Abstract

The nonstopping increment of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration keeps harming the environment and human life. The traditional concept of carbon capture and storage (CCS) is no longer sufficient and has already been corrected to carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS). CCUS involves significant CO2 utilization, such as cyclic carbonate formation, for its cost effectiveness, less toxicity, and abundant C1 synthon in organic synthesis. However, the high thermodynamic and kinetic stability of CO2 limits its applications. Herein, we report a mild, efficient, and practical catalyst based on abundant, nontoxic CaI2 in conjunction with biocompatible ligand 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)-methylamino]-propane (BTP) for CO2 fixation under atmospheric pressure with terminal epoxides to give the cyclic carbonates. The Job plot detected the 1:1 Ca2+/BTP binding stoichiometry. Furthermore, formation of a single crystal of the 1:1 Ca2+/BTP complex was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray crystallography. The bis(cyclic carbonate) products exhibit potentials for components in the non-isocyanate polyurethanes (NIPUs) process. Notably, this protocol shows attractive recyclability and reusability.

Introduction

In the past few centuries, reliance on fossil fuel for energy production keeps on increasing due to human civilization. Emission of CO2, a green house gas, becomes a serious problem nowadays.1−3 Therefore, the concept of carbon capture and storage (CCS) came into being. CCS served as a technology for the reduction of waste CO2 in the atmosphere during the usage of fossil fuels. It contains capture of CO2 at emission sources and compressing, transporting, and storing it in a deep and secure geographic location.4−6 However, CCS is no longer satisfactory for existing demand. Designing novel ways for sustainable utilization of CO2 become a focus of researchers. Accordingly, CCS has already been corrected to carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS). The field of CCUS could be roughly divided into two parts. The first one involves no chemical conversion of CO2, such as CO2 flooding in the petroleum industry, utilizing the good miscibility and hydrophobicity of supercritical CO2 against oil to increase the efficiency of oil extraction.7−9 The second part engages in the conversion of CO2 to highly economical products. Although CO2 is less toxic and almost costless, and an abundant C1 synthons in organic synthesis,10−16 the high thermodynamic and kinetic stability of CO2 are hurdles for its utilization.17 To overcome this barrier, the development of effective catalysts is highly desired.18−22 Among various approaches of CO2 fixation, cyclic carbonate formation from CO2 with strained epoxides is one promising route.23−27 In particular, the preparation of bis(cyclic carbonates) has drawn a lot of attention because of its potential in the non-isocyanate polyurethane (NIPU) synthesis, which can be used to replace the conventional toxic phosgene process.28−31

Effective catalysts have to be able to significantly reduce the activation energy barrier and preclude the byproduct formation. Many transition-metal complexes have been explored for the CO2 to cyclic carbonate conversion.32−36 However, the heavy metal pollution issues are the drawbacks and concerns. On the contrary, main group metals are abundant on the earth’s crust and relatively inexpensive and less toxic.37−39 However, the solubility of these metal salts in the standard organic solvents is usually poor. Therefore, the addition of ligands or cocatalysts is a commonly favored method.

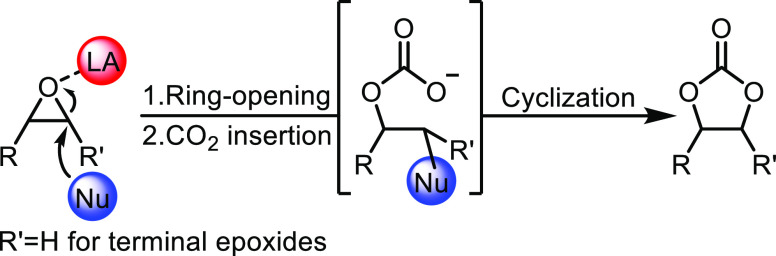

Previously, He and co-workers, in 2016, reported a catalytic system consisting of CaBr2 and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]-undec-7-ene (DBU) that could activate the fixation of CO2 with epoxides under atmosphere.40 Additionally, Werner and co-workers showed that calcium-based crown ether and polyether complexes could implement effectively in the synthesis of cyclic carbonate under mild conditions.41−43 Their systems both exhibited eye-catching catalytic activity in the conversion of terminal and internal epoxides, as shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Cyclic Carbonate from Terminal and Internal Epoxides.

Thus, extensive research efforts have been devoted to the development of a calcium catalyst. Among the studies on calcium-based catalysts and ligands with the hydroxy group, Wu and co-workers reported that the CaI2/N-methyldiethanolamine (MDEA) system displays good results for CO2 fixation of epoxides without resorting to harsh conditions.44 The complexation of calcium by a multifunctional ligand, e.g., the amino and hydroxy groups, could increase the solubility of the metal salt and amplify the dissociation of the anion for better nucleophilicity. Meanwhile, except for the coordination between the epoxide and the Lewis acidic calcium cation, the vicinal hydroxy groups would also serve as another activation by multisite hydrogen-bonding interactions, whereas the epoxide can be activated through a Lewis acid and nucleophile push–pull ring-opening mechanism.45,46 Additionally, alkanolamine based reagents can also function as CO2 scrubbing agents in the industry for ameliorating anthropogenic CO2 emission.47−51

Results and Discussion

As part of the aforementioned endeavor, we focus on the development of robust catalytic systems for the above conversion in high efficiency. Herein, we report the discovery of 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)-methylamino]-propane (BTP) as an effective ligand that shows excellent activity for catalyzing the above reaction. BTP has been used as a wet CO2 scrubbing agent to form a carbamic acid dimer in DMSO while also having served as a bridging ligand in a transition-metal complex.47,52

Ligands would play important roles in controlling the catalytic chemistry. To sort out the factors that can facilitate the cyclic carbonate formation, we have selected a series of ligands labled as La to Lh in Scheme 2 to study. MDEAPS (1-propanaminium, N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-N-methyl-3-sulfo-, inner salt) has a zwitterionic skeleton; BT (2,2-bis(hydroxymethyl)-2,2′,2″-nitrilotriethanol) can provide more hydrogen-bonding sites; BTP, DBPDA (N1,N3-dibenzylpropane-1,3-diamine), DTBPDA (N1,N3-di-tert-butylpropane-1,3-diamine) are bidentate diamino ligands; however, only BTP can provide ample hydrogen-bonding sites to guide the nucleophilic iodide for the epoxide ring-opening and intramolecular cyclic carbonate formation. THPP (Tris(hydroxypropyl)phosphine) and THMP (Tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphine) contain phosphine as the ligating atom. MDEA, which has been studied by Wu, is used as our reference ligand for comparison.44

Scheme 2. Chemical Structures of Complexing Ligands.

Bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (1a) was chosen as the model compound for the optimization of CO2 fixation experiments as shown in Scheme 3. The reaction of 1a (1.0 equiv) with atmospheric CO2 was implemented by loading 10 mol % calcium salt, 10 mol % ligand, and anhydrous solvent (5 M relative to 1a) at 60 °C. The degree of conversion was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy at 2, 4, 6, and 24 h and is summarized in Table 1, entries 1–26.

Scheme 3. Model Reaction for the Optimization Table.

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditionsa.

| conversion (%) atb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Ca salt | ligand | solvent | 2 h | 4 h | 6 h | 24 h |

| 1 | CaI2 | w/o ligand | DMSO | 17 | 21 | 27 | 63 |

| 2 | CaI2 | MDEAPS | DMSO | 35 | 45 | 61 | 99 |

| 3 | CaI2 | MDEAPS | PC | 10 | 19 | 28 | 57 |

| 4 | CaI2 | w/o ligand | PC | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| 5 | CaI2 | MDEA | PC | 23 | 47 | 69 | 94 |

| 6 | CaI2 | MDEA | DMSO | 42 | 77 | 99 | 99 |

| 7 | CaCO3 | MDEA | PC | 3 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 8 | CaCO3 | MDEA | DMSO | 3 | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| 9 | CaCO3 | BTP | DMSO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | CaI2 | BTP | DMSO | 87 | 95 | 98 | 99 |

| 11 | CaI2 | BT | DMSO | 30 | 37 | 55 | 98 |

| 12 | Ca(I3)2 | MDEA | PC | 55 | 86 | 96 | 99 |

| 13 | Ca(I3)2 | MDEA | DMSO | 53 | 73 | 99 | 99 |

| 14 | Ca(I3)2 | BTP | PC | 2 | 7 | 15 | 35 |

| 15 | Ca(I3)2 | BTP | DMSO | 30 | 45 | 50 | 92 |

| 16 | Ca(I3)2 | BT | DMSO | 5 | 29 | 48 | 87 |

| 17 | Ca(I3)2 | w/o ligand | DMSO | 2 | 40 | 88 | 99 |

| 18 | CaI2 | DBPDA | DMSO | 49 | 82 | 88 | 93 |

| 19 | CuI | BTP | DMSO | 18 | 34 | 46 | 73 |

| 20 | Ca(OTf)2 | BTP | DMSO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | CaI2 | DTBPDA | DMSO | 42 | 59 | 80 | 99 |

| 22 | CaI2 | THPP | DMSO | 42 | 70 | 93 | 99 |

| 23 | Ca(I3)2 | THPP | DMSO | 34 | 54 | 71 | 94 |

| 24 | CaI2 | THMP | DMSO | 38 | 65 | 93 | 99 |

| 25 | CaI2 | BTP | DMF | 23 | 40 | 54 | 99 |

| 26 | CaCl2 | BTP | DMSO | 4 | 5 | 8 | 22 |

All reactions were performed with (1.0 mmol) 1a, (10 mol %) catalyst, and (10 mol %) ligand in an (0.2 mL) anhydrous solvent.

Conversion rate was monitored by crude 1H NMR analysis.

The degree of conversion at 2 h reflects the initial rate of the reaction. This was used as an indicator for the catalytic reactivity for comparison. The presence of ligands is essential for the reaction; in the absence of the ligands, the reaction becomes very sluggish (entries 1, 4, and 17). While CaI2 and Ca(I3)2 are effective promoters for the reaction, CaCO3 (entries 7–9) and CaCl2 (entry 26) are much less reactive, and Ca(OTf)2 (entry 20) does not show any catalytic effects for the reaction.

Among the combinations we tested, the formulation of CaI2/BTP in DMSO (Table 1, entry 10) obviously outcompetes the other combinations, which gave rise to 87% of conversion within a short time reaction period of 2 h. The promotion effect of using anhydrous propylene carbonate (PC) is not so obvious in the present study (entries 3, 5, and 14). Dimethylformamide (DMF) (entry 25) is a slightly better solvent than PC, but the reactivity is still low. This might be due to the strong chelation effects of BTP that significantly occupy the coordination sites of the calcium ions, warding off the solvation effects of PC. The coordination of BTP with the calcium ion will be discussed in the latter section.

Since MDEAPS containing zwitterion (entries 2 and 3) does not show improvement of the reactivity against MDEA. We therefore tentatively propose that the ionic strength of the local environment around the catalytic site is less significant.

Dissociation of iodide anion from CaI2 has been proposed to be a crucial step for the reaction; release of nucleophilic iodide may help to promote epoxide ring opening followed by carbonate formation and intramolecular cyclization to give the cyclic carbonate product. Due to the strong electrostatic interactions between Ca2+ and I–, dissociation of CaI2 will only be favorable in polar solvents. To enhance the tendency of dissociation, Ca(I3)2 was prepared by the addition of 2 equiv of I2 (entries 12–17 and 23); I3– was expected to be a softer nucleophile that would be liberated much easier in comparison with the iodide anion. Inevitably, a larger size would allow the dispersion of negative charge over I3–, hence lowering the nucleophilicity. Interestingly, the combination of Ca(I3)2/MDEA (entries 12 and 13) shows high reactivity than CaI2/MDEA (entries 5 and 6) either in DMSO or in PC. However, by replacing MDEA with BTP as the ligand, CaI2/BTP (entry 10) shows higher reactivity than Ca(I3)2/BTP (entry 15). Metal iodide such as CuI with strong complexation properties shows poorer activity, indicating that the presence of free nucleophilic iodide may be significant for promoting the cyclic carbonate formation (entry 19). In addition, phosphine-based ligands THPP and THMP (entries 22–24) do show reasonable catalytic activity for the reaction; epoxide can be completely converted to the corresponding cyclic carbonate.

The complexation of CaI2/BTP in solution was further evidenced by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 1). In the absence of CaI2, BTP shows a multiplet at δ = 1.440, which is assigned to the central methylene protons. On increment of the fraction of CaI2, the methylene signal of BTP exhibits gradually downfield shifts to δ = 1.495. The 1:1 binding stoichiometry was estimated according to the Job plot (Figures S1 and S2 and Table S1, SI).

Figure 1.

Variation of the proton chemical shifts of the mixture of CaI2 and BTP in the Job plot experiments. The total molar concentration of CaI2/BTP was held constant at 0.167 M (CaI2 + BTP (0.1 mmol) in DMSO-d6 (0.6 mL)). The CaI2/BTP equivalent ratios were (a) 0:10, (b) 3:7, (c) 6:4, and (d) 9:1.

Proton NMR titration experiments were also performed to evaluate the binding constant (Ka) between BTP and Ca2+ cation (Figures S3 and S4 and Tables S2 and S3, SI). Using the nonlinear curve fitting analysis for the chemical shift variation,53,54Ka of 12 600 ± 1900 M–1 was estimated. This indicates the robust connectivity between the calcium cation and the BTP ligand.

Attempts of resolving the stoichiometry and the structure of the CaI2/BTP complex by crystallographic analysis were performed under various conditions. Transparent orthorhombic single crystals were finally obtained by vapor diffusion of CH2Cl2 into a solution of CaI2 and BTP, with a molar ratio of 1.1:1.0 in DMF at room temperature under neutral conditions. The molecular structure of the calcium complex in the crystal is shown in Figure 2. The coordination number of calcium was found to be eight, bound by four hydroxy groups and two nitrogen atoms on BTP and one water molecule. The last vacancy is occupied by the hydroxy group from another BTP molecule. The charge is balanced by two chloride anions that surprises us. We tentatively attribute the source of the chloride ions through halide exchange between CH2Cl2 and iodide anion (Figure S5, SI). The bond distance of Ca–N was in the range of 2.549(7)–2.611(9), and that of Ca–O was in the range of 2.383(6)–2.504(8).

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of the Ca2+/BTP complex in the crystal. Displacement ellipsoids correspond to 50% probability.

To optimize the practicability of the CaI2/BTP catalyst, we have fine-tuned the formulation to maximize the activity of the system. The highest activity was obtained when an additional equivalent of BTP was added. Further addition of BTP would hamper the reactivity. This is probably due to the CO2 scrubbing effects; while the first equivalent of BTP was consumed for the CaI2/BTP complex formation, additional amounts of BTP might help to absorb CO2, increasing the effective CO2 contents in the solution. However, the presence of high dosage of BTP may lead to the second complexation with the CaI2/BTP catalyst, retarding the Lewis acidity of CaI2/BTP and hence inhibiting the reactivity of the system (Table S4, SI).

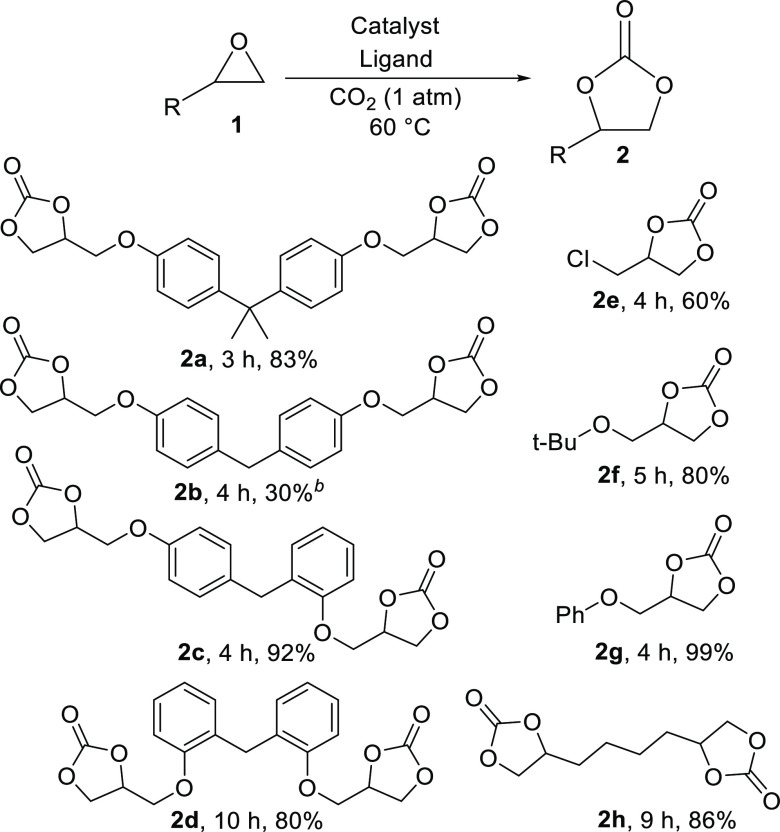

The CaI2/BTP (1:2) protocol was subsequently applied to various terminal mono-/di-epoxide substrates for cyclic carbonate preparation (Scheme 4). All glycidyl derivatives have been fully and smoothly converted in the presence of this catalyst system. The synthesis of 2a was achieved in a good isolated yield of 83%. Bisphenol F diglycidyl ether (BFDGE) can also be used to give 2b–2d. The commercially available BFDGE contains a mixture of (para, para), (para, ortho), and (ortho, ortho) regioisomers. Pure (para, ortho) and (ortho, ortho) regioisomers can be purified by liquid chromatography (Figures S6–S8, SI) and used as the starting materials in the studies. The isolated yields of 2c and 2d were 92 and 80%, respectively. The (para, para) isomer cannot be fully separated from the (para, ortho) isomer. Therefore, a mixture of (para, para) and (para, ortho) isomers (64:36) was used to give a mixture of 2b and 2c. Bis(cyclic carbonate) 2b (30%) could then be collected by recrystallization from a CH2Cl2 and EtOAc solution. This procedure can also be applied for monoglycidyl epoxides to give 2e–2g (60–99%) and for 1,7-octadiene diepoxide to give 2h (86%). The relatively low yield of 2e may be due to iodochloro exchange side reaction that consumes the nucleophilic iodide and hence hampers the catalytic power of the system.

Scheme 4. Substrate Scope for CO2 Fixation to Various Epoxides.

Reactions were performed respectively in the presence of CaI2 (5 mol %) and BTP (10 mol %) as the catalyst for mono-epoxides and CaI2 (10 mol %) and BTP (20 mol %) for di-epoxides in anhydrous DMSO (5 M). Completed reaction time is attached. Isolated yields are given.

Recrystallized from the mixture of 2b and 2c.

To test the reactivity and recycling of the CaI2/BTP catalyst, we chose 1g as a model for investigation. Considering the tradeoff between efficiency and material saving, we reduced the amount of BTP to 5 mol % from the normal 10 mol % (the fastest recipe) conditions. In these studies, CaI2/BTP (5 mol %) in DMSO (5 M) was adopted at 60 °C, and the reaction time was fixed at 6 h. When the reaction was completed, DMSO was distilled under reduced pressure. The residue containing 2g was taken up by small amounts of CH2Cl2 and decanted. The insoluble catalyst left was reused for the next run (Table S5, SI). The percentage conversion was then detected by 1H NMR spectroscopy, and the isolated yield was in the parentheses in Figure 3. Notably, the performance of the catalyst reactivity remained >50% conversion up to the sixth run. The rate constant indicated the degradation of reactivity after the third run (Figure S9 and Table S6, SI). Accordingly, a longer reaction time was required to complete the conversion (Table S7, SI). Overall, the CaI2/BTP catalyst showed great potentials for industrial applications with reusability and recyclability.

Figure 3.

Reactivity test of the CaI2/BTP catalyst system.

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated that CaI2/BTP would form a one-to-one complex that shows high activity and reusability for cyclic carbonates formation through CO2 fixation to terminal epoxides. Besides, in the class of the Lewis acid catalyst system, the behavior of the CaI2/BTP system was basically proposed as the following three-step mechanisms.55 First, the epoxide group is coordinated to the vacant coordination site of the Lewis acidic calcium cation, while the additional hydrogen-bonding interaction resulting from vicinal hydroxy groups is also involved. These coordinations activate the ring opening of the epoxide followed by the nucleophilic attack of the iodide anion on the less substituted carbon. Second, the resulting alcoholate anion will attack the electrophilic carbon of CO2 to form a carbonate intermediate. Finally, intramolecular ring closure by carbonate backbiting proceeds to afford the five-membered cyclic carbonate product and regenerate the nucleophilic iodide anion and the Lewis acid calcium catalyst.

The present protocol provides a cheap and novel catalytic system for cyclic carbonate synthesis with remarkably high efficiency, recyclability, and reusability. In regard to the considerable attention of the non-isocyanate polyurethane (NIPU) process in the industrial field,30,56−58 syntheses of bis(cyclic carbonate)s are crucial, which serve as critical reactants in the preparation. Our experiment demonstrates an attractive synthesis route in this regard.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

Analytical-grade N,N-dimethyl-formamide (DMF), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), dichloro-methane (DCM), ethyl acetate (EA), n-hexane, and propylene carbonate (PC) were used as received without further purification. The following catalysts, ligands, and epoxide substrates including calcium iodide (Alfa Aesar, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.); tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphine (Acros Organics); calcium triflate, N1,N3-dibenzylpropane-1,3-diamine, 2,2-bis(hydroxymethyl)-2,2′,2″-nitrilotriethanol, and 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane (AK Scientific, Inc.); N-methyldiethanolamine (Merck & Co., Inc.); tris(hydroxypropyl)phosphine (Strem Chemicals, Inc.); diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA), diglycidyl ether of bisphenol F (DGEBF), and tert-butyl glycidyl ether (Combi-Blocks, Inc.); 1,2-butylene oxide, glycidyl phenyl ether, and 1,7-octadiene diepoxide (Tokyo Chemical Industry UK Ltd.); and carbon dioxide (99.995%) were used as received. NMR spectroscopy was completed by a Bruker AVANCE 400 MHz and a Varian 400 MHz MERCURY PLUS A spectrometer. Mass spectra were recorded with a Bruker micrOTOF-QII and a JEOL JMS-700 spectrometer. X-ray diffraction crystallography was collected on a Bruker D8 VENTURE.

Synthesis of MDEAPS59,60

A solution of 1,3-propanesultone (2.37 g, 19.4 mmol) and N-methyldiethanolamine (2.25 g, 18.9 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (10.0 mL, 1.0 M) was heated at reflux under argon for 48 h. After the reaction was completed, the solid product was washed with DCM and dried under reduced pressure to provide MDEAPS (3.78 g, 15.7 mmol, 83%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ = 2.24 (q, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 2.97 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.21 (s, 3H), 3.61 (m, 6H), 4.05 (m, 4H).

Synthesis of DTBPDA61

A mixture of tert-butylamine (10.97 g, 150 mmol) and 1,3-dibromopropane, (6.06 g, 30 mmol) in distilled water (1.21 mL) was heated at reflux overnight. After the reaction was completed, a white solid precipitated from the solution. The residue liquid was removed in vacuo. Saturated K2CO3(aq) was then added to neutralize the mixture. The mixture turned out to be a turbid solution. The product was extracted with CHCl3 three times. The organic extracts were combined and dried over anhydrous MgSO4(s) and concentrated under reduced pressure to give DTBPDA as shiny white flakes (3.8 g, 20.4 mmol, 68% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.10 (s, 18H), 1.65 (quin, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.64 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 4H).

General Procedures for the Optimization Table

Diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA) 1a was chosen as the model compound for the optimization of CO2 fixation experiments (Table 1). DGEBA (0.34 g, 1.0 mmol), calcium catalyst (0.1 mmol, 10 mol %), and ligand (0.1 mmol, 10 mol %) in anhydrous DMSO (0.2 mL) (5.0 M relative to 1a) was heated at 60 °C under CO2 (using a CO2 balloon). Reactions were monitored by 1H NMR in CDCl3. The percentage conversions at 2, 4, 6, and 24 h were determined, respectively.

Experimental Procedure for Terminal Mono-Epoxide (EPM)

Mono-epoxide (1.0 equiv), CaI2 (0.05 equiv, 5 mol %), and BTP (0.1 equiv, 10 mol %) were placed in a two-neck round-bottom flask. The mixture was charged with a CO2 balloon three times before anhydrous DMSO was added (5.0 M relative to the epoxide). The solution was then heated at 60 °C. The reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography and/or by 1H NMR in CDCl3. After the reaction completed, DMSO was removed by vacuum distillation. The mixture was then dissolved in DCM and washed with sodium thiosulfate solution three times. The solution was concentrated by rotary evaporation. The crude mixture was purified by liquid column chromatography on silica gel to provide the corresponding substrate product.

Experimental Procedure for Terminal Di-Epoxide (EPD)

Di-epoxide (1.0 equiv), CaI2 (0.1 equiv, 10 mol %), and BTP (0.2 equiv, 20 mol %) were placed in a two-neck round-bottom flask. The mixture was charged with a CO2 balloon three times before anhydrous DMSO was added (5.0 M relative to the epoxide). The solution was then heated at 60 °C. The reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography and/or by 1H NMR in CDCl3. After the reaction was completed, DMSO was removed by vacuum distillation. The mixture was then dissolved in DCM and washed with sodium thiosulfate solution three times. The solution was concentrated by rotary evaporation. The crude mixture was purified by liquid column chromatography on silica gel to provide the corresponding substrate product.

Variation of the Proton Chemical Shifts (Job Plot Experiment)

Mixtures of CaI2/BTP in different equivalent ratios (0:10, 1:9, 2:8, 3:7, 4:6, 5:5, 6:4, 7:3, 8:2, and 9:1) were placed in a vial, respectively, while the total mol of the mixture was 0.1 mmol. DMSO-d6 (0.6 mL) was added to get a transparent solution and then transferred to NMR tubes. The total molar concentration of CaI2/BTP was held constant at 0.167 M (CaI2 + BTP (0.1 mmol)) in DMSO-d6 (0.6 mL). In each case, chemical shift variations of central methylene protons of BTP were monitored by 1H NMR, and the data were analyzed by the Job plot method, a plot of Δδ × [BTP] (Δδ means the chemical shifts of the central methylene protons of BTP after complexation) versus mole fraction of the CaI2. The stoichiometry is detected from the x-coordinate with the maximum y-value, for which x = 0.5. In this case, the stoichiometry of binding is 1:1 (Figures S1 and S2 and Table S1, SI).

1H NMR Titration

Determination of the binding constants for the CaI2/BTP complex was carried out through the 1H NMR titration technique in DMSO-d6. Stock solutions of BTP in DMSO-d6 (2.0 mM) and CaI2 in DMSO-d6 (10.0 mM) were prepared in a vial, respectively. In all aliquots of the BTP solution, the CaI2 solution (10.0 mM) was dropped in with different equivalents. Afterward, blank DMSO-d6 was added to keep [BTP] constant (1.25 mM). The 1H NMR spectrum was detected after each addition. The determination of the specific signal was the same as in the Job plot experiment. The association constants were determined by nonlinear curve fitting analysis (Figures S3 and S4 and Tables S2 and S3, SI).53,54

Synthesis of the Ca2+/BTP Complex

In the inner vial was added a solution of CaI2 (0.323 g, 1.1 mmol) and BTP (0.282 g, 1.0 mmol) in DMF (2.0 mL). In the outer vial (1.0 mL) was added CH2Cl2 as the vapor diffusion solvent. The outer vial was then sealed so that CH2Cl2 would slowly diffuse into the inner vial from the outer one at room temperature. Within 10 days, transparent orthorhombic crystals gradually formed. The chloride ion in the crystal originated from the halo-exchange reaction between CH2Cl2 and the iodide ion. Formation of CH2ICl (δ = 4.955) was evidenced by the 1H NMR spectrum in CDCl3, explaining the unexpected chloride counterions in the crystal lattice (Figure S5, SI).62

Separation of Isomers of Diglycidyl Ether of Bisphenol F (BFDGE)63

Commercially available diglycidyl ether of bisphenol F (BFDGE) (Combi-Blocks) contains a mixture of (para, para), (para, ortho), and (ortho, ortho) regioisomers. The regioisomers can be partly isolated by liquid column chromatography with EA/hexane (1:8) as the eluent. Pure (para, ortho)-BFDGE (poBFDGE) 1c and (ortho, ortho)-BFDGE (ooBFDGE) 1d can therefore be obtained. The (para, para)-BFDGE (ppBFDGE) 1b is unable to be fully separated from (para, ortho)-1c. Consequently, we used a mixture of 1b and 1c (64:36) as the starting materials directly in the study (Figures S6–S8, SI).

Synthesis for Substrate Scope Products

Compounds 2a–2d and 2h were prepared according to the EPD protocol. Compounds 2e–2g were prepared according to the EPM protocol.

4,4′-(((Propane-2,2-diylbis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(methylene))bis(1,3-dioxol-an-2-one) (2a)

1a (340 mg, 1.0 mmol), CaI2 (29.4 mg, 0.1 mmol, 10 mol %), and BTP (56.4 mg, 0.2 mmol, 20 mol %) in anhydrous DMSO (0.2 mL, 5.0 M relative to 1a) were reacted at 60 °C under a CO2 atmosphere for 3 h. The crude mixture obtained from the reaction was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (DCM/EA 6:1) to give 2a as a white solid (355.2 mg, 0.83 mmol, 83% yield, mp 169 °C). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.63 (s, 6H), 4.12 (dd, J = 10.6 Hz, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (dd, J = 10.6 Hz, 4.3 Hz, 2H), 4.51 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.60 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.98–5.03 (m, 2H), 6.97 (dd, J = 133.7 Hz, 8.7 Hz, 8H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 30.9, 41.8, 66.2, 67.0, 74.1, 114.1, 127.9, 144.4, 154.6, 155.7 ppm. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C23H25O8 (M + H)+ 429.1544, found 429.1527.

4,4′-(((Methylenebis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(methylene))bis(1,3-dioxolan-2-one) (2b)

A mixture of 1b and 1c (64:36) (312 mg, 1.0 mmol), CaI2 (29.4 mg, 0.1 mmol, 10 mol %), and BTP (56.4 mg, 0.2 mmol, 20 mol %) in anhydrous DMSO (0.2 mL, 5.0 M relative to total mol of the mixture) was reacted at 60 °C under a CO2 atmosphere for 4 h. The crude mixture obtained from the reaction was first prepurified by column chromatography on silica gel (DCM/EA 25:1), followed by recrystallization from a DCM/EA solution (10:1) to give 2b as an essentially pure white solid (76 mg, 0.19 mmol, 30% yield to 1b, mp 148 °C). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.87 (s, 2H), 4.10 (dd, J = 10.6 Hz, 3.7 Hz, 2H), 4.20 (dd, J = 10.7 Hz, 4.3 Hz, 2H), 4.52 (dd, J = 8.5 Hz, 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.60 (dd, J = 9.2 Hz, 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.98–5.03 (m, 2H), 6.96 (dd, J = 105.1 Hz, 8.7 Hz, 8H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 40.1, 66.2, 67.0, 74.1, 114.7, 130.0, 134.9, 154.6, 156.2 ppm. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H21O8 (M + H)+ 401.1231, found 401.1241.

4-((2-(4-((2-(Oxo-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)methoxy)benzyl)phen-oxy)methyl)-1,3-dioxolan-2-one) (2c)

1c (312 mg, 1.0 mmol), CaI2 (29.4 mg, 0.1 mmol, 10 mol %), and BTP (56.4 mg, 0.2 mmol, 20 mol %) in anhydrous DMSO (0.2 mL, 5.0 M relative to 1c) were reacted at 60 °C under a CO2 atmosphere for 4 h. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (DCM/EA 25:1) to afford 2c as a colorless liquid (368 mg, 0.92 mmol, 92% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.84–3.94 (m, 2H), 4.00–4.09 (m, 2H), 4.16–4.26 (m, 3H), 4.43–4.59 (m, 3H), 4.91–4.99 (m, 2H), 6.78–6.83 (m, 3H), 6.96 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (td, J = 7.8 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 35.3, 65.8, 66.1, 66.60, 66.63, 67.0, 74.1, 74.3, 111.2, 114.5, 114.6, 121.7, 127.7, 129.6, 129.80, 129.87, 131.0, 134.1, 154.66, 154.70, 155.4, 156.1 ppm. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H21O8 (M + H)+ 401.1231, found 401.1233.

4,4′-(((Methylenebis(2,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(methyle-ne))bis(1,3-dioxolan-2-one) (2d)

1d (312 mg, 1.0 mmol), CaI2 (29.4 mg, 0.1 mmol, 10 mol %), and BTP (56.4 mg, 0.2 mmol, 20 mol %) in anhydrous DMSO (0.2 mL, 5.0 M relative to 1d) were heated at 60 °C under an atmosphere of CO2 for 10 h. The crude product obtained from the reaction was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (DCM/EA 25:1) to provide 2d as a white solid (320 mg, 0.8 mmol, 80% yield, mp 71 °C). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.71–4.32 (m, 8H), 4.36–4.48 (m, 2H), 4.93–4.99 (m, 2H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.89–6.97 (m, 4H), 7.18–7.22 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 30.0, 30.1, 65.8, 66.0, 66.2, 66.9, 74.3, 74.4, 110.7, 110.0, 121.4, 121.5, 127.4, 128.9, 129.0, 130.1, 130.3, 154.7, 154.9, 155.4, 155.5 ppm. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H21O8 (M + H)+ 401.1231, found 401.1240.

4-(Chloromethyl)-1,3-dioxolan-2-one (2e)

1e (1.18 g, 12.8 mmol), CaI2 (187.4 mg, 0.64 mmol, 5 mol %), and BTP (359.7 mg, 12.8 mmol, 10 mol %) in DMSO (2.56 mL, 5.0 M relative to 1e) under a CO2 atmosphere was heated at 60 °C for 4 h. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexane/EA 6:1) to provide 2e as a colorless liquid (1.05 g, 7.7 mmol, 60% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.71–3.79 (m, 2H), 4.41 (dd, J = 8.9 Hz, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (dd, J = 9.3 Hz, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.92–4.98 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 43.5, 67.0, 74.2, 154.0 ppm. HRMS (FAB) m/z calcd for C4H6ClO3 (M + H)+ 137.0005, found 137.0007.

4-(tert-Butoxymethyl)-1,3-dioxolan-2-one (2f)

1f (916.6 mg, 7.0 mmol), CaI2 (103.5 mg, 0.35 mmol, 5 mol %), and BTP (198.6 mg, 0.7 mmol, 10 mol %) in anhydrous DMSO (1.4 mL, 5.0 M relative to 1f) were reacted at 60 °C under a CO2 atmosphere for 5 h. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexane/EA 6:1) to afford 2f as a colorless liquid (974 mg, 5.6 mmol, 80% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.18 (s, 9H), 3.51 (dd, J = 10.3 Hz, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 3.60 (dd, J = 10.3 Hz, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 4.36 (dd, J = 8.1 Hz, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.73–4.78 (m, 1H) ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 27.2, 61.2, 66.5, 73.8, 75.1, 155.1 ppm. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C8H14NaO4 (M + Na)+ 197.0784, found 197.0783.

4-(Phenoxymethyl)-1,3-dioxolan-2-one (2g)

1g (332.1 mg, 2.2 mmol), CaI2 (32.6 mg, 0.11 mmol, 5 mol %), and BTP (62.1 mg, 0.22 mmol, 10 mol %) in anhydrous DMSO (0.44 mL, 5.0 M relative to 1g) were reacted at 60 °C under a CO2 atmosphere for 4 h. The crude product obtained from the reaction was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexane/EA 1:1) to give 2g as a white solid (423.4 mg, 2.2 mmol, 99% yield, mp 96 °C). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 4.15 (dd, J = 10.7 Hz, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (dd, J = 10.7 Hz, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 4.61 (dd, J = 9.0 Hz, 8.3 Hz, 1H), 5.00–5.05 (m, 1H), 6.90–6.93 (m, 2H), 7.00–7.03 (m, 1H), 7.29–7.33 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 66.2, 66.9, 74.1, 114.6, 122.0, 129.7, 154.6, 157.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C10H10NaO4 (M + Na)+ 217.0471, found 217.0493.

4,4′-(Butane-1,4-diyl)bis(1,3-dioxolan-2-one) (2h)

1h (994.0 mg, 7.0 mmol), CaI2 (207.0 mg, 0.7 mmol, 10 mol %), and BTP (397.2 mg, 1.4 mmol, 20 mol %) in anhydrous DMSO (1.4 mL, 5.0 M relative to 1h) were reacted at 60 °C under a CO2 atmosphere for 9 h. The crude product obtained from the reaction was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (DCM/EA 1:1) to afford 2h as a colorless liquid (1.37 g, 6.0 mmol, 86% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.45–1.58 (m, 4H), 1.69–1.83 (m, 4H), 4.01 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 8.1 Hz, 2H), 4.53 (dd, J = 8.3 Hz, 8.02 Hz, 2H), 4.67–4.74 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 24.09, 24.13, 33.57, 33.63, 69.22, 69.24, 76.6, 154.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C10H14NaO6 (M + Na)+ 253.0683, found 253.0678.

Detailed Experimental Procedure for the Reactivity Test of the CaI2/BTP Catalyst

1g (332.1 mg, 2.2 mmol), CaI2 (32.6 mg, 0.11 mmol, 5 mol %), and BTP (31.4 mg, 0.11 mmol, 5 mol %) were placed in a centrifuge tube (10.0 mL) in the first run. The mixture was charged with a CO2 balloon three times, added with (0.44 mL) anhydrous DMSO (5.0 M relative to 1g), and then heated to 60 °C. The reaction time was fixed at 6 h. After the reaction was terminated, DMSO was removed by vacuum distillation. DCM was then added to the residue to dissolve the unreacted substrate 1g and the product 2g, and simultaneously, the CaI2/BTP catalyst would precipitate from the solution. 1H NMR was used to monitor the reactivity of the catalyst. Then, we used a centrifuge to reach better recycling of the solid phase. Subsequently, the soluble portion was removed by a dropper and further purified by column chromatography (hexane/EA 1:1). The recovered CaI2/BTP catalyst was dried in vacuo at 70 °C to remove any residual DCM. After finishing each run, another new batch of 1g (change in proportion to the residual weight of CaI2/BTP catalyst) was subjected to the reaction again under the same conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the “Advanced Research Center for Green Materials Science and Technology” from The Featured Area Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (Grant numbers MOE 110L9006) and the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (Grant numbers MOST 110-2622-8-007-015, MOST 110-2113-M-002-009, MOST 110-2634-F-002-043, and MOST 109-2622-E-155-014). The authors acknowledge the mass spectrometry technical research services from NTU Consortia of Key Technologies.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c04086.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lindsey R.Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-atmospheric-carbon-dioxide (accessed May 4, 2020).

- Peters G. P.; Andrew R. M.; Canadell J. G.; Friedlingstein P.; Jackson R. B.; Korsbakken J. I.; Le Quéré C.; Peregon A. Carbon dioxide emissions continue to grow amidst slowly emerging climate policies. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 3–6. 10.1038/s41558-019-0659-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes E. J. C.; Ribeiro A. P. C.; Martins L. M. D. R. S. New Trends in the Conversion of CO2 to Cyclic Carbonates. Catalysts 2020, 10, 479 10.3390/catal10050479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kar S.; Goeppert A.; Prakash G. K. S. Integrated CO2 Capture and Conversion to Formate and Methanol: Connecting Two Threads. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2892–2903. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot-Handford M. E.; Abanades J. C.; Anthony E. J.; Blunt M. J.; Brandani S.; Mac Dowell N.; Fernández J. R.; Ferrari M.-C.; Gross R.; Hallett J. P.; Haszeldine R. S.; Heptonstall P.; Lyngfelt A.; Makuch Z.; Mangano E.; Porter R. T. J.; Pourkashanian M.; Rochelle G. T.; Shah N.; Yao J. G.; Fennell P. S. Carbon capture and storage update. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 130–189. 10.1039/C3EE42350F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.-Z.; He L.-N.; Zhao Y.-N.; Li B.; Yu B. CO2 capture and activation by superbase/polyethylene glycol and its subsequent conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3971. 10.1039/c1ee02156g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alper E.; Yuksel Orhan O. CO2 utilization: Developments in conversion processes. Petroleum 2017, 3, 109–126. 10.1016/j.petlm.2016.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z.; Middleton R.; Viswanathan H.; Fessenden-Rahn J.; Bauman J.; Pawar R.; Lee S.-Y.; McPherson B. An Integrated Framework for Optimizing CO2 Sequestration and Enhanced Oil Recovery. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2014, 1, 49–54. 10.1021/ez4001033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mamoori A.; Krishnamurthy A.; Rownaghi A. A.; Rezaei F. Carbon Capture and Utilization Update. Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 834–849. 10.1002/ente.201600747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schäffner B.; Schäffner F.; Verevkin S. P.; Börner A. Organic Carbonates as Solvents in Synthesis and Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4554–4581. 10.1021/cr900393d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Wu L.; Jackstell R.; Beller M. Using carbon dioxide as a building block in organic synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5933 10.1038/ncomms6933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim X. How to make the most of carbon dioxide. Nature 2015, 526, 628–630. 10.1038/526628a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klankermayer J.; Leitner W. Love at second sight for CO2 and H2 in organic synthesis. Science 2015, 350, 629–630. 10.1126/science.aac7997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokoja M.; Wilhelm M. E.; Anthofer M. H.; Herrmann W. A.; Kühn F. E. Synthesis of Cyclic Carbonates from Epoxides and Carbon Dioxide by Using Organocatalysts. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 2436–2454. 10.1002/cssc.201500161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alassmy Y. A.; Asgar Pour Z.; Pescarmona P. P. Efficient and Easily Reusable Metal-Free Heterogeneous Catalyst Beads for the Conversion of CO2 into Cyclic Carbonates in the Presence of Water as Hydrogen-Bond Donor. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7993–8003. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c02265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das R.; Nagaraja C. M. Highly Efficient Fixation of Carbon Dioxide at RT and Atmospheric Pressure Conditions: Influence of Polar Functionality on Selective Capture and Conversion of CO2. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 9765–9773. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c00987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kember M. R.; Buchard A.; Williams C. K. Catalysts for CO2/epoxide copolymerisation. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 141–163. 10.1039/C0CC02207A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar B.; Llorente M.; Froehlich J.; Dang T.; Sathrum A.; Kubiak C. P. Photochemical and photoelectrochemical reduction of CO2. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2012, 63, 541–569. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klankermayer J.; Wesselbaum S.; Beydoun K.; Leitner W. Selective Catalytic Synthesis Using the Combination of Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen: Catalytic Chess at the Interface of Energy and Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7296–7343. 10.1002/anie.201507458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipple D. T.; Kenis P. J. A. Prospects of CO2 Utilization via Direct Heterogeneous Electrochemical Reduction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 3451–3458. 10.1021/jz1012627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martín C.; Fiorani G.; Kleij A. W. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Preparation of Cyclic Organic Carbonates. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1353–1370. 10.1021/cs5018997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Q.; Liu T.; Wang X.; Shan Y.; Li X.; Ding M.; Shi L.; Zeng H.; Wu Y. One-step multiple-site integration strategy for CO2 capture and conversion into cyclic carbonates under atmospheric and cocatalyst/metal/solvent-free conditions. Appl. Catal., B 2021, 283, 119620 10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K. Nonaqueous Liquid Electrolytes for Lithium-Based Rechargeable Batteries. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4303–4418. 10.1021/cr030203g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster D. C.; Crain A. L. Synthesis and applications of cyclic carbonate functional polymers in thermosetting coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2000, 40, 275–282. 10.1016/S0300-9440(00)00114-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakura T.; Choi J.-C.; Yasuda H. Transformation of Carbon Dioxide. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2365–2387. 10.1021/cr068357u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis A. J.; Picchioni F.; Pescarmona P. P. CO2-fixation into cyclic and polymeric carbonates: principles and applications. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 406–448. 10.1039/C8GC03086C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motokucho S.; Morikawa H. Poly(hydroxyurethane): catalytic applicability for the cyclic carbonate synthesis from epoxides and CO2. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 10678–10681. 10.1039/D0CC04463F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J.; Song Y. H.; Lin Y.; Yin X. Z.; Zuo M.; Zhao Y. H.; Tao X. L.; Zheng Q. Progress in Study of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 6517–6527. 10.1021/ie101995j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve L.; Lamarzelle O.; Rix E.; Grau E.; Cramail H. Isocyanate-Free Routes to Polyurethanes and Poly(hydroxy Urethane)s. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12407–12439. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grignard B.; Thomassin J. M.; Gennen S.; Poussard L.; Bonnaud L.; Raquez J. M.; Dubois P.; Tran M. P.; Park C. B.; Jerome C.; Detrembleur C. CO2-blown microcellular non-isocyanate polyurethane (NIPU) foams: from bio- and CO2-sourced monomers to potentially thermal insulating materials. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 2206–2215. 10.1039/C5GC02723C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R. J.; Zhang X. H.; Du B. Y.; Fan Z. Q.; Qi G. R. Synthesis of bis(cyclic carbonate) and propylene carbonate via a one-pot coupling reaction of CO2, bisepoxide and propylene oxide. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 17307–17313. 10.1039/c3ra42570c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decortes A.; Castilla A. M.; Kleij A. W. Salen-Complex-Mediated Formation of Cyclic Carbonates by Cycloaddition of CO2 to Epoxides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9822–9837. 10.1002/anie.201002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q.-W.; Zhou Z.-H.; He L.-N. Efficient, selective and sustainable catalysis of carbon dioxide. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3707–3728. 10.1039/C7GC00199A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M.; McEachern E. J. Inorganic Carbonates as Nucleophiles for the Asymmetric Synthesis of Vinylglycidols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 8649–8650. 10.1021/ja990783s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock R. L.; Hiyama Y.; McKay J. M.; Nguyen S. T. Co(III) porphyrin/DMAP: an efficient catalyst system for the synthesis of cyclic carbonates from CO2 and epoxides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 2023–2026. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.10.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suleman S.; Younus H. A.; Ahmad N.; Khattak Z. A. K.; Ullah H.; Park J.; Han T.; Yu B.; Verpoort F. Triazole based cobalt catalyst for CO2 insertion into epoxide at ambient pressure. Appl. Catal., A 2020, 591, 117384 10.1016/j.apcata.2019.117384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clements J. H. Reactive Applications of Cyclic Alkylene Carbonates. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 663–674. 10.1021/ie020678i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleij A. W.; North M.; Urakawa A. CO2 Catalysis. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1036–1038. 10.1002/cssc.201700218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbauer J.; Werner T. Poly(ethylene glycol)s as Ligands in Calcium-Catalyzed Cyclic Carbonate Synthesis. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 3025–3029. 10.1002/cssc.201700788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Zhang S.; Song Q.-W.; Liu X.-F.; Ma R.; He L.-N. Cooperative calcium-based catalysis with 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]-undec-7-ene for the cycloaddition of epoxides with CO2 at atmospheric pressure. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 2871–2876. 10.1039/C5GC02761F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbauer J.; Spannenberg A.; Werner T. An in situ formed Ca2+–crown ether complex and its use in CO2-fixation reactions with terminal and internal epoxides. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3769–3779. 10.1039/C7GC01114H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Steinbauer J.; Stefanow V.; Spannenberg A.; Werner T. Polyethers as Complexing Agents in Calcium-Catalyzed Cyclic Carbonate Synthesis. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 13257–13269. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b02502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Longwitz L.; Steinbauer J.; Spannenberg A.; Werner T. Calcium-Based Catalytic System for the Synthesis of Bio-Derived Cyclic Carbonates under Mild Conditions. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 665–672. 10.1021/acscatal.7b03367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T.-X.; Zhang Y.-Y.; Liang J.; Li P.; Hu X.-B.; Wu Y.-T. Multisite activation of epoxides by recyclable CaI2/N-methyldiethanolamine catalyst for CO2 fixation: A facile access to cyclic carbonates under mild conditions. Mol. Catal. 2018, 450, 87–94. 10.1016/j.mcat.2018.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-F.; Song Q.-W.; Zhang S.; He L.-N. Hydrogen bonding-inspired organocatalysts for CO2 fixation with epoxides to cyclic carbonates. Catal. Today 2016, 263, 69–74. 10.1016/j.cattod.2015.08.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comerford J. W.; Ingram I. D. V.; North M.; Wu X. Sustainable metal-based catalysts for the synthesis of cyclic carbonates containing five-membered rings. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 1966–1987. 10.1039/C4GC01719F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eftaiha A. A. F.; Qaroush A. K.; Assaf K. I.; Alsoubani F.; Markus Pehl T.; Troll C.; El-Barghouthi M. I. Bis-tris propane in DMSO as a wet scrubbing agent: carbamic acid as a sequestered CO2 species. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 11941–11947. 10.1039/C7NJ02130E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kortunov P. V.; Siskin M.; Baugh L. S.; Calabro D. C. In Situ Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Mechanistic Studies of Carbon Dioxide Reactions with Liquid Amines in Non-aqueous Systems: Evidence for the Formation of Carbamic Acids and Zwitterionic Species. Energy Fuels 2015, 29, 5940–5966. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b00985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D. Y. C.; Caramanna G.; Maroto-Valer M. M. An overview of current status of carbon dioxide capture and storage technologies. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 426–443. 10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rochelle G. T. Amine Scrubbing for CO2 Capture. Science 2009, 325, 1652. 10.1126/science.1176731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H.; Yeh A. C. Removal of CO2 Greenhouse Gas by Ammonia Scrubbing. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 2490–2493. 10.1021/ie960748j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin B.-W.; Huang K.-C.; Zhang Y.; Zhou L.; Cui Z.; Zhang K.; Zhang X.-Y.; Zhang J.-P. Diverse Structures Based on a Heptanuclear Cobalt Cluster with 0D to 3D Metal-Organic Frameworks: Magnetism and Application in Batteries. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 1962–1970. 10.1002/chem.201705023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordarson P. Determining association constants from titration experiments in supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1305–1323. 10.1039/C0CS00062K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe A. J.; Pfeffer F. M.; Thordarson P. Determining binding constants from 1H NMR titration data using global and local methods: a case study using [n]polynorbornane-based anion hosts. Supramol. Chem. 2012, 24, 585–594. 10.1080/10610278.2012.688972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L.; Lamb K. J.; North M. Recent developments in organocatalysed transformations of epoxides and carbon dioxide into cyclic carbonates. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 77–118. 10.1039/D0GC03465G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon H.; Iqbal S.; Irfan M.; Darda A.; Rawat N. K. A review on the production, properties and applications of non-isocyanate polyurethane: A greener perspective. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 154, 106124 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2020.106124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zareanshahraki F.; Asemani H. R.; Skuza J.; Mannari V. Synthesis of non-isocyanate polyurethanes and their application in radiation-curable aerospace coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 138, 105394 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.105394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blattmann H.; Fleischer M.; Bähr M.; Mülhaupt R. Isocyanate- and Phosgene-Free Routes to Polyfunctional Cyclic Carbonates and Green Polyurethanes by Fixation of Carbon Dioxide. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2014, 35, 1238–1254. 10.1002/marc.201400209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S.-H.; Hong Y.; Sakaguchi H.; Shankarraman V.; Luketich S. K.; D’Amore A.; Wagner W. R. Nonthrombogenic, Biodegradable Elastomeric Polyurethanes with Variable Sulfobetaine Content. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 22796–22806. 10.1021/am506998s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevamurthy M. K.; Lever M.; George P. M.; Morison K. R. Betaine structure and the presence of hydroxyl groups alters the effects on DNA melting temperatures. Biopolymers 2009, 91, 85–94. 10.1002/bip.21085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk M. K.; Gupta S.; Brownie J.; Tajammul S.; Lough A. J. C-H Activation with Elemental Sulfur: Synthesis of Cyclic Thioureas from Formaldehyde Aminals and S8. Chem. - Eur. J. 2001, 7, 4477–4486. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spectral Database for Organic Compounds (SDBS); mass spectrum; SDBS No. 22650; HPM 00-461. https://sdbs.db.aist.go.jp/sdbs/cgi-bin/direct_frame_top.cgi (accessed May 4, 2020).

- Knox S. T.; Wright A.; Cameron C.; Fairclough J. P. A. Well-Defined Networks from DGEBF—The Importance of Regioisomerism in Epoxy Resin Networks. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 6861–6867. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b01441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.