Abstract

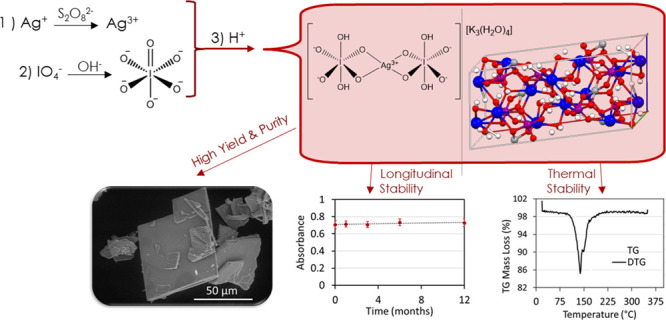

The preparation of stable hypervalent metal complexes containing Ag(III) has historically been challenging due to their propensity for reduction under ambient conditions. This work explores the preparation of a tripotassium silver bisperiodate complex as a tetrahydrate via chemical oxidation of the central silver atom and orthoperiodate chelation. The isolation of the chelate complex in high yield and purity was achieved via acidimetric titration. The comprehensive physiochemical characterization of the tribasic silver bisperiodate included single crystal X-ray diffraction, thermogravimetric and differential scanning calorimetry, and infrared and ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy. Infrared and UV–visible absorption spectra (λmax 255 and 365 nm) were in good agreement with historically prepared pentabasic diperiodatoargentate chelate complexes. The C2/c monoclinic distorted square planar structure of the bis-chelate complex affords a mutually supportive framework to both Ag(III) and I(VII), conferring stability under both thermal and long-term ambient conditions. Thermal analysis of the tribasic silver bisperiodate complex identified an endothermic mass loss, ΔH = +278.35 kJ/mol, observed at 139.0 °C corresponding to a solid-state reduction of silver from Ag(III) to Ag(I). Under ambient conditions, no significant degradation was observed over a 12 month period (P = 0.30) for the silver bisperiodate complex in a solid state, with an observed half-life of τ1/2 = 147 days in a pH-neutral aqueous solution.

1. Introduction

Interest in higher-oxidation-state or hypervalent silver complexes has been increasing due to their role as strong oxidants within organic and inorganic reactions and potential application as topical antimicrobials or disinfectants.1−5 Indeed, higher oxidation states of silver have been shown to effect 10–100 times greater antimicrobial and antibiofilm efficacy compared to lower-oxidation-state silver compounds.1,2 These hypervalent silver compounds demonstrate efficacy against a broad spectrum of yeast, fungi, and bacteria including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in both planktonic and biofilm states. However, the application of hypervalent complexes has historically been challenging due to the relative thermal instability and propensity for reduction under ambient conditions.6−9

Coordination complexes of Ag(III) are well studied in the literature.10,11 In the presence of periodate, anodic or chemical oxidation of silver in strongly alkaline media has yielded various pentabasic salts of a diperiodatoargentate (DPA) chelate complex in the form of M5[Ag(IO5OH)2]·nH2O, where M is Na or K and n = 3 to 16.9,12−14 In alkaline aqueous media, the DPA chelate complex is in a pentabasic form, where the bidentate orthoperiodate chelate is singly protonated. This alkaline DPA complex is known to act as a two-electron oxidant with a reduction potential of +1.74 V and is highly reactive with a propensity to oxidize inorganic and organic materials.15−17 In a solid state and within aqueous media, the stability of DPA complexes is limited. Masse and Simon report on the decomposition of the isolated compounds in air.9 The authors report that K5Ag(IO5OH)2·8H2O is only reasonably stable under strongly alkaline conditions. Balikungeri et al. also note that DPA complexes may only be prepared in highly basic media and the compounds decompose rapidly in neutral or acidic media.14 Spectrophotometric degradation kinetic experiments performed by Ilyas and Khan reveal that the rate of dissociation of the periodate ligands or hydrolysis of Na5Ag(IO5OH)2 significantly increased with increasing acidity, or [H+], of the solution.13 Inherently, these highly reactive DPA compounds confer excellent redox properties toward the oxidation of organic molecules conveying antimicrobial properties; however, their reactivity and instability under ambient conditions and physiologically relevant pH have limited their use.

In the current work, we describe the synthesis and isolation of a stable Ag(III) bisperiodate complex isolated from an aqueous solution at pH 6.8. To our knowledge, this is the first confirmed report of a conjugate acid of periodate (IO4(OH)2) octahedral ligand for the preparation of a stable tribasic silver bisperiodate tetrahydrate complex. Physiochemical characterization included single crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD), thermogravimetric (TG) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and infrared (IR) and ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy. The silver-chelate complex containing hypervalent Ag(III) and I(VII) stabilized in a distorted square planar geometry was also evaluated for long-term stability under ambient conditions in solution and solid state.

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis

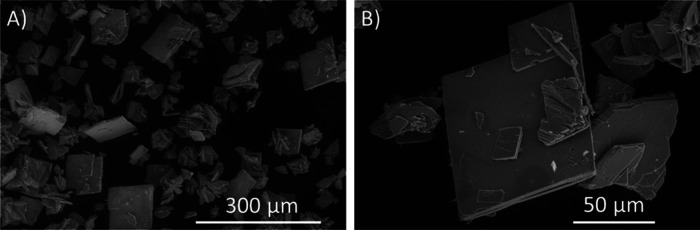

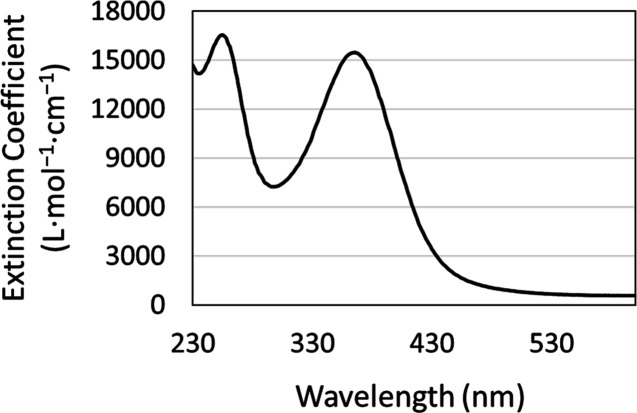

The tripotassium silver bisperiodate of the general formula K3AgBP (BP = bisperiodate = [IO4(OH)2]2) as a tetrahydrate ((H2O)4) was prepared via aqueous synthesis. Chemical oxidation by persulfate of the central silver atom and orthoperiodate chelation afford an argentic bisperiodate chelate complex. Acidimetric precipitation resulted in the isolation of a deep red tripotassium salt of the silver bisperiodate complex obtained in high yield as crystalline platelets as observed by SEM (Figure 1). Aqueous recrystallization of the K3AgBP compound was completed, affording single red crystalline platelets of 99.3% purity, UV–vis absorption maxima of λmax 255 and 365 nm as shown in Figure 2. These were utilized for all subsequent characterization and testing.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy images of solid-state products isolated from tribasic silver bisperiodate synthesis prior to recrystallization observed at (A) 500× magnification and (B) 2000× magnification. SEM was performed on an FEI Quanta FEG 250 ESEM in a low vacuum 70–130 Pa imaging at 5–10 eV.

Figure 2.

UV–visible absorption spectrum of the tripotassium silver (III) bisperiodate complex in reverse osmosis water, blank corrected.

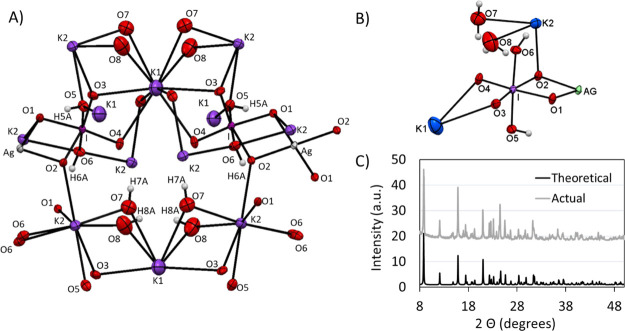

2.2. Crystal Structure

The solid-state lattice structure of K3AgBP was determined by single crystal X-ray diffractometry (Cambridge Crystallography Data Centre ID 2065363). The compound is a neutral potassium salt of the diperiodate argentate (III) complex, with the formula AgH4(IO6)2K3(H2O)4. The crystal corresponds to a monoclinic unit cell with a space group symmetry of C2/c. The cell constants are a = 20.3394(9) Å, b = 7.8242(3) Å, c = 9.5561(4) Å, α = 90°, β = 100.644(2)°, γ = 90°, and volume = 1494.59(11) Å3; details are in Tables S2 to S4. The unit cell is composed of two octahedral orthoperiodate ligands related via an inversion center on the central silver Ag(III) atom coordinated through two deprotonated hydroxy O atoms of each periodate as seen in Figure 3A,B. The structure also possesses three potassium atoms and four lattice H2O molecules within the crystal structure.

Figure 3.

(A) Symmetry-completed molecular structure for the tribasic silver bisperiodate (K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O) and (B) monoclinic asymmetric unit cell of the tribasic silver bisperiodate (K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O) showing a 50% probability of thermal ellipsoids. (C) Theoretical calculated vs actual X-ray diffraction pattern of K3AgH4(IO6)2(H2O)4. Theoretical pattern based upon the single crystal structure. Actual powder diffraction pattern obtained from the tribasic silver bisperiodate product as prepared by the methods described herein.

The asymmetric unit cell consists of two crystallographically independent potassium cations coordinated through oxygen atoms to one iodine and the silver cation. In addition, two water molecules are bridging both potassium atoms through the coordination μ1-η2 binding mode, while one hydroxide is coordinated to two potassium atoms and one iodine atom through the μ1-η3 bridging mode. Similarly, another bridging oxygen atom binds the potassium and iodine atoms through the μ1-η2 coordination type. Also, three bridging oxygen atoms are coordinated through various coordination modes in which two bridges form between potassium, iodine, and silver atoms through the coordination mode of μ1-η.3 Another bridging oxygen atom coordinates two potassium cations and one iodine in a similar type of coordination. In this structure, the silver is located at the special position of the center of inversion and the geometry is significantly distorted from square planar geometry with Ag–O bond lengths of 1.9725(11) and 1.9831(12) Å and O–Ag–O bond angles of 77.84(5) ° and 102.16(5) °. This observed distortion from square planar geometry is not dissimilar to historical argentic bidentate chelate complexes such as DPA and [Ag(III)en(bigH)2]SO4HSO2, with reported chelate bond angles of approximately 80 and 100 °, proposed to reflect a hybrid dsp2 type valence bond.9,11 These silver oxygen bond distances are ∼0.2 shorter than the Ag–O bond lengths found in the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) for square planar Ag(I) species. The potassium atoms are in distorted square antiprism geometry (K–O bond lengths are in the range of 2.8186(16)–3.0544(16) Å, while O–K–O bond angles are between 47.72(6) and 164.88(6) °), and the second potassium atom can be best described as distorted bicapped square antiprismatic (K–O bond lengths are in the range of 2.8186(14)–3.0544(15) Å, while O–K–O bond angles are between 53.55(3) and 169.07(6) °). The latter potassium atom is also located on a twofold axis. In addition to the numerous ionic interactions, an extensive set of hydrogen bonds stabilizes the lattice as well. As shown in Figure S1, this network includes not only the iodide bound hydroxide protons but the waters coordinated to the potassium cations. The key metric parameters for these hydrogen bonds are listed in Table S1. Finally, the iodine in this structure consists of six-coordination bonds with bond distances of 1.7872(13)–1.9206(12) Å and angles of 80.23(5)–177.34(6) ° as described in detail in Tables S5 and S6. These metric parameters for the orthoperiodate (IO65–) anion are well within the range found in the CSD for similar I–O bond lengths, i.e., 1.878–1.906 Å. The overall structure leads to the formation of a 3D coordination framework with an associated 2D powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern analogous to the experimental powder diffraction pattern, as seen in Figure 3C, for the K3AgBP synthesized herein.

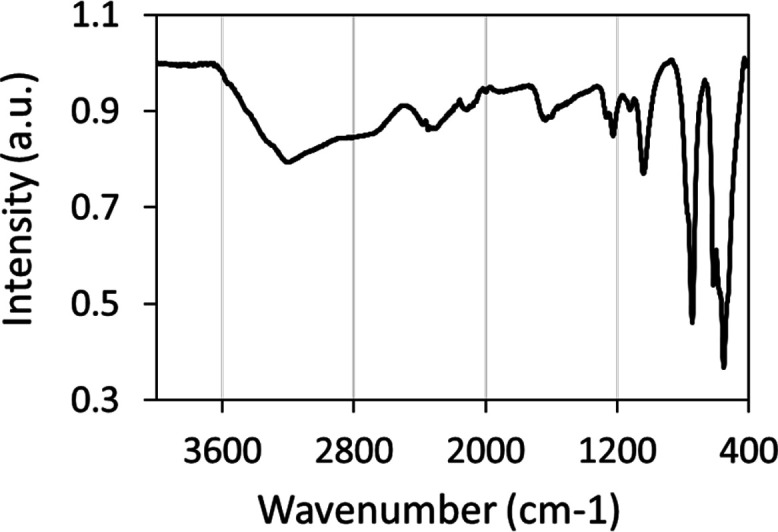

2.3. FTIR

The Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum of the K3AgBP solid product is shown in Figure 4 and summarized in Table S7. As is anticipated for hydrogen bonding effects associated with water, the strong and broad infrared bands around 3205 and 1635 cm–1 are assigned to stretching ν(OH) and bending δ(HOH) modes, respectively, for this hydrated complex. Moderately intense bands near 2305 and 2115 cm–1 may originate from the ν(OH) stretching of strongly hydrogen-bonded groups or derive from bending δ(IOH) modes. Vibrational bands near 1265 and 1125 cm–1 are also associated with bending δ(IOH) modes. These vibrational frequencies are in good agreement with previous assignments of hydrogen bonding modes in metal bisperiodate complexes.14,18 The two bands at 1140 and 1225 cm–1 likely arise from asymmetric bending δas(AgOH) modes. Asymmetric νas(I=O) stretches, observed between 773 and 528 cm–1 in the K3AgBP IR spectra, are the most prominent vibrations and are in good agreement with vibrational frequencies observed by Dengel et al. for bidentate orthoperiodate ligand complexes.18 Within the 400–650 cm–1 region, contributions from νs(I=O), νas(AgO), and νs(AgO) are also anticipated as outlined in Table S7.

Figure 4.

Fourier-transform infrared spectra of the tripotassium silver (III) bisperiodate complex.

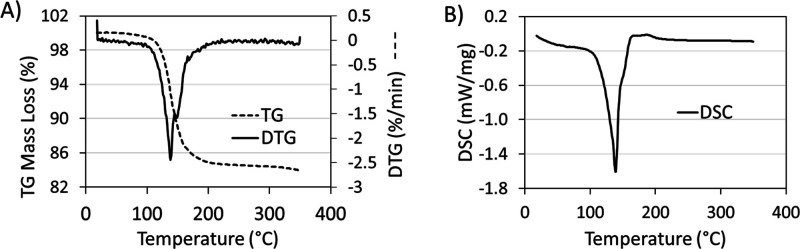

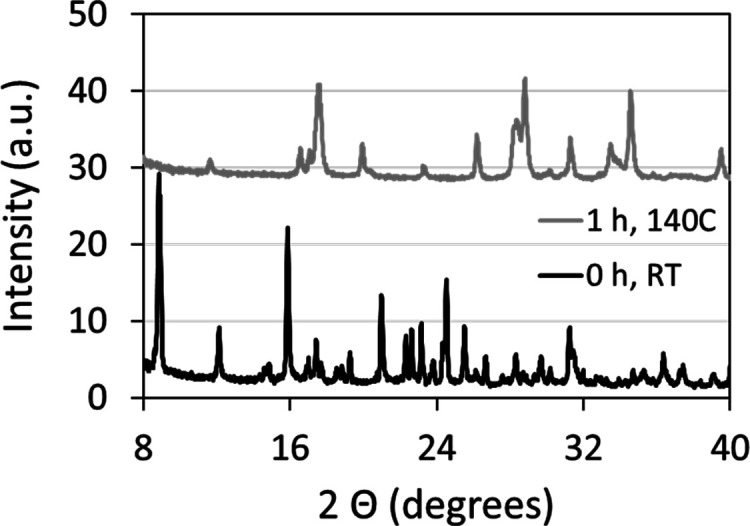

2.4. Thermal Studies

Simultaneous TG-DSC studies of the K3AgBP solid samples were carried out under oxidizing conditions. As observed in the thermogravimetric plot, shown in Figure 5A, a mass loss was observed to begin at an onset temperature of 125.8 °C with an associated set of inflections observed in the first derivative (DTG) plot at 138.3 and 148.7 °C. This mass loss corresponds to an endothermic peak maximum observed in the DSC at 139.0 °C and a shoulder at 156.4 °C. The entirety of this transition was determined to have an endothermic enthalpy; ΔH = + 278.35 kJ/mol. No subsequent mass or energy transitions were observed through to the final temperature of 350 °C. At the terminus of the analysis, the residual mass was 83.97%. Complementing the TG-DSC studies, PXRD of the K3AgBP solid samples was observed prior to and following thermal treatment at 140 °C for a duration of 1 h. Prior to thermal treatment, the PXRD pattern for the K3AgBP solid samples as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 3C is in good agreement with the diffraction pattern determined for the single crystal K3AgBP. Following thermal treatment, a clear transition from the original powder diffraction pattern to a secondary unique pattern is observed. Subsections of the diffraction pattern, after thermal treatment, contain peaks in good agreement with standard KIO3 and Ag5IO6 diffraction peaks (COD Card 1509923) as shown in Figure S2.19

Figure 5.

(A) Thermogravimetric plot with first derivative curves and (B) differential scanning calorimetric curves of the thermal degradation of the tripotassium silver (III) bisperiodate complex over a heating rate of 5 °C/min from room temperature to 350 °C under oxygen flow.

Figure 6.

Powder X-ray diffraction of synthesized solid-state tribasic silver bisperiodate prior to (black pattern; 0 h, RT) and following (gray pattern; 1 h, 140 °C) thermal degradation under ambient atmosphere at 140 °C for a period of 1 h.

3. Discussion

Coordination complexes of bivalent or trivalent silver are well documented in the literature.10,11 The oxidation of monovalent silver, Ag(I), to a hypervalent silver, Ag(II) or Ag(III), in the presence of fluorides, complexing agents such as periodate and tellurate, or nitrogenous ligands such as biguanide and its derivatives is known to form complexes of Ag(II/III). The unusual oxidation state of Ag(III) has previously been reported for other coordination complexes such as porphyrins20,21 and tetraaza macrocycles ligands22,23 as well as within alkaline periodate complexes.12 Periodate, having an expanded octahedral coordination sphere in alkaline aqueous media, is a known electron-donating ligand. As (IO5(OH))4– or (HIO6)4–, the basic orthoperiodate anion is known to function as a ligand for a number of transition metals, often stabilizing unusually high oxidation states of the metal to which it coordinates. This orthoperiodate ligand (IO6)−5 has been observed mostly in A-type Anderson clusters of molybdoperiodate [IMo6O24].5,24−29 Meanwhile, Rice et al. reported an unusual complex where the oxygens in the (IO6)−5 anion are coordinated to four Cu(II) ions.30 In the presence of periodate, anodic or chemical oxidation of silver in alkaline media has yielded various pentabasic DPA salts through bidentate coordination of the basic (HIO6)4– ligand to argentic, Ag(III), silver.9,14,18,31 These DPA complexes are prepared exclusively in basic media and are notoriously unstable in isolation and in aqueous media, exhibiting rapid degradation in neutral or acidic media.9,14 In their synthesis of K5Ag(IO5OH)2·8H2O, Masse and Simon note that solutions of the pentapotassium DPA complex are only stable in basic media (pH > 9) and that the solid compound slowly decomposes in air, necessitating handling under argon to prevent degradation.9 Spectrophotometric absorbance experiments performed by Ilyas and Khan revealed that the hydrolysis or degradation kinetics of Na5Ag(IO5OH)2 (λmax = 362 nm), in neutral and acidic aqueous solutions, follow a two-stage hydrolysis: k1 1.7 × 10–5 s–1 and k2 2.4 × 10–5 s–1.13 Silver bisperiodate complexes, therefore, have historically been prepared exclusively in highly basic media affording diperiodatoargentate pentabasic salts.

The structure and protonation states of periodate and its conjugate acids have been under debate for several decades.32−34 Most recently, Valkai and his co-workers demonstrated a stepwise deprotonation of orthoperiodic acid,eqs 1 to 3, without evidence for an ortho-meta periodate equilibrium or dimerization of the ligand as suggested in prior works.34,35

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Although the study of the protonation state of periodic acid has been extensive, investigations into the protonation states of periodate within a metal ligand complex have been limited.9,12,14 Early works by Cohen and Atkinson describe the preparation of Ag(III) complexes with periodate in basic solution.12 In these works, the authors briefly describe the synthesis and isolation of an orange crystalline product proposed as K3H4Ag(IO6)2·3H2O by elemental analysis. However, no further characterization or evaluation of this compound was completed. Balikungeri and co-workers investigated stoichiometric equivalents and electronic charge on metal periodate complexes through the use of molar conductivity of the pentasodium DPA complex.14 The isolated DPA complex had a conductivity of 610 Ω–1 cm2 mol–1, confirming that there were no protons liberated from the periodate complex where this phenomenon would have resulted in an effective molar conductivity of 1300 Ω–1 cm2 mol–1. This work indicated a nonacidic proton bound to each periodate (I–OH) ligand with a complex formula of [Ag(HIO6)2]Na5.14 This proposed structure of the pentabasic bisperiodate ligand complex was verified by later single crystal X-ray diffractometry investigations by Masse and Simon, wherein a distorted square planar coordination of diperiodato ligands to dsp2 type Ag(III) was established. Although XRD will not provide the direct spatial location of hydrogen atoms, Masse and Simon deduced the positions of the OH groups as both anterior and orthogonal to the square coordination plane through close inspection of the O–O and O–I interatomic distances of the noncentrosymmetric crystal structure.9

In this study, we describe a novel two-step chemical oxidation–chelation followed by acidimetric precipitation method for the preparation of a stable Ag(III) bis-complex of the conjugate acid of periodate [IO4(OH)23–] isolated from a neutral aqueous solution (pH 6.8) in high yield. The tripotassium silver bisperiodate of the general formula K3AgBP (BP = (IO4(OH)2)2) was isolated as a tetrahydrate ((H2O)4) as verified by the silver content analysis, 14.6 wt/wt % Ag, and single crystal XRD as shown in Figure 3A. Similar to previous findings by Masse and Simon for the pentabasic DPA complex, the unit cell of the tribasic K3AgBP complex crystallized in a monoclinic system.9 Atomic arrangement in space group C2/c, a = 20.3394(9) Å, b = 7.8242(3) Å, and c = 9.5561(4) Å, with dual bis-orthoperiodate ligands stabilizing Ag(III) located at the special position of the center of inversion, slightly distorted from square planar geometry. The refined structure (goodness-of-fit on F2 = 0.991, wR2 = 0.0589 as seen in Table S2) confirms that the isolated silver bisperiodate is the conjugate acid tripotassium salt with both the silver, Ag(III), and iodine, I(VII), in hypervalent oxidation states. Vibrational modes observed in the FTIR spectrum of K3AgBP are in good agreement with previous infrared studies of metal periodato complexes with notable variations in the 400–650 cm–1 region.14,18 Within this region, vibrational IR mode contributions from νs(I=O) may be diminished for K3AgBP resulting from the increased symmetry of the conjugate acid bisperiodate with an orthogonally protonated I–O–H chelate structure as seen in Figure 3B versus the syn-periplanar protonation of DPA as determined by Mass and Simon.9 This orthogonal protonation structure is ascertained through inspection of the I–O bond lengths of the IO6 octahedra. The distorted square planar geometry of the periodate octahedra around the metal chelate is attributed to the repulsion between silver and iodine and is anticipated to lengthen the I–O distances adjacent to silver, as observed in dI-O1 = 1.930 Å and dI-O2 = 1.927 Å. However, the longer bond lengths of dI-O5 = 1.907 Å and dI-O6 = 1.921 Å versus the planar dI-O3 = 1.799 Å and dI-O4 = 1.787 Å are indicative of symmetrical, orthogonal protonation. The absorbance maxima of the UV–vis spectra for K3AgBP exhibit characteristic metal–ligand charge transfer (MLCT; λmax = 255 and 365 nm) bands observed for silver bisperiodate complexes, with a slight bathochromic shift observed in comparison to previous studies for the pentabasic DPA, λ = 362 nm observed by Cohen and Atkinson and λ = 363 nm observed by Balikungeri and co-workers, indicative of minor variations to the electronic environment conducive to protonation.12,14

Inclusive of periodate complexes of Ag(III) as described above, hypervalent silver complexes are known for instability to light, air, and heat in addition to moisture sensitivity.5,7−9,13 Silver oxynitrate, containing silver in Ag(I), Ag(II), and Ag(III) with an average valence of Ag+2.67, is known to degrade rapidly in water and undergo an exothermic heat of decomposition with an initiation temperature of 85 °C.5,6,8 This low heat of thermal degradation, in association with sensitivity to light and moisture, poses challenges for the integration of the solid-state material into various applications including biomedical technologies.6,36 The increased thermal and chemical stability of hypervalent silvers may therefore address these challenges and enhance the utility of hypervalent compounds. Contrary to previous studies reporting on the stability of pentabasic DPA complexes, the K3AgBP complex prepared within these works demonstrates exceptional thermal and temporal stability in both solid-state and pH-neutral aqueous solutions. The gravimetric and calorimetric thermal profile of the K3AgBP complex was observed via TG-DSC as shown in Figure 5 and summarized in Table 1. Within the thermogravimetric analysis, mass loss was observed at an onset temperature of 125.8 °C corresponding to an endothermic transition in the DSC with a peak maximum of 139 °C. Although historical TG-DSC data for silver bisperiodate compounds are lacking, the initiation temperature observed for K3AgBP degradation is considerably higher than that of silver oxynitrate, exemplifying an enhanced thermal stability of the bis-chelate complex.8 The observed endothermic transition is associated with an enthalpy of ΔH = + 278.35 kJ/mol and a mass loss of 16.03 wt/wt %. Endothermic mass loss upon heating may be expected for a hydrated metal chelate where K3AgBP, as a tetrahydrate, contains 9.65 wt/wt % water and would account for 60% of the mass loss observed in the heating ramp. Toward elucidating the resultant products of this endothermic transition, the solid-state powder XRD patterns of K3AgBP before and after thermal treatment (1 h at 140 °C) were observed as shown in Figure 6. Prior to thermal treatment, the K3AgBP diffraction pattern was in good agreement with the calculated diffraction pattern generated from the monoclinic single crystal structure as seen in Figure 3C. Following thermal treatment, a distinct loss of the original K3AgBP diffraction pattern was noted in Figure 6 where the resultant diffraction pattern is in good agreement with pentasilver periodate (Ag5IO6, COD Card 1509923), potassium iodate (KIO3), minor contributions of potassium iodide (KI), and an unidentified fourth set of patterns, as shown in Figure S2; further works are pending to fully elucidate the mechanism and products of thermal decomposition. The formation of these thermal degradation products would result in a loss of absorptivity in the UV–vis spectra of K3AgBP as they do not exhibit MLCT contributions. With an onset thermal degradation temperature of 125.8 °C, we sought to explore the long-term stability of K3AgBP through UV–vis spectroscopic studies over the course of 5 months in the solution phase and 1 year in the solid state under ambient light, temperature, air, and humidity. At discrete intervals, UV–vis spectra were collected at a specified concentration of 81.0 ± 0.7 μM. In the solid state, no measurable shift in λmax or decrease in absorbance for the K3AgBP complex was observed over the study time frame, as shown in Figure S3. This is evidential of insignificant degradation and K3AgBP stability under ambient conditions over a 1 yr period. In addition, stability of the complex in an aqueous solution, pH 6.91, was observed over 5 months under ambient light and heat. Over this time course, a slow first-order degradation, k = 4.14–11 mol/L/s, was observed in the solution, dissimilar to the rapid two-stage hydrolysis of DPA in a neutral aqueous solution as reported by Ilyas and Khan.13 Meanwhile, the aqueous stability of K3AgBP in the solution, determined herein from linear least square regression, was observed as a half-life of τ1/2 = 147 days, as shown in Figure S4.

Table 1. Summary of TGA-DSC Results for the Thermal Degradation of Tripotassium Silver (III) Bisperiodate Complex over a Heating Rate of 5 °C/min from Room Temperature to 350 °C under Oxygen Flow.

DTG peak values.

The rationale for the observed enhancement of stability for this tribasic silver bisperiodate complex is speculative. Historically, the presence of water molecules within a crystal structure is known to impact the intermolecular interactions (internal energy and enthalpy) and the degree of crystalline disorder (entropy).37 Hydrated molecules, or solvates, form hydrogen bonds that coordinate within a crystal lattice, as reported herein for the tetrahydrate K3AgBP complex. These coordinated hydrogen bonds may result in new X-ray powder diffraction patterns due to differences in crystal structure, i.e., polymorphic solvates.37 As a result, physicochemical properties affected by solvation include solubility, dissolution rate, stability, and bioavailability. Herein, our results indicate an augmented stability for the K3AgBP tetrahydrate complex, relative to the pentabasic diperiodatoargentate and other hypervalent silver complexes, under ambient air, light, heat, and moisture. Although further works are under way to determine the origin of this stability, this study suggests that the conjugate acid of periodate as a chelate for Ag(III) offers a practical advantage for the integration of Ag(III) bisperiodate complexes into various applications inclusive of antimicrobial technologies and devices.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Chemical reagents: Silver nitrate (AgNO3, ACS reagent grade, ≥99.0%), nitric acid (HNO3, ACS reagent grade, 68–70%), potassium metaperiodate (KIO4, ACS reagent grade, ≥99.8%), periodic acid (H5IO6, ACS reagent grade, 99%), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, 99.95–100.05% ACS primary standard), potassium hydrogen phthalate (KHP, C8H5KO4, 99.99%, acidimetric standard), and acetone ((CH3)2CO, ACS reagent grade, 99.5%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, United States; potassium persulfate (K2S2O8, ACS reagent grade, ≥99.0%) was obtained from VWR, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. All reagents were used without further purification. Unless otherwise mentioned, reverse osmosis (RO) water was used for all experimental procedures.

4.2. Equipment

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed on an FEI Quanta FEG 250 ESEM (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States) variable pressure and environmental scanning instrument housed in the Centre for Nanostructured Imaging at the University of Toronto. SEM was performed in a low vacuum 70–130 Pa imaging at 5–10 eV. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was performed on the same FEI Quanta FEG 250 ESEM instrument under the equivalent conditions. Postprocessing EDX analysis was performed using the TEAM: Texture & Elemental Analytical Microscopy software. pH titration was performed on a PC800 pH/conductivity meter (Apera Instruments, Columbus, Ohio, United States) housed at Exciton Technologies Inc., Toronto, Ontario. UV–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy was performed on a Synergy Neo2 HTS Hybrid Multi-Mode Plate Reader (Bio Tek, Winooski, Vermont, United States) housed at the Structural & Biophysical Core Facility at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Ontario. FTIR spectroscopy was performed on the iS50 with attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States) housed at the Analest Facility at the University of Toronto. Thermogravimetric and differential scanning calorimetry (TG/DSC) was performed on a Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer STA 449 F3 Jupiter (NETZSCH, Selb, Germany) housed at the Walter Curlook Laboratory at the University of Toronto. Single crystal XRD was performed on a SMART CCD or BRUKER APEX-II CCD diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, Massachusetts, United States) housed at the Department of Chemistry at McGill University. X-ray diffraction was completed using graphite-monochromated Mo radiation (Kα λ = 0.71073 Å). The SAINT7 program was used for integration of the intensity reflections and scaling, and the SADABS8 program was used for absorption correction. Powder X-ray diffractometry (PXRD) was performed on a Bruker D2 Phaser (Exciton Technologies Inc., Edmonton, Alberta) with Cu Kα 1.54060 A, divergence slit 0.6 mm, air scatter shield 3 mm, air scatter slit 8 mm, step size 0.010°, and step time 42 s. Data analysis was performed using the DIFFRAC EVA V4.1.1 software, inclusive of postprocessing stripping of Cu Kα2.

4.3. Synthesis

Tripotassium silver bisperiodate was prepared by chemical oxidation in aqueous media. In brief, 10 mL of a 5.0 M solution of silver nitrate was added to a stirring solution of potassium persulfate (0.5 M, 240 mL) heated to 40 °C. Following a 10 min reaction time, 50 mL of a 10 N KOH basic solution of potassium periodate (2.2 M KIO4) was added to the stirring silver persulfate solution. The resultant red-brown turbid solution was stirred at 80 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, the turbid solution was filtered through a fine glass frit under reduced pressure (22 mmHg) and the clear red filtrate was titrated with a 2 N HNO3 solution to a final pH of 6.81, resulting in the precipitation of the red-orange tripotassium silver bisperiodate as a tetrahydrate. The suspension was filtered through a medium glass frit under reduced pressure (22 mmHg) rinsing with cold water then acetone and dried, affording a red-orange powder of tripotassium silver bisperiodate (47.5 mmol, 95% yield). Recrystallization of this powder from the aqueous solution at 50 ° C produced bright red-orange platelets of K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O in 99.3% purity: 14.3 wt/wt % Ag as evaluated by potentiometric titration as described below, UV–vis λmax 255 nm (ε = 1.62 × 104 M–1 cm–1), λmax 365 nm (ε = 1.56 × 104 M–1 cm–1).

4.4. Silver Quantification

Quantitative determination of the percent silver content by mass of tripotassium silver bisperiodate was completed in triplicate by potentiometric titration against sodium chloride (NaCl). In brief, samples (0.25 g) of the higher-oxidation-state silver compounds were digested in approximately 25 mL of dilute nitric acid (1:4, HNO3/H2O) overnight. This digested solution was then quantitatively transferred to a 250 mL volumetric flask and diluted with RO water. A 5.0 mL aliquot of this solution was quantitatively transferred to a 50 mL sample vial containing 10 mL of dilute nitric acid (1:4, HNO3/H2O) and 20 mL of water. The potential was measured across the analyte solution over the duration of titration with a 0.1 M NaCl titrant. The silver content of the sample volume was determined from the second derivative of the potential voltage plotted versus titrant volume at an equimolar ratio of silver to chloride. In this manner, the mass percent silver content of tripotassium silver bisperiodate was determined.

4.5. Single Crystal X-Ray Diffractometry

A single crystal of the tribasic silver bisperiodate was mounted on a glass fiber with epoxy resin or Mitegen mounts using Paratone-N from Hampton Research. The single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements were obtained. The structure was solved by intrinsic phasing. All nonhydrogen atoms were located by difference Fourier maps, and final solution refinements were solved by the full-matrix least-squares method on F2 of all data by using the SHELXTL7 software. The hydrogen atoms were placed at locations found in the final electron density difference map but were not refined. The final anisotropic full-matrix least-squares refinement on F2 with 102 variables converged at R1 = 2.23%. The goodness-of-fit, Sgof, was 0.991. Crystallographic and experimental details of data collection and crystal structure determinations are presented in Tables S2 through S6.

4.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy

The size, morphology, and compositional analysis of the tribasic silver bisperiodate powder prior to recrystallization were imaged using a scanning electron microscope under low vacuum and subjected to energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy for elemental analysis.

4.7. Thermogravimetric and Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Simultaneous thermal gravimetric and differential scanning calorimetric analysis of the tribasic silver bisperiodate was performed under an oxygen environment. In brief, a 20.25 mg sample was weighed onto an aluminum crucible and loaded into the TG/DSC under a flow (25 mL/min) of high-purity oxygen. Samples were heated at 5 °C/min to 350 °C. TG and DSC baselines were corrected by subtraction of a predetermined baseline completed under equivalent experimental conditions except for the absence of a sample using a blank crucible. Data analysis was completed using the Netzsch Proteus and Themokinetics software.

4.8. Longitudinal Stability

The long-term stability of the tripotassium silver bisperiodate was determined both in the solid state and as a solution in aqueous media. In brief, solid-state samples of tripotassium silver bisperiodate stored in a clear glass jar with a screw-cap lid were observed over the course of 1 year under ambient light, heat, and humidity conditions through periodic observation of the UV–vis spectra from 230 to 600 nm. At time points of 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, fresh solutions of the tripotassium silver bisperiodate were prepared in triplicate in RO water to a final concentration of 81.0 ± 0.7 μM. UV–vis spectra were collected in triplicate for each sample within the spectral range of 230–600 nm for each time point over the course of 1 year. The solution-phase stability of tripotassium silver bisperiodate was determined in RO water at a concentration of 81.0 ± 0.7 μM (pH 6.91), prepared in triplicate and stored in a clear glass vessel under ambient light and heat over 5 months. The solution phase stability, calculated as λmax 365 nm observed at each time point relative to the baseline, was monitored by the UV–vis spectrum collected for each sample within the spectral range of 230–600 nm at periodic intervals over a 5 month time frame.

4.9. Solid-State Thermal Degradation

The solid-state crystalline structure of the tribasic silver bisperiodate was observed prior to and following thermal degradation under ambient atmosphere in an oven, preheated to 140 °C, for a period of 1 h. Oven temperatures were verified via a calibrated thermometer (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) certified). X-ray diffraction was performed as follows: In brief, approximately 0.5 g of the tribasic silver bisperiodate both prior to and following thermal degradation was placed evenly into the depression in the powder XRD sample holder, placed into the X-ray diffractometer, and measured from 10 to 90° 2Θ recorded over 30 min. From crystal lattice structure diffraction patterns, the crystalline solid-state composition of the samples was determined. Degradation products were identified using XRD spectra, deferring to the Crystallography Open Database (COD) for identification of solid state diffraction patterns.19

4.10. Infrared Spectroscopy

Infrared spectra of the tripotassium silver bisperiodate were recorded using a Perkin Elmer UATR Single Bounce with Diamond Crystal Pike Technologies VeeMax II variable angle ATR mounted onto the iS50 FTIR spectrometer. The spectra of the silver bisperiodate samples collected in the 400–4000 cm–1 range with a resolution of 2 cm–1 were obtained (32 scans). Baselines were corrected by subtraction of a predetermined baseline completed under equivalent experimental conditions except for the absence of a sample. Data analysis was completed using the OMNIC software including an automatic spectral smoothing to reduce the inherent noise associated with the diamond crystal in the 2000–2500 cm–1 range.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

The data are represented as mean standard error, and n ≥ 3. All the experiments were performed in replicates as indicated, and statistical analysis was performed. The two-sample Student t test was applied to determine the significant difference among the groups with two paired distributions.

Acknowledgments

Greg Wasney & the Core Facility for Structural and Biophysical Sciences, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario. Dr. Cobas Acosta and the Walter Curlook Laboratory at the University of Toronto. Dr. Jared Mudrik and the Analest Facility in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Toronto. Ilya Gourevich and the Centre for Nanostructure Imaging in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Toronto.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- XRD

X-ray diffraction

- IR

infrared

- UV–vis

ultraviolet–visible

- FTIR

Fourier-transform infrared

- ATR

attenuated total reflection

- TG

thermogravimetric

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- DTG

first derivative thermogravimetry

- DPA

pentabasic diperiodatoargentate

- MLCT

metal–ligand charge transfer

- EDX

energy-dispersive X-ray

- PXRD

powder X-ray diffractometry

- COD

Crystallography Open Database

- NIST

National Institute of Standards and Technology

- CSD

Cambridge Structural Database

- ROH2O

reverse osmosis water

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c03523.

Figure S1. Hydrogen bonding network in compound K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O. Table S1. Hydrogen bonding metrical data in K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O. Table S2. Crystal and experimental data collected at 298(2) K for the compound K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O. Table S3. Fractional atomic coordinates (×104) and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2 × 103) for K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O. U(eq) is defined as one-third of the trace of the orthogonalized UIJ tensor. Table S4. Anisotropic displacement parameters (Å2 × 103) for K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O. The anisotropic displacement factor exponent takes the form: −2π2[h2a*2U11 + 2hka*b*U12 + ...]. Table S5. Bond lengths for the compound K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O. Table S6. Experimental angles obtained for the compound K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O. Table S7. Experimental vibrational frequencies observed and related assignments for the compound K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O. Figure S2. Powder X-ray diffraction of solid-state products isolated from tribasic silver (III) bisperiodate synthetic process prior to (green pattern; 0 h, RT) and post (red pattern; 1 h, 140 °C) thermal degradation under ambient atmosphere at 140 °C for a period of 1 h. Figure S3. Longitudinal stability of K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O in the solid state observed over 12 months via UV–vis spectroscopy. Figure S4. Longitudinal stability of K3Ag(IO4(OH)2)2·4H2O in an aqueous solution observed over 5 months via UV–vis spectroscopy (PDF)

Detailed crystallographic information on K3AgBP (CIF)

Author Contributions

C.J.S., D.S.B., and R.P. designed the research program and secured research funds. J.E.N.-A. and C.J.S. performed the syntheses and prepared samples. C.J.S., J.E.N.-A., E.D.G., C.G., and D.S.B. performed the research. Each author analyzed the data. The manuscript was written through contributions from all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Student Work Placement Program through BioTalent Canada (C2FJI-K565E-2REBV-JS3DH) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Engage grant with Dr. Scott Bohle at McGill University (EGP 543393-19).

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): At the time of this work, Carla Jehan Spin, Johanny E. Notarandrea-Alfonzo and Rod Precht were employed by Exciton Pharma Corp.

Notes

At the time of this work, C.J.S., J.E.N.-A., and R.P. were employed by Exciton Pharma Corp.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lemire J. A.; Kalan L.; Bradu A.; Turner R. J. Silver oxynitrate, an unexplored silver compound with antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4031–4039. 10.1128/AAC.05177-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Liu J.; Shi H. G.; Zhang W.; Qu W.; Wang G. X.; Wang P. L.; Ji J. H. Electron transfer driven highly valent silver for chronic wound treatment. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 5729–5736. 10.1039/C6TB01339B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalan L. R.; Pepin D. M.; Ul-Haq I.; Miller S. B.; Hay M. E.; Precht R. J. Targeting biofilms of multidrug-resistant bacteria with silver oxynitrate. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 49, 719–726. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason H. A.; Lovett J. M.; Spina C. J.; Stephenson C.; McBain A. J.; Hardman M. J. Silver oxysalts promote cutaneous wound healing independent of infection. Wound Repair Regen. 2018, 26, 144–152. 10.1111/wrr.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djokić S. S. Deposition of silver oxysalts and their antimicrobial properties. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, C359. 10.1149/1.1723498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Bahniuk M.; Hay M.; Imran M.; Spina C.; Unsworth L. Enhanced aqueous stability of silver oxynitrate through surface modification with alkanethiols. Colloids Surf., A 2018, 556, 210–217. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spina C. J.; Ladhani R.; Goodall C.; Hay M.; Precht R. Directed silica co-deposition by highly oxidized silver: Enhanced stability and versatility of silver oxynitrate. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5236. 10.3390/app9235236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jack J. C.; Kennedy T. The thermal analysis of ″argentic oxynitrate″ and silver oxides. J. Therm. Anal. 1971, 3, 25–33. 10.1007/BF01911767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masse R.; Simon A. An inorganic complex of silver (III): K5Ag(IO5OH)2 · 8H2O. J. Solid State Chem. 1982, 44, 201–207. 10.1016/0022-4596(82)90366-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mcmillan J. A. Higher oxidation states of silver. Chem. Rev. 1962, 62, 65–80. 10.1021/cr60215a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levason W.; Spicer M. D. The chemistry of copper and silver in their higher oxidation states. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1987, 76, 45–120. 10.1016/0010-8545(87)85002-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G. L.; Atkinson G. The chemistry of argentic oxide. The formation of a silver(III) complex with periodate in basic solution. Inorg. Chem. 1964, 3, 1741–1743. 10.1021/ic50022a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas M.; Khan Z. Kinetics of hydrolysis of diperiodatoargentate(III) ion and its reduction by paracetamol. Transition Met. Chem. 2006, 31, 516–521. 10.1007/s11243-006-0022-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balikungeri A.; Pelletier M.; Monnier D. Contribution to the study of the complexes bis(dihydrogen tellurato)cuprate(III) and argentate(III), bis(hydrogen periodato)cuprate(III) and argentate(III). Inorg. Chim. Acta 1977, 22, 7–14. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)90890-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna K. V.; Rao P. J. P. Kinetics and mechanism of oxidation of some reducing sugars by diperiodatoargentate(III) in alkaline medium. Transition Met. Chem. 1995, 20, 344–346. 10.1007/BF00139125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi T. S.; He J. T.; Ding T. H.; Wang A. Z. Studies of unusual oxidation states of transition metals III-kinetics and mechanism of oxidation of triethanolamine by diperiodatoargenate(III) ion in aqueous alkaline medium. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1991, 23, 815–823. 10.1002/kin.550230908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malode S. J.; Abbar J. C.; Nandibewoor S. T. Mechanistic aspects of uncatalyzed and ruthenium(III) catalyzed oxidation of DL-ornithine monohydrochloride by silver(III) periodate complex in aqueous alkaline medium. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2010, 363, 2430–2442. 10.1016/j.ica.2010.03.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dengel A. C.; Griffith W. P.; Mostafa S. I.; White A. J. P. Raman and infrared study of some metal periodato complexes. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 1993, 49, 1583–1589. 10.1016/0584-8539(93)80115-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevskiy A.; Jansen M. Synthesis, crystal structure determination, and physical properties of Ag5IO6. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2006, 632, 577–581. 10.1002/zaac.200500476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta H.; Ogawa T.; Uwatoko Y.; Araki K. N-confused tetraphenylporphyrin-silver(III) complex1. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 2676–2682. 10.1021/ic9901416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muckey M. A.; Szczepura L. F.; Ferrence G. M.; Lash T. D. Silver(III) carbaporphyrins: The first organometallic complexes of true carbaporphyrins. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 4840–4842. 10.1021/ic020285b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghi L.; Pelizzi G. The crystal and molecular structure of ethylenebis (biguanide) silver (III) sulphate hydrogen sulphate monohydrate [Ag (C6H16N10)] SO4HSO4. H2O. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1975, 31, 131–134. 10.1107/S0567740875002233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barefield E. K.; Mocella M. T. Complexes of silver(II) and silver(III) with macrocyclic tetraaza ligands. Inorg. Chem. 1973, 12, 2829–2832. 10.1021/ic50130a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An H.; Li Y.; Xiao D.; Wang E.; Sun C. Self-assembly of extended high-dimensional architectures from Anderson-type polyoxometalate clusters. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006, 6, 1107–1112. 10.1021/cg050326p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honda D.; Ikegami S.; Inoue T.; Ozeki T.; Yagasaki A. Protonation and methylation of an Anderson-type polyoxoanion [IMo 6O24]5. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 1464–1470. 10.1021/ic061881z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q.; Lin S. W.; Li Y. G.; Wang E. B. New supramolecular hybrids based on A-type Anderson polyoxometalates and Mn-Schiff-base complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2012, 382, 139–145. 10.1016/j.ica.2011.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honda D.; Ozeki T.; Yagasaki A. [(IMo7O26)2]6-: A missing link between molecular and solid oxides. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 6893–6895. 10.1021/ic0490425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; An H.; Liu X.; Wang H.; Chen Z.; Zhang H.; Hu Y. A host-guest hybrid framework with Anderson anions as template: Synthesis, crystal structure and photocatalytic properties. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2012, 21, 65–68. 10.1016/j.inoche.2012.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honda D.; Ozeki T.; Yagasaki A. Methoxide of an Anderson-type polyoxometalate and its conversion to a new type of species, [IMo9O32(OH)(OH2) 3]4. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 9616–9618. 10.1021/ic051351n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C. R.; Slater C.; Faulkner R. A.; Allan R. L. Self-assembly of an anion-binding cryptand for the selective encapsulation, sequestration, and precipitation of phosphate from aqueous systems. Am. Ethnol. 2018, 130, 13255–13259. 10.1002/ange.201805633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levason W. The coordination chemistry of periodate and tellurate ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1997, 161, 33–79. 10.1016/S0010-8545(97)90131-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouthamel C. E.; Hayes A. M.; Martin D. S. Ionization and hydration equilibria of periodic acid1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 82–87. 10.1021/ja01145a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouthamel C. E.; Meek H. V.; Martin D. S.; Banks C. V. Spectrophotometric studies of dilute aqueous periodate solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 3031–3035. 10.1021/ja01177a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert H.; Wieghardt G. Vibrational Spectra of Periodic Acid and Periodates, I. Z. Naturforsch., B: J. Chem. Sci. 1953, 27, 1299–1304. 10.1515/znb-1972-1103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valkai L.; Peintler G.; Horváth A. K. Clarifying the Equilibrium Speciation of Periodate Ions in Aqueous Medium. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 11417–11425. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina C. J.; Notarandrea-Alfonzo J.; Hay M.; Ladhani R.; Huszczynski S.; Khursigara C.; Precht R. Silver oxynitrate gel formulation for enhanced stability and antibiofilm efficacy. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 580, 119197. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy A. M.; Worku Z. A.; Kumar D.; Madi A. M. Pharmaceutical solvates, hydrates and amorphous forms: A special emphasis on cocrystals. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2017, 117, 25–46. 10.1016/j.addr.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.