Objective

From the time of its first appearance, the novelty of the SARS-CoV-2, which is responsible for COVID-19, has generated many important questions about its effects on human health.

SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded, enveloped RNA virus that incorporates 3 types of transmembrane proteins (spike [S], envelope, and membrane) and a nucleocapsid (N) structural protein.1 For effective cell entry and consequent infection, the S protein needs to specifically bind to cell-surface receptors such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is thought to be a crucial receptor in this process. The S protein also requires priming by host cell serine proteases such as transmembrane protease serine 2.2

Interestingly, the gene encoding for ACE2 is expressed in the female reproductive organs and cells, including the oocytes, ovaries, placenta, vagina, and the uterus.3 In 2009, the expression of the ACE2 gene in the uterine mucous layer (endometrium) was shown to be higher in epithelial cells (vs stromal cells) and during the secretory phase (vs the proliferative phase) of the menstrual cycle.4 Protein expression analysis reaffirmed the increased expression of ACE2 in the secretory phase (when decidualization, which is essential for achieving pregnancy, occurs); furthermore, the stromal cells showed higher expression of ACE2 during this phase than the epithelial compartments.5

These studies underscore the importance of determining whether there is sufficient ACE2 expression in the human endometrium to allow SARS-CoV-2 infection of this tissue. Because the endometrium is critical for reproduction, viral infection could influence reproductive outcomes and potentially even impact future fertility treatments.

Study Design

The research ethics committee of the Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe approved this study (registration number: 2020-268-1) on May 12, 2020. All the study participants received written and oral information on the study characteristics and consented verbally in the presence of at least 1 witness.

Human tissue samples were obtained by endometrial aspiration (Cornier Pipelle) from 15 women (24–46 years old) symptomatic with COVID-19 and hospitalized at Hospital La Fe (Valencia, Spain).

The samples were freeze-dried at −80°C, and the RNA was extracted (Biobank Facilities, Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe) and analyzed by Bionos Biotech, SL, using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). We first tested the tissues for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA (using the 2019-nCoV CDC RUO kit, targeting 2 conserved regions of the SARS-CoV-2 N gene, N1 and N2; IDT reference 10006713; IDT Corporation, Newark, NJ) and then analyzed the expression of the ACE2 receptor (using a predesigned ACE2 assay; IDT reference Hs.PT.58.27645939) using the human ribonuclease P or MRP subunit P30 (RPP30) as a housekeeping gene.

Finally, the ACE2 expression in the endometrium was compared with its expression in the nasopharyngeal epithelial samples [(n=5) from Bionos Biotech, SL] known to be positive for viral infection. The fold-change in the ACE2 expression was calculated from 3 independent technical replicates with respect to the housekeeping gene RPP30. For statistical significance, the one-tailed t test was applied to log2−ΔΔCT.

Results

We enrolled 15 women (mean age=35.80 years, standard deviation=7.49) in different phases of the menstrual cycle, with a mean of 5 days (standard deviation=4.44) between the confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 (positive nasopharyngeal RT-PCR; data not available) and the collection of endometrial biopsies (Table ).

Table.

Patient characteristics

| Patient | Age (y) | Menstrual cycle phase | Onset of symptoms | Main symptoms | Treatment | Days from COVID-19 diagnosis to EB collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | Proliferative | 1 d before +PCR | Cough, dyspnea, pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol, methylprednisolone, metoclopramide, omeprazole | 9 |

| 2 | 25 | Proliferative | 4 d before +PCR | General discomfort, pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol, methylprednisolone, omeprazole | 2 |

| 3 | 37 | Proliferative | 5 d before +PCR | Pneumonia, hypoxemia | Metoclopramide, enoxaparine, paracetamol, levothyroxine, omeprazole, methylprednisolone, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 10 |

| 4 | 36 | Early secretory | 4 d before +PCR | Fever, dyspnea, arthralgia, bilateral pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol, methylprednisolone, omeprazole, enalapril | 5 |

| 5 | 44 | Early secretory | 6 d before +PCR | Cough, fever anosmia, cephalea, pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, dexamethasone | 4 |

| 6 | 40 | Early secretory | 2 d before +PCR | Bilateral pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol | 1 |

| 7 | 46 | Late secretory | 2 d before +PCR | Cough, fever, pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, dexamethasone, remdesivir, levofloxacin | 5 |

| 8 | 24 | Late secretory | 2 d before +PCR | Dyspnea, pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol, methylprednisolone | 3 |

| 9 | 44 | Late secretory | 4 d before +PCR | Pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, paracetamol, methylprednisolone, bemiparin | 17 |

| 10 | 39 | Late secretory | 4 d before +PCR | Bilateral pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol, methylprednisolone, codeine, metoclopramide, remdesivir | 5 |

| 11 | 28 | Late secretory | 3 d before +PCR | Pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol | 0 |

| 12 | 32 | Late secretory | 4 d before +PCR | Bilateral pneumonia | Azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol, Acetylcysteine, lorazepam |

1 |

| 13 | 40 | Late secretory | 2 d before +PCR | Nasal congestion, cephalea, bilateral pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, dexamethasone, enoxaparine, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | 7 |

| 14 | 41 | Amenorrhea | 3 d before +PCR | Bilateral pneumonia | Enoxaparine, paracetamol, dexamethasone, omeprazole, loperamide, ceftiroden | 5 |

| 15 | 24 | Amenorrhea | Same day as +PCR | Bilateral pneumonia | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparine, paracetamol | 1 |

The age, phase of menstrual cycle, treatment, and the main COVID-19 symptoms are indicated. The timings of symptom onset and endometrial biopsy collection are presented relative to the day of COVID-19 diagnosis confirmed by positive RT-PCR of a nasopharyngeal sample. These 15 patients followed the following inclusion criteria to enroll in the study: women aged 18–48 years with a positive result for SARS-CoV-2 infection indicated by RT-PCR of nasopharyngeal swabs, hospitalization for COVID-19 in Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe, and voluntary willingness to participate in this study; patients with known infertility (ovulation disorder, severe endometriosis, Asherman syndrome, luteal phase deficiency, or fallopian tube obstruction), those using a intrauterine contraceptive device, and those with severe COVID-19 or any other disorder or condition that, in the point of view of the gynecologist, could be a risk for the patient, were excluded from the study.

EB, endometrial biopsy; RT-PCR, real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Miguel-Gómez. SARS-CoV-2 absence in the endometrium: preliminary research. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022.

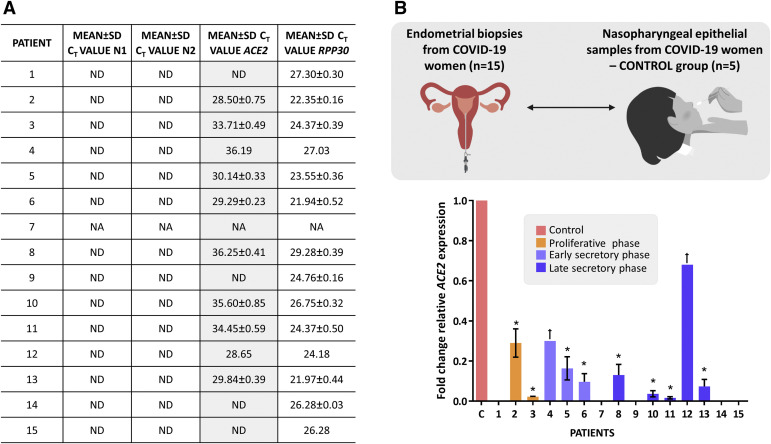

All endometrial samples (except for patient 7 because of insufficient total RNA available) tested negative for the virus (neither the N1 nor the N2 gene was detected) (Figure , A). ACE2 expression was detected in 10 of 14 endometrial samples (excluding patient 7) (Figure, A).

Figure.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction detection of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 expression in the endometrial tissue of SARS-CoV-2–positive patients

A,Table showing the mean and SD of the CT values for SARS-CoV-2 and the ACE2 and RPP30 genes. When the housekeeping gene RPP30 was not detected, the test was considered invalid (NA). B, Graphical representation of the fold-change in ACE2 expression from all endometrial samples when compared with the average expression levels in a control group that included 5 nasopharyngeal epithelial samples derived from SARS-CoV-2–positive patients (women aged between 27 and 48 years; samples from Bionos Biotech, SL), assessed under identical conditions. The fold-change in ACE2 expression was calculated from 3 independent technical replicates with respect to the housekeeping gene RPP30. For statistical significance, a 1-tailed t test was applied on log2−ΔΔCT. The error bars represent the confidence interval. The asterisk represents P≤.0001, dagger represents significance not determined because of insufficient technical replicates. Images created with www.BioRender.com.

CT, cycle threshold; NA, not available; ND, not detected; SD, standard deviation.

Miguel-Gómez. SARS-CoV-2 absence in the endometrium: preliminary research. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022.

The comparison of the ACE2 endometrial expression values to those detected in the SARS-CoV-2-positive nasopharyngeal epithelial samples (control group) confirmed the receptor's low-level expression in the endometrium, and this difference was statistically significant in 8 samples (Figure, B).

Conclusion

Little is known about the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the endometrium, and to the best of our knowledge, no study has assessed this tissue from patients with COVID-19. Our findings indicate that despite the presence of the gene for the receptor ACE2 (proposed to be the key for SARS-CoV-2 cell entry)2 in the endometrium, its messenger RNA (mRNA) expression is insufficient to allow viral infection (none of the analyzed endometrial biopsies revealed the presence of viral mRNA). Previous findings in studies of the human endometrium indicated differential ACE2 expression across the menstrual cycle and in different endometrial cell types.4 , 5 In agreement with these reports, we could appreciate the lower levels of ACE2 expression in the proliferative vs secretory phase (with a notable trend of high expression in the early secretory endometrium). In line with this, an in silico study indicated that the endometrium is likely safe from SARS-CoV-2 infection on the basis of a lack of several key molecular effectors, including ACE2 and TMRPSS2.6 These results align with another recently published in silico study that describes the apparent low risk of infection of the endometrium because of the low percentage of cells expressing ACE2.7 Interestingly, the percentage of cells coexpressing ACE2 and TMRPSS2 was even lower during the window of implantation (secretory phase).7 Together with our pilot results, these findings indicate that the human endometrium seems safe (negative diagnostic test results) from the entry of the virus, potentially because of the low expression of the ACE2 receptor in this tissue. The significantly higher expression of ACE2 that we detected in COVID-19–positive nasopharyngeal epithelial samples reinforces this conclusion. However, the virus-free milieu suggested by in silico studies and corroborated in vivo in the present study would likely not inhibit the alteration of the endometrium because of the systemic changes provoked by COVID-19. Nevertheless, together with further studies in the field, these pilot results could help manage female fertility and reproduction in patients wishing to conceive during this pandemic.

However, we note several limitations. As the samples were not easy to collect or process, our population size was small. In addition, because of health measures and the infectious condition of the patients, we collected biopsies only from symptomatic hospitalized patients (excluding asymptomatic women). We encourage in-depth research into the possible impact of the virus on the endometrium, which could have implications in the reproductive field.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere thanks to the Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe Biobank; they would also especially like to thank Raquel Amigo, MSc and all the care staff of the hospital for their assistance in obtaining endometrial biopsies.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

This work was supported by a Ferring COVID-19 Investigational Grant in Reproductive Medicine and Maternal Health and grant CPI19/00149 from the Carlos III Health Institute to I.C.

References

- 1.Ke Z., Oton J., Qu K., et al. Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on intact virions. Nature. 2020;588:498–502. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2665-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jing Y., Run-Qian L., Hao-Ran W., et al. Potential influence of COVID-19/ACE2 on the female reproductive system. Mol Hum Reprod. 2020;26:367–373. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaaa030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaz-Silva J., Carneiro M.M., Ferreira M.C., et al. The vasoactive peptide angiotensin-(1-7), its receptor Mas and the angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 are expressed in the human endometrium. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:247–256. doi: 10.1177/1933719108327593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chadchan S., Popli P., Maurya V., Kommagani R. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, is required for human endometrial stromal cell decidualization. Biol Reprod. 2021;104:336–343. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioaa211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henarejos-Castillo I., Sebastian-Leon P., Devesa-Peiro A., Pellicer A., Diaz-Gimeno P. SARS-CoV-2 infection risk assessment in the endometrium: viral infection-related gene expression across the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilella F., Wang W., Moreno I., Roson B., Quake S.R., Simon C. Single-cell RNA sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 cell entry factors in the preconceptional human endometrium. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:2709–2719. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]