Abstract

Background

Obesity is highly prevalent in schizophrenia, with implications for psychiatric prognosis, possibly through links between obesity and brain structure. In this longitudinal study in first episode of psychosis (FEP), we used machine learning and structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study the impact of psychotic illness and obesity on brain ageing/neuroprogression shortly after illness onset.

Methods

We acquired 2 prospective MRI scans on average 1.61 years apart in 183 FEP and 155 control individuals. We used a machine learning model trained on an independent sample of 504 controls to estimate the individual brain ages of study participants and calculated BrainAGE by subtracting chronological from the estimated brain age.

Results

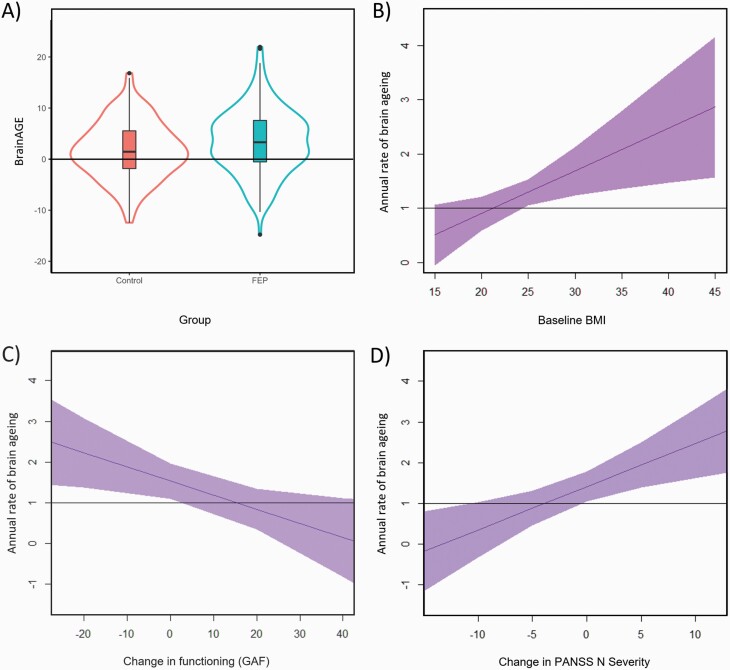

Individuals with FEP had a higher initial BrainAGE than controls (3.39 ± 6.36 vs 1.72 ± 5.56 years; β = 1.68, t(336) = 2.59, P = .01), but similar annual rates of brain ageing over time (1.28 ± 2.40 vs 1.07±1.74 estimated years/actual year; t(333) = 0.93, P = .18). Across both cohorts, greater baseline body mass index (BMI) predicted faster brain ageing (β = 0.08, t(333) = 2.59, P = .01). For each additional BMI point, the brain aged by an additional month per year. Worsening of functioning over time (Global Assessment of Functioning; β = −0.04, t(164) = −2.48, P = .01) and increases especially in negative symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (β = 0.11, t(175) = 3.11, P = .002) were associated with faster brain ageing in FEP.

Conclusions

Brain alterations in psychosis are manifest already during the first episode and over time get worse in those with worsening clinical outcomes or higher baseline BMI. As baseline BMI predicted faster brain ageing, obesity may represent a modifiable risk factor in FEP that is linked with psychiatric outcomes via effects on brain structure.

Keywords: first-episode psychosis, obesity, brain age, antipsychotics, machine learning, longitudinal study

Introduction

Psychotic disorders are among the most disabling conditions, which also present with high rates of medical comorbidities and premature mortality.1,2 Overweight and obesity are particularly prevalent in individuals with schizophrenia,3–5 already early in the course of illness,6–8 including participants with first episode of psychosis (FEP).4 Obesity contributes not only to poor somatic health and shorter life expectancy,9,10 but also to adverse psychiatric outcomes.11,12 It is one of the strongest contributors to functional deterioration in psychosis.11 The pathoplastic effects of obesity on mental health indices may be related to the negative effects of obesity on the brain.

The brain is now recognized as one of the end organs for obesity-related damage.13 Replicated cross-sectional findings from thousands of individuals have demonstrated associations between measures of obesity and brain structure, including basal ganglia, hippocampus, thalamus, frontal, temporal, and cerebellar regions.13–16 In addition, brains of obese/overweight individuals appear older than their chronological age.17,18 Similar neurostructural alterations are frequently reported already early in the course of psychotic disorders,19–21 but their origins remain unknown. Considering the multiple mutual links between obesity, FEP, and brain structure, it is possible that obesity contributes to brain alterations in psychosis. While the effects of obesity on the brain are of major interest in medicine, they remain markedly under-researched in psychiatry.

We have previously demonstrated that obesity was associated with advanced brain age and lower cerebellar volume in FEP.18,22 Yet, the temporal direction of the association remains unclear. Obesity could be contributing to brain changes or vice versa. Longitudinal design can help address the direction of association and the issue of reverse causality. However, there are no longitudinal studies investigating links between obesity and brain atrophy in schizophrenia/FEP. Such studies are necessary to test whether obesity is a risk factor for brain alterations in FEP. Identification of clinical risk factors for brain alterations in psychotic disorders is the first step towards their management. Specifically, a longitudinal study in the early stages of psychotic illness, when the brain and metabolic markers may be most dynamic and additional confounds related to chronicity/long-term use of medications/social factors are relatively limited, offers a particularly strong research design. Focusing on changes that develop early in the course of illness is also clinically relevant for early intervention and prevention of long-term negative outcomes.

Previous brain imaging studies have traditionally focused on individual brain regions. Recently, normative models and cumulative measures of brain structure have become available through access to large databases of brain scans and advances in neuroimaging analyses involving machine learning. One such approach is to estimate the biological age of the brain from structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).23 The difference between estimated brain age and chronological age, so called Brain Age Gap Estimate (BrainAGE), captures diffuse, multivariate neurostructural alterations into a single number, thus simplifying the analyses and aiding in their interpretation.24 The BrainAGE metric is sensitive to the presence of schizophrenia as well as obesity18 and provides a unique opportunity to better understand longitudinal brain changes in major psychiatric disorders.

In this longitudinal study in participants with FEP and controls, we used machine learning and structural MRI to study brain ageing/neuroprogression around the time of illness onset and 1–2 years later. Our a priori hypothesis was that both the diagnosis of FEP and baseline body mass index (BMI) would each be associated with accelerated brain ageing over time. In addition, we explored the effects of other clinical, biochemical variables and medications on annual rates of brain ageing.

Methods

Patient Recruitment

This was a part of the Early-Stage Schizophrenia Outcome (ESO) project,18,25 an ongoing prospective study of individuals with FEP, conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health, Czech Republic (NIMHCZ). Cross-sectional, baseline findings from this study were published previously,18,22,25 but this is the first analysis of the longitudinal data. Individuals with FEP were recruited during their first hospitalization through the ESO Patient Enrolment Network, which involves 10 Czech inpatient psychiatric facilities. Subsequently, participants were centrally assessed by psychiatrists at the NIMHCZ. The largest contributing facility was Psychiatric Hospital Bohnice (1200 beds), which serves the Prague and part of Central Bohemia regions—catchment area of >1.5 million subjects.

Consistent with the literature and our previous studies, FEP was defined as the first hospitalization for psychosis.26,27 Individuals with FEP met the following inclusion criteria: (1) were undergoing their first psychiatric hospitalization; (2) had the ICD-10 diagnosis of schizophrenia (F20), acute and transient psychotic disorders (F23), or schizoaffective disorders (F25) based on Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview28; (3) had fewer than 24 months of untreated psychosis; and (4) were at least 18 years old. Patients with psychotic mood disorders were excluded from the study.

We focused on participants at the early stages of illness, to minimize the effects of illness and medications on brain structure. Thus, individuals who were hospitalized before meeting the duration criteria for schizophrenia are a particularly interesting group. These participants were included in the study and received the working diagnosis of acute and transient psychotic disorders, congruent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) brief psychotic disorder. This approach is in keeping with other studies of FEP.5,29

Healthy controls, at least 18 years old, were recruited via advertisement, using the following exclusion criteria: (1) lifetime history of any psychiatric disorders and (2) psychotic disorders in first- or second-degree relatives. Additional exclusion criteria for both groups included history of neurological or cerebrovascular disorders and any MRI contraindications.

The baseline MRI scanning (Visit 1) was performed during the first hospitalization and study participants were invited for the second scan and assessment (Visit 2) ~1 year later. At each visit, we rated the symptoms, illness severity, and functioning using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),30 Clinical Global Impression (CGI), and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)31 and also collected fasting blood samples for biochemical analyses (glucose, high-density lipoprotein [HDL]-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein [LDL]-cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hsCRP]). Duration of illness and treatment variables were determined via interview together with all available collateral data from medical records, treatment providers, and family members. We expressed antipsychotic doses in chlorpromazine equivalents and calculated the cumulative antipsychotic exposure as dosage times duration of treatment in months. We measured BMI using the formula: BMI = weight (kg)/height (meters).2 All diagnostic assessments, ratings of symptoms and medications, were performed by psychiatrists. Biochemical analyses were done in a single clinical laboratory using standard clinical methods.

The study was carried out according to the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. All study individuals were informed about the study procedures and signed informed consent, which was approved by the local Research Ethics Board.

MRI Acquisition

Structural MRI data were collected at 2 sites, the NIMHCZ, N = 137, and Institute of Clinical Experimental Medicine in Prague (IKEM), N = 221. We acquired T1-weighted 3D MPRAGE scans (TE = 4.63 ms, TR = 2300 ms, bandwidth 130 Hz/pixel, FOV = 256 × 256 mm, matrix 256 × 256, voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm3) on 3T Siemens Trio MRI scanner (IKEM) or 3T Siemens Prisma MAGNETOM (NIMHCZ) MRI equipped with standard head coil.

Brain Age Estimation

We estimated the brain age of each participant using a machine learning method which was developed by us (K.F.), extensively validated,23,32 shown to be sensitive to metabolic or psychiatric disorders,18,25,33,34 and robust to inter-scanner differences.23,32 Briefly, this included (1) standard voxel-based morphometry preprocessing of structural MRI data, (2) feature reduction via smoothing and principal component analysis, and (3) age estimation using relevance vector regression (RVR). This RVR model was trained using an independent sample of 504 healthy individuals from the IXI database (http://www.brain-development.org). For more details, see Franke et al23,33,34 and supplementary material.

Our outcome measure was the BrainAGE, ie, the difference between the estimated brain age and the chronological age. We removed the association between age and BrainAGE using previously documented procedure.35 Specifically, for the cross-sectional analyses, where BrainAGE was the dependent variable, we used age as a covariate. For the longitudinal analyses, we regressed out the fixed effect of age from BrainAGE using a linear mixed model, which also included a random grouping factor of subject ID (one ID per subject) to capture the longitudinal, within-subject design. Model residuals provided BrainAGEcleaned, which was not associated with age. The BrainAGE – BrainAGEcleaned represents the age-related error, which we subtracted from each individual’s estimated brain age, Formula 1, in order to obtain estimated brain age, which was not biased by age.

| (1) |

The annual rate of brain ageing (R) was calculated by using Formula 2:

| (2) |

where ΔT is time elapsed in years between the 2 visits. This provided an annual estimate of brain ageing relative to real time, with 1.0 indicating a change of 1 year in estimated brain age over a 1-year period.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2, with mixed modeling using the package mgcv.36 To compare clinical and demographic variables, we used t test, or chi-square test, as appropriate. We first investigated the association between BrainAGE and clinical or demographic variables, using linear mixed modeling, controlling for a random effect of data collection site, and a fixed effect of participant age. We also used this same method to test the association between follow-up BrainAGE and follow-up clinical or demographic variables to verify that associations were consistent and mirrored longitudinal changes. In longitudinal analyses, we tested the association between group (controls vs FEP) and/or BMI as predictor(s) and the annual rate of brain ageing as dependent variable, while controlling for a random effect of data collection site. To verify that baseline variables were significantly associated with annual rate of brain ageing beyond their association with baseline brain measures, we also additionally controlled for baseline BrainAGE. All of these longitudinal analyses also controlled for age, by using the Estimated Brain Agecleaned, as described above.

In each group separately, we tested whether the annual rate of brain ageing was greater than the expected rate of 1.0 (ie, 1 year of brain ageing per chronological year) and whether the changes in estimated brain age were greater than the interval between the 2 visits, using linear mixed model to control for a random effect of data collection site.

We also explored the association between baseline clinical variables or their changes over time, with annual rate of brain ageing. Lastly, we tested whether the annual rate of brain ageing was best predicted by BMI, biochemical measures, or some combination of the 2. All of these analyses were performed using linear mixed modeling and controlling for a random effect of data collection site. We calculated variance inflation factor (VIF) to check for multicollinearity, which was acceptable in all models and Q-Q plots to ensure normally distributed residuals.

Results

We recruited 183 participants with FEP and 155 controls (table 1; supplementary table S1). Individuals with FEP had a higher baseline BrainAGE (3.39 ± 6.36) than controls (1.72 ± 5.56, β = 1.68, t(336) = 2.59, P = .010; figure 1). Among individuals with FEP, lower baseline functioning (GAF, β = −0.06, t(164) = −2.06, P = .041) and higher PANSS negative scores (β = 0.20, t(175) = 2.85, P = .005) were associated with higher baseline BrainAGE (supplementary table S2).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants at the Time of Their First Visit

| Controls (N = 155) | FEP (N = 183) | Group Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex: male, N (%) | 68 (43.8%) | 102 (55.7%) | χ 2 = 4.26, P = .039 |

| Age, M (SD) | 28.99 (7.41) | 29.29 (7.66) | t(330) = 0.36, P = .714a |

| BMI, M (SD) | 23.32 (3.37) | 23.81 (4.16) | t(332) = 1.20, P = .230 |

| BMI group, N (%)b | χ 2 = 5.86, P = .053 | ||

| Normal weight | 117 (76.5%) | 119 (65.4%) | |

| Overweight | 31 (20.3%) | 49 (26.9%) | |

| Obese | 5 (3.3%) | 14 (7.7%) | |

| NIMHCZ/IKEM, N (%) | 56 (36.13)/99 (63.87) | 69 (37.70)/114 (62.30) | χ 2 = 0.03, P = .853 |

| Glucose (mmol/L), M (SD)c | 4.15 (0.52) | 4.15 (0.51) | t(162) = 0.10, P = .918 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L), M (SD)c | 4.53 (0.89) | 4.53 (0.92) | t(247) = 0.05, P = .960 |

| HDL (mmol/L), M (SD)c | 1.54 (0.39) | 1.30 (0.35) | t(235) = 4.98, P < .001 |

| LDL (mmol/L), M (SD)c | 2.51 (0.74) | 2.57 (0.74) | t(243) = 0.68, P = .494 |

| TGC (mmol/L), M (SD)c | 1.08 (0.48) | 1.44 (0.99) | t(197) = 3.72, P < .001 |

| hsCRP (mmol/L), M (SD)c | 1.65 (2.58) | 2.61 (4.48) | t(217) = 2.14, P = .034 |

| Medical comorbidities, N (%) | n/a | Hypertension: 10 (5.46%) | n/a |

| Type 2 diabetes: 2 (1.09%) | |||

| Dyslipidemia: 0 (0) | |||

| Hypothyroidism: 8 (4.37%) | |||

| Substance abuse/dependence, N (%) | n/a | 57 (31.14) | n/a |

| Diagnosis, N (%) | n/a | n/a | |

| Schizophrenia | 101 (55.2%) | ||

| Acute and transient psychotic disorders | 79 (43.2%) | ||

| Schizoaffective disorder | 3 (1.6%) | ||

| Duration of illness (months) | n/a | 7.90 (10.94) | n/a |

| Duration of treatment (months) | n/a | 3.90 (6.49) | n/a |

| Duration untreated (months) | n/a | 3.91 (9.48) | n/a |

| CHLPZ equivalent (mg)d | n/a | 365 (225) | n/a |

| Age of onset | n/a | 28.46 (7.48) | n/a |

| PANSS Positive Scale, M (SD) | n/a | 11.96 (4.03) | n/a |

| PANSS Negative Scale, M (SD) | n/a | 15.21 (5.82) | n/a |

| PANSS General Psychopathology Scale, M (SD) | n/a | 29.71 (8.15) | n/a |

| GAF, M (SD) | n/a | 69.21 (15.14) | n/a |

| CGI-S, M (SD) | n/a | 3.07 (1.35) | n/a |

Note: BMI, body mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression—Severity scale; CHLPZ, chlorpromazine; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IKEM, Institute of Clinical Experimental Medicine in Prague; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; n/a, not applicable; NIMHCZ, National Institute of Mental Health, Czech Republic; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; TGC, triglyceride.

aWe used the Welch two-sample t-test (unequal variance assumed), which relies on a Welch–Satterthwaite degrees of freedom adjustment.

bBMI was missing in 3 individuals.

cGlucose was available in 53% of participants, with remaining biochemical measures (cholesterol, HDL, LDL, TGC, and hsCRP) in 73%–75% of participants.

dAll FEP individuals received atypical antipsychotics, while 7 people were treated with a combination of atypical and first-generation antipsychotics.

Fig. 1.

Significant group difference in baseline BrainAGE between individuals with first episode of psychosis and controls (A), and significant predictors of a higher annual rate of brain ageing, including higher baseline BMI (B) in the whole sample, worsening global functioning (C), and increasing negative symptoms (D) between visits among individuals with FEP. BMI, body mass index; FEP, first-episode psychosis; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; PANSSN, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale Negative Scale.

During the 1.61 ± 1.22 years interval between the scans, the annual rate of brain ageing in individuals with FEP was 1.28 ± 2.40 years per 1 calendar year, which was not significantly greater than the expected rate of 1.0 (β = 0.28, t(218) = 1.59, P = .057). Among controls, the 1.07 ± 1.74 annual rate of brain ageing was also comparable to the expected rate of 1.0 (β = 0.07, t(186) = 0.51, P = .305). Similarly, the change in estimated brain age between the first and second visit was not significantly different from the interval between the scans in either group (FEP: β = 0.36, t(182) = 1.72, P = .090; controls: β = 0.20, t(154) = 1.12, P = .270). In addition, the annual rate of brain ageing did not significantly differ between the 2 groups (β = 0.21, t(333) = 0.93, P = .176).

In the whole sample, baseline BMI predicted the annual rate of brain ageing (β = 0.08, t(333) = 2.59, P = .010; figure 1). Specifically, for every 1-point increase in BMI, the annual rate of brain ageing increased by approximately an additional month. Even when we controlled for baseline BrainAGE, BMI remained associated with rate of change in brain age (β = 0.079, t(332) = 2.69, P = .007). In a model containing both BMI and diagnosis, only BMI (β = 0.08, t(332) = 2.54, P = .012) was significantly associated with the annual rate of brain ageing. When jointly modeling the association between baseline BMI, glucose, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, hsCRP, and annual rate of brain ageing, only BMI remained significant (β = 0.11, t(138) = 1.98, P = .049) (supplementary table S3).

Among individuals with FEP, none of the baseline clinical characteristics, including diagnosis, type and severity of symptoms, global functioning, or history of substance abuse, predicted the annual rate of brain ageing (supplementary table S2). Worsening of functioning between the visits (GAF; β = −0.04, t(164) = −2.48, P = .014; figure 1) and increases in negative (PANSS N; β = 0.11, t(175) = 3.11, P = .002; figure 1) and general psychopathology (PANSS G; β = 0.06, t(175) = 2.58, P = .011) were all associated with greater annual rate of brain ageing. Associations between follow-up variables and follow-up BrainAGE were consistent with the longitudinal analyses (supplementary table S4).

Antipsychotic Medications, BMI, Symptoms, and Brain Structure

The average duration of treatment at baseline was 3.90 ± 6.49 months and all participants received atypical antipsychotics. The baseline cumulative antipsychotic exposure was associated with higher BMI (β = 0.01, t(168) = 4.23, P < .001), but not with baseline BrainAGE (β = 0.003, t(168) = 1.37, P = 0.174), or with annual rate of brain ageing (β = 0.002, t(169) = 1.11, P = .269). At follow-up, cumulative antipsychotic exposure was associated with both higher BMI (β = 0.003, t(142) = 3.19, P = .002) and higher BrainAGE (β = 0.003, t(145) = 2.73, P = .007; supplementary table S4). When modeled jointly, only antipsychotic exposure (β = 0.003, t(141) = 2.14, P = .033), but not higher BMI (β = 0.17, t(141) = 1.74, P = .084), was associated with higher BrainAGE at follow-up, with no interaction between the 2. The VIF for BMI (1.09), antipsychotic dose (1.06), and duration of treatment (1.14) did not suggest multicollinearity among these measures.

The antipsychotic dose at the first visit was associated with PANSS N (β = 7.28, t(170) = 2.46, P = .014), PANSS P (β = 18.01, t(170) = 4.41, P < .001), and PANSS G (β = 7.06, t(166) = 3.25, P = .001). This pattern changed at follow-up, when PANSS N was associated with the cumulative exposure (β = 11.97, t(144) = 2.14, P = .034), while PANSS P and G were not. When modeled jointly and controlling for BMI and age, only PANSS N, but not the cumulative medication exposure, was a significant predictor of BrainAGE at follow-up (β = 0.25, t(139) = 2.90, P = .004).

Discussion

Relative to controls, individuals with FEP, and especially those with more negative symptoms and lower functioning, showed advanced BrainAGE already during their first episode. The diagnosis of FEP was not associated with accelerated brain ageing over time. The annual rate of brain ageing in FEP was not significantly different from expected rate of change or from the annual rate of brain ageing in controls. At the same time, those FEP individuals who showed greater worsening of clinical outcomes, ie, increasing rates of negative and global symptoms and worsening in functioning between the visits, also demonstrated faster brain ageing. Importantly, across both cohorts, higher baseline BMI predicted acceleration of brain ageing in the next 1–2 years.

This is the first study to prospectively investigate the association between BMI and BrainAGE. In the whole sample, one additional point in BMI was associated with approximately an additional month of brain ageing each calendar year. This is in keeping with other prospective studies indicating that changes in BMI precede changes in brain volumes.37–45 This is further supported by a mendelian randomization study, which suggested a causal relationship between obesity and whole brain or gray matter volumes46 and by studies showing that treatment of obesity slowed brain atrophy.39,41,47,48 In addition, our findings extend the previous literature by suggesting that the effects of obesity are sufficiently diffuse to affect a composite measure of brain structure, such as BrainAGE.

Some longitudinal studies reported progressive regional brain atrophy in FEP,19,49 while others found no such changes.50,51 We did not find accelerated rate of brain ageing in FEP. Interestingly, the only previous study which also estimated brain age52 showed a very similar extent of brain ageing over time in schizophrenia, ie, 1.36 years/year, as compared to 1.28 years/year in our study. In addition to that study, we also showed that the annual rate of ageing was comparable between FEP and controls. Together with the already higher BrainAGE at baseline, this suggests that brain alterations in FEP may precede the illness onset, as also demonstrated by others.25,52–58 It is also possible that progressive brain changes occur only in some individuals with FEP. Indeed, while as a group FEP did not show progressive brain age changes, those with worsening functioning and increasing negative symptoms did demonstrate acceleration of brain ageing over time. This is remarkably consistent with 2 recent studies that also documented association between changes in neurostructural measures and worsening negative symptoms59,60 or global functioning.59 Interestingly, the baseline symptoms did not predict these longitudinal changes, making it more likely that the progressing brain alterations led to the worsening of clinical symptoms. Our findings support the hypothesis that there is heterogeneity in progressive brain changes in FEP, which may in part explain the heterogeneity in clinical outcomes and the inconsistent findings in previous studies.

We were particularly interested to test whether the obesitogenic effects of antipsychotic medications contributed to our findings and to the associations between antipsychotics and brain structure. Indeed, greater cumulative antipsychotic exposure was associated with higher BMI. When modeled jointly, only antipsychotic exposure, but not BMI, was associated with greater BrainAGE at the second visit. At least in the first years after initiation of treatment, the effect of antipsychotic medication on brain structure was not mediated by BMI. This is in keeping with other studies61,62 and may also be related to the fact that metabolic alterations in FEP may pre-date AP treatment63 or that most of the antipsychotic-related metabolic changes may happen in the first months of treatment,64 even prior to the first scan. We also cannot rule out that following a longer exposure, metabolic side effects could become more relevant for the association between antipsychotics and brain alterations.

Interestingly, we found association between cumulative antipsychotic exposure and greater BrainAGE only at Visit 2, but not at Visit 1. This pattern is congruent with 2 explanations. First, medications contributed to neurostructural alterations, but the duration of medication exposure at the first scan, ie, 3.90 ± 6.49 months, was too short for these effects to occur. Alternatively, medication dosage at Visit 1 primarily reflects symptoms, that are not associated with brain alterations, but over time the cumulative medication exposure becomes a more reliable proxy for symptoms that are associated with brain changes. Indeed, medications were most strongly associated with positive symptoms at Visit 1, but with negative symptoms at Visit 2. It is not surprising that higher doses of medications during hospitalization are primarily used to target positive symptoms, but following hospitalizations, medication exposure predominantly tracks negative symptoms. Importantly, it was negative, not positive symptoms, which were associated with brain age, as in another study,56 and with acceleration of brain ageing over time. When analyzed jointly, only the negative symptoms, but not the cumulative exposure to medications, remained associated with BrainAGE at follow-up. This is broadly similar to findings of another study, which also demonstrated a greater effect of symptoms than medications on longitudinal brain changes in FEP.65 All in all, our findings are most congruent with the explanation that individuals with more brain alterations showed more negative symptoms and required more medications over time.

We can only speculate about the mechanisms underlying the effect of obesity on brain structure. Interestingly, BMI was a stronger predictor of accelerated brain ageing than any individual metabolic measures, including glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, and hsCRP. This is in keeping with other studies66,67 and may be related to the relatively young age (29.29 years), absence of other pathology, and mostly normal levels of these biochemical measures. For the same reasons, contribution of vascular factors is also perhaps less likely. Obesity could also affect brain structure through adipokines, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance.13,68–73 Additionally, we may be detecting effects of lifestyle factors, including high-fat diets, lack of exercise, alcohol abuse, smoking, or psychosocial factors including poverty and disparities in health care/monitoring.74,75 While we do not precisely understand which of the obesity-associated factors contributed to brain alterations, the fact that an easy-to-measure index, such as BMI, predicted accelerated brain ageing is highly relevant for research and clinical practice.

While we know that neurostructural alterations are frequent in FEP and have clinical implications,59,60,65 we do not understand their origins and have no means of alleviating/preventing them. Our findings suggest that obesity contributes to brain alterations in FEP. This emphasizes the need to improve weight monitoring and management in FEP and to better integrate psychiatric and medical services. Such efforts may be important not only for prevention of adverse cardiovascular outcomes and increased mortality,2,72 but also to maintain brain health. In addition, identification of obesity as a risk factor for brain alterations in FEP could lead to testing of novel treatment methods, which would target the brain substrate rather than just the symptoms. Indeed, obesity-related structural brain abnormalities might be preventable or even reversible with lifestyle/surgical/medication interventions focused on weight management.39,41,47,48 Last but not least, these efforts may help address some of the clinical outcomes, which are frequent, but currently difficult to treat, such as negative symptoms and worse functioning.

With regards to limitations, this study was not designed to test the effects of medications and was not randomized. However, the longitudinal design allowed us to better clarify the temporal direction of associations. Biochemical measures were missing in some individuals and we did not study other psychiatric disorders. Waist circumference or waist-hip-ratio may show more extensive associations with gray matter, but BMI is much easier to acquire, correlates with other obesity-related alterations, and is by far the most frequently used measure.13,16 We excluded participants with large vessel disease but cannot rule out microangiopathy. Multiple factors such as chronic stress, lifestyle variables, including diet, exercise, and substance use/abuse, and socioeconomic factors impact clinical characteristics and potentially brain structure. Yet, they are difficult to quantify and track over time, especially in clinical populations. Thus, it is beneficial to use a composite measure, such as BMI, which captures a large part of variance related to these additional variables.

With 341 individuals, this is one of the largest prospective studies in FEP. Longitudinal studies continue to be rare but will be necessary to address many key questions which cannot be resolved by cross-sectional comparisons, such as issues of neuroprogression or reverse causality. All diagnostic and clinical assessments were performed by psychiatrists, which could have increased precision. Indeed, many of our findings had excellent face validity. It is noteworthy that the brain imaging measures corresponded with system-level clinical variables including negative symptoms and worse functioning not only cross-sectionally but also longitudinally. The additional strengths of this study include the focus on early stages of illness, use of an increasingly popular, cumulative measure of brain structure, and conservative application of machine learning, where we completely separated training from testing. The results were robust, replicated many of the previously reported findings, while providing some highly original and new information.

In conclusion, brain alterations in psychosis are manifest already during the first episode and over time become more pronounced in those with worsening clinical outcomes or higher baseline BMI. Importantly, BMI was the only baseline variable that predicted acceleration of brain ageing in the next 1–2 years. These findings support a causal role of obesity in brain alterations. Here, we have a risk factor for progressive accumulation of brain changes, which is easy to measure, modifiable, and frequently abnormal already in FEP. Consequently, improving weight monitoring and management may slow neuroprogression in individuals with FEP. As accelerated brain ageing tracked worsening of clinical outcomes, this could also help alleviate accumulation of negative symptoms and improve functioning over time. Future prospective studies should investigate the impact of weight management strategies on brain health and clinical outcomes in FEP and attempt to better understand the factors underlying the neuroprogressive effects of obesity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (142255), Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (16-32791A, NU20-04-00393), and Brain & Behavior Research Foundation Young and Independent Investigator Awards to T.H. The sponsors of the study had no role in the design or conduct of this study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(8):675–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):339–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, De Herdt A, Yu W, De Hert M. Is the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities increased in early schizophrenia? A comparative meta-analysis of first episode, untreated and treated patients. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, van Winkel R, Yu W, De Hert M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):306–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12):1350–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foley DL, Morley KI. Systematic review of early cardiometabolic outcomes of the first treated episode of psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(6):609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Galletly CA, Foley DL, Waterreus A, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors in people with psychotic disorders: the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(8):753–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, Inskip H. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bora E, Akdede BB, Alptekin K. The relationship between cognitive impairment in schizophrenia and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2017;47(6):1030–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calkin C, van de Velde C, Růzicková M, et al. Can body mass index help predict outcome in patients with bipolar disorder? Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):650–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Willette AA, Kapogiannis D. Does the brain shrink as the waist expands? Ageing Res Rev. 2015;20:86–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Janowitz D, Wittfeld K, Terock J, et al. Association between waist circumference and gray matter volume in 2344 individuals from two adult community-based samples. Neuroimage. 2015;122:149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dekkers IA, Jansen PR, Lamb HJ. Obesity, brain volume, and white matter microstructure at MRI: a cross-sectional UK Biobank Study. Radiology. 2019;291(3):763–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. García-García I, Michaud A, Dadar M, et al. Neuroanatomical differences in obesity: meta-analytic findings and their validation in an independent dataset. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43(5):943–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ronan L, Alexander-Bloch AF, Wagstyl K, et al. ; Cam-CAN . Obesity associated with increased brain age from midlife. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;47:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kolenic M, Franke K, Hlinka J, et al. Obesity, dyslipidemia and brain age in first-episode psychosis. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;99:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dietsche B, Kircher T, Falkenberg I. Structural brain changes in schizophrenia at different stages of the illness: a selective review of longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(5):500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dazzan P, Arango C, Fleischacker W, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and the prediction of outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a review of current evidence and directions for future research. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):574–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laidi C, Hajek T, Spaniel F, et al. Cerebellar parcellation in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(5):468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kolenič M, Španiel F, Hlinka J, et al. Higher body-mass index and lower gray matter volumes in first episode of psychosis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:556759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Franke K, Ziegler G, Klöppel S, Gaser C; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Estimating the age of healthy subjects from T1-weighted MRI scans using kernel methods: exploring the influence of various parameters. Neuroimage. 2010;50(3):883–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reddan MC, Lindquist MA, Wager TD. Effect size estimation in neuroimaging. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):207–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hajek T, Franke K, Kolenic M, et al. Brain age in early stages of bipolar disorders or schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(1):190–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirayasu Y, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, et al. Lower left temporal lobe MRI volumes in patients with first-episode schizophrenia compared with psychotic patients with first-episode affective disorder and normal subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(10):1384–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kasai K, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, et al. Progressive decrease of left superior temporal gyrus gray matter volume in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl. 20):22–33; quiz 34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Rutigliano G, et al. Diagnostic stability of ICD/DSM first episode psychosis diagnoses: meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1395–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33(6):766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Franke K, Luders E, May A, Wilke M, Gaser C. Brain maturation: predicting individual BrainAGE in children and adolescents using structural MRI. Neuroimage. 2012;63(3):1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Franke K, Gaser C, Manor B, Novak V. Advanced BrainAGE in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gaser C, Franke K, Klöppel S, Koutsouleris N, Sauer H; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . BrainAGE in mild cognitive impaired patients: predicting the conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e67346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Le TT, Kuplicki RT, McKinney BA, Yeh HW, Thompson WK, Paulus MP; Tulsa 1000 Investigators . A nonlinear simulation framework supports adjusting for age when analyzing BrainAGE. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wood SN. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models: estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J Roy Stat Soc B (Stat Methodol). 2011;73(1):3–36. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bobb JF, Schwartz BS, Davatzikos C, Caffo B. Cross-sectional and longitudinal association of body mass index and brain volume. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(1):75–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Honea RA, Szabo-Reed AN, Lepping RJ, et al. Voxel-based morphometry reveals brain gray matter volume changes in successful dieters. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(9):1842–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tuulari JJ, Karlsson HK, Antikainen O, et al. Bariatric surgery induces white and grey matter density recovery in the morbidly obese: a voxel-based morphometric study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(11):3745–3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mueller K, Sacher J, Arelin K, et al. Overweight and obesity are associated with neuronal injury in the human cerebellum and hippocampus in young adults: a combined MRI, serum marker and gene expression study. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mueller K, Möller HE, Horstmann A, et al. Physical exercise in overweight to obese individuals induces metabolic- and neurotrophic-related structural brain plasticity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yokum S, Stice E. Initial body fat gain is related to brain volume changes in adolescents: a repeated-measures voxel-based morphometry study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(2):401–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Enzinger C, Fazekas F, Matthews PM, et al. Risk factors for progression of brain atrophy in aging: six-year follow-up of normal subjects. Neurology. 2005;64(10):1704–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Driscoll I, Beydoun MA, An Y, et al. Midlife obesity and trajectories of brain volume changes in older adults. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(9):2204–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Windham BG, Lirette ST, Fornage M, et al. Associations of brain structure with adiposity and changes in adiposity in a middle-aged and older biracial population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(6):825–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Debette S, Wolf C, Lambert JC, et al. Abdominal obesity and lower gray matter volume: a Mendelian randomization study. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(2):378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shan H, Li P, Liu H, et al. Gray matter reduction related to decreased serum creatinine and increased triglyceride, hemoglobin A1C, and low-density lipoprotein in subjects with obesity. Neuroradiology. 2019;61(6):703–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mansur RB, Zugman A, Ahmed J, et al. Treatment with a GLP-1R agonist over four weeks promotes weight loss-moderated changes in frontal-striatal brain structures in individuals with mood disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(11):1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Magnotta V, Pierson R, Ziebell S, Ho BC. Progressive brain change in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(7):672–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Haukvik UK, Hartberg CB, Nerland S, et al. No progressive brain changes during a 1-year follow-up of patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2016;46(3):589–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Roiz-Santiáñez R, Ayesa-Arriola R, Tordesillas-Gutiérrez D, et al. Three-year longitudinal population-based volumetric MRI study in first-episode schizophrenia spectrum patients. Psychol Med. 2014;44(8):1591–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schnack HG, van Haren NE, Nieuwenhuis M, Hulshoff Pol HE, Cahn W, Kahn RS. Accelerated brain aging in schizophrenia: a longitudinal pattern recognition study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boos HB, Aleman A, Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol H, Kahn RS. Brain volumes in relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. De Peri L, Crescini A, Deste G, Fusar-Poli P, Sacchetti E, Vita A. Brain structural abnormalities at the onset of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of controlled magnetic resonance imaging studies. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):486–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cooper D, Barker V, Radua J, Fusar-Poli P, Lawrie SM. Multimodal voxel-based meta-analysis of structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging studies in those at elevated genetic risk of developing schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2014;221(1):69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Koutsouleris N, Davatzikos C, Borgwardt S, et al. Accelerated brain aging in schizophrenia and beyond: a neuroanatomical marker of psychiatric disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(5):1140–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gogtay N. Cortical brain development in schizophrenia: insights from neuroimaging studies in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(1):30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zipursky RB, Reilly TJ, Murray RM. The myth of schizophrenia as a progressive brain disease. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1363–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Akudjedu TN, Tronchin G, McInerney S, et al. Progression of neuroanatomical abnormalities after first-episode of psychosis: a 3-year longitudinal sMRI study. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tronchin G, Akudjedu TN, Kenney JP, et al. Cognitive and clinical predictors of prefrontal cortical thickness change following first-episode of psychosis. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2020;302:111100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jørgensen KN, Nesvåg R, Nerland S, et al. Brain volume change in first-episode psychosis: an effect of antipsychotic medication independent of BMI change. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Veijola J, Guo JY, Moilanen JS, et al. Longitudinal changes in total brain volume in schizophrenia: relation to symptom severity, cognition and antipsychotic medication. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e101689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Freyberg Z, Aslanoglou D, Shah R, Ballon JS. Intrinsic and antipsychotic drug-induced metabolic dysfunction in schizophrenia. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zipursky RB, Gu H, Green AI, et al. Course and predictors of weight gain in people with first-episode psychosis treated with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lepage M, Makowski C, Bodnar M, Chakravarty MM, Joober R, Malla AK. Do unremitted psychotic symptoms have an effect on the brain? A 2-year follow-up imaging study in first-episode psychosis [published online ahead of print August 24, 2020]. Schizophr Bull Open. 2020;1(1). doi: 10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ward MA, Bendlin BB, McLaren DG, et al. Low HDL cholesterol is associated with lower gray matter volume in cognitively healthy adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Benedict C, Brooks SJ, Kullberg J, et al. Impaired insulin sensitivity as indexed by the HOMA score is associated with deficits in verbal fluency and temporal lobe gray matter volume in the elderly. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):488–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cox SR, Lyall DM, Ritchie SJ, et al. Associations between vascular risk factors and brain MRI indices in UK Biobank. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(28):2290–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wisse BE. The inflammatory syndrome: the role of adipose tissue cytokines in metabolic disorders linked to obesity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(11):2792–2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hajek T, Calkin C, Blagdon R, Slaney C, Uher R, Alda M. Insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, and brain structure in bipolar disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(12):2910–2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Parimisetty A, Dorsemans AC, Awada R, et al. Secret talk between adipose tissue and central nervous system via secreted factors—an emerging frontier in the neurodegenerative research. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Goldstein BI, Baune BT, Bond DJ, et al. Call to action regarding the vascular‐bipolar link: a report from the Vascular Task Force of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(5):440–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, De Block CE. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444(7121):875–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Newcomer JW. Metabolic syndrome and mental illness. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(suppl. 7):S170–S177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Manu P, Dima L, Shulman M, Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Correll CU. Weight gain and obesity in schizophrenia: epidemiology, pathobiology, and management. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(2):97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.