathology [36]. Although self-regulation models of depression are not always cast in dynamical systems terms, there are multiple correspondences which indicate the value of doing so [37]. For example, self-regulatory failure can be gradual/degenerative or abrupt/catastrophic, can be system-wide, and can occur across multiple types of adaptive functions [38]. A recently proposed self-regulation perspective on depression [39] offered four hypotheses regarding the disorder, drawing upon related feedback-loop models [40,41,42,43]: (a) depression results from cumulative or catastrophic failure of the individual’s neurobiological and psychological capacity for goal pursuit (specifically, promotion/“making good things happen”); (b) an initial episode of depression is a functional state resulting from a downward spiral of failure to make progress toward valued positive outcomes; (c) core symptoms of depression reflect dysregulation of approach/promotion (e.g., mood, appetite, anhedonia, energy, concentration, worthlessness, hopelessness, low self-esteem) or dysregulation of reciprocal inhibition between approach/promotion and avoidance/prevention (e.g., sleep disturbance, guilt, agitation/anxiety, HPA axis dysfunction); and (d) as episodes of depression accumulate, self-regulatory neural mechanisms may be permanently altered.

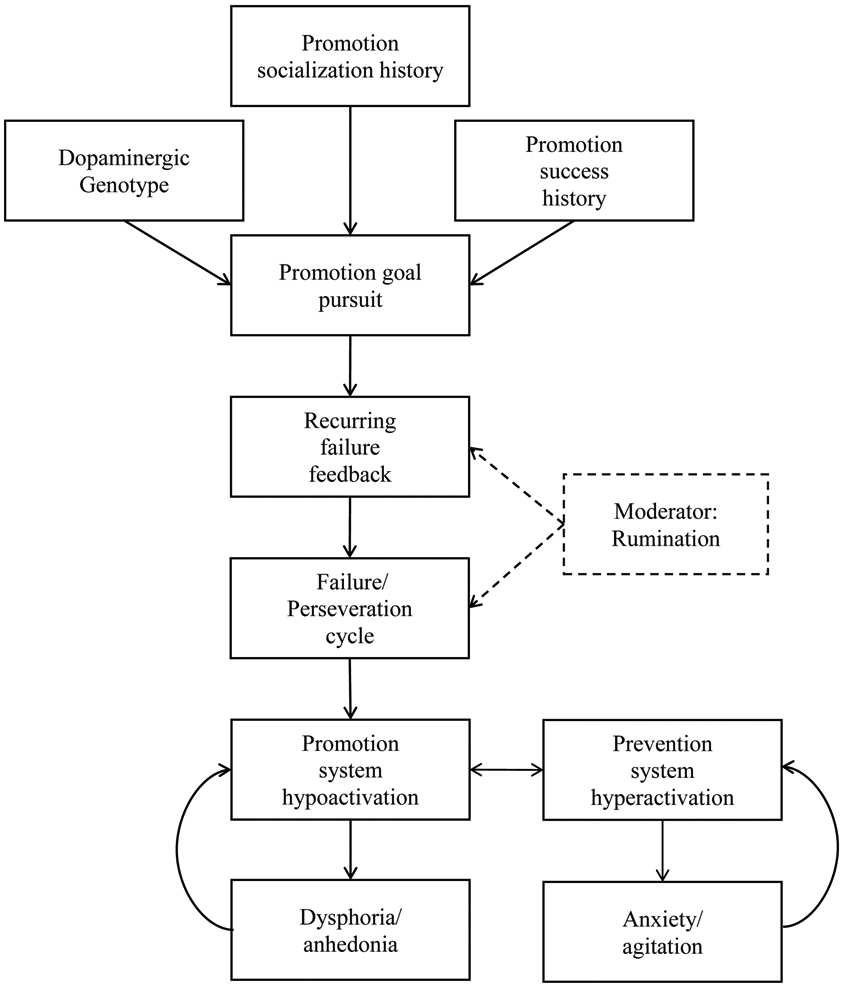

There is now substantial evidence linking self-regulatory dysfunction and depression. Research based on self-discrepancy theory indicates that when individuals experience chronic failure to attain a promotion (“ideal”) or prevention (“ought”) goal, they manifest a specific type of distress – dysphoria vs. anxiety respectively [44,45]. Similarly, research based on RFT indicates that clinically significant dysphoric and anxious states are associated with reliably identifiable dysfunctions within those motivational systems [46,47]. This research on RFT as an explanatory framework for depression has been extended into a model describing an etiological pathway to depression based on dysfunction of the promotion and prevention systems [48]. Specifically, for vulnerable individuals, chronic or catastrophic failure to make progress toward motivationally significant promotion goals (signified by recurring failure feedback) is hypothesized to induce a perseverative behavioral cycle that continues to engage the individual with failure feedback, ultimately leading to a change of state in the promotion system from active to hypoactive. Figure 1 depicts a model for promotion-system-mediated depressive vulnerability as a specific etiological pathway to a depressive episode. Based on the RFT postulate that the promotion and prevention systems operate in a mutually inhibitory manner, chronic down-regulation of promotion also is hypothesized to increase vulnerability to prevention system hyperactivation, in turn seen as a contributory factor for comorbid anxiety.

Figure 1:

A model for self-regulation as a contributory causal factor in the onset of unipolar depression (Strauman, 2017).

A self-regulation perspective on depressive episode onset

If chronic or catastrophic promotion goal pursuit failure represents a pathway to depression for individuals with specific premorbid characteristics (i.e., strong history of promotion goal pursuit socialization and success plus a dopaminergic genotype biasing reward sensitivity toward perseveration []), what might trigger or influence the hypothesized change in state of the promotion system from active to hypoactive? Research based on expectancy theory indicates that as the individual’s expectation of a positive outcome approaches zero (or some critical minimum value determined by current or historical contingencies), effort and persistence decrease precipitously [49]. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression incorporates this insight by focusing the client on the role of expectancies in both the onset and maintenance of a depressive episode [50]. Behavioral experimental research using RFT to explore the dynamics of promotion-based behavior leads to the prediction that continuous failure feedback should result in an initial increase in goal pursuit effort (while the system anticipates a sufficient likelihood of a positive outcome) followed by abrupt discontinuation of goal pursuit (when the individual’s expectancy goes below a critical threshold for the minimum required likelihood of a positive outcome) [51,52]. From this perspective, repeated assessment of an individual’s expectancy of a positive outcome for her/his promotion goal pursuit efforts may provide a readout of the extent to which the promotion system is shifting in the direction of a phase transition.

The hypothesized link from “Failure/perseveration cycle” to “Promotion system hypoactivation” seen in Figure 1 incorporates the general notion of a state change from feedback-based perseverative promotion goal pursuit efforts to hypoactivation/shutdown of goal pursuit. Can this hypothesized transition be experimentally manipulated, and does it represent an ecologically valid model for the onset of a depressive episode? Although the specific dynamics of that process have yet to be explored experimentally in analog or clinical samples, there is evidence in the behavioral literature that continued failure feedback leads to discontinuation of promotion goal pursuit [53,54]. There also is evidence in the psychotherapy literature that interventions targeting promotion system hypoactivation may be efficacious in the treatment of depression [55,56,57]. If the model in Figure 1 is valid, it should be possible (a) acutely, to intervene therapeutically before the failure feedback/perseverative goal pursuit cycle triggers a state transition to promotion system hypoactivation and accompanying dysphoric symptoms and (b) from a preventive intervention standpoint, to identify individuals at heightened risk for this hypothesized etiological pathway and provide them with cognitive and motivational skills to maintain adaptive promotion system function and avoid critical slowing down within that system.

A proof-of-concept study by Goetz and colleagues illustrates an experimental paradigm in which the critical slowing down phenomenon might be detectable within the context of promotion system response to continuing failure feedback [58]. Those authors used a probabilistic reward task [59] to examine the interaction between individual differences in strength of promotion and prevention orientation and a common functional genetic polymorphism impacting prefrontal dopamine signaling (COMT rs4680). They observed that having a strong promotion system predicted total response bias, but only for individuals with the COMT genotype (Val/Val) associated with relatively increased phasic dopamine signaling and cognitive flexibility. The experimental parameters of that study were not tuned to provide consistent failure feedback, or to shift from consistent success to consistent failure (as an approximation of life circumstances in which individuals who are accustomed to successful goal pursuit efforts begin to encounter greater difficulty). However, the same basic task and design could easily be adapted to incorporate all three of the premorbid characteristics hypothesized to predispose to promotion-system-mediated depression (dominant promotion system, high expectancy of success based on the individual’s reinforcement history, dopaminergic genotype biasing goal pursuit toward perseveration) and then observe the effects of shifting over multiple trials from initial success to increasing probability of failure.

Conclusion

The goals of this brief review were to survey the recent literature modeling the onset of a depressive episode and to illustrate how a self-regulation perspective can provide a conceptual framework and testable hypotheses within a dynamical systems model of depression. Improved modeling of depressive episode onset can set the stage for better prediction, earlier and more effective intervention, and ultimately, more broadly available preventive intervention strategies. As noted, the systems/network approach to depression already has demonstrated substantial implications for treatment, including the frequency with which response to psychological or pharmacologic interventions itself may be abrupt and nonlinear [60,61]. Self-regulation models of depression do not necessarily apply to all instances of unipolar depression, which is known to be highly heterogeneous in etiology as well as clinical presentation. Nonetheless, self-regulation represents a critical proximal locus for the effects of more distal risk factors on mood, motivation, and behavior [62]. Experimentally testable hypotheses such as those offered here may help to advance our understanding of depression’s origins, its dynamics, and its amelioration.

Acknowledgements:

This work has been supported by NIH grants DA031579, DA022569, MH039429, and DA023026, as well as funding from Bass Connections, the Social Science Research Institute, and the Office of the Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Research at Duke University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author of this manuscript reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

References and Recommended Reading

- 1.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, Grant BF. Epidemiology of Adult DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder and Its Specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018. April 1;75(4):336–346. PMID: 29450462. PMCID: PMC5875313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nemeroff CB. The State of Our Understanding of the Pathophysiology and Optimal Treatment of Depression: Glass Half Full or Half Empty? Am J Psychiatry. 2020. August 1;177(8):671–685. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060845. PMID: 32741287. *A thoughtful and comprehensive update on challenges for understanding the pathophysiology and treatment of unipolar depression, with a particular emphasis on treatment mechanisms of action.

- 3.Borsboom D, Cramer A, Kalis A. Brain disorders? Not really… Why network structures block reductionism in psychopathology research. Behav Brain Sci. 2018. January 24:1–54. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X17002266. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 29361992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson B, McGorry PD, Wichers M, Wigman JTW, Hartmann JA. Moving From Static to Dynamic Models of the Onset of Mental Disorder: A Review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017. May 1;74(5):528–534. PMID: 28355471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange J, Dalege J, Borsboom D, van Kleef GA, Fischer AH. Toward an Integrative Psychometric Model of Emotions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2020. March;15(2):444–468. doi: 10.1177/1745691619895057. Epub 2020 Feb 10. PMID: 32040935; PMCID: PMC7059206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Favela LH. Cognitive science as complexity science. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2020. July;11(4):e1525. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1525. Epub 2020 Feb 11. PMID: 32043728. * This article provides extensive background for investigators seeking to model human cognitive processes from a systems/network perspective.

- 7.Thomasson N, Pezard L. Dynamical systems and depression: a framework for theoretical perspectives. Acta Biotheor. 1999;47(3-4):209–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1002686604968. PMID: 10855268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes AM, Yasinski C, Ben Barnes J, Bockting CL. Network destabilization and transition in depression: New methods for studying the dynamics of therapeutic change. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015. November;41:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.007. Epub 2015 Jun 27. PMID: 26197726; PMCID: PMC4696560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreuder MJ, Hartman CA, George SV, Menne-Lothmann C, Decoster J, van Winkel R, Delespaul P, De Hert M, Derom C, Thiery E, Rutten BPF, Jacobs N, van Os J, Wigman JTW, Wichers M. Early warning signals in psychopathology: what do they tell? BMC Med. 2020. October 14; 18(1):269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borsboom D, Cramer AO. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:91–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608. PMID: 23537483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein EE, Kleiman EM, van Bork R, Moriarity DP, Mac Giollabhui N, McNally RJ, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Unique and predictive relationships between components of cognitive vulnerability and symptoms of depression. Depress Anxiety. 2019. October;36(10):950–959. doi: 10.1002/da.22935. Epub 2019 Jul 22. PMID: 31332887; PMCID: PMC6777955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robinaugh DJ, Hoekstra RHA, Toner ER, Borsboom D. The network approach to psychopathology: a review of the literature 2008-2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychol Med. 2020. February;50(3):353–366. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003404. Epub 2019 Dec 26. PMID: 31875792; PMCID: PMC7334828. **Perhaps the best review and summary to date of how network theory can be applied to the study of psychopathology, with particular emphasis on mood disorders.

- 13.Kalisch R, Cramer AOJ, Binder H, Fritz J, Leertouwer I, Lunansky G, Meyer B, Timmer J, Veer IM, van Harmelen AL. Deconstructing and Reconstructing Resilience: A Dynamic Network Approach. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019. September;14(5):765–777. doi: 10.1177/1745691619855637. Epub 2019 Jul 31. PMID: 31365841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kossakowski JJ, Gordijn MCM, Riese H, Waldorp LJ. Applying a Dynamical Systems Model and Network Theory to Major Depressive Disorder. Front Psychol. 2019. August 7;10:1762. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01762. PMID: 31447730; PMCID: PMC6692450. *The article provides a well-articulated model for predicting vulnerability to depression from the perspective of dynamical systems and network theories.

- 15.Hosenfeld B, Bos EH, Wardenaar KJ, Conradi HJ, van der Maas HL, Visser I, de Jonge P. Major depressive disorder as a nonlinear dynamic system: bimodality in the frequency distribution of depressive symptoms over time. BMC Psychiatry. 2015. September 18;15:222. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0596-5. PMID: 26385384; PMCID: PMC4574448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann SG, Curtiss J, McNally RJ. A Complex Network Perspective on Clinical Science. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2016. September;11(5):597–605. doi: 10.1177/1745691616639283. PMID: 27694457; PMCID: PMC5119747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wichers M, Schreuder MJ, Goekoop R, Groen RN. Can we predict the direction of sudden shifts in symptoms? Transdiagnostic implications from a complex systems perspective on psychopathology. Psychol Med. 2019. February;49(3):380–387. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718002064. Epub 2018 Aug 22. PMID: 30131079; PMCID: PMC6331686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cramer AOJ, van Borkulo CD, Giltay EJ, van der Maas HLJ, Kendler KS, Scheffer M et al. (2016). Major depression as a complex dynamical system. PLoS ONE 11:e0167490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wichers M, Groot PC, Psychosystems ESM Group, and ESW Group (2016). Critical slowing down as a personalized early warning signal for depression. Psychother. Psychosomat 85, 114–116. doi: 10.1159/000441458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hofmann SG, Curtiss JE, Hayes SC. Beyond linear mediation: Toward a dynamic network approach to study treatment processes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020. March;76:101824. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101824. Epub 2020 Jan 17. PMID: 32035297; PMCID: PMC7137783. *An outstanding review of how to apply dynamical systems models to studying course of treatment and mechanisms of action for psychological interventions.

- 21.Summers BJ, Aalbers G, Jones PJ, McNally RJ, Phillips KA, Wilhelm S. A network perspective on body dysmorphic disorder and major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020. February 1;262:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.011. Epub 2019 Nov 5. PMID: 31733461; PMCID: PMC6924632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patten SB (2013). Major depression epidemiology from a diathesis-stress conceptualization. BMC Psychiatry 13:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O’Brien E. When small signs of change add up: The psychology of tipping points. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2020;29(1):55–62. doi: 10.1177/0963721419884313 *A user-friendly introduction to the phenomenon of tipping points from a behavioral science perspective.

- 24.Wichers M, Lothmann C, Simons CJP, Nicolson NA, Peeters F (2012). The dynamic interplay between negative and positive emotions in daily life predicts response to treatment in depression: A momentary assessment study. Br J Clin Psychol 51(2): 206–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van de Leemput IA, Wichers M, Cramer AO, Borsboom D, Tuerlinckx F, Kuppens P, et al. Critical slowing down as early warning for the onset and termination of depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akiskal HS, McKinney WT Jr. Depressive disorders: toward a unified hypothesis. Science. 1973. October 5;182(4107):20–9. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4107.20. PMID: 4199732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuranova A, Booij SH, Menne-Lothmann C, Decoster J, van Winkel R, Delespaul P, De Hert M, Derom C, Thiery E, Rutten BPF, Jacobs N, van Os J, Wigman JTW, Wichers M. Measuring resilience prospectively as the speed of affect recovery in daily life: a complex systems perspective on mental health. BMC Med. 2020. February 18; 18(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-1500-9. PMID: 32066437; PMCID: PMC7027206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wittenborn AK, Rahmandad H, Rick J, Hosseinichimeh N. Depression as a systemic syndrome: mapping the feedback loops of major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2016. February;46(3):551–62. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002044. Epub 2015 Dec 1. PMID: 26621339; PMCID: PMC4737091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoyle RH, Gallagher P. 2015. The interplay of personality and self-regulation. In APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Vol. 4, Personality processes and individual differences, ed. Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Cooper ML, Larsen RJ, 189–207. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Struk AA, Mugon J, Huston A, Scholer AA, Stadler G, Higgins ET, Sokolowski MB, Danckert J. Self-regulation and the foraging gene (PRKG1) in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019. March 5;116(10):4434–4439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809924116. Epub 2019 Feb 19. PMID: 30782798; PMCID: PMC6410783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins ET. (1998). Promotion and prevention: regulatory focus as a motivational principle, in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 30, ed Zanna MP, editor. (New York, NY: Academic Press;), 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Detloff AM, Hariri AR, Strauman TJ. Neural signatures of promotion versus prevention goal priming: fMRI evidence for distinct cognitive-motivational systems. Personal Neurosci. 2020. February 3;3:e1. doi: 10.1017/pen.2019.13. PMID: 32435748; PMCID: PMC7219697 *This article presents a conceptual model (and accompanying fMRI data) for the hypothesized promotion and prevention systems in healthy adults, which provides a basis for the self-regulation model of depression onset in the current article.

- 33.Strauman TJ and Wilson WA (2010). Individual Differences in Approach and Avoidance. In Handbook of Personality and Self-Regulation, Hoyle RH (Ed.). doi: 10.1002/9781444318111.ch20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo Gerfo E, Pisoni A, Ottone S, Ponzano F, Zarri L, Vergallito A, Varoli E, Fedeli D, Romero Lauro LJ. Goal Achievement Failure Drives Corticospinal Modulation in Promotion and Prevention Contexts. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018. April 24;12:71. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00071. PMID: 29740290; PMCID: PMC5928196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klenk MM, Strauman TJ, Higgins ET. Regulatory Focus and Anxiety: A Self-Regulatory Model of GAD-Depression Comorbidity. Pers Individ Dif. 2011. May 1;50(7):935–943. PMID 21516196; PMCID: PMC3079259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karoly P. Psychopathology as dysfunctional self-regulation: When resilience resources are compromised. In: Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Hall JS, eds. Handbook of Adult Resilience. The Guilford Press; 2010:146–170. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mason TB, Smith KE, Engwall A, Lass A, Mead M, Sorby M, Bjorlie K, Strauman TJ, & Wonderlich S (2019). Self-discrepancy theory as a transdiagnostic framework: A meta-analysis of self-discrepancy and psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 145(4), 372–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kendler KS. 2005. “A gene for…”: The nature of gene action in psychiatric disorders. Amer. Jl Psychi 162:1243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strauman TJ, Eddington KM. Treatment of Depression From a Self-Regulation Perspective: Basic Concepts and Applied Strategies in Self-System Therapy. Cognit Ther Res. 2017. February;41(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10608-016-9801-1. Epub 2016 Aug 29. PMID: 28216800; PMCID: PMC5308600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brinkman K, Franzen J. 2015. Depression and self-regulation: A motivational analysis and insights from effort-related cardiovascular reactivity. In Handbook of biobehavioral approaches to self-regulation, ed. Gendolla GHD, 333–348. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dickson JM, Johnson S, Huntley CD, Peckham A, Taylor PJ. An integrative study of motivation and goal regulation processes in subclinical anxiety, depression and hypomania. Psychiatry Res. 2017. October;256:6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karoly P. How Pain Shapes Depression and Anxiety: A Hybrid Self-regulatory/Predictive Mind Perspective. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2020. January 2. doi: 10.1007/s10880-019-09693-5. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 31897919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Acuff SF, Soltis KE, Dennhardt AA, Borsari B, Martens MP, Witkiewitz K, Murphy JG. Temporal precedence of self-regulation over depression and alcohol problems: Support for a model of self-regulatory failure. Psychol Addict Behav. 2019. November;33(7):603–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strauman TJ. Self-guides, autobiographical memory, and anxiety and dysphoria: toward a cognitive model of vulnerability to emotional distress. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992. February;101(1):87–95. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.87. PMID: 1537978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson N, Bryan BC, Thrash TM. Self-discrepancy: Long-term test-retest reliability and test-criterion predictive validity. Psychol Assess. 2016. January;28(1):59–69. doi: 10.1037/pas0000162. Epub 2015 Jun 1. PMID: 26029943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller AK, Markman KD (2007). Depression, regulatory focus, and motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 427–436. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winch A, Moberly NJ, Dickson JM. Unique associations between anxiety, depression and motives for approach and avoidance goal pursuit. Cogn Emot. 2015;29(7):1295–305. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.976544. Epub 2014 Nov 7. PMID: 25379697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strauman TJ. Self-Regulation and Psychopathology: Toward an Integrative Translational Research Paradigm. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017. May 8;13:497–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045012. Epub 2017 Mar 24. PMID: 28375727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arias JA, Williams C, Raghvani R, et al. The neuroscience of sadness: A multidisciplinary synthesis and collaborative review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2020;111:199–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.01.006. *This review article provides essential background and updated findings regarding how sadness as well as dysphoric affect and symptomatology manifests in brain function.

- 50.Hayes SC, Hofmann SG, Stanton CE, et al. The role of the individual in the coming era of process-based therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2019;117:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Lange MA, van Knippenberg A. To err is human: How regulatory focus and action orientation predict performance following errors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(6): 1192–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parker SL, Laurie KR, Newton CJ, Jimmieson NL. Regulatory focus moderates the relationship between task control and physiological and psychological markers of stress: a work simulation study. Int J Psychophysiol. 2014. December;94(3):390–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.10.009. Epub 2014 Oct 23. PMID: 25455429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shu T-M, Lam S. Are success and failure experiences equally motivational? An investigation of regulatory focus and feedback. Learning and Individual Differences. 2011;21(6):724–727. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scult MA, Knodt AR, Hanson JL, Ryoo M, Adcock RA, Hariri AR, Strauman TJ. Individual differences in regulatory focus predict neural response to reward. Soc Neurosci. 2017. August;12(4):419–429. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2016.1178170. Epub 2016 Apr 30. PMID: 27074863; PMCID: PMC5662473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strauman TJ, Socolar Y, Kwapil L, Cornwell JF, Franks B, Sehnert S, Higgins ET. Microinterventions targeting regulatory focus and regulatory fit selectively reduce dysphoric and anxious mood. Behav Res Ther. 2015. September;72:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.003. Epub 2015 Jun 11. PMID: 26163353; PMCID: PMC4529777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neacsiu AD, Luber BM, Davis SW, Bernhardt E, Strauman TJ, Lisanby SH. On the Concurrent Use of Self-System Therapy and Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation as Treatment for Depression. J ECT. 2018. December;34(4):266–273. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000545. PMID: 30308570; PMCID: PMC6242750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eddington KM, Silvia PJ, Foxworth TE, Hoet A, Kwapil TR. Motivational deficits differentially predict improvement in a randomized trial of self-system therapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015. June;83(3):602–616. doi: 10.1037/a0039058. Epub 2015 Apr 13. PMID: 25867448; PMCID: PMC4446180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goetz EL, Hariri AR, Pizzagalli DA, Strauman TJ. Genetic moderation of the association between regulatory focus and reward responsiveness: a proof-of-concept study. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2013. February 1;3(1):3. doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-3-3. PMID: 23369671; PMCID: PMC3570330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pizzagalli DA, Iosifescu D, Hallett LA, Ratner KG, Fava M. Reduced hedonic capacity in major depressive disorder: evidence from a probabilistic reward task. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hayes AM, Andrews LA. A complex systems approach to the study of change in psychotherapy. BMC Med. 2020. July 14; 18(1):197. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01662-2. PMID: 32660557; PMCID: PMC7359463. **This article presents a thoughtful and compelling case for how systems models can revolutionize the study of change processes in psychotherapy as well as other forms of psychiatric intervention.

- 61.Blanken TF, Van Der Zweerde T, Van Straten A, Van Someren EJW, Borsboom D, Lancee J. Introducing Network Intervention Analysis to Investigate Sequential, Symptom-Specific Treatment Effects: A Demonstration in Co-Occurring Insomnia and Depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88(1):52–54. doi: 10.1159/000495045. Epub 2019 Jan 9. PMID: 30625483; PMCID: PMC6469840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strauman TJ. Self-regulation and depression. Self and Identity 2000; 1:151–157. [Google Scholar]