Abstract

Background:

Participation in clinical trials is essential to bringing novel and innovative cancer treatments to the bedside but trials that specifically enroll Veterans are relatively few. Given the inherent differences between Veterans and the general U.S. population, we sought to investigate awareness of and attitudes toward clinical trials among Veterans diagnosed with cancer at a large, urban Veterans Administration Medical Center in Bronx, New York.

Methods:

The survey was administered in 2018-2019. Questions assessed sociodemographic characteristics, health literacy, and general attitudes about clinical trials. Based on key informant interviews, we also inquired about military-specific attitudes. Univariable analyses were conducted to evaluate differences in attitudes by age (<65 vs. ≥65 years) and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black vs. other).

Results:

Of 115 Veterans approached, 67 (58.3%) completed the survey. Approximately 95% of participants were male, 59.7% were ≥65 years old, and 41.8% were non-Hispanic black. Only 58.2% reported knowing what a clinical trial is but 78.5% of Veterans stated that they trust doctors who do medical research and 87.5% reported they would strongly consider joining a trial if their VA primary care physician recommended it. Many stated that they would be part of a clinical trial if it would help fellow Veterans in the future (93.8%) and would help scientists learn how to treat other Veterans with the same disease (93.8%). Among non-Hispanic black participants, 62.5% agreed that the government has a history of using Veterans in experiments without their knowledge compared to 34.2% of Veterans of other race/ethnicity (p = 0.03).

Conclusions:

Clearly Veterans in our study were amenable to joining clinical trials. While many are aware of past misconduct in the treatment of military personnel in research, overall attitudes toward clinical trials were favorable and were especially positive when the possibility of improving cancer care for fellow Veterans was considered. In approaching Veterans regarding participation in a clinical trial we recommend education aligned with the literacy level of the Veteran, involvement of the VA primary care provider in clinical trial decisions, and awareness of a Veteran’s altruism to help others.

Keywords: Clinical trials, Veterans, Military personnel, Cancer, Attitudes, Survey

INTRODUCTION

Clinical trials are essential to the generation of scientific evidence to inform clinical oncology practice and improve cancer outcomes. Critically important to the financial, ethical, and scientific success of cancer clinical trials is the voluntary participation of patients. A significant number of trials, however, fail to reach completion, close early or are terminated because of the inability to meet minimum accrual goals. Closure or termination due to poor accrual rates has been estimated at 8.5% for immune checkpoint inhibitor trials to as high as 37.9% for phase III trials [1-4].

In the United States, enrollment of eligible patients to cancer clinical trials is reported to be about 8% in the community [5] and 14.0% to 15.9% at academic centers [5-7]. (Table 1) Provider barriers to clinical trial enrollment can be categorized as systems-related, clinical, and attitudinal [5]. Systems level provider barriers typically include factors such as lack of awareness of trials and insufficient system support [8], whereas clinical factors involve the potential impact of restrictive eligibility criteria and competing comorbidities on trial toxicities. Finally, provider attitudes about the patient’s ability to comply with complex study protocols, their own personal values and beliefs about clinical trials [8, 9], and misperceptions related to the patient’s willingness to participate [10] all impact trial enrollment.

Table 1.

Barriers to enrollment in clinical trials

| Provider barriers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| System-related barriers | |||

| Unger, 20195 | Systematic review and meta-analysis including 13 studies (9 in academic and 4 in community settings) with 8883 patients |

|

|

| |||

| Hamel, 20168 |

|

|

|

| Provider attitudes | |||

| Hamel, 20168 |

|

|

|

| Ibraheem, 20179 |

|

||

| Hillyer, 202010 |

|

||

| Patient Level Barriers | |||

| Mills, 200619 |

|

|

|

| Ford, 200815 |

|

|

|

| Meropol, 200718 |

|

|

|

| Unger, 201920 |

|

|

|

| Hamel, 20168 |

|

|

|

| Unger, 201311 |

|

|

|

| Gross, 200512 |

|

|

|

| Avin, 201713 |

|

|

|

| Williams, 201814 |

|

|

|

| Byrne, 201416 |

|

|

|

| BeLue, 200621 |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

Since patients ultimately decide whether or not to participate in clinical trials, much research has been devoted to understanding patient-level barriers. Low socioeconomic status of patients limits access to both health care and to high-volume cancer centers where most clinical trials are conducted [11-13]. Financial barriers such as inadequate health insurance coverage [8], additional expenses associated with participation [8, 14], and logistic factors and family issues including transportation, childcare [14-17] and required time off from work for research visits and procedures [9] disproportionately impact the willingness of many patients to enroll in a clinical trial. Many patients are also faced with language and cultural barriers [16] in the medical system, lack of awareness or knowledge about clinical trials [8, 14] and fears surrounding study design (e.g., randomization, placebo, adverse effects) [16, 18, 19]. Additionally, strict trial eligibility criteria [16, 20] more often excludes minority patients from clinical trial consideration who are more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to live with chronic comorbidities.

Patient attitudinal and cognitive barriers also impact clinical trial enrollment. Past cases in which the rights of participants were abused still linger in the minds of many and contribute to feelings of mistrust of the medical system, particularly amongst historically targeted groups such as the African American population [9, 14, 15]. Attitudes that research is not beneficial to the patient, and negative beliefs about the purpose and intention of research (e.g., being treated like a guinea pig) [8, 21] are often reported by patients as barriers to trial enrollment.

Clinical trials that enroll specifically military service members and Veterans are relatively few, and most studies do not track whether a trial participant is a Veteran or not. In 2016, a review of the 2,475 U.S, clinical trials registered in clinicaltrials.gov between 2005 and 2014 found that U.S. service members participated in a meaningful proportion in 512 studies (20.7%). That is, enrollment of military service members met a threshold of at least 30, or, in larger trials a minimum of 10% in studies comprising both military and non-military participants. Of these 512 trials, only 120 were open to military participants exclusively [22] and none focused on patients with cancer.

Veterans are a special population with characteristics that differ from those of the general U.S. population. The majority of Veterans today are predominantly male who tend to have higher levels of education and income than the average American [23]. Further, Veterans who use the Veteran Administration (VA) medical system are considered to be a highly selected group within this special population. Users of VA medical benefits include individuals who were honorably discharged and priority care is provided for Veterans with service-related disability, who were prisoners of war or who meet specific financial criteria [23]. A study among 3,152 Veterans enrolled in the National Health and Resilience of Veterans Study in 2011, found that individuals seeking healthcare at VA medical facilities reported greater prevalence of psychopathology, more suicidal ideation, and higher levels of enduring trauma – further distinguishing Veterans from the general U.S. population [24].

The overwhelming majority of knowledge related to clinical trial enrollment and barriers to trial participation has been learned from civilian populations. Little is known about differences between the general population and military personnel with regard to willingness to participate in clinical trials and barriers that are specific to these individuals (Table 2). Cook and Doorenbos reported that among clinical trials seeking to enroll large numbers of military participants (25% or more of all enrollees), 12% were withdrawn, terminated, or suspended due to low rates of enrollment or funding issues [25]. No differences were identified, however, in the difficulty to recruit and enroll service members vs. other research participants. Another study investigated the impact of financial reimbursement on trial retention among 666 active duty service members from six U.S. military treatment facilities and concluded that reimbursement for trial participation was modestly associated with retention rates [26]. Conversely, Campbell et al. reported that among Veterans, there was a strong aspect of ‘paying back’ people who treated them as important while financial compensation was less important [27]. This altruism toward fellow Veterans was also observed in a qualitative evaluation of motivations to participate in clinical trials among military Veterans in five U.S. cities where adequate compensation, desire to help fellow Veterans, and the significance and relevance of the research topic all played important roles in the decision to participate in a clinical trial. Additional factors such as trust, respect, and transparent communication were also highly ranked conditions of trial participation among Veterans [28].

Table 2 –

Issues in Participating in Clinical Trials Amongst Veterans and Military Personnel

| Novak, 201926 |

|

|

|

| Campbell, 200727 |

|

|

|

| Littman, 201828 |

|

|

|

| Hillyer, 2021current study |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: OEF, Operation Enduring Freedom; OIF, Operation Iraqi Freedom

Given the inherent differences between military service members and Veterans and the general U.S. population, we hypothesized that attitudes toward clinical trials that underly receptivity and motivation to participate in trials would similarly differ from barriers commonly reported among civilian Americans. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate attitudes about clinical trials and clinical trial participation among a group of military Veterans diagnosed with cancer at a large, urban Veterans Administration Medical Center in Bronx, New York.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Development of the patient survey

We conducted in-depth interviews among three key informants including a psychiatrist, an infectious disease physician, and a social worker; all had prior experience implementing clinical trials in their respective clinical areas among Veteran patients at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Bronx, New York. Several important themes emerged from these discussions including the importance of building patient trust and leveraging existing trusted relationships to encourage clinical trial participation (e.g., involving the primary care physician in discussions surrounding clinical trial participation); embedding clinical trials into the culture of the clinical area and eliciting staff buy-in; emphasizing the importance of research and appealing to altruism toward other Veterans; and offering compensation for trial participation to cover transportation and other expenses. Barriers identified by the key informants also encompassed costs associated with trial participation (e.g., time off from work and transportation costs), lack of rapport with the research investigative team, and general attitudes of suspicion and distrust regarding clinical research. These concepts were then integrated into the design of the quantitative survey that was administered to Veterans.

Patient survey

All procedures were conducted at the James J. Peters Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Bronx VA), the oldest VA facility in New York City located in the borough of the Bronx. Using a convenience sampling strategy, we approached adult patients with cancer in the waiting room of a large VA oncology clinic. Participants included adult patients, 18 years of age or older, who were diagnosed with cancer, were under the care of a VA medical oncologist, and were not currently enrolled in a clinical trial. Excluded were patients not yet diagnosed with cancer. With the permission of the attending physician, an oncology research nurse or a clinical trials navigator approached potential participants, introduced the study, and determined participation interest. Written informed consent from interested patients was obtained and the survey was administered in English in a private area in the clinic. Responses were recorded in Qualtrics and uploaded to a dedicated VA server via secure internet lines.

From each participant we collected clinical information including type of cancer and year diagnosed. Sociodemographic information included sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black vs. other race/ethnicity), age (<65 years vs. ≥65 years), highest educational level (high school, some college/trade/technical school, and college or graduate degree), and marital status. We also evaluated social support using the eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey that encompasses tangible support and emotional support [29] and quality of life using the FACT-G7 capturing physical well-being [30]. Using a brief screening measure, we assessed health literacy [31]. Participants were asked if they possessed a cell/mobile phone and if they used that phone to connect to the internet. We also inquired about health seeking behavior on the internet.

Knowledge of clinical trials was evaluated by asking a single question “Do you know what a clinical trial is?” with binary responses (‘Yes’ vs. ‘No’). To assess attitudes toward clinical trials, we asked participants to rate feelings toward clinical trials as ‘very negative’ through ‘very positive.’ Willingness to participate in a clinical trial today if asked was assessed and responses included “Yes, I definitely would,” “I might, not sure, it depends,” and “No, I definitely would not.” We further asked participants to indicate level of agreement (‘strongly agree’ through ‘strongly disagree’) with a series of questions about clinical trials that were positive or negative in nature [32]. Based on the key informant interviews, we constructed eight clinical trial attitude questions specific to Veterans that queried participants about the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each statement (for example, “Being part of a clinical trial that could help my fellow Veterans in the future is important to me”).

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses including frequency distributions for categorical variables and mean, standard deviation, median, and range for continuous variables were computed. Univariable analyses using the Chi square test and Fisher’s Exact test were performed to assess response differences by race ethnicity (non-Hispanic black vs. other race and ethnicity) for categorical type questions and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. The social support measure was scored according to published instructions [33] which generated a value on a scale of 0-100. The quality of life measure was scored by summing response values and calculating the mean score, ranging from 0-28 [34]. For attitude measures, Likert scale responses were recoded as “agree” vs. “disagree.”. Differences in characteristics and attitudes toward clinical trials was examined by age and race/ethnicity. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (version 27) [35]. All procedures were approved by the Bronx VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Of 115 Veterans approached, 67 (58.3%) completed the survey. The majority of participants were male (95.5%), had some college education (69.2%) and were unmarried (63.6%) (Table 3). For social support, the mean score was slightly above the mid-point of the scale at 57.3 [SD 28.7] (scale range 0.0 to 100.0) and the mean score for quality of life was 19.2 [SD 3.3] (scale range 9-27). When asked about comprehension of information from their doctor, 62.2% reported being able to understand information ‘all the time’; however, 41.8% stated that they needed some type of assistance with written information or instructions from the doctor or pharmacy. Approximately two-thirds of participants reported that they used the internet (64.2%) and, of those, 65% stated that they use the internet to seek health information. When stratified by age (<65 years vs. ≥65 years), older participants had a lower quality of life score (18.3 [SD 3.2] vs. 20.4 [3.2], p = 0.008) and more often reported needing help with instructions and information from the doctor or pharmacy “all the time” (12.5% vs. 0.0%, p 0.04) than their younger counterparts. There were no statistically significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics by race/ethnicity.

Table 3:

Sociodemographic characteristics of Veterans diagnosed with cancer at the Bronx Veterans Hospital (n = 67) by age and race/ethnicity

| SCREENING INFORMATION | Age | Race | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 67) |

<65 (n = 27, 40.3%) |

≥65 (n = 40, 59.7%) |

p- value |

Non-Hispanic African American (n = 28,41.8%) |

Other race and ethnicity (n = 39, 58.2%) |

p- value |

|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 64 (95.5) | 24 (88.9) | 40 (100.0) | 0.06 | 25 (89.3) | 39 (100.0) | 0.07 |

| Female | 3 (4.5) | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 28 (41.8) | 15 (55.6) | 13 (32.5) | 0.06 | -- | -- | -- |

| Other race/ethnicity | 39 (58.2) | 12 (44.4) | 27 (67.5) | -- | -- | ||

| Age | |||||||

| <65 years | 27 (40.0) | -- | -- | -- | 15 (53.6) | 12 (30.8) | 0.06 |

| ≥65 years | 40 (59.7) | -- | -- | 13 (46.4) | 27 (69.2) | ||

| Education | |||||||

| ≤High school | 20 (30.8) | 6 (23.1) | 14 (35.9) | 0.13 | 7 (25.9) | 13 (34.2) | 0.71 |

| Some college, trade or technical school | 30 (44.8) | 16 (61.5) | 14 (35.9) | 14 (51.9) | 16 (42.1) | ||

| College or graduate degree | 15 (24.4) | 4 (15.4) | 11 (28.2) | 6 (22.2) | 9 (23.7) | ||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married/living as married | 24 (36.4) | 10 (37.0) | 14 (35.9) | 0.93 | 18 (64.3) | 24 (63.2) | 0.93 |

| Not married | 42 (63.6) | 17 (63.0) | 25 (64.1) | 10 (35.7) | 14 (36.8) | ||

| SOCIAL SUPPORT | |||||||

| Mean [SD] | 57.3 [28.7] | 62.1 [23.9] | 53.9 [31.6] | 0.26 | 52.9 [28.2] | 60.4 [29.0] | 0.94 |

| Actual range | 0.0-100.0 | 0.0-100.0 | 0.0-100.0 | 0.0-100.0 | 0.0-100.0 | ||

| QUALITY OF LIFE | |||||||

| Mean [SD] | 19.2 [3.3] | 20.4 [3.2] | 18.3 [3.2] | 0.008 | 19.1 [3.8] | 19.2 [3.0] | 0.45 |

| Actual range | 9-27 | 16-27 | 9-24 | 9-26 | 13-27 | ||

| HEALTH LITERACY | |||||||

| How often do you understand information from doctor | |||||||

| Never | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.79 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.15 |

| Almost never | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Sometimes | 26 (38.8) | 11 (40.7) | 15 (37.5) | 8 (28.6) | 18 (46.2) | ||

| All the time | 41 (61.2) | 16 (59.3) | 25 (62.5) | 20 (71.4) | 21 (53.8) | ||

| How often do you need help with instructions and information from the doctor or pharmacy | |||||||

| Never | 39 (58.2) | 20 (74.1) | 19 (47.5) | 0.04 | 18 (64.3) | 21 (53.8) | 0.6 |

| Almost never0.60 | 11 (16.4) | 3 (11.1) | 8 (20.0) | 5 (17.9) | 6 (15.4) | ||

| Sometimes | 12 (17.9) | 4 (14.8) | 8 (20.0) | 3 (10.7) | 9 (23.1) | ||

| All the time | 5 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (7.1) | 3 (7.7) | ||

| HEALTH INFORMATION SEEKING | |||||||

| Have a cell/mobile phone | 61 (91.0) | 26 (96.3) | 35 (87.5) | 0.39 | 27 (96.4) | 34 (87.2) | 0.39 |

| Connect to internet via cell phone | 36 (53.7) | 18 (66.7) | 18 (45.0) | 0.08 | 15 (53.6) | 21 (53.8) | 0.98 |

| Use the internet | 43 (64.2) | 20 (74.1) | 23 (57.5) | 0.17 | 19 (67.9) | 24 (61.5) | 0.60 |

| Seek health information on the internet | 29 (65.1) | 13 (65.0) | 15 (65.2) | 0.99 | 13 (46.4) | 16 (41.0) | 0.66 |

Only 58.2% reported knowing what a clinical trial is (Table 4). When asked about feelings toward clinical trials, 68.2% had ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ positive feelings. When queried about willingness to join a trial today if asked, 42.4% stated “Yes, I definitely would” but this response differed significantly by age with younger participants (<65 years) twice as often stating willingness compared to older participants (59.3% vs. 30.8%, p = 0.02).

Table 4:

Clinical trials knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among Veterans diagnosed with cancer at the Bronx Veterans Hospital (n = 67) by age and race/ethnicity

| Age | Race/ethnicity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 67) |

<65 (n = 26, 38.8%) |

≥65 (n = 40, 59.7%) |

p- value |

Non-Hispanic African American (n = 28,41.8%) |

Other race and ethnicity (n = 39, 58.2%) |

p- value |

|

| CLINICAL TRIALS KNOWLEDGE - Know what a clinical trial is | |||||||

| Yes | 39 (58.2) | 18 (66.7) | 21 (52.5) | 0.25 | 15 (53.6) | 24 (61.5) | 0.51 |

| No | 28 (41.8) | 9 (33.3) | 19 (47.5) | 13 (46.4) | 15 (38.5) | ||

| FEELINGS TOWARD CLINICAL TRIALS | |||||||

| Very negative | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.90 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.80 |

| Somewhat negative | 2 (3.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Neutral | 19 (28.8) | 9 (33.3) | 10 (25.6) | 9 (33.3) | 10 (25.6) | ||

| Somewhat positive | 21 (31.8) | 8 (29.6) | 13 (33.3) | 9 (33.3) | 12 (30.8) | ||

| Very positive | 24 (36.4) | 9 (33.3) | 15 (38.5) | 8 (29.6) | 16 (41.0) | ||

| WILLINGNESS TO JOIN A CLINICAL TRIAL | |||||||

| If you were asked to participate in a clinical trial today, would you participate | |||||||

| Yes, I definitely would | 28 (42.4) | 16 (59.3) | 12 (30.8) | 0.02 | 15 (53.6) | 13 (34.2) | 0.14 |

| I might, not sure, it depends, | 28 (42.4) | 6 (22.2) | 22 (56.4) | 8 (28.6) | 20 (52.6) | ||

| No, I definitely would not | 10 (15.2) | 5 (18.5) | 5 (12.8) | 5 (17.9) | 5 (13.2) | ||

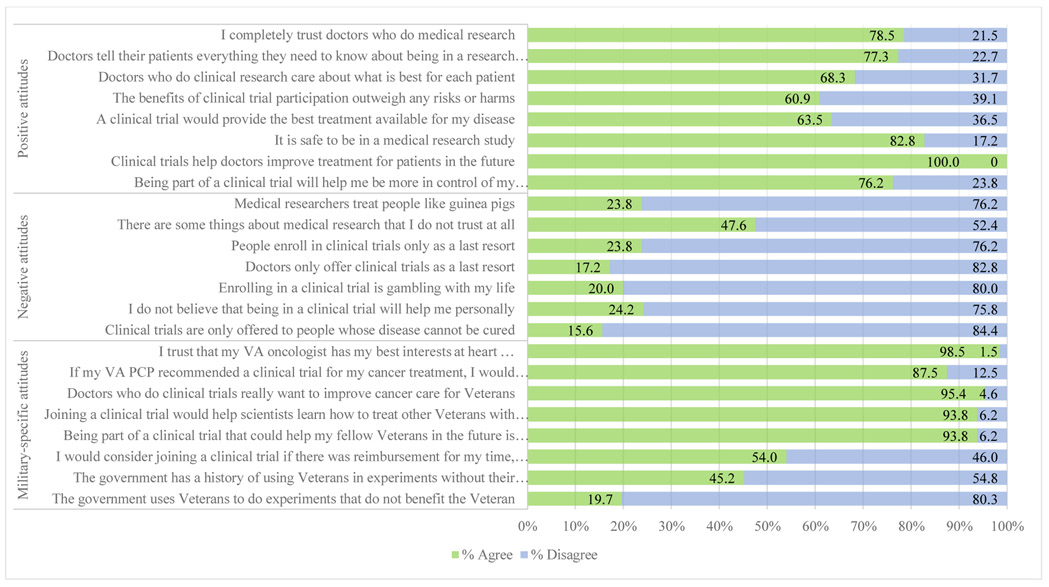

All respondents agreed that clinical trials help doctors to improve treatment for patients in the future; other commonly reported positive attitudes toward clinical trials included “It is safe to be in a medical research study” (82.8%) and “I completely trust doctors who do medical research” (78.5%) (Figure 1). Although few participants held negative beliefs regarding clinical trials, there was a single item - “There are some things about medical research that I do not trust at all,” to which nearly half of the participants (47.6%) responded with agreement. Many held positive attitudes about clinical trials as they specifically relate to Veterans. Nearly all (98.5%) stated that they believe the VA oncologist has their best interests at heart and 95.4% felt that VA doctors who conduct clinical trials want to improve care for Veterans. Most stated “being part of a clinical trial that could help my fellow Veterans in the future is important to me” (93.8%) and that joining a clinical trial would help scientists learn how to treat other Veterans with their disease in the future (93.8%). Lastly, 87.5% said they would strongly consider joining a trial if their VA primary care provider recommended doing so.

Figure 1:

Overall positive, negative, and military-specific attitudes toward clinical trials among Veterans diagnosed with cancer at the Bronx Veterans Hospital (n = 67).

Older participants (≥65 years), relative to younger participants, felt more often that being part of a clinical trial would help them be more in control of their disease and treatment (89.5% vs. 56.0%, p = 0.002), would provide the best treatment available for their disease (73.7% vs. 48.0%, p = 0.04), and that the benefits of trial participation overweighed the harms or risks (71.1% vs. 46.2%, p = 0.045) (Table 5). Military-specific attitudes did not differ by age of the participant, but when compared to participants of the other races and ethnicities, non-Hispanic black participants nearly twice as often agreed that the government has a history of using Veterans in experiments without their knowledge (62.5% vs. 34.2%, p = 0.03) and more often stated that they would consider clinical trial participation if there was reimbursement for their time, effort, and transportation (69.2% vs. 43.2%, p = 0.04).

Table 5:

Attitudes toward clinical trials among Veterans diagnosed with cancer at the Bronx Veterans Hospital (n = 67) by age and race/ethnicity.

| CLINICAL TRIAL ATTITUDES | Age | Race/ethnicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 (n = 26, 38.8%) |

≥65 (n = 40, 59.7%) |

p- value |

Non-Hispanic African American (n = 28, 41.8%) |

Other race and ethnicity (n = 39, 58.2%) |

p- value |

|

| Positive attitudes | ||||||

| Being part of a clinical trial will help me be more in control of my condition/disease and treatment | 14 (56.0) | 34 (89.5) | 0.002 | 20 (76.9) | 28 (75.7) | 0.91 |

| Clinical trials help doctors improve treatment for patients in the future | 27 (100.0) | 40 (100.0) | -- | 28 (100.0) | 39 (100.0) | -- |

| It is safe to be in a medical research study | 19 (73.1) | 34 (89.5) | 0.10 | 22 (84.6) | 31 (81.6) | 1.00 |

| A clinical trial would provide the best treatment available for my disease | 12 (48.0) | 28 (73.7) | 0.04 | 17 (65.4) | 23 (62.2) | 0.79 |

| The benefits of clinical trial participation outweigh any risks or harms | 12 (46.2) | 27 (71.1) | 0.045 | 14 (53.8) | 25 (65.8) | 0.34 |

| Doctors who do clinical research care about what is best for each patient | 16 (64.0) | 27 (71.1) | 0.56 | 17 (65.4) | 26 (70.3) | 0.68 |

| Doctors tell their patients everything they need to know about being in a research study | 19 (73.1) | 32 (80.0) | 0.51 | 20 (74.1) | 31 (79.5) | 0.61 |

| I completely trust doctors who do medical research | 19 (76.0) | 32 (80.0) | 0.70 | 20 (74.1) | 31 (81.6) | 0.47 |

| Negative attitudes | ||||||

| Clinical trials are only offered to people whose disease cannot be cured | 6 (23.1) | 4 (10.5) | 0.29 | 4 (14.8) | 6 (16.2) | 1.00 |

| I do not believe that being in a clinical trial will help me personally | 4 (15.4) | 12 (30.0) | 0.18 | 6 (22.2) | 10 (25.6) | 0.75 |

| Enrolling in a clinical trial is gambling with my life | 3 (11.5) | 10 (25.6) | 0.16 | 6 (22.2) | 7 (18.4) | 0.71 |

| Doctors only offer clinical trials as a last resort | 3 (12.0) | 8 (20.5) | 0.51 | 5 (18.5) | 6 (16.2) | 1.00 |

| People enroll in clinical trials only as a last resort | 5 (19.2) | 10 (27.0) | 0.47 | 4 (15.4) | 11 (29.7) | 0.19 |

| There are some things about medical research that I do not trust at all | 14 (53.8) | 16 (43.2) | 0.41 | 12 (44.4) | 18 (50.0) | 0.66 |

| Medical researchers treat people like guinea pigs | 6 (24.0) | 9 (23.7) | 0.98 | 5 (19.2) | 10 (27.0) | 0.47 |

| Military-specific attitudes * | ||||||

| The government uses Veterans to do experiments that do not benefit the Veteran | 7 (28.0) | 5 (13.9) | 0.20 | 8 (30.8) | 4 (11.4) | 0.06 |

| The government has a history of using Veterans in experiments without their knowledge | 12 (50.0) | 16 (42.1) | 0.54 | 15 (62.5) | 13 (34.2) | 0.03 |

| I would consider joining a clinical trial if there was reimbursement for my time, effort and travel costs | 16 (66.7) | 18 (46.2) | 0.11 | 18 (69.2) | 16 (43.2) | 0.04 |

| Being part of a clinical trial that could help my fellow Veterans in the future is important to me | 26 (100.0) | 34 (89.5) | 0.14 | 26 (96.3) | 34 (91.9) | 0.63 |

| Joining a clinical trial would help scientists learn how to treat other Veterans with my disease in the future | 25 (96.2) | 36 (92.3) | 0.64 | 26 (92.9) | 35 (94.6) | 1.00 |

| Doctors who do clinical trials really want to improve cancer care for Veterans | 27 (100.0) | 35 (92.1) | 0.26 | 28 (100.0) | 34 (91.9) | 0.25 |

| If my VA PCP recommended that I join a clinical trial for my cancer treatment, I would strongly consider doing it | 21 (80.8) | 35 (92.1) | 0.25 | 23 (85.2) | 33 (89.2) | 0.71 |

| I trust that my VA oncologist has my best interests at heart and is recommending the best treatment for my cancer | 26 (100.0) | 38 (97.4) | 1.00 | 27 (100.0) | 37 (97.4) | 1.00 |

Agreement with each statement

DISCUSSION

This study is one of very few focused on Veterans’ attitudes toward health research [36] and the only one we know of in the past decade focused on VA cancer-specific research. Our findings indicate that among a racially diverse sample of Veterans seeking care at a large urban VA medical center, none reported “very negative” attitudes and only 3.0% expressed “somewhat negative” feelings toward clinical trials. While a substantial proportion of Veterans (41.8%) were unaware of what a clinical trial is, 78.5% of Veterans stated that they trust doctors who do medical research and 87.5% reported they would strongly consider joining a trial if their VA primary care physician recommended it. Our study corroborates prior findings [37, 38] in that >93% of Veterans surveyed regardless of age or ethnicity felt that being part of a clinical trial that could help fellow Veterans in the future is important and appears to supersede concerns we detected among non-Hispanic black Veterans that the government has a history of using Veterans in experiments without their knowledge.

Our sample included a large proportion of non-Hispanic blacks and nearly exclusively comprised males (95.5%) similar to the reports of others [23, 24] but differed in that the population we studied was older (59.7% aged 65 years and older). We also found that a large proportion of Veteran participants required assistance with written materials provided by the doctor or pharmacy which may reflect the large number of participants with high school level education or less (75.6%). Limited literacy is an established barrier to clinical trial enrollment, particularly among racially and ethnically diverse populations [39]. It has been suggested that when confronted with a cancer diagnosis, patients with low or inadequate literacy struggle to understand and make decisions about treatment more so than among those with adequate literacy [39, 40]. Given the complexity of clinical trials, individuals with limited literacy can experience information overload which may result in fewer offers to participate from providers or the preference for standard treatment [10]. The influence of lower literacy may also account for the lack of awareness and knowledge of clinical trials in the current study and is an area that has not been previously evaluated and warrants further consideration.

What was most striking in our findings was the high proportion of participants who stated that they would be part of a clinical trial if it would help fellow Veterans in the future (93.8%) and would help scientists learn how to treat other Veterans with the same disease (93.8%). Commonly cited reasons for trial participation among non-military patients are to receive personal benefit from and improved access to better and more high-quality care. For members of the military, this motivation is less relevant as most Veterans have access to free high-quality care with few exceptions [36]. Instead, altruism toward fellow service members takes the fore [38].

This study was limited in that it was an observational study conducted among a relatively small number of Veterans at a large urban VA medical center. In addition, a large proportion of our study sample was non-Hispanic black and older in age which differs from reports of the typical characteristics of Veterans and may limit generalizability of our findings to other geographic areas and Veteran Administration facilities whose patient population differs in racial, ethnic, and age distribution. Additionally, 41.7% of those approached refused to participate in the survey. Those patients could have held more negative opinions of clinical trials than those who participated in the survey. That combined with the 41.8% of patients without knowledge of clinical trials suggests that there is much work to be done in the VA system to help Veterans understand the goals of clinical trials, particularly in cancer. Nonetheless, given the dearth of information about attitudes toward clinical trials among Veterans, this study provides insight to the strong sense of altruism existing in Veterans who likely struggle with infirmities of older-age as well as physical and mental issues related to their service decades in the past.

The VA system is the largest integrated health care system in the United States and boasts a history rich of adding to medical knowledge and furthering treatment options for patients with cancer [41]. In recent decades, there has been a paucity of medical data stemming from Veterans for a myriad of reasons, including the pivot in cancer research toward industry sponsored trials, increased concerns about privacy, and regulatory restrictions imposed on research conducted in the VA health care system. Our survey is an attempt to understand at least one factor – whether Veteran attitudes toward trials impact enrollment. To reverse recent trends, the VA has partnered with the NCI to boost Veteran enrollment [42] and is in the process of gaining deeper understanding of factors that limit Veteran accrual.

CONCLUSIONS

Clearly Veterans in our study were amenable to joining clinical trials. While many are aware of past misconduct in the treatment of military personnel in research, overall attitudes toward clinical trials were favorable and were especially positive when the possibility of improving cancer care for fellow Veterans was considered. Together, these findings illuminate potential interventions to increase Veteran clinical trial participation. In addition to expanding the number of clinical cancer trials that allow and encourage Veteran participation, providing access to cutting edge therapies, it also behooves us to better understand the motivations and hesitations of this population. Having trusted practitioners provide more education on the nature of clinical trials, increased transparency about every step in the research protocol, and a focus on the value that Veterans place in altruism may all contribute to improving cancer trials enrollment. Veterans with cancer are by in large an aging group with multiple comorbidities whose enrollment in future clinical trials can give them more rapid access to potentially helpful treatments while advancing therapeutic knowledge for the greater good. Ultimately, barriers at the systems level such as availability of trials to meet the special needs of Veterans and eligibility criteria that disproportionately exclude underrepresented racial and ethnic groups due to increased prevalence of comorbidities, also need to be addressed and are areas that are now receiving long overdue attention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors wish to thank Hannah Catan, MSN, RN, Katherine Lestrade, MPH, and Ivonne Cruz, MS for useful discussions about the design of this study and their assistance in survey administration and data collection.

FUNDING SOURCES:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [UG1 CA189960 and P30 CA013696]

ABBREVIATIONS:

- U.S.

United States

- VA

Veterans Administration

- MOS

Medical Outcomes Study

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Cheng SK, Dietrich MS, Dilts DM. A sense of urgency: Evaluating the link between clinical trial development time and the accrual performance of cancer therapy evaluation program (NCI-CTEP) sponsored studies. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16(22):5557–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Carlisle B, Kimmelman J, Ramsay T, et al. Unsuccessful trial accrual and human subjects protections: An empirical analysis of recently closed trials. Clinical Trials 2015;12(1):77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Khunger M, Rakshit S, Tullio K, et al. Premature clinical trial discontinuation in all and genitourinary (GU) cancers in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). J Clin Oncol 2017;35(6_suppl):394-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Williams RJ, Tse T, DiPiazza K, et al. Terminated Trials in the ClinicalTrials.gov Results Database: Evaluation of Availability of Primary Outcome Data and Reasons for Termination. PloS One 2015;10(5):e0127242–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Unger JM, Vaidya R, Hershman DL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the magnitude of structural, clinical, and physician and patient barriers to cancer clinical trial participation. JNCI 2019;111(3):245–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Barriers to patient enrollment in therapeutic clinical trials for cancer: A landscape report 2018. [Available from: https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/National%20Documents/Clinical-Trials-Landscape-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lara PN Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol 2001;19(6):1728–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hamel LM, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, et al. Barriers to clinical trial enrollment in racial and ethnic minority patients with cancer. Cancer Control 2016;23(4):327–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ibraheem A, Polite B. Improving the accrual of racial and ethnic minority patients in clinical trials: Time to raise the stakes. Cancer 2017;123(24):4752–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hillyer G, Beauchemin M, Hershman D, et al. Discordant attitudes and beliefs about cancer clinical trial participation between physicians, research staff, and cancer patients. Clinical Trials 2020;17(2):184–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Unger JM, Hershman DL, Albain KS, et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(5):536–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gross CP, Filardo G, Mayne ST, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status and race on trial participation for older women with breast cancer. Cancer 2005;103(3):483–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Avin B Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. 2017. [cited 2019]. Available from: https://biomedicalodyssey.blogs.hopkinsmedicine.org/2017/08/understanding-disparities-in-clinical-trial-enrollment/. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Williams SL. Overcoming the barriers to recruitment of underrepresented minorities. Clinical Researcher 2018;32(7). [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer 2008;112(2):228–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Byrne MM, Tannenbaum SL, Gluck S, et al. Participation in cancer clinical trials: why are patients not participating? Med Decis Making 2014;34(1):116–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rivers D, August EM, Sehovic I, et al. A systematic review of the factors influencing African Americans' participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;35(2):13–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Meropol NJ, Buzaglo JS, Millard J, et al. Barriers to clinical trial participation as perceived by oncologists and patients. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2007;5(8):655–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, et al. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol 2006;7(2):141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Unger JM, Hershman DL, Fleury ME, et al. Association of patient comorbid conditions with cancer clinical trial participation. JAMA Oncology 2019;5(3):326–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].BeLue R, Taylor-Richardson KD, Lin J, et al. African Americans and participation in clinical trials: differences in beliefs and attitudes by gender. Contemp Clin Trials 2006;27(6):498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cook WA, Doorenbos AZ, Bridges EJ. Trends in Research with U.S. Military Service Member Participants: A Population-Specific ClinicalTrials.gov Review. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2016;3:122–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Morgan RO, Teal CR, Reddy SG, et al. Measurement in Veterans Affairs Health Services Research: veterans as a special population. Health Serv Res 2005;40(5 Pt 2):1573–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Meffert BN, Morabito DM, Sawicki DA, et al. US Veterans Who Do and Do Not Utilize Veterans Affairs Health Care Services: Demographic, Military, Medical, and Psychosocial Characteristics. The primary care companion for CNS disorders 2019;21(1):18m02350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cook WA, Doorenbos AZ. Indications of recruitment challenges in research with U.S. military service members: A ClinicalTrials.gov review. Mil Med 2017;182(3):e1580–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Novak LA, Belsher BE, Freed MC, et al. Impact of financial reimbursement on retention rates in military clinical trial research: A natural experiment within a multi-site randomized effectiveness trial with active duty service members. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2019;15:100353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Campbell HM, Raisch DW, Sather MR, et al. A comparison of veteran and nonveteran motivations and reasons for participating in clinical trials. Mil Med 2007;172(1):27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Littman AJ, True G, Ashmore E, et al. How can we get Iraq- and Afghanistan-deployed US Veterans to participate in health-related research? Findings from a national focus group study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, et al. The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2012;65(10):1107–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yanez B, Pearman T, Lis CG, et al. The FACT-G7: a rapid version of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) for monitoring symptoms and concerns in oncology practice and research. Ann Oncol 2013;24(4):1073–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 2004;36(8):588–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hall MA, Camacho F, Lawlor JS, et al. Measuring trust in medical researchers. Med Care 2006;44(11):1048–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].RAND Health Care. Social Support Survey instrument scoring instructions n.d. [Available from: https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/social-support/scoring.html. [Google Scholar]

- [34].FACIT.org. FACT-G7 scoring guidelines 2020. [Available from: https://www.facit.org/facitorg/questionnaires. [Google Scholar]

- [35].IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bush NE, Sheppard SC, Fantelli E, et al. Recruitment and Attrition Issues in Military Clinical Trials and Health Research Studies. Mil Med 2013;178(11):1157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Campbell HM, Raisch DW, Sather MR, et al. A Comparison of Veteran and Nonveteran Motivations and Reasons for Participating in Clinical Trials. Mil Med 2007;172(1):27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sather M Patient beliefs about participating in experiment research (Dissertation). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Livaudais-Toman J, Burke NJ, Napoles A, et al. Health Literate Organizations: Are Clinical Trial Sites Equipped to Recruit Minority and Limited Health Literacy Patients? J Health Dispar Res Pract 2014;7(4):1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lloyd CE, Johnson MR, Mughal S, et al. Securing recruitment and obtaining informed consent in minority ethnic groups in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bates SE, Kelley MJ. VA cancer research: A legacy and a future. Semin Oncol 2019;46(4-5):305–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schiller SJ, Shannon C, Brophy MT, et al. The National Cancer Institute and Department of Veterans Affairs Interagency Group to Accelerate Trials Enrollment (NAVIGATE): A federal collaboration to improve cancer care. Semin Oncol 2019;46(4-5):308–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]