Abstract

New fetal therapies offer important prospects for improving health. However, having to consider both the fetus and the pregnant woman makes the risk-benefit analysis of fetal therapy trials challenging. Regulatory guidance is limited, and proposed ethical frameworks are overly restrictive or permissive. We propose a new ethical framework for fetal therapy research.

First, we argue that considering only biomedical benefits fails to capture all relevant interests. Thus, we endorse expanding the considered benefits to include evidence-based psychosocial effects of fetal therapies. Second, we reject the commonly proposed categorical risk and/or benefit thresholds for assessing fetal therapy research (e.g., only for life-threatening conditions). Instead, we propose that the individual risks for the pregnant woman and the fetus should be justified by the benefits for them and the study’s social value. Studies that meet this overall proportionality criterion but have mildly unfavorable risk-benefit ratios for pregnant women and/or fetuses may be acceptable.

Keywords: Fetal therapies; Fetal Diseases; Pregnancy; Ethics, research; Therapies, Investigational; Risk benefit assessment

Introduction

Over the past decades, scientific developments have led to important prenatal diagnostics and fetal therapies. For example, giving corticosteroids before preterm delivery for fetal lung maturation has become standard of care. With continued scientific progress and new tools like gene editing on the horizon (Ricciardi et al. 2018), novel surgical and pharmaceutical fetal therapies are in the pipeline that offer important prospects for improving health. Fetal therapy trials, however, also raise complex ethical challenges. Fetal therapies primarily benefit the fetus and the future child but also require intervention in the pregnant woman. How should their respective interests be assessed and balanced? Determining whether the risk-benefit ratio is appropriate, for both pregnant women and fetuses, is the main ethical challenge in assessing fetal therapy trials (Ashcroft 2016; McMann et al. 2014).

However, regulatory guidance on what constitutes an appropriate risk-benefit ratio in fetal therapy trials is limited. The US federal regulations for research with pregnant women and fetuses mandate that risks be the least possible for achieving the research objectives (45 CFR46.204(c)). Furthermore, these regulations allow research that offers a prospect of direct benefit for the fetus (or the pregnant woman), and research without such prospect of benefit provided it poses minimal fetal risks1 (45 CFR46.204(b)). Beyond these special requirements for research with pregnant women, the general research regulations apply (§46.201(d)), which require that risks to participants must be reasonable in relation to benefits to participants and the importance of the knowledge obtained (45 CFR46.111(2)).

These regulations leave important questions unresolved for fetal therapy trials with a prospect of direct benefit for the fetus, which is the focus of this paper. Specifically, the regulations provide no guidance on what constitutes a reasonable risk-benefit profile and whose risks and benefits should be proportional considering that both the fetus and/or the pregnant woman are research participants. Furthermore, the regulations do not specify absolute or net risk limits for studies with a prospect of benefit. In contrast, federal pediatric research regulations do impose a net risk limit on studies with prospect of benefit (i.e., the trial’s risk-benefit profile should be as least as favorable as available alternatives; 45 CFR46.405; Supplemental Table 1). For fetal therapy studies with prospect of fetal benefit and significant social value, the regulations may thus, in theory, allow very high risks for the pregnant woman or the fetus. In utero valvuloplasty trials, for example, involve high fetal risks: 20–30% mortality and, unfortunately, limited benefits (Meyer-Wittkopf et al. 2005). Open fetal surgery, which has been implemented for myelomeningocele and studied for several other fetal conditions, has significant risks for pregnant women (21% risk of complications, of which 5% were severe (Sacco et al. 2019)).

Beyond the regulations, several ethical frameworks have been advanced for evaluating when experimental fetal therapies are acceptable. These different ethical frameworks, however, diverge in their guidance, often use unclear terminology, and introduce categorical thresholds that are uncommon in research ethics, thereby limiting important emerging trials. For example, many frameworks make use of categorical thresholds with a floor for benefits (e.g., only life-threatening diseases or serious and irreversible diseases) that all studies must satisfy regardless of their risk level (Chervenak and McCullough 2007; GR 2009; Noble and Rodeck 2008; RAC 2000). However, categorical, one-size-fits-all thresholds are, depending on the case, inappropriately strict or unduly permissive since the appropriate analysis should involve a comparison of risks and benefits. Furthermore, unclear and divergent ethical frameworks could increase burdens on IRBs and researchers. Most importantly, unnecessarily restrictive decisions may hamper the development of beneficial therapies, and excessively permissive decisions may subject trial participants to disproportionate harms.

Given the limitations of both the regulations and existing ethical frameworks, clearer and more rigorous guidance for assessing the risks and benefits of fetal therapy trials is needed (Ashcroft 2016; Burger and Wilfond 2000; RAC 2000). In this paper, we thus propose a new framework for considering the acceptability of the risks and benefits of fetal therapy trials2. We defend two primary positions. First, we argue for an expanded way of considering what counts as a benefit, moving beyond a narrow medical view to include evidence-based psychosocial benefits to both the fetus and the pregnant woman. Second, we propose a new, nuanced framework, avoiding categorical thresholds, to help investigators and IRBs analyze and weigh risks and benefits for the fetus and the pregnant woman.

This paper is composed of three parts. Part 1 identifies the relevant risks and benefits of fetal therapies. Part 2 considers how to weigh the identified risks and benefits in determining whether a trial is ethical. Part 3 covers other research ethics challenges for fetal therapies: social value, scientific validity, and informed consent.

Part 1. The relevant risks and benefits

One of the cornerstones of assessing the acceptability of clinical trials is a process of weighing the potential benefits and risks to individual research participants (Emanuel et al. 2000; NCPHS 1979). This is more complex in fetal therapy trials. As the fetus cannot be accessed without an intervention on the pregnant woman, risks and benefits to both the pregnant woman and the fetus are relevant. Complicating the analysis further, the interests of the pregnant woman and the fetus are interdependent but not necessarily aligned. Of note, we presuppose that fetuses have interests after a woman has decided not to terminate, as interventions can affect the well-being of the anticipated future child (and, depending on your views, the fetus for its own sake) (Chervenak and McCullough 2007; Flake 2001; GR 2009). This does not necessarily imply that fetuses are persons, have rights, and/or should be regarded as separate patients (R.M. Antiel 2016; Ashcroft 2016); these issues are outside the scope of this paper.

Fetal benefit

Fetal therapies aim to provide medical benefit to the fetus and/or future child/adult that is often not achievable postnatally. For example, some conditions lead to irreversible damage before birth (Mattar et al. 2011; Morris et al. 2010), making prenatal interventions necessary to prevent, diminish or halt such harms. Furthermore, unique aspects of fetal physiology can make fetal therapies more effective (Mattar et al. 2011; Ye et al. 2001).

However, assessing potential fetal benefits raises some challenges. While the prospect of benefit is difficult to assess in most early phase trials, this uncertainty is exacerbated for fetal therapies. Besides limited direct knowledge of the physiology of living fetuses, the extent of benefits frequently depends on the severity of the disease, which can be difficult to predict in utero. Practically, excluding fetuses with mild phenotypes, a strategy proposed to maximize benefits of experimental fetal therapies (Harrison et al. 1982), may not be possible. In these uncertain cases, investigators and IRBs may consider whether a range of potential benefits is sufficient (i.e., benefits for both fetuses with a severe phenotype and for fetuses with a mild phenotype) and the prevalence of the different phenotypes.

Furthermore, the extent to which early phase fetal therapy studies should be regarded as offering prospect of benefit is unclear, given the uncertain likelihood of benefits. In assessing the prospect of benefit, investigators and IRBs consider preclinical data, and, if available, results from previous, comparable studies or innovative therapy. Differentiating between trials with no prospect of benefit or a small prospect of benefit has significant (regulatory) implications, as the former can only involve minimal risk (§46.204(b)). Further, more specific guidance for determining prospect of benefit may provide more clarity for all stakeholders.

Fetal therapy also raises a major question about which possible benefits to consider in the ethical analysis. Prominent ethics guidance supports including only health-related potential benefits (Emanuel et al. 2000); IRB practice reflects that focus in that they usually consider a narrow, medical concept of benefit (Meyer 2013). However, a broader understanding of health (including mental and social wellbeing, or the ability to self-manage disease) is being adopted in other areas of health and health policy (Huber et al. 2011; Huber et al. 2016; WHO 1948). This broader scope more comprehensively captures how interventions may affect patients (Huber et al. 2011).

We argue that IRBs should take a broader view of well-being in evaluating fetal therapies. In research ethics, consideration of individual benefits is grounded in the principle of beneficence: “to act for the others’ benefit, helping them to further their important and legitimate interests, often by preventing or removing possible harms” (Beauchamp 2019). Fetal therapies are usually aimed at conditions present early in life, which are more likely to affect development and psychosocial well-being beyond the direct health effects of the disease. Young adults who have had chronic pediatric illnesses are, on average, less successful at achieving adult milestones such as finishing advanced education, finding employment, leaving the parental home, marrying, and becoming parents (Pinquart 2014). Insofar as there is evidence of psychosocial harms associated with a given condition, and a fetal therapy may alleviate or substantially reduce those harms, this would be a potential benefit. Precluding consideration of such benefits in IRB review fails to capture important interests of the fetus and future child.

There is precedent for IRBs to consider a broader scope of benefit from other areas in which psychosocial effects are prominent: some IRBs consider psychosocial effects in reviewing mental health and addiction protocols (Churchill et al. 2003). The Belmont report itself seemed open to a broader scope of benefits, stating ‘many kinds of possible harms and benefits need to be taken into account’, listing psychological harm as an example (NCPHS 1979). For most fetal therapies, psychosocial benefits would merely add to the intervention’s biomedical benefits. For example, fetal myelomeningocele repair provides biomedical benefit but also entails psychosocial benefits (e.g., higher quality of life, improved mobility, independent functioning, and in young children the ability to self-care) (Farmer et al. 2018; Houtrow et al. 2020). Counting both types of benefits is in our view ethically appropriate.

At present, the risks of surgical interventions and most pharmaceuticals are too substantial to be justified by psychosocial benefit alone. In theory, however, if a trial would have enough psychosocial benefits for the fetus to justify the intervention’s risks despite a lack of biomedical benefits, conducting such a trial might – in our view – be acceptable, in serving the interest of current and future fetuses. As the magnitude of psychosocial benefits is likely limited and their likelihood still uncertain, studies with only psychosocial benefits would need to be low risk (e.g., nutritional or lifestyle interventions, or some FDA Pregnancy Category A drugs).

It may be appropriate to assign different weights to psychosocial and biomedical benefits depending on the relevant contextual factors (e.g., degree of certainty about benefits, extent of benefits). We note that psychosocial benefits would qualify as direct benefits since they result directly from the tested intervention.

We appreciate that broadening the scope to include psychosocial fetal benefits and well-being raises an unresolved dilemma as to how to define and measure well-being. An objective, or objective-list, approach could focus on the likelihood of fetal therapies to contribute to elements on which there is consensus that they make people better off (e.g., autonomy, bodily health, protection of certain rights, and accomplishments) (Sharp and Millum 2018; Wolff et al. 2012). Alternatively, a subjective approach to well-being would focus on how much the fetal therapy might improve the future child/adult’s experiences or satisfy his or her preferences. Objective and subjective accounts of well-being will likely often point in roughly the same direction.

While arguing for one view over the other is beyond the scope of this paper, the selected approach can affect the perceived benefits of a study, especially when the accounts of well-being might diverge. For example, some objective accounts of well-being would suggest that individuals are better off without deafness, whereas that is not the experience for some members of the deaf community (Dennis 2004; Werngren-Elgstrom et al. 2003). Reducing cognitive impairment in Down syndrome (DS) (Bacharach 2016; Tamminga et al. 2017) would likely score well using objective accounts, which generally consider improved cognitive abilities to make people better off (e.g., by increasing autonomy) (Gottfredson and Deary 2004; Whalley and Deary 2001). Whether improving cognitive functioning improves the subjective well-being of individuals with DS is however an open empirical question (de Wert et al. 2017; Inglis et al. 2014). These cases also show that certain fetal therapies may offer medical benefits, but future children would not necessarily be better off in some meaningful psychosocial ways. This presents another way in which considering only narrowly defined medical benefits may inadequately capture the relevant interests.

Fetal risks

Determining the ethics of any fetal therapy study requires assessing the severity and likelihood of risks. Some prenatal therapies may be safer than postnatal therapies. For example, early exposure may induce immune tolerance to the vector and transgene of gene therapies and some stem cell therapies (Coutelle and Ashcroft 2012; Mattar et al. 2011; Morris et al. 2010).

Additional uncertainties may, however, make determining risks for experimental fetal therapies especially challenging. First, experimental therapies often entail unquantified risks: greater than zero but difficult to measure with further precision (RAC 2000). This epistemological uncertainty is compounded by the potential for some interventions during fetal development to cause diseases that appear later in life (Barker 1990). Second, the restrictions on and reluctance to conduct research with pregnant women have resulted in limited safety data for various interventions (Kukla 2016; Mattison 2013). As such, comparing the risks of the experimental therapy with similar compounds/procedures and assessing the risks of research-related interventions (e.g., diagnostic tests) is more challenging. Third, two fetal-specific risks are especially challenging to assess: the risks of an intervention resulting in fetal loss or the survival of a severely disabled child that otherwise would have miscarried (R.M. Antiel 2016; Ashcroft 2016; Macklin 1984). Some authors have described the latter as the worst possible outcome of fetal therapy (Evans et al. 1993), while others describe the difficulty of assessing whether a child would be better off not to be born (Ashcroft 2016). Further conceptual analysis should explore appropriate standards for the weight of uncertain risks of fetal therapies (Burger and Wilfond 2000).

Benefits for pregnant women

Some fetal therapies may provide direct biomedical benefits for pregnant women, for example, if the fetal disorder can cause obstetrical complications. Most fetal therapies, however, provide no direct health benefits for pregnant women (Gates 1999). As current bioethics guidance and IRB practice suggest that only direct health benefits should be considered (Emanuel et al. 2000), most fetal therapies would be characterized as “no prospect of direct benefit” for pregnant women. However, for many fetal therapies, we think this is likely a conceptual mischaracterization.

Although, to our knowledge, few comparative studies have assessed the psychosocial impact of fetal therapy on women and their families (Lyerly and Mahowald 2001), several chronic conditions in children are related to parental psychosocial problems and reduced quality of life (Barlow and Ellard 2006; Ekas et al. 2009; Lawoko 2007; Lv et al. 2009; Ones et al. 2005). Parents whose children have certain chronic illnesses also have more symptoms of anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and depression than the general population (Bruce 2006; Easter et al. 2015; Quittner et al. 2014; van Oers et al. 2014; Woolf-King et al. 2017). Pediatric intensive care admission even results in post-traumatic stress symptoms in up to 84% of parents (Nelson and Gold 2012). Fetal therapy may alleviate the burden of raising a child with a severe condition or disability (Flake and Harrison 1995; Lyerly and Mahowald 2001; Oerlemans et al. 2010; Smajdor 2011), for example, by reducing the demands on parents related to the life-long dependence of adult children with DS (de Wert et al. 2017; Inglis et al. 2014). Indeed, the two studies that directly assessed the psychosocial effects of fetal therapy on pregnant women showed that fetal repair of myelomeningocele results in less personal strain for parents and a lower family and social impact than postnatal repairs (R. M. Antiel et al. 2016; Houtrow et al. 2020).

Furthermore, there may be psychological benefits related to the woman’s decision to opt for fetal therapy, including recognition that she has done everything she could, relief from the stress and anxiety of waiting until after birth, and/or preventing the burden of pregnancy termination (Ashcroft 2016; Smajdor 2011; Turchetti et al. 2007). We note, however, that most benefits related to the woman’s decision to opt for fetal therapy are likely of limited magnitude and duration, such that even if evidence-based, they would only be assigned limited weight in a risk-benefit analysis. As such, these types of benefits by themselves are unlikely to ever be sufficient to justify risky research.

We endorse an expanded consideration of benefits for pregnant women of fetal therapies to include evidence-based psychosocial effects of having a healthier child (Lyerly and Mahowald 2001). When evidence shows that a fetal condition frequently negatively affects the well-being of pregnant women or, later, mothers, treating this condition may have meaningful psychosocial effects. Characterizing such therapies as having no prospect of benefit for women mischaracterizes women’s interests (for similar reasons as described for fetal benefits) and could result in unnecessarily restrictive policies.

There are two possible objections to this view. First, the psychosocial benefits for the woman of having a healthier child might be considered an indirect benefit, thus conflicting with the standard view against counting indirect benefits. The general rationale for excluding indirect benefits is to avoid the loophole that a theoretically limitless set of ancillary services and financial compensation could justify even the riskiest research, which could harm and exploit subjects. However, this concern is less relevant to counting psychosocial benefits, as investigators would be unable to ‘add’ an unlimited amount of evidence-based psychosocial benefits. Furthermore, several authors have stressed the importance of the special relationship between mother and child and the connection between women’s interests and the interests of their fetus/child (R.M. Antiel 2016; Harris 2000; Lyerly and Mahowald 2001; Mattingly 1992). For example, a broader, biopsychosocial model of health (Harris 2000; Mattingly 1992) suggests that the pregnant woman and her fetus are an integrated and dependent ecosystem, such that caring for one implicates the other (Mattingly 1992). These views suggest that the benefits we propose to include may be more ‘direct’ than is typically imagined in discussions about indirect benefits. For psychosocial benefits related to having a healthier child, this is supported by these benefits resulting from the intervention being tested, and not just from study participation.

Second, some oppose counting psychosocial benefits in the IRB review process, since only pregnant women and their families are well-positioned to weigh these types of considerations (Rodrigues and vd Berg 2014). We agree that pregnant women should decide on trial participation based on their personal judgments about risks and benefits. However, not including these benefits in IRB assessments may result in the trial being denied ethical approval due to unfavorable risk-benefit ratios, not ever giving individual women the opportunity to make their own decisions about participation. Because of the difficulty in quantifying psychosocial effects, such considerations should be grounded in data; the availability of evidence about the degree to which conditions and their therapies affect women may mitigate this concern. For many conditions, further research is needed to provide this evidence.

Risks for pregnant women

The severity, treatability, and likelihood of complications for pregnant women span a wide range. For example, it can differ between folic acid supplements (minimal risk) and open fetal surgery (16% risk of minor complications and 5% risk of severe complications (Sacco et al. 2019)). While available published reports do not describe maternal deaths caused by fetal surgery, some of the severe complications associated with fetal surgery can be life-threatening (Sacco et al. 2019). Beyond harms during or directly after an intervention, risks to pregnant women also include consequences for future pregnancies.

Assessing fetal therapy risks for pregnant women poses two particular challenges. First, beyond the usual uncertainty in clinical research, risks of many common procedures and drugs for pregnant women are somewhat unknown: while pregnancy changes maternal physiology and metabolism, research involving pregnant women is limited (Mattison 2013). Second, fetal therapies pose new, emotionally complex, and morally challenging choices to pregnant women (Ashcroft 2016). For example, having the choice to use an (experimental) fetal therapy may make pregnant women feel more responsible for their child’s possible poor health outcomes (Sheppard et al. 2016). Data are needed about these (long-term) psychosocial consequences. If significant, and if psychosocial benefits are considered, IRBs should also consider these psychosocial burdens (Ashcroft 2016)3.

Part 2. A new framework for assessing the acceptability of risks and benefits of fetal therapy trials

Most fetal therapies pose risks to pregnant women and fetuses while providing the possibility of direct health benefits only to fetuses (with possible psychosocial benefits to both pregnant women and fetuses). The most complex ethical question for IRBs in considering fetal therapies is the conflict between the asymmetrically distributed risks and benefits to the fetus and pregnant woman (Ashcroft 2016; Mattingly 1992; McMann et al. 2014; Oerlemans et al. 2010). The ethical injunction against harming one patient to benefit another is widely recognized (Mattingly 1992; Oberman 1999). However, exceptions exist, for example, in obstetrics and living organ donation (Macklin 1984).

Several ethical frameworks have been proposed for determining the acceptability of fetal therapies (Supplemental Table 2), although it is not always clear whether they refer to established therapies, research, or innovative therapy. Some frameworks were drafted for specific kinds of fetal therapy such as fetal surgery or gene therapy (Supplemental Table 2). Consensus remains elusive. In the following section, we argue that several criteria suggested in these frameworks diverge from general research ethics principles. For example, many frameworks make use of categorical thresholds for benefits that a study should meet regardless of its features (e.g. only life-threatening diseases). Most such categorical thresholds, we argue, are either too narrow or too permissive. Finally, we suggest a new framework for assessing whether the risks and benefits of fetal therapies are acceptable.

Minimizing risks and enhancing benefits

Some authors have suggested that fetal therapies are only justifiable when their effectiveness is proven (GR 1990; 2009; Noble and Rodeck 2008), or therapeutic success is guaranteed (GR 1990; 2009). While standards like this might be considered in clinical settings, it precludes experimental fetal therapies with uncertain efficacy, and thus almost all research.

Other proposed requirements include maximizing the benefits to the fetus (RAC 2000) and minimizing risks for the fetus (Chervenak and McCullough 2002; 2007; 2011; 2015; 2018; Chervenak et al. 2004; RAC 2000) and for pregnant women (RAC 2000). We endorse these requirements and would expand them to also encompass enhancing benefits for pregnant women. Minimizing risks and enhancing benefits are also endorsed by well-established ethical frameworks (Emanuel et al. 2000; NCPHS 1979). For example, enhancing benefits may entail including fetuses with more severe phenotypes (if this can be predicted in utero) or starting treatment early in gestation when it can have the most effects. Minimizing risks may, for example, include limiting the required additional procedures. We note that minimizing risks as far as possible for achieving the research objectives is not merely recommended but required by regulations (§46.111(a) and §46.204(c)).

Proportional risks, benefits, and social value

We reject the frequently proposed idea of absolute thresholds: a minimum threshold of benefits for the fetus and a minimum threshold of benefits and a maximum threshold of risks for pregnant women. Several authors have suggested that the fetal disease needs to be life-threatening (Sicard 2004) or at least cause serious and irreversible disease, injury, or disability (Chervenak and McCullough 2002; 2007; 2011; 2015; 2018; Chervenak et al. 2004; Deprest et al. 2011; GR 1990; 2009; GTAC 1998; Harrison et al. 1982; Noble and Rodeck 2008; RAC 2000; Sgreccia 1989; Ye et al. 2001). To assess the therapy’s benefits relative to a baseline, some authors require that the natural history of the disease be well documented (Deprest et al. 2011; Harrison et al. 1982; Papadopulos et al. 2005) and prognosis established (Deprest et al. 2011; Papadopulos et al. 2005). Other commentators have suggested there also should be at least some benefits (including psychosocial) for pregnant women (Lyerly and Mahowald 2001; Pendl 1988). Finally, several have suggested that the mortality risk for pregnant women should be low and the risk of disease, injury, or disability for pregnant women should be low or manageable (Chervenak and McCullough 2002; 2007; 2011; 2015; 2018; Chervenak et al. 2004; Rodrigues and vd Berg 2014). Others have suggested that the risks for pregnant women should be negligible (Noble and Rodeck 2008), minimal (Wataganara et al. 2011), not significant (Flake and Harrison 1995), or not serious (Sgreccia 1989).

We argue that these categorical, one-size-fits-all thresholds are, depending on the case, inappropriately strict or unduly permissive. Similar to research ethics in general, the appropriate analysis is a comparison of benefits and risks. We think a categorical approach is wrong for several reasons.

First, for fetal therapies with low risks to the fetus and the pregnant woman, moderate or small benefits to the fetus may acceptably justify the research. For example, conducting a randomized controlled trial to assess whether fish oil supplementation during pregnancy reduces the risk that the child will develop allergic disease (e.g., eczema, rhinitis) seems quite acceptable (Dunstan et al. 2003; Hansen et al. 2017).

Second, although benefits to pregnant women may justify riskier interventions, it seems unnecessary for all fetal therapies to require benefits for pregnant women. For instance, therapies with low risks for the fetus and the pregnant woman but only fetal benefits seem plausibly acceptable. This is analogous to general research ethics principles, in which studies without a prospect of benefit for adult participants are acceptable if their risks are justified by social benefit (Rodrigues and vd Berg 2014). If competent adults can accept risks to benefit unknown and future third parties, it seems that they can accept risks to benefit their own fetus.

Third, using proposed thresholds on risk for women would not allow for moderately risky procedures with huge potential benefits to the fetus (and, if applicable, to the pregnant woman). There are various cases like this that we currently accept, such as maternal-fetal surgery for severe fetal conditions and living organ donation. The planned EVERREST clinical trial, for example, will entail maternal gene therapy to try to increase fetal growth in pregnancies with severe early-onset fetal growth restriction (FGR) (Spencer et al. 2017). If successful, this might provide substantial fetal benefits, given the lack of existing therapies for this condition, which leads to stillbirth or the need for delivery before 28 weeks, with significant risk of neonatal mortality (19%) and severe morbidity (51%) (Lees et al. 2013; Spencer et al. 2017). Qualitative interviews about this trial suggested that stakeholders considered risks for the pregnant women acceptable, as long as they are not ‘major’ (Sheppard et al. 2016).

We note that few have suggested thresholds for fetal risks. High fetal risks – including the risk of fetal demise – may be acceptable for a chance of ameliorating very severe fetal conditions.

Finally, the use of categorical thresholds may also lead to erring on the side of being too permissive. A trial may offer benefits for the fetus and for the pregnant woman that meet the threshold, and be low-risk for pregnant women while still being inappropriate because, for example, the fetal risks are disproportionately high. While it may seem that this problem could be circumvented by introducing a risk threshold for the fetus, this would then result in the previously described problem of such a threshold being too restrictive in other cases.

For these reasons, we think that it is appropriate to move away from the categorical approaches that characterize the literature on fetal therapies. In our view, the current lack of an absolute risk threshold for fetal therapies in the regulations is appropriate. Additionally, we note that operationalizing any (ethical) framework requires analytic clarity about terminology such as ‘serious disease’, or ‘manageable risks’. In difficult cases, undefined terms may allow for subjectivity and bias in assessments (Brown et al. 2006).

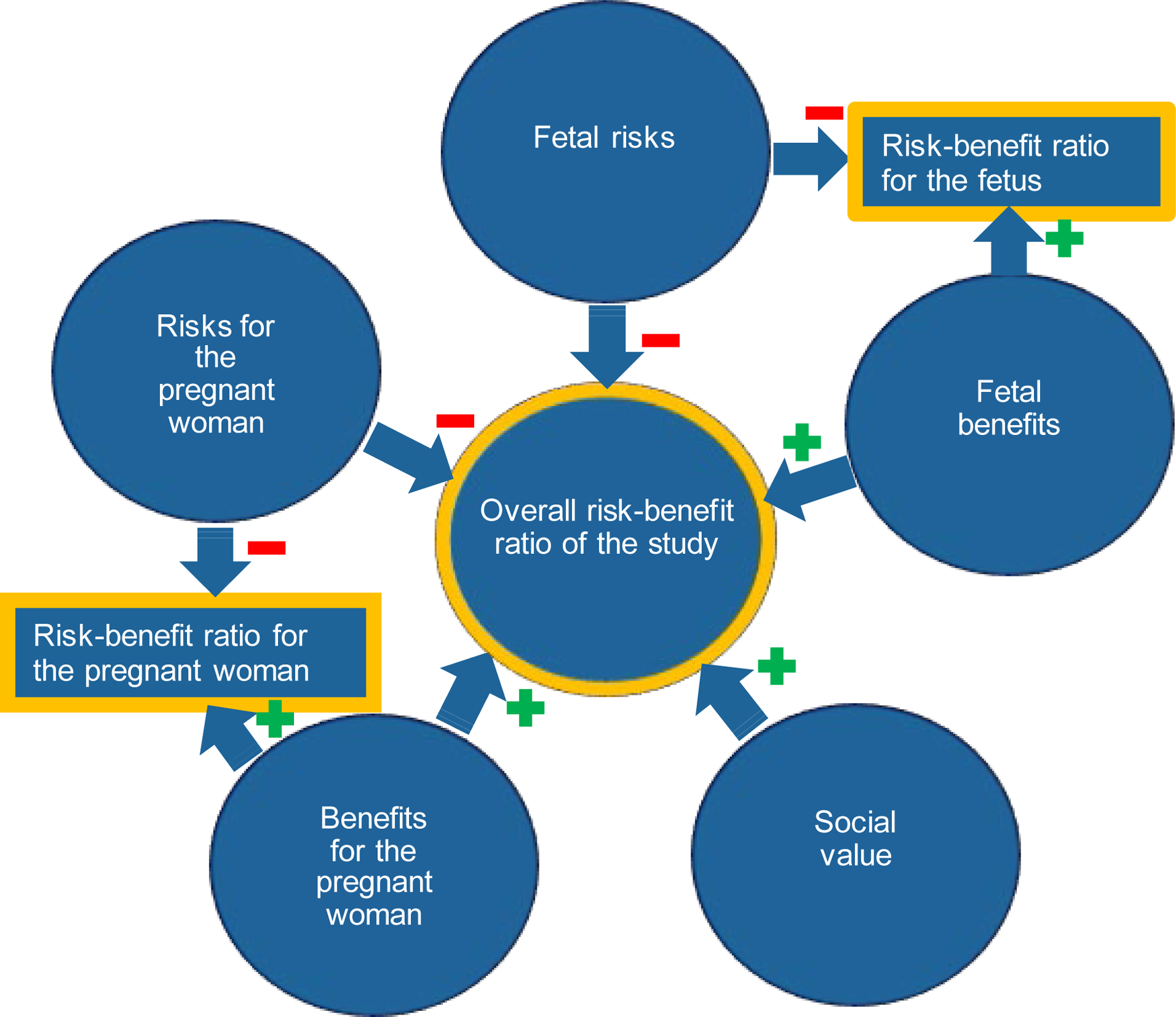

In research ethics in general, risks to participants should be outweighed by social value and benefits to participants (which may be non-existent) (Emanuel et al. 2000; NCPHS 1979); for that reason, categorical risk thresholds are uncommon. The procedural principle is that the more serious the condition, the greater the justifiable risk available to researchers attempting to ameliorate it in current and future patients. There is no compelling reason to reject a similar proportional standard for fetal therapies. As such, risks to the fetus and the pregnant woman ought to be outweighed by social value4 and benefits to both the fetus and pregnant woman (Figure 1). Others who have previously argued for proportionality in considering risks and benefits of fetal therapies suggested comparisons that are in our view incomplete, in that they did not include all five factors in our proposed framework: fetal risks, fetal benefits, risks for pregnant women, benefits to pregnant women, and social value. Specifically, previous accounts did not include risks and benefits to pregnant women and social value (Barclay et al. 1981), benefits to the fetus or pregnant women (Rodrigues and vd Berg 2014), benefits to pregnant women and social value (R.M. Antiel 2016; Burger and Wilfond 2000; de Wert et al. 2017; GR 1990; 2009), or social value (Flake and Harrison 1995). Some others do not define what should be proportional (Hayashi and Flake 2001; Sgreccia 1989; Smajdor 2011).

Figure 1.

Proposed elements of risk-benefit analysis for fetal therapy trials

In determining whether a specific fetal therapy study is ethical, we argue that three comparisons matter: the overall risk-benefit ratio of the study (i.e. risks for the fetus and the pregnant women, benefits for the fetus and the pregnant women, and social value), the risk-benefit ratio for the pregnant woman (i.e. the extent to which the benefits outweigh the risks or vice versa), and the risk-benefit ratio for the fetus.

Overall risk-benefit ratio of the study

Corresponding with general research ethics principles outlined before, we suggest that the overall risks of the study (i.e. to the fetus and the pregnant woman) should be lower than the overall benefits of the study (i.e. to the fetus, the pregnant woman, and society).

The risk-benefit ratio for the pregnant woman

For studies that meet those overall criteria, we think an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio for pregnant women can be acceptable (i.e. considering solely the interests of the pregnant women, study participation is anticipated to do more harm than good). Because, within the scope of research that provides more benefits than harms overall, we agree with others who have argued that competent adults should be allowed to choose to accept (disproportional) risks to themselves to benefit their child (R.M. Antiel 2016; Smajdor 2011). We would also highlight that studies without prospect of benefit for adult participants are considered acceptable if their social benefit justifies the risks. As argued previously, if competent adults can accept risks to benefit unknown and future third parties, it seems that they can accept risks to benefit their fetus and possibly themselves (i.e. psychosocial benefits) as well as future third parties. We anticipate that a significant proportion of fetal therapies may have an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio for pregnant women, even considering expanded benefits since the magnitude of psychosocial benefits is likely limited. An example of a fetal therapy with unfavorable risk-benefit for the woman may be fetal surgery for myelomeningocele5.

We think there is a point at which highly unfavorable risk-benefit ratios for pregnant women make research unacceptable. Under the principle of non-maleficence, investigators should not expose pregnant women, like other competent, consenting adults6, to excessive risks for the benefit of others. Exactly how high risks need to be to qualify as excessive is unclear. More conceptual work is needed to clarify where this limit is. In the interim, IRBs should use their judgment to assess whether the risks to pregnant women are excessive and, when in doubt, err on the side of caution.

The risk-benefit ratio for the fetus

There may also be cases that meet the overall proportionality criterion, in which the risks to the fetus may not be justified by benefits to the fetus, but are compensated by social value (possibly in combination with potential benefits to the pregnant woman). For example, in some early studies the benefits may be very uncertain and the risks low, yet these studies are likely to lead to novel and important advances in our ability to treat future fetuses. As long as these cases meet the overall proportionality criterion, and the harms are contained because the risk-benefit ratio for the fetus is only mildly unfavorable, we think such studies may be permissible. We, therefore, disagree with the suggestion that fetal benefits should always dramatically outweigh fetal risk (Flake and Harrison 1995). The uncertain risks of experimental interventions will, however, often have the practical effect of increasing the amount of benefit needed to justify a trial.

Furthermore, we imagine that in the future, one may propose moderately to risky fetal procedures for chronic diseases with a considerable disease burden (e.g. sickle cell anemia). Particularly for early trials, the fetal risks may significantly outweigh the uncertain benefits (similar to early studies in other areas of medicine (Roberts et al. 2004)). Still, the social value of these studies (i.e., possibly leading to a treatment or cure for a large number of future patients) may also be significant and could partially compensate for the individual risks. Further conceptual work is needed to determine whether and if so, under which conditions, trials that meet the overall proportionality criterion but with moderately unfavorable risk-benefit ratios to the fetus would be acceptable. We think there is a limit on how unfavorable the risk-benefit ratio for the fetus should be (even when the risks are compensated by the social value of the study). The extent to which it is acceptable to expose subjects to risks for the benefit of others differs between pregnant women and fetuses, as pregnant women can consent to trial participation. Furthermore, adults with decision-making capacity, including pregnant women, can currently accept (experimental) interventions with moderate net risks for themselves in other settings (e.g., open fetal surgery).

Of note, our proposal is more demanding than the current US federal regulations. The US federal regulations allow research with pregnant women when: “the risk to the fetus is caused solely by interventions or procedures that hold out the prospect of direct benefit for the woman or the fetus” (45 CFR46.204(b)). The regulations require that the risks to participants are minimized and are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits to participants, and the social value of the study (45 CFR46.111(2); 45 CFR46.204(c)). However, this condition could be satisfied by a trial that poses significant risks to subjects and offers them limited chance of benefit, but is socially very valuable. Furthermore, it does not provide guidance on how the risks and benefits should be distributed between the fetus and the pregnant woman. In our view the regulations are not sufficiently protective; we think there should be a limit on the extent to which risk-benefit ratios for pregnant women and fetuses can be unfavorable, even when the study is socially very valuable.

Availability of other treatments

Finally, the availability of other, non-experimental treatments (mostly postnatal), is relevant to risk-benefit analysis. Beyond what the current U.S. regulations require, we believe that experimental fetal therapy trials should be assessed in the context of existing treatments. Several authors have suggested that fetal therapy is only acceptable when no effective postnatal treatments exist (Deprest et al. 2011; GTAC 1998; Papadopulos et al. 2005; Sicard 2004; Ye et al. 2001). While rejecting this categorical approach, we agree that having an established therapy increases the standards for justifying the risks and uncertainty of experimental therapies, raising the bar for conducting research (Burger and Wilfond 2000). However, even if effective postnatal treatments exist, fetal therapies may be more effective and safer, for example when the disease causes irreversible damage in utero (Flake and Harrison 1995). In cases in which it is sufficiently plausible, based on preclinical data, that fetal therapy might have a more favorable risk-benefit profile than established interventions, human research may still be justified (Burger and Wilfond 2000; Flake and Harrison 1995; GR 1990; Sgreccia 1989).

Part 3. Beyond risk-benefit assessment

Risk-benefit assessment is not the only consideration in the ethical analysis of research. This section will discuss other research ethics criteria that provide specific challenges for fetal therapies: social value, scientific validity, and informed consent.

Social value

Our proposed framework follows general research ethics guidance in that risks for individuals should be compensated by individual and social benefits (Emanuel et al. 2000; NCPHS 1979). To be socially valuable, studies should evaluate a treatment that has the potential to improve health and well-being or increase knowledge that is relevant to that goal (Emanuel et al. 2000; NCPHS 1979). The frameworks presented in Supplemental Table 2 rarely include the social value of research as a relevant consideration7. For some, this may relate to the considered context: social value is relevant for research but not necessarily for clinical care or innovative therapy. While guidance can be drawn from general research ethics, the role social value plays in off-setting unfavorable risk-benefit ratios in this sensitive setting enhances the importance of creating standards for evaluating the clinical potential of a specific experimental fetal therapy.

Although each study should be assessed separately, fetal therapies have a relatively high potential to generate social benefit for several reasons. First, many current fetal therapies aim to improve health outcomes that cannot, or cannot to the same degree, be achieved postnatally. This is true, for example, for conditions causing irreversible damage before birth (Mattar et al. 2011; Morris et al. 2010). Furthermore, unique aspects of fetal biology may make some therapies safer (e.g. stem cell transplants that take advantage of fetal immunological tolerance (Vrecenak and Flake 2013)) and more effective (e.g. as the vector dose can be higher and more stem cells can be targeted) prenatally (Coutelle and Ashcroft 2012; Mattar et al. 2011; Morris et al. 2010). Fetal therapies frequently have more substantial and longer effects than postnatal therapies, such that they may do well in comparative value assessments (Barclay et al. 1981). Second, fetal therapies are often first of their kind, and thus are likely to increase knowledge and produce scientific spillovers (Lakdawalla et al. 2018).

To assess a therapy’s clinical potential (and thereby the study’s social value), scientific knowledge from preclinical studies and clinical studies are needed. The regulations require: “where scientifically appropriate, preclinical studies, including studies on pregnant animals, and clinical studies, including studies on nonpregnant women” (§46.204(a)). However, it is difficult to interpret the contours of what is “scientifically appropriate”. Other guidance similarly provides no clear standards about the appropriate levels of evidence to justify clinical (fetal therapy) studies (Chervenak and McCullough 2007; Kimmelman and Federico 2017; Mattar et al. 2011; RAC 2000). Preclinical requirements could include having well-designed and reproducible studies, in appropriate animal species (e.g. non-human primates), and/or in in-vitro models (e.g. organoids) (Chervenak et al. 2004; GR 2009; Kimmelman and Federico 2017; Mattar et al. 2011). Presumably, the appropriate amount of pre-clinical evidence to conduct research with pregnant women and their fetuses is commensurate to risk.

While risky therapies seem to be appropriate candidates for increasing the required level of pre-trial evidence, conducting early phase studies with healthy non-pregnant adults may actually be more difficult to justify for high-risk therapies, if these trials do not provide prospect of benefit to the participants (Burger and Wilfond 2000). Furthermore, enrolling healthy, non-pregnant subjects may be less (socially) valuable as no data about effects on the fetus or pregnancy-related physiology would be obtained. Researchers may also consider whether the study has a differential risk profile depending on which group participates. In some cases, the scientific goals of the study and a more favorable risk-benefit profile for pregnant women with affected pregnancies may make including this group more acceptable than conducting the trial with healthy volunteers. Of course, such a trial would need to have an acceptable risk-benefit profile for the fetus and the pregnant woman, as previously described, and have safeguards in place to protect them (e.g., see section on informed consent). Enrolling affected patients in first-in-human trials is not novel; some first-in-human trials involving chemotherapy and cell or gene therapies enroll affected patients given similar considerations (Dresser 2009).

Other sources of clinical data may also be explored first. If available, data about the therapy’s use for other indications or experience gained through innovative therapy can be examined. For example, instead of or prior to conducting an interventional study among healthy pregnant women carrying a fetus with Down syndrome (Bacharach 2016; Tamminga et al. 2017), an observational study could have explored the outcomes of DS pregnancies among pregnant women who used fluoxetine for their mental health (antidepressants are used in 8% of US pregnancies (Stewart and Vigod 2018)). Data on psychosocial harms experienced by children with a given condition or their mothers may provide preliminary data for a fetal therapy’s psychosocial benefits.

Establishing clearer guidance on minimum requirements before starting clinical studies may help navigate a range of potential pressures (e.g., scientific, patient-driven, financial, or the desire to act (R.M. Antiel 2016; Smajdor 2011)). Clearer evidence standards for human studies are especially important when consequences of inaccurate premises may be larger, such as when assessing complex risk-benefit ratios and potentially high-impact interventions, including many fetal therapies. Field-specific guidance, which considers risk-benefit profiles and the vulnerability of the study population, should be developed.

For a study to realize its social value, a sufficient number of participants should complete participation. In fetal therapy trials, investigators should consider recruitment and retention strategies, especially when difficulties in enrollment (e.g., rare diseases) or study completion (e.g., long and intensive follow-up) are anticipated. This may include outreach to community providers or reducing practical obstacles (e.g., reimbursing transportation or childcare) (Frew et al. 2014).

Finally, this paper brackets the important question about whether certain therapies should be developed. For example, fetal therapies may reduce valuable diversity in society, while conversely, they may remove barriers to equal opportunities (de Wert et al. 2017). As this falls outside of the scope of IRB review, we recommend that other stakeholders, such as investigators, bioethicists, funders, and research institutions consider the broader implications of developing new technologies.

Scientific validity

To produce scientific knowledge and thus create social value and avoid exploitation, research must be methodologically rigorous (Emanuel et al. 2000). Although fetal therapy trials do not pose unique questions relating to scientific validity, the interests involved do raise the need for context-specific guidance regarding methodological rigor.

First, a framework describing the types of appropriate first-in-human trial designs for different kinds of fetal therapy may benefit investigators and IRBs. For example, this may include when to enroll pregnant women with affected fetuses instead of healthy volunteers in phase 1 studies, as described above. Similarly, in the pediatric context, phase 1 trials are generally discouraged but are seen as being more acceptable for severe or life-threatening conditions as a last-resort treatment (Joseph et al. 2015). Furthermore, the extent to which different types of phase 1 fetal therapy studies should be regarded as offering prospect of benefit is unclear. In some cases, it might be possible to increase a trial’s prospect of benefit by changing the trial design. For example, some have argued that first-in-human gene therapy trials should be at phase 2/3 level, to include a reasonable prospect of benefit, which can also be better assessed (Coutelle and Ashcroft 2012). Exploring such options is consistent with our recommendation to enhance benefits.

Second, more guidance is needed regarding appropriate levels of follow-up to assess safety. How long should researchers provide or facilitate follow-up care for (former) research participants and which party, if any, is responsible for establishing and maintaining registries to detect and respond to adverse health outcomes appearing later in life (Farmer et al. 2018; McMann et al. 2014; Moon-Grady et al. 2017)? Fetal therapies may need more stringent requirements for follow-up since prenatal events can cause adverse health outcomes that appear decades later (Barker 1990). Identifying such risks is necessary for ethical decision-making (McMann et al. 2014) and to protect future fetuses.

Informed consent

Informed consent is a procedural requirement designed to respect persons and facilitate protection of their preferences and interests (Emanuel et al. 2000). While concerns about informed consent are frequently raised relating to fetal therapies (Burger and Wilfond 2000; Flake 2001; Götherström et al. 2017), procedural safeguards may mitigate them.

Fetal therapies raise particular concerns about pressure on pregnant women to consent (Chervenak and McCullough 2002; Deprest et al. 2011; Flake 2001; Ralston and Leuthner 2011). In obstetrics, women regularly value child health outcomes over their own (Bijlenga et al. 2011; Kok et al. 2008; Sheppard et al. 2016) and make sacrifices that exceed normal parental duties, possibly under pressure from society or involved individuals (R.M. Antiel 2016; Smajdor 2011; Van Calenbergh et al. 2017). In one study, 3% of women undergoing invasive fetal therapy felt pressure from family, colleagues, or nurses about having this procedure (Beck et al. 2013). Dominant norms of femininity that involve pregnant women and mothers acting in a self-sacrificing way can make pregnant women more vulnerable to pressure to act in their fetuses’ interest (Malacrida and Boulton 2012). Decisions to participate in research are, however, frequently constrained by societal expectations and values (Smajdor 2011). Concerns about pressure in consenting to fetal therapies resemble concerns about pressure in living organ donation between family members (R.M. Antiel 2016; GR 2009; Macklin 1984; Mattingly 1992). In living organ donation between family members, safeguards are installed for obtaining informed consent; a similar approach should be applied for fetal therapies (Chervenak and McCullough 2007; Ralston and Leuthner 2011). Fetal therapy investigators may draw from codes of conduct for protecting informed consent in living organ donation (R.M. Antiel 2016; Mattingly 1992). Undue pressure could also be decreased by providing non-directive counseling, time to reflect, independent consultants, or stressing that fetal therapy is a supererogatory act (R.M. Antiel 2016; Fletcher 1992; Mattingly 1992; RAC 2000).

Fetuses cannot provide informed consent. Pregnant women are generally considered appropriate proxy decision-makers for their fetuses. When fetal therapies solely benefit the fetus, paternal consent is also required by federal regulations, except when the prospective father is unable to consent (§46.204(e)). The currently required paternal permission for fetal therapy research is controversial (ACOG 2015; Chervenak and McCullough 2007; Ralston and Leuthner 2011). This differs from pediatric research in which only one parent’s permission is sufficient for studies with minimal risk or a prospect of benefit for participants (§46.408(b); Supplemental Table 1). However, unless the regulations change, the prospective father’s denial of permission would prevent trial participation for fetal therapy. Respecting pregnant women’s denial of consent to fetal therapy trials is less controversial, as she would herself undergo an experimental intervention and her autonomy, bodily integrity, and particularly claim to non-maleficence trump the beneficence claims on behalf of the fetus (Mattingly 1992; Nuffield 2006; Ralston and Leuthner 2011).

Conclusion

The main challenge in assessing fetal therapy trials is the risk-benefit analysis, which includes the (mutually dependent but not necessarily aligned) interests of both the fetus and the pregnant woman. Clear and adequate ethical or policy guidance for this assessment is currently lacking.

We have highlighted the challenges in identifying relevant risks and benefits for pregnant women and fetuses. We endorse an expanded way of considering benefits of fetal therapies, in which evidence-based psychosocial effects are considered.

Corresponding to general research ethics guidance, we propose a framework in which individual (i.e., for the pregnant woman and the fetus) risks should be lower than the individual benefits and the social value created by the research. Studies meeting this overall proportionality criterion with mildly unfavorable risk-benefit ratios for fetuses and/or moderately unfavorable risk-benefit ratios for pregnant women may be acceptable. Further research is needed to clarify whether and under what conditions less favorable risk-benefit ratios for the fetus or the pregnant woman may be acceptable.

Finally, we discussed three other research ethics criteria that pose particular challenges for fetal therapies: social value, scientific validity, and informed consent. Minimizing avoidable uncertainty by acquiring solid preclinical data is particularly important for fetal therapies with a questionably favorable risk-benefit ratio. More guidance is needed on what amounts to sufficient preclinical data for studies at different risk levels. Procedural safeguards may alleviate concerns about pressure on pregnant women to undergo fetal therapy.

We hope that this proposed ethical framework will help to endorse fetal therapy research that offers important prospects for improving health while protecting research participants from disproportionate harms.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: The views expressed are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

Although 45 CFR46.207 provides a mechanism for research not otherwise approvable.

In some cases, experimental (fetal) therapies can be provided as innovative therapy (i.e. with the primary purpose of benefitting the individual patient, as opposed to research that primarily aims to create generalizable knowledge) and therefore not be subject to the research regulations. Innovative therapy may be patient-driven: pregnant women asking their provider for a prescription after, for example, reading about experimental therapies online (apparently, some healthy women carrying a fetus with Down syndrome are requesting fluoxetine prescriptions outside the trial assessing its effectiveness in reducing cognitive impairment in Down syndrome (Bacharach 2016; Tamminga et al. 2017)(Rochman 2016)). Whether, and under which conditions (e.g., for how long), innovative therapy is appropriate, is an ongoing debate. However, even innovative therapy advocates argue that research should almost always precede adoption of new therapies into regular clinical practice (R.M. Antiel and Flake 2017; Chervenak and McCullough 2007; 2018; Flake 2001; Ralston and Leuthner 2011). This paper focuses on using experimental therapies in research.

Since the fetus is inside of the pregnant woman, she has to physically undergo the fetal therapy and the risks and benefits of this intervention to her need to be considered. This is not the case for pediatric therapies. Therefore, the proposed consideration of the risks and benefits for the pregnant woman does not imply that parental interests need to be considered in a similar way in pediatric research.

To be socially valuable, studies should evaluate a treatment that has the potential to improve health and well-being or increase knowledge that is relevant to that goal (Emanuel et al. 2000; NCPHS 1979). Social value is discussed in further detail on page 14.

Myelomeningocele is the most severe form of spina bifida, characterized by protrusion of the spinal cord and meninges. Fetal surgery appears to have more favorable long-term outcomes for affected children than postnatal repair, however it is associated with increased risks of significant obstetrical complications such as placental abruption (Cohen et al. 2014). To our knowledge, fetal surgery for myelomeningocele has no benefits for pregnant women beyond psychosocial benefits of improved outcomes for the future child (R. M. Antiel et al. 2016; Houtrow et al. 2020).

Whether acceptable unfavorable risk-benefit ratios for pregnant women should be higher, lower, or same as for other competent adults is an open question.

Two articles referred to social interests or value (Pendl 1988; Rodrigues and vd Berg 2014). Some additional authors have referred to the need for therapies to have a good possibility of being effective (Harrison et al. 1982; Sgreccia 1989) and to have been proven feasible in animal models (Deprest et al. 2011; Papadopulos et al. 2005), which may be understood as a recommendation relating to social value, risk-benefit analysis for individuals, or scientific validity.

References

- Acog. 2015. Acog committee opinion no. 646: Ethical considerations for including women as research participants. Obstet Gynecol 126, no 5: e100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antiel RM 2016. Ethical challenges in the new world of maternal–fetal surgery. Seminars in Perinatolog-y 40, no 4: 227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antiel RM, Adzick NS, Thom EA, Burrows PK, Farmer DL, Brock JW 3rd, Howell LJ, Farrell JA and Houtrow AJ. 2016. Impact on family and parental stress of prenatal vs postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. Am J Obstet Gynecol 215, no 4: 522.e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antiel RM and Flake AW. 2017. Responsible surgical innovation and research in maternal–fetal surgery. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 22, no 6: 423–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft R 2016. Chapter 14. Ethical issues in a trial of maternal gene transfer to improve foetal growth. In Clincial research involving pregnant women, eds Baylis F and Ballantyne A. Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach E Prozac trial to assess prenatal treatment of down syndrome. http://news.medill.northwestern.edu/chicago/prozac-trial-to-assess-prenatal-treatment-of-down-syndrome/.

- Barclay WR, Mccormick RA, Sidbury JB, Michejda M and Hodgen GD. 1981. The ethics of in utero surgery. JAMA 246, no 14: 1550–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ 1990. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 301, no 6761: 1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow JH and Ellard DR. 2006. The psychosocial well-being of children with chronic disease, their parents and siblings: An overview of the research evidence base. Child Care Health Dev 32, no 1: 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp T 2019. The principle of beneficence in applied ethics. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Zalta EN. [Google Scholar]

- Beck V, Opdekamp S, Enzlin P, Done E, Gucciardo L, El Handouni N, Van Mieghem T, Lewi L and Deprest J. 2013. Psychosocial aspects of invasive fetal therapy as compared to prenatal diagnosis and risk assessment. Prenat Diagn 33, no 4: 334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlenga D, Birnie E, Mol BW and Bonsel GJ. 2011. Obstetrical outcome valuations by patients, professionals, and laypersons: Differences within and between groups using three valuation methods. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 11: 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Truog RD, Johnson JA and Ecker JL. 2006. Do differences in the american academy of pediatrics and the american college of obstetricians and gynecologists positions on the ethics of maternal-fetal interventions reflect subtly divergent professional sensitivities to pregnant women and fetuses? Pediatrics 117, no 4: 1382–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M 2006. A systematic and conceptual review of posttraumatic stress in childhood cancer survivors and their parents. Clin Psychol Rev 26, no 3: 233–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger IM and Wilfond BS. 2000. Limitations of informed consent for in utero gene transfer research: Implications for investigators and institutional review boards. Hum Gene Ther 11, no 7: 1057–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervenak FA and Mccullough LB. 2002. A comprehensive ethical framework for fetal research and its application to fetal surgery for spina bifida. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187, no 1: 10–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervenak FA and Mccullough LB. 2007. Ethics of maternal-fetal surgery. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 12, no 6: 426–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervenak FA and Mccullough LB. 2011. An ethically justified framework for clinical investigation to benefit pregnant and fetal patients. Am J Bioeth 11, no 5: 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervenak FA and Mccullough LB. 2015. Professionally responsible maternal-fetal surgery: From innovation to research. Am J Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chervenak FA and Mccullough LB. 2018. The ethics of maternal–fetal surgery. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 23, no 1: 64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervenak FA, Mccullough LB and Birnbach DJ. 2004. Ethical issues in fetal surgery research. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology 18, no 2: 221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill LR, Nelson DK, Henderson GE, King NM, Davis AM, Leahey E and Wilfond BS. 2003. Assessing benefits in clinical research: Why diversity in benefit assessment can be risky. Irb 25, no 3: 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AR, Couto J, Cummings JJ, Johnson A, Joseph G, Kaufman BA, Litman RS, Menard MK, Moldenhauer JS, Pringle KC, Schwartz MZ, Walker WO, Warf BC and Wax JR. 2014. Position statement on fetal myelomeningocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol 210, no 2: 107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutelle C and Ashcroft R. 2012. Risks, benefits and ethical, legal, and societal considerations for translation of prenatal gene therapy to human application. In Prenatal gene therapy, eds Coutelle C and Waddington SN. New York: Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp R Well-being. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/well-being/.

- De Wert GM, Dondorp WJ and Bianchi DW. 2017. Fetal therapy for down syndrome: An ethical exploration. Prenat Diagn 37, no 3: 222–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C 2004. Genetics: Deaf by design. Nature 431, no 7011: 894–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprest J, Toelen J, Debyser Z, Rodrigues C, Devlieger R, De Catte L, Lewi L, Van Mieghem T, Naulaers G, Vandevelde M, Claus F and Dierickx K. 2011. The fetal patient – ethical aspects of fetal therapy. Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn 3, no 3: 221–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser R 2009. First-in-human trial participants: Not a vulnerable population, but vulnerable nonetheless. J Law Med Ethics 37, no 1: 38–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunstan JA, Mori TA, Barden A, Beilin LJ, Taylor AL, Holt PG and Prescott SL. 2003. Fish oil supplementation in pregnancy modifies neonatal allergen-specific immune responses and clinical outcomes in infants at high risk of atopy: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 112, no 6: 1178–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easter G, Sharpe L and Hunt CJ. 2015. Systematic review and meta-analysis of anxious and depressive symptoms in caregivers of children with asthma. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 40, no 7: 623–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekas NV, Whitman TL and Shivers C. 2009. Religiosity, spirituality, and socioemotional functioning in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 39, no 5: 706–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Wendler D and Grady C. 2000. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA 283, no 20: 2701–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MI, Robertson JA and Fletcher JC. 1993. Legal and ethical issues in fetal therapy. In The high-risk fetus: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management, eds Lin C-C, Verp MS and Sabbagha RE, 627–39. New York, NY: Springer New York. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer DL, Thom EA, Brock JW 3rd, Burrows PK, Johnson MP, Howell LJ, Farrell JA, Gupta N and Adzick NS. 2018. The management of myelomeningocele study: Full cohort 30-month pediatric outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 218, no 2: 256.e1–56.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flake AW 2001. Prenatal intervention: Ethical considerations for life-threatening and non-life-threatening anomalies. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery 10, no 4: 212–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flake AW and Harrison MR. 1995. Fetal surgery. Annu Rev Med 46: 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JC 1992. Fetal therapy, ethics and public policies. Fetal Diagn Ther 7, no 2: 158–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew PM, Saint-Victor DS, Isaacs MB, Kim S, Swamy GK, Sheffield JS, Edwards KM, Villafana T, Kamagate O and Ault K. 2014. Recruitment and retention of pregnant women into clinical research trials: An overview of challenges, facilitators, and best practices. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 59 Suppl 7, no Suppl 7: S400–S07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates E 1999. Two challenges for research ethics: Innovative treatment and fetal therapy. WOMEN’S HEALTH ISSUES 9, no 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götherström C, Hermerén G, Johansson M, Sahlin N-E and Westgren M. 2017. Stem cells and fetal therapy: Is it a reality? Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine 27, no 5: 166–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson LS and Deary IJ. 2004. Intelligence predicts health and longevity, but why? Current Directions in Psychological Science 13, no 1: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gr. 1990. The unborn child as a patient. Invasive diagnosis and therapy of the fetus. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands.. [Google Scholar]

- Gr. 2009. Care for the unborn child. In Monitoring Report Ethics and Health. The Hague: Centre for Ethics and Health: Health Council of the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Gtac. 1998. Gene therapy advisory committee: Report on the potential use of gene therapy in utero. In Disease markers, 151–54. London: Health Departments of the United Kingdom, Gene Therapy Advisory Committee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S, Strøm M, Maslova E, Dahl R, Hoffmann HJ, Rytter D, Bech BH, Henriksen TB, Granström C, Halldorsson TI, Chavarro JE, Linneberg A and Olsen SF. 2017. Fish oil supplementation during pregnancy and allergic respiratory disease in the adult offspring. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 139, no 1: 104–11.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LH 2000. Rethinking maternal-fetal conflict: Gender and equality in perinatal ethics. Obstet Gynecol 96, no 5 Pt 1: 786–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MR, Filly RA, Golbus MS, Berkowitz RL, Callen PW, Canty TG, Catz C, Clewell WH, Depp R, Edwards MS, Fletcher JC, Frigoletto FD, Garrett WJ, Johnson ML, Jonsen A, De Lorimier AA, Liley WA, Mahoney MJ, Manning FD, Meier PR, Michejda M, Nakayama DK, Nelson L, Newkirk JB, Pringle K, Rodeck C, Rosen MA and Schulman JD. 1982. Fetal treatment 1982. New England Journal of Medicine 307, no 26: 1651–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S and Flake AW. 2001. In utero hematopoietic stem cell therapy. Yonsei Medical Journal 42, no 6: 615–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtrow AJ, Thom EA, Fletcher JM, Burrows PK, Adzick NS, Thomas NH, Brock JW 3rd, Cooper T, Lee H, Bilaniuk L, Glenn OA, Pruthi S, Macpherson C, Farmer DL, Johnson MP, Howell LJ, Gupta N and Walker WO. 2020. Prenatal repair of myelomeningocele and school-age functional outcomes. Pediatrics 145, no 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, Horst H, Der V, Jadad AR, Kromhout D, Leonard B, Lorig K, Loureiro MI, Meer JWM, Van Der Schnabel P, Smith R, Weel C and Van Smid H. 2011. How should we define health? BMJ 343: d4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M, Van Vliet M, Giezenberg M, Winkens B, Heerkens Y, Dagnelie PC and Knottnerus JA. 2016. Towards a ‘patient-centred’ operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 6, no 1: e010091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis A, Lohn Z, Austin JC and Hippman C. 2014. A ‘cure’ for down syndrome: What do parents want? Clin Genet 86, no 4: 310–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph PD, Craig JC and Caldwell PHY. 2015. Clinical trials in children. British journal of clinical pharmacology 79, no 3: 357–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmelman J and Federico C. 2017. Consider drug efficacy before first-in-human trials. Nature 542, no 7639: 25–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok M, Gravendeel L, Opmeer BC, Van Der Post J.a.M. and Mol. BWJ 2008. Expectant parents’ preferences for mode of delivery and trade-offs of outcomes for breech presentation. Patient Education and Counseling 72, no 2: 305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukla R 2016. Equipoise, uncertainty, and inductive risk in research involving pregnant women. In Clinical research involving pregnant women, eds Baylis F and Ballantyne A, 179–96. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lakdawalla DN, Doshi JA, Garrison LP, Phelps CE, Basu A and Danzon PM. 2018. Defining elements of value in health care-a health economics approach: An ispor special task force report [3]. Value Health 21, no 2: 131–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawoko S 2007. Factors influencing satisfaction and well-being among parents of congenital heart disease children: Development of a conceptual model based on the literature review. Scand J Caring Sci 21, no 1: 106–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees C, Marlow N, Arabin B, Bilardo CM, Brezinka C, Derks JB, Duvekot J, Frusca T, Diemert A, Ferrazzi E, Ganzevoort W, Hecher K, Martinelli P, Ostermayer E, Papageorghiou AT, Schlembach D, Schneider KTM, Thilaganathan B, Todros T, Van Wassenaer-Leemhuis A, Valcamonico A, Visser GHA, Wolf H and Group TT. 2013. Perinatal morbidity and mortality in early-onset fetal growth restriction: Cohort outcomes of the trial of randomized umbilical and fetal flow in europe (truffle). Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 42, no 4: 400–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv R, Wu L, Jin L, Lu Q, Wang M, Qu Y and Liu H. 2009. Depression, anxiety and quality of life in parents of children with epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand 120, no 5: 335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyerly AD and Mahowald MB. 2001. Maternal-fetal surgery: The fallacy of abstraction and the problem of equipoise. Health Care Anal 9, no 2: 151–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin R 1984. The ethics of fetal therapy. In Biomedical ethics reviews · 1984, eds Humber JM and Almeder RT, 205–23. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malacrida C and Boulton T. 2012. Women’s perceptions of childbirth “choices”: Competing discourses of motherhood, sexuality, and selflessness. Gender & Society 26, no 5: 748–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mattar CN, Choolani M, Biswas A, Waddington SN and Chan JK. 2011. Fetal gene therapy: Recent advances and current challenges. Expert Opin Biol Ther 11, no 10: 1257–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly SS 1992. The maternal-fetal dyad. Exploring the two-patient obstetric model. Hastings Cent Rep 22, no 1: 13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison DR 2013. Ed. Mattison DR. Clinical pharmacology during pregnancy. San Diego: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Mcmann CL, Carter BS and Lantos JD. 2014. Ethical issues in fetal diagnosis and treatment. Am J Perinatol 31, no 7: 637–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MM 2013. Regulating the production of knowledge: Research risk-benefit analysis and the heterogeneity problem. SSRN Electronic Journal 65. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Wittkopf M, Kaulitz R, Abele H, Schauf B, Hofbeck M and Wallwiener D. 2005. Interventional fetal balloon valvuloplasty for congenital heart disease—current shortcomings and possible perspectives. Gynecological Surgery 2, no 2: 113–18. [Google Scholar]

- Moon-Grady AJ, Baschat A, Cass D, Choolani M, Copel JA, Crombleholme TM, Deprest J, Emery SP, Evans MI, Luks FI, Norton ME, Ryan G, Tsao K, Welch R and Harrison M. 2017. Fetal treatment 2017: The evolution of fetal therapy centers - a joint opinion from the international fetal medicine and surgical society (ifmss) and the north american fetal therapy network (naftnet). Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy 42, no 4: 241–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RK, Chan BC and Kilby MD. 2010. Review advances in fetal therapy The Obstatrician & Gynaecologist 12: 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ncphs. 1979. The belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research: The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, HHS. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L and Gold J. 2012. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and their parents following admission to the pediatric intensive care unit: A review. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 13, no 3: 338–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble R and Rodeck CH. 2008. Ethical considerations of fetal therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 22, no 1: 219–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuffield. 2006. Critical care decisions in fetal and neonatal medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Oberman M 1999. Mothers and doctors’ orders: Unmasking the doctor’s fiduciary role in maternal-fetal conflicts. 94 Nw. U. L. Rev. 451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oerlemans AJ, Rodrigues CH, Verkerk MA, Van Den Berg PP and Dekkers WJ. 2010. Ethical aspects of soft tissue engineering for congenital birth defects in children--what do experts in the field say? Tissue Eng Part B Rev 16, no 4: 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ones K, Yilmaz E, Cetinkaya B and Caglar N. 2005. Assessment of the quality of life of mothers of children with cerebral palsy (primary caregivers). Neurorehabil Neural Repair 19, no 3: 232–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopulos NA, Papadopoulos MA, Kovacs L, Zeilhofer HF, Henke J, Boettcher P and Biemer E. 2005. Foetal surgery and cleft lip and palate: Current status and new perspectives. British Journal of Plastic Surgery 58, no 5: 593–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendl G 1988. Symposium on ethics and morals related to antenatal treatment of pediatric neurosurgical disorders. Treatment of fetuses in utero--an opinion from central europe. Childs Nerv Syst 4, no 3: 158–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M 2014. Achievement of developmental milestones in emerging and young adults with and without pediatric chronic illness—a meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 39, no 6: 577–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quittner AL, Goldbeck L, Abbott J, Duff A, Lambrecht P, Solé A, Tibosch MM, Bergsten Brucefors A, Yüksel H, Catastini P, Blackwell L and Barker D. 2014. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis and parent caregivers: Results of the international depression epidemiological study across nine countries. Thorax 69, no 12: 1090–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rac. 2000. Prenatal gene tranfer: Scientific, medical, and ethical issues: A report of the recombinant DNA advisory committee. Hum Gene Ther 11, no 8: 1211–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston S and Leuthner S. 2011. Clinical report—maternal-fetal intervention and fetal care centers. In Pediatrics: American College Of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee On Ethics And American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi AS, Bahal R, Farrelly JS, Quijano E, Bianchi AH, Luks VL, Putman R, Lopez-Giraldez F, Coskun S, Song E, Liu Y, Hsieh WC, Ly DH, Stitelman DH, Glazer PM and Saltzman WM. 2018. In utero nanoparticle delivery for site-specific genome editing. Nat Commun 9, no 1: 2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TG Jr., Goulart BH, Squitieri L, Stallings SC, Halpern EF, Chabner BA, Gazelle GS, Finkelstein SN and Clark JW. 2004. Trends in the risks and benefits to patients with cancer participating in phase 1 clinical trials. JAMA 292, no 17: 2130–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]