Abstract

Expanding clinical strategies to identify high risk groups for psychotic and bipolar disorders is a research priority. Considering that individuals diagnosed with psychotic and bipolar disorder are at high risk of self-harm, we hypothesised the reverse order relationship would also be true (ie, self-harm would predict psychotic/bipolar disorder). Specifically, we hypothesised that hospital presentation for self-harm would be a marker of high risk for subsequent development of psychotic/bipolar disorder and sought to test this hypothesis in a large population sample. This prospective register-based study included everyone born in Finland in 1987, followed until age 28 years (N = 59 476). We identified all hospital records of self-harm presentations, as well as all ICD-10 healthcare registrations of first diagnoses of psychotic and bipolar disorders. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the relationship between self-harm and psychotic/bipolar disorders. Of all individuals who presented to hospital with self-harm (n = 481), 12.8% went on to receive a diagnosis of psychosis (hazard ratio [HR] = 6.03, 95% confidence interval [CI] 4.56–7.98) and 9.4% a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (HR = 7.85, 95% CI 5.73–10.76) by age 28 years. Younger age of first self-harm presentation was associated with higher risk—for individuals who presented before age 18 years, 29.1% developed a psychotic or bipolar disorder by age 28 years. Young people who present to hospital with self-harm are at high risk of future psychotic and bipolar disorders. They represent an important cohort for the prevention of serious mental illness.

Keywords: bidirectional, suicide, register, schizophrenia, mania/epidemiology

Introduction

An important relationship between psychosis and self-harm has been recognised since the early 1900s, when Eugen Bleuler described the “suicidal drive” as the “most serious of all schizophrenic symptoms.” 1 Since that time, dozens of studies have documented a strong risk of (suicidal and non-suicidal) self-harm in individuals with psychotic or bipolar disorders, with up to half of patients reporting at least one lifetime incident.2–6

Research to date has focused on the prospective relationship between diagnoses of psychotic or bipolar disorder and subsequent risk of self-harm. Little attention has been paid to the possibility that the relationship may be bidirectional7,8; that is, that self-harm may follow from but may also precede psychosis or mania onset. Given that neurodevelopmental features of psychotic and bipolar disorders may long precede onset of the disorders themselves,9–11 we hypothesised that self-harm in youth may be a risk marker for later psychotic and bipolar disorders. Specifically, we hypothesised that young people who present to hospital with self-harm would be a high-risk group for future psychotic or bipolar disorders.

Using data linkage of healthcare records for the entire population of children born in Finland in 1987, we identified all hospital presentations for self-harm from age 11 years to 28 years and investigated the absolute and relative risk of subsequent diagnosis of psychotic or bipolar disorders.

Methods

Study Population

This study used data from the longitudinal 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study, which has been described in detail previously.12 Briefly, the cohort is managed by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare in Finland, and comprises information from nationwide registers for all children born in Finland in the year 1987. For the current study, individuals were followed up from birth until date of data extraction, 31 December 2015 (ie, maximum age of the included participants at follow-up was 28 years). The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (Ethical Committee §28/2009), and all data-providing registers gave us permission to use the data for research, as required by Finnish legislation. All data were pseudo-anonymised before analysis by removing unique personal identity code after linkage of register data,13 and data handled according to Finnish data protection laws.

Data Used From National Registers

Individuals were followed up from birth until an outcome event (ie, psychotic or bipolar disorder), death, emigration or end of follow-up, whichever came first. Data from different registers were linked for each individual via a unique personal identification code assigned to Finnish citizens and residents by the Digital and Population Data Services Agency (formerly known as the Central Population Register). For the current study, data were used from the Medical Birth Register for sex, date of birth, and perinatal health; the Care Register for Health Care (formerly known as the Hospital Discharge Register) for dates of inpatient and outpatient visits to public hospital clinics and corresponding diagnoses14; and Statistics Finland for dates and causes of death; the Digital and Population Data Services Agency for residential location and emigration data.

Data on self-harm, psychotic or bipolar disorders were based on diagnoses recorded in the Care Register for Health Care, which includes all hospital inpatient care and outpatient visits at public hospitals. The records include the start and end dates of the visits, a mandatory primary diagnosis, and as many as three optional secondary diagnoses. The register contains hospital outpatient and most emergency room data since 1998, and thus covers a large part of the whole study follow-up, including peak incidence periods of self-harm and outcome diagnoses. Data are gathered continuously and submitted to the register by Finnish hospital districts as part of clinical practice, and coverage of registered diagnoses can be considered near-complete.14 The Finnish register has been widely used in recent years,15,16 and studies have shown high validity for register-based diagnoses of bipolar disorder,14,17 and psychotic disorders.14,18

Psychiatric Phenotypes Definitions

Hospital Presentation for Self-Harm

In the Finnish Care Register for Health Care, self-harm was coded with the Finnish national modification of ICD-10 diagnostic codes X60 to X84 (table ST1), in line with previous work.19,20 These diagnostic codes are principally used for hospital emergency department settings (as opposed to, for example, psychiatric hospital settings). Data were used from primary and secondary diagnosis records as well as from records on external reasons for physical harm (eg, “intentional self-harm by a sharp object” when the primary diagnosis was an “open wound of forearm”).

Psychotic and Bipolar Disorders

The outcome diagnoses were approached from a hierarchical perspective. Psychotic disorders comprised schizophrenia (ICD-9 codes 2951A, 2952A, 2954A, 2959A, and ICD 10 codes F20.0 to F20.9), other non-affective psychoses (ICD-9 codes 2971A, 2973A, 2988A, 2989X, and ICD-10 codes F22, F23, F24, F25, F28, and F29), and affective psychosis (ICD-9 code 2957A and 2961E and ICD-10 codes F30.2, F31.2, and F31.5, F32.3, and F33.3). Bipolar disorder was separated into without psychotic symptoms (ICD-9 codes 2962A, 2962B, 2962D, 2963B, 2963D, 2964G, 2967A, and ICD-10 codes F30, F30.1, F30.9, F30.9, F31.0, F31.1, F31.3, F31.4, F31.6, F31.8, and F31.9) and with psychotic symptoms (ICD-9 code 2963E, and ICD-10 codes F30.2, F31.2, and F31.5). There was some overlap in diagnostic codes between affective psychosis and bipolar disorder with psychotic features, which allows for comparison with their respective higher-order diagnostic categories (tables ST1 and ST2).

Statistical Analyses

Lifetime prevalence until age 28 years of hospital presentations with self-harm is presented in percentages, and χ2-difference testing was used to explore associations with sex. Odds ratios were calculated to assess the relationship between lifetime histories of self-harm, psychotic or bipolar disorder.

The prospective (and potentially bidirectional) associations between diagnoses of self-harm and diagnoses of psychotic or bipolar disorder were described using percentages, and the effect of the associations were quantified as hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on Cox proportional hazards models. The age of the study subjects was used for the time scale the Cox models, which is in line with previous research.15,20 First, to assess the prospective association of first presentation with self-harm with later diagnoses of psychotic and bipolar disorder, we used the full cohort, but excluded those who had an incident psychotic or bipolar disorder diagnosis, respectively, prior to presentation with self-harm. Second, to assess lifetime diagnoses of psychotic or bipolar disorder in relation to later diagnoses of self-harm, we used the full cohort, but excluded those who had incident self-harm prior to diagnoses of psychotic or bipolar disorder. All analyses were stratified by sex. No other sociodemographic variables were included in the model to comply with a predictive (ie, noncausal) approach.

Secondary analyses were conducted to assess risk for psychotic/bipolar disorder associated with self-harm in childhood and adolescence versus adulthood, specifically for self-harm presentations that first occurred before age 18 years, between 18 and 21 years, and after 21 years. We also examined the differential risk for psychotic or bipolar disorder for individuals with single versus multiple self-harm presentations. We then analysed whether there were differential associations of self-poisoning versus other methods of self-harm in relation to subsequent psychotic or bipolar disorder.

Next, time-to-event analyses were conducted to examine the median time from self-harm presentation to a first diagnosis of psychotic or bipolar disorder. This provided information on the potential time for intervention for individuals who have presented to health services with self-harm but who have not been diagnosed with (ie, untreated for) psychotic or bipolar disorder. Secondary analyses were carried out to look at the effect of age at first presentation with self-harm, again divided into self-harm presentations that first occurred before age 18 years, between 18 and 21 years, and after 21 years. All analyses were performed in Stata version 14.2.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Of 59 476 individuals included in the cohort, n = 481 (0.8%) had a lifetime history of hospital presentation for self-harm (Table ST1 and ST3). Hospital self-harm presentations were more prevalent in females than males (261 [0.9%] vs 220 [0.7%), χ2 = 5.7, df = 1, P = .02), and n = 177 (36.8%) of individuals presented more than once. Age at first presentation with self-harm followed a bi-modal distribution with a peak around ages 20 and 27 years. N = 1445 (2.4%) were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, and n = 51 (3.5%) were preceded by hospital self-harm presentation. N = 770 (1.3%) were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and n = 43 (5.6%) were preceded by hospital self-harm presentation.

Lifetime Association of Self-Harm Presentations With Psychotic or Bipolar Disorders

Lifetime history (until age 28 years) of self-harm and lifetime history of psychotic disorder co-occurred in n = 132 individuals (OR = 16.6). Likewise, lifetime history of self-harm and lifetime history of bipolar disorder co-occurred in n = 76 individuals (OR = 15.7).

Risk of Psychotic or Bipolar Disorders in Individuals With a History of Self-Harm

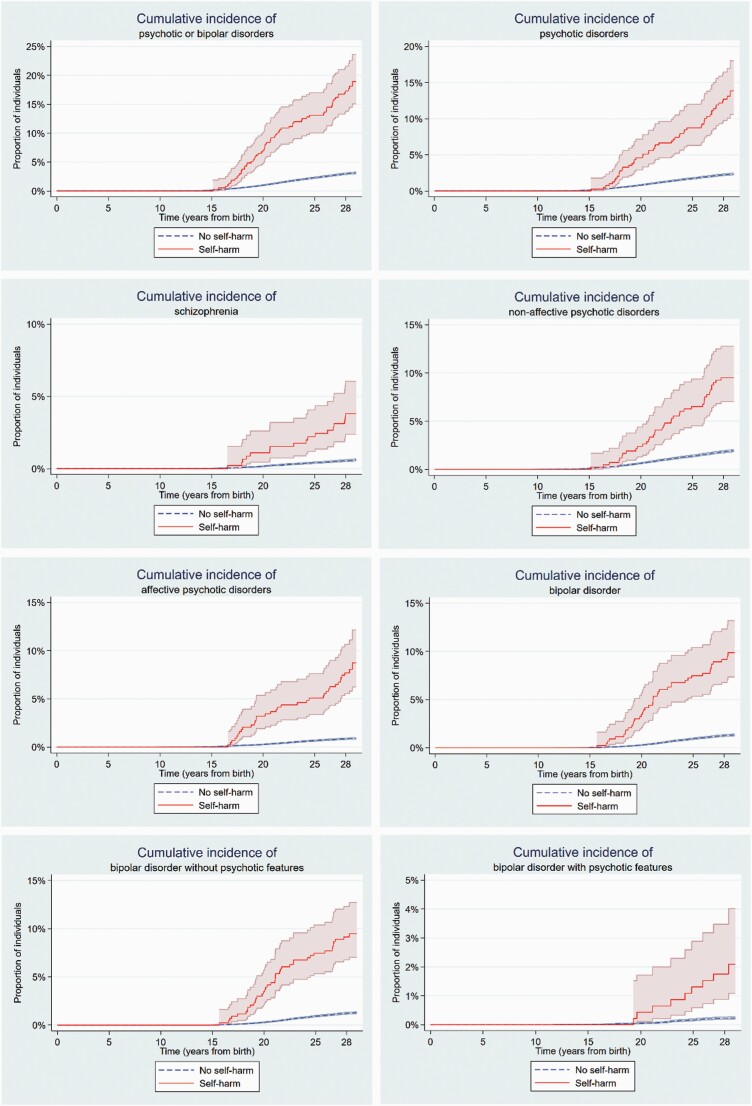

Of the individuals who presented to hospital with self-harm (but who did not have a prior diagnosis of psychotic or bipolar disorder), 66 individuals (17.7%) went on to be subsequently diagnosed with a psychotic or bipolar disorder (figure 1 and table 1; HR = 6.45, 95% 5.05–8.25).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence curves for the eight individual outcomes.

Table 1.

Bidirectional Associations Between Self-Harm and Serious Mental Illness Diagnosis

| (A) Self-Harm to Subsequent Psychotic/Bipolar Disorder | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Population | Females | Males | ||||

| Outcome Diagnosis | N (%)a | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) |

| Any psychotic or bipolar disorder | 66 (17.7) | 6.45 (5.05–8.25) | 44 (22.5) | 7.69 (5.68–10.40) | 22 (12.4) | 4.84 (3.17–7.39) |

| Any psychotic disorder | 51 (12.8) | 6.03 (4.56–7.98) | 32 (15.0) | 7.18 (5.03–10.24) | 19 (10.3) | 4.76 (3.02–7.51) |

| - Schizophrenia | 17 (3.7) | 6.71 (4.12–10.94) | 8 (3.2) | 7.14 (3.49–14.60) | 9 (4.2) | 6.57 (3.36–12.84) |

| - Other non-affective psychosis | 39 (9.1) | 5.20 (3.78–7.16) | 26 (11.1) | 6.90 (4.65–10.25) | 13 (6.7) | 3.54 (2.04–6.14) |

| - Affective psychosis | 35 (7.9) | 9.66 (6.85–13.62) | 22 (9.4) | 9.33 (6.05–14.41) | 13 (6.3) | 9.81 (5.59–17.23) |

| Any bipolar disorder | 41 (9.4) | 7.85 (5.73–10.76) | 32 (13.9) | 8.82 (6.17–12.63) | 9 (4.4) | 5.41 (2.78–10.53) |

| - Without psychotic features | 40 (9.1) | 7.93 (5.76–10.91) | 31 (13.4) | 8.77 (6.10–12.63) | 9 (4.3) | 5.71 (2.93–11.12) |

| - With psychotic features | 9 (1.9) | 8.65 (4.40–17.03) | 8 (3.1) | 12.08 (5.81–25.10) | 1 (0.5) | 2.53 (0.35–18.28) |

| (B) Psychotic/Bipolar Disorder to Subsequent Self-Harm | ||||||

| Overall Population | Females | Males | ||||

| Exposure Diagnosis | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) |

| Any psychotic or bipolar disorder | 107 (5.8) | 17.58 (14.59–21.18) | 65 (6.5) | 19.96 (15.60–25.52) | 42 (5.0) | 14.57 (10.89–19.49) |

| Any psychotic disorder | 83 (6.0) | 16.18 (13.26–19.75) | 48 (7.1) | 18.41 (14.15–23.95) | 35 (4.9) | 13.74 (10.10–18.68) |

| - Schizophrenia | 16 (5.0) | 13.39 (9.40–19.07) | 11 (8.2) | 16.86 (10.57–26.89) | 5 (2.7) | 10.80 (6.29–18.56) |

| - Other non-affective psychosis | 54 (5.1) | 13.34 (10.64–16.73) | 27 (5.6) | 15.03 (11.12–20.32) | 27 (4.7) | 11.77 (8.36–16.59) |

| - Affective psychosis | 40 (8.0) | 21.57 (16.86–27.59) | 28 (9.1) | 22.00 (16.17–29.95) | 12 (6.2) | 19.75 (13.02–29.95) |

| Any bipolar disorder | 43 (5.9) | 17.09 (13.50–21.63) | 30 (6.1) | 17.94 (13.49–23.86) | 13 (5.4) | 14.39 (9.26–22.36) |

| - Without psychotic features | 42 (6.0) | 17.21 (13.57–21.82) | 30 (6.3) | 18.02 (13.53–24.00) | 12 (5.3) | 14.48 (9.23–22.70) |

| - With psychotic features | 7 (5.5) | 15.95 (9.69–26.26) | 4 (5.4) | 18.34 (10.28–23.73) | 3 (5.6) | 10.81 (4.02–29.07) |

Note: Panel A: prospective relationships of self-harm (exposure) with subsequent psychotic and bipolar disorders (outcome); and Panel B: Prospective relationships of psychotic and bipolar disorder (exposure) with subsequent self-harm (outcome).

aThe percentages reflect the proportion of individuals with exposure diagnosis who were subsequently diagnosed with an outcome diagnosis, for example, 17 out of 465 (3.7%) individuals with self-harm were later diagnosed with schizophrenia (NB: individuals with a first diagnosis of schizophrenia before a first presentation with self-harm were excluded). Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratio.

A total of 51 (12.8%) individuals who presented to hospital with self-harm went on to be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder (figure 1 and table 1; HR = 6.03, 95% CI 4.56–7.98), including n = 17 (3.7%) with schizophrenia, n = 39 (9.1%) with other nonaffective psychoses, and n = 35 (7.9%) with affective psychosis. Hazard ratios were similar across psychotic diagnostic categories, except for a higher estimate for affective psychosis (HR = 9.66, 95% CI 6.85–13.62).

A total of 41 (9.4%) individuals who presented to hospital with self-harm went on to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder (figure 1 and table 1; HR = 7.85, 95% CI 5.73–10.76), including n = 40 (9.1%) with bipolar disorder without psychotic symptoms and n = 9 (1.9%) with bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms.

While the hazard ratios were higher for women than men, the confidence intervals were overlapping for all psychotic and bipolar disorder outcomes (eg, HRfemale = 7.18, 95% CI 5.03–10.24 vs HRmale = 4.76, 95% CI 3.02–7.51, respectively, in the case of psychotic disorders).

Risk of Self-Harm in Individuals Diagnosed With Psychotic or Bipolar Disorders

In keeping with previous studies, there was an increased hazards of self-harm presentations in individuals who had been diagnosed with psychotic or bipolar disorders. In total, 83 individuals with psychotic (6.0%) and 43 individuals with bipolar disorders (5.9%) diagnoses presented to hospital with subsequent self-harm over the course of follow up (table 1; HR = 16.18, 95% CI 13.26–19.75, and HR = 17.09, 95% CI 13.50–21.63, respectively). Individuals who had a self-harm presentation prior to a first psychotic or bipolar disorder diagnosis were excluded from these analyses.

Secondary Analyses

Younger age group at first presentation with self-harm was associated with a greater risk for psychotic or bipolar disorders (table 2 and Supplementary figure ST1). Specifically, 10.4% of individuals who first presented with self-harm after age 21 years went on to be diagnosed with psychotic or bipolar disorders by age 28, whereas this was the case for 20.8% of individuals who presented with self-harm for the first time between 18 and 21 years and 29.1% of individuals who presented with self-harm for the first time before age 18 years. Sensitivity analyses which included self-harm presentations associated with inpatient admission (versus, for example, treatment and discharge from Emergency Department without inpatient admission), yielded similar proportions, that is, 14.0%, 20.8% and 29.4%, respectively, and similar hazard ratios (table ST4).

Table 2.

Association of Self-Harm (Exposure) with Subsequent Psychotic and Bipolar Disorders (Outcome), Stratified by Age at First Self-Harm

| Total Population | Females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Outcome: any psychotic or bipolar disorder | ||||||

| <18 years | 25 (29.1) | 12.43 (8.37–18.44) | 21 (33.9) | 13.38 (8.68–20.62) | 4 (16.7) | 7.42 (2.78–19.81) |

| 18–21 years | 22 (20.8) | 8.13 (5.34–12.39) | 14 (23.7) | 8.50 (5.01–14.41) | 8 (17.0) | 7.31 (3.65–14.68) |

| >21 years | 19 (10.4) | 3.45 (2.19–5.42) | 9 (12.00) | 3.59 (1.86–6.93) | 10 (9.4) | 3.43 (1.84–6.40) |

| Outcome: any psychotic disorder | ||||||

| <18 years | 19 (21.4) | 11.74 (7.46–18.47) | 15 (24.2) | 12.89 (7.73–21.51) | 4 (16.8) | 8.78 (3.29–23.47) |

| 18–21 years | 16 (12.0) | 7.03 (4.30–11.52) | 10 (15.9) | 7.73 (4.14–14.44) | 6 (12.5) | 6.12 (2.74–13.67) |

| >21 years | 16 (6.2) | 3.51 (2.14–5.75) | 7 (8.0) | 3.50 (1.66–7.37) | 9 (8.0) | 3.52 (1.82–6.79) |

| Outcome: schizophrenia | ||||||

| < 18 years | 9 (10.1) | 19.90 (10.26–38.63) | 8 (12.5) | 30.19 (14.76–61.73) | 1 (4.0) | 6.62 (0.93–47.27) |

| 18–21 years | 1 (0.8) | 1.45 (0.20–10.31) | 0 (0.0) | NA | 1 (1.8) | 2.89 (0.40–20.59) |

| > 21 years | 7 (2.8) | 5.04 (2.38–10.66) | 0 (0.0) | NA | 7 (5.2) | 8.03 (3.77–17.08) |

| Outcome: Other non-affective psychosis | ||||||

| <18 years | 13 (14.9) | 9.14 (5.29–15.80) | 10 (15.9) | 10.4 (5.57–19.49) | 4 (12.5) | 7.27 (2.34–22.60) |

| 18–21 years | 14 (11.6) | 6.90 (4.07–11.70) | 8 (11.3) | 7.28 (3.62–14.65) | 6 (12.0) | 6.66 (2.98–14.89) |

| >21 years | 12 (5.5) | 2.97 (1.68–5.24) | 8 (8.00) | 4.68 (2.33–9.42) | 3 (3.4) | 1.70 (0.63–4.54) |

| Outcome: Affective psychosis | ||||||

| <18 years | 11 (12.6) | 16.54 (9.09–30.07) | 10 (16.1) | 17.29 (9.20–32.49) | 1 (4.0) | 6.53 (0.92–46.64) |

| 18–21 years | 10 (8.2) | 10.34 (5.53–19.35) | 6 (8.8) | 8.87 (3.95–19.92) | 4 (7.4) | 12.36 (4.59–33.28) |

| >21 years | 14 (6.0) | 7.03 (4.13–11.97) | 6 (5.8) | 5.44 (2.43–12.22) | 8 (6.2) | 9.43 (4.65–19.15) |

| Outcome: any bipolar disorder | ||||||

| <18 years | 14 (15.7) | 14.18 (8.35–24.06) | 13 (20.3) | 13.66 (7.87–23.71) | 1 (4.0) | 5.29 (0.74–37.75) |

| 18–21 years | 17 (13.8) | 12.57 (7.77–20.33) | 14 (20.0) | 13.84 (8.13–23.56) | 3 (5.7) | 7.57 (2.42–23.63) |

| >21 years | 10 (4.4) | 3.47 (1.86–6.48) | 5 (5.2) | 3.01 (1.25–7.26) | 5 (3.9) | 4.63 (1.91–11.24) |

| Outcome: bipolar disorder without psychotic features | ||||||

| <18 years | 13 (14.6) | 13.65 (7.89–23.64) | 12 (18.8) | 12.94 (7.29–22.95) | 1 (4.0) | 5.62 (0.79–40.05) |

| 18–21 years | 17 (13.8) | 13.02 (8.05–21.08) | 14 (20.0) | 14.20 (8.94–24.17) | 3 (5.7) | 8.02 (2.57–25.07) |

| >21 years | 10 (4.4) | 3.59 (1.92–6.70) | 5 (5.2) | 3.09 (1.28–7.46) | 5 (3.9) | 4.88 (2.01–11.84) |

| Outcome: bipolar disorder with psychotic features | ||||||

| <18 years | 2 (2.3) | 10.28 (2.54–42.56) | 2 (3.1) | 12.00 (2.94–48.94) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| 18–21 years | 2 (1.5) | 7.23 (1.79–29.24) | 2 (2.6) | 10.56 (2.59–43.06) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| >21 years | 5 (2.0) | 8.79 (3.59–21.50) | 4 (3.4) | 13.06 (4.77–35.77) | 1 (0.7) | 3.91 (0.54–28.29) |

Note: Reference group is individuals who did not present with self-injurious behaviour. Individuals with a first diagnosis of the respective outcome diagnosis before a first presentation with self-harm were excluded. Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratio.

Multiple presentations with self-harm were associated with a similar risk of psychotic or bipolar disorders as single presentations (19.7% vs 16.6%, see table 3). Self-harm through self-poisoning was associated with a similar risk of psychotic or bipolar disorders as self-harm through other methods (19.1% vs 17.3%, see table 4).

Table 3:

Association of Self-Harm (Exposure) With Subsequent Psychotic and Bipolar Disorders (Outcome), Stratified Number of Self-Harm Presentations

| Total Population | Females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Outcome: any psychotic or bipolar disorder | ||||||

| Single | 41 (16.0) | 6.16 (4.52–8.39) | 25 (20.0) | 6.91(4.65–10.29) | 16 (13.1) | 5.25 (3.20–8.62) |

| Multiple | 25 (19.7) | 7.01 (4.72–10.40) | 19 (26.8) | 9.02 (5.73–14.21) | 6 (10.7) | 3.99 (1.79–8.92) |

| Outcome: any psychotic disorder | ||||||

| Single | 29 (11.2) | 5.28 (3.65–7.62) | 15 (11.2) | 5.34 (3.20–8.91) | 14 (11.11) | 5.22 (3.07–8.86) |

| Multiple | 22 (15.9) | 7.44 (4.88–11.35) | 17 (21.5) | 10.31 (6.37–16.69) | 5 (8.5) | 3.82 (1.58–9.20) |

| Outcome: schizophrenia | ||||||

| Single | 8 (2.7) | 5.00 (2.48–10.09) | 3 (2.0) | 4.40 (1.40–13.84) | 5 (3.5) | 5.55 (2.28–13.49) |

| Multiple | 9 (5..3) | 9.66 (4.98–18.75) | 5 (5.2) | 11.39 (4.66–27.85) | 4 (5.6) | 8.55 (3.17–23.03) |

| Outcome: oOther non-affective psychosis | ||||||

| Single | 22 (8.0) | 4.60 (3.01–7.02) | 13 (9.0) | 5.65 (3.26–9.81) | 9 (6.9) | 3.65 (1.89–7.06) |

| Multiple | 17 (11.3) | 6.27 (3.88–10.13) | 13 (14.) | 8.86 (5.11–15.38) | 4 (6.5) | 3.31 (1.24–8.85) |

| Outcome: affective psychosis | ||||||

| Single | 19 (6.8) | 8.28 (5.24–13.10) | 10 (7.0) | 6.98 (3.71–13.11) | 9 (6.5) | 10.27 (5.26–20.06) |

| Multiple | 16 (10.0) | 12.04 (7.32–19.82) | 12 (13.2) | 12.99 (7.29–23.15) | 4 (5.8) | 8.92 (3.31–24.01) |

| Outcome: any bipolar disorder | ||||||

| Single | 26 (9.1) | 7.76 (5.25–11.48) | 19 (14.2) | 8.48 (5.36–13.42) | 7 (5.0) | 6.31 (2.98–13.39) |

| Multiple | 15 (9.8) | 8.02 (4.81–13.38) | 13 (14.9) | 9.38 (5.40–16.27 | 2 (3.0) | 3.60 (0.90–14.49) |

| Outcome: bipolar disorder without psychotic features | ||||||

| Single | 26 (9.1) | 8.05 (5.44–11.91) | 19 (13.2) | 8.71 (5.50–13.78) | 7 (5.0) | 6.69 (3.15–14.21) |

| Multiple | 14 (9.1) | 7.72 (4.55–13.11) | 12 (13.8) | 8.89 (5.01–15.76) | 2 (3.0) | 3.77 (0.94–15.15) |

| Outcome: bipolar disorder with psychotic features | ||||||

| Single | 3 (1.0) | 4.56 (1.45–14.34) | 2 (1.3) | 5.00 (1.23–20.39) | 1 (0.7) | 3.79 (0.52–27.42) |

| Multiple | 3 (3.5) | 15.69 (6.91–35.62) | 6 (5.9) | 22.87 (9.94–52.66) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

Note: Reference group is individuals who did not present with self-injurious behaviour. Individuals with a first diagnosis of the respective outcome diagnosis before a first presentation with self-harm were excluded. Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 4.

Association of Self-Harm (Exposure) With Subsequent Psychotic and Bipolar Disorders (Outcome), Stratified by Method of Self-Harm

| Total Population | Females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | N (%) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Outcome: any psychotic or bipolar disorder | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 53 (17.3) | 6.32 (4.81–8.30) | 36 (21.3) | 7.25 (5.20–10.11) | 17 (12.4) | 4.84 (2.99–7.82) |

| Other | 13 (19.1) | 7.09 (4.11–12.24) | 8 (29.6) | 10.57 (5.27–21.21) | 5 (12.2) | 4.84 (2.01–11.65) |

| Outcome: any psychotic disorder | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 41 (12.6) | 5.92 (3.34–8.07) | 26 (14.2) | 6.80 (4.59–10.06) | 15 (10.6) | 4.84 (2.90–8.07) |

| Other | 10 (13.7) | 6.57 (3.53–12.24) | 6 (20.0) | 9.50 (4.25–21.22) | 4 (9.3) | 4.48 (1.68–11.97) |

| Outcome: schizophrenia | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 12 (3.2) | 5.79 (3.23–10.25) | 6 (2.8) | 6.20 (2.73–14.07) | 6 (3.6) | 5.65 (2.50–12.74) |

| Other | 5 (6.0) | 11.16 (4.61–27.02) | 2 (5.9) | 13.06 (3.23–52.81) | 3 (6.0) | 12.77 (3.12–30.58) |

| Outcome: other non-affective psychosis | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 34 (9.7) | 5.53 (3.93–7.78) | 22 (10.9) | 6.81 (4.44–10.45) | 12 (8.1) | 4.21 (2.37–7.45) |

| Other | 5 (6.6) | 3.72 (1.55–8.96) | 4 (12.5) | 7.44 (2.78–19.90) | 1 (2.3) | 1.22 (0.17–8.68) |

| Outcome: affective psychosis | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 27 (7.5) | 9.07 (6.15–13.36) | 18 (9.0) | 8.85 (5.50–14.26) | 9 (5.7) | 8.74 (4.48–17.08) |

| Other | 8 (9.9) | 12.41 (6.19–24.97) | 4 (12.5) | 12.37 (4.61–33.19) | 4 (8.2) | 13.54 (5.03–36.45) |

| Outcome: any bipolar disorder | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 34 (9.5) | 7.98 (5.66–11.26) | 26 (13.1) | 8.29 (5.58–12.30) | 8 (5.1) | 6.29 (3.11–12.73) |

| Other | 7 (8.6) | 7.29 (3.46–15.35) | 6 (18.8) | 12.28 (5.49–27.48) | 1 (2.0) | 2.55 (0.36–18.17) |

| Outcome: bipolar disorder without psychotic features | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 33 (9.2) | 8.01 (5.65–11.37) | 12 (12.6) | 8.18 (5.47–12.23) | 8 (5.0) | 6.63 (3.27–13.42) |

| Other | 7 (8.6) | 7.57 (3.59–15.93) | 6 (18.8) | 12.61 (5.63–28.21) | 1 (2.0) | 2.70 (0.38–19.29) |

| Outcome: bipolar disorder with psychotic features | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 9 (2.3) | 10.59 (5.38–20.85) | 8 (3.6) | 14.15 (6.81–29.40) | 1 (0.6) | 3.26 (0.45–23.62) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | NA | 0 (0.0) | NA | 0 (0.0) | NA |

Note: Reference group is individuals who did not present with self-injurious behaviour. Individuals with a first diagnosis of the respective outcome diagnosis before a first presentation with self-harm were excluded. Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratio.

Time From Self-Harm to First Diagnosis of Psychotic or Bipolar Disorders

After a first presentation of self-harm, the median time to diagnosis with a psychotic disorder was 0.75 years (table ST5; interquartile range [IQR] 0.13–3.62) and median time to diagnosis with bipolar disorder was 1.79 years (IQR 0.60–4.13). Median time to schizophrenia was substantially longer than for other outcome diagnoses: 3.07 years (IQR 1.36–4.64). Median time to affective psychosis was relatively shorter: 0.32 years (IQR 0.03–1.62).

Discussion

In this total population study of individuals born in Finland in 1987, approximately 18% of all persons who presented to hospital with an incident of self-harm between ages 11 and 28 years went on to be diagnosed with a psychotic or bipolar disorder. Younger individuals were at particularly high risk: for individuals aged 18−21 years at their first self-harm presentation, 21% went on to be subsequently diagnosed with a psychotic or bipolar disorder. For individuals under age 18 years at their first presentation, 29% went on to be subsequently diagnosed with a psychotic or bipolar disorder. Risk was similarly high whether there were single or multiple self-harm presentations.

It is important to emphasise that the high risk for psychotic and bipolar disorders reported in this study is not related to self-harm per se but, rather, to contact with a specific clinical pathway associated with self-harm, that is the pathway of self-harm hospital presentation. Self-harm is relatively common in the general population, with only a small proportion of cases presenting to hospital: a recent meta-analysis, for example, found that fewer than 1 in 10 adolescents who self-harmed had presented to hospitals for their injuries.21 There are likely many differences between population-level self-harm and hospital presentations for self-harm, including the severity of injury, motivating factors for self-harm, and associated levels of distress.21,22 Therefore, as opposed to considering young people who self-harm as being at high risk of psychosis and bipolar disorder, it is important to be clear that our results identify contact with a specific clinical pathway indicates high risk for psychosis and bipolar disorder. In other words, existing health care systems (ie, hospital registrations for self-harm) can be used as a strategy to identify individuals at elevated risk for psychosis and bipolar disorder.

The interquartile range for time from hospital self-harm presentation to psychosis or bipolar diagnosis was 0.13−3.62 years. For schizophrenia specifically, the interquartile range was longer at 1.36–4.64 years. This time to diagnosis appears to longer than in “At Risk Mental State” (ARMS), “Clinical High Risk” (CHR) or “Ultra-High Risk” (UHR) populations, which represents an important clinical window in which to intervene to delay or prevent the onset of psychosis or mania. Frequently, presentations of young people to hospitals with self-harm are formulated as psychosocial “crises,” rather than being considered potential indicators of risk for serious neuropsychiatric illness.21 Indeed, hospital self-harm presentations frequently do not lead to a psychiatric assessment or referral to community mental health teams; instead, at present, many young people who present to hospital with self-harm are re-directed to other supports.23 Future service use research should explore what commonly happens to individuals who present to hospital with self-harm, that is, admission to a psychiatric ward, other psychiatric follow-up, diagnosis and treatment, and how these relate to prognosis. Our findings suggest that young people presenting to hospital emergency departments with self-harm should be carefully assessed for psychotic or bipolar disorders. Given that the level of risk for psychosis is comparable to that of a diagnosis of an ARMS, CHR or UHR,24,25 a similar degree of psychiatric follow-up may be warranted as would occur with an ARMS, CHR or UHR diagnosis, which typically includes specialist psychosis assessment and up to 3 years of follow up in specialist mental health services.26

Several mechanisms could potentially explain the prospective association between hospital presentations for self-harm and subsequent psychotic or bipolar disorders. An overarching explanation is that the same neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities and environmental exposures (eg, trauma and violence exposure) that predispose to risk of psychosis or mania may also increase risk for self-harm,10,11,27 with self-harm emerging, in some cases, prior to the onset of formal symptoms of psychosis or mania.28,29 Similarly, several studies have highlighted the role of mood symptoms as important early manifestations of developmental risk for psychotic as well as bipolar disorders.9,10,30–33 For this reason, hospital presentation for self-harm may act as a marker of neurodevelopmental risk for psychosis. Importantly, it may also be the case that the combination of self-harm and neurodevelopmental features makes hospital presentation more likely than when self-harm occurs outside of the context of neurodevelopmental risk. Further research will be needed to understand the causal factors underlying the relationship.

Strengths of this study include its large, whole-population approach, which rules out problems arising from representativeness of study samples – this study involved not just a sample of individuals born in 1987 but the total population born in 1987. The register-based approach means there is no loss to follow up as typically occurs in longitudinal research. The use of hospital registers provides ecological validity in that it identifies the individuals who present to hospital looking for help after having self-harmed as well as individuals who have actually been diagnosed with and received treatment for psychosis or bipolar disorder in the population. What is more, research has shown a high degree of accuracy for register diagnoses of psychotic and bipolar disorders.14,17,18 A limitation is that, although we had a long follow up period, the follow up ended in 2015 when participants were 28 years old. Given that 28 years of age is not yet past the age of highest risk, our findings likely represent an underestimation of the true risk for psychotic or bipolar disorders—that is, it is likely that, ultimately, a higher percentage would go on to develop psychosis or bipolar disorder. Second, international replication will be needed to determine if the current results are equally applicable to other countries, though it should be noted that the prevalence of self-harm in Finnish youths is similar to that in other Western countries.21,34 Third, we have conducted a large number of secondary analyses and this may have increased the likelihood of false positive results. However, our analyses were performed in an hierarchical, step-wise manner.

Conclusions

This total population study shows that hospital presentation for self-harm in youth is a strong risk marker for later psychosis and bipolar disorder. A strength of this approach is that it points to a readily-identifiable clinical population at high risk for psychosis/bipolar disorder without the need for additional facilities or structured (symptomatic) assessments which are required in existing psychosis/bipolar risk approaches. This should facilitate the use of this new (system-based) high risk approach, which can complement existing (symptom-based) high riskapproaches,9,11,24,25 highlighting new opportunities for the prevention of serious mental disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None Declared.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sophia Research Fund (fellowship 921 to K.B.); the Health Research Board (Ireland; ECSA-2020-05 to I.K.); the St John of God Research Foundation (project grant to I.K.); the Academy of Finland (297598 to D.G.). This work was partially funded by Academy of Finland as a project (288960 to A.K.), Flagship Programme (320162 to A.K.), and Health from Cohorts and Biobanks Programme (308552 to A.K.). Ms Lång was supported by a Strategic Academic Recruitment (StAR) award to Dr Kelleher from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Data are held at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) and Permission to use data is applied via Health and Social Data Permit Authority Findata or THL depending on the case. Web link: https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/statistics/data-and-services

Requests for study protocols and analysis plans can be made through contacting the first and last author (KB and IK). Funders were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox, oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien. Leipzig: Deuticke; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lu L, Dong M, Zhang L, Zhu XM, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Wang G, Xiang YT. Prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29(E39):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dong M, Lu L, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29(E63):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cassidy RM, Yang F, Kapczinski F, Passos IC. Risk factors for suicidality in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 96 Studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(4):787–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DeVylder JE, Ryan TC, Cwik M, et al. Screening for suicide risk among youths with a psychotic disorder in a pediatric emergency department. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(2):205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murphy J, Shevlin M, Hyland P, et al. Reconsidering the association between psychosis and suicide: a suicidal drive hypothesis. Psychosis: Psychological, Social and Integrative Approaches; 2018, Oct Psychosis 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sullivan SA, Hamilton W, Tilling K, Redaniel T, Moran P, Lewis G. Association of primary care consultation patterns with early signs and symptoms of psychosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e185174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Meter AR, Burke C, Youngstrom EA, Faedda GL, Correll CU. The Bipolar prodrome: meta-analysis of symptom prevalence prior to initial or recurrent mood episodes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(7):543–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cannon M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, et al. Evidence for early-childhood, pan-developmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(5):449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bridgwater M, Bachman P, Tervo-Clemmens B, et al. Developmental influences on symptom expression in antipsychotic-naive first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2020:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paananen R, Gissler M. Cohort profile: the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(4):941–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ombudsman OotDP. Pseudonymised and anonymised data. Available at: https://tietosuoja.fi/en/pseudonymised-and-anonymised-data2020.

- 14. Sund R. Quality of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(6):505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gyllenberg D, Marttila M, Sund R, et al. Temporal changes in the incidence of treated psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders during adolescence: an analysis of two national Finnish birth cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(3):227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Merikukka M, Ristikari T, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Gissler M, Laaksonen M. Childhood determinants for early psychiatric disability pension: a 10-year follow-up study of the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018:20764018806936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kieseppä T, Partonen T, Kaprio J, Lönnqvist J. Accuracy of register- and record-based bipolar I disorder diagnoses in Finland; a study of twins. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2000;12(3):106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pihlajamaa J, Suvisaari J, Henriksson M, et al. The validity of schizophrenia diagnosis in the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register: findings from a 10-year birth cohort sample. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62(3):198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klomek AB, Sourander A, Niemelä S, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(3):254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sourander A, Ronning J, Brunstein-Klomek A, et al. Childhood bullying behavior and later psychiatric hospital and psychopharmacologic treatment: findings from the Finnish 1981 birth cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(9):1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gillies D, Christou MA, Dixon AC, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of self-harm in adolescents: meta-analyses of community-based studies 1990–2015. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;57(10):733–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(2):187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hawton K, Witt KG, Salisbury TLT, et al. Psychosocial interventions following self-harm in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):740–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fusar-Poli P, Rutigliano G, Stahl D, et al. Development and validation of a clinically based risk calculator for the transdiagnostic prediction of psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hafeman DM, Merranko J, Goldstein TR, et al. Assessment of a person-level risk calculator to predict new-onset bipolar spectrum disorder in youth at familial risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(8):841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178. [PubMed]

- 27. Murray RM, Bhavsar V, Tripoli G, Howes O. 30 Years on: how the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia morphed into the developmental risk factor model of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(6):1190–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sokolowski M, Wasserman J, Wasserman D. Polygenic associations of neurodevelopmental genes in suicide attempt. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(10):1381–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hielscher E, DeVylder JE, Saha S, Connell M, Scott JG. Why are psychotic experiences associated with self-injurious thoughts and behaviours? A systematic review and critical appraisal of potential confounding and mediating factors. Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1410–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Häfner H, Maurer K, Löffler W, et al. The ABC schizophrenia study: a preliminary overview of the results. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33(8):380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hafner H, Maurer K, an der Heiden W. ABC Schizophrenia study: an overview of results since 1996. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(7):1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mesman E, Nolen WA, Reichart CG, Wals M, Hillegers MH. The Dutch bipolar offspring study: 12-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(5):542–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ, Marangoni C, et al. An international society of bipolar disorders task force report: precursors and prodromes of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(8):720–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, Plener PL. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012;6:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.