Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Cancer outcome disparities exist among Black, Indigenous, and people of color despite advancements in screening, detection, and treatment. In addition to racial and ethnic diversity, the U.S. population is experiencing shifts in sociodemographics, including a growing aging population, sex and gender identities, spiritual and religious belief systems, and divides between high- and low-income households.

OBJECTIVES:

This article provides a foundation for cultural humility as a clinical competency in nursing to improve the quality of cancer care.

METHODS:

CINAHL®, PubMed®, Google Scholar, and grey literature were searched using keywords, including cultural humility, cultural competence, nursing, nursing pipeline, nursing workforce, and health.

FINDINGS:

Retraining and retooling the nursing workforce promotes multiculturalism in oncology care and increases opportunities to provide more appropriate, patient-centered care to those living with cancer. Increasing the diversity of nursing faculty and staff, enhancing nursing curricula and education, and creating equitable relationships to support patient-centered care are initiatives to ensure high-quality care.

Keywords: cultural humility, diversity, health equity, nursing education, nursing workforce

DESPITE ADVANCEMENTS IN SCREENING, DETECTION, AND TREATMENT, cancer outcome disparities exist among Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), as well as among other minoritized populations, such as individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ+), those living in rural areas, and those living in poverty. These populations are disproportionately participating in healthy lifestyle behaviors, diagnosed at later stages of disease, and undertreated for cancer pain, among others, as compared to non-Hispanic White people (Diamant et al., 2000; Haynes & Smedley, 1999; Shay et al., 2012; Stein et al., 2016). Disparities are largely influenced by inequitable, intersectional, and multilevel social determinants of health (e.g., structural racism and discrimination, implicit and explicit biases, unequal access to care, unequal access to physical and built environment amenities) (Alcaraz et al., 2020). As such, the presence of these inequities equates to a patient safety issue, which can result in unnecessary patient deaths. For example, Black people living with colorectal cancer in racially segregated counties are more likely to die than their White counterparts (Poulson et al., 2021). High-quality cancer care is warranted for all patients with cancer, regardless of the intersecting identities or cultures with which they exist (Crenshaw, 1991; Hewitt et al., 2005; Levit et al., 2013). In health care, there are many opportunities to negate negative social determinants of health. One of the most tangible opportunities to promote health equity lies in approaching the care of all patients in a culturally humble manner, which involves acknowledgment and reduction of biases.

As evidenced by national and international reviews, most healthcare providers, including nurses, exhibit implicit and/or explicit biases (FitzGerald & Hurst, 2017; Hall et al., 2015; Zestcott et al., 2016). Healthcare providers can see skin color; hear inflections, tones, and languages spoken; and sense other differences from patient to patient. In fact, in one study of 245 nurses at Johns Hopkins Hospital—80% of whom identified as White—Haider et al. (2015) reported that more than 80% of nurses exhibited racial biases, and 90% exhibited classist biases as measured by Harvard’s Implicit Association Test. Biases toward such differences, whether implicit or explicit, can affect patient care and perceptions in a number of ways (e.g., patient–provider interactions, treatment decisions and adherence, health outcomes) (Hall et al., 2015; Maina et al., 2018). For example, Black breast cancer survivors believed that their racial identity was associated with discriminatory actions in the healthcare setting (Campesino et al., 2012). Some individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ delay cancer screening because of fear of discrimination, but also because of other factors, such as the wrongful assumption that screening is only for cisgender individuals and a discomfort with addressing biologic sex (Quinn et al., 2015). Similarly, a meta-analysis by Carriere et al. (2018) revealed that patients with cancer in rural areas may less frequently receive guideline-concordant treatment compared to urban-dwelling patients with cancer. Therefore, healthcare providers have a significant role to play in creating health equity.

Nurses and other healthcare professionals who are responsible for the care of patients can retrain and retool themselves to provide culturally humble and anti-biased care to achieve health equity. Cultural humility is defined as “a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and critique, to redressing power imbalances … and to developing mutually beneficial and non-paternalistic partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations” (Tervalon & Murray-García, 1998, p. 123). Cultural humility surpasses the knowledge-based notion of cultural competence, which is often taught in health professional curricula and in annual competency-based trainings, and places emphasis on action to establish rapport that is conducive to excellent patient care and outcomes. It also heightens and redirects the notion of cultural sensitivity, sharing power and demanding reverence for the patient perspective in relation to decision-making around patient care. Inclusion of cultural humility in the care of minoritized patient populations may be a factor in eliminating healthcare disparities because culturally informed patient navigation has been associated with improved health outcomes among diverse patients (Jojola et al., 2017). This article provides a foundation for prioritizing cultural humility as a clinical competency of nursing, with the goal of galvanizing the nursing pipeline and workforce and fostering high-quality cancer care.

Methods

The authors evaluated peer-reviewed published articles that were identified through targeted searches in the CINAHL®, PubMed®, and Google Scholar databases. Keywords included cultural humility, cultural competence, nursing, nursing pipeline, nursing workforce, and health. In addition, grey literature (i.e., unpublished papers, government reports, and policy statements) were explored for supporting information. Included articles referenced cultural humility or cultural competence within the context of nursing education and workforce. Because of interest in identifying relevant literature, no date restrictions were applied to the search.

Findings

The findings presented in this article follow the central themes of opportunities in the nursing pipeline and workforce to implement principles of cultural humility.

Opportunities in the Nursing Pipeline

Globalization is rapidly changing the general makeup of the U.S. population. It is projected that by the year 2045, those identifying as BIPOC will no longer be the minority in the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). In addition to racial and ethnic diversity, the U.S. population is also experiencing shifts in sociodemographic components, with a growing aging population, sex and gender identities, spiritual and religious belief systems, and divides between rich and poor households (Cohn & Caumont, 2016). However, today’s growing diversity has not been reciprocated in nursing education, nor are factors outside of race, ethnicity, age, sex assigned at birth, and gender identity routinely assessed at present as they relate to the demographics of these populations. Nursing has traditionally been and continues to be dominated by White females (see Table 1), even coloring nursing history with icons, such as Florence Nightingale and Clara Barton, often excluding leading and influential Black nurses, including Mary Secole and Mary Eliza Mahoney. In 2016, nursing faculty who identified as non-White accounted for less than 16% of faculty, whereas nursing students who identified as non-White accounted for less than 30% of students; men accounted for only about 7% of nursing faculty and less than 5% of nursing students (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2017). Although the data available about diversity in nursing are limited (e.g., detailing sex [although this variable may indicate gender identity at present], a limited number of racial and ethnic backgrounds), diversity in nursing faculty and students is severely lacking in schools of nursing.

TABLE 1.

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE GENERAL AND NURSING POPULATION IN THE UNITED STATES

| GENERAL POPULATION | NURSING POPULATION | |

|---|---|---|

| RACE OR ETHNICITY | % | % |

| White | 72 | 81 |

| Hispanic | 18 | 10 |

| African American/Black | 13 | 8 |

| Asian | 6 | 5 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 | – |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | – | 1 |

| 2 or more | 3 | 2 |

| Other | 5 | 1 |

Note. Because of rounding, percentages may not total 100.

Note. Based on information from National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, 2019; U.S. Census Bureau, 2019.

Diversification in nursing is an avenue toward improving health care and health outcomes (Andrews et al., 2010). The U.S. federal government and organizations, such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, have supported diversification of the nursing profession through the provision of funding and training to some minoritized future nurses for nearly 20 years (Adams et al., 2017; Johnson-Mallard et al., 2019; Nursing Workforce Reauthorization Act, 2019); however, the state of the sociodemographic makeup of the nursing pipeline at present does not lend itself to capitalizing on the power of shared culture. As such, nursing education can retrain and retool nursing faculty and students to be humble in the face of individuals with cultures that may not be like their own. In fact, the nursing pledge commonly taken during nursing pinning ceremonies (introduction into the profession of nursing) infers that nurses have an ethical obligation to care for all individuals equitably. The American Nurses Association (2015) asserts that nurses uphold the ethics encompassed by nine major principles: compassion and respect, commitment to patients, advocacy for patient rights and well-being, promotion of optimal health, integrity, promotion of ethics, advancement of the nursing profession, collaboration across professions and sectors, and integration of social justice. Despite these principles, the healthcare workforce is wrought with inequality.

There are opportunities to reckon with inequity in nursing education. Nursing bodies now mandate the inclusion of diversity, equity, and inclusion principles in nursing curricula as a means of teaching nursing students to deliver high-quality patient care (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2021; Wakefield et al., 2021). Therefore, nursing faculty teach that patients may be different than themselves but are welcomed, seen, and heard while receiving individualized patient care to meet their needs, which may extend past health care and into social determinants of health, such as food security and transportation. The nursing profession, like other healthcare professions, is aiming to practice multiculturalism through the application of theories, such as the Model of Transcultural Nursing and the Model of Cultural Competence in Health Care Delivery, both of which advocate for holistic assessment of self and the patient toward the provision of culturally informed care to all patients (Campinha-Bacote, 2002; Giger & Davidhizar, 2002). In addition, the application of such theories in curricula allows nursing education to be a catalyst for actualizing nurses as social justice champions. In essence, “nursing education needs to ensure an understanding of the intersection of bias, structural racism, and social determinants with healthcare inequities and promote a call to action,” which will set the stage for nursing students to become practicing nurses who move the needle of health toward equity (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2021, p. 4).

Nursing schools can dismantle the traditional face and power structure of nursing by broadening efforts to bolster a diverse nursing pipeline with which to expressly recruit and retain diverse faculty and staff, as well as to bring diverse faculty and staff to executive leadership and curricula development committees. This is extremely important because faculty design course experiences broadly according to nursing core competencies (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2021); however, each course is tailored by faculty teaching within institutions. Without diversity of race, ethnicity, age, sex and gender identity, and thought, there is the potential to perpetuate the proverbial status quo—continuing in the same operations that feed health disparities rather than promoting health equity. Interventions to diversify the pipeline in nursing include mitigating academic factors (e.g., incorporating holistic admissions processes), professional integration factors (e.g., providing mentorship that broadens one’s network and supports upward movement through adversity), and environmental factors (e.g., eliminating financial barriers for higher education) (Loftin et al., 2013). Once eligible for a faculty position, diverse faculty and staff require similar support to attain and be retained in positions that best support nurses who provide care to a global society (Wakefield et al., 2021).

Opportunities in the Nursing Workforce

Outside of the classroom, nurses are on the front line of healthcare defenses against allowing “-isms” (e.g., racism, sexism, ableism) to dictate the care that patients receive. As a result, the nurse’s role in health care is ideal to facilitate changes in care delivery. Nurses can learn to provide exemplary cancer care to all patients. As referenced in nursing literature, professional nursing practice can bridge gaps in the healthcare system that might be further intensified by biases. Narayan (2019) proposed that nurses build therapeutic relationships, practice patient-centered care, become culturally competent, initiate individuation in care, take perspective to promote empathy, and build partnerships with patients to optimize their care.

Practicing patient-centered care is perhaps the most important action identified by Narayan (2019). By nature, patient-centered care is anti-biased and anti-discriminatory, with a focus on the needs of the patient. Diversification of the workforce is needed. Although effects of racial concordance on patient health outcomes are mixed, interpersonal patient–clinician interactions affect the perceived quality of care and trust (Gonzales et al., 2019; Jetty et al., 2021; Takeshita et al., 2020). As initiatives are built to support the nursing pipeline, actions can be taken at the bedside, at the chairside, and in the community to practice cultural humility.

The practice of cultural humility requires nurses to practice self-awareness, identifying and bracketing out perceptions that might bias care provided. This process is the cornerstone of patient-centered care. An example of this process in oncology care can be seen in a case study on the management of spirituality, an aspect of one’s culture (Nolan et al., 2020). As a brief review of applying cultural humility in practice, a patient presents with their own lived experience, thoughts, beliefs, and preferences for care. It is the nurse’s priority to be an anti-biased, active listener for the patient. The nurse acknowledges concerns expressed, while also acknowledging that their own insights gained from lived experiences, nursing education, and nursing practice provide a foundation for their thoughts and beliefs about the patient and the patient’s care. By using active listening, the nurse empowers the patient to assist in the identification of self-management strategies. Lastly, the nurse mobilizes supportive services to bolster the codesigned strategies. In Nolan et al. (2020), the nurse and the patient share power that directs care and eventually influences patient outcomes. Other tools for operationalizing cultural humility might include the following steps:

Start with self-reflection: Every nurse has biases, and the astute nurse takes time to acknowledge and bracket away biases that will negatively affect patient care. It is the nurse’s ethical duty to promote health through anti-biased care (American Nurses Association, 2015).

Remember that care begins with introducing yourself and indicating your pronouns: Communication is a critical component in patient care (Giger & Davidhizar, 2002). Introductions set the tone for a caring relationship. The ideal introduction establishes a respectful, culturally informed, and therapeutic care relationship.

Never underestimate the power of the social history: As described in Giger and Davidhizar’s (2002) transcultural assessment, a patient’s orientation to space, biologic variations, perceptions of time, control over environment, and social contexts are factors to consider in the context of care. So much of what brings patients to care settings is influenced by social determinants of health. Learning about a patient’s culture, work history, living space, access to food, transportation, and support system, among others, can contribute to the plan of care that nurses tailor for each patient.

Be careful not to stereotype or discriminate: One must embrace lifelong learning to practice culturally humble care (Fahlberg et al., 2016). Allow patients to inform of their thoughts, beliefs, practices, and capacity to manage their care rather than relying on preconceived beliefs. Thoughtful questions regarding the patient’s social history can inform the nurse’s approach. However, there may be missteps. In the event of offending a patient, always apologize and ask how best to avoid the misstep in the future.

Support diversity, equity, and inclusion within the nursing workforce: Be aware and acknowledge that those without similar lived experiences cannot fully understand the context of a patient’s life (Wakefield et al., 2021). Diversity is great to bolster culturally humble care. Similarly, diverse nursing staff in an environment can uplift the expectation of diversifying the way in which care is managed and nursing problems are solved.

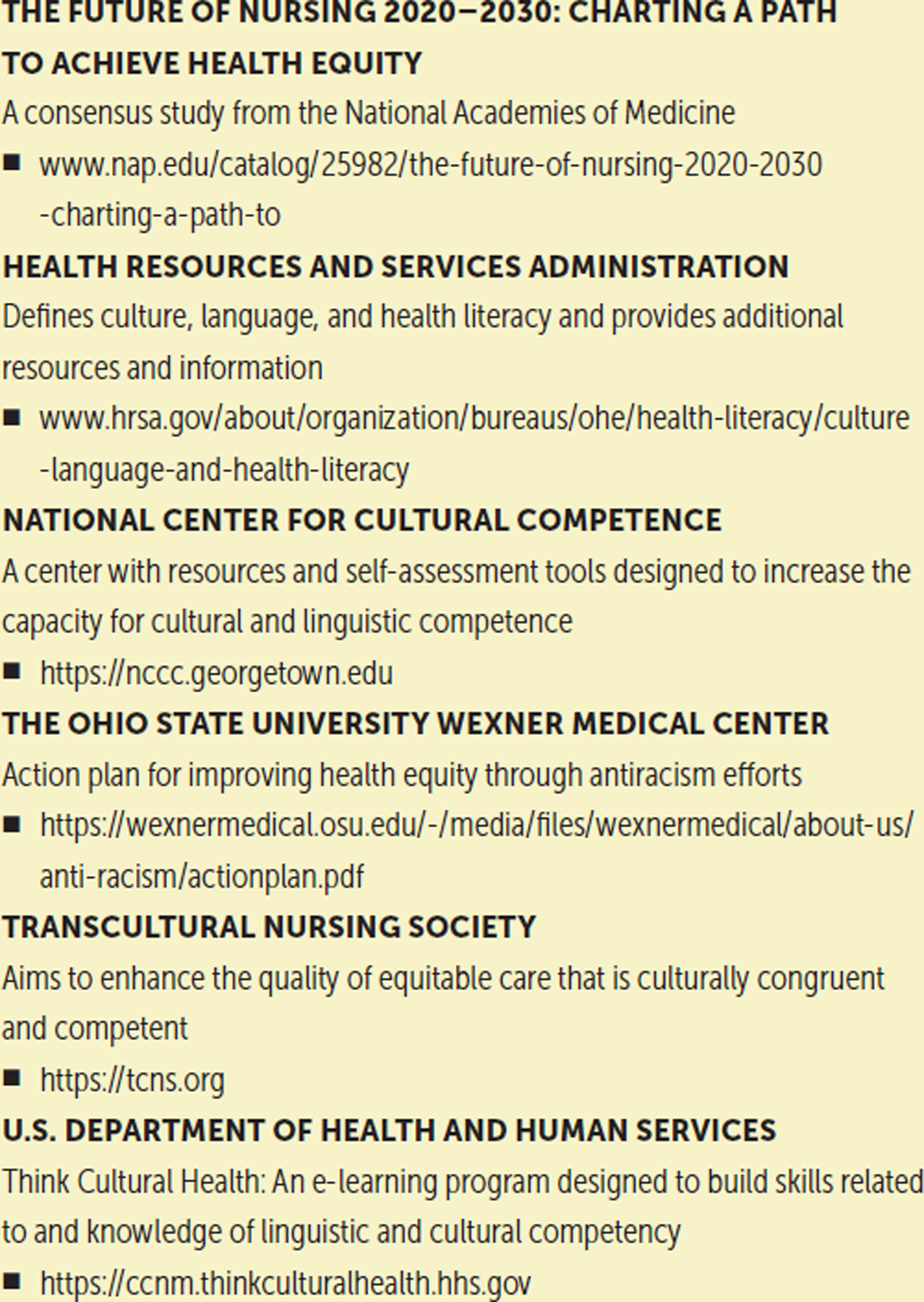

By abiding in humble, anti-biased nursing practice, nurses can partner with patients to reduce barriers to health care and increase the potential to create health equity. For more resources on employing cultural competence and humility, see Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

CULTURAL COMPETENCY AND HUMILITY TRAINING RESOURCES FOR NURSES

Implications for Nursing

Cultural humility in nursing promotes health equity through the lifelong operationalization of cultural competence and sensitivity, while acknowledging others’ personal capacities for health. In turn, nurses can exercise their ethical responsibility to manage implicit and explicit biases and devote themselves to the welfare of those in their care (American Nurses Association, 2015). Considering that health outcomes like patient safety are at stake, the entire cadre of nursing professionals is responsible for supporting the infusion of cultural humility throughout the nursing pipeline and the nursing workforce. Nurses can evolve and equip themselves to take care of all patients, enlarging and using their entire scope of practice. A top-down and bottom-up approach can prevent rather than react to biased and discriminatory nursing practices. Johnson-Mallard et al. (2019) found among a group of nurse scholars that the personal and professional risks that one takes in the name of diversity, equity, and inclusion championing are best mitigated when support and initiatives are driven by nursing leadership. For example, nursing faculty and clinical leadership traditionally mandate annual trainings on cultural competency as a top-down approach. Unfortunately, there is no strong evidence for implicit bias training. Maina et al. (2018) found two studies that assessed the effect of training on implicit bias; of these, only one found a significant difference in behavior post-training. Therefore, more research is needed to design interventions that promote cultural humility that is required to overcome biases and provide the highest quality of health care.

A bottom-up approach stemming from those who are not faculty or in leadership positions may be a viable intervention. Examples of bottom-up approaches include nursing students (under the supervision of a faculty mentor) creating a nursing students of color organization to support the upward movement of diverse students in a predominately White institution, as well as staff nurses creating an action coalition against racism to learn about and advocate for anti-racist policies that have meritorious implications. A midwestern academic health system implementing both top-down and bottom-up approaches reported reductions in patient mortality and closing gaps in racial disparities (Gray et al., 2021).

Training nursing students and the existing workforce to identify and mitigate biases is possible (Schultz & Baker, 2017). As a profession, time can be dedicated to learning and engaging in cultural humility despite other competing demands. This is a patient safety issue, and cultural humility is at the heart of patient-centered care. Workforce diversity, both in education and clinical practice, is an important tool to ensure cultural humility (Wakefield et al., 2021). However, workforce diversity alone cannot carry the profession of nursing across the finish line to health equity. It is the responsibility of every nurse to promote cultural humility and look toward health equity. Each nurse can provide nursing care in a manner that communicates with respect and compassion, acknowledges the patient as a partner, recognizes that the patient is part of social environments that can influence health, and honors diversity, equity, and inclusion. Alignment of the clinical care of patients with cancer with transcultural nursing models is warranted.

Conclusion

Retraining and retooling the nursing pipeline and workforce promotes multiculturalism in oncology care, thereby increasing the opportunities for providing more appropriate patient-centered care for individuals living with cancer. Major initiatives to shift nursing as a profession toward the ever-present goal of delivering high-quality cancer care include increasing diversity among nursing faculty and staff, enhancing nursing curricula and continuing education, and building equitable partnerships to support patient-centered care for all individuals.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE.

Exercise ethical responsibility to identify and reduce implicit and explicit biases while caring for patients.

Foster an environment of patient safety through the provision of culturally humble care in the hospital, clinic, and community.

Advocate for and honor the enrichment that diversity, equity, and inclusion bring to nursing education and the nursing workforce.

Acknowledgments

The authors take full responsibility for this content. Funding was provided by the National Cancer Institute (K08CA245208 [Nolan]). The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias.

Contributor Information

Timiya S. Nolan, College of Nursing at the Ohio State University in Columbus..

Angela Alston, College of Nursing at the Ohio State University in Columbus..

Rachel Choto, College of Nursing at the Ohio State University in Columbus..

Karen O. Moss, College of Nursing at the Ohio State University in Columbus..

REFERENCES

- Adams LT, Campbell J, & Deming K (2017). Diversity: A key aspect of 21st century faculty roles as implemented in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nurse Faculty Scholars program. Nursing Outlook, 65(3), 267–277. 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz KI, Wiedt TL, Daniels EC, Yabroff KR, Guerra CE, & Wender RC (2020). Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: A blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(1), 31–46. 10.3322/caac.21586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2017). Nursing faculty: A spotlight on diversity. https://www.aacnnursing.org/portals/42/policy/pdf/diversity-spotlight.pdf

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2021). The essentials: Core competencies for professional nursing education. https://bit.ly/3yANc8h

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. https://bit.ly/3jzCk4c

- Andrews M, Backstrand JR, Boyle JS, Campinha-Bacote J, Davidhizar RE, Doutrich D, … Zoucha R (2010). Chapter 3: Theoretical basis for transcultural care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 21(4, Suppl.), 53S–136S. 10.1177/1043659610374321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campesino M, Saenz DS, Choi M, & Krouse RS (2012). Perceived discrimination and ethnic identity among breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39(2), E91–E100. 10.1188/12.ONF.e91-e100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J (2002). The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: A model of care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(3), 181–184. 10.1177/10459602013003003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriere R, Adam R, Fielding S, Barlas R, Ong Y, & Murchie P (2018). Rural dwellers are less likely to survive cancer—An international review and meta-analysis. Health and Place, 53, 219–227. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn D, & Caumont A (2016, March 31). 10 demographic trends shaping the U.S. and the world in 2016. Pew Research Center. https://pewrsr.ch/3xApOXl [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics [1989]. In Bartlett KT & Kennedy R (Eds.), Feminist legal theory: Readings in law and gender (pp. 57–80). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Diamant AL, Wold C, Spritzer K, & Gelberg L (2000). Health behaviors, health status, and access to and use of health care: A population-based study of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women. Archives of Family Medicine, 9(10), 1043–1051. 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlberg B, Foronda C, & Baptiste D (2016). Cultural humility: The key to patient/family partnerships for making difficult decisions. Nursing, 46(9), 14–16. 10.1097/01.nurse.0000490221.61685.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald C, & Hurst S (2017). Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 18(1), 19. 10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger JN, & Davidhizar R (2002). The Giger and Davidhizar transcultural assessment model. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(3), 185–188. 10.1177/10459602013003004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales FA, Sangaramoorthy M, Dwyer LA, Shariff-Marco S, Allen AM, Kurian AW, … Gomez SL (2019). Patient-clinician interactions and disparities in breast cancer care: The equality in breast cancer care study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 13(6), 968–980. 10.1007/s11764-019-00820-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DM II, Glover A, Paz H, White S, Dhavai R, Pfeifle A, … Joseph JJ (2021). Health equity and anti-racism report: HEAR 2021. The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and Health Science Colleges. https://bit.ly/3jIuR36 [Google Scholar]

- Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, Scott VK, Swoboda SM, Zogg CK, … Cooper LA (2015). Unconscious race and class biases among registered nurses: Vignette-based study using implicit association testing. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 220(6), 1077–1086. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.01.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, … Coyne-Beasley T (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e60–e76. 10.2105/ajph.2015.302903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes MA, & Smedley BD (Eds.). (1999). The unequal burden of cancer: An assessment of NIH research and programs for ethnic minorities and the medically underserved. National Academies Press. 10.17226/6377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, & Stovall E (Eds.). (2005). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. National Academies Press. 10.17226/11468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jetty A, Jabbarpour Y, Pollack J, Huerto R, Woo S, & Petterson S (2021). Patient–physician racial concordance associated with improved healthcare use and lower healthcare expenditures in minority populations. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s40615-020-00930-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Mallard V, Jones R, Coffman M, Gauda J, Deming K, Pacheco M, & Campbell J (2019). The Robert Wood Johnson nurse faculty scholars diversity and inclusion research. Health Equity, 3(1), 297–303. 10.1089/heq.2019.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jojola CE, Cheng H, Wong LJ, Paskett ED, Freund KM, & Johnston FM (2017). Efficacy of patient navigation in cancer treatment: A systematic review. Journal of Oncology Navigation and Survivorship, 8(3), 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, & Ganz PA (Eds.). (2013). Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis. National Academies Press. 10.17226/18359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftin C, Newman SD, Gilden G, Bond ML, & Dumas BP (2013). Moving toward greater diversity: A review of interventions to increase diversity in nursing education. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 24(4), 387–396. 10.1177/1043659613481677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, & Johnson TJ (2018). A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Social Science and Medicine, 199, 219–229. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan MC (2019). CE: Addressing implicit bias in nursing: A review. American Journal of Nursing, 119(7), 36–43. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569340.27659.5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. (2019). 2018 national sample survey of registered nurses: Brief summary of results. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce. https://bit.ly/3CzTrM8 [Google Scholar]

- Nolan TS, Browning K, Vo JB, Meadows RJ, & Paxton RJ (2020). Assessing and managing spiritual distress in cancer survivorship. American Journal of Nursing, 120(1), 40–47. 10.1097/01.naj.0000652032.51780.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nursing Workforce Reauthorization Act of 2019, H.R. 728, 116th Cong. (2019). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/728/text

- Poulson M, Cornell E, Madiedo A, Kenzik K, Allee L, Dechert T, & Hall J (2021). The impact of racial residential segregation on colorectal cancer outcomes and treatment. Annals of Surgery, 273(6), 1023–1030. 10.1097/sla.0000000000004653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, Vadaparampil ST, Nguyen GT, Green BL, … Schabath MB (2015). Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 65(5), 384–400. 10.3322/caac.21288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz PL, & Baker J (2017). Teaching strategies to increase nursing student acceptance and management of unconscious bias. Journal of Nursing Education, 56(11), 692–696. 10.3928/01484834-20171020-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay CM, Ning H, Allen NB, Carnethon MR, Chiuve SE, Greenlund KJ, … Lloyd-Jones DM (2012). Status of cardiovascular health in US adults: Prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2003–2008. Circulation, 125(1), 45–56. 10.1161/circulationaha.111.035733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KD, Alcaraz KI, Kamson C, Fallon EA, & Smith TG (2016). Sociodemographic inequalities in barriers to cancer pain management: A report from the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II). Psycho-Oncology, 25(10), 1212–1221. 10.1002/pon.4218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, Mitra N, Shults J, Shin DB, & Sawinski DL (2020). Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Network Open, 3(11), e2024583. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, & Murray-García J (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). 2017 national population projections tables: Main series. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://bit.ly/3CwQBYd [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). United States. https://bit.ly/3xAbA8V

- Wakefield M, Williams DR, Le Menestrel S, & Flaubert JL (Eds.). (2021). The future of nursing 2020–2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zestcott CA, Blair IV, & Stone J (2016). Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: A narrative review. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 19(4), 528–542. 10.1177/1368430216642029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]