Abstract

Recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vectors are considered promising tools for gene therapy directed at the liver. Whereas rAAV is thought to be an episomal vector, its single-stranded DNA genome is prone to intra- and inter-molecular recombination leading to rearrangements and integration into the host cell genome. Here, we ascertained the integration frequency of rAAV in human hepatocytes transduced either ex vivo or in vivo and subsequently expanded in a mouse model of xenogeneic liver regeneration. Chromosomal rAAV integration events and vector integrity were determined using the capture-PacBio sequencing approach, a long-read next-generation sequencing method that has not previously been used for this purpose. Chromosomal integrations were found at a surprisingly high frequency of 1%–3% both in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, most of the inserted rAAV sequences were heavily rearranged and were accompanied by deletions of the host genomic sequence at the integration site.

Keywords: rAAV, genotoxicity, random integration, capture sequencing, FRGN

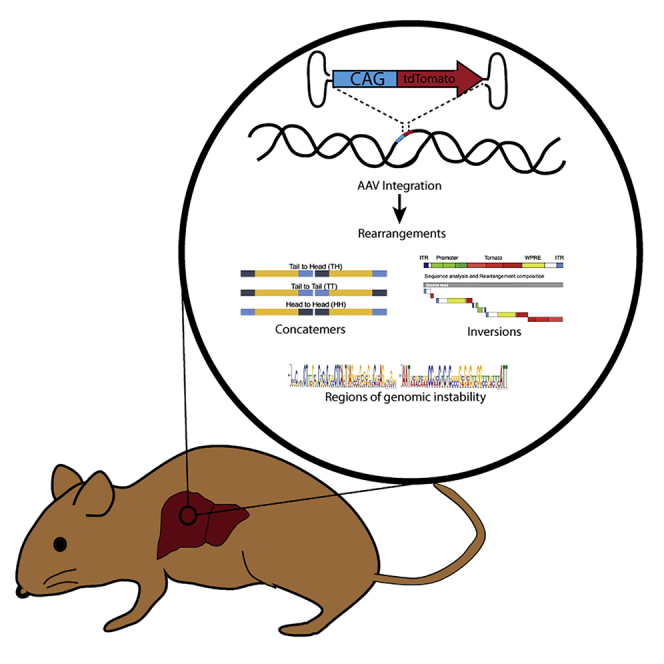

Graphical abstract

In a humanized mouse model of liver regeneration, rAAV chromosomal integrations occur at a surprisingly high frequency and are heavily rearranged and concatenated. Rearrangements were more prominent when hepatocytes were transduced ex vivo at a high dose, thus raising concerns regarding the safety of dosages used in rAAV gene therapy.

Introduction

Gene therapy is a growing field, and the number of gene therapy clinical trials is increasing rapidly.1,2 Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV), a promising gene-therapy vector, is enjoying significant success in the clinic. Key advantages of rAAV include the ability to transduce both dividing and quiescent cells, robust in vivo transduction efficiency, long-term transgene expression in quiescent cells, tropism for specific tissues and cell types, relatively low immunogenicity, and a history of clinical safety.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 rAAV remains mostly episomal in transduced cells, however it can integrate in the cell host genome at low frequency.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Although AAV genomes can persist as episomes for a prolonged time, especially in non-dividing cells, integrated viral genomes have also been found. Wild-type (WT) rAAV is unique in its ability to integrate in a site-specific manner in human chromosome 19 at the AAVS1 site, as well as undergo homologous recombination when large regions of homology exist between the viral and host genomes.21,22

Although previous reports describe low rAAV integration frequencies (0.1%–0.5%), thousands of integration sites were identified scattered throughout the genome.16,23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 Some of these earlier studies utilized AAV shuttle vectors in both in vitro and in vivo models to identify integration sites and study the mechanism of integration. Using these approaches, mostly single-copy viral genomes were found distributed throughout the host chromosomes in in vitro models via a non-homologous recombination mechanism.26 Further, although WTAAV has a preference for the AAVS1 site, this locus is not a hotspot for rAAV integrations.27 Although rAAV can integrate within a 22-Mb region of chromosome 19, WTAAV integrations were predominantly found within a specific 1-kb region of AAVS1.28 In a subsequent study, rAAV was found to primarily integrate in host genomes as head-to-tail concatemers. Head-to-head and tail-to-tail concatemeric integrations were found at a much lower frequency.29 rAAV integrations appear to occur at high frequency in genomic sites with palindromic sequences (arm length of ≥20 bp), CpG islands, the first kilobase of genes, and with only a slight preference for transcribed sequences.24,25,31 Other reported hotspots of rAAV integration included ribosomal DNA repeats, gene regulatory sequences, transcriptional start sites (TSSs), active genes, and regulatory RNA regions.25,30, 31, 32,35 Vector integrations often contained ITR (inverted terminal repeat) deletions, vector rearrangements, and chromosomal rearrangements and deletions.28, 29, 30 Whereas most of the evidence to date suggests that rAAV is safe, a number of rodent studies have shown that when integrations occur, they can lead to gain- or loss-of-function mutations, resulting in oncogenesis.5,11,16,17,32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52

To our knowledge, there are no studies that directly address the frequency with which rAAV integrates in human hepatocytes. Here, the humanized liver mouse model developed by our lab was utilized to assess the frequency of integration in human hepatocytes, and capture sequencing was applied to assess the nature of the rAAV integrations. Previous studies utilized shuttle vectors, linear amplification-mediated (LAM)-PCR, or ligation-mediated (LM)-PCR. A major limitation of the shuttle vector system is that it only captures integration events where the origin of replication and selection marker are intact; all other integration events are missed, and it is not high throughput. LM/LAM-PCR also suffers from a bias for integration events with ITRs. Multiplex LAM-PCR overcomes this bias, but since it is coupled with short-read Illumina sequencing, it is still not ideal for exploring the concatemeric nature of AAV integrations.16 The capture sequencing approach used here is coupled with long reads of PacBio SMRT (single molecule, real-time) sequencing, which not only allows for unambiguous identification of integration sites but also for concatemer visualization. Using our humanized liver mouse model and capture sequencing approach, we show a surprisingly high frequency of rAAV integration in human hepatocytes and show that most of integrated AAV genomes have undergone rearrangements, especially when transduced ex vivo.

Results

Ex vivo rAAV transduction of human hepatocytes

A humanized liver mouse model was used to interrogate the AAV integration frequency in human hepatocytes. In this system, primary human hepatocytes are transplanted into immune-deficient mice deficient in fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (Fah).53 The selective growth advantage of normal hepatocytes in this model results in repopulation of >70% of the recipient liver with human cells. Importantly, liver repopulation involves many rounds of cell division, which leads to the elimination of episomal rAAV genomes. Two distinct approaches to transduce human hepatocytes with rAAV were used (Figure 1): an ex vivo model and an in vivo model. An rAAV transduction time-course was initially performed, and tdTomato-positive hepatocytes could be seen in vitro as early as 24 h post-transduction, and by 72 h, a majority of the hepatocytes were expressing the reporter (Figure 2A). Two different serotypes were tested, the DJ and LK03 serotypes, and both transduced equally well (Figures 3B and 3C). All subsequent ex vivo transductions for transplantations were performed using the DJ serotype. tdTomato-positive hepatocytes could be detected in humanized livers as shown in Figures 2D and 2E, even after undergoing numerous rounds of division. Since AAV episomes are lost during cellular division, only integrated genomes can remain.54 To estimate the frequency of tdTomato-positive hepatocytes after in vitro transduction, hepatocytes were isolated by perfusion and analyzed by flow cytometry. To distinguish between human and mouse hepatocytes, cells were labeled with OC2-2F8 and OC2-2G9 antibodies (made in-house), which label mouse hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells (NPCs).

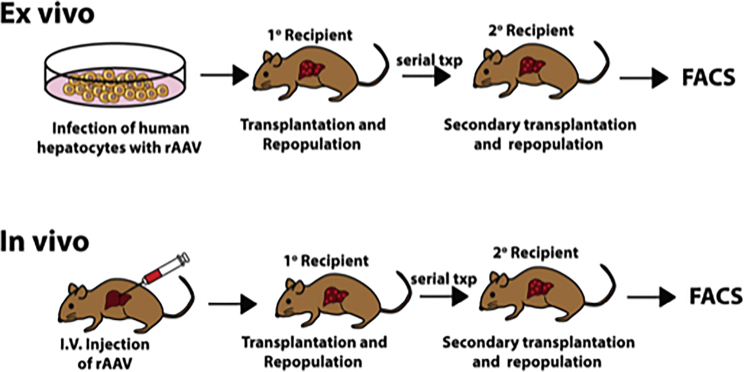

Figure 1.

Ex vivo and in vivo model for interrogating AAV integration frequency in human hepatocytes

In the ex vivo approach, human hepatocytes were transduced with AAV-CAG-tdTomato, then transplanted into FRGN mice. Following humanization, hepatocytes were harvested and serially transplanted. In the in vivo approach, highly liver humanized mice were infected with AAV. 2 weeks after infection, hepatocytes were harvested and serially transplanted.

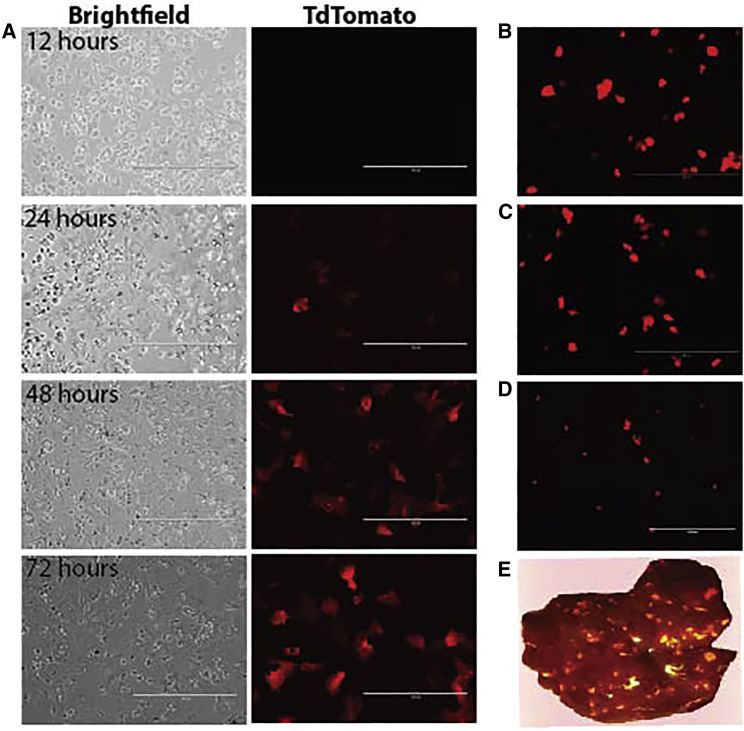

Figure 2.

Ex vivo transduction of human hepatocytes with rAAV-CAG-tdTomato

(A) Hepatocytes at 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-AAV transduction (DJ serotype). (B) Hepatocytes at 24 h post-AAV-tdTomato infection (DJ serotype). (C) Hepatocytes at 24 h post-AAV-tdTomato infection (LK03 serotype). (D) Hepatocytes recovered from mouse liver repopulated with AAVDJ-CAG-tdTomato-infected human hepatocytes, imaged 24 h after perfusion and plating. (E) Mouse liver repopulated with human hepatocytes infected with AAV-tdTomato 4 months prior, shown illuminated with RFP (red fluorescent protein) flashlight.

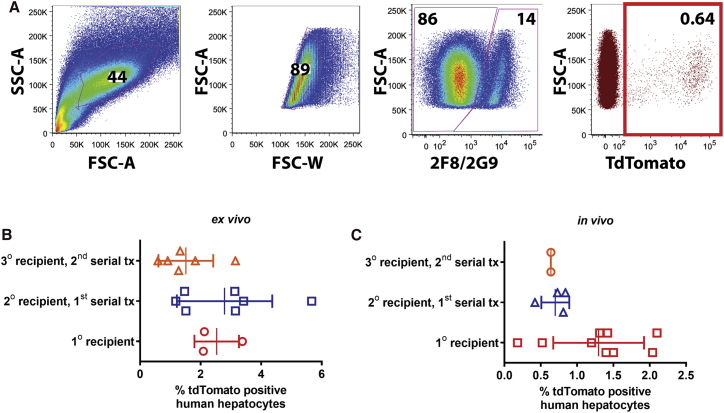

Figure 3.

AAV genome persists in 0.6% to 2.8% of human hepatocytes in a liver injury mouse model

(A) Representative flow analysis. Hepatocytes perfused from humanized mice were stained with OC2-CF8 and OC2-2G9 antibodies, which have affinity for mouse cells but not human hepatocytes. Using this gating strategy, human hepatocytes were analyzed for tomato reporter gene expression. (B and C) AAV integration frequency in human hepatocytes transduced (B) ex vivo or (C) in vivo. Data presented as mean ± SD. In both approaches, there is a decrease in tdTomato-positive hepatocytes with serial transplantation, but the variance was such that the difference is not statistically significant by one-way ANOVA.

In the ex vivo model, human hepatocytes were transduced with the AAV-CAG-tdTomato (DJ serotype) in tissue culture at a MOI of ∼100,000, and 24 h post-transduction, hepatocytes were transplanted into Fah (fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase)−/−/Rag2 (recombination activating 2)−/−/Il2rg(interleukin 2 receptor subunit gamma)−/−/Nod (non-obese diabetic)−/− (FRGN) mice. FRGN mice lacking Fah and also immune deficient are amenable to near-complete liver repopulation by xenotransplanted human hepatocytes.53 Once the mice were significantly humanized (human serum albumin levels > 1,000 μg/mL), human hepatocytes were serially transplanted into secondary FRGN recipients. This process eliminates episomal viral genomes by cell division, leaving only integrated genomes. Initially, 11 mice were transplanted with primary human hepatocytes transduced with AAVDJ-CAG-tdTomato and underwent a repeated cycle of liver damage by 2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclo-hexanedione (NTBC) withdrawal until high levels of human albumin could be detected. Hepatocytes were harvested from three mice that had human albumin levels ranging from 2,220 to 5,019 μg/mL (estimated humanization levels of 30%–80%). They were analyzed by flow and serially transplanted into secondary (n = 7 mice) and tertiary (n = 6 mice) recipients. 2.5% ± 0.43% of the isolated human hepatocytes from the primary recipient were tdTomato positive (Figure 3B). tdTomato-positive hepatocytes persisted after each round of serial transplantation, 2.8% ± 0.60% for secondary and 1.5% ± 0.37% for tertiary recipients.

In vivo transduction of human hepatocytes

To ascertain the integration frequency of rAAV in vivo (Figure 3C), highly humanized mice (albumin levels > 3,000 μg/mL) were injected with 1 × 1011 vector genome copies of rAAVDJ-CAG-tdTomato via the retro-orbital sinus. 2 weeks after the rAAV injection, human hepatocytes were harvested by collagenase perfusion and immediately serially transplanted into nine FRGNs without any intervening tissue culture. The primary FRGN transplant recipients underwent hepatocyte selection until high levels of human serum albumin were achieved. Six of the nine secondary recipients became highly repopulated (human albumin levels ranging between 3,500 and 8,650 μg/mL). These animals were sacrificed and the hepatocytes isolated. The frequency of reporter-expressing human hepatocytes was determined by flow cytometry to be 1.3% ± 0.32%. In addition, secondary and tertiary rounds of serial transplantation were performed from a subset of four and three repopulated mice, respectively. Upon humanization at each stage (human albumin levels ranging between 1,300 and 5,650 μg/mL), hepatocytes were isolated, and frequency of reporter expression was determined by flow cytometry to be 0.70% ± 0.096% (secondary) and 0.64% ± 0.0005% (tertiary). Through multiple rounds of serial transplantation of in vivo-transduced hepatocytes, reporter expression was not lost, confirming stable integration of the reporter. The frequency of reporter expression stabilized at approximately 0.7% (1/143 cells) following the secondary serial transplantation and hence demonstrates the in vivo integration frequency of rAAV.

rAAV integrates in the genome of ex vivo- and in vivo-transduced human hepatocytes

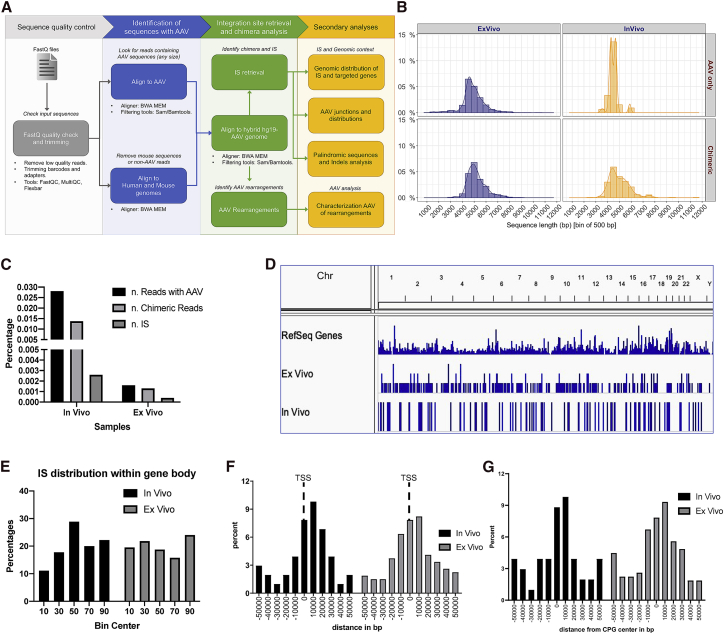

Livers of mice expressing human hepatocytes with stable tdTomato expression were perfused and purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from serially transplanted animals after either in vitro or in vivo transduction. Perfusing the liver results in a homogeneous suspension of cells, and if there was clonal expansion of hepatocytes, those clones would been separated into single cells. DNA was extracted from the sorted cells and was subjected to targeted capture to enrich for DNA molecules containing rAAV sequences and finally processed for PacBio sequencing. PacBio sequences were filtered for quality, aligned against the human and rAAV genomes (including plasmid sequences) to map integration sites, recombination events within rAAV and plasmid sequences (Figure 4A). After quality filtering, we obtained >10 million sequencing reads from the ex vivo and >23 million reads from in vivo samples (Table S2), both with an average length size of ∼5 kb (range 2−8 kb) (Figure 4B). rAAV sequences were found in ∼0.03% (n = 2,857) of the sequencing reads of the ex vivo samples and in ∼0.002% (n = 405) of the in vivo sequencing reads (Figure 4C). In one sample, we found a few plasmid sequences (n = 27), possibly arising from contaminants in the vector preparation. About 50% of the AAV-containing sequences of the ex vivo samples also contained the human genomic sequence flanking the integration site (n = 1,406), whereas for the in vivo samples, the frequency increased significantly up to ∼84% (n = 339, p < 0.001 by Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 4C). The reads containing only rAAV sequences in the in vivo datasets showed a narrow median length distribution around 4 kb, whereas the ex vivo datasets showed a broader fragment size distribution around a median of ∼4.5 kb, which may explain the higher frequency of these molecular forms in the latter dataset (Figure 4B). After collapsing all of the human/rAAV chimeric reads containing the same insertion sites, we identified 268 and 102 non-redundant integration sites in ex vivo and in vivo samples, respectively. The integration sites were distributed across the whole genome (Figures 4D and S1) and showed a preference to integrate within gene bodies (Figure 4E), TSSs (Figure 4F), and CpG islands (Figure 4G). Most genes were targeted only once, a few were found 2 or 3 times, and only SURF6 and ALB were hit 5 and 4 times, respectively (Table S2). No biases to target specific gene classes were observed upon Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT) software analysis (data not shown).

Figure 4.

rAAV genomic integration frequency and distribution profile in human hepatocytes

(A) Schematic workflow of integration site analysis and bioinformatics procedures for rearrangement characterization. (B) Distribution of raw-reads length per sample. In rows, the two groups are “Chimeric” (meaning reads containing AAV and also aligning to target genome) and “AAV only” (meaning reads with AAV sequence but no hit on target genome). (C) Summary of raw reads. Considering all raw reads, only a fraction contained AAV sequences (“n. Reads with AAV”), and within this subset, only a portion contained reads with a sequence from AAV and sequence from human genome (hg19), for this reason, called “chimeric reads.” From the latter subset, we identified unique IS (integration sites) “n. IS.” (D) Genome-wide distribution of integration sites. (E) Integration site distribution within gene bodies (normalized by gene size): each gene interval has been quantified from transcription start site (TSS) up to the end of its coding region, and this interval is considered as 100%, then normalized in bins of 10%. (F) Integration site distribution around TSSs and (G) CpG islands.

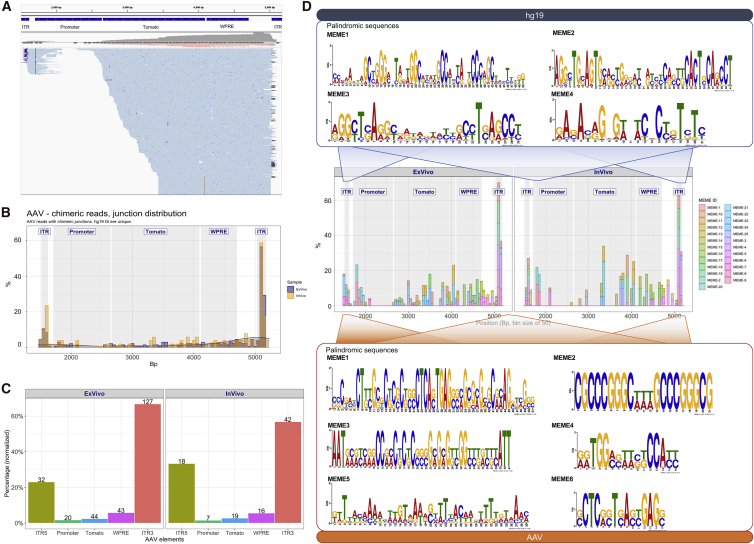

rAAV genomic integration in human hepatocytes is mediated by the interaction between vector- and human-degenerated palindromic sequences

We then investigated in more detail what regions and sequence characteristics of the rAAV genome were involved in integration events. ITRs, despite being relatively small (∼150 bp), were involved in ∼60% of all genomic integrations ex vivo and in vivo, whereas the relatively larger elements, tdTomato (∼1.5 kb) and WPRE (woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) posttranscriptional regulatory element) (∼600 bp), were involved in 16%–18% of integrations (Figures 5A−5C). Integration events involving the promoter region were poorly represented in our integration datasets (∼7%) and mainly involved the 5′ portion, whereas the downstream region was not represented. The lack of integration events in the promoter is explained by the lack of enrichment for this region, as capture probes for this highly CG-rich portion of the vector could not be used for selection before PacBio sequencing.

Figure 5.

Sequence analysis and distribution of rAAV regions involved in integration events

(A) Representative example of sequence alignments on the rAAV genome. Top track shows the position of genetic elements (5′ and 3′ ITRs, promoter, tomato, and WPRE) within rAAV; bottom track shows a portion of the alignments. (B) Overall frequency distribution (in percent) of integration site breakpoints along the rAAV genome. (C) Frequency (percentage) of integration site breakpoints within rAAV, normalized by the length of each genetic element (numbers on top of each bar represent the number of observations). (D) Recurrent motif analysis on the 100-bp interval surrounding each integration site breakpoint. Top panel: palindromic sequences identified in the human sequence (Hg19). Middle panel: frequency distribution (in percent) of palindromes found across the rAAV genome (genetic element within the AAV genome is indicated). Bottom panel: 6 out 24 palindromic sequences identified in the rAAV genome are shown. (See Figure S2 for remaining motifs.)

To understand if recurrent DNA sequence motifs were specifically involved in the integration process, we analyzed the sequences encompassing the vector integration sites both in the rAAV and human genomes. To this purpose, we used the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) algorithm to scan a sequence interval of ±50 bp surrounding each integration site (see Materials and methods for details of the settings used). From this analysis, we found 24 significantly enriched motifs within the rAAV genome (maximum E-Value (expect value) < 0.01), 10 of which mapped in the GC-rich palindromic sequences of the ITRs. The remaining 14 motifs mapped between ITRs and showed features of degenerated palindromes (Figures 5D and S2). On the other hand, the analysis of human DNA sequences at the insertion site also revealed a significant enrichment in degenerated palindromic sequences, some of which showed microhomologies with the rAAV palindromes involved in the recombination event (Figure 5D).

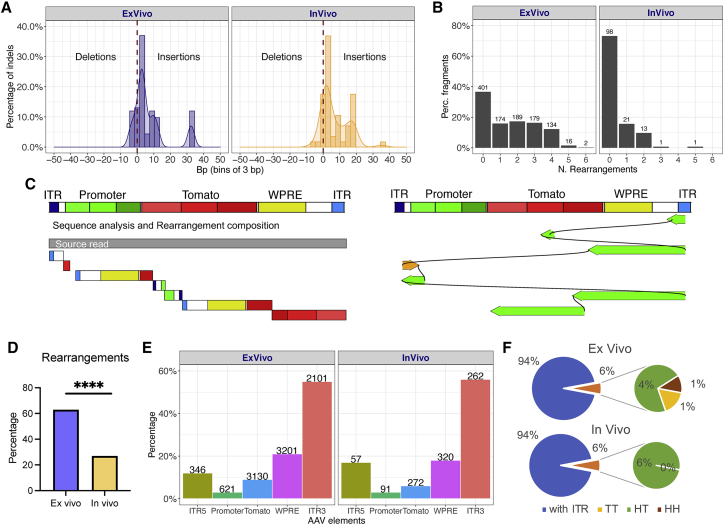

PacBio long-read sequences reveal complex rearrangements of integrated rAAV genomes spanning several kilobases

The use of the PacBio sequencing platform allowed us to investigate the integrity of the cellular genomic sequences surrounding the integration sites and the rAAV genome over several kilobases of sequence. To assess the integrity of the cellular genome upon AAV integration, we selected sequencing reads in which rAAV sequences were surrounded by the cellular genomic DNA (gDNA) sequences site at both ends. A total of 56 out of 370 reads with mappable rAAV/cellular genomic junctions matched this criterion. Deletions of cellular genomic sequences were found at a relative frequency of 2% and 10% in ex vivo and in vivo samples, respectively, and ranged from 5 to 10 bp in size. Insertions of DNA sequences of unclear origin were found in 80% of the reads, whereas reads containing both deletions and insertions represented the 10% of the total for both datasets (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Rearrangements of the rAAV genome in ex vivo- and in vivo-transduced human hepatocytes

(A) Analysis of insertions and deletions (indels) in chimeric reads. (B) Percentage (y axis) of AAV genomes with zero to six rearranged fragments (in x axis). (C) Representative examples of rAAV genomic rearrangements from the source read (on the left side) and aligned to the AAV reference genome (on the right side). The AAV sequence is annotated with different features and use of distinct colors. Within each feature, we used color scales to split longer features in shorter segments. 5′ ITR is colored in blue, whereas 3′ ITR in light blue; promoter in green; tdTomato in red; WPRE in yellow. Starting from the source read (in gray), each rearrangement is plotted as a single rectangle composed by colored segments that indicate the AAV mapping position and orientation. On the right side, a linear representation of all aligned rearrangements. Rearrangements are plotted under the reference genome in the corresponding alignment position and orientation (positive orientation in orange; negative orientation in green). Consecutive rearrangements are visualized in order of appearance and connected by curved links. (D) Frequency of rAAV sequences with one or more rearrangements observed in ex vivo and in in vivo datasets (p < 0.0001 by two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). (E) Percentage of AAV features covered by rearrangements normalized by each feature size. On top of each bar, the absolute number of rearrangements. (F) AAV concatemer analysis. Nested pie chart of the percentage of AAV concatemer for in vivo and ex vivo datasets, showing the proportion of rearrangements having at least one ITR and the observed concatemers in the three classes: head to tail (HT), tail to tail (TT), and head to head (HH).

To study the integrity of the rAAV genome, we analyzed the 370 sequencing reads containing both rAAV and human sequences (chimeras) and 859 containing only rAAV sequences. In general, no full-length rAAV sequences were found in any dataset. In the in vivo dataset, >70% of the sequencing reads (98 of 134) contained an intact rAAV genomic segment, whereas in the ex vivo dataset, the frequency of intact rAAV sequences decreased to <40% (401 of 1,095) (Figure 6B). The remaining sequencing reads contained from one (corresponding to 2 rAAV genome fragments) to up to 6 rearrangements (corresponding to 7 rAAV genome fragments) represented by duplications, inversions, deletions, and complex shuffling of rAAV segments (Figures 6C and S3). In the chimeric reads, the rearrangements involving a single rAAV segment were the most frequent (18% in ex vivo and 16% in in vivo samples) (Figure S4), whereas the frequency of rearrangements with more segments decreased progressively with the number of segments involved. The reads containing only rAAV sequences (Figure S4) appeared to be enriched in rearranged sequences, as the reads with no rearrangements represented only 2% (n = 22) of the ex vivo reads. On the other hand, in the ex vivo dataset, we observed that >95% (n = 1,099) of the rearrangements involved up to 5 segments. In the in vivo dataset, the number of AAV-only reads with rearrangements was lower (n = 31) compared to the ex vivo dataset and involved mostly rearrangements with one (n = 12) or two segments (n = 18).

In the ex vivo dataset, the sequencing reads with rearrangements were >60%, whereas in the in vivo dataset, the frequency decreased to >20% (p < 0.0001 by two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 6D; Table S6).

The AAV feature most involved in the intramolecular recombinations was the 3′ ITR, which after normalization by length, was ∼55% of all events, whereas the 5′ ITR was ∼15%, which is even less than WPRE recombinations that instead were found at a frequency of 20% (Figure 6E). We deepened the analysis of rearrangements to identify potential AAV concatemers defined as recombination events involving two ITRs. We classified concatemers as head to tail (5′ ITR fused to 3′ ITR), tail to tail (3′ ITR fused to 3′ ITR), and head to head (5′ ITR fused to 5′ ITR). Overall, the number of recombination events involving two ITRs was 6% in both in vivo and ex vivo datasets (Figure 6F). Within the fraction of reads containing concatamerization events, the head-to-tail forms were highly predominant at 71% and 100% in ex vivo and in vivo datasets, respectively. The tail-to-tail and head-to-head forms were absent in the in vivo dataset but found at a frequency of 16.8% and 11.9%, respectively, in the ex vivo dataset (Figure 6F). Interestingly, head-to-tail events were significantly favored compared to the other forms involving identical ITRs (head to tail versus sum of head to head and tail to tail, p < 0.0039 by Fisher’s exact test). Overall, these data indicate that intramolecular recombination events involved mainly the 3′ ITR and occurred more frequently in the ex vivo than in the in vivo dataset. Recombination events involving two ITRs appeared to be disfavored compared to recombination events involving a single ITR and other portions of the AAV genome.

The abundance of each clone harboring an IS was calculated by measuring the proportion of the independent sequencing reads containing the specific IS (Table S2). Overall, up to 80% of clones were represented by 1 or 2 genomes, whereas the remaining clones reached up to a maximum of 6 genomes. Therefore, no dominant clones were observed. Moreover, we analyzed the gene classes preferentially targeted by IS with GREAT software, and no gene classes were determined to be significantly enriched.

Recombination events between AAV and the cell-host genome in our dataset were then compared to the recently published dataset of hepatitis B virus (HBV) integration in human hepatocellular carcinomas and healthy tissues.55 Similar to HBV integrations, the distribution of AAV IS showed a skewing toward telomeres and centromeres in both ex vivo and in vivo datasets (Figure S5). Moreover, the AAV IS that is nearby to centromeric and telomeric regions did not show an increase in rearrangements compared to AAV IS mapping distantly (Figure S6).

Discussion

rAAV vectors are generally considered to be “non-integrating,” and it is certainly true that the majority of transgene-expressing cells contain only rAAV episomes immediately after transduction. However, it has been long known that rAAV can also integrate into chromosomal DNA, and this observation has recently become a safety concern.5,43,47,50 An adult human liver contains ∼100 billion hepatocytes, and hence, even a “very low” integration frequency of 0.1% would produce 100 million random rAAV integrations if the majority of hepatocytes are transduced by the vector. In order to better understand the potential for insertional mutagenesis by rAAV, the true number of chromosomal integrations and their structure is of high importance. In this study, we used a humanized liver mouse model to analyze the integration profile and genomic rearrangements of an rAAV genome in human hepatocytes transduced both in vivo and ex vivo. In vivo transduction is the most typical gene-delivery method for rAAVs, whereas ex vivo transduction is utilized in gene-editing applications for greater control.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14,56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64. In this model, primary human hepatocytes, upon transplantation into immune-deficient mice with deficiency of Fah, proliferate and repopulate >70% of the recipient liver.53 Using this approach, we observed that the livers of primary, secondary, and tertiary mouse recipients transplanted with ex vivo- or in vivo-transduced human hepatocytes had from 0.6% up to 2.8% rAAV-marked (tdTomato+) hepatocytes. Since in these experimental settings, the ex vivo- and in vivo-transduced human hepatocytes must have replicated at least 10 times during liver regeneration, episomes are diluted at least 1/million fold. Hence, the expression of the transgene must derive from rAAV genomes stably integrated in the host genome. This rate of integration was much higher than previously reported in other preclinical models and patients.16,17,23,37 The numbers translate into 60 to 280 million integration-bearing hepatocytes per adult human liver, if 10% of cells are transduced. It should be noted that our methodology can only ascertain productive integrations, i.e., those in which the transgene cassette is intact, producing reporter gene expression. Hence, the numbers found here represent a low-end estimate, and integrations with transgene silencing could be even more common.

To analyze the integration profile and genomic rearrangements of rAAV, we adopted the targeted capture of AAV genomes followed by a PacBio SMRT sequencing approach, a method that has been sporadically used for the characterization of the genomic integrity of rAAV preparations.65,66 In our hands, the analysis of 10−20 million sequencing reads with an average size of 5 kb has allowed us to identify >1,200 sequencing reads containing the AAV genome, 370 of which contained the rAAV/cellular genomic junction at the integration site, whereas the remaining reads contained only rAAV genomes rearranged in diverse ways. The fact that 69% of the sequences captured were devoid of adjacent gDNA is consistent with the previously reported observation that rAAV integrations frequently do not represent single copies but consist of concatamers.67 Although only 30% of the AAV containing reads also contained human DNA, their length was sufficient to univocally map all reads on the human genome. By comparison, when conventional PCR-based methods for integration-site retrieval are used, which rely on 100−500 bp-long reads, 30% are discarded because of landing in repeated regions that cannot univocally be mapped.68,69 Whereas we did not capture as many on-target reads as we had anticipated, when we sequenced the pre-capture library, only 3 reads contained the AAV genome. Hence, our capture method resulted in an approximately thousand-fold enrichment. In this study, we had 4× tiled the AAV genome, which resulted in 120 probes. Capture reactions work best when there is a large pool of probes; the greater the number of probes, the better the capture efficiency. In future studies, the on-target capture efficiency could be improved by increasing the number of capture probes.

Analysis of the profile of this relatively small number of integration sites showed the already-described tendency of rAAV to integrate within genes, TSSs, and CpG islands and without any evidence of genotoxicity. The use of targeted capture and long-range sequencing showed that the ITRs were involved in 60% of integrations, whereas the remaining events occurred across the entire rAAV genome. Therefore, these data confirm the preferential involvement of the hairpin structures of the rAAV ITRs in genomic integration events.25,30,31 On the other hand, the analysis of long reads used here has allowed us to better characterize the ratios of recombination within the AAV genome without the biases imposed by selective interrogation of specific rAAV portions with short sequencing reads. Moreover, our analysis confirms the previous notion that palindromic sequences within the vector (and not only those in the ITRs) and the homology between AAV-donor template and cellular genomic sequences appeared to play an important role in the recombination leading to AAV genomic insertions in human hepatocytes expanded in vivo.24

The analysis of PacBio long sequencing reads revealed a previously unappreciated tendency of rAAV to form complex backbone rearrangements spanning several kilobases, which could not be revealed by conventional sequencing of relatively short PCR products. Moreover, we observed a few cases of integrated plasmid sequences including those encoding for the bacterial gene for resistance to the antibiotic ampicillin. Importantly, whereas rearranged forms of rAAV represented >20% of the hepatocytes transduced in vivo, the frequency in ex vivo-transduced hepatocytes was markedly increased, reaching a frequency of ∼60%. The case for a strong tendency of the rAAV genome to recombine is even more pronounced if we consider that in 40% of sequencing reads for which we do not have evidence of rearrangements of the AAV genome, the vector/cellular genome junction landed within the promoter, tdTomato, or WPRE elements. These events could be still considered a rearrangement of the vector backbone. Therefore, our data suggest that the rAAV dose is correlated not only to an increase of the overall number of insertions (thereby increasing the risk of insertional mutagenesis) but also to the rate of rAAV genomes with extensive recombination events. Given that the ex vivo- and in vivo-transduced hepatocytes were treated with the same vector preparations, we exclude that the increased frequency of rearranged rAAV forms may arise from the vector preparation itself. Hence, the recombination and integration events must have occurred within the hepatocytes relatively fast, and the increased frequency of rearrangements in the ex vivo dataset is likely related to the MOI used. Our findings on the effect of MOI on vector rearrangements are only suggestive and not conclusive at this time. Future studies using multiple independent repeats of transduction and performing a proper dose response will be needed to solidify this hypothesis. Our data indicate that transgene expression can be maintained in concatenated rAAV genomes, where, despite the rearrangements, one or more expression modules are still functional.70 Alternatively, transgene expression could be driven by trapping a cellular promoter upstream of an integrated rAAV.62

The observation that there is such a high number of insertions of fragments or heavily rearranged forms of rAAV and plasmid sequences across the genome in ex vivo-transduced hepatocytes raises some concerns regarding the safety of the dosages used in rAAV-based gene-therapy applications. For example, random integration of rAAV fragments such as the ITRs or vector promoter sequences upstream of oncogenes may lead to their activation. Such events have been involved in oncogenesis in humans as well as in clonal expansion of hepatocytes in a preclinical model of hemophilia gene therapy in dogs.50 Therefore, avoiding high recombination rates could reduce the overall number of dangerous promoter-only insertions. Our observations also have implications for the use of rAAV as a DNA donor template in gene-editing applications. We show here that ex vivo transduction of human hepatocytes at a MOI of 100,000 vg/cell (vector genomes/cell) resulted in an rAAV integration frequency of ∼3% and was associated with significant vector rearrangements. Since the rAAV dosages used in gene editing range from 2−5 × 104 up to 10 × 106 vg/cell, depending on the laboratory and on the specific protocol, our data suggest that fine tuning of the AAV dosage could be quite relevant for gene-editing applications.58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64

Our study also has some noteworthy limitations. It is likely that capture and PacBio sequencing underrepresents GC-rich regions such as the promoter used in this study. GC-rich sequences cannot be easily enriched, leading to poor coverage of this functionally important region of the vector. Further improvements in the future will be aimed to solve this outstanding issue. In addition, the number of vector integration sites analyzed here was only in the hundreds, and additional insights into the nature of rAAV integrations could be garnered by sequencing a higher number of such events. An important additional caveat with our model is that it involves extensive hepatocyte replication to remove episomes. Although active cell division is a feature of pediatric livers and many monogenic liver diseases, the liver is fairly quiescent in healthy adults and in genetic liver diseases that do not cause liver injury (hemophilia, for example). It is possible that cell division directly enhances AAV integration and that our study therefore overestimates the integration frequency of AAV in quiescent hepatocytes. Previous studies on AAV integration did not involve regenerating liver.16,33,50 On the other hand, these same studies relied completely on sequencing of genomic junctions to estimate integration frequency. Given the secondary structure of AAV ITRs and the competition of episomes in PCR-based methods of junction capture, it is possible that sequencing methods underestimate the true genomic integration frequency of AAV.

Materials and methods

Vector production

AAV-CAG-tdTomato was the only vector used in this study. The expression of the fluorescent reporter gene is driven by the CAG promoter (a synthetic hybrid promoter containing the CMV (cytomegalovirus) enhancer, first exon and intron of the chicken beta-actin gene, and splice acceptor of the rabbit beta-globin gene). The vector was packaged in the AAV-DJ serotype by cotransfection of HEK293 cells with the vector plasmid (p)AAV-CAG-tdTomato and pDJ (capsid plasmid) and pHelper packaging plasmids as described previously.47,71

Animal care

FRGN mice were bred at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) and maintained on 8 mg/L of NTBC (Ark Pharm, Arlington Heights, IL, USA) in drinking water until transplantation.72 Following transplantation, the mice were cycled on NTBC as described below. All animal experiments were approved by the OHSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Portland, OR, USA) and performed in accordance with the approved protocols.

Transplantation of human hepatocytes

Two transduction paradigms were utilized: ex vivo and in vitro. For the ex vivo paradigm, human hepatocytes were plated in DMEM complete (10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 2 mM GlutaMax, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 IU/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin) and were transduced with AAV-CAG-tdTomato at a MOI of 1 × 105; at this MOI, more than 90% of the cells were transduced. The cells were cultured overnight (16−20 h) on collagen-coated plates, and the following day, cells were washed with PBS and harvested with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA. Five hundred thousand viable hepatocytes were used for transplantation. For the in vivo paradigm, humanized FRGN mice (human albumin ≥ 2 mg/mL) were injected via retro-orbital injection with 1 × 1011 vg of AAV-CAG-tdTomato per mouse. This dose was selected based on what is administered in human gene-therapy trials (a dose of 1 × 1011 vg/mouse translates to approximately 5 × 1012 vg/kg in humans). After 2 weeks, hepatocytes were harvested using a standard collagenase perfusion protocol as described previously, and five hundred thousand viable hepatocytes were transplanted into FRGN mice without purification of human from mouse cells.53 Transplantation and serial transplantation (hepatocytes from a repopulated FRGN mouse transplanted into another FRGN recipient) were performed as described previously.53 Following transplantation, the mice were subjected to a cycling NTBC withdrawal regimen (7 days off, 5 days on 8 mg/L NTBC for two cycles; 7 days off, 4 days on for two cycles; 7 days off, 3 days on for two cycles; and 21 days off, 5 days on for two cycles). Human albumin levels were measured to assess for humanization as described previously.53

FACS analysis

Vector integration frequency in human hepatocytes was assessed by flow. Hepatocytes were harvested from repopulated mice, and one million viable hepatocytes were labeled with OC2-2F8 (1:50 dilution), OC2-2G9 (1:50 dilution), APC (allophycocyanin) anti-mouse CD45 (1:200 dilution), and mouse α rat immunoglobulin G (IgG)-647 (1:400 dilution).73 This combination labels mouse hepatocytes and NPCs and leaves human hepatocytes unlabeled. The cells were analyzed on the BD FACSymphony to measure the percentage of tdTomato-positive human hepatocytes.

Capture sequencing

Hepatocytes were harvested from primary recipient-repopulated mice (in vivo and ex vivo), and mouse cells were depleted by magnetic-activated cell sorting using the mouse cell depletion kit per the manufacturer’s protocol (Miltenyi Biotec, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The human hepatocyte-enriched cells were then labeled with the antibodies used for FACS analysis, and tdTomato-positive human hepatocytes were sorted on a BD FACSAria cell sorter, which resulted in >90% enrichment of human hepatocytes. For the in vivo paradigm, hepatocytes from two mice (infected with rAAV) were serially transplanted into primary recipient mice; human hepatocytes were harvested from five primary recipients by FACS, and the enriched cells were then pooled together. Similarly, for the ex vivo paradigm, human hepatocytes were harvested from three primary recipients, and FACS-enriched cells from these three mice were pooled together; the cells had to be pooled together to obtain enough DNA for capture sequencing after FACS. gDNA was isolated from these cells using the MasterPure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit (Lucigen, Middleton, WI, USA), per the manufacturer’s protocol, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The DNA pellet was resuspended in TE (Tris, EDTA) buffer, and the concentration was measured using the Qubit Fluorometer. PacBio library preparation was performed by the University of Oregon’s Genomics & Cell Characterization Core Facility (GC3F), and the capture reaction was performed in house. Briefly, the gDNA was sheared to approximately 6 kb fragments, followed by end repair/A-tailing and barcoded adaptor ligation using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit. Library amplification was performed using the PacBio universal primers and the Takara Hot-Start LA Taq DNA Polymerase. The thermocycler condition was as follows: (1) 95°C/2 min > (2) 95°C/20 s > (3) 62°C/15 s > (4) 68°C/10 min > (5) repeat steps 2 to 4 for 6 cycles > (6) 68°C/5 min > (7) 4°C/hold. The PCR product was bead purified and size selected for 6 kb products using the BluePippin system. Biotinylated probes covering the entire AAV-CAG-tdTomato genome (4× tiled) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) (see Table S1 for a complete list of probe sequences). The capture reaction was performed using IDT’s xGen Lockdown Reagents per the manufacturer’s protocol with the following modifications: 5 μg of human Cot DNA and 5 μg mouse Cot DNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for blocking in the capture reaction. A step-down hybridization reaction program was used (95°C for 10 min > 90°C for 1 min > 85°C for 1 min > 80°C for 1 min > 75°C for 1 min > 70°C for 1 min > 65°C for 16 h). Following hybridization and bead capture, subsequent library preparation steps were performed by GC3F. Briefly, amplification was performed as described above, except steps 2 to 4 were repeated for 20 cycles, followed by SMRTbell library preparation using the SMRTbell Template Prep Kit per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bioinformatics analysis

A dedicated bioinformatics pipeline was developed to analyze the PacBio sequences (NCBI SRA (sequence read archive) BioProject: PRJNA746556) aimed at detecting integration events, identifying AAV rearrangements and plot results. No current tools showed the required software features; thus, we implemented a new software. Specific details are reported in the methodological paper (currently in progress), and here, we summarize the steps. Following the schema in Figure 1, quality checks of input sequences were run using FastQC and MultiQC, whereas barcode and adaptor sequences were trimmed by Flexbar.74, 75, 76 We then aligned PacBio sequences to the AAV genome (including plasmid backbone components) to identify the reads containing AAV portions using BWA-MEM (Burrows-Wheeler aligner - maximal exact match). and then to the hybrid genome of AAV and human genome (release hg19 downloaded from UCSC (University of California, Santa Cruz) Genome Browser web site) to identify integration loci and all vector rearrangements.77 We designed and implemented a custom R script to process alignments and identify vector-genome junctions by exploiting the alignment CIGAR (concise idiosyncratic gapped alignment report) string (R, version 4.01). Distribution along TSSs and CpG islands was computed with bedtools.78 Motif searches were processed using MEME suite, configured to look for palindromes with the following parameters: “-dna -mod zoops -nmotifs 50 -wnsites 0.8 -evt 0.1 -minw 15 -spmap uni -sf -pal -mpi”79. For Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, we used the GREAT online tool, version 4 (http://great.stanford.edu/public/html/).80 To study rAAV rearrangements both in chimeric reads and in reads containing only rAAV sequences, we identified unique fragments containing AAV. For chimeric reads, we used the IS genomic coordinates, whereas for AAV-only sequences, we identified unique fragments as a surrogate of independent source genomes. Unique fragments were identified considering alignment start and end, such that two reads were considered derived by the same fragment if the alignment size is the same (±5 bp), and the number of rearrangements is identical. We applied this approach to source-aligned reads (Table S3), and the resulting table with all independent fragments from AAV reads is available in Tables S4 and S5, with the corresponding R code to reproduce the data (Data S1).

Acknowledgments

We thank Carlo Cipriani for the help on bioinformatics revisions. This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant R01CA190144 to W.E.N. and M.G.

Author contributions

D.A.D. and A.T. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and helped write the manuscript. A.C. designed and performed bioinformatics analysis and helped write the manuscript. J.P. produced and quantified AAV. M.G. and W.E.N. conceived the project, helped design experiments, and helped write the manuscript. E.M. analyzed bioinformatics and helped write the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

M.G. has a financial interest in Yecuris Corp. (Tigard, Oregon), a company that has commercialized the humanized mouse liver model used in this work. MG also is a consultant for LogicBio Therapeutics. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.08.031.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Shahryari A., Saghaeian Jazi M., Mohammadi S., Razavi Nikoo H., Nazari Z., Hosseini E.S., Burtscher I., Mowla S.J., Lickert H. Development and Clinical Translation of Approved Gene Therapy Products for Genetic Disorders. Front. Genet. 2019;10:868. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anguela X.M., High K.A. Entering the Modern Era of Gene Therapy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019;70:273–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012017-043332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podsakoff G., Wong K.K., Jr., Chatterjee S. Efficient gene transfer into nondividing cells by adeno-associated virus-based vectors. J. Virol. 1994;68:5656–5666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5656-5666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daya S., Berns K.I. Gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008;21:583–593. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandler R.J., Sands M.S., Venditti C.P. Recombinant Adeno-Associated Viral Integration and Genotoxicity: Insights from Animal Models. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017;28:314–322. doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell D.W., Miller A.D., Alexander I.E. Adeno-associated virus vectors preferentially transduce cells in S phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:8915–8919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis B.L., Hirsch M.L., Barker J.C., Connelly J.P., Steininger R.J., 3rd, Porteus M.H. A survey of ex vivo/in vitro transduction efficiency of mammalian primary cells and cell lines with Nine natural adeno-associated virus (AAV1-9) and one engineered adeno-associated virus serotype. Virol. J. 2013;10:74. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang J.J., Lauramore A., Deng W.T., Li Q., Doyle T.J., Chiodo V., Li J., Hauswirth W.W. Comparative analysis of in vivo and in vitro AAV vector transduction in the neonatal mouse retina: effects of serotype and site of administration. Vision Res. 2008;48:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivière C., Danos O., Douar A.M. Long-term expression and repeated administration of AAV type 1, 2 and 5 vectors in skeletal muscle of immunocompetent adult mice. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1300–1308. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sehara Y., Fujimoto K.I., Ikeguchi K., Katakai Y., Ono F., Takino N., Ito M., Ozawa K., Muramatsu S.I. Persistent Expression of Dopamine-Synthesizing Enzymes 15 Years After Gene Transfer in a Primate Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev. 2017;28:74–79. doi: 10.1089/humc.2017.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niemeyer G.P., Herzog R.W., Mount J., Arruda V.R., Tillson D.M., Hathcock J., van Ginkel F.W., High K.A., Lothrop C.D., Jr. Long-term correction of inhibitor-prone hemophilia B dogs treated with liver-directed AAV2-mediated factor IX gene therapy. Blood. 2009;113:797–806. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-181479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava A. In vivo tissue-tropism of adeno-associated viral vectors. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016;21:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verdera H.C., Kuranda K., Mingozzi F. AAV Vector Immunogenicity in Humans: A Long Journey to Successful Gene Transfer. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:723–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinowitz J., Chan Y.K., Samulski R.J. Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) versus Immune Response. Viruses. 2019;11:E102. doi: 10.3390/v11020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz B.R., Chamberlain J.S. Recombinant adeno-associated virus transduction and integration. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1189–1199. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gil-Farina I., Fronza R., Kaeppel C., Lopez-Franco E., Ferreira V., D’Avola D., Benito A., Prieto J., Petry H., Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G., Schmidt M. Recombinant AAV Integration Is Not Associated With Hepatic Genotoxicity in Nonhuman Primates and Patients. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:1100–1105. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gil-Farina I., Schmidt M. Interaction of vectors and parental viruses with the host genome. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016;21:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao G., Vandenberghe L.H., Alvira M.R., Lu Y., Calcedo R., Zhou X., Wilson J.M. Clades of Adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J. Virol. 2004;78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen C.L., Jensen R.L., Schnepp B.C., Connell M.J., Shell R., Sferra T.J., Bartlett J.S., Clark K.R., Johnson P.R. Molecular characterization of adeno-associated viruses infecting children. J. Virol. 2005;79:14781–14792. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14781-14792.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnepp B.C., Jensen R.L., Chen C.L., Johnson P.R., Clark K.R. Characterization of adeno-associated virus genomes isolated from human tissues. J. Virol. 2005;79:14793–14803. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14793-14803.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotin R.M., Linden R.M., Berns K.I. Characterization of a preferred site on human chromosome 19q for integration of adeno-associated virus DNA by non-homologous recombination. EMBO J. 1992;11:5071–5078. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell D.W., Hirata R.K. Human gene targeting by viral vectors. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:325–330. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarty D.M., Young S.M., Jr., Samulski R.J. Integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) and recombinant AAV vectors. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:819–845. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inagaki K., Lewis S.M., Wu X., Ma C., Munroe D.J., Fuess S., Storm T.A., Kay M.A., Nakai H. DNA palindromes with a modest arm length of greater, similar 20 base pairs are a significant target for recombinant adeno-associated virus vector integration in the liver, muscles, and heart in mice. J. Virol. 2007;81:11290–11303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00963-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller D.G., Trobridge G.D., Petek L.M., Jacobs M.A., Kaul R., Russell D.W. Large-scale analysis of adeno-associated virus vector integration sites in normal human cells. J. Virol. 2005;79:11434–11442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11434-11442.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutledge E.A., Russell D.W. Adeno-associated virus vector integration junctions. J. Virol. 1997;71:8429–8436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8429-8436.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponnazhagan S., Erikson D., Kearns W.G., Zhou S.Z., Nahreini P., Wang X.S., Srivastava A. Lack of site-specific integration of the recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 genomes in human cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 1997;8:275–284. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.3-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller D.G., Rutledge E.A., Russell D.W. Chromosomal effects of adeno-associated virus vector integration. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:147–148. doi: 10.1038/ng824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakai H., Iwaki Y., Kay M.A., Couto L.B. Isolation of recombinant adeno-associated virus vector-cellular DNA junctions from mouse liver. J. Virol. 1999;73:5438–5447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5438-5447.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakai H., Montini E., Fuess S., Storm T.A., Grompe M., Kay M.A. AAV serotype 2 vectors preferentially integrate into active genes in mice. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:297–302. doi: 10.1038/ng1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakai H., Wu X., Fuess S., Storm T.A., Munroe D., Montini E., Burgess S.M., Grompe M., Kay M.A. Large-scale molecular characterization of adeno-associated virus vector integration in mouse liver. J. Virol. 2005;79:3606–3614. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3606-3614.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandler R.J., LaFave M.C., Varshney G.K., Trivedi N.S., Carrillo-Carrasco N., Senac J.S., Wu W., Hoffmann V., Elkahloun A.G., Burgess S.M., Venditti C.P. Vector design influences hepatic genotoxicity after adeno-associated virus gene therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:870–880. doi: 10.1172/JCI79213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nault J.C., Datta S., Imbeaud S., Franconi A., Mallet M., Couchy G., Letouzé E., Pilati C., Verret B., Blanc J.F. Recurrent AAV2-related insertional mutagenesis in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1187–1193. doi: 10.1038/ng.3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.La Bella T., Imbeaud S., Peneau C., Mami I., Datta S., Bayard Q., Caruso S., Hirsch T.Z., Calderaro J., Morcrette G. Adeno-associated virus in the liver: natural history and consequences in tumour development. Gut. 2020;69:737–747. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donsante A., Miller D.G., Li Y., Vogler C., Brunt E.M., Russell D.W., Sands M.S. AAV vector integration sites in mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Science. 2007;317:477. doi: 10.1126/science.1142658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan J.K.Y., Gil-Farina I., Johana N., Rosales C., Tan Y.W., Ceiler J., Mcintosh J., Ogden B., Waddington S.N., Schmidt M. Therapeutic expression of human clotting factors IX and X following adeno-associated viral vector-mediated intrauterine gene transfer in early-gestation fetal macaques. FASEB J. 2019;33:3954–3967. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801391R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Avola D., López-Franco E., Sangro B., Pañeda A., Grossios N., Gil-Farina I., Benito A., Twisk J., Paz M., Ruiz J. Phase I open label liver-directed gene therapy clinical trial for acute intermittent porphyria. J. Hepatol. 2016;65:776–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gauttier V., Pichard V., Aubert D., Kaeppel C., Schmidt M., Ferry N., Conchon S. No tumour-initiating risk associated with scAAV transduction in newborn rat liver. Gene Ther. 2013;20:779–784. doi: 10.1038/gt.2013.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inagaki K., Piao C., Kotchey N.M., Wu X., Nakai H. Frequency and spectrum of genomic integration of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 8 vector in neonatal mouse liver. J. Virol. 2008;82:9513–9524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01001-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaeppel C., Beattie S.G., Fronza R., van Logtenstein R., Salmon F., Schmidt S., Wolf S., Nowrouzi A., Glimm H., von Kalle C. A largely random AAV integration profile after LPLD gene therapy. Nat. Med. 2013;19:889–891. doi: 10.1038/nm.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattar C.N.Z., Gil-Farina I., Rosales C., Johana N., Tan Y.Y.W., McIntosh J., Kaeppel C., Waddington S.N., Biswas A., Choolani M. In Utero Transfer of Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors Produces Long-Term Factor IX Levels in a Cynomolgus Macaque Model. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1843–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pañeda A., Lopez-Franco E., Kaeppel C., Unzu C., Gil-Royo A.G., D’Avola D., Beattie S.G., Olagüe C., Ferrero R., Sampedro A. Safety and liver transduction efficacy of rAAV5-cohPBGD in nonhuman primates: a potential therapy for acute intermittent porphyria. Hum. Gene Ther. 2013;24:1007–1017. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donsante A., Vogler C., Muzyczka N., Crawford J.M., Barker J., Flotte T., Campbell-Thompson M., Daly T., Sands M.S. Observed incidence of tumorigenesis in long-term rodent studies of rAAV vectors. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1343–1346. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang P.R., Xu M., Toffanin S., Li Y., Llovet J.M., Russell D.W. Induction of hepatocellular carcinoma by in vivo gene targeting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:11264–11269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117032109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walia J.S., Altaleb N., Bello A., Kruck C., LaFave M.C., Varshney G.K., Burgess S.M., Chowdhury B., Hurlbut D., Hemming R. Long-term correction of Sandhoff disease following intravenous delivery of rAAV9 to mouse neonates. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:414–422. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chandler R.J., LaFave M.C., Varshney G.K., Burgess S.M., Venditti C.P. Genotoxicity in Mice Following AAV Gene Delivery: A Safety Concern for Human Gene Therapy? Mol. Ther. 2016;24:198–201. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dalwadi D.A., Torrens L., Abril-Fornaguera J., Pinyol R., Willoughby C., Posey J., Llovet J.M., Lanciault C., Russell D.W., Grompe M., Naugler W.E. Liver Injury Increases the Incidence of HCC following AAV Gene Therapy in Mice. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:680–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferla R., Alliegro M., Dell’Anno M., Nusco E., Cullen J.M., Smith S.N., Wolfsberg T.G., O’Donnell P., Wang P., Nguyen A.D. Low incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in mice and cats treated with systemic adeno-associated viral vectors. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020;20:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosas L.E., Grieves J.L., Zaraspe K., La Perle K.M., Fu H., McCarty D.M. Patterns of scAAV vector insertion associated with oncogenic events in a mouse model for genotoxicity. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:2098–2110. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen G.N., Everett J.K., Kafle S., Roche A.M., Raymond H.E., Leiby J., Wood C., Assenmacher C.A., Merricks E.P., Long C.T. A long-term study of AAV gene therapy in dogs with hemophilia A identifies clonal expansions of transduced liver cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021;39:47–55. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0741-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russell D.W., Grompe M. Adeno-associated virus finds its disease. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1104–1105. doi: 10.1038/ng.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colella P., Ronzitti G., Mingozzi F. Emerging Issues in AAV-Mediated In Vivo Gene Therapy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2017;8:87–104. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azuma H., Paulk N., Ranade A., Dorrell C., Al-Dhalimy M., Ellis E., Strom S., Kay M.A., Finegold M., Grompe M. Robust expansion of human hepatocytes in Fah-/-/Rag2-/-/Il2rg-/- mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:903–910. doi: 10.1038/nbt1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ehrhardt A., Xu H., Kay M.A. Episomal persistence of recombinant adenoviral vector genomes during the cell cycle in vivo. J. Virol. 2003;77:7689–7695. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7689-7695.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Péneau C., Imbeaud S., La Bella T., Hirsch T.Z., Caruso S., Calderaro J., Paradis V., Blanc J.F., Letouzé E., Nault J.C. Hepatitis B virus integrations promote local and distant oncogenic driver alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2021 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323153. Published online February 9, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palaschak B., Herzog R.W., Markusic D.M. AAV-Mediated Gene Delivery to the Liver: Overview of Current Technologies and Methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1950:333–360. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9139-6_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pouzolles M., Machado A., Guilbaud M., Irla M., Gailhac S., Barennes P., Cesana D., Calabria A., Benedicenti F., Sergé A. Intrathymic adeno-associated virus gene transfer rapidly restores thymic function and long-term persistence of gene-corrected T cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;145:679–697.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferrari S., Jacob A., Beretta S., Unali G., Albano L., Vavassori V., Cittaro D., Lazarevic D., Brombin C., Cugnata F. Efficient gene editing of human long-term hematopoietic stem cells validated by clonal tracking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:1298–1308. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0551-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scharenberg S.G., Poletto E., Lucot K.L., Colella P., Sheikali A., Montine T.J., Porteus M.H., Gomez-Ospina N. Engineering monocyte/macrophage-specific glucocerebrosidase expression in human hematopoietic stem cells using genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3327. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17148-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schiroli G., Conti A., Ferrari S., Della Volpe L., Jacob A., Albano L., Beretta S., Calabria A., Vavassori V., Gasparini P. Precise Gene Editing Preserves Hematopoietic Stem Cell Function following Transient p53-Mediated DNA Damage Response. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24:551–565.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schiroli G., Ferrari S., Conway A., Jacob A., Capo V., Albano L., Plati T., Castiello M.C., Sanvito F., Gennery A.R. Preclinical modeling highlights the therapeutic potential of hematopoietic stem cell gene editing for correction of SCID-X1. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaan0820. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang J., Exline C.M., DeClercq J.J., Llewellyn G.N., Hayward S.B., Li P.W., Shivak D.A., Surosky R.T., Gregory P.D., Holmes M.C., Cannon P.M. Homology-driven genome editing in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells using ZFN mRNA and AAV6 donors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1256–1263. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sather B.D., Romano Ibarra G.S., Sommer K., Curinga G., Hale M., Khan I.F., Singh S., Song Y., Gwiazda K., Sahni J. Efficient modification of CCR5 in primary human hematopoietic cells using a megaTAL nuclease and AAV donor template. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:307ra156. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holt N., Wang J., Kim K., Friedman G., Wang X., Taupin V., Crooks G.M., Kohn D.B., Gregory P.D., Holmes M.C., Cannon P.M. Human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells modified by zinc-finger nucleases targeted to CCR5 control HIV-1 in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:839–847. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tai P.W.L., Xie J., Fong K., Seetin M., Heiner C., Su Q., Weiand M., Wilmot D., Zapp M.L., Gao G. Adeno-associated Virus Genome Population Sequencing Achieves Full Vector Genome Resolution and Reveals Human-Vector Chimeras. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018;9:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xie J., Mao Q., Tai P.W.L., He R., Ai J., Su Q., Zhu Y., Ma H., Li J., Gong S. Short DNA Hairpins Compromise Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Genome Homogeneity. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1363–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Z., Lisowski L., Finegold M.J., Nakai H., Kay M.A., Grompe M. AAV vectors containing rDNA homology display increased chromosomal integration and transgene persistence. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:1902–1911. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Calabria A., Beretta S., Merelli I., Spinozzi G., Brasca S., Pirola Y., Benedicenti F., Tenderini E., Bonizzoni P., Milanesi L., Montini E. γ-TRIS: a graph-algorithm for comprehensive identification of vector genomic insertion sites. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:1622–1624. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Calabria A., Leo S., Benedicenti F., Cesana D., Spinozzi G., Orsini M., Merella S., Stupka E., Zanetti G., Montini E. VISPA: a computational pipeline for the identification and analysis of genomic vector integration sites. Genome Med. 2014;6:67. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yan Z., Zak R., Zhang Y., Engelhardt J.F. Inverted terminal repeat sequences are important for intermolecular recombination and circularization of adeno-associated virus genomes. J. Virol. 2005;79:364–379. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.364-379.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grimm D., Lee J.S., Wang L., Desai T., Akache B., Storm T.A., Kay M.A. In vitro and in vivo gene therapy vector evolution via multispecies interbreeding and retargeting of adeno-associated viruses. J. Virol. 2008;82:5887–5911. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00254-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilson E.M., Bial J., Tarlow B., Bial G., Jensen B., Greiner D.L., Brehm M.A., Grompe M. Extensive double humanization of both liver and hematopoiesis in FRGN mice. Stem Cell Res. (Amst.) 2014;13(3 Pt A):404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Y., Dorrell C., Naugler W.E., Heskett M., Spellman P., Li B., Galivo F., Haft A., Wakefield L., Grompe M. Long-Term Correction of Diabetes in Mice by In Vivo Reprogramming of Pancreatic Ducts. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:1327–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roehr J.T., Dieterich C., Reinert K. Flexbar 3.0 - SIMD and multicore parallelization. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2941–2942. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brown J., Pirrung M., McCue L.A. FQC Dashboard: integrates FastQC results into a web-based, interactive, and extensible FASTQ quality control tool. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3137–3139. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ewels P., Magnusson M., Lundin S., Käller M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3047–3048. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Quinlan A.R., Hall I.M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bailey T.L., Boden M., Buske F.A., Frith M., Grant C.E., Clementi L., Ren J., Li W.W., Nble W.S. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McLean C.Y., Bristor D., Hiller M., Clarke S.L., Schaar B.T., Lowe C.B., Wenger A.M., Bejerano G. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.