Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS:

Immune dysregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of pediatric acute liver failure (PALF). Our aim was to identify immune activation markers (IAMs) in PALF that are associated with a distinct clinical phenotype and outcome.

APPROACH AND RESULTS:

Among 47 PALF study participants, 12 IAMs collected ≤6 days after enrollment were measured by flow cytometry and IMMULITE assay on blood natural killer and cluster of differentiation 8–positive (CD8+) lymphocytes and subjected to unsupervised hierarchical analyses. A derivation cohort using 4 of 12 IAMs which were available in all participants (percent perforin-positive and percent granzyme-positive CD8 cells, absolute number of CD8 cells, soluble interleukin-2 receptor level) were sufficient to define high (n = 10), medium (n = 15), and low IAM (n = 22) cohorts. High IAM was more frequent among those with indeterminate etiology than those with defined diagnoses (80% versus 20%, P < 0.001). High IAM was associated with higher peak serum total bilirubin levels than low IAM (median peak 21.7 versus 4.8 mg/dL, P < 0.001) and peak coma grades. The 21-day outcomes differed between groups, with liver transplantation more frequent in high IAM participants (62.5%) than those with medium (28.2%) or low IAM (4.8%) (P = 0.002); no deaths were reported. In an independent validation cohort (n = 71) enrolled in a prior study, segregation of IAM groups by etiology, initial biochemistries, and short-term outcomes was similar, although not statistically significant. High serum aminotransferases, total bilirubin levels, and leukopenia at study entry predicted a high immune activation profile.

CONCLUSION:

Four circulating T-lymphocyte activation markers identify a subgroup of PALF participants with evidence of immune activation associated with a distinct clinical phenotype and liver transplantation; these biomarkers may identify PALF participants eligible for future clinical trials of early targeted immunosuppression.

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rapidly progressive condition with high morbidity and mortality in a subset of children, particularly those with an indeterminant diagnosis. Our ability to develop targeted therapies for this heterogeneous group is hampered by poor understanding of disease pathogenesis and lack of reliable prognostic tools and biomarkers predicting short-term outcome. Given these deficits, clinicians initiate transplant listing within 1-2 days of presentation while continuing supportive care and awaiting spontaneous recovery.(1)

Previous efforts to identify an alternative or supplementary treatment strategy that improves outcome have been largely unsuccessful. In children with non-acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver failure, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) failed to improve 1-year survival in a placebo-controlled clinical trial.(2) In fact, children less than 2 years of age who received placebo were significantly more likely to be alive with their native liver than those receiving NAC. In a retrospective cohort of 361 adults with ALF secondary to autoimmune hepatitis, drug-induced liver failure or indeterminate etiology, use of corticosteroids was not associated with improved overall survival or survival with the native liver.(3) Clearly, other treatment strategies are needed. One possible approach is to identify a targeted cohort for therapy based on biomarkers related to the mechanism of liver injury rather than its presumed etiology, but these studies are lacking in children and adults.

Over the last decade, reports suggest that immune dysregulation plays an important role in disease progression, especially in patients with an indeterminate diagnosis.(4–7) In support of this immune dysregulation theory, the Pediatric Acute Liver Failure (PALF) Study Group has identified a specific interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)-related inflammatory network in participants with PALF that correlated with survival with native liver and more harmful interleukin 6 (IL-6)–producing and IL-8-producing inflammatory networks in those who died.(5) Moreover, others have recently identified hepatic cluster of differentiation 8–positive (CD8+) T-cell infiltration in patients with indeterminate PALF,(8,9) suggesting that this may be a histologic biomarker of immune dysregulation in PALF. Furthermore, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) may present with ALF, and aberrant T-lymphocyte activation has been reported for this condition in patients of various age groups ranging from neonates to adults.(10–14) Activated CD8 lymphocytes are ascribed a pathogenic role in defective degranulation of T and natural killer (NK) lymphocytes and subsequent inflammatory tissue injury in HLH. Furthermore, acute presentation of autoimmune hepatitis, in which CD8 cells are proven to be drivers of disease in preclinical models, is a frequent known cause of ALF in adults and is suspected to be frequently unrecognized in patients with presumed indeterminate ALF.(3,15,16)

Based upon these observations, we hypothesize that a proportion of children with ALF display activation of circulating lymphocytes at diagnosis which can be linked to specific etiologies, for instance, HLH, autoimmune hepatitis, or indeterminate ALF, and distinct clinical phenotype and outcomes. Our approach is to identify biomarkers of immune activation (IA) that associate with a distinct phenotype of PALF that may be amenable to directed immunotherapy.

Participants and Methods

This observational cohort study was conducted by the PALF study group funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Participants <18 years of age were eligible for enrollment if they met the following 4 criteria: (1) no prior evidence of chronic liver disease, (2) biochemical evidence of acute liver injury, (3) hepatic insufficiency characterized by prothrombin time (PT) ≥ 20 seconds or international normalized ratio (INR) ≥ 2.0 (not correctable with vitamin K) or by a PT ≥ 15 seconds or INR ≥ 1.5 in the presence of encephalopathy, and (4) informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardian. Encephalopathy grade scales were used as described.(17) Diagnostic evaluation, medical management, and assigning the final diagnosis were directed by the attending physician(s) and consistent with the standard of care at each site as reported.(18)

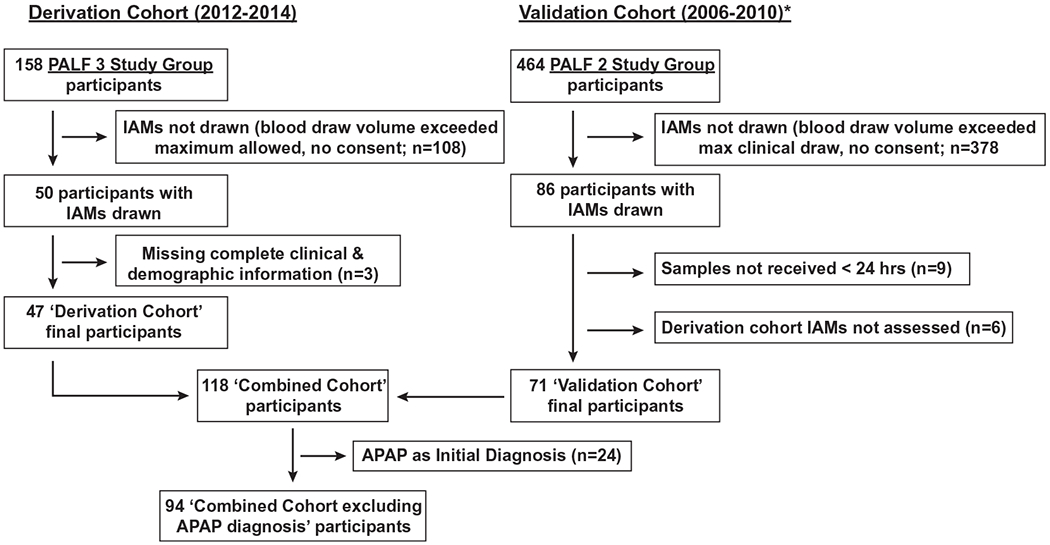

Eligibility for participation in the derivation cohort included (1) enrollment in the PALF longitudinal study between December 2012 and December 2014 and (2) having available blood samples obtained within 6 days of study enrollment for analysis of 15 immune cell biomarkers at a Central Immune Laboratory. Between December 2012 and December 2014, 158 PALF participants were enrolled and were subject to diagnostic testing recommendations incorporated into site electronic medical record order sets to improve the specificity of diagnosis.(18) Among 50/158 participants meeting eligibility for the derivation cohort, complete clinical and demographic information was unavailable for 3 participants, leaving 47 participants in the derivation cohort (see Fig. 1). There were no differences in gender, peak coma grade, total bilirubin, or liver transplant rate between those in the derivation cohort (n = 47) and those who were not (n = 111). However, participants in the derivation cohort were older, were less likely to have a metabolic or viral diagnosis, and had higher entry and peak serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels; and there were no deaths compared to those not in the derivation cohort (Supporting Table S1).

FIG. 1.

Consort diagram of participant selection process for derivation, validation, and combined cohorts. Phases 2 and 3 PALF Study Group participants were eligible for inclusion in the validation and derivation cohorts as described. *Validation cohort initially described in Bucuvalas et al.(6)

The validation cohort comprised a convenience sample of 86 previously reported PALF participants with samples for T-cell IA were analyzed.(6) Between 2006 and 2010, 464 participants, including those in the validation cohort, were enrolled in the PALF study but were not subjected to diagnostic testing recommendations that occurred in the later derivation cohort. Among the 86 participants in the validation cohort, 9 were excluded as samples were not received within 24 hours, leaving 77 participants with clinical data and any results of immune marker analysis. There were 71/77 participants with complete information on selected IA markers (IAMs) identified in the derivation cohort analysis who thus served as the validation cohort (see Fig. 1). There were no significant differences in gender, final diagnosis, peak coma grade, total bilirubin, frequency of death, or liver transplant rate between those who were in the validation cohort (n = 71) and those who were not (n = 393). Participants in the validation cohort were older and had higher entry and peak serum ALT levels compared to those who were not (see Supporting Table S2). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all institutions, and the NIDDK provided a certificate of confidentiality. A Data and Safety Monitoring Board with members appointed by the NIDDK provided study oversight.

Procedures for collection of blood samples for immunophenotyping and shipping to the central laboratory have been described.(6) Fifteen IAMs for all participants in both cohorts were assessed by IMMULITE assay (soluble IL-2 receptor [IL2SR]) or flow cytometry (all remaining IAMs) at the Diagnostic Immunology Laboratory at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center using established staining protocols, as reported.(19,20) Age-specific normative expression levels for the activation markers were determined by the Diagnostic Immunology Laboratory,(21) as shown in Supporting Table S3. Results of IAMs were transformed to fold of age-specific lower or upper limit of normal (ULN) (see Supporting Table S4). Three biomarkers (NK lytic function, percent perforin-positive NK T cells, percent granzyme-positive NK T cells) were removed from further analysis because of excessive lack of data, leaving 12 IAMs for analysis (see Supporting Table S4). In a separate analysis, results of liver tissue immunohistochemical staining for CD 8 T cells on a subset of derivation participants was provided by our collaborators. These data were available as part of a separate ongoing study analysis examining immune cell infiltrates in liver tissue specimens from PALF Study Group participants aged 1-17 years that excluded those with ischemia, cardiac or septic shock, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and autoimmune hepatitis. CD8 T-cell staining was subjectively scored by investigators blinded to final diagnosis as dense, moderate, or minimal, as reported.(8)

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To determine, in a clinically unbiased manner, if there were any patterns in study participant immune cell biomarker levels and then to determine if such patterns correlated with participant disease outcomes, we employed an unsupervised method of hierarchical cluster analyses wherein no clinical information was used to identify such natural patterns of biomarker expression levels. Cluster analyses on log-transformed IAMs, with a Euclidian distance measure, were performed with the complete linkage method, using standard R function. Investigators performing the hierarchical cluster analysis were blinded to participant-specific clinical data. The number of cluster groups assigned in the two hierarchical analyses was determined by gap analysis, using the R package “cluster.”(22,23) In descriptive statistics, continuous variables are reported as median and 25th and 75th percentiles. These data were compared among the three IAM groups using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Frequencies and percentiles of categorical variables are reported. These variables were compared using χ2 and exact tests where appropriate. Holm-Bonferroni step down adjusted P values are reported for post hoc cluster comparisons. Twenty-one-day cumulative incidence rates for the competing risks of liver transplantation and death are reported. Survival with native liver is defined as 1- the cumulative incidence of death or, if there are no deaths, 1- cumulative incidence of liver transplantation. Gray’s test is used to compare the cumulative incidence functions among the clusters.

Results

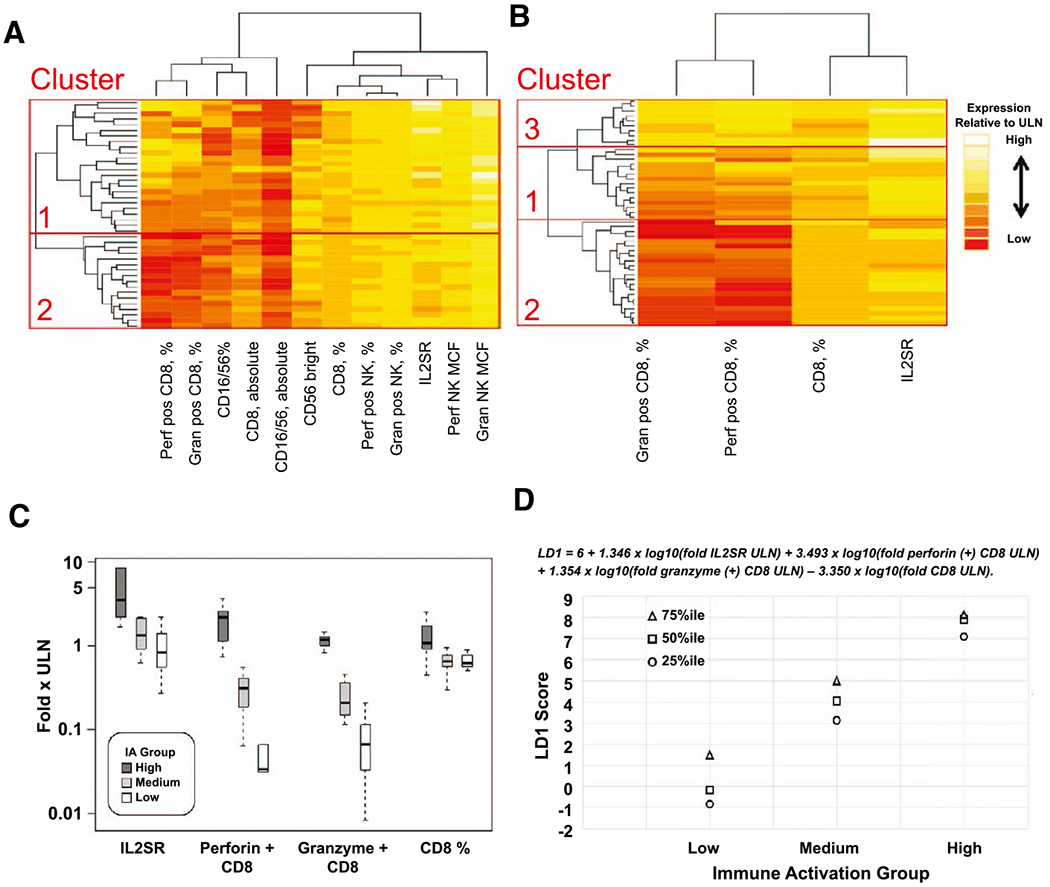

For the derivation cohort, two unsupervised hierarchical analyses (HAs) of IAM expression results were performed to determine an optimal approach for IAM analysis. The first HA used 41 participants wherein all 12 biomarkers related to absolute numbers of circulating CD8 and NK cells, cytotoxic perforin and granzyme proteins were expressed on these cell populations, and IL2SR was measured (HA-12). The second HA was limited to four biomarkers that were available for all 47 participants (HA-4), both to maximize the number of participants included in our analyses and because many of the excluded eight analytes were missing among participants. The four analytes used in HA-4 included IL2SR, percent perforin-positive CD8, percent granzyme-positive CD8, and percent CD8. Distribution of the four IAMs among the 47 participants and correlation between the four IAMs are shown in Supporting Fig. S1. For these four IAMs, abnormal values were all above the ULN. Results from expression analysis for HA-12 and HA-4 are displayed in heatmaps in Fig. 2A,B, respectively. Gap analyses showed HA-12 (n = 41) had two IAM cluster groups associated with low (group 2) and high (group 1) IA, while HA-4 (n = 47) identified three IAM cluster groups with low (group 2), medium (group 1), and high (group 3) degrees of IA (Supporting Fig. S2). The high IAM cluster of HA-4 contained 10 participants: 7 were in the high IAM cluster of HA-12 and 3 were not included in HA-12 as they had fewer than 12 IAM results. Given the importance of examining those participants with high IAMs, we determined that the four IAMs (i.e., percent perforin-positive CD8 cells, percent granzyme-positive CD8 cells, percent CD8 cells, and IL2SR levels) were sufficient to define cluster group assignments.

FIG. 2.

Unsupervised hierarchical analysis of IAM expression results and development of an LD equation to determine the degree of IA in PALF at presentation. In (A), 12 IAMs (absolute number of CD8 and NK cells and their percent of lymphocytes, percent of CD8 and NK cells expressing perforin or granzyme, median fluorescent intensity of perforin/granzyme expression on NK cells, and IL2SR level) were available in 41 participants and subjected to cluster analysis. Gap analyses identified two IA cluster groups associated with low (group 2) and high (group 1) degrees of IA. In (B), four biomarkers (percent perforin-positive CD8 cells, percent granzyme B-positive CD8 cells, percent CD8+ lymphocytes, and IL2SR) were included in the analysis, which increased the number of participants with PALF to 47. Gap analyses identified three IA cluster groups with low (group 2), medium (group 1), and high (group 3) degrees of IA (also see Supporting Fig. S2). In (C), the discrimination between the expression levels (medians and interquartile ranges) for the four IAMs is displayed for the 47 participants assigned to low, medium, or high IA based on the cluster analysis of HA-4. In (D), the equation to calculate the LD score and the interquartile range for LD1 scores for assignment to IA group are displayed. Abbreviations: Gran, granzyme; MCF, mean channel fluorescence; Perf, perforin.

Next, we developed a linear discriminant (LD) function of the four IAMs used in HA-4. LD analysis identified the linear equation LD1 = 6 + 1.3458 × log10 (fold IL2SR ULN) + 3.4934 x log10 (fold perforin positive CD8 ULN) + 1.3544 × log10 (fold granzyme positive CD8 ULN) – 3.3496 × log10 (fold CD8 ULN) to generate mean and interquartile scores that allow clear separation of IAM groups (Fig. 2C,D). The LD function resulting from the derivation cohort was applied to the validation cohort of PALF participants. IAM cluster groups from HA-4 in the derivation cohort and the validation cohort were subsequently examined with respect to clinical data and 21-day outcomes.

Key demographic and clinical measures for the derivation cohort stratified by IAM groups based upon the four IAMs analyzed in HA-4 are shown in Table 1. The final PALF diagnosis significantly differed between the groups (P = 0.0007), with indeterminate etiology being most prevalent in the high IAM group, while APAP ingestion and drug-induced PALF segregated with low IA. Significantly more participants exhibited a peak coma grade of ≥ 2 in group 3 compared with participants in groups 1 and 2. High IAM at presentation segregated with nearly 6 times higher serum total bilirubin levels at study entry and 3-fold increased levels of the highest recorded value (e.g., peak) compared with participants with low or medium IAMs. Known steroid exposures pre–study entry and post–study entry and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment post–study entry were not significantly different between IA groups. Aplastic anemia developed in 6% of the entire cohort within 12 months after enrollment into the study but only among those with a high IA phenotype (P = 0.007). The 21-day cumulative incidence of liver transplantation within the low, medium, and high IAM cohorts was 1/22 (4.8%), 4/15 (28.2%), and 6/10 (62.5%), respectively (P = 0.002). No deaths occurred within 21 days.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Values for PALF Participant IA Groups for the Derivation Cohort (n = 47)*

| Characteristic | Low IAM |

Medium IAM |

High IAM |

P

|

Post Hoc Analysis Adjusted P† |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 22) | (n = 15) | (n = 10) | For Overall Group Comparison | Low versus Medium IA | Medium versus High IA | Low versus High IA | |

| Age | 14.5 | 13.7 | 6.2 | 0.11 | |||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | (4.8-16.6) | (3.6-15.3) | (3.8-9.0) | ||||

| Male | 8 (36) | 8 (53) | 8 (80) | 0.076 | |||

| Final diagnosis | 0.0007 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.005 | |||

| APAP | 9 (41) | 4 (27) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Autoimmune | 0 (0) | 3 (20) | 1 (10) | ||||

| Drug-induced | 4 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| HLH | 0 (0) | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Indeterminate | 4 (18) | 3 (20) | 8 (80) | ||||

| Metabolic | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Viral | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Other | 3 (14) | 2 (13) | 1 (10) | ||||

| Coma grade, peak | 0.048 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.004 | |||

| 0 | 13 (65) | 7 47) | 2 (22) | ||||

| 1 | 4 (20) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | ||||

| 2 | 0 (0) | 3 (20) | 5 (56) | ||||

| 3 | 2 (10) | 2 (13) | 1 (11) | ||||

| 4 | 1 (5) | 1 (7) | 1 (11) | ||||

| Not assessable, % of total (n) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Missing, % of total (n) | 0(0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | ||||

| ALT (IU/L), study entry, n | 22 | 15 | 10 | 0.039 | 0.1 | 0.78 | 0.1 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 5,249 (2,916-7,570) | 3,076 (1,191-5,065) | 2,492 (1,655-3,362) | ||||

| ALT (IU/L), peak, n | 22 | 15 | 10 | 0.07 | |||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 5,249 (3,780-7,787) | 4,077 (1,282-8,891) | 2,492 (1,879-3,362) | ||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL), study entry, n | 0.0006 | 0.59 | 0.007 | 0.0003 | |||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 20 | 12 | 8 | ||||

| 3.5 (1.8-4.9) | 3.3 (2.0-13.9) | 18.6 (15.6-26.1) | |||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL), peak, n | 20 | 13 | 10 | 0.0007 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.0003 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 4.8 (2.1-12.0) | 7.9 (2.5-18.0) | 21.7 (16.7-24.4) | ||||

| Treated with corticosteroids within 30 days prior to study entry, n (%) Yes | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No/unknown | 21 (95) | 15 (100) | 10 (100) | ||||

| Treated with corticosteroids within 7 days after study entry, n (%) Yes | 3 (14) | 7 (47) | 4 (40) | 0.074 | 0.168 | 1.00 | 0.332 |

| No/unknown | 19 (86) | 8 (53) | 6 (60) | ||||

| Treated with IVIG: Yes | 2 (9) | 0 | 1 (10) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No/unknown | 20 (91) | 15 (100) | 9 (90) | ||||

| Subsequent diagnosis of aplastic anemia: Yes | 0 | 0 | 3 (30) | 0.007 | 1.0 | 0.104 | 0.073 |

| No/unknown | 22 (100) | 15 (100) | 7 (70) | ||||

| 21-day cumulative incidence, n (%) | |||||||

| Liver transplantation | 1 (4.8) | 4 (28.2) | 6 (62.5) | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.001 |

| Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

Study entry can be measured up to 3 days before enrollment. Peak can be measured from study entry up to 21 days after enrollment.

Adjusted using Holm step-down Bonferroni method.

The LD function described above was applied to the validation cohort. Distribution of the IAMs among participants in the validation cohort and correlation between the four IAMs were similar to the derivation cohort. By applying the LD1 equation and the cutoff values for assignment to groups of low, medium, or high IAMs as established in the derivation cohort, 16 (23%), 30 (42%), and 25 (35%) of the participants were designated as high, medium, and low IAM, respectively, at presentation (Table 2; Supporting Fig. S3). Demographic and clinical values for this cohort according to level of IA are shown in Table 2. Similar to the derivation cohort, high IAM participants in the validation cohort were more likely to have an indeterminate etiology, less likely to have a metabolic or viral etiology, had higher serum total bilirubin at study entry and peak, and had slightly lower survival with native liver compared to low and medium IAM participants, although this did not achieve statistical significance.

TABLE 2.

Demographic and Clinical Values for PALF Subject IA Groups for the Validation Cohort (n = 71)*

| Low IAM |

Medium IAM |

High IAM |

Nominal |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (n = 25) | (n = 30) | (n = 16) | P |

| Age at enrollment, median (Q1-Q3) | 8.1 (3.1-16.5) | 9.0 (3.7-16.1) | 8.2 (3.7-12.7) | 0.76 |

| Male | 7 (28) | 16 (53) | 8 (50) | 0.14 |

| Final diagnosis | 0.1 | |||

| APAP | 3 (12) | 7 (23) | 1 (6) | |

| Autoimmune | 2 (8) | 3 (10) | 2 (13) | |

| Drug-induced | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |

| HLH | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | |

| Indeterminate | 8 (32) | 9 (30) | 9 (56) | |

| Metabolic | 4 (16) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Viral | 2 (8) | 5 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 5 (20) | 4 (13) | 1 (6) | |

| Coma grade peak, n % | ||||

| 0 | 9 (39) | 9 (30) | 6 (38) | 0.76 |

| 1 | 6 (26) | 8 (27) | 5 (31) | |

| 2 | 5 (22) | 6 (20) | 3 (19) | |

| 3 | 3 (13) | 4 (13) | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 2 (13) | |

| Not assessable, n (% of total) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing, n (% of total) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | |

| Study entry ALT (IU/L), n | 25 | 29 | 16 | 0.34 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 1,396 (497-3,547) | 2,527 (873-4,026) | 2,240 (1,337-2,901) | |

| Peak ALT (IU/L), n | 25 | 29 | 16 | 0.41 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 1,578 (497-4,315) | 3,393 (873-5,305) | 2,295 (1,394-2,979) | |

| Study entry total bilirubin (mg/dL), n | 22 | 25 | 14 | 0.06 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 9.6 (1.8-21.1) | 5.9 (2.2-15.8) | 17.6 (10.1-25.3) | |

| Peak total bilirubin (mg/dL), n | 22 | 27 | 15 | 0.06 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 12.2 (3.6-22.2) | 8.7 (2.7-19.9) | 23.0 (15.8-27.7) | |

| 21-day cumulative incidence n (%) | ||||

| Liver transplantation | 3 (12.0) | 10 (34.5) | 6 (37.5) | 0.12 |

| Death | 1 (4.0) | 2 (7.0) | 1 (6.3) | 0.89 |

Study entry can be measured up to 3 days before enrollment. Peak can be measured from study entry up to 21 days after enrollment.

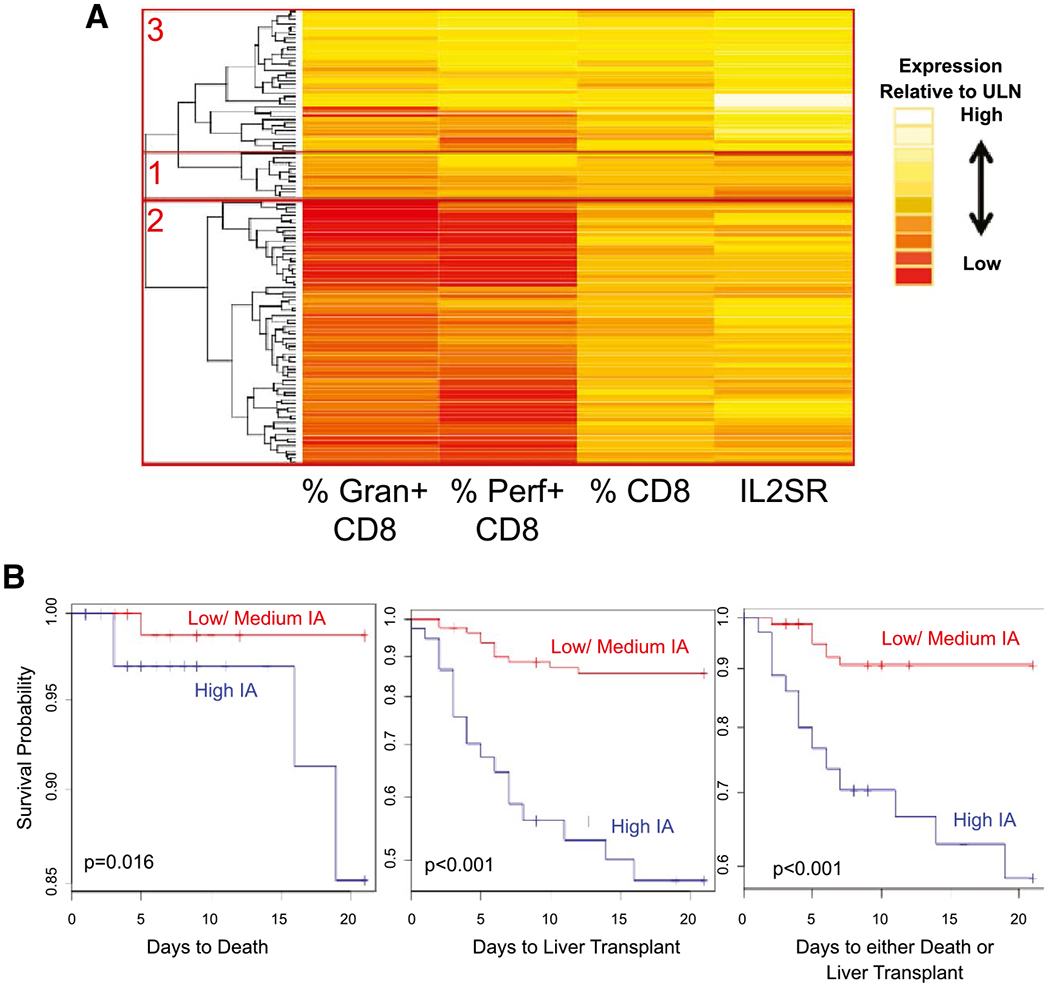

When the two cohorts were combined and subjected to unsupervised cluster analysis with the four IAMs used in HA-4, three groups emerged from these 118 participants: high IAM (n = 37), medium IAM (n = 12), and low IAM (n = 69). Compared with cluster analysis used for the derivation and validation cohorts, in this combined cohort many of the participants with medium IAMs had dissipated into the two adjacent clusters (Fig. 3A). Again, the high IAM cohort was associated with indeterminate etiology of PALF, higher entry, and peak bilirubin levels (Table 3). Survival probability for the first 21 days after study entry was significantly lower for the 37 participants with high IA compared with the 81 children with low or medium IA when considering death, liver transplant, or death or liver transplant as censored events (Fig. 3B). As a sensitivity analysis and in order to examine whether low IAM levels in the majority of participants with APAP exposure drove the clustering, we repeated the cluster analysis following exclusion of 24 participants from the combined cohort with the initial diagnosis of APAP-induced PALF. Clustering of the remaining participants and segregation with biochemical or clinical outcome findings were not appreciably altered compared to those of the full combined cohort (Supporting Fig. S4 and Table S6).

FIG. 3.

Clustering of participants in the combined cohort of 118 participants. The expression levels for the four IAMs including percent granzyme and percent perforin expressing CD8 cells, number of circulating CD8 lymphocytes, and serum levels for IL2SR were subjected to unsupervised cluster analysis defining three groups of participants in the 118 participants enrolled in the derivation and validation cohorts. Gap analyses identified three IA cluster groups with low (group 2), medium (group 1), and high (group 3) degrees of (A). Association between group assignments to high versus combined medium or low IA and 21-day survival with the native liver censored for death, liver transplant, or death or liver transplant is shown in (B). Abbreviations: Gran, granzyme; Perf, perforin.

TABLE 3.

Demographic and Clinical Values for PALF Subject IA Groups for the Combined Cohort (n = 118)*

| Characteristic | Low IAM |

Medium IAM |

High IAM |

Nominal |

Post Hoc Adjusted P† |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 69) | (n = 12) | (n = 37) | P | Low versus Medium IA | Medium versus High IA | Low versus High IA | |

| Age at enrollment, median (Q1-Q3) | 12.0 (4.0-17.0) | 7.5 (4.8-14.3) | 8.0 (4.0-13.0) | <0.373 | <0.985 | <0.985 | P <0.535 |

| Male, n (%) | 26 (37.7) | 4 (33.3) | 25 (67.6) | <0.01‡ | |||

| Final diagnosis, n (%) | |||||||

| APAP | 19 (28) | 4 (33) | 1 (3) | <0.001‡ | |||

| Autoimmune | 5 (7) | 3 (25) | 3 (8) | ||||

| Drug-induced | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | ||||

| HLH | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | ||||

| Indeterminate | 15 (22) | 3 (25) | 23 (62) | ||||

| Metabolic | 7 (10) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Viral | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | ||||

| Other | 13 (19) | 1 (8) | 3 (8) | ||||

| Coma grade at study entry, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 36 (52) | 6 (50) | 18 (49) | <0.880‡ | |||

| 1 | 13 (19) | 1 (8) | 10 (27) | ||||

| 2 | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | ||||

| 3 | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | ||||

| 4 | 2 (3) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Not assessable, n (% of total [n]) | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | ||||

| Missing, n (% of total [n]) | 6 (9) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | ||||

| Study entry ALT (IU/L), n | 69 | 12 | 36 | <0.017 | <0.685 | <0.320 | <0.013 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 1,419 (149-4,809) | 1,148 (489.2-3,463) | 2,817 (2,187-3,553) | ||||

| Peak ALT (IU/L), n | 69 | 12 | 36 | <0.726 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 4,620 (2,068-7,787) | 2,276 (919-7,159) | 2,859 (2,187-3,696) | ||||

| Study entry total bilirubin (mg/dL), n | 65 | 10 | 35 | <0.001 | 0.903 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 2.3 (1.1-10.0) | 3.1 (1.3-4.4) | 15.2 (10.9-22.6) | ||||

| Peak total bilirubin (mg/dL), n | 65 | 10 | 35 | <0.001 | 0.529 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 4.9 (2.2-14.6) | 4.1 (3.0-4.8) | 23.0 (17.2-28.4) | ||||

| 21-day cumulative incidence, % (n) | |||||||

| Survival with native liver, n incidence rate§ | 87.0 (60) | 75.0 (9) | 40.5 (15) | <0.001‡ | |||

| Liver transplantation, n incidence rate | 11.6 (8) | 25.0 (3) | 51.4 (19) | ||||

| Death, n incidence rate | 1.4 (1) | 0 (0) | 8.1 (3) | ||||

Study entry can be measured up to 3 days before enrollment. Peak can be measured from study entry up to 21 days after enrollment.

Adjusted using Holm step-down Bonferroni method.

Fisher’s test.

Estimate, assuming no dropouts or losses to follow-up.

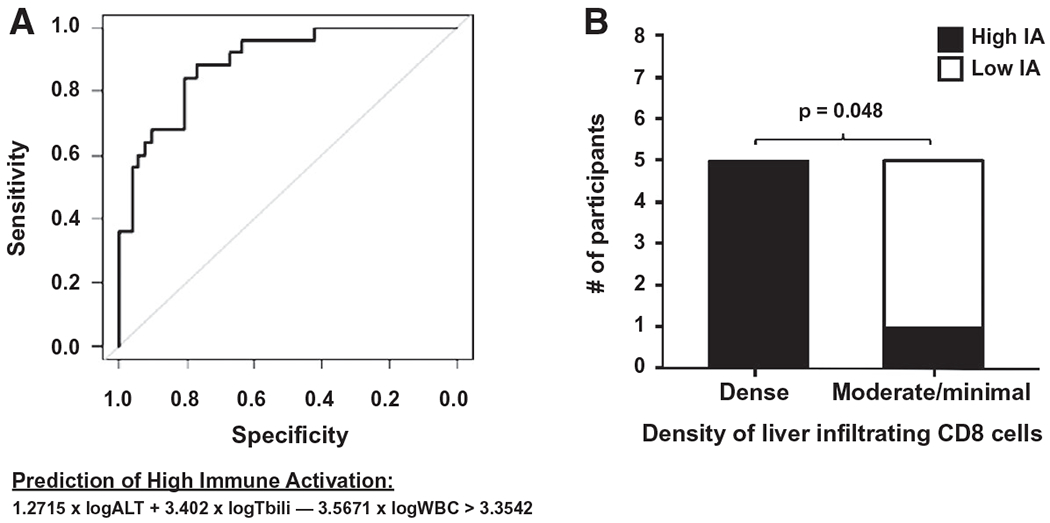

Recognizing a potential limitation of measuring granzyme and perforin expression on CD8 lymphocytes in clinical practice, we searched for predictors of high IAM using entry parameters available in routine clinical practice. In a univariate analysis, elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ALT, and bilirubin, and lower white blood count (WBC) at study entry were associated with high IA (Table 4). A multivariable logistic regression analysis included 77 participants with complete sets of baseline clinical and biochemical parameters. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis revealed a sensitivity and specificity of 0.84 and 0.81, respectively, in predicting high IA using entry clinical variables and the following equation: 1.2715 × logALT + 3.4021 × logtotal bilirubin – 3.5671 × logWBC > 3.3542. The area under the curve (AUC) for a cutoff of 3.35 in predicting high IA is 0.89 (Fig. 4A). Exclusion of participants with an initial APAP diagnosis did not alter the sensitivity, specificity, or AUC of the ROC analysis (see Supporting Fig. S4). Using available liver tissue for 10 participants in the derivation cohort, there was a significant association between CD8 T-cell hepatic infiltration and high IA status. All participants with dense CD8 staining (n = 5) were in the high IA group compared to only 1 participant with high IA among those with moderate or minimal CD8 staining (Supporting Fig. S4B).

TABLE 4.

Univariate Analysis of Entry Clinical Measurements Among Three Clusters in the Combined Cohort (n = 118)

| Measure | IA Group Means |

Tukey’s Multiple Comparison P |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Low | High | Low versus Medium | High versus Medium | High versus Low | |

| logAST | 3.148 | 2.952 | 3.46 | 0.650 | 0.388 | 0.005 |

| logALT | 3.029 | 2.904 | 3.385 | 0.852 | 0.319 | 0.009 |

| logTotal bilirubin | 0.469 | 0.457 | 1.093 | 0.998 | 0.007 | <0.001 |

| logINR | 0.388 | 0.385 | 0.344 | 0.999 | 0.812 | 0.671 |

| logWBC | 1.004 | 0.994 | 0.813 | 0.994 | 0.146 | 0.013 |

| logPlatelets | 2.241 | 2.228 | 2.262 | 0.991 | 0.979 | 0.871 |

| Age (years) | 9.028 | 10.402 | 8.743 | 0.734 | 0.988 | 0.349 |

| logFerritin | 3.147 | 2.481 | 0.178 | |||

FIG. 4.

Prediction of high IA using routine clinical laboratory tests at study entry and liver tissue CD8 immunohistochemistry. In (A), a ROC curve is shown following a multivariable logistic regression analysis of 77 participants with the complete set of the clinical parameters ALT, total bilirubin, and WBC obtained at study entry. A value > 3.3542 was used to predict high IA. In (B), CD8 immunohistochemistry of liver tissue available from PALF participants (n = 10) in the derivation cohort was subjectively scored by investigators blinded to clinical information and thereafter compared to IA group status. There were no medium IA group specimens in those with liver tissue available for analysis. Abbreviation: Tbili, total bilirubin.

Discussion

We have shown that the combination of high perforin and granzyme expression in CD8 lymphocytes along with elevated absolute CD8 lymphocyte count and serum level of IL2SR were associated with a distinct PALF phenotype. PALF participants with high levels of these biomarkers of IA were generally characterized as having an indeterminate diagnosis, higher serum levels of total bilirubin and peak coma grades, and, importantly, decreased 21-day survival with their native liver compared with patients presenting with a low or medium degree of IA. These findings identify a PALF cohort who may benefit from immunotherapy, but this requires a well-designed clinical trial to confirm safety and efficacy.

IAMs identified in this analysis correlate with activation of CD8 cells. A growing body of evidence is assigning this lymphocyte population a central role in disease pathogenesis of acute hepatitis. In a recent case–control study, examination of the liver histopathology found a high density of CD8 lymphocytes expressing perforin to be prevalent in 33 participants with indeterminate etiology as opposed to 14 patients with known causes of PALF.(8) In a case series of 9 participants with either indeterminate ALF or acute severe hepatitis, CD8 lymphocytes were the predominant liver infiltrating cell population in all patients, and 6 of these participants improved after treatment with immunosuppressive therapy using IVIG and methylprednisolone.(9) Both studies reported that aplastic anemia developed following resolution of hepatitis in about 23% of participants. Collectively, these clinical studies in PALF and aplastic anemia indicate that the four biomarkers used to assess IA are linked to liver injury mechanisms which are prominent in a subset of patients independent of the etiology. Our findings here reinforce these prior observations and show that a high IA PALF group status is associated with a worse clinical outcome, including the development of aplastic anemia. It is important to note, however, that not all participants with indeterminate PALF or with autoimmune hepatitis displayed high IAMs at diagnosis.

It remains uncertain whether activated CD8 lymphocytes expressing granzyme and/or perforin are directly linked to rapid disease progression leading to death or liver transplantation as a short-term outcome in PALF. While CD8 depletion was shown to be hepatoprotective and to ameliorate features of HLH in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)–infected, perforin-deficient mice(24) and from LCMV-induced aplastic anemia,(25) no murine models of ALF demonstrate a pathogenic role for CD8 lymphocytes. On the contrary, preclinical models of acute hepatitis and ALF depend on IFN-γ-producing CD4 cells, while CD8-targeted therapies were not found to confer protection.(26,27) Hence, whether the association between liver-infiltrating CD8 lymphocytes and high frequency of circulating activated CD8 cells with indeterminate PALF means that CD8-targeted therapy can halt progression of ALF requires well-conducted clinical trials with adequate controls. We propose that immune profiling using these four IAMs may be an additional tool to identify participants most likely to respond to T lymphocyte–directed therapy.

In a small convenience sample of 10 participants from the derivation cohort, dense hepatic CD8 staining was significantly associated with high IA status. However, future validation studies are needed to determine whether the high expression levels of CD8 lymphocyte–dependent peripheral biomarkers in this study correlate with high prevalence of these cells in the liver. Importantly, identification of routine clinical parameters at presentation of PALF (ALT, total bilirubin, WBC) to predict high IA may aid the design of clinical trials targeting T-lymphocyte activation in ALF in the future. It is possible that the number of these biomarkers can be further reduced when combined with clinical parameters at presentation to best predict clinical outcomes. Given the dynamic nature of PALF, these early clinical parameters may also act in concert with dynamic clinical assessment of encephalopathy and international normalized ratio, which have been associated with clinical outcomes.(28)

The strengths of this study are the prospective measurement of IAM in a central laboratory, the recruitment of participants at multiple centers in North America, the application of unsupervised cluster analysis to the IAMs by investigators blinded to the clinical phenotype, and the validation of findings in an independent cohort. However, it has several limitations. PALF is a rare disorder and, therefore, even large multicenter investigations are faced with small sample sizes, which could lead to type 2 statistical errors in our analyses. In addition, due to blood volume restrictions in younger children, participants recruited for these ancillary studies requiring collection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells for flow cytometry were not representative of the total PALF cohorts: they were biased toward older patients without virus infection, higher entry and peak ALT values, and better outcomes in both cohorts. Hence, it is uncertain whether these biomarkers would be similarly predictive in younger patients and in parts of the world in which virus hepatitis is a more common cause of PALF. Furthermore, the findings of the derivation cohort were only in part validated in an independent cohort, which may be due to different study eras of PALF for the two cohorts. There was a greater emphasis in the latter era encompassing the derivation cohort applying stricter age-specific clinical definitions for PALF final diagnoses,(18) which may have led to more accurate PALF final diagnosis distributions and, thus, explain the lack of significant association between high IAM and indeterminate etiology in the earlier-era validation cohort. Furthermore, although sites participating in the PALF study during the derivation and validation periods were predominantly, but not entirely, similar, changes in patient management between the two time periods might explain differences in disease severity and rates of death and transplantation. Moreover, there was a higher emphasis in the latter PALF Study Group era on obtaining blood draws (both volume and consent) from participants, which led to a greater representation of participants from the latter “derivation” era (i.e., 47/158 or 30% participation) compared to the former “validation” era (i.e., 71/464 or 15% participation; see Supporting Fig. S1).

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that PALF participants with widely disparate rates of survival with native liver can be reliably identified by the application of a simple clinical prediction model based on four IAMs obtained at the time of PALF presentation. These results highlight the emerging importance of CD8 T-cell IA in PALF pathophysiology and, perhaps more importantly, the potential for assessing IAMs at the time of PALF presentation for risk stratification and the targeting of individualized immunotherapy in these high-risk patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

The work was made possible by the collaborative effort of the following current and former principal and coinvestigators of the Pediatric Acute Liver Failure Study (by site) and research coordinators at the University of Pittsburgh: Robert H. Squires, M.D., and Benjamin L. Shneider, M.D., Cincinnati Children’s Hospital: John Bucuvalas, M.D., and Mike Leonis, M.D., Ph.D., Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago: Estella Alonso, M.D., University of Texas Southwestern: Norberto Rodriguez-Baez, M.D., Seattle Children’s Hospital: Karen Murray, M.D., and Simon Horslen, M.D., Children’s Hospital Colorado (Aurora): Michael R. Narkewicz, M.D., St Louis Children’s Hospital: David Rudnick, M.D., Ph.D., and Ross W. Shepherd, M.D., University of California at San Francisco: Philip Rosenthal, M.D., Hospital for Sick Children (Canada): Vicky Ng, M.D., Riley Hospital for Children (Indianapolis): Girish Subbarao, M.D., Emory University: Rene Romero, M.D., Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: Elizabeth Rand, M.D., and Kathy Loomis, M.D., Kings College-London (England): Anil Dhawan, M.D., Birmingham Children’s Hospital (England): Dominic Dell Olio, M.D., and Deirdre A. Kelly, M.D., Texas Children’s Hospital: Saul Karpen, M.D., Ph.D., Mt. Sinai Medical Center: Nanda Kerkar, M.D., University of Michigan: M. James Lopez, M.D., Ph.D., Children’s Hospital Medical Center (Boston): Scott Elisofon, M.D., and Maureen Jonas, M.D., Johns Hopkins University: Kathleen Schwarz, M.D., Columbia University: Steven Lobritto, M.D., and the Epidemiology Data Center (Pittsburgh): Steven H. Belle, Ph.D.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH-NIDDK U01 DK072146 and NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI UL1 RR025780).

Abbreviations:

- ALF

acute liver failure

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- APAP

acetaminophen

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- HA

hierarchical analysis

- HLH

hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- IA

immune activation

- IAM

IA marker

- IL

interleukin

- IL2SR

soluble IL-2 receptor

- INR

international normalized ratio

- IVIG

intravenous immunoglobulin

- LD

linear discriminant

- NIDDK

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- NK

natural killer

- PALF

pediatric ALF

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- ULN

upper limits of normal

- WBC

white blood count

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Miethke consults for Mirum and Metacrine. Dr. Bleesing advises Enzyvant and is employed by UpToDate. Dr. Squires consults for Mirum and received royalties from UpToDate.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.31271/suppinfo.

REFERENCES

- 1).Squires JE, Rudnick DA, Hardison RM, Horslen S, Ng VL, Alonso EM, et al. Liver transplant listing in pediatric acute liver failure: practices and participant characteristics. Hepatology 2018;68:2338–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Squires RH, Dhawan A, Alonso E, Narkewicz MR, Shneider BL, Rodriguez-Baez N, et al. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine in pediatric patients with nonacetaminophen acute liver failure: a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hepatology 2013;57:1542–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Karkhanis J, Verna EC, Chang MS, Stravitz RT, Schilsky M, Lee WM, et al. Steroid use in acute liver failure. Hepatology 2014;59:612–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Antoniades CG, Berry PA, Wendon JA, Vergani D. The importance of immune dysfunction in determining outcome in acute liver failure. J Hepatol 2008;49:845–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Azhar N, Ziraldo C, Barclay D, Rudnick DA, Squires RH, Vodovotz Y. Analysis of serum inflammatory mediators identifies unique dynamic networks associated with death and spontaneous survival in pediatric acute liver failure. PLoS One 2013;8:e78202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Bucuvalas J, Filipovich L, Yazigi N, Narkewicz MR, Ng V, Belle SH, et al. Immunophenotype predicts outcome in pediatric acute liver failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;56:311–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).DiPaola F, Grimley M, Bucuvalas J. Pediatric acute liver failure and immune dysregulation. J Pediatr 2014;164:407–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Chapin CA, Burn T, Meijome T, Loomes KM, Melin-Aldana H, Kreiger PA, et al. Indeterminate pediatric acute liver failure is uniquely characterized by a CD103+CD8+ T-cell infiltrate. Hepatology 2018;68:1087–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).McKenzie RB, Berquist WE, Nadeau KC, Louie CY, Chen SF, Sibley RK, et al. Novel protocol including liver biopsy to identify and treat CD8+ T-cell predominant acute hepatitis and liver failure. Pediatr Transplant 2014;18:503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Jagtap N, Sharma M, Rajesh G, Rao PN, Anuradha S, Tandan M, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis masquerading as acute liver failure: a single center experience. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2017;7:184–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Abdullatif H, Mohsen N, El-Sayed R, El-Mougy F, El-Karaksy H. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis presenting as neonatal liver failure: a case series. Arab J Gastroenterol 2016;17:105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Schneier A, Stueck AE, Petersen B, Thung SN, Perumalswami P. An unusual cause of acute liver failure: three cases of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis presenting at a transplant center. Semin Liver Dis 2016;36:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Alam S, Lal BB, Khanna R, Sood V, Rawat D. Acute liver failure in infants and young children in a specialized pediatric liver centre in India. Indian J Pediatr 2015;82:879–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Ryu JM, Kim KM, Oh SH, Koh KN, Im HJ, Park CJ, et al. Differential clinical characteristics of acute liver failure caused by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children. Pediatr Int 2013;55:748–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Zierden M, Kuhnen E, Odenthal M, Dienes HP. Effects and regulation of autoreactive CD8+ T cells in a transgenic mouse model of autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:975–986.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Ganger DR, Rule J, Rakela J, Bass N, Reuben A, Stravitz RT, et al. Acute liver failure of indeterminate etiology: a comprehensive systematic approach by an expert committee to establish causality. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Ng VL, Li R, Loomes KM, Leonis MA, Rudnick DA, Belle SH, et al. Outcomes of children with and without hepatic encephalopathy from the pediatric acute liver failure study group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;63:357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Narkewicz MR, Horslen S, Hardison RM, Shneider BL, Rodriguez-Baez N, Alonso EM, et al. A learning collaborative approach increases specificity of diagnosis of acute liver failure in pediatric patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16: 1801–1810.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Abdalgani M, Filipovich AH, Choo S, Zhang K, Gifford C, Villanueva J, et al. Accuracy of flow cytometric perforin screening for detecting patients with FHL due to PRF1 mutations. Blood 2015;126:1858–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Mellor-Heineke S, Villanueva J, Jordan MB, Marsh R, Zhang K, Bleesing JJ, et al. Elevated granzyme B in cytotoxic lymphocytes is a signature of immune activation in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Front Immunol 2013;4:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Kogawa K, Lee SM, Villanueva J, Marmer D, Sumegi J, Filipovich AH. Perforin expression in cytotoxic lymphocytes from patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and their family members. Blood 2002;99:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Tibshirani R, Walther G, Hastie T. Estimating the number of clusters in a data set via the gap statistic. J R Statist Soc B 2001;63: 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- 23).Maechler M, Rousseeuw P, Struyf A, Hubert M, Hornik KC. Cluster analysis basics and extensions. R Package Version 2.1.0; 2019.

- 24).Jordan MB, Hildeman D, Kappler J, Marrack P. An animal model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): CD8+ T cells and interferon gamma are essential for the disorder. Blood 2004;104:735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Binder D, van den Broek MF, Kagi D, Bluethmann H, Fehr J, Hengartner H, et al. Aplastic anemia rescued by exhaustion of cytokine-secreting CD8+ T cells in persistent infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Exp Med 1998;187: 1903–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Ikeda A, Aoki N, Kido M, Iwamoto S, Nishiura H, Maruoka R, et al. Progression of autoimmune hepatitis is mediated by IL-18-producing dendritic cells and hepatic CXCL9 expression in mice. Hepatology 2014;60:224–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Robinson RT, Wang J, Cripps JG, Milks MW, English KA, Pearson TA, et al. End-organ damage in a mouse model of fulminant liver inflammation requires CD4+ T cell production of IFN-gamma but is independent of Fas. J Immunol 2009;182:3278–3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Li R, Belle SH, Horslen S, Chen LW, Zhang S, Squires RH. Clinical course among cases of acute liver failure of indeterminate diagnosis. J Pediatr 2016;171:163-170.e1-e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.