Abstract

Background: The association between vitamin C and metabolic syndrome (MetS) has been evaluated in several epidemiological studies with conflicting results. This meta-analysis was therefore employed to further investigate the above issue.

Methods: The observational studies on the associations of dietary and circulating (serum and plasma) vitamin C levels with MetS were searched in the PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase database up to April 2021. The pooled relative risk (RR) of MetS for the highest vs. lowest dietary and circulating vitamin C levels and the standard mean difference (SMD) of dietary and circulating vitamin C levels for MetS vs. control subjects were calculated, respectively.

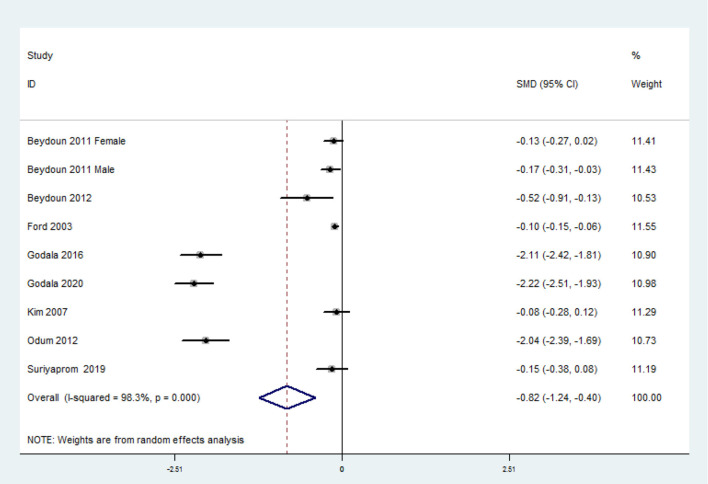

Results: A total of 28 observational studies were identified in this meta-analysis. Specifically, 23 studies were related to the dietary vitamin C level. The overall multivariable-adjusted RR demonstrated that the dietary vitamin C level was inversely associated with MetS (RR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.88–0.97; P = 0.003). Moreover, the overall combined SMD showed that the dietary vitamin C level in MetS was lower than that in control subjects (SMD = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.08 to −0.01; P = 0.024). With regard to the circulating vitamin C level, 11 studies were included. The overall multivariable-adjusted RR demonstrated that the circulating vitamin C level was inversely associated with MetS (RR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.49–0.74; P < 0.001). In addition, the overall combined SMD showed that the circulating vitamin C level in MetS was lower than that in control subjects (SMD=-0.82, 95%CI: −1.24 to −0.40; P < 0.001).

Conclusions: Current evidence suggests that both dietary and circulating vitamin C level is inversely associated with MetS. However, due to the limitation of the available evidence, more well-designed prospective studies are still needed.

Keywords: dietary vitamin C, circulating vitamin C, metabolic syndrome, meta-analysis, observational studies

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is defined as the presence of the following five metabolic abnormalities (at least three): elevated waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides, and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (1). Affecting 25% of the population in the developed world, MetS has been considered an important public health issue in parallel to obesity and diabetes (2). Although the etiology of MetS is not well-understood yet, dietary factors are thought to be involved in MetS (3).

Vitamin C, an essential water-soluble micronutrient traditionally utilized to prevent and treat scurvy (also known as ascorbic acid), is one of the most common antioxidants. Fruit and vegetable consumption, which are equipped with abundant vitamin C, have been demonstrated to be inversely associated with MetS in our previous study (4). Moreover, vitamin C consumption is associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes (5) and hypertension (6). Fundamentally, the induction of vitamin C deficiency could lead to a phenotype characterized by insulin resistance, weight gain, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis (7). Above all, it is speculated that vitamin C levels may be negatively associated with MetS.

To the best of our knowledge, a number of observational studies have examined the associations of dietary and circulating vitamin C level with MetS (8–35). However, no final conclusion can be obtained. Thus, the present meta-analysis of observational studies was employed to investigate the issue further. It was hypothesized that the dietary and circulating vitamin C was inversely associated with MetS.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

Our meta-analysis was performed according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (36). The PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase electronic database were searched during April 2021 by using a combination of keywords and in-text words related to MetS (“metabolic syndrome”) and vitamin C (“vitamin C” and “ascorbic acid”). No language and MetS diagnostic criteria restrictions were set in the search strategy. The titles and abstracts of all articles were first screened. Then, the full articles were read to identify the eligible studies. Moreover, the reference lists for the retrieved articles were reviewed to include additional studies.

Study Selection

Two researchers (YZ and JD) reviewed the titles, abstracts, and full texts of all retrieved studies independently. Disagreements were resolved by discussions and mutual consultations. The included studies were required to meet the following criteria: (1) the study design was an observational study; (2) the outcomes included the associations of dietary and circulating vitamin C level with MetS; and (3) the relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), or standard mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported. The exclusion criteria were listed as follows: (1) duplicated or irrelevant articles; (2) reviews, letters, or case reports; (3) randomized controlled trials; and (4) non-human studies.

Data Extraction

Two researchers extracted the data (YZ and JD) independently, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. The information about the first author, year of publication, location, age, gender, sample size, study design, adjustments, exposure, category of exposure, effect estimates, adjustments, and diagnostic criteria of MetS, were collected. The corresponding effect estimates with 95% CIs for the highest vs. lowest dietary levels and the circulating vitamin C level were extracted (adjusted for the maximum number of confounding variables). Moreover, the dietary and the circulating vitamin C levels (mean ± SD) were also extracted to calculate the SMD (MetS vs. control).

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment was conducted according to the Newcastle–Ottawa (NOS) criteria for non-randomized studies, which is based on three broad perspectives: the selection process of study cohorts, the comparability among different cohorts, and the identification of exposure or outcome of study cohorts. Disagreements with respect to the methodological quality were resolved by discussion and mutual consultation. Studies in other languages were translated into English for evaluation. A study awarded seven or more stars were considered high-quality (37), which was the basis for subgroup analysis for study quality.

Statistical Analyses

The RR for MetS and SMD for dietary and circulating vitamin C levels were the outcome measures in the present study. The I2 statistic, which measures the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity, was examined (I2 > 50% was considered heterogeneity). If significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies, the random-effects model was used; otherwise, the fixed effects model was accepted. Begg's test was employed to assess the publication bias (38). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Moreover, subgroup analysis for study design, diagnostic criteria of MetS, geographical region, sample size, exposure assessment, study quality, adjustment of BMI, and physical activity was conducted for RR analysis. In addition, subgroup analysis for diagnostic criteria of MetS, geographical region, sample size, study quality, and exposure assessment was employed for SMD analysis. Of note, Kim et al. separated their effect estimates by high and low physical activity (PA), which served as two independent datasets (22).

Results

Study Identification and Selection

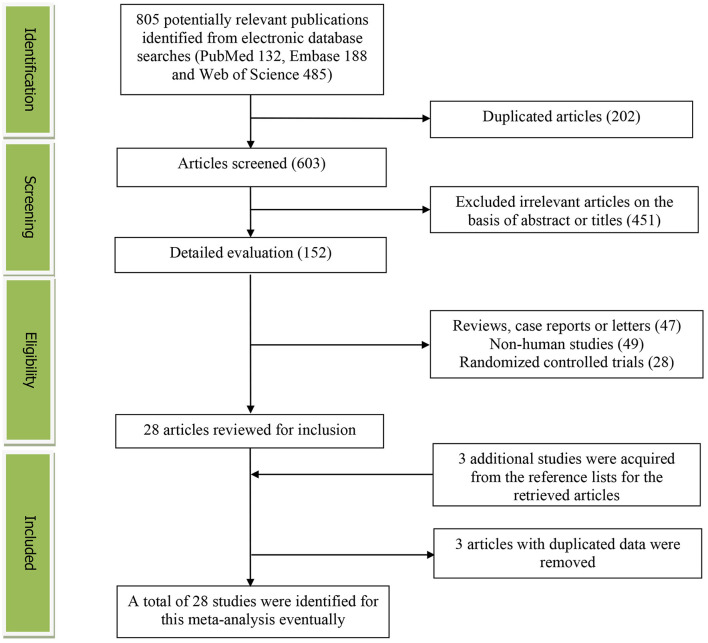

Figure 1 presents the detailed flow diagram of the study identification and selection. A total of 805 potentially relevant articles (PubMed: 132, Embase: 188, and Web of Science: 485) were retrieved during the initial literature search. After eliminating 202 duplicated articles, 603 articles were screened according to the titles and abstracts and 451 irrelevant studies were excluded. Then, 47 reviews, case reports, or letters; 49 non-human studies; and 28 randomized control trials studies were removed, respectively. Thereafter, three additional studies were acquired from the reference lists for the retrieved articles (33–35). Moreover, three studies were excluded for duplicated data (39–41). Eventually, a total of 28 studies were selected for this meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

The detailed flow diagram of the study identification and selection in this meta-analysis.

Study Characteristics

The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in Supplementary Table 1. These studies were published between 2003 and 2021. Sixteen of them were performed in Asian countries [Korea (9–11, 19, 22–25, 35), China (17, 18, 20, 27), Thailand (31), Iran (33), and Saudi Arabia (16)], and four were conducted in European countries [Poland (21, 26), France (29), and Finland (13)]. The other eight studies were from the US (8, 12, 14, 15), Canada (32), Ecuador (28), Brazil (34), and Nigeria (30). Both male and female participants were considered, except for Bruscate's study (34). The sample size ranged from 143 to 27,656 for a total number of 110,771. The dietary vitamin C level was assessed by food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) in four studies (8, 10, 15, 20), a 24-h or 3-day recall in 18 studies (9, 11, 12, 14, 16–19, 21–27, 33–35), and a 4-day record in one study (13). The criteria for MetS were National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) and International Diabetes Federation (IDF) in 17 (8–13, 17–19, 23–25, 27, 29–31, 35) and seven studies (14, 16, 21, 26, 28, 33, 34), respectively. Moreover, American Heart Association (AHA) (15, 20) and Joint Interim Statement (JIS) (22, 32) were also utilized.

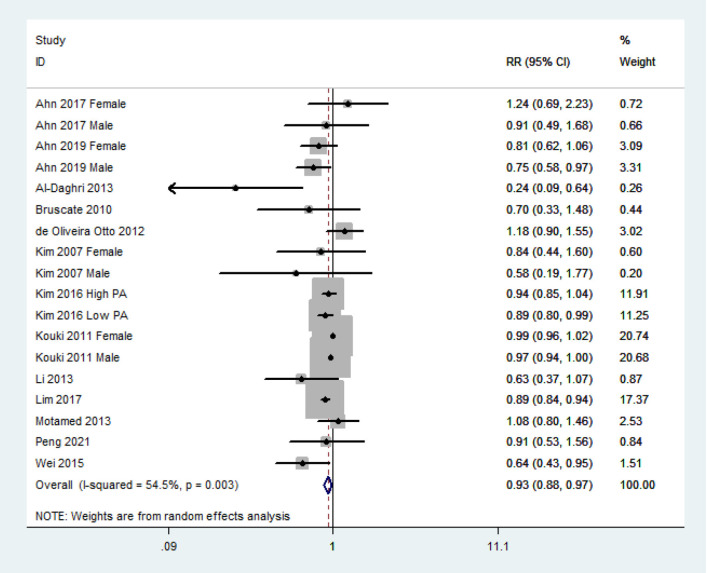

RR of MetS for the Highest vs. Lowest Dietary Vitamin C Category

The overall multivariable-adjusted RR demonstrated that the dietary vitamin C level was negatively associated with MetS (RR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.88–0.97; P = 0.003) (Figure 2). A substantial level of heterogeneity was obtained among various studies (P = 0.003, I2 = 54.5%). No evidence of publication bias existed according to Begg's rank correlation test (P = 0.495). The results of subgroup analysis are presented in Table 1. The above findings were confirmed in crosssectional (RR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.87–0.97; P = 0.001), NCEP ATP III (RR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89–0.99; P = 0.01), and 24-h or 3-day recall (RR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.86 to 0.93; P < 0.001) studies.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of meta-analysis. Overall multi-variable adjusted RR of MetS for the highest vs. lowest category of dietary vitamin C level.

Table 1.

Subgroup analysis of MetS for the highest vs. lowest dietary vitamin C level category.

| Stratification | Number of studies | Pooled RR | 95% CI | P-value | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 13 | 0.93 | 0.88, 0.97 | P = 0.003 | P = 0.003; I2 = 54% |

| Study design | |||||

| Crosssectional | 11 | 0.92 | 0.87, 0.97 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.002; I2 = 57% |

| Cohort | 2 | 1.12 | 0.88, 1.43 | P = 0.36 | P = 0.40; I2 = 0% |

| Diagnostic criteria of MetS | |||||

| NCEP ATP III | 7 | 0.94 | 0.89, 0.99 | P = 0.01 | P = 0.03; I2 = 50% |

| Other | 6 | 0.91 | 0.78, 1.05 | P = 0.19 | P = 0.01; I2 = 62% |

| Geographical region | |||||

| Asia | 9 | 0.89 | 0.85, 0.92 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.18; I2 = 26% |

| Non-Asia | 4 | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | P = 0.09 | P = 0.44; I2 = 0% |

| Sample size | |||||

| <1,000 | 7 | 0.88 | 0.84, 0.93 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.22; I2 = 25% |

| >1,000 | 6 | 0.95 | 0.91, 1.00 | P = 0.04 | P = 0.03; I2 = 52% |

| Exposure assessment | |||||

| FFQ | 2 | 0.88 | 0.49, 1.61 | P = 0.69 | P = 0.01; I2 = 84% |

| 24 h or 3 days recall | 10 | 0.89 | 0.86, 0.93 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.27; I2 = 17% |

| Study quality | |||||

| High-quality | 10 | 0.94 | 0.89, 0.99 | P = 0.02 | P = 0.01; I2 = 52% |

| Low-quality | 3 | 0.89 | 0.84, 0.94 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.82; I2 = 0% |

| Adjustment of BMI | |||||

| Adjusted | 6 | 0.91 | 0.85, 0.97 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.04; I2 = 50% |

| Unadjusted | 7 | 0.94 | 0.90, 0.99 | P = 0.03 | P = 0.02; I2 = 56% |

| Adjustment of physical activity | |||||

| Adjusted | 8 | 0.90 | 0.80, 1.02 | P = 0.09 | P = 0.07; I2 = 41% |

| Unadjusted | 5 | 0.94 | 0.89, 0.98 | P = 0.007 | P = 0.004; I2 = 69% |

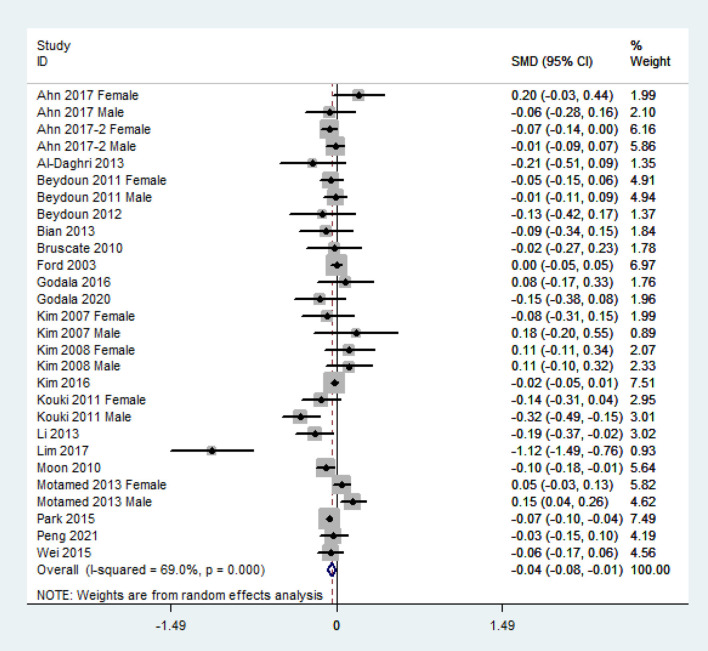

SMD of the Dietary Vitamin C Level for MetS vs. Control Subjects

The overall combined SMD showed that the dietary vitamin C level in MetS was lower than that in control subjects (SMD = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.08 to −0.01; P = 0.024) (Figure 3). A substantial level of heterogeneity was obtained among the various studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 69.0%). No evidence of publication bias existed according to Begg's rank-correlation test (P = 0.314). The results of the subgroup analysis are presented in Table 2. The above findings were confirmed in NCEP ATP III (SMD = −0.06, 95% CI: −0.11 to −0.01; P = 0.01), >1,000 sample size (SMD = −0.03, 95%CI: −0.07 to 0.00; P = 0.05), 24-h or 3 days recall (SMD = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.08 to 0.00; P = 0.05), and high-quality (SMD = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.07 to −0.01; P = 0.02) studies.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of meta-analysis. SMD of dietary vitamin C level for MetS vs. control subjects.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis for standard mean difference (SMD) of dietary vitamin C level in MetS vs. control subjects.

| Stratification | Number of studies | Pooled SMD | 95% CI | P-value | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 21 | −0.04 | −0.08, −0.01 | P = 0.02 | P < 0.001; I2 = 69% |

| Diagnostic criteria of MetS | |||||

| NCEP ATP III | 13 | −0.06 | −0.11, −0.01 | P = 0.01 | P < 0.001; I2 = 72% |

| Other | 8 | −0.01 | −0.03, 0.02 | P = 0.65 | P = 0.07; I2 = 45% |

| Geographical region | |||||

| Asia | 14 | −0.03 | −0.08, 0.01 | P = 0.16 | P < 0.001; I2 = 74% |

| Non-Asia | 7 | −0.07 | −0.14, 0.00 | P = 0.06 | P = 0.04; I2 = 51% |

| Sample size | |||||

| <1,000 | 11 | −0.07 | −0.19, 0.05 | P = 0.23 | P < 0.001; I2 = 73% |

| >1,000 | 10 | −0.03 | −0.07, 0.00 | P = 0.05 | P < 0.001; I2 = 66% |

| Exposure assessment | |||||

| FFQ | 3 | 0.00 | −0.04, 0.04 | P = 0.95 | P = 0.40; I2 = 0% |

| 24 h or 3 days recall | 17 | −0.04 | −0.08, 0.00 | P = 0.05 | P < 0.001; I2 = 69% |

| Study quality | |||||

| High-quality | 16 | −0.04 | −0.07, −0.01 | P = 0.02 | P < 0.001; I2 = 57% |

| Low-quality | 5 | −0.11 | −0.36, 0.13 | P = 0.38 | P < 0.001; I2 = 87% |

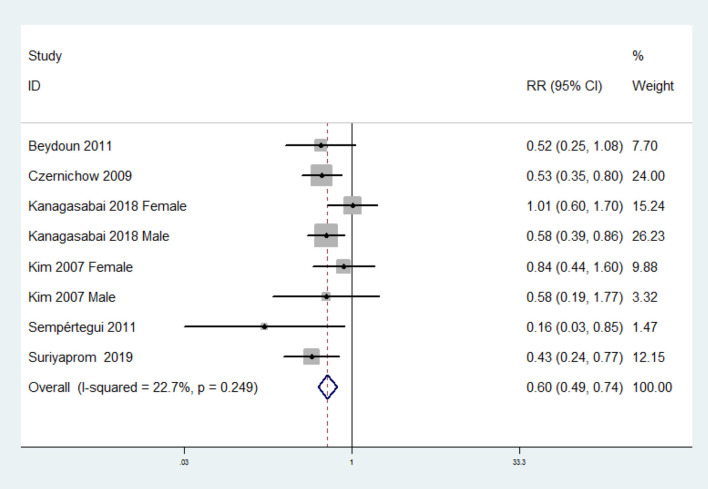

RR of MetS for the Highest vs. Lowest Circulating Vitamin C Category

The overall multivariable-adjusted RR demonstrated that the circulating vitamin C level was negatively associated with MetS (RR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.49 to 0.74; P < 0.001) (Figure 4). No substantial level of heterogeneity was obtained among various studies (P = 0.249, I2 = 22.7%). No evidence of publication bias existed according to Begg's rank-correlation test (P = 0.536). The results of subgroup analysis were presented in Table 3. The above findings were confirmed in NCEP ATP III (RR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.42 to 0.72; P < 0.001) studies.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of meta-analysis. Overall multi-variable adjusted RR of MetS for the highest vs. lowest category of circulating vitamin C level.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of MetS for the highest vs. lowest circulating vitamin C level category.

| Stratification | Number of studies | Pooled RR | 95% CI | ps-value | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 6 | 0.60 | 0.49, 0.74 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.25; I2 = 23% |

| Study design | |||||

| Crosssectional | 5 | 0.63 | 0.50, 0.79 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.20; I2 = 30% |

| Cohort | 1 | 0.53 | 0.35, 0.80 | / | / |

| Diagnostic criteria of MetS | |||||

| NCEP ATP III | 4 | 0.55 | 0.42, 0.72 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.66; I2 = 0% |

| Other | 2 | 0.63 | 0.33, 1.19 | P = 0.15 | P = 0.06; I2 = 65% |

| Geographical region | |||||

| Asia | 2 | 0.58 | 0.39, 0.87 | P = 0.008 | P = 0.32; I2 = 12% |

| Non-Asia | 4 | 0.61 | 0.48, 0.77 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.15; I2 = 41% |

| Sample size | |||||

| <1,000 | 3 | 0.54 | 0.37, 0.80 | P = 0.002 | P = 0.22; I2 = 32% |

| >1,000 | 3 | 0.62 | 0.49, 0.79 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.24; I2 = 29% |

| Study quality | |||||

| High-quality | 5 | 0.63 | 0.50, 0.79 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.20; I2 = 30% |

| Low-quality | 1 | 0.53 | 0.35, 0.80 | / | / |

| Adjustment of BMI | |||||

| Adjusted | 3 | 0.66 | 0.51, 0.84 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.23; I2 = 29% |

| Unadjusted | 3 | 0.50 | 0.35, 0.71 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.39; I2 = 0% |

| Adjustment of physical activity | |||||

| Adjusted | 2 | 0.60 | 0.43, 0.84 | P = 0.003 | P = 0.50; I2 = 0% |

| Unadjusted | 4 | 0.60 | 0.46, 0.77 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.10; I2 = 48% |

SMD of the Circulating Vitamin C Level for MetS vs. Control Subjects

The overall combined SMD showed that the circulating vitamin C level in MetS was lower than that in control subjects (SMD = −0.82, 95% CI: −1.24 to −0.40; P < 0.001) (Figure 5). A substantial level of heterogeneity was obtained among the various studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 98.3%). No evidence of publication bias existed according to Begg's rank-correlation test (P = 0.076). The results of subgroup analysis are presented in Table 4.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of meta-analysis. SMD of circulating vitamin C level for MetS vs. control subjects.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis for SMD of circulating vitamin C level in MetS vs. control subjects.

| Stratification | Number of studies | Pooled SMD | 95% CI | p-value | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 8 | −0.82 | −1.24, −0.40 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001; I2 = 98% |

| Diagnostic criteria of MetSNCEP ATP III | 5 | −0.40 | −0.68, −0.11 | P = 0.006 | P < 0.001; I2 = 96% |

| Other | 3 | −1.62 | −2.59, −0.66 | P = 0.001 | P < 0.001; I2 = 96% |

| Geographical region | |||||

| US | 3 | −0.12 | −0.16, −0.07 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.18; I2 = 39% |

| Non-US | 5 | −1.31 | −2.31, −0.31 | P = 0.01 | P < 0.001; I2 = 99% |

| Sample size | |||||

| <1,000 | 5 | −1.31 | −2.31, −0.31 | P = 0.23 | P < 0.001; I2 = 99% |

| >1,000 | 3 | −0.12 | −0.16, −0.07 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.18; I2 = 39% |

| Study quality | |||||

| High-quality | 6 | −0.46 | −0.80, −0.13 | P = 0.007 | P < 0.001; I2 = 97% |

| Low-quality | 2 | −2.08 | −2.31, −1.84 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.75; I2 = 0% |

Discussion

In the present meta-analysis, a total of 28 observational studies were identified, and the pooled analysis showed that both the dietary and the circulating vitamin C level were inversely associated with MetS.

Since oxidative stress and inflammation play a significant role in the pathophysiology of MetS (42), the underlying mechanism behind the negative association between vitamin C and MetS can be listed as follows: on the one hand, vitamin C serves as a strong antioxidant, which prevents other compounds from being oxidized (42). Vitamin C can donate electrons, scavenge harmful free radicals, and leave the ascorbyl radical (relatively stable and unreactive) (43, 44). Indeed, antioxidants could lower blood pressure by oxidation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (45). Several meta-analysis studies have also indicated a potential beneficial effect of vitamins antioxidant on type 2 diabetes (46, 47). A higher intake of antioxidant vitamins and serum total antioxidant status from antioxidant supplementation were associated with a decreased waist circumference and low-density lipoprotein to high-density lipoprotein–cholesterol ratio (40). On the other hand, the neutrophil is an important regulatory marker for acute and chronic inflammation. The hyperplasia and hypertrophy of adipose tissue, the main source of various inflammatory mediators, is closely associated with the MetS-associated inflammation (48). The neutrophil chemotaxis to adipose tissue (with subsequent phagocytosis of microbes and clearance by macrophages) could therefore reduce inflammation. Indeed, vitamin C has the potential to improve neutrophil chemotaxis in both human and animal studies (49–51). In addition, patients with impaired neutrophil bacterial phagocytosis can be significantly improved by vitamin C supplementation (long-lasting clinical improvement) (52). Importantly, vitamin C-deficient neutrophils were not phagocytosed by macrophages in vitro and persisted at inflammatory loci in vivo (53). Taken together, vitamin C is able to alleviate the inflammatory response by influencing neutrophil chemotaxis in response to inflammatory mediators, enhancing phagocytosis of microbes by neutrophils and neutrophil clearance by macrophages (52).

The effect of vitamin C on MetS has been extensively investigated in experimental animal and clinical studies. Bilbis et al. found that 4-week supplementation of vitamin C could decrease the weight gain, blood pressure, glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in a salt-loaded animal model (54), indicating a strong biological effect of vitamin C on the circulating profile in MetS. Moreover, unlike animals, humans are dependent upon dietary vitamin C due to mutations in l-gulono-γ-lactone oxidase (Gulo, the final enzyme for vitamin C biosynthesis). The induction of vitamin C deficiency in Gulo-/- mice was associated with a phenotype characterized by insulin resistance, weight gain, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis (7). Indeed, this animal model was humanized and necessarily reflected the issue. Importantly, Abd indicated that the combination of vitamin C and l-methionine had the most beneficial effect on hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, abnormal coagulation indices, and oxidative stress in the alloxan-induced diabetes model. Asynergistic biological effects may exist between vitamin C and others, which indicated that the combination therapy strategy for vitamin C is promising (55). With regard to the clinical evidence, Farag et al. found that vitamin C supplementation could result in a significant reduction in BMI, and the combination of physical activities [exercise alone was reported to be beneficial to MetS (56, 57)] and vitamin C supplements may further improve systolic blood pressure and serum levels of total cholesterol in MetS patients (58, 59). Taken together, the current experimental and clinical evidence strongly supports the potential beneficial effect of vitamin C on MetS. Moreover, the vitamin C combination therapy (with l-methionine or exercise) seems to be a promising strategy for the management of MetS, which might be recommended clinically.

Interestingly, the inverse relationship between dietary vitamin C level and MetS was only obtained in crosssectional studies. However, the number of cohort studies is rather small (only two), which may inevitably reduce the reliability. Although vitamin C may be beneficial to the components or complications of MetS (e.g., decreased blood pressure, glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, etc.), it is not necessarily a reflection of MetS prevention. One cohort study combined vitamin C and B1 as a whole, and the effect of vitamin B1 could not be specified (27). Interestingly, the inconsistent result with regard to diagnostic criteria of MetS and exposure assessment was acquired. It was speculated that NCEP ATP III criteria and recall method seems to be more precise and suitable for vitamin C evaluation. With regard to the SMD analysis for the dietary vitamin C levels, the findings disappeared in small sample-sized (<1,000) studies. Indeed, large sample-sized studies may be more reliable to address the issues. Importantly, no study has specified the dietary season variation, and our results might be influenced by the seasonal variability of vitamin C levels. Taken together, more well-designed prospective cohort studies are still needed.

Our study has several strengthens. To begin with, this is the first meta-analysis of observational studies on the associations of dietary and circulating vitamin C levels with MetS. In addition, the included studies are analyzed based on the adjusted results and large samples. Finally, our findings are consistent with the current corresponding experimental and clinical studies. Above all, our study might provide helpful information to better consider the effect of vitamin C on MetS.

On the other hand, we should also acknowledge the limitations of this study. (1) The substantial level of heterogeneity might have distorted the reliability of our results. (2) Due to the limited relevant literature, only three prospective cohort studies were identified totally (causal relationships could not be obtained). (3) The classification of exposure may vary greatly among individuals. (4) The selection of adjusted factors and definition of MetS was not uniform. (5) One included study has combined the effect estimates for vitamin C and vitamin B1 as a whole (27), some issues could not be addressed. (6) The seasonal variation in vitamin C level cannot be considered in this study. These limitations may weaken the significance of our study.

Conclusions

Current evidence suggests that both dietary and circulating vitamin C levels are inversely associated with MetS. However, due to the limitation of the available evidence, more well-designed prospective studies are still needed.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: PubMed, Web of Science, Embase.

Author Contributions

YZ, HG, and JD conceived the idea, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted this meta-analysis. YZ and JD selected retrieved relevant papers. QL and YL assessed each study. YZ was the guarantors of the overall content. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82102581), the National Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2021M693562), the Provincial Outstanding Postdoctoral Innovative Talents Program of Hunan (2021RC2020), the Young Investigator Grant of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (2020Q14), and the FuQing Postdoc Program of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (176).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2021.728880/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Zhang DZ. Relationship between serum zinc level and metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Coll Nutr. (2018) 37:708–15. 10.1080/07315724.2018.1463876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Athyros VG, Ganotakis ES, Elisaf M, Mikhailidis DP. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome using the National Cholesterol Educational Program and International Diabetes Federation definitions. Curr Med Res Opin. (2005) 21:1157–9. 10.1185/030079905X53333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Zhang DZ. Relationship between nut consumption and metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Coll Nutr. (2019) 38:499–505. 10.1080/07315724.2018.1561341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Zhang DZ. Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with metabolic syndrome. A meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. (2018) 21:1693–703. 10.1017/S1368980018000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou C, Na L, Shan R, Cheng Y, Li Y, Wu X, et al. Dietary vitamin C intake reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes in chinese adults: HOMA-IR and T-AOC as potential mediators. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0163571. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan Y, Dai P, Wang H. Effects of vitamin C supplementation on essential hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2020) 99:e19274. 10.1097/MD.0000000000019274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Natarajan R, Fisher BJ, Kraskauskas D, Ghosh S, Fowler AA. Persistent vitamin C deficiency promotes insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in mice. Diabetes. (2017) 66:A490. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Giles WH, Brown DW. The metabolic syndrome and antioxidant concentrations: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes. (2003) 52:2346–52. 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MH, Lee HS, Park HJ, Kim WY. Risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome in Korean elderly. Ann Nutr Metab. (2007) 51:533–40. 10.1159/000112977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim WY, Kim JE, Choi YJ, Huh KB. Nutritional risk and metabolic syndrome in Korean type 2 diabetes mellitus. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. (2008) 17(Suppl. 1):47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon HK. Assessment of nutrient intake for middle aged with and without metabolic syndrome using 2005 and 2007 Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey. J. Nutr. Health. (2010) 43:69–78. 10.4163/kjn.2010.43.1.69 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beydoun MA, Shroff MR, Chen X, Beydoun HA, Wang Y, Zonderman AB. Serum antioxidant status is associated with metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults in recent national surveys. J Nutr. (2011) 141:903–13. 10.3945/jn.110.136580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kouki R, Schwab U, Hassinen M, Komulainen P, Heikkilä H, Lakka TA, et al. Food consumption, nutrient intake and the risk of having metabolic syndrome: the DR's EXTRA Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2011) 65:368–77. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beydoun MA, Canas JA, Beydoun HA, Chen X, Shroff MR, Zonderman AB. Serum antioxidant concentrations and metabolic syndrome are associated among U.S. adolescents in recent national surveys. J Nutr. (2012) 142:1693–704. 10.3945/jn.112.160416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira Otto MC, Alonso A, Lee DH, Delclos GL, Bertoni AG, Jiang R, et al. Dietary intakes of zinc and heme iron from red meat, but not from other sources, are associated with greater risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. J Nutr. (2012) 142:526–33. 10.3945/jn.111.149781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Daghri NM, Khan N, Alkharfy KM, Al-Attas OS, Alokail MS, Alfawaz HA, et al. Selected dietary nutrients and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in adult males and females in Saudi Arabia: a pilot study. Nutrients. (2013) 5:4587–604. 10.3390/nu5114587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bian S, Gao Y, Zhang M, Wang X, Liu W, Zhang D, et al. Dietary nutrient intake and metabolic syndrome risk in Chinese adults: a case-control study. Nutr J. (2013) 12:106. 10.1186/1475-2891-12-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Guo H, Wu M, Liu M. Serum and dietary antioxidant status is associated with lower prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in a study in Shanghai, China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. (2013) 22:60–8. 10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.1.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S, Ham JO, Lee BK. Effects of total vitamin A, vitamin C, and fruit intake on risk for metabolic syndrome in Korean women and men. Nutrition. (2015) 31:111–8. 10.1016/j.nut.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei J, Zeng C, Gong Q, Li X, Lei G, Yang T. Associations between dietary antioxidant intake and metabolic syndrome. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0130876. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godala MM, Materek-Kuśmierkiewicz I, Moczulski D, Rutkowski M, Szatko F, Gaszyńska E, et al. Lower plasma levels of antioxidant vitamins in patients with metabolic syndrome: a case control study. Adv Clin Exp Med. (2016) 25:689–700. 10.17219/acem/41049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, Choi YH. Physical activity, dietary vitamin C, and metabolic syndrome in the Korean adults: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008 to 2012. Public Health. (2016) 135:30–7. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn S, Jun S, Kang M, Shin S, Wie G, Baik HW, et al. Association between intake of antioxidant vitamins and metabolic syndrome risk among Korean adults. J Nutr Health. (2017) 50:313–24. 10.4163/jnh.2017.50.4.313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim HS, Shin EJ, Yeom JW, Park YH, Kim SK. Association between nutrient intake and metabolic syndrome in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Nutr Res. (2017) 6:38–46. 10.7762/cnr.2017.6.1.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahn J, Kim NS, Lee BK, Park S. Association between intake of antioxidant vitamins and metabolic syndrome prevalence among Korean adults. Curr Dev Nutr. (2019) 3(Suppl. 1):19. 10.1093/cdn/nzz044.P24-001-19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godala M, Gaszyńska E, Moczulski D, Materek-Kuśmierkiewicz I, Krzyzak M. An assessment of the antioxidant vitamins concentration in people with metabolicsyndrome working in agriculture. Med Pr. (2020) 23:128769. 10.13075/mp.5893.01046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng Z, Wang Y, Huang X, Zhu Q, Zhao Y, Xie H, et al. Dietary vitamin intake and risk of metabolic syndrome among centenarians in China. Exp Ther Med. (2021) 21:105. 10.3892/etm.2020.9537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sempértegui F, Estrella B, Tucker KL, Hamer DH, Narvaez X, Sempértegui M, et al. Metabolic syndrome in the elderly living in marginal peri-urban communities in Quito, Ecuador. Public Health Nutr. (2011) 14:758–67. 10.1017/S1368980010002636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Czernichow S, Vergnaud AC, Galan P, Arnaud J, Favier A, Faure H, et al. Effects of long-term antioxidant supplementation and association of serum antioxidant concentrations with risk of metabolic syndrome in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. (2009) 90:329–35. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odum EP, Wakwe VC. Plasma concentrations of water-soluble vitamins in metabolic syndrome subjects. Niger J Clin Pract. (2012) 15:442–7. 10.4103/1119-3077.104522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suriyaprom K, Kaewprasert S, Putpadungwipon P, Namjuntra P, Klongthalay S. Association of antioxidant status and inflammatory markers with metabolic syndrome in Thais. J Health Popul Nutr. (2019) 38:1. 10.1186/s41043-018-0158-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanagasabai T, Alkhalaqi K, Churilla JR, Ardern CI. The association between metabolic syndrome and serum concentrations of micronutrients, inflammation, and oxidative stress outside of the clinical reference ranges: a cross-sectional study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. (2019) 17:29–36. 10.1089/met.2018.0080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motamed S, Ebrahimi M, Safarian M, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Mouhebati M, Azarpazhouh M, et al. Micronutrient intake and the presence of the metabolic syndrome. N Am J Med Sci. (2013) 5:377–85. 10.4103/1947-2714.114171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruscato NM, Vieira J, Nascimento N, Canto M, Stobbe J, Gottlieb MG, et al. Dietary intake is not associated to the metabolic syndrome in elderly women. N Am J Med Sci. (2010) 2:182–8. 10.4297/najms.2010.2182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn J, Kim NS, Lee BK, Park S. Carbohydrate intake exhibited a positive association with the risk of metabolic syndrome in both semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires and 24-hour recall in women. J Korean Med Sci. (2017) 32:1474–83. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.9.1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuhara H, Steinmaus C, Cohen S, Corley D, Tei Y, Buffler P. Is diabetesmellitus an independent risk factor for colon cancer and rectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol. (2011) 106:1911–22. 10.1038/ajg.2011.301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Begg CB, Mazumdar M, et al. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. (1994) 50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godala M, Materek-Kuśmierkiewicz I, Moczulski D, Szatko F, Gaszyńska E, Tokarski S, et al. Should antioxidant vitamin supplementation be applied in patients with metabolic syndrome? A case-control study. Menopause Rev. (2016) 15:32–38. 10.5114/pm.2016.58771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim S, Song Y, Lee JE, Jun S, Shin S, Wie GA, et al. Total antioxidant capacity from dietary supplement decreases the likelihood of having metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Nutrients. (2017) 9:1055. 10.3390/nu9101055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Godala M, Materek-Kuśmierkiewicz I, Moczulski D, Rutkowski M, Szatko F, Gaszyńska E, et al. The risk of plasma vitamin A, C, E and D deficiency in patients with metabolic syndrome: A case-control study. Adv Clin Exp Med. (2017) 26:581–6. 10.17219/acem/62453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong SK, Chin KY, Ima-Nirwana S. Vitamin C: A review on its role in the management of metabolic syndrome. Int J Med Sci. (2020) 17:1625–38. 10.7150/ijms.47103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Padayatty SJ, Katz A, Wang Y, Eck P, Kwon O, Lee JH, et al. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation ofits role in disease prevention. J Am Coll Nutr. (2003) 22:18–35. 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pehlivan FE. Vitamin C: An antioxidant agent. Vitamin C. (2017) 2017:23–35. 10.5772/intechopen.69660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prysyazhna O, Wolhuter K, Switzer C, Santos C, Yang X, Lynham S, et al. Blood pressure-lowering by the antioxidant resveratrol is counterintuitively mediated by oxidation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Circulation. (2019) 140:126–37. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balbi ME, Tonin FS, Mendes AM, Borba HH, Wiens A, Fernandez-Llimos F, et al. Antioxidant effects of vitamins in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetol Metab Syndr. (2018) 10:18. 10.1186/s13098-018-0318-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montero D, Walther G, Stehouwer C, Houben A, Beckman J, Vinet A, et al. Effect of antioxidant vitamin supplementation on endothelial function in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. (2014) 15:107–16. 10.1111/obr.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong SK, Chin KY, Suhaimi FH, Ahmad F, Ima-Nirwana S. The relationship between metabolic syndrome and osteoporosis: a review. Nutrients. (2016) 8:347. 10.3390/nu8060347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallin J, Elin R, Hubert R, Fauci A, Kaliner M, Wolff S. Efficacy of ascorbic acid in Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS): studies in humans and mice. Blood. (1979) 53:226–34. 10.1182/blood.V53.2.226.bloodjournal532226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boxer LA, Watanabe AM, Rister M, Besch J, Allen J, Baehner RL. Correction of leukocyte function in Chediak-Higashi syndrome by ascorbate. N Engl J Med. (1976) 295:1041–5. 10.1056/NEJM197611042951904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yegin O, Sanal O, Yeralan O, Gürgey A, Berkel AI. Defective lymphocyte locomotion in Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Am J Dis Child. (1983) 137:771–3. 10.1001/archpedi.1983.02140340051014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carr AC Maggini S. Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients. (2017) 9:1211. 10.3390/nu9111211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vissers C, Wilkie P. Ascorbate deficiency results in impaired neutrophil apoptosis and clearance and is associated with up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J Leukoc Biol. (2007) 81:1236–44. 10.1189/jlb.0806541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bilbis LS, Muhammad SA, Saidu Y, Adamu Y. Effect of vitamins A, C, and E supplementation in the treatment of metabolic syndrome in albino rats. Biochem Res Int. (2012) 2012:678582. 10.1155/2012/678582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abd EA, Barakat A, Shehata SM. Influence of vitamin C or/and L-methionine on hyperglycaemia, hyperlipidaemia and hematological alterations in alloxan-induced diabetes in rats. Prog Nutr. (2018) 20:270–8. 10.23751/pn.v20i2-S.5418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yousefabadi H, Niyazi A, Alaee S, Fathi M, Rahimi G. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise on metabolic syndrome patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Res Nurs. (2021) 23:280–92. 10.1177/1099800420958068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ostman C, Smart NA, Morcos D, Duller A, Ridley W, Jewiss D. The effect of exercise training on clinical outcomes in patients with the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2017) 16:110. 10.1186/s12933-017-0590-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farag HAM, Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Muhammad BA, Esmaillzadeh A, Bilbeisi AHE. Comparative effects of vitamin D and vitamin C supplementations with and without endurance physical activity on metabolic syndrome patients: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetol Metab Syndr. (2018) 10:80. 10.1186/s13098-018-0384-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farag HAM, Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Muhammad BA, Esmaillzadeh A, El Bilbeisi AH. Effects of vitamin C supplementation with and without endurance physical activity on components of metabolic syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. Experi. (2019) 26:23–33. 10.1016/j.yclnex.2019.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: PubMed, Web of Science, Embase.