Abstract

Toxoplasmosis is a global threat with significant zoonotic concern. The present in silico study was aimed at determination of bioinformatics features and immunogenic epitopes of a tyrosine-rich oocyst wall protein (TrOWP) of Toxoplasma gondii. After retrieving the amino acid sequence from UniProt database, several parameters were predicted including antigenicity, allergenicity, solubility and physico-chemical features, signal peptide, transmembrane domain, and posttranslational modifications. Following secondary and tertiary structure prediction, the 3D model was refined, and immunogenic epitopes were forecasted. It was a 25.57 kDa hydrophilic molecule with 236 residues, a signal peptide, and significant antigenicity scores. Moreover, several linear and conformational B-cell epitopes were present. Also, potential mouse and human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) and helper T-lymphocyte (HTL) epitopes were predicted in the sequence. The findings of the present in silico study are promising as they render beneficial characteristics of TrOWP to be included in future vaccination experiments.

1. Introduction

The model apicomplexan, Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), virtually infects a large number of warm-blooded animal species including humans [1]. Reportedly, one-third of the global population has shown serological traits of a previous exposure to the parasite [2]. Also, the parasite is of veterinary importance, as a well-known abortifacient among domestic livestock [3]. Within feline intestine, gametogony and sporogony occur in order to develop unsporulated oocysts. The latter are shed via feces into the environment, become infective, and contaminate food/water supplies [4]. Additionally, fast-replicating tachyzoites (transfusion-mediated and congenital infection) and slow-dividing bradyzoites (cyst-contaminated muscle tissues and organ transplant) are involved in alternative transmission pathways [5]. Notwithstanding its widespread prevalence, T. gondii infection rarely results in clinical disease in immunocompetent individuals, whereas a decreased immune status, such as the case in pregnancy and/or immunosuppressive disorders, may pave the way for the opportunistic parasite to vividly invade to the unborn via placenta or to central nervous system (CNS) tissues, respectively [6].

Disappointingly, the present chemotherapeutic options for acute infections and/or recrudescence of infection are only active against tachyzoite stages with a number of side-effects reported in treated patients [7]. Thereby, employing preventive measures such as a One-Health vaccination approach more sufficiently benefit the world [8]. Since Toxoplasma is an obligatory intracellular organism, T CD8+ responses with interferon gamma (IFN-γ) upsurge are the preferred immunity to combat acute infection. However, humoral responses are also advantageous, in particular following an oral infection with bradyzoites or oocysts [9]. Despite over 30 years of preclinical and clinical Toxoplasma vaccination using various platforms, no commercial human vaccine is registered yet [10]. The only available vaccine is the so-called “Toxovax®,” a live attenuated strain (S48) of T. gondii, for prevention of abortion in sheep, but it cannot be used in humans for safety issues [11]. The multistage life cycle of Toxoplasma requires expression of a large number of proteins during parasite stage-to-stage transition. Surface antigens (SAGs) along with organellar proteins including micronemes (MICs), rhoptries (ROPs), dense granule antigens (GRAs), and their associated molecules have been nominated as the main repository containing valuable vaccine candidates. Interestingly, some of these proteins are stage-specific (SAG1 in tachyzoite), while some may associate with multiple stages (MIC4, MIC13, ROP2, GRA8, GRA14) [12].

Although human T. gondii infection acquired via tissue cysts could be handled through proper cooking of meat products, but oocysts can thoroughly contaminate water streams, soils, and foodstuffs and survive for a long time in moist surrounding as well as fresh/marine waters [13]. This outstanding ability of oocysts is not yet fully understood, but the underlying mechanism may lie within key molecular components in the oocyst walls [14, 15]. In light of advances in omics-based technologies, an increasing trend has been raised to precisely decipher the parasite biology and to characterize critical immunocorrelates of T. gondii protection [16]. In this sense, bioinformatics methods have more facilitated the identification of biophysical features and novel immunogenic antigens/peptides in different Toxoplasma infectious stages [17]. The present in silico study was performed to have a closer look at bioinformatics properties of the T. gondii tyrosine-rich oocyst wall protein (TrOWP) and its immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) and helper T-lymphocyte (HTL) as well as B-cell epitopes using comprehensive immunoinformatics tools.

2. Methods

2.1. Amino Acid Sequence Retrieval

The complete amino acid sequence of Toxoplasma TrOWP was gathered as FASTA format via the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt), available at https://www.uniprot.org/, under entry number of V5LE41 for further bioinformatics analyses.

2.2. Prediction of Antigenicity, Allergenicity, Solubility, and Physico-Chemical Properties

Antigenicity forecasting of the protein was done through two network-based tools: VaxiJen v2.0 (http://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/vaxijen/VaxiJen/VaxiJen.html) and ANTIGENpro (http://scratch.proteomics.ics.uci.edu/). VaxiJen v2.0 is a free web tool that predicts protein antigenicity in target organisms (parasite, fungal, virus, bacteria, tumor) with desirable threshold. The prediction is based on physico-chemical features and sequence transformation into uniform vectors of amino acid characteristics via auto cross covariance (ACC) [18]. As well, particular microarray data is used by ANTIGENpro online tool, in a pathogen- and alignment-free manner [19]. Allergenic feature of the protein was evaluated using AllerTOP v2.0 (https://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/AllerTOP/) and AlgPred (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/algpred/) servers. AllerTOP utilizes E-descriptors, k-nearest neighbors, and auto/cross variance transformation algorithms [20]. Also, AlgPred employs several machine learning algorithms to determine IgE-specific epitopes and MEME (Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation)/MAST (Motif Alignment and Search Tool) allergen motifs [21]. Protein solubility was calculated using two web servers: SOLpro (http://scratch.proteomics.ics.uci.edu/) and Protein-Sol (https://protein-sol.manchester.ac.uk/). SOLpro employs a two-stage support vector machine (SVM) algorithm to check the solubility upon overexpression in Escherichia coli (E. coli) [22]. Based on the population average of the experimental dataset in Protein-Sol server, that is 0.45, any solubility value above this score is predicted to be highly soluble [23]. Finally, the physico-chemical functions of the TrOWP were determined using ExPASy ProtParam web server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/), showing the protein molecular weight (MW), positively and negatively charged residues, isoelectric point (pI), in vitro and in vivo estimated half-life, instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) [24].

Prediction of Transmembrane Domain, Signal Peptide, and Posttranslational Modification (PTM) Sites

The presence of putative transmembrane domains was evaluated using TMHMM online server, available at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/. Moreover, the prediction of PTM sites in the protein sequence such as N-glycosylation, palmitoylation, phosphorylation, and acetylation was predicted via NetNGlyc 1.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/) [25], CSS Palm (http://csspalm.biocuckoo.org/) [26], NetPhos 3.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPhos/) [27], and GPS-PAIL 2.0 (http://pail.biocuckoo.org/links.php) [28] web servers, respectively. The prediction settings were default, except for NetNGlyc and acetylation, which was based on “all Asn residues” and “all types,” correspondingly. Also, SignalP-5.0 server, available at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/, was aimed at prediction of putative signal peptide in the protein sequence [29].

2.3. Prediction of Secondary and Tertiary Structures

Two web servers were used for secondary structure analysis, including Garnier–Osguthorpe Robson (GOR) IV server with 64.4% mean accuracy (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_gor4.html) [30] and position specific iterated prediction (PSIPRED) on PSI-BLAST outputs for similarity determination (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/) [31]. Further structural analysis was aimed at predicting the three-dimensional (3D) aspect of the TrOWP protein. Hence, the protein sequence was submitted to the I-TASSER web server for homology modelling (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/) [32]. “I-TASSER (Iterative Treading ASSEmbly Refinement) is a best-ranked server which is used to create automated protein structures and prediction. Upon submission of an amino acid sequence, I-TASSER works to design a 3D atomic model by utilizing the multiple threading alignments and iterative structural assembly simulations” [33, 34].

2.4. Refinement of the 3D Structure and Validations

The best-fit, high-ranked 3D model provided by I-TASSER server was subsequently subjected for structural rehashing and relaxation purposes, using GalaxyRefine server (http://galaxy.seoklab.org/cgi-bin/submit.cgi?type=REFINE). This server is one of the best refining tools, which enhances the predicted structure through formation of side chains and their repacking, thereby providing an overall relaxation in the structure via dynamic simulations. Five refined models are yielded following calculations, based on various qualifying scores including global distance test-high accuracy (GDT-HA), root mean square deviation (RMSD), MolProbity, Clash score, Poor rotamers, and Rama favored [35]. In the next step, the quality of the refining process was checked through Ramachandran plot analysis of Zlab (https://zlab.umassmed.edu/bu/rama/) and ERRAT tool of SAVES 6.0 server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/). “ERRAT analyzes the statistics of non-bonded interactions among various atom types by comparison with statistics from highly-refined structures” [36, 37]. Furthermore, Ramachandran analysis is directed towards protein structure confirmation through energetically allowed and disallowed dihedral angles of psi (ψ) and phi (ϕ) per amino acid [38, 39].

2.5. Prediction of Continuous and Conformational B-Cell Epitopes

Identification of B-cell epitopes is a necessary step in vaccine design. For this purpose, a multistep process was designed to cover shared epitopes found through several web servers [40]; hence, three servers were utilized including BCPREDS (http://ailab-projects1.ist.psu.edu:8080/bcpred/), ABCpred (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/abcpred/) [41], and SVMTriP (http://sysbio.unl.edu/SVMTriP/) [42]. BCPREDS server provides user-friendly fixed-length (BCPred and AAP) and flexible-length (FBCPred) epitope prediction modes, based on the desired threshold using subsequent kernel (SSK) and SVM algorithms [43]. Here, a fixed-length prediction (14 amino acids) with 75% threshold was chosen. Cross-validation of predicted epitopes was done by other two servers. Ultimately, shared linear B-cell epitopes were further assessed in terms of antigenicity, allergenicity, and water solubility through VaxiJen v2.0, AllerTOP v2.0, and PepCalc (https://pepcalc.com/) online servers, respectively. As well, the protein sequence was subjected to Bcepred server in order to forecast continuous B-cell epitopes according to physico-chemical properties such as hydrophilicity, flexibility, accessibility, turns, exposed surface, polarity, and antigenic propensity (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/bcepred/). Additionally, for prediction of conformational B-cell epitopes, ElliPro tool of IEDB database was ran using default settings of 0.5 min score 6 Å max distance, which performs by neighbor residue clustering, residue protrusion index (PI), and protein shape appraisal [44].

2.6. Prediction of Mouse and Human CTL/HTL Epitopes

Those epitopes with specific binding capacity to mouse major histocompatibility complex- (MHC-) I and II molecules were predicted against MHC-I alleles (H2-Db, H2-Dd, H2-Kb, H2-Kd, H2-Kk, and H2-Ld) and MHC-II alleles (H2-IAb, H2-IAd, and H2-IEd), via IEDB MHC-I binding (http://tools.iedb.org/mhci/) and MHC-II binding (http://tools.iedb.org/mhcii/) tools, respectively. Epitope prediction was done using IEDB recommended 2020.09 (NetMHCPan EL 4.1) method for MHC-I (CTL) epitopes and IEDB recommended 2.22 for MHC-II (HTL) peptides. Each epitope is assigned a percentile rank, which inversely associate with the affinity, so that the lower is the percentile rank; the higher is the epitope affinity to the respective MHC molecule. In the following, mouse MHC-I binding epitopes were screened regarding immunogenicity, allergenicity, and hydrophobicity via IEDB MHC-I immunogenicity tool (http://tools.iedb.org/immunogenicity/), AllerTOP v2.0, and Peptide2 (https://peptide2.com/N_peptide_hydrophobicity_hydrophilicity.php) online tools, respectively. Also, mouse MHC-II binding epitopes were further evaluated by antigenicity, allergenicity, IFN-γ, and IL-4 induction using VaxiJen v2.0, AllerTOP v2.0, IFNepitope (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/ifnepitope/), and IL4pred (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/il4pred/) servers, correspondingly.

Given human CTL epitopes, NetCTL 1.2 web server was used, which predicts CTL epitopes with respect to 12 major MHC supertypes (threshold 0.75). In order to cover up to 90% of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) in the global population, we utilized top five frequent supertypes (A1, A2, A3, A24, and B7) for CTL epitope prediction [45]. Similar to mouse MHC-I epitopes, screening was performed regarding immunogenicity, allergenicity, and hydrophobicity. Moreover, human HTL epitopes were predicted using IEDB MHC-II tool with respect to full-HLA reference set, along with antigenicity, allergenicity, IFN-γ, and IL-4 induction analyses.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of T. gondii TrOWP

The outputs of VaxiJen v2.0 and ANTIGENpro servers demonstrated that the protein possesses antigenic feature with 0.8769 (threshold 0.5) and 0.879297 scores, respectively. Moreover, AllerTOP v2.0 and AlgPred predictions revealed no allergenic traits, no IgE specific epitopes, and no MEME/MAST motifs in the sequence. Protein solubility results using SOLpro and Protein-Sol servers showed that TrOWP is highly soluble with 0.623441 and 0.810 scores, respectively. Based on ProtParam server outputs, the protein contained 236 amino acid residues, molecular weight of 25579.15, and a relatively acidic speculated pI of 4.85. There were more negatively charged (Asp + Glu) residues in the sequence (38), than positively charged residues (Arg + Lys) (27). Estimated half-life was calculated to be 30 h (mammalian reticulocytes, in vitro), >20 h (yeast, in vivo), and >10 h (E. coli, in vivo). Also, the protein was stable (instability index: 29.51), moderately thermotolerant (54.24), and hydrophilic nature (GRAVY score: -0.758).

3.2. Transmembrane Domain, Signal Peptide, and PTM Sites of TrOWP

The output of TMHMM server determined no transmembrane domains in the protein sequence. Of note, there were several PTM sites in the sequence. NetPhos 3.1 server predicted 26 phosphorylation sites (14 serine, 9 threonine, and 3 tyrosine), while 13 acetylation sites were present in the sequence, according to GPS-PAIL tool. However, there was no N-glycosylation and palmitoylation sites in TrOWP. SignalP-5.0 server revealed the presence of a standard signal peptide (Sec/SPI) in the sequence with a 0.9967 likelihood.

3.3. Secondary and Tertiary Structure Prediction

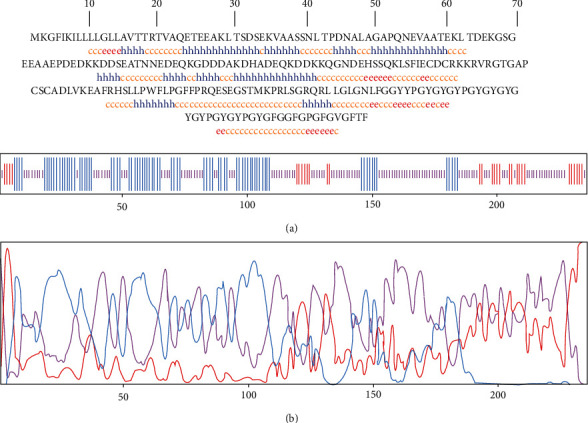

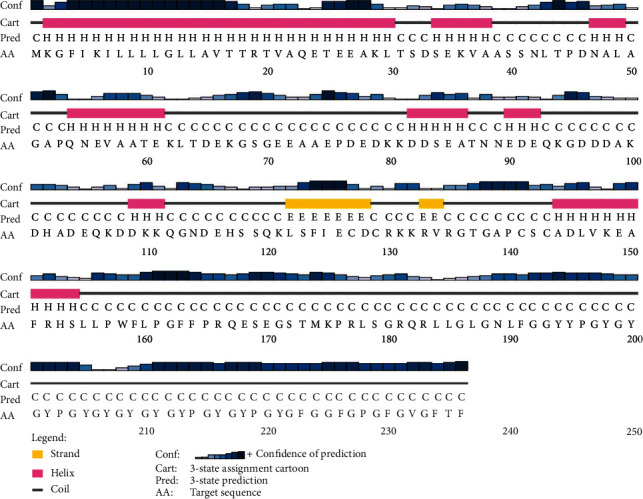

Based on GOR IV and PSIPRED output, three secondary structure constituents were present in the sequence, including 128 (54.24%) random coil and 78 (33.05%) alpha helix as well as 30 (12.71%) extended strand. The graphical representation of secondary structure prediction by GORV and PSIPRED servers is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Secondary structure prediction for TrOWP using GOR IV web server. (a) Sequence-based prediction results indicated that 54.24%, 33.05%, and 12.71% of the sequence are dedicated to the random coil (yellow C), alpha helix (blue H), and extended strand (red E), respectively. (b) Graphical illustration of the secondary structure by GOR IV server.

Figure 2.

Graphical illustration of secondary structure prediction of TrOWP using PSIPRED server.

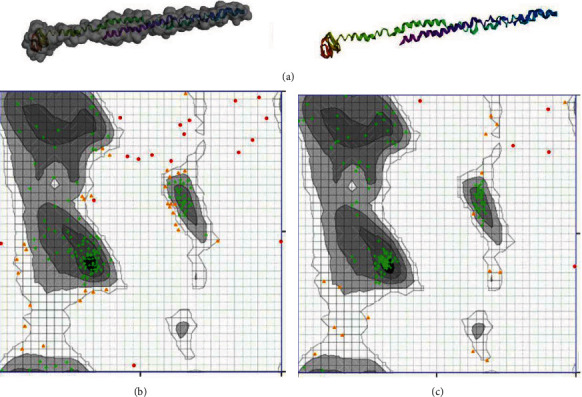

Subsequent homology modelling analysis by I-TASSER server predicted five tertiary models based on top 10 threading templates using LOMETS threading approach. Each predicted model is appointed a C-score as confidence index, ranging between -5 and 2, where higher C-score values indicate a higher confidence in prediction. Provided models using I-TASSER had a C-score from -4.3 to -5. Model number 1 with C-score -4.3, estimated TM-score 0.26 ± 0.08 and estimated RMSD of 16.3 ± 3.0 Å, was chosen for further refining and validations (Figure 3(a)).

Figure 3.

Protein 3D modelling and validation. (a) The final tertiary model of the TrOWP gathered following homology modelling by I-TASSER web server, as shown in ribbon and surface. (b) Ramachandran plot analysis of the initial model showed 74.33%, 16.57%, and 9.09% of the residues in favored, allowed, and outlier areas, respectively. (c) After refinement, 88.77%, 8.56%, and 2.67% of the residues are in favored, allowed, and outlier regions, respectively.

3.4. Tertiary Structure Refinement and Validations

GalaxyRefine server output was shown as five refined models. Based on qualifying parameters of GDTHA (0.8951), RMSD (0.579), MolProbity (2.789), Clash score (34.5), Poor rotamers (1.1), and Rama favored (79.5), model number 2 was the best refined model. Subsequently, two web servers validated the refining process, including Zlab Ramachandran analysis and ERRAT. The overall quality factor of ERRAT in crude model was 71.491, which was improved to 74.561 after refinement. Moreover, Ramachandran plot analysis demonstrated that 74.33%, 16.57%, and 9.09% of residues are located in favored, allowed, and outlier regions, respectively. Following refinement, these were improved to 88.77%, 8.56%, and 2.67% in favored, allowed, and outlier areas, correspondingly (Figures 3(b) and 3(c)).

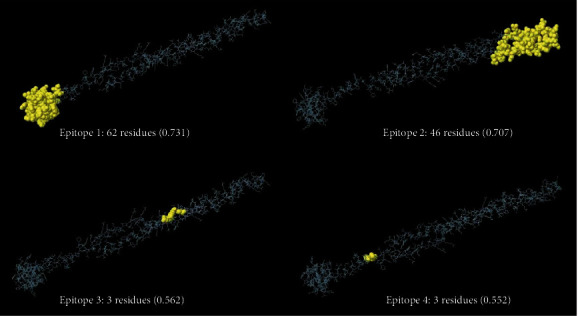

Prediction of Linear and Conformational B-Cell Epitopes

Multistep linear B-cell epitope prediction revealed nine shared peptides among three web servers (BCPREDS, ABCpred, and SVMTriP) with high antigenicity score and good water solubility and without allergenic properties (Table 1 and Supplementary File 1). Also, the linear B-cell epitopes predicted on the basis of physico-chemical parameters are tabulated in Table 2. In addition, ElliPro tool of the IEDB server demonstrated four conformation epitopes in the protein sequence, with length and scores as follows: (i) 62 residues (0.731), (ii) 46 residues (0.707), (iii) 3 residues (0.562), and (iv) 3 residues (0.552) (Figure 4).

Table 1.

The final screening of shared linear B-cell epitopes from T. gondii tyrosine-rich oocyst wall protein.

| B-cell epitopes | Antigenicity | Allergenicity | Solubility |

|---|---|---|---|

| YPGYGYGYPGYGYG | 0.2095 | No | Poor |

| EEAAEPDE | 0.7107 | No | Good |

| VAASSNLTPDNA | 0.5596 | Yes | Poor |

| EPDEDKKDDS | 1.4261 | No | Good |

| QGNDEHSSQ | 1.7231 | No | Good |

| TNNEDEQ | 1.8297 | No | Good |

| AGAPQNEVAAT | 1.1823 | No | Good |

| PRLSGRQRLLGL | 0.2650 | No | Good |

| SQKLSFIECDCRK | 0.8220 | No | Good |

Table 2.

Specific B-cell linear epitopes of T. gondii tyrosine-rich oocyst wall protein based on different physico-chemical parameters predicted by the Bcepred web server.

| Physico-chemical parameter | B-cell epitopes |

|---|---|

| Hydrophilicity | VAQETEEAKLTSDSEKVA, AGAPQNE, ECDCRKKR, PRQESEGSTMK |

| Flexibility | EEAKLTSDSE, EKLTDEKGSG, IECDCRKKRVRG, GFFPRQESEGSTMKPRLSGRQ |

| Accessibility | TRTVAQETEEAKLTSDSEKV, SNLTPDN, ECDCRKKRVRGTG, KEAFRHS, FFPRQESEGSTMKPRLSGRQR |

| Turns | EATNNEDE, GNDEHSSQ |

| Exposed surface | QETEEAK, EKLTDEK, ECDCRKKRVRGT |

| Polarity | VAQETEEAKLTS, IECDCRKKRVRGTG, VKEAFRHSL, FPRQESEGS, KPRLSGRQR |

| Antigenic propensity | GFIKILLLLGLL, KLSFIECDCR, FRHSLLPWFLP |

Figure 4.

Predicted conformational B-cell epitopes of TrOWP by ElliPro tool of IEDB analysis resource. Length and score of each protein are provided.

Prediction of Mouse and Human CTL/HTL Epitopes

Mouse MHC-I epitopes were predicted with respect to six MHC-I alleles (H2-Db, H2-Dd, H2-Kb, H2-Kd, H2-Kk, and H2-Ld) with subsequent immunogenicity, allergenicity, and hydrophobicity analyses (Table 3). Also, mouse MHC-II binding peptides were predicted against three MHC-II alleles (H2-IAb, H2-IAd, and H2-IEd) with subsequent screenings (Table 4). Specific human CTL and HTL epitopes are, also, provided in Tables 5 and 6, respectively.

Table 3.

Mouse specific MHC-I epitopes predicted by CTLpred server with subsequent screening for immunogenicity, allergenicity, and hydrophobicity.

| Mouse MHC-I alleles | T-cell peptide | Immunogenicity score | Allergenicity | Hydrophobicity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2-Db (MHC-I) | AASSNLTPDNAL | -0.17199 | Yes | 50 |

| ALAGAPQNEVAA | 0.10695 | No | 66.67 | |

| FFPRQESEGSTM | -0.11546 | No | 33.33 | |

| H2-Dd (MHC-I) | FGGFGPGFGVGF | 0.38454 | No | 50 |

| KGFIKILLLLGL | 0.06992 | Yes | 66.67 | |

| RHSLLPWFLPGF | 0.24324 | No | 66.67 | |

| H2-Kb (MHC-I) | KGFIKILLLLGL | 0.06992 | Yes | 66.67 |

| RHSLLPWFLPGF | 0.24324 | No | 66.67 | |

| FGGFGPGFGVGF | 0.38454 | No | 50 | |

| H2-Kd (MHC-I) | FFPRQESEGSTM | -0.11546 | No | 33.33 |

| GYPGYGYPGYGF | 0.09408 | No | 25 | |

| GFGPGFGVGFTF | 0.37342 | No | 50 | |

| H2-Kk (MHC-I) | QESEGSTMKPRL | -0.39637 | Yes | 25 |

| EEAKLTSDSEKV | -0.51403 | Yes | 25 | |

| DLVKEAFRHSLL | -0.01925 | Yes | 50 | |

| H2-Ld (MHC-I) | HSLLPWFLPGFF | 0.3799 | No | 75 |

| YPGYGYGYGYGY | 0.11446 | No | 8.33 | |

| EAFRHSLLPWFL | 0.18378 | No | 66.67 |

Table 4.

Mouse specific MHC-II epitopes predicted by IEDB server with subsequent screening for antigenicity and allergenicity as well as IFN-γ and IL-4 induction.

| Mouse MHC-II alleles | T-cell peptide | Antigenicity | Allergenicity | IFN-γ induction | IL-4 induction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Score | Result | Score | ||||

| H2-IAb (MHC-II) | PDNALAGAPQNEVAA | 1.2048 | Yes | Negative | -0.6321 | Negative | -1.02 |

| TPDNALAGAPQNEVA | 0.9905 | No | Negative | -0.6006 | Negative | -1.01 | |

| RKKRVRGTGAPCSCA | 2.1439 | No | Negative | -0.249 | Positive | 0.39 | |

| H2-IAd (MHC-II) | IKILLLLGLLAVTTR | 0.6131 | No | Negative | 4 | Negative | -0.75 |

| LTSDSEKVAASSNLT | 1.2417 | Yes | Negative | 2 | Negative | -0.38 | |

| SDSEKVAASSNLTPD | 1.0754 | No | Negative | 2 | Negative | -0.41 | |

| H2-IEd (MHC-II) | SFIECDCRKKRVRGT | 1.8125 | No | Negative | -0.3691 | Positive | 0.29 |

| CDCRKKRVRGTGAPC | 1.7682 | No | Positive | 1 | Positive | 0.29 | |

| ADLVKEAFRHSLLPW | 0.7519 | Yes | Positive | 1 | Positive | 0.23 | |

Table 5.

Human specific MHC-I epitopes predicted by CTLpred server with subsequent screening for immunogenicity, allergenicity, and hydrophobicity.

| Human MHC class I supertype | CTL epitopes | Immunogenicity score | Allergenicity | Hydrophobicity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 supertype | GLGNLFGGY | 0.15229 | No | 33.33 |

| CADLVKEAF | -0.0594 | No | 55.56 | |

| ATEKLTDEK | -0.08154 | Yes | 22.22 | |

| A2 supertype | LLLLGLLAV | 0.0213 | No | 88.89 |

| KLTSDSEKV | -0.3295 | Yes | 22.22 | |

| LLAVTTRTV | 0.19494 | Yes | 55.56 | |

| GLLAVTTRT | 0.17551 | No | 44.44 | |

| FLPGFFPRQ | 0.27558 | No | 66.67 | |

| A3 supertype | TMKPRLSGR | -0.16102 | No | 33.33 |

| GLGNLFGGY | 0.15229 | No | 33.33 | |

| A24 supertype | GYGYPGYGF | 0.04506 | No | 22.22 |

| GFIKILLLL | -0.07048 | No | 77.78 | |

| YYPGYGYGY | 0.07548 | No | 11.11 | |

| RLLGLGNLF | 0.03966 | Yes | 55.56 | |

| RHSLLPWFL | 0.16924 | No | 66.67 | |

| B7 supertype | YPGYGFGGF | 0.19888 | No | 33.33 |

| LPWFLPGFF | 0.26546 | No | 88.89 | |

| KPRLSGRQR | -0.14756 | No | 22.22 | |

| RVRGTGAPC | 0.14714 | Yes | 33.33 | |

| APQNEVAAT | 0.14813 | No | 55.56 | |

| APCSCADLV | -0.1874 | No | 55.56 | |

| SGRQRLLGL | -0.04936 | No | 33.33 |

Table 6.

Human specific MHC-II epitopes predicted by IEDB server using HLA reference set with subsequent screening for antigenicity and allergenicity as well as IFN-γ and IL-4 induction.

| Human MHC-II allele | HTL epitope | Method | Percentile rank | Antigenicity | Allergenicity | IFN-γ induction | IL-4 induction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Score | Result | Score | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1∗01 : 01 | FIKILLLLGLLAVTT | Consensus (comb.lib./smm/nn) | 0.10 | 0.8754 | No | Negative | 61 | Negative | -0.74 |

| HLA-DRB1∗15 : 01 | FIKILLLLGLLAVTT | Consensus (smm/nn/sturniolo) | 0.93 | 0.8754 | No | Negative | 61 | Negative | -0.74 |

| HLA-DPA1∗01 : 03/DPB1∗04 : 01 | LVKEAFRHSLLPWFL | NetMHCIIpan | 0.95 | 0.8487 | Yes | Negative | -0.0405 | Positive | 0.02 |

| HLA-DPA1∗02 : 01/DPB1∗05 : 01 | MKGFIKILLLLGLLA | Consensus (comb.lib./smm/nn) | 1.10 | 0.9498 | No | Negative | 71 | Negative | -0.74 |

| HLA-DPA1∗01 : 03/DPB1∗02 : 01 | HSLLPWFLPGFFPRQ | Consensus (comb.lib./smm/nn) | 1.40 | 1.2901 | No | Positive | 1 | Negative | 0.15 |

| HLA-DPA1∗01 : 03/DPB1∗04 : 01 | KEAFRHSLLPWFLPG | NetMHCIIpan | 1.50 | 0.7021 | Yes | Positive | 0.0844 | Negative | 0.07 |

| HLA-DPA1∗03 : 01/DPB1∗04 : 02 | GFIKILLLLGLLAVT | Consensus (comb.lib./smm/nn) | 1.60 | 0.4212 | No | Negative | 71 | Negative | -0.74 |

| HLA-DPA1∗01 : 03/DPB1∗04 : 01 | HSLLPWFLPGFFPRQ | NetMHCIIpan | 1.60 | 1.2901 | No | Positive | 1 | Negative | 0.15 |

| HLA-DPA1∗03 : 01/DPB1∗04 : 02 | MKGFIKILLLLGLLA | Consensus (comb.lib./smm/nn) | 1.60 | 0.9498 | No | Negative | 1 | Negative | -0.74 |

| HLA-DQA1∗01 : 01/DQB1∗05 : 01 | FRHSLLPWFLPGFFP | Consensus (comb.lib./smm/nn) | 1.90 | 1.5483 | No | Negative | -0.0952 | Negative | 0.14 |

| HLA-DPA1∗01 : 03/DPB1∗04 : 01 | EAFRHSLLPWFLPGF | NetMHCIIpan | 2.00 | 0.9177 | Yes | Negative | -0.0048 | Negative | 0.08 |

| HLA-DQA1∗01 : 01/DQB1∗05 : 01 | HSLLPWFLPGFFPRQ | Consensus (comb.lib./smm/nn) | 2.00 | 1.2901 | No | Positive | 1 | Negative | 0.15 |

| HLA-DPA1∗02 : 01/DPB1∗01 : 01 | RHSLLPWFLPGFFPR | Consensus (comb.lib./smm/nn) | 2.30 | 1.1923 | No | Positive | 0.0806 | Negative | 0.15 |

| HLA-DRB1∗03 : 01 | KLSFIECDCRKKRVR | Consensus (smm/nn/sturniolo) | 2.40 | 1.1250 | No | Negative | -0.3371 | Positive | 0.29 |

4. Discussion

One-third of the global population is affected by the apicomplexan protist, T. gondii, and its clinical significance is conspicuous in pregnant women and immunocompromised patients [46, 47]. Despite over decades of research in the field of toxoplasmosis vaccination using various antigens and immunization platforms, a human vaccine is still lacking [10]. In the molecular era, the combination of mathematical algorithms with outstanding large depository of biological data has yielded the interdisciplinary bioinformatics science. “Immunoinformatics” is a subdivision aimed at characterization of novel vaccine candidates, their biophysical features, immunogenic epitopes, and evaluation of intermolecular interactions as well as the dynamics of host responses to injected vaccine through in silico approaches. Some advantages are anticipated using this novel approach, including (i) time- and cost-effectiveness; (ii) precisely targeted, durable immune response with desired polarity in cellular components; and (iii) abolition of unfavorable responses through specific, epitope-based construct design [48]. The present in silico study was done to identify the bioinformatics features of the poorly known Toxoplasma TrOWP, along with identification of potential CTL, HTL, and B-cell epitopes for future vaccine design.

Toxoplasma oocysts are shed via felid's feces as unsporulated form, where under optimum climatic conditions (20-25°C, moist soil) turn into infective sporulated oocysts [49]. Early studies demonstrated that T. gondii infection was lacking in cat-free islands, emphasizing the significance of oocysts in transmission dynamics and infection maintenance [50, 51]. Such infective stages are highly resistant to a wide range of temperatures (-20°C to +37°C) [52], salinity up to 15 ppt (parts per thousand) [53] and chemical inactivation agents used in water treatment supplies [54], whereas they succumb to temperatures over 45°C as well as desiccation [55–57]. Therefore, oocysts ring the alarm of a possible health hazard in regions where drinking water treatment plants are only based on chemical disinfection without further filtration [54]. Insights into structural conformation of oocyst wall components would represent us the key for such a large extent of environmental resistance by oocysts [14, 15]. This intuition was mostly gained from pioneering investigations on the oocyst walls of other apicomplexan members, including Cryptosporidium parvum and Eimeria species [13]. Proteomics analyses during the last decade led to the identification of approximately 225 proteins in fractions of T. gondii oocyst wall, with the predominance of PAN-domain containing, cysteine or tyrosine rich proteins [15, 58, 59]. The latter were initially discovered in Eimeria maxima within macrogametes type-2 wall forming bodies and inner layer of oocyst wall, showing high rate of conservation across Eimeria species [60–62]. Detailed transcriptomic and proteomic information suggested that such proteins are different in T. gondii, localizing in both layers of oocyst walls [59, 63]. Here, a TrOWP of T. gondii was further characterized using a set of bioinformatics web servers.

The basic features of a good vaccine candidate are antigenicity and lack of allergenicity; accordingly, TrOWP was showed to have adequate antigenic scores via analysis by VaxiJen v2.0 (0.8769) and ANTIGENpro (0.879297) web servers. It was, also, considered as a nonallergen protein by AllerTOP v2.0 server, without IgE specific epitopes and MEME/MST motifs, as demonstrated by AlgPred server. The ProtParam server revealed some of the critical physico-chemical parameters of the protein, so that this 236 amino acid proteins possessed a MW of 25.57 kDa, suggesting adequate immunogenicity value, since molecules over 5-10 kDa are strong immunogens [64]. The pI is defined as the pH at which net charge turns zero, which for this protein was relatively acidic in nature (4.85). Negatively charged residues (Asp + Glu) were prevalent in the sequence than positively charged residues (Arg + Lys). According to instability index of 29.51 and aliphatic index of 54.24, TrOWP was a stable and moderately thermotolerant molecule. In fact, higher aliphatic index demonstrates higher tolerability to vast range of temperatures [65]. Moreover, the protein was highly hydrophilic in nature, as evidenced by a negative GRAVY score (-0.785). Protein solubility is another important factor in purification experiments. Two web servers, SOLpro a d Protein-Sol, substantiated that TrOWP is a highly soluble molecule with 0.623441 and 0.810 scores, respectively. Totally, such biophysical characteristics are fundamental for further extraction/purification purposes in the molecular laboratory experiments.

Synthesized proteins may be directed towards cellular secretory pathway for several purposes such as excretory/secretory antigen, virulence factor, and/or structural molecule; hence, they are highlighted by a signal peptide [66]. In the present in silico study, SignalP-5.0 web tool assisted us for detecting three types of signal peptide: “standard secretory signal peptides transported by the Sec translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Sec/SPI), lipoprotein signal peptides transported by the Sec translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase II (Sec/SPII), and Tat signal peptides transported by the Tat translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (TAT/SPI)” [29]. TrOWP only possessed a standard signal peptide with the probability of 0.9967. Crude synthesized proteins undergo several enzymatic modifications, including glycosylation, acetylation, palmitoylation, and phosphorylation, totally known as PTMs [67]. Each modification has its own function, such as protein half-life alteration (glycosylation), signal transduction (phosphorylation), membrane anchoring (acetylation), and enhanced protein hydrophobicity (palmitoylation) [68]. Among PTMs examined in the present study, 26 phosphorylation sites and 13 acetylation sites were only predicted in TrOWP, whereas palmitoylation and N-glycosylation were lacking. In general, prediction of PTMs, in particular for eukaryotic proteins, is beneficial for choosing appropriate expression hosts for recombinant protein production purposes. Complex protein structures can be produced efficiently using yeast- and mammal-based expression machineries [68]. It is believed that “the presence of hydrogen bonds in a polypeptide chain between amino hydrogen and carboxyl oxygen represents the secondary structure, with frequent α-helices and β-structures” [69]. Moreover, tertiary or 3D structure of a protein is defined by the involved bonds and their interactions. High hydrogen-bond energy among α-helices and β-structures strongly maintains the protein conformation and, therefore, strengthens the possible interaction with antibodies [70]. Secondary structure prediction using two web servers, GOR IV and PSIPRED, determined the predominance of random coil (54.24%), followed by alpha helix (33.05%) and extended strand (12.71%). In the next step, I-TASSER tool of the Zhang Lab automatically generated high-quality 3D models using TrOWP amino acid sequence. “To select the final models, I-TASSER uses SPICKER program to cluster all the decoys based on the pair-wise structure similarity, and report up to five models which corresponds to the five largest structure clusters and a C-score of higher value signifies a model with a high confidence” [71]. Here, model number 1 was the best-fit model, based on the C-score of -4.3, estimated TM-score of 0.26 ± 0.08, and estimated RMSD of 16.3 ± 3.0 Å. Subsequently, GalaxyRefine server was used to establishment and rehashing side chains, in order to improve the global quality of the structure. The outputs of this server for the selected model were including GDTHA (0.8951), RMSD (0.579), MolProbity (2.789), Clash score (34.5), Poor rotamers (1.1), and Rama favored (79.5). ERRAT and Ramachandran analyses, also, confirmed the quality of the refined model in comparison with the initial model.

Upon oocyst challenge, the gut mucosal barriers are the first place that host body senses the parasite through innate lymphoid cell (ILC) types 1 and 3 [72]. Hence, ILC1 secretes IFN-γ and tissue necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), while ILC3 activates CD4+-dependent T-cell responses in lamina propria. Consequently, sensing the infection through the so-called toll-like receptors (TRLs) would summon macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) to the infection site, where they produce a Th1-type cytokine, IL-12, to more elicit T CD4+ and T CD8+ cells. Furthermore, natural killer (NK) cells are stimulated to secrete another Th1-type cytokine, IFN-γ, which is totally required to limit the proliferation of parasites. Additionally, a Th-2 response and IL-4 production is a vital marker for B-cell propagation and differentiation as specific humoral response. On [9] this bases, specific CTL (CD8+), HTL (CD4+) and linear B-cell epitopes of TrOWP were predicted using various web servers. Regarding linear B-cell epitopes, a cross-checking approach was performed using BCPREDS, ABCpred, and SVMTriP servers to find common epitopic regions in the protein sequence. The final epitopes were further screened with respect to antigenicity, allergenicity, and water solubility. Therefore, the following six peptides were qualified as the best linear B-cell epitopes: “EEAAEPDE,” “TNNEDEQ,” “EPDEDKKDDS,” “QGNDEHSSQ,” “AGAPQNEVAAT,” and “SQKLSFIECDCRK.” Human CTL epitopes were predicted in context of the most frequent MHC-I supertypes (A1, A2, A3, A24, and B7) to cover large number of global population. As well, mouse CTL epitopes were predicted with respect to six mouse MHC-I alleles (H2-Db, H2-Dd, H2-Kb, H2-Kd, H2-Kk, and H2-Ld). All of these peptides were screened regarding immunogenicity, allergenicity, and hydrophobicity. Among human CTL epitopes, “LPWFLPGFF” (B7 supertype) and “FLPGFFPRQ” (A2 supertype) possessed high immunogenicity and hydrophobicity indices, without allergenic traits. Regarding mouse CTL peptides, “RHSLLPWFLPGF” along with “ALAGAPQNEVAA” qualified as best-ranked epitopes. Moreover, prediction of human HTL epitopes was done with respect to HLA reference set of IEDB; accordingly, “HSLLPWFLPGFFPRQ” and “RHSLLPWFLPGFFPR” were two antigenic, nonallergenic HTL peptides (VaxiJen score: 1.2901 vs. 1.1923) with potent capacity for IFN-γ induction. Also, “KLSFIECDCRKKRVR” was a highly antigenic MHC-II binding epitope with probable potential for IL-4 induction. With respect to mouse HTL epitopes, “CDCRKKRVRGTGAPC” was a highly antigenic (VaxiJen score: 1.7682), nonallergen IFN-γ and IL-4 inducer. As well, “RKKRVRGTGAPCSCA” and “SFIECDCRKKRVRGT” (VaxiJen score: 2.1439 vs. 1.8125) were two mouse MHC-II binding epitopes, which could efficiently induce IL-4 cytokine.

5. Conclusion

In spite of over three decades of research in the field of vaccination against toxoplasmosis, finding the most efficient antigen(s) and immunization platform is still a global health challenge. Computer-aided tools assist us to identify immunostimulant regions of a given antigen and better design multiepitope-based vaccine candidates for improving immunization. Previously, several surface and/or excretory/secretory antigens of T. gondii were evaluated using bioinformatics tools, while lack of studies on oocyst wall proteins leads us to select T. gondii TrOWP. The present study investigated the bioinformatics properties of TrOWP and its potent immunogenic mouse and human CTL/HTL epitopes to show its potential as a vaccine candidate. It was substantiated that TrOWP was a highly antigenic, nonallergenic, and soluble protein with several B-cell-specific and MHC-binding peptides in mouse and human, which highlights its significance for future vaccinology studies to prevent Toxoplasma infection as alone or multiepitope formulations in experimental models.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1. Specific linear B-cell epitopes of T. gondii Tyrosine-rich Oocyst Wall Protein predicted by the BCPREDS web server (Threshold 75%). Table 2. Specific linear B-cell epitopes of T. gondii Tyrosine-rich Oocyst Wall Protein predicted by the ABCpred web server (Threshold 0.75%). Table 3. Specific linear B-cell epitopes of T. gondii Tyrosine-rich Oocyst Wall Protein predicted by the SVMTriP web server.

References

- 1.McLeod R., Cohen W., Dovgin S., Finkelstein L., Boyer K. M. Toxoplasma gondii . Elsevier; 2020. Human Toxoplasma Infection; pp. 117–227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan A. H., Noordin R. Serological and molecular rapid diagnostic tests for toxoplasma infection in humans and animals. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases . 2020;39(1):19–30. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03680-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nayeri T., Sarvi S., Moosazadeh M., Daryani A. Global prevalence of _Toxoplasma gondii_ infection in the aborted fetuses and ruminants that had an abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Veterinary Parasitology . 2021;290, article 109370 doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2021.109370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatam-Nahavandi K., Calero-Bernal R., Rahimi M. T., et al. _Toxoplasma gondii_ infection in domestic and wild felids as public health concerns: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports . 2021;11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89031-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nosrati M. C., Ghasemi E., Shams M., et al. Toxoplasma gondii ROP38 protein: Bioinformatics analysis for vaccine design improvement against toxoplasmosis. Microbial Pathogenesis . 2020;149, article 104488 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robert-Gangneux F., Dardé M.-L. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews . 2012;25(2):264–296. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05013-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunay I. R., Gajurel K., Dhakal R., Liesenfeld O., Montoya J. G. Treatment of toxoplasmosis: historical perspective, animal models, and current clinical practice. Clinical Microbiology Reviews . 2018;31(4) doi: 10.1128/CMR.00057-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mévélec M., Lakhrif Z., Dimier-Poisson I. Key limitations and new insights into the Toxoplasma gondii parasite stage switching for future vaccine development in human, livestock, and cats. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology . 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.607198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasai M., Yamamoto M. Innate, adaptive, and cell-autonomous immunity against _Toxoplasma gondii_ infection. Experimental & Molecular Medicine . 2019;51(12):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J.-L., Zhang N.-Z., Li T.-T., He J.-J., Elsheikha H. M., Zhu X.-Q. Advances in the Development of Anti- Toxoplasma gondii Vaccines: Challenges, Opportunities, and Perspectives. Trends in Parasitology . 2019;35(3):239–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiszczynska-Sawicka E., Gatkowska J. M., Grzybowski M. M., Daugonska H., Hemphill A. Veterinary vaccines against toxoplasmosis. Parasitology . 2014;141(11):1365–1378. doi: 10.1017/S0031182014000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezaei F., Sarvi S., Sharif M., et al. A systematic review of Toxoplasma gondii antigens to find the best vaccine candidates for immunization. Microbial Pathogenesis . 2019;126:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freppel W., Ferguson D. J., Shapiro K., Dubey J. P., Puech P.-H., Dumètre A. Structure, composition, and roles of the Toxoplasma gondii oocyst and sporocyst walls. The Cell Surface . 2019;5:p. 100016. doi: 10.1016/j.tcsw.2018.100016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumètre A., Dubey J. P., Ferguson D. J., Bongrand P., Azas N., Puech P.-H. Mechanics of the Toxoplasma gondii oocyst wall. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 2013;110(28):11535–11540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308425110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fritz H. M., Bowyer P. W., Bogyo M., Conrad P. A., Boothroyd J. C. Proteomic analysis of fractionated Toxoplasma oocysts reveals clues to their environmental resistance. PLoS One . 2012;7(1, article e29955) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhee D. B., Croken M. M., Shieh K. R., et al. toxoMine: an integrated omics data warehouse for toxoplasma gondii systems biology research. Database . 2015;2015 doi: 10.1093/database/bav066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kardani K., Bolhassani A., Namvar A. An overview ofin silicovaccine design against different pathogens and cancer. Expert Review of Vaccines . 2020;19(8):699–726. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2020.1794832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doytchinova I. A., Flower D. R. VaxiJen: a server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinformatics . 2007;8(1):p. 4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnan C. N., Zeller M., Kayala M. A., et al. High-throughput prediction of protein antigenicity using protein microarray data. Bioinformatics . 2010;26(23):2936–2943. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimitrov I., Bangov I., Flower D. R., Doytchinova I. AllerTOP v. 2—a server for in silico prediction of allergens. Journal of Molecular Modeling . 2014;20(6) doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma N., Patiyal S., Dhall A., Pande A., Arora C., Raghava G. P. AlgPred 2.0: an improved method for predicting allergenic proteins and mapping of IgE epitopes. Briefings in Bioinformatics . 2021;22(4) doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magnan C. N., Randall A., Baldi P. SOLpro: accurate sequence-based prediction of protein solubility. Bioinformatics . 2009;25(17):2200–2207. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hebditch M., Carballo-Amador M. A., Charonis S., Curtis R., Warwicker J. Protein–Sol: a web tool for predicting protein solubility from sequence. Bioinformatics . 2017;33(19):3098–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook . Springer; 2005. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta R., Jung E., Brunak S. NetNGlyc 1.0 server: prediction of N-glycosylation sites in human proteins . DTU Bioinformatics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren J., Wen L., Gao X., Jin C., Xue Y., Yao X. CSS-Palm 2.0: an updated software for palmitoylation sites prediction. Protein Engineering, Design & Selection . 2008;21(11):639–644. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blom N., Gammeltoft S., Brunak S. Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites1. Journal of Molecular Biology . 1999;294(5):1351–1362. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng W., Wang C., Zhang Y., et al. GPS-PAIL: prediction of lysine acetyltransferase-specific modification sites from protein sequences. Scientific Reports . 2016;6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep39787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen H. Protein Function Prediction: Methods and Protocols . Springer; 2017. Predicting Secretory Proteins with SignalP; pp. 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garnier J., Gibrat J.-F., Robson B. GOR method for predicting protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence, Methods Enzymol . Elsevier; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchan D. W., Jones D. T. The PSIPRED protein analysis workbench: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Research . 2019;47(W1):W402–W407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J., Yan R., Roy A., Xu D., Poisson J., Zhang Y. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nature Methods . 2015;12(1):7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Majid M., Andleeb S. Designing a multi-epitopic vaccine against the enterotoxigenic _Bacteroides fragilis_ based on immunoinformatics approach. Scientific Reports . 2019;9(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55613-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shams M., Nourmohammadi H., Basati G., Adhami G., Majidiani H., Azizi E. Leishmanolysin gp63: Bioinformatics evidences of immunogenic epitopes in Leishmania major for enhanced vaccine design against zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked . 2021;24, article 100626 doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2021.100626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heo L., Park H., Seok C. GalaxyRefine: protein structure refinement driven by side-chain repacking. Nucleic Acids Research . 2013;41(W1):W384–W388. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asghari A., Majidiani H., Fatollahzadeh M., Nemati T., Shams M., Azizi E. Insights into the biochemical features and immunogenic epitopes of common bradyzoite markers of the ubiquitous Toxoplasma gondii. Infection, Genetics and Evolution . 2021;95, article 105037 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.105037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asghari A., Nourmohammadi H., Majidiani H., Shariatzadeh S. A., Shams M., Montazeri F. _In silico_ analysis and prediction of immunogenic epitopes for pre- erythrocytic proteins of the deadly Plasmodium falciparum. Infection, Genetics and Evolution . 2021;93, article 104985 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nourmohammadi H., Javanmardi E., Shams M., et al. Multi-epitope vaccine against cystic echinococcosis using immunodominant epitopes from EgA31 and EgG1Y162 antigens. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked . 2020;21, article 100464 doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2020.100464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou A. Q., O'Hern C. S., Regan L. Revisiting the Ramachandran plot from a new angle. Protein Science . 2011;20:1166–1171. doi: 10.1002/pro.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Majidiani H., Soltani S., Ghaffari A. D., Sabaghan M., Taghipour A., Foroutan M. In-depth computational analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase 3 ofToxoplasma gondiiprovides promising targets for vaccination. Clinical and Experimental Vaccine Research . 2020;9(2):146–158. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2020.9.2.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saha S., Raghava G. P. S. Prediction of continuous B-cell epitopes in an antigen using recurrent neural network. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics . 2006;65(1):40–48. doi: 10.1002/prot.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao B., Zheng D., Liang S., Zhang C. Immunoinformatics . Springer; 2020. SVMTriP: a method to predict B-cell linear antigenic epitopes; pp. 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El‐Manzalawy Y., Dobbs D., Honavar V. Predicting linear B-cell epitopes using string kernels. Journal of Molecular Recognition: An Interdisciplinary Journal . 2008;21(4):243–255. doi: 10.1002/jmr.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ponomarenko J., Bui H.-H., Li W., et al. ElliPro: a new structure-based tool for the prediction of antibody epitopes. BMC Bioinformatics . 2008;9(1):p. ???. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sidney J., Peters B., Frahm N., Brander C., Sette A. HLA class I supertypes: a revised and updated classification. BMC Immunology . 2008;9(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foroutan-Rad M., Khademvatan S., Majidiani H., Aryamand S., Rahim F., Malehi A. S. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in the Iranian pregnant women: A systematic review and meta -analysis. Acta Tropica . 2016;158:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z.-D., Liu H.-H., Ma Z.-X., et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in immunocompromised patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Microbiology . 2017;8:p. 389. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parvizpour S., Pourseif M. M., Razmara J., Rafi M. A., Omidi Y. Epitope-based vaccine design: a comprehensive overview of bioinformatics approaches. Drug Discovery Today . 2020;25(6):1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torrey E. F., Yolken R. H. Toxoplasma oocysts as a public health problem. Trends in Parasitology . 2013;29(8):380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dubey J., Rollor E., Smith K., Kwok O., Thulliez P. Low seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in feral pigs from a remote island lacking cats. The Journal of Parasitology . 1997;83(5):839–841. doi: 10.2307/3284277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wallace G. D., Marshall L., Marshall M. Cats, rats, and toxoplasmosis on a small Pacific island. American Journal of Epidemiology . 1972;95(5):475–482. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dumètre A., Aubert D., Puech P.-H., Hohweyer J., Azas N., Villena I. Interaction forces drive the environmental transmission of pathogenic protozoa. Applied and Environmental Microbiology . 2012;78(4):905–912. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06488-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindsay D. S., Collins M. V., Mitchell S. M., et al. Sporulation and survival of toxoplasma gondii oocysts in seawater. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology . 2003;50(s1):687–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones J., Dubey J. Waterborne toxoplasmosis - Recent developments. Experimental Parasitology . 2010;124(1):10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dubey J. Toxoplasma gondii oocyst survival under defined temperatures. The Journal of Parasitology . 1998;84(4):862–865. doi: 10.2307/3284606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lélu M., Villena I., Dardé M.-L., et al. Quantitative estimation of the viability of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in soil. Applied and Environmental Microbiology . 2012;78(15):5127–5132. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00246-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yilmaz S. M., Hopkins S. H. Effects of different conditions on duration of infectivity of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts. Journal of Parasitology . 1972;58(5):938–939. doi: 10.2307/3286589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Possenti A., Fratini F., Fantozzi L., et al. Global proteomic analysis of the oocyst/sporozoite of Toxoplasma gondiireveals commitment to a host-independent lifestyle. BMC Genomics . 2013;14(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou D.-H., Wang Z.-X., Zhou C.-X., He S., Elsheikha H. M., Zhu X.-Q. Comparative proteomic analysis of virulent and avirulent strains ofToxoplasma gondiireveals strain-specific patterns. Oncotarget . 2017;8(46):80481–80491. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferguson D., Belli S. I., Smith N. C., Wallach M. G. The development of the macrogamete and oocyst wall in Eimeria maxima: immuno-light and electron microscopy. International Journal for Parasitology . 2003;33(12):1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mai K., Smith N. C., Feng Z.-P., et al. Peroxidase catalysed cross-linking of an intrinsically unstructured protein via dityrosine bonds in the oocyst wall of the apicomplexan parasite, Eimeria maxima. International Journal for Parasitology . 2011;41(11):1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walker R. A., Ferguson D. J., Miller C. M., Smith N. C. Sex and Eimeria: a molecular perspective. Parasitology . 2013;140(14):1701–1717. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013000838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fritz H. M., Buchholz K. R., Chen X., et al. Transcriptomic analysis of toxoplasma development reveals many novel functions and structures specific to sporozoites and oocysts. PLoS One . 2012;7(2, article e29998) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Majidiani H., Dalimi A., Ghaffarifar F., Pirestani M., Ghaffari A. D. Computational probing of _Toxoplasma gondii_ major surface antigen 1 (SAG1) for enhanced vaccine design against toxoplasmosis. Microbial Pathogenesis . 2020;147, article 104386 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ikai A. Thermostability and aliphatic index of globular proteins. The Journal of Biochemistry . 1980;88(6):1895–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Can H., Alak S. E., Köseoğlu A. E., Döşkaya M., Ün C. Do _Toxoplasma gondii_ apicoplast proteins have antigenic potential? An in silico study. Computational Biology and Chemistry . 2020;84:p. 107158. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2019.107158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Walsh C. Posttranslational Modification of Proteins: Expanding Nature’s Inventory . Roberts and Company Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hansson M., Nygren P. A., Stahl S. Design and production of recombinant subunit vaccines. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry . 2000;32(2):95–107. doi: 10.1042/BA20000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shams M., Javanmardi E., Nosrati M. C., et al. Bioinformatics features and immunogenic epitopes of Echinococcus granulosus Myophilin as a promising target for vaccination against cystic echinococcosis. Infection, Genetics and Evolution . 2021;89, article 104714 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shaddel M., Ebrahimi M., Tabandeh M. R. Bioinformatics analysis of single and multi-hybrid epitopes of GRA-1, GRA-4, GRA-6 and GRA-7 proteins to improve DNA vaccine design against Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Parasitic Diseases . 2018;42(2):269–276. doi: 10.1007/s12639-018-0996-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roy A., Kucukural A., Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nature Protocols . 2010;5(4):725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spits H., Artis D., Colonna M., et al. Innate lymphoid cells -- a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nature Reviews Immunology . 2013;13(2):145–149. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1. Specific linear B-cell epitopes of T. gondii Tyrosine-rich Oocyst Wall Protein predicted by the BCPREDS web server (Threshold 75%). Table 2. Specific linear B-cell epitopes of T. gondii Tyrosine-rich Oocyst Wall Protein predicted by the ABCpred web server (Threshold 0.75%). Table 3. Specific linear B-cell epitopes of T. gondii Tyrosine-rich Oocyst Wall Protein predicted by the SVMTriP web server.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.