Abstract

Introduction

More than a century of research on the neurobiological underpinnings of major psychiatric disorders (major depressive disorder [MDD], bipolar disorder [BD], schizophrenia [SZ], and schizoaffective disorder [SZA]) has been unable to identify diagnostic markers. An alternative approach is to study dimensional psychopathological syndromes that cut across categorical diagnoses. The aim of the current study was to identify gray matter volume (GMV) correlates of transdiagnostic symptom dimensions.

Methods

We tested the association of 5 psychopathological factors with GMV using multiple regression models in a sample of N = 1069 patients meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for MDD (n = 818), BD (n = 132), and SZ/SZA (n = 119). T1-weighted brain images were acquired with 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging and preprocessed with CAT12. Interactions analyses (diagnosis × psychopathological factor) were performed to test whether local GMV associations were driven by DSM-IV diagnosis. We further tested syndrome specific regions of interest (ROIs).

Results

Whole brain analysis showed a significant negative association of the positive formal thought disorder factor with GMV in the right middle frontal gyrus, the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome in the right fusiform, and the left middle frontal gyri. ROI analyses further showed additional negative associations, including the negative syndrome with bilateral frontal opercula, positive formal thought disorder with the left amygdala-hippocampus complex, and the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome with the left angular gyrus. None of the GMV associations interacted with DSM-IV diagnosis.

Conclusions

We found associations between psychopathological syndromes and regional GMV independent of diagnosis. Our findings open a new avenue for neurobiological research across disorders, using syndrome-based approaches rather than categorical diagnoses.

Keywords: voxel-based morphometry, transdiagnostic, dimensional, major psychiatric disorders

Introduction

There is strong evidence that psychotic (schizophrenia [SZ] and schizoaffective disorder [SZA]—both henceforth referred as schizophrenia spectrum disorder [SSD]) and affective disorders (major depressive disorder [MDD] and bipolar disorder [BD]) (henceforth, together referred to as major psychiatric disorders) are overlapping regarding symptoms, course, and outcome.1,2 Neurobiological research showed that these major psychiatric disorders share familial and molecular genetic risk,3 environmental risks,4 structural brain changes,5–8 and other neurobiological markers.9 On a phenomenological level, the major psychiatric disorders share many syndromes such as depression, mania, and psychosis.10–12

Since research using diagnostic categories might overlook psychopathological mechanisms across disorders, transdiagnostic, dimensional approaches13–15 can serve as an important addition to traditional approaches comparing diagnostic groups. In studies on a shared psychopathological factor structure across SSD, MDD, and BD, 3–5 factors have been delineated.16–19 Most commonly paranoid-hallucinatory, depressive, negative, disorganized, and manic dimensions can be identified as separate dimensions.16,18,20 Confirmatory analyses of 6 competing factor models revealed that symptom dimensions are better represented by factor models including 4 or 5 factors rather than by models with fewer factors.17 In our own previous study, we cross-validated a 5-factor model comprising depression, negative syndrome, positive formal thought disorder (pFTD), paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome, and increased appetite across the major psychiatric disorders.2

For a long time,21 it has been hypothesized that particular syndromes might share a common brain structural network alteration, independent of the diagnostic category.1,5–7,22 But up to now, most studies investigating gray matter volume (GMV) alterations across disorders focused on categorical approaches.6,7 Using a multimodal machine learning approach aiming to classify recent onset psychosis and depression revealed no points of rarity on a brain structural level indicating comparable GMV across psychosis patients with comorbid depressive symptoms and patients with recent onset depression.8 This result is further supported by a study23 showing that specifically in patients with younger age disorder onset, neuroanatomical disease signatures fail to separate affective and psychotic disorders. Based on these findings, we aim to shed light on brain structural correlates of psychopathological factor dimensions across disorders. Below, we summarize results of previous voxel-based morphometry (VBM) studies on structural correlates of psychopathological factors. We focus on the neural substrates of the 5 psychopathological factors derived from our previous study.2

The paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome has mostly been investigated in studies including SZ patients. There is meta-analytical evidence that auditory verbal hallucinations are negatively correlated with GMV in the left insula and right superior temporal gyrus (STG).24 Further core regions25 negatively associated with the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome are the thalamus,26–28 the left planum temporale,29 left anterior cingulate, and the bilateral insulae.30,31

pFTD have been frequently associated with neuroanatomical alterations in the left STG, frontal opercula, and left middle temporal gyrus, (ie, Wernicke and Broca area).32,33 Dimensional analyses of pFTD in SZ patients showed negative associations in the bilateral inferior frontal gyri, the orbito-frontal cortex (OFC), the middle, medial, and superior frontal gyri, the left amygdala-hippocampus complex, the precuneus, and the insula.34,35

Meta-analyses of negative symptoms in SZ patients reported GMV reductions in the OFC, the anterior cingulate cortex, fusiform gyrus, thalamus, caudate, and amygdala associated with the severity of negative symptoms.36,37 However, results are heterogeneous. Some studies reported no association between GMV and negative symptoms on a whole brain level.38–40

Testing dimensional depressive symptomatology and GMV in MDD, there were correlations in the right OFC, the left hippocampal gyrus, and the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.41 Investigation of subclinical depressive symptoms in healthy populations revealed inconsistent associations in the anterior cingulate, OCF, and thalamus.42–44 Nevertheless, several studies found no associations between GMV and psychopathological measures in MDD patients.45–47

The psychopathological factor “increased appetite” from our phenomenological study has not been reported in previous factor analytical approaches.2 This dimension has only been reported within atypical MDD patients.48,49 One study investigating subtypes of MDD patients indicated that a severely increased appetite MDD subtype showed lower surface area in the anterior insula when compared to a healthy control group.50 Neurobiological research investigating obesity in otherwise healthy controls indicated the amygdala, hippocampus, insula, OFC, and the striatum to be central regions of appetite behavior.51,52 A study investigating MDD patients revealed lower temporo-frontal cortical thickness to be associated with obesity (body mass index > 30).53

In summary, most transdiagnostic GMV studies are limited by (1) results from studies comparing diagnostic categories (as opposed to dimensional investigations), or (2) dimensional psychopathological investigations restricted to 2 diagnostic groups, and/or by (3) investigating one psychopathological dimension not covering the whole psychopathological spectrum. To overcome these limitations, our aim was to investigate associations of psychopathological dimensions with GMV on a dimensional, transdiagnostic, data-driven level across MDD, BD, and SSD. Based on previous findings,5,6,8,23 we hypothesize that associations between psychopathological syndromes and local GMV that have previously been detected within one diagnosis, cut across MDD, BD, and SSD, and do not interact with diagnostic categories.

Materials and Methods

Participants

We included structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data of acute and remitted patients (aged 18–65) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria (SCID-I) for MDD (296.2X, 296.3X: n = 818, F = 530/M = 288), BD (292.5X, 292.6X, 292.7X, 296.0X, 296.4X, 296.5X, 296.6X, 296.7X, or 296.8X: n = 132, F = 71/M = 61), SZ (295.X: n = 74, F = 32/M = 42), and SZA (295.7: n = 45, F = 24/M = 21). This MRI sample is a subgroup of our previous study on psychopathological factors,2 from which, after quality checks of the brain scans n = 113 patients had to be excluded, leaving N = 1069 participants for the current analyses (see table 1). Patients were part of the DFG FOR2107 consortium54 and were interviewed and scanned at the Departments of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy Marburg or Münster Universities, Germany. In- and out-patients were recruited from these Universities and local psychiatric hospitals (Vitos Marburg, Gießen, Herborn, and Haina, LWL Münster, Germany) and via posting in local newspapers and flyers. Exclusion criteria were any history of neurological (head trauma or unconsciousness) and medical condition, substance dependence, current use of benzodiazepines, and IQ ≤80. The assessment of psychopathological symptoms and MRI data acquisition was performed within the same week. n = 341 patients (31.9%) did not receive any psychotropic medication, 53.5% received antidepressants, 12.1% mood stabilizers, and 29.6% antipsychotics at time of data collection. Based on DSM-IV criteria, n = 12 MDD (296.24, 296.34) patients and n = 6 BD (295.04, 296.44, 296.54) patients presented with psychotic features. A small number of participants were diagnosed with a past alcohol (n = 52) or substance (n = 26) abuse. Patients gave written informed consent to study protocols approved by the local Ethics Committees according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Major Depressive Disorder (n = 818) | Bipolar Disorder (n = 132) | Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder (n = 119; SZ n = 74, SZA n = 45) | P (F/χ 2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 36.95 (13.19) | 41.03 (11.94) | 38.13 (11.81) | .003a (5.82) |

| Sex | M = 288, F = 530 | M = 61, F = 71 | M = 63, F = 56 | < .001 (17.53) |

| Years of education | 13.19 (2.74) | 14.02 (2.8) | 12.61 (2.68) | < .001b (8.07) |

| Age of onset | 26.12 (12.62) | 24.26 (11.29) | 22.46 (9.4) | .005c (5.39) |

| Life time cumulative duration of hospitalizations (months) | 11.68 (17.84) | 33.23 (33.59) | 38.46 (38.91) | < .001d (96.71) |

| Duration of current episode (months) | 22.84 (46.46) | 12.92 (35.61) | 30.2 (56.93) | .093 (2.39) |

| Verbal IQ | 112.67 (13.78) | 114.98 (15.62) | 111.82 (14.79) | .161 (1.83) |

| Psychopathological factors | ||||

| Depression (F1) | 0.69 (1.02) | −0.33 (0.95) | −0.29 (0.88) | < .001e (13.83) |

| Negative syndrome (F2) | −0.06 (0.47) | −0.14 (0.36) | 0.33 (0.74) | < .001f (35.42) |

| Positive formal thought disorder (F3) | −0.04 (0.1) | 0.04 (0.21) | 0.19 (0.37) | < .001g (107.14) |

| Paranoid−hallucinatory syndrome (F4) | −0.07 (0.13) | −0.03 (0.13) | 0.47 (0.71) | < .001h (219.5) |

| Increased appetite (F5) | −0.01 (0.53) | 0.09 (0.71) | −0.04 (0.51) | .12 (2.13) |

Note: SZ, schizophrenia; SZA, schizoaffective disorder. Values indicate means and SD (in brackets). Post hoc differences between groups.

aBipolar disorder (BD) > major depressive disorder (MDD).

bBD > MDD, schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD).

cMDD > SSD.

dSSD > MDD, BD > MDD.

eMDD > SSD, BD.

fSSD > MDD, BD.

gSSD > BD, MDD; BD > MDD.

hSSD > BD, MDD.

MRI Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

MRI data acquisition was done according to an extensive quality assurance protocol.55 In Münster, a 3T MRI scanner (Prisma, Siemens, Germany) and a 20-channel head matrix Rx-coil were used. MRI data in Marburg were obtained using a 3T MRI scanner (Tim Trio, Siemens, Germany) and a 12-channel head matrix Rx-coil. At both sites, we used a fast gradient echo MP-RAGE sequence with a slice thickness of 1.0 mm consisting of 176 in Marburg and 192 in Münster sagittal orientated slices and a field of view of 256 mm. Parameters were differing across sites: Marburg: time of repetition [TR] = 1.9 seconds, echo time [TE] = 2.26 milliseconds, inversion time [TI] = 900 milliseconds, flip angle = 9°; Münster: TR = 2.13 seconds, TE = 2.28 milliseconds, TI = 900 milliseconds, flip angle = 8°. Before preprocessing, all scans were visually inspected regarding artifacts and anatomical abnormalities by a senior clinician (U.D.). Structural MRI data were preprocessed56 using default parameters as implemented in the CAT12-Toolbox (Computation Anatomy Toolbox for SPM, build 1184, Structural Brain Mapping group, Jena University Hospital, Germany; http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat/) building on SPM12 (Statistical Parametric Mapping, Institute of Neurology, London, UK) providing bias-corrected, tissue classified, and normalized data ratings. During preprocessing, images were segmented57 into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Images were spatially registered, segmented, and normalized58 using a DARTEL algorithm. All scans underwent the automated quality assurance, using the CAT12 “check data quality using covariance” procedure. After preprocessing and the described quality assurance protocols, we excluded n = 113 patients, due to major artifacts or abnormalities not accomplishing the CAT12 quality criteria, leaving N = 1069 for the current study. MRI data sets were spatially smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 8 mm full width at half maximum.

Statistical Analyses

Multidimensional Factors.

Using a cross-validation approach within 2 samples, we had performed an exploratory and confirmatory psychopathological factor analysis in our previous study.2The scale for the assessment of negative symptoms,59 scale for the assessment of positive symptoms,60 Young mania rating scale,61 Hamilton anxiety rating scale,62 and the Hamilton depression scale63 with a total of 104 symptoms were used to identify multidimensional, psychopathological factors across diagnosis. Psychopathological data were obtained during a clinical interview and were rated immediately afterwards by clinically trained psychologists (for detailed information see, Stein et al.2). Interrater reliability achieved excellent values of >.86 in all scales. Summarizing the procedures, we divided the total sample and conducted a varimax-rotated principal axis factor analysis in the first sample. To validate the explorative factor solution, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis in the second sample using Mplus64 (MLR model estimation) showing a good fit: χ 2 = 1287.842, df = 571, P < .0001, comparative fit index = 0.932, root mean square error of approximation = 0.036. The following factors were found in our previous study: depression, negative syndrome, pFTD, paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome, and increased appetite. Latent, standardized factor scores for each patient of the current study were used from this previous study,2 to test whether the previously established dimensional factors were associated with GMV.

Voxel-Based Morphometry Analyses:

Whole Brain Level. We used smoothed GMVs and standardized latent factor scores for each patient to perform separate linear regression models for each transdiagnostic factor (not for each diagnostic group). Analyses were carried out using SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). To avoid potential confounders, we applied several covariates of no interest: age, sex, site and total intracranial volume, and the change of one gradient coil.54,55 As previously reported in our factor analytic study,2 increased appetite was not correlated to antipsychotics, only to intake of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants with negligible effects. Therefore, we used 3 dummy-coded covariates accounting for the intake of at least one antidepressant, mood stabilizer, and antipsychotic. As recommended for VBM analyses, absolute threshold masking with a threshold value of 0.1 was used. Cluster labeling was applied using the dartel space Neuromorphometrics atlas (http://www.neuromorphometrics.com/).

For each psychopathological factor, associations with GMV (whole brain) at peak-level threshold P <.05, family-wise error (FWE) corrected, and cluster extend threshold k = 10 were investigated. To investigate if our transdiagnostic brain correlates were driven by DSM-IV diagnostic categories, we performed ANCOVA interaction analyses (diagnostic category × factor) in SPM on whole brain level.

Due to the unbalanced distribution of DSM-IV categories, in further confirmatory analyses, we used whole brain clusters of the total sample and tested them as regions of interest (ROIs) in an equally distributed sample matched for age and sex (n = 357) (matching was performed using the “MatchIt” package65 in R66). We also performed ANCOVA interaction analyses in the matched sample. For the matched sample, significance level was set at α <.05, false discovery rate (FDR) corrected.

Clinical variables, ie, life time cumulative duration of hospitalizations,67,68 duration of current episode,69 years of education,70,71 and verbal IQ72 were tested for potentially moderating effects on the associations between brain structure and psychopathological factor. Therefore, eigenvariates (weighted mean) as an approximation of mean value inside the clusters were extracted. Moderator models (PROCESS macro v3.3 for SPSS,73 model number 1) were corrected for the same covariates as VBM analyses.

Voxel-Based Morphometry: ROI Analyses.

We tested whether our 5 psychopathological factors2 were associated with GMV across diagnoses, using a ROI approach. To objectively select ROIs, we performed a comprehensive literature search using MEDLINE (PubMed.gov interface) and additionally went through references in the articles identified. For inclusion of a ROI for our analyses, the following literature selection criteria were applied: (1) meta-analyses published after 2010, or if a meta-analysis for a factor was not available review article in a high ranking journal; (2) investigating at least one of the 5 syndromes in patients with MDD, SSD, or BD dimensionally (ie, correlating psychopathological scores with GMV; studies performing a mere patient-healthy control design were not included); and (3) the ROIs had to be replicated in 2 individual original studies, published after 2005. Based on these criteria, the literature search revealed the meta-analyses and ROIs listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Psychopathological Factors Derived From Our Patients,2 Meta-Analysis or Review Article on Structural Brain Correlates of These Syndromes and Selected Regions for Our Region-of-Interest Analysis

| Psychopathological Factor | Literature | Region |

|---|---|---|

| Depression (F1) | Schmaal et al. (2017)46 | Right middle frontal gyrus |

| Left hippocampus | ||

| Bilateral superior frontal gyri | ||

| Negative syndrome (F2) | İnce and Üçok (2018)37 | Left middle frontal gyrus |

| Bilateral thalami | ||

| Bilateral insulae | ||

| Bilateral frontal opercula | ||

| Positive formal thought disorder (F3) | Sumner et al. (2018)34; Cavelti et al. (2018)35 | Bilateral orbitofrontal cortices |

| Left superior temporal gyrus | ||

| Left planum temporale | ||

| Left amygdala-hippocampus complex | ||

| Left anterior cingulate gyrus | ||

| Bilateral superior temporal gyri | ||

| Bilateral amygdalae | ||

| Paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome (F4) | Mucci et al. (2019)25 | Bilateral thalami proper |

| Bilateral insulae | ||

| Bilateral planum temporale | ||

| Left anterior cingulate gyrus | ||

| Left insula | ||

| Bilateral superior temporal gyri | ||

| Left angular gyrus | ||

| Left postcentral gyrus | ||

| Increased appetite (F5) | Gibson et al. (2010)52 | Bilateral nuclei accumbens |

| Bilateral amygdalae |

Masks for the ROIs were created using the “dartel space neuromorphometrics” atlas (http://www.neuromorphometrics.com/) in CAT12. Using the batch mode, the search space for each factor and the selected ROIs was restricted beforehand. We accounted the same covariates as for whole brain analyses using a P <.05, peak-level FWE corrected, and k = 10 threshold. Since all ROIs were reported to be negatively associated with the symptom dimensions, we performed one sided t tests. Furthermore, interactions analyses were performed to test if ROIs were driven by DSM-IV diagnostic categories.

Results

Whole Brain Analyses

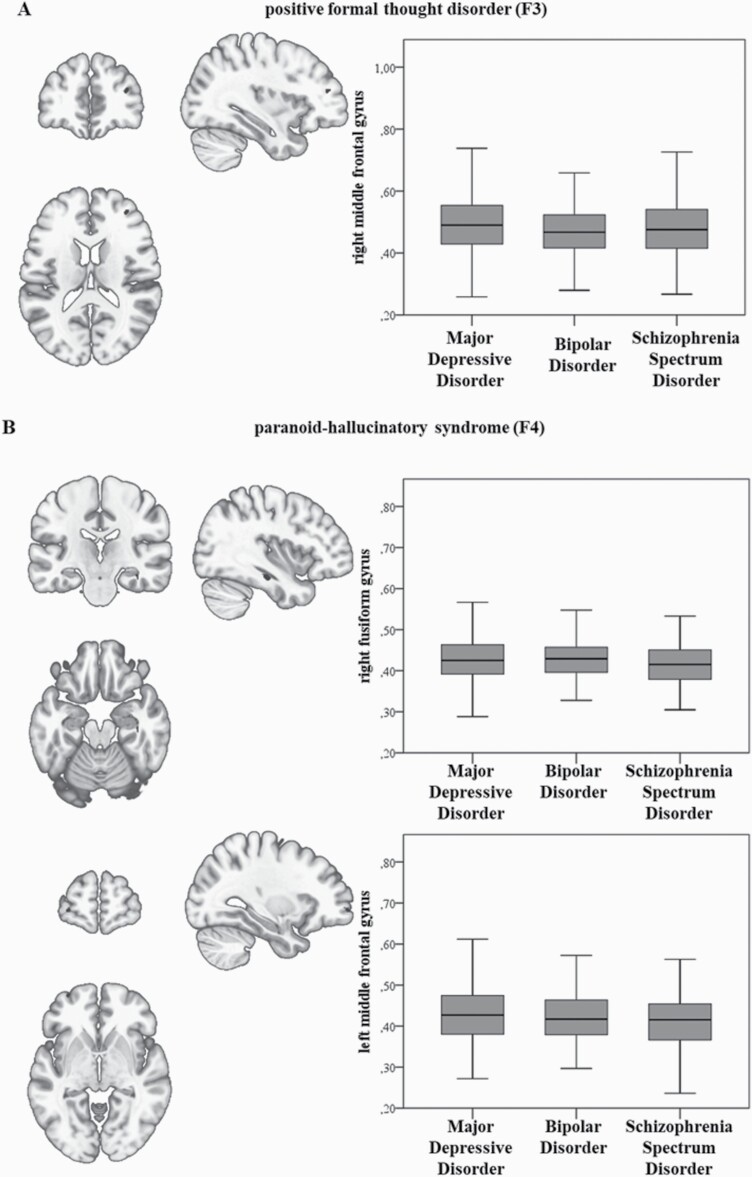

In the total sample, the pFTD factor (F3) was negatively associated with GMV in the right middle frontal gyrus (MFG) (k = 30 voxels, x/y/z = 34/46/16, T = 4.85, Z = 4.82, P = .01, FWE). The paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome factor was negatively correlated with GMV in the right fusiform gyrus (k = 24 voxels, x/y/z = 38/−21/−20, T = 5.08, Z = 5.05 P = .005, FWE) and in the left MFG (k = 27 voxels, x/y/z = −32/62/−3, T = 4.79, Z = 4.76 P = .02, FWE) (see figure 1). No FWE-corrected association was present for the other factors. Interaction analyses of diagnostic group × factor in the total sample (N = 1069) showed no significant results.

Fig. 1.

(A, B) Negative correlations between gray matter volume for (A) positive formal thought disorder and the right middle frontal gyrus and (B) between the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome and the right fusiform and left middle frontal gyrus, family-wise error peak-level corrected. Bar graphs on the right represent extracted eigenvariates of the clusters for each diagnostic group.

To rule out potential effects of differences in the number of patients per diagnoses, we performed multiple regression and ANCOVA interaction analyses again in the age- and sex- matched subsample (n = 357). We replicated the negative association of the right MFG Cluster and pFTD in the matched sample, too (k = 30 voxels, x/y/z = 33/46/16, T = 4.25, Z = 4.2 P = 1.198*10–7, FDR). The negative association of the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome and the right fusiform gyrus (k = 24 voxels, x/y/z = 38/−21/−20, T = 4.14, Z = 4.09 P = 1.384*10–4, FDR), as well as the left MFG cluster (k = 27 voxels, x/y/z = −33/57/0, T = 4.73, Z = 4.65 P = 9.022*10–6, FDR) were also present in the matched sample. Interaction analyses of diagnostic group × factor showed no significant results.

Post hoc moderator analyses of illness variables showed a significant moderation of life time cumulative duration of hospitalizations on the association of F4 “paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome” and the right fusiform cluster (R2 = .018, F = 20.76; P < .001) and the left MFG cluster (R2 = .009, F = 10.01; P = .002). The duration of current episode moderated associations of GMV clusters and F4 (right fusiform gyrus: R2 = .01, F = 6.54; P = .012; left MFG: R2 = .011, F = 7.23; P = .007). Both life time cumulative duration of hospitalizations (R2 = .002, F = 1.86; P = .173) and the duration of the current episode (R2 = .002, F = 0.12; P = .727) did not moderate the right MFG cluster (F3). Years of education moderated the association of pFTD and the right MFG (R2 = .007, F = 8.16; P = .004). There was no moderating effect of verbal IQ.

ROI Analyses

Based on our literature search, we applied separate ROI analyses for each factor, in the total sample. We found FWE peak-level corrected GMV negative associations in the selected ROIs for the negative syndrome, pFTD, and the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome (see table 3). The selected ROIs for the depression and increased appetite factor revealed no significant association. Interaction analyses (diagnoses × psychopathological factor) revealed no interaction in all ROIs in both the total sample and in the age- and sex- matched sample (same n per diagnosis).

Table 3.

Significant Gray Matter Volume Reductions in the ROIs, FWE Peak-Level Corrected

| Factor | ROI | Coordinates |

P

FWE |

k | T | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative syndrome (F2) | Bilateral frontal opercula | [−48; 18; 21] | .031 | 21 | 3.512 | 3.501 |

| Positive formal thought disorder (F3) | Left amygdala-hippocampus complex | [−34.5; −22.5; −15] | .018 | 99 | 3.386 | 3.376 |

| Paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome (F4) | Bilateral thalami proper | [−6; −12; 12] | .006a |

1201 |

3.995 | 3.979 |

| [−13.5; −25.5; 10.5] | .007 | 3.943 | 3.928 | |||

| [9; −3; 1.5] | .013 | 3.760 | 3.747 | |||

| Left angular gyrus | [−55.5; −64.5; 27] | .026 | 15 | 3.627 | 3.615 | |

| Left postcentral gyrus | [−61.5; −19.5; 31.5] | .003a |

405 |

4.267 | 4.248 | |

| [−58.5; −21; 39] | .005a | 4.172 | 4.154 | |||

| [−57; −22.5; 25.5] | .007 | 4.076 | 4.059 | |||

| Left posterior cingulate gyrus | [−13.5; −40.5; 3] | .011 | 11 | 3.633 | 3.621 |

Note: FWE, family-wise error; ROI, region of interest. ROIs tested are listed in table 2.

aSignificant difference after Bonferroni correction for multiple ROI testing.

Discussion

Given the limitations of meta-analytic studies pooling single DSM diagnoses, our study investigated the relationship between regional brain volumes and dimensional, transdiagnostic psychopathological syndromes in one large sample comprising patients with MDD, BD, and SSD. Building on our previous work, we had derived 5 psychopathological factors (ie, depression, negative syndrome, pFTD, paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome, and increased appetite).2 On whole brain level, we found negative associations for pFTD with the right MFG and the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome with the right fusiform gyrus and the left MFG. Using ROI analyses, we were able to confirm a number of previous results across diagnoses: The negative syndrome was negatively associated with the bilateral frontal opercula, pFTD with the left amygdala-hippocampus complex and the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome with the bilateral thalami proper, the left postcentral gyrus, the left posterior cingulate gyrus, and the left angular gyrus. Based on these findings, we can draw 3 new insights. First, there was no interaction effect of DSM-IV diagnostic categories × psychopathological factors in all GMV associations on whole brain level and within the ROI analyses in both the total sample and in the matched sample containing the same n per diagnosis, strengthening our assumption of shared transdiagnostic, psychopathological factor-local GMV associations74–77 within MDD, BD, and SSD. Additionally, whole brain clusters found in the total sample could be replicated in the matched sample, too. This mirrors meta- or mega-analytic results from brain structural,5,6,8,23 molecular genetic genome-wide association studies,3,78 immunology,9 and environmental factors,4,79 showing large biological overlapping across these disorders. In contrast to these previous pooling studies, we included only patients from one large study. Interestingly, important clinical variables which have previously been related to brain structural alterations, such as life time cumulative duration of hospitalizations67,68 and duration of the current illness episode,69 did indeed moderate the extracted GMV clusters in our study. This validates our findings and confirms the significance of illness aspects other than the clinical diagnosis. Based on these converging findings across modalities, we hypothesize that genetic and environmental factors impact the developing brain at different times and intensities across individuals affected regional brain structure, with the particular location/network depending on the individual factors. The involved network during development determines the psychopathological syndrome predominant later in life after disorder onset. Second, the approach applied here allowed us to investigate symptom complexes such as the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome across disorders, which has previously been mostly investigated in SZ patients. But it is well known that MDD patients also show elevated psychotic symptoms.10,11 Regression analyses were performed independent of the state of patients (ie, acute, chronic, and remitted). Thus, our approach is less prone to subgroup effects that may arise when applying categorical approaches. Third, by using whole brain and ROI-based approaches, we exploratively tested transdiagnostic brain structures on whole brain level and identified anatomical signatures across disorders previously reported to be associated with psychopathological syndromes within 1 or 2 disorders.

We did not find associations between GMV and the depression factor, a finding in line with the vast majority of previous studies.45,46,80 Structural alterations in patients with MDD are not correlated with current depressive symptomatology but rather chronicity and cumulative severity.45,47,81,82

Within the ROI analysis, the negative syndrome was associated with the bilateral frontal opercula volumes. This is a well-known finding from structural imaging studies investigating SZ patients.83–87 GMV reductions in the frontal opercula correlated with persistent negative symptoms.37,83,88

The pFTD factor was negatively associated with the right MFG on whole brain level, and the left amygdala-hippocampus complex in the ROI analysis. Previously, pFTD in SZ has been associated with neuroanatomical alterations in Wernicke’s and Broca’s language areas, as well as the middle frontal gyri and the left amygdala-hippocampus complex.32–35 We could replicate these findings in our transdiagnostic sample. As opposed to the left, we found the right MFG homologue associated with pFTD, an area which is involved in language processing in SZ patients.32,34,35 Furthermore, there is evidence that the hippocampus plays a major role in word generation tasks which coincides with our findings.89,90

On a whole brain level, the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome was negatively associated with the right fusiform gyrus and the left MFG. Previous studies24,25,27,31,40,91 showed that medial temporal regions are correlated with “positive” symptomatology, which mainly comprises the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome. Besides the inferior temporal gyri, the bilateral fusiform gyri have been reported as a significant correlate of positive symptoms (measured with Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS]).40,91 A meta-analysis including 4474 paranoid-hallucinatory SZ patients showed that reductions in both the right fusiform gyrus and the bilateral inferior temporal gyri have the largest effect sizes.92 Several studies have shown negative associations of GMV and the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome factor in the overall frontal volume93 as well as GMV reductions in the left pars orbitalis and the left superior frontal gyrus.40 The left MFG has been shown to be deactivated in preceding auditory hallucinations.94 The ROI analyses revealed significant associations between the paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome and the bilateral thalami proper,27,28,95 the left angular gyrus, the postcentral gyrus, and the left posterior cingulate gyrus,25,27 confirming many previous studies.

The factor “increased appetite” was, independent of medication, a dimension in our psychopathological factor analytic study2 that has been shown to emerge if psychopathological scales are used that capture vegetative symptoms.48,96 We did not find associations with GMV neither on whole brain level nor within the ROI analyses. This may indicate that biological influences other than GMV have an impact on the manifestation of increased appetite. Nevertheless, increased appetite is a relevant syndrome across disorders that deserves further investigation.

Limitations

Some limitations must be noted. First, patient groups were unequally distributed which potentially biased our results since the MDD group was the largest. However, we were able to confirm the results of our interaction analyses (total sample) in an age- and sex-matched subsample (same n in each diagnosis). Second, the MDD group only marginally presented with psychotic symptoms compared to BD and SSD patients resulting in restricted variance found for psychotic symptoms (ie, factor 4 “paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome”). Third, the extracted factors were based on current psychopathology. Correlating current state measures with brain structure misses past psychopathology. However, specific current symptoms are an indication for a particular neuroanatomical, state-independent alteration that outlasts current symptoms. Still, it would be of great interest to investigate the stability of both factor dimensions and their relationship to brain structure validating the present cross-sectional results. Fourth, pharmacological treatment was considered in our models using 3 dummy-coded variables accounting for the intake of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics. However, the influence of both dosage and duration of intake on GMV is not considered.

Conclusion

In sum, our findings provide a novel anatomical mapping of psychopathological symptom dimensions across disorders. The main strength of the present study is the use of a large transdiagnostic cohort, innovative data-driven psychopathological factors, and the inclusion of patients across psychotic and affective disorders. Our findings give evidence for shared and diagnosis-independent GMV reductions associated with symptom dimensions. We try to overcome a current deadlock in scientific approaches which has one origin in a misguided reification of DSM diagnoses.

Funding

The MACS cohort is part of the FOR2107 project funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), grant numbers: KI588/14-1, KI588/14-2; DA1151/5-1, DA1151/5-2; KR3822/5-1, KR3822/7-2; NE2254/1-2; KO4291/3-1. The study was in part supported by grants from Universitätsklinikum Giessen und Marburg and Forschungscampus Mittelhessen to I.N.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the German multicentre consortium “Neurobiology of Affective Disorders. A translational perspective on brain structure and function”. Principal investigators are: MACS cohort: T.K. (coordinator), U.D., A.K., I.N., and Carsten Konrad. The FOR2107 cohort project was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Medical Faculties, University of Marburg (AZ:07/14) and University of Münster (AZ:2014-422-b-S). We are deeply indebted to all study participants and staff. A list of acknowledgments can be found here: www.for2107.de/acknowledgements. T.K. received unrestricted educational grants from Servier, Janssen, Recordati, Aristo, Otsuka, and Neuraxpharm. All other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Kaczkurkin AN, Moore TM, Calkins ME, et al. Common and dissociable regional cerebral blood flow differences associate with dimensions of psychopathology across categorical diagnoses. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(10):1981–1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stein F, Lemmer G, Schmitt S, et al. Factor analyses of multidimensional symptoms in a large group of patients with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020;218:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee PH, Anttila V, Won H, et al. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2019;179(7):1469–1482.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uher R, Zwicker A. Etiology in psychiatry: embracing the reality of poly-gene-environmental causation of mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang M, Womer FY, Edmiston EK, et al. Neurobiological commonalities and distinctions among three major psychiatric diagnostic categories: a structural MRI study. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(1):65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Opel N, Goltermann J, Hermesdorf M, Berger K, Baune BT, Dannlowski U. Cross-disorder analysis of brain structural abnormalities in six major psychiatric disorders: a secondary analysis of mega- and meta-analytical findings from the ENIGMA Consortium. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;88(9):678–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lalousis PA, Wood SJ, Schmaal L, et al. Heterogeneity and classification of recent onset psychosis and depression: a multimodal machine learning approach. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47:1130–1140. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(12):1696–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johns LC, Cannon M, Singleton N, et al. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported psychotic symptoms in the British population. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Varghese D, Scott J, Welham J, et al. Psychotic-like experiences in major depression and anxiety disorders: a population-based survey in young adults. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(2):389–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosen C, Marvin R, Reilly JL, et al. Phenomenology of first-episode psychosis in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression: a comparative analysis. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2012;6(3):145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reininghaus U, Böhnke JR, Chavez-Baldini U, et al. Transdiagnostic dimensions of psychosis in the Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP). World Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clementz BA, Trotti RL, Pearlson GD, et al. Testing psychosis phenotypes from Bipolar-Schizophrenia Network for Intermediate Phenotypes for clinical application: biotype characteristics and targets. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2020;5(8):808–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reininghaus U, Böhnke JR, Hosang G, et al. Evaluation of the validity and utility of a transdiagnostic psychosis dimension encompassing schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(2):107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Dorn RA, Desmarais SL, Grimm KJ, et al. The latent structure of psychiatric symptoms across mental disorders as measured with the PANSS and BPRS-18. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Serretti A, Olgiati P. Dimensions of major psychoses: a confirmatory factor analysis of six competing models. Psychiatry Res. 2004;127(1–2):101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Serretti A, Rietschel M, Lattuada E, et al. Major psychoses symptomatology: factor analysis of 2241 psychotic subjects. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251(4):193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Romney DM, Candido CL. Anhedonia in depression and schizophrenia: a reexamination. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(11):735–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peralta V, Gil-Berrozpe GJ, Sánchez-Torres A, Cuesta MJ. The network and dimensionality structure of affective psychoses: an exploratory graph analysis approach. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wernicke C. Grundriss Der Psychiatrie in Klinischen Vorlesungen. Berlin, Germany: Georg von Thieme; 1900. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patel Y, Writing Committee for the Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder , et al. Virtual histology of cortical thickness and shared neurobiology in 6 psychiatric disorders. JAMA psychiatry. 2020;78(1):47–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koutsouleris N, Meisenzahl EM, Borgwardt S, et al. Individualized differential diagnosis of schizophrenia and mood disorders using neuroanatomical biomarkers. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 7):2059–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palaniyappan L, Balain V, Radua J, Liddle PF. Structural correlates of auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1–3):169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mucci A, Galderisi S, Amodio A, Dierks T. Neuroimaging and psychopathological domains. In: Galderisi S, DeLisi LE, Borgwardt S, eds. Neuroimaging of Schizophrenia and Other Primary Psychotic Disorders: Achievements and Perspectives. Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019:57–155. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koutsouleris N, Gaser C, Jäger M, et al. Structural correlates of psychopathological symptom dimensions in schizophrenia: a voxel-based morphometric study. Neuroimage. 2008;39(4):1600–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nenadic I, Smesny S, Schlösser RG, Sauer H, Gaser C. Auditory hallucinations and brain structure in schizophrenia: voxel-based morphometric study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(5):412–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang P, Xi Y, Lu ZL, et al. Decreased bilateral thalamic gray matter volume in first-episode schizophrenia with prominent hallucinatory symptoms: a volumetric MRI study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takahashi T, Suzuki M, Zhou SY, et al. Morphologic alterations of the parcellated superior temporal gyrus in schizophrenia spectrum. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(2–3):131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palaniyappan L, Mallikarjun P, Joseph V, White TP, Liddle PF. Reality distortion is related to the structure of the salience network in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2011;41(8):1701–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stan AD, Tamminga CA, Han K, et al. Associating psychotic symptoms with altered brain anatomy in psychotic disorders using multidimensional item response theory models. Cereb Cortex. 2020;30(5):2939–2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kircher T, Bröhl H, Meier F, Engelen J. Formal thought disorders: from phenomenology to neurobiology. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):515–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Strik W, Stegmayer K, Walther S, Dierks T. Systems neuroscience of psychosis: mapping schizophrenia symptoms onto brain systems. Neuropsychobiology. 2018;75(3):100–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sumner PJ, Bell IH, Rossell SL. A systematic review of the structural neuroimaging correlates of thought disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;84:299–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cavelti M, Kircher T, Nagels A, Strik W, Homan P. Is formal thought disorder in schizophrenia related to structural and functional aberrations in the language network? A systematic review of neuroimaging findings. Schizophr Res. 2018;199:2–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Walton E, Hibar DP, van Erp TGM, et al. ; Karolinska Schizophrenia Project Consortium (KaSP) . Prefrontal cortical thinning links to negative symptoms in schizophrenia via the ENIGMA consortium. Psychol Med. 2018;48(1):82–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. İnce E, Üçok A. Relationship between persistent negative symptoms and findings of neurocognition and neuroimaging in schizophrenia. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2018;49(1):27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Collin G, Derks EM, van Haren NEM, et al. Symptom dimensions are associated with progressive brain volume changes in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(2–3):171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Banaj N, Piras F, Piras F, et al. Cognitive and psychopathology correlates of brain white/grey matter structure in severely psychotic schizophrenic inpatients. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2018;12:29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Padmanabhan JL, Tandon N, Haller CS, et al. Correlations between brain structure and symptom dimensions of psychosis in schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and psychotic bipolar I disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(1):154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vasic N, Walter H, Höse A, Wolf RC. Gray matter reduction associated with psychopathology and cognitive dysfunction in unipolar depression: a voxel-based morphometry study. J Affect Disord. 2008;109(1–2):107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Webb CA, Weber M, Mundy EA, Killgore WDS. Reduced gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal cortex and thalamus as a function of mild depressive symptoms: a voxel-based morphometric analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;44(13):2833–2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McLaren ME, Szymkowicz SM, O’Shea A, Woods AJ, Anton SD, Dotson VM. Vertex-wise examination of depressive symptom dimensions and brain volumes in older adults. Psychiatry Res—Neuroimaging. 2017;260:70–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McLaren ME, Szymkowicz SM, O’shea A, Woods AJ, Anton SD, Dotson VM. Dimensions of depressive symptoms and cingulate volumes in older adults. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(4):e788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Abe O, Yamasue H, Kasai K, et al. Voxel-based analyses of gray/white matter volume and diffusion tensor data in major depression. Psychiatry Res—Neuroimaging. 2010;181(1):64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schmaal L, Hibar DP, Sämann PG, et al. Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(6):900–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grieve SM, Korgaonkar MS, Koslow SH, Gordon E, Williams LM. Widespread reductions in gray matter volume in depression. NeuroImage Clin. 2013;3:332–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li Y, Aggen S, Shi S, et al. The structure of the symptoms of major depression: exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in depressed Han Chinese women. Psychol Med. 2014;44(7):1391–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van Loo HM, de Jonge P, Romeijn JW, Kessler RC, Schoevers RA. Data-driven subtypes of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2012;10:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Toenders YJ, Schmaal L, Harrison BJ, Dinga R, Berk M, Davey CG. Neurovegetative symptom subtypes in young people with major depressive disorder and their structural brain correlates. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dagher A. The neurobiology of appetite: hunger as addiction. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(suppl. 2):S30–S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gibson CD, Carnell S, Ochner CN, Geliebter A. Neuroimaging, gut peptides and obesity: novel studies of the neurobiology of appetite. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22(8):833–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Opel N, Thalamuthu A, Milaneschi Y, et al. Brain structural abnormalities in obesity: relation to age, genetic risk, and common psychiatric disorders: evidence through univariate and multivariate mega-analysis including 6420 participants from the ENIGMA MDD working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;1–14. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kircher T, Wöhr M, Nenadic I, et al. Neurobiology of the major psychoses: a translational perspective on brain structure and function—the FOR2107 consortium. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;1:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vogelbacher C, Möbius TWD, Sommer J, et al. The Marburg-Münster Affective Disorders Cohort Study (MACS): a quality assurance protocol for MR neuroimaging data. Neuroimage. 2018;172:450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry—the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11(6 Pt 1):805–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage. 2005;26(3):839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage. 2007;38(1):95–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Andreasen N. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Andreasen N. The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Muthén LK, Muthén BO.. Mplus User´s Guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ho D, Kosuke I, King G, Stuart E. Matchit: Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw. 2011; 42( 8):1– 28. doi: 10.18637/jss.v042.i08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020.. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.

- 67. Liao J, Yan H, Liu Q, et al. Reduced paralimbic system gray matter volume in schizophrenia: correlations with clinical variables, symptomatology and cognitive function. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;65:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhang X, Zhang Y, Liao J, et al. Progressive grey matter volume changes in patients with schizophrenia over 6 weeks of antipsychotic treatment and their relationship to clinical improvement. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34(5):816–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zavorotnyy M, Zöllner R, Schulte-Güstenberg LR, et al. Low left amygdala volume is associated with a longer duration of unipolar depression. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2018;125(2):229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tracy M, Zimmerman FJ, Galea S, McCauley E, Stoep AV. What explains the relation between family poverty and childhood depressive symptoms? J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(14):1163–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yang J, Liu H, Wei D, et al. Regional gray matter volume mediates the relationship between family socioeconomic status and depression-related trait in a young healthy sample. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2016;16(1):51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chang WH, Chen KC, Tseng HH, et al. Bridging the associations between dopamine, brain volumetric variation and IQ in drug-naïve schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020;220:248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gong Q, Scarpazza C, Dai J, et al. A transdiagnostic neuroanatomical signature of psychiatric illness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(5):869–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lahey BB, Applegate B, Hakes JK, Zald DH, Hariri AR, Rathouz PJ. Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121(4):971–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stochl J, Khandaker GM, Lewis G, et al. Mood, anxiety and psychotic phenomena measure a common psychopathological factor. Psychol Med. 2015;45(7):1483–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, et al. The p Factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2(2):119–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018;360(6395):eaap8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Vassos E, Sham P, Kempton M, et al. The Maudsley Environmental Risk Score for psychosis. Psychol Med. 2020;50(13):2213–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Maggioni E, Crespo-Facorro B, Nenadic I, et al. ; ENPACT Group . Common and distinct structural features of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: The European Network on Psychosis, Affective disorders and Cognitive Trajectory (ENPACT) study. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zaremba D, Enneking V, Meinert S, et al. Effects of cumulative illness severity on hippocampal gray matter volume in major depression: a voxel-based morphometry study. Psychol Med. 2018;48(14):2391–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zaremba D, Dohm K, Redlich R, et al. Association of brain cortical changes with relapse in patients with major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(5):484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bergé D, Carmona S, Rovira M, Bulbena A, Salgado P, Vilarroya O. Gray matter volume deficits and correlation with insight and negative symptoms in first-psychotic-episode subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123(6):431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kim G-W, Kim Y-H, Jeong G-W. Whole brain volume changes and its correlation with clinical symptom severity in patients with schizophrenia: a DARTEL-based VBM study. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sigmundsson T, Suckling J, Maier M, et al. Structural abnormalities in frontal, temporal, and limbic regions and interconnecting white matter tracts in schizophrenic patients with prominent negative symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):234–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS, Haznedar MM, et al. Cortical gray and white matter volume in unmedicated schizotypal and schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1–3):111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bora E, Fornito A, Radua J, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities in schizophrenia: a multimodal voxelwise meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1-3):46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Li Y, Li WX, Xie DJ, Wang Y, Cheung EFC, Chan RCK. Grey matter reduction in the caudate nucleus in patients with persistent negative symptoms: an ALE meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2018;192:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kircher T, Whitney C, Krings T, Huber W, Weis S. Hippocampal dysfunction during free word association in male patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1–3):242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Whitney C, Weis S, Krings T, Huber W, Grossman M, Kircher T. Task-dependent modulations of prefrontal and hippocampal activity during intrinsic word production. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21(4):697–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mennigen E, Jiang W, Calhoun VD, et al. Positive and general psychopathology associated with specific gray matter reductions in inferior temporal regions in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:242–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. van Erp TGM, Walton E, Hibar DP, et al. ; Karolinska Schizophrenia Project . Cortical brain abnormalities in 4474 individuals with schizophrenia and 5098 control subjects via the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics Through Meta Analysis (ENIGMA) Consortium. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(9):644–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Magnotta V, Pierson R, Ziebell S, Ho BC. Progressive brain change in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):672–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Diederen KMJ, Neggers SFW, Daalman K, et al. Deactivation of the parahippocampal gyrus preceding auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(4):427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Huang X, Pu W, Li X, et al. Decreased left putamen and thalamus volume correlates with delusions in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Rabkin JG, Quitkin FM. Atypical depression. A valid clinical entity? Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1993;16(3):479–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]