Abstract

Introduction

Several risk factors for severe COVID-19 specific for patients with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) have been identified so far. Evidence regarding the influence of different RMD treatments on outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection is still poor.

Methods

Data from the German COVID-19-RMD registry collected between 30 March 2020 and 9 April 2021 were analysed. Ordinal outcome of COVID-19 severity was defined: (1) not hospitalised, (2) hospitalised/not invasively ventilated and (3) invasively ventilated/deceased. Independent associations between demographic and disease features and outcome of COVID-19 were estimated by multivariable ordinal logistic regression using proportional odds model.

Results

2274 patients were included. 83 (3.6%) patients died. Age, male sex, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, chronic lung diseases and chronic kidney disease were independently associated with worse outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Compared with rheumatoid arthritis, patients with psoriatic arthritis showed a better outcome. Disease activity and glucocorticoids were associated with worse outcome. Compared with methotrexate (MTX), TNF inhibitors (TNFi) showed a significant association with better outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR 0.6, 95% CI0.4 to 0.9). Immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and ciclosporin) (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.9), Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi) (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.7) and rituximab (OR 5.4, 95% CI 3.3 to 8.8) were independently associated with worse outcome.

Conclusion

General risk factors for severity of COVID-19 play a similar role in patients with RMDs as in the normal population. Influence of disease activity on COVID-19 outcome is of great importance as patients with high disease activity—even without glucocorticoids—have a worse outcome. Patients on TNFi show a better outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection than patients on MTX. Immunosuppressants, rituximab and JAKi are associated with more severe course.

Keywords: COVID-19, antirheumatic agents, glucocorticoids

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Also in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) age, male sex and specific comorbidities are general risk factors for severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

RMD disease activity and glucocorticoids are specific risk factors.

What does this study add?

RMD treatment is associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection severity.

While patients under TNFi treatment show better outcome, those under immunosuppressants, Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi) and rituximab show worse outcome.

How might this impact on clinical practice or further developments?

Patients with RMD under treatment with immunosuppressants, JAKi and rituximab need special guidance during the pandemic.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, increasing evidence about COVID-19 in inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) has been gained. In the general population, age, male sex and certain chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) have been identified as risk factors for severity of COVID-19.1 2 In patients with RMD, similar risk factors have been described. In addition, for those patients also RMD-specific risk factors play a role.3–6 Disease activity of the underlying RMD, for example, is of utmost importance for the outcome of COVID-19.4 6

Since immunomodulatory treatment can influence the outcome of infectious diseases significantly, the impact of the RMD treatment is also of great interest for patients with RMD suffering from SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the one hand, certain immunomodulatory drugs have been proven beneficial in the course of a SARS-CoV-2 infection7; on the other hand, immunomodulatory drugs can be detrimental.8 Moreover, timing and dosing of the treatment appears to be crucial. For example, dexamethasone is a standard treatment for severe COVID-197 at present, but a long-term glucocorticoid treatment due to RMD is associated with a worse outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection.4 6 The same might be true for Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi) treatment.9

The impact of TNFi on SARS-CoV-2 infection is not completely understood. Use of TNFi in comparison to ‘no disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD)’ was associated with a lower risk of hospitalisation in the first analysis of the data from the Global Rheumatology Alliance (GRA).3 However, it was not significantly associated with lower risk of mortality in a more recent analysis of the GRA in which MTX was used as reference category.4 Potential beneficial effects of TNFi have also been described in patients with COVID-19 with inflammatory bowel disease.10

Due to the lack of interventional studies in patients with RMDs and SARS-CoV-2 infection, the effects of RMD treatment have been evaluated in observational studies only. In this analysis from the German COVID19-RMD registry, we analysed the risk factors for the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with RMD, specifically focusing on the impact of RMD treatment.

Methods

Data source

The German COVID-19 registry for patients with RMDs was founded in March 2020 by the German Society for Rheumatology, together with the Justus-Liebig-University Giessen. Rheumatologists voluntarily entered the data into a web-based registry with implemented plausibility checks (https://www.covid19-rheuma.de; for more details, see Hasseli et al11).

SARS-CoV-2 infection outcome parameters

The primary outcome of interest was the mutually exclusive ordinal COVID-19 severity outcome:

(1) neither hospitalised, ventilated nor deceased; (2) hospitalised with or without non-invasive ventilation, but neither invasively ventilated nor deceased; and (3) invasively ventilated or deceased. At the time of analysis, all patients were required to have a resolved clinical course.

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics are shown descriptively, stratified by the three categories of the ordinal outcome. Independent associations between demographic and disease features and the ordinal COVID-19 outcome were estimated by multivariable ordinal logistic regression using the proportional odds model and were reported as OR and 95% CI. In the proportional odds model, an increase in severity is assumed to be equal across categories: the increase from ‘neither hospitalised, ventilated nor deceased’ to ‘hospitalised with or without non-invasive ventilation, but neither invasively ventilated nor deceased’ is treated in the same way as the increase from the latter category to ‘invasively ventilated or deceased’. Potential deviations from this assumption were assessed graphically and did not show relevant deviation (data not shown). Covariates included in the model were age, sex, key comorbidities (hypertension alone or CVD alone, hypertension combined with CVD, chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and diabetes), RMD or diagnostic group, rheumatic disease treatment prior to COVID-19 diagnosis (without glucocorticoids), as well as the combined status of disease activity as per the physician’s global assessment (severe/high or moderate disease activity vs minimal/low disease activity or remission), and the prednisolone-equivalent glucocorticoid use (1–10 mg/day and >10 mg/day). The combined status of disease activity and glucocorticoid use represents both their main effects and interaction (in an additive sense) and is analysed to disentangle the effects of both factors.

All patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were included in the main analyses. Patients with missing primary outcome (n=2) or missing values for age, sex and DMARDs (n=2) were excluded from analysis. Smoking status was missing in many cases. Therefore, we have not included smoking in the analysis. Missing values for glucocorticoid therapy and disease activity were derived by multiple imputation using full conditional specification.12 Results of the ordinal logistic regression analyses for 10 imputed data sets were pooled by Rubin’s rules.

For patients listed as having more than one RMD or being treated with more than one of the medications of interest, we created a hierarchy based on clinical expertise to categorise patients. We used the same hierarchy as in Strangfeld et al.4 This process produces disjoint categories, allowing a clear reference group for interpretation of the regression models and avoiding collinearities. Patients with more than one of the following diseases were grouped according to the following hierarchy: systemic lupus erythematosus >vasculitis>other CTD >rheumatoid arthritis (RA) >psoriatic arthritis (PsA)>(other) spondyloarthritis (SpA) >other non-inflammatory joint diseases (IJDs)/non-CTD rheumatic disease; where ‘X>Y’ means that disease X has priority over disease Y and an individual who has both disease X and disease Y is counted as patient with disease X. Similarly, patients receiving multiple csDMARDs or immunosuppressants (except glucocorticoids) were grouped according to the following hierarchy: immunosuppressants>sulfasalazine>antimalarials>leflunomide>methotrexate. Patients receiving a bDMARD/tsDMARD alone or in combination were considered solely in the bDMARD/tsDMARD group. Patients with an IJD other than RA, PsA or SpA (n=6); patients treated with more than one bDMARD/tsDMARD (n=1); and patients receiving interleukin-1 inhibitors (n=27) or belimumab (n=11) were excluded from analysis due to low numbers.

Regression coefficients were considered statistically significant for p values <0.05. All analyses were conducted in SAS V.9.4 or R V.4.0.4.

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in table 1. Of the 2274 patients included, 1771 (78%) did not require hospitalisation. Eighty-three patients died, resulting in a case fatality rate of 3.6%.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | Not hospitalised, no death | Hospitalised, no invasive ventilation or death | Invasive ventilation or death | Total |

| N | 1771 (77.9) | 374 (16.4) | 129 (5.7) | 2274 |

| General | ||||

| Age (years) | 55 (18) | 67 (19) | 71 (19) | 57 (19) |

| 66–75 | 226 (12.8) | 90 (24.1) | 38 (29.5) | 354 (15.6) |

| >75 | 137 (7.7) | 112 (29.9) | 47 (36.4) | 296 (13) |

| Male sex | 546 (30.8) | 130 (34.8) | 67 (51.9) | 743 (32.7) |

| Ever smoker | 115 (96.6) n=119 Missing=1652 |

21 (100) n=21 Missing=353 |

9 (100) n=9 Missing=120 |

145 (97.3) n=149 Missing=2125 |

| IJDs | ||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 781 (44.1) | 193 (51.6) | 76 (58.9) | 1050 (46.2) |

| Spondyloarthritis | 251 (14.2) | 28 (7.5) | 6 (4.7) | 285 (12.5) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 287 (16.2) | 19 (5.1) | 9 (7) | 315 (13.9) |

| JIA (poly, oligo, not systemic) | 6 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 6 (0.3) |

| All IJDs | 1313 (74.1) | 238 (63.6) | 90 (69.8) | 1641 (72.2) |

| CTDs/vasculitis | ||||

| SLE | 91 (5.1) | 12 (3.2) | 2 (1.6) | 105 (4.6) |

| CTDs (other than SLE) | 134 (7.6) | 29 (7.8) | 13 (10.1) | 176 (7.7) |

| Vasculitides | 145 (8.2) | 81 (21.7) | 29 (22.5) | 255 (11.2) |

| All CTD/vasculitides | 364 (20.6) | 121 (32.4) | 43 (33.3) | 528 (23.2) |

| Other RMDs | ||||

| Total | 151 (8.5) | 32 (8.6) | 11 (8.5) | 194 (8.5) |

| Disease activity | n=1751 Missing=20 |

n=355 Missing=19 |

n=109 Missing=20 |

n=2215 Missing=59 |

| Remission | 939 (53.6) | 165 (46.5) | 37 (33.9) | 1141 (51.5) |

| Minimal/low disease activity | 603 (34.4) | 112 (31.5) | 44 (40.4) | 759 (34.3) |

| Moderate disease activity | 169 (9.7) | 57 (16.1) | 12 (11) | 238 (10.7) |

| Severe/high disease activity | 40 (2.3) | 21 (5.9) | 16 (14.7) | 77 (3.5) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 524 (29.6) | 186 (49.7) | 83 (64.3) | 793 (34.9) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 121 (6.8) | 97 (25.9) | 51 (39.5) | 269 (11.8) |

| Chronic lung disease | 168 (9.5) | 72 (19.3) | 43 (33.3) | 283 (12.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 64 (3.6) | 71 (19) | 35 (27.1) | 170 (7.5) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30) | 355 (20) | 87 (23.3) | 31 (24) | 473 (20.8) |

| Diabetes | 137 (7.7) | 67 (17.9) | 31 (24) | 235 (10.3) |

| Cancer | 50 (2.8) | 25 (6.7) | 10 (7.8) | 85 (3.7) |

| Number of comorbidities | 0 (1) | 1.5 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) |

| No comorbidity | 896 (50.6) | 74 (19.8) | 15 (11.6) | 985 (43.3) |

| ≥3 comorbidities | 135 (7.6) | 94 (25.1) | 53 (41.1) | 282 (12.4) |

| DMARD therapies | ||||

| csDMARDs | 639 (36.1) | 125 (33.4) | 37 (28.7) | 801 (35.2) |

| Methotrexate (monotherapy) | 381 (21.5) | 84 (22.5) | 22 (17.1) | 487 (21.4) |

| Leflunomide | 76 (4.3) | 15 (4) | 9 (7) | 100 (4.4) |

| Sulfasalazine | 51 (2.9) | 12 (3.2) | 4 (3.1) | 67 (2.9) |

| Antimalarial | 131 (7.4) | 14 (3.7) | 2 (1.6) | 147 (6.5) |

| Immunosuppressants | 60 (3.4) | 36 (9.6) | 8 (6.2) | 104 (4.6) |

| bDMARDs | 653 (36.9) | 102 (27.3) | 41 (31.8) | 796 (35) |

| TNF inhibitors | 439 (24.8) | 43 (11.5) | 6 (4.7) | 488 (21.5) |

| Abatacept | 21 (1.2) | 8 (2.1) | 1 (0.8) | 30 (1.3) |

| B cell-targeted bDMARDs | 46 (2.6) | 29 (7.8) | 27 (20.9) | 102 (4.5) |

| Rituximab | 37 (2.1) | 28 (7.5) | 26 (20.2) | 91 (4) |

| Belimumab | 9 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.8) | 11 (0.5) |

| IL-6 inhibitors | 47 (2.7) | 9 (2.4) | 3 (2.3) | 59 (2.6) |

| IL-1 inhibitors | 21 (1.2) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (2.3) | 27 (1.2) |

| IL-17, IL-23, IL-12/23 inhibitors | 79 (4.5) | 10 (2.7) | 1 (0.8) | 90 (4) |

| tsDMARDs | 108 (6.1) | 33 (8.8) | 14 (10.9) | 155 (6.8) |

| JAK inhibitors | 101 (5.7) | 32 (8.6) | 14 (10.9) | 147 (6.5) |

| Apremilast | 7 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 8 (0.4) |

| No DMARD therapies | 311 (17.6) | 79 (21.1) | 29 (22.5) | 419 (18.4) |

| Further therapies | ||||

| Glucocorticoids (#) | 485 (27.5) n=1759 Missing=12 |

198 (52.9) n=373 Missing=1 |

78 (60.5) n=129 Missing=0 |

761 (33.6) n=2261 Missing=13 |

|

0 mg/day<glucocorticoids ≤10 mg/day |

453 (25.8) | 179 (48) | 60 (46.5) | 692 (30.6) |

| Glucocorticoids>10 mg/day | 24 (1.4) | 18 (4.8) | 18 (14) | 60 (2.7) |

| NSAIDs | 395 (22.9) (n=1736 Missing=47 |

59 (16.3) (n=120 Missing=2 |

12 (9.9) n=83 Missing=0 |

466 (21.1) n=2208 Missing=66 |

Data are N (column %) for categorical variables or mean (SD) for continuous variables. Table includes all patients with a non-missing outcome and non-missing values for age, sex and DMARDs (four patients excluded). Data refer to patients with non-missing values for the respective variable; total N for patients with non-missing values is given in parentheses for variables with missing values; the total number of missing values is also given in parentheses, for the applicable variables. # denotes patients with a missing glucocorticoid dosage. For csDMARD therapies and immunosuppressants, only patients not simultaneously receiving a bDMARD/tsDMARD are included. For csDMARDs, patients are included who correspond to the specific therapy when applying the hierarchy described in the Methods section.

bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; BMI, body mass index; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; CTD, connective tissue disease; DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; IJD, inflammatory joint disease; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; N, number; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; RMDs, rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

The mean age of all patients was 57 years; 67% were female. The most common RMD was RA with 46%, followed by PsA (14%), SpA (13%) and vasculitides (11%).

Eighty-six per cent of patients had a PCR-confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection; 8% had only an antibody-confirmed diagnosis; the remaining patients had an unknown/other type of diagnosis (two patients were diagnosed based on symptoms only). For all patients, the outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection was known.

RMD treatments

At the time of SARS-CoV-2 infection, 18% did not receive any DMARD treatment (see table 1). Immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and ciclosporin) were used in 5%, csDMARDs in 35%, bDMARDs in 35% and tsDMARDs in 7%. Methotrexate was the most common csDMARD, and TNFi was the most common bDMARD. Rituximab was used in 91 patients (4%), and JAKi was used in 147 patients (6.5%).

SARS-CoV-2 infection outcome analysis

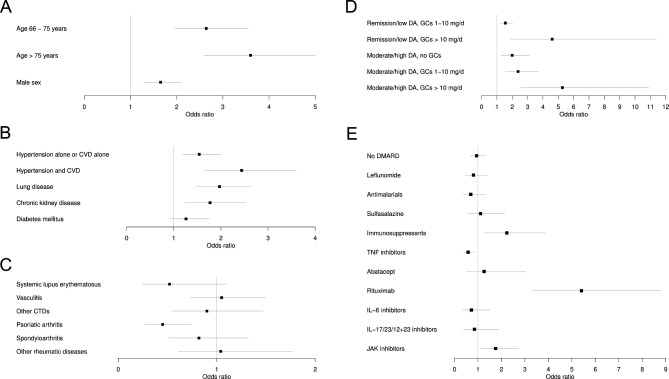

Age above 65 years was associated with higher COVID-19 severity with an OR of 2.6 (95% CI 2.0 to 3.6) and above 75 years with an OR of 3.6 (95% CI 3.0 to 5.0) (table 2 and figure 1A). Male sex was also associated with greater severity (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.1).

Table 2.

Results of the multivariable ordinal logistic regression using the proportional odds model

| Ordinal regression (proportional odds model) | OR | 95% CI |

| General | ||

| Age ≤65 years | 1.0 | Reference |

| 65 years<age≤75 | 2.6 | 2.0 to 3.6 |

| Age >75 | 3.6 | 3.0 to 5.0 |

| Male sex (vs female) | 1.7 | 1.3 to 2.1 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension alone or CVD alone | 1.5 | 1.2 to 2.0 |

| Hypertension and CVD | 2.4 | 1.7 to 3.6 |

| Chronic lung disease | 2.0 | 1.5 to 2.6 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.8 | 1.2 to 2.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.3 | 0.9 to 1.8 |

| Rheumatic disease | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.0 | Reference |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 0.5 | 0.2 to 1.1 |

| Vasculitides | 1.1 | 0.7 to 1.5 |

| Other connective tissue diseases | 0.9 | 0.6 to 1.5 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 0.5 | 0.3 to 0.7 |

| Spondyloarthritides | 0.8 | 0.5 to 1.3 |

| Other rheumatic diseases (not IJDs/CTDs/vasculitis) | 1.0 | 0.6 to 1.8 |

| Medication* | ||

| Methotrexate (monotherapy) | 1.0 | Reference |

| No DMARD therapy | 0.9 | 0.7 to 1.4 |

| Leflunomide | 0.8 | 0.5 to 1.4 |

| Antimalarials | 0.7 | 0.4 to 1.3 |

| Sulfasalazine | 1.1 | 0.6 to 2.1 |

| Immunosuppressants | 2.2 | 1.3 to 3.9 |

| TNF inhibitors | 0.6 | 0.4 to 0.9 |

| Abatacept | 1.3 | 0.5 to 3.0 |

| Rituximab | 5.4 | 3.3 to 8.8 |

| IL-6 inhibitors | 0.7 | 0.3 to 1.5 |

| IL-17/IL-23/IL-12+23 inhibitors | 0.9 | 0.4 to 1.9 |

| JAK inhibitors | 1.8 | 1.1 to 2.7 |

| Disease activity and glucocorticoids | ||

| Remission/low DA, no GCs | 1.0 | (Reference) |

| Remission/low DA, GCs 1–10 mg/day | 1.6 | 1.2 to 2.0 |

| Remission/low DA, GCs>10 mg/day | 4.6 | 1.9 to 11.4 |

| Moderate/high DA, no GCs | 2.0 | 1.3 to 3.1 |

| Moderate/high DA, GCs 1–10 mg/day | 2.4 | 1.5 to 3.7 |

| Moderate/high DA, GCs >10 mg/day | 5.3 | 2.5 to 10.9 |

Ordinal outcome of COVID-19 severity was defined as (1) not-hospitalised, (2) hospitalised but not invasively ventilated and (3) invasively ventilated/deceased.

Missing values imputed via multiple imputation. Effects significant at level α=0.05 are marked in bold. N=2222. Compared with table 1, the following numbers of patients were excluded: 27 patients receiving IL-1 inhibitors, 11 patients receiving belimumab, 8 patients receiving apremilast, 6 patients with non-systemic JIA, 1 patient receiving multiple bDMARDs/tsDMARDs.

*Patients receiving multiple csDMARDs or immunosuppressants (except glucocorticoids) were grouped according to the following hierarchy: immunosuppressants>sulfasalazine>antimalarials>leflunomide>methotrexate. Patients receiving a bDMARD/tsDMARD alone or in combination were considered solely in the bDMARD/tsDMARD group.

bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; CTD, connective tissue disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DA, disease activity; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GC, glucocorticoid; IJD, inflammatory joint disease; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Figure 1.

(A–E) Results of the multivariable ordinal logistic regression using the proportional odds model and reported as OR and 95% CI for each regressor variable. Associations with SARS-CoV-2 infection severity are shown with (A) general factors, (B) comorbidities, (C) RMD diagnosis, (D) RMD disease activity and glucocorticoids, (E) RMD treatment (immunosuppressants: mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and ciclosporin). The reference categories are as follows: (A) ≤65 years, ≤65 years, female sex; (B) the non-presence of the specific comorbidity; (C) rheumatoid arthritis; (D) remission/low disease activity, no glucocorticoids; and (E) methotrexate monotherapy. Missing values were imputed via multiple imputation. N=2222. Compared with table 1, the following numbers of patients were excluded: 27 patients receiving IL-1 inhibitors, 11 patients receiving belimumab, 8 patients receiving apremilast, 6 patients with non-systemic JIA, one patient receiving multiple bMARDs/tsDMARDs. bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CTD, connective tissue diseases; DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; DA, disease activity; GC, Glucocorticoids; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs.

Arterial hypertension, CVD, chronic lung disease (including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and interstitial lung diseases), and CKD showed significant associations with COVID-19 severity (table 2 and figure 1B). The strongest association was found for patients having both comorbidities, arterial hypertension and CVD (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.7 to 3.6).

With respect to the underlying RMD entity, PsA was associated with less severe COVID-19 course in comparison to RA (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.74) (table 2 and figure 1C).

Since disease activity and the use of glucocorticoids are usually linked, both factors were analysed jointly. The results are shown in table 2 and figure 1D. Remission/low disease activity with low dose GCs (1–10 mg/d) showed a significant association with worse outcome (OR 1.6, 95% CI: 1.2 to 2.0) compared with remission/low disease activity without GCs. This effect increased with higher GC doses (OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.9 to 11.4). Moderate/high disease activity but no GCs were also associated with a worse outcome compared with remission/low disease activity with no GCs (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.28 to 3.11). Moderate/high disease activity with low-dose GC were associated with a worse COVID-19 outcome with an OR of 2.4 (95% CI 1.5 to 3.7), and in case of moderate/high disease activity with high-dose GC, this was even more prominent with an OR of 5.3 (95% CI 2.53 to 10.9).

For the analysis of the impact of RMD treatment on the outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection, MTX monotherapy was used as reference (table 2 and figure 1E). Treatment with immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and ciclosporin) was associated with a higher COVID-19 severity (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.9). JAKis were also associated with a significantly worse severity (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.7). The strongest association with worse outcome of COVID-19 was found for rituximab with an OR of 5.4 (95% CI 3.3 to 8.8). In contrast, TNFi showed a significant association with a better outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection with an OR of 0.6 (95% CI 0.4 to 0.9).

Discussion

This analysis adds evidence that medication for RMD has a considerable impact on the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Two main results could be retrieved from this analysis: (1) TNFi is not associated with a more severe course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with RMD and, (2) in contrast, immunosuppressants, JAKis and rituximab are associated with a more severe course. Moreover, it could be confirmed that general risk factors like age, male sex and certain chronic conditions are also associated with greater severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with underlying RMD.1 2

RMD-specific risk factors have been described. The impact of disease activity and GC use are of utmost importance. Disease activity and the use of GC are usually linked. Analysing these effects separately from each other is very difficult because of the known confounding by indication in the setting of observational data. In a correspondence to the COVID-19 mortality analysis of the GRA data set,4 this interaction was shown.13 Here, we present similar results. However, in this analysis, GC use was associated with worse outcome even in patients in remission or low disease activity.

In this analysis, PsA was associated with a better COVID-19 course compared with RA. In the COVID-19 mortality analysis, PsA was not significantly associated but also showed an OR of less than 1.0 (0.75, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.07). Whether the positive association seen in our analysis is due to true differences between the diseases or unmeasured confounders is not clear. However, the risk of severe infection in bDMARD-treated patients with psoriasis compared with patients with RA is much lower, which might be a signal of different susceptibility for severe infections.14

A very important finding of our analysis is the potential beneficial effect of TNFi. This association was not seen in an earlier mortality analysis, although TNFi showed also an OR of less than 1.0 (0.9; 95% CI: 0.5 to 1.4).4 This discrepancy might be due to the large heterogeneity in the GRA data set with large differences between the countries regarding the outcomes. In the analysis by Sparks et al. TNFi were used as reference medication and therefore, due to methodological reasons, the impact of TNFi could not be estimated in this study.5 There are also clinical trials using TNFi in different settings of COVID-19.15

In the GRA analysis concerning the risk of mortality, sulfasalazine was significantly associated with mortality.4 In our analysis, sulfasalazine was not associated with COVID-19 severity, which may be due to more homogenous data with regard to healthcare system-related factors.

Regarding the influence of rituximab, there is growing evidence for an association with a worse outcome. This has been shown in various settings in RMDs.4 5 16–18 In our analysis, we confirmed these results. The influence of B-cell depletion/anti-CD20 antibodies like rituximab on COVID-19 outcome has also been studied in other diseases in which these treatments are used.19 20 For example, observational studies from multiple sclerosis showed a similar association of rituximab with severe COVID-19 outcome as in RMD.21

Data addressing an influence of JAKis on COVID-19 outcome are still limited. Thus, our analysis adds important knowledge showing an association of JAKi as RMD treatment with a more severe course of COVID-19. A negative association with COVID-19 outcome was also seen in the RA analysis of the GRA data set.5 In an analysis from Sweden, an increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalisation as well as COVID-19-related death has been described for patients under therapy with JAKis.16 In contrast, owing to their anti-inflammatory potential, JAKis have been approved for the short-term treatment of severe COVID-19.9 22 Here, the timing and duration of the treatment seems to play a role, with negative impact in patients with RMD pretreated with JAKis and potential benefits when initiated to treat severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. A pathophysiological explanation could be that type I interferon response is crucial in the initial phase of infection for a good outcome of SARS-CoV2 infection.23 Therefore, inhibition of the type I interferon pathway by JAKi in the early phase of infection might contribute to more severe COVID-19.

The strengths of this analysis in comparison to the GRA data lie in the fact that our data are more homogenous as they were collected in a single country within one healthcare system and similar treatments and chances of care for all included patients.

However, there also are study limitations. Missing data on known confounders like RMD disease duration and number of RMD pretreatments limit the interpretation. Especially for rituximab and JAKi, it is known that they are often used in non-responder to MTX/TNFi.24 25 Therefore, the negative impact of those therapies on COVID-19 severity needs to be interpreted carefully. Similarly, we do not have detailed data on RTX dosage and—even more important—time of last infusion to be able to calculate the number of days between RTX treatment and date of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Furthermore, we do not know if the RMD treatment was paused due to acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although most patients continue their RMD treatment in the pandemic as stated in the treatment recommendations, in the case of an acute symptomatic infection especially in hospitalised patients, it is recommended to pause the immunomodulating treatment.26–28 Differential effects of the RMD treatment might therefore also be explained by different half-lives of these drugs.

In conclusion, risk factors for higher severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection known for the general population, such as age, male sex and certain chronic conditions, play a similar role in patients with RMDs. In addition, further risk factors need to be taken into account, for example, the influence of higher disease activity with an increased risk of worse outcome even without using GCs on the one hand and association of chronically administered GCs with a similar worse outcome on the other. Regarding RMD medication, our data show that treatment with TNFi was associated with better outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection than MTX. Moreover, treatment with immunosuppressants, JAKi and rituximab was associated with worse outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection. These associations may be attributed to residual and unmeasured confounding due to higher burden of comorbidity or cumulative effect of therapies. Taken together, while it is crucial to control RMD disease activity, the medication used to achieve this control needs to be carefully chosen.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all physicians and personnel involved in the documentation of the cases in our registry: Dr Fredrik Albach, Dr Annette Alberding, Dr Tobias Alexander, Professor Dr Rieke Alten, Dr Susanne Amann, Dr Christopher Amberger, Dr Michaela Amberger, Dr Bianka Andermann, Nils Anders, Ioana Andreica, Dr Jan Andresen, Dr Nikolaos Andriopoulos, Dr Peer Aries, Professor Dr Martin Aringer, Dr Uta Arndt, Sarah Avemarg, Professor Dr Marina Backhaus, Professor Dr Christoph Baerwald, Dr Erich Bärlin, Dr Nora Bartholomä., Dr Hans Bastian, Dr Michael Bäuerle, Dr Jutta Bauhammer, Dr Christine Baumann, Professor Dr Heidemarie Becker, Dr Klaus Becker, Dr Michaela Bellm, Dr Sylvia Berger, Dr Gerhard Birkner, Professor Dr Norbert Blank, Daniel Blendea, Dr Hans Bloching, Dr Stephanie Böddeker, Dr Susanne Bogner, Dr Martin Bohl-Bühler, Sebastian Böltz, Dr Ilka Bösenberg, Nicole Böttcher, PD Dr Jan Brandt-Jürgens, Dr Matthias Braun, Dr Matthias Braunisch, Dr Jan Phillip Bremer, Dr Matthias Broll, Dr Andreas Bruckner, Dr Veronika Brumberger, Dr. Martin Brzank, Dr. Sahra Büllesfeld, Sandra Burger, Dr Gamal Chehab, Dr Michaela Christenn, Dr Anne Claußnitzer, Professor Dr Kirsten de Groot, Dr Elvira Decker, Dr Frank Demtröder, Dr Jacqueline Detert, Dr Rainer Dörfler, Dr Ines Dornacher, Dr Elke Drexler, Dr Edmund Edelmann, Dr Roman Eder, Dr Christina Eisterhues, Dr Andreas Engel, Dr Joachim Michael Engel, Dr Brigitte Erbslöh-Möller, Dr Miriam Feine, PD Dr Martin Feuchtenberger, Professor Dr Dr Christoph Fiehn, PD Dr Rebecca Fischer-Betz, Professor Dr Martin Fleck, Dr Stefanie Freudenberg, Dr Christian Fräbel, Dr Petra Fuchs, Dr Regina Gaissmaier, Dr Ino Gao, Oliver Gardt, Dr Georg Gauler, Dr Katrin Geißler, Dr Joachim Georgi, Dr Jasmin Gilly, Yannik Gkanatsas, Dr Cornelia Glaser, Agnes Gniezinski-Schwister, Dr Rahel Gold, Dr Norman Görl, Dr Karl-Heinz Göttl, Dr Beate Göttle, Dr Anett Gräßler, Dr Ricardo Grieshaber-Bouyer, Dr Gisela Grothues, Dr Mathias Grünke, Dr Elizabeth Guilhon de Araujo, Dr Florian Günther, Mirjam Haag, Dr Linda Haas, Dr Anna Haas-Wöhrle, Dr Denitsa Hadjiski, PD Dr Hildrun Haibel, Till Ole Hallmann-Böhm, Dr Urs Hartmann, Dr Charlotte S. Hasenkamp, Dr Maura-Maria Hauf, Dr Matthias Hauser, Dr Nicole Heel, Dr Liane Hein, Dr Reinhard Hein, Dr Claudia Hendrix, Professor Dr Jörg Henes, Dr Karen Herlyn, Dr Walter Hermann, Professor Dr Peter Herzer, Dr Andrea Himsel, Dr Guido Hoese, PD Dr Paula Hoff, Marie-Therese Holzer, Dr Johannes Hornig, Melanie Huber, Dr Georg Hübner, Dr Georg Hübner, Ole Hudowenz, PD Dr Axel Hueber, Dr Verena Hupertz, Dr Elke Iburg, Dr Annette Igney-Oertel, Dr Steffen Illies, PD Dr Annett M. Jacobi, Ilona Jandova, Dipl.-Med. Christiane Jänicke, Dr Sebastian T. Jendrek, Dr Anne Johannes, Dr Aaron Juche, Dr Sarah Kahl, Dr Ludwig Kalthoff, Dr Wiebke Kaluza-Schilling, Dr Eleni Kampylafka, Dr Antje Kangowski, Dr Andreas Kapelle, Dr Kirsten Karberg, Dr Dorothee Kaudewitz, Dr Bernd Oliver Kaufmann, Professor Dr Gernot Keyßer, Dr Nayereh Khoshraftar-Yazdi, Dr Matthias Kirchgässner, Dr Matthias Kirrstetter, Dr Birgit Kittel, Dr Christoph Kittel, Julia Kittler, Dr Arnd Kleyer, Dr Claudia Klink, Dr Barbara Knau, Professor Dr Christian Kneitz, Anna Knothe, Dr Katrin Köchel, Dr Benjamin Köhler, Dr Peter Korsten, Dr Magdolna Kovacs, Dr Dietmar Krause, Dipl.-Med. Gabi Kreher, Dr Rene Kreutzberger, Dr Eveline Krieger-Dippel, Professor Dr Klaus Krüger, Dr Brigitte Krummel-Lorenz, Dr Martin Krusche, Dr Holger Kudela, Dr Christoph Kuhn, Dr Kerstin Kujath, Dr Reiner Kurthen, Dr Rolf Kurzeja, Peter Kvacskay, Professor Dr Peter Lamprecht, Sabine Langen, Dr Heiko Lantzsch, Dr Petra Lehmann, Dr Nicolai Leuchten, PD Dr Christian Löffler, Dr Dorothea Longerich-Scheuß, Dr Gitta Lüdemann, Dr Thomas Lutz, Vanessa Maerz, Dr Hartmut Mahrhofer, Dr Ingeborg Maier, Professor Dr Karin Manger, Professor Dr Elisabeth Märker-Hermann, Dr Anette Märtz, Dr Anette Märtz, Hanin Matar, Dr Johannes Mattar, Dr Sebastian Maus, Dr Ursula Mauß-Etzler, Dr Regina Max, Dr Florian Meier, Dr Adelheid Melzer, Carlos Meneses, Dr Hans-Jürgen Menne, Dr Helga Merwald-Fraenk, Dr Claudia Metzler, Dr Sabine Mewes, Dr Harriet Morf, Dr Harald Mörtlbauer, Dr Markus Mortsch, Dr Burkhard Muche, PD Dr Niels Murawski, Dr Antoine Murray, Dr Jana Naumann, Dr Anabell Nerenheim, Dr Joachim Neuwirth, Phuong Nguyen, Dr Stine Niehus, Dr Martin Nielsen, Dr Matthias Noehte, Dr Dirk Nottarp, Dr Dieter Nüvemann, Dr Wolfgang Ochs, Dr Sarah Ohrndorf, Dr Jürgen Olk, Dr Silke Osiek, Dr Filiz Özden, Dr Bettina Panzer, Dr Alina Patroi, Dr Ulrich Pfeiffer, Dr Dorothea Pick, Dr Marta Piechalska, Dr Matthias Pierer, I. Pohlenz, Dr Mikhail Protopopov, Dr Almut Pulla, Dr Michael Purschke, Dr Judith Rademacher, Dr Wolf Raub, PD Dr Jürgen Rech, Dr Sabine Reckert, Dr Sabine Reckert, Dr Anke Reichelt de Tenorio, Dr Christiane Reindl, Dr Annja Reisch, Professor Dr Gabriela Riemekasten, PD Dr Markus Rihl, Dr Viale Rissom, Dr Karin Rockwitz, Dr Maike Rösel, Dr Markus Röser, Dr Christoph Rossmanith, PD Dr Ekkehard Röther, Dr Fabian Röther, Dr Maria Roth-Szadorski, Professor Dr Martin Rudwaleit, Dr Petra Saar, Jasemine Saech, Dr Oliver Sander, Dr Eva Sandrock, Dr Ertan Saracbasi-Zender, Dr Michael Sarholz, Dr Christoph Schäfer, Dr Kerstin Schäfer, Dr Martin Scheel, Dr Stefan Schewe, Dr Hermine Schibinger, Magnus Schiebel, Dr Andreas Schieweck-Güsmer, Dr Susanne Schinke, Dr Ulrike Schlenker, Dr Daniel Schlittenhardt, PD Dr Marc Schmalzing, Dr Verena Schmitt, Dr Matthias Schmitt-Haendle, Dr Sebastian Schnarr, Dr Dieter Schöffel, Dr Michaela Scholz, Dr Jutta Schönherr, Dr Ulrich Schoo, Dr Judith Schreiber, Anna-Sophie Schübler, Dr Florian Schuch, Dr Ilka Schwarze, Dr Carola Schwerdt, Dr Eva Seipelt, Dr Matthias Sekura, Dr Jörg Sensse, Dr Nyamsuren Sentis, Dr Christine Seyfert, Ondrej Sglunda, Dr Naheed Sheikh, Dr Iris Sievert, Dr David Simon, Marta Sluszniak, Dr Katharina Sokoll, Dr Sigrid Sonn, Dr Susanna Späthling-Mestekemper, Dr Lydia Spengler, Gerald Stapfer, Dr Nicolai Steinchen, Dr Mirko Steinmüller, Karen Steveling, Dr Karin Stockdreher, Dr Helga Streibl, Professor Dr Johannes Strunk, Dr Mechthild Surmann, Dr Ingo H. Tarner, Dr Stefanie Tatsis, Dr Astrid Thiele, Dr Jan Thoden, Dr Anika Tuleweit, Professor Dr Peter Vaith, Dr Inka Vallbracht-Ackermann, Dr Susanne Veerhoff, Dr Susanne Veerhoff, Professor Dr Nils Venhoff, Dr Anita Viardot, Lisa Vinnemeier-Laubenthal, Dr Markus Voglau, Dr Marcus von Deimling, Dr Cay-Benedict von der Decken, Dr Heike von Löwis, Dr Marisa Walther, Dr Sven Weidner, Dr Martin Weigelt, Professor Dr Stefan Weiner, Dr Jutta Weinerth, Dr Angela Weiß, Dr Martin Welcker, Dr Stephanie Werner, Dr Dirk Wernicke, Dr Franziska Wiesent, Professor Dr Peter Willeke, Dr Lea Winau, Dr Hans Wisseler, Dr Matthias Witt, Dr Stefan Wolf, Dr Nina Wysocki, Dr Panagiota Xanthouli, Dr Monika Zaus, Dr Markus Zeisbrich, Dr Silke Zinke

Footnotes

Twitter: @rheuma_doktorin, @ChSpecker

ACR and RH contributed equally.

Contributors: ACR, RH, MS and UM-L had access to the study data, developed the figures and tables, and vouched for the data and analyses. MS performed the statistical analyses and contributed to data quality control, data analysis and data interpretation. ACR, RH, BFH, AK, HM-L, AP, JR, TS, AS, HS-K, REV, CS and UM-L contributed to data collection, data quality control, data analysis and data interpretation. All authors contributed to the intellectual content during the drafting and revision of the work and approved the final version to be published. ACR and RH act as guarantors.

Funding: The registry is funded, in part, by the German Society for Rheumatology. RH is funded, in part, by a JLU Career grant of the Justus-Liebig-University Giessen, Germany.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Applications to access the data should be made to the COVID-19 steering committee of the German Society for Rheumatology.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Justus-Liebig-University Giessen (#52–50) and is registered at EuDRACT (2020-001958-21#). For the present analysis, we included data from 30 March 2020 to 9 April 2021.

References

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020;323:1239–42. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1985. 10.1136/bmj.m1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S, et al. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:859–66. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strangfeld A, Schäfer M, Gianfrancesco MA, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death in people with rheumatic diseases: results from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:930–42. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparks JA, Wallace ZS, Seet AM, et al. Associations of baseline use of biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs with COVID-19 severity in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance physician registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1137–46. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasseli R, Mueller-Ladner U, Hoyer BF, et al. Older age, comorbidity, glucocorticoid use and disease activity are risk factors for COVID-19 hospitalisation in patients with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. RMD Open 2021;7:e001464. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021;384:693–704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh B, Ryan H, Kredo T, et al. Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;2:CD013587. 10.1002/14651858.CD013587.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al. Baricitinib plus Remdesivir for hospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021;384:795–807. 10.1056/NEJMoa2031994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ungaro RC, Brenner EJ, Gearry RB, et al. Effect of IBD medications on COVID-19 outcomes: results from an international registry. Gut 2021;70:725–32. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasseli R, Mueller-Ladner U, Schmeiser T, et al. National Registry for patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases (IRD) infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Germany (recovery): a valuable mean to gain rapid and reliable knowledge of the clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infections in patients with IRD. RMD Open 2020;6:e001332. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 2007;16:219–42. 10.1177/0962280206074463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schäfer M, Strangfeld A, Hyrich KL, et al. Response to: 'Correspondence on 'Factors associated with COVID-19-related death in people with rheumatic diseases: results from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician reported registry'' by Mulhearn et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2021. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220134. [Epub ahead of print: 01 Mar 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García-Doval I, Hernández MV, Vanaclocha F, et al. Should tumour necrosis factor antagonist safety information be applied from patients with rheumatoid arthritis to psoriasis? Rates of serious adverse events in the prospective rheumatoid arthritis BIOBADASER and psoriasis BIOBADADERM cohorts. Br J Dermatol 2017;176:643–9. 10.1111/bjd.14776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson PC, Liew DFL, Liew JW, et al. The potential for repurposing anti-TNF as a therapy for the treatment of COVID-19. Med 2020;1:90–102. 10.1016/j.medj.2020.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bower H, Frisell T, Di Giuseppe D, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on morbidity and mortality in patients with inflammatory joint diseases and in the general population: a nationwide Swedish cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2021. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-219845. [Epub ahead of print: 23 Feb 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avouac J, Drumez E, Hachulla E, et al. COVID-19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases treated with rituximab: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2021;3:e419–26. 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00059-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felten R, Duret PM, Bauer E, et al. OP0282 Rituximab associated with severe COVID-19 among patients with inflammatory arthritides: a 1-year multicenter study in 1116 succesive patients receiving biologic agents. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:170–1. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakubíková M, Týblová M, Tesař A, et al. Predictive factors for a severe course of COVID-19 infection in myasthenia gravis patients with an overall impact on myasthenic outcome status and survival. Eur J Neurol 2021;28:3418–25. 10.1111/ene.14951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duléry R, Lamure S, Delord M, et al. Prolonged in-hospital stay and higher mortality after Covid-19 among patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with B-cell depleting immunotherapy. Am J Hematol 2021;96:934–44. 10.1002/ajh.26209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson-Yap S, De Brouwer E, Kalincik T, et al. Associations of disease-modifying therapies with COVID-19 severity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2021. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012753. [Epub ahead of print: 05 Oct 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guimarães PO, Quirk D, Furtado RH, et al. Tofacitinib in patients hospitalized with Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2021;385:406–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa2101643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Q, Bastard P, Liu Z, et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 2020;370:eabd4570. 10.1126/science.abd4570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Listing J, Kekow J, Manger B, et al. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of disease activity, treatment with glucocorticoids, TNFα inhibitors and rituximab. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:415–21. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finckh A, Tellenbach C, Herzog L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antitumour necrosis factor agents, biologics with an alternative mode of action and tofacitinib in an observational cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Switzerland. RMD Open 2020;6:e001174. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasseli R, Müller-Ladner U, Keil F, et al. The influence of the SARS-CoV-2 lockdown on patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases on their adherence to immunomodulatory medication - a cross sectional study over 3 months in Germany. Rheumatology 2021. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab230. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Mar 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hausmann JS, Kennedy K, Simard JF, et al. Immediate effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient health, health-care use, and behaviours: results from an international survey of people with rheumatic diseases. Lancet Rheumatol 2021;3:e707–14. 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00175-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulze-Koops H, Krüger K, Hoyer BF, et al. Updated recommendations of the German Society for rheumatology for the care of patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases in times of SARS-CoV-2-methodology, key messages and justifying information. Rheumatology 2021;60:2128–33. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Applications to access the data should be made to the COVID-19 steering committee of the German Society for Rheumatology.