Abstract

Glial cells are non‐neuronal cells in the nervous system that are electrically non‐excitable and outnumber neurons in humans. Glial cells have attracted attention in recent years for their active involvement in the regulation of neuronal activity, suggesting their contribution to the pathogenesis and progression of neurological diseases. Studies have shown that astrocytes, a type of glial cell, are activated in the spinal cord in response to skin inflammation and contribute to the exacerbation of chronic itch. This review summarizes the current knowledge about the role of astrocytes and other glial cells in the modulation of itch processing and the mechanism of their activation under itch conditions.

Keywords: astrocytes, atopic dermatitis, glia, itch, spinal cord

Astrocytes are activated in response to skin inflammation and then enhance itch‐specific GRPR signaling in the spinal dorsal horn, which exacerbates chronic itch.

Abbreviations

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- GRP

gastrin‐releasing peptide

- GRPR

GRP receptor

- SDH

spinal dorsal horn

1. WHAT ARE GLIAL CELLS?

The name "glia" originates from the Greek word for "glue" as these cells were initially recognized as a glue‐like substance filling the spaces between neurons. However, studies have revealed the existence of many types of glial cells, such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia, with diverse functions, including neuroprotection, maintenance of homeostasis in the nervous system, and modulation of neuronal activity. Thus, an understanding of not only neuronal communication but also glial‐neuronal communication is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms of neuronal function and the pathology of neurological diseases. 1

2. ITCH TRANSMISSION PATHWAYS AND CHRONIC ITCH

Itch is defined as an unpleasant cutaneous sensation that causes a desire to scratch the skin and mucous membranes. This sensation protects the body by removing harmful substances from the external environment, such as pathogens, parasites, and toxins from insects and plants, by causing scratching when they contact or invade the skin. Itch is also caused by inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and systemic diseases such as cholestasis. Thus, it also plays a role in alerting us to functional abnormalities in the skin or other tissues.

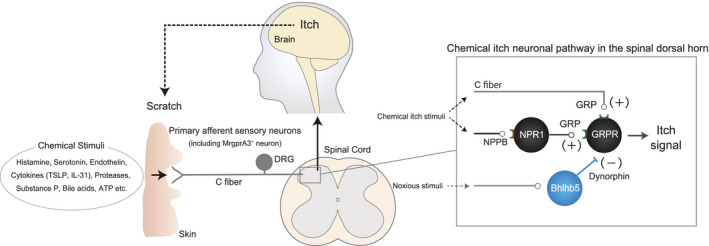

Itch signals are generated at the free nerve endings of primary afferent sensory fibers (C fibers) in the skin when stimulated by pruritogens such as histamine (Figure 1). The itch signal is then transmitted through the cell bodies of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons to the spinal dorsal horn (SDH) neurons and, finally, to the brain neurons. 2 , 3 Until recently, itch was assumed to be a type of weak pain sensation. However, gastrin‐releasing peptide (GRP)‐GRP receptor (GRPR) signaling in the SDH was recently shown to contribute specifically to the transmission of itch signals generated by different pruritogens. 4 A subsequent study showed that GRPR‐positive SDH neurons are essential for the processing of information on both pruritogen‐induced and chronic itch caused by allergic dermatitis (chemical itch). 5 Based on these findings, various neurons and proteins, such as natriuretic peptide receptor 1 (NPR1)‐positive SDH neurons containing GRP, natriuretic polypeptide B (NPPB), a ligand for NPR1 released from primary afferents, 6 and Mas‐related G‐protein coupled receptor member A3 (MrgprA3)‐positive primary afferent sensory neurons, 7 have been identified as specifically involved in chemical itch. These findings strongly suggest the presence of an itch‐specific neuronal pathway distinct from that of pain. While the neuronal pathways that contribute to evoking chemical itch have been identified, itch inhibitory neurons and proteins in the SDH, such as basic helix‐loop‐helix domain containing class B 5 (Bhlhb5)‐positive inhibitory neurons, dynorphin, and kappa‐opioid receptors, have also been identified, 8 , 9 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Chemical itch transduction pathway

Recently, mechanical itch transduction pathways have also been identified. The ablation of SDH inhibitory interneurons defined by the expression of neuropeptide Y (Npy)‐Cre increased itch behavior evoked by innocuous mechanical stimulation (alloknesis) in a GRPR‐positive neuron‐independent manner. 10 This alloknesis occurs via a pathway involving populations of excitatory SDH interneurons expressing urocortin 3 or the Npy1 receptor. 11 , 12

Itch is normally transient, disappearing gradually with temporary scratching to the affected area; however, most itches associated with skin and systemic diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, are chronic. Although chronic itch affects millions of people worldwide and requires proper treatment, 13 existing therapies such as antihistamines (histamine H1 receptor antagonists) are less effective. 14 This may be due to the presence or increase of histamine receptors other than the H1 receptor (e.g., H4 receptor), 15 various endogenous pruritogens other than histamine, 2 , 3 such as serotonin, 16 , 17 endothelin, 18 , 19 cytokines including thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and interleukin (IL)‐31, 20 , 21 proteases, 22 substance P, 23 bile acids, 24 , 25 adenosine triphosphate (ATP), 26 or their receptors. Under chronic itch conditions, there are severe and abnormal itches that are rarely observed under normal conditions, such as “sensitization for itch,” in which the sensitivity to itch increases, and the “itch‐scratch vicious cycle,” in which skin inflammation caused by prolonged repetitive scratching leads to repeated severe itch. These phenomena lead to further exacerbation and intractability of itch and dermatitis. 2 , 27

3. ACTIVATION OF SDH ASTROCYTES AND SPINAL SENSITIZATION FOR ITCH DURING CHRONIC ITCH

Astrocytes, the most numerous glial cells, play an important role in regulating neuronal activity in the central nervous system (CNS). 28 , 29 One of the major characteristics of astrocytes is that they are activated with gene expression changes and inflammatory responses when they sense neuronal damage or dysfunction during neurological diseases. 29 , 30 , 31

Recently, increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), an indicator of astrocytic activation, was observed in the SDH of different mouse models of skin inflammation with chronic itch, including spontaneous atopic dermatitis (AD) model mice (NC/Nga mice), diphenylcyclopropenone (DCP)‐induced contact dermatitis (CD) model mice, 32 2, 4‑dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB)‐induced allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) model mice 33 and acetone and ether followed by water (AEW)‐induced dry skin model mice. 34 Most of these activations were inhibited by the intrathecal administration of a compound that inhibited the activation of a transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) or by a conditional disruption of astrocytic STAT3. 32 , 33 These findings suggest the STAT3‐dependent activation of SDH astrocytes under chronic itch conditions. Behavioral experiments have also shown that astrocytic STAT3 does not contribute to acute itch caused by intradermal administration of pruritogens but does contribute to chronic itch caused by skin inflammation. 32

Sensitization for itch is a phenomenon that occurs frequently in chronic itch, as described above. In the last two decades, peripheral sensitization for itch caused by the elongation and penetration of C fibers in the epidermis has been widely understood as the main mechanism of sensitization for itch. 2 , 35 More recently, the Th2 cytokine IL‐4 was shown to enhance the responsiveness of primary afferent sensory neurons to multiple pruritogens, 36 indicating that several mechanisms can cause peripheral sensitization for itch. In contrast, in 2003, Ikoma et al. investigated the degree of both itch and axon reflex flare induced by histamine prick in the skin of patients with AD. Severe itching was evoked in the lesional skin of these patients, although the flare was relatively small, indicating possible spinal sensitization for itch. 37 A recent study showed that the intrathecal administration of GRP, an itch‐inducing neuropeptide in the SDH, to AD model mice greatly increased the number of scratching (itch‐related behavior) events compared to control mice, suggesting the existence of spinal sensitization for itch in chronic itch model mice. This enhanced itch in AD model mice was inhibited by prior intrathecal administration of a compound that inhibited STAT3 activation to the same extent as in control mice. 32 Furthermore, lipocalin 2 (LCN2), a humoral factor upregulated in an astrocytic STAT3‐dependent manner during chronic itch, enhanced both itch and GRPR‐positive neuronal excitability induced by GRP when co‐treated with GRP, whereas LCN2 alone did not increase both scratching and GRPR‐positive neuronal excitability. 32 , 38 AD and CD model mice with astrocytic STAT3 activation in the SDH showed significant upregulation of LCN2 in the SDH. 32 In addition to these models, DNFB‐induced ACD model mice also showed astrocytic STAT3 activation in the SDH; however, the change in expression of LCN2 remains to be investigated. 33 The selective suppression of LCN2 expression in SDH astrocytes inhibited chronic itch in both AD and CD model mice. 32 , 38 Results from AD and CD mouse models suggest that under chronic itch conditions, STAT3‐dependent upregulation of LCN2 in SDH astrocytes contributes to the exacerbation of chronic itch by developing spinal sensitization for itch. However, it would be better to confirm the change in expression of LCN2 in other models such as DNFB‐induced ACD model where astrocytic STAT3 activation is observed in the future. Then we will be able to understand more clearly the importance of astrocytic STAT3‐LCN2 pathway during chronic itch.

In contrast to most dermatitis mouse models with chronic itch, no astrocytic activation was observed in the SDH of imiquimod‐induced psoriasis model mice. 39 Moreover the number of scratching events in the psoriasis model mice was lower than that in AD model mice (M. Shiratori‐Hayashi et al., unpublished data) and the degree of itch induced by histamine prick in psoriasis patients was also lower than that in AD patients. 37 These results indicate that spinal sensitization to itch may not occur in psoriasis.

4. MECHANISMS OF SPINAL ASTROCYTE ACTIVATION IN CHRONIC ITCH

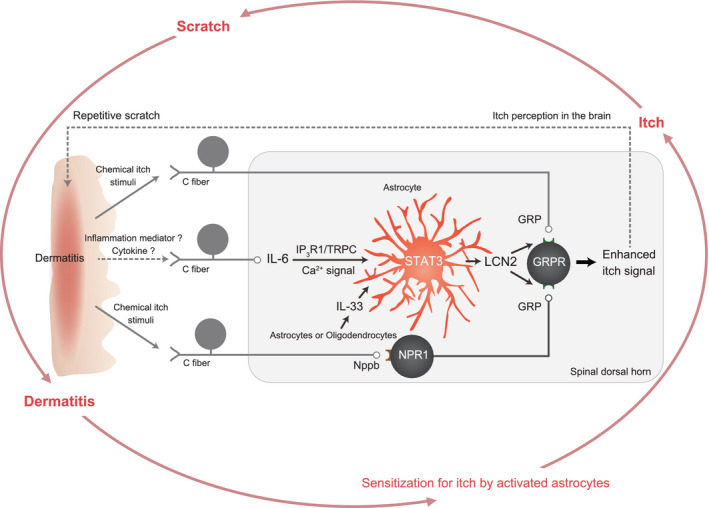

In AD model mice, astrocytic activation and dermatitis were temporally correlated and astrocytic activation was observed only in the cervical SDH, which corresponded to the skin area at which dermatitis occurred. Preventing scratching‐induced dermatitis by trimming toenails inhibited both itch and astrocytic activation in the SDH of AD and CD mouse models. 32 Astrocytic activation in the SDH of AEW‐induced dry skin model mice was also inhibited by the use of Elizabethan Collars, which can prevent mice from scratching the itchy skin. 34 These findings suggest that astrocytic activation is induced by dermatitis caused by prolonged repetitive scratching; that is, spinal sensitization for itch due to astrocytic activation may be induced by scratch‐dependent dermatitis, leading to the development of the itch‐scratch vicious cycle (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Astrocytic activation and itch modulation in the spinal dorsal horn during chronic itch

The skin and spinal cord are not in direct contact but rather are connected via primary afferent sensory neurons. Ablation of TRPV1‐positive sensory neurons inhibited astrocytic activation in the SDH of both AD and CD model mice, suggesting that dermatitis induces astrocytic activation in the SDH via primary afferent sensory neurons. 32 Gene expression changes have been detected in sensory neurons; in particular, the pro‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐6, a well‐known activator of STAT3, was upregulated in the DRG, where cell bodies of sensory neurons are clustered, in AD (M. Shiratori‐Hayashi et al., unpublished data) and CD model mice. 40 Sensory neuron‐selective knockdown of IL‐6 inhibited chronic itch and LCN2 expression. 40 These results demonstrate that IL‐6 upregulation in primary afferent sensory neurons contributes to chronic itch via the induction of astrocytic STAT3 activation.

IL‐6 can induce not only the well‐known transient activation of STAT3 lasting 1–2 h 41 but also a persistent activation of STAT3 lasting over 24 h in astrocytes. 40 IL‐6‐induced upregulation of Lcn2 in astrocytes was temporally correlated with the persistent activation of STAT3 (M. Shiratori‐Hayashi et al., unpublished data). This persistent activation was mediated by type 1 inositol 1,4,5‐triphosphate receptors (IP3R1)/transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels‐dependent small and long‐lasting Ca2+ signals but not by IP3R2 which has always been considered to play a central role in astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics. 40 These findings suggest that IL‐6 upregulation in primary afferent sensory neurons induces IP3R1/TRPC‐dependent long‐lasting Ca2+ signals in astrocytes, which leads to exacerbation of chronic itch via both the persistent activation of astrocytic STAT3 and subsequent upregulation of LCN2 (Figure 2).

In addition to IL‐6 upregulation in primary afferent sensory neurons, a study using DNFB‐induced ACD mouse models indicated that IL‐33, which is upregulated in SDH astrocytes or oligodendrocytes, contributed to astrocytic STAT3 activation during chronic itch. 33 At present, the relationship between IL‐6 from primary afferents and IL‐33 upregulation in SDH glial cells is unclear; however, clarification of this point may allow a better understanding of the mechanism of STAT3 activation in SDH astrocytes during chronic itch. It was also found that prior intrathecal administration of IL‐33 significantly increased the number of GRP‐induced scratching, whereas IL‐33 that was co‐administrated with GRP could not increase it. 33 These results indicate that IL‐33 acts indirectly, rather than directly, on GRPR‐positive neurons and contributes to the enhancement of their excitability. Since the IL‐33 receptor ST2 deficiency inhibited STAT3 activation in the SDH of DNFB‐induced ACD model mice, 33 IL‐33 may contribute to the enhancement of GRPR‐positive neuronal excitability via STAT3‐dependent upregulation of soluble factors that can directly enhance its excitability (e.g. LCN2). This point will need to be examined in detail in the future.

In AEW‐induced dry skin model mice, Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4) mediated astrocytic activation. AEW treatment induced TLR4 upregulation in SDH astrocytes and both GFAP increase and itch were inhibited by the systemic knockout of Tlr4. 34 AEW‐induced itch was also inhibited by systemic knockout of myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (Myd88), an adaptor protein of TLR signaling, indicating that MyD88 mediates TLR4‐dependent astrocytic activation in AEW model mice. 34 As MyD88 has also been suggested to contribute to STAT3 activation in a human lymphoma cell line, 42 whether a similar mechanism exists in astrocytes requires exploration.

5. SPINAL CORD MICROGLIA AND ITCH

Microglia are immunocompetent cells in the CNS with many functional similarities to macrophages. 1 Upregulation of ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1), an indicator of microglial activation, was not observed in the SDH during the chronic phase of AD or dry skin model mice with astrocytic activation. However, microglia were transiently activated at approximately 0.5 to 1 h after the administration of some pruritogens 43 or on day 3 in the ACD model. 44 The p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase may mediate these activations. 44 The intrathecal administration of minocycline, an inhibitor of microglial activation, 45 reduced itch behavior only on day 3 in the ACD model. 44 In dry skin model mice, short‐term upregulation of Iba1 occurred from days 1 to 3 but not on day 5. 34 Furthermore, microglial activation was also observed in the SDH of mice with psoriasis. The intrathecal administration of minocycline and oral administration of a brain‐penetrant inhibitor of colony‐stimulating factor‐1 receptor, which robustly eliminates microglia, 46 inhibited itch in the psoriasis model. 39 These findings indicate the contribution of SDH microglia to itch, especially during the early phase of chronic itch. Additional studies are needed to identify itch‐related factors from microglia and to examine the effects of microglia‐selective repression of the target gene expression on itch in the early phase of various itch models such as pruritogen‐induced itch and itch in the psoriasis and ACD models.

6. SUMMARY AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

These findings suggest that changes in the CNS, particularly glial cells in the SDH, contribute to various itches, including chronic itch, in addition to the changes in the skin that have been the main focus of itch studies, thus suggesting new mechanisms to modulate itch. Recent studies have shown that SDH astrocytes are commonly activated in most mouse models of chronic itch, that their activation is induced by changes in peripheral tissues such as skin inflammation and gene expression changes in primary afferent sensory neurons, and that astrocytic humoral factors that are produced in an activation‐dependent manner act on itch‐specific SDH neurons to cause spinal sensitization for itch, contributing to the development and maintenance of chronic itch (Figure 2). In contrast, in the case of microglia, activation is rarely observed in the chronic phase of itch; however, transient short‐term activation is likely to occur mainly in the early phase of chronic itch or after the administration of pruritogens, indicating that microglia may contribute to the early phase of itch or acute itch rather than the chronic phase of itch. Although further studies are needed, microglia likely contribute to itch differently from astrocytes.

Glial cells exist not only in the CNS, such as the spinal cord and brain, but also around the cell bodies or axons of primary afferent sensory neurons. Therefore, the detailed elucidation of the role of glial cells in itch in all neural tissues, including the spinal cord, may more clearly reveal new aspects of both glial function and itch modulation mechanisms.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Since no new data were generated or analyzed in this study, it is not subject to screening and approval by the ethics committee of the research institution.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

NOMENCLATURE OF TARGETS AND LIGANDS

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY, 47 and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20. 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP19K22500, JP19H05658, and JP20H05900 (M.T.).

Shiratori‐Hayashi M, Tsuda M. Spinal glial cells in itch modulation. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2021;9:e00754. 10.1002/prp2.754

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allen NJ, Lyons DA. Glia as architects of central nervous system formation and function. Science. 2018;362(6411):181‐185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ikoma A, Steinhoff M, Stander S, Yosipovitch G, Schmelz M. The neurobiology of itch. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(7):535‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Han L, Dong X. Itch mechanisms and circuits. Annu Rev Biophys. 2014;43:331‐355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sun YG, Chen ZF. A gastrin‐releasing peptide receptor mediates the itch sensation in the spinal cord. Nature. 2007;448(7154):700‐703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun YG, Zhao ZQ, Meng XL, Yin J, Liu XY, Chen ZF. Cellular basis of itch sensation. Science. 2009;325(5947):1531‐1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mishra SK, Hoon MA. The cells and circuitry for itch responses in mice. Science. 2013;340(6135):968‐971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Han L, Ma C, Liu Q, et al. A subpopulation of nociceptors specifically linked to itch. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(2):174‐182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ross SE, Mardinly AR, McCord AE, et al. Loss of inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal spinal cord and elevated itch in Bhlhb5 mutant mice. Neuron. 2010;65(6):886‐898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kardon A, Polgár E, Hachisuka J, et al. Dynorphin acts as a neuromodulator to inhibit itch in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Neuron. 2014;82(3):573‐586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bourane S, Duan B, Koch SC, et al. Gate control of mechanical itch by a subpopulation of spinal cord interneurons. Science. 2015;350(6260):550‐554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pan H, Fatima M, Li A, et al. Identification of a spinal circuit for mechanical and persistent spontaneous itch. Neuron. 2019;103(6):1135‐1149 e1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Acton D, Ren X, Di Costanzo S, et al. Spinal neuropeptide Y1 receptor‐expressing neurons form an essential excitatory pathway for mechanical itch. Cell Rep. 2019;28(3):625‐639 e626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biomedicine MG. Grasping for clues to the biology of itch. Science. 2007;318(5848):188‐189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klein PA, Clark RA. An evidence‐based review of the efficacy of antihistamines in relieving pruritus in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135(12):1522‐1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dunford PJ, Williams KN, Desai PJ, Karlsson L, McQueen D, Thurmond RL. Histamine H4 receptor antagonists are superior to traditional antihistamines in the attenuation of experimental pruritus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(1):176‐183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmelz M, Schmidt R, Weidner C, Hilliges M, Torebjork HE, Handwerker HO. Chemical response pattern of different classes of C‐nociceptors to pruritogens and algogens. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89(5):2441‐2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akiyama T, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Facial injections of pruritogens and algogens excite partly overlapping populations of primary and second‐order trigeminal neurons in mice. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104(5):2442‐2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katugampola R, Church MK, Clough GF. The neurogenic vasodilator response to endothelin‐1: a study in human skin in vivo. Exp Physiol. 2000;85(6):839‐846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McQueen DS, Noble MA, Bond SM. Endothelin‐1 activates ETA receptors to cause reflex scratching in BALB/c mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151(2):278‐284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilson S, Thé L, Batia L, et al. The epithelial cell‐derived atopic dermatitis cytokine TSLP activates neurons to induce itch. Cell. 2013;155(2):285‐295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cevikbas F, Wang X, Akiyama T, et al. A sensory neuron‐expressed IL‐31 receptor mediates T helper cell‐dependent itch: involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):448‐460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Soh UJ, Dores MR, Chen B, Trejo J. Signal transduction by protease‐activated receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160(2):191‐203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hosogi M, Schmelz M, Miyachi Y, Ikoma A. Bradykinin is a potent pruritogen in atopic dermatitis: a switch from pain to itch. Pain. 2006;126(1–3):16‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Varadi DP. Pruritus induced by crude bile and purified bile acids. Experimental production of pruritus in human skin. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109(5):678‐681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alemi F, Kwon E, Poole DP, et al. The TGR5 receptor mediates bile acid‐induced itch and analgesia. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1513‐1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shiratori‐Hayashi M, Hasegawa A, Toyonaga H, et al. Role of P2X3 receptors in scratching behavior in mouse models. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(3):1252‐1254 e1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ikoma A. Updated neurophysiology of itch. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36(8):1235‐1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(3):1009‐1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Halassa MM, Haydon PG. Integrated brain circuits: astrocytic networks modulate neuronal activity and behavior. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:335‐355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ceyzeriat K, Abjean L, Carrillo‐de Sauvage MA, Ben Haim L, Escartin C. The complex STATes of astrocyte reactivity: how are they controlled by the JAK‐STAT3 pathway? Neuroscience. 2016;330:205‐218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sofroniew MV. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(12):638‐647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shiratori‐Hayashi M, Koga K, Tozaki‐Saitoh H, et al. STAT3‐dependent reactive astrogliosis in the spinal dorsal horn underlies chronic itch. Nat Med. 2015;21(8):927‐931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Du L, Hu X, Yang W, et al. Spinal IL‐33/ST2 signaling mediates chronic itch in mice through the astrocytic JAK2‐STAT3 cascade. Glia. 2019;67(9):1680‐1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu T, Han Q, Chen G, et al. Toll‐like receptor 4 contributes to chronic itch, alloknesis, and spinal astrocyte activation in male mice. Pain. 2016;157(4):806‐817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tominaga M, Takamori K. Itch and nerve fibers with special reference to atopic dermatitis: therapeutic implications. J Dermatol. 2014;41(3):205‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co‐opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171(1):217‐228 e213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ikoma A, Rukwied R, Stander S, Steinhoff M, Miyachi Y, Schmelz M. Neuronal sensitization for histamine‐induced itch in lesional skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(11):1455‐1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koga K, Yamagata R, Kohno K, et al. Sensitization of spinal itch transmission neurons in a mouse model of chronic itch requires an astrocytic factor. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):183‐191 e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu Z, Qin Z, Zhang J, Wang Y. Microglia‐mediated chronic psoriatic itch induced by imiquimod. Mol Pain. 2020;16:1744806920934998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shiratori‐Hayashi M, Yamaguchi C, Eguchi K, et al. Astrocytic STAT3 activation and chronic itch require IP3R1/TRPC‐dependent Ca2+ signals in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;S0091‐6749(20)31105‐2. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ivashkiv LB, Hu X. Signaling by STATs. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(4):159‐168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R, et al. Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature. 2011;470(7332):115‐119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang Y, Dun SL, Chen YH, Luo JJ, Cowan A, Dun NJ. Scratching activates microglia in the mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci Res. 2015;93(3):466‐474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang Y, Yan J, Hu R, et al. Microglia are involved in pruritus induced by DNFB via the CX3CR1/p38 MAPK pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35(3):1023‐1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tikka T, Fiebich BL, Goldsteins G, Keinanen R, Koistinaho J. Minocycline, a tetracycline derivative, is neuroprotective against excitotoxicity by inhibiting activation and proliferation of microglia. J Neurosci. 2001;21(8):2580‐2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spangenberg EE, Lee RJ, Najafi AR, et al. Eliminating microglia in Alzheimer's mice prevents neuronal loss without modulating amyloid‐beta pathology. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 4):1265‐1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1091‐D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alexander SPH, Christopoulos A, Davenport AP, et al. THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(Suppl 1):S21‐S141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA, et al. THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(Suppl 1):S142‐S228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, et al. THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: catalytic receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(Suppl 1):S247‐S296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, et al. THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(Suppl 1):S297‐S396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alexander SPH, Kelly E, Mathie A, et al. THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: transporters. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(Suppl 1):S397‐S493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.