Abstract

The role of neurotrophins in neuronal plasticity has recently become a strong focus in neuroregeneration research field to elucidate the biological mechanisms by which these molecules modulate synapses, modify the response to injury, and alter the adaptation response. Intriguingly, the prior studies highlight the role of p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) in various injuries and diseases such as central nervous system injuries, Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. More comprehensive elucidation of the mechanisms, and therapies targeting these molecular signaling networks may allow for neuronal tissue regeneration following an injury. Due to a diverse role of the p75NTR in biology, the body of evidence comprising its biological role is diffusely spread out over numerous fields. This review condenses the main evidence of p75NTR for clinical applications and presents new findings from published literature how data mining approach combined with bioinformatic analyses can be utilized to gain new hypotheses in a molecular and network level.

Key Words: bioinformatics, brain injury, data mining, neuron, neurotrophins, p75NTR, plasticity, regeneration

Introduction

Tropomyosin receptor kinases (Trk-family) bind neurotrophins, which are growth factors in the central nervous system. neurotrophins like nerve growth factor, brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotophin-3 and neurotrophin-4 promote neuronal growth, surviving and plasticity (Park and Poo, 2013). They are synthesized from pro-neurotrophins into mature neurotrophins, which both can bind to Trk-receptors. Neurotrophins, and especially pro-neurotrophins, can also bind to p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) (Park and Poo, 2013). Activation of p75NTR leads to the enzyme-mediated cleavage of the receptor: the extra cellular domain of p75NTR is cleaved by the metalloproteinase TNFα-converting enzyme (TACE, also known as ADAM17) and the transmembrane domain by γ-secretase complex (Chao, 2016). As a result, intracellular domain of p75NTR is released. The intracellular domain of p75NTR is then translocated in the nucleus where it regulates a wide range of cellular functions, including neuronal apoptosis, axonal growth and degeneration, myelination, cell proliferation and synaptic plasticity (Park and Poo, 2013; Chao, 2016). Some of these functions are activated by the neurotrophin binding to p75NTR but in others, p75NTR acts as a co-receptor associated with other neurotrophin receptors, for example Trks, sortilin, Lingo-1 and Nogo (Park and Poo, 2013).

p75NTR in Neurological Diseases

Many prior studies highlight the central role neurotrophins and p75NTR play in response to central nervous system injury such as traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage, and ischemic stroke (Ploughman et al., 2009; Meeker and Williams, 2015; Lee et al., 2016). It is shown among others that pharmacological inhibition of p75NTR reduced 20% of the brain lesion volume in experimental TBI model (Sebastiani et al., 2015). Additionally, the pathobiology of p75NTR has notable similarities with the biology of amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as AD patients show increased levels of p75NTR and proBDNF in hippocampal tissue samples (Bai et al., 2008; Fleitas et al., 2018). AD patients also have a greater proBDNF/BDNF ratio in cerebrospinal fluid, which may disrupt the delicate balance between death and survival counter-regulation mechanisms (Fleitas et al., 2018). Interestingly, cleavage of p75NTR seems to be linked to Alzheimer’s disease as well through α-secretase, γ-secretase and TACE enzymes (Chao, 2016). In addition, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients have also greater p75NTR ectodomain concentrations in urine when compared to healthy controls (Shepheard et al., 2014). High concentrations of p75NTR ectodomain have been reported to correlate with the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Shepheard et al., 2014). As a result of these mechanistic studies, therapeutic and clinical interests into neurotrophins concentrate on their ability to regulate the process of neuronal and synaptic regeneration following either acute or chronic brain injury. As such, the role of neurotrophins in neuronal plasticity has recently become a strong focus of research in an attempt to elucidate the biophysiological mechanisms by which these molecules modulate synapses, modify the response to injury, and alter the adaptation response (Meeker and Williams, 2015). Following clear elucidation of these mechanisms, therapies targeting these molecular signaling networks may allow for healthy neuronal tissue regeneration following injury.

Can We See a Big Picture?

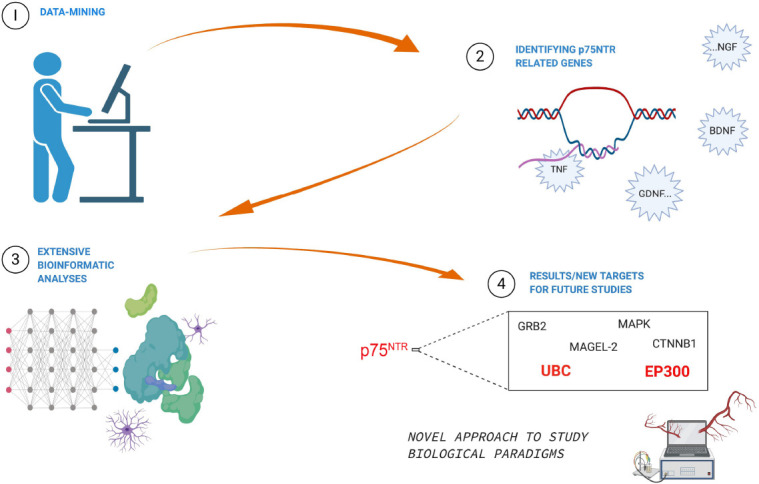

It is clear that p75NTR is involved in various diseases due to its central role in response to injury, and as a result the body of evidence comprising its true biological role is diffusely spread out over numerous fields. A thorough and analytic review that would combine these prior articles and establish connections in one place may yield interesting insights by connecting the dots. There is a possibility to identify new connections, pathways, and mechanisms that were previously not identified because certain elements were only characterized in isolation from other data. Our recent study attempted to solve this specific dilemma regarding incorporating the existing current knowledge by using a large dataset approach that would increase the overall understanding of complex p75NTR functions and molecular interactions (Sajanti et al., 2020). We first identified p75NTR and its related genes using a data mining approach (Figure 1). A total of 2041 peer-reviewed articles related to p75NTR and published in the past 20 years, comprised the large database for further querying. Using this approach, we identified 235 genes associated with p75NTR and its role in neuronal signaling. Furthering our analyses using a machine learning educated linkage gene approach, our research group aimed to identify new gene and protein candidates that may be involved in a network with p75NTR, but have not been widely identified or established as possible targets in the literature regarding response to cellular injury. Additionally, these 235 genes related to p75NTR were also investigated using hierarchical genome-wide pathways. The results from these pathway analyses provide a general overview of the functions of p75NTR in a network with its closely related genes neatly tying together a core summary of what is known about p75NTR in the literature, while also purporting new networks and possible therapeutic targets.

Figure 1.

Illustration of study approach and results.

The PubMed database was queried with specified search terms and subsequently was mined resulting in target genes associated with the p75 neurotrophic receptor (p75NTR). Network analyses were performed using a highly reliable algorithm extracted from multiple human-curated pathways. Network analyses were followed by pathway enrichment analysis with hypergeometric testing. The approach integrated vast amount of research data that was diffusely spread out over numerous fields and identified new targets for future studies. Furthermore, the data mining approach can be applied to other studies as well – it is not restricted to only p75NTR studies.

The primary goal of this study was therefore to shed some light on what the existing data is revealing about the role of p75NTR when considering the literature together, as well as whether there are hidden factors that are not seen until putting the whole puzzle together. The results obtained from genome-wide cluster and pathway analyses validated the current understanding of p75NTR reinforcing his role in various pathways including programmed cell death, immune system modulation, signal transduction, developmental biology, gene expression regulation, and extracellular matrix organization (Lee et al., 2001; Nalbandian and Djakiew, 2006; Schecterson and Bothwell, 2010; Park and Poo, 2013). The most enriched pathways that were identified also validated the roles of previous studies, such as p75NTR being highly expressed in human cancers including melanoma (Nalbandian and Djakiew, 2006; Boiko et al., 2010). Notably, this link of p75NTR to cancer pathophysiology is particularly interesting given the complex interactions that cancer progression has with immune modulation, matrix remodeling, and cellular adaptation (Nalbandian and Djakiew, 2006; Boiko et al., 2010; Park and Poo, 2013). Currently, however, there are no studies suggesting a significant role of p75NTR with regards to immune response modulation in cancer, nor in acute or chronic brain disease, suggesting this area may warrant further investigation. In addition, MAPK1/ERK2 and MAPK3/ERK1 pathways were identified in relation to p75NTR with well documented roles in apoptosis, neuronal repair, and axonal growth (Lad and Neet, 2003). The large existing body of knowledge on MAPK further supports that these significant connections involving p75NTR should be further investigated in relation to these pathways.

Further, we combined the gene network analyses with a focused subnetwork analysis using linkage genes that identified functionally related genes that were not part of the original data-mined p75NTR identified genes. This essentially allows for novel identification of genes that are not apparent from each study separately. For example, GRB2 has previously been shown to act directly downstream of TrkA as a signaling adaptor protein, however, there were no previous links with p75NTR until this analysis was performed (MacDonald et al., 2000). Supporting this novel direct link was the observation that in scrapie-infected rodent brain tissue the protein levels of BDNF, TrkB, phospho-TrkB, GRB2 and p75NTR were all significantly down-regulated (Wang et al., 2016). Considering the degenerative nature of scrapie disease, it is interesting to consider the possible interplay of GRB2 and p75NTR in other neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, although it arises from a different unclear etiology.

Another novel linkage gene identified was UBC, which is the gene for polyubiquitin precursor protein that plays a significant role in proteasome degradation (Caldeira et al., 2014). Conjugation of ubiquitins is well recognized to be highly important for protein degradation and its larger roles in cellular processes such as DNA repair, cell cycle regulation, kinase modification, and the endocytosis system, while dysfunction of this system results in various pathologies. Loss of UBC is associated with the pathophysiological molecular factors of AD via decreased proteasome degradation system, which may be a result of decreased recycling of malfunctioning, damaged, and old proteins (Latina et al., 2018). These connections with p75NTR highlight its possible important role in AD’s pathophysiology (Shen et al., 2019). It is important to note, however, that the role of p75NTR in AD pathophysiology is probably only a model for which p75NTR acts as a central protein signaler in response to various types of cellular damage.

Several other interesting genes such as SRC, CTNNB1, and EP300 were also identified in the same linkage gene network with p75NTR. Inhibition of SRC family kinases has previously been shown to improve cognitive function in rats after intraventricular hemorrhage, suggesting they may play a role in cellular recovery after injury (Liu et al., 2017). As a result, these observations combined with the known functions of p75NTR in neuronal recovery suggest it likely plays a significant role following hemorrhagic insult as another form of pathological damage. Similarly, CTNNB1 encodes a β-catenin protein that increases precursor form of nerve growth factor leading to p75NTR activation ultimately promoting neuronal growth. Examining this relationship in rat models of intracerebral hemorrhage showed that modulation of β-catenin pathway is neuroprotective following a hemorrhagic event (Zhao et al., 2019). The role of p75NTR, however, has not previously been considered in this regard. Our recently published results suggest an association between CTNNB1 and p75NTR thus positing there may be a substantial role for p75NTR in response to hemorrhage.

It is well recognized that p75NTR plays a significant role in neuronal development, and some of the linkage genes identified further shed light on this role. MAGEL2, which belongs to the same melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE) family as NRAGE, was also identified in our analysis. Similar to how NRAGE is involved in the p75NTR mediated programmed cell death, MAGEL2 is linked to neurodevelopmental disorders such as Prader-Willi syndrome and Schaaf-Yang syndrome, thereby suggesting significant importance of MAGEL2 in human neuronal development. Previous animal studies have also shown that mTOR and autophagy pathways are dysregulated in Magel2 null mice models, further highlighting that these dysregulated processes may be the underlying pathological changes that result in altered neuronal development (Crutcher et al., 2019). In our analysis, MAGEL2 was directly linked to transcription factor E2F1, which was directly linked to p75NTR. This suggests a role of necdin-related MAGE proteins in p75NTR functions, which is supported by previous preclinical observations and suggests this may be a fruitful area for future study (Kuwako et al., 2004).

Interestingly, two of the seven subnetwork linkage genes identified, UBC and EP300, have not been extensively studied in the context of brain plasticity. These two linkage genes and their encoded proteins could be important targets for future studies to explore their involvement in patients with acute brain injury or neurodegenerative diseases. However, this underscores the benefit of the methodological approach undertaken in our study: combing a large-scale dataset through data mining we can construct an overview of the interactions that may exist between different studies but have not previously been discovered due to the inability to consistently combine all elements of literature into a new single paper in isolation. It is important to note, that this approach is limited to in silico analyses and results are based on mined data further analyzed by bioinformatical software-tool built on mathematical predictions and information acquired from previously published studies. Getting the most of this approach, it is necessary to perform biological validation in order to make further conclusions, but generating new hypotheses and finding new candidate molecules or genes is the potentiality of this approach.

Conclusion

Most importantly, this systematic data mining approach is not restricted to only p75NTR studies, but can be applied to study other diseases, mechanisms, and networks as well. With the approach used herein, researchers may be able to provide utilizable large-scale gene and functional network libraries in regards to a research question in interest. These results not only discover new possible target genes for further investigation, but also validate previously conducted research that identified pathways, genes, and clusters which highlighted biological functions of primary hypothesis. Here the methods were applied to p75NTR, and it is clear that more studies are needed to understand and validate the biological complexity of p75NTR with its related genes and pathways. Furthermore, the same need is present in other fields of biomedical research suggesting that this methodology should be applied to gleam new insights from the vast amounts of pre-existing data.

Additional file: Open peer review report 1 (76.7KB, pdf) .

Footnotes

P-Reviewer: Zagrebelsky M; C-Editors: Zhao M, Qiu Y; T-Editor: Jia Y

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial support: None.

Copyright license agreement: The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Open peer reviewer: Marta Zagrebelsky, Technische Universitat Braunschweig, Germany.

References

- 1.Bai Y, Markham K, Chen F, Weerasekera R, Watts J, Horne P, Wakutani Y, Bagshaw R, Mathews PM, Fraser PE, Westaway D, St George-Hyslop P, Schmitt-Ulms G. The in vivo brain interactome of the amyloid precursor protein. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:15–34. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700077-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boiko AD, Razorenova OV, van de Rijn M, Swetter SM, Johnson DL, Ly DP, Butler PD, Yang GP, Joshua B, Kaplan MJ, Longaker MT, Weissman IL. Human melanoma-initiating cells express neural crest nerve growth factor receptor CD271. Nature. 2010;466:133–137. doi: 10.1038/nature09161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldeira MV, Salazar IL, Curcio M, Canzoniero LM, Duarte CB. Role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in brain ischemia: Friend or foe? Prog Neurobiol. 2014;112:50–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao MV. Cleavage of p75 neurotrophin receptor is linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:300–301. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crutcher E, Pal R, Naini F, Zhang P, Laugsch M, Kim J, Bajic A, Schaaf CP. MTOR and autophagy pathways are dysregulated in murine and human models of Schaaf-Yang syndrome. Sci Rep. 2019;9:15935. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52287-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleitas C, Piñol-Ripoll G, Marfull P, Rocandio D, Ferrer I, Rampon C, Egea J, Espinet C. ProBDNF is modified by advanced glycation end products in Alzheimer’s disease and causes neuronal apoptosis by inducing p75 neurotrophin receptor processing. Mol Brain. 2018;11:68. doi: 10.1186/s13041-018-0411-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuwako K, Taniura H, Yoshikawa K. Necdin-related MAGE proteins differentially interact with the E2F1 transcription factor and the p75 neurotrophin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1703–1712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lad SP, Neet KE. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway through p75NTR: a common mechanism for the neurotrophin family. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73:614–626. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latina V, Caioli S, Zona C, Ciotti MT, Borreca A, Calissano P, Amadoro G. NGF-dependent changes in ubiquitin homeostasis trigger early cholinergic degeneration in cellular and animal AD-model. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:487. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee R, Kermani P, Teng KK, Hempstead BL. Regulation of cell survival by secreted proneurotrophins. Science. 2001;294:1945–1948. doi: 10.1126/science.1065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee WD, Wang KC, Tsai YF, Chou PC, Tsai LK, Chien CL. Subarachnoid hemorrhage promotes proliferation, differentiation, and migration of neural stem cells via BDNF upregulation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu DZ, Waldau B, Ander BP, Zhan X, Stamova B, Jickling GC, Lyeth BG, Sharp FR. Inhibition of Src family kinases improves cognitive function after intraventricular hemorrhage or intraventricular thrombin. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:2359–2367. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16666291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDonald JI, Gryz EA, Kubu CJ, Verdi JM, Meakin SO. Direct binding of the signaling adapter protein Grb2 to the activation loop tyrosines on the nerve growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, TrkA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18225–18233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meeker RB, Williams KS. The p75 neurotrophin receptor: at the crossroad of neural repair and death. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:721–725. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.156967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nalbandian A, Djakiew D. The p75(NTR) metastasis suppressor inhibits urokinase plasminogen activator, matrix metalloproteinase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2006;23:107–116. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9009-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park H, Poo M. Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:7–23. doi: 10.1038/nrn3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ploughman M, Windle V, MacLellan CL, White N, Doré JJ, Corbett D. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor contributes to recovery of skilled reaching after focal ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2009;40:1490–1495. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sajanti A, Lyne SB, Girard R, Frantzén J, Rantamäki T, Heino I, Cao Y, Diniz C, Umemori J, Li Y, Takala R, Posti JP, Roine S, Koskimäki F, Rahi M, Rinne J, Castrén E, Koskimäki J. A comprehensive p75 neurotrophin receptor gene network and pathway analyses identifying new target genes. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schecterson LC, Bothwell M. Neurotrophin receptors: old friends with new partners. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:332–338. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sebastiani A, Gölz C, Werner C, Schäfer MK, Engelhard K, Thal SC. Proneurotrophin binding to P75 neurotrophin receptor (P75ntr) is essential for brain lesion formation and functional impairment after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1599–1607. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen LL, Li WW, Xu YL, Gao SH, Xu MY, Bu XL, Liu YH, Wang J, Zhu J, Zeng F, Yao XQ, Gao CY, Xu ZQ, Zhou XF, Wang YJ. Neurotrophin receptor p75 mediates amyloid β-induced tau pathology. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;132:104567. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shepheard SR, Chataway T, Schultz DW, Rush RA, Rogers ML. The extracellular domain of neurotrophin receptor p75 as a candidate biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang TT, Tian C, Sun J, Wang H, Zhang BY, Chen C, Wang J, Xiao K, Chen LN, Lv Y, Gao C, Shi Q, Xin Y, Dong XP. Down-regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its signaling components in the brain tissues of scrapie experimental animals. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;79:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao D, Qin XP, Chen SF, Liao XY, Cheng J, Liu R, Lei Y, Zhang ZF, Wan Q. PTEN inhibition protects against experimental intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury through PTEN/E2F1/β-catenin pathway. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:281. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.