Abstract

Objectives

To measure and explain financial toxicity (FT) of cancer in Italy, where a public healthcare system exists and patients with cancer are not expected (or only marginally) to pay out-of-pocket for healthcare.

Setting

Ten clinical oncological centres, distributed across Italian macroregions (North, Centre, South and Islands), including hospitals, university hospitals and national research institutes.

Participants

From 8 October 2019 to 11 December 2019, 184 patients, aged 18 or more, who were receiving or had received within the previous 3 months active anticancer treatment were enrolled, 108 (59%) females and 76 (41%) males.

Intervention

A 30-item prefinal questionnaire, previously developed within the qualitative tasks of the project, was administered, either electronically (n=115) or by paper sheet (n=69).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

According to the protocol and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research methodology, the final questionnaire was developed by mean of explanatory factor analysis and tested for reliability, internal consistency (Cronbach’s α test and item-total correlation) and stability of measurements over time (test–retest reliability by intraclass correlation coefficient and weighted Cohen’s kappa coefficient).

Results

After exploratory factor analysis, a score measuring FT (FT score) was identified, made by seven items dealing with outcomes of FT. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the FT score was 0.87 and the item-total correlation coefficients ranged from 0.53 to 0.74. Further, nine single items representing possible determinants of FT were also retained in the final instrument. Test–retest analysis revealed a good internal validity of the FT score and of the 16 items retained in the final questionnaire.

Conclusions

The Patient-Reported Outcome for Fighting FInancial Toxicity (PROFFIT) instrument consists of 16 items and is the first reported instrument to assess FT of cancer developed in a country with a fully public healthcare system.

Trial registration number

Keywords: health economics, oncology, qualitative research, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Patient-Reported Outcome for Fighting FInancial Toxicity (PROFFIT) was developed as a reaction to the finding that financial problems affect the outcome of patients with cancer in Italy, notwithstanding the Italian healthcare system is based on universal coverage and patients do not pay to access cancer treatment.

No tool for measuring and understanding financial toxicity of cancer had been ever produced in the context of a public healthcare system with universal coverage.

The development of PROFFIT was done according to a widely accepted methodology to produce patient-reported outcome measures.

Correlation of PROFFIT with known anchors (quality of life tools, performance status) and the responsiveness of the instrument over the course of the disease are being studied.

PROFFIT might be of interest for other countries where a public healthcare system exists.

Introduction

Financial toxicity (FT) following cancer diagnosis and treatment is an increasingly recognised problem worldwide. While initial reports came from the USA, recent data suggest its importance in many other countries with different healthcare systems, like, for example Japan, Nepal, Canada and Italy.1–7 In 2016, we reported financial difficulties among Italian patients with cancer enrolled in clinical trials, and their association with worse quality of life (QoL) and overall survival.5 Using individual data from 16 randomised trials, we found that patients reporting some degree of financial burden at baseline had a higher chance of worsening global QoL response after treatment, and that patients, who developed FT during treatment, had a statistically significant shorter survival.5

Therefore, in 2018, we started the multicentre Patient-Reported Outcome for Fighting FInancial Toxicity of cancer (PROFFIT) project to develop a tool for measuring and understanding FT of cancer that would be sensitive to dimensions of a universal healthcare system. The PROFFIT protocol and the early qualitative findings of the project were reported elsewhere.8 9 We herein report the quantitative analysis of the 30 items resulting from the early phases of the project and the final questionnaire.

Methods

Overall, the project was performed according to International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) guidelines.10 11

Patient sample and data acquisition

To be included patients had to fulfil the following enrolment criteria: (1) adult patients (>18 years), (2) histologically or cytologically confirmed diagnosis of any type of solid cancer or haematological malignancy, (3) medical treatment (chemotherapy, target agents, immunotherapy, hormonal treatment, radiotherapy or combinations of such therapies) ongoing or terminated within the previous 3 months. The questionnaires could be administered either as paper document or as a tablet digital version, according to centre choice. Written informed consent was required. The minimum sample size was calculated to assess the test–retest reliability. With an acceptable level of intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) equal to 0.70 and an expected ICC of 0.80, a one-sided alfa 0.05, 80% power, at least 118 patients had to be enrolled.

Instrument

The first two tasks of the PROFFIT project, concept elicitation and item generation, have been previously described.9 Briefly, as for concept elicitation, an extensive list of topics related to FT was derived from literature review, expert survey and focus groups. Ten FT domains (medical care, domestic economy, emotion, family, job, health workers, welfare state, free time and transportation) were described by 156 topics that reduced to 55 items after correction for redundancy, and to 30 items after importance analysis. These 30 items were proposed to further 45 patients within cognitive interviews testing comprehensibility, recall, judgement and response; the 30 items refined after cognitive interviews represented the prefinal instrument (online supplemental appendix table S1).

bmjopen-2021-049128supp001.pdf (423.6KB, pdf)

Two groups of items were identified by the study steering committee: (1) outcome items (n=10), that is, indicators, that reflect the level of the supposed latent FT and that do not alter or influence the latent construct they measure, and (2) determinant items (n=20), that is, causal indicators, that are considered to affect FT and that may change the latent variable.12 Separate analyses were performed in the outcome and determinant groups.

Statistical analysis

To reduce possible redundancy, the between-item correlation matrix was preliminarily estimated by pairwise Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (rs), because of the ordinal nature of items; cut-off was set equal to 0.65, and for each pair of items with rs>0.65 the item with the greater score in the previously published importance analysis was retained.9 Because information was missing for the five items related to job in 68/184 (37%) patients, who declared themselves retired or jobless (ie, househusbands, housewives or individuals in search of employment), correlation coefficients were estimated separately for job items (excluding patients with missing data on job items) and for all the other items (within the full population).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to discover the presence of multi-item scales and the distribution of the items consistent with the theoretical framework of FT.13 To extract factors we used the principal axis factoring (PAF) analysis with varimax and promax rotation, and Kaiser normalisation. To determine the number of scale factors, we relied on the Kaiser criterion to select factors with eigenvalue >1, the Scree test to depict the percentage of total variance explained by the factors extracted, and the interpretability of the factor solution. PAF assumptions were assessed by Bartlett’s sphericity test and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy.14

Due to missing data in job items, EFA was performed both in the sample of patients with complete valid information (hereby defined as ‘restricted sample’), and in the whole sample (hereby defined as ‘full sample’), by imputing, for each subject, the missing values with the average score of the other answered items. A more detailed description of the whole analysis path is reported in online supplemental appendix.

The face validity of the resulting scale was examined, both in terms of the scale global meaning and in terms of the appropriateness of each individual item to that scale. Internal consistency, that is, within-scale between-items correlations, was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha correlation coefficient, assuming as acceptable a value >0.70. Relationships between each individual item xi and the total score of the scale to which they were assumed to belong were assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient with correction for overlap, that is, by omitting xi from the total score. To evaluate stability of measurements over time, the questionnaire was to be administered again after one week and the test–retest reliability was assessed by ICC and weighted Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. We considered a minimally acceptable level of reliability equal to 0.70 and an expected ICC of 0.80.

A preliminary construct validity analysis, as requested from reviewers, was performed evaluating the association of the FT with baseline demographic and clinical variables; however, findings are only suggestive, and need to be independently validated in a larger independent sample, whose recruitment is ongoing, as stated in the protocol.8

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the study sample and their mean scores answers. The data met all the necessary assumptions for this factor analysis. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V.25.0 (SPSS) and with Stata V.14 (Stata).

English translation

To allow international comprehension of the final PROFFIT questionnaire, an English translation was done according to methodology proposed by Wild et al.15 First, a translation committee was established including five members of the steering committee (FP, SR, CG, MDM and FE), two English mother-tongue translators and two Italian mother-tongue translators. Second, the two English translators independently translated the tool into English producing two forward translations (T1 and T2) that were collected and subsequently discussed in a meeting where the agreement on the English version was achieved. Third, the two Italian translators (unaware of the original Italian version) independently back-translated the English version into Italian; their translations were collected and discussed in a meeting including the whole translation committee. During such meeting the final English translation was generated and approved by the steering committee. It is important to underline that the English translation has to be considered just to allow comprehension by non-Italian readers because it has not been cross-culturally adapted and validated within a population of English native patients.

Patient and public involvement

The project was informed by patients’ thanks to the involvement of patients and representatives of patients’ associations in the Steering Committee that oversaw all the phases of the project, including protocol definition, qualitative analysis (previously reported elsewhere) producing the prefinal questionnaire, and final analyses producing the final questionnaire (reported here); they are coauthor of this manuscript and of the previous manuscripts dealing with this project (LDC, FDL, EI and FT). They will also contribute in dissemination of the results of the project.

Results

From 8 October 2019 to 11 December 2019, 185 patients were enrolled at 10 participating centres; one patient was excluded because the baseline questionnaire was missing due to a technical problem with web connection of the tablet application. Questionnaires were administered as paper document in 4 centres (69 patients) and as digital tablet application in 6 centres (115 patients). Job-related items had a 37% rate of missing responses; all the remaining items were answered in 100% of the cases, leading to the full sample of 184 patients and the restricted sample of 116 patients.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of both samples are shown in table 1. In the full sample, median age was 59 years (range 29–83) and participants were predominantly female. More than half of the patients had a high level of schooling (high school or degree), and around 70% were married. In terms of clinical characteristics, the great majority of patients had a previous surgery for cancer, and the most common treatment was chemotherapy. As expected, in the restricted sample, patients were younger, with a higher level of education and more frequently actively working.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating patients

| Full sample N=184 |

Restricted sample N=116 |

|

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 108 (58,7) | 63 (54,3) |

| Male | 76 (41,3) | 53 (45,7) |

| Age, median (range) | 59 (29–82) | 55 (29–74) |

| Age category, n (%) | ||

| ≤60 | 94 (51,1) | 72 (62,1) |

| >60 | 90 (48,9) | 44 (37,9) |

| Macroregion of the participating institution, n (%) | ||

| North | 71 (38,6) | 46 (39,7) |

| Centre | 15 (8,2) | 9 (7,8) |

| South | 71 (38,6) | 43 (37,1) |

| Islands | 27 (14,7) | 18 (15,5) |

| Education level, n (%) | ||

| Elementary school | 23 (12,5) | 8 (6,9) |

| Middle school | 57 (31,0) | 33 (28,4) |

| High school/degree | 104 (56,5) | 75 (64,7) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married | 132 (71,7) | 82 (70,7) |

| Other | 52 (28,3) | 34 (29,3) |

| With dependent family members, n (%) | ||

| No | 107 (58,2) | 60 (51,7) |

| Yes | 77 (41,8) | 56 (48,3) |

| Family members with cancer or chronic disease, n (%) | ||

| No | 82 (44,6) | 52 (44,8) |

| Yes | 102 (55,4) | 64 (55,2) |

| Working status, n (%) | ||

| Working | 84 (45,7) | 82 (70,7) |

| Not working | 100 (54,3) | 34 (29,3) |

| Distance (km) from the hospital, median (range) | 20 (1–430) | 25 (1–286) |

| Time (years) from initial diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| ≤1 | 80 (43,5) | 54 (46,6) |

| 1–5 | 65 (35,3) | 38 (32,8) |

| ≥5 | 39 (21,2) | 24 (20,7) |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | ||

| Surgery | 129 (70,1) | 81 (69,8) |

| Chemotherapy | 157 (85,3) | 94 (81,0) |

| Target-based agents | 55 (29,9) | 37 (31,9) |

| Immunotherapy | 38 (20,7) | 28 (24,1) |

| Hormonal therapy | 31 (16,8) | 18 (15,5) |

| Radiotherapy | 43 (23,4) | 28 (24,1) |

| Last/ongoing treatment, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 135 (73,4) | 79 (68,1) |

| Target-based agents | 18 (9,8) | 13 (11,2) |

| Immunotherapy | 25 (13,6) | 19 (16,4) |

| Hormonal therapy | 5 (2,7) | 4 (3,4) |

| Radiotherapy | 1 (0,5) | 1 (0,9) |

| Primary tumour site, n (%) | ||

| Breast | 59 (32,1) | 36 (31,0) |

| Lower gastrointestinal tract | 51 (27,7) | 24 (20,7) |

| Genitourinary | 34 (18,5) | 27 (23,3) |

| Thoracic | 18 (9,8) | 13 (11,2) |

| Upper astrointestinal tract | 13 (7,1) | 10 (8,6) |

| Other | 9 (4,9) | 6 (5,2) |

At the preliminary between-item correlation analysis, six items were excluded (three job-related) because rs was greater than 0.65, leading to 9 outcome and 15 determinant items for subsequent analyses (online supplemental appendix table S2a, b).

EFA on the nine-outcome correlation matrix was first performed in the restricted sample of 116 subjects with complete information, because of the presence of the job item Q99. PAF assumptions on the nine outcome items were met with very good parameters (KMO=0.82 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, p<0.001). Two items were excluded because of low communality (see online supplemental appendix for details). With seven outcome items, two initial eigenvalues were >1 and explained 66% of the total variance; both could be interpreted as expression of financial burden, the first one being more correlated with items mirroring an actual severe burden while the second one appeared more correlated with worries about the future. This interpretation was reinforced when oblique Promax rotation was applied (see online supplemental appendix).

In the full sample (KMO=0.87 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, p<0.001), with missing imputation for the job-related item, similar findings were observed. The same seven items were retained, but only one factor >1 was extracted that explained 57% of the total variance; factor loadings and communalities are reported in online supplemental appendix (EFA on outcome paragraph).

Thus, the PROFFIT FT-score includes seven outcome items. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the PROFFIT FT-score was 0.85 in the restricted sample and 0.87 in the full sample, indicating that the correlation between the items and the score is consistently reliable. Correlations between each single item of the FT-score and the total score (after removal of the single item), ranged from 0.37 to 0.73 in the restricted sample, and from 0.53 to 0.74 in the full sample (online supplemental appendix table S3).

Similarly, assumptions on the 15 determinants items were met with satisfactory parameters (KMO=0.68 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, p<0.001). PAF on the determinant items eliminated six items because of low communality and showed that the other nine items were only mildly related, without a clear definition of any factor, hence they were retained as single items (see online supplemental appendix—EFA on determinants paragraph—for more details).

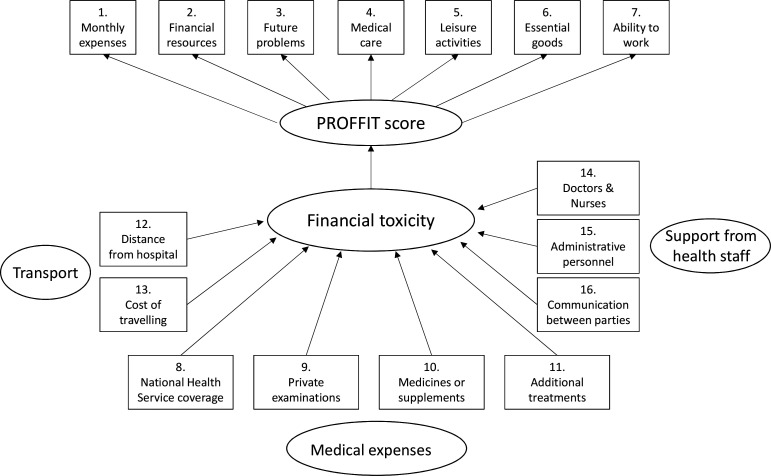

Therefore, the final PROFFIT instrument includes the FT-score (consisting of seven items) and nine single items assessing possible determinants of FT. In table 2, both the Italian items and the English translation are reported. The postulated causal structure for PROFFIT is reported in figure 1.

Table 2.

Final PROFFIT instrument

| Item type and no | Italian version | English translation (for comprehension only) |

| Outcome items (FT-score) | ||

| 1. | Sono in grado di sostenere le mie spese mensili senza difficoltà (ad esempio per affitto, elettricità, telefono…) | I can afford my monthly expenses without difficulty (eg, rent, electricity, phone…) |

| 2. | La mia malattia ha ridotto le mie disponibilità economiche | My illness has reduced my financial resources |

| 3. | Sono preoccupato dei problemi economici che potrei avere in futuro a causa della malattia | I am concerned by the economic problems I may have in the future due to my illness |

| 4. | La mia condizione economica incide sulle mie possibilità di curarmi | My economic situation affects the possibility of receiving medical care |

| 5. | Ho ridotto le spese per attività ricreative come vacanze, ristoranti o spettacoli per affrontare le spese della mia malattia | I have reduced my spending on leisure activities such as holidays, restaurants or entertainment in order to cope with expenses related to my illness |

| 6. | Ho ridotto le spese per acquisti essenziali (ad esempio il cibo) per affrontare le spese per la mia malattia | I have reduced spending on essential goods (eg, food) in order to cope with expenses related to my illness |

| 7. | Sono preoccupata/o di non riuscire a lavorare a causa della mia malattia | I am worried that I will not be able to work due to my illness |

| Determinant items (single items) | ||

| 8. | Il Servizio Sanitario Nazionale copre tutti i costi sanitari associati alla mia malattia | The National Health Service covers all health costs related to my illness |

| 9. | Ho sostenuto spese per una o più visite private per la mia malattia | I have paid for one or more private medical examinations for my illness |

| 10. | Ho sostenuto spese per farmaci supplementari o integratori per la mia malattia | I have paid for additional medicines or supplements related to my illness |

| 11. | Devo sostenere spese per cure integrative a mio carico (es. fisioterapia, psicoterapia, cure odontoiatriche) | I have to pay for additional treatment myself (eg, physiotherapy, psychotherapy, dental care) |

| 12. | Il centro di cura è lontano dalla mia abitazione | The treatment centre is a long way from where I live |

| 13. | Ho dovuto sostenere rilevanti costi di trasporto per curarmi | I have spent a considerable amount of money on travel for treatment |

| 14. | Il personale sanitario (cioè medici, infermieri, etc) ha agevolato il percorso di cura | Medical staff (ie, doctors, nurses, etc) have been helpful throughout my medical care |

| 15. | Il personale ospedaliero amministrativo (cioè centro di prenotazione, segreterie, etc) ha agevolato il percorso di cura | Staff in hospital administration (ie, for booking appointments, secretaries, etc) have been helpful throughout my medical care |

| 16. | C’è stata comunicazione tra i medici e le strutture sanitarie che mi seguono | Medical staff and medical facilities I attended communicated with each other |

FT, financial toxicity; PROFFIT, Patient-Reported Outcome for Fighting FInancial Toxicity.

Figure 1.

Postulated causal structure for PROFFIT tool. PROFIT, Patient-Reported Outcome for Fighting FInancial Toxicity.

We excluded from the test–retest analysis all questionnaires administered more than 35 days (n=52) after the first ones because of the possibility that more than one cycle of treatment could had been given during the interval. However, due to cyclic structure of ongoing anticancer treatment, most retest questionnaires were actually administered later than the planned 1-week interval from the first assessment. Within 132 cases of the full sample, median time between test and retest was 21 days; ICC and Cohen’s weighted K coefficients of the FT-score were excellent, being equal to 0.81 and 0.82, respectively. Considering each singular item, all ICCs and K coefficients were good, ranging from 0.52 to 0.79 (online supplemental appendix table S4).

Associations of FT score with baseline characteristics of patients are reported in online supplemental appendix table S5. Significant and relevant differences were found in accordance with Italian macro-region, age, education level and family disease burden.

Discussion

FT has been initially described in the USA as a factor negatively affecting patients with cancer during their journey, in several ways.7 Particularly, both QoL and survival have been reported to be worse among patients facing with financial hardships and bankruptcy.16 17 This might be not surprising given that the US health system prevalently requires out of pocket copayment of medical expenses, and that the cost of cancer treatment has been steadily increasing.18

On the contrary, we were surprised when we earlier observed that financial problems (measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire) were associated with worse QoL and shorter survival also among Italian patients with cancer, who actually live in a country with a 74% public coverage of healthcare system.5 19 However, the extreme simplicity of the single-item #28 of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire did not allow further understanding of the determinants of the phenomenon. Therefore, we decided to develop an instrument to describe FT more thoroughly and to explore potential determinants, within the Italian public health system, where the dynamics should be different as compared with a prevalently private health system like the US one.20 21

The Italian healthcare system was shaped, since 1978, as a National Health Service (NHS) model, where the State is the most important financer, via general tax levies.22 The NHS model prevails in Northern and Southern European Countries, whereas Central Europe is mostly characterised by social insurance-based model, funded by payroll taxes. Regardless the model, the European healthcare systems are characterised by a high proportion of healthcare expenditure covered by compulsory public programmes, ranging from 66% in Spain to 78% in UK, compared with 49% in the USA.19 The Italian NHS is decentralised, since regions are responsible for healthcare budget.22 In Europe decentralisation does not depend on the healthcare system model: both NHS-shaped models (eg, UK vs Spain) and social-insurance models (eg, France vs Germany) are centralised versus decentralised, respectively. Italy shows a lower intermediation of private expenditure than the other major European countries: in 2018 out-of-pocket expenditure accounted for 89% of private expenditure in Italy, compared with 40%, 55% and 75% in Germany, France and UK/Spain, respectively.23 The mean yearly amount of out-of-pocket expenses for patients with cancer was estimated in the same year to be €1841 within a survey conducted by the Federazione italiana delle Associazioni di Volontariato in Oncologia.24

Here, we report the PROFFIT questionnaire that, to the best of our knowledge, is the first instrument fully published from a European country, and that is candidate to be cross-culturally adapted and validated in other countries with health systems similar to the Italian public health system. The PROFFIT questionnaire includes the FT-score (consisting of seven items) and nine single items assessing possible determinants of FT. In principle, the seven-item FT score could be immediately generalisable to every system, once validity has been confirmed, while the nine-single-item determinants are strictly dependent on the healthcare system. The latter ones, that are lacking in other tools like Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST), were acknowledged by patients in the cognitive interviews and should be the variable part of the questionnaire to be assessed in the various frameworks. In terms of construct validity, the PROFFIT score appears to be sensitive to patients’ differences (eg, Italian macroregions, age, education level and family burden of disease), while, on the contrary, the time from cancer diagnosis has no impact on that score. However, together with other clinical questions, differences will be further validated in a larger independent sample in the ongoing step 4 of the project by using confirmatory analysis.

The need to have a specific instrument to measure FT has been previously addressed in the USA by the investigators who produced and validated the COST instrument.25 26

The methodology applied to develop PROFFIT is similar to that applied for the COST development, as both followed the ISPOR guidelines.10 11 Nevertheless, the content of the two instruments differ, according to the three domains (psychological response, material conditions and coping behaviours) proposed by Altice et al to describe financial hardship.27 Indeed, while 8 of the 11 items of the COST version 1 questionnaire fall into the ‘affect’ theme and the psychological response domain, 11 out of the 16 PROFFIT items pertain to the material conditions domain. This marked difference supports that the sociocultural context and the health and social care systems may significantly affect the causes and the consequences of financial problems of patients with cancer.20 21 Recently, the COST-FACIT V.2 has been developed. In this version, an additional item was added to reflect overall financial well-being (https://wizard.facit.org/index.php?option=com_facit&view=search&searchPerformed=1 accessed 18 August 2021). However, this additional item was not included in the calculation of the summary score in the original validation study25 26 and this makes difficult to make any comparisons with the US context, at the present time.

Therefore, specific instruments should be used within different contexts, and an analysis of differences between social and health systems should be done before choosing which instrument might be more appropriate for measuring FT. An instrument like PROFFIT, including several items related to determinants of FT, may be helpful to identify potential targets for action; and such targets, indeed, might be not immediately identified within a public health system that should cover all the needs of patients with cancer. Namely, items related to transportation costs, to medical expenses not adequately covered by the public health system and the items pertaining to the quality of medical and non-medical staff and the communication among them clearly indicate some roadmaps of intervention that should be addressed within projects of education, organisation and financial support of various compartments of the welfare system.

Around one-third of patients did not respond to items related to job activities. For this reason, we performed correlation analysis separately for job-related items and for all the other items, and approached EFA using both a restricted sample, including only subjects answering all items, and the full sample, involving all subjects, where missing responses were imputed based on responses to the other valid items. We did that, according to the protocol, for both increasing the power of the analysis and as a sensitivity analysis of findings in the restricted sample. We chose to input the average score rather than the minimum score because the latter could be true for retired people (at least in the Italian population), but not for younger people without job. Further, this choice is consistent with the calculus of the score, where the missing items are not considered in the denominator. Accordingly, the restricted sample might be most sensitive to financial distress deriving from job loss or reduction but would not be representative of the real-world cancer patient population due to the selective exclusion of older patients, and generalisability would be reduced. On the contrary, the full sample, that is representative of the general cancer patient population might be less sensitive to relevance of job problems. We will further investigate the impact of job conditions in larger multicentre clinical studies through a more detailed definition of job categories, including all the types of unemployment that led to missing responses.

Notwithstanding a longer than planned interval between test and retest questionnaire administration, that might in principle reduce reproducibility, a good reliability was observed with all the items.

While usually a fixed time window is indicated in patient reported outcomes to define the period of interest, we decided not to use a fixed temporal frame to which refer the response. The decision was prompted by the consideration that in the final PROFFIT questionnaires, some of the items represent patient-reported experiences, rather than pure outcomes, and might derive from the accumulation of problems over the time. This should make the instrument more sensitive for cross-sectional studies, where it is not strictly important to define whether responses refer to a precise time window. Of course, when PROFFIT will be used as a tool within prospective trials comparing different treatment strategies, a fixed time might be indicated. The flexibility proposed by the PROFFIT aims to facilitate its use in healthcare settings alongside routine psycho-oncological assessments for stress and QoL where stress/financial anxiety could represent a new construct to be systematically assessed as recently suggested.28 The PROFFIT will be also able to monitor patients’ social conditions including work and family status, dimensions that seems extremely sensitive to FT.29 30

According to the protocol, larger studies are planned to confirm criterion and construct validity of the PROFFIT instrument, and to assess the responsiveness of the tool12 over the course of the disease and in different types of patients. In the meanwhile, the questionnaire is available for all Investigators wishing to cross-validate it into different languages and countries. No fee will be required for using the questionnaire for purely academic studies, but registration of the protocols will be required and written agreements with the National Cancer Institute of Naples, Italy, will be requested.

In conclusion, FT is a major problem in oncology also within a universal healthcare system, hence the availability of specific and validated instruments is crucial to better understand its causes and its relationship with different aspects of cancer disease. Ultimately, data generated via this newly developed tool will provide insights on how to collaborate in the fight against FT, and hopefully improve the outcomes of cpatients with cancer.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @fperrone62

CG and FP contributed equally.

Contributors: FP obtained funding. SR, JB, CG and FP drafted the manuscript. MDM, FE, VM, LF, DG, LDC, FDL, EI, FT, LG, CJ, CMV and MCP contributed to manuscript writing. MDM, VM, DG, DB, SC, CP, LDM, VZ, AAC, RB, AG and FP contributed to patients’ enrolment. SR, LA, LG, CG and FP performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All Authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version. CG and FP are joint last authors. FP is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: The project is supported by Fondazione AIRC (Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro), a non-profit Italian charity, IG 2017 Id 20402.

Competing interests: SR has received personal fees from CSL-Behring and GlaxoSmithKline Foundation. MDM has received personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Astra Zeneca, Janssen, Astellas, Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda. FE has received personal fees from AbbVie, BMS, Amgen, Orsenix, Takeda and research grant (Institution) from Amgen. VM has received personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb and Italfarmaco; a member of his family is employee in Bayer. CJ has received personal fees from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Gilead, GSK, Ipsen, Janssen-Cilag, Takeda and Sanofi. CMV has received personal fees from from Baxter, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi, Sanofi Genzyme. CP acted as a Speaker and/or Consultant for MSD, BMS, AstraZeneca, Ipsen, Pfizer, Eisai, EUSA, Novartis, Merck, General Electrics and Angelini; furthermore, was an Expert Testimony for Pfizer and EUSA. LDM has received personal fees from Eli Lilly, Roche, MSD, Novartis, Genomic Health, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Daiichi Sankyo, Astra Zeneca, Ipsen, Eisai. VZ has received personal fees from BMS, MSD, Eisai, Italfarmaco, Roche, Astellas Pharma, Servier, Astra Zeneca, MSD, Janssen, Ipsen and research grant (Institution) from Bayer, Roche, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Ipsen, Astellas. RB reports personal fees from Bayer, Astra Zeneca, Sanofi, Novartis, Amgen, Hoffmann La Roche, Pfizer, Janssen Cilag, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck. MCP reports personal fees from Daichii Sankyo, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from MSD, grants from Roche, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, non-financial support from Bayer. FP has received personal fees from Bayer, Ipsen, Astra Zeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Sandoz, Incyte, Celgene, Pierre Fabre, Janssen-Cilag and research grants (Institution) from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Roche, Merck, Pfizer, Incyte, Sanofi, BioClin, Tesaro. All the above disclosures are outside the submitted work. The other Authors have no conflict to disclose.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was initially approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Institute of Naples that acted as coordinating Ethics Committe. Date of first approval is 18 October 2017 and code of approval is 18/17oss. Thereafter, the protocol was approved by Ethics Committee at each participating centre.

References

- 1.Ezeife DA, Morganstein BJ, Lau S, et al. Financial burden among patients with lung cancer in a Publically funded health care system. Clin Lung Cancer 2019;20:231–6. 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honda K, Gyawali B, Ando M, et al. Prospective survey of financial toxicity measured by the comprehensive score for financial toxicity in Japanese patients with cancer. J Glob Oncol 2019;5:1–8. 10.1200/JGO.19.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longo CJ, Fitch MI, Banfield L, et al. Financial toxicity associated with a cancer diagnosis in publicly funded healthcare countries: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:4645–65. 10.1007/s00520-020-05620-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lueckmann SL, Schumann N, Hoffmann L, et al. 'It was a big monetary cut'-A qualitative study on financial toxicity analysing patients' experiences with cancer costs in Germany. Health Soc Care Community 2020;28:771–80. 10.1111/hsc.12907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perrone F, Jommi C, Di Maio M, et al. The association of financial difficulties with clinical outcomes in cancer patients: secondary analysis of 16 academic prospective clinical trials conducted in Italy. Ann Oncol 2016;27:2224–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdw433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poudyal BS, Giri S, Tuladhar S, et al. A survey in Nepalese patients with acute leukaemia: a starting point for defining financial toxicity of cancer care in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Haematol 2020;7:e638–9. 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30258-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: it's time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108. 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [Epub ahead of print: 11 12 2015]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riva S, Bryce J, De Lorenzo F, et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported outcome tool to assess cancer-related financial toxicity in Italy: a protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031485. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riva S, Efficace F, Di Maio M, et al. A qualitative analysis and development of a conceptual model assessing financial toxicity in cancer patients accessing the universal healthcare system. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:3219-3233. 10.1007/s00520-020-05840-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity-establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2-assessing respondent understanding. Value Health 2011;14:978–88. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity-establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1-eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health 2011;14:967–77. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of life: assessment, analysis and interpretation, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychol Assess 1995;7:286–99. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT. Exploratory factor analysis, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (pro) measures: report of the ISPOR Task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005;8:94–104. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1732–40. 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial Insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:980–6. 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramsey SD, Lyman GH, Bangs R. Addressing skyrocketing cancer drug prices comes with tradeoffs: Pick your poison. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:425–6. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armeni PB, Borsoi A.;, L.; Costa F. La spesa sanitaria: composizione ed evoluzione. In: Rapporto Oasi. Milano: Egea, 20202020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perrone F, Di Maio M, Efficace F, et al. Assessing financial toxicity in patients with cancer: moving away from a One-Size-Fits-All approach. J Oncol Pract 2019;15:460–1. 10.1200/JOP.19.00200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotter J, Spencer JC, Wheeler SB. Financial toxicity in advanced and metastatic cancer: Overburdened and Underprepared. J Oncol Pract 2019;15:e300–7. 10.1200/JOP.18.00518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donatini A. The Italian health Care system. In: Tikkanen RO, Mossialos R.;, Djordjevic E.;, et al., eds. The 2020 international profiles of health care systems: a useful resource for interpreting country responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Vecchio MF, Preti L, L.M Rappini R. I consumi privati in sanit. In: Bocconi C, ed. Rapporto Oasi. Milano: Egea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Lorenzo FT, Campo FDel, Iannelli L. Indagine sui costi sociali ed economici del cancro nel 2018 in 11° Rapporto sulla condizione assistenziale dei malati oncologici Oncologia FFIdAdVi; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: the COST measure. Cancer 2014;120:3245–53. 10.1002/cncr.28814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the comprehensive score for financial toxicity (COST). Cancer 2017;123:476–84. 10.1002/cncr.30369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, et al. Financial Hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109. 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [Epub ahead of print: 20 10 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones SMW, Du Y, Panattoni L, et al. Assessing worry about affording healthcare in a general population sample. Front Psychol 2019;10:2622. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirchhoff A, Jones S. Financial toxicity in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: proposed directions for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021;113:948–50. 10.1093/jnci/djab014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu AD, Zheng Z, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship in survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021;113:997–1004. 10.1093/jnci/djab013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-049128supp001.pdf (423.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.