Abstract

Objective

To quantify the differences in viscosity of over a range of commercial food based formulas and home prepared blenderized feeds used for enteral feeding in the clinical management of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and GER-related aspiration in children with oropharyngeal dysphagia.

Methods

The viscosity of commercial and home blends was measured using 1) digital rotational viscometer and 2) International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative Syringe Flow Test. Additional testing was performed to determine the impact of added cereal, water flushes, and freezing/thawing on formula viscosity.

Results

There were significant variations in viscosity between commercial blends with values ranging from extremely to mildly thick by Syringe Flow Test. The highest centipoise (cps) value was 13,847 and the lowest 330 and 438 cps. Dilution of 240 mL of commercial blend with 30 ml, 60 ml and 90 ml of water resulted in a decrease in viscosity of 31%, 62% and 85% respectively. Exposure to one freeze/thaw cycle decreased viscosity by as much as 59–80% depending on the blend. Thickening conventional pediatric formulas with rice or oatmeal did not achieve consistency equivalent to most blenderized feeds.

Conclusions

Commercial food-based formulas and home prepared blends vary greatly in viscosity, ranging from thin to extremely thick liquids, with the majority achieving viscosity greater than thickened formula. Viscosity is reduced by addition of free water and with freezing and thawing. These data can inform the clinical choice of feeding regimen depending on the goals of nutritional therapy.

Introduction

Blenderized tube feeds, or the provision of table foods pureed in a blender and administered via enteral tube, are popular alternatives to conventional enteral formula in both adult and pediatric populations (1). These feeds have been shown to reduce pulmonary and gastrointestinal hospitalization risk in adults and children. Rates of respiratory disease are lower in children receiving blenderized diets (2), while gagging and retching symptoms following fundoplication improve with these diets (3). Adult studies have shown that viscous feeds decrease full column gastroesophageal reflux rates and daily fevers in neurologically compromised adults fed via enteral tube (4–6).

One of the proposed mechanisms by which these thick feeds may be beneficial is to reduce gastroesophageal reflux disease. Thickened feeds shift the food bolus to the distal stomach (antrum) and away from the cardia and lower esophageal sphincter, thereby reducing bolus movement into the esophagus. Based on this proposed mechanism, understanding variations in blend viscosity are critical to maximize the reflux benefit to reduce both gastrointestinal and pulmonary complications. Clinically, providers and patients have observed varying levels of thickness depending on recipe of home blend, selection of commercial brands, and blend processing (e.g. freeze/thaw cycle, addition of free water). Sullivan et al. reported the range of viscosity of hospital-prepared blenderized diets from 20 to > 45,000 centipoise, encompassing a wide range of thin liquids up to thick purées; however, the clinical utility is limited as the corresponding values of viscosity with individual recipes were not reported, commercial blends were not included and the impact of variations in blend handling in the home setting were not assessed (7).

Given the possible benefit of using blenderized feeds with high viscosity, we sought to quantify viscosity using a viscometer, classify fluid consistency, and determine the impact of common practices (such as freeze/thaw and dilution with water) on viscosity in order to better inform clinician choice when customizing a blend selection for patients. Fluid consistency was assessed using the Syringe Flow Test as outlined in the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI) Guidelines. This test is easily performed in clinical practice to assess flow rate for oral feeds.

Methods

Test Diets

Three home blends routinely used in clinical practice were selected for preparation. Home-made blends were created from 1) whole foods (using a variety of table foods such as chicken, pasta, green beans and milk); 2) commercially available baby food (e.g. pureed banana, carrots and chicken, combined with table foods and milk); and 3) pediatric conventional formula base (with the addition of pureed baby food and table food, see Supplemental Table for recipes). Home blends were prepared using Ninja Professional Blender (SharkNinja Operating LLC, Needham, MA, maximum 1200 Watt), and pureed until smooth. The following commercially prepared blenderized diets were assessed: Kate Farms Pediatric 1.2 (Kate Farms, Santa Barbara, CA), Compleat Pediatric and Compleat Organic Blend Chicken Garden (Nestlé Health Science, Lausanne, Switzerland), Nourish and Liquid Hope (Nutritional Medicinals, LLC, West Chester, OH), Pediasure Harvest (Abbott Nutrition, Chicago, IL), Real Food Blends Beef, Potatoes & Spinach, Real Food Blends Quinoa, Kale & Hemp and Real Food Blends Orange Chicken, Carrots & Brown Rice (Real Food Blends, Chesterton, Indiana).

Conventional formulas thickened with infant cereals are an alternate strategy to manage gastroesophageal reflux, and were used as a control. Elecare Jr. was prepared from powdered formula with standard 30 calorie/ounce recipe from the manufacturer (Abbott Nutrition, Chicago, IL). Pediasure 1.0 and Pediasure 1.5 ready to feed liquid formulations were also used (Abbott Nutrition, Chicago, IL). To assess the impact of added cereal on viscosity, Elecare Jr. was subsequently thickened with 1) rice infant cereal at 1 teaspoon per ounce or 2) oatmeal infant cereal at 1 teaspoon per ounce using typical guidelines for reflux management, and assessed immediately at time of thickening, then after 30 minutes and again after 60 minutes. Similarly, Pediasure 1.0 was thickened with rice at 1 teaspoon per ounce, and assessed immediately at time of thickening, then after 30 minutes.

Commercial blenderized diets and formula thickened with cereal are not labeled for use in gastroesophageal reflux management by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This in vitro study did not involve human subjects and therefore did not require approval by local Institutional Review Board.

Viscosity

Viscosity was assessed using the NDJ-5 digital viscometer (Vevor, Shanghai, China) in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations. Range of detection is 1 to 100000 cP and measurement accuracy ± 3%. Spindles number 0 through 4 and rotational speed were selected as appropriate for estimated viscosity, ensuring that we achieved test value percentage rate of the full value of the measuring range in both extremes (< 15% and > 85%, or at the extremes of spindle and rotation settings). Viscosity was then calculated as the average of viscosity measurements obtained within the acceptable range of test value percentage (15–85%). Samples were analyzed at room temperature (between 61° and 75.1° Fahrenheit).

In addition, samples were assessed using the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI) Guidelines Syringe Flow Test (8). While this test was designed to assess the thickness of oral feeding, we felt that it would be important to assess blends using this because: 1) some blends are also fed orally in children with oropharyngeal dysphagia; 2) patients with more severe swallowing dysfunction may benefit from thickening enteral feeds to the same level as the feeds they are given orally to reduce gastric reflux aspiration risk; 3) this test is easily performed, interpreted and applied in any practice setting, as well as use by caregivers in the home setting, and 4) provides a shared language of fluid classification. Samples were instilled in a 10 mL syringe, and allowed to drip for 10 seconds before recording final syringe volume. The Fork Drip Test was used for moderately to extremely thick liquids.

Water Dilution

Water was added in increments of 30 mL (1 ounce) up to maximum of 90 mL (3 ounces) to 1 packet (240 mL) of Real Food Blends Quinoa, Kale and Hemp. Viscosity and Syringe Flow Test were measured after each dilution. Though there are multiple alternatives for dilution, water was selected due to standardized viscosity as well as routine use in clinical practice for tube flushing.

Freeze/Thaw

In order to replicate typical home conditions in which home blends are often prepared in large batches and frozen in aliquots, samples were frozen in a commercial home freezer (10° Fahrenheit), and were defrosted in a water bath (77° Fahrenheit) until achieving room temperature. Batches were frozen in their entirety, approximately 700–1000 mL (Supplemental Table), for the primary experiment. Additional testing was performed using samples frozen in 30 mL and 300 mL aliquots.

Results

Viscosity of Home and Commercially Prepared Blends

The viscosity of home and commercially prepared blends varied greatly. Real Foods Blends Orange Chicken (13,847 cP), Quinoa (6,331 cP), Beef (5,491 cP), and home blends created from whole foods (6,446 centipoise) met IDDSI criteria for extremely thick liquids. Compleat Organic Blends (4,864 cP), home blends made predominantly with baby food or a conventional formula base with added baby/whole foods (3,490 cP), and Liquid Hope (2,202 cP) were moderately thick. Nourish (1,774 cP) was mildly thick (1,363 cP), while Harvest was slightly thick based on IDDSI but with measured viscosity of 2,202 cP. Compleat Pediatric (438 cP) and Kate Farms Pediatric Standard 1.2 (330 cP) were classified as thin liquids (Table).

Table:

Viscosity of Enteral Feeds Assessed by Syringe Flow Test and Viscometer

| Formula Arranged by Syringe Flow Test Classification | Viscosity (cP) |

|---|---|

| Thin | |

|

| |

| Elecare Jr. | 2 |

| Elecare Jr. with rice 1 tsp/oz (time=0 min) | 6 |

| Elecare Jr. with rice 1 tsp/oz (time=60 min) | 17 |

| Pediasure 1.0 | 19 |

| Pediasure 1.5 | 19 |

| Elecare Jr. with rice 1 tsp/oz (time=30 min) | 22 |

| Elecare Jr. with oatmeal 1 tsp/oz (time=0 min) | 46 |

| Elecare Jr. with oatmeal 1 tsp/oz (time=30 min) | 51 |

| Elecare Jr. with oatmeal 1 tsp/oz (time=60 min) | 60 |

| Kate Farms Pediatric 1.2 | 104 |

| Compleat Pediatric | 330 |

|

| |

| Slightly Thick | |

|

| |

| Harvest | 1774 |

|

| |

| Mildly Thick | |

|

| |

| Pediasure 1.0 with rice 1 tsp/oz (time=0 min) | 438 |

| Pediasure 1.0 with rice 1 tsp/oz (time=30 min) | 442 |

| Nourish | 1363 |

| Home Blend from Baby Foods - DEFROSTED | 3588 |

|

| |

| Moderately Thick | |

|

| |

| Home Blend from Formula Base - DEFROSTED | 683 |

| Liquid Hope | 2202 |

| Real Food Blend - Quinoa, 8 oz with 60 cc water | 2396 |

| Home Blend from Whole Foods - defrosted | 2651 |

| Home Blend from Baby Food | 3347 |

| Home Blend from Formula Base | 3490 |

| Real Food Blend - Quinoa, 8 oz with 30 cc water | 4378 |

| Compleat Organic Blend - Chicken Garden | 4864 |

|

| |

| Extremely Thick | |

|

| |

| Real Food Blends – Beef, Potatoes & Spinach | 5491 |

| Real Food Blends - Quinoa | 6331 |

| Home Blend from Whole Foods | 6446 |

| Real Food Blend - Orange Chicken, Carrots & Brown Rice | 13847 |

|

| |

| Unable to Classify | |

|

| |

| Real Food Blend - Quinoa, 8 oz with 90 cc water | 937 |

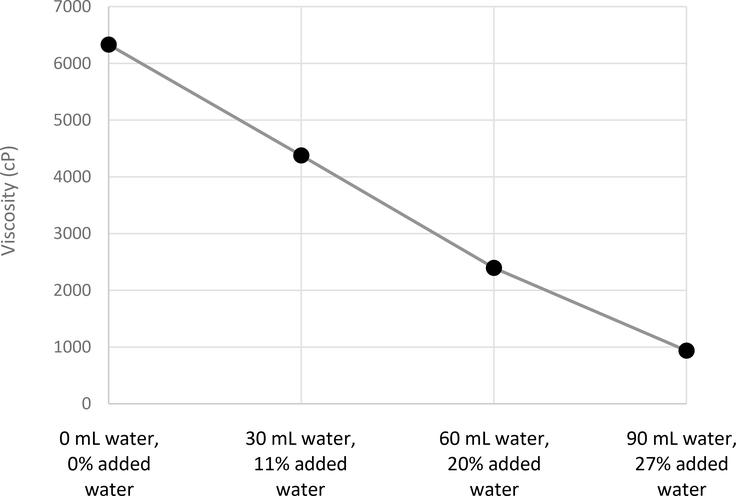

Effect of Added Water on Commercially Prepared Blend

To assess the impact of formula dilution (either the impact of diluting formula or using water flushes to chase the blend), water was added to 240 mL of Real Food Blends Quinoa, Kale and Hemp. Viscosity significantly decreased in a linear fashion from 6331 cP at baseline to 4378 cP with 30 mL added water, to 2396 cP with 60 mL added water, and to 937 cP with 90 mL added water. With each 30 mL of added water, viscosity was reduced by 50% (Figure 1). Dilution with 30 or 60 mL of water changed the IDDSI classification from extremely thick to moderately thick (Table). Dilution with 90 mL water resulted in inability to perform Syringe Flow Test due to settling sediment within the syringe. However, when particulate matter was strained using a fine kitchen strainer, consistency was classified as slightly thick. While using a strainer is not done clinically, we felt that it was important to highlight some of the limitations of the IDDSI test alone; without straining, the formula would classify as much more viscous than in actuality due to clogging in the syringe.

Figure 1:

Effect of Added Water on Viscosity of Commercial Blenderized Feed.

Effect of Freeze/Thaw Cycle on Home Prepared Blends

Exposure of a full batch of home blends to one freeze/thaw cycle decreased measured viscosity of home blend from whole foods (6,446 to 2,651 cP, decrease of 59%), and home blend with formula base (3,490 to 683 cP, decrease of 80%; Figure 2). However, IDDSI classification did not change. When frozen in 300 mL aliquots, home blend with formula base decreased in measured viscosity by 10%, but increased by 48% using 30 mL aliquots, without altering IDDSI classification of moderately thick. In contrast, home blend made from baby foods decreased from moderately to mildly thick IDDSI categories without substantially changing measured viscosity (3347 to 3588 to cP, an increase of 7%; Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Effect of Freeze/Thaw Cycle on Viscosity of Home Made Blenderized Feeds. Dark grey bars indicate fresh preparations; light grey indicate defrosted preparations.

Effect of Cereal Thickeners and Time

Elecare Jr. with rice cereal added to standard reflux recommendations (1 teaspoon per ounce) thickened minimally from 2 cP to 6 cP. By 30 minutes, viscosity increased to 22 cP, and remained stable by 60 minutes at 17 cP. In contrast, Elecare Jr. with oatmeal added in identical quantities thickened from 2 cP to 46 cP, and remained stable over time (51 cP at 30 minutes and 60 cP at 60 minutes). Of note, all preparations utilizing Elecare Jr. remained characterized as thin liquids despite added cereal. Pediasure 1.0 thickened substantially with 1 teaspoon of cereal per ounce of rice cereal added to reflux recommendations (from 19 cP to 438 cP), and was unchanged with time. This preparation with 1 tsp of cereal per ounce was classified as mildly thick by the IDDSI Syringe Flow Test (Table).

Discussion

Viscosity of blenderized diets varies significantly between different commercial and home prepared blends. Home prepared blends vary depending on underlying recipe, ranging from extremely thick (created from whole foods) to moderately thick formulations (predominantly baby food, or conventional formula base along with added baby food and whole foods). Commercial food-based formulas vary even more widely, with some meeting criteria for thin liquids (Kate Farms Pediatric 1.2 and Compleat Pediatric), slightly thick (Harvest), mildly thick (Nourish), moderately thick (Compleat Organic Blends, Liquid Hope) and extremely thick (Real Food Blends). Within the brand of Real Food Blends, there was variability in measured viscosity between recipes, though fluid characterization remained consistent. This study confirms patient and provider observations that viscosity varies greatly between different blends. This study also highlights that clinicians need to have a thoughtful approach to choosing blends based on blend viscosity and suspicion for gastroesophageal reflux related aspiration, in contrast to the current climate in which blends are chosen based on insurance coverage.

We also investigated the impact of other clinical practices on viscosity. For example, families will often prepare a large batch of home blends at one time, selecting a portion to freeze and later re-thaw. Based on our results, freezing and thawing results in significant and unpredictable changes in viscosity which may impact tolerance and outcomes. Indeed, substantial food science literature suggests that blend composition may have a great impact on freeze/thaw viscosity results (9–12), likely due to the complex dynamics of the freeze-thaw cycle (13, 14). Dilution of commercial blends is often recommended by the medical team to increase free water intake, or can occur with flushing of gastrostomy tubes following blend administration (though the latter effects in vivo are not well understood and will vary depending on the degree of gastric mixing). However, this practice resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in viscosity and thinning of liquid by IDDSI classification.

Thickened feeds are an alternative to blenderized diets for management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This study demonstrates minimal effect of thickening Elecare Jr. with rice cereal, while Pediasure 1.0 thickened substantially with rice cereal. While not entirely clear, this observation may be due to the fact that milk proteins may adsorb to rice particularly effectively (15). Elecare Jr. did thicken in response to oatmeal cereal, and therefore may be the preferred approach for reflux management in the population requiring elemental feeds. These cereal-thickened formulas were classified, in our study, as a thin liquid and were significantly lower in viscosity compared to all commercial food-based formulas and home prepared blends with the exception of Compleat (Nestlé Health Science) and Kate Farms Pediatric 1.2 (Kate Farms). In contrast to the recent study of Koo et al (16) investigating commercial thickeners in infant formula, we did not detect a change in viscosity over time with cereal-based thickeners suggesting that, if used, the formula can be fed immediately after mixing.

Our study highlights the importance of investigating both measured viscosity by viscometer and the IDDSI Syringe Flow test since there were differences in the results. This was most evident in the freeze/thaw experiment, but we also found that, for example, Harvest (Abbott Nutrition) met IDDSI criteria for slightly thick while the measured viscosity was closer to that observed in liquids classified as mildly to even moderately thick. While the IDDSI is easy to perform and widely implementable, there are some limitations that could result in erroneous conclusions. For example if sediment clogs the test syringe, families may conclude that a formula is more viscous than it actually is because the liquid cannot get past the clogging particles. Prior to the IDDSI, the National Dysphagia Diet classified liquids as thin based on viscosity 1–50 cP; Nectar-like 51–350 cP; Honey-like 351–1,750 cP; Spoon-thick >1,750 cP (17). The IDDSI has thoughtfully eliminated measured viscosity from the definition, citing importance of other parameters of flow rate, including variations in in vitro vs in vivo flow characteristics and non-Newtonian fluid characteristics (8). Therefore, both tests (measurement by viscometer and by Syringe Flow Test) may yield important but different information for clinical management. In addition, viscosity alone may not be the primary driver of effects on gastrointestinal motility including reflux and gastric emptying. Specifically, these parameters can be affected by the nutrient profile (e.g. fat and protein content) of the diets, as well as gastrointestinal microbiome composition.

Strengths of this study are that 1) a wide variety of commercial food-based formulas and home prepared blenderized diets were assessed; 2) viscosity was measured in two ways, using viscometer and the IDDSI Syringe Test; and 3) conditions used in typical home management were assessed, i.e. using home blender, home freezer and formulations at room temperature. The primary limitations to these data are that 1) not all formulations of each brand were assessed; 2) effects of commercial thickeners were not assessed, but may be more effective thickening agents compared to rice-based thickeners based on recent data in infant formula (16); 3) data are in vitro, and in vivo gastric acid may have an impact on viscosity of added starch; 4) blends may be diluted with gastric juices or separate into particulate matter and supernatant in vivo such that there are reductions in effective viscosity that cannot be estimated with the current experimental design and 5) effects of viscosity on tube clogging were not assessed, though mitigating strategies such as administering as bolus feeds via syringe or gravity can be employed (18). However, to this latter point, based on our data, we cannot recommend diluting formulas to prevent tube clogging since dilution has such a significant impact on viscosity.

In summary, this study provides critical data to guide clinical decisions regarding formula selection. Low viscosity formulas such as Kate Farms and Compleat may not be ideal for patients fed via gastrostomy with significant reflux, in whom extremely thick or possibly moderately thick liquids may have a beneficial impact (5). In addition, viscosity is substantially reduced by addition of free water and use of a freeze/thaw cycle, so providers should exercise caution with these recommendations in the setting of clinical concern for gastroesophageal reflux and/or aspiration. Future studies investigating the optimal viscosity for reflux management are critically and urgently needed to guide evidenced-based formula selection.

Supplementary Material

What is known

The importance of optimal thickening of oral feeds for management of oropharyngeal dysphagia is well known; however, thickening enteral tube feedings may be critical for the management of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and GER-related aspiration, though optimal thickening for management is not well described.

Commercial food based formulas and homemade blenderized diets which vary widely in ingredients are increasingly used for reducing gastroesophageal reflux and related aspiration in the setting of oropharyngeal dysphagia, and control of other gastrointestinal symptoms.

What is new

Commercial food-based formulas and home prepared blenderized diets vary greatly in viscosity and International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative fluid characterization

Measured viscosity and fluid characterization of blends are reduced by dilution with water and freeze/thaw cycle

Thickening of conventional formula to current reflux guidelines is unlikely to reach viscosity achieved by the majority of blenderized feeds

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Supported by National Institutes of Health R01 DK097112-01 and the Translational Research Senior Investigator Award.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Hron is an academic collaborator on a research study for which financial support was provided by AbbVie. Dr. Hron’s spouse is a consultant for I-PASS. Dr. Rosen is a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Epp L, Lammert L, Vallumsetla N, et al. Use of Blenderized Tube Feeding in Adult and Pediatric Home Enteral Nutrition Patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017;32:201–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hron B, Fishman E, Lurie M, et al. Health Outcomes and Quality of Life Indices of Children Receiving Blenderized Feeds via Enteral Tube. J Pediatr. 2019;211:139–45 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pentiuk S, O’Flaherty T, Santoro K, et al. Pureed by gastrostomy tube diet improves gagging and retching in children with fundoplication. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:375–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanie J, Suzuki Y, Akatsu H, et al. Prevention of late complications by half-solid enteral nutrients in percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding. Gerontology. 2004;50:417–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishiwaki S, Araki H, Shirakami Y, et al. Inhibition of gastroesophageal reflux by semi-solid nutrients in patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33(5):513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shizuku T, Adachi K, Furuta K, et al. Efficacy of half-solid nutrient for the elderly patients with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2011;48:226–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan MM, Sorreda-Esguerra P, Platon MB, et al. Nutritional analysis of blenderized enteral diets in the Philippines. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004; 13:385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cichero JA, Lam P, Steele CM, et al. Development of International Terminology and Definitions for Texture-Modified Foods and Thickened Fluids Used in Dysphagia Management: The IDDSI Framework. Dysphagia. 2017; 32:293–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weston S, Sorel, L., Clarke, T., Elverson, W. To determine the effect that freezing and thawing has on the viscosity of homemade blenderized formula to be fed by gastrostomy tube. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(Supplement 2):S345. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancela A, Maceiras, R., Delgado-Bastidas, N., Alvarez, E. Rheological Properties of Cooking Creams: Effect of Freeze-Thaw Treatment. Int J Food Eng. 2007;3:Article 6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ah-Hen KS, Vega-Gálvez A, Moraga NO, Lemus-Mondaca R Modelling of Rheological Behaviour of Pulps and Purées from Fresh and Frozen-Thawed Murta (Ugni molinae Turcz) Berries. Int J Food Eng. 2012;8:Article 6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato YaT Y Influence of Thawing Rate and Aging Temperature on Viscosity of Freeze-thawed Yolk and Low Density Lipoprotein. Agr Biol Chem. 1976;40:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Degner BM, Chung C, Schlegel V, Hutkins R, McClements DJ Factors Influencing the Freeze-Thaw Stability of Emulsion-Based Foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2014;13:98–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid DS. Overview of Physical/Chemical Aspects of Freezing. In: al. MCEe, editor. Quality of Frozen Foods. Dordrecht: Springer Science + Business Media; 1997. p. 10–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noisuwan AH Y; Wilkinson B; Bronlund JE Adsorption of milk proteins onto rice starch granules. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2011;84:247–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koo JK, Narvasa A, Bode L, et al. Through Thick and Thin: The In Vitro Effects of Thickeners On Infant Feed Viscosity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019; 69:e122–e128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Dietetic Association. In: Clayton J, ed. National dysphagia diet: standardization for optimal care. Chicago: Diana Faulhaber Publisher; 2002:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zettle S Deconstructing Pediatric Blenderized Tube Feeding: Getting Started and Problem Solving Common Concerns. Nutr Clin Pract. 2016;31 :773–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.