This cohort study assesses the association of single and accumulated geriatric deficits with health-related quality of life decline after treatment for head and neck cancer.

Key Points

Question

Are pretreatment geriatric deficits associated with quality of life after treatment for head and neck cancer?

Findings

In this cohort study including 283 patients, items of geriatric assessment within all domains (physical, functional, psychological, social) were associated with decline of quality of life after treatment. The accumulation of domains with geriatric deficits was a major significant factor for deterioration at both short- and long-term follow-up after treatment.

Meaning

Deficits in individual and accumulated geriatric domains are associated with decline in quality of life; this knowledge may aid decision-making, indicate interventions, and reduce loss of quality of life.

Abstract

Importance

Accumulation of geriatric deficits, leading to an increased frailty state, makes patients susceptible for decline in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) after treatment for head and neck cancer (HNC).

Objective

To assess the association of single and accumulated geriatric deficits with HRQOL decline in patients after treatment for HNC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Between October 2014 and May 2016, patients at a tertiary referral center were included in the Oncological Life Study (OncoLifeS), a prospective data biobank, and followed up for 2 years. A consecutive series of 369 patients with HNC underwent geriatric assessment at baseline; a cohort of 283 patients remained eligible for analysis, and after 2 years, 189 patients remained in the study. Analysis was performed between March and November 2020.

Interventions or Exposures

Geriatric assessment included scoring of the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27, polypharmacy, Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool, Activities of Daily Living, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), Timed Up & Go, Mini-Mental State Examination, 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale, marital status, and living situation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome measure was the Global Health Status/Quality of Life (GHS/QOL) scale of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. Differences between patients were evaluated using linear mixed models at 3 months after treatment (main effects, β [95% CI]) and declining course per year during follow-up (interaction × time, β [95% CI]), adjusted for baseline GHS/QOL scores, and age, sex, stage, and treatment modality.

Results

Among the 283 patients eligible for analysis, the mean (SD) age was 68.3 (10.9) years, and 193 (68.2%) were male. Severe comorbidity (β = −7.00 [−12.43 to 1.56]), risk of malnutrition (β = −6.18 [−11.55 to −0.81]), and IADL restrictions (β = −10.48 [−16.39 to −4.57]) were associated with increased GHS/QOL decline at 3 months after treatment. Severe comorbidity (β = −4.90 [−9.70 to −0.10]), IADL restrictions (β = −5.36 [−10.50 to −0.22]), restricted mobility (β = −6.78 [−12.81 to −0.75]), signs of depression (β = −7.08 [−13.10 to −1.06]), and living with assistance or in a nursing home (β = −8.74 [−15.75 to −1.73]) were associated with further GHS/QOL decline during follow-up. Accumulation of domains with geriatric deficits was a major significant factor for GHS/QOL decline at 3 months after treatment (per deficient domain β = −3.17 [−5.04 to −1.30]) and deterioration during follow-up (per domain per year β = −2.74 [−4.28 to −1.20]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this prospective cohort study, geriatric deficits were significantly associated with HRQOL decline after treatment for HNC. Therefore, geriatric assessment may aid decision-making, indicate interventions, and reduce loss of HRQOL.

Trial Registration

trialregister.nl Identifier: NL7839

Introduction

The presence of geriatric deficits is abundant in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC).1 Accumulation of these deficits is associated with frailty, defined as “a state of increased vulnerability to poor resolution of homeostasis after a stressor event, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes.”2(p752) It is believed that the HNC population is particularly prone to frailty,3 not only because of the aging population in general and therewith increasing proportion of older patients with cancer,4 but also because of the etiological factors for HNC, such as tobacco and alcohol abuse that may accelerate the process of aging,5,6 and tumor-related factors leading to impairments. This results in a heterogenic population burdened by geriatric deficits, which are often poorly recognized by oncologists.7

The underestimation of frailty may result in substantial risks for patients with HNC, like overtreatment and undertreatment. Frailty has extensively been associated with adverse treatment outcomes, such as surgical complications, increased length of hospital stay, and worse overall survival.8,9 Recently, it has been shown that frailty may be associated with decline in short- and long-term Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) as well.10,11 Yet specifically older patients find it more important to maintain adequate HRQOL rather than to target life extension or survival.12,13,14

Ideally, all patients would be subjected to a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) by a geriatrician, which is defined as “a multi-dimensional, interdisciplinary, diagnostic process to identify care needs, plan care, and improve outcomes of frail older people.”15(p474) However, owing to limited health care capacity and increasing numbers of patients, referring all patients to a geriatrician would be infeasible. Short frailty screening tools have been developed to select patients who may benefit from a CGA; however, they seem to lack specificity and predictive value.16 In between, a geriatric assessment (GA) at the department of the treating (head and neck) oncologist may offer a solution. Such a GA can be relatively short and led by a nurse, include various validated tests17 for relevant geriatric domains (physical, functional, psychological, socioenvironmental),15 and can be followed by interdisciplinary consultation with a geriatrician to indicate care needs.

In the present study, we aimed to identify which specific geriatric deficits exposed by a GA are associated with deterioration of HRQOL in patients treated for HNC. Furthermore, we were interested in the association between accumulation of domains with geriatric deficits and deterioration of HRQOL over time.

Methods

Study Design

The present study is a prospective observational study. Starting October 2014, all consecutively seen patients with HNC at the departments of Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery were asked to participate in the Oncological Life Study (OncoLifeS). OncoLifeS is a hospital-based oncological data biobank approved by the Medical Ethical Committee at the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) in Groningen, the Netherlands.18 Patients were enrolled after providing written informed consent. OncoLifeS is registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (trialregister.nl identifier: NL7839).

All patients diagnosed with any mucosal, salivary gland, and complex cutaneous malignant neoplasm of the head and neck area between October 2014 and May 2016 were included. Complex cutaneous malignant neoplasm was defined as either giant basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma stage II or higher, melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or neck metastasis of any cutaneous malignant neoplasm. Patients were excluded when palliative treatment or a nonstandard treatment regimen was carried out, or if baseline HRQOL was missing as a reference for further deterioration. Also, when tumor recurrence or death occurred during follow-up, patients were excluded from that moment onward.

At baseline, all patients underwent a GA, performed by one of the researchers or a dedicated nurse. The intention of the GA was purely observational, and treating oncologists were blinded to GA results at the time of patient presentation and treatment determination. However, unconsciously, increasing attention for frailty by nurses and physicians could have led to increased referral to a geriatrician, and this was not withheld from patients. Patients were treated according to (inter)national guidelines and discussed within a multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board. At baseline and during follow-up at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after treatment, questionnaires for HRQOL were collected.

Patient, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics

Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics were extracted from the OncoLifeS data biobank. The Union for International Cancer Control’s TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors (Seventh Edition)19 was used for staging of tumors.

Geriatric Assessment

The domain of physical health consisted of grading of comorbidity into none, mild, moderate, or severe using the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27 (ACE-27),20 identifying polypharmacy by medication count with 5 or more medications as a commonly used cutoff value,21 and screening for the risk of malnutrition with the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST).22 Functional status was evaluated by administration of patients’ Activities of Daily Living (ADL)23 and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL)24 and performing the Timed Up & Go (TUG) test25; 13.5 seconds was used as a cutoff value for restricted mobility.26 Psychological health was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) with respect to cognitive function27,28 and the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) for mood disorders.29 The socioenvironmental factors, marital status, (single vs in a relationship) and living situation (at home vs assisted or nursing home) were registered with a standardized questionnaire.

When a domain (either physical, functional, psychological, socioenvironmental) had 1 or more impairments on the GA items belonging to the corresponding domain, this was considered as a “domain with deficits.” The accumulation of domains with geriatric deficits refers to the sum of domains with geriatric deficits.

HRQOL

Patient-reported HRQOL using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) was collected either by mail or at the outpatient clinic.30 The Global Health Status/Quality of Life (GHS/QOL) scale was used as the primary outcome measure and was calculated according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual.31 Scores for the GHS/QOL scale range from 0 to 100. Higher score indicates better GHS/QOL.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 23.0 software (IBM). For descriptive statistics, continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR), and categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage).

Linear mixed models were used to analyze repeated GHS/QOL measurements and associated factors. Linear mixed models permit missing data without eliminating entire cases, therewith maintaining statistical power and limiting bias, which is ideal in large longitudinal data sets. Procedures were carried out according to methods developed by Shek and Ma32 and in a similar fashion as in the study by de Vries et al.10 The EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QOL score at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months was defined as the dependent variable, and the baseline GHS/QOL score was incorporated as an adjusting factor. The covariance type was set to unstructured. Fixed effects for each model that investigated “parameter” included time, parameter, parameter × time, and adjusting variables. Estimates (β coefficients) for parameter refer to the main effects, the difference in GHS/QOL between parameter(+) and parameter(−) patients at 3 months after treatment, and estimates for the interaction term parameter × time refer to the different slope in GHS/QOL between parameter(+) and parameter(−) patients with respect to 1 year. Thus, the β coefficient of parameter should be interpreted as the newly developed difference in GHS/QOL between patient categories at 3 months after treatment. Furthermore, the β coefficient of parameter × time should be interpreted as the increasing or decreasing difference in GHS/QOL between patient categories over time, and specifically refers to the increasing or decreasing difference per year. Estimates (β) are presented with 95% CIs and P values and were considered statistically significant if P < .05. All models were adjusted for age, sex, stage, treatment modality, and baseline differences in GHS/QOL by adding the corresponding variables and the baseline score as fixed effects to the model. For random effects, the intercept was included and covariance type was set to identity. The estimation method was set to maximum likelihood. If needed, model fit between models was compared using maximum likelihood ratio testing. Predicted values and SE of predicted values were saved for graphs. As a sensitivity analysis, estimates were compared between total study population and patients with complete follow-up.

Results

Study Population

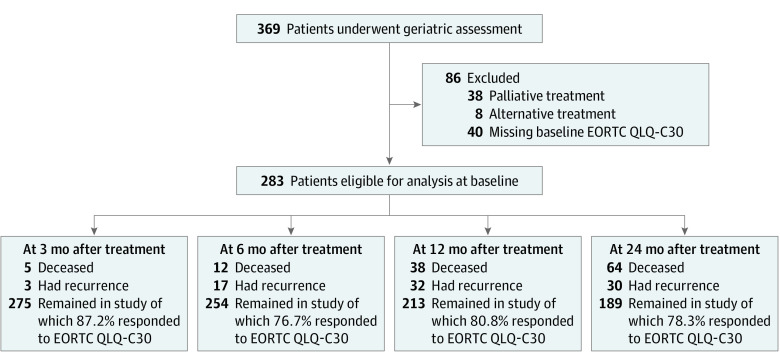

Between October 2014 and May 2016, 369 patients with suspicion of malignant neoplasm underwent GA. After exclusion, 283 patients remained eligible for analysis. Dropout owing to tumor recurrence or death during follow-up and questionnaire response rates are presented along with the exclusion process in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Inclusion and Follow-up of Study Patients.

EORTC QLQ-C30 indicates European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30.

Patient characteristics at baseline are summarized in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 68.3 (10.9) years and 193 (68.2%) were male. Included tumor sites were oral cavity (73 [25.7%]), nasal cavity and paranasal sinus (15 [5.3%]), nasopharynx (4 [1.4%]), oropharynx (52 [18.4%]), hypopharynx (9 [3.2%]), larynx (66 [23.3%]), salivary glands (5 [1.8%]), complex skin cancer (52 [18.4%]) and unknown primary tumor of the neck (7 [2.5%]). Most cancers were squamous cell carcinoma (244 [86.1%]), presenting in advanced stage (stage III-IV, 152 [54.7%]), and were treated by either primary surgery (158 [55.8%]), whether or not followed by postoperative (chemo)radiation, or primary (chemo)radiation (125 [44.2%]). Mean GHS/QOL by stage and treatment categories are shown in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Results of GA are included in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Geriatric Assessment of the Cohort Included at Baseline.

| Variable | No. (%) (n = 283) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Mean (SD) | 68.3 (10.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 68.2 (60.5-76.5) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 90 (31.8) |

| Male | 193 (68.2) |

| Reason for referral | |

| Primary tumor | 266 (94.0) |

| Recurrent tumor | 17 (6.0) |

| Tumor site | |

| Oral cavity | 73 (25.7) |

| Nasal cavity and paranasal sinus | 15 (5.3) |

| Nasopharynx | 4 (1.4) |

| Oropharynx | 52 (18.4) |

| Hypopharynx | 9 (3.2) |

| Larynx | 66 (23.3) |

| Salivary glands | 5 (1.8) |

| Skin | 52 (18.4) |

| Unknown primary tumor | 7 (2.5) |

| Histopathology | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 244 (86.1) |

| Other | 39 (13.9) |

| Stage | |

| I | 70 (25.2) |

| II | 56 (20.1) |

| III | 40 (14.4) |

| IV | 112 (40.3) |

| Primary treatment | |

| Surgery | 158 (55.8) |

| Postoperative radiotherapy | 54 (19.1) |

| Postoperative chemoradiation | 3 (1.1) |

| Radiotherapy | 83 (29.3) |

| Chemoradiation | 42 (14.8) |

| Physical | |

| Comorbidity (ACE-27) | |

| None | 62 (21.9) |

| Mild | 99 (35.0) |

| Moderate | 74 (26.1) |

| Severe | 48 (17.0) |

| Polypharmacy | |

| <5 Medications | 187 (66.1) |

| ≥5 Medications | 96 (33.9) |

| Malnutrition (MUST) | |

| No risk of malnutrition (<1) | 208 (78.8) |

| Medium to high risk of malnutrition (≥1) | 56 (21.2) |

| Functional | |

| ADL | |

| Independent (<1) | 252 (89.7) |

| Dependent (≥1) | 29 (10.3) |

| IADL | |

| No restrictions (<1) | 234 (82.7) |

| Restrictions (≥1) | 49 (17.3) |

| TUG | |

| Normal mobility (<13.5 s) | 237 (87.5) |

| Restricted mobility (≥13.5 s) | 34 (12.5) |

| Psychological | |

| Cognition (MMSE) | |

| No cognitive deficits (>24) | 249 (88.3) |

| Cognitive deficits (≤24) | 33 (11.7) |

| Depression (GDS-15) | |

| No signs of depression (<6) | 256 (91.1) |

| Signs of depression (≥6) | 25 (8.9) |

| Socioenvironmental | |

| Marital status | |

| In a relationship | 212 (75.2) |

| Single | 70 (24.8) |

| Living situation | |

| Independent | 248 (88.3) |

| Assisted or nursing home | 33 (11.7) |

Abbreviations: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; GDS-15, 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MUST, Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool; TUG, Timed Up & Go.

Association Between Geriatric Deficits and Deterioration of QOL

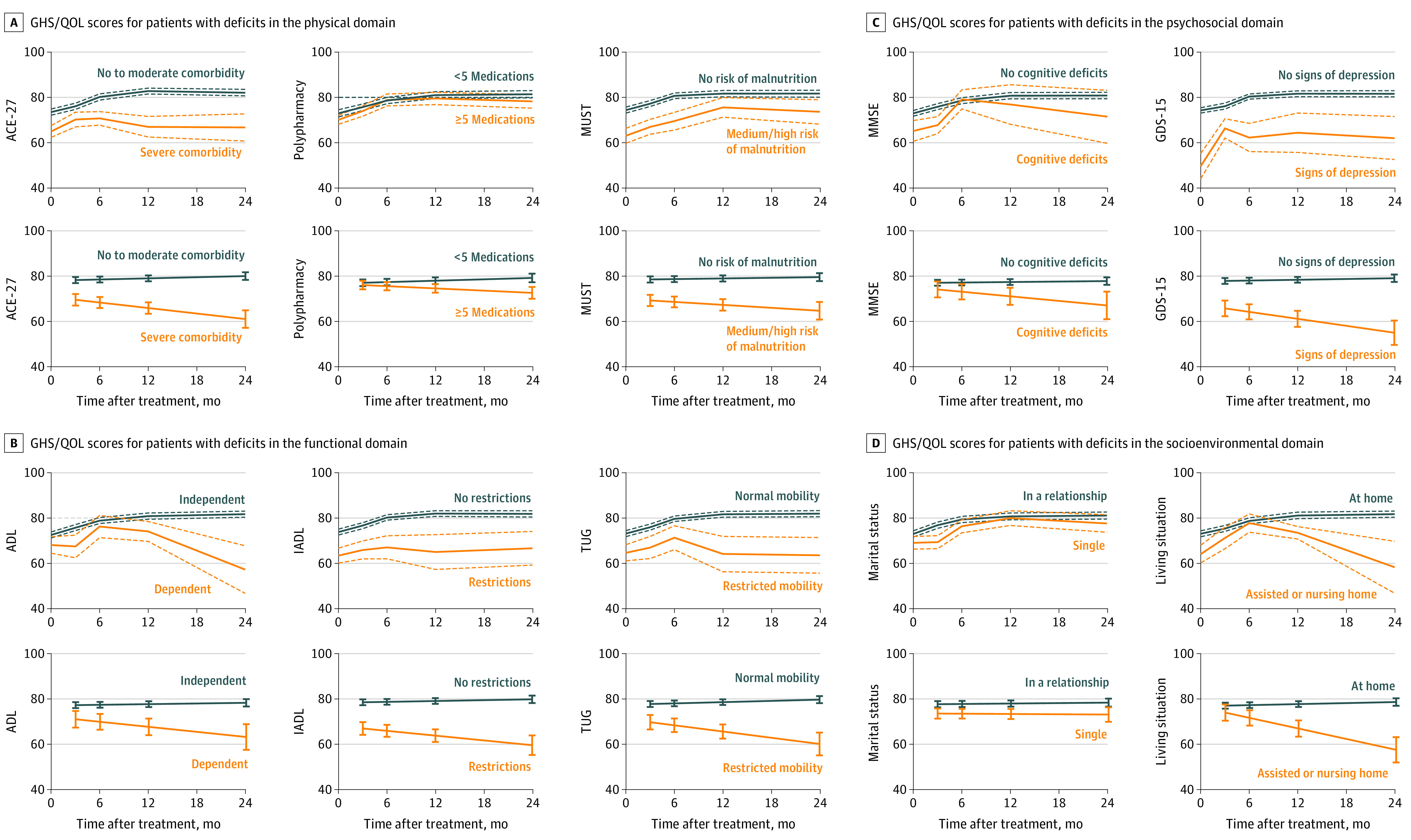

Mean GHS/QOL discriminated by deficits on GA is shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement and in Figure 2 (top row of graphs in each panel). Results of linear mixed models are presented in Table 2 with predicted values of these models in Figure 2 (second row of graphs in each panel).

Figure 2. Deterioration of Global Health Status/Quality of Life (GHS/QOL) Over Time for Patients With Geriatric Deficits.

The y-axes refer to the GHS/QOL score on the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. The x-axes refer to time in months, in which 0 refers to the pretreatment score. Figures in the first rows contain mean (solid lines) and SE (dashed lines) of the mean grouped by the binary outcome of the aforementioned geriatric assessment. Figures in the second rows contain predicted trajectories by the linear mixed effects models with corresponding SE (error bars) for the same geriatric assessment (estimates shown in Table 2).

ACE-27 indicates Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; GDS-15, 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MUST, Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool; TUG, Timed Up & Go.

Table 2. Linear Mixed Model Analysis of Associations Between Geriatric Assessment and Global Health Status/Quality of Life (GHS/QOL) Trajectory.

| Model parametersa | Estimate, β (95% CI)b | P valuec |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | ||

| ACE-27 | ||

| None to moderate | 0 [Reference] | |

| Severe | −7.00 (−12.43 to −1.56) | .01 |

| ACE-27 × time | ||

| None to moderate | 0 [Reference] | |

| Severe | −4.90 (−9.70 to −0.10) | .05 |

| Polypharmacy | ||

| <5 Medications | 0 [Reference] | |

| ≥5 Medications | −0.82 (−5.19 to 3.55) | .71 |

| Polypharmacy × time | ||

| <5 Medications | 0 [Reference] | |

| ≥5 Medications | −2.76 (−6.01 to 0.48) | .10 |

| MUST | ||

| No risk of malnutrition | 0 [Reference] | |

| Medium to high risk of malnutrition | −6.18 (−11.55 to −0.81) | .02 |

| MUST × time | ||

| No risk of malnutrition | 0 [Reference] | |

| Medium to high risk of malnutrition | −3.83 (−8.47 to 0.81) | .10 |

| Functional | ||

| ADL | ||

| Independent | 0 [Reference] | |

| Dependent | −7.17 (−14.91 to 0.57) | .07 |

| ADL × time | ||

| Independent | 0 [Reference] | |

| Dependent | −5.32 (−11.89 to 1.24) | .11 |

| IADL | ||

| No restrictions | 0 [Reference] | |

| Restrictions | −10.48 (−16.39 to −4.57) | .001 |

| IADL × time | ||

| No restrictions | 0 [Reference] | |

| Restrictions | −5.36 (−10.50 to −0.22) | .04 |

| TUG | ||

| Normal mobility | 0 [Reference] | |

| Restricted mobility | −6.09 (−12.78 to 0.60) | .07 |

| TUG × time | ||

| Normal mobility | [Reference] | |

| Restricted mobility | −6.78 (−12.81 to −0.75) | .03 |

| Psychological | ||

| MMSE | ||

| No cognitive deficits | 0 [Reference] | |

| Cognitive deficits | −0.13 (−7.35 to 7.08) | .97 |

| MMSE × time | ||

| No cognitive deficits | 0 [Reference] | |

| Cognitive deficits | −6.14 (−13.43 to 1.13) | .10 |

| GDS-15 | ||

| No signs of depression | 0 [Reference] | |

| Signs of depression | −4.22 (−11.33 to 2.91) | .25 |

| GDS-15 × time | ||

| No signs of depression | 0 [Reference] | |

| Signs of depression | −7.08 (−13.10 to −1.06) | .02 |

| Socioenvironmental | ||

| Marital status | ||

| In relationship | 0 [Reference] | |

| Single | −3.17 (−7.77 to 1.42) | .18 |

| Marital status × time | ||

| In relationship | 0 [Reference] | |

| Single | −0.98 (−4.74 to 2.78) | .61 |

| Living situation | ||

| At home | 0 [Reference] | |

| Assisted or nursing home | −2.62 (−10.55 to 5.30) | .52 |

| Living situation × time | ||

| At home | 0 [Reference] | |

| Assisted or nursing home | −8.74 (−15.75 to −1.73) | .02 |

| Deficit accumulation | ||

| No. of domains with deficits | −3.17 (−5.04 to −1.30) | .001 |

| No. of domains with deficits × time | −2.74 (−4.28 to −1.20) | .001 |

| Domains with deficits | ||

| <3 | 0 [Reference] | |

| ≥3 | −9.62 (−15.35 to −3.88) | .001 |

| Domains with deficits × time | ||

| <3 | 0 [Reference] | |

| ≥3 | −14.81 (−20.40 to −9.22) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; GDS-15, 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MUST, Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool; TUG, Timed Up & Go.

All models were adjusted for baseline GHS/QOL scores, and age, sex, stage, and treatment modality, and included an intercept and linear time.

Estimates (β coefficients) for normal model parameters refer to the main effects and can be interpreted as the novel difference in GHS/QOL after treatment at the 3 months’ follow-up interval between parameter categories. Estimates (β coefficients) for model parameters × time refer to the interaction term with time and can be interpreted as the increasing or decreasing difference in GHS/QOL between parameter categories over time with respect to 1 year. A domain with deficits was defined as a geriatric domain (either physical, functional, psychological, or socioenvironmental) with at least 1 impairment on the items of geriatric assessment belonging to the corresponding domain.

Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Within the physical domain, patients with severe comorbidities showed significantly worse GHS/QOL at 3 months after treatment (β = −7.00; 95% CI, −12.43 to −1.56) and further deterioration over time (β = −4.90; 95% CI, −9.70 to −0.10; Figure 2A). Polypharmacy was not associated with changes in GHS/QOL (Figure 2A). Patients at risk for malnutrition had worse GHS/QOL at 3 months after treatment (β = −6.18; 95% CI, −11.55 to −0.81), which did not significantly deteriorate further over time (Figure 2A).

On the functional domain, dependency on ADL was not significantly associated with worse GHS/QOL after treatment (Figure 2B). However, restrictions in IADL were significantly associated with worse GHS/QOL at 3 months after treatment (β = −10.48; 95% CI, −16.39 to −4.57) and with further decline in GHS/QOL (β = −5.36; 95% CI, −10.50 to −0.22; Figure 2B). Furthermore, although restricted mobility did not show significant decay in GHS/QOL at 3 months after treatment, it was significantly associated with deterioration of GHS/QOL over time (β = −6.78; 95% CI, −12.81 to −0.75; Figure 2B).

With respect to psychological domain, cognitive decline was not associated with worse GHS/QOL after treatment (Figure 2C). Signs of depression, however, were significantly associated with decay over time (β = −7.08; 95% CI, −13.10 to −1.06; Figure 2C).

On the socioenvironmental domain, marital status was not associated with GHS/QOL trajectories (Figure 2D), but living situation of the patient did show deteriorating trajectories for those in need for assistance at home or living in a nursing home (β = −8.74; 95% CI, −15.75 to −1.73; Figure 2D).

Association Between Accumulated Domains With Geriatric Deficits and Deterioration of QOL

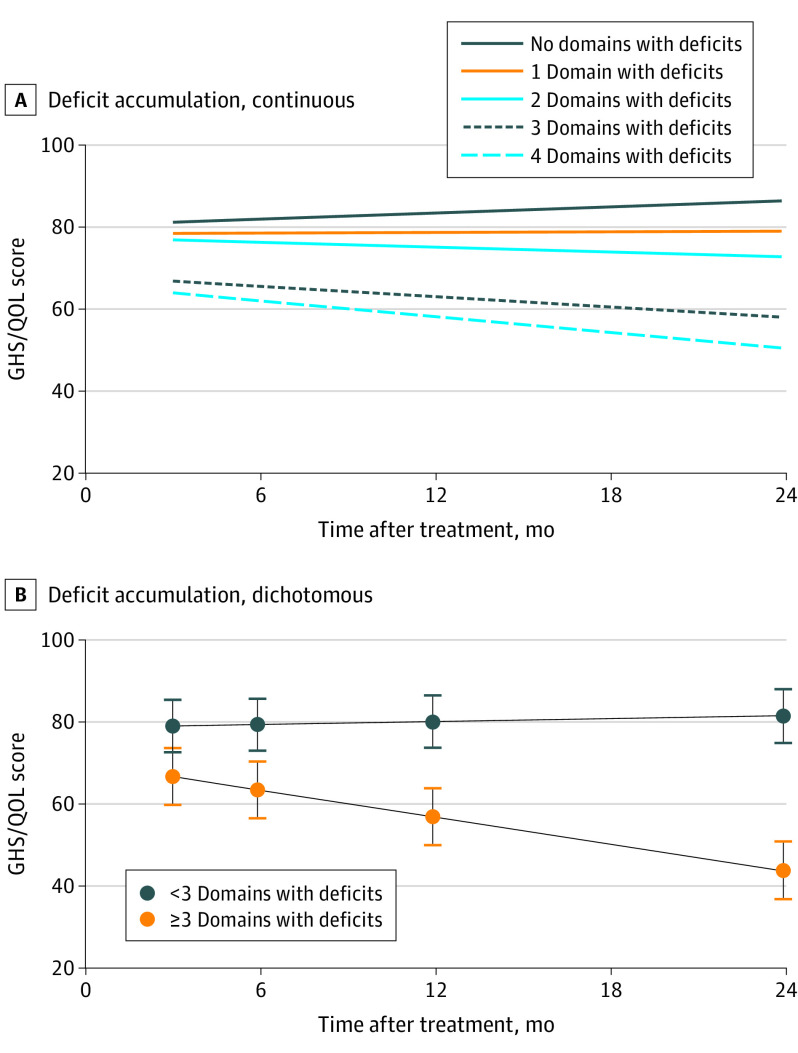

As a continuous factor, accumulation of domains with geriatric deficits resulted in a 3.17-point worse GHS/QOL score per domain with deficits at 3 months after treatment (β = −3.17; 95% CI, −5.04 to −1.30), and in a 2.74-point worse GHS/QOL score per additional domain with deficits per year (β = −2.74; 95% CI, −4.28 to −1.20; Table 2 and Figure 3A). Dichotomously, having more than 3 domains with deficits was associated with worse GHS/QOL after 3 months (β = −9.62; 95% CI, −15.35 to −3.88) and with further decline over time for each year (β = −14.81; 95% CI, −20.81 to −9.22; Table 2 and Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Predicted Global Health Status/Quality of Life (GHS/QOL) Trajectory for Patients With Accumulation of Domains With Deficits.

The y-axes refer to the predicted GHS/QOL score on the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 by linear mixed effect models (Table 2). The x-axes refer to time in months after treatment. A domain with deficits was defined as a geriatric domain (either physical, functional, psychological, or socioenvironmental) with at least 1 impairment on the items of geriatric assessment belonging to the corresponding domain. A, Increase in domains with deficits leads to increase in deterioration of GHS/QOL after treatment (continuous model). B, Using 3 or more domains with deficits as a cutoff shows the strongest deterioration of GHS/QOL.

Sensitivity Analysis

Loss to follow-up was higher in patients with geriatric deficits (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Comparison of estimates between the total study population and patients having complete follow-up revealed mostly minor and few major changes in estimates (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this prospective observational study, to our knowledge for the first time, the association of both individual geriatric deficits and accumulated domains with geriatric deficits with deterioration of HRQOL was evaluated during 2 years of follow-up after treatment for HNC. Within all geriatric domains (physical, functional, psychological, socioenvironmental), deficits were significantly associated with short- and long-term deterioration of HRQOL. The accumulation of deficits in geriatric domains was a very significant factor associated with deterioration of both short- and long-term HRQOL. These findings underscore the importance of multidomain GA of patients facing treatment for HNC.

The deficit accumulation model as an approach to describe frailty is well investigated in the field of geriatrics33,34,35,36,37 and describes frailty as “a multidimensional risk state that can be measured by the quantity rather than by the nature of health problems.”36(p67) Its multidimensional character makes it especially suitable for patients with HNC, as this population is burdened by such health problems.1,3 In this study, we have simplified this deficit accumulation model by dividing the GA items into the physical, functional, psychological, and socioenvironmental domains and when at least 1 of the corresponding GA items was impaired considered it as a domain with deficits. In a similar fashion, earlier work has shown that the accumulation of domains with deficits may be associated with a nearly 2-fold increase in risk for severe postoperative complications.38

In the present study, the most significant factor associated with deterioration of HRQOL after treatment for HNC was the accumulation of domains with geriatric deficits. The β coefficients can be interpreted as follows. For each additional domain with deficits, the GHS/QOL score was estimated to be worse (decrease of 3.17 points/domain, the β coefficient referring to the main effects) after 3 months already compared with patients without domains with deficits. Additionally, during 2 years of follow-up, GHS/QOL was estimated to decline further per additional domain with deficits per year (decrease of 2.74 points/domain/y, the β coefficient referring to the interaction term with time), compared with patients without geriatric deficits. These may sound like irrelevant differences on the 0 to 100 GHS/QOL scale; however, cumulatively after 2 years, this led to much larger decline (decrease of 7.96 points after 2 years) for patients with only 1 domain with deficits. Patients with HNC often have deficits in multiple domains. For instance, for a patient with severe comorbidities, signs of depression and living in social isolation (3 domains with deficits), decline may be devastating (decrease of 23.90 points after 2 years) compared with patients without geriatric deficits. Such declines on the EORTC QLQ-C30 GHS/QOL scale are regarded as a clinically highly significant deterioration by studies investigating patient-based, anchor-based, and distribution-based minimally important differences, which range from 5 to 15 points.39,40,41

In recent literature, it was already demonstrated that frailty, defined by short frailty screening instruments, is associated with decline in HRQOL after treatment for HNC.10 Another recent article by Thomas et al11 shows similar trends of HRQOL for frail HNC patients during twelve months of follow-up, and addresses that the frailty status itself may change over time as well. With approximately 30% to 70% of patients with HNC being frail according to such screening instruments and the fact that these tests lack specificity, however, this would be a suboptimal strategy to identify and treat frail patients.16 Therefore, multidomain assessment may identify deficits more specifically and reveal leads for pretreatment optimization.

Within the physical domain, estimates for patients with severe comorbidity indicate clinically important deterioration of HRQOL compared with patients with none to mild comorbidity. This is consistent with most earlier findings in HNC,42,43,44 but the literature is controversial on this, as 1 study showed equal HNC-specific QOL,45 and another study showed a converging HRQOL trend between comorbid and noncomorbid patients.46 Most studies, however, had less extensive follow-up and smaller sample size and did not evaluate the deteriorating trend of HRQOL with such detail. The difference in HRQOL between comorbid and noncomorbid patients may be explained by the fact that patients with comorbidities have increased risk of surgical complications, prolonged hospital stay, and readmission.47,48 Polypharmacy has not been investigated in HNC with respect to HRQOL before, but was significantly associated with physical QOL after treatment in a general oncology cohort.49 In the present study, there was a decreasing trend over time, but the estimate was neither significant nor clinically relevant. For malnutrition, being one of the best investigated physical conditions in HNC, estimates can be interpreted as clinically significant HRQOL decline, consistent with results from other studies.50,51,52

Level of functioning is implicitly associated with HRQOL. In the present study, ADL dependency demonstrated a statistically insignificant but clinically relevant deteriorating trend. Probably, the low number of patients with ADL restrictions affects this finding. Other studies in HNC used ADL as an outcome measure rather than as a factor.53,54 Though, in a general oncology population, ADL was significantly associated with baseline and posttreatment HRQOL; however, deterioration after treatment was not investigated.55 Instrumental Activities of Daily Living investigates more complex tasks, which makes it more sensitive to functional restrictions than ADL but also sensitive to cognitive decline.56 The diverging HRQOL trajectories for patients with and without IADL restrictions can be interpreted as clinically highly relevant. In contrast to results of the present study, earlier findings showing less decline for patients with impaired IADL during treatment and a stable course after treatment.57 Probably, the different time window (8 weeks vs 2 years) explains these different outcomes. The TUG encompasses a short, easy-to-administer mobility test in which the patient is asked to get up, walk 3 meters, turn around, walk back, and sit down. It is strongly associated with increased risk of surgical complications.58 Our finding that patients with limited mobility deteriorate over time has not been shown before in patients with HNC but seems clinically important given the size of the estimates. Another study investigating GA with respect to HRQOL in a heterogeneous oncology population showed similar findings.55

From the psychological domain, cognitive decline was not a statistically significant factor for HRQOL, although the estimate reveals a clinically relevant negative trend. Possibly, loss to follow-up of these patients and therewith underrepresentation leads to bias. Cognition has been shown to be associated with pretreatment HRQOL in patients with HNC59,60; however, the literature lacks longitudinal studies. Depression rates in our cohort were similar to earlier findings in patients with HNC.61 The association of depression with HRQOL decline has already thoroughly been investigated and is in line with the significant and clinically important difference that was found in our study.62

In the social domain, marital status was not associated with decline in HRQOL, but living situation was a strong statistically and clinically significant factor. There is no consensus in the literature. Some studies found social support to be associated with better HRQOL,63,64 but others did not.65,66 Different definitions of variables, lack of use of validated tools, and lack of longitudinal HRQOL studies may explain differences.

Proving the benefits of GA has been difficult with respect to study designs and ethical considerations. However, the yields of GA are too large to ignore and do lead to altered treatment recommendations.67 This does not mean that treatment should be downgraded for frail patients. Accordingly, frail patients also did not regret the treatment decision that was made more than nonfrail patients.68 However, loss of HRQOL might have been prevented by providing a more tailored treatment. Potential interventions can include pretreatment referral to a geriatrician, optimization of comorbidities, management of polypharmacy, nutritional support, and professional psychosocial support. Prehabilitation studies and routine clinical care pathways are under investigation, also in HNC.69

Based on these data, we strongly recommend a broad screening of all geriatric domains and involving a geriatrician with the screening. Currently, in our department, all presenting patients undergo a broad geriatric screening by a nurse that consists of compact screening tools but includes all geriatric domains. The results of this screening are subsequently discussed with a geriatrician in a multidisciplinary team and a CGA and paramedic consultation can be indicated, or other recommendations can be given. Forthcoming information from the CGA or consultation can be incorporated in the multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board where the final treatment proposal is made, to be discussed with the patient.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study were the prospective inclusion and long-term follow-up of a relatively large cohort, use of a large set of validated GA tools, and strong statistical analysis, allowing identification of longitudinal trends, adequate missing data handling, and consideration of baseline differences and confounders. A limitation may be the underrepresentation of very frail patients at the moment of inclusion and also during follow-up, because of higher loss to follow-up, leading to potential bias (ie, underestimation of the observed differences).70 Estimates that change when comparing the cohort with a complete follow-up cohort can be explained by reduction of sample size and specifically the disproportionate reduction of patients with deficits. This may therefore introduce more bias (underestimation) and underscores the importance of using linear mixed models for maximizing use of data points that would otherwise be missed. Factors that may have blurred outcomes can be the unconscious additional attention for frailty by oncologists and knowledge of GA outcomes by nurses, potentially leading to increased geriatric consultation, and measures that were taken by the Dutch national Safety Management System (Veiligheidsmanagementsysteem) on vulnerable older adults admitted to the hospital. Hospitalized vulnerable older adults were, as a standard of care in the Netherlands, referred to a physiotherapist or dietary consultant and benefited by fall prevention and delirium screening when this was indicated by screening. Furthermore, limitations were the relative heterogeneity of the cohort and absence of data on human papillomavirus status, which may influence HRQOL decline as well.71

Conclusions

In this prospective cohort study, geriatric deficits and especially the accumulation of domains with deficits were associated with HRQOL deterioration after treatment for HNC. Incorporating GA in the workup of patients with HNC can aid decision-making, indicate interventions, and hopefully reduce loss of HRQOL.

eTable 1. Mean Global Health Status/Quality of Life by stage and treatment categories

eTable 2. Mean Global Health Status/Quality of Life by individual geriatric tests

eTable 3. Complete-response analysis comparing estimates between complete responses (all outcome measurements present [n=124]) vs. total study population (n=283)

References

- 1.van Deudekom FJ, Schimberg AS, Kallenberg MH, Slingerland M, van der Velden LA, Mooijaart SP. Functional and cognitive impairment, social environment, frailty and adverse health outcomes in older patients with head and neck cancer, a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2017;64:27-36. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752-762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bras L, Driessen DAJJ, de Vries J, et al. Patients with head and neck cancer: are they frailer than patients with other solid malignancies? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2020;29(1):e13170. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray F, Soerjomataram I. The changing global burden of cancer: transitions in human development and implications for cancer prevention and control. In: Gelband H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R, Horton S, eds. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities. 3rd ed. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2015:23-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kojima G, Iliffe S, Walters K. Smoking as a predictor of frailty: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0134-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strandberg AY, Trygg T, Pitkälä KH, Strandberg TE. Alcohol consumption in midlife and old age and risk of frailty: alcohol paradox in a 30-year follow-up study. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):248-254. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkhus L, Šaltytė Benth J, Rostoft S, et al. Geriatric assessment is superior to oncologists’ clinical judgement in identifying frailty. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(4):470-477. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu TS, Sklar M, Cohen M, et al. Is frailty associated with worse outcomes after head and neck surgery? a narrative review. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(6):1436-1442. doi: 10.1002/lary.28307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noor A, Gibb C, Boase S, Hodge J-C, Krishnan S, Foreman A. Frailty in geriatric head and neck cancer: a contemporary review. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(12):E416-E424. doi: 10.1002/lary.27339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vries J, Bras L, Sidorenkov G, et al. Frailty is associated with decline in health-related quality of life of patients treated for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2020;111:105020. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.105020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas CM, Sklar MC, Su J, et al. Longitudinal assessment of frailty and quality of life in patients undergoing head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(7):E2232-E2242. doi: 10.1002/lary.29375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akishita M, Ishii S, Kojima T, et al. Priorities of health care outcomes for the elderly. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(7):479-484. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stegmann ME, Festen S, Brandenbarg D, et al. Using the Outcome Prioritization Tool (OPT) to assess the preferences of older patients in clinical decision-making: a review. Maturitas. 2019;128:49-52. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derks W, de Leeuw RJ, Hordijk GJ. Elderly patients with head and neck cancer: the influence of comorbidity on choice of therapy, complication rate, and survival. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13(2):92-96. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000156169.63204.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubenstein LZ. Joseph T. Freeman award lecture: comprehensive geriatric assessment: from miracle to reality. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(5):473-477. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.5.M473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, van Munster BC. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):e437-e444. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70259-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Li D, Yuan Y, Lau YM, Hurria A. Functional versus chronological age: geriatric assessments to guide decision making in older patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):e305-e316. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30348-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sidorenkov G, Nagel J, Meijer C, et al. The OncoLifeS data-biobank for oncology: a comprehensive repository of clinical data, biological samples, and the patient’s perspective. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):374. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2122-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 7th ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piccirillo JF. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(4):593-602. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma M, Loh KP, Nightingale G, Mohile SG, Holmes HM. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(5):346-353. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elia M. The “MUST” Report. Nutritional Screening for Adults: A Multidisciplinary Responsibility. Development and Use of the “Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool” (MUST) for Adults. British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914-919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142-148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barry E, Galvin R, Keogh C, Horgan F, Fahey T. Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Cammen TJ, van Harskamp F, Stronks DL, Passchier J, Schudel WJ. Value of the Mini-Mental State Examination and informants’ data for the detection of dementia in geriatric outpatients. Psychol Rep. 1992;71(3 Pt 1):1003-1009. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3.1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1-2):165-173. doi: 10.1300/J018v05n01_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365-376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A.. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd ed. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shek DTL, Ma CMS. Longitudinal data analyses using linear mixed models in SPSS: concepts, procedures and illustrations. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:42-76. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorldJournal. 2001;1:323-336. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2001.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722-727. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty defined by deficit accumulation and geriatric medicine defined by frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):17-26. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theou O, Walston J, Rockwood K. Operationalizing frailty using the frailty phenotype and deficit accumulation approaches. Interdiscip Top Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;41:66-73. doi: 10.1159/000381164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bras L, de Vries J, Festen S, et al. Frailty and restrictions in geriatric domains are associated with surgical complications but not with radiation-induced acute toxicity in head and neck cancer patients: a prospective study. Oral Oncol. 2021;118:105329. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139-144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Binenbaum Y, Amit M, Billan S, Cohen JT, Gil Z. Minimal clinically important differences in quality of life scores of oral cavity and oropharynx cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(8):2773-2781. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3656-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musoro JZ, Coens C, Singer S, et al. ; EORTC Head and Neck and Quality of Life Groups . Minimally important differences for interpreting European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 scores in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2020;42(11):3141-3152. doi: 10.1002/hed.26363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Deiry MW, Futran ND, McDowell JA, Weymuller EA Jr, Yueh B. Influences and predictors of long-term quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(4):380-384. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Østhus AA, Aarstad AK, Olofsson J, Aarstad HJ. Comorbidity is an independent predictor of health-related quality of life in a longitudinal cohort of head and neck cancer patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270(5):1721-1728. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2207-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Buffart LM, Heymans MW, et al. The course of health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemoradiation: a prospective cohort study. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110(3):422-428. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gourin CG, Boyce BJ, Vaught CC, Burkhead LM, Podolsky RH. Effect of comorbidity on post-treatment quality of life scores in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(5):907-914. doi: 10.1002/lary.20199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oozeer NB, Benbow J, Downs C, Kelly C, Welch A, Paleri V. The effect of comorbidity on quality of life during radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(2):268-272. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peters TTA, van der Laan BFAM, Plaat BEC, Wedman J, Langendijk JA, Halmos GB. The impact of comorbidity on treatment-related side effects in older patients with laryngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2011;47(1):56-61. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noel CW, Forner D, Wu V, et al. Predictors of surgical readmission, unplanned hospitalization and emergency department use in head and neck oncology: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2020;111:105039. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.105039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Babcock ZR, Kogut SJ, Vyas A. Association between polypharmacy and health-related quality of life among cancer survivors in the United States. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(1):89-99. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00837-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lis CG, Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Markman M, Vashi PG. Role of nutritional status in predicting quality of life outcomes in cancer—a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2012;11:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prevost V, Joubert C, Heutte N, Babin E. Assessment of nutritional status and quality of life in patients treated for head and neck cancer. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2014;131(2):113-120. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crowder SL, Douglas KG, Yanina Pepino M, Sarma KP, Arthur AE. Nutrition impact symptoms and associated outcomes in post-chemoradiotherapy head and neck cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(4):479-494. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0687-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pottel L, Lycke M, Boterberg T, et al. Serial comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly head and neck cancer patients undergoing curative radiotherapy identifies evolution of multidimensional health problems and is indicative of quality of life. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23(3):401-412. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brugel L, Laurent M, Caillet P, et al. Impact of comprehensive geriatric assessment on survival, function, and nutritional status in elderly patients with head and neck cancer: protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial (EGeSOR). BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):427. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kirkhus L, Harneshaug M, Šaltytė Benth J, et al. Modifiable factors affecting older patients’ quality of life and physical function during cancer treatment. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(6):904-912. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Njegovan V, Hing MM, Mitchell SL, Molnar FJ. The hierarchy of functional loss associated with cognitive decline in older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(10):M638-M643. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.M638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.VanderWalde NA, Deal AM, Comitz E, et al. Geriatric assessment as a predictor of tolerance, quality of life, and outcomes in older patients with head and neck cancers and lung cancers receiving radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98(4):850-857. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huisman MG, van Leeuwen BL, Ugolini G, et al. “Timed Up & Go”: a screening tool for predicting 30-day morbidity in onco-geriatric surgical patients? a multicenter cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bolt S, Eadie T, Yorkston K, Baylor C, Amtmann D. Variables associated with communicative participation after head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142(12):1145-1151. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams AM, Lindholm J, Cook D, Siddiqui F, Ghanem TA, Chang SS. Association between cognitive function and quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(12):1228-1235. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rohde RL, Adjei Boakye E, Challapalli SD, et al. Prevalence and sociodemographic factors associated with depression among hospitalized patients with head and neck cancer—results from a national study. Psychooncology. 2018;27(12):2809-2814. doi: 10.1002/pon.4893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dunne S, Mooney O, Coffey L, et al. Psychological variables associated with quality of life following primary treatment for head and neck cancer: a systematic review of the literature from 2004 to 2015. Psychooncology. 2017;26(2):149-160. doi: 10.1002/pon.4109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terrell JE, Ronis DL, Fowler KE, et al. Clinical predictors of quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(4):401-408. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.4.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karnell LH, Christensen AJ, Rosenthal EL, Magnuson JS, Funk GF. Influence of social support on health-related quality of life outcomes in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2007;29(2):143-146. doi: 10.1002/hed.20501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Birkhaug EJ, Aarstad HJ, Aarstad AK, Olofsson J. Relation between mood, social support and the quality of life in patients with laryngectomies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259(4):197-204. doi: 10.1007/s00405-001-0444-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fang F-M, Tsai W-L, Chien C-Y, et al. Changing quality of life in patients with advanced head and neck cancer after primary radiotherapy or chemoradiation. Oncology. 2005;68(4-6):405-413. doi: 10.1159/000086982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Festen S, Kok M, Hopstaken JS, et al. How to incorporate geriatric assessment in clinical decision-making for older patients with cancer. an implementation study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(6):951-959. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas CM, Sklar MC, Su J, et al. Evaluation of older age and frailty as factors associated with depression and postoperative decision regret in patients undergoing major head and neck surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(12):1170-1178. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.3020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Holstein Y, van Deudekom FJ, Trompet S, et al. Design and rationale of a routine clinical care pathway and prospective cohort study in older patients needing intensive treatment. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01975-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hempenius L, Slaets JPJ, Boelens MAM, et al. Inclusion of frail elderly patients in clinical trials: solutions to the problems. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(1):26-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Korsten LHA, Jansen F, Lissenberg-Witte BI, et al. The course of health-related quality of life from diagnosis to two years follow-up in patients with oropharyngeal cancer: does HPV status matter? Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(8):4473-4483. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05932-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Mean Global Health Status/Quality of Life by stage and treatment categories

eTable 2. Mean Global Health Status/Quality of Life by individual geriatric tests

eTable 3. Complete-response analysis comparing estimates between complete responses (all outcome measurements present [n=124]) vs. total study population (n=283)