Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate abstinence rates of tobacco treatment programs (TTPs) at National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers (DCCs) and to ascertain the number of NCI-DCCs with online references to TTPs.

Methods:

Literature searches of Pubmed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Scopus were performed from their inception through January 2018 using keywords including cancer patients, cancer survivors, tobacco, smoking, cessation, and program. 4094 articles were identified, 1450 duplicates were removed, 2644 candidate titles and abstracts were screened, and 210 selected full-text articles were independently reviewed by two authors. Three retrospective, single-institution cohort studies describing system-wide TTPs at three NCI-DCCs met inclusion criteria. Secondarily, online website audits of each NCI-DCC were performed to identify institutions with online evidence of a system-wide TTP servicing cancer patients.

Results:

Among 62 NCI-DCCs, only three reported system-wide TTP outcomes. Abstinence rates ranged from 15–47%. Online website audit identified 47 NCI-DCCs maintaining system-wide TTPs. Seventeen TTPs were housed within the cancer center and 30 TTPs were offered by the primary affiliated institution; among the latter group, only 13 TTPs were identifiable via the NCI-DCC webpage.

Conclusions:

Most NCI-DCCs offer tobacco treatment services to cancer patients but very few have reported their results. Increased NCI-DCC TTP outcome publication and online presence are needed.

Keywords: tobacco dependence, tobacco treatment, cancer center, smoking cessation, National Cancer Institute

Introduction

Tobacco use causes eleven types of cancer and accounts for over 30% of cancer deaths in the United States (US) annually.1 Patients who continue to smoke after a cancer diagnosis incur increased morbidity and a higher risk of death compared to cancer patients who quit smoking.1 Despite this, 18% of cancer patients and 27% of tobacco-related cancer patients in the US continue to smoke after diagnosis.2

Smoking cessation interventions are effective. While behavioral therapy or pharmacotherapy alone can significantly improve tobacco cessation rates in non-pregnant adults, combination therapy is the standard of care.3 Based on more limited data in cancer patients, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) recommend all cancer patients receive evidence-based smoking cessation assistance – combined behavioral- and pharmaco-therapy.1

Despite this mandate, tobacco treatment in US cancer patients remains inadequate. Only 39% of oncologists routinely provide tobacco cessation treatment to patients or refer them to a tobacco treatment program (TTP).4,5 Among the 62 National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers (DCCs), the flagship US cancer care institutions, only 62% routinely provide education materials to patients who smoke and only 53% effectively identify patients who use tobacco.6 Over 20% of NCI-DCCs deny having a TTP.6

The NCI aims to improve tobacco treatment of cancer patients. In 2009, it identified 21 barriers to TTP implementation at NCI-DCCs, three of which included: 1) a “lack of recognition of quality programs,” 2) “limited research in tobacco dependence treatment in patients with cancer,” and 3) “limited patient…awareness of the importance of quitting tobacco.”7 In their strategies to address these barriers, the NCI called on NCI-DCCs to: make tobacco dependence treatment part of their core mission, garner data about the effectiveness of tobacco treatment, publish their care models, and “develop outstanding… communications to the public.” This study aims to evaluate progress in these areas by identifying system-wide TTPs at NCI-DCCs via online audit and to describe NCI-DCC TTP abstinence rates via literature review.

Methods

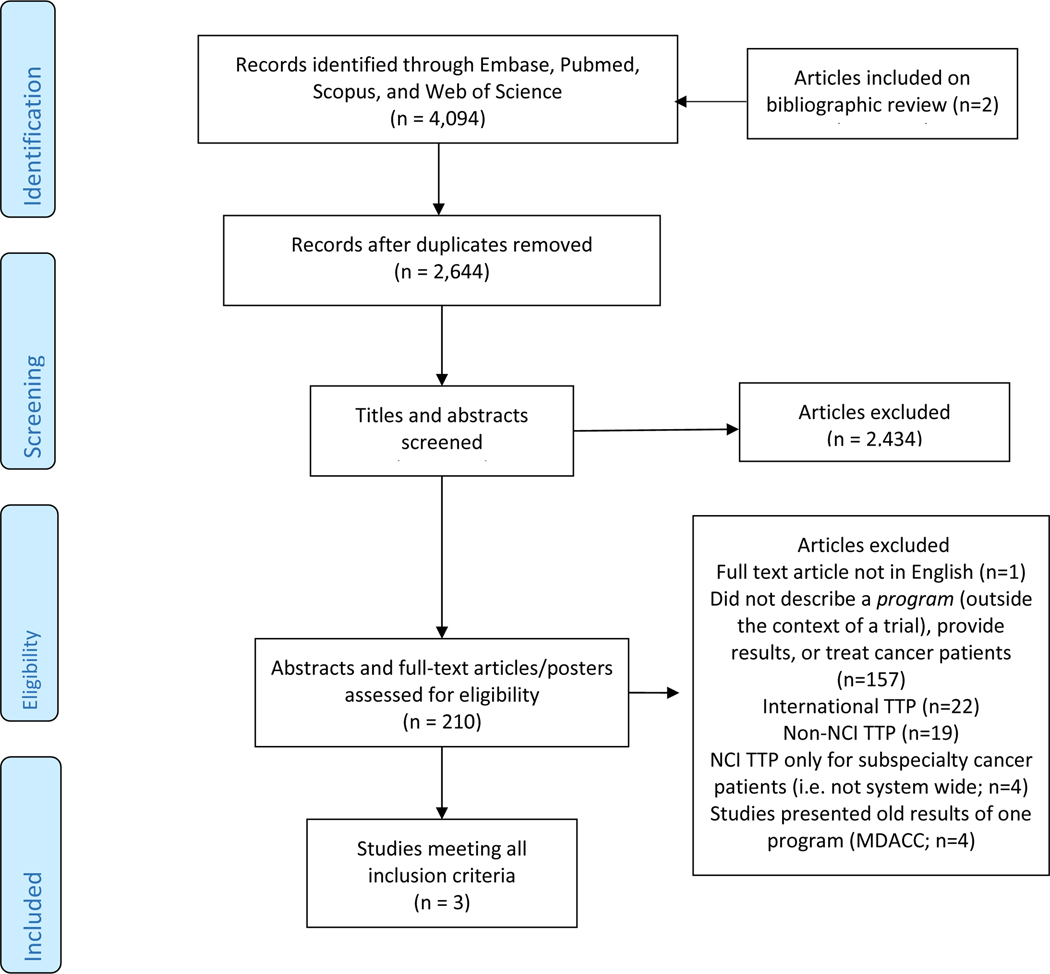

Literature searches of Pubmed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Scopus were performed from their inception through January 31st, 2018 in English-language publications. Using keywords including cancer patients, cancer survivors, tobacco, smoking, cessation, and program, comprehensive search terms were developed (Supplement). 4,094 articles were identified and exported to Endnote8 (Figure 1). 1,450 duplicates were removed. 2,644 candidate titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by two authors (AD, LT). Eligible manuscripts described cancer center-wide TTPs at NCI-DCCs in the US or system-wide TTPs at the primary NCI-DCC affiliated institution. Articles describing TTPs for cancer patients at non-NCI-DCCs in the US, TTPs in international cancer centers, TTPs not reporting patient outcomes, and TTPs restricted to certain cancer populations (i.e. lung cancer patients only) were ineligible. Conversely, programs accessible to all patients, including cancer patients, were deemed “system-wide” TTPs. Given the NCI’s exhortation that NCI-DCCs to make tobacco treatment part of their core mission, only cancer center-wide or system-wide TTPs were included in this study. Included articles were also evaluated for risk of bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for Cohort Studies (Appendix: Table 1).8 Studies excluded after full-text review are listed in Table 2 of the Appendix.

Figure 1: PRISMA Diagram.

NCI: National Cancer Institute

TTP: tobacco treatment program

MDACC: MD Anderson Cancer Center

Online website audits of each NCI-DCC and, if indicated, its primary affiliated institution, were performed from 2/1/2017 to 5/22/2017 by two authors (AD, LT). For the purpose of this review, a TTP was defined as the provision of smoking cessation services beyond: 1) primary care or oncologist referral and 2) provision of online links to external resources or tobacco quitlines not directly affiliated with the institution. Online searches of the primary institution’s webpage and lung cancer screening programs were performed internally and using Google (Menlo Park, CA) when a TTP was not identified via the NCI-DCC website.

Results

Among 62 NCI-DCCs, the majority (n=59) have not published system-wide TTP outcomes. As described in Table 1, only MD Anderson Cancer Center [MDACC, n=4,111], Roswell Park Cancer Institute [RPCI, n=1179] and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [MSKCC, n=782) published system-wide TTP outcomes.9,10,11 According to the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for Cohort Studies tool, the studies exhibited moderate to high risk of biases (Appendix: Table 1).12 The 12-week MDACC program offered various treatment delivery modalities with continuous follow-up to one year. The program’s seven-day point prevalence of tobacco abstinence at nine months after treatment initiation was 38% by intention-to-treat (ITT) and 47% by respondent-only (RO: excluding patients not reached for follow-up).9 The RPCI telephone-based program collected data over a 26-month period; 27% and 32% of all patients reported tobacco cessation according to ITT and RO analyses, respectively.10 A definition of tobacco abstinence and its relation to tobacco treatment initiation or completion was not described in that paper. The MSKCC TTP coordinated pharmacotherapy with up to five sessions of behavioral therapy and stratified their outcome reporting according to e-cigarette use.11 Among e-cigarette users, the seven-day point prevalence abstinence rate for traditional cigarettes at 6–12 months was 14.5% and 44.4% according to ITT and RO analyses, respectively.11 Among patients who did not use e-cigarettes, the seven-day point prevalence abstinence rate was 30% and 43.1% according to ITT and RO analyses, respectively.11

Table 1:

System-wide TTPs at NCI-DCCs with Published Outcomes

| Program | Author | Treatment Program Characteristics | Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | # Patients | Treatment Type (Behavioral Therapy and/or Pharmacotherapy) | Time | Abstinence rate | ||

| MDACC | Karam-Hage9 | 1/2006 to 8/2013 | ITT: 4111 RO: 2779 |

Both | 7-day PP abstinence at 9-months | ITT: 38% RO: 47% |

| RPCI | Reid10 | NR (26-month period) | ITT: 1179 RO: 1045 |

Not reported | Tobacco cessation at most recent follow-up | ITT: 28.7% RO: 32.3% |

| MSKCC | Borderud11 | 1/2012 to 12/2013 | ITT: 781 RO: 414 - E-cigarette use: 285 No e-cigarette use: 789 |

Both | 7-day PP abstinence rate for traditional cigarettes at 6- to 12-months | E-cigarette use ITT: 14.5% RO: 44.4% No e-cigarette use ITT: 30% RO: 43.1% |

ITT: intention-to-treat (included all patients completing an initial visit); MDACC: MD Anderson Cancer Center; MSKCC: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; NR: not reported; RO: respondent-only (included only patients who responded to query about abstinence); RPCI: Roswell Park Cancer Institute

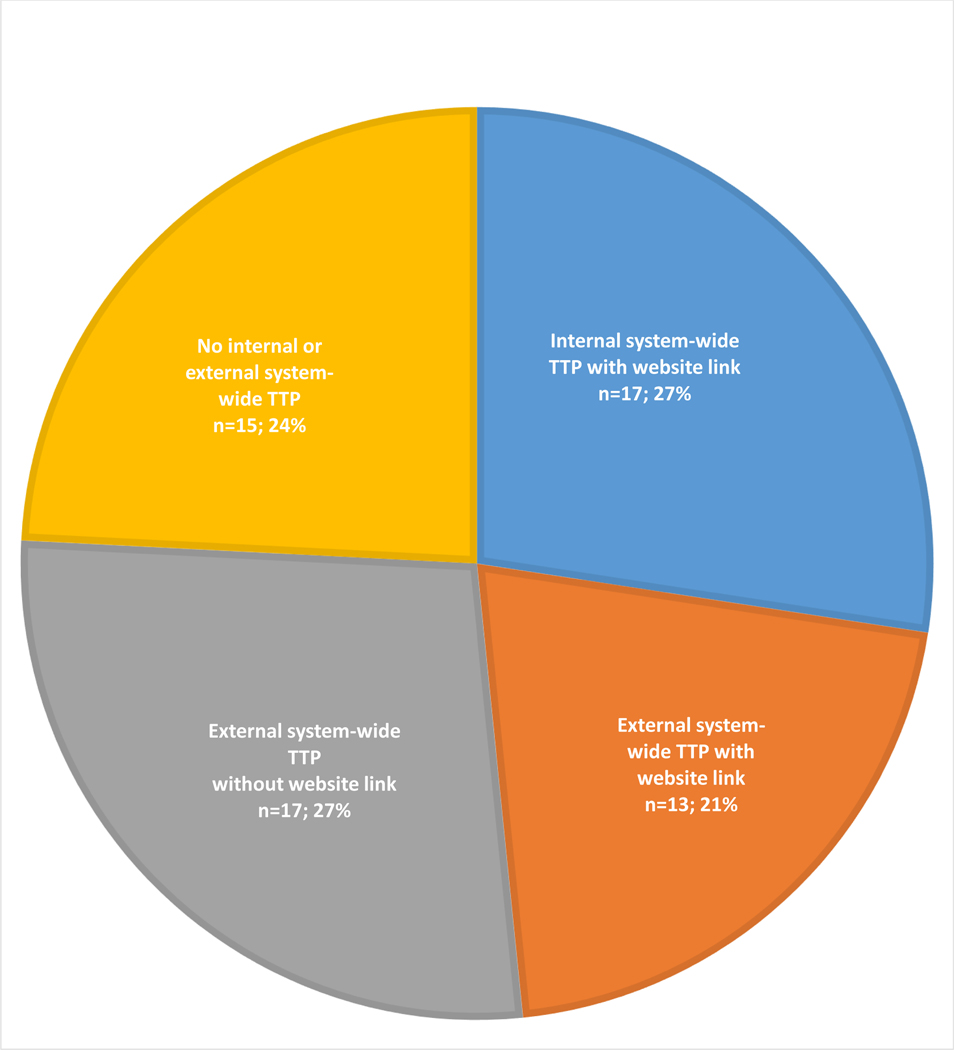

Online audit of 62 NCI-DCC websites and websites of their primary affiliated institutions revealed that 47 NCI-DCCs (79.0%) publicized their system-wide TTPs online (Figure 2). Seventeen NCI-DCCs (27.4%) offered internal TTPs (all of which were identified via the website) and thirty (48.4%) offered external system-wide TTPs via their primary affiliated institutions. Among the latter group (n=30), a link from the NCI-DCC webpage was identified for 13 TTPs and no link was identified for 17 TTPs. Fifteen NCI-DCCs (24.2%) did not exhibit evidence of a system-wide TTPs according to our online audit: three primary affiliate institutions maintained inpatient-only TTPs; four institutions offered TTPs at ancillary sites within the same city; and the remaining eight institutions offered no TTPs.

Figure 2: Online Assessment of Tobacco Treatment Programs at NCI-Designated Cancer Centers.

NCI: National Cancer Institute

TTP: tobacco treatment program

Discussion

Despite a recognized need to publish outcomes of TTPs, only 5% of 62 NCI-DCCs have described system-wide results. Unfortunately, lean reporting in this field is not limited to TTPs. Only a handful of underpowered prospective cohort or randomized controlled tobacco treatment studies in cancer patients have been published. In a recent meta-analysis, pooled mean six-month tobacco abstinence rates were similar for cancer patients receiving an intervention (n=623, 23.8%) and the control-group (n=591, 19.1%; OR 1.31, 95% CI: 0.93–1.84, p=0.12).13 However, among the eight pooled studies, two did not offer pharmacotherapy in the treatment arm, four studies with pharmacotherapy only offered nicotine-replacement therapy, and five restricted eligibility to patients with lung or head and neck cancer.13 In an earlier meta-analysis, six-month abstinence rates were significantly better in patients who received the intervention compared to the control (RR 1.42, 95% CI: 1.05–1.94) after excluding an outlier study without pharmacotherapy.14 The limited results of our review of real-life clinical programs do support intensive intervention. Notwithstanding the high-risk of study bias, nine-month MDACC TTP abstinence rates (38%−47%) double the above pooled six-month control-group abstinence rates (19%). Ultimately, more comprehensive and intensive interventions using standardized abstinence reporting are needed to clarify the efficacy of TTPs in cancer survivors and prioritize this service accordingly.15

Limited TTP outcomes notwithstanding, NCI-DCC TTPs are also poorly publicized online. There is no online evidence of a system-wide TTP at 15 (24.2%) NCI-DCCs, which approximates the findings of a 2013 survey of NCI-DCCs.6 Among the 47 NCI-DCCs with system-wide TTPs, 36% of TTPs could not be identified on the respective NCI-DCC webpage. This inadequate online TTP presence represents a missed opportunity: 1) 84% of Americans are online,16 2) 71% of cancer patients search the Internet for information about cancer daily to several days per week after receiving a cancer diagnosis,17 and 3) in a recent study of 9,110 Canadian cancer patients, 73% were interested in quitting.18 A collective improvement in availability and the promotion of NCI-DCC TTPs is warranted. The NCI has further prioritized this issue by initiating the Cancer Center Cessation Initiative which seeks to augment tobacco cessation treatment capacity and infrastructure at NCI-DCCs.

A limitation of this study is the focus on TTPs in NCI-DCCs in the US alone. Exclusion of international and US non-NCI-DCC TTPs was deliberate but decreased study generalizability.

Conclusion

Current NCI-DCC TTP outcome reporting is inadequate. Given cancer patients’ interest in tobacco cessation and robust use of the internet after cancer diagnosis, improving availability and access to treatment via online TTP advertisement is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: There are no sources of funding to report for any of the authors.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: There are no pertinent financial interests to disclose for any of the authors.

Financial Support or Sources: None

Sponsor: None

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript to disclose for any of the authors.

Bibliography

- 1.Shields PG, Herbst RS, Arenberg D, et al. Smoking Cessation, Version 1.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(11):1430–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Tai E, White A, Davis SP, Fairley TL. Persistent cigarette smoking and other tobacco use after a tobacco-related cancer diagnosis. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):333–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siu AL. Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM, et al. Addressing tobacco use in patients with cancer: a survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(5):258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM, et al. Practice patterns and perceptions of thoracic oncology providers on tobacco use and cessation in cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(5):543–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein AO, Ripley-Moffitt CE, Pathman DE, Patsakham KM. Tobacco use treatment at the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s designated Cancer Centers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan G, Schnoll RA, Alfano CM, et al. National Cancer Institute conference on treating tobacco dependence at cancer centers. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2011;7(3):178–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells G, Shay B. Data extraction for nonrandomised systematic reviews. University of Ottawa, Ottawa. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karam-Hage M, Oughli HA, Rabius V, et al. Tobacco Cessation Treatment Pathways for Patients With Cancer: 10 Years in the Making. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(11):1469–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid ME, Amato KD, Zevon M, et al. Increasing access to tobacco cessation support for cancer patients: Results of an institution-wide screening and referral program in an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(15). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borderud SP, Li Y, Burkhalter JE, Sheffer CE, Ostroff JS. Electronic cigarette use among patients with cancer: Characteristics of electronic cigarette users and their smoking cessation outcomes. Cancer. 2014;120(22):3527–3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McPheeters ML KS, Peterson NB, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science. Vol (Vol. 3: Quality Improvement Interventions To Address Health Disparities). 2012 Aug. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 208.3.) Appendix G, Thresholds for Quality Assessment. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2012: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK107322/. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nayan S, Gupta MK, Strychowsky JE, Sommer DD. Smoking cessation interventions and cessation rates in the oncology population: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(2):200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nayan S, Gupta MK, Sommer DD. Evaluating smoking cessation interventions and cessation rates in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ISRN Oncol. 2011;2011:849023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrin A DM. Americans’ Internet Access: 2000–2015. Internet, Science, Tech 2015; http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/06/26/americans-internet-access-2000-2015/. Accessed 2/1/17.

- 17.van de Poll-Franse LV, van Eenbergen MC. Internet use by cancer survivors: current use and future wishes. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(10):1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sampson L, Papadakos J, Milne V, et al. Preferences for the Provision of Smoking Cessation Education Among Cancer Patients. J Cancer Educ. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.