In the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, early dashboards set up by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering tracked overall numbers of cases and deaths but provided no demographic breakdown of these statistics. Current data show wide racial disparities in the burden of COVID-19 in the USA, with Latino, Indigenous, and Black people disproportionately affected. Similar disparities are also evident in other nations with histories of structural racism. However, at the outset of the pandemic the focus of some research turned toward biological racial differences as an explanation for differences in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Early in the pandemic rumours that members of the African diaspora were immune to SARS-CoV-2 infection circulated in the global media. While public health messaging worked to combat these myths, some researchers began to investigate whether differences in blood type or gene expression could explain why racially minoritised groups were more or less likely to contract the virus. Historians and social scientists, such as Chelsea Carter and Ezelle Sanford III, and were some of the first to challenge these perspectives. Although misinformation regarding Black immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection was soon dispelled, the initial impulse in some quarters in early 2020 to attribute disparities to biological difference conferred by racial typology highlights the enduring power of race-thinking.

This narrative has a long history rooted in the emergence of western colonial projects and in the history of medicine. The historian Rana Hogarth has described the medical practice of searching for innate and unique differences between white and Black people as “medicalizing Blackness”. This preoccupation with supposedly innate biological difference has been used to justify slavery and oppression, as well as differential social, political, and health treatment.

While the categorisation of Africans as non-Christian was the primary justification for conquest and enslavement at the beginning of the slave trade, in the late 1700s, western colonial powers sought new justifications for stratifying populations by race. To justify the differential treatment of Black individuals and the violence that slavery entailed, European colonists turned to explanations of biological difference to present slavery as a “natural” phenomenon based on the fundamental inferiority of Black people. During this period, the work of naturalists was an important part of scientific enterprise and scientists sought to classify species into specific subtypes. At the same time, Carl Linnaeus, Johann Blumenbach, Georges-Louis Leclerc count de Buffon, and others sought to categorise humans into distinct racial groups. Various human taxonomies and different racial orders were put forth by naturalists in the 18th and 19th centuries and people of African descent were described as comprising an entirely separate race from white Europeans. These ideas gave rise to polygenist theories that claimed Black populations and white Europeans had arisen from different evolutionary paths. As populations were separated into races, scientists searched for differences between Black and white physiology in almost every bodily system. Enslaved Black individuals were probed to find physical differences in everything from skull size to lung capacity and each difference discovered was situated in a sociopolitical hierarchy that found Black individuals to be inferior in almost every instance.

The same science of biological racial difference that found Africans to be innately inferior also gave rise to the discovery of other “intrinsic” properties of Black populations. In the USA, prominent southern physicians such as Louisiana's Samuel A Cartwright conveniently found enslaved Africans to be less susceptible to heatstroke and malaria, making them suitable labourers for work on plantations regardless of the season. White physicians in Philadelphia during the late 18th century suggested that incidence of yellow fever was lower in Black people than white people and attributed this to innate biological resistance. As Hogarth has written, the supposition that Black people were immune to yellow fever had calamitous effects. The belief that Blackness conferred natural immunity was not only publicised by prominent physicians during the time but passed down in medical literature, preventing effective care for Black individuals with yellow fever. During the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, the city's free Black communities were called upon to care for the city's ill white population by prominent members of Philadelphia society, including Benjamin Rush, the abolitionist and signatory of the US Declaration of Independence. This claim was premised on the supposed difference between white and Black bodies and their susceptibility to disease and also reflected how Black lives were regarded as disposable to Philadelphian white populations.

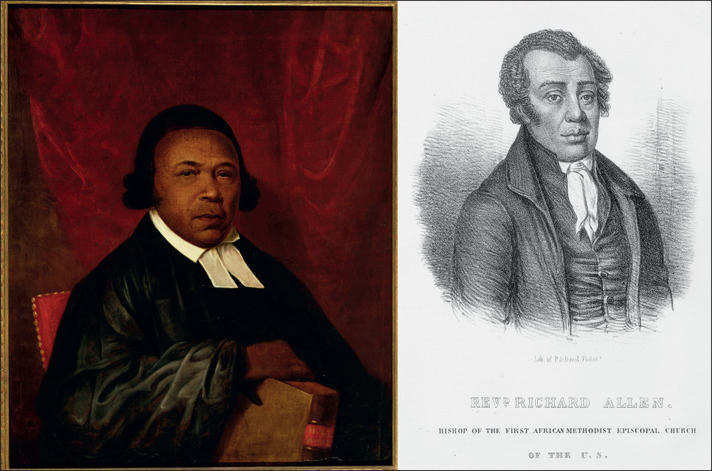

Richard Allen (right) and Absalom Jones (left) who led the organisation of the 1793 yellow fever relief effort in Philadelphia

© 2021 © Delaware Art Museum/Gift of Absalom Jones School /Bridgeman Images [Absalom Jones]Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images [Richard Allen]

The myth of Black immunity to disease and pain also manifested itself in other violent ways in southern states in the 19th century. As historian Deirdre Cooper Owens has documented in Medical Bondage, the belief that Black skin resisted pain was used as a justification by southern slave doctors such as James Marion Sims to subject enslaved women to repeated surgical experimentation without anaesthetic. Physicians at the time held firmly to the belief that there were vast differences between Black and white bodies; however, when these violent experiments resulted in a surgical method that could successfully close fistulas, this method was quickly applied to white women for their gynaecological ailments. As Cooper Owens has described, medical discourse constructed Black bodies as “medical superbodies” that were perceived as simultaneously biologically inferior while also serving as clinical material that could be subjected to experimentation to discover medical advances that served the health of the white population. Despite this apparent contradiction, the idea of distinct racial physiologies persisted in medical thought.

By the end of Reconstruction after the US Civil War, the notion of fundamental biological difference was so deeply integrated into medical thought that many diseases, such as cancer and sickle cell disease, were thought of in explicitly racial terms. This elevated racial difference as an explanatory factor for disease susceptibility. The result was an ignorance of the structural and social determinants of ill health and the provision of limited resources to ameliorate racial health disparities. For example, as Keith Wailoo has shown, during the 20th century as breast cancer awareness campaigns took a spotlight in public discourse, breast cancer itself was constructed as a “disease of civilization” that disproportionately affected white women. As public health officials took to media depictions of women bravely fighting breast cancer to combat the stigma surrounding the disease, the depicted patients were invariably upper-class white women. As cancer in general was perceived by medical authorities at the time as a disease of advanced western civilisation, African Americans were not viewed as at risk for breast cancer due to their assumed primitivism. Epidemiologists continually failed to track breast cancer morbidity and mortality by ethnicity. It was not until 1972 with a pathbreaking study from Howard University, a historically Black university, that Black women, long ignored in oncological studies, were reported as being as susceptible to breast cancer as white women. By this point, decades of public health resources and messaging had already gone toward setting up preventive care and health-care institutions in white areas.

Positing Black people as intrinsically immune to disease allowed political institutions to ignore health crises within Black communities that had been explicitly caused by racism and governmental neglect of Black health. Meanwhile, diseases that were thought to disproportionately affect Black populations received little attention from public health initiatives. For example, the scientific community labelled sickle cell disease as a “Black disease” for decades. Despite being the first disease for which a molecular mechanism was documented, research dedicated to finding a cure for the disease has been chronically underfunded in the USA. The racial construction of sickle cell disease had lasting implications for the kinds of public attention and funding it received.

Evidence has shown that there is more genetic variance within racially minoritised groups than between racial and ethnic groups, yet the desire to rebiologise difference as race specific has persisted. Presumed differences in Black physiology have been integrated into race-adjusted clinical algorithms that are used to make treatment decisions in specialties from gynaecology and obstetrics to pulmonology. The lasting legacy of this myth has obfuscated the much greater environmental health risk that Black individuals face as a consequence of structural racism, violence, and segregation. In the COVID-19 pandemic, research has shown that chronic underlying health conditions increase the risk of death from COVID-19 and are also disproportionately prevalent in populations that have suffered systemic violence and neglect. However, when susceptibility to disease is explained in terms of biological racial difference, scientists and policy makers alike are able to turn a blind eye to desperately needed policy fixes. The impacts of COVID-19 and global calls for reckonings with histories of systemic and structural racism have highlighted the ways in which both legacies of the past and continuing inequities produce negative health effects. As we continue to reckon with health disparities, it is important to address the biologisation of race as an assumption that both undergirds medical decision making and reinforces disparities. Calls for increased scrutiny of race-based medicine are a step toward equity; however, it is equally important to discuss the role of race-thinking in medical education so that clinical decision making is no longer guided by flawed, outdated notions of biological racial difference. Beyond this, a searching and profound disentangling of genetic disposition and meretricious concepts of scientific racism and the racial categories they birthed is required in fields that still retain and assert casual and causal meaning to racial difference.

Further reading

- Carter C, Sanford E., III The myth of Black immunity: racialized disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Black Perspectives, African American Intellectual History Society. April 3, 2020. https://www.aaihs.org/racializeddiseaseandpandemic/ (accessed Oct 5, 2021)

- Cooper Owens D. Medical bondage: race, gender, and the origins of American gynecology. University of Georgia Press; Athens, GA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Downs J. Sick from freedom: African-American illness and suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Oxford University Press; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq F, Mogayzel PJ, Lanzkron S, Haywood C, Strouse JJ. Comparison of US federal and foundation funding of research for sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis and factors associated with research productivity. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201737. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson GM. Racism: a short history. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth RA. Medicalizing blackness: making racial difference in the Atlantic world, 1780–1840. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill, NC: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4296–4301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516047113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobucci G. COVID-19: increased risk among ethnic minorities is largely due to poverty and social disparities, review finds. BMJ. 2020;371:m4099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendi IX. Why don’t we know who the coronavirus victims are? The Atlantic, April 1, 2020

- Latz CA, DeCarlo C, Boitano L, et al. Blood type and outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Ann Hematol. 2020;99:2113–2118. doi: 10.1007/s00277-020-04169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurencin CT, McClinton A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action to identify and address racial and ethnic disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7:398–402. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00756-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Häussinger L, Steinacker JM, Dinse-Lambracht A. Association between the dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic and ABO blood type distribution. Epidemiol Infect. 2021;149:e19. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhusoodanan J. How scientists are subtracting race from medical risk calculators. Science. 2021 doi: 10.1126/science.abl5611. published online July 22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reuters Staff False claim: African skin resists the coronavirus. Reuters, March 10, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-coronavirus-ethnicity/false-claim-african-skin-resists-the-coronavirus-idUSKBN20X27G (accessed Oct 5, 2021)

- CDC Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html (accessed Oct 5, 2021)

- Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight—reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:874–882. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2004740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wailoo K. Dying in the city of the blues: sickle cell anemia and the politics of race and health. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill, NC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wailoo K. How cancer crossed the color line. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2011. [Google Scholar]