Abstract

Objectives

There are numerous reports on the psychological burden of medical workers after the COVID-19 outbreak; however, no study has examined the influence of developmental characteristics on the mental health of medical workers. The objective of this study was to examine whether the developmental characteristics of medical workers are associated with anxiety and depression after the COVID-19 outbreak.

Design

We conducted an online cross-sectional questionnaire survey in October 2020.

Participants and setting

The data of 640 medical workers were analysed. The questionnaire included items on sociodemographic data, changes in their life after the COVID-19 outbreak and symptoms of depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) traits and autism spectrum disorder traits.

Main outcomes

Depression symptoms were assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and anxiety symptoms were assessed by the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7. A series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed to test the effects of developmental characteristics on depression and anxiety symptoms after controlling for sociodemographic factors and changes in participants’ lives after the COVID-19 outbreak.

Results

Increases in physical and psychological burden were observed in 49.1% and 78.3% of the subjects, respectively. The results of a multiple regression analysis showed that ADHD traits were significantly associated with both depression (β=0.390, p<0.001) and anxiety (β=0.426, p<0.001). Autistic traits were significantly associated with depression (β=0.069, p<0.05) but not anxiety. Increased physical and psychological burden, being female, medical workers other than physicians and nurses, fear of COVID-19 and experience of discrimination were also significantly associated with both depression and anxiety.

Conclusion

Globally, the burden on medical workers increased. This study suggested that medical workers with higher ADHD traits may need special attention during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: mental health, public health, COVID-19

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First study to examine the association between developmental characteristics and psychological burden of medical workers under the COVID-19 outbreak.

Sufficiently large sample size.

Broad assessment on occupational environment and the changes in daily lifestyle under the COVID-19 outbreak.

Despite an attempt to obtain a diverse sample of medical workers, the sample was skewed towards certain professions.

Developmental characteristics in this study were not formal diagnoses.

Introduction

Previous studies have shown that outbreaks of serious infectious diseases can place a heavy psychological burden on healthcare workers.1–5 Immediately after the COVID-19 outbreak, it was pointed out that mental health problems can emerge among medical workers due to the fear of risking infection to their own family, friends and colleagues, with uncertainty about the future and stigmatisation of themselves.6 There have already been a number of studies reporting mental health problems among healthcare workers working against COVID-19.1–4 7–29 However, these reports were mainly from regions such as China, the USA and European countries that experienced severe consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

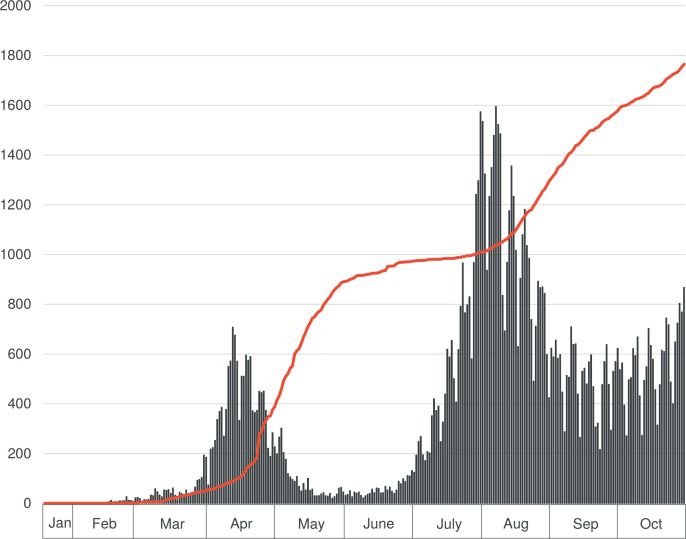

Compared with the above-mentioned countries, the number of new cases and deaths caused by COVID-19 in Japan was small (figure 1)30; hence, people experiencing loss through death were considered rare. Although there has been no government-imposed lockdown with legal restraints, the further spread of COVID-19 has been prevented by only a request for self-restraint in social activities by the prime minister and prefectural governors.31 People’s compliance with the request of wearing masks and avoiding unnecessary outings might have contributed to preventing the spread of the disease, but their effectiveness are not clear. In contrast, medical institutes, along with restaurants/bars and music events, were reported to have contributed to cluster outbreaks,32 leading to increased stigma and discrimination against healthcare workers. Thus, it is not only the fear of infection by the SARS-CoV-2, but also the increased workload related to infection control, stigma/discrimination and stress in healthcare workers. When healthcare workers experience physical or mental health problems, it could lead to a decline in healthcare services and ultimately affect patients.33 As maintaining the quality of healthcare services affects the interests of society as a whole, reducing the physical and mental burden of healthcare providers would be the most essential factor to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1.

Epidemic curve of COVID-19 in Japan until October 2020. The bar graph shows the epidemic curve displaying the number of patients. The red line shows the cumulative number of deaths.

People with specific developmental characteristics may experience greater psychological burden during the COVID-19 pandemic.15 34–38 However, there have been no reports on the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult healthcare workers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and/or autistic traits. In recent years, ADHD and autistic traits have been regarded as spectra and have been shown to co-occur.39 ADHD traits may make compliance with the COVID-19 precautions highly stressful; the increased risk of infection due to symptoms such as inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity can put the individuals and their families in danger and may also promote discrimination. Previous studies have shown that untreated ADHD is a risk factor for acquiring COVID-19.40 41 Meanwhile, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterised by intolerance to change and overestimation of variability in the surrounding environment.42 Therefore, autistic traits may make people vulnerable to depression and anxiety because of the need to adjust their daily lifestyles to the COVID-19 crisis. Considering this, we hypothesised that medical workers with developmental characteristics such as ADHD and autistic traits experience depression and anxiety symptoms to a greater extent during the COVID-19 outbreak. In testing this hypothesis, we conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the relationship between developmental characteristics and depressive/anxiety symptoms. We included COVID-19-related changes in lifestyle, changes in psychological and physical burdens of work, and current work status based on recent findings on COVID-19 and the psychological burden of healthcare workers,2–4 8–10 12 13 15–29 as well as the possibility of an association between individuals’ developmental characteristics evaluated using questionnaires as potential confounders. Our goal was to estimate the impact of ADHD and autism traits on depressive and anxiety symptoms in medical workers; however, we also discussed the effects of other factors as secondary outcomes.

Methods

Setting and study population

This study was conducted as part of a comprehensive research project (MEdical Workers’ MEntal health and Working conditions in Japan under the COVID-19 pandemic (MEW2-J-COVID) project) to investigate the mental health, work, lifestyle and distraction of medical workers after the COVID-19 outbreak. This cross-sectional web-based questionnaire survey was conducted between 1 October 2020 and 30 October 2020. Participants were recruited via snowball sampling. The method of dissemination was not specified; potential participants were asked to access the link to a Google Form containing the questionnaire posted on the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry website. Informed consent was obtained from all participants via the survey website.

Of the 712 participants who completed the Google Form questionnaire, the data of 683 participants were analysed. Data of 29 participants were excluded because they were duplicates (n=24), were under 20 years or not medical workers (n=3), contained garbled data (n=1) or contained invalid data on working hours (n=1). Of these, those not working at a medical institution (n=25) and working less than 15 days in a month (n=18) were excluded. Totally, 43 participants were excluded. Finally, 640 participants were included in the analyses.

Assessments

Questionnaires consisted of the sociodemographic questionnaire, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for estimating depressive symptoms,43 44 the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for assessing anxiety symptoms,45 46 the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-V.1.1) for estimating ADHD symptoms47 48 and the Autism Spectrum Quotient-10 (AQ-10) for quantifying autistic traits.49 50

Main outcome measures

Depression symptoms were assessed by the PHQ-9.43 44 Based directly on the nine diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),51 the scale consists of nine items that assess the frequency with which nine depressive symptoms had occurred in the past 2 weeks. Participants rated items as 0, 1, 2 or 3 for ‘not at all,’ ‘several days,’ ‘more than half the days’ and ‘nearly every day,’ respectively. Responses to each item were summed to provide a single score ranging from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Anxiety symptoms were assessed by the GAD-7.45 46 The GAD-7 is derived from the 13-item criteria for GAD in the DSM-IV.51 It consists of 7 items with the highest correlation to the 13-item scale score. Participants rated the frequency of seven anxiety symptoms during the last 2 weeks as 0, 1, 2 or 3 for ‘not at all,’ ‘several days,’ ‘more than half the days’ and ‘nearly every day,’ respectively. The responses to each item were summed to provide a single score ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety symptoms.

Predictors: developmental characteristics

ADHD traits were assessed by the ASRS-V1.1 Screener.47 48 The ASRS-V.1.1 Screener was derived from the 18-item criteria for ADHD in the DSM-IV,51 consisting of six questions considered most predictive of symptoms consistent with ADHD. The six-item questionnaire includes questions on inattention (four items) and hyperactivity symptoms (two items). Participants rated the frequency of ADHD symptoms over the past 6 months as 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 for ‘never,’ ‘rarely,’ ‘sometimes,’ ‘often,’ and ‘very often,’ respectively. The responses to each item were summed to provide a single score ranging from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating higher ADHD traits.

Autistic traits were assessed by the AQ-10.49 50 The AQ-50, an original version of the AQ-10, was originally developed as a tool for screening autistic traits in intellectually able adults. Although a short version of the AQ-50, the AQ-10 has been well validated for measuring autistic traits.52 Responses are rated on a four-point scale: ‘definitely disagree,’ ‘slightly disagree,’ ‘slightly agree’ and ‘definitely agree.’ Responses indicating autistic traits were scored 1, while other responses were scored 0 (for five items, ‘definitely disagree’ and ‘slightly disagree’ were scored 1, but for the five reverse-scored items, ‘slightly agree’ and ‘definitely agree’ were scored 1). The responses to each item were summed to provide a single score ranging from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating a higher level of autistic traits.

Predictors: changes in lifestyle

Regarding the changes in lifestyle after the COVID-19 outbreak, changes in physical and psychological burden were rated as ‘markedly decreased,’ ‘decreased,’ ‘unchanged,’ ‘increased,’ or ‘markedly increased’ as the answers to the question ‘How has the physical/mental burden of work changed compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic?’ Additionally, changes in income, frequency of going out and interpersonal interactions (including online interactions) were assessed by rate of change: ‘Greater than or equal to 150%,’ ‘110%–150%,’ ‘90%–110%,’ ‘50%–90%’ or ‘less than 50%,’ as the answers to the question ‘How has your income/ frequency of going out/ interpersonal interactions (including online interactions) changed compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic?’

Other covariates

The questionnaire included items on demographic characteristics, such as age (stratified by decade), sex, body mass index (BMI), residential area (urban, suburban or rural), number of households, smoking habit (yes/no), habitual alcohol consumption (yes/no) and history of COVID-19 infection (yes/no). Participants’ work status including occupation, commuting time (<30 min, 30 min to 1 hour or ≥1 hour), working hours per day and number of workdays per month, engagement in night-shift (yes/no), frequency of contact with confirmed/suspected COVID-19 patients, fear of COVID-19 (no fear, moderate fear or extreme fear), and experience of discrimination (a yes/no answer to the question, ‘After the COVID-19 epidemic, have you experienced discrimination in daycare centres, schools or from community residents because you are a medical worker?’) were also evaluated. In this study, we defined front-line workers as those directly involved in COVID-19 prevention and treatment and having direct contact with confirmed or suspected cases once or more than once a week.

Statistical analysis

A series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed to test the effects of developmental characteristics on depression (the score of the PHQ-9) after controlling for sociodemographic factors and changes in participants’ lives after the COVID-19 outbreak. First, developmental characteristics (the ASRS score and the AQ-10 score) were entered into the regression model (model 1). Second, changes in lifestyle after the COVID-19 outbreak (changes in physical and psychological burden, changes in income, frequency of going out, and interpersonal interaction) were entered into the regression model in the second step (model 2). Lastly, sociodemographic variables including age group, sex, BMI, residential area, number of households, habitual smoking and alcohol consumption, history of COVID-19 infection, work status (occupation, commuting time, working hours per month, engagement in night-shifts, whether a front-line worker or not), fear of COVID-19 and experience of discrimination were entered in the third and final step (model 3). Except for developmental characteristics, the variables used for adjustment were items that are considered to be associated with depression/anxiety in medical workers in previous studies.2–4 8–10 12 13 15–29 The same hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed to test the effects of developmental characteristics on anxiety (GAD-7 score). We used SPSS statistics V.22 (SPSS) to perform all analyses. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the production of this study.

Results

The 640 participants consisted of 270 (42.2%) physicians (including dentists), 190 (29.7%) nurses (including midwives) and 180 (28.1%) other workers (pharmacists (n=34), nutritionists (n=4), radiologists (n=4), clinical technologists (n=17), physical therapists (n=6), occupational therapists (n=14), certified orthoptists (n=1), clinical engineers (n=4), speech therapists (n=8), certified care workers (n=3), clinical psychologists (n=25), psychiatric social workers (n=13), music therapists (n=1), medical assistants (n=7) and office workers (n=39)). Most of the participants worked in hospitals (n=516), followed by outpatient clinics (n=88), and other medical institutions including pharmacies, long-term care facilities and public health centres (n=36). The respondents were aged between 20 and 70 (one respondent was in his 70s but was included in the ‘≥60’ category in the analysis), with the majority in their 30s and 40s (37.3% and 34.8%, respectively), and 359 (59.1%) were female. Only five participants (0.8%) had a history of COVID-19 infection. Forty-six participants (7.2%) were front-line workers. Other descriptive information of the participants is presented in table 1. A majority of the participants (85.4%) were concerned about COVID-19, and about 20% of them were extremely fearful of COVID-19 (17.7% of all participants). Discrimination against medical workers was experienced by 8.8% of the respondents. The prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥10), anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 ≥10), ADHD traits (ASRS≥14) and autistic traits (AQ-10 ≥6) were 77 (12.0%), 54 (8.4%), 65 (10.2%) and 64 (10.0%), respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic data and employment status of participants (n=640)

| Age group (years), N (%) | |

| 20–29 | 75 (11.7) |

| 30–39 | 239 (37.3) |

| 40–49 | 223 (34.8) |

| 50–59 | 74 (11.6) |

| ≥60 | 29 (4.5) |

| Female, N (%) | 359 (56.1) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 21.8 (20.1–24.2) |

| Residential area, N (%) | |

| Urban | 260 (40.6) |

| Suburban | 279 (43.6) |

| Rural | 101 (15.8) |

| No of households, N (%) | |

| 1 | 187 (29.7) |

| 2 | 139 (21.7) |

| 3 | 130 (20.3) |

| ≥4 | 184 (28.7) |

| Habitual smoking, N (%) | 60 (9.4) |

| Habitual alcohol consumption, N (%) | 170 (26.6) |

| COVID-19 infection, N (%) | 5 (0.8) |

| Occupation, N (%) | |

| Physician | 270 (42.2) |

| Nurse | 190 (29.7) |

| Other worker | 180 (28.1) |

| Commuting time, N (%) | |

| <30 min | 374 (58.4) |

| 30 min to 1 hour | 183 (28.6) |

| ≥1 hour | 83 (13.0) |

| Working hours, median (IQR), per month | 207.5 (187–247) |

| Working night-shift, N (%) | 316 (49.4) |

| Front-line worker, N (%) | 46 (7.2) |

| Fear of COVID-19, N (%) | |

| No fear | 94 (14.7) |

| Moderate fear | 433 (67.7) |

| Extreme fear | 113 (17.7) |

| Experience of discrimination, N (%) | 56 (8.8) |

| PHQ-9 score, median (IQR), points | 4 (1–8) |

| GAD-7 score, median (IQR), points | 2 (0–5) |

| ASRS score, median (IQR), points | 9 (6–11) |

| AQ-10 score, median (IQR), points | 3 (2–4) |

AQ-10, Autism-Spectrum Quotient-10; ASRS, Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Scale; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

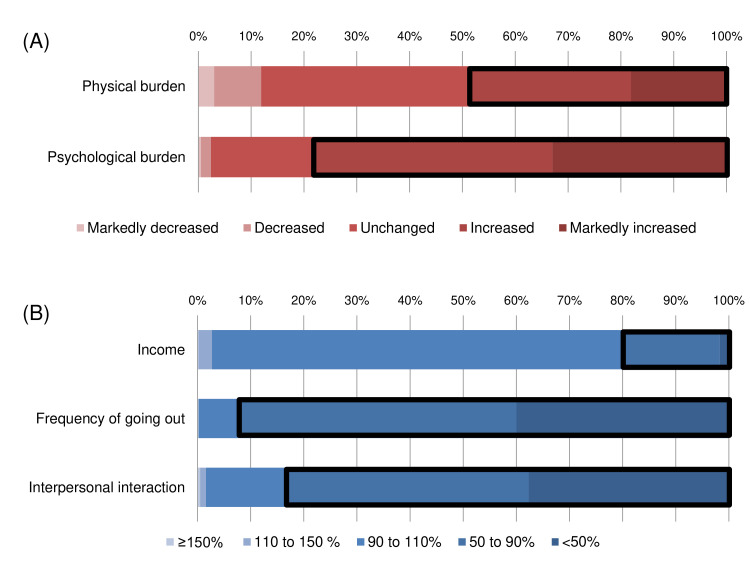

Changes in lifestyle (physical and psychological burden, income, frequency of going out and interpersonal interaction) are shown in figure 2. In terms of workload after the COVID-19 outbreak, 49.1% and 78.3% of the participants reported that their physical and psychological burdens increased, respectively. As for income, only 19.7% of the subjects experienced a decrease below 90%. Overall, a noticeable decrease in the frequency of going out was reported—92.2% reported reducing activities by 10% or more, and 40% reported reducing their activities by 50% or more. A similar decrease in interpersonal interaction was noted, with 83.5% reporting a decrease of less than 90% and 37.7% reporting a decrease of less than 50%.

Figure 2.

Changes in lifestyle among medical workers after the COVID-19 outbreak. (A) The bold square shows an increase in physical and psychological burden. (B) The bold square shows a decrease of less than 90%.

To evaluate the effect of developmental characteristics, changes in lifestyle due to COVID-19 and sociodemographic variables, we performed two separate regression analyses. For depression, the first model testing the contributions of developmental characteristics were statistically significant (R2=21.7%, p<0.001). The addition of changes in lifestyle due to COVID-19 (model 2) resulted in a significant increase in the R2 value (ΔR2=12.6%, p<0.001). The final model (the standard multiple regression analysis) in which all of the variables were entered simultaneously explained 43.3% of the variance in depression. Finally, ASRS score (β=0.390, p<0.001), AQ-10 score (β=0.069, p<0.05), changes in physical burden (β=0.121, p<0.01), changes in psychological burden (β=0.161, p<0.001), changes in interpersonal interaction (β=0.103, p<0.01), being female (β=0.199, p<0.001), BMI (β=0.094, p<0.01), number of households (β=−0.086, p<0.01), habitual smoking (β=0.068, p<0.05), other worker (β=0.130, p<0.001), working hours per month (β=0.083, p<0.05), fear of COVID-19 (β=0.135, p<0.001) and experience of discrimination (β=0.069, p<0.05) were identified as significant correlates of depression. However, the correlation between AQ-10 score and depression was not significant in the bivariate analysis (table 2).

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression model predicting depressive symptoms

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Step 1: Developmental characteristics | |||||||||

| ASRS score (continuous variable) | 0.562 | 0.043 | 0.463*** | 0.508 | 0.040 | 0.418*** | 0.474 | 0.039 | 0.390*** |

| AQ-10 score (continuous variable) | 0.045 | 0.096 | 0.017 | 0.113 | 0.089 | 0.042 | 0.186 | 0.086 | 0.069* |

| Step 2: Changes in lifestyle after the COVID-19 outbreak | |||||||||

| Changes in physical burden‡ | 0.745 | 0.190 | 0.151*** | 0.595 | 0.184 | 0.121** | |||

| Changes in psychological burden‡ | 1.315 | 0.244 | 0.216*** | 0.978 | 0.243 | 0.161*** | |||

| Changes in income§ | −0.124 | 0.319 | −0.013 | −0.196 | 0.313 | −0.020 | |||

| Changes in frequency of going out§ | −0.324 | 0.277 | −0.042 | −0.515 | 0.264 | −0.066 | |||

| Changes in interpersonal interaction§ | 0.791 | 0.226 | 0.124*** | 0.657 | 0.216 | 0.103** | |||

| Step 3: Sociodemographic variables | |||||||||

| Age group¶ | −0.045 | 0.159 | −0.009 | ||||||

| Female (yes) | 1.937 | 0.358 | 0.199*** | ||||||

| Body mass index (continuous variable) | 0.134 | 0.047 | 0.094** | ||||||

| Residential area†† | −0.223 | 0.230 | −0.033 | ||||||

| No of households‡‡ | −0.349 | 0.132 | −0.086** | ||||||

| Habitual smoking (yes) | 1.137 | 0.526 | 0.068* | ||||||

| Habitual alcohol consumption (yes) | 0.448 | 0.348 | 0.041 | ||||||

| History of COVID-19 infection (yes) | 2.021 | 1.693 | 0.037 | ||||||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Physician (reference) | — | — | |||||||

| Nurse | −0.131 | 0.425 | −0.012 | ||||||

| Other worker | 1.399 | 0.423 | 0.130*** | ||||||

| Commuting time§§ | −0.067 | 0.217 | −0.010 | ||||||

| Working hours per month (continuous variable) | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.083* | ||||||

| Working night shift (yes) | −0.099 | 0.343 | −0.010 | ||||||

| Front-line worker (yes) | 0.233 | 0.602 | 0.012 | ||||||

| Fear of COVID-19¶¶ | 1.151 | 0.278 | 0.135*** | ||||||

| Experience of discrimination (yes) | 1.176 | 0.548 | 0.069* | ||||||

| Fit test | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.217 | 0.342 | 0.433 | ||||||

| Change in R2 | 0.217 | 0.126 | 0.091 | ||||||

*P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

†Evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

‡Markedly decreased=1, decreased=2, not changed=3, increased=4, and markedly increased=5.

§≥150=1, 110%–15%=2, 90%–110%=3, 50%–90%=4 and <50%=5.

¶20–29=1, 30–39=2, 40–49=3, 50–59=4 and 60 or over 60=5.

††Urban=1, suburban=2, rural=3.

‡‡4 or more than 4 was calculated as '4'.

§§<30 min=1, 30 min to 1 hour=2, ≥1 hour=3.

¶¶No fear=1, moderate fear=2, extreme fear=3.

AQ-10, the Autism-Spectrum Quotient-10; ASRS, the Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Scale.

For anxiety, the first model testing the contributions of developmental characteristics were statistically significant (R2=22.5%, p<0.001). The addition of changes in lifestyle with COVID-19 (model 2) resulted in a significant increase in the R2 value (ΔR2=10.5%, p<0.001). The final full model (the standard multiple regression analysis) in which all of the variables were entered simultaneously explained 39% of the variance in anxiety. Finally, the ASRS score (β=0.426, p<0.001), changes in physical burden (β=0.120, p<0.01), changes in psychological burden (β=0.146, p<0.001), being female (β=0.089, p<0.05), other worker (β=0.123, p<0.001), fear of COVID-19 (β=0.170, p<0.001), and experience of discrimination (β=0.067, p<0.05) were identified as significant correlates of anxiety (table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression model predicting anxiety symptoms

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Step 1: Developmental characteristics | |||||||||

| ASRS score (continuous variable) | 0.480 | 0.036 | 0.472*** | 0.438 | 0.034 | 0.431*** | 0.433 | 0.033 | 0.426*** |

| AQ-10 score (continuous variable) | 0.029 | 0.080 | 0.013 | 0.079 | 0.075 | 0.035 | 0.117 | 0.075 | 0.052 |

| Step 2: Changes in lifestyle after the COVID-19 outbreak | |||||||||

| Changes in physical burden‡ | 0.643 | 0.160 | 0.156*** | 0.492 | 0.159 | 0.120** | |||

| Changes in psychological burden‡ | 0.969 | 0.206 | 0.191*** | 0.743 | 0.211 | 0.146*** | |||

| Changes in income§ | 0.007 | 0.269 | 0.001 | −0.116 | 0.272 | −0.014 | |||

| Changes in frequency of going out§ | −0.223 | 0.233 | −0.034 | −0.257 | 0.229 | −0.040 | |||

| Changes in interpersonal interaction§ | 0.507 | 0.190 | 0.095** | 0.367 | 0.188 | 0.069 | |||

| Step 3: Sociodemographic variables | |||||||||

| Age group¶ | 0.212 | 0.138 | 0.052 | ||||||

| Female (yes) | 0.727 | 0.310 | 0.089* | ||||||

| Body mass index (continuous variable) | −0.015 | 0.040 | −0.013 | ||||||

| Residential area†† | −0.061 | 0.200 | −0.011 | ||||||

| No of households‡‡ | −0.066 | 0.114 | −0.019 | ||||||

| Habitual smoking (yes) | 0.336 | 0.456 | 0.024 | ||||||

| Habitual alcohol consumption (yes) | 0.244 | 0.302 | 0.027 | ||||||

| History of COVID-19 infection (yes) | 1.870 | 1.469 | 0.041 | ||||||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Physician (reference) | — | — | |||||||

| Nurse | −0.031 | 0.369 | −0.004 | ||||||

| Other worker | 1.108 | 0.367 | 0.123** | ||||||

| Commuting time§§ | −0.169 | 0.188 | −0.030 | ||||||

| Working hours per month (continuous variable) | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.015 | ||||||

| Working night shift (yes) | 0.071 | 0.298 | 0.009 | ||||||

| Front-line worker (yes) | 0.434 | 0.522 | 0.028 | ||||||

| Fear of COVID-19¶¶ | 1.214 | 0.241 | 0.170*** | ||||||

| Experience of discrimination (yes) | 0.956 | 0.475 | 0.067* | ||||||

| Fit test | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.225 | 0.330 | 0.390 | ||||||

| Change in R2 | 0.225 | 0.105 | 0.060 | ||||||

*P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

†Evaluated using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7.

‡†Markedly decreased=1, decreased=2, not changed=3, increased=4, and markedly increased=5.

§≥150=1, 110%–15%=2, 90%–110%=3, 50%–90%=4 and <50%=5.

¶20–29=1, 30–39=2, 40–49=3, 50–59=4 and 60 or over 60=5.

††Urban=1, suburban=2, rural=3.

‡‡4 or more than 4 was calculated as '4'.

§§<30 min=1, 30 min to 1 hour=2, ≥1 hour=3.

¶¶No fear=1, moderate fear=2, extreme fear=3.

AQ-10, the Autism-Spectrum Quotient-10; ASRS, the Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Scale.

Discussion

This study was conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak, but is the first study investigating the influence of developmental characteristics on depression and anxiety in medical workers. Results indicated that ADHD traits might have a strong influence on depression and anxiety symptoms even after controlling for physical and psychological burden and fear of COVID-19, with its effect possibly being greater than other factors, including autistic traits.

In general, and not only during a pandemic, the relationship between ADHD and depression or anxiety has already been addressed.53–58 Additionally, patients with ASD in general are more prone to developing depression and anxiety.16 However, in this study, wherein a strong correlation was found between ADHD traits and depression/anxiety symptoms, there was no significant correlation for autistic traits. The difference in the association between the two traits for depression/anxiety is not clear. One possible reason for the strong correlation between ADHD traits and depression/anxiety is that people with ADHD traits may have faced a higher risk of infection due to their own inattention and impulsivity, which can be an obvious stressor among medical workers. Even though untreated ADHD is a risk factor for acquiring COVID-19,40 41 the relationship between ADHD traits and compliance with infection control measures under the pandemic remains unclear and should be examined in the future. Further, due to the calls for self-restraint by government leaders,31 those with high ADHD traits may have experienced high stress59; self-restraint prevents one from engaging in a variety of activities, and it would be difficult for people with ADHD traits to adapt to such activities even after months or years. Meanwhile, against the intolerance of change in ASD,42 people with autistic traits may have shown some level of adaption to the situation, as the survey was conducted more than 6 months after the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, unnecessary outings or interpersonal interactions, which can be stressors for people with autistic traits,60 have been reduced due to COVID-19. It is also noteworthy that the correlation between autistic traits and depression, which was not significant in the bivariate analysis, was significant in the multivariate analysis. This makes it undeniable that autistic traits are also a unique factor that can be associated with depression. As there have been no studies that examined developmental characteristics and their psychological effects in the general adult population, it can be inferred that the relationship between psychological burden and ADHD or autistic traits after the COVID-19 outbreak should be evaluated and further investigated not only among healthcare workers but also among the general population. Contrary to the above hypothesis that reducing unnecessary interpersonal interaction could be protective for individuals with autistic traits, this study highlighted the importance of maintaining interpersonal interactions to fight depression. Both belonging to a large household and maintaining interpersonal interactions had a protective effect against depression symptoms. This result is consistent with the known importance of receiving direct social support from friends, family, colleagues and supervisors during a pandemic, which has already been suggested in numerous studies.3 4 8–10 12 In this study, the association between changes in interpersonal interaction and anxiety symptoms was not significant; this may be because reduced interpersonal interaction may lower the risk of infection and could thus reduce anxiety. Contrarily, the experience of discriminatory treatment was independently associated with both depression and anxiety symptoms. The negative psychological impact of discrimination on healthcare workers has been reported in previous pandemics, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome or other viral infections.3 4 This study’s results are consistent with the findings of the COVID-19 outbreak, which also revealed the incidence of mental disorders due to discrimination.22–25

Factors related to employment can also be a psychological burden for medical workers. Several studies have shown that the psychological burden on healthcare workers is high not only in countries severely affected by the pandemic but also in relatively unaffected countries.17 18 21 29 We found that the physical and psychological burden of the COVID-19 outbreak was increased in around 50% and 80% of medical workers, respectively. Both increases in psychological and physical burden were independently associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety, which is consistent with previous studies.19 20 It has also been reported that protective garments can increase physical burden61 62 and that strict infection control measures can increase stress levels.19 In addition to changes in physical and psychological burden, long working hours were significantly correlated with depression symptoms in this study. This was consistent with some studies on the association between long working hours and depression or increased stress under the COVID-19 outbreak.27 28 Furthermore, a significant association between the fear of COVID-19, depression and anxiety has been replicated, which is consistent with previous study findings.2 4 10 Despite the increased psychological and physical burden and fear of COVID-19, the prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety was lower than among healthcare workers in other nations.7 9 13 14 17 This may reflect the low number of dominant COVID-19 patients and the low number of deaths due to COVID-19 in Japan as compared with other countries.30 In addition, the low prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety could be attributed to the current study’s small sample of medical workers who had direct contact with COVID-19 patients compared with the sample size in previously conducted studies.11–13 63 64 Besides, unlike previous reports on the general population,65–68 the association between the income loss associated with the COVID-19 outbreak, depression and anxiety was not clear in this study. This can be due to the limited number of medical workers who experienced a decline in income; the impact could be greater if the economy had collapsed, and their incomes had drastically decreased.

The current results suggested that, remarkably, medical workers other than physicians or nurses have an independent risk of both depression and anxiety. In terms of occupation, although front-line physicians had a higher incidence of depression than other occupations,14 numerous studies on healthcare workers have reported lower depression and anxiety in physicians than in other occupations,3 4 7–9 13 21 26 as in this study. For healthcare workers other than physicians and nurses, one study reported that anxiety was significantly higher, but depression was comparable.69 Another study conducted on a cruise ship during the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic in Japan reported that distress was significantly stronger among clerical workers than physicians or nurses,70 which are consistent with the results of the current study. Even in healthcare workers, inadequate medical knowledge was reported to be associated with increased levels of anxiety and depression.3 71 72 Moreover, numerous reports have stated that fewer years of healthcare experience was associated with worse mental health outcomes3 7; other medical workers in this study may have had less experience in infection prevention. Therefore, both job-specific support and appropriate knowledge development would be important to improve the psychological burden of medical workers.

In terms of demographic variables, being female, BMI and smoking habits were independently associated with depression symptoms. Being female was also independently associated with anxiety symptoms. The association between age and depression/anxiety was not noticeable in this study; it is still controversial in previous reports examining the association between age and psychological burden in healthcare workers under the pandemic.5 9 12 17 18 21 26 27 The association between BMI, smoking habits, and depression has long been shown in the general population73 74 and may not be unique to the COVID-19 outbreak. The association of sex, especially being a woman with depression and anxiety, has been reported in a number of studies conducted on healthcare workers after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.2–4 8 12 13 15–17 21 26 This may also reflect the higher prevalence of depression and anxiety among women in the general population75 76; however, these relationships can be unique to the COVID-19 pandemic. Experimental studies have shown that women are more responsive to neural networks associated with fear and arousal responses than men77; the response to fear associated with COVID-19 may have been stronger in women than men. In addition, there are indications that the sociological burden on women has increased after the COVID-19 outbreak.78 Moreover, a longitudinal study of women with children showed that depression and anxiety were higher among women who had disrupted income, difficulty balancing work and family education, and difficulty obtaining daycare.79 Indeed, in Japan, it has been reported that suicide among women increased significantly after the COVID-19 outbreak.80 The direct causes of depression and anxiety in females, and what interventions are best for them should be examined in the future.

There are some limitations to this study. First, this study adopted the snowball sampling strategy with online recruitment, and thus did not specify how the questionnaire was disseminated. While this approach is valuable for exploratory studies and provides access to the target population and is used in some epidemiological studies to examine the psychological burden of healthcare workers under the COVID-19 outbreak,26 27 71 72 it can still hinder the generalisability of the results as the representativeness of the sample is not guaranteed. In particular, the reliability of the prevalence rate remains problematic. Second, the participants with ADHD or autistic traits in this study were not formally diagnosed as having ADHD or ASD. In addition, determining whether they are traits or symptoms can be difficult using the questionnaire method. The possibility that ADHD and autistic symptoms can change with age81 is also a limitation of this study. Third, the clinically significant depressive and anxiety symptoms in this study were not those of formally diagnosed major depressive disorder or GAD-7, respectively. Furthermore, the ASRS-V1.1, AQ-10, PHQ-9 and GAD-7 used in this study are all based on the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and not on the latest DSM-5.82 Fourth, the questionnaire did not include whether the respondents were receiving treatment for mental or physical illnesses, so the influence of comorbidities could not be verified in this study. Fifth, the study only examined the changes in income, frequency of going out and interpersonal interaction, and did not assess baseline status. In particular, we did not investigate economic status, which is thought to strongly influence depression and anxiety. As this study included people working in medical institutions, it may have been biased toward middle-income and high-income populations in Japan. Lastly, owing to the observational nature of the study, our findings did not show a direct causal relationship between developmental characteristics and psychological burden. In addition, as this study was conducted anonymously, it is not possible to conduct further longitudinal studies using the same participants.

This study suggested that individual developmental characteristics, especially ADHD traits, have a considerable effect on the psychological health of medical workers. In contrast, the relationship between autistic traits and depression/anxiety symptoms was less significant. Identifying the stressors in medical workers with high ADHD traits and the subsequent development of appropriate interventions for them are warranted. Furthermore, as this was a cross-sectional study, causality cannot be determined. To verify the relationship between specific developmental characteristics and stress-related outcomes, further prospective studies with both healthcare workers and the general population should be conducted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the respondents of the survey for providing us with valuable data. We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.com/) for their English language editing.

Footnotes

KM and KK contributed equally.

Contributors: KM, RO, NA and MH had full access to all of the data and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: KM, TY, AT, KN, TU, KY and KK. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: KM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: KM. Obtained funding: KM. Supervision: TY, MF and KK. KM is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor. All authors have contributed significantly to this work and have met the qualification of authorship.

Funding: This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (No. 19K17098).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (A2020-044). All subjects provided their informed consent electronically prior to the enrolment. On the informed consent page, dichotomic option was presented: yes or no. Only subjects who selected 'yes' were directed to the questionnaire page, and subjects could terminate their participation at any time. The data collected did not contain any personal information.

References

- 1.Chew QH, Wei KC, Vasoo S, et al. Psychological and coping responses of health care workers toward emerging infectious disease outbreaks: a rapid review and practical implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81. 10.4088/JCP.20r13450. [Epub ahead of print: 20 10 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Meneses-Echavez JF, Ricci-Cabello I, et al. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2020;277:347–57. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirois FM, Owens J. Factors associated with psychological distress in health-care workers during an infectious disease outbreak: a rapid systematic review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:589545. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabarkapa S, Nadjidai SE, Murgier J, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: a rapid systematic review. Brain Behav Immun Health 2020;8:100144. 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, et al. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;369:m1642. 10.1136/bmj.m1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang Y-T, Yang Y, Li W, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:228–9. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanghera J, Pattani N, Hashmi Y, et al. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital setting-A systematic review. J Occup Health 2020;62:e12175. 10.1002/1348-9585.12175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:901–7. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, et al. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2020;291:113190. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller AE, Hafstad EV, Himmels JPW, et al. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res 2020;293:113441. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.da Silva FCT, Neto MLR. Psychiatric symptomatology associated with depression, anxiety, distress, and insomnia in health professionals working in patients affected by COVID-19: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2021;104:110057. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun 2020;89:531–42. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vizheh M, Qorbani M, Arzaghi SM, et al. The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2020;19:1967–78. 10.1007/s40200-020-00643-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salari N, Khazaie H, Hosseinian-Far A, et al. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-regression. Hum Resour Health 2020;18:100. 10.1186/s12960-020-00544-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mutluer T, Doenyas C, Aslan Genc H. Behavioral implications of the Covid-19 process for autism spectrum disorder, and individuals' comprehension of and reactions to the pandemic conditions. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:561882. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.561882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollocks MJ, Lerh JW, Magiati I, et al. Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2019;49:559–72. 10.1017/S0033291718002283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nayak BS, Sahu PK, Ramsaroop K, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depression, anxiety and stress among healthcare workers of Trinidad and Tobago during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e044397. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran TV, Nguyen HC, Pham LV, et al. Impacts and interactions of COVID-19 response involvement, health-related behaviours, health literacy on anxiety, depression and health-related quality of life among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e041394. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:306. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du J, Dong L, Wang T, et al. Psychological symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2020;67:144–5. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatzittofis A, Karanikola M, Michailidou K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18. 10.3390/ijerph18041435. [Epub ahead of print: 03 02 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rana W, Mukhtar S, Mukhtar S. Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;51:102080. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh R, Subedi M. COVID-19 and stigma: social discrimination towards frontline healthcare providers and COVID-19 recovered patients in Nepal. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;53:102222–22. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdel Wahed WY, Hefzy EM, Ahmed MI, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and perception of health care workers regarding COVID-19, a cross-sectional study from Egypt. J Community Health 2020;45:1242–51. 10.1007/s10900-020-00882-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharyya R, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Attitude, practice, behavior, and mental health impact of COVID-19 on doctors. Indian J Psychiatry 2020;62:257–65. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_333_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2010185. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song X, Fu W, Liu X, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:60–5. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mo Y, Deng L, Zhang L, et al. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J Nurs Manag 2020;28:1002–9. 10.1111/jonm.13014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu M-Y, Ahorsu DK, Kukreti S, et al. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, sleep problems, and psychological distress among COVID-19 frontline healthcare workers in Taiwan. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:705657. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.705657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johns Hopkins University . COVID-19 Dashboard by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE). Available: https:coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.htmlhttps:coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Accessed 15 Feb 2021].

- 31.Tokumoto A, Akaba H, Oshitani H, et al. COVID-19 health system response monitor: Japan. New Delhi: World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furuse Y, Sando E, Tsuchiya N, et al. Clusters of coronavirus disease in communities, Japan, January–April 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26:2176–9. 10.3201/eid2609.202272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA 2018;320:1131–50. 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colizzi M, Sironi E, Antonini F, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in autism spectrum disorder: an online parent survey. Brain Sci 2020;10. 10.3390/brainsci10060341. [Epub ahead of print: 03 06 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melegari MG, Giallonardo M, Sacco R, et al. Identifying the impact of the confinement of Covid-19 on emotional-mood and behavioural dimensions in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res 2021;296:113692. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bobo E, Lin L, Acquaviva E, et al. [How do children and adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) experience lockdown during the COVID-19 outbreak?]. Encephale 2020;46:S85–92. 10.1016/j.encep.2020.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sciberras E, Patel P, Stokes MA, et al. Physical health, media use, and mental health in children and adolescents with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. J Atten Disord 2020:1087054720978549 (published Online First: 2020/12/18). 10.1177/1087054720978549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amorim R, Catarino S, Miragaia P, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on children with autism spectrum disorder. Rev Neurol 2020;71:285–91. 10.33588/rn.7108.2020381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antshel KM, Russo N, Disorders AS. Autism spectrum disorders and ADHD: overlapping phenomenology, diagnostic issues, and treatment considerations. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2019;21:34. 10.1007/s11920-019-1020-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merzon E, Manor I, Rotem A, et al. Adhd as a risk factor for infection with Covid-19. J Atten Disord 2021;25:1783–90. 10.1177/1087054720943271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry 2021;20:124–30. 10.1002/wps.20806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawson RP, Mathys C, Rees G. Adults with autism overestimate the volatility of the sensory environment. Nat Neurosci 2017;20:1293–9. 10.1038/nn.4615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muramatsu K, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K, et al. Performance of the Japanese version of the patient health Questionnaire-9 (J-PHQ-9) for depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018;52:64–9. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Validation and utility of a Japanese version of the GAD-7 2009.

- 47.Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, et al. The world Health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med 2005;35:245–56. 10.1017/S0033291704002892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kessler RC, Adler LA, Gruber MJ, et al. Validity of the world Health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS) screener in a representative sample of health plan members. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2007;16:52–65. 10.1002/mpr.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, et al. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord 2001;31:5–17. 10.1023/A:1005653411471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurita H, Koyama T, Osada H. Autism-Spectrum Quotient-Japanese version and its short forms for screening normally intelligent persons with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005;59:490–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Psychiatric Association . DSM-Iv: diagnostic and statistical manual. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lundin A, Kosidou K, Dalman C. Measuring autism traits in the adult general population with the brief autism-spectrum quotient, AQ-10: findings from the Stockholm public health cohort. J Autism Dev Disord 2019;49:773–80. 10.1007/s10803-018-3749-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nankoo MMA, Palermo R, Bell JA, et al. Examining the rate of self-reported ADHD-Related traits and endorsement of depression, anxiety, stress, and autistic-like traits in Australian university students. J Atten Disord 2019;23:869–86. 10.1177/1087054718758901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Combs MA, Canu WH, Broman-Fulks JJ, et al. Perceived stress and ADHD symptoms in adults. J Atten Disord 2015;19:425–34. 10.1177/1087054712459558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evren B, Evren C, Dalbudak E, et al. The impact of depression, anxiety, neuroticism, and severity of Internet addiction symptoms on the relationship between probable ADHD and severity of insomnia among young adults. Psychiatry Res 2019;271:726–31. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen Y, Zhang Y, Chan BSM, et al. Association of ADHD symptoms, depression and suicidal behaviors with anxiety in Chinese medical college students. BMC Psychiatry 2020;20:180. 10.1186/s12888-020-02555-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohamed SMH, Börger NA, van der Meere JJ. Executive and daily life functioning influence the relationship between ADHD and mood symptoms in university students. J Atten Disord 2021;25:1731–42. 10.1177/1087054719900251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oh Y, Yoon HJ, Kim J-H, et al. Trait anxiety as a mediator of the association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptom severity and functional impairment. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2018;16:407–14. 10.9758/cpn.2018.16.4.407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jarrett MA. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and executive functioning in emerging adults. Psychol Assess 2016;28:245–50. 10.1037/pas0000190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howlin P, Magiati I. Autism spectrum disorder: outcomes in adulthood. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017;30:69–76. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Epstein Y, Heled Y, Ketko I, et al. The effect of air permeability characteristics of protective garments on the induced physiological strain under exercise-heat stress. Ann Occup Hyg 2013;57:866–74. 10.1093/annhyg/met003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davey SL, Lee BJ, Robbins T, et al. Heat stress and PPE during COVID-19: impact on healthcare workers' performance, safety and well-being in NHS settings. J Hosp Infect 2021;108:185–8. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, et al. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res 2020;288:112936. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fukase Y, Ichikura K, Murase H, et al. Depression, risk factors, and coping strategies in the context of social dislocations resulting from the second wave of COVID-19 in Japan. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:33. 10.1186/s12888-021-03047-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuang Y, Shen M, Wang Q, et al. Association of outdoor activity restriction and income loss with patient-reported outcomes of psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;83:670–2. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shevlin M, McBride O, Murphy J, et al. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open 2020;6:e125. 10.1192/bjo.2020.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Witteveen D, Velthorst E. Economic hardship and mental health complaints during COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:27277–84. 10.1073/pnas.2009609117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, BYQ T, GKH L, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:317–20. 10.7326/M20-1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ide K, Asami T, Suda A, et al. The psychological effects of COVID-19 on hospital workers at the beginning of the outbreak with a large disease cluster on the diamond Princess cruise SHIP. PLoS One 2021;16:e0245294. 10.1371/journal.pone.0245294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cag Y, Erdem H, Gormez A, et al. Anxiety among front-line health-care workers supporting patients with COVID-19: a global survey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2021;68:90–6. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.García-Fernández L, Romero-Ferreiro V, López-Roldán PD, et al. Mental health impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers. Psychol Med 2020:1–3 (published Online First: 2020/05/28). 10.1017/S0033291720002019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anda RF, et al. Depression and the dynamics of smoking. JAMA 1990;264:1541–5. 10.1001/jama.1990.03450120053028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, et al. Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res 2010;178:230–5. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 2000;177:486–92. 10.1192/bjp.177.6.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, et al. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45:1027–35. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Felmingham K, Williams LM, Kemp AH, et al. Neural responses to masked fear faces: sex differences and trauma exposure in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2010;119:241–7. 10.1037/a0017551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McLaren HJ, Wong KR, Nguyen KN, et al. Covid-19 and Women’s Triple Burden: Vignettes from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia. Soc Sci 2020;9:87. 10.3390/socsci9050087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Racine N, Hetherington E, McArthur BA, et al. Maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2021;8:405–15. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00074-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nomura S, Kawashima T, Yoneoka D, et al. Trends in suicide in Japan by gender during the COVID-19 pandemic, up to September 2020. Psychiatry Res 2021;295:113622. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hartman CA, Geurts HM, Franke B, et al. Changing ASD-ADHD symptom co-occurrence across the lifespan with adolescence as crucial time window: illustrating the need to go beyond childhood. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;71:529–41. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth ED. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.