The lack of methods for studying genes in an atrial and ventricular myocyte-specific manner in mice, in vivo, limits our understanding of chamber-specific effects of pathologies, such as atrial fibrillation, the most common cardiac arrhythmia in the United States.1 In theory, adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) could be engineered with atrial- or ventricular-specific promoters; however, a major limitation is the small amount of promoter and transgene DNA that can be inserted into the viral genome before it becomes so large that virus generation and transduction efficiency are impaired.2 Accordingly, here we aimed to develop new AAV9 platforms that maximize insert size by minimizing promoter size while still conferring chamber specificity in the healthy and diseased hearts.

After analyzing other potential chamber-specific genes, we selected the Nppa and Myl2 promoters to control transgene expression in atrial and ventricular myocytes, respectively. These promoters were selected for their robust chamber-specific expression in healthy mice at all ages, which is retained during pathology. Our analysis involved testing a group of serial truncations of the mouse Nppa and Myl2 promoters driving green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression in primary neonatal rat atrial and ventricular myocytes, with some of the truncations inserted into AAV9 vectors for testing, in vivo. Portions of the Nppa promoter (−425 nucleotides to +25 nucleotides) and the Myl2 promoter (−226 nucleotides to +36 nucleotides) were found to be the smallest regions of each promoter that exhibited the desired specificity (data not shown). To our knowledge, these are the smallest promoter fragments to achieve AAV9-mediated robust, cardiac chamber–specific expression.3

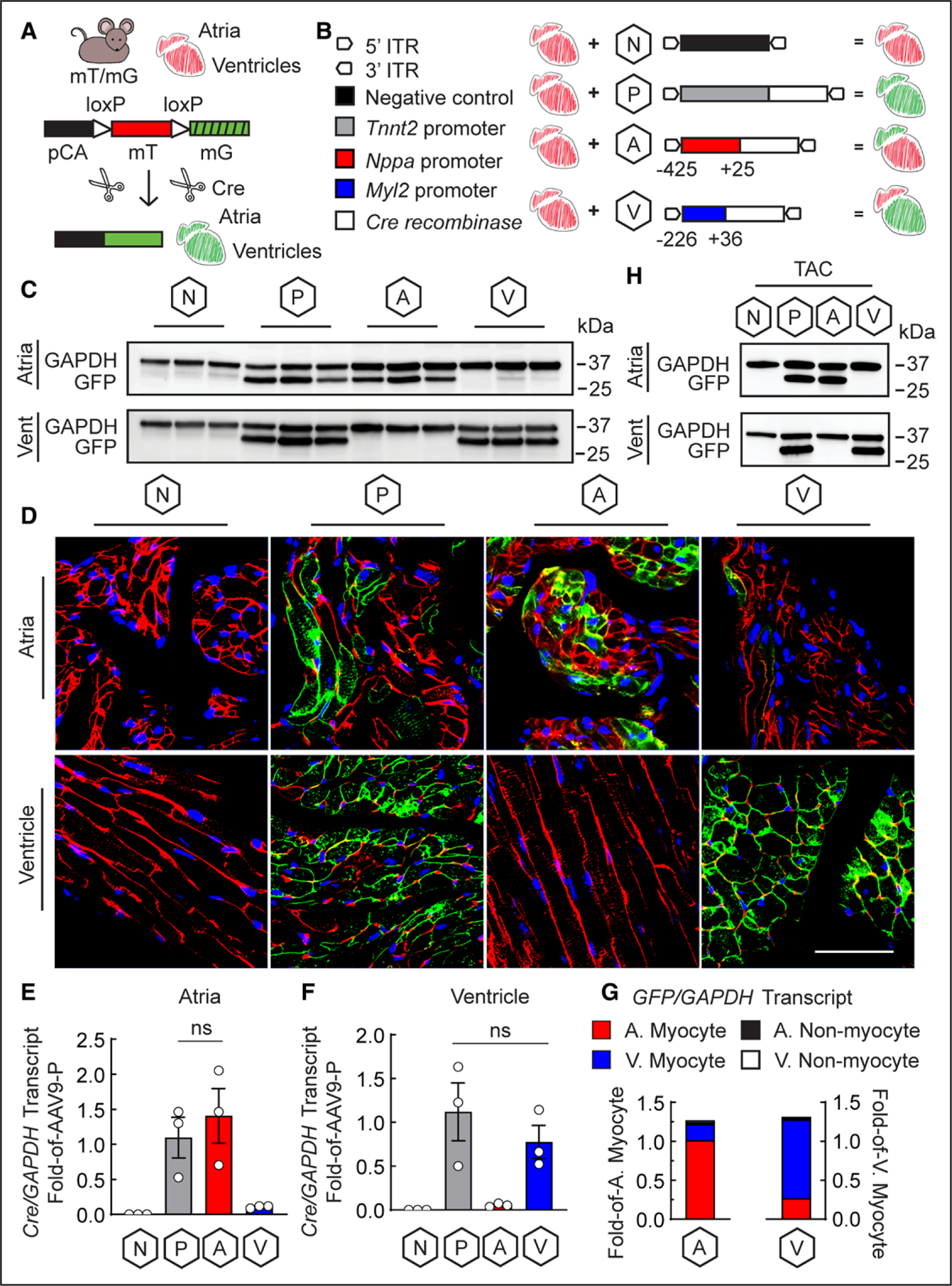

To examine chamber-specific activities of these promoters, in vivo, a double-fluorescent Cre-recombinase (Cre) reporter mouse (mT/mG) was obtained from Jackson Laboratories; they contain membrane-targeted forms of Tomato and GFP, driven by a chicken β-actin promoter and cytomegalovirus enhancer. Accordingly, every mT/mG mouse cell is Tomato positive until Cre introduction excises lox P sites flanking Tomato, removing Tomato and allowing GFP expression (Figure [A]). All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Figure. Minimal fragments of the Nppa and Myl2 promoters in an AAV9 vector mediate chamber-specific gene delivery.

A, Illustration of the mT/mG mouse transgene and mechanism of Cre-mediated excision and expression of Tomato (mT) and GFP (mG), respectively; pCA is the cytomegalovirus enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter; hashmarks indicate no expression of GFP without Cre-mediated excision of Tomato. B, Diagram of the AAV9-negative (N; AAV9-N) control vector4 driven by a distinct Myl2 promoter, AAV9-positive (P; AAV9-P) control vector driven by the Tnnt2 promoter, atrial-specific (A; AAV9-A) vector driven by the Nppa promoter, and ventricular-specific (V; AAV9-V) vector driven by the Myl2 promoter; Cre recombinase is expressed by AAV9-P, AAV9-A, and AAV9-V, whereas AAV9-N has no transgene. C, Immunoblot (n=3 animals for each group) and (D) Representative confocal fluorescence microscopy (n=3 images per chamber; n=1 animal per group) of GFP in atrial and ventricular extracts of mT/mG mice injected with AAV9-N, AAV9-P, AAV9-A, and AAV9-V; scale bar: 50 μm; blue: To-Pro-3 for nuclei; red: Tomato fluorescence. Cre transcript from (E) atrial and (F) ventricular extracts from mice injected with AAV9-N, AAV9-P, AAV9-A, and AAV9-V. n=3 animals per group; data are represented as mean±SEM; ns=not statistically significant, determined by 1-way ANOVA with P<0.05. G, GFP transcript from atrial and ventricular myocytes and nonmyocytes isolated from single hearts of mT/mG mice injected with AAV9-A or AAV9-V; A=atrial; V=ventricular; n=1 animal per group. H, Immunoblot of GFP in atrial and ventricular extracts of mT/mG mice injected with AAV9-N, AAV9-P, AAV9-A, and AAV9-V after 1 week of TAC; n=1 animal per group. AAV9 indicates adeno-associated virus serotype 9; GFP, green fluorescent protein; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; and TAC, transverse aortic constriction.

The minimal Nppa and Myl2 promoters were inserted into AAV9 vectors expressing Cre, generating AAV9-A or AAV9-V, respectively. As a positive control that expresses Cre in both atrial and ventricular myocytes, we used a well-characterized and robustly expressing AAV9 controlled by the Tnnt2 promoter4 (AAV9-P; Figure [B]). As a negative control, an AAV9 with an Myl2 promoter, distinct from that in AAV9-V and described previously,4 but no Cre insertion was used (AAV9-N). The viruses were administered by tail-vein injection into 8-week-old mT/mG mice, at 1×1011 viral particles per mouse. Viral titers were determined by densitometry analysis of AAV9 viral capsids against a virus of known titer. Two weeks after administration, atrial and ventricular extracts and sections were analyzed by immunoblot and confocal fluorescence microscopy for GFP as a measure of AAV9-mediated Cre expression, whereas Cre expression was measured directly by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

As expected, GFP was not expressed with AAV9-N but was robustly expressed in atria and ventricles with AAV9-P; meanwhile, AAV9-A and AAV9-V conferred striking atrial- and ventricular-specific patterns of GFP expression, respectively (Figure [C and D]). Similarly, Cre transcript was undetected with AAV9-N and robust with AAV9-P in atria and ventricles, as expected, whereas AAV9-A and AAV9-V showed significant Cre upregulation in atria and ventricles, respectively (Figure [E and F]). It is important to note that in their respective chambers, there was no significant difference in Cre upregulation by AAV9-P compared with AAV9-A and AAV9-V, indicative of their promoter strength.

To determine whether the chamber specificity of AAV9-A and AAV9-V was attributed to myocyte-specific expression, atrial and ventricular myocytes and nonmyocytes were isolated from adult mT/mG mouse hearts, as described previously.5 After injection with AAV9-A or AAV9-V, GFP was most abundantly expressed in atrial myocytes or ventricular myocytes, respectively, whereas being nearly undetectable in atrial and ventricular nonmyocytes (Figure [G]).

Because Nppa is upregulated in ventricular myocytes during many cardiac pathologies,4 transverse aortic constriction was performed on mT/mG mice injected with AAV9-N, AAV9-P, AAV9-A, and AAV9-V to examine whether the new AAV9 vectors retained chamber-specific expression in the setting of cardiac pathology. After 1 week of transverse aortic constriction, a time previously demonstrated to promote ventricular induction of Nppa,4 AAV9-A and AAV9-V conferred GFP expression only in the atria or ventricles, respectively (Figure [H]). As expected, GFP was undetected with AAV9-N and robustly expressed with AAV9-P in both chambers (Figure [H]).

The retention of chamber-specific expression in the setting of transverse aortic constriction has profound implications for atrial- and ventricular-specific studies in diseased hearts and not only in the context of atrial fibrillation. Specifically, the functional role of fetal gene upregulation in ventricular myocytes during left ventricular hypertrophy is largely unknown. Thus, these novel AAV9 vectors allow for genetic manipulation in atria and ventricles to further the understanding of cardiac disease. The data and tools used in this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants 1HL135893, 1HL141463, and 1HL149931 to Dr Glembotski and 1F31HL140850 to Dr Blackwood; the Inamori Foundation award to Dr Blackwood and Ms Bilal; and the Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Foundation, Inc, San Diego Chapter award to Dr Blackwood. Dr Blackwood is a Rees-Stealy Research Foundation Phillips Gausewitz, MD, Scholar of the San Diego State University Heart Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pellman J, Sheikh F. Atrial fibrillation: mechanisms, therapeutics, and future directions. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:649–665. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, Yang H, Colosi P. Effect of genome size on AAV vector packaging. Mol Ther. 2010;18:80–86. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zacchigna S, Zentilin L, Giacca M. Adeno-associated virus vectors as therapeutic and investigational tools in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2014;114:1827–1846. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackwood EA, Hofmann C, Santo Domingo M, Bilal AS, Sarakki A, Stauffer W, Arrieta A, Thuerauf DJ, Kolkhorst FW, Müller OJ, et al. ATF6 regulates cardiac hypertrophy by transcriptional induction of the mTORC1 activator, Rheb. Circ Res. 2019;124:79–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackwood EA, Bilal AS, Azizi K, Sarakki A, Glembotski CC. Simultaneous isolation and culture of atrial myocytes, ventricular myocytes, and nonmyocytes from an adult mouse heart. J Vis Exp. 2020;160:e61224. doi: 10.3791/61224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]