Abstract

A new immunoblot assay, composed of four Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded recombinant proteins (virus capsid antigen [VCA] p23, early antigen [EA] p138, EA p54, and EBNA-1 p72), was compared with an immunofluorescence assay on a total of 291 sera. The test was accurate in 94.5% of cases of primary EBV infection, while an immunoglobulin G anti-VCA p23 band with strong intensity correlated with reactivation.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has a worldwide distribution, with over 90% of the adult population showing evidence of past infection. The virus, acquired during childhood, usually causes no symptoms. However, in Western societies, 10 to 20% of adolescents and young adults develop acute infectious mononucleosis (IM). In humans, EBV is also associated with cancer, in particular Burkitt’s lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Hodgkin’s disease, and immunoblastic lymphoma (12). To diagnose heterophile-negative IM cases (20 to 30%) (3) and other EBV-associated diseases, a determination of EBV-specific antibodies is necessary. The seroepidemiology of EBV infection and EBV-associated diseases has predominantly relied upon immunofluorescence (IF). This method uses fixed cells derived from various immortalized lymphoid cell lines (5, 10). Serological parameters include the detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and occasionally IgA, directed against EBV latent nuclear antigens (EBNAs) (9); early antigens (EAs), divisible into EA-D and EA-R components (6); and virus capsid antigens (VCAs). The typical antibody pattern of primary EBV infection is characterized by the presence of both IgM and IgG antibodies to VCA and EA and by the absence of IgG antibodies to EBNA. Anti-VCA IgM antibodies disappear during convalescence, and thus their presence is diagnostic of acute EBV infection, whereas anti-VCA IgG antibodies are maintained for life after recovery. The IgG response to EBNA (mainly EBNA-1) is not usually detectable until convalescence and then persists for life. Anti-EA IgG antibodies (most frequently anti-EA-D) are detected by IF in about 70% of patients with acute IM and disappear after recovery. During EBV reactivation, anti-EA IgG can reappear, frequently with a rise in anti-VCA IgG and sometimes in the presence of anti-VCA IgM.

For the serodiagnosis of EBV infection, the IF assay, often considered the “gold standard,” is still commonly used. However, IF is time-consuming and unsuitable for examining large numbers of samples. Commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test kits for the detection of EBV-specific antibodies have been available since the end of the 1980s. Recently, recombinant EBV antigens have been incorporated into ELISA kits to improve the specificity of antibody detection. However, recent studies have shown that there are differences in the quality of current ELISA test kits, with only a few being suitable for routine diagnosis (19, 20). Test results sometimes conflict from one evaluation to another, and the use of a combination of markers from different manufacturers may be necessary (15).

In this study, we compared the performance of the new EBV IgM/IgG Blot 3.0 assay (Genelabs Diagnostics, Singapore, Republic of Singapore) with an in-house IF assay on a total of 291 sera, assigned to one of seven panels depending on their serological status, previously established by IF (Table 1). Characteristics of the panels are described in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Antibody titers corresponding to EBV status (by IF)a

| EBV serostatus | Titer of antibody

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCA IgG | VCA IgM | EA IgG | EBNA IgG | |

| Seronegative | <5 | <10 | <5 | <5 |

| Past infection | 20–640 | <10 | ≤10 | 20–320 |

| Primary infection | 20–1,280 | >10 | <5–160 | <5–10 |

| Reactivation | 1,280–5,120 | <10 | <5–≥80 | 20–320 |

Titers correspond to the last dilution showing any fluorescence.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of serum panels

| Panel | Serological status | No. of samples | GMT (range) or resulta

|

Source or characteristic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCA IgG | VCA IgM | EA IgG | EBNA IgG | ||||

| A | Seronegative | 78 | − | − | − | − | Mainly children |

| B | Past infection | 26 | 173.3 (80–640) | − | ND | 68.2 (20–320) | |

| C | Reactivationb | 14 | 2,195.0 (1,280–5,120) | − | 205.9 (<5–640) | 67.3 (<5–160) | Immunosuppressed patients or patients with an EBV-associated tumor |

| D | Primary infection | 37 | 195.0 (<5–1,280) | + | ND | 6.3 (<5–10) | Heterophile antibodies (19 samples) |

| E | IgM cross-reactivityc | 21 | 271.8 (<5–5,120) | ND | ND | 28.3 (<5–80) | |

| F | Routine diagnosis | 47 | 324.9 (<5–5,120) | ND | ND | 36.7 (<5–320) | |

| G | Past infection without EBNA | 34 | 277.4 (80–1,280) | ND | ND | − | Healthy adults |

GMT, geometric mean titer; ND, not done; +, positive result; −, negative result. For VCA IgM antibodies, a single dilution was performed; a titer for the positive value was not quantifiable.

Serial samples (n = 34) from five organ transplant recipients were added to this panel.

Two hepatitis A virus samples, one hepatitis B virus sample, six cytomegalovirus samples, six herpes simplex virus samples, two varicella-zoster virus samples, two mumps virus samples, and two measles virus samples.

EBV IgM/IgG immunoblot.

The EBV IgM/IgG Blot 3.0 assay allowed the determination of IgG and IgM antibodies directed against specific EBV-encoded recombinant antigens. The following antigens were incorporated onto nitrocellulose strips: VCA p23 (BLRF2), EA-D p54 (BMRF1), EA p138 (BALF2), and EBNA-1 p72 (BKRF1). As a check for serum addition and procedural accuracy, anti-human IgG and IgM controls were included on the strips. After the incubation of individual nitrocellulose strips with diluted sera (1:100), antibodies that bound specifically to EBV proteins were visualized with goat anti-human IgG or IgM conjugated with alkaline phosphatase and a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoylphosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) substrate. Rheumatoid-factor absorbent was used in the IgM test.

To interpret the results, serum addition control bands (anti-IgG and anti-IgM) must be present in the IgG-assayed strips, and the IgM control band must be present in the IgM-assayed strips. A result was said to be negative if no reactivity to the EBV-specific antigen bands was found or if the intensity of any EBV-specific band was weaker than that of the serum control band (anti-IgG). A result was said to be positive if the antigen band was visible and if its intensity was equal to or greater than that of the serum control band (anti-IgG). This immunoblot assay can be processed automatically, and interpretation of results and data management can be fully computerized. A visual determination of band intensity was performed first and then verified with AutoScan software (version 2.0), giving an objective interpretation of results.

IF assay.

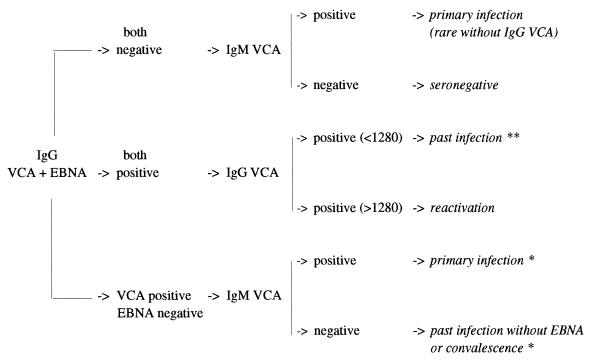

Indirect and anticomplement IF assays were carried out with in-house slides for the detection of anti-VCA IgG anti-EA IgG and EBNA antibodies, respectively. EBV-specific antibodies were determined on the basis of slides, fixed in cold acetone, and prepared from antigen-producing P3HR1 (VCA) and chemically induced Raji (EA-R and EA-D) cells (7). Antibodies against EBNA were detected by anticomplement IF assay in nonproducing Raji cells fixed in a mixture of cold acetone and methanol (10). The detection of anti-VCA IgM was performed with a commercial test kit (Gull Laboratories, Salt Lake City, Utah) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the detection of anti-VCA IgG, anti-EA IgG, and anti-EBNA antibodies, sera were diluted fourfold, from 1:5 to 1:5,120. The concentration of antibodies was expressed as a titer, with the endpoint corresponding to the last dilution showing any fluorescence. Sera with titers greater than or equal to 1:5 were considered positive. In the case of VCA IgM, a single dilution was performed (1:10), which was considered the cutoff value for positivity. An algorithm of interpretation is given in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

EBV IF interpretation algorithm established from routine laboratory experience. ∗, if the VCA IgG titer is ≥1,280, there is possible reactivation or chronic infection; ∗∗, if the EA IgG titer is ≥80, there is possible reactivation.

In the primary infection panel, heterophile antibodies were detected with a Monospot test (Meridian Diagnostics, Cincinnati, Ohio), following manufacturer’s recommendations.

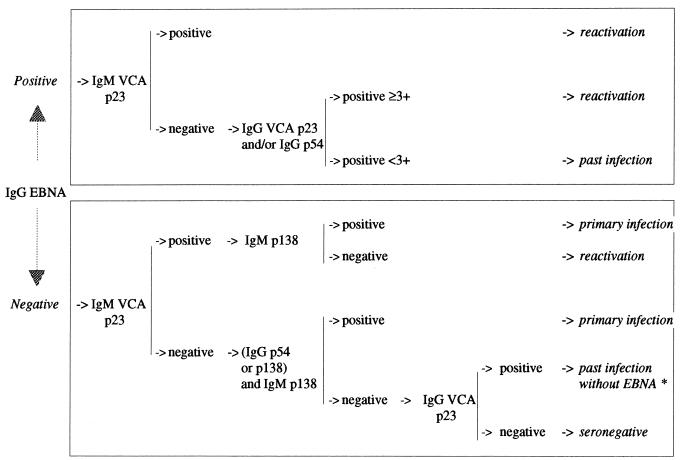

The analysis of each antibody response (Table 3) allowed us to define an interpretation algorithm for the establishment of EBV serological status (Fig. 2). Sensitivity and specificity results are shown in Table 4.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of the four markers (p23, p54, p138, and p72) in various EBV serological groups determined with the EBV IgM/IgG Blot 3.0 kit and IF assaya

| Panel (n) and intensity | % IgG reaction to antigen

|

% IgM reaction to antigen

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCA

|

EA

|

EBNA

|

VCA

|

EA

|

|||||||

| p23 | IF | p54 | p138 | IF | p72 | IF | p23 | IF | p54 | p138 | |

| A (78) | |||||||||||

| Normal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NT | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 6.4 | 30.7 |

| ≥3+ | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| B (26) | |||||||||||

| Normal | 100 | 100 | 30.7 | 23.0 | 29.6 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 7.6 | 26.9 |

| ≥3+ | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| C (14) | |||||||||||

| Normal | 100 | 100 | 64.2 | 64.2 | 78.5 | 78.5 | 85.7 | 64.2 | 0 | 35.7 | 0 |

| ≥3+ | 85.7 | 35.7 | |||||||||

| D (37) | |||||||||||

| Normal | 51.4 | 94.5 | 78.3 | 72.9 | NT | 0 | 2.7 | 75.6 | 100 | 72.9 | 100 |

| ≥3+ | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| E (21) | |||||||||||

| Normal | 80.9 | 80.9 | 4.7 | 9.5 | NT | 66.6 | 66.6 | 9.5 | 4.7 | 23.8 | 33.3 |

| ≥3+ | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| F (47) | |||||||||||

| Normal | 97.8 | 97.8 | 31.9 | 25.5 | NT | 80.8 | 87.2 | 21.7 | ≤2.1 | 6.5 | 13.0 |

| ≥3+ | |||||||||||

| G (34) | |||||||||||

| Normal | 100 | 97 | 44.1 | 11.7 | NT | 20.5 | 2.9 | 29.4 | 0 | 17.6 | 17.6 |

| ≥3+ | 41.1 | 2.9 | 0 | ||||||||

In this study, we never detected anti-EBNA IgM, irrespective of panel. NT, not tested.

FIG. 2.

EBV blot interpretation algorithm established by this study. ∗, if the VCA p23 IgG titer is ≥3+, there is possible reactivation without EBNA. If there is a band intensity of 3+ or less, refer to IgM control band intensity of IgM assay.

TABLE 4.

Results of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values according to the different panelsa

| Panel | Serological status | EBNA p72 IgG

|

VCA p23 IgG

|

VCA p23 IgM

|

Concordance of interpretation (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |||

| A | Seronegative | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.4 | 100 | 97.4 | ||||||

| B | Past infection | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| C | Reactivation | 91.6 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 35.7 | 100 | 85.7 | ||||||

| D | Primary infection | 100 | 97.2 | 51.4 | 100 | 75.6 | 100 | 94.5 | ||||||

| E | Interference | 92.8 | 92.8 | 100 | 100 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 90.4 | ||||||

| F | Routine diagnosis | 90.2 | 97.3 | 100 | 100 | 80.4 | 100 | 89.3 | ||||||

| G | Past infection without EBNA | 81.8 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 70.5 | 100 | 61.8 | ||||||

| Total | 92.6 | 95 | 93.2 | 95.1 | 89.5 | 100 | 100 | 82.5 | 75 | 85.7 | 49.1 | 94.8 | ||

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

The overall immunoblot results with the classical serological markers (EBNA IgG, VCA IgG, and VCA IgM) were very good for IgG. The results obtained with the EBNA p72 antigen showed good specificity and sensitivity with the different panels. On the other hand, the overall sensitivity of VCA p23 IgG (89.5%) did not reflect the value obtained with each panel, as this marker was consistently excellent except with panel D, which indicated that anti-VCA p23 IgG was not among the earliest capsid antibodies elicited during primary EBV infection. EBV p23 is a viral late complex associated with virion particles (16) and consists of two gene products, BFRF3 (17) and BLRF2 (11, 13). Until now, the detection of anti-VCA antibodies in most serological ELISA tests has relied on the response to a 110- to 125-kDa protein, a major immunogen of VCA, encoded by BALF4 (8). Previous studies (11, 16, 17) showed that all healthy EBV carriers exhibited both BLRF2 and BFRF3 antibodies. We confirm these results, since IgG antibodies were detected in all past-infection sera (panel B). These antibodies can therefore be considered the major immunodominant markers of EBV seropositivity. However, little is known about the immunological response to the p23 protein during an acute primary infection. Although it was initially reported (11, 16) that sera from most IM patients contained detectable levels of IgG and IgM to p23 (either BFRF3 or BLRF2), further studies have suggested that antibodies to BFRF3 could be absent in the early stages of IM (14, 18). In our study, 49% of individuals lacked IgG BLRF2-specific antibodies, while only 5.5% lacked antibodies to whole VCA, as determined by IF. With the IgM class, reactivity against the VCA p23 component was found in 75.6% of subjects. Thus, consistent with previous data concerning BFRF3 antibodies, this evaluation highlighted a delay in the detection of BLRF2 antibodies in patients undergoing a primary infection, although IgM-specific antibodies were detected earlier than IgG antibodies (18). As previously described (2, 4, 9), the predominant response during IM is directed against early antigens p54 and p138. Indeed, anti-p138 IgM antibodies seem to characterize the primary infection, since they were present in 100% of acute cases while generally undetected during EBV reactivation. The difference in EA antibody detection observed between immunoblotting and IF during primary infection could be explained by the lack of p138 protein in the induced Raji cell line used.

From to the results obtained with the panels, a prevalence analysis of these four IgG and IgM antibodies allowed us to define an algorithm for interpretation. The serological profiles obtained with the immunoblot with this decision-making tree showed a very good correlation with the profiles obtained by IF. This blot test identifies almost all IF-seronegative subjects and all patients with a history of past infection and a normal positive serology. We observed very limited interference in the IgM test, unlike some ELISAs (1). In fact, we observed only a weak reactivity in a single sample that corresponded to a primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. Thus, it seems that the serological status of patients either not infected by EBV or presenting a past infection with anti-EBNA antibodies does not constitute a problem with the EBV IgM/IgG Blot 3.0 assay. For subjects with past EBV infections without anti-EBNA IgG, a state observed in certain immunosuppressed patients and elderly individuals, the prevalence of anti-p54 IgG and anti-p138 IgG was lower than in subjects with primary infections and reactivations. In contrast to subjects with primary infections, who all had anti-p138 antibodies, only 17.6% of the subjects with past infections showed IgM reactivity. Analysis of the different interpretations given by the algorithm showed a 38.2% difference between IF and the new assay, due mainly to reactivations not diagnosed by IF.

The immunoblot assay is accurate for the diagnosis of primary EBV infection in most cases. In this assay, the detection of antibodies to early antigens compensates for the delay observed in VCA p23 IgG-IgM detection during the early phase of infection. There was no correlation between the presence of heterophile antibodies and anti-p23 IgM antibodies. IF-diagnosed serological reactivations were well detected by immunoblotting with a very strong intensity (≥3+) of VCA p23 IgG and/or EA p54 IgG, which has not been observed during primary infection. A comparative study of the kinetics of antibodies in five organ transplant recipients (Table 5) revealed that, in three of the five recipients, serological reactivation may be characterized by different immunoblot profiles. In the other two, discrepancies between the IF and immunoblot methods were obtained. These discrepancies show that the serological results obtained in immunosuppressed patients must be interpreted with caution. In fact, serology is often not informative when latent EBV is reactivated, especially in conjunction with lymphoproliferative disorders. A diagnosis of EBV reactivation should be evaluated at the molecular level by the quantitative determination of viral load and correlated with clinical manifestations.

TABLE 5.

Serological follow-up of five transplant recipients

| Patient and age (yr) | Clinical status (mo/yr)a | Date of serum collection (day/mo/yr) | IF titer of antibody

|

Immunoblot titer of antibodyb

|

Interpretationsc

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG

|

IgM

|

||||||||||||||

| VCA IgG | VCA IgM | EBNA IgG | VCA p23 | EA

|

EBNA p72 | VCA p23 | EA

|

EBNA p72 | IF | Immunoblot | |||||

| p54 | p138 | p54 | p138 | ||||||||||||

| 1 (36) | Kidney transplant (03/92) | 16/4/92 | <5 | <10 | <5 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | SN | SN |

| 31/8/92 | 640 | ≥10 | <5 | − | + | + | − | − | ++ | + | − | PI | PI | ||

| 22/1/93 | 2,560 | 10 | <5 | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | R* | PI | ||

| 9/10/95 | 5,120 | <10 | <5 | ++ | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | R* | PI | ||

| 25/11/96 | 5,120 | <10 | <5 | ++ | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | R* | PI | ||

| 2 (61) | Heart transplant (01/91) | 6/7/94 | 5,120 | 10 | 40 | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | − | R | R |

| 17/3/95 | 5,120 | 10 | 20 | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | − | R | R | ||

| 11/10/95 | 5,120 | 10 | 40 | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | − | R | R | ||

| 23/10/96 | 5,120 | 10 | 40 | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | − | R | R | ||

| 3 (13) | Heart transplant (85) | 14/12/94 | 2,560 | <10 | 5 | +++ | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | R | R |

| 15/3/95 | 5,120 | <10 | 5 | +++ | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | R | R | ||

| 17/4/96 | 5,120 | <10 | 5 | +++ | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | R | R | ||

| 18/10/96 | 5,120 | <10 | 5 | +++ | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | R | R | ||

| 4 (29 mo) | Kidney and heart transplant (08/96) | 11/9/96 | <5 | <10 | <5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | SN | SN |

| 9/10/96 | <5 | <10 | <5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | SN | SN | ||

| 10/12/96 | 80 | 10 | <5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | PI | SN | ||

| 20/12/96 | 80 | 10 | <5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | PI | SN | ||

| 3/1/97 | 1,280 | 10 | <5 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | PI | PI | ||

| 17/1/97 | 1,280 | 10 | <5 | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | PI | PI | ||

| 4/2/97 | 1,280 | 10 | <5 | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | PI* | PI | ||

| 5 (49) | Kidney transplant (94) | 8/3/95 | ≥5,120 | <10 | 20 | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | − | − | − | R | R |

| 25/4/96 | ≥5,120 | <10 | 40 | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | − | − | − | R | R | ||

| 26/11/96 | ≥5,120 | <10 | 40 | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | − | − | − | R | R | ||

If month is unknown, year only is given in parentheses.

The number of plus (+) signs corresponds to band intensity.

SN, seronegative; PI, primary infection; R, reactivation; *, possible chronic infection. Boldface designations denote discrepancies between the IF and immunoblot interpretations.

Initially based on purified antigens, ELISAs developed by a number of companies now use recombinant proteins, but a minimum of three to five markers are required for their use. Furthermore, serological tests are generally not suitable for the diagnosis of reactivated infection, since there is rarely a good correlation between IF titers and ELISA absorbance or values (1). Our present evaluation shows that this novel immunoblot assay has diagnostic capabilities comparable to those of the IF assay and therefore provides a new alternative for the screening and diagnosis of EBV infection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Debyser Z, Reynders M, Goubau P, Desmyter J. Comparative evaluation of three ELISA techniques and an indirect immunofluorescence assay for the serological diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Clin Diagn Virol. 1997;8:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0197(97)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Färber I, Wutzler P, Wohlrabe P, Wolf H, Hinderer W, Sonneborn H-H. Serological diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis using three anti-Epstein-Barr virus recombinant ELISAs. J Virol Methods. 1993;42:301–308. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90041-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleisher G, Lennette E T, Henle G, Henle W. Incidence of heterophil antibody responses in children with infectious mononucleosis. J Pediatr. 1979;94:723–728. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorgievski-Hrisoho M, Hinderer W, Nebel-Schickel H, Horn J, Vornhagen R, Sonneborn H-H, Wolf H, Siegl G. Serodiagnosis of infectious mononucleosis by using recombinant Epstein-Barr virus antigens and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technology. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2305–2311. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.10.2305-2311.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henle G, Henle W. Immunofluorescence in cells derived from Burkitt’s lymphoma. J Bacteriol. 1966;91:1248–1256. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.3.1248-1256.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henle W, Henle G, Zajak B A, Pearson G, Waubke R, Scriba M. Differential reactivity of human serums with early antigens induced by Epstein-Barr virus. Science. 1970;169:188–190. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3941.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henle W, Henle G, Horwitz C A. Epstein-Barr virus specific diagnostic test in infectious mononuclosis. Hum Pathol. 1974;5:551–565. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(74)80006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luca J, Chase R C, Pearson G R. A sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) against the major EBV-associated antigens. 1. Correlation between ELISA and immunofluorescence titers against purified antigens. J Immunol Methods. 1984;67:145–156. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middeldorp J M, Herbrink P. Epstein-Barr virus specific marker molecules for early diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis. J Virol Methods. 1988;21:133–146. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(88)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reedman B M, Klein G. Cellular localisation of an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated complement-fixing antigen in producer and non-producer lymphoblastoid cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1973;11:599–620. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910110302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reischl U, Gerdes C, Motz M, Wolf H. Expression and purification of an Epstein-Barr virus encoded 23-kDa protein and characterization of its immunological properties. J Virol Methods. 1996;57:71–85. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)01970-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rickinson A B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 2397–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serio T R, Angeloni A, Kolman J L, Gradoville L, Sun R, Katz D A, van Grunsven W M J, Middeldorp J M, Miller G. Two 21-kilodalton components of the Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen complex and their relationship to ZEBRA-associated protein p21 (ZAP21) J Virol. 1996;70:8047–8054. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8047-8054.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shedd D, Angeloni A, Niederman J, Miller G. Detection of human serum antibodies to the BFRF3 Epstein-Barr virus capsid component by means of a DNA-binding assay. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1367–1370. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svahn A, Magnusson M, Jägdahl L, Schloss L, Kahlmeter G, Linde A. Evaluation of three commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and two latex agglutination assays for diagnosis of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2728–2732. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2728-2732.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Grunsven W M J, Nabbe A, Middeldorp J M. Identification and molecular characterization of two diagnostically relevant marker proteins of the Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen complex. J Med Virol. 1993;40:161–169. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890400215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Grunsven W M J, Van Heerde E C, De Haard H J W, Spaan W J M, Middeldorp J M. Gene mapping and expression of two immunodominant Epstein-Barr virus capsid proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:3908–3916. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3908-3916.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Grunsven W M J, Spaan W J M, Middeldorp J M. Localization and diagnostic application of immunodominant domains of the BFRF3-encoded Epstein-Barr virus capsid protein. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:13–19. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber B, Brunner M, Preiser W, Doerr H W. Evaluation of 11 enzyme immunoassays for the detection of immunoglobulin M antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol Methods. 1996;57:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)01971-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiedbrauk D L, Bassin S. Evaluation of five enzyme immunoassays for detection of immunoglobulin M antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus viral capsid antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1339–1341. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1339-1341.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]