Abstract

Uveal melanoma (UM) and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) can occur sporadically and as a manifestation of BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome. We aimed to understand the prevalence of germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants in patients with UM and RCC. We reviewed patients managed at Cleveland Clinic between November 2003 and November 2019 who were diagnosed with UM and RCC. Charts were reviewed for demographic and cancer-related characteristics. RCC samples were tested for BAP1 protein expression using immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, and testing for germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants was performed as part of routine clinical care. Thirteen patients were included in the study. The average age at diagnosis of UM was 61.3 years. Seven patients underwent fine-needle aspiration biopsy for prognostic testing of UM (low risk =5, high risk =2). Twelve patients were treated with plaque radiation therapy, and 3 patients developed metastatic disease requiring systemic therapy. The median time to diagnosis of RCC from time of diagnosis of UM was 0 months. RCC samples were available for 7 patients for BAP1 IHC staining (intact =6, loss =1). All patients underwent nephrectomy (total = 3, partial = 8, unknown =2), and 1 received systemic therapy for metastatic RCC. Six patients underwent germ line BAP1 genetic testing. Of these, 1 patient was heterozygous for a pathogenic variant of BAP1 gene: c.1781-1782delGG, p.Gly594Valfs*48. The overall prevalence of germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants in our study was high (1/6; 17%; 95% CI 0–46%). Patients with UM and RCC should be referred for genetic counseling to discuss genetic testing.

Keywords: Germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants, Uveal melanoma, Renal carcinoma

Introduction

Patients with uveal melanoma (UM) often have a history of another cancer [1, 2, 3]. The prevalence of a second malignancy in patients with UM may be similar to that observed in the age-matched general population (9.6 vs. 2.8–17%) [1, 2, 3, 4]. However, the occurrence of a second malignancy may be due to cancer predisposition syndromes, environmental exposures, and late side effects of treatment exposure [4].

In the case of UM, BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome (BAP1-TPDS) may play a role and increase the risk of developing BAP1-TPDS defining cancers which include cutaneous melanoma (CM), malignant mesothelioma (MMe), renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) [5, 6, 7, 8]. The development of RCC has been described in 0.6–4.8% of all patients with UM, and such an occurrence may be sporadic, related to BAP1-TPDS, or some other genetic predisposition not yet discovered [5, 6, 7].

Loss-of-function variants of BAP1 gene (BRCA-associated protein 1) in UM [9] and RCC [10, 11] can be inherited or occur sporadically. BAP1 is a deubiquitinating protein involved in regulation of gene expression [9]. Loss-of-function variants of the germ line BAP1 gene result in BAP1-TPDS, which includes the previously mentioned neoplasms along with nonmalignant BAP1-inactivated melanocytic tumor (BIMT) [6, 7, 12, 13]. RCC in BAP1-TPDS is usually of a clear cell subtype [10]. The rate of the germ line BAP1 pathogenic variant in UM and RCC is similar, 1.6 and 1.2%, respectively [10, 14]. On the contrary, somatic mutations of the BAP1 gene and loss of function of BAP1 protein are more frequent in UM (42%) than in RCC (15%) [15]. Other genes such as PBRM1 are more commonly mutated than BAP1 in RCC, which are not observed in UM [11]. Given that synchronous and metachronous UM and RCC may occur sporadically or be related to BAP1-TPDS, we sought to assess the prevalence of germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants in patients with UM and RCC.

Case Presentation

This study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. Patients seen at Cleveland Clinic between November 2005 and November 2019 who were diagnosed with UM and RCC were included. Charts were reviewed for demographic and cancer-related characteristics. Personal and family history was noted for BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers. These were defined as the following malignancies: CM, MMe, BCC, UM, and RCC. BIMT was also considered a feature of BAP-TPDS.

Prognostic testing was performed on UM samples when available. Classes 1A and 1B by gene expression profiling and disomy 3 by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification were considered low risk for the recurrence, while class 2 by gene expression profiling and monosomy 3 by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification were considered high risk. RCC samples were tested for nuclear BAP1 protein expression using immunohistochemical staining. BAP1 mouse monoclonal antibody was used on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. An antigen-antibody complex was localized using the OptiView detection Kit® (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). BAP1 protein expression was scored as intact when nuclear BAP1 staining was present and as loss when nuclear BAP1 staining was absent [16]. Normal cells with intact staining in the background of each sample served as the internal control. Testing for germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants was performed as part of routine clinical care after referral to genetic counseling at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory using next-generation sequencing of DNA obtained from salivary or blood samples.

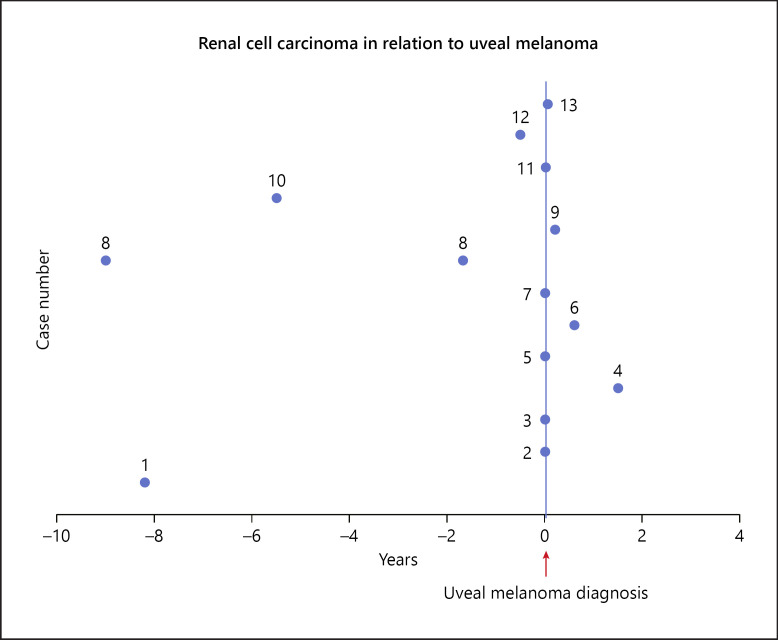

Thirteen patients were included in the study. The average age at diagnosis of UM was 61.3 years. Four patients had a known history of RCC, while remaining 9 patients were incidentally diagnosed with RCC on staging imaging for UM (Fig. 1). Patient 8 had a diagnosis of bilateral metachronous RCC. Median time to diagnosis of RCC from diagnosis of UM was 0 months. Most patients were male (8/13), with low-risk UM (5/13) and RCC of clear cell subtype (9/13) (Table 1). Remaining RCC subtypes included papillary (1/13) and unclassified (1/13), and the subtype was not known for 2 patients. RCC samples were available for 7 patients for immunohistochemical staining. Of these, only 1 patient showed loss of expression of nuclear BAP1 protein. Twelve patients were treated with plaque radiation therapy, and 3 patients developed metastatic disease requiring systemic therapy. All patients underwent nephrectomy (total = 3, partial = 8, unknown = 2). Six patients underwent testing for the germ line BAP1 gene, and only 1 carried a pathogenic variant. The overall prevalence of germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants in this population was 17% (1/6; 95% CI 0–46%).

Fig. 1.

Time to diagnosis of RCC in relation to UM. RCC, renal cell carcinoma; UM, uveal melanoma.

Table 1.

Results of germ line BAP1 genetic testing

| Group | N = 13 | Patients with germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 1 (12.5) |

| Female | 5 | 0 (0) |

| UM prognostic class | ||

| Unavailable | 6 | 1 (17) |

| Low risk | 5 | 0 (0) |

| High risk | 2 | 0 (0) |

| RCC subtype | ||

| Clear cell | 9 | 1 (11) |

| Papillary | 1 | 0 (0) |

| Unclassified | 1 | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 (0) |

| RCC BAP1 stain status | ||

| Unavailable | 6 | 0 (0) |

| Intact | 6 | 0 (0) |

| Loss | 1 | 1 (100) |

| Personal history of cancers* | ||

| Present | 5 | 1 (20) |

| Absent | 8 | 0 (0) |

| Family history of BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers | ||

| Present | 1 | 1 (17) |

| Absent | 12 | 0 (0) |

| Family history of any cancer | ||

| Present | 5 | 1 (20) |

| Absent | 8 | 0 (0) |

UM was considered low risk for class 1a, 1b, and disomy 3 groups and was considered high risk for class 2 groups. Following cancers were considered BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers: UM, RCC, CM, MMe, and BCC. UM, uveal melanoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; BAP1-TPDS, BAP1-tumor predisposition syndrome; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CM, cutaneous melanoma; MMe, malignant mesothelioma. * Other than UM, and RCC.

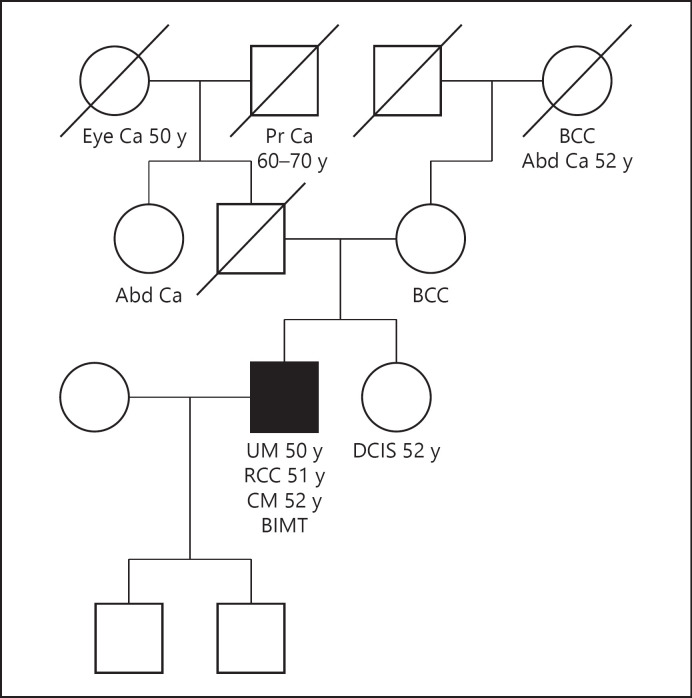

Patient 6 was heterozygous for a pathogenic variant of the germ line BAP1 gene (Fig. 2). This was a 50-year-old male patient with incidentally diagnosed RCC on staging imaging for UM. The patient had multiple nevi on examination and was later diagnosed with BIMT and CM. He had a family history of BCC in his mother and maternal grandmother, eye cancer of unknown type in his paternal grandmother, ductal carcinoma in situ in his sister, and abdominal cancer of an unknown type in his paternal aunt. The patient had a low-risk UM, RCC of clear cell subtype, and loss of BAP1 protein expression on the RCC stain.

Fig. 2.

Pedigree of patient 6. The patient had a personal and family history of multiple BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers. Family history of other cancers included DCIS in his sister and abdominal cancer of unknown type in his paternal aunt and maternal grandmother. The patient was heterozygous for the pathogenic variant of the germ line BAP1 gene c.1781_1782delGG. UM, RCC, BIMT, and CM in self; BCC in his mother and maternal grandmother. RCC, renal cell carcinoma; UM, uveal melanoma; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; TPDS, tumor predisposition syndrome; CM, cutaneous melanoma; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; BIMT, BAP1-inactivated melanocytic tumor.

The patient was heterozygous for the variant of the BAP1 gene: c.1781_1782delGG, p.Gly594Valfs*48. To our knowledge, this variant has not been previously reported and is expected to be pathogenic as it results in premature protein termination. The patient also demonstrated somatic loss of heterozygosity of the BAP1 gene on a metastatic UM sample from the liver, suggesting that the tumor was related to BAP1 loss of function. The parents were not tested for germ line mutation. The patient was alive at the end of the follow-up with metastatic UM undergoing localized radiation therapy to the liver and systemic therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Patients with a family history of non-BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers did not harbor germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants (Table 1). At the end of the follow-up, 4 patients had developed UM metastasis and 1 patient from RCC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

| Patient, N0./sex/race | Age at dx, years, UM/RCC | UM prognostic testing | Initial UM treatment | RCC subtype | RCC BAP1 IHC status | Presence of germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants | Follow-up since UM diagnosis, months | UM mets | RCC mets | Cutaneous nevi/melanoma | Other cancers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/M/W | 49/41 | GEP 1B | Enucleation | CC | NK | Negative | 1 | NK | NK | Absent | Absent |

|

| |||||||||||

| 2/M/W | 66/65 | NK | Plaque | NK | NK | NK | 9 | Present | Absent | Absent | Absent |

|

| |||||||||||

| 3/F/W | 70/70 | NK | Plaque | UC | Intact | NK | 12 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Breast ca |

|

| |||||||||||

| 4/F/W | 68/69 | NK | Plaque | CC | Intact | NK | 157 | Absent | Absent | Absent | BCC |

|

| |||||||||||

| 5/M/W | 68/68 | MLPA disomy 3 | Plaque | CC | Intact | Negative | 49 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

|

| |||||||||||

| 6/M/W | 50/51 | NK | Plaque | CC | Loss | Positive | 168 | Present | Absent | Cutaneous nevi and melanoma present | Prostate ca BCC |

|

| |||||||||||

| 7/F/W | 76/76 | GEP 2 | Plaque | NK | NK | Negative | 33 | Present | Absent | Absent | Lung ca |

|

| |||||||||||

| 8/F/W | 60/51 | GEP 1A | Plaque | CC | Intact | Negative | 9 | Absent | Present | Absent | Absent |

|

| |||||||||||

| 9/M/W | 64/64 | GEP 2 | Plaque | Papillary | NK | NK | 34 | Present | Absent | Absent | Absent |

|

| |||||||||||

| 10/M/W | 59/53 | NK | Plaque | CC | Intact | NK | 44 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

|

| |||||||||||

| 11/M/W | 54/53 | GEP 1B | Plaque | CC | Intact | NK | 66 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

|

| |||||||||||

| 12/F/W | 60/55 | GEP 1B | Plaque | CC | NK | Negative | 62 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

|

| |||||||||||

| 13/M/W | 56/56 | NK | Plaque | CC | NK | NK | 5 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Chronic myeloid leukemia |

M, male; F, female; W, white; dx, diagnosis; UM, uveal melanoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; NK, not known; CC, clear cell; UC, unclassified; IHC, immunohistochemical; LOF, lost to follow-up; GEP, gene expression profiling; MLPA, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; ca, cancer.

Discussion

Several studies have reported the occurrence of UM and RCC in the same patients [15, 17]. Of these, only one study reports the prevalence of germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants in this patient population [17]. The study by Boru et al. evaluated the prevalence of germ line BAP1 mutation in patients with UM who were at high risk for hereditary cancer syndrome (age of diagnosis of UM <35 years, familial UM, and personal and/or family history of other BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers). The overall prevalence of germ line BAP1 mutation in their study was 4.7% (8/172). The prevalence of germ line BAP1 mutation in patients with familial UM and a personal or family history of RCC was 33% (1/3) [17]. None of the 13 patients with UM in the absence of familial UM had a germ line BAP1 mutation, while one of the 16 patients with UM and a family history of RCC and CM carried a germ line BAP1 mutation [17].

The point prevalence of UM in patients with germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants is estimated to be 2.8% (95% CI, 0.88−4.81%) [18], similar to the frequency of BAP1 germ line pathogenic variants in patients with UM of 2% (0.80–3.08) [8, 14, 19, 20, 21, 22], with higher frequency in studies that have selected a population either with familial UM and personal or family history of MMe, and CM (4.7–8.0%) [6, 17, 23]. The prevalence of germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants in our study of 17% (1/6) is even higher as patients in our study represent a selected sample of a high-risk population.

The patient positive for a germ line BAP1 pathogenic variant in our study had a personal and family history of other BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers in addition to UM and RCC. The remaining 5 patients without a personal or family history of other BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers did not harbor a germ line mutation. Of note, the patient's parents were not tested for germ line mutation; therefore, it is unclear whether the mutation was inherited. His mother and maternal grandmother both had BCC which are also considered as BAP1-TPDS-defining cancers.

It is clear that patients with UM and a personal and/or family history of more than one BAP1-TPDS-defining cancer should be tested for germ line BAP1 mutation, given the high prevalence of pathogenic variants in this population (∼38%) [17]. However, based on the small number of patients in our study, we cannot conclude if patients with UM and a personal history of RCC alone should routinely be tested for germ line mutations. UM and RCC may occur sporadically in these patients since UM and RCC are both more frequent in men older than >60 years [6, 24]. BAP1 stain of RCC and UM is also likely not helpful in identifying patients needing BAP1 germ line testing as the prevalence of germ line BAP1 mutation in these populations is much lower (∼1.6% for UM and 1.2% for RCC, respectively) [10, 14].

Furthermore, it is possible that other unidentified germ line mutations may be at play in patients with UM and RCC. However, even if germ line testing is not routinely performed in this population, these patients should be referred for genetic counseling for a thorough assessment of family history and identification of high-risk patients who warrant germ line testing. The small size of our study population and the inability to test all patients for germ line BAP1 mutation limit the validity of our results. A larger study is needed to define the true prevalence of germ line BAP1 pathogenic variants in patients with UM and RCC.

Conclusion

Patients with UM and RCC should be referred for genetic counseling for thorough assessment of family history and identification of high-risk patients who will benefit from genetic testing.

Statement of Ethics

Our research complies with the guidelines for human studies, and the research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol (17-1186) was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. Patients' consent was not required as the study was based on review of medical records.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Arun D Singh: one of the editors-in-chief of Ocular Oncology and Pathology. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author Contributions

Yusra F. Shao: primary contribution to acquisition and analysis of data, writing and revising the manuscript for approval of final version, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Meghan DeBenedictis: contribution to acquisition of patient data, critically revising, final approval of the manuscript, and agreement to be accountable for accuracy and integrity of the work.

Gabriella Yeaney: contribution to acquisition of patient data, critically revising, final approval of the manuscript, and agreement to be accountable for accuracy and integrity of the work.

Arun D. Singh: primary contribution to the conception of study design, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for intellectual content and accuracy, final approval of the published version of the manuscript, and agreement to be accountable for accuracy and integrity of the work.

References

- 1.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, Caldwell R, Cumming K, Earle JD, et al. Second primary cancers after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma: COMS Report No. 25. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005 May;123((5)):601–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heussen FM, Coupland SE, Kalirai H, Damato BE, Heimann H. Non-ocular primary malignancies in patients with uveal melanoma: the Liverpool experience. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016 Mar;100((3)):356–9. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Rahman MH, Pilarski R, Ezzat S, Sexton J, Davidorf FH. Cancer family history characterization in an unselected cohort of 121 patients with uveal melanoma. Fam Cancer. 2010 Sep;9((3)):431–8. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogt A, Schmid S, Heinimann K, Frick H, Herrmann C, Cerny T, et al. Multiple primary tumours: challenges and approaches, a review. ESMO Open. 2017;2((2)):e000172. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Rahman MH, Pilarski R, Cebulla CM, Massengill JB, Christopher BN, Boru G, et al. Germline BAP1 mutation predisposes to uveal melanoma, lung adenocarcinoma, meningioma, and other cancers. J Med Genet. 2011 Dec;48((12)):856–9. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walpole S, Pritchard AL, Cebulla CM, Pilarski R, Stautberg M, Davidorf FH, et al. Comprehensive study of the clinical phenotype of germline BAP1 variant-carrying families worldwide. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018 Dec 1;110((12)):1328–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilarski R, Cebulla CM, Massengill JB, Rai K, Rich T, Strong L, et al. Expanding the clinical phenotype of hereditary BAP1 cancer predisposition syndrome, reporting three new cases. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014 Feb;53((2)):177–82. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Repo P, Jarvinen RS, Jantti JE, Markkinen S, Tall M, Raivio V, et al. Population-based analysis of BAP1 germline variations in patients with uveal melanoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2019 Jul 15;28((14)):2415–26. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010 Dec 3;330((6009)):1410–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1194472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popova T, Hebert L, Jacquemin V, Gad S, Caux-Moncoutier V, Dubois-d'Enghien C, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to renal cell carcinomas. Am J Hum Genet. 2013 Jun 6;92((6)):974–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maher ER. Hereditary renal cell carcinoma syndromes: diagnosis, surveillance and management. World J Urol. 2018 Dec;36((12)):1891–8. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2288-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbone M, Ferris LK, Baumann F, Napolitano A, Lum CA, Flores EG, et al. BAP1 cancer syndrome: malignant mesothelioma, uveal and cutaneous melanoma, and MBAITs. J Transl Med. 2012 Aug 30;10:179. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilarski R, Rai K, Cebulla CM, Abdel-Rahman MH. BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome. In: Adam, MP, Ardinger, HH, Pagon, RA, Wallace, SE, Bean, LJH, Mirzaa, G, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet] Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2016. Oct 13, [updated 2020 Apr 9]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta MP, Lane AM, DeAngelis MM, Mayne K, Crabtree M, Gragoudas ES, et al. Clinical characteristics of uveal melanoma in patients with germline BAP1 mutations. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015 Aug;133((8)):881–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farley MN, Schmidt LS, Mester JL, Pena-Llopis S, Pavia-Jimenez A, Christie A, et al. A novel germline mutation in BAP1 predisposes to familial clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2013 Sep;11((9)):1061–71. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szalai E, Wells JR, Ward L, Grossniklaus HE. Uveal melanoma nuclear BRCA1-associated protein-1 immunoreactivity is an indicator of metastasis. Ophthalmology. 2018 Feb;125((2)):203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boru G, Grosel TW, Pilarski R, Stautberg M, Massengill JB, Jeter J, et al. Germline large deletion of BAP1 and decreased expression in non-tumor choroid in uveal melanoma patients with high risk for inherited cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2019 Sep;58((9)):650–6. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh N, Singh R, Bowen RC, Abdel-Rahman MH, Singh AD. Uveal melanoma in BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome: estimation of risk. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Dec 11;224:172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoude LG, Vajdic CM, Kricker A, Armstrong B, Hayward NK. Prevalence of germline BAP1 mutation in a population-based sample of uveal melanoma cases. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013 Mar;26((2)):278–9. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Njauw CN, Kim I, Piris A, Gabree M, Taylor M, Lane AM, et al. Germline BAP1 inactivation is preferentially associated with metastatic ocular melanoma and cutaneous-ocular melanoma families. PLoS One. 2012;7((4)):e35295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turunen JA, Markkinen S, Wilska R, Saarinen S, Raivio V, Tall M, et al. BAP1 germline mutations in finnish patients with uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2016 May;123((5)):1112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewens KG, Lalonde E, Richards-Yutz J, Shields CL, Ganguly A. Comparison of germline versus somatic BAP1 mutations for risk of metastasis in uveal melanoma. BMC Cancer. 2018 Nov 26;18((1)):1172. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5079-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rai K, Pilarski R, Boru G, Rehman M, Saqr AH, Massengill JB, et al. Germline BAP1 alterations in familial uveal melanoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2017 Feb;56((2)):168–74. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aronow ME, Topham AK, Singh AD. Uveal melanoma: 5-year update on incidence, treatment, and survival (SEER 1973-2013) Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2018 Apr;4((3)):145–51. doi: 10.1159/000480640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]