Abstract

The molecular architecture of pH-responsive amphiphilic block copolymers, their self-assembly behavior to form nanoparticles (NPs), and doxorubicin (DOX)-loading technique govern the extent of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. We observed that the choice of pH-sensitive tertiary amines, surface charge, and DOX-loading techniques within the self-assembled NPs strongly influence the release and stimulation of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in primary cardiomyocytes. However, covalent conjugation of DOX to a pH-sensitive nanocarrier through a “conditionally unstable amide” linkage (PCPY–cDOX; PC = polycarbonate and PY = 2-pyrrolidine-1-yl-ethyl-amine) significantly reduced the cardiotoxicity of DOX in cardiomyocytes as compared to noncovalently encapsulated DOX NPs (PCPY–eDOX). When these formulations were tested for drug release in serum-containing media, the PCPY–cDOX systems showed prolonged control over drug release (for ~72 h) at acidic pH compared to DOX-encapsulated nanocarriers, as expected. We found that DOX-encapsulated nanoformulations triggered cardiotoxicity in primary cardiomyocytes more acutely, while conjugated systems such as PCPY–cDOX prevented cardiotoxicity by disabling the nuclear entry of the drug. Using 2D and 3D (spheroid) cultures of an ER + breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and a triple-negative breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231), we unravel that, similar to encapsulated systems (PCPY–eDOX-type) as reported earlier, the PCPY–cDOX system suppresses cellular proliferation in both cell lines and enhances trafficking through 3D spheroids of MDA-MB-231 cells. Collectively, our studies indicate that PCPY–cDOX is less cardiotoxic as compared to noncovalently encapsulated variants without compromising the chemotherapeutic properties of the drug. Thus, our studies suggest that the appropriate selection of the nanocarrier for DOX delivery may prove fruitful in shifting the balance between low cardiotoxicity and triggering the chemotherapeutic potency of DOX.

Keywords: doxorubicin, nanocarriers, pH-responsive, cancer, cardiac effects, drug delivery, cardiotoxicity

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Anthracyclines [e.g., doxorubicin (DOX)] are highly effective anticancer drugs, widely used for the treatment of many childhood and adult malignancies, including breast, lung, gastric, ovarian, thyroid, and pediatric cancers, multiple myeloma, and sarcoma.1,2 DOX administration develops dose-related cardiomyocyte injury, including aberrant arrhythmias, ventricular dysfunction, and heart failure. The side effects were first described in 1971 in 67 patients treated for a variety of tumors.2–4 DOX-cardiomyopathy leads to premature termination of treatment in patients, which increases the likelihood of cancer relapse. Dose- and time-dependent DOX-cardiotoxicity can manifest acutely as well as years after discontinuation of treatment, leading to ventricular dysfunction, dilated cardiomyopathy, and heart failure.5–7 Studies showed a correlation between DOX-cardiotoxicity and increased cumulative dose, corresponding to a 5% risk with a cumulative dose of 400 mg/m2, 26% risk with 550 mg/m2, and 48% risk with 700 mg/m2.8 Clinically, patients with DOX-cardiotoxicity developed a reduced left ventricular enddiastolic pressure and suppressed the left ventricular ejection fraction because of impaired pumping capacity of the heart, resulting in dilated cardiomyopathy9 and congestive heart failure.10 To bypass the toxic effects of DOX, liposome-assisted formulations, such as Doxil (or Myocet) or PEGylated liposomes of DOX have been developed and extensively studied. These formulations are now commercially available and used for treating metastatic breast cancer as the primary therapy. Fundamentally, liposomal systems significantly reduced off-target accumulation of DOX in the heart and suppressed DOX-induced untoward cardiac activity to a significant extent. Numerous polymer-encapsulated or polymer-conjugated systems have also been formulated, which were found to prolong the plasma half-life and show higher efficacy of DOX in clinical and preclinical settings. Despite extensive studies during the past half-century, the molecular signaling pathways that underlie in the cardiotoxic effects of DOX remain obscure and those of polymer-assisted formulations remain underinvestigated.11 The pathogenesis of DOX-associated cardiomyopathy is a multifocal disease process whose pathological sequelae involve mitochondrial dysfunction, increased reactive oxygen species production, defects in iron handling, and contractile failure.12–14 Recently, we reported that both acute and chronic DOX-cardiomyopathy result from autophagosome accumulation, altered expression of mitochondrial dynamics, oxidative phosphorylation regulatory proteins, and mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction.15 Similar challenges in the understanding of cardiotoxic effects of DOX also persist when the drug is delivered via polymeric assemblies, and there is a scarcity of knowledge on how the mode of drug encapsulation inside polymeric nanocarriers (NCs) modulate cardiac toxicity within primary myocytes. Therefore, the primary goal of this study is to design a modular, DOX-loaded, pH-sensitive nanocarrier using amphiphilic block copolymers (Figure 1) and to use this construct to understand how structural elements of the copolymer control cardiac toxicity. We showed that, while breast cancer cells were efficiently affected by DOX immobilized in pH-responsive polymeric NCs, no drug-associated toxicity was evident only for DOX-conjugated NCs in cardiac myocytes at cytosolic and nuclear levels. We envision that our results will shed new light on the structure–activity relationship of stimuli-responsive NCs of DOX and how the molecular diversity of carrier systems protects and rescues cardiac cells from DOX-associated toxicity.

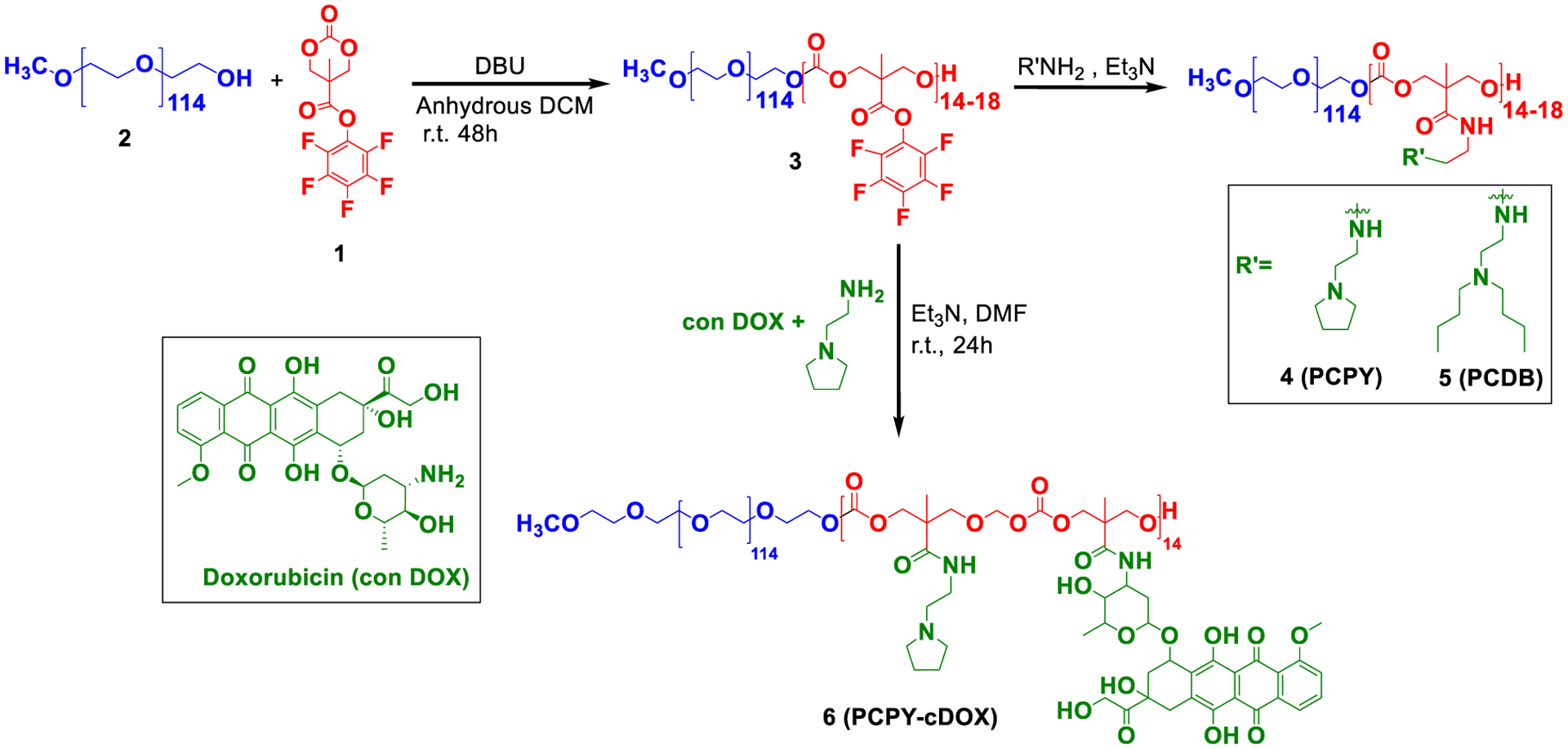

Figure 1.

Synthetic route toward various block copolymers for preparing DOX–NCs.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and anhydrous solvents were purchased from VWR, EMD Millipore. DOX hydrochloride was purchased from LC Laboratories. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer using TMS as the internal standard. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded using an ATR diamond tip on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 8700 FTIR instrument. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were carried out using a Malvern instrument (Malvern ZS 90). UV–visible and fluorescence spectra were recorded using a Varian UV–vis spectrophotometer and a Fluorolog3 fluorescence spectrophotometer, respectively. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies were carried out using a JEOL JEM2100 LaB6 transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA) with an accelerating voltage of 200 keV. 3D spheroid cultures were grown using the n3D kit purchased from Greiner Bio.

Cell Lines and Maintenance.

Primary Neonatal Rat Cardiomyocyte Culture.

We isolated neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCs) from the ventricles of 1–2 day old Sprague Dawley rat pups as described previously.15,20–22 Briefly, ventricular tissues excised from rat pups were digested with collagenase at 4 °C overnight with subsequent digestion in trypsin. Next, cells were preplated to remove cardiac fibroblasts, followed by plating of isolated cardiomyocytes at 1.5 × 106 cells per 10 cm2 plate in αMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic (Gibco) media. After 24 h, NRCs were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco) containing 2% FBS and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic and subjected to different treatments, as described previously. All cell culture treatments were repeated in three independent experiments.

Breast Cancer Cell Lines.

Two different breast cancer cell lines from ATCC, viz., MCF7 (ER+) and MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative), have been used in this study. The cells were grown in DMEM (HyClone, GE Healthcare Life Sciences), supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco).

Synthesis of PEG-b-poly(carbonate).

PEG-b-poly-(carbonates) (PEG-b-PC) was synthesized using poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG, Mn = 5000 g/mol) as the initiator via ring-opening polymerization of a monomer, viz., a pentafluorophenyl-protected bis(methoxy propionic acid) derivative. The synthesis of the monomer was performed as described by Hedrick et al.16 as follows (Supporting Information, Scheme S1): 21.7 g (55 mmol) of bis-(pentafluorophenyl)carbonate, 3 g (22 mmol) of 2,2-bis(hydroxymethyl)propionic acid (bis-MPA), and 0.7 g (4.6 mmol) of CsF were dissolved in 70 mL of anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the residue was redissolved in dichloromethane (DCM), following which a white precipitate was filtered off. The filtrate was extracted with sodium bicarbonate and water and was dried over MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated under vacuum. The product was recrystallized from a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of ethyl acetate/hexane to give the pentafluorophenyl ester as white crystals, which were filtered and dried in a desiccator and analyzed by 1H NMR (Supporting Information, Figure S1). PEG-b-PC block copolymers were synthesized following a procedure described earlier17 (Figure 1). Briefly, 30 mg (0.006 mmol) of mPEGOH (2) and 100 mg (0.3 mmol) of monomer (1) were dissolved in 3 mL anhydrous DCM under nitrogen, and then 1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (10.19 mg, 0.06 mmol) was added to the solution to facilitate polymerization. After stirring for 48 h at room temperature, the reaction was quenched by precipitating into diethyl ether and centrifuging at 7000 rpm (~5040 g) for 30 min. The supernatant was decanted, an equal volume of diethyl ether was added, and the solution was recentrifuged for another 30 min at the same speed to yield the polycarbonate block (3). The synthesized intermediate block copolymer, polycarbonate (PC, compound 3), was aminated with 2-pyrrolidine-1-yl-ethyl-amine (PY) to generate PCPY (compound 4) and N,N′-dibutylethylenediamine (DB) to generate PCDB (compound 5) in DMF at room temperature for 24 h. These compounds have been characterized and purified according to previously published reports.

Synthesis of Drug-Conjugated Polymers.

Copolymer 4 (PCPY) was selected for drug conjugation because of its pKa, which is more conducive to protonation at the endosomal pH. To synthesize the drug–polymer conjugate, we used the procedure previously used by our group and others to covalently attach primary amine-containing drug molecules via an amide linkage to the polymer backbone.18,19 Briefly, 100 mg (0.0075 mmol) of (3) was dissolved in 5 mL DMF and cooled in an ice bath; to this, 0.5 mL of DMF solution containing 23 mg (0.038 mmol) of DOX hydrochloride, 45 μL (0.34 mmol) of 2-pyrrolidine-1-yl-ethyl-amine, and a catalytic amount of triethylamine were added dropwise with constant stirring. The solution was brought to room temperature and allowed to stir for 24 h, followed by precipitation in a large excess of cold diethyl ether to generate PCPY systems covalently connected with DOX (PCPY–cDOX) (compound 6). The PCPY–cDOX conjugate was characterized by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 2) and aqueous phase gel permeation chromatography (Supporting Information, Figure S2A). To investigate the conjugation mechanism, two control polymers were prepared. In one system, no pH-sensitive tertiary amine was present, and the hydrophobic backbone of the polymer was stoichiometrically connected with DOX (PC–cDOX, compound 7). In the second control system, a pH nonresponsive amine, such as hexylamine (HX), was connected to the hydrophobic backbone of the polymer along with DOX, yielding PCHX–cDOX systems (compound 8). The synthetic protocol and NMR characterization of these control polymers are presented in the Supporting Information, Scheme S2 and Figure S2B. The composition of all synthesized polymers is summarized in Table 1.

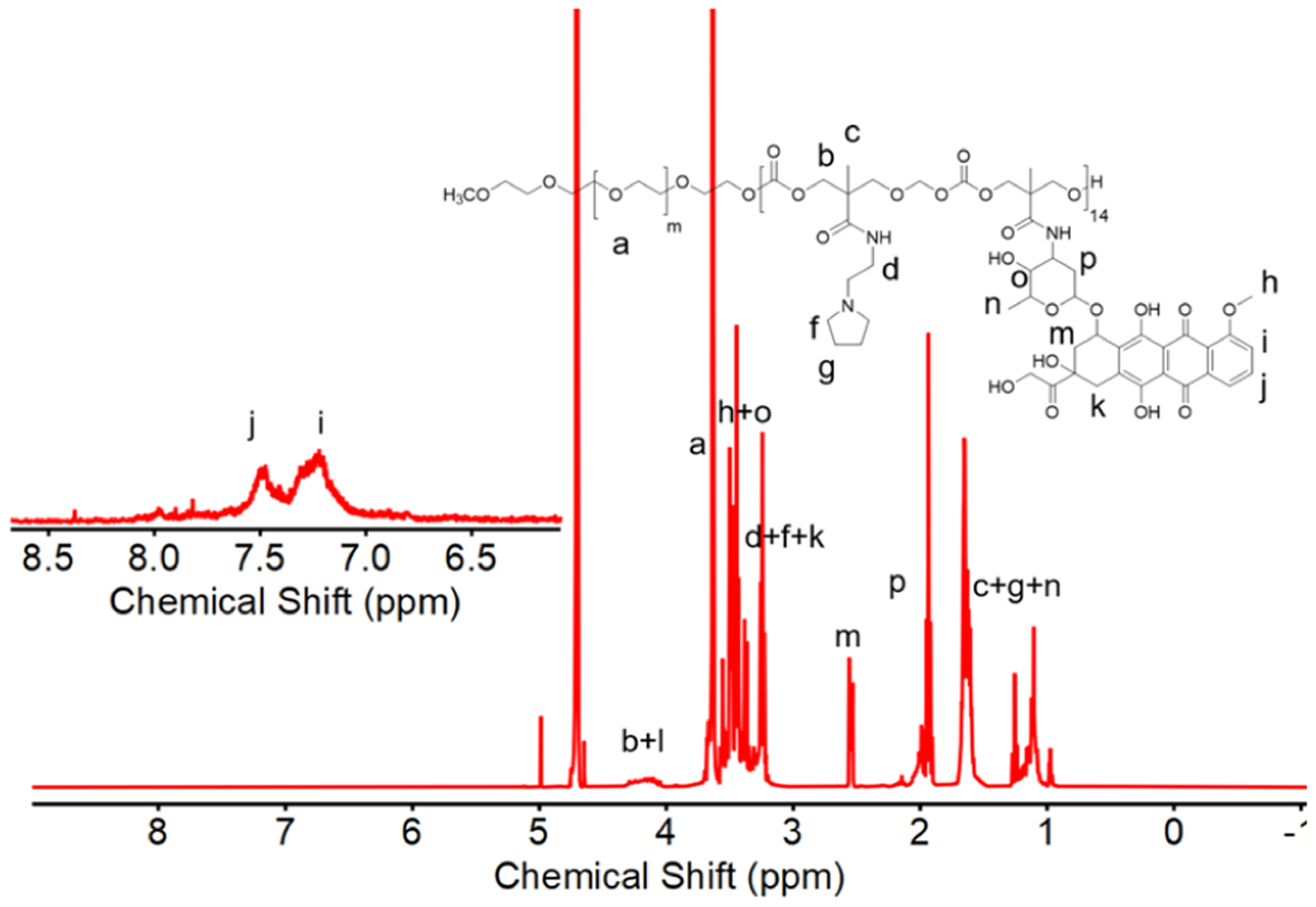

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum of PCPY–cDOX in D2O showing the characteristic peaks of DOX.

Table 1.

Composition of DOX-Conjugated Polymers

| PEG-initiated block copolymers | side chains | mode of DOX immobilization | degree of polymerization (DPn) (PC block) | [DOX]mol/[polymer]mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (3) | N/A | N/A | 18a | N/A |

| PCPY (4) | 2-pyrrolidine-1-yl-ethyl-amine | N/A | 18a | N/A |

| PCDB (5) | N,N′-dibutylethylenediamine | N/A | 18a | N/A |

| PCPY-cDOX (6) | 2-pyrrolidine-1-yl-ethyl-amine + DOX | covalent | 14b | 5c |

| PC-cDOX (7) | DOX | covalent | 17c | 17c |

| PCHX-cDOX (8) | hexylamine + DOX | covalent | 15c | 3c |

| PCPY-eDOX | Encapsulation | encapsulation | N/A | 5d |

| PCDB-eDOX | Encapsulation | encapsulation | N/A | 4d |

Determined by gel permeation chromatography using THF as an eluent.

Determined by gel permeation chromatography using water as an eluent.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Determined by UV–vis spectroscopy.

Quantification of DOX Payload in the Polymer–Drug Conjugate.

The PCPY–cDOX (6) system was a lyophilic solute. Therefore, to determine the amount of DOX within the conjugate, PCPY–cDOX (5 mg) was dissolved in 2 mL of a buffer of pH 7.4. After sonication for 30 min, the suspension was filtered through a 0.45 μm PES membrane filter. The amount of DOX in the filtrate was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 495 nm using UV–visible spectroscopy. DOX payload in the conjugate was estimated according to the following equation

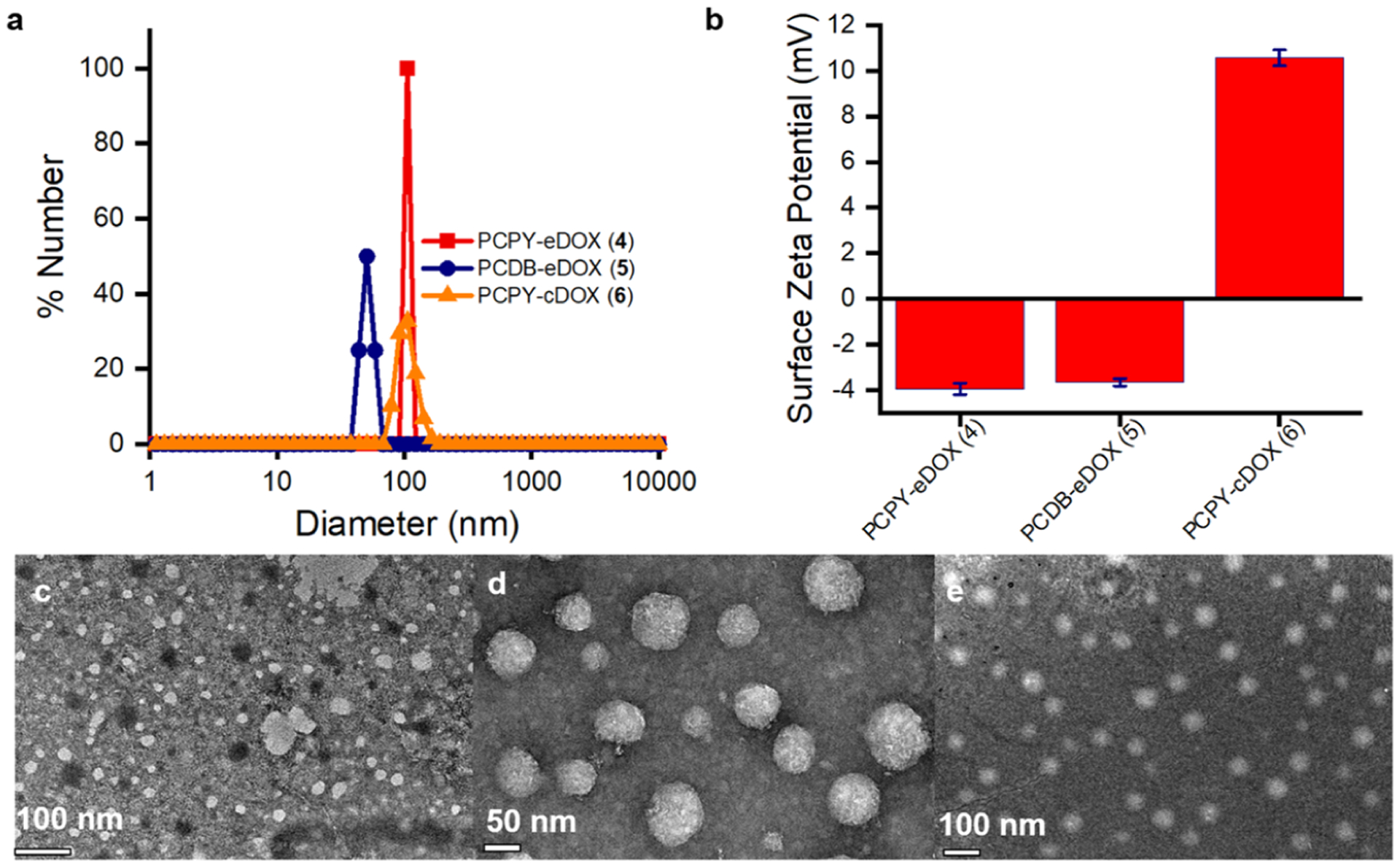

Particle Size and Zeta Potential Analyses of Nanoparticles.

The hydrodynamic diameters of the resulting nanoparticles (NPs) prepared from copolymers PCPY (4), PCDB (5), and PCPY–cDOX (6) were determined using DLS measurements at a scattering angle of 90°. For zeta potential measurements, a sample concentration of 10 mg/mL was used, and the zeta potential was determined in terms of electrophoretic mobility by taking an average of five readings. For all these measurements, the sample solution was filtered using a 0.2 μm PES filter.

Size Analysis Using TEM Imaging.

A drop of NP sample [obtained from copolymers PCPY (4), PCDB (5), and PCPY–cDOX (6)] was placed on a 300-mesh formvarcarbon-coated copper TEM grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 1 min and wicked off. Phosphotungstic acid 0.1%, with pH adjusted to 7–8, was dropped onto a grid and allowed to stand for 2 min and then wicked off. NPs have been investigated for their microstructure by TEM at 200 keV.

Preparation of Drug-Loaded NPs.

For the preparation of noncovalently encapsulated DOX NPs of block copolymers, either PCPY (4) or PCDB (5) block copolymer (10 mg) was dissolved in 250 μL of DMSO in the presence of 5 mg of DOX hydrochloride. The solutions were added dropwise to a stirred solution of 750 μL of PBS buffer (pH 7.4). The solution was stirred overnight, followed by dialysis using a Float-A-Lyzer (MWCO: 3.5–5 kDa) against 800 mL of PBS buffer (pH 7.4) to generate PCPY- or PCDB-encapsulated DOX, that is, PCPY–eDOX and PCDB–eDOX systems, respectively. These NP suspensions were analyzed using UV–vis spectroscopy for quantification of the amount of drug loading within NPs. For drug encapsulated in NPs, the following formula was used to calculate the encapsulation efficiency

For generating NPs from the conjugated system, 10 mg of PCPY–cDOX (6) was dissolved in 250 μL of DMSO, and nanoprecipitated in 750 μL of PBS buffer (pH 7.4). Similar purification processes as described above for noncovalently encapsulated systems were used. It is important to note that PCPY–cDOX (6) is a lyophilic colloid and is soluble in PBS. However, direct dissolution of PCPY–cDOX in water does not yield a uniformly dispersed population of NPs, and the polydispersity of the resulting suspension was found to increase with time (Supporting Information, Figure S3).

In Vitro Drug Release Experiments.

Drug release experiments were conducted by taking 1 mL of the drug-loaded NP solution spiked with 10% FBS in a Float-A-Lyzer (MWCO: 3.5–5 kDa). Noncovalently stabilized NP solutions, that is, PCPY–eDOX and PCDB–eDOX systems, as well as polymer–drug conjugated NPs (PCPY–cDOX, 6), were used. The solution was introduced into the inner chamber of the Float-A-Lyzer and the outer chamber was filled with 5 mL of buffer at the desired pH (7.4 and 5.5 for the PCPY and PCPY–cDOX systems and 7.4 and 4.5 for the PCDB system). A specified volume of the bulk solution was withdrawn periodically and replaced by an equal volume of the fresh buffer of similar pH to maintain the sink condition. Of note, pH 4.5 was used to mimic lysosomal pH conditions.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analyses.

NRCs were washed with PBS and lysed with CelLytic M (Sigma-Aldrich) lysis buffer containing a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), as described in refs.15,20,22 Next, the lysed cells were homogenized by sonication and centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to sediment any insoluble material. The protein concentration of the soluble cardiomyocyte lysates was measured using the modified Bradford reagent relative to a BSA standard curve (Bio-Rad) in a 1 mL cuvette on a DS-11 FX+ spectrophotometer (DeNovix, Wilmington, DE). Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE using precast 7.5–15% Criterion Gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% nonfat dried milk and exposed to primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting: anti-LC3B (1:1000, 2775, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-p53 (1:1000, sc-1314, Santa Cruz Bio-technology), and anti-GAPDH (1:1000, MAB374, Sigma-Aldrich). Membranes were subsequently washed, incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch), developed with ECF reagent (Amersham), and imaged using ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Ponceau S protein staining on the transferred membranes was used to confirm equal loading. Protein band densitometry analyses on scanned membrane images were carried out using NIH ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD).

Biochemical Assays.

Lactate Dehydrogenase Release Assay for Cardiac Myocytes.

Following treatments, culture media were collected and cleared by centrifugation at 5000g for 10 min. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release into culture media was measured using a cytotoxicity detection kit (Roche) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.15,20–22 Color development was measured using a microplate absorbance reader at an absorbance of 492 nm (Bio-Rad).15,20–22

Cancer Cell Viability Assay.

The cytotoxicity of drug-conjugated NPs (PCPY–cDOX, 6) and of the free drug was tested on two different breast cancer cell lines, viz., MCF7 and MDA-MB-231. For this experiment, 5000 cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates and, after 24 h, were treated with different concentrations of drug-conjugated NPs and the equivalent concentration of conventional DOX formulation (free DOX). After incubating the cells for 72 h, cell viability was evaluated by the MTS assay. Cell viability was calculated using the following equation

Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy.

Confocal Microscopy of Cardiac Myocytes.

To visualize the subcellular distribution of DOX and the prepared NPs carrying DOX, NRCs were plated on Lab-Tek II chamber slides (Thermo Scientific, 154461) at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well, as reported earlier.15,20–22 Next, NRCs were treated with DOX (dissolved in DMSO) at 5, 10, and 25 μM for 24 h. NRCs treated with only DMSO served as an experimental control. PCPY–cDOX, PCPY–eDOX and PCDB–eDOX NPs were treated at described concentrations. NPs containing no DOX served as control. After 24 h, NRCs were immediately washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min as per manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained with 4′−6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Invitrogen). NRCs were then mounted with VECTASHIELD HardSet antifade mounting media for fluorescence (Vector Laboratories). To assess the intracellular distribution of DOX, cardiomyocytes were subsequently observed on a Nikon A1R high-speed confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) using an ×60 oil objective (NA = 1.4) and imaged using Nikon NIS-Elements C software. DOX accumulation was detected using a 561 nm excitation laser coupled to 575–625 nm emission bandwidths on a GaAsP PMT detector on a Nikon A1R confocal microscope.15 In a separate set of experiments, following 2 h of treatment, NRCs were immediately stained with LysoTracker Deep Red dye (excitation/emission: 647 nm/658 nm), L12492, Molecular Probes, (Invitrogen) to visualize lysosomes, then fixed, counterstained, and mounted. Lysosomes were then visualized using a far-infrared 640 nm excitation laser with 650–720 nm emission bandwidths on a Nikon A1R confocal microscope using a ×60 oil objective (NA = 1.4). Lysosomes are presented as pseudo-colored green organelles in representative images along with DOX accumulation in red. For all cardiomyocyte treatment groups with DOX and DOX-loaded NPs, DOX distribution in cardiomyocytes was measured (>60–100 cardiomyocytes in each group, with a total of 1270 cardiomyocytes) in the acquired high-magnification red channel microscopy images from three independent experiments through the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) [CTCF = integrated density – (area of selected cardiomyocytes × mean fluorescence of background readings)] assessment using NIH ImageJ (v1.52a) software.23–25 All image observations, acquisitions, and analyses were conducted in an investigator-blinded manner through α-numerical labeling of the slides and images.

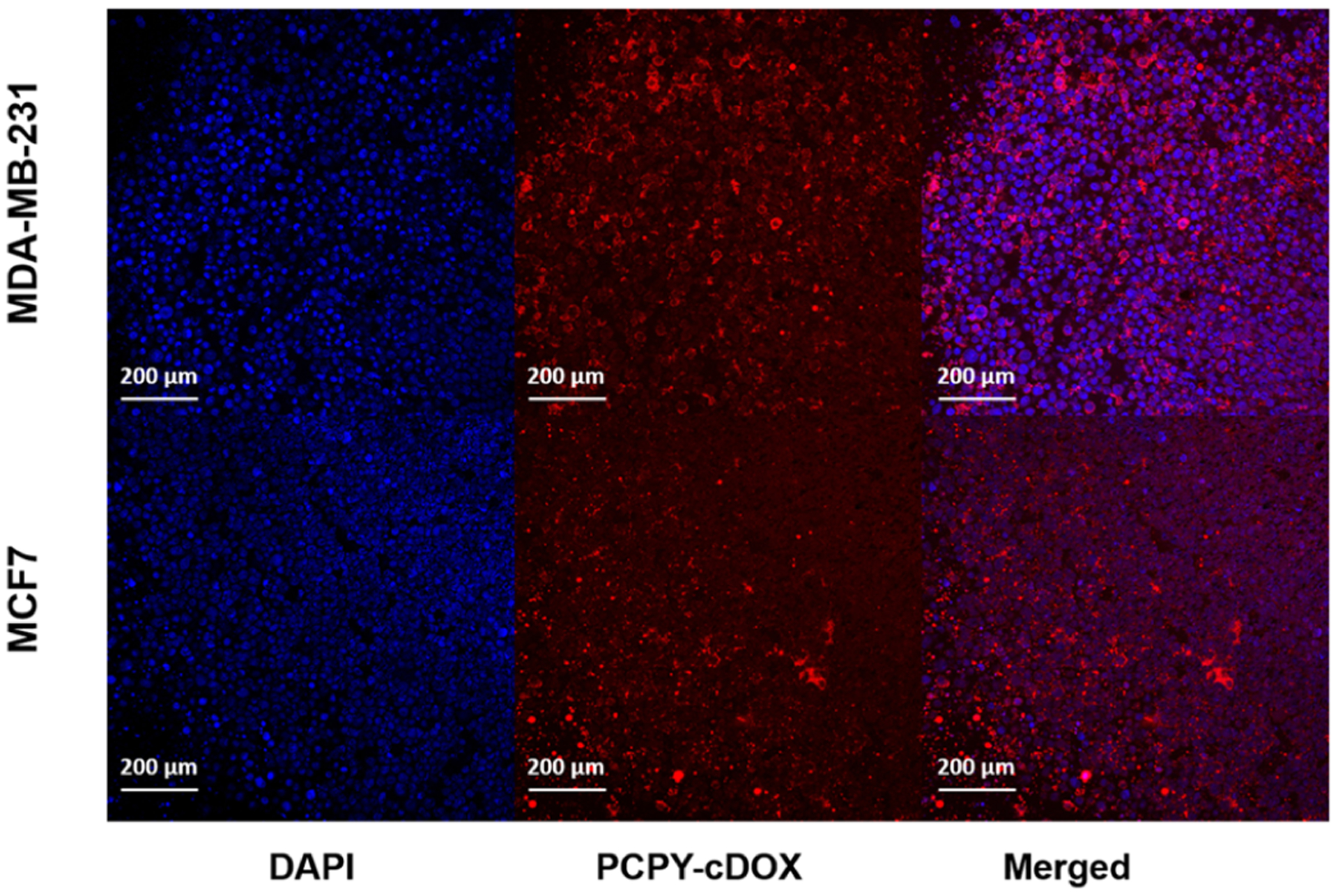

Confocal Microscopy of Monolayer and Spheroid Culture of Breast Cancer Cells.

MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded onto the ibidi glass-bottom dish (35 mm) at 1 × 105 cells per well and grown overnight. Cells were then incubated with NPs obtained from PCPY–eDOX and PCPY–cDOX at 37 °C in DMEM high-glucose medium for 1 and 3 h. At the end of this period, cells were washed with PBS, followed by the addition of DAPI and phalloidin, and analyzed using a confocal fluorescence microscope. Spheroid cultures of MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were used to study the penetration and uptake of drug-loaded NPs. To grow these spheroid cultures, cells were grown to 70% confluency and treated with the NanoShuttle (n3D Biosciences courtesy Greiner Bio) solution overnight. Following incubation, the cells were washed, trypsinized, and then seeded in a 96-well plate with a cell-repellent surface (n3D Biosciences courtesy Greiner Bio) at a seeding density of 1 × 106 cells per spheroid. The cells were incubated on the spheroid drive (n3D Biosciences, Greiner Bio) at 37 °C overnight in an incubator. After 24 h of incubation, and when the spheroids were visible, they were treated with NPs and incubated for another 24 h. Following this incubation period, the spheroids were washed with PBS (while placed on a holding drive so as not to disrupt the spheroids), stained with DAPI, and analyzed using a confocal fluorescence microscope. The confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope equipped with a LSM700 laser scanning module (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) at 40× magnification with a 40×/1.3 Plan-Apochromat lens.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. All statistical tests were done with GraphPad Prism (v8.2.1) software (San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Synthesis and Characterization of the DOX-Conjugated Block Copolymer.

NPs typically enter cells through endocytosis, and while contained in the endosomal compartment, they undergo an environmental pH decrease from early to late endosomes and lysosomes.26 We have previously reported the synthesis and characterization of pH-responsive block copolymers, such as those for PCPY (4) and PCDB (5) systems for delivering chemotherapy, that is, gemcitabine, a hedgehog inhibitor (i.e., GDC 0449), or an extracellular receptor kinase-inhibitor (SCH 772984),18,27 exclusively for pancreatic cancer. These systems show a pH-dependent conformational switch under low pH conditions to release their therapeutic cargo. Our primary focus in this work is to show how molecular connectivity, trigger type, and drug-loading method within NPs differentially affect the toxicity behavior of a loaded chemotherapeutic against breast cancer cells and cardiac cells. This is an exciting proposition as the primary chemotherapy of choice for breast cancer, that is, DOX triggers a cardiotoxic effect when administered either via a conventional or NP-assisted route. We designed a set of PEGylated block copolymers of polycarbonates with diversified architectures of pH-sensing side chains, where DOX was loaded either covalently or noncovalently (Table 1). First, we prepared a PEGylated polycarbonate variant with covalently conjugated DOX. We selected PCPY as a polymer of choice for synthesizing the polymer–DOX conjugate (Figure 1, PCPY–cDOX, 6) based on its pKa value, which causes protonation of the hydrophobic block at the endosomal–lysosomal pH. Nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) and IR spectroscopy were used to characterize PCPY–cDOX (6). As observed from Figure 2, the –CH2–C–CH2– signals from the hydrophobic arms of PCPY–cDOX were observed at δ 4.3 and 4.5 ppm, while the aromatic signals from DOX were visible at 7.2 and 7.5 ppm, respectively. The characteristic DOX signals were observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of PCPY–cDOX constructs at δ 7.2 (br, d, 1H, Ar-H), 7.4 d, (1H, Ar H), 4.1 (br, m, 1H, –OHCH2–CH(O′)), and 3.6–3.8 (m, 2H, –OH–CH2–CH (O) R′). The amount of DOX conjugated was estimated using UV–visible spectroscopy. The molecular weight of PCPY–cDOX was analyzed by gel permeation chromatography using water as an eluent. The number-average molecular weight of PCPY–cDOX was found to be 9.6 kDa with a polydispersity index of 1.07, indicating that the conjugate does not contain any free DOX (Supporting Information Figure S2A).

To confirm whether the conjugation of DOX to the PCPY block copolymer was, in fact, mediated through an amide linkage, we prepared several control polymers, where the hydrophobic polycarbonate block was substituted with DOX alone (no tertiary amines, PC–cDOX, 7). IR spectra for these copolymers showed amide stretching signals at 1642 cm−1 (Supporting Information Figure S4). A 13C spectrum of both the stoichiometrically quantitative DOX conjugated to the PC–cDOX (with no tertiary amine) variant and PCPY–cDOX showed the presence of the amide carbonyl group, which led us to conclude that the conjugation of the drug to the polymer backbone was via O=C–NH2 bonding (see the Supporting Information Figure S5).

Self-Assembly of Free or DOX-Conjugated Block Copolymers into NPs.

The average hydrodynamic diameter of the DOX-loaded PCDB system (5) was found to be 51.02 ± 6.3 nm (n = 3), while that from the PCPY system (4) was 106.3 ± 19.3 nm (Figure 3a). This change in diameter may be attributed to the difference in the structures of the flexible linear amines in the side chains of PCDB (compound 5), as compared to the rigid cycloaliphatic units in PCPY systems (compound 4), which affected their packing parameters.30,31 The drug–polymer conjugate (PCPY–cDOX, 6) displayed an average hydrodynamic diameter of 113.5 ± 17.3 nm (n = 3). The NPs are formed from local hydrophobic interactions among PC-derived blocks (containing amines, or amine and DOX) shielded by the PEG shell. To our surprise, we found that the surface charge (zeta potential) of the DOX-loaded PCPY or PCDB nanosystems was anionic (contributed from PEG) with values of −3.96 ± 0.25 and −3.67 ± 0.16 mV for PCPY–eDOX and PCDB–eDOX, respectively, while those derived from PCPY–cDOX exhibited a mildly positive zeta potential of 10.35 mV (Figure 3b). The surface positive charge might be attributed to π-stacking of DOX inside the NP interior, resulting in polarity shift at the particle surface. The difference in the surface charge may be attributed to the difference in the structures of the tertiary amines, the PCDB system being composed of linear dibutyl amine chains as opposed to the closed pentacyclic structure of the PCPY system. In the case of the drug-conjugated system, the difference in surface charge might be explained by the interactions of aromatic resonance-stabilized structure of DOX and the cationic nature of tertiary amine moieties. TEM of each of these samples showed a distinct population of NPs at pH 7.4, which were of spherical morphology (Figure 3c–e). The particles exhibited a smaller diameter when observed through TEM than their hydrodynamic diameter obtained via DLS, most likely due to the shrinkage in the hydrophilic corona, as the samples were dried and subjected to a 200 keV beam.

Figure 3.

(a) DLS of NPs resulting from the self-assembly of drug-encapsulated polymer (4, PCPY–eDOX) and (5, PCDB–eDOX) as well as of the drug-conjugated polymer (6, PCPY–cDox). (b) The corresponding zeta potential values of nanosystems, PCPY–eDOX, PCDB–eDOX, and PCPY–cDOX. TEM images of DOX-loaded NPs obtained from (c) PCPY–eDOX, (d) PCDB–eDOX, and (e) PCPY–cDOX systems.

Determination of the Loading Content and Payload of Various Polymeric Constructs.

We used the pH-responsive polymers, PCPY (4) and PCDB (5), to encapsulate DOX via noncovalent encapsulation. We also prepared NPs from PCPY–cDOX (6) systems, where DOX was connected to the polymer scaffold covalently via an amide linkage. The loading content of DOX within PCPY and PCDB systems was found to be 2.95 (±0.35) and 2.32 (±0.64)%, respectively. In the conjugated system, that is, PCPY–cDOX, the loading content of DOX had increased at least by ~5-folds than either of the encapsulated systems. In PCPY–cDOX, the DOX payload was found to be ~10.3 (±3.15)% when measured via UV–vis spectroscopy (Supporting Information Figure S6).28,29

Spatiotemporal Release of Encapsulated/Conjugated Drug.

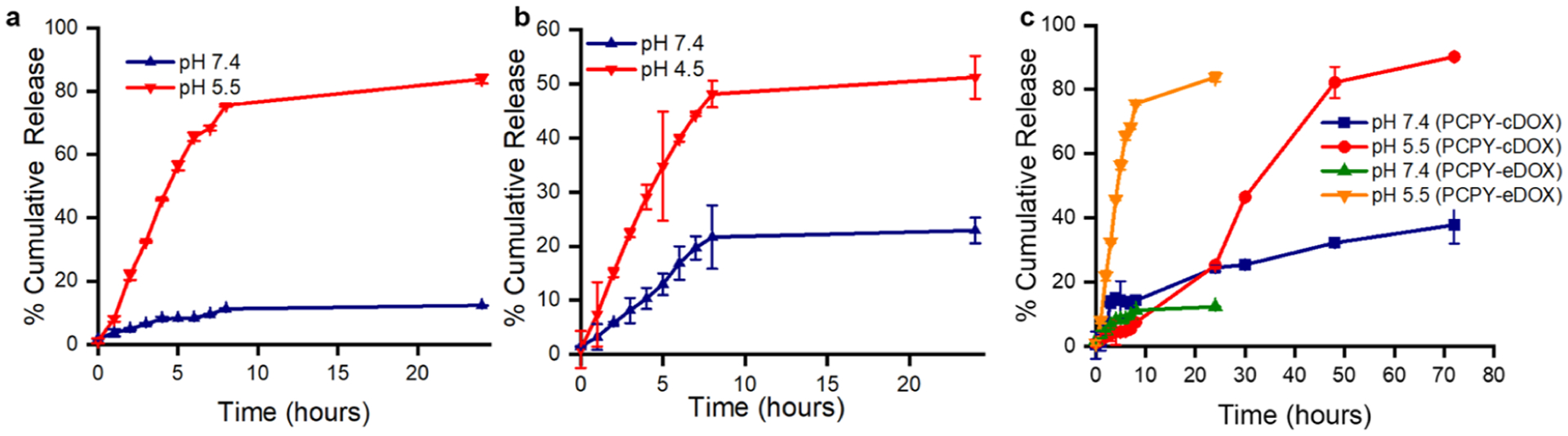

We conducted in vitro release experiments with the synthesized carriers under different pH conditions to assess the effect of structural components and DOX-loading techniques on their pH-sensitive DOX-delivery capacity in the presence of 10% FBS.1,32,33 Healthy cardiac myocytes within heart tissues strictly maintain their microenvironmental pH and electrolyte balance, equilibrated at pH 7.4. However, tumor cells, because of their altered metabolic phenotype, decrease the pH of the microenvironment in the extracellular compartment to pH ~6.5.34 Intracellular acidity, which is mostly localized in the early endosome (pH 6.5–5.5) to the late lysosome, can reach as low as 4.5 and is preserved for most types of cells, including cancer cells.26,35–37 To evaluate the comparative effect of dynamically changing pH status within cellular compartments of cancer cells and cardiac cells on the structural diversity of NCs, we encapsulated or covalently conjugated DOX within a structurally different pH-sensitive polycarbonate assembly. Our primary objective was to identify how a pH-sensitive polymeric assembly enables drug release into cancer cells and disables drug release into cardiac cells. To understand the effect of encapsulation or conjugation techniques on DOX release from the prepared NCs intracellularly, we carried out DOX dissolution studies from compound PCPY–cDOX (6) in the presence of 10% FBS at pH values 7.4 and 5.5, while for the PCDB system release studies were carried out at pH values of 7.4 and 4.5 due to the lower pKa of the dibutyl amine side chains. We found out that PCPY–cDOX showed a faster release of DOX at pH 5.5 compared to the physiological pH of 7.4 (Figure 4a). When comparing with DOX-encapsulated NCs (i.e., PCPY–eDOX and PCDB–eDOX), we found that the drug–polymer conjugate (PCPY–cDOX) displayed a sustained release of DOX with less than 35% release at pH 7.4 at the end of 3 days (Figure 4b). This observation indicated that PCPY–cDOX systems are more efficient in sustaining the release of drug at pH 7.4 and more effective at acidic pH that usually resides in the tumor microenvironment, as well as in the early endosome.18,38 The PCPY–cDOX system, in an acidic environment, released over 80% of its payload at the end of 72 h (Figure 4c). When compared to an encapsulated system (constructed from polymer 4) with the same polymeric backbone, it was observed that ~80% of the drug was released within 24 h at an acidic pH. This led us to infer that our approach to conjugate DOX with PC through covalent bonding results in not only a pH-mediated release but also a sustained release of the drug, as observed by other groups.19,39,40 We observed that the cumulative release of PCPY–eDOX was slightly slower than that of PCPY–cDOX (conjugated system) at pH 7.4. This could be attributed to the difference in surface charge of PCPY–eDOX (negative) and PCPY–cDOX systems (positive), which either hindered or accelerated the diffusion of liberated DOX into the bulk media.

Figure 4.

Release of encapsulated DOX from (a) PCPY–eDOX (4), (b) PCDB–eDOX (compound 5), and (c) conjugated system (PCPY–cDOX) NPs in the presence of 10% FBS.

To ascertain whether the pH-based differential release was driven by the pH-responsive units of tertiary amines or an inherent property of the drug itself, we used two control polymers, that is, PC–cDOX (7), which is connected only to DOX and is devoid of any tertiary amines, and another block copolymer, PCHX–cDOX (8). For the latter, the hydrophobic block was decorated with nonpH-responsive amines, such as hexylamines. We conducted release experiments at different pH levels with these block copolymers (Supporting Information, Figure S7). We found that no differential release of DOX was observed in the case of these control polymers at different pH values, which indicated that pH responsivity was driven mostly by the tertiary amine moieties attached to the hydrophobic segment of PCDB and PCPY systems.

Cardiomyocyte Uptake and Cytotoxicity Studies of Encapsulated DOX–NCs.

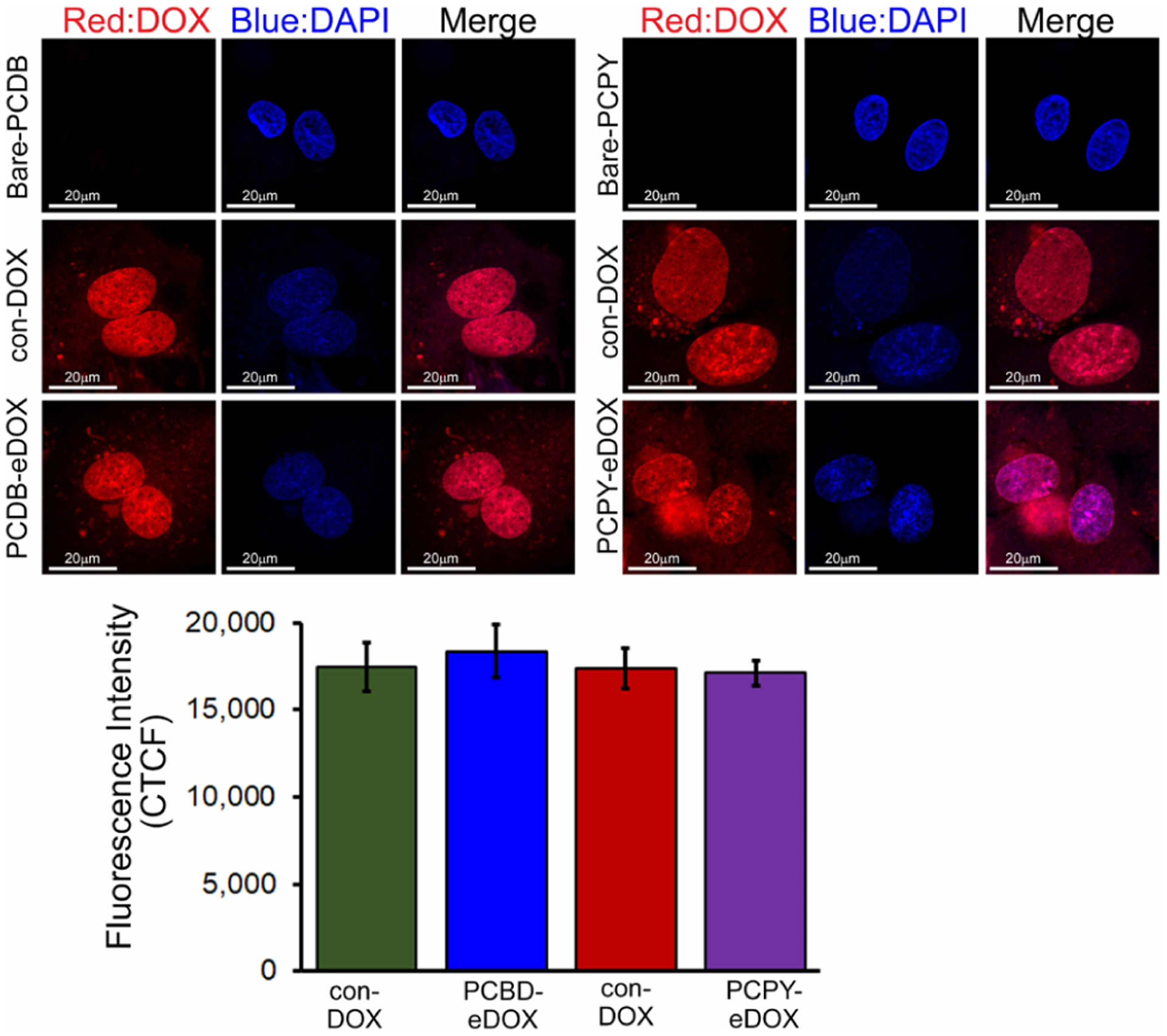

We first set out to identify the cardiotoxic impact of DOX-encapsulated NCs, that is, PCDB–eDOX and PCPY–eDOX systems on cardiomyocytes. To test the effects of encapsulated DOX-loaded NCs directly on cardiomyocytes, we treated NRCs with DOX and vehicle control. In our earlier studies, we reported that conventional DOX-treatment (con-DOX) (1, 5, 10, and 25 μM, 24 h) in NRCs dose-dependently impaired autophagy activity, induced mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction, and altered mitochondrial dynamics, recapitulating the in vivo DOX-cardiomyopathy.15 Therefore, we treated the NRCs with 10 μM conventional (unencapsulated) formulation of DOX (abbre viated as con-DOX), PCDB–eDOX, and PCPY–eDOX for 24 h. The equivalent concentration of DOX was used for all three treatments and polymeric formulations. The DOX concentration in polymeric formulations was calculated based on drug loading. Bare-PCPY (4) or PCDB (5) was used as negative control (Figure 5). Confocal fluorescence microscopy images showed that both PCDB–eDOX and PCPY–eDOX released DOX intracellularly, presumably through the endosomal–lysosomal pathway, ultimately causing nuclear localization like that of con-DOX. Immunocytochemistry images of PCPY–eDOX-treated cardiomyocytes showed less nuclear localization of DOX compared to that of PCDB–eDOX (Figure 5). This is most likely because, under in vitro conditions, the pKa of PCPY side chains is higher than the late endosomal–lysosomal pH, leading to complete ionization of the block copolymer and subsequent destabilization of the PCPY–eDOX construct, thereby leading to DOX release.

Figure 5.

Confocal fluorescence microscopic images showing DOX distribution in cardiomyocytes in vitro (10 μM, 24 h). Confocal microscopy images show that both the PCDB–eDOX and PCPY–eDOX release DOX ultimately causing nuclear localization like that of con-DOX. The vehicle, bare-PCDB, and bare-PCPY show no effect. The bottom panel shows the corresponding CTCF analysis for the images.

On the other hand, as PCDB systems are partially ionized, a reduced amount of DOX was released and translocated to the nucleus because of partial destabilization of PCDB–eDOX NCs. Con-DOX, in its free form, quickly enters the nucleus and intercalates with DNA strands as compared to the drug released from the NCs. This is because free small molecular drugs such as DOX immediately equilibrate between the cell and the nuclear membrane. PCPY–eDOX or PCDB–eDOX requires an additional kinetic step, that is, the release of DOX from the NP membrane, before such equilibration takes place. In fact, such free diffusion is the principal reason for cardiotoxicity with the traditional con-DOX treatment.

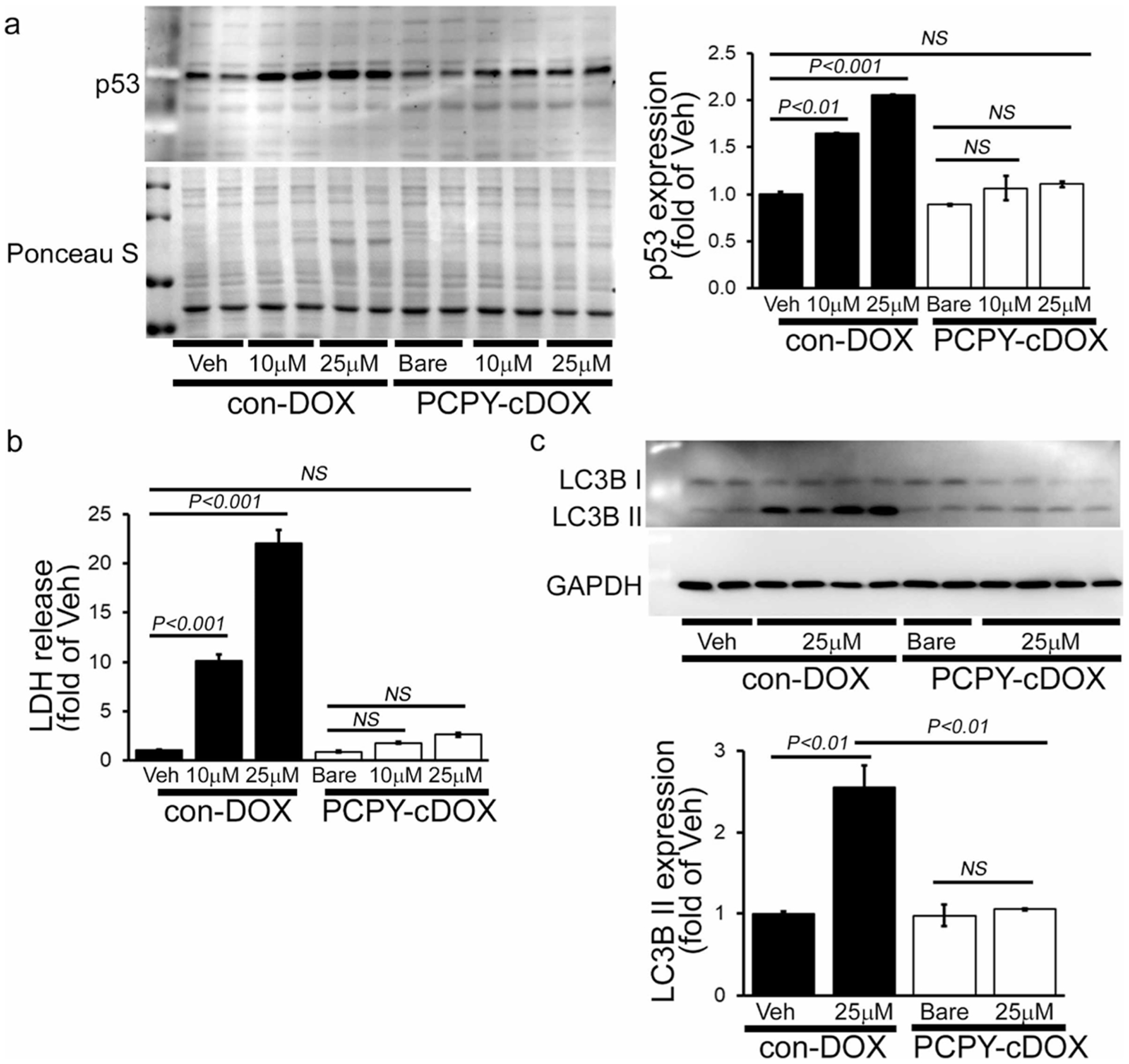

We then performed Western blot analysis to observe the p53 protein expression in NRCs, which is known as the central mediator of molecular events that lead to the development of cardiotoxicity.41 Both PCDB–eDOX and PCPY–eDOX showed an increased level of p53 protein expression like con-DOX (Figure 6a). We also observed cellular damage by measuring LDH release in NRCs21 and found increased LDH release under all the treatment conditions (Figure 6b). Finally, we measured the LC3B II protein level to monitor autophagy15 and found significantly increased LC3B II expression indicating impaired autophagy in NRCs (Figure 6c). These biochemical observations agree with our confocal fluorescence microscopy-based observations, where PCDB–eDOX and PCPY–eDOX showed nuclear localization similar to con-DOX in inducing cardiotoxicity, thus indicating the relationship between nuclear localization, NP destabilization, and pH-dependent dissociation degree of NP-forming polymers.

Figure 6.

Cardiomyocyte toxicity by treatment with con-DOX, PCDB–eDOX, and PCPY–eDOX (10 μM, 24 h) in cardiomyocytes. (a) Representative Western blot and densitometric quantitation showing increased p53 expression in NRCs. (b) DOX-induced LDH release in NRCs. (c) Representative Western blot and densitometric quantitation showing increased LC3II expression in NRCs. Bars represent mean ± SEM; n = 3 experiments.

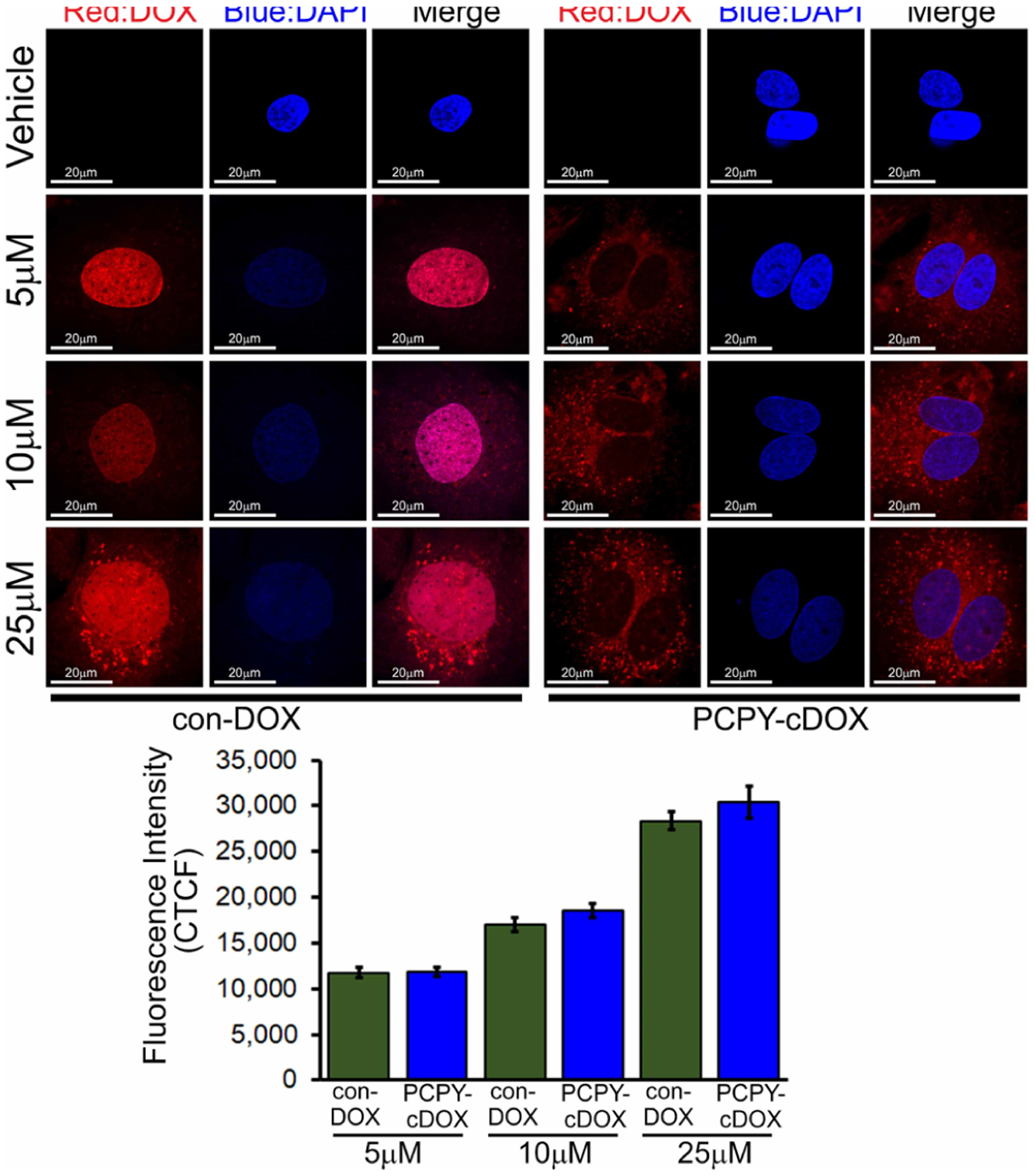

Cardiomyocyte Uptake and Cytotoxicity Studies of Conjugated DOX NCs (PCPY–cDOX).

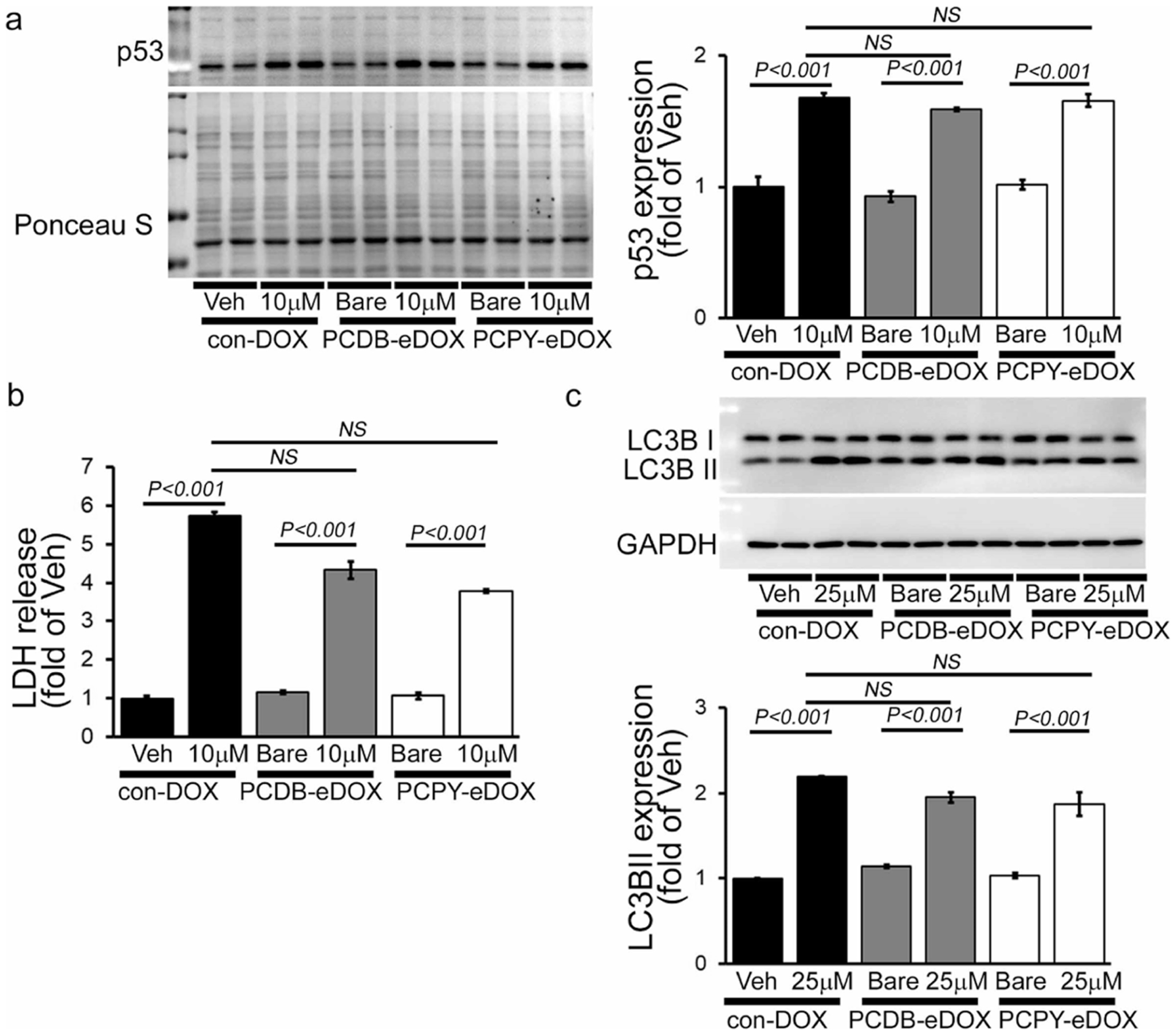

As the PCPY–cDOX systems were found to be positively charged, we expected the carriers to be cytotoxic to cancer cells as well as to healthy cells while cardiotoxic to heart cells. Cationic NPs are shown to interact with the negatively charged cell membrane, which promotes nonspecific penetration of the latter inside cells. To validate this hypothesis, we tested the effects of conjugated DOX-loaded NCs directly on cardiomyocytes. We treated primary cardiomyocytes (NRCs) with con-DOX, PCPY–cDOX, and vehicle (Figure 7). To our surprise, and in contrast to encapsulated DOX-loaded NCs, PCPY–cDOX at several different doses applied to cardiomyocytes stayed (5, 10, and 25 μM; 24 h) in the cytosol and did not release free DOX, whereas con-DOX completely localized into the nucleus. Cytosolic localization of con-DOX was observed at high doses of DOX (25 μM, 24 h) (Figure 7). Vehicle and bare-PCPY were used as negative controls.

Figure 7.

Confocal fluorescence microscopic images showing DOX distribution in cardiomyocytes in vitro (10 μM, 24 h). Confocal fluorescence microscopic images showing con-DOX and PCPY–cDOX uptake and localization in cardiomyocytes. As shown earlier in Figure 5, bare-PCPY (no drug) does not show any effect. Bottom panel shows the CTCF data for the image.

Next, we performed Western blot analysis to observe the p53 and LC3 protein expression (Figure 8). Though con-DOX showed a dose-dependent increase in cell death and impairment of autophagy, PCPY–cDOX showed no changes in p53 (Figure 8a) and LC3II (Figure 8c) protein expression as well as LDH release in cardiomyocytes (Figure 8b). Therefore, our data suggest that treatment with PCPY–cDOX can abrogate the classical cellular toxicity such as cell death and impaired autophagy, as observed with con-DOX.

Figure 8.

Cardiomyocyte toxicity by treatment with con-DOX and PCPY–cDOX (5 μM, 10 μM, and 25 μM; 24 h) in cardiomyocytes. (a) Representative Western blot and densitometric quantitation showing increased p53 expression in NRCs. (b) DOX-induced LDH release in NRCs. (c) Representative Western blot and densitometric quantitation showing increased LC3II expression in NRCs. Bars represent mean ± SEM; n = 3 experiments.

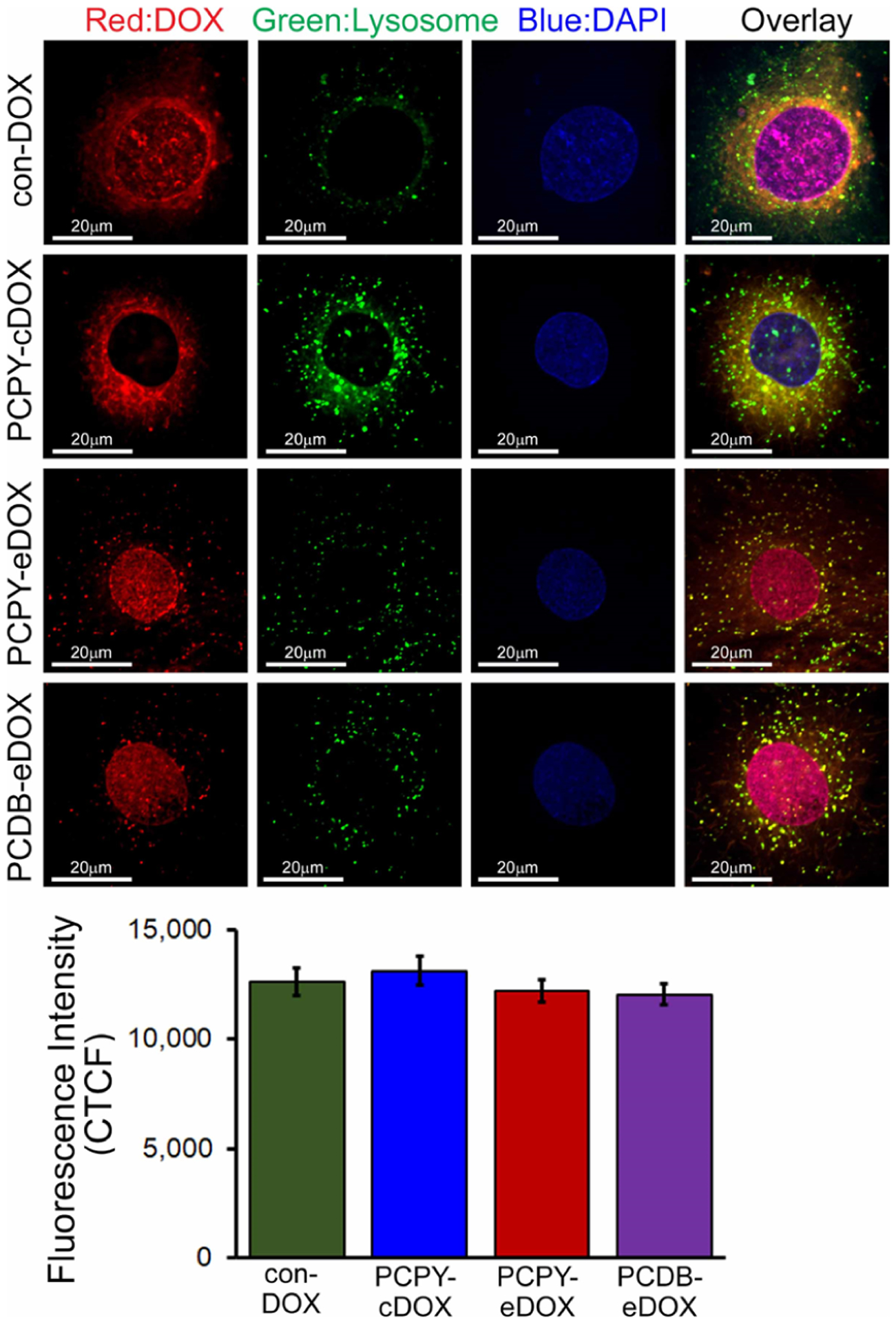

NPs usually enter cells through endocytosis. Upon cellular internalization, sequential protonation of different domains of NCs along the endosomal–lysosomal pathway is responsible for the diffusion of drugs out of the nanocarrier matrix into the cytosolic space.42 To examine the effect of pH responsiveness on DOX release within the intracellular environment, we treated cardiomyocytes with DOX-loaded NCs (encapsulated systems derived from PCDB and PCPY and the conjugated system derived from PCPY–cDOX). We investigated the intracellular trafficking of DOX by confocal microscopy using LysoTracker (Figure 9). As DOX released from encapsulated NCs (PCDB–eDOX and PCPY–eDOX) showed nuclear localization within 24 h of treatment in cardiomyocytes, we monitored the nanocarrier uptake via the endosomal–lysosomal compartment at an earlier time point (2 h after treatment) where they may release the drug. For this purpose, we used LysoTracker, which is a small, membrane-permeable dye that nonspecifically labels mild to strong acidic membranous structures such as lysosomes, endosomes, phagosomes, and autophagosomes.43 After 2 h of incubation with DOX-loaded NCs, the encapsulated DOX-loaded NCs (PCDB–eDOX and PCPY–eDOX) showed uptake and localization in endosomes–lysosomes on cardiomyocytes as well as the DOX released from these NCs was found to localize to the nucleus (Figure 9). All the con-DOX was found mostly to localize in the nucleus and some in the cytosol.

Figure 9.

Confocal fluorescence microscopic images showing lysosomal uptake of DOX in cardiomyocytes in vitro (10 μM, 2 h). Confocal images showing the con-DOX, PCDB–eDOX, PCPY–eDOX, and PCPY–cDOX uptake and localization in lysosomes on cardiomyocytes. The bottom panel shows the corresponding CTCF analysis for the images.

Interestingly, the conjugated DOX-loaded NCs (PCPY–cDOX) localized into the cytosol with very little accumulation in the endosomes–lysosomes and was not found in the nucleus. These data suggested that pH-responsive encapsulated DOX-loaded NCs were disrupted by the lysosomal pH drop where DOX was released and subsequently diffused into the nucleus where it could bind to the DNA. However, the conjugated DOX-loaded NCs (PCPY–cDOX, 6), because of their mild cationic charge, engaged negatively charged cell membranes to gain cellular internalization escaping the endocytosis and subsequent endo–lysosomal transport. Therefore, the conditionally unstable amide bond remained intact, and the nanocarrier did not release any DOX from the NCs rendering it devoid of the cardiomyocyte toxicity. The pH-sensitive motif, that is, a tertiary amine trigger, is needed in these structures to initiate drug release into the tumor microenvironment and not in off-target regions that are highly buffered (such as cardiac tissues). We explain the fact that PCPY–cDOX enters into the cytosol of cardiac myocytes in its intact form because the cardiac microenvironment is not acidic. As a result, the conjugated system escapes the endosomal–lysosomal pathway to activate drug release. On the other hand, in the tumor microenvironment, DOX is cleaved off from this system as a function of tumor pH, which is acidic, thereby showing substantial toxicity to cancer cells.

Cancer Cell Uptake and Cytotoxicity Studies of Conjugated DOX–NCs (PCPY–cDOX Systems).

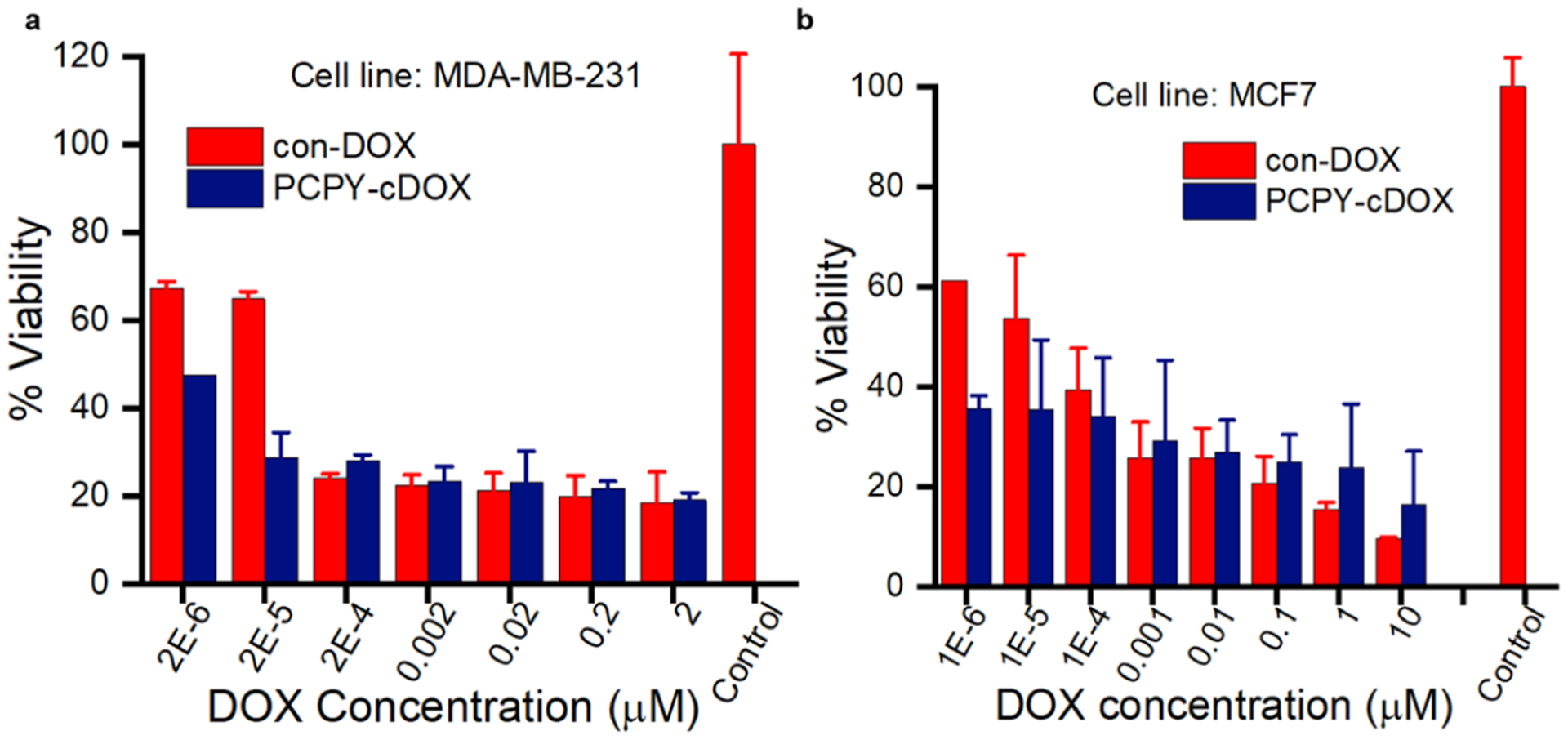

As PCPY–cDOX (6) showed an extended release of DOX under cell-free acidic microenvironment conditions and the encapsulated systems showed increased cardiotoxicity, for in vitro validation, we, therefore, set out to investigate the effect of PCPY–cDOX on the proliferation of a triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line, that is, MDA-MB-231 and an ER+ cell line, that is, MCF7 using the MTS assay. We observed that at equivalent concentrations of DOX, PCPY–cDOX showed higher cell mortality (drug dose varied from 2 to 2 × 10−6 μM) compared to the free drug (Figure 10). The higher cytotoxic effect may be attributed to a slower rate of release of DOX from the conjugated system even at the endosomal–lysosomal pH. The inherent nontoxicity of the polymer itself up to 10 mg/mL has already been reported by us earlier.27

Figure 10.

Cell viability of drug-bound NPs derived from PCPY–cDOX and con-DOX (free DOX) on (a) MDA-MB-231 cells and (b) MCF7 cells (n = 3).

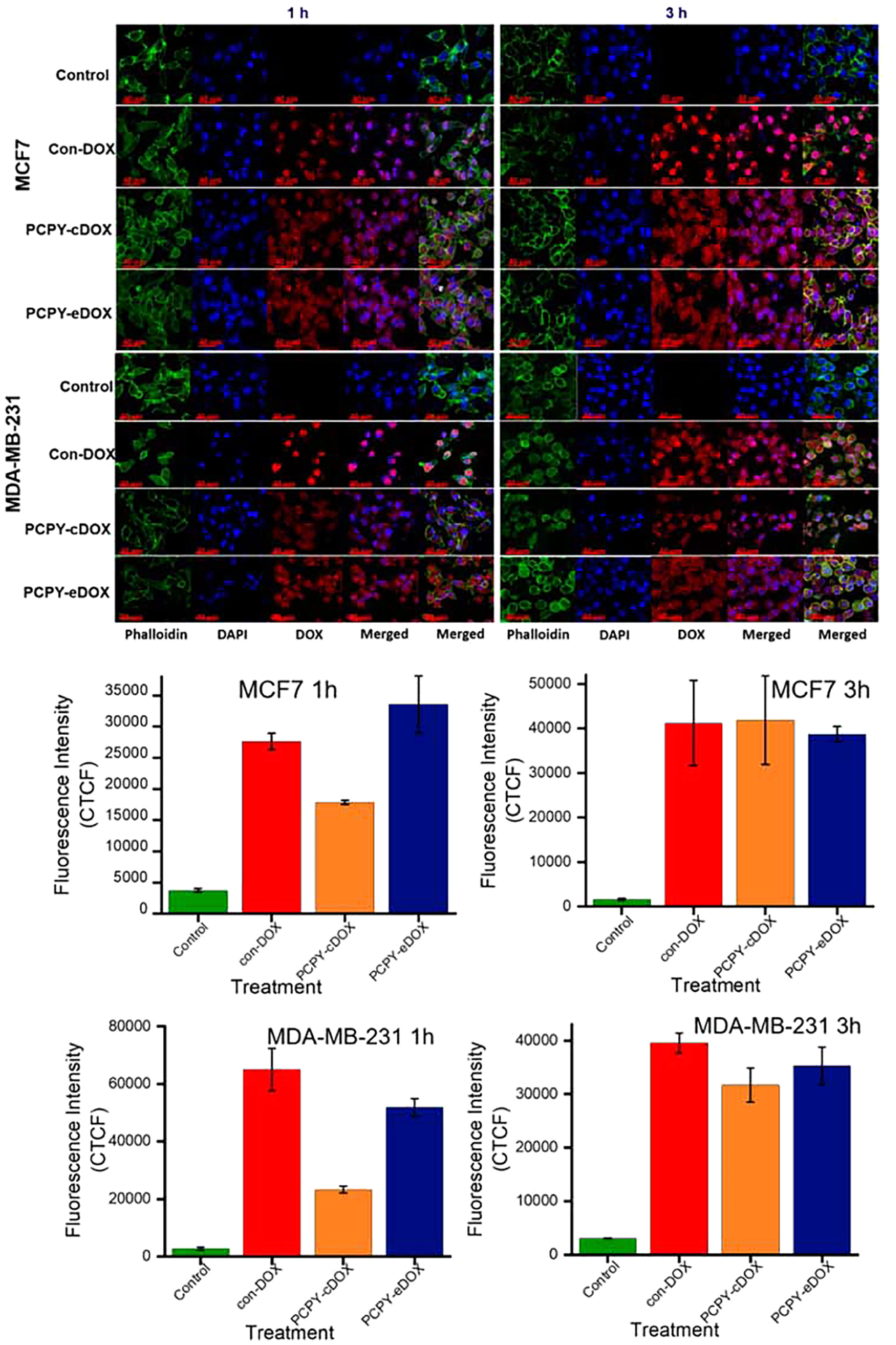

To study the cellular uptake and internalization of the NCs derived from PCPY–cDOX, we used monolayer cultures of MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with the nanocarrier suspension for different time points, that is, 1 and 3 h. The cells were imaged using confocal fluorescence microscopy postincubation. We observed a time-dependent uptake of NCs for both the cell lines (Figure 11). We also observed drug-mediated cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells when they were exposed to PCPY–cDOX systems. Because of the mild surface cationic charge, it is not unlikely that these NCs might bypass the endocytotic pathway and activate in the low pH microenvironment of early and late endosomes. In such an event, we envision that the observed cytotoxicity for PCPY–cDOX might be due to the drug release from PCPY–cDOX under generalized microenvironmental acidification brought about by highly glycolytic variants of cancer cells. Subsequently, released DOX reached into the nucleus and induced cell mortality, causing leakage of the nuclear substances into the cytoplasm (see Supporting Information, Figure S8).

Figure 11.

Confocal fluorescence microscopic images of monolayer culture of (top panel) MCF7 cells and (lower panel) MDA-MB-231 cells showing cellular uptake of different samples at 1 and 3 h. Bottom panel shows the corresponding CTCF analysis for the images.

To investigate whether PCPY–cDOX could penetrate through the 3D tumor microenvironment to transport therapeutic concentrations of DOX intracellularly, we established spheroid cultures of MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells, which were treated them with DOX-loaded NCs (PCPY–cDOX). As shown in Figure 12, we observed the presence of DOX in the spheroid microenvironment of both cell lines, indicating the diffusion of NCs loaded with drug inside the tumor tissue. In the absence of any targeting ligand as that of our system, such level of penetration is mostly due to the mild, surface cationic charge of the polymer assembly.

Figure 12.

Spheroid cultures of (top panel) MDA-MB-231 cells and (bottom panel) MCF7 cells showing the internalization of drug-conjugated NCs derived from PCPY–cDOX.

DISCUSSION

The nanocarrier formulation of DOX, such as Doxil, where the drug has been encapsulated within a liposomal system, has shown enhanced accumulation of the drug in the tumor microenvironment, mostly mediated by the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect.44 However, liposomal constructs suffer from several fundamental disadvantages such as a drug carrier in terms of systemic stability and premature release of the encapsulated content. Although cardiac toxicities have been extensively controlled when using liposomal DOX formulation, compared to the free drug, it is not entirely abrogated. Dose-limiting toxicity is still an issue for both liposomal and conventional DOX formulations. Besides, CARPA and hand-and-foot syndrome is also a set of toxicities associated with Doxil infusion. To enhance control over drug release from the delivery systems, more stable polymeric NCs and drug conjugates have been developed for DOX, a few of which are in clinical trials. Preclinical studies almost exclusively showed reduced accumulation of NCs (with or without DOX) in cardiac tissues. Tumor heterogeneity is a significant problem that does not necessarily guarantee the success of nanotherapy that solely depends on the EPR effect. Hence, to gain additional control over tumor accumulation, engineered NPs, particularly, those with environment-responsive modalities, have been designed, which substantially improve targeted activation and accumulation of the drug payload only in a tumor-cell specific manner. These systems act by exhibiting structural or conformational changes in the carrier-forming macromolecular units in response to a cellular or an extracellular stimulus of chemical, biochemical, or physical origin. These stimuli result in the release of drugs only within a specific pathological environment, sparing other physiological compartments from the adverse effects of the drug. Several solid tumors such as TNBC and pancreatic cancer cells show the Warburg effect, leading to the microenvironmental acidification associated with tumor hypoxia. Therefore, an exclusive pathological signature is set across the tumor tissue that can be harnessed for localized delivery of a chemotherapeutic payload released from pH-sensitive NCs. Although a vast arsenal of such nanosystems, either polymeric, liposomal, or micellar origin, have been reported following such delivery strategy, the fate and mechanism of DOX-loaded, stimuli-responsive carriers in cardiac myocytes have not been systematically explored. Therefore, our broader objective in this work was to identify how the carrier architecture and how DOX is associated with the carrier affect the disposition of the drug within cardiac myocytes.

First, we screened two types of pH-sensing carrier candidates, that is, block copolymers which sense pH drop that persists across the extracellular compartment of tumor tissues (pH 6.5–5.5, PCPY systems) and those which register the intracellular pH status that exists across the endosomal–lysosomal compartment (pH 5.5–pH 4.5, PCDB-systems). In both systems, DOX was physically encapsulated within the carriers (PCPY–eDOX and PCDB–eDOX) in the form of NPs. As noncovalent encapsulation, in many instances, yields suboptimal drug loading and burst release, we also designed a pH-responsive, chemically conjugated DOX carrier using a PCPY motif, leading to PCPY–cDOX systems. In these constructs, DOX was conjugated through a “conditionally unstable amide” linkage within a tertiary amine. To design these conjugates, we have devised a facile route to chemically attach DOX with the amphiphilic polymer backbone. We observed that such a conjugation technique not only improved DOX loading within the nanocarrier and rendered the construct sensitive to extra-/intracellular pH drop but also controlled DOX release in a pH-sensitive pattern. Mechanistically, we hypothesize that the presence of carbonyl carbon of the amide group in the vicinity of the tertiary amine will decrease the local pH of the molecular microenvironment of the carbonyl carbon, driving the liberation of DOX from the polymer scaffold (Supporting Information, Scheme S3). Thus, a parallel hypothesis of this work was to prove which type of DOX encapsulation technique, that is, covalent or noncovalent, shows a higher influence on cardiac myocytes in terms of their cellular and biochemical functions. For this reason, we designed two types of nanocarrier architectures of DOX, intending to tease out the cellular pathways through which DOX-conjugated or DOX-encapsulated systems trigger cardiotoxicity.

In the present study, we used cultured primary cardiomyocytes to study the cardiotoxicity of DOX. In earlier studies, using neonatal cardiomyocytes, we recapitulated and established the cellular toxicity associated with DOX. The studies showed an impairment of the autophagic degradation process and mitochondrial dysfunction.15 Therefore, we considered cardiomyocytes for this study and determined the toxicity of both encapsulated and conjugated DOX-loaded NCs. We also monitored their subcellular localization, cytotoxicity, and effect on cellular signaling. We observed that the noncovalently encapsulated DOX–NCs showed a similar level of nuclear localization, as observed with free DOX, suggesting premature drug release from the NCs within the endosomal–lysosomal pathways for these systems in cardiomyocytes.

In contrast, covalently conjugated DOX-loaded NCs (PCPY–cDOX) at several different doses applied to cardiomyocytes did not release free DOX from the NCs and escaped the lysosomal localization. In addition to conjugation chemistry, where DOX is connected to the polymer backbone through amide coupling, the surface charge of these carriers (10.35 mV) is the most likely driver for these observations. Important to note is that despite the cationic surface charge, these NCs did not show adverse effects on cardiomyocyte viability; however, they were found to have detrimental effects on cancer cells. Though these studies provide an effective way to kill cancer cells without affecting the cardiac cells, future studies are required to test the efficacy, infusion reactions, and cardiotoxicity of the conjugated DOX-NCs in an in vivo setting.

Our drug-release studies showed that enhanced DOX release from the NPs occurs at pH 5.5 or below compared to the release at pH 7.4 (Figure 4). We attempted to explain this disparity mechanistically in terms of pKa values for the two amines used in PCPY and PCDB systems. These amines are 2-pyrrolidine-1-yl-ethyl-amine, PY, and N,N′-dibutylethylenediamine, DB, with pKa values of 5.4 and 4.0, respectively. Therefore, at pH 5.5, while 44% of PY will be protonated, only 3% of DB groups will have protonation. At pH 4.5, 89% of PY and 24% of DB will be protonated. Accordingly, we observed a more pronounced DOX release from the PCPY NPs than from the PCDB counterparts at pH 5.5 and 4.5. As the pKa of DB is less than that of PY, a more reduced pH (4.5 compared to 5.5 for PY, see Figure 4a,b) is required to achieve a substantial amount of DOX release from these NPs. Based on these observations, we propose a possible DOX release mechanism under a reduced pH involving general acid-catalysis, as presented in the Supporting Information, Scheme S3. We also showed that within the timeframe of studies, the polycarbonate backbone does not reduce the average molecular weight (Supporting Information, Figure S9) at pH 7.4 or at <5.0, indicating that such acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of DOX is the prevalent mechanism of degradation that causes main chain breakdown. Of note, this mechanism is valid only for an acidic microenvironment that is present in the tumor microenvironment or within the endo–lysosomal pathways.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we present here that DOX-conjugated pH-responsive PEG-b-PC copolymers (PEG–PC) abrogates cardiotoxicity without compromising the anticancer efficacy of DOX. Moreover, we also demonstrated that drug molecules, when physically encapsulated inside PEG–PC NCs, show a premature release of the drug into the cytosol of cardiomyocytes. Analogous to earlier work with different cell lines,27 we also observed that encapsulated DOX–NCs initially localized within the late endosome–lysosome of cardiomyocytes, with subsequent release of free DOX in response to the acidic pH of the lysosome. The free DOX ultimately diffuses via the cytoplasm into the cell nuclei. The results obtained from this study indicated that the encapsulated DOX–NCs were most likely being taken up by cardiomyocytes via the endocytic pathway and showed pH-sensitive drug release. Interestingly, the conjugated DOX–NCs had a higher drug loading capacity, mildly positive zeta potential, and displayed a higher level of bioavailability, all of which led to a lack of cardiomyocyte toxicity triggered by this system, as free DOX was not released in the late endosome–lysosome compartment of cardiomyocytes. From these results, the DOX-conjugated pH-responsive PEG–PC block copolymers appear to be effective chemotherapy with an enhanced therapeutic efficacy devoid of cardiomyocyte toxicity for cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Scott Payne and Jayma Moore for TEM imaging. The authors also acknowledge Dr. Pawel Borowicz for his help with confocal microscopy. They would like to thank Prof. Dr. Rainer Haag and Dr. Magda Ferraro, Freie Universitat, Berlin, Germany, for support with chromatographic facility. The Table of Content image was created with BioRender.com.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, with National Institutes of Health grants: R01 HL145753, R01 HL145753-01S1, P20GM121307, and R00 HL122354 to M.S.B.; LSUHSC-S Feist-Weiller Cancer Center IDEA Grant to M.S.B.; LSUHSC-S Malcolm Feist Cardiovascular Postdoctoral Fellowship to C.S.A.; AHA Postdoctoral Fellowship to C.S.A. and S.A.; and LSUHSC-S Malcolm Feist Predoctoral Fellowship to R.A. Support for the work was received from NIH grant number 1 P20 GM109024 (to M.Q.) from the National Institute of General Medicine (NIGMS). Synthetic part of this research was supported by NSF grant no. IIA-1355466 from the North Dakota Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR through the Center for Sustainable Materials Science). Partial TEM material is based upon work supported by the NSF under grant no. 0923354. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PC

poly(carbonate)

- con-DOX

conventional doxorubicin

- NP

nanoparticle

- NC

nanocarrier

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00963.

IR and 1H and 13CNMR spectra, cytotoxicity analysis, and confocal microscopic images (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00963

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Chowdhury S. Abdullah, Department of Pathology and Translational Pathobiology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, Shreveport, Louisiana 71103, United States.

Priyanka Ray, Department of Coatings and Polymeric Materials, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58108, United States;.

Shafiul Alam, Department of Pathology and Translational Pathobiology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, Shreveport, Louisiana 71103, United States.

Narendra Kale, Department of Coatings and Polymeric Materials, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58108, United States.

Richa Aishwarya, Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, Shreveport, Louisiana 71103, United States.

Mahboob Morshed, Department of Pathology and Translational Pathobiology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, Shreveport, Louisiana 71103, United States.

Debasmita Dutta, Department of Coatings and Polymeric Materials, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58108, United States.

Cathleen Hudziak, Institute of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Freie Universität Berlin, 14195 Berlin, Germany.

Sushanta K. Banerjee, Cancer Research Unit, VA Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri 64128, United States; Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas 66160, United States;.

Sanku Mallik, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58108, United States;.

Snigdha Banerjee, Cancer Research Unit, VA Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri 64128, United States; Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas 66160, United States.

Md. Shenuarin Bhuiyan, Department of Pathology and Translational Pathobiology and Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, Shreveport, Louisiana 71103, United States;.

Mohiuddin Quadir, Department of Coatings and Polymeric Materials, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58108, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Thorn CF; Oshiro C; Marsh S; Hernandez-Boussard T; McLeod H; Klein TE; Altman RB Doxorubicin pathways: pharmacodynamics and adverse effects. Pharmacogenetics Genom. 2011, 21, 440–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Singal PK; Iliskovic N Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med 1998, 339, 900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Singal P; Li T; Kumar D; Danelisen I; Iliskovic N Adriamycin-induced heart failure: mechanism and modulation. Mol. Cell. Biochem 2000, 207, 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Middleman E; Luce J; Frei E 3rd Clinical trials with adriamycin. Cancer 1971, 28, 844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Colombo A; Cipolla C; Beggiato M; Cardinale D Cardiac toxicity of anticancer agents. Curr. Cardiol. Rep 2013, 15, 362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lipshultz SE; Miller TL; Scully RE; Lipsitz SR; Rifai N; Silverman LB; Colan SD; Neuberg DS; Dahlberg SE; Henkel JM; Asselin BL; Athale UH; Clavell LA; Laverdiere C; Michon B; Schorin MA; Sallan SE Changes in cardiac biomarkers during doxorubicin treatment of pediatric patients with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: associations with long-term echocardiographic outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol 2012, 30, 1042–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lipshultz SE; Scully RE; Lipsitz SR; Sallan SE; Silverman LB; Miller TL; Barry EV; Asselin BL; Athale U; Clavell LA; Larsen E; Moghrabi A; Samson Y; Michon B; Schorin MA; Cohen HJ; Neuberg DS; Orav EJ; Colan SD Assessment of dexrazoxane as a cardioprotectant in doxorubicin-treated children with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: long-term follow-up of a prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 950–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Li DL; Hill JA Cardiomyocyte autophagy and cancer chemotherapy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 2014, 71, 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Damiani RM; Moura DJ; Viau CM; Caceres RA; Henriques JAP; Saffi J Pathways of cardiac toxicity: comparison between chemotherapeutic drugs doxorubicin and mitoxantrone. Arch. Toxicol 2016, 90, 2063–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Chatterjee K; Zhang J; Honbo N; Karliner JS Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 2010, 115, 155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Dikmen G; Genç L; Güney G Advantage and disadvantage in drug delivery systems. J. Mater. Sci. Eng 2011, 5, 468. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ichikawa Y; Ghanefar M; Bayeva M; Wu R; Khechaduri A; Prasad SVN; Naik TJ; Ardehali H; Ardehali H Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin is mediated through mitochondrial iron accumulation. J. Clin. Invest 2014, 124, 617–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sawyer DB Anthracyclines and heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med 2013, 368, 1154–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Šimuånek T; Stérba M; Popelová O; Adamcová M; Hrdina R; Gersl V Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: overview of studies examining the roles of oxidative stress and free cellular iron. Pharmacol. Rep 2009, 61, 154–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Abdullah CS; Alam S; Aishwarya R; Miriyala S; Bhuiyan MAN; Panchatcharam M; Pattillo CB; Orr AW; Sadoshima J; Hill JA; Bhuiyan MS Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy associated with inhibition of autophagic degradation process and defects in mitochondrial respiration. Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sanders DP; Fukushima K; Coady DJ; Nelson A; Fujiwara M; Yasumoto M; Hedrick JL A Simple and Efficient Synthesis of Functionalized Cyclic Carbonate Monomers Using a Versatile Pentafluorophenyl Ester Intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 14724–14726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ray P; Confeld M; Borowicz P; Wang T; Mallik S; Quadir M PEG-b-poly (carbonate)-derived nanocarrier platform with pH-responsive properties for pancreatic cancer combination therapy. Colloids Surf., B 2019, 174, 126–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ray P; Nair G; Ghosh A; Banerjee S; Golovko MY; Banerjee SK; Reindl KM; Mallik S; Quadir M Microenvironment-sensing, nanocarrier-mediated delivery of combination chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2019, 13, 407–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chitkara D; Mittal A; Behrman SW; Kumar N; Mahato RI Self-Assembling, Amphiphilic Polymer–Gemcitabine Conjugate Shows Enhanced Antitumor Efficacy Against Human Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 24, 1161–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Alam S; Abdullah CS; Aishwarya R; Miriyala S; Panchatcharam M; Peretik JM; Orr AW; James J; Robbins J; Bhuiyan MS Aberrant Mitochondrial Fission Is Maladaptive in Desmin Mutation-Induced Cardiac Proteotoxicity. J. Am. Heart Assoc 2018, 7, No. e009289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Alam S; Abdullah CS; Aishwarya R; Orr AW; Traylor J; Miriyala S; Panchatcharam M; Pattillo CB; Bhuiyan MS Sigmar1 regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced C/EBP-homologous protein expression in cardiomyocytes. Biosci. Rep 2017, 37, BSR20170898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bhuiyan MS; Gulick J; Osinska H; Gupta M; Robbins J Determination of the critical residues responsible for cardiac myosin binding protein C’s interactions. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 2012, 53, 838–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Park SY; Jung E; Kim JS; Chi S-G; Lee MH Cancer-Specific hNQO1-Responsive Biocompatible Naphthalimides Providing a Rapid Fluorescent Turn-On with an Enhanced Enzyme Affinity. Sensors 2020, 20, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Burgess A; Vigneron S; Brioudes E; Labbé J-C; Lorca T; Castro A Loss of human Greatwall results in G2 arrest and multiple mitotic defects due to deregulation of the cyclin B-Cdc2/PP2A balance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2010, 107, 12564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Gavet O; Pines J Progressive activation of CyclinB1-Cdk1 coordinates entry to mitosis. Dev. Cell 2010, 18, 533–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ohkuma S; Poole B Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1978, 75, 3327–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ray P; Confeld M; Borowicz P; Wang T; Mallik S; Quadir M PEG-b-poly (carbonate)-derived nanocarrier platform with pH-responsive properties for pancreatic cancer combination therapy. Colloids Surf., B 2018, 174, 126–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Li Y; Zhai Y; Liu W; Zhang K; Liu J; Shi J; Zhang Z Ultrasmall nanostructured drug based pH-sensitive liposome for effective treatment of drug-resistant tumor. J. Nanobiotechnol 2019, 17, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Yadav AK; Mishra P; Jain S; Mishra P; Mishra AK; Agrawal GP Preparation and characterization of HA-PEG-PCL intelligent core-corona nanoparticles for delivery of doxorubicin. J. Drug Target 2008, 16, 464–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Nagarajan R Molecular Packing Parameter and Surfactant Self-Assembly: The Neglected Role of the Surfactant Tail. Langmuir 2002, 18, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Discher DE; Ortiz V; Srinivas G; Klein ML; Kim Y; Christian D; Cai S; Photos P; Ahmed F Emerging Applications of Polymersomes in Delivery: from Molecular Dynamics to Shrinkage of Tumors. Prog. Polym. Sci 2007, 32, 838–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Doroshow JH Role of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical formation in the killing of Ehrlich tumor cells by anticancer quinones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1986, 83, 4514–4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Tewey K; Rowe T; Yang L; Halligan B; Liu L Adriamycin-induced DNA damage mediated by mammalian DNA topoisomerase II. Science 1984, 226, 466–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kato Y; Ozawa S; Miyamoto C; Maehata Y; Suzuki A; Maeda T; Baba Y Acidic extracellular microenvironment and cancer. Canc. Cell Int 2013, 13, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hu Y-B; Dammer EB; Ren R-J; Wang G The endosomallysosomal system: from acidification and cargo sorting to neuro-degeneration. Transl. Neurodegener 2015, 4, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Wang C; Wang Y; Li Y; Bodemann B; Zhao T; Ma X; Huang G; Hu Z; DeBerardinis RJ; White MA; Gao J A nanobuffer reporter library for fine-scale imaging and perturbation of endocytic organelles. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 8524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lee ES; Gao Z; Bae YH Recent progress in tumor pH targeting nanotechnology. J. Controlled Release 2008, 132, 164–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Chauhan VP; Jain RK Strategies for advancing cancer nanomedicine. Nat. Mater 2013, 12, 958–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ray P; Alhalhooly L; Ghosh A; Choi Y; Banerjee S; Mallik S; Banerjee S; Quadir M Size-Transformable, Multifunctional Nanoparticles from Hyperbranched Polymers for Environment-Specific Therapeutic Delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2019, 5, 1354–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ray P; Ferraro M; Haag R; Quadir M Dendritic Polyglycerol-Derived Nano-Architectures as Delivery Platforms of Gemcitabine for Pancreatic Cancer. Macromol. Biosci 2019, 19, 1900073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).McSweeney KM; Bozza WP; Alterovitz WL; Zhang B Transcriptomic profiling reveals p53 as a key regulator of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Cell Death Discovery 2019, 5, 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Quadir MA; Morton SW; Deng ZJ; Shopsowitz KE; Murphy RP; Epps TH 3rd; Hammond PT PEG-polypeptide block copolymers as pH-responsive endosome-solubilizing drug nanocarriers. Mol. Pharm 2014, 11, 2420–2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Majzoub RN; Wonder E; Ewert KK; Kotamraju VR; Teesalu T; Safinya CR Rab11 and Lysotracker Markers Reveal Correlation between Endosomal Pathways and Transfection Efficiency of Surface-Functionalized Cationic Liposome-DNA Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 6439–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Gordon AN; Fleagle JT; Guthrie D; Parkin DE; Gore ME; Lacave AJ Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J. Clin. Oncol 2001, 19, 3312–3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.