Abstract

Background & Aims:

Longitudinal data are scarce regarding the natural history and long-term risk of mortality, in children and young adults with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Methods:

This nationwide, matched cohort study included all Swedish children and young adults (≤25 years) with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD (1966–2017; n=718). NAFLD was confirmed histologically from all liver biopsies submitted to Sweden’s 28 pathology departments, and further categorized as simple steatosis or steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFLD patients were matched to ≤5 general population controls by age, sex, calendar year and county (n=3,457). To account for shared genetic and early-life factors, we also matched NAFLD patients to full-sibling comparators. Using Cox regression, we estimated multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95%CIs.

Results:

Over a median of 15.8 years, 59 NAFLD patients died (5.5/1000 person-years [PY]), compared to 36 population controls (0.7/1000PY; difference=4.8/1000PY; multivariable aHR=5.88 [95%CI=3.77–9.17]), corresponding to 1 additional death per each 15 patients with NAFLD, followed for 20 years. The 20-year absolute risk of overall mortality was 7.7% among NAFLD patients, and 1.1% among controls (difference=6.6%, 95%CI=4.0–9.2). Findings persisted after excluding subjects who died within the first 6 months (aHR=4.65, 95%CI=2.92–7.42), and after using full-sibling comparators (aHR=11.72, 95%CI=3.18–43.23). Simple steatosis was associated with a 5.26-fold higher adjusted rate of mortality, compared to controls (95%CI=3.05–9.07), and this was amplified with NASH (aHR=11.51, 95%CI=4.77–27.79). Most of the excess mortality was from cancer (1.67 vs. 0.07/1000PY; aHR=15.60, 95%CI=4.97–48.93), liver disease (0.93 vs. 0.04/1000PY; aHR=16.46, 95%CI=2.75–98.43) and cardiometabolic disease (1.12 vs. 0.14/1000PY; aHR=4.32, 95%CI=1.73–10.79).

Conclusions:

Swedish children and young adults with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD have significantly higher rates of overall, cancer-, liver- and cardiometabolic-specific mortality, compared to matched general population controls.

Keywords: pediatric NAFLD, adolescent, steatohepatitis, liver histology, survival

Lay Summary:

Currently, the natural history and long-term risk of mortality in children and young adults with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is unknown. This nationwide cohort study evaluated the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in pediatric and young adult patients in Sweden with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD, compared to matched general population controls. We found that compared to controls, children and young adults with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD and NASH have significantly higher rates of overall, cancer-, liver- and cardiometabolic-specific mortality.

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents the most common cause of chronic liver disease among children and young adults, worldwide, affecting an estimated 7.6% of the general pediatric population, and over 30% of children with obesity[1, 2]. The histological spectrum of NAFLD ranges from simple steatosis to inflammatory steatohepatitis (NASH) which can progress to fibrosis and cirrhosis[3, 4]. While the classic form of adult NASH is marked by hepatocyte ballooning with zone 3 lobular inflammation and collagen deposition, some pediatric patients develop a distinct form of NASH, characterized instead by zone 1 inflammation without ballooning, and with portal or periportal fibrosis[3, 4]. Among adults, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that simple steatosis typically follows a relatively benign disease course, whereas NASH with fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of death[5–7]. In contrast, among children and young adults with NAFLD, little is currently known about the long-term prognosis and histological correlates of survival.

It has been hypothesized that pediatric NAFLD may represent a particularly aggressive disease phenotype8. Many children with NAFLD already have fibrosis at the time of diagnosis[8–10], and rapid progression to NASH or fibrosis has been reported[11], including the development of cirrhosis in early-adulthood[12, 13]. However, whether this translates to increased mortality is still unclear. To date, published evidence is limited to one retrospective study (n=66) that found an association between pediatric NAFLD and reduced liver transplant-free survival[14]; however, with a very small, selected population and few recorded deaths, that prior study had limited power to calculate precise risk estimates. Thus, defining the long-term risk of mortality associated with pediatric and young-adult NAFLD remains an important unmet need. Given the growing worldwide burden of pediatric NAFLD, quantifying the magnitude of this risk is essential for developing effective tools for prevention, risk stratification and surveillance.

We evaluated overall and cause-specific mortality according to the presence and severity of NAFLD, using a comprehensive nationwide histopathology cohort, comprised of all children and young adults in Sweden with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD.

Methods

Study Population & Exposure

This population-based, matched cohort study used the ESPRESSO (Epidemiology Strengthened by Histopathology Reports in Sweden) cohort. ESPRESSO includes prospectively-recorded liver histopathology data from all 28 Swedish pathology departments (1966–2017), and therefore is complete for the entire country[15]. Each report includes a unique personal identity number (PIN), biopsy date, as well as topography within the liver, and morphology. We linked ESPRESSO to validated registers containing prospectively-recorded data regarding demographics, comorbidities, prescribed medications and death. ESPRESSO was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Board on August 27, 2014 (No.2014/1287–31/4). Informed consent was waived as the study was register-based[16].

We identified all histopathology specimens submitted between 1966–2016 from children and young adults aged ≤25 years, with topography codes corresponding to the liver, and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) codes corresponding to steatosis (Supplementary Methods). We included individuals ≤age 25 years in order to specifically compare outcomes in those diagnosed at <18 years of age (hereafter referred to as children), and between ages 18–25 years (hereafter, young adults). We used a validated algorithm to define NAFLD (see Validation, below); specifically, we excluded anyone with another recorded etiology of liver disease on or before the index date, including alcohol-related liver disease or a prior diagnosis of alcohol abuse/misuse or drug abuse, drug-induced liver injury, viral hepatitis B or C infection, Budd-Chiari, liver abscess, HIV/AIDS, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, other cholangitis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, prior use of a steatogenic medication, or another medication used specifically to treat another etiology of liver disease, or any pediatric-specific exclusion (as defined in Table S1), including inborn errors of metabolism. The study flowchart is shown in Figures S1A–B. After these exclusions, 718 patients were eligible for analysis.

NAFLD patients were subsequently categorized into validated histological groups (i.e. simple steatosis and NASH, with or without fibrosis), using definitions based on nationwide reporting recommendations for all pathologists in Sweden[17]. Briefly, simple steatosis was defined by at least 1 morphology code for steatosis and no additional codes for inflammation or ballooning (i.e. M5400x or M4-) or fibrosis (i.e. M4900x) or cirrhosis (i.e. M4950x). NASH with or without fibrosis was defined by at least 1 code for steatosis plus at least 1 code indicating inflammation with or without ballooning (i.e. M5400x or M4-). This definition is consistent with current clinical guidelines[18], which define pediatric NASH as hepatic steatosis with inflammation, with or without hepatocyte ballooning and/or fibrosis. Importantly, this definition also permits ascertainment of the two pediatric NASH subtypes that have been described: (1) the classical NASH subtype (i.e. “Type 1 NASH”, defined by steatosis and lobular inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning primarily in zone 3), and (2) the unique pediatric NASH subtype (i.e. “Type 2 NASH”, defined by steatosis and inflammation primarily in zone 1, without ballooning but often with portal-periportal fibrosis[3, 19, 20]).

Validation

We completed a validation study of 92 randomly selected patients from this cohort meeting our criteria for biopsy-confirmed NAFLD. Among them, a study physician (TGS) confirmed 84/92 to be NAFLD by reviewing free text from the pathologist (positive predictive value [PPV], 91.3%). The same physician was blinded to individual diagnoses of simple steatosis and NASH, and we obtained PPVs of 91.4% (43/47) for simple steatosis, and 91.1% (41/45) for NASH. Finally, we also extracted detailed data regarding the underlying indication for liver biopsy wherever possible (see Supplementary Methods).

Comparators

Each NAFLD patient was subsequently matched to ≤5 general population comparators without a recorded diagnosis of NAFLD, according to age, sex, calendar year and county. Comparators were derived from the Total Population Register[21], and identical exclusion criteria were applied (Figure S1A–B). To further account for shared genetic or early-life factors, we also conducted analyses using full siblings as comparators, as in prior work[7].

Outcomes & Covariates

All-cause mortality was ascertained from the Total Population Register, which prospectively records 93% of all deaths within 10 days, and the remaining 7% within 30 days[22]. Specific causes of death were retrieved from the Cause of Death Register[22], and defined as: liver mortality (including hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC]), cancer mortality (excluding HCC), cardiometabolic mortality (including death from cardiovascular disease or diabetes), and other/exogenous causes of death (Supplementary Methods; Table S2). No patient underwent liver transplantation during follow-up. Among young people (aged 0–44 years), the Cause of Death Register has a 98% agreement with the cause of death in the medical record[22].

The Supplementary Methods and Table S2 contain details regarding demographic and clinical covariates. Briefly, we ascertained age, sex, date of birth and emigration from the Total Population Register[21]. Education level was obtained from the Longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies database[23]. Clinical comorbidities were collected from the Patient Register, which prospectively records all data from hospitalizations (including surgeries), discharge diagnoses (1964- ) and specialty outpatient care (2001- ), and is well-validated, with positive predictive values (PPVs) for clinical diagnoses that are consistently between 85–95%[24]. Consistent with prior work and prior validation studies in the Swedish Registers[24], we defined clinical comorbidities from hospital discharge diagnoses and from outpatient specialty care letters (Table S2). To identify prior use of steatogenic medications, we used the Prescribed Drug Register, which has prospectively recorded all prescriptions dispensed from Swedish pharmacies since mid-2005, and which is well-validated and virtually complete[25].

Statistical Analysis:

Our primary analysis evaluated all-cause and cause-specific mortality in children and young adults with NAFLD, compared to matched population controls. Patients were followed from the date of the index biopsy (or the corresponding matching date among controls) until the first recorded date of death, emigration, or end of follow-up (December 31, 2016).

Incidence rates and absolute rate differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated by dividing the number of events by the number of person-years, and assuming a Poisson distribution. We also calculated 10- and 20-year absolute risks from Kaplan-Meier estimates, with 95%CIs approximated by the normal distribution. Using Cox proportional hazard regression models, we estimated multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95%CIs, conditioned on matching factors (i.e. age, sex, calendar year and county), with further adjustment for country of birth, parental education, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and metabolic comorbidities (i.e. hypertension, dyslipidemia and/or obesity), as per Table S2. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by examining the association between Schoenfeld residuals and time.

We conducted stratified analyses according to clinical risk factors, and we tested the significance of effect modification using the log likelihood ratio test. In separate models, we compared mortality risk in patients with simple steatosis and in those with NASH with and without fibrosis, and we tested for heterogeneity using the Wald test23. To evaluate specific underlying causes of mortality, we constructed cause-specific Cox regression models, in which the specific cause of death of interest was considered the event, and other causes of death were treated as competing events[26].

To address potential confounding related to intrafamilial and early-life factors, we used the Swedish Multigenerational Register, which is part of the Total Population Register[21] to identify all NAFLD patients with ≥1 full sibling without NAFLD, alive on the date of the index sibling’s biopsy. We then compared each NAFLD patient with his or her full sibling(s), after conditioning on matching set within each family.

Sensitivity analyses:

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results. First, we repeated the primary analyses after excluding any person who died within <6 months or <12 months of follow-up, with follow-up beginning at 6 or 12 months, respectively. We also compared our results after excluding patients with potentially atypical disease, such as those who underwent a second liver biopsy during follow-up, or those with hypothalamic/pituitary dysfunction, or those who underwent an index biopsy before 2 years of age. Additionally, we excluded anyone with cancer diagnosed on or prior to the index date, using the validated Swedish Cancer Register, which includes >96% of all cancers diagnosed in Sweden[27]. Second, we restricted the cohort to children <18 years at the index date. Third, although pediatric NAFLD histology existed before 1983, it was not formally described until 1983, thus we restricted the cohort to persons with index date ≥January 1, 1984. Fourth, we restricted the cohort to patients with index date ≥January 1, 2006, in whom complete medication use data were available. Fifth, to further address potential residual confounding, we constructed separate multivariable models additionally accounting for incident alcohol abuse/misuse during follow-up, and after further adjusting for incident diagnoses of other causes of liver disease. In exploratory analyses, we assessed mortality rates in patients with fibrosis, and also in patients with Type 1 NASH or Type 2 NASH, among the subgroup of 226 NASH patients whose biopsy reports included detailed text from the pathologist. We also conducted within-group comparisons, by excluding population controls and directly comparing patients with NASH to those with simple steatosis, and patients with fibrosis to those with non-fibrotic NASH. Finally, using an established, array-based approach that has previously been described, we tested the sensitivity of our data to unmeasured confounding[28].

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 3.6.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; survival package version 2.44 [Therneau, 2015, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival]). A two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results

Among 718 children and young adults with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD, 446 (62.1%) had simple steatosis, while 272 (37.9%) had NASH (Table 1). The majority of NAFLD patients (62.8%) were male, and 44% were diagnosed as children (i.e. <18 years old), with a mean age at index biopsy of 17.5 years. Compared to controls, NAFLD patients were substantially more likely to have cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other metabolic comorbidities (Table 1). Median follow-up was 15.8 years among NAFLD patients, and 16.9 years among controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Children and Young Adults* with Biopsy-Confirmed NAFLD and Matched General Population Comparators, at the Index Date

| Characteristic | Population Comparators N=3,457 | All NAFLD N=718 | Simple Steatosis N=446 | NASH N=272 | P-value4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % | 1292 [37.4] | 267 [37.2] | 157 [35.2] | 110 [40.4] | 0.96 |

| Age at the index biopsy date, years (SD) | 17.3 [7.0] | 17.5 [7.0] | 18.8 [6.4] | 15.3 [7.5] | 0.54 |

| • <1 year | 131 [3.8] | 26 [3.6] | 13 [2.9] | 13 [4.8] | 0.93 |

| • 1 to < 10 years | 391 [11.3] | 76 [10.6] | 34 [7.6] | 42 [15.4] | |

| • 10 to <18 years | 862 [24.9] | 178 [24.8] | 79 [17.7] | 99 [36.4] | |

| • 18 to ≤25 years | 2073 [60.0] | 438 [61.0] | 320 [71.7] | 118 [43.4] | |

| Years of follow-up, median (25, 75) | 16.9 [8.8–24.0] | 15.8 [7.7–23.1] | 18.2 [10.2–24.6] | 11.5 [4.8–18.6] | 0.43 |

| Start of follow-up, % | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.99 |

| • 1966 – 1989 | 475 [13.7] | 98 [13.6] | 82 [18.4] | 16 [5.9] | |

| • 1990 – 2000 | 1312 [38.0] | 273 [38.0] | 194 [43.5] | 79 [29.0] | |

| • 2001 – 2010 | 1037 [30.0] | 214 [29.8] | 111 [24.9] | 103 [37.9] | |

| • 2011 – 2016 | 633 [18.3] | 133 [18.5] | 59 [13.2] | 74 [27.2] | |

| Nordic country of birth, % | 3180 [92.0] | 626 [87.2] | 383 [85.9] | 243 [89.3] | < .001 |

| Highest education level of parents1, % | -- | -- | -- | -- | < 0.001 |

| • ≤ 9 years | 446 [14.3] | 118 [19.2] | 61 [15.2] | 57 [26.5] | |

| • 10–12 years | 1467 [47.1] | 339 [55.0] | 224 [55.9] | 115 [53.5] | |

| • ≥ 13 years | 1204 [38.6] | 159 [25.8] | 116 [28.9] | 43 [20.0] | |

| • Missing | 340 [9.8] | 102 [14.2] | 45 [10.1] | 57 [21.0] | |

| Cardiovascular Disease, % | 49 [1.4] | 49 [6.8] | 29 [6.5] | 20 [7.4] | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes2, % | 12 [0.3] | 40 [5.6] | 27 [6.1] | 13 [4.8] | < 0.001 |

| Other metabolic comorbidity3, % | 18 [0.5] | 98 [13.6] | 40 [9.0] | 58 [21.3] | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

All variables reported as mean [SD] or %, unless described otherwise. For definitions of the NAFLD histological groups and all covariates, see the Appendix (Supplementary Methods).

Children and young adults were included if they were ≤25 years old at the index biopsy or matching date

Education categories based on compulsory school, high school, and college (see Supplementary Methods). Education level was recorded beginning in 1990, thus data presented are for patients with index dates on or after January 1, 1990. For all other analyses, patients with index dates prior to 1990 had education level recorded as missing.

Diabetes included both type 1 and type 2 diabetes (as defined in Table S2).

Other metabolic comorbidity was defined as, ≥1 metabolic risk factor (i.e. dyslipidemia, hypertension and/or obesity), as outlined in the Methods and in Table S2.

P-values signify the comparison between population comparators and matched NAFLD patients. The chi squared test was used for categorical variables, while the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for median age and a t-test for mean age.

All-Cause Mortality

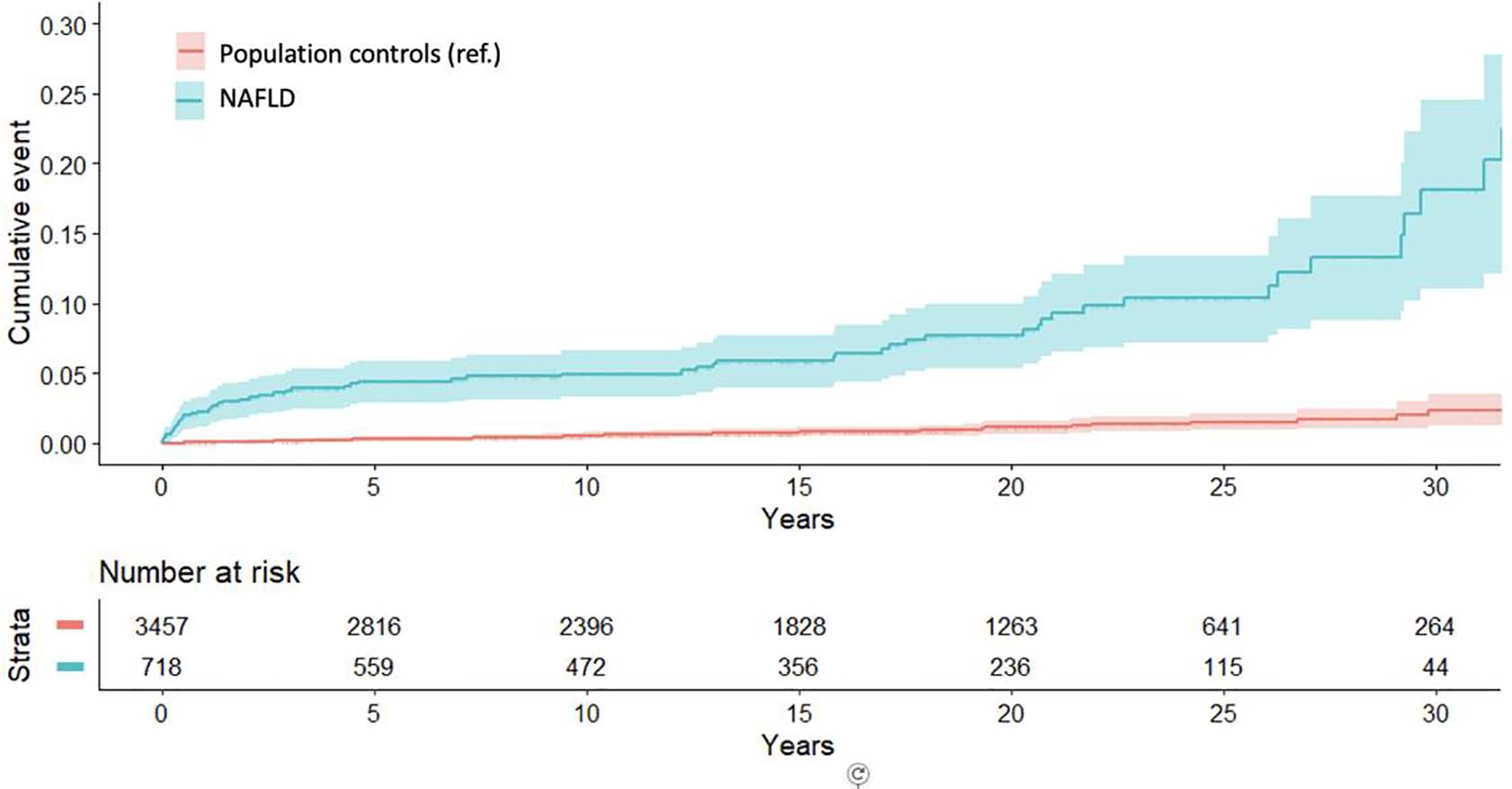

We confirmed 59 deaths among NAFLD patients (mortality rate, 5.5/1000 person-years [PY]), and 36 deaths among controls (0.65/1000PY), corresponding to an absolute rate difference of 4.8/1000PY (Table 2; Figure 1). Over 20 years, the absolute risk of overall mortality was 7.7% among NAFLD patients, and 1.1% among controls (risk difference=6.6%, 95%CI=4.0–9.2), which translated to 1 additional death per every 15 patients with NAFLD, followed for 20 years. After multivariable adjustment, NAFLD patients had a 5.88-fold higher rate of mortality, compared to controls (95%CI=3.77–9.17). In stratified models, the aHRs for overall mortality associated with NAFLD did not differ significantly between girls and boys, or between patients with and without underlying hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease (all Pheterogeneity>0.05). These rates also remained similar after ≥10 years of follow-up (aHR=5.04, 95%CI=2.68–9.50). We visually examined and formally tested the association between Schoenfeld residuals and time, and the proportional hazards assumption was not violated (Figure S2).

Table 2.

Risk of Overall Mortality Among Children and Young Adults with NAFLD and Matched Population Controls

| Overall Mortality | Population Comparators (n=3,457) | Overall NAFLD* (n=718) | Simple Steatosis (n=446) | NASH (n=272) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of deaths | 36 | 59 | 40 | 19 |

| Incidence rate1 / 1000 PY (95% CI) | 0.65 (0.47–0.88) | 5.49 (4.26–6.98) | 5.30 (3.90–7.06) | 5.93 (3.82–8.89) |

| Incidence rate difference1 /1000 PY (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 4.84 (3.42–6.25) | 4.65 (2.99–6.30) | 5.28 (2.61–7.96) |

| 20-year absolute risk2, % (95% CI) | 1.10 (0.65–1.56) | 7.69 (5.16–10.22) | 6.83 (3.96–9.71) | 9.46 (4.28–14.65) |

| 20-year absolute risk difference2, % (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 6.59 (4.02 to 9.16) | 5.73 (2.82 to 8.64) | 8.36 (3.16–13.57) |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (ref.) | 8.57 (5.66–12.97) | 8.11 (4.95–13.29) | 9.72 (4.52–20.91) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 8.93 (5.89–13.54) | 8.68 (5.27–14.30) | 10.71 (4.96–23.13) |

| Fully-adjusted Model 3, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 5.88 (3.77–9.17) | 5.26 (3.05–9.07) | 11.51 (4.77–27.79) |

| P-value3 | -- | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; N., number; PY, person years; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref., reference

NAFLD was defined by liver histology using a validated algorithm. For definitions and algorithm, please see the Supplementary Methods.

Confidence intervals for incidence rates and rate differences were approximated based on a Poisson distribution. Incidence rate difference is per 1000 person years, and P-values for comparisons between population comparators vs. overall NAFLD, simple steatosis and NASH were approximated by the normal distribution (with all P-values <0.001).

20-year absolute risks and absolute risk differences [percentage points] were calculated from Kaplan-Meier estimates.

The multivariable-adjusted model 2 accounted for matching factors (age at the index date, sex, county of residence in Sweden and calendar year). The full multivariable-adjusted model 3 accounted for age at the index date, sex, county of residence in Sweden, calendar year, country of birth, parental education level, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other metabolic comorbidities, defined as a composite categorical variable including any of the following conditions: obesity, hypertension and/or dyslipidemia. For definitions, see Table S2. P-values in the table are from multivariable-adjusted Model 3, for each comparison between population comparators vs. overall NAFLD, vs. simple steatosis and vs. NASH.

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Overall Mortality Among Pediatric and Young-Adult Patients with NAFLD and Matched Population Controls.

Shown is the cumulative incidence of overall mortality among pediatric and young-adult patients with NAFLD and matched general population controls. Pediatric and young-adult NAFLD was defined from all prospectively recorded liver histology specimens from patients ≤25 years of age in Sweden, using a validated algorithm, after the exclusion of other causes of liver disease (see Methods and Appendix for details). Each NAFLD patient was matched to up to 5 population controls without recorded NAFLD according to age, sex, calendar year and county of residence in Sweden. P-value <0.001 for the absolute incidence rate difference for overall mortality between population comparators and NAFLD patients; P-value was approximated by the normal distribution. Abbreviations: NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; ref., reference group

Risk of overall mortality increased with worsening NAFLD severity. Compared to controls, the 20-year absolute risk of mortality was 5.7% higher with simple steatosis (95%CI=2.8–8.6), and 8.4% higher with NASH (95%CI=3.2–13.6)(Table 2). After multivariable adjustment, we observed a 5.26-fold higher rate of death with simple steatosis (95%CI=3.05–9.07), and an 11.51-fold higher rate in patients with NASH (95%CI=4.77–27.79).

Cause-Specific Mortality

NAFLD patients had significantly increased mortality from cancer (1.67 vs. 0.07/1000PY; difference=1.6/1000PY), cardiometabolic disease (1.12 vs. 0.14/1000PY; difference=1.0/1000PY), liver disease (0.93 vs. 0.04/1000PY; difference=0.9/1000PY) and other/exogenous causes (1.8 vs. 0.4/1000PY; difference=1.4/1000PY), compared to controls (Table 3). These positive associations persisted after multivariable adjustment (aHRs for mortality from cancer, cardiometabolic disease, liver disease and other/exogenous causes: 15.60 [95%CI=4.97–48.93], 4.32 [95%CI=1.73–10.79], 16.46 [95%CI=2.75–98.43], and 3.62 [95%CI=1.89–6.93], respectively).

Table 3.

Risk of Cause-Specific Mortality Among Children and Young Adults with NAFLD and Matched General Population Controls

| Population Comparators (n=3,457) | Overall NAFLD* (n=718) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Mortality (excluding HCC), N. of deaths | 4 | 18 |

| Incidence rate1 / 1000 PY (95% CI) | 0.07 (0.03–0.16) | 1.67 (1.06–2.53) |

| Incidence rate difference1 /1000 PY (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 1.60 (0.83–2.38) |

| 10-year risk difference2 (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 1.77 (0.74–2.8) |

| 20-year risk difference2 (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 2.30 (0.91–3.69) |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (ref.) | 23.07 (7.81–68.19) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 23.86 (8.06–70.62) |

| Fully-adjusted Model 3, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 15.60 (4.97–48.93) |

| P-value3 | -- | <0.001 |

| Cardiometabolic Mortality 4 , N. of deaths | 8 | 12 |

| Incidence rate1 / 1000 PY (95% CI) | 0.14 (0.07–0.26) | 1.12 (0.64–1.83) |

| Incidence rate difference1 /1000 PY (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 0.97 (0.33–1.61) |

| 10-year risk difference2 (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 0.36 (−0.14–0.86) |

| 20-year risk difference2 (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 0.86 (−0.1–1.83) |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (ref.) | 8.23 (3.36–20.16) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 8.73 (3.52–21.65) |

| Fully-adjusted Model 3, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 4.32 (1.73–10.79) |

| P-value3 | -- | <0.01 |

| Liver Mortality (including HCC), N. of deaths | 2 | 10 |

| Incidence rate1 / 1000 PY (95% CI) | 0.04 (0.01–0.10) | 0.93 (0.51–1.59) |

| Incidence rate difference1 /1000 PY (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 0.89 (0.32–1.47) |

| 10-year risk difference2 (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 0.78 (0.05–1.51) |

| 20-year risk difference2 (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 1.26 (0.26–2.26) |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (ref.) | 27.01 (5.91–123.54) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 32.64 (6.77–157.28) |

| Fully-adjusted Model 3, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 16.46 (2.75–98.43) |

| P-value3 | -- | <0.01 |

| Other/Exogenous Mortality 5 , N. of deaths | 22 | 19 |

| Incidence rate1 / 1000 PY (95% CI) | 0.40 (0.26–0.58) | 1.77 (1.14–2.65) |

| Incidence rate difference1 /1000 PY (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 1.37 (0.56–2.18) |

| 10-year risk difference2 (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 1.60 (0.48–2.72) |

| 20-year risk difference2 (95% CI) | 0 (ref.) | 2.38 (0.72–4.04) |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 (ref.) | 4.42 (2.39–8.16) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 4.59 (2.48–8.50) |

| Fully-adjusted Model 3, HR (95% CI)3 | 1 (ref.) | 3.62 (1.89–6.93) |

| P-value3 | -- | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; N., number; PY, person years; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref., reference

NAFLD was defined by liver histology using a validated algorithm (see the Supplementary Methods).

Confidence intervals for incidence rates and rate differences were calculated based on a Poisson distribution. Incidence rate difference is per 1000 person years.

10- and 20-year absolute risks and risk differences [percentage points] were calculated from Kaplan-Meier estimates.

The multivariable-adjusted model 2 accounted for matching factors (age at the index date, sex, county of residence in Sweden and calendar year). The full multivariable-adjusted model 3 included model 2 and further adjusted for country of birth, parental education level, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other metabolic comorbidities, defined as a composite categorical variable (including any of the following conditions: obesity, hypertension and/or dyslipidemia). For definitions, see Table S2. P-values in the table are from multivariable-adjusted Model 3, for each comparison between population comparators vs. overall NAFLD.

Cardiometabolic mortality included death from either cardiovascular causes or from diabetes (see Methods for details).

For a complete list of the specific causes of “Other/Exogenous” causes of death, see Table S3.

Full-Sibling Comparators

We identified all NAFLD patients with ≥1 full-sibling comparator without diagnosed NAFLD, who was alive at the index date (n=424 NAFLD patients; n=626 siblings; Table S4). Consistent with our primary analyses, overall mortality rates were significantly higher among NAFLD patients, compared to sibling controls (5.2/1000PY vs. 0.7/1000PY; rate difference, 4.5/1000PY). After accounting for matching factors within each family, the hazard ratio for death was 11.72-fold higher among NAFLD patients, compared to full-sibling controls (95%CI=3.18–43.23).

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings were robust across all sensitivity analyses, including: (1) after excluding patients who died within the first 6 months (aHRoverall mortality for NAFLD vs. controls=4.65, 95%CI=2.92–7.42)(Tables S5A–B), or the first 12 months (aHR=4.45, 95%CI=2.75–7.22); (2) after excluding patients with potentially atypical disease, including patients with a second biopsy during follow-up (aHR=5.75, 95%CI=3.61–9.15), or patients with hypothalamic/pituitary dysfunction (aHR=5.88, 95%CI=3.77–9.17), or patients with very early index biopsy at <2 years of age (aHR=4.07, 95%CI=2.46–6.75); (3) after restricting the cohort just to children (i.e. index biopsy <18 years)(aHR=16.25, 95%CI=7.12–37.07)(Table S6A), or to children with index biopsy at age >12 months but <18 years (aHR=17.42, 95%CI=6.24–48.66)(Table S6B); (4) after limiting the start date to January 1, 1984 (aHR=6.50, 95%CI=3.95–10.71)(Table S7), or after limiting the start date to January 1, 2006, when complete medication use data were available (aHR=6.19, 95%CI=1.53–25.06); (5) after further accounting for incident alcohol abuse/misuse during follow-up (aHR=4.21, 95%CI=2.38–7.60), and also after further adjusting for incident diagnoses of other liver diseases, during follow-up (aHR=5.53, 2.67–11.43). Moreover, our findings also remained similar after excluding anyone with cancer diagnosed on or before the index date (aHR=4.69, 95%CI=2.77–7.94; Table S8). In exploratory analyses, patients with fibrosis had significantly higher mortality rates compared to controls (difference, 3.4/1000PY), as did patients with both Type 1 and Type 2 NASH (differences, 5.2/1000PY and 5.3/1000PY, respectively]); however, with relatively small numbers in those subgroups, the findings should be interpreted cautiously. We also conducted exploratory analyses after excluding controls, and found modest yet significantly higher rates of overall mortality in patients with NASH, compared to simple steatosis (difference, 0.7/1000PY, 95%CI=0.1–1.3). In contrast, mortality rates were not significantly different when patients with fibrosis (n=166) were compared to those with non-fibrotic NASH (n=106; difference, 0.4/1000PY, 95%CI= −0.2–1.1), nor did we observe significant differences in rates of cancer-, cardiometabolic- and liver-specific mortality when patients with NASH were compared to those with simple steatosis; however, those exploratory analyses were limited by small numbers. Finally, we found that an unmeasured confounder would need to have an implausibly strong association with mortality and also be very highly imbalanced, to attenuate our results (Table S9). Specifically, even if a confounder had an aHR ≥10.0 for overall mortality and ≥90% difference in prevalence between groups, the lower limit of our 95% confidence interval would still exceed 1.0.

Discussion

In this large, nationwide population, both children and young adults with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD had significantly increased mortality from all causes and from cancer, cardiometabolic disease and liver disease, compared to matched population controls. Rates of mortality in NAFLD patients were 5.88-fold higher than in matched controls, corresponding over 20 years to an absolute excess risk of 6.6%, or one additional death per each 15 patients diagnosed with pediatric or young-adult NAFLD. Moreover, this excess mortality increased with worsening NAFLD histology, such that patients with NASH had an 11-fold higher rate of death, compared to controls. These findings were consistent regardless of age, sex, duration of follow-up and underlying cardiometabolic comorbidities. They also persisted when we compared NAFLD patients to full siblings, rendering it unlikely that inherited or early-life factors fully explain the substantial burden of excess mortality associated with pediatric and young-adult NAFLD.

Our findings are broadly consistent with one prior study that followed 66 children with NAFLD for a mean of 6.4 years, and found that NAFLD patients had reduced liver transplant-free survival, compared to age-standardized U.S. controls[14]. However, that prior study was substantially limited by a small, single-center design, with only 29 cases of biopsy-confirmed NAFLD and 2 recorded deaths, resulting in imprecise risk estimates and poor generalizability. In contrast, the current study leveraged a population-based cohort with a larger number of pediatric and young-adult subjects, longer follow-up time and more recorded deaths than any prior histology-based study, to date; this in turn permitted the calculation of more precise, quantitative estimates of mortality risk, on a nationwide scale.

To our knowledge, no prior nationwide study has examined histological correlates of survival in pediatric and young-adult NAFLD. We observed that even simple steatosis was associated with significantly increased overall mortality, and that risk was further amplified in patients with NASH. Although the presence of fibrosis was also associated with increased mortality, the magnitude of that risk did not differ substantially from that found in non-fibrotic NASH. This could suggest that, among children and young adults, NASH may represent a more important and reliable histological predictor of survival. However, our study was not specifically powered to assess mortality according to the presence or severity of fibrosis; thus, further research is still needed to precisely define the relative contributions of pediatric NASH with or without fibrosis to long-term survival.

Most of the excess deaths associated with pediatric and young-adult NAFLD were from cancer, cardiometabolic disease or liver disease, findings that are supported by data from adult NAFLD populations[7, 29, 30]. While the absolute excess rates of cancer-, cardiometabolic- and liver-specific mortality in our pediatric and young-adult NAFLD patients appear modest (i.e. 1.6, 1.0 and 0.9 per 1000 person-years, respectively), they are clinically very important, for they translate over 20 years to 1 additional cancer death per each 32 children with NAFLD, 1 additional cardiometabolic death per each 50 children with NAFLD, and 1 additional liver-related death per each 56 children with NAFLD. Thus, our findings strongly support the need to improve existing strategies for prevention, risk stratification and surveillance, for this growing population.

We considered whether the relationship between NAFLD and premature death merely reflected an association with obesity. Consistent with other large-scale administrative datasets, the recorded prevalence of obesity in the Swedish Registers is low, which is likely from missing data (see Supplementary Appendix), and our study also lacked detailed assessments of body mass index (BMI) or visceral fat. While this could introduce residual confounding, our findings remained similar after adjusting for metabolic comorbidities, including obesity, diagnoses which have a high PPV (85–95%) in the Swedish Registers[24]. Moreover, robust evidence demonstrates that pediatric and young-adult obesity contributes only modestly to premature mortality (incidence rate ratio, 1.40 per each SD of BMI [95%CI=1.20–1.63][31]; adjusted HRs=1.5–1.8, comparing the highest vs. lowest childhood BMI quartiles)[32, 33]. To that end, our sensitivity analysis demonstrated that our results are very robust to unmeasured confounding; specifically, even an implausible confounder with an adjusted HR≥10.0 for mortality and ≥90% difference in prevalence between groups would not fully attenuate our results. Thus, the excess mortality observed with pediatric and young-adult NAFLD likely far exceeds that which is explained by obesity, alone.

This study benefits from the inclusion of all prospectively-recorded liver histopathology in Sweden, permitting construction of a complete, nationwide population of all children and young adults with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD. We also applied strict and validated definitions of NAFLD and confounding variables, in registers with near-complete follow-up for the entire Swedish population. Our larger sample size and longer follow-up time permitted calculation of more precise, population-level risk estimates, while minimizing the inherent limitations of previous, smaller studies. We also applied diverse analytical techniques to minimize potential bias from reverse causation and residual confounding, and the use of full-sibling comparators addressed important intrafamilial and early-life factors. Overall, our findings support a relationship between pediatric and young-adult NAFLD and excess mortality risk, that appears to exceed the risk from individual metabolic factors alone.

We acknowledge several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study and NAFLD was defined histologically, but not all children and young adults with NAFLD undergo biopsy, which could lead to selection bias. For this reason, future large-scale studies are needed with long-term follow-up from unselected populations, focused on all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Nevertheless, biopsy is recommended by subspecialty guidelines[18], and our case distribution, hazard estimates and absolute mortality rates are consistent with the limited published data in this area[14], which supports the generalizability of our results. Second, the Swedish population is primarily Caucasian, with a relatively low prevalence of pediatric obesity (~8.5% of boys, 4.7% of girls)[34]; thus, while our study is the largest to date, several of our exploratory subgroups were underpowered, and additional studies are needed in larger, diverse populations. Third, pathology data is subject to inter-observer variability and sampling error, and our dataset did not comprehensively identify hepatocyte ballooning, which may have been under-reported in older liver biopsies. However, hepatocyte ballooning is not typically observed in “Type 2” pediatric NASH, and our validation study confirmed the accuracy of our exposure definitions (Methods), including a PPV of 91.1% for NASH. Fourth, our population controls or full-sibling controls may have included patients with undiagnosed NAFLD, which could introduce misclassification; however, in our exploratory NAFLD-only subgroup analysis we observed similar patterns of association, including significantly higher rates of overall mortality among patients with NASH, compared to simple steatosis. Although we reviewed the underlying indication for biopsy in a random subset (Supplementary Methods), we lacked comprehensive information about the indication for liver biopsy in the full cohort. Fifth, despite matching, multivariable adjustment and exclusion of potentially confounding diagnoses, misclassification and residual confounding is still possible, and we lacked detailed data regarding other measures of adiposity, age of puberty, smoking or alcohol use. Accordingly, large-scale, prospective histology cohort studies are warranted, both to validate our findings and to more fully characterize potential causal links between pediatric NAFLD and both all-cause and cause-specific mortality, including cancer mortality and other/exogenous causes of death. Finally, while changing trends in diagnostic strategies could have impacted our findings, all models accounted for calendar year, and our results were consistent in more recent time-periods.

In conclusion, within a nationwide, population-based cohort of children and young adults, biopsy-confirmed NAFLD was associated with significantly increased risk of overall mortality, and the magnitude of that risk was amplified in patients with NASH. Most of the excess deaths associated with NAFLD were from cancer, cardiometabolic disease or liver disease. Together, our findings underscore the need for improved prevention, risk stratification and surveillance strategies to improve long-term outcomes for this growing patient population.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Biopsy-proven pediatric and young-adult NAFLD contributes to substantial excess mortality.

Mortality is increased with simple steatosis, and further amplified with steatohepatitis.

This excess mortality was primarily from cancer, cardiometabolic disease and liver disease.

Funding Sources:

NIH K23 DK122104 (TGS)

Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Career Development Award (TGS)

Dana Farber / Harvard Cancer Center GI SPORE Career Enhancement Award (TGS)

Crohns and Colitis Foundation Senior Research Award (HK)

Karolinska Institutet (JFL)

Role of the Funding Source:

No funding organization had any role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, and analysis of the data; or in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests:

JFL coordinates a study on behalf of the Swedish IBD quality register (SWIBREG), that has received funding from Janssen corporation. TGS reports research grants to her institution from Amgen, and has served as a consultant to Aetion for work unrelated to this manuscript. HK has received research funding from Takeda and Pfizer, and has received consulting fees from Takeda for work unrelated to this manuscript. HA has received consulting fees from Takeda, Baxter and Mirum Inc for work unrelated to this manuscript. The remaining authors have no disclosures and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

List of Abbreviations (alphabetical):

- aHR

Adjusted hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- ESPRESSO

Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden

- ICD

International classification of diseases

- NAFLD

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PY

Person-Years

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- SNOMED

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine

Footnotes

Details of ethics approval: This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee, Stockholm, Sweden (Protocol number: 2014/1287-31/4).

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available due to Swedish regulations.

Transparency statement: Dr. Simon affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES:

- [1].Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Anderson EL, Howe LD, Jones HE, Higgins JP, Lawlor DA, Fraser A. The Prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one 2015;10:e0140908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Newbury R, Deutsch R, Nievergelt C, Schork NJ, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005;42:641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Alkhouri N, De Vito R, Alisi A, Yerian L, Lopez R, Feldstein AE, et al. Development and validation of a new histological score for pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2012;57:1312–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Taylor RS, Taylor RJ, Bayliss S, Hagstrom H, Nasr P, Schattenberg JM, et al. Association Between Fibrosis Stage and Outcomes of Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Simon TG, Roelstraete B, Khalili H, Hagstrom H, Ludvigsson JF. Mortality in biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: results from a nationwide cohort. Gut 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Patton HM, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, Schwimmer JB, Kleiner D, Molleston J, et al. Clinical correlates of histopathology in pediatric nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1961–1971 e1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Africa JA, Behling CA, Brunt EM, Zhang N, Luo Y, Wells A, et al. In Children With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Zone 1 Steatosis Is Associated With Advanced Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:438–446 e431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mann JP, De Vito R, Mosca A, Alisi A, Armstrong MJ, Raponi M, et al. Portal inflammation is independently associated with fibrosis and metabolic syndrome in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2016;63:745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Van Natta ML, Molleston JP, Murray KF, Rosenthal P, et al. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: the TONIC randomized controlled trial. Jama 2011;305:1659–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE, Stanley C, Behling C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2006;118:1388–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kinugasa A, Tsunamoto K, Furukawa N, Sawada T, Kusunoki T, Shimada N. Fatty liver and its fibrous changes found in simple obesity of children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1984;3:408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Feldstein AE, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Treeprasertsuk S, Benson JT, Enders FB, Angulo P. The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a follow-up study for up to 20 years. Gut 2009;58:1538–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ludvigsson JF, Lashkariani M. Cohort profile: ESPRESSO (Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden). Clin Epidemiol 2019;11:101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ludvigsson JF, Haberg SE, Knudsen GP, Lafolie P, Zoega H, Sarkkola C, et al. Ethical aspects of registry-based research in the Nordic countries. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:491–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Förening för Patologi – Förening för Klinisk Cytologi V, April 4, 2019. http://www.svfp.se/foreningar/uploads/L15178/kvast/lever/Leverbiopsier2019.pdf; Accessed November 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vos MB, Abrams SH, Barlow SE, Caprio S, Daniels SR, Kohli R, et al. NASPGHAN Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;64:319–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Goldner D, Lavine JE. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Unique Considerations and Challenges. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1967–1983 e1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Carter-Kent C, Yerian LM, Brunt EM, Angulo P, Kohli R, Ling SC, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children: a multicenter clinicopathological study. Hepatology 2009;50:1113–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, Ljung R, Michaelsson K, Neovius M, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brooke HL, Talback M, Hornblad J, Johansson LA, Ludvigsson JF, Druid H, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olen O, Bruze G, Neovius M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:423–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, Leimanis A, Otterblad Olausson P, Bergman U, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register--opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the Analysis of Survival Data in the Presence of Competing Risks. Circulation 2016;133:601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talback M. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol 2009;48:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schneeweiss S Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J, Soni M, Prokop LJ, Younossi Z, et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2017;65:1557–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Allen AM, Hicks SB, Mara KC, Larson JJ, Therneau TM. The risk of incident extrahepatic cancers is higher in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease than obesity - A longitudinal cohort study. J Hepatol 2019;71:1229–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Sievers ML, Bennett PH, Looker HC. Childhood obesity, other cardiovascular risk factors, and premature death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:485–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Must A, Jacques PF, Dallal GE, Bajema CJ, Dietz WH. Long-term morbidity and mortality of overweight adolescents. A follow-up of the Harvard Growth Study of 1922 to 1935. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1350–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gunnell DJ, Frankel SJ, Nanchahal K, Peters TJ, Davey Smith G. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular mortality: a 57-y follow-up study based on the Boyd Orr cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:1111–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Collaboration NCDRF. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017;390:2627–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.