Abstract

Rotavirus type G5 is a primarily porcine pathogen that has caused frequent and widespread diarrhea in children in Brazil and in piglets elsewhere. Initial results on the rotavirus types circulating in diarrheic piglets in Brazil disclosed a high diversity of strains with distinct G types including G1, G4, G5, and G9 and the novelty of P[8], the predominant human P specificity type. Those results add strong evidence for the emergence of new strains through natural reassortment between rotaviruses of human and porcine origins.

Rotavirus type G5 strains are primarily porcine pathogens that have occasionally been recovered from horses, usually in combination with the P9[7] VP4 specificity type (16, 21). Nevertheless, recent studies have demonstrated that they are common human pathogens in Brazil, generally in combination with the P1A[8] specificity type (9, 13). Those findings have suggested that the human strains might have arisen by natural reassortment among rotavirus strains of human and animal origins (8). However, since characterization of rotaviruses isolated from piglets or horses has not been reported in Brazil yet, it is difficult to speculate over this matter. Knowledge of the distribution of the G and P types circulating in the porcine population of Brazil might bring new insights to this hypothesis. To address this issue, we analyzed rotavirus isolates recovered from piglets in the state of Paraná, Brazil, and verified whether G5 rotavirus strains circulate among this species in the country and, therefore, provide an additional clue to the occurrence of natural reassortment between human and porcine strains.

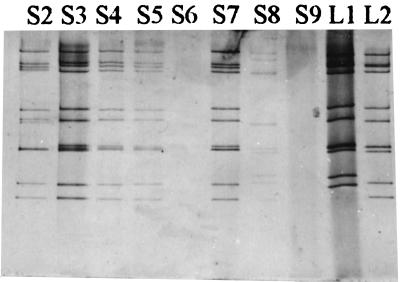

Stool samples were collected from seven different pig farms located in four counties in southwest Paraná, Brazil. The specimens were obtained from piglets 21 to 35 days-old with diarrhea between March 1991 and March 1992. The piglets were raised in confinement without any contact with animals of other species. Virus double-stranded RNA was extracted from stool specimens and examined by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by standard silver staining. The electropherotypes of the rotavirus-positive specimens were compared to the long and short electrophoretic patterns of group A human strains. PCR amplifications for the identification of the G and P types of the isolates were performed in two steps as described originally, with some modifications (6, 10, 14, 15). Six stool specimens were positive for rotavirus RNA by PAGE (Table 1). Four samples exhibited RNA profiles consistent with group A rotavirus (Fig. 1). Two samples, S2 and S8, exhibited atypical profiles and were further analyzed by PCR for group B and C rotavirus by previously described techniques (7).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of rotavirus types among porcine samples in Paraná, Brazil

| Sample | Farm | Date (mo/yr) | G genotype | P genotype | PAGE result | Group Ba | Group Cb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | A | 3/91 | Negc | Neg | Neg | NDd | ND |

| S2 | B | 3/91 | G4 | P[6, Gott] | Atypical | Neg | Neg |

| S3 | A | 3/91 | G4 | P[6, Gott] | Group A | ND | ND |

| S4 | C | 7/91 | G9 | P[6, Gott] | Group A | ND | ND |

| S5 | C | 7/91 | G9 | P[6, Gott] | Group A | ND | ND |

| S6 | D | 8/91 | Neg | Neg | Neg | ND | ND |

| S7 | E | 8/91 | G1 | P[6, Gott] | Group A | ND | ND |

| S8 | F | 10/91 | G1-G5 | P[8] | Atypical | Neg | Neg |

| S9 | G | 2/92 | Neg | Neg | Neg | ND | ND |

| S10 | D | 8/91 | Neg | Neg | Neg | ND | ND |

FIG. 1.

PAGE of eight porcine fecal specimens obtained in Paraná, Brazil. L1 and L2 are reference group A human rotavirus strains with short and long electropherotypes, respectively.

Despite the limited number of samples analyzed, the PCR results revealed a high diversity of G types (Table 1). The isolates presented types G4 (two), G9 (two), and G1 (one); the sixth specimen presented a mixture of types G1 and G5. The VP4 specificity was less diverse, with five of the six isolates presenting one of the most common porcine types, P[6, Gott] (Table 1) (16, 21, 24). We have added the designation “Gott” for Gottfried-like, because our PCR methodology clearly differentiates the P[6] genotype into two subtypes, P[6, M37] and P[6, Gott], which correlate with the serotypes P2A (M37-like) and P2B (Gottfried-like), respectively (14, 16). The main purpose of PCR typing is to predict the antigenic specificity of the strains. Consequently, specification of the subtype is relevant and should be accommodated in the current genotype nomenclature until a definitive classification is adopted.

Three isolates displayed unconventional combinations of G and P types, showing the common porcine P[6, Gott] specificity type associated with types G1 and G9, which are G types usually described for human isolates, whereas two isolates presented the typical porcine P[6, Gott] G4 types. It was interesting to note that one of those typical isolates, S2, presented an atypical group A electropherotype that resembled the profile observed for group C rotaviruses (Fig. 1). However, lack of recognition by group C-specific generic primers indicated that the RNA profile indeed represented the group A rotavirus typed, either as a strain with rearranged segment 7 or, most likely, as a mixture of two G4 P[6, Gott] strains.

Type G9 rotavirus was identified in specimens S4 and S5 collected in July of 1991 from two piglets on farm C (Table 1). They presented the same P specificity type and identical electropherotypes and probably represent a single strain that circulated in the winter of 1991 on that farm. The G9 specificity has been associated with infections usually in humans and seldom in animals (16). It was initially recognized as a new serotype in the United States, where it caused approximately 9.2% of the cases of infant rotaviral disease studied at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pa., in 1983–1984 (3). It was also found sporadically in children with diarrhea in Japan and Thailand and very frequently in India, though mostly in children with asymptomatic neonatal infections (4, 18, 23). In Brazil, rotavirus type G9 has been reported only once, from a child, during a vaccine trial conducted in the northern state of Pará (17). Yet, after a silent decade in Philadelphia, the incidence of type G9 strains achieved an astonishing 56% of the rotavirus-associated diarrheal cases seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in the 1995-to-1996 season (H. F. Clark, personal communication), attesting to the typical and well-known periodicity of group A rotavirus serotypes (11, 20). The high population density and heterogeneity of major urban centers should favor transmission of newly adapted human strains (8). Thus, the explosive reappearance of type G9 rotavirus in Philadelphia might have resulted in its rapid spread to other geographic areas, as a few G9 strains were detected in the following season in the Midwest (20). It is of note, however, that the single porcine G9 virus described previously, the ISU-64 strain, had been isolated in Iowa, in the midwestern United States, in 1988 (19, 24). A second animal rotavirus of type G9 was identified in a lamb in Scotland (strain LRV2c) in 1995 (5). Hence, serotype G9 has circulated among humans and animals in the United States and elsewhere for many years, a fact that extends the likelihood that interspecies transmissions may have occurred. Although to date, G9 has been a minor serotype in the causation of human diarrhea, the recent identification of rotavirus type G9 in association with human and porcine diarrhea in Brazil, in studies that analyzed only limited numbers of fecal specimens, clearly expands the geographic distribution and perhaps the significance of this rotavirus serotype in diarrheal disease.

Rotavirus type G1 is widespread and has been the most prevalent G type, causing diarrhea in children everywhere in the last two decades (11, 16). Nevertheless, porcine rotavirus strains belonging to serotype G1 have been described previously for Argentina and Venezuela (1, 2). The current discovery of type G1 in Brazil suggests that G1 strains might also be frequent porcine pathogens in South America.

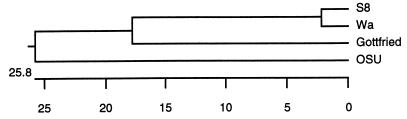

One specimen, S8, presented a number of interesting characteristics. In addition to G1, it contained a G5 rotavirus, demonstrating a case of mixed infection. It displayed an atypical electropherotype, probably due to the mixture of two strains, although only 11 segments were discernible by PAGE (Fig. 1). A single P[8] type that was confirmed by sequence analysis was identified in S8, suggesting the presence of a P[8] G1 strain and a P[8] G5 strain in the fecal specimen. Comparison of partial gene 4 sequence of the S8 strain with the partial sequences of several rotavirus strains revealed a low similarity between S8 and known porcine P types: only 52.7% similarity to the OSU strain and 61.2% similarity to the Gottfried strain. Nevertheless, the S8 sequence was 96% similar to the Wa sequence (12). A dendrogram based on their partial gene 4 sequences that clearly demonstrated the closer relation to gene 4 of Wa than to the porcine gene 4 was constructed (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of the partial gene 4 sequences of porcine rotavirus strains S8, Gottfried, and OSU and the human strain Wa. The cDNA generated in the reverse transcription-PCR amplification of a portion of gene 4 of the isolate S8 was sequenced (12), and a dendrogram was constructed by the Clustal method.

Rotavirus type P[8] is the most prevalent rotavirus P type affecting humans worldwide, usually in association with G1, G3, G4, or G9 (16). It was also the P type found most frequently associated with the G5 specificity type in rotaviruses recovered from Brazilian children with diarrhea during nationwide surveys (9, 13, 22). The finding of S8 strongly supports the notion that the human G5 strains had arisen by natural reassortment (8, 13).

S8 is the second animal rotavirus that has been shown to possess P[8] specificity. Previously, a rotavirus strain isolated in Scotland from a lamb (LRVc) was shown to have P[8] G9 specificity (5). Curiously, this strain was also found in a mixed infection with a P[11] G6 rotavirus strain. The finding of specimens, such as LRV and S8, containing mixtures of strains of conventional human and animal rotavirus types is strong evidence for the occurrence of both gene reassortment and interspecies transmission in nature. Those interspecies trades may facilitate the emergence of new rotavirus strains (8). Notwithstanding, the impact of such events in the natural history of rotaviruses is still to be determined.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the S8 isolate was deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF052449.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by CNPq, FINEP, FAPERJ, and FUJB, Brazil, and TWAS, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bellinzoni R C, Mattion N M, Matson D O, Blackhall J O, La Torre L, Scodeller E A, Urasawa S, Taniguchi K, Estes M K. Porcine rotaviruses antigenically related to human rotavirus serotype 1 and 2. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:633–636. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.633-636.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciarlet M, Liprandi F. Serological and genomic characterization of two porcine rotaviruses with serotype G1 specificity. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:269–272. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.269-272.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark H F, Hoshino Y, Bell L M, Groff J, Hess G, Bachman P, Offit P A. Rotavirus isolate WI61 representing a presumptive new human serotype. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1757–1762. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.9.1757-1762.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das B K, Gentsch J R, Cicirello H G, Woods P A, Gupta A, Ramachandran M, Kumar R, Bhan M K, Glass R I. Characterization of rotavirus strains from newborns in New Delhi, India. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;22:1820–1822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1820-1822.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald T A, Munoz M, Wood A R, Snodgrass D R. Serological and genomic characterization of group A rotavirus from lamb. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1541–1548. doi: 10.1007/BF01322528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentsch J R, Glass R I, Woods P, Gouvea V, Gorziglia M, Flores J, Das B K, Bhan M K. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1365-1373.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gouvea V, Allen J R, Glass R I, Fang Z-Y, Bremont M, Cohen J, McCrae M A, Saif L J, Sanarachatanant P, Caul E O. Detection of group B and C rotavirus by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:519–523. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.519-523.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouvea V, Brandtly M. Is rotavirus a population of reassortants? Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouvea V, de Castro L, Timenetsky M C, Greenberg H B, Santos N. Rotavirus serotype G5 associated with diarrhea in Brazilian children. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1408–1409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1408-1409.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouvea V, Glass R I, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark H F, Forrester B, Fang Z-Y. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.276-282.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouvea V, Ho M-S, Glass R I, Woods P, Forrester B, Robinson C, Ashley R, Ripenhoff-Talty M, Clark H F, Taniguchi K, Meddix E, McKellar B, Pickering L. Serotypes and electropherotypes of human rotavirus in USA: 1987–1989. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:362–367. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gouvea V, Lima R C C, Linhares R E, Clark H F, Nozawa C M, Santos N. Identification of two lineages (Wa-like and F45-like) within the major rotavirus genotype P[8] Virus Res, 1999;59:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouvea V, Santos N. Molecular epidemiology of rotavirus in Brazil: a model for the tropics? Virus Rev Res. 1997;2:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gouvea V, Santos N, Timenetsky M C. Identification of bovine and porcine rotavirus G types by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1338–1340. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1338-1340.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouvea V, Santos N, Timenetsky M C. VP4 typing of bovine and porcine rotaviruses by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1333–1337. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1333-1337.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoshino Y, Kapikian A Z. Classification of rotavirus VP4 and VP7 serotypes. Arch Virol. 1996;12(Suppl.):99–111. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linhares A C, Gabbay Y B, Mascarenhas J D P, de Freitas R B, Oliveira C S, Bellesi N, Monteiro T A F, Lainson Z L, Ramos F L P, Valente S A. Immunogenicity, safety and efficacy of tetravalent rhesus-human, reassortant rotavirus vaccine in Bélem, Brazil. Bull W H O. 1996;74:491–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagomi T, Ohshima A, Akatani K, Ikegami I, Katsushima N, Nakagomi O. Isolation and molecular characterization of a serotype 9 human rotavirus strain. Microbiol Immunol. 1990;34:77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul P S, Lyoo Y S, Andrews J J, Hill H T. Isolation of two new serotypes of porcine rotavirus from pigs with diarrhea. Arch Virol. 1988;100:139–143. doi: 10.1007/BF01310917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramachandran M, Gentsch J R, Parashar U D, Jin S, Woods P A, Holmes J L, Kirkwood C D, Bishop R F, Greenberg H B, Urasawa S, Gerna G, Coulson B S, Taniguchi K, Bresee J S, Glass R I The National Rotavirus Strain Surveillance System Collaborating Laboratories. Detection and characterization of novel rotavirus strains in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3223–3229. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3223-3229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saif L J, Rosen B, Parwani A. Animal rotaviruses. In: Kapikian A Z, editor. Viral infections of the gastrointestinal tract. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1994. pp. 279–367. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Timenetsky M C S T, Gouvea V, Santos N, Carmona R C C, Hoshino Y. A novel human rotavirus serotype with dual G5-G11 specificity. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1373–1378. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urasawa S, Hasegawa A, Urasawa T, Taniguchi K, Wakasugi F, Susuki H, Inouye S, Pongprot B, Supawadee J, Suprasert S, Rangsiyanond J, Tonusin S, Yamazi Y. Antigenic and genetic analyses of human rotavirus in Chiang Mai, Thailand: evidence for a close relationship between human and animal rotaviruses. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:227–234. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaberezhny A, Lyoo Y S, Paul P S. Prevalence of P types among porcine rotaviruses using subgenomic VP4 gene probes. Vet Microbiol. 1994;39:97–110. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]