Abstract

Perspective-taking, whether through imagination or virtual-reality interventions, seems to improve intergroup relations; however, which intervention leads to better outcomes remains unclear. This preregistered study collected measures of empathy and race bias from 90 participants, split into one of three perspective-taking groups: embodied perspective-taking, mental perspective-taking, and a control group. We drew on virtual-reality technology alongside a Black confederate across all conditions. Only in the first group, participants got to exchange real-time viewpoints with the confederate and literally “see through the eyes of another.” In the two other conditions, participants either imagined a day in the life of the Black confederate or in their own life, respectively. Our findings show that, compared with the control group, the embodied perspective-taking group scored higher on empathy sub-components. On the contrary, both perspective-taking interventions differentially affected neither explicit nor implicit race bias. Our study suggests that embodiment of an outgroup can enhance empathy.

Keywords: Perspective-taking, empathy, intergroup relations, implicit bias, prejudice

Cultivating and sustaining harmonious and positive intergroup relations remains a substantial challenge for many increasingly multicultural countries, especially given the growing refugee crisis (Esses et al., 2017). Prejudice and discrimination, in particular, represent central threats to intergroup harmony (“Consequences of prejudice,” 2007). Research also suggests that prejudice based on race seems deeply embedded within the human brain (Amodio, 2014; Kubota et al., 2012; Molenberghs, 2013). And yet, evidence also shows that such attitudes—even unconscious or implicit—are malleable; they can change with interventions such as diversity education (Dasgupta, 2013; Forscher et al., 2019; Rudman et al., 2001). Whereas explicit attitudes refer to conscious or deliberately reported positive (or negative) evaluations, implicit attitudes refer to more unconscious or automatic forms (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; Rydell & McConnell, 2006). One meta-analysis identified a small correlation of .24 between implicit and explicit attitudes, although more spontaneous self-reports and more conceptual correspondence between measures strengthens this relationship (Hofmann et al., 2005). Implicit and explicit attitudes also show incremental predictive validity—they contribute to behaviour in different and complementary ways (Greenwald et al., 2009; Kurdi et al., 2019). For these reasons, it is important to measure both implicit and explicit attitudes.

Researchers seek strategies to successfully reduce both explicit and implicit prejudice as well as increase empathy, tolerance, and understanding of others. To this end, empathy serves as a remedy to prejudice because of its capacity to improve attitudes (Finlay & Stephan, 2000) and link with a wide range of interindividual benefits, including altruism (Krebs, 1975), cooperation in social dilemmas (Rumble et al., 2010), and prosocial behaviour (Batson & Ahmad, 2009; Eisenberg & Miller, 1987; Hoffman, 2008; Zaki, 2018). Despite globally concerted efforts to achieve these goals, researchers persist in their attempt to identify the most effective and sustainable procedures to reduce implicit prejudice and improve intergroup relations (e.g., Lai et al., 2014, 2016). The current study investigates the impact of two different perspective-taking strategies on empathy and the reduction of racial prejudice.

Perspective-taking

Perspective-taking, or “seeing through the eyes of another,” has emerged as a promising intervention to reduce prejudice (Stephan & Finlay, 1999; Todd & Galinsky, 2014). Interventions based on perspective-taking might, for example, ask participants to imagine a day in the life of an outgroup individual displayed in a photograph. Researchers have shown perspective-taking to reduce conscious and non-conscious stereotypes, in-group favouritism (Dovidio et al., 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000), and implicit race bias (Todd & Burgmer, 2013; Todd et al., 2011; see Forscher et al., 2019, for a recent meta-analysis). Scientists have also shown perspective-taking to increase self–other merging (how much of your sense of self overlaps with the other person), one of the hypothesised mechanisms through which perspective-taking interventions reduce prejudice (Galinsky et al., 2005; Maister et al., 2015; Todd & Burgmer, 2013). Finally, studies have also shown perspective-taking to increase empathy (Batson, Early, & Salvarani, 1997; Batson, Polycarpou, et al., 1997; Crabb et al., 1983; Erera, 1997; Pacala et al., 1995; Pinzone-Glover et al., 1998; Todd & Burgmer, 2013).

Other researchers have questioned whether perspective-taking can remedy prejudice. For example, researchers analysed 492 implicit bias reduction studies involving 87,418 participants and found widespread publication bias on the topic (Forscher et al., 2019). Similarly, in a seminal replication effort drawing on 17,021 participants, 15 labs proposed interventions of their choice; only 8 out of the 17 interventions successfully changed implicit attitudes (Lai et al., 2014). The most perspective-taking-like conditions were ineffective: (a) perspective-taking itself (Cohen’s d = −.04), (b) training empathic responding (d = −.02), and (c) imagining interracial contact (d = .01). Historically, furthermore, researchers construed perspective-taking as an intentional, controlled process, mobilising imagination and other higher cognition (mental perspective-taking [MPT]; Davis et al., 1996; Roxβnagel, 2000). In some situations, insufficient motivation to engage in this mental effort typically makes the act of taking the perspective of another person even more challenging (Gehlbach et al., 2012; Hodges & Klein, 2001; Webster et al., 1996; Zaki, 2014). This pattern serves as a limiting factor to practical utility, reliability, and applicability. Whether perspective-taking effectively reduces prejudice and increases empathy remains unclear.

As an intervention, alterations in body-ownership may carry fewer limitations than MPT. In the case of specific body parts, inducing ownership over fake parts of the anatomy has made for an important discovery (Botvinick & Cohen, 1998). For example, concurrent stimulation instigates the illusion of ownership over an artificial (rubber) limb, or a digital face, even with incongruent skin colour (Farmer et al., 2012, 2014; Fini et al., 2013; Maister, Sebanz, et al., 2013). Processing such multisensory stimulation, the human brain rapidly integrates the foreign part into the body schema, albeit that fake body part may associate with an outgroup (Maister et al., 2015). Going beyond specific body parts, with virtual reality equipment, individuals can experience the illusion of embodying a virtual character (e.g., a computer-generated person). Again, this robust phenomenon persists even with a range of incongruent features, including skin colour (Banakou et al., 2016; Groom et al., 2009; Peck et al., 2013). As a result, scientists can lead White participants to identify with, view the world through the lens of, and experience the virtual image (avatar) of a Black individual (Peck et al., 2013).

This embodied perspective-taking (EPT) methodology affords probing the visuo-spatial perspective of an outgroup individual in a more embodied and automatic form. Moreover, information concerning the perspective of the other person feeds from the senses and, in contrast to traditional perspective-taking interventions, feels natural and requires little conscious effort. Importantly, such interventions affect social cognition and outgroup attitudes (Farmer & Maister, 2017). To be sure, EPT effectively reduces implicit race bias (Banakou et al., 2016; Farmer et al., 2012, 2014; Maister, Banissy, & Tsakiris, 2013; Peck et al., 2013 but see Groom et al., 2009) and even increases empathy (Herrera et al., 2018; van Loon et al., 2018). Collectively, these findings suggest that parameters related to body ownership shape outgroup attitudes by overlapping the sense of self with that of the other on an unconscious level (Maister et al., 2015). At least one study showed that EPT reversed an in-group bias effect, based on mimicry, regardless of implicit attitudes (Hasler et al., 2017), whereas most other studies found no or little effect on explicit bias (Ahn et al., 2013; Groom et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2016; Peck et al., 2013; Yee & Bailenson, 2006). The dissociation of explicit and implicit attitudes may uncover distinct underlying mechanisms: implicit attitudes may rely more on automatic, associative processes, while explicit ones may depend on evaluative, propositional reasoning processes (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; Rydell & McConnell, 2006). It remains unclear whether, how, and to what extent these perspective-taking interventions rely on such mechanisms, and whether we can practically change attitudes. The present piece represents our effort to address this question.

MPT versus immersive embodiment experiences

Whereas researchers have independently shown both MPT and EPT methodologies to reduce prejudice (with some conflicting findings), they have only recently directly compared the effects of traditional MPT with virtual reality-based immersive embodiment experiences on prosocial and intergroup cognition and behaviour. This kind of comparison matters, because it can inform the development of future interventions aimed at maximising potential effects and help understand the contribution of the mechanisms of these methods. For instance, researchers have on one hand shown an advantage of EPT over MPT on self–other merging, attitudes and dehumanisation (delayed improvement), empathy (empathic concern and personal distress), intention to communicate with the outgroup, likelihood to sign a petition, and amount of time spent helping (Ahn et al., 2013; Herrera et al., 2018; Oh et al., 2016). On the other hand, researchers have also found that EPT and MPT hardly differed in terms of the positivity of the relationship with a virtual character, implicit or explicit bias, reading emotions of other people accurately, behaviour in a negotiation task, or donation amount (Ahn et al., 2013; Gehlbach et al., 2015; Groom et al., 2009; Herrera et al., 2018; Oh et al., 2016).

Although the few studies comparing EPT and MPT suggest a modest advantage of EPT in promoting prosocial cognition and behaviour, they have several limitations. Few of these studies specifically compared the effects of EPT and MPT on empathy as well as implicit and explicit bias. Thus, the effect of MPT versus EPT on these measures of empathy and prejudice remains unclear. Furthermore, none of these studies used a high-realism, real-time body exchange methodology, as well as a closely matched, procedurally similar control group. The most realistic methodology normally used involves a computer-generated virtual body. Yet, we might expect a more realistic illusion of embodiment, for example, through the embodiment of the real body of another person, to yield a stronger impact on prosocial cognition and behaviour. Indeed, body prostheses with more realistic hand structure or skin texture produce stronger illusions of embodiment (Kilteni et al., 2015; Tsakiris et al., 2010) and greater immersion links to greater empathy (van Loon et al., 2018).

Present study

In this study, we aimed to address the limitations of the literature to compare the effects of MPT and EPT on empathy and prejudice. To this end, we compared three conditions: (a) traditional MPT, (b) a highly realistic form of EPT, and (c) a control group. Importantly, the new EPT methodology used in this study, the “body-swap illusion” (Petkova et al., 2008), rests on the real-time exchange of the viewpoint of the participant with another person—here, a Black confederate (see “Method” section for details). This project used a system developed by The Machine to Be Another group that allows two individuals to exchange their visual perspective (Bertrand et al., 2014). Using virtual reality headsets and cameras, this international group of artists, activists, and scientists, applies this technology to pursue interdisciplinary projects (beanotherlab.org). To our knowledge, no other study has experimentally examined whether this body-swap paradigm can increase empathy and reduce prejudice. Following the perspective-taking intervention, participants completed measures of empathy and explicit and implicit race attitudes. Our research questions were thus: Can MPT and EPT, compared with a control group, foster empathy as well as reduce explicit and implicit prejudice? If so, which perspective-taking method most effectively achieves these goals? Answering these questions will help guide the development of future interventions and the theory behind perspective-taking and prosocial cognition.

Hypotheses

Given the evidence that higher simulation realism and immersion increases the strength of bodily illusions (Kilteni et al., 2015) as well as the benefits of perspective-taking (Ahn et al., 2013; van Loon et al., 2018), we hypothesised that embodiment methodologies characterised by more realism and immersion should be more efficient at increasing empathy and reducing prejudice compared with traditional perspective-taking. Furthermore, given the distinct mechanisms of explicit and implicit attitude change (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; Rydell & McConnell, 2006), we reasoned that the deliberate and effortful processing involved in cognitively taking the perspective of someone else in MPT should affect explicit attitudes by engaging more propositional reasoning processes. Furthermore, the perceptually induced shared body representation in EPT should affect implicit attitudes by engaging more associative processes (Kilteni et al., 2015; Maister et al., 2015). We therefore predicted that (a) both the EPT and MPT groups would show more empathy as well as lower implicit and explicit prejudice, compared with the control group; (b) the EPT group would show greater empathy and lower implicit prejudice compared with the MPT group, and (c) the MPT group would show lower explicit prejudice compared with the EPT group.

Method

Participants

We preregistered our study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, variables, and hypotheses and analyses regarding empathy and explicit and implicit race bias online (https://osf.io/cws8g/). 1 We disclose all measures, manipulations, and exclusions in the study, as well as the method of determining the final sample size (collection was not continued after data analysis). Given the resource-intensive nature of this study, we were only interested in detecting large effect sizes making the effort worthwhile. Accordingly, for feasibility reasons and in line with our preregistration, we ran 30 participants per group (total of 90), which, with 80% power and a .05 alpha, enables the detection of large effect sizes (d ⩾ 0.74). Although the study had relatively small power, we were limited by feasibility and wanted to explore whether this research avenue showed any evidence that it was worth pursuing. Because of this limited sample size, although preregistered, this study represents a somewhat preliminary research effort.

We recruited 98 participants (18–35 years, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and without any history of psychiatric or neurological disorders) via social media postings for a “virtual reality and cognition” study. As outlined in the preregistration, we excluded three participants who displayed faint understanding of the instructions (e.g., being clearly out of sync with the confederate, not understanding English well, or looking excessively tired). We also excluded from the main analysis data collected from five Black participants because the intervention targets prejudice against Black individuals. 2 This left a final sample size of 90 participants with a mean age of 22.2 years (SD = 3.0): 71% female, 29% male; 87% students; 50% White, 26% Asian, 17% South-Asian, and 7% other. 3 We included non-White and non-Black participants because they typically show levels of implicit race bias against Black individuals comparable to White individuals (Nosek et al., 2002). Due to experimenter error, one participant did not complete one questionnaire (the Interpersonal Reactivity Index) and was excluded from analyses using that variable. The Research Ethics Board approved this study prior to data collection.

Procedure

A White male experimenter (24 years of age) initially welcomed the participant and a sex-matched Black confederate. Participants had no knowledge that the Black person was our research associate for the study. The experimenter and confederate employed deception tactics throughout to maintain the study integrity (Olson & Raz, 2021). 4 We randomly assigned participants to one of three groups: EPT, MPT, and a control group. After obtaining consent, we made participants believe that we were taking a photograph of each of them separately, “to use later in the experiment.” This move was important for the perspective-taking intervention in the MPT condition (described below). For consistency, participants from all groups went through this ruse.

Participants then entered the testing area and set up their virtual-reality headset with the help of the experimenter. All groups used the same virtual-reality head-mounted display system. Whereas participants in the EPT group saw the visual image captured by the camera on the headset of the confederate, participants in the MPT and control groups simply saw the visual image captured by the camera on their own headset. The experimenter then read a script with instructions about specific motor movements that participants had to perform, and which were identical for all groups (section S1). These movements were necessary to induce the multisensory illusion for the EPT group; however, again, for consistency, participants from all groups performed these actions. At one crucial point during the instructions (after approximately 5 min), the experimenter removed the curtains hiding the mirrors in front of the participants and read the experimental intervention according to the experimental condition (detailed below). This part of the experiment lasted about 10 min.

After each group intervention, participants completed the following measures (in this order): experimental intervention check, Implicit Association Test, Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale, Symbolic Racism Scale, Interpersonal Reactivity Index, and Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. To address a separate research question, participants then completed the Self-Concept Clarity Scale (Campbell et al., 1996), but these results are reported separately elsewhere (Krol et al., 2019). Finally, participants reported their understanding of the purpose of the study. In total, the experiment took 1 hr.

Perspective-taking interventions

EPT

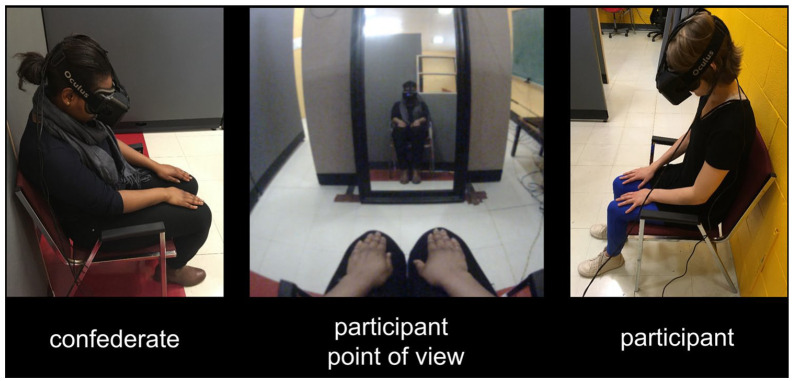

Participants in the EPT group experienced a type of illusion originally described as “body swapping” (Petkova et al., 2008). In this methodology, both a participant and a Black confederate wear a virtual-reality headset with a camera attached to the headset at eye level. Critically, the system sends the image from the camera to the headset of the other person, so that the participant “sees through the eyes” of the confederate, and vice versa (Bertrand et al., 2014, 2018; De Oliveira et al., 2016). Synchronised movements from both users result in an illusion of body ownership analogous to other bodily illusions (e.g., Botvinick & Cohen, 1998). Looking down at their hands or straight at a mirror, participants would see the hands or reflection of the Black confederate in place of their own hands or reflection (Figure 1). 5 Using this set-up, participants typically experience their body as that of a Black person. Upon revealing the mirrors, the experimenter instructed: “For the next minute, look at yourself in the mirror in front of you.” We adapted these instructions, including the 1-min duration, from Oh et al. (2016); they closely follow those of classic perspective-taking interventions (e.g., Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000).

Figure 1.

Body-swap set-up.

Note. Left: Confederate looking down at her hands. Middle: Participant point of view, seeing the confederate’s hands and image reflection, instead of her own. Right: Participant looking down at her hands.

The experimenter additionally stated to participants that they were randomly assigned “roles” to make things easier, with the confederate always obtaining the “leader” role and the participant the “follower” role. The experimenter then explained that instructions applied to the both of them, but that the leader (i.e., the confederate) would initiate the movements first, while the follower (i.e., the participant) would need to stay synchronised with the leader.

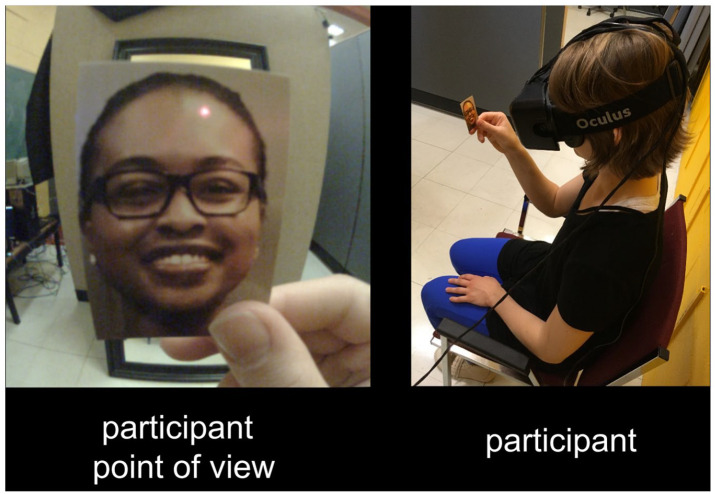

MPT

Upon revealing the mirrors, for participants in the MPT group only, the experimenter handed a photograph of the confederate (Figure 2). The experimenter then instructed: “For the next minute, take the perspective of the individual in the photograph. Imagine a day in the life of this individual as if you were that person, looking at the world through her/his eyes and walking through the world in her/his shoes” (Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Oh et al., 2016). The setup led participants to believe that the confederate engaged simultaneously in the procedure on the other side of the partition. For consistency, we printed all photographs of the confederates in advance. The role of the picture was to act as a visual aid, replicating previous perspective-taking methodologies (Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Oh et al., 2016; Todd & Burgmer, 2013; Todd et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Mental perspective-taking set-up.

Note. Participant looking down at the photograph of the confederate, allegedly taken at the beginning of the session.

Control group

Upon revealing the mirrors, the experimenter instructed participants in the control group: “For the next minute, take the time to let your mind wander. Imagine a day in your life, looking at the world through your eyes and walking through the world in your shoes” (adapted from Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Oh et al., 2016).

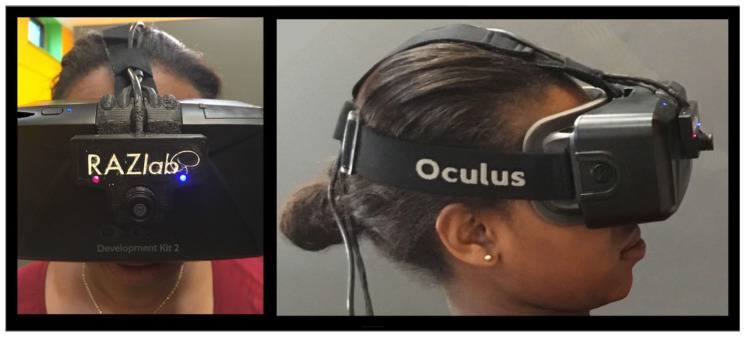

Materials

We used the Oculus Rift Development Kit 2 (DK2) as the virtual-reality headset/head-mounted display (Desai et al., 2014). The headset contains two small screens inside, with resolutions of 960 × 1080 per eye and a refresh rate of 75 Hz, resulting in horizontal and vertical fields of view of approximately 100° of visual angle. To generate the body-swap illusion, we used a software called “The Machine to Be Another,” developed by BeAnotherLab (Bertrand et al., 2018). 6 We also modified the head-mounted display device (Figure 3) by attaching a modified PlayStation 3 camera with a custom 3D printed structure (Sony Computer Entertainment, 2007).

Figure 3.

Head-mounted display.

Note. Oculus Rift Development Kit with PlayStation 3 camera and custom 3D-printed component. Frontal and side views.

Measures

Intervention validity

To confirm the validity of our experimental interventions, we created questionnaires for each condition that assessed the extent to which participants followed instructions and engaged in the experimental task. Participants in the EPT group rated the degree to which they experienced the body-swap illusion by answering a questionnaire assessing the feeling of ownership over the perceived body (section S2). To this end, we adapted a questionnaire measuring body ownership in the rubber hand illusion (Longo et al., 2008). Example items of this adapted questionnaire include: “It seemed like I was looking directly at my own body, rather than at someone else’s body” and “It seemed like I could have moved the body I saw if I had wanted.” We created analogous control statements for the two other groups (e.g., “I feel like I was imagining being in the other participant’s skin,” section S3; “I imagined living a day in my life,” section S4).

Inclusion of the Other in the Self Scale (IOS)

Participants also rated their levels of self–other overlap and feelings of closeness with the confederate (Aron et al., 1992). In this scale, participants select the instance that best represents their relationship with the confederate from seven variants of two increasingly overlapping circles. The first two circles share no overlap, whereas the last two circles overlap almost completely.

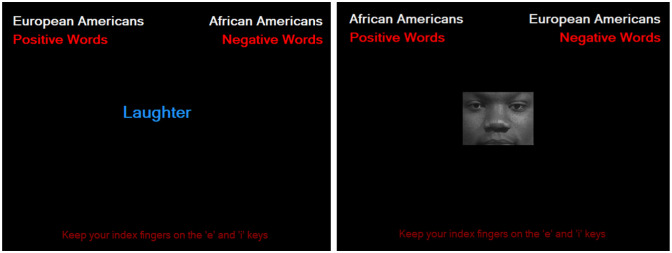

Implicit racial bias

We measured implicit racism with the Implicit Association Test (Greenwald et al., 1998, 2003; McConnell & Leibold, 2001), which measures the strength of automatic associations by comparing reaction times with various probes related to ethnicity (see Figure 4). We administered the IAT using the FreeIAT software (Meade, 2009), without counterbalancing by design (Meade, 2020). 7 We used 50 trials per block (5 blocks) and the words and photo stimuli preloaded with the software. The FreeIAT software provides an IAT score (or D-score) using the improved scoring algorithm developed by Greenwald et al. (2003), which we used for our analyses.

Figure 4.

Screenshots of sample stimuli from the FreeIAT (Implicit Association Test).

Note. Left: Participants need to categorise the word laughter as a positive word. Right: Participants need to categorise the individual’s photograph as “African American.”

Explicit racial bias

We measured explicit racism with the Symbolic Racism Scale (Henry & Sears, 2002; Sears & Henry, 2005), a psychometrically improved version of the Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986). We changed items 3, 4, and 5 to use a single response scale for all questions (section S5), so that participants stated their agreement from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). We also adapted the wording of certain items to the Canadian context (e.g., “Blacks are responsible for creating much of the racial tension that exists in Canada today”).

Empathy

We measured empathy via the classic Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1983) as well as with the more recent Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE; Reniers et al., 2011). We used these measures of empathy because they are well-validated, easy to administer, and index intervention outcomes (e.g., Erera, 1997; Pacala et al., 1995; Pinzone-Glover et al., 1998 also see Stepien & Baernstein, 2006, for a review, and Teding van Berkhout & Malouff, 2016, for a meta-analysis). The IRI has four subscales: perspective-taking (e.g., “Before criticising somebody, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place”), fantasy (e.g., “I really get involved with the feelings of the characters in a novel”), empathic concern (e.g., “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me”), and personal distress (e.g., “When I see someone who badly needs help in an emergency, I go to pieces”).

The QCAE measures cognitive empathy, the ability to represent the mental experiences of other people, and affective empathy, the ability to experience emotions of other people. It comprises five subscales: perspective-taking (e.g., “I can sense if I am intruding, even if the other person does not tell me”) and online simulation (e.g., “I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective”), which relate to the cognitive empathy component, and emotion contagion (e.g., “I am happy when I am with a cheerful group and sad when the others are glum”), proximal responsivity (e.g., “I often get emotionally involved with my friends’ problems”), and peripheral responsivity (e.g., “I often get deeply involved with the feelings of a character in a film, play or novel”), which relate to the affective empathy component.

Principal component analysis of the empathy items

We note that employing more than one questionnaire to measure a single construct is rather unusual and deserves clarification. On one hand, we wanted to employ the most used empathy scale in the field, the IRI—considered by some as the gold standard measure of empathy. On the other hand, the IRI has known problems regarding model fit, validity, and conceptual clarity (Baldner & McGinley, 2014), so we also elected to use a newer empathy scale with better psychometric properties. We chose the QCAE as a second scale because it has appropriate reliability and validity (construct and convergent), and because it is one of the few multidimensional scales available (i.e., it measures both the cognitive and affective dimensions of empathy).

To overcome the limitation of using two scales for a single construct, we report, in supplementary materials, a (non-preregistered) principal component analysis of all 59 empathy items (comprising both scales, section S10; Supplemental Table S6 for loadings). We also report the results of the planned contrast analyses conducted with the identified components (Supplemental Table S7), accompanying figures (Supplemental Figure S4), as well as the correlations between those empathy components, embodiment, and self–other merging (Supplemental Tables S8 and S9).

Statistical analyses

Confirmatory analyses

We used multiple regression with two-tailed planned contrasts, using group (EPT, MPT, control) as the predictor, and empathy, implicit bias, and explicit bias as separate outcomes, with an alpha threshold of .05 for all significance tests. The planned contrasts compared all pairs of groups and we used a robust version of Cohen’s d as a measure of effect size (Algina et al., 2005). We did not use family wise type 1 error correction and encourage readers to consider our results in light of the total number of tests (Althouse, 2016; Feise, 2002; Rothman, 1990). For example, from the 42 contrast comparisons in Table 1, assuming the null hypotheses are all true, approximately two should come up as significant due to chance alone.

Table 1.

Results of multiple regression with planned contrasts analyses for implicit and explicit race bias, empathy subscales, and self–other merging (confirmatory analyses with the exception of self–other merging).

| Variable | Comparison | t | p | d R | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Race bias

(df = 87) |

Implicit race bias (Implicit Association Test) | Embodied–control | 0.735 | .464 | 0.301 | [−0.281, 0.989] |

| Mental–control | −0.126 | .900 | 0.131 | [−0.438, 0.793] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 0.861 | .392 | 0.170 | [−0.223, 0.621] | ||

| Symbolic racism (Symbolic Racism Scale) | Embodied–control | −1.183 | .240 | −0.307 | [−0.873, 0.232] | |

| Mental–control | −1.603 | .113 | −0.414 | [−1.023, 0.099] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 0.420 | .676 | 0.107 | [–0.402, 0.645] | ||

|

Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy

(df = 87) |

Cognitive empathy | Embodied–control | −0.802 | .425 | −0.270 | [–0.891, 0.313] |

| Mental–control | −0.566 | .573 | −0.119 | [–0.666, 0.424] | ||

| Embodied–mental | −0.235 | .814 | −0.151 | [–0.746, 0.43] | ||

| Affective empathy | Embodied–control | 0.912 | .364 | 0.237 | [–0.387, 0.889] | |

| Mental–control | 1.199 | .234 | 0.369 | [–0.189, 1.041] | ||

| Embodied–mental | −0.287 | .775 | −0.132 | [–0.622, 0.342] | ||

| Perspective-taking | Embodied–control | −1.403 | .164 | −0.501 | [–1.116, 0.03] | |

| Mental–control | −0.965 | .337 | −0.261 | [–0.819, 0.279] | ||

| Embodied–mental | −0.437 | .663 | −0.240 | [–0.829, 0.299] | ||

| Online simulation | Embodied–control | 0.103 | .918 | −0.114 | [–0.813, 0.461] | |

| Mental–control | 0.046 | .963 | −0.019 | [–0.496, 0.519] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 0.057 | .955 | −0.095 | [–0.662, 0.397] | ||

| Emotion contagion | Embodied–control | −0.346 | .730 | −0.053 | [–0.649, 0.613] | |

| Mental–control | 0.692 | .491 | 0.102 | [–0.485, 0.663] | ||

| Embodied–mental | −1.038 | .302 | −0.155 | [–0.605, 0.33] | ||

| Proximal responsivity | Embodied–control | 0.561 | .577 | 0.155 | [–0.515, 0.762] | |

| Mental–control | 1.899 | .061 | 0.482 | [–0.105, 1.14] | ||

| Embodied–mental | −1.338 | .184 | −0.327 | [–0.793, 0.107] | ||

| Peripheral responsivity | Embodied–control | 2.196 | .031 | 0.525 | [–0.063, 1.149] | |

| Mental–control | 0.237 | .813 | 0.036 | [–0.55, 0.595] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 1.959 | .053 | 0.489 | [–0.016, 1.036] | ||

|

Interpersonal Reactivity Index

(df = 86) |

Perspective-taking | Embodied–control | 0.122 | .903 | −0.068 | [–0.689, 0.492] |

| Mental–control | 0.019 | .985 | −0.174 | [–0.738, 0.283] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 0.102 | .919 | 0.106 | [–0.441, 0.782] | ||

| Fantasy | Embodied–control | 0.151 | .880 | 0.095 | [–0.451, 0.656] | |

| Mental–control | −1.386 | .169 | −0.355 | [–0.899, 0.117] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 1.536 | .128 | 0.450 | [–0.14, 1.063] | ||

| Empathic concern | Embodied–control | 2.301 | .024 | 0.589 | [0.03, 1.253] | |

| Mental–control | 1.448 | .151 | 0.421 | [–0.048, 1.011] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 0.834 | .407 | 0.168 | [–0.412, 0.765] | ||

| Personal distress | Embodied–control | 2.130 | .036 | 0.480 | [–0.044, 1.12] | |

| Mental–control | 0.858 | .393 | 0.186 | [–0.242, 0.703] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 1.254 | .213 | 0.294 | [–0.296, 0.933] | ||

|

(Exploratory measure)

Inclusion of other in the self (df = 87) |

Embodied–control | 4.708 | <.001 | 1.090 | [0.432, 1.755] | |

| Mental–control | 2.123 | .037 | 0.467 | [–0.034, 1.026] | ||

| Embodied–mental | 2.585 | .011 | 0.623 | [0.000, 1.259] | ||

Note. dR = robust Cohen’s d; CI = bootstrapped confidence interval. The comparisons were between-groups only (i.e., there were no within-subject pre/post comparisons). One participant did not complete the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Bold/Grey background values represent statistically significant differences between the groups on that row and variable.

Exploratory analyses

We also used multiple regression with planned contrasts with self–other overlap. An exploratory regression table and figures are available in section S6.

Assumptions

None of the dependent variables, at the group level, had meaningful deviations from normality (based on quantile–quantile plots) or homoscedasticity (no group had four times the variance of another group).

Software

We performed all statistical analyses in R version 3.4.2 using the following packages: lsmeans (contrast analyses; Lenth, 2016), bootES (effect sizes and bootstrapped confidence intervals; Kirby & Gerlanc, 2013), psych (internal reliability analyses; Revelle, 2018), as well as ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), ggsignif (Ahlmann-Eltze, 2019) and ggpubr (Kassambara, 2019) for graphs.

Results

Descriptive analyses

The self-report intervention check assessed how successfully participants engaged in their respective instructions. The average score was 4.25 across groups (or 61%, based on the maximum score of 7), and it was 4.30, 3.34, and 5.12 for the EPT, MPT, and control groups, respectively (61%, 48%, and 73%). Most primary measures had good reliability (see Supplemental Table S2 in section S7 for internal reliability indices for each multi-item questionnaire). Three participants had relatively extreme values on one test and one participant on two questionnaires, relative to other participants (z-scores ranging from −3.38 to 2.94). Because we had no other reason to exclude these participants, we proceeded with the analyses without further exclusions.

Confirmatory analyses

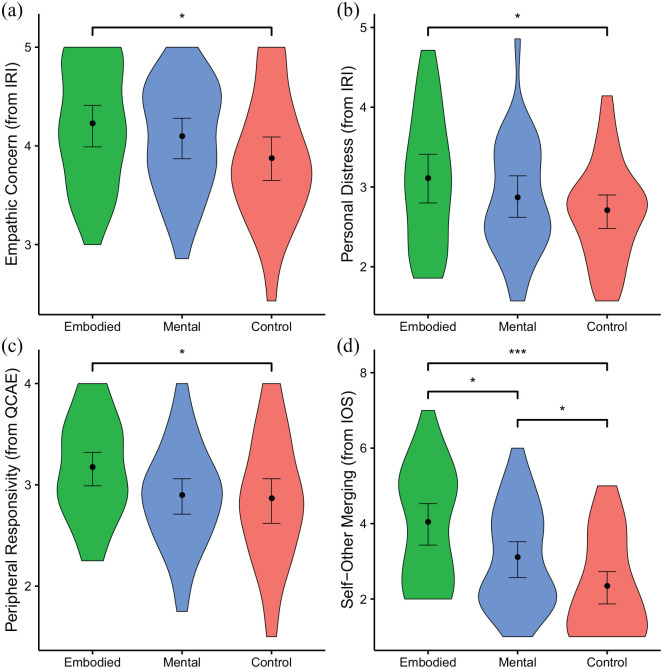

We first hypothesised that the MPT and EPT groups would show more empathy as well as lower implicit and explicit prejudice than the control group. Our results supported some of these predictions (Table 1). Participants in the EPT group generally showed more empathy than those in the control group: they had greater empathic concern (M = 4.21 [4.00, 4.42], 8 Figure 5a), personal distress (M = 3.09 [2.80, 3.40], Figure 5b), and peripheral responsivity (M = 3.16 [2.97, 3.32], Figure 5c) than the control group (M = 3.86 [3.64, 4.08]; M = 2.69 [2.48, 2.93]; M = 2.85 [2.64, 3.04]). This suggests that participants in the EPT group saw themselves as having a stronger urge to help someone in need (empathic concern) and tended to experience more negative emotions when seeing someone in distress (personal distress) compared with those in the control group. It also suggests that participants in the EPT group felt they generally had stronger emotional reactions in less socially involving contexts, such as to characters from novels or movies (i.e., peripheral responsivity, a subcomponent of affective empathy) relative to those in the control group. However, the MPT group did not show more empathy than the control group on any of the measures used. Also contrary to our expectations, the two perspective-taking groups showed no difference in cognitive or affective empathy as defined by the QCAE. Also, they were comparable to the control group on explicit and implicit prejudice (see Table 1).

Figure 5.

Comparison of experimental groups on empathy and self–other merging. (a) Effects of experimental condition on Empathic Concern and (b) Personal Distress (IRI: Interpersonal Reactivity Index), (c) Peripheral Responsivity (QCAE: Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy), and (d) self–other merging (IOS: Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale).

Note. Dots = means; error bars = bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals; width = distribution density (frequency). * = p < .05; *** = p < .001. Empathy was highest in the Embodied Perspective-Taking group.

We had also hypothesised that the EPT group would show greater empathy, lower implicit prejudice, and greater explicit prejudice compared with the MPT group. However, the EPT and MPT groups hardly differed in these dimensions of empathy and explicit and implicit prejudice. Importantly, the implicit prejudice scores were not only similar, but close to zero for all three groups (EPT: 0.06 [−0.03, 0.15], MPT: −0.01 [−0.10, 0.09], CTR: 0.003 [−0.13, 0.13]). Although IAT scores can be negative (i.e., a preference for Black people over White people), practically speaking, these low scores could indicate a type of “floor effect,” as it is ostensibly harder to reverse bias than it is to simply reduce it. Indeed, body-illusion interventions only seem to reduce racial bias for those with a negative initial attitude (Farmer et al., 2014), and most interventions that successfully reduce racial bias do not reverse it (e.g., Forscher et al., 2019; Kurdi et al., 2019; Lai et al., 2014, 2016).

Exploratory analyses

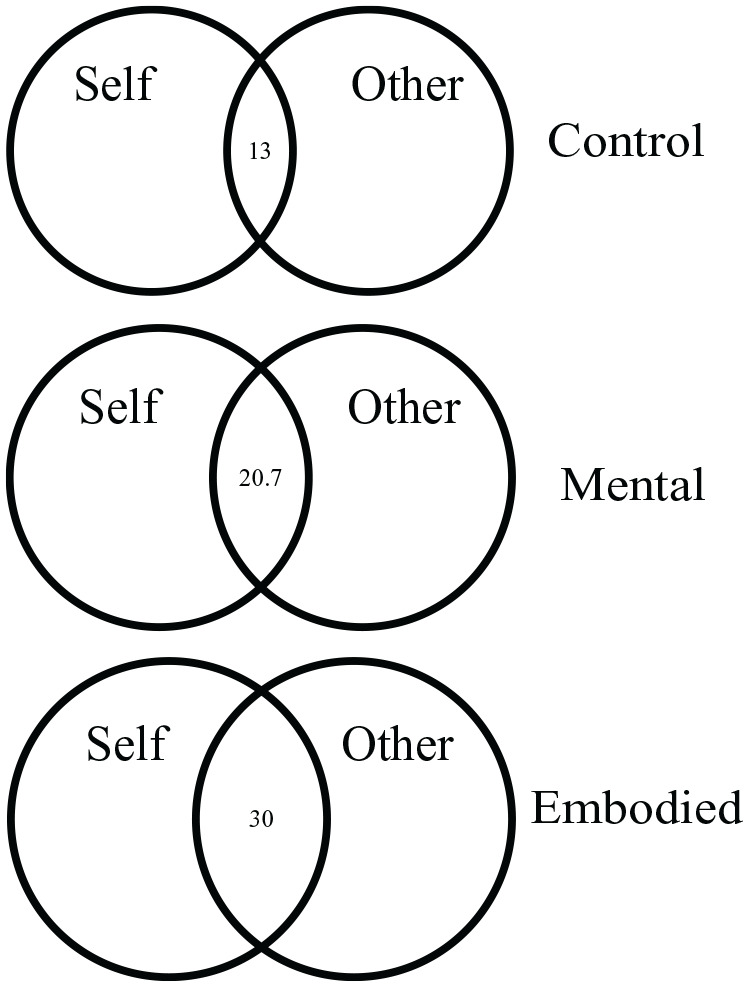

We also looked at the effect of group condition on the inclusion of the confederate in the sense of self of participants (“self–other merging”; see Table 1). Both the EPT (M = 4.00 [3.43, 4.57]) and MPT (M = 3.07 [2.57, 3.57]) group showed greater self–other merging compared with the control group (M = 2.30 [1.81, 2.79]); the EPT group also scored significantly higher on self–other merging than the MPT group (Figures 5d and 6). 9

Figure 6.

Interpolation of the inclusion of the other in the self scale by experimental group.

Note. Circles and numbers represent the average percentage overlap for each group, using linear interpolation from the original Inclusion of the Other in the Self (IOS) scale. Self–other merging was highest in the Embodied Perspective-Taking group, followed by the Mental Perspective-Taking group, followed by the control group.

Discussion

The current investigation aimed to examine which perspective-taking strategy—embodied or mental—most effectively increases empathy and decreases prejudice. We found that participants in the EPT group showed greater empathy and self–other merging towards a Black confederate than those in the control group, while the MPT group similarly showed more self–other merging than the control group. Specifically, participants in the EPT group showed higher empathic concern, personal distress, and peripheral responsivity than those in the control group. Overall, these findings suggest that one can implement brief perspective-taking interventions based on virtual-reality to increase empathy and feelings of closeness. Even without a direct effect of these interventions on race bias, they may indirectly improve intergroup relations through their effects on empathy and closeness. Whereas a mediation analysis would have been appropriate in this case (e.g., testing whether empathy mediates the effect of experimental condition on implicit prejudice), given our low and homogeneous IAT data, such an approach may be less helpful. Future research should investigate this hypothesis.

Empathy

Our EPT intervention led to higher scores of empathic concern, personal distress, and peripheral responsivity compared with the control group. Previous research has shown that perspective-taking generally leads to higher empathy on a variety of measures (Batson, Early, & Salvarani, 1997; Batson, Polycarpou, et al., 1997; Crabb et al., 1983; Erera, 1997; Pacala et al., 1995; Pinzone-Glover et al., 1998). Interestingly, although our EPT group showed higher empathy compared with the control group, our MPT group was comparable to the control group, even though it most closely resembled these previous interventions. In contrast to the current project, many of the previous perspective-taking studies required participants to write a narrative essay about a day in the life of an outgroup individual, beyond simply imagining what it is like to be that person. Since a narrative creation exercise was absent from our MPT intervention, the act of writing may explain the stronger effects observed in these earlier studies, since it may engage deeper processing than simply reflecting on a topic.

The literature on illusions of embodiment reports that EPT and MPT are on par at deciphering emotions of other people (i.e., on an “empathic listening” task; Oh et al., 2016). However, one study found that EPT led to higher target-specific empathy than a control group (van Loon et al., 2018) and another that EPT led to higher empathic concern and personal distress (Herrera et al., 2018), a finding we conceptually replicate. Also relevant to these findings, one study showed that imagining how you would feel in a given situation (“imagine-self”)—and not just imagining how another would feel (“imagine-other”)—led to higher ratings of personal distress (Batson, Early, & Salvarani, 1997). Our EPT intervention probably led to increases in personal distress as well because perceptually embodying the body of the other person from a first-person point of view resembles more closely imagining yourself (it appears, after all, as your visual perspective) than imagining another (which may be more conceptual). Of note, our exploratory analyses also showed that participants who first experienced greater embodiment with the confederate also scored higher on personal distress (Supplemental Figure S1 in section S6). Finally, though speculative, we suspect that the observed effect on peripheral responsivity (a subcomponent of affective empathy associated with reacting to novel or movie characters) may be due to a phenomenological feature of the EPT group, wherein the similarity to watching a three-dimensional (3D)-movie may have been experienced as a detached social context.

Self–other overlap

In this study, both perspective-taking groups showed considerably more self–other merging with the confederate than the control group—that is, they felt closer to the confederate. Furthermore, those from the EPT group also showed more self–other merging than the MPT group. These results replicate past studies looking at self–other merging using perspective-taking (Davis et al., 1996; Galinsky et al., 2005; Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Todd et al., 2012) or illusions of embodiment (Herrera et al., 2018; Oh et al., 2016; Paladino et al., 2010). However, researchers find mixed results regarding the benefit of EPT over MPT on self–other overlap, with some finding differences and others not (Ahn et al., 2013; Herrera et al., 2018; Oh et al., 2016). 10 One recent study found that EPT led to increased self–other merging compared with a control group but not compared with MPT (Herrera et al., 2018), though their EPT self–other merging scores were considerably lower than in the current study (by about a full scale point). Our higher self–other merging scores might be an indication that methodologies that employ more realistic features, such as the body-swap paradigm, can induce more self–other overlap.

In exploratory analyses, we also found that people who experienced greater self–other overlap with the confederate also scored higher on personal distress (Supplemental Figure S2 in section S6). A follow-up analysis showed that self–other merging and embodiment specifically correlated with personal distress items relating to feeling helpless or losing control in emotional/emergency situations. Perhaps experiencing higher self–other overlap with the confederate led participants to see themselves as more personally distressed (or that their current emotional state influenced their responses), especially since the groups also differed on this measure. Indeed, researchers have found self–other overlap to mediate the relationship between perspective-taking and changes in self-concept (Galinsky et al., 2008; Goldstein & Cialdini, 2007; Laurent & Myers, 2011). However, the correlational nature of this analysis prevents us from excluding the possibility that more personally distressed people were predisposed to experience greater self–other overlap.

Implicit attitudes

Although we expected our perspective-taking interventions to reduce implicit race bias, this effect was absent (cf. Forscher et al., 2019, for a discussion relevant to statistical power and Type II errors regarding the small effect sizes usually found for changing implicit attitudes). This finding contrasts with previous research showing perspective-taking reduces implicit bias (Todd & Burgmer, 2013; Todd et al., 2011). Again, this result may be explainable by the lack of a narrative essay in the current study. However, our findings also align with other failed replication studies that used perspective-taking (Lai et al., 2014). Our findings also differ from studies based on illusions of embodiment—specifically those that changed implicit bias via the illusory embodiment of a black rubber hand (Farmer et al., 2012, 2014; Maister, Sebanz, et al., 2013) or of a full virtual body (Banakou et al., 2013; Groom et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2016; Peck et al., 2013). However, unlike us, most of these studies employed a within-subjects design by examining IAT scores before and after the embodiment intervention. Those studies that used a between-subject design, like we did, fail to find that EPT reduced implicit race bias compared with their control group (Groom et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2016).

As mentioned earlier, in this study, surprisingly, the average implicit race bias against African-Americans, computed as the D-score (Greenwald et al., 2003), approached zero for all our three groups (higher D-scores indicate more race bias), and likely represents the primary reason why we didn’t find implicit race bias differences across our groups. Such low D-scores contrast markedly with the scores reported in other studies, closer to .50 (see Supplemental Table S4 in section S9). Even the implicit race bias of our control group approximated zero (Supplemental Figure S3 in section S9), although their self–other merging scores were relatively low (normally associated with greater reductions in implicit bias), which could suggest, as mentioned earlier, a practical floor effect.

Several factors could explain such low and homogeneous IAT scores. The current study relied on the FreeIAT (Meade, 2009), which uses five blocks instead of seven, and the lack of counterbalancing may lead to smaller effects (Greenwald et al., 1998). Here, the first association block was incongruent (African Americans + positive words) while the last one was congruent (African Americans + negative words), which might lead to slightly less biased scores because learning from the first block interferes with performance in the second block (Greenwald et al., 2003). However, we used 50 trials per block, and as few as 40 trials per block largely eliminates this kind of order effect (Nosek et al., 2005). Furthermore, other studies have successfully used the FreeIAT as a significant predictor or intervention outcome (e.g., French et al., 2013; Hartman & Newmark, 2012). Our IAT also used “African American” and “European American” labels, instead of “Black” and “White,” which might have been a less sensitive measure for Canadian participants. Perhaps our Canadian participants had lower IAT scores because they had weaker associations with these American terms.

We also need to consider whether our original sample was biased or unbiased from the start (e.g., Axt, 2017; Kang et al., 2014 for studies finding samples without pro-Black bias at baseline). For example, we conducted the study within a multicultural environment, in which participants likely regularly interact with people of diverse origins. Indeed, researchers showed that embodying a black rubber hand only reduces implicit race bias for those who have high race biases to begin with (Farmer et al., 2014). To reduce suspicion, however, we did not administer baseline measures of implicit bias. Thus, to verify whether our population had low initial bias, we collected data from 10 additional participants from the same population; they completed the IAT and other measures without any experimental intervention. This new sample showed an average D-score of 0.30, a more reasonably expected level of bias.

To compare this average with more established reference scores, we looked at the Project Implicit online database (Xu et al., 2014, 2019); for year 2018, the average D-score for Canadian participants was 0.32 (based on 4,163 responses)—quite similar to the American average (0.28 based on 251,520 responses). Furthermore, we computed the average bias scores based on postal code data from 2004 to 2019; the city and province of the data collection hardly differ from the average country bias (Montréal: 0.32, Québec: 0.34, Canada: 0.34). These put the D-score of our new small sample in line with the normative data, suggesting that the floor effect comes, perhaps, from a common factor among our three conditions rather than to the non-presence of bias from the start. For instance, consistent with the intergroup contact hypothesis (Lemmer & Wagner, 2015), simply being face-to-face with a Black confederate in a shared social context (i.e., participating in a study), might have been sufficient to temporarily counter any existing bias (Dovidio et al., 2017; Shook & Fazio, 2008; Turner & Crisp, 2010). However, it seems unlikely that this minimal intergroup contact alone could have completely removed their racial bias. Thus, we can only speculate as to these unexpected results.

Explicit attitudes

Our interventions scarcely affected explicit race attitudes, unlike several previous studies on perspective-taking (Batson et al., 2002; Batson, Polycarpou, et al., 1997; Dovidio et al., 2004; Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Shih et al., 2009; Todd et al., 2011; Vescio et al., 2003). On one hand, these perspective-taking interventions either involved writing narrative essays (Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Todd et al., 2011), or witnessing the misery and suffering of these individuals (Batson et al., 2002; Batson, Polycarpou, et al., 1997) or an injustice perpetrated against the outgroup (e.g., Dovidio et al., 2004; Todd et al., 2011; Vescio et al., 2003). These interventions could thus lead to different or stronger effects since they can also prime values of justice (Finlay & Stephan, 2000), without necessarily isolating the perspective-taking component per se. On the other hand, these self-report measures may be particularly susceptible to demand characteristics, especially because some of these scales were measuring blatant, rather than subtle, prejudice (e.g., Brigham, 1993). Of course, because our questionnaire clearly assessed attitudes towards Black people, there may be an aspect of social desirability across conditions in our study as well, especially since participants were in the presence of another “participant” who was Black.

Although earlier studies did find changes in explicit attitudes following perspective-taking, more recent studies have mostly failed to replicate these findings. Many of them have in fact shown no effect from either EPT or MPT on explicit attitudes (Ahn et al., 2013; Groom et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2016; Peck et al., 2013). Out of three explicit measures of ageism, one study only found an effect of EPT on a word association task (Yee & Bailenson, 2006). Another study found that from the three “engaging with others’ perspectives” strategies mentioned earlier, none reduced explicit race bias (Lai et al., 2014). Furthermore, of the eight interventions that successfully changed implicit race bias in the first study, none changed explicit race bias in a subsequent replication study (Lai et al., 2016), suggesting that explicit attitudes may be robust to lasting change, at least following these types of short-term interventions. Thus, it appears that interventions designed to reduce explicit prejudice produce a mixed bag of outcomes, with many of these findings consistent with ours.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the low IAT scores left little room for further improvement from our interventions and so did not allow us to answer our questions regarding racial bias. Second, although our exploratory tests revealed ethnic origin seemed unrelated to implicit race bias scores, our sample composition was rather heterogeneous: only 50% of participants were White (in this regard, this caveat serves as an observation more than a limitation). Ethnicities were also distributed approximately equally in the three groups (Supplemental Table S5 in section S9). Third, on average participants reported having only 60% successfully engaged in their respective instructions, in relation to the maximum scores of the intervention check scales. Fourth, many participants had trouble following the movements of the confederate precisely and synchronously through the head-mounted display in the EPT condition; at times even some of the confederates found it challenging to coordinate perfectly with participants. This coordination difficulty might have limited the strength of the illusory embodiment. Indeed, no participant from the EPT condition reported the maximum embodiment score of seven, and only three reported the second maximum score of six. Perhaps using a regular virtual environment with a virtual avatar and motion detectors would provide more accurate tracking and visuo-proprioceptive feedback. Fifth, the crucial part of the intervention lasted only a minute for all three conditions; a lengthier intervention would have probably provided stronger results. Sixth, using a state empathy measure instead of dispositional ones might have provided a better picture of short-term emotional changes. Thus, readers should interpret these findings with caution given that the scales framed questions as how people are “in general,” instead of how they felt immediately following the procedure. Indeed, although unlikely, it is possible that participants dispositionally higher in empathy happened to be assigned to the EPT group due to chance alone. Future research could verify our results using picture- or video-based state empathy measures (e.g., Dziobek et al., 2008; Kuypers, 2017; Lindeman et al., 2018). Seventh, there was considerable interindividual variation, so a pre–post within-subject design (repeated measures) might have been more informative regarding the effects of the intervention, though it would have likely considerably increased demand characteristics. Eighth, we only relied on self-report measures (except for the IAT), which might have been subject to demand characteristics as well, so additional, behavioural measures would be appropriate for future research. Finally, our current statistical power, although in line with our preregistration, did not allow for the detection of small and medium effects. Furthermore, our large number of statistical tests may have resulted in inflated Type 1 errors. Our results should therefore be replicated in future confirmatory research now that this initial exploratory study has identified some potential hypotheses of interest. Despite these limitations, our empathy findings are encouraging to improve intergroup relations given the association between empathy, prejudice, and prosocial benefits (Batson & Ahmad, 2009; Eisenberg & Miller, 1987; Finlay & Stephan, 2000; Hoffman, 2008; Krebs, 1975; Rumble et al., 2010; Zaki, 2018).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that perspective-taking interventions, based on imagination or illusions of embodiment of an outgroup member, unreliably affect conscious and automatic race bias. At the same time, perspective-taking interventions based on the illusory embodiment of an outgroup member can increase some components of empathy (empathic concern, personal distress, and peripheral responsivity) and make one feel considerably closer to a specific outgroup member. Future research should investigate whether lengthier interventions and using more racially biased populations of study can lead to stronger effects on explicit and implicit prejudice. Despite its limitations, the current EPT intervention based on virtual reality shows the potential to improve intergroup relations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-qjp-10.1177_17470218211024826 for Body swapping with a Black person boosts empathy: Using virtual reality to embody another by Rémi Thériault, Jay A Olson, Sonia A Krol and Amir Raz in Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amanda Dennie, Lauriol Djehounke, Emily Light, and Camille Welcome Chamberlain for their help with data collection and elsewhere, Amanda Dennie and Daphné Bertrand-Dubois for help with the photo, and Jordan Axt, Jason Da Silva Castanheira, Mariève Cyr, Amanda Dennie, Emily Light, and Lauriol Djehounke for providing feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript. Finally, the authors thank the whole BeAnotherLab team, who graciously accepted to share their Machine to be Another system with researchers.

A total of 75 participants (before exclusions) had already completed the study at the time of the pre-registration. However, none of these responses were analysed and we did not attempt to discern patterns in the data or compute summary statistics.

We inadvertently omitted this exclusion criterion from our pre-registration. We provide full results with these five individuals included on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/gb2kr/.

We provide the final data set on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/gb2kr/.

For example, we used a cover story (claiming an interest in “the effect of virtual reality on social cognition”) while simultaneously letting participants “fill in the blanks” on the details. Confederates engaged in “costly behaviour” (e.g., waiting outside the lab space for up to 15 min prior to the start of the study, seemingly engaging in all parts of the study, including answering questionnaires). The experimenter also wore an official university lab coat and employed fake materials (e.g., for the photography) to increase credibility and lower suspicion.

All individuals whose image appears throughout this paper have given their permission in writing.

Publicly available at https://github.com/BeAnotherLab/The-Machine-to-be-Another.

Available at https://meade.wordpress.ncsu.edu/freeiat-home/.

Square brackets denote bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals throughout the manuscript.

We originally intended to test whether self–other overlap mediated any effects of empathy or prejudice. However, the results suggest that our analysis is underpowered: the mediation revealed a total effect of Group on the Empathic Concern and Personal Distress subscales of the IRI, but we were unable to further decompose the effects in direct and indirect effects (see section S8 for complete results).

Ahn et al.’s (2013, study 2) numbers were quite similar to ours: the average self–other merging scores were, respectively, 3.98 and 4.00 for the EPT group, and 2.39 and 3.07 for the MPT group.

Footnotes

Author contributions: R.T. designed the study, collected the data, performed the statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. J.A.O. contributed to the study design, general guidance with the project, and statistical analysis. S.A.K. helped with the study design and general guidance with the project. A.R. helped with the overall guidance and advice for the project. All the authors contributed to the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Canada Research Chair program, Discovery and Discovery Acceleration Supplement grants from NSERC (386156-2010), and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-106454) to A.R.; R.T. and J.A.O. were both supported by Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarships from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and S.A.K. was supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. These sources of financial support had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

ORCID iD: Rémi Thériault  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4315-6788

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4315-6788

Data accessibility statement:

The data and materials from the present experiment are publicly available at the Open Science Framework website: https://osf.io/gb2kr/.

Supplementary material: The supplementary material is available at qjep.sagepub.com.

References

- Ahlmann-Eltze C. (2019). ggsignif: Significance brackets for “ggplot2.” https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggsignif Version = 0.6.0

- Ahn S. J., Le A. M. T., Bailenson J. (2013). The effect of embodied experiences on self-other merging, attitude, and helping behavior. Media Psychology, 16(1), 7–38. 10.1080/15213269.2012.755877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Algina J., Keselman H. J., Penfield R. D. (2005). An alternative to Cohen’s standardized mean difference effect size: A robust parameter and confidence interval in the two independent groups case. Psychological Methods, 10(3), 317–328. 10.1037/1082-989X.10.3.317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althouse A. D. (2016). Adjust for multiple comparisons? It’s not that simple. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 101(5), 1644–1645. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodio D. M. (2014). The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(10), 670–682. 10.1038/nrn3800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A., Aron E. N., Smollan D. (1992). Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. 10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Axt J. R. (2017). An unintentional pro-Black bias in judgement among educators. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(3), 408–421. 10.1111/bjep.12156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldner C., McGinley J. (2014). Correlational and exploratory factor analyses (EFA) of commonly used empathy questionnaires: New insights. Motivation and Emotion, 38(5), 727–744. 10.1007/s11031-014-9417-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banakou D., Groten R., Slater M. (2013). Illusory ownership of a virtual child body causes overestimation of object sizes and implicit attitude changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(31), 12846–12851. 10.1073/pnas.1306779110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banakou D., Hanumanthu P. D., Slater M. (2016). Virtual embodiment of White people in a Black virtual body leads to a sustained reduction in their implicit racial bias. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 601. 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson C. D., Ahmad N. Y. (2009). Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 3(1), 141–177. 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01013.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batson C. D., Chang J., Orr R., Rowland J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1656–1666. 10.1177/014616702237647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batson C. D., Early S., Salvarani G. (1997). Perspective taking: Imagining how another feels versus imagining how you would feel. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(7), 751–758. 10.1177/0146167297237008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batson C. D., Polycarpou M. P., Harmon-Jones E., Imhoff H. J., Mitchener E. C., Bednar L. L., Klein T. R., Highberger L. (1997). Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 105. 10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand P., Gonzalez-Franco D., Cherene C., Pointeau A. (2014). ‘The Machine to Be Another’: Embodiment performance to promote empathy among individuals. https://doc.gold.ac.uk/aisb50/AISB50-S16/AISB50-S16-Bertrand-paper.pdf

- Bertrand P., Guegan J., Robieux L., McCall C. A., Zenasni F. (2018). Learning empathy through virtual reality: Multiple strategies for training empathy-related abilities using body ownership illusions in embodied virtual reality. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 5, 26. 10.3389/frobt.2018.00026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M., Cohen J. (1998). Rubber hands “feel” touch that eyes see. Nature, 391(6669), 756–756. 10.1038/35784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigham J. C. (1993). College students’ racial attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23(23), 1933–1967. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01074.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. D., Trapnell P. D., Heine S. J., Katz I. M., Lavallee L. F., Lehman D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(1), 141. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Consequences of prejudice. (2007). In Hanes R. C., Hanes S. M., Rudd K., Hermsen S. (Eds.), Prejudice in the modern world reference library. https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/consequences-prejudice

- Crabb W. T., Moracco J. C., Bender R. C. (1983). A comparative study of empathy training with programmed instruction for lay helpers. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(2), 221. 10.1037/0022-0167.30.2.221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N. (2013). Implicit attitudes and beliefs adapt to situations: A decade of research on the malleability of implicit prejudice, stereotypes, and the self-concept. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 233–279. 10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00005-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. H., Conklin L., Smith A., Luce C. (1996). Effect of perspective taking on the cognitive representation of persons: A merging of self and other. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 713. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira E. C., Bertrand P., Lesur M. E. R., Palomo P., Demarzo M., Cebolla A., Baños R., Tori R. (2016). Virtual body swap: A new feasible tool to be explored in health and education. In 2016 XVIII Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality (SVR), Gramado, Brazil. 10.1109/SVR.2016.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desai P. R., Desai P. N., Ajmera K. D., Mehta K. (2014). A review paper on Oculus Rift: A virtual reality headset. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technol-ogy, 13(4), 175–179. 10.14445/22315381/IJETT-V13P237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio J. F., Love A., Schellhaas F. M. H., Hewstone M. (2017). Reducing intergroup bias through intergroup contact: Twenty years of progress and future directions. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(5), 606–620. 10.1177/1368430217712052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio J. F., Ten Vergert M., Stewart T. L., Gaertner S. L., Johnson J. D., Esses V. M., Riek B. M., Pearson A. R. (2004). Perspective and prejudice: Antecedents and mediating mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(12), 1537–1549. 10.1177/0146167204271177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziobek I., Rogers K., Fleck S., Bahnemann M., Heekeren H. R., Wolf O. T., Convit A. (2008). Dissociation of cognitive and emotional empathy in adults with Asperger syndrome using the Multifaceted Empathy Test (MET). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(3), 464–473. 10.1007/s10803-007-0486-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., Miller P. A. (1987). The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 91–119. 10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erera P. I. (1997). Empathy training for helping professionals: Model and evaluation. Journal of Social Work Education, 33(2), 245–260. 10.1080/10437797.1997.10778868 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esses V. M., Hamilton L. K., Gaucher D. (2017). The global refugee crisis: Empirical evidence and policy implications for improving public attitudes and facilitating refugee resettlement. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 78–123. 10.1111/sipr.12028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer H., Maister L. (2017). Putting ourselves in another’s skin: Using the plasticity of self-perception to enhance empathy and decrease prejudice. Social Justice Research, 30(4), 323–354. 10.1007/s11211-017-0294-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer H., Maister L., Tsakiris M. (2014). Change my body, change my mind: The effects of illusory ownership of an outgroup hand on implicit attitudes toward that outgroup. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(10), 1016. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.01016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer H., Tajadura-Jimenez A., Tsakiris M. (2012). Beyond the colour of my skin: How skin colour affects the sense of body-ownership. Consciousness and Cognition, 21(3), 1242–1256. https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.concog.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feise R. J. (2002). Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2, Article 8. 10.1186/1471-2288-2-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fini C., Cardini F., Tajadura-Jiménez A., Serino A., Tsakiris M. (2013). Embodying an outgroup: The role of racial bias and the effect of multisensory processing in somatosensory remapping. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 165. 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay K. A., Stephan W. G. (2000). Improving intergroup relations: The effects of empathy on racial attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(8), 1720–1737. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02464.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forscher P. S., Lai C. K., Axt J. R., Ebersole C. R., Herman M., Devine P. G., Nosek B. A. (2019). A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(3), 522–559. 10.1037/pspa0000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French A. R., Franz T. M., Phelan L. L., Blaine B. E. (2013). Reducing Muslim/Arab stereotypes through evaluative conditioning. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153(1), 6–9. 10.1080/00224545.2012.706242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky A. D., Ku G. (2004). The effects of perspective-taking on prejudice: The moderating role of self-evaluation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(5), 594–604. 10.1177/0146167203262802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky A. D., Ku G., Wang C. S. (2005). Perspective-taking and self-other overlap: Fostering social bonds and facilitating social coordination. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 8(2), 109–124. 10.1177/1368430205051060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky A. D., Moskowitz G. B. (2000). Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 708. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky A. D., Wang C. S., Ku G. (2008). Perspective-takers behave more stereotypically. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(2), 404–419. 10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski B., Bodenhausen G. V. (2006). Associative and propositional processes in evaluation: An integrative review of implicit and explicit attitude change. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 692. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlbach H., Brinkworth M. E., Wang M.-T. (2012). The social perspective taking process: What motivates individuals to take another’s perspective? Teachers College Record, 114(1), 197–225. https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-193:HUL.InstRepos:11393841 [Google Scholar]

- Gehlbach H., Marietta G., King A. M., Karutz C., Bailenson J. N., Dede C. (2015). Many ways to walk a mile in another’s moccasins: Type of social perspective taking and its effect on negotiation outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 523–532. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein N. J., Cialdini R. B. (2007). The spyglass self: A model of vicarious self-perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 402–417. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald A. G., McGhee D. E., Schwartz J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald A. G., Nosek B. A., Banaji M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald A. G., Poehlman T. A., Uhlmann E. L., Banaji M. R. (2009). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 17–41. 10.1037/a0015575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groom V., Bailenson J. N., Nass C. (2009). The influence of racial embodiment on racial bias in immersive virtual environments. Social Influence, 4(3), 231–248. 10.1080/15534510802643750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman T. K., Newmark A. J. (2012). Motivated reasoning, political sophistication, and associations between president Obama and Islam. PS: Political Science & Politics, 45(3), 449–455. 10.1017/S1049096512000327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler B. S., Spanlang B., Slater M. (2017). Virtual race transformation reverses racial in-group bias. PLOS ONE, 12(4), Article e0174965. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry P. J., Sears D. O. (2002). The Symbolic Racism 2000 Scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253–283. 10.1111/0162-895X.00281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera F., Bailenson J., Weisz E., Ogle E., Zaki J. (2018). Building long-term empathy: A large-scale comparison of traditional and virtual reality perspective-taking. PLOS ONE, 13(10), Article e0204494. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges S. D., Klein K. J. (2001). Regulating the costs of empathy: The price of being human. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 30(5), 437–452. 10.1016/S1053-5357(01)00112-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M. L. (2008). Empathy and prosocial behavior. In Lewis M., Haviland-Jones J. M., Barrett L. F. (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 440–455). Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-07784-027 [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W., Gawronski B., Gschwendner T., Le H., Schmitt M. (2005). A meta-analysis on the correlation between the Implicit Association Test and explicit self-report measures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1369–1385. 10.1177/0146167205275613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Gray J. R., Dovidio J. F. (2014). The nondiscriminating heart: Lovingkindness meditation training decreases implicit intergroup bias. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(3), 1306–1313. 10.1037/a0034150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara A. (2019). ggpubr: “ggplot2” based publication ready plots. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr Version = 0.2.2

- Kilteni K., Maselli A., Kording K. P., Slater M. (2015). Over my fake body: Body ownership illusions for studying the multisensory basis of own-body perception. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9(20), 141. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby K. N., Gerlanc D. (2013). BootES: An R package for bootstrap confidence intervals on effect sizes. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 905–927. 10.3758/s13428-013-0330-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs D. (1975). Empathy and altruism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(6), 1134–1146. 10.1037/0022-3514.32.6.1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol S. A., Thériault R., Olson J. A., Raz A., Bartz J. A. (2019). Self-concept clarity and the bodily self: Malleability across modalities. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46, 808–820. 10.1177/0146167219879126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]