Abstract

A 21-year-old woman suffered heatstroke and developed diarrhea while trekking across south Texas. The heatstroke was complicated by seizures, rhabdomyolysis, pneumonia, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. The patient’s stool and blood cultures grew Campylobacter jejuni. The patient subsequently developed paranasal and gastrointestinal zygomycosis and required surgical debridement and a prolonged course of amphotericin B. The zygomycete cultured was Rhizopus schipperae. This is only the second isolate of R. schipperae that has been described. R. schipperae is characterized by the production of clusters of up to 10 sporangiophores arising from simple but well-developed rhizoids. These asexual reproductive propagules are produced on Czapek Dox agar but are absent on routine mycology media, where only chlamydospores are observed. Despite multiorgan failure, bacteremia, and disseminated zygomycosis, the patient survived and had a good neurological outcome. Heatstroke has not been previously described as a risk factor for the development of disseminated zygomycosis.

Campylobacters are small, curved, motile, microaerophilic gram-negative rods. Campylobacter jejuni is the most common cause of bacterial diarrhea in the United States. However, C. jejuni bacteremia is uncommon; only about 0.4% of reported C. jejuni isolates originate from blood (1), and the bacteremia usually occurs in patients with underlying medical conditions or at the extremes of age (3). Likewise, disseminated infection by fungi of the order Mucorales, known as zygomycosis, is a rare infection and typically occurs in those immunocompromised by malignancy or renal disease (16). Here we report a case in which exertional heatstroke provided the setting for both disseminated zygomycosis and Campylobacter bacteremia. The zygomycete cultured was Rhizopus schipperae. This is only the second isolate of R. schipperae that has been described.

CASE REPORT

In June 1998, a 21-year-old Mexican woman crossed the United States border without documentation. She had a sore throat and cough prior to departure. She left San Luis Potosi, México, and rode a bus to Nuevo Laredo. With a group of men, she crossed the Rio Grande by boat and hiked into Dimmit County, Tex. In the morning, the woman had chills and diaphoresis. The immigrants drank from stock ponds and walked for several hours. The high temperature on this day was 105°F, and the woman became delirious and collapsed. She had convulsions and was taken to a local hospital. Initial vital signs were a rectal temperature of 107.1°F, a blood pressure of 71/44 mm Hg, a heart rate of 123 beats per minute, and a respiration rate of 30 breaths per minute. The patient was intubated and transferred to University Hospital in San Antonio, Tex. The assessment was exertional heatstroke with circulatory collapse, severe brain injury, shock liver, rhabdomyolysis, renal insufficiency, pancreatitis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Due to the probable exposure to enteric pathogens, levofloxacin was initiated on admission after blood and stool samples for cultures were obtained. The patient developed a lung infiltrate on day 3, and Enterobacter cloacae and a single colony of a Rhizopus species grew from tracheal aspirates. Blood and stool cultures grew C. jejuni. The antibiotic was changed to meropenem. On day 3, E. cloacae was also isolated from a blood culture.

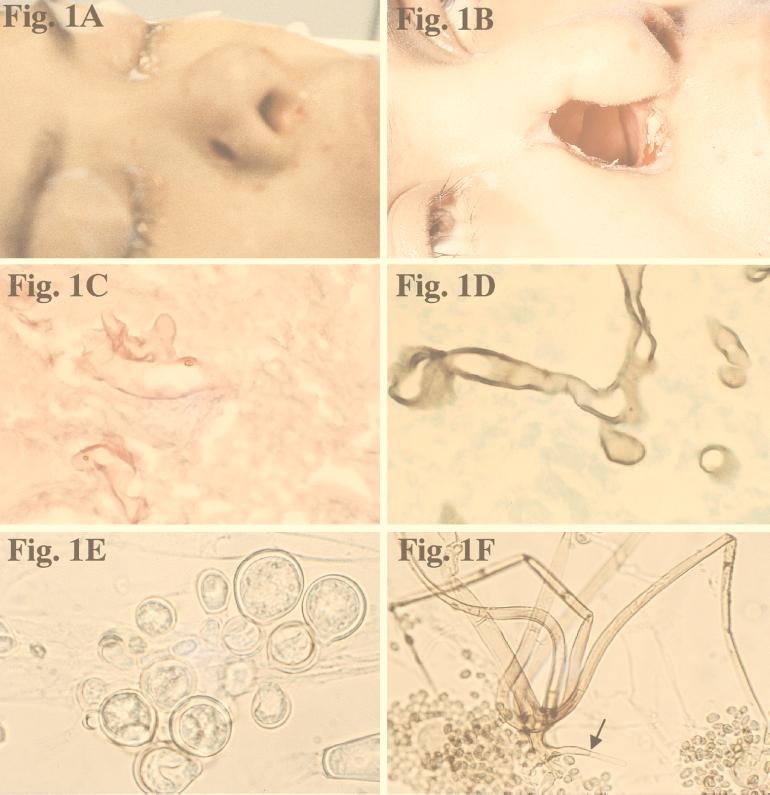

On day 9, a 5-mm dark eschar was noted on her right nasal ala (Fig. 1A). Resection of the ala, lower lateral cartilage, and a portion of the nasal septum was performed until bleeding tissue was obtained (Fig. 1B). The nasal tissue showed nonseptate fungal hyphae (Fig. 1C). Amphotericin B (AMB) was started at 1 mg/kg/day on day 9. On day 21, the patient passed bright red blood per rectum, and her hematocrit dropped to 10%. An angiogram revealed bleeding from the superior mesenteric artery. A resection of the terminal ileum and ascending colon was performed. An ulcerating lesion, 5.5 by 2.5 by 1.5 cm, was found on the mucosal surface at the ileocecal valve. Histopathological examination showed transmural necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and vascular invasion by nonseptate hyphae (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

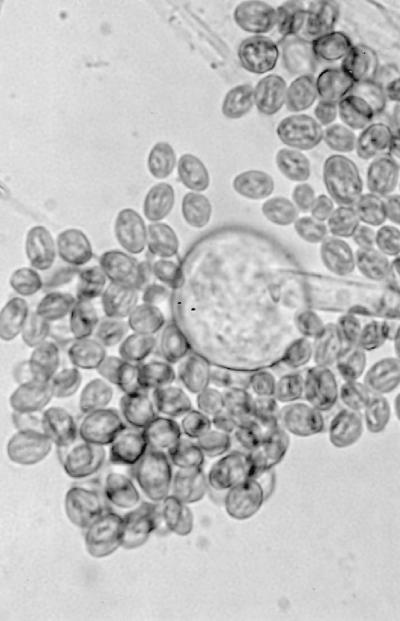

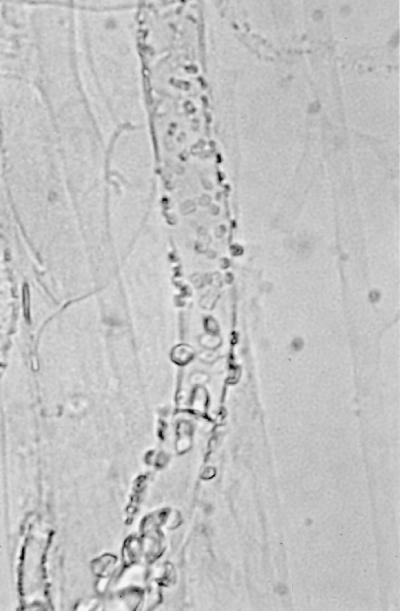

(A) Necrotic lesion on nasal ala prior to surgery. (B) Appearance of patient 1 month after surgery. (C) Branching, nonseptate hyphae of R. schipperae in nasal mucosa. Hematoxylin-eosin stain. Magnification, ×613. (D) Hyphae of R. schipperae in intestinal mucosa. Gomori methenamine-silver stain. Magnification ×613. (E) Thick- and thin-walled chlamydospores of R. schipperae on PDA. Magnification, ×613. Lactophenol cotton blue mount. (F) Cluster of sporangiophores of R. schipperae on CDA. The arrow shows a septate rhizoid. Magnification, ×213. Lactophenol cotton blue mount.

The patient received AMB at 1 mg/kg/day for a total of 40 days and AMB-lipid complex (ABLC) at 5 mg/kg/day intermittently for 12 days during periods of renal insufficiency. Two months after the heatstroke, she has had significant neurological recovery but suffers from dysarthria and ataxia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Histopathology.

Fragments of skin, soft tissue, and cartilage from the right nasal vault and segments of the terminal ileum and ascending colon were submitted for hematoxylin-eosin and Gomori methenamine-silver staining.

Mycology.

Samples from the tracheal aspirates, nasal tissue, and small intestine were initially incubated on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) at 25°C. Since the cultures did not sporulate, a small portion of SDA containing fungal growth was excised and incubated in a 10% yeast extract–water culture at 35°C for 10 days in an attempt to promote sporulation (26). Cultures remained sterile, producing only large, thick-walled, globose to somewhat irregularly shaped chlamydospores (Fig. 1E). The nasal isolate was plated on Mycosel agar (BBL), potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) (32), and SDA plates for temperature studies at 25, 30, 45, and 50°C. Subcultures of the nasal isolate (UH F 1746) were sent to the Fungal Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, for further characterization and designated UTHSC R-3053. There, the isolate was subcultured on Czapek Dox agar (CDA) (Remel) at 30°C, and temperature studies were repeated, but with the addition of 35°C testing.

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

The nasal isolate was tested to determine its susceptibilities to AMB, fluconazole (FLU), 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC), and itraconazole (ITRA). Tests were performed by previously described macrodilution methods (22, 33, 43). The minimum lethal concentrations (MLCs) were determined by plating 100-ml samples from the drug-free control tube, the MIC tube, and a tube containing each concentration above the MIC on an SDA plate incubated at 35°C. The MLC was defined as the lowest concentration of antifungal compound resulting in five or fewer colonies on the SDA plate (33).

RESULTS

Mycology.

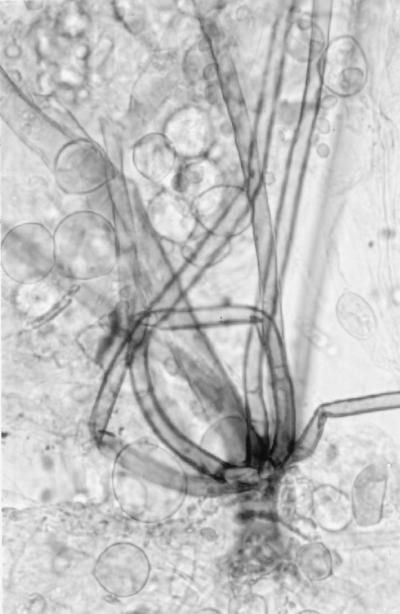

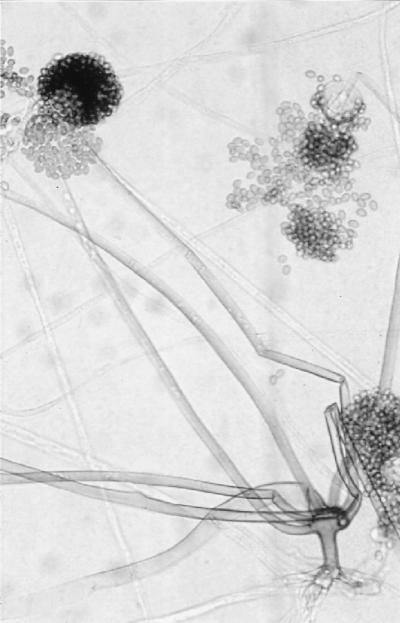

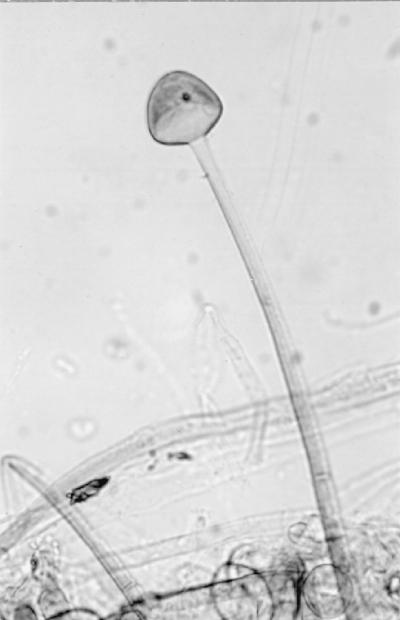

Initial cultures on SDA at 25°C produced white, sterile, floccose colonies after 4 days of incubation; the colonies became buff colored at day 6. Temperature studies revealed good growth at 25, 30, 35, and 45°C and no growth at 50°C. The isolate also failed to grow on media containing cycloheximide. Subcultured colonies at 25°C on PDA and SDA were white, floccose in the central portion, and thin and effuse near the periphery. Rapid growth resulting in numerous chlamydospores occurred on both media, but sporangia were lacking. Chlamydospores were thin or thick walled (0.5 to 1 or 3.9 μm wide), globose to subglobose, oval to irregularly shaped, and 10 to 40 μm in diameter (Fig. 1E). A culture in 10% yeast extract–water at 35°C was sterile after 10 days of incubation. Colonies on CDA at 30°C were white, thin, diffuse, and floccose, produced fewer numbers of chlamydospores than at 25°C, but promoted the production of the fruiting structures of R. schipperae Weitzman, McGough, Rinaldi, et Della-Latta (1996). These consisted of up to 10 (usually 4 to 8) sporangiophores arising from a cluster of rhizoids (Fig. 1F, 2, and 3). Mature sporangiophores were brown, being darker at the base, occasionally septate, 150 to 400 μm in length, and 3 to 13 μm in diameter. Sporangia were globose, greyish black, and up to 65 μm in diameter; columellae were subglobose and hyaline (Fig. 4). Sporangiospores were subglobose to oval and faintly striated in water, measuring 4.8 to 6.8 μm long by 3.9 to 5.8 μm wide (Fig. 5). Rhizoids were pale to darker brown, mostly simple (seldom branched), and occasionally septate (Fig. 1F). Some hyphal strands on all media were covered by crystals (Fig. 6). The case isolate was compared with the type isolate (UTHSC 94-538, ATCC 96514, CBS 138.95) obtained from a human lung in San Antonio, Tex., in 1996 (46). On the basis of the above features, the isolate was identified as R. schipperae.

FIG. 2.

Cluster of sporangiophores of R. schipperae on CDA. Magnification, ×306. Lactophenol cotton blue mount.

FIG. 3.

Rhizoids and sporangiospores of R. schipperae on CDA. Magnification, ×306. Lactophenol cotton blue mount.

FIG. 4.

Columella of R. schipperae on CDA. Magnification, ×213. Lactophenol cotton blue mount.

FIG. 5.

Columella and striated sporangiospores of R. schipperae on CDA. Magnification, ×613. Lactophenol cotton blue mount.

FIG. 6.

Crystals on hyphae of R. schipperae on PDA. Magnification, ×613. Lactophenol cotton blue mount.

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

The results of in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing are displayed in Table 1. Based upon drug concentrations normally achievable in patients receiving recommended dosages, the isolate appeared resistant to all antifungal agents tested (AMB, 5-FC, FLU, and ITRA). On the basis of an observed MIC of 4 μg/ml, R. schipperae appears to be somewhat more resistant to AMB than R. arrhizus, the most commonly isolated Rhizopus species, for which AMB MICs are typically 0.125 to 2.0 μg/ml (42). The MICs obtained for the azoles corroborated in vitro data for the type isolate; the MICs of FLU and ITRA were >64 and >8 μg/ml, respectively. The patterns of resistance to azoles observed for this fungus are similar to those seen for other Rhizopus species and zygomycetous genera (25).

TABLE 1.

In vitro susceptibility data for R. schipperae

| Antifungal agent | MIC (μg/ml) at:

|

MLC (μg/ml) at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| AMBa | 1 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| 5-FCb | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| FLUb | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| ITRAb | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 |

Tested in antibiotic medium 3 (Difco, Detroit, Mich.).

Tested in RPMI 1640 (American Biorganics, Inc., Niagara Falls, N.Y.).

DISCUSSION

Heatstroke.

Heatstroke occurs when exposure to high ambient temperatures produces hyperthermia and neurological dysfunction. Heatstroke produces damage in multiple organs, causing shock, DIC, renal failure, lung injury, lactic acidosis, and electrolyte abnormalities. The mortality rate in heatstroke is 10 to 50%, with 7 to 14% of the survivors suffering permanent neurological impairment (4).

Intestinal ischemia plays a central role in the pathophysiology of heatstroke (15). During exertion under heat stress, blood is shunted to exercising muscle and to the skin to dissipate heat. Blood flow is also maintained to the liver in order to access glucose and to remove lactate. However, the kidneys and intestines suffer a decrease in blood flow, with resultant ischemia and gut wall damage. If the ischemia is sufficiently prolonged, there is increased gut wall permeability, with leakage of endotoxin and bacteria into the circulation. Several cases of gram-negative sepsis have been described in exertional heatstroke (17).

Pathophysiology.

The following scenario attempts to explain why this woman experienced heatstroke while her male companions did not and why the uncommon conditions of C. jejuni bacteremia and zygomycosis arose in this patient. The patient’s home, San Luis Potosi, lies at an altitude of 1,877 m, and thus, despite its tropical latitude, has a moderate climate (44). Therefore, the patient was not acclimatized prior to departure, increasing the risk of heatstroke (15, 40). Half of her 12-h bus ride was in a non-air-conditioned vehicle; this situation may have also had a detrimental effect on her heat tolerance, because heat stress is cumulative (15).

Based on the patient’s symptoms of sore throat and cough, she may have had an antecedent upper-respiratory-tract viral infection. Viral infections may affect thermoregulation (18) and alter heat shock protein levels (15), thereby increasing susceptibility to heatstroke. The episode of diaphoresis experienced early in the journey indicates that a preexisting fever may have been another predisposing factor for heatstroke. Infection has previously been suggested as a risk factor for the development of heatstroke (19). In a study of 58 heatstroke survivors, 57% were noted to have had infections on admission (8).

C. jejuni infection can be food-borne or waterborne (12), and this organism has been found in cow feces (45); thus, the stock ponds from which this traveller drank were the probable source of exposure. C. jejuni is thermophilic, with an optimal growth temperature of 42°C, and it is also microaerophilic (12). Thus, it may have an increased rate of replication at higher body temperatures, especially in a situation of decreased oxygen tension in an ischemic bowel. As bowel ischemia progressed, bowel wall integrity was compromised, and the organism rapidly gained egress into the blood. Loss of intestinal mucosal integrity has been cited as a risk factor for C. jejuni bacteremia (30). The Enterobacter bacteremia that occurred only 3 days into the patient’s hospital course further suggests a loss of bowel wall integrity.

C. jejuni is typically susceptible to the nonspecific bactericidal activity of the complement in human serum; thus, C. jejuni bacteremia is uncommon (1). However, complement consumption has been reported in heatstroke, as a consequence of DIC (6, 11). Hypocomplementemia is therefore a risk factor for C. jejuni bacteremia (3). This patient also developed pancreatitis. Although multiorgan system failure is common in heatstroke, pancreatitis is uncommon (19). Pancreatitis has been reported to occur in 6% of patients hospitalized for Campylobacter enteritis (29). Thus, the Campylobacter infection may have been the inciting factor for pancreatitis.

The zygomycotic fungi are ubiquitous saprobes of the air and soil and cause spoilage of fruits and vegetables. Rhinocerebral and paranasal zygomycosis results from the inhalation of spores, the deposition of these spores on the nasal turbinates, germination on the nasal mucosa, and subsequent penetration by the hyphae either directly or via the vasculature into the sinuses, orbits, and brain (20, 41). Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is the most common risk factor cited for paranasal and rhinocerebral zygomycosis (28, 41). Frequent blood gas analyses indicated that this patient had metabolic acidosis with compensatory respiratory alkalosis, as observed previously in heatstroke (4). She also had mild hyperglycemia; the highest blood glucose level recorded prior to the paranasal zygomycosis was 205 mg/dl. Nevertheless, these abnormalities are mild compared to the extreme metabolic derangements that occur in DKA. Thus, other factors may have contributed to the development of paranasal zygomycosis. Degeneration of the nasal mucosa, with capillary proliferation, occurs in heatstroke (2). Because the zygomycetes are angioinvasive (41), morphological changes of the nasal mucosa may have facilitated the spread of the fungus. Complement depletion was probably not important in the pathogenesis of the zygomycosis, because complement does not have a significant inhibitory effect on zygomycetes (10).

Gastrointestinal zygomycosis is rare (23, 39, 47); only five cases were observed in a series of 32 patients with zygomycosis over 20 years (20). Conditions that predispose to gastrointestinal zygomycosis are malnutrition, dehydration, DKA, aplastic anemia, leukemia, and gastroenteritis (21). In animal models of zygomycosis, damage to the gastrointestinal mucosa leads to fungal invasion (7). There is one previous example of Enterobacter bacteremia preceding gastrointestinal zygomycosis (31). There are two other factors that may have contributed to the development of disseminated zygomycosis: uremia, which produces defects in neutrophil and macrophage function (47), and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, which alters the usual bowel flora (16, 21, 23).

In disseminated zygomycosis with gastrointestinal involvement, the gastrointestinal tract is usually the primary site, with disease spreading hematogenously from this focus (16); however, there was no evidence for this process occurring in this case. For this patient, we propose that the nose and sinuses were the primary site of involvement, as indicated by the Rhizopus found in the sputum culture early in the hospital course and the observation of the paranasal process about 10 days before the recognition of the gastrointestinal disease. Apparently, postnasal secretions containing fungi were swallowed, and these organisms invaded the colonic mucosa previously damaged by heatstroke and C. jejuni.

In vitro antifungal susceptibility.

Currently, AMB is the only antifungal agent with clinical utility in the treatment of zygomycosis (25). Although the in vitro data for AMB suggested resistance, the incidence of infections with mold pathogens is sufficiently low that strict correlation of antifungal MICs with clinical results of antifungal treatment has not yet been established (24).

With early diagnosis, metabolic stabilization, aggressive debridement, and administration of AMB, survival for zygomycosis restricted to a single site has increased to 73 to 80% (27, 41). However, disseminated zygomycosis, defined as infection occurring in two or more noncontiguous organ systems, has a grim prognosis. In a series of 185 cases reviewed by Ingram et al. (16), only five patients survived. This patient received prolonged therapy with conventional AMB at 1 mg/kg/day before susceptibility results were available. The patient also received ABLC at 5 mg/kg/day for 12 days; such lipid preparations permit higher doses to be tolerated (14). Administration of ABLC, prolonged treatment with conventional AMB, aggressive surgical debridement, and resolution of metabolic abnormalities all provided sufficient conditions for eradication of the fungus.

Taxonomy and identifying features.

R. schipperae was first described in 1996 after the organism was obtained from bronchial washings and lung specimens from a patient with multiple myeloma in San Antonio, Tex. (46). This case represents only the second isolate of R. schipperae ever described. However, we suspect that the organism may be more common but is not often identified due to the requirement of CDA for sporulation. The organism belongs to the R. microsporus complex, being closely related morphologically to R. microsporus var. microsporus Schipper (1984) Schipper et Sampson (1994) and sharing characteristics with R. caespitosus Schipper et Sampson (1994) in the same complex (35–37) and with Amylomyces rouxii Ellis, Rhodes, et Hasseltine (1976) (9). Characteristics which differentiate these species are displayed in Table 2. Distinguishing features for R. schipperae include its ivory to buff color on PDA, the production of numerous intercalary and terminal chlamydospores on a variety of media, clusters of up to 10 short sporangiophores arising from simple, well-developed rhizoids, the limited range of media for the development of sporangia (especially CDA), and striated sporangiospores. The species is named in honor of M. A. A. Schipper for her work with the Mucorales.

TABLE 2.

Features of R. schipperae and similar speciesa

| Organism | Colony color on PDA | Chlamydospores | Sporangiophores

|

Description of sporangiospores in water (length μm) | Sporangia

|

Rhizoids | Zygospores | Growth at the following temp (°C)b

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grouping | Length | Formation | Morphology | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | ||||||

| Rhizopus schipperae | Ivory to buff | Numerous on all media | Clusters, up to 10 | Short, up to 460 μm | Striated, angular, oval (up to 6.8) | On special media; best on CDA | Normal, globose | Simple, abundant, and well developed | None with positive and negative mating strains of R. microsporus var. microsporus | + | + | + | − |

| Rhizopus microsporus var. microsporus | Pale brownish gray | Varying with isolate, rare to numerous | Usually single, up to 3 | Short, up to 400 μm | Striated, angular (up to 6.5) | On routine media | Normal, globose | Simple | Easily obtained, present in crosses between positive and negative mating strains of R. microsporus var. microsporus | + | + | + | − |

| Rhizopus caespitosus | White to gray | In aerial mycelium | Clusters, up to 9 | Short, 200– 500 μm | Smooth, angular (up to 8) | On routine media | Long, ellipsoidal | Simple | Unknown, none with positive and negative mating strains of R. microsporus var. microsporus | + | + | + | + |

| Amylomyces rouxii (Rhizopus chlamydosporus) | White to brownish gray | Numerous on all media | Usually single | Long, up to 2.5 mm | Abortive, spore-like bodies | Fair on CDA but abortive | Abortive, globose to oval | Rare | Unknown | + | + | − | − |

Conclusions.

This case exemplifies the severe pathophysiological disturbances that occur in heatstroke with accompanying infectious complications. Heatstroke may alter immune status and predispose to infection by a number of mechanisms: increased translocation of organisms across an ischemic bowel wall, acidosis, complement depletion secondary to DIC, and altered lymphocyte function (5, 8, 11, 13). Heatstroke has previously been recognized as a risk factor for gram-negative bacteremia (11, 17). However, this is the first report of heatstroke as a setting for disseminated zygomycosis. There is one previous example of disseminated infection with the fungus Fusarium oxysporum in a patient with heatstroke (40).

This case also illustrates the larger problem of severe heatstroke in undocumented Méxican immigrants. During the 1998 Texas heat wave, from 1 May to 2 August, at least 47 undocumented immigrants died from heatstroke (34). This patient survived six-organ dysfunction (lungs, brain, coagulation system, liver, intestines, and pancreas) and four invasive infections and achieved a good neurological outcome, but only with intensive application of health-care resources.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allos B M, Blaser M J. Campylobacter jejuni and the expanding spectrum of related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1092–1101. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anim J T, Baraka M E, Al-Gamdi S, Sohaibani M O. Morphological alterations in the nasal mucosa in heat stroke. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1988;8:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser M J. Extraintestinal Campylobacter infections. West J Med. 1986;144:353–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchama A. Heatstroke: a new look at an ancient disease. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:623–625. doi: 10.1007/BF01711537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchama A, el Hussein K, Adra C, Rezeig M, al Shail E, al Sedairy S. Distribution of peripheral blood leukocytes in acute heatstroke. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:405–409. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branson H E, Wyatt L L, Schmer G. Complement consumption in acute disseminated intravascular coagulation without antecedent immunopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;66:967–975. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/66.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chihaya Y, Matsukawa K, Mizushima S, Matsui Y. Ruminant forestomach and abomasal mucormycosis under rumen acidosis. Vet Pathol. 1988;25:119–123. doi: 10.1177/030098588802500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dematte J E, O’Mara K, Buescher J, Whitney C G, Forsythe S, McNamee T, Adiga R B, Ndukwu I M. Near-fatal heat stroke during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:173–182. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis J J, Rhodes L J, Hasseltine C W. The genus Amylomyces. Mycologia. 1976;68:131–143. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eng R H K, Corrado M, Chin E. Susceptibility of zygomycetes to human serum. Sabouradia. 1981;19:111–115. doi: 10.1080/00362178185380171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graber C D, Reinhold R B, Berman J G, Harley R A, Hennigar G R. Fatal heat stroke. Circulating endotoxin and gram-negative sepsis and complications. JAMA. 1971;216:1195–1196. doi: 10.1001/jama.216.7.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths P L, Park R W A. Campylobacters associated with human diarrhoeal disease. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;69:281–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammami M M, Bouchama A, Shail E, Aboul-Enein H Y, Al-Sedairy S. Lymphocyte subsets and adhesion molecules expression in heat stroke and heat stress. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1615–1621. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.5.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiemenz J W, Walsh T J. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B: recent progress and future directions. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(Suppl. 2):S133–S144. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.supplement_2.s133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubbard R W, Gaffin S L, Squire D L. Heat-related illness. In: Auerbach P S, editor. Wilderness medicine. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: The C. V. Mosby Co.; 1995. pp. 167–212. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingram C W, Sennesh J, Cooper J N, Perfect J R. Disseminated zygomycosis: report of four cases and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:741–754. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.5.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kay M A, McCabe E D B. Escherichia coli sepsis and prolonged hypophosphatemia following exertional heat stroke. Pediatrics. 1990;86:307–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keren G, Epstein Y, Magazanik A. Temporary heat intolerance in a heatstroke patient. Aviation Space Environ Med. 1981;52:116–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knochel J P. Heat stroke and related disorders. Dis Mon. 1989;35:306–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchevsky A M, Bottone E J, Geller S A, Giger D K. The changing spectrum of disease, etiology, and diagnosis of mucormycosis. Hum Pathol. 1980;11:457–464. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(80)80054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mooney J E, Wanger A. Mucormycosis of the gastrointestinal tract in children: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:872–876. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199310000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M2-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neame P, Rayner D. Mucormycosis: a report on twenty-two cases. Arch Pathol. 1960;70:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odds F C, Van Gerven F, Espinel-Ingroff A, Barlett M S, Ghannom M A, Lancaster M V, Pfaller M A, Rex J H, Rinaldi M G, Walsh T J. Evaluation of possible correlations between antifungal susceptibilities of filamentous fungi in vitro and antifungal treatment outcomes in animal infection models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:282–288. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otcenasék M, Buchta V. In vitro susceptibility to 9 antifungal agents of 14 strains of Zygomycetes isolated from clinical specimens. Mycopathologia. 1994;128:135–137. doi: 10.1007/BF01138473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padhye A A, Ajello L. A simple method of inducing sporulation by Apophysomyces elegans and Saksenaea vasiformis. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1861–1863. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1861-1863.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parfey N A. Improved diagnosis and prognosis of mucormycosis. A clinicopathologic study of 33 cases. Medicine. 1986;65:113–123. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson K L, Wang M, Canalis R F, Abemayor E. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: evolution of the disease and treatment options. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:855–862. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199707000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitkanen T, Ponka A, Peterson T, Kosunen T. Campylobacter enteritis in 188 hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:215–219. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1983.00350020033007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed R P, Friedland I R, Wegerhoff F O, Khoosal M. Campylobacter bacteremia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:345–348. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199604000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reimund E, Ramos A. Disseminated neonatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis: a case report and review. Pediatr Pathol. 1994;14:385–389. doi: 10.3109/15513819409024268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rinaldi M G. Use of potato flakes agar in clinical mycology. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1159–1160. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1159-1160.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rinaldi M G, Howell A W. Antifungal antimicrobics: laboratory evaluation. In: Wentworth B, editor. Diagnostic procedures for mycotic and parasitic infections. 7th ed. Washington, D.C: American Public Health Association; 1988. pp. 325–356. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schillert D. Perilous journey: immigrants say dangers are worth chance for a better life. San-Antonio Express News. 1998;August:2. :1A, 14A. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schipper M A A. A revision of the genus Rhizopus. I. The Rh. stolonifer group and Rh. oryzae. Stud Mycol Baarn. 1984;25:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schipper M A A, Samson R A. Miscellaneous notes on Mucoraceae. Mycotaxon. 1994;50:475–491. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schipper M A A, Stalpers J A. A revision of the genus Rhizopus. III. The Rhizopus microsporus group. Stud Mycol Baarn. 1984;25:19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrier R W, Hano J, Keller H I, Finkel R M, Gilliland P F, Cirksena W J, Teschan P E. Renal, metabolic, and circulatory responses associated with heat stress and exercise. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73:213–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-73-2-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh N, Gayowski T, Singh J, Vu V L. Invasive gastrointestinal zygomycosis in a liver transplant recipient: case report and review of zygomycosis in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:617–620. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sturm A W, Grave W, Kwee W S. Disseminated Fusarium oxysporum infection in patient with heatstroke. Lancet. 1989;i:968. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugar A M. Mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(Suppl. 1):S126–S129. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.supplement_1.s126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutton D A, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. Guide to clinically significant fungi. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutton D A, Slifkin M, Yakulis R, Rinaldi M G. U.S. case report of cerebral phaeohyphomycosis caused by Ramichloridium obovoideum (R. mackenziei): criteria for identification, therapy, and review of other known dematiaceous neurotropic taxa. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:708–715. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.708-715.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Bleyleben K, von Bleyleben A. Baedeker Mexico. New York, N.Y: Macmillan Travel; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waterman S C, Park R W A, Bramley A J. A search for the source of Campylobacter jejuni in milk. J Hyg Camb. 1984;92:333–337. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400064871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weitzman I, McGough D A, Rinaldi M G, Della-Latta P. Rhizopus schipperae, sp. nov., a new agent of zygomycosis. Mycotaxon. 1996;59:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winkler S, Susani S, Willinger B, Apsner R, Rosenkranz A R, Potzi R, Berlakovich G A, Pohanka E. Gastric mucormycosis due to Rhizopus oryzae in a renal transplant recipient. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2585–2587. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2585-2587.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]