Abstract

Background

Preterm infants often start milk feeds by gavage tube. As they mature, sucking feeds are gradually introduced. Women with preterm infants may not always be in hospital to breastfeed their baby and need an alternative approach to feeding. Most commonly, milk (expressed breast milk or formula) is given by bottle. Whether using bottles during establishment of breastfeeds is detrimental to breastfeeding success is a topic of ongoing debate.

Objectives

To identify the effects of avoidance of bottle feeds during establishment of breastfeeding on the likelihood of successful breastfeeding, and to assess the safety of alternatives to bottle feeds.

Search methods

A new search strategy was developed for this update. Searches were conducted without date or language limits in September 2021 in: MEDLINE, CENTRAL, and CINAHL. We also searched the ISRCTN trial registry and the reference lists of retrieved articles for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs and quasi‐RCTs comparing avoidance of bottles with use of bottles for preterm infants where their mothers planned to breastfeed.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. When appropriate, we contacted study authors for additional information. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence. Outcomes included full breastfeeding and any breastfeeding on discharge home and at three and six months after discharge, as well as length of hospital stay and episodes of infant infection. We synthesised data using risk ratios (RR), risk differences (RD) and mean differences (MD), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence.

Main results

We included seven trials with 1152 preterm infants in this updated review. There are three studies awaiting classification. Five included studies used a cup feeding strategy, one used a tube feeding strategy and one used a novel teat when supplements to breastfeeds were needed. We included the novel teat study in this review as the teat was designed to closely mimic the sucking action of breastfeeding. The trials were of small to moderate size, and two had high risk of attrition bias. Adherence with cup feeding was poor in one of the studies, indicating dissatisfaction with this method by staff or parents (or both); the remaining four cup feeding studies provided no such reports of dissatisfaction or low adherence.

Avoiding bottles may increase the extent of full breastfeeding on discharge home (RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.80; 6 studies, 1074 infants; low‐certainty evidence), and probably increases any breastfeeding (full and partial combined) on discharge (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.16; studies, 1138 infants; moderate‐certainty evidence). Avoiding bottles probably increases the occurrence of full breastfeeding three months after discharge (RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.37 to 1.78; 4 studies, 986 infants; moderate‐certainty evidence), and may also increase full breastfeeding six months after discharge (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.36; 3 studies, 887 infants; low‐certainty evidence).

Avoiding bottles may increase the occurrence of any breastfeeding (full and partial combined) three months after discharge (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.71; 5 studies, 1063 infants; low‐certainty evidence), and six months after discharge (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.41; 3 studies, 886 infants; low‐certainty evidence). The effects on breastfeeding outcomes were evident at all time points for the tube alone strategy and for all except any breastfeeding three months after discharge for cup feeding, but were not present for the novel teat. There were no other benefits or harms including for length of hospital stay (MD 2.25 days, 95% CI −3.36 to 7.86; 4 studies, 1004 infants; low‐certainty evidence) or episodes of infection per infant (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.42; 3 studies, 500 infants; low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Avoiding the use of bottles when preterm infants need supplementary feeds probably increases the extent of any breastfeeding at discharge, and may improve any and full breastfeeding (exclusive) up to six months postdischarge. Most of the evidence demonstrating benefit was for cup feeding. Only one study used a tube feeding strategy. We are uncertain whether a tube alone approach to supplementing breastfeeds improves breastfeeding outcomes; further studies of high certainty are needed to determine this.

Plain language summary

Avoidance of bottles during the establishment of breastfeeds in preterm infants

Review question: in preterm infants whose mothers want to breastfeed, does using bottles interfere with breastfeeding success?

Background: preterm infants start milk feeds by tube, and as they mature they are able to manage sucking feeds. The number of sucking feeds each day is gradually increased as the baby matures. Women with preterm infants may not always be in hospital every time the baby needs a sucking feed. Conventionally, bottles with mother's milk or formula have been used. It has been suggested that using bottles may interfere with breastfeeding success.

Study characteristics: we found seven eligible studies (involving 1152 preterm babies). These studies were of small to moderate size, and most had some problems with study design or conduct. The search is up to date as of 18 June 2020.

Key results: five studies (which included two of the largest studies) used cup feeds, and one used tube feeds. One study used a specially designed teat with feeding action suggested to be more like breastfeeding than conventional bottle feeding. Most studies were conducted in high‐income countries, only two in middle‐income countries and none in low‐income countries. Overall if bottle feeds (with a conventional teat) were not given, babies were more likely to be fully breastfed or to have at least some breastfeeds on discharge home and at three and six months postdischarge home. The study with the specially designed teat showed no difference in breastfeeding outcomes, so it was the cup alone or the tube alone that improved breastfeeding rates. However, because of the poor quality of the tube alone study, we are uncertain whether a tube alone approach to supplementing breastfeeds improves breastfeeding outcomes. We found no evidence of benefit or harm for any of the reported outcomes, including length of hospital stay or weight gain.

Conclusions: using a cup instead of a bottle increases the extent and duration of full and any breastfeeding in preterm infants up to six months postdischarge. Further high‐quality studies of the tube alone approach should be undertaken.

Certainty of evidence: we have low to moderate confidence in these results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle compared with breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials) in preterm infants.

| Breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle compared with breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials) in preterm infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: preterm infants Setting: neonatal units in Australia, Brazil, Turkey, the UK and the USA Intervention: breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle Comparison: breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials) | Risk with breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle | |||||

| Full breastfeeding compared with not breastfeeding or partial breastfeeding | Study population (on discharge) | RR 1.47 (1.19 to 1.80) | 1074 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | |

| 44 per 100 | 64 per 100 (52 to 79) | |||||

| Study population (3 months postdischarge) | RR 1.56 (1.37 to 1.78) | 986 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | ||

| 36 per 100 | 57 per 100 (50 to 65) | |||||

| Study population (6 months postdischarge) | RR 1.64 (1.14 to 2.36) | 887 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | ||

| 31 per 100 | 51 per 100 (35 to 73) | |||||

| Any breastfeeding (full and partial combined) compared with not breastfeeding | Study population (on discharge) | RR 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16) | 1138 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 79 per 100 | 88 per 100 (84 to 92) | |||||

| Study population (at 3 months postdischarge) | RR 1.31 (1.01 to 1.71) | 1063 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | — | ||

| 60 per 100 | 78 per 100 (60 to 100) | |||||

| Study population (6 months postdischarge) | RR 1.25 (1.10 to 1.41) | 886 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,d | — | ||

| 45 per 100 | 56 per 100 (49 to 63) | |||||

| Length of hospital stay (days) | — | MD 2.25 higher (3.36 lower to 7.86 higher) | — | 1004 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | — |

| Episodes of infection per infant | Study population | RR 0.70 (0.35 to 1.42) | 500 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,e | — | |

| 7 per 100 | 5 per 100 (2 to 10) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect but may be substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for attrition bias (14% and 15% attrition in two included studies). bDowngraded one level due to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 52%). cDowngraded one level due to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 73%). dDowngraded one level due to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 50%). eDowngraded one level due to imprecision.

Background

Description of the condition

Preterm infants begin sucking feeds when they are mature enough to co‐ordinate sucking and swallowing; this occurs at around 32 to 34 weeks' gestation (Lemons 1996). Milk feeds are usually given through a gavage tube until infants are able to receive all their intake by sucking feeds. Once sucking feeds begin, they are increased gradually, usually beginning with once a day and increasing as the infant demands or is assessed as ready to progress. As the number of sucking feeds increases, the number of tube feeds decreases until sucking feeds alone provide sufficient intake for growth and development. It is not always possible for a mother to be available to breastfeed during this transition time. Supplementary feeds may also be given in some circumstances. When a mother cannot be physically present to breastfeed her infant, or when supplementary milk is given, then expressed breast milk, donor breast milk or formula may be administered by bottle. However, there is concern that the use of bottles may negatively impact on breastfeeding outcomes.

Description of the intervention

Alternatives to bottles during this transition time have been reported and include feeding the infant by cup (Lang 1994a), gavage tube (Stine 1990), finger feeding (Healow 1995; Kurokawa 1994), spoon (Aytekin 2014), and paladai – a traditional feeding device used in India (Malhotra 1999). Increased breastfeeding prevalence has been reported when bottle feeds were replaced by cup feeds (Abouelfettoh 2008; Gupta 1999; Lang 1994a) or tube feeds (Stine 1990), and infants have been reported to achieve all breastfeeds sooner with spoon feeding (Aytekin 2014). However, these studies were small and did not include a control group.

How the intervention might work

It has been suggested that using bottles may interfere with establishing successful breastfeeding, possibly because of a difference in the sucking action required for the breast versus an artificial nipple (Bu'Lock 1990; Neifert 1995).

Why it is important to do this review

Alternatives to breastfeeds are not necessarily benign. With both bottle feeds (Bier 1993; Blaymore Bier 1997; Chen 2000; Young 1995) and cup feeds (Dowling 2002; Freer 1999), studies have reported mean oxygen saturation is lower and the frequency of oxygen desaturation is greater than with breastfeeding, highlighting the importance of considering safety aspects of any alternatives to bottle feeds. Use of both cup and paladai has been associated with a tendency for infants to 'spill' a large proportion of the feed (Aloysius 2007; Dowling 2002). However, other studies have not reported problems associated with cup feeding (Gupta 1999; Lang 1994a).

Cups and similar feeding vessels are easier to clean than bottles and artificial teats; this fact may be of particular relevance for infection control in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

For women who plan to breastfeed their preterm infant, it is important to establish the most efficacious and least harmful method of supplementing breastfeeds.

Objectives

To identify the effects of avoidance of bottle feeds during establishment of breastfeeding on the likelihood of successful breastfeeding, and to assess the safety of alternatives to bottle feeds.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All trials using random or quasi‐random participant allocation.

Types of participants

Infants born at less than 37 weeks' gestation whose mothers had planned to breastfeed, and who had not received 'sucking' feeds by bottle or any alternative feeding device at study entry. At enrolment, infants may have been receiving enteral feeds only, parenteral feeds only or a combination of parenteral and enteral feeds. Their enteral milk intake may have been provided via tube (using expressed breast milk or formula, or both) or breastfeeds. Tube feeds could be continuous or intermittent, and tube placement could be gastric or duodenal.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention: complete avoidance of bottles during the transition to breastfeeds. Instead of bottles, alternative feeding devices were used for complementing or supplementing breastfeeds, including gavage tube, cup, spoon, dropper, finger feeding, paladai and other.

Control intervention: breastfeeds complemented or supplemented with bottles during the transition to breastfeeds.

Types of outcome measures

Primary and secondary outcome measures are described below.

Primary outcomes

Full breastfeeding compared with not breastfeeding or partial breastfeeding on discharge home and at three months and six months postdischarge

Any breastfeeding (full and partial combined) compared with not breastfeeding on discharge home and at three months and six months postdischarge

Secondary outcomes

Time (days) to reach full sucking feeds

Mean rate of weight gain (grams/day or grams/kilogram/day) to discharge home

Length of hospital stay (days)

Duration (minutes) of supplementary or complementary feed

Volume of supplementary feed taken compared with volume prescribed (millilitres)

Cardiorespiratory stability during and after intervention (mean heart and respiratory rates; proportions of bradycardic and apnoeic events during feed; mean oxygenation measured by oximetry or transcutaneous monitor; proportion of hypoxic events during feed)

Episodes of choking/gagging per feed

Milk aspiration on radiological assessment

Parent/health professional satisfaction with feeding method as measured by self‐report

Episodes of infection per infant

Search methods for identification of studies

In consultation with the authors, the Neonatal Group Information Specialist developed new search strategies for this update. Controlled vocabulary and keywords were used and combined with methodological filters to restrict retrieval to RCTs. Searches were conducted without language, publication year, or publication status restrictions.

Electronic searches

The following databases were searched September 24, 2021:

Cochrane Central Database via CRS (Cochrane Register of Studies)

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process, In‐Data‐Review & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Daily <1946 to May 28, 2021>

CINAHL Ebsco (1982‐)

2021 search strategies in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3. Previous search strategies in Appendix 4; Appendix 5

Searching other resources

Trial registration records were identified using CENTRAL and an independent search of the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/) was conducted in June 2020 for trials not found through the Cochrane CENTRAL. We checked the bibliographies of published trials to identify additional relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal.

Selection of studies

We merged search results from different databases, using reference management software, and removed duplicates. For the 2016 review update (Collins 2016b), one review author (CC) screened titles and abstracts and removed obviously irrelevant reports. Three review authors (CC, HS, JG) independently reviewed the abstracts of potentially relevant reports. When uncertainty about inclusion of the study arose, we retrieved the full text. We (CC, HS, JG) resolved disagreements on inclusion of studies.

For the review updated in 2020, two review authors (EA, AR) independently reviewed all abstracts that had been identified in a search of different databases. When uncertainty about inclusion of the study arose, we retrieved the full text and discussed with a third review author (CC). We used Cochrane's Screen4Me workflow to help assess the search results. Screen4Me comprises three components: known assessments – a service that matches records in the search results to records that have already been screened in Cochrane Crowd and been labelled as an RCT or as Not an RCT; the RCT classifier – a machine learning model that distinguishes RCTs from non‐RCTs, and if appropriate, Cochrane Crowd – Cochrane's citizen science platform where the Crowd help to identify and describe health evidence. For more information about Screen4Me, see community.cochrane.org/organizational-info/resources/resources-groups/information-specialists-portal/crs-videos-and-quick-reference-guides#Screen4Me. Detailed information regarding evaluations of the Screen4Me components can be found in Marshall 2018; Noel‐Storr 2020; Noel‐Storr 2021; Thomas 2020.

Data extraction and management

Once inclusion of trials was established, two review authors (CC, HS) independently assessed trial methods, extracted data onto paper forms, assessed risk of bias, and discussed and resolved disagreements. One review author (CC) was an investigator for one study (Collins 2004). Another review author (JG) performed data extraction for this study.

For the review update in 2016 (Collins 2016b), we requested additional information from Garpiel 2012 (only abstract available) and from Yilmaz 2014 (gestational age category used in stratification) but received no response. For the 2008 version of this review (Collins 2008), we requested additional information from three studies (Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Rocha 2002). We received additional information from Kliethermes 1999 (on breastfeeding prevalence, apnoeic/bradycardic episodes and blinding of assessment outcome), and from Gilks 2004 (on exclusions post‐randomisation, years study was conducted, type of cup used, days to reach full sucking feeds and milk aspiration).

For the review update in 2020, we requested additional information from Garpiel 2012 (only abstract available) but received no response. We also requested additional information from Capdevila 2016 (only abstract available). The response we received from Capdevila 2016 allowed us to exclude the study, as data were not reported separately by group allocation and raw data could not be provided by the study authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CC, HS) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for the following domains (Higgins 2011).

Sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Any other bias.

We resolved disagreements by consensus and, if necessary, by adjudication with a third review author. See Appendix 6 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed treatment effects in individual trials using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020). We analysed dichotomous data using risk ratios (RRs), risk difference (RDs) and numbers needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTBs), or numbers needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTHs). We reported 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all estimates and used mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs for outcomes measured on a continuous scale. We analysed differences in the number of events for outcomes measured as count data (e.g. episodes of choking/gagging) by comparing rates of events in the two groups.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participating infant in individually randomised trials. We excluded cross‐over studies and cluster randomised trials.

Dealing with missing data

We requested additional data from trial investigators when data on important outcomes were missing or were reported unclearly. For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. If we had concerns regarding the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect, we explored this through sensitivity analysis.

We analysed all outcomes on an intention‐to‐treat basis (i.e. we included in the analyses all participants randomly assigned to each group). The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomly assigned minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We estimated the treatment effects of individual trials and examined heterogeneity among trials by inspecting the forest plots and quantifying the impact of heterogeneity using the I² statistic. We graded the degree of heterogeneity as: less than 25% no heterogeneity; 25% to 49% low heterogeneity; 50% to 75% moderate heterogeneity; more than 75% substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

For included trials that were recently performed (and therefore prospectively registered), we explored possible selective reporting of study outcomes by comparing primary and secondary outcomes in the reports versus primary and secondary outcomes proposed at trial registration, using the websites www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.isrctn.com/. Funnels plots were planned to be generated for comparisons where there is data from 10 or more studies.

Data synthesis

We conducted meta‐analyses using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020), as supplied by Cochrane. We used the Mantel‐Haenszel method to obtain estimates of typical RR and RD. For analysis of continuous measures, we used the inverse variance method. For all meta‐analyses, we used a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analyses to determine whether safety and efficacy outcomes were altered by the type of intervention used (cup, tube alone or novel teat) and the country in which the study was set (low‐ and middle‐income countries versus high‐income countries; classified according to World Bank classifications: datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519). When we found moderate to high heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we used a random‐effects model and investigated potential sources of the heterogeneity (differences in study quality, participants or treatment regimens). When heterogeneity was explained by subgroup analysis, we presented results in this way.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analysis to determine if the findings were affected by inclusion of only those trials considered to have used adequate methodology with a low risk of bias (selection and performance bias). We reported results of sensitivity analyses for primary outcomes only.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the certainty of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes: full breastfeeding (at discharge, three months and six months postdischarge), any breastfeeding (at discharge, three months and six months postdischarge), length of hospital stay and episodes of infection.

Two review authors (CC, HS) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from RCTs as high certainty and downgraded the evidence one level for serious (and two levels for very serious) limitations on the basis of the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of the evidence, precision of estimates and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create a summary of findings table to report the certainty of the evidence.

The GRADE approach provides an assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence based on four grades.

High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables.

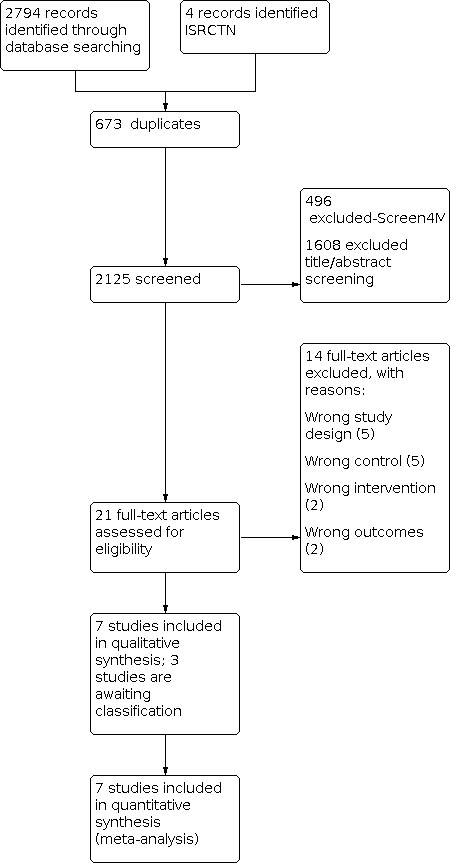

Results of the search

Database searches in 2021 identified 2794 references; a search of ISRCTN in June 2020 identified 4 records (total = 2798); 673 duplicates were identified; and 2125 records were available for screening.

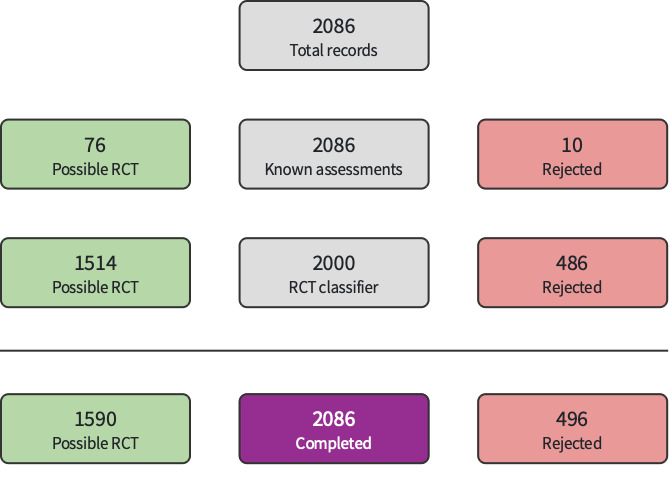

Two components of Cochrane's Screen4Me (Noel‐Storr 2020; Noel‐Storr 2021; Noel‐Storr 2021a; Noel‐Storr 2021b; Screen4Me), known assessments and RCT classifier, were used to assess a portion of results from database searches (e.g. those records without the words systematic review or meta‐analysis in the title), N= 2086. Of these, 496 were classified as non‐RCTs and were excluded (Figure 1).

1.

Screen4Me: September 2021

In summary: of 2125 records, 496 were eliminated by Screen4Me; 1608 were excluded during title abstract screening; 14 were excluded, with reasons, after full‐text review. This update search identified no new trials for inclusion; seven trials are included in this review. Three studies are awaiting classification. For details see the study flow diagram (Figure 2).

2.

2021 Flow Diagram

Included studies

We included seven studies (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014). Three studies are awaiting classification; see the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for details.

Collins 2004 is a primary study report; a PhD thesis presents additional data related to this study (i.e. extent of breastfeeding, any and full, at three months and six months postdischarge, time to full sucking feeds, weight gain, milk aspiration and reasons for non‐compliance). Simmer 2016 is a primary study report that was first published in abstract form. Studies were undertaken in neonatal units in Australia (Collins 2004; Simmer 2016), Brazil (Rocha 2002), England (Gilks 2004; Mosley 2001), Turkey (Yilmaz 2014), and the USA (Kliethermes 1999). Five trials were single‐centre studies (Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016), and two were multicentre studies (Collins 2004 – two centres; Yilmaz 2014 – three centres).

Participants

This review included 1152 infants; sample sizes ranged from 14 to 522 participants. All studies included preterm infants, although limits for gestational age and birth weight differed. Four studies included extremely preterm and very preterm infants (Collins 2004: less than 34 weeks; Rocha 2002: 32 weeks to 34 weeks; Gilks 2004 and Simmer 2016: less than 35 weeks), and two included moderate‐to‐late preterm infants (Mosley 2001: 32 weeks to 37 weeks; Yilmaz 2014: 32 weeks to 35 weeks); Kliethermes 1999 used a birth weight criterion of 1000 g to 2500 g.

Five studies stratified infants at randomisation – one by birth weight (Rocha 2002), and four by gestational age (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014).

The mean gestational age of included infants across all seven trials was 32 weeks.

Interventions

Infants receiving alternative feeding devices (cup, gavage tube, paladai, finger feeding, dropper, spoon or other) were classified as the experimental group, and infants who received bottle feeding were classified as the control group.

Five studies compared breastfeeding with supplementary feeds given by cup versus breastfeeding with supplementary feeds given by bottle (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014). One trial compared breastfeeding with supplementary feeds by bottle versus breastfeeding with supplementary feeds by gavage tube alone (Kliethermes 1999). The Simmer 2016 trial used a specially developed feeding system that incorporated a shut‐off valve in the teat, so that milk flowed only when the infant created a vacuum; collapse of the teat was prevented by a venting system. Infants controlled the flow of milk by raising the tongue when sucking stopped; study authors (Simmer 2016) showed that this action was similar in breastfed term infants (Geddes 2012). Although this intervention used a bottle and a teat, the review authors agreed to include this study in the review, given that the 'novel teat' causes action that is purportedly similar to the breastfeeding action compared with conventional teats used in all other studies.

In all studies, neither bottle feeds nor alternative feeding devices (cup/tube alone/novel teat) were used to replace a breastfeed and were given only when the mother was not available to breastfeed, or if extra milk was thought necessary after a breastfeed and investigators determined that the infant was able to take this orally.

Among the cup feeding studies, four (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014) followed the cup feeding recommendations of Lang (Lang 1994a; Lang 1994b). Rocha 2002 used the protective cap from a bottle, Collins 2004 and Yilmaz 2014 used a 60 mL medicine cup and Gilks 2004 used an Ameda baby cup. Mosley 2001 did not state the type of cup used and did not describe the cup feeding procedure. An indwelling nasogastric tube remained in situ for both experimental and control groups in two studies in which feeds were given by tube if insufficient milk was taken during cup or breastfeeding, or if the infant was not scheduled for a sucking feed (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004). It is not stated whether this occurred for cup feeds in the other studies (Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014).

For breastfeeding with supplementary feeds by bottle compared with breastfeeding with supplementary feeds by gavage tube (Kliethermes 1999), all infants received standard care (including non‐nutritive breastfeeding) until written orders for oral feedings were given. For the control group, all supplementary feeds were given by bottle, and the indwelling nasogastric tube was removed as directed by the clinical care team. For the experimental group (gavage tube), feeds were given by an indwelling 3.5 gauge French nasogastric tube. The tube was removed during the last 24 hours to 48 hours of parent 'rooming‐in', at which time a cup or syringe was used if needed.

Three studies encouraged skin‐to‐skin contact and non‐nutritive sucking at the breast for all infants (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Simmer 2016). The remaining studies did not report this (Gilks 2004; Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014).

Sucking feeds for experimental and control groups were commenced and advanced according to individual hospital policy. One trial based this decision on weight (1600 g) (Rocha 2002). In Collins 2004, sucking feeds began when infants were assessed as mature enough to co‐ordinate a suck‐swallow‐breathe reflex. In some studies, sucking feeds occurred at the discretion of the nurse or midwife (Collins 2004), the neonatologist (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Yilmaz 2014), or the neonatal nurse practitioner (Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001). Two studies did not report this information (Gilks 2004; Simmer 2016).

Non‐nutritive sucking with use of a dummy (also known as a pacifier) varied among the included studies. Collins 2004 randomised infants to cup/no dummy, cup/dummy, bottle/no dummy and bottle/dummy and reported no statistically significant interaction between infants randomised to no dummy or cup; therefore, results from marginal groups (cup versus bottle and dummy versus no dummy) could be analysed independently. In Kliethermes 1999, a dummy was available during tube feedings for the experimental group, and study authors did not report whether a dummy was available outside feeding times in either group. In Rocha 2002, a dummy was not used for the experimental (cup) group, and Mosley 2001 reported that six infants were given a dummy. Simmer 2016 encouraged non‐nutritive sucking in both groups, and Gilks 2004 and Yilmaz 2014 did not report dummy use.

Outcomes

No study reported all outcomes.

All seven studies measured breastfeeding outcomes. Six studies measured full breastfeeding at discharge home from hospital (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014); four studies at three months postdischarge (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014); and three studies at six months postdischarge (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014).

Six studies measured any breastfeeding at discharge home from hospital (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014); five studies at three months postdischarge (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014); and three studies at six months postdischarge (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014).

Three studies used the following definition of full breastfeeding: no other solids or liquids were given apart from vitamins, minerals, juice or ritualistic feedings, given infrequently (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014). Mosley 2001 used the term 'exclusive' and Simmer 2016 'fully' breastfeeding but did not define the terms; however, these investigators reported both breastfeeding and breast milk feeds. Rocha 2002 defined breastfeeding as feeding exclusively or partially directly at the breast. Kliethermes 1999 and Gilks 2004 considered infants who were receiving supplementary feeds of expressed breast milk on discharge as partially breastfed, and Collins 2004 considered them fully breastfed. Six women (2%)with seven (2%) of infants in Collins 2004 had chosen to feed their infants expressed breast milk by bottle; researchers randomised three to cup feeds and four to bottle feeds.

At three months and six months postdischarge, Collins 2004 used the term 'all breastfeeds' to indicate that an infant's milk feeds were breastfeeds only when no other types of milk were given, and 'partial breastfeeds' to mean that an infant's milk feeds were a combination of breastfeeds and other types of milk. The intent was to determine the types of milk feeds infants were receiving (breast or formula), irrespective of whether they were receiving solids. This does not fit with the conventional definition of full breastfeeding (Labbok 1990), that is, if an infant is on solids and all milk feeds are breastfeeds, the infant is usually classified as 'partially' breastfeeding. The 2008 version of this review did not include data for 'all breastfeeds' in the meta‐analyses (Collins 2008). Given the small number of studies reporting this outcome, review authors reconsidered and included the data for 'all breastfeeds' in the meta‐analysis in the 2016 update (Collins 2016b).

Three studies measured the time taken to reach full sucking feeds (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Simmer 2016). Three studies reported rate of weight gain (Collins 2004; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014); four length of hospitalisation (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014); and two supplementary feeding time (Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014). No studies reported the volume of supplementary feed taken compared with the volume prescribed.

Two studies reported cardiorespiratory stability. Kliethermes 1999 reported apnoeic or bradycardic episodes, and Rocha 2002 reported oxygen saturation associated with mode of feeding. No studies reported episodes of choking/gagging, and two trials reported milk aspiration (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004). Collins 2004 reported parental satisfaction, and three studies reported episodes of infection (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Simmer 2016).

Excluded studies

We excluded 14 studies in total.

Six studies were not RCTs (Abouelfettoh 2008; Aytekin 2014; De Aquino 2009; Harding 2014; Lau 2012; Ronan 2013).

Two studies were randomised cross‐over trials (Aloysius 2007; López 2014).

Two studies did not include a bottle control group (Kumar 2010; Marofi 2016).

Three studies because the studies did not include a bottle control group (De Alencar Nunes 2019; IRCT2015090518561N4; Rahmani 2018);

One study because it did not report outcomes by group allocation (Capdevila 2016).

See Characteristics of excluded studies table for details.

Studies awaiting classification

Three studies is awaiting classification (Calikusu Incekar 2021; Cresi 2020; Garpiel 2012). See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for details.

Risk of bias in included studies

We provided details of the methodological quality of each study in the Characteristics of included studies table (Figure 3; Figure 4).

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Risk of selection bias was low with adequate methods of random sequence generation described in six studies (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014), and not described in Gilks 2004. Allocation concealment was adequate in six studies (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014), and was unclear in Rocha 2002.

Blinding

Risk of performance and detection bias was high, as blinding of treatment was not possible in any study. Five studies did not clearly state whether outcome assessment was blinded (Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014). Two studies stated that data for outcomes were collected unblinded (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004). Simmer 2016 was the only study that described blinding of analyses.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data as low in six studies (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014), and high in Kliethermes 1999. Studies handled protocol violations differently; five studies excluded the infants from analyses (Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014). Proportions of incomplete outcome data for the primary outcome were as follows: Collins 2004 5%, Gilks 2004 0%, Kliethermes 1999 15%, Mosley 2001 13%, Rocha 2002 6%, Simmer 2016 3% and Yilmaz 2014 14%.

Collins 2004 reported a high proportion of non‐compliance. In the experimental (cup) group, 85/151 (56%) infants had a bottle introduced, and in the control group, 1/152 (0.7%) infants had a cup introduced. Infants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised.

Selective reporting

The risk of reporting bias was rated as low in five studies (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Simmer 2016) and unclear in two studies (Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014).

Other potential sources of bias

We found no evidence of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1.

Breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by bottle

This review included seven studies with 1152 infants.

We conducted subgroup analyses to determine whether outcomes were altered by type of intervention. We incorporated the subgroups into the main structure of each figure.

Full breastfeeding (Outcomes 1.1 to 1.3)

At discharge home

Six studies reported full breastfeeding in 1074 infants at discharge home (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Mosley 2001; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014). Three trials (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014), as well as the meta‐analysis of data from all trials, showed a statistically significantly higher rate of full breastfeeding in the experimental (avoid bottle) group, with moderate heterogeneity (typical RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.80; RD 0.21, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.32; NNTB 5, 95% CI 3 to 11; I2 = 52%; Analysis 1.1; low‐certainty evidence).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 1: Full breastfeeding (BF) at discharge

Subgroup analyses by intervention type: full breastfeeding at discharge home (Outcomes 1.1.1 to 1.1.3)

The subgroup interaction test was not statistically different, although the P = 0.08 indicates that the effect on breastfeeding of a tube alone approach may have a more significant impact on breastfeeding success than a cup feeding approach. However, only one small study with high risk of bias used a tube alone feeding approach (Kliethermes 1999).

Four studies with 893 infants compared cup feeds with bottle feeds (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Mosley 2001; Yilmaz 2014). The statistically significant increase in full breastfeeding remained, with low heterogeneity (typical RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.75; RD 0.20, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.308; NNTB 5, 95% CI 3 to 10; I2 = 45%). Kliethermes 1999 reported a significant increase in full breastfeeding (tube alone versus bottle), and Simmer 2016 when comparing different teats found no difference in full breastfeeding.

Three months postdischarge

Four studies with 986 infants reported full breastfeeding three months postdischarge (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014). Two studies (Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014), and the meta‐analysis showed a statistically significantly higher rate of full breastfeeding in the experimental (avoid bottle) group, with low heterogeneity (typical RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.37 to 1.78; RD 0.20, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.26; NNTB 5, 95% CI 4 to 7; I2 = 37%; Analysis 1.2; moderate‐certainty evidence).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 2: Fully breastfeeding 3 months postdischarge

Subgroup analyses by intervention type: full breastfeeding at three months postdischarge (Outcomes 1.2.1 to 1.2.3)

The subgroup interaction test was not statistically significantly different (P = 0.31). Cup feeding compared with bottle feeding showed a significant increase in full breastfeeding, with moderate heterogeneity (typical RR 1.54, 95% CI 1.34 to 1.77; RD 0.21, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.27; NNTB 5, 95% CI 4 to 7; I2 = 61%; Collins 2004; Yilmaz 2014). Setting, participants and risk of bias differed in the two cup feeding studies. Collins 2004 was conducted in a high‐income country, included more immature infants (mean gestational age 30 weeks) and reported low adherence with the intervention and overall low risk of bias, whereas Yilmaz 2014 included more mature infants (mean gestational age 33 weeks) and high adherence with the intervention, was conducted in a high‐ to middle‐income country and had high risk of attrition bias. Kliethermes 1999 reported that tube alone versus bottle showed increased full breastfeeding, and Simmer 2016 described no differences when different teats were compared.

Six months postdischarge

Three studies reported full breastfeeding six months postdischarge (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014). Full breastfeeding was significantly increased in the experimental (avoid bottle) group in individual trials and the meta‐analysis, with moderate heterogeneity (typical RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.36; RD 0.15, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.24; NNTB 7, 95% CI 4 to 14; 3 studies, 887 infants; I2 = 52%; Analysis 1.3; low‐certainty evidence).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 3: Fully breastfeeding 6 months postdischarge

Subgroup analyses by intervention type: full breastfeeding at six months postdischarge (Outcomes 1.3.1 to 1.3.3)

Tube alone versus bottle statistically significantly increased full breastfeeding (Kliethermes 1999). The subgroup interaction test (P = 0.06) indicated that the effect on breastfeeding of the tube alone approach may have a more significant impact on breastfeeding success than the cup feeding approach, as described above (Kliethermes 1999). The two cup feeding trials noted an increase in full breastfeeding in the cup group, with no heterogeneity (typical RR 1.54, 95% CI 1.34 to 1.77; RD 0.13, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.19, NNTB 8, 95% CI 5 to 14; I2 = 0%; Collins 2004; Yilmaz 2014).

Any breastfeeding

At discharge home

Six studies (including 1138 infants) reported any breastfeeding at discharge home (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014). Two studies (Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014), as well as the meta‐analysis showed a statistically significantly higher rate of any breastfeeding on discharge home in the experimental (avoid bottle) group, with no heterogeneity (typical RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.16; RD 0.09, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.13; NNTB 11, 95% CI 8 to 20; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.4; moderate‐certainty evidence).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 4: Any breastfeeding at discharge

Subgroup analyses by intervention type: any breastfeeding at discharge home (Outcomes 1.4.1 to 1.4.3)

The subgroup interaction test was not statistically significantly different (P = 0.17). One of the cup feeding studies (Yilmaz 2014), and the meta‐analysis revealed a significant increase in breastfeeding (typical RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.15; RD 0.07, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.11; NNTB 14, 95% CI 9 to 33; 4 studies, 957 infants; I2 = 0%; Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014), as did the tube alone trial (Kliethermes 1999), but Simmer 2016 noted no such increase upon comparing two different types of teats.

Three months postdischarge

Five studies with 1063 infants reported any breastfeeding three months postdischarge (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Rocha 2002; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014). Two studies (Kliethermes 1999; Rocha 2002), and a meta‐analysis of data showed a statistically significant increase in the rate of any breastfeeding in the experimental (avoid bottle) group, with moderate heterogeneity (typical RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.71; RD 0.14, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.24; NNTB 7, 95% CI 4 to 25; I2 = 73%; Analysis 1.5; low‐certainty evidence).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 5: Any breastfeeding 3 months postdischarge

Subgroup analyses by intervention type: any breastfeeding at three months postdischarge (Outcomes 1.5.1 to 1.5.3)

The subgroup interaction test was not statistically significantly different (P = 0.34). There was no clear benefit of cup feeding for any breastfeeding at three months postdischarge (3 studies, 883 infants; Collins 2004; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014). Tube alone showed a statistically significant increase in any breastfeeding (Kliethermes 1999), but there were no statistically significant differences between novel and conventional teats (Simmer 2016).

Six months postdischarge

Three studies with 886 infants provided data on any breastfeeding six months postdischarge (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014). Two studies (Kliethermes 1999; Yilmaz 2014), and a meta‐analysis showed a statistically significant increase in experimental (avoid bottle) groups, with moderate heterogeneity (typical RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.41; RD 0.11, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.17; NNTB 9, 95% CI 6 to 20; I2 = 50%; Analysis 1.6; low‐certainty evidence).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 6: Any breastfeeding 6 months postdischarge

Subgroup analyses by intervention type: any breastfeeding at three months postdischarge (Outcomes 1.6.1 and 1.6.2)

Cup feeding in Collins 2004 and Yilmaz 2014 (803 infants) resulted in a statistically significant increase in any breastfeeding at six months postdischarge, with no heterogeneity (typical RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.36; RD 0.09, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.16; NNTB 11, 95% CI 6 to 22; I2 = 0%). Tube alone also showed a statistically significant increase in any breastfeeding (Kliethermes 1999). The subgroup interaction test P = 0.06 in Kliethermes 1999 indicated that the effect on breastfeeding of a tube alone approach may have a more significant impact on breastfeeding success than a cup feeding approach. However, only one small study with high risk of bias used a tube alone approach.

Time (days) to reach full sucking feeds

Four studies measured time to reach full sucking feeds in 513 infants (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Simmer 2016; Analysis 1.7). Two studies found a significant increase in days to reach full sucking feeds in the experimental (avoid bottle) group (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999). Kliethermes 1999 did not report standard deviations (SD), so their data could not be included in the meta‐analysis; however, the increase (7.5 days) was of the same magnitude as reported in Collins 2004 (10.5 days). Meta‐analysis revealed no clear effect on days to taken to reach full sucking feeds in the experimental (avoid bottle) group (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Simmer 2016).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 7: Time (days) to reach full sucking feeds

Subgroup analyses by intervention type: time (days) to reach full sucking feeds (Outcomes 1.7.1 and 1.7.2)

The subgroup interaction test was not statistically significantly different (P = 0.28). Neither the two cup feeding trials (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; 332 infants), nor the novel teat feeding trial (Simmer 2016), showed a clear increase or reduction in days to reach full sucking feeds. The tube alone study reported a significant increase in days to reach full sucking feeds (Kliethermes 1999).

Mean rate of weight gain (grams/kilogram/day or grams/day)

Three studies with 893 infants (all cup) reported no statistically significant differences in weight gain (grams/kilogram/day; Analysis 1.8), when measured from birth to discharge home (Collins 2004), or one week after oral feeds were commenced (Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014). A meta‐analysis was not possible because studies used different units of measurement. Simmer 2016 reported that infants in the experimental (novel teat) group were statistically significantly lighter on discharge home (MD −186 g, 95% CI −317 to −56).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 8: Mean rate of weight gain

Length of hospital stay (days)

Four studies with 1004 infants reported length of hospital stay (Collins 2004; Kliethermes 1999; Simmer 2016; Yilmaz 2014). Collins 2004 found a statistically significant increase in length of hospital stay of 10 days with the experimental (cup) group, but meta‐analysis revealed no statistically significant difference, with moderate heterogeneity (MD 2.25 days, 95% CI −3.36 to 7.86; I2 = 73%; Analysis 1.9; low‐certainty evidence).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 9: Length of hospital stay (days)

Subgroup analyses by intervention type: length of hospital stay (days) (Outcomes 1.9.1 to 1.9.3)

The subgroup interaction test was not statistically significantly different (P = 0.51). The two cup feeding trials with 823 infants showed no clear difference in length of hospital stay, with high heterogeneity (MD 4.45 days, 95% CI −5.57 to 14.48; I2 = 90%; Collins 2004; Yilmaz 2014). The overall length of stay differed between these studies owing to differences in the maturity of included infants. Collins 2004 suggested that increased length of stay may have been related to problems with staff and acceptance by parents of cup feeding, with some infants less satisfied and more difficult to feed by cup as they matured, resulting in feeding by tube and delayed onset of all sucking feeds, which is a requirement for discharge home. Kliethermes 1999 (tube alone) and Simmer 2016 (novel teat) also showed no statistically significant differences in length of hospital stay.

Duration (minutes) of supplementary feed

Two studies with 600 infants (both cup intervention) measured duration of supplementary feeds and showed no significant differences in time taken to cup feed versus time taken to bottle feed, with moderate heterogeneity (MD −0.42 minutes, 95% CI −1.96 to 1.12; I2 = 60%; Analysis 1.10; Rocha 2002; Yilmaz 2014). The heterogeneity was not explained by the maturity of included infants, as infants in both studies were at a mean of 33 weeks' gestation.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 10: Duration (minutes) of supplementary feed

Volume of supplementary feed taken compared with volume prescribed (millilitres)

No studies reported the volume of supplementary feed taken compared with the volume prescribed.

Cardiorespiratory stability during and after intervention

One trial reported the total number of episodes of apnoea and bradycardia per infant (Kliethermes 1999). Researchers described significantly fewer apnoeic and bradycardic incidents for the experimental (tube alone) group (mean 127, SD not reported) compared with the control (bottle) group (mean 136, SD not reported; P = 0.0006). However, the breastfeeding plus bottle group had significantly more episodes requiring stimulation (mean 32.7 episodes, SD not reported with breastfeeding plus bottle versus mean 23.3 episodes, SD not reported with bottle; P = 0.0001). Investigators measured apnoeic and bradycardic episodes over the entire hospital stay – not just episodes associated with feeding. Rocha 2002 reported mean oxygen saturation during feeds and found no statistically significant difference in the mean of the lowest oxygen saturation during feeds (mean 90.8, SD 4.8, range 75 to 99 with cup versus mean 87.7, SD 7.6, range 68 to 97 with bottle). Rocha 2002 also reported oxygen desaturation during feeds and found no difference in desaturation episodes of less than 90% with cup feeds (18/44, 40.9%) compared with the bottle group (19/34, 55.9%). Researchers reported a statistically significant difference in the proportion of desaturation episodes less than 85%, with fewer occurring in cup groups (6/44, 13.6%) than in bottle groups (12/34, 35.3%; P = 0.02).

Episodes of choking/gagging per feed

No studies reported episodes of choking or gagging.

Milk aspiration on radiological assessment

The three studies that reported this outcome described no episodes of milk aspiration (Collins 2004; Gilks 2004; Yilmaz 2014).

Parent/health professional satisfaction with feeding method

One study included views of parents on the method of feeding and noted a high rate of non‐compliance, with 85/151 (56%) infants in the intervention (breastfeeding with supplemental feeds by cup) group having a bottle introduced (Collins 2004). Compliance differed between recruiting hospitals; the hospital at which cup feeding was introduced specifically for this study had a higher rate of compliance than the other recruiting hospital, where cup feeding had been practised for three years before the study began. Researchers collected data on reasons for the introduction of a bottle from the medical records or after discussion with attending nurses or midwives. Reasons for introducing a bottle were available for 63/85 (74%) infants randomised to cup feeds who had a bottle introduced. In 41 (65%) infants, the reason given for using a bottle was that it was introduced at the request of the mother, and the staff initiated the bottle in 18 (29%) infants. In six (10%) infants, researchers introduced a bottle because the baby was not satisfied with cup feeds or would not settle down. One infant randomised to the bottle group had a cup introduced because of transfer to a peripheral hospital, where cup feeding was routinely used.

The three‐month postdischarge questionnaire included a question to the mother on reasons for introduction of a bottle. Reasons were available for 77/85 (91%) infants randomised to cup feeds who had a bottle introduced. Women could select from a list of options, and additional space was provided for any other comments. A total of 34 (44%) mothers indicated that the decision to introduce a bottle was theirs, and 25 (33%) mothers were advised by the nurse or midwife (some responded yes to both of these statements). In all, 20 (26%) infants had problems with cup feeding including inability of the infant to do it, frequent spills, dissatisfaction with cup feeds and unacceptably long feeding times.

Ten (13%) of the respondents did not like cup feeds and changed feeding method because of this. Nine (12%) respondents said that the staff refused to cup feed their infant. Collins 2004 reported that some infants became less satisfied with cup feeds and more difficult to feed by this method as they neared discharge, generally during the last week of their hospital stay. Because of this, if the mother could not be present to breastfeed, the infant would be tube fed. The criterion for discharge home was that the infant had to be on full sucking feeds. This may have contributed to increased length of stay in this study. However, the study author cautions that reliable data on this point were not collected (Collins 2004).

Episodes of infection

Three studies with 500 infants reported infection. Collins 2004 reported necrotising enterocolitis, Kliethermes 1999 reported infection not defined and Simmer 2016 reported late‐onset sepsis. All participants were from high‐income countries, and none of the trials nor the meta‐analysis showed a statistically significant difference in episodes of infection, with no heterogeneity (typical RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.42; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.11; low‐certainty evidence).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Breast feeding with supplemental feeds by other than bottle versus breast feeding with supplemental feeds by bottle (all trials), Outcome 11: Episodes of infection per infant

Subgroup analysis: trials conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries

Two trials were conducted in upper‐ to middle‐income countries: Rocha 2002 in Brazil and Yilmaz 2014 in Turkey. Meta‐analyses were limited and showed no substantial differences from the meta‐analysis of all trials together (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.9; Analysis 1.10). These studies did not report infection rates.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The results of this review indicate there is low‐ to moderate‐certainty evidence that the strategy of avoiding bottles while breastfeeds are being established among preterm infants may improve rates of full (exclusive) breastfeeding and any breastfeeding up to six months' postdischarge. Studies included in this review compared cup feeding, a tube alone approach or a novel teat versus bottle feeding with a conventional teat. Most of the evidence demonstrating improvements in the extent of breastfeeding (full or any) and the duration of breastfeeding (up to six months' postdischarge) was for cup feeding. Only one study assessed a tube alone strategy and reported improvements in all breastfeeding outcomes. There were no differences in breastfeeding outcomes with the novel teat. There were no other benefits or harms associated with the avoidance of bottles strategy, including length of hospital stay, days to reach full sucking feeds, weight gain and infection. Findings of the two trials that assessed cardiorespiratory stability suggest there may be improved stability with avoidance of bottles.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The trials reviewed provided no information on the volume of feed consumed compared with the volume prescribed neither on episodes of choking/gagging per feed. We found limited information on cardiorespiratory stability and parent and health professional satisfaction with the feeding method. No studies were conducted in low‐income countries, and two were completed in middle‐income countries. No reports described infants dissatisfied with tube or cup, except Collins 2004, in which adherence with cup feeding was poor. In contrast, cup feeding had not previously been used in Yilmaz 2014, and staff acceptance was high, with high adherence to the intervention. Both of the largest studies were cup‐feeding studies, but they were conducted in different populations and settings. Collins 2004 was conducted in a high‐income country in very and extremely preterm infants, whereas Yilmaz 2014 included moderate‐to‐late preterm infants in a high‐ to middle‐income country. Lang 1997 suggested that as preterm infants mature, they may be able to bottle‐feed with no interference with breastfeeds, but she cautions that the introduction of a bottle should occur only when breastfeeding is well established. Such a strategy might be more acceptable to staff and parents, but no RCTs have investigated this approach.

Quality of the evidence

We included in this review seven studies with 1152 infants. Blinding was not possible in any of the included studies and therefore was subject to caregiver influence. We graded the level of evidence for full breastfeeding and for any breastfeeding as low or moderate (Table 1). We graded the level of evidence for length of hospital stay and episodes of infection as low. We downgraded outcomes because of attrition, moderate to high heterogeneity and imprecision (wide CIs). The direction of effects of all included trials was consistent (favouring avoiding bottles) for breastfeeding outcomes, but the magnitude of effects in Kliethermes 1999 was inconsistent with that in the other studies. The most likely reason for this heterogeneity was the difference in the intervention provided or the poorer quality of the study. Kliethermes 1999 used supplemental feeding by tube, and Simmer 2016 a novel teat, whereas the remaining trials used supplemental feeds by cup. Heterogeneity was considerable between cup feeding studies that reported length of stay (Collins 2004; Yilmaz 2014), with length of stay increased by a mean of 10 days in Collins 2004, and no difference in Yilmaz 2014.

Potential biases in the review process

Assessment of risk of bias involves subjective judgements. Review authors therefore independently assessed studies and resolved disagreements through discussion (Higgins 2020). We attempted to identify all relevant studies by screening the reference lists of included trials and related reviews. One review author (CC) was an investigator for one study (Collins 2004). Another review author (JG) performed data extraction for this study.

The 2021 search did not include EMBASE or independent searches of trial registries, clinicaltrials.gov or https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform. All of these sources are recommended per Cochrane MECIR (https://community.cochrane.org/mecir-manual/standards-conduct-new-cochrane-intervention-reviews-c1-c75/performing-review-c24-c75/searching-studies-c24-c38). These issues mean that our search may have lacked sensitivity. Future updates of this review will include these sources.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We were unable to find any other reviews that addressed the effect of avoiding bottle feeds on the establishment of breastfeeding specifically in preterm infants. Nevertheless, the findings are broadly consistent with another Cochrane Review that assessed cup feeding versus other forms of supplemental feeding in term and preterm infants (Flint 2016). That review found improved rates of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge and any breastfeeding at six months of age among infants who received supplemental feeds with cups compared with bottles.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Avoiding the use of bottles when preterm infants need supplementary feeds probably increases the extent of any breastfeeding at discharge, and may improve any and full breastfeeding (exclusive) up to six months postdischarge. Most of the evidence demonstrating benefit was for cup feeding. Only one study used a tube feeding strategy. We are uncertain whether a tube alone approach to supplementing breastfeeds improves breastfeeding outcomes. We found evidence suggesting that a novel teat does not confer breastfeeding benefit.

Implications for research.

There is a need for well‐conducted studies of a tube‐alone strategy and other novel interventions that avoid the use of bottles. Such studies should evaluate breastfeeding prevalence on discharge home and at three months and six months postdischarge; length of hospital stay; weight gain; infection episodes; and infant, parent and staff satisfaction with the feeding method.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 September 2021 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The conclusions were not updated as there were no new studies. |

| 24 September 2021 | New search has been performed | We searched the literature to 24 September 2021; there were no new studies, no ongoing studies and 3 trials are awaiting classification. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2005 Review first published: Issue 4, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 February 2017 | Amended | Added external source of support. |

| 6 October 2016 | Amended | Author reinstated |

| 6 October 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Author reinstated |

| 24 August 2016 | New search has been performed | New searches conducted in July 2016 identified 2 new trials for inclusion. We added 'Summary of findings' tables. |

| 24 August 2016 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Addition of 2 new trials changed the conclusions regarding benefits of breastfeeding. We added infection as an outcome. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cochrane Neonatal: Colleen Ovelman, Jane Cracknell, and Michelle Fiander, for Managing Editorial support; Roger Soll and Bill McGuire, Co‐coordinating Editors, who provided editorial and administrative support. Carol Friesen, Information Specialist, for writing search strategies and conducting literature searches (2020); Colleen Ovelman for peer reviewing the strategy. Michelle Fiander, Information Specialist, for running an update the search (2021), writing the search methods and search results sections; updating the PRISMA flow diagram; and running the Screen4Me process.

William McGuire, Robert Boyle and Sarah Hodgkinson peer reviewed and offered feedback for this review.

We gratefully thank the authors of Kliethermes 1999; Gilks 2004; and Capdevila 2016 for providing additional information about their studies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy: CENTRAL 2021

The randomised controlled trial (RCT) filters were created using Cochrane's highly sensitive search strategies for identifying randomised trials (Higgins 2020). The neonatal filters were created and tested by the Cochrane Neonatal Information Specialist.

CENTRAL via CRS Web

| Cochrane CENTRAL (Via CRS) September 24, 2021 | ||

| 1 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Breast Feeding EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 2077 |

| 2 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Colostrum EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 131 |

| 3 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Milk, Human EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 1104 |

| 4 | (breastfeed* or breast feed* or breast fed or breastfed or breast milk or breastmilk* or colostrum or expressed breast milk or EBM or DBM or foremilk or hindmilk or ((human or breast* or mother* or MOM or expressed or maternal or donor*) ADJ3 (milk* or breastmilk*))) AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 13323 |

| 5 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 | 13324 |

| 6 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Bottle Feeding EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 238 |

| 7 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Enteral Nutrition EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 1941 |

| 8 | (bottle* or cup or cups or ((artificial or novel) and teat*) or (nasogastric and supplement*) or supplementary or novel teat* or conventional teat* or nipple* or gavage or tube or tubes or spoon* or dropper* or finger* or palada*) AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 40120 |

| 9 | #6 OR #7 OR #8 | 41454 |

| 10 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Feeding Methods EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 3572 |

| 11 | (feed* or fed) AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 51228 |

| 12 | #10 OR #11 | 52882 |

| 13 | #9 AND #12 | 5988 |

| 14 | (cupfeed* or bottle‐fed or bottle‐feed*) AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 506 |

| 15 | #14 OR #13 | 5988 |

| 16 | #15 AND #5 | 1087 |

| 17 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Infant, Newborn EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 17015 |

| 18 | infant or infants or infant's or "infant s" or infantile or infancy or newborn* or "new born" or "new borns" or "newly born" or neonat* or baby* or babies or premature or prematures or prematurity or preterm or preterms or "pre term" or premies or "low birth weight" or "low birthweight" or VLBW or LBW or ELBW or NICU AND CENTRAL:TARGET | 93258 |

| 19 | #18 OR #17 | 93258 |

| 20 | #19 AND #16 | 945 |

Appendix 2. Search strategy 2021: MEDLINE

| Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process, In‐Data‐Review & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) 1946 to September 23, 2021 | ||

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | exp Breast Feeding/ | 40341 |

| 2 | exp Colostrum/ | 6497 |

| 3 | exp Milk, Human/ | 20659 |

| 4 | (breastfeed* or breast feed* or breast fed or breastfed or breast milk or breastmilk* or colostrum or expressed breast milk or EBM or DBM or foremilk or hindmilk or ((human or breast* or mother* or MOM or expressed or maternal or donor*) adj3 (milk* or breastmilk*))).mp. | 96364 |

| 5 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 [Breast feeding] | 96364 |

| 6 | exp Bottle Feeding/ | 3908 |

| 7 | exp Enteral Nutrition/ | 20689 |

| 8 | (bottle* or cup or cups or ((artificial or novel) and teat*) or (nasogastric and supplement*) or supplementary or novel teat* or conventional teat* or nipple* or gavage or tube or tubes or spoon* or dropper* or finger* or palada*).mp. | 524365 |

| 9 | or/6‐8 [Bottle Feeding] | 538211 |

| 10 | exp Feeding Methods/ | 46058 |

| 11 | (feed* or fed).mp. | 733634 |

| 12 | or/10‐11 [Feeding] | 760222 |

| 13 | 9 and 12 [Bottle Feeding AND Feeding] | 50571 |

| 14 | (cupfeed* or bottle‐fed or bottle‐feed*).mp. | 5592 |

| 15 | 13 or 14 [Bottle Feeding AND Feeding; OR Cupfeed] | 50571 |

| 16 | 5 and 15 [Breast Feeding and Bottle Feeding; results before filters] | 7148 |

| 17 | exp infant, newborn/ | 635405 |

| 18 | (newborn* or new born or new borns or newly born or baby* or babies or premature or prematurity or preterm or pre term or low birth weight or low birthweight or VLBW or LBW or infant or infants or 'infant s' or infant's or infantile or infancy or neonat*).ti,ab. | 893843 |

| 19 | 17 or 18 [Neonatal terms] | 1181600 |

| 20 | randomized controlled trial.pt. | 544403 |

| 21 | controlled clinical trial.pt. | 94421 |

| 22 | randomized.ab. | 534840 |

| 23 | placebo.ab. | 221667 |

| 24 | drug therapy.fs. | 2377419 |

| 25 | randomly.ab. | 366417 |

| 26 | trial.ab. | 569160 |

| 27 | groups.ab. | 2249953 |

| 28 | or/20‐27 | 5125633 |

| 29 | exp animals/ not humans.sh. | 4889653 |

| 30 | 28 not 29 [RCT Filter, Cochrane] | 4458537 |

| 31 | 19 and 30 [Neonatal AND Cochrane RCT filter] | 201266 |

| 32 | randomi?ed.ti,ab. | 690773 |

| 33 | randomly.ti,ab. | 367295 |

| 34 | trial.ti,ab. | 662458 |

| 35 | groups.ti,ab. | 2276651 |

| 36 | ((single or doubl* or tripl* or treb*) and (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab. | 206627 |

| 37 | placebo*.ti,ab. | 228820 |

| 38 | or/32‐37 [Addtional RCT terms ] | 3241226 |

| 39 | 18 and 38 [Additional RCT terms & Neonatal Keywords] | 130633 |

| 40 | limit 39 to yr="2018 ‐Current" [RCT & Neonatal Keywords to identify records without MeSH] | 28152 |

| 41 | 31 or 40 [all neonatal & RCT filter terms] | 203663 |

| 42 | 16 and 41 [Results] | 1580 |

Appendix 3. Search strategy 2021: CINAHL

| CINAHL Ebsco September 24, 2021 | ||

| # | Query | Results |

| S5 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 | 269 |

| S4 | (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized OR randomised OR placebo OR clinical trials as topic OR randomly OR trial OR PT clinical trial) | 611,386 |

| S3 | (infant or infants or infantís or infantile or infancy or newborn* or "new born" or "new borns" or "newly born" or neonat* or baby* or babies or premature or prematures or prematurity or preterm or preterms or "pre term" or premies or "low birth weight" or "low birthweight" or VLBW or LBW) | 526,073 |

| S2 | (((bottle* or cup or cups or ((artificial or novel) and teat*) or (nasogastric and supplement*) or supplementary or novel teat* or conventional teat* or nipple* or gavage or tube or tubes or spoon* or dropper* or finger* or palada*) AND (feed* or fed)) OR (cupfeed* or bottle‐fed or bottle‐feed*) 10,585 | |

| S1 | (breastfeed* or breast feed* or breast fed or breastfed or breast milk or breastmilk* or colostrum or expressed breast milk or EBM or DBM or foremilk or hindmilk or ((human or breast* or mother* or MOM or expressed or maternal or donor*) N3 (milk* or breastmilk*)) | 40,292 |

Appendix 4. Search strategy 2020: ISRCTN

ISRCTN

June 19, 2020

Terms: avoidance bottle feeding within Participant age range: Neonate bottle breast feeding within Participant age range: Neonate cup feeding AND ( Participant age range: Neonate ) "tube feeding" AND breast* within Participant age range: Neonate "gavage feeding" AND breast* AND ( Participant age range: Neonate ) "spoon feeding" AND breast* AND ( Participant age range: Neonate ) "finger feeding" AND breast* AND ( Participant age range: Neonate ) "dropper feeding" AND breast* AND ( Participant age range: Neonate ) feeding AND avoid* AND breast* AND ( Participant age range: Neonate )

Results: 4

Appendix 5. Previous search methods

2016 Search

We used the criteria and standard methods of the Cochrane Collaboration and the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group (see the Cochrane Neonatal Group search strategy for specialized register).

We conducted a comprehensive search in July 2016 that included the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE via PubMed; Embase; and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), using the following search terms:

(cup feed* OR (cup AND feed) OR cupfeed* OR gavage OR (tube AND feed*) OR spoon OR dropper OR (finger AND feed*) OR paladai), plus database‐specific limiters for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and neonates.

We searched clinical trials registries for ongoing and recently completed trials (clinicaltrials.gov; the World Health Organization International Trials Registry and Platform www.whoint/ictrp/search/en/ and the ISRCTN Registry).

2008 Search

For the 2008 review, we searched of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2007, Issue 4) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (1950 to July week 1 2008); the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; 1982 to July week 1 2008); and Embase (1980 to 2008 week 28), using the following terms:

Medical subject headings (MeSH): breastfeeding; Milk, human; Lactation; Bottle Feeding; Intubation, Gastrointestinal. We used the following text words: Neonat$, Cup, Cup Feed*, Cupfeed*, Gavage, Gavage feed*, Tube feed*, Spoon, Dropper, Finger Feed*, Palada*. We did not restrict the search by language.

These terms were combined using AND with the following terms for RCTs and neonatal population: