Abstract

This Campbell systematic review examines the impact of interventions to reduce exclusion from school. School exclusion, also known as suspension in some countries, is a disciplinary sanction imposed by a responsible school authority, in reaction to students' misbehaviour. Exclusion entails the removal of pupils from regular teaching for a period during which they are not allowed to be present in the classroom (in‐school) or on school premises (out‐of‐school). In some extreme cases the student is not allowed to come back to the same school (expulsion). The review summarises findings from 37 reports covering nine different types of intervention. Most studies were from the USA, and the remainder from the UK.

Included studies evaluated school‐based interventions or school‐supported interventions to reduce the rates of exclusion. Interventions were implemented in mainstream schools and targeted school‐aged children from four to 18, irrespective of nationality or social background. Only randomised controlled trials are included.

The evidence base covers 37 studies. Thirty‐three studies were from the USA, three from the UK, and for one study the country was not clear.

School‐based interventions cause a small and significant drop in exclusion rates during the first six months after intervention (on average), but this effect is not sustained. Interventions seemed to be more effective at reducing some types of exclusion such as expulsion and in‐school exclusion.

Four intervention types – enhancement of academic skills, counselling, mentoring/monitoring, and skills training for teachers – had significant desirable effects on exclusion. However, the number of studies in each case is low, so this result needs to be treated with caution.

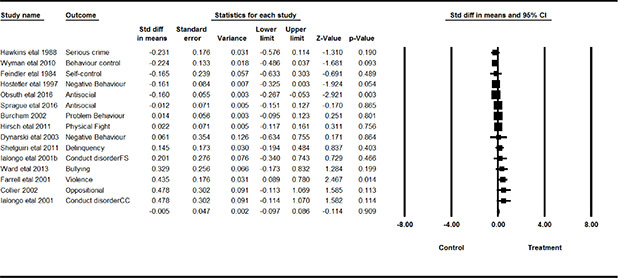

There is no impact of the interventions on antisocial behaviour.

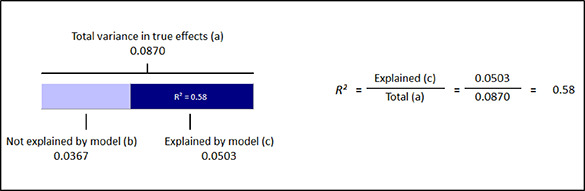

Variations in effect sizes are not explained by participants' characteristics, the theoretical basis of the interventions, or the quality of the intervention. Independent evaluator teams reported lower effect sizes than research teams who were also involved in the design and/or delivery of the intervention.

Plain language summary

Interventions can reduce school exclusion but the effect is temporary

Some interventions – enhancement of academic skills, counselling, mentoring/monitoring, and skills training for teachers – appear to have significant effects on exclusion.

The review in brief

Interventions to reduce school exclusion are intended to mitigate the adverse effects of this school sanction. Some approaches, namely those involving enhancement of academic skills, counselling, mentoring/monitoring and those targeting skills training for teachers, have a temporary effect in reducing exclusion. More evaluations are needed to identify the most effective types of intervention; and whether similar effects are also found in different countries.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review examines the impact of interventions to reduce exclusion from school. School exclusion, also known as suspension in some countries, is a disciplinary sanction imposed by a responsible school authority, in reaction to students’ misbehaviour. Exclusion entails the removal of pupils from regular teaching for a period during which they are not allowed to be present in the classroom (in‐school) or on school premises (out‐of‐school). In some extreme cases the student is not allowed to come back to the same school (expulsion). The review summarises findings from 37 reports covering nine different types of intervention. Most studies were from the USA, and the remainder from the UK.

What is this review about?

School exclusion is associated with undesirable effects on developmental outcomes. It increases the likelihood of poor academic performance, antisocial behavior, and poor employment prospects. This school sanction disproportionally affects males, ethnic minorities, those who come from disadvantaged economic backgrounds, and those with special educational needs.

This review assesses the effectiveness of programmes to reduce the prevalence of exclusion.

What are the main findings of this review?

What studies are included?

Included studies evaluated school‐based interventions or school‐supported interventions to reduce the rates of exclusion. Interventions were implemented in mainstream schools and targeted school‐aged children from four to 18, irrespective of nationality or social background. Only randomised controlled trials are included.

The evidence base covers 37 studies. Thirty‐three studies were from the USA, three from the UK, and for one study the country was not clear.

School‐based interventions cause a small and significant drop in exclusion rates during the first six months after intervention (on average), but this effect is not sustained. Interventions seemed to be more effective at reducing some types of exclusion such as expulsion and in‐school exclusion.

Four intervention types ‐ enhancement of academic skills, counselling, mentoring/ monitoring, and skills training for teachers – had significant desirable effects on exclusion. However, the number of studies in each case is low, so this result needs to be treated with caution.

There is no impact of the interventions on antisocial behaviour.

Variations in effect sizes are not explained by participants’ characteristics, the theoretical basis of the interventions, or the quality of the intervention. Independent evaluator teams reported lower effect sizes than research teams who were also involved in the design and/or delivery of the intervention.

What do the findings of this review mean?

School‐based interventions are effective at reducing school exclusion immediately after, and for a few months after, the intervention (6 months on average). Four interventions presented promising and significant results in reducing exclusion, that is, enhancement of academic skills, counselling, mentoring/monitoring, skills training for teachers. However, since the number of studies for each sub‐type of intervention was low, we suggest these results should be treated with caution.

Most of the studies come from the USA. Evaluations are needed from other countries in which exclusion is common. Further research should take advantage of the possibility of conducting cluster‐randomised controlled trials, whilst ensuring that the sample size is sufficiently large.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies published up to December 2015. This Campbell systematic review was published in January 2018.

Executive Summary/Abstract

BACKGROUND

Schools are important institutions of formal social control (Maimon, Antonaccio, & French, 2012). They are, apart from families, the primary social system in which individuals are socialised to follow specific codes of conduct. Violating these codes of conduct may result in some form of punishment. School punishment is normally accepted by families and students as a consequence of transgression, and in that sense school isoften the place where children are first introduced to discipline, justice, or injustice (Whitford & Levine‐Donnerstein, 2014).

A wide range of punishments may be used in schools, from verbal reprimands to more serious actions such as detention, fixed term exclusion or even permanent exclusion from the mainstream education system. It must be said that in some way, these school sanctions resemble the penal system and its array of alternatives to punish those that break the law.

School exclusion, also known as suspension in some countries, is defined as a disciplinary sanction imposed by a responsible school authority, in reaction to students’ misbehaviour. Exclusion entails the removal of pupils from regular teaching for a period during which they are not allowed to be present in the classroom or, in more serious cases, on school premises.Based on the previous definition, this review uses school exclusion and school suspension as synonyms, unless the contrary is explicitly stated.

Most of the available research has found that exclusion correlates with subsequent negative sequels on developmental outcomes. Exclusion or suspension of students is associated with failure within the academic curriculum, aggravated antisocial behaviour, and an increased likelihood of involvement with punitive social control institutions (i.e., the Juvenile Justice System). In the long‐term, opportunities for training and employment seem to be considerably reduced for those who have repeatedly been excluded. In addition to these negative correlated outcomes, previous evidence suggest that the exclusion of students involves a high economic cost for taxpayers and society.

Research from the last 20 years has concluded quite consistently that this disciplinary measure disproportionally targets males, ethnic minorities, those who come from disadvantaged economic backgrounds, and those presenting special educational needs. In other words, suspension affects the most vulnerable children in schools.

Different programmes have attempted to reduce the prevalence of exclusion. Although some of them have shown promising results, so far, no comprehensive systematic review has examined these programmes’ overall effectiveness.

OBJECTIVES

The main goal of the present research is to systematically examine the available evidence for the effectiveness of different types of school‐based interventions aimed at reducing disciplinary school exclusion. Secondary goals include comparing different approaches and identifying those that could potentially demonstrate larger and more significant effects.

The research questions underlying this project are as follows:

Do school‐based programmes reduce the use of exclusionary sanctions in schools?

Are some school‐based approaches more effective than others in reducing exclusionary sanctions?

Do participants’ characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity) affect the impact of school‐based programmes on exclusionary sanctions in schools?

Do characteristics of the interventions, implementation, and methodology affect the impact of school‐based programmes on exclusionary sanctions in schools?

SEARCH METHODS

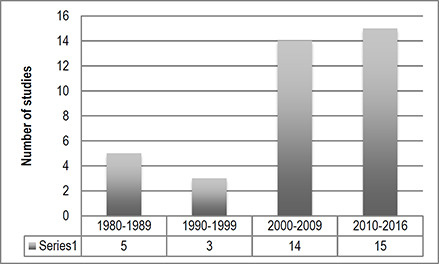

The authors conducted a comprehensive search to locate relevant studies reporting on the impact of school‐based interventions on exclusion from 1980 onwards. Twenty‐seven different databases were consulted, including databases that contained both published and unpublished literature. In addition, we contacted researchers in the field of school‐exclusion for further recommendations of relevant studies; we also assessed citation lists from previous systematic and narrative reviews and research reports. Searches were conducted from September 1 to December 1, 2015.

SELECTION CRITERIA

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for manuscripts were defined before we started our searches. To be eligible, studies needed to have: evaluated school‐based interventions or school‐supported interventions intended to reduce the rates of suspension; seen the interventions as an alternative to exclusion; targeted school‐aged children from four to 18 in mainstream schools irrespective of nationality or social background; and reported results of interventions delivered from 1980 onwards. In terms of methodological design, we included randomised controlled trialsonly, with at least one experimental group and onecontrol or placebo group.

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

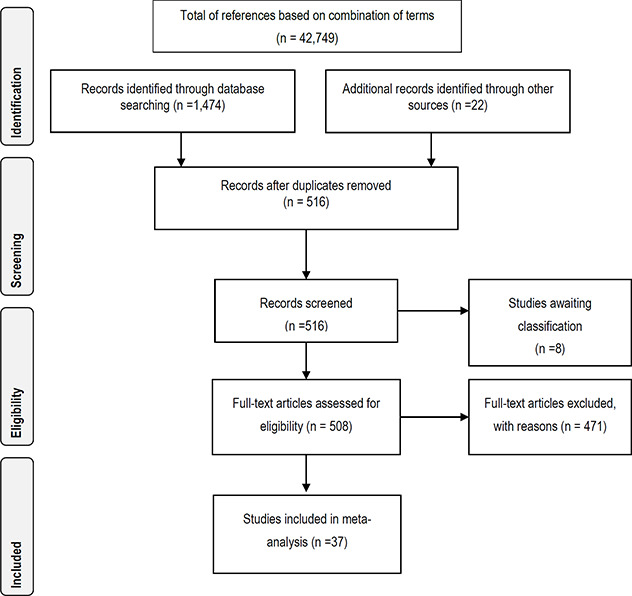

Initial searches produced a total of 42,749 references from 27 different electronic databases. After screening the title, abstract and key words, we kept 1,474 relevant hits. 22 additional manuscripts were identified through other sources (e.g., assessment of citation lists, contribution of authors). After removing duplicates, we ended up with a total of 517 manuscripts. Two independent coders evaluated each report, to determine inclusion or exclusion.

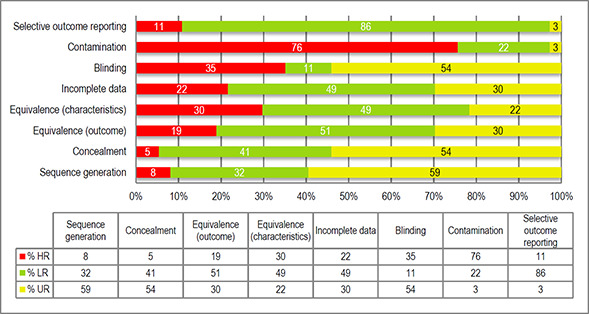

The second round of evaluation excluded 472 papers, with eight papers awaiting classification, and 37 studies kept for inclusion in meta‐analysis. Two independent evaluators assessed all the included manuscripts for risk of quality bias by using EPOC tool.

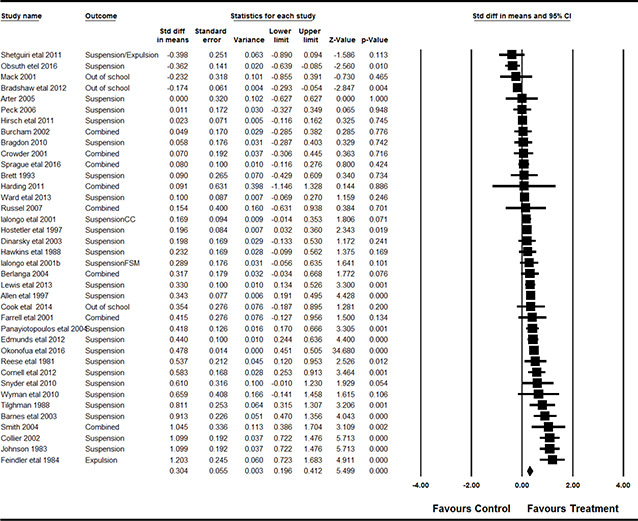

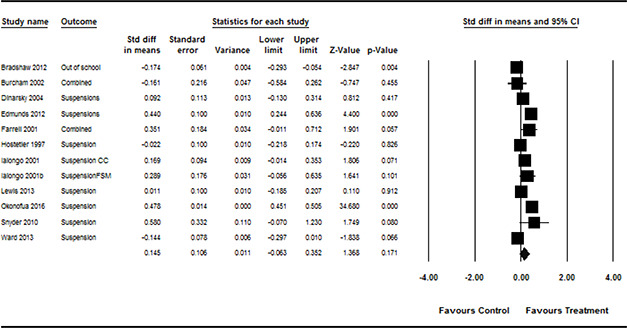

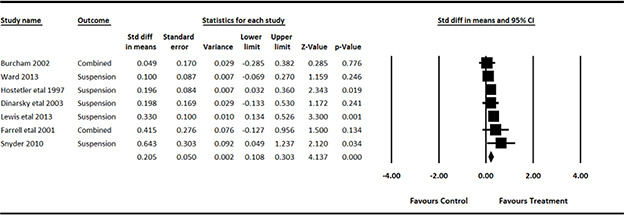

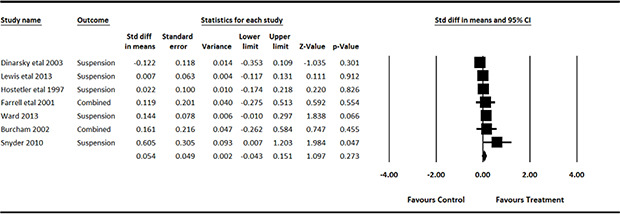

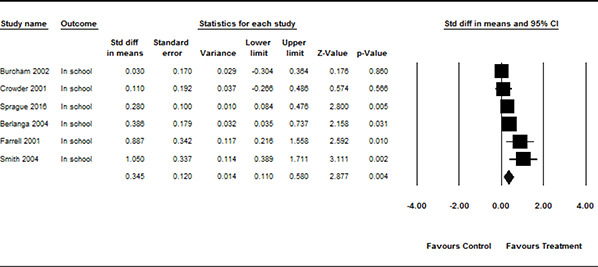

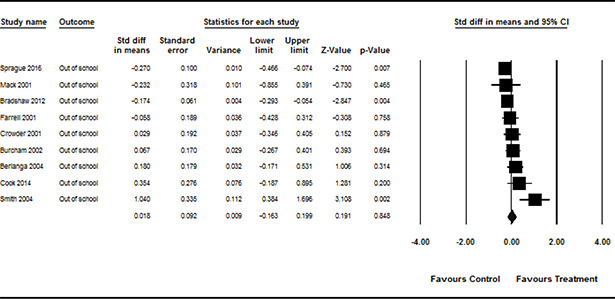

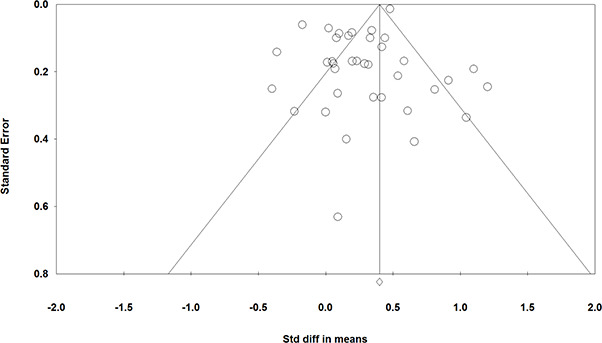

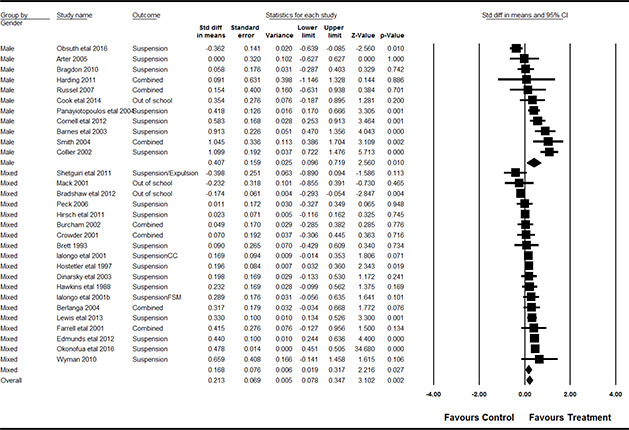

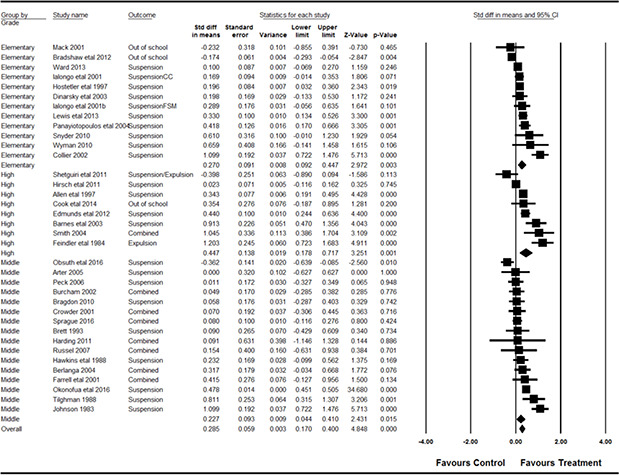

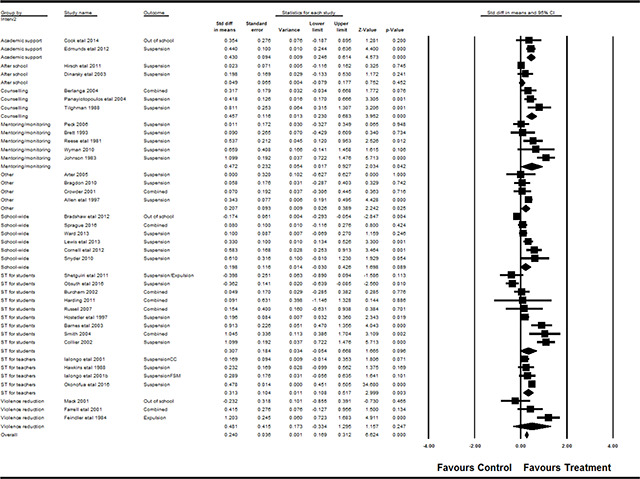

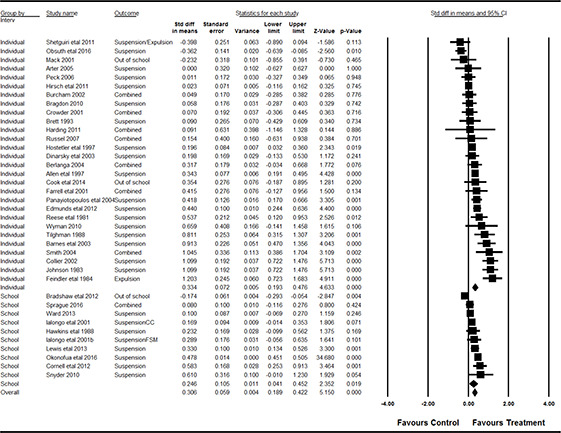

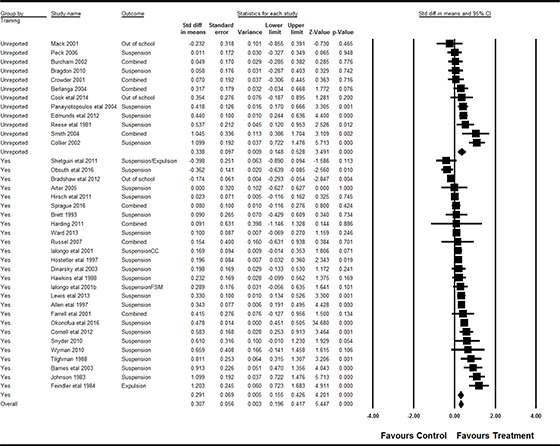

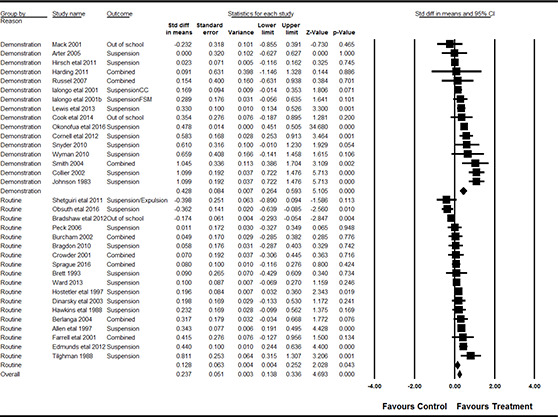

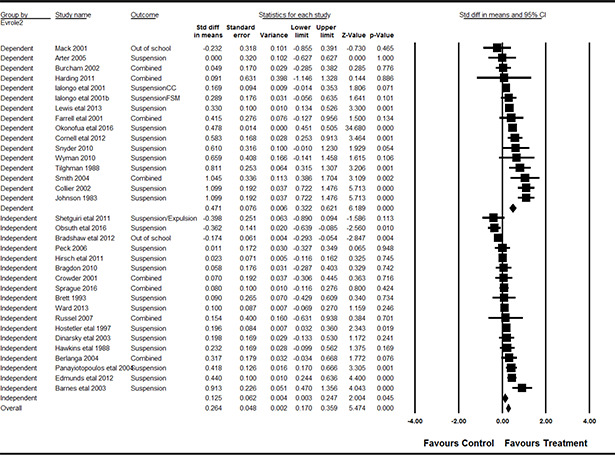

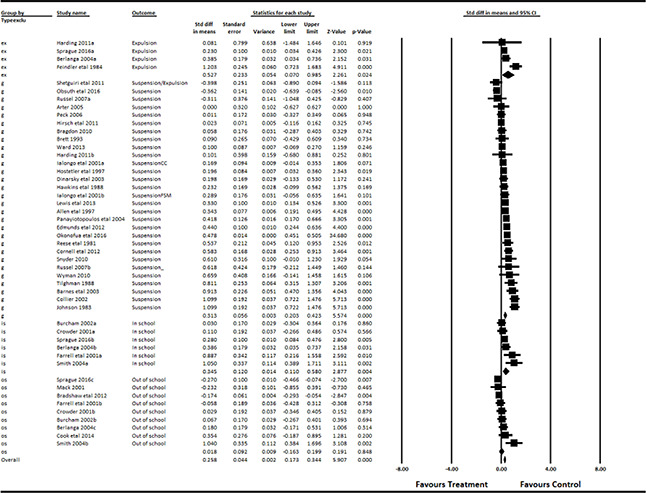

Due to the broad scope of our targeted programmes, meta‐analysis was conducted under a random‐effect model. We report the impact of the intervention using standardised differences of means, 95% confidence intervals along with the respective forest plots. Sub‐group analysis and meta‐regression were used for examining the impact of the programme. Funnel plots and Duval and Tweedie's trim‐and‐fill analysis were used to explore the effect of publication bias.

RESULTS

Based on our findings, interventions settled in school can produce a small and significant drop in exclusion rates (SMD=.30; 95% CI .20 to .41; p<.001). This means that those participating in interventions are less likely to be suspended than those allocated to control/placebo groups. These results are based on measures of impact collected immediately during the first six months after treatment (on average). When the impact was tested in the long‐term (i.e., 12 or more months after treatment), the effects of the interventions were not sustained. In fact, there was a substantive reduction in the impact of school‐based programmes (SMD=.15; 95%CI ‐.06 to .35), and it was no longer statistically significant.

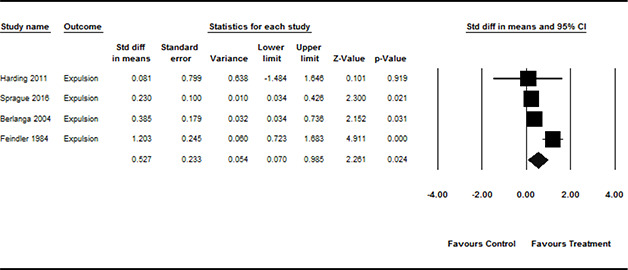

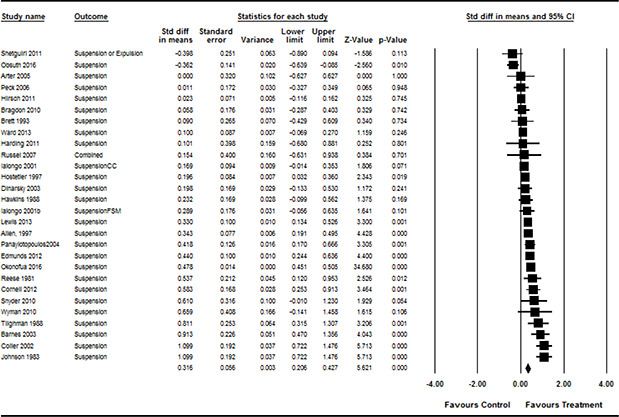

We ran analysis testing the impact of school‐based interventions on different types of exclusion. Evidence suggests that interventions are more effective at reducing expulsion and in‐school exclusion than out‐of‐school exclusion. In fact, the impact of intervention in out‐of‐school exclusion was close to zero and not statistically significant.

Nine different types of school‐based interventions were identified across the 37 studies included in the review. Four of them presented favourable and significant results in reducing exclusion (i.e., enhancement of academic skills, counselling, mentoring/monitoring, skills training for teachers). Since the number of studies for each sub‐type of intervention was low, we suggest that results should be treated with caution.

A priori defined moderators (i.e., participants’ characteristics, the theoretical basis of the interventions, and quality of the intervention)showed not to be effective at explaining the heterogeneity present in our results. Among three post‐hoc moderators, the role of the evaluator was found to be significant: independent evaluator teams reported lower effect sizes than research teams who were also involved in the design and/or delivery of the intervention.

Two researchers independently evaluated the quality of the evidence involved in this review by using the EPOC tool. Most of the studies did not present enough information for the judgement of quality bias.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

The evidence suggests that school‐based interventions are effective at reducing school exclusion immediately after, and for a few months after, the intervention. Some specific types of interventions show more promising and stable results than others, namely those involving mentoring/monitoring and those targeting skills training for teachers. However, based on the number of studies involved in our calculations, we suggest that results must be cautiously interpreted. Implications for policy and practice arising from our results are discussed.

1. Background

1.1 THE PROBLEM, CONDITION OR ISSUE

1.1.1 School discipline

Discipline problems are frequent in schools and they may have a harmful effect on pupils’ learning outcomes. A lack of discipline and the subsequent potential increase in school disorder (e.g. bullying, substance misuse) can seriously threaten the quality of instruction that teachers provide, hamper pupils acquisition of academic skills and subsequently reduce their attachment to the education system (Gottfredson, Cook, & Na, 2012).

As such, discipline represents a serious concern for parents and teachers, demanding significant efforts and resources from schools (Kaplan, Gheen, & Midgley, 2002). The PISA 2009 report (OECD, 2010) stated that schools registering higher levels of disciplinary problems result in teachers spending less time on learning in order to deal with such issues. In its 2012 version, the PISA report asked students about school discipline. Results found that “28% of students reported that teachers had to wait a long time to quiet down every class, or almost all classes”(OECD, 2013). Being more precise, the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) revealed that teachers spend at least 20% of lesson time dealing with disruption and administrative tasks. In the United Kingdom, the Behaviour Survey 2010 states that 80% of school teachers felt their ability to teach effectively was impaired by students’ poor behaviour (Massey, 2011). On a global level, evidence suggests that 13% of teachers’ time is, on average, spent maintaining order (OECD, 2009).

Schools use different procedures to manage discipline, including a range of punitive responses (e.g., loss of privileges, additional homework or detention). Among these, exclusion is normally seen as one of the most serious punishments. Although types and lengths vary from country to country, school exclusion (also known as school suspension in the United States) 1 can be broadly defined as a disciplinary sanction imposed in reaction to students’ behaviour (i.e. violations of school policies) by the responsible authority. In concrete terms, exclusion entails a removal from regular teaching for a period of time during which students are also not allowed to be present on school premises. Specifically, fixed‐term exclusions consist of a limited number of hours or days (Cornell, Gregory, & Fan, 2011), whereas permanent exclusion (i.e., expulsion) involves the pupil being transferred to a different school, or educated outside of the regular education system (Spink, 2011; Webb & Vulliamy, 2004).

Even if school policies suggest that exclusion should be used as a last resort, reserved for only the most serious and persistent offences (Gregory & Weinstein, 2008a; Skiba & Peterson, 1999; Skiba, Trachok, Chung, Baker, & Hughes, 2012), research evidence suggests that minor offences can also provoke this type of punishment (Munn, Cullen, Johnstone, & Lloyd, 2001; Skiba, 2014). Fenning et al., (2012) provide a case in point: their research concluded that suspension and expulsion were the most common types of punishment for minor problems such astardiness and school truancy. These findings were also confirmed by Liu (2013) who found that 48% of suspensions lasting a maximum of five days targeted minor disorder or disruptive behaviours.

In terms of prevalence, data provided by the UK Department for Education (academic year 2011/12) shows that in England fixed‐term exclusion affects 3.5% of the school population whereas permanent exclusion applies to only 0.06%. The national figures suggest that students in secondary‐level education (6.8% of the school population) as well as those in special education (14.7%) are the most likely to experience fixed‐term exclusion (DfE, 2013). In the United States, data provided by the Department of Education (academic year 2011/12) concluded that 7.4% (3.5 million) of students were suspended in school, 7% (3.45 million) were suspended out‐of‐school, and less than one per cent were subject to expulsion (around 130,000 students). Black students and those presenting disabilities are, respectively, three and two times more likely to be excluded compared to White and non‐disabled pupils (U.S. Department of Education, 2012).

International comparisons of exclusion prevalence rates are not available in the literature examined. Indeed, differences in use, extent and recording (i.e., unreported exclusions) make an international estimation challenging. In Table 1, the reader will find information regarding the use of exclusion in a sample of high‐ and middle‐income countries. The information is limited to a convenience sample involving twelve different cases to allow an overview of i) the types of exclusion used in these countries, ii) the length of the sanction, iii) the authority responsible for determining this sanction, iv) the behaviours for which school exclusion is permissible, and, in cases where information was available, the table also includes v) the local prevalence of exclusion. This does not claim to be a representative sample of all countries, but as an initial approach will help provide a more complex picture of the phenomenon. In addition, this comparison was intended to help with searches for studies that could be potentially included in the systematic review. For instance, by comparing exclusion in different countries, it was found that the same school sanction had different names in different countries (e.g., “stand‐down” in New Zealand, “exclusion” in the UK and “suspension” in the US).

Table 1.

Comparative description of school exclusion in a sample of high‐ and middle‐income countries

|

Country |

Name given |

Type of exclusions |

Length (for fixed exclusions) |

Who makes the decision? |

Legal reasons for exclusion |

Prevalence 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Australia 3 (New South Wales) |

Suspension |

Short suspensions |

4 school days. |

School Principal |

Continued disobedience and aggressive behaviour |

Unknown |

|

Long suspensions |

Up to 20 school days. | School Principal | Physical violence, use or possession of prohibited weapons, firearms or knife, possession, use or supply of a suspected illegal substance, serious criminal behaviour, use a weapon, persistent or serious misbehaviour | |||

|

Expulsion |

Permanent |

Permanent |

School Principal |

In serious circumstances of misbehaviour, the principal may expel a student of any age from their school. The principal may also expel a student who is over 17 years of age for unsatisfactory participation in learning. |

||

|

Canada 4 (Ontario) |

Suspension |

Short‐term Long‐term |

1 to 20 school days. More than five school days are considered long‐term. |

School Principal. Parents must be informed within 24 hours. All suspensions can be appealed to the school board. |

Threat to inflict serious bodily harm on another person, possessing alcohol or illegal drugs, being under the influence of alcohol, swearing at a teacher or at another person in a position of authority, committing an act of vandalism that causes extensive damage to school property, or bullying. |

2.76% of enrolled students (N= 2,014,407). Academic Year 2013‐2014 5 |

|

Expulsion |

From school From all schools (in this case, the students must be offered alternative education) |

Indefinite. |

School Principal should recommend expulsion to the school board. Parents must be informed within 24 hours. All expulsions can be appealed at a tribunal. |

Possessing or using a weapon, physical assault on another person that causes bodily harm requiring treatment by a medical practitioner, sexual assault, trafficking in weapons, trafficking in illegal drugs, robbery, drinking alcohol. |

0.02% of enrolled students (N= 2,014,407) Academic Year 2013‐2014 6 |

|

|

Chile 7 |

Suspension |

Fixed. Implemented inside the school premises |

The law does not limit the duration of fixed suspensions. Each school community issues their own disciplinary code and defines disciplinary sanctions and their duration. |

Disciplinary Board |

Defined for each school, but it must be used in exceptional cases |

Unknown |

|

Expulsion |

School Principal |

Conduct that directly threatens the physical or psychological integrity of any member of the school community 8 |

Unknown |

|||

|

Colombia 9 |

Suspension |

Fixed |

Each school community issues their disciplinary codes and defines disciplinary sanctions and their duration. Normally fixed exclusion lasts 3 days. |

Discretionary |

Violation to the code of conduct |

Unknown |

|

Definitive |

Unknown |

|||||

|

Costa Rica 10 |

Suspension |

Fixed |

Up to 8 school days. |

School Principal |

Not clearly stated |

Unknown |

|

Permanent |

School Board |

Permanent disruptive/defiant behaviour, non‐compliance with previous sanctions, violence and aggressions towards a member of the school community, lack of moral integrity. |

||||

|

England 11 |

Exclusion |

Fixed (in‐school, out‐of‐school) |

1‐45 days per year. After 5 days of fixed out‐of‐school exclusion, the school must provide alternative education. |

Discretionary School principal |

Repeated failure to follow academic instruction, failure to complete a behavioural sanction (e.g. with a detention, a decision to change the sanction to exclusion would not automatically be unlawful), repeated and persistent breaches of the schools’ behavioural policy. |

Academic year 2014‐2015 12 3.8% of students (all schools) 7.51% of students (secondary schools) |

|

Permanent |

0.07% of students (all schools) 0.15% of students (secondary schools) |

|||||

|

France 13 |

Exclusion |

Temporary exclusion from the classroom |

Maximum of 8 days. |

Consultation between the various members of the pedagogical and educational team |

Serious cases of violence (physical or psychological) against the school community |

Unknown |

|

Temporary exclusion from school |

Maximum of 8 days. |

School principal or school board |

||||

|

Definitive exclusion |

Permanent |

Disciplinary board. The student should be represented on the disciplinary board. |

||||

|

Finland 14 |

Exclusion |

In‐school exclusion and out‐of‐school exclusion with the school obligated to provide education at home. |

In‐school exclusion: remainder of the day. Out‐of‐school exclusion: no more than 3 months. It is a very infrequent measure. |

Teacher and school principal using a formal procedure. In cases of out‐of‐school exclusion, a personal plan of education must be provided and local social services should be informed. |

Threats or serious violence that would endanger the safety of other members of the school community |

Unknown |

|

Permanent exclusion does not exist in the local law. |

||||||

|

Malta |

Suspension |

Fixed term suspension |

Suspension for the rest of the day or for a few days. The number of days is not stated in the law. |

Must be applied by the Head of School after the student's parent or guardian has been informed. The National Board for School Behaviour should be consulted. |

The law defines 3 levels of misbehaviour. Suspension and expulsion are restricted for level 3, meaning serious offenses only. No further details. |

Unknown |

|

Expulsion |

Expulsion |

Permanent |

||||

|

Norway 15 |

Exclusion |

Fixed exclusion, expulsion for the rest of the year and loss of rights to education. |

Primary education (level 1‐7): exclusion from specific lessons or for the rest of the day. Secondary education (level 8‐10): maximum of 3 days. Expulsion and loss of rights are defined in the Educational Law but its use is extremely rare. |

The school principal in consultation with the pupil's teacher, unless the local authority defines a different procedure. |

Exclusion is used as a last resort and can be justified only for serious issues of violence. The law suggests the use of alternatives such as mediation before imposing an exclusion. |

Unknown |

|

New Zealand 16 |

Stand‐down |

Stand‐down |

The student is removed from school for 5 school days in a term or 10 school days in a year. |

School Principal, through a formal procedure that includes informing the family, the Education Authority and the school board. |

Drugs (including substance abuse), continual disobedience and physical assault on other students were the most prevalent causes for stand‐down, suspensions, exclusion and expulsion. |

1.5% of school population (2015) |

|

Suspension |

Suspension |

The student is removed from school for no more than 7 days. |

School Board |

0.3% of school population (2015) |

||

|

Exclusion |

Expulsion |

Maximum of 10 days in a year. |

School Board |

0.1% of the total student population under 16 years old (2015) |

||

|

Exclusion |

Expulsion |

A student under the age of 16 would be excluded from the school, with the requirement that the student enrolls elsewhere |

School Board |

0.2% of the total student population over 16 years old (2015) 17 |

||

|

A student aged 16 or over would be expelled from the school, and the student may or may not enroll at another school. |

||||||

|

The US, Washington DC 18 |

Suspension |

Suspension (short‐term and long‐term) is a restriction in attending school or school activities. |

Short‐term suspension: maximum of 10 consecutive days. Long‐term suspension: more than 10 consecutive days. |

Certified teachers can decide a suspension but it must be communicated to the school principal. Short‐term suspensions must be formally communicated to the student/parents. Long‐term suspensions and expulsions require a formal process (i.e., written notice by the school district) and should be known by the School Principal. |

Violation of school district rules |

3.89% of all Washington students have been suspended or expelled (2014–15) The rate of suspensions and expulsions across districts range between nearly 0% to over 10% of students 19 . |

|

Expulsion |

Expulsion makes this restriction indefinite. |

Maximum: 1 calendar year |

Violation of school district rules, serious violence, gang activity on school grounds. |

|||

|

Emergency expulsion |

Temporary. The student would go back once the danger ceases |

The student's presence poses an immediate and continuing danger to others. The student's presence poses a threat of substantial disruption in the classroom. |

||||

|

The US, Virginia 20 |

Removal from classes |

In‐school |

Teacher |

Disruptive behaviour |

Unknown |

|

|

Suspension |

Suspension (short‐term and long‐term) is a restriction in attending school or school activities. |

Short‐term suspension: 10 consecutive or 10 cumulative school days in a school year Long‐term suspension: more than 10 school days but less than 365 calendar days. |

Imposed by the school principal, any assistant principal or, in their absence, any teacher. The suspension should entail a formal process. The student must be heard. |

Violation of school code of conduct |

||

|

Expulsion |

Expulsion makes the restriction last longer. |

A student is not permitted to attend school within the school division and is ineligible for readmission for 365 calendar days after expulsion. |

Imposed by a committee from the school board. Includes a formal process, written notice and appeal. |

Criminal activity, carrying a weapon, drug related offences, or when the pupil presence is a clear threat for the school community. |

||

|

The US, Texas 21 |

Suspension |

In‐school suspension (e.g., seclusion units) |

In‐school suspension lasts between 1 class and several days. |

Low‐level offences are dealt with on a discretionary basis (according to a defined code of conduct) by the designated administrator (usually the principal or vice principal). Higher‐level offences require mandatory removal from the classroom. Rules for a due process are defined. |

Violation of school code of conduct (unruly, disruptive, or abusive behaviours) |

9.24% (2014‐2015) 22 |

|

Expulsion |

Out‐of‐school suspension |

Out‐of‐school suspension should be no longer than 3 days. |

Unknown |

Weapon carrying, serious violence or crimes. |

4.33% (2014‐2015) |

|

|

In the case of serious offences, a student can be expelled from school. |

At least 1 year Disciplinary Alternative Education Program (DAEP) for students removed for over 3 days (no maximum period provided). |

Unknown |

3.39% (2014‐2015) |

Prevalence was calculated by dividing the number of excluded students per year (numerator) by the total number of students per year (denominator).

Information retrieved from “Suspension and Expulsion of School Students” New South Wales Government. Updated in October 2014 https://www.det.nsw.edu.au/policies/student_serv/discipline/stu_discip_gov/suspol_07.pdf

http://www.supereduc.cl/. Additionally, the information can be found in Torche & Mizala (2012)

In Colombia, each school must define school exclusion length. This is established in the Ley General de Educación N° 115, February 1994. http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles‐85906_archivo_pdf.pdf. Additional information can be retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article‐86906.html

In England, exclusions are regulated by the Education Act of 2002

In France, school exclusions are regulated by the Code de l'education: http://www.education.gouv.fr/cid56670/sanctions‐scolaires‐reforme‐des‐procedures‐disciplinaires‐dans‐les‐etablissements‐scolaires.html

Basic Education Act 628/1998 (Amendments up to 1136/2010). http://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1998/en19980628.pdf

LOV 1998‐07‐17 nr 61: Law on Primary and Secondary Education (The Education Act)

In New Zealand, the guidance for suspensions is based on the Education Act of 1989 and the Education Rules 1999 (Stand‐down, Suspension, Exclusion, and Expulsion)

All data referring to prevalence was extracted from a governmental report informing data from academic years 2015. http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/147764/SSEE‐Indicator‐Report‐2015‐Data.pdf

In the US, procedures and definitions of school suspension vary among states. Here, we use Washington State as an example. For more details, see www.k12.wa.us/Safetycenter/Discipline/pubdocs/Suspension‐expulsion‐rights.pdf

Data extracted from Office of Super Intendent of Education (OSIP), State of Washington. http://www.k12.wa.us/DataAdmin/PerformanceIndicators/DataAnalytics.aspx#discipline

See the specific section for Virginia, p. 10‐16 in https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/sites/default/files/disciplinecompendium/School%20Discipline%20Laws%20and%20Regulations%20Compendium.pdf

See the specific section for Texas, p. 14–27 in https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/sites/default/files/discipline‐compendium/School%20Discipline%20Laws%20and%20Regulations%20Compendium.pdf

Data extracted from the Texas Education Agency based on categories which count students once. https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/cgi/sas/broker

The comparative data incorporated in the table above suggests heterogeneity in the application of exclusion. For instance, in the US, Norway and England, educational systems distinguish between fixed and permanent exclusion. However, in some educational systems, such as Finland's, the law only permits fixed‐term exclusion. Concerning length, England limits fixed‐term exclusions to a maximum of 45 days per school year while New Zealand's legislation allows exclusions for a maximum of 10 days per year. On the other hand, it is important to note that in some countries – such as France – specific laws define and regulate exclusion, whereas in others – like Chile and Colombia – the ability to set the length of the sanction is granted to each school.

Although the data on prevalence is limited to a few countries, the percentage of in‐school exclusion seems to be larger than out‐of‐school exclusion and expulsion. In New Zealand, the data suggests that the use of exclusion is marginal particularly when compared with some areas in the US and the UK.

1.2 PREDICTORS AND OUTCOMES

The research concerning predictors and outcomes of school exclusion has some limitations it is necessary to address before arriving at any final conclusions. Regarding predictors, only ethnicity seems to have a clear role in predicting exclusion. For other variables of interest such as sex, age or socio‐economic status most of the evidence is limited to bivariate associations.

Regarding the outcomes, while there is a stark link between misbehaviour (e.g., school drop‐out and delinquency) and school exclusion, there is no clear causal relationship. Notwithstanding decades of research on school exclusion and its impact on later behaviour, we are still at an initial stage for testing causal associations in these matters. The association between exclusion and these negative outcomes may simply reflect underlying behavioural tendencies that lead to conduct problems, exclusion and poor outcomes later in life – that is, the antisocial syndrome described by Farrington (1997). In fact, school exclusion and the behaviours outlined here as “negatives” could be explained by the personality traits of the syndrome.

As stated by Sutherland and Eisner (2014) “it is currently unclear whether the disciplinary action itself has a causal effect over and beyond the social, familial and behavioural characteristics of the affected children. To date, studies have used analytical approaches that are unable to reliably establish a robust link between exclusion and outcomes such as criminal behavior.” Some longitudinal studies have attempted to deal with this matter by controlling for previous behavioural characteristics that could alter the impact of the sanction. When this is the case, the methodological details are explicitly presented in this review.

Keeping these reservations in mind, the following section describes variables associated with the prediction of school exclusion, as well as some negative outcomes linked to exclusion.

1.2.1 Predictors of school exclusion

From a normative point of view, school exclusion is a punitive response for misbehaviour. In that sense, behavioural problems seem to be the most obvious empirical predictor for exclusion. Reinke, Herman, Petras, & Ialongo, (2008) illustrate the role of problem behaviour in exclusion by conducting a latent class analysis. Participants in the subclass of boys exhibiting behavioural problems only (i.e., isolating other academic/learning difficulties) were almost 4 times more likely to be suspended (OR = 3.42; 95%CI 1.36 to 8.58; p < .05) than their non‐problematic peers. Similarly, Pas, Bradshaw, Hershfeldt, & Leaf, (2010) found that after controlling for student, teacher, classroom, and school level covariates, the strongest predictor for out‐of‐school suspension was disruptive behaviour (OR = 4.83; 95%CI 4.10 to 5.68; p < .05).

Despite the role of behaviour in school exclusion, research suggests that it is not the sole or even the most prominent predictor. In fact, previous findings show a more complex scenario where exclusion is also strongly predicted by gender, ethnicity, age, economic background, and special educational needs (Costenbader & Markson, 1998a; Mcloughlin & Noltemeyer, 2010; Monroe, 2005; Nickerson & Spears, 2007; Noltemeyer & Mcloughlin, 2010; Skiba et al., 2011; Yudof, 1975). In the following paragraphs, we offer an overview of the role of these variables in predicting school exclusion.

Gender as a predictor of exclusion

Data provided by the Department for Education in England (DfE) 2011/12 suggests that male pupils are around three times more likely to be punished by exclusion than female pupils (DfE, 2013). The same trend can be observed in the study published by Liu (2013) based on longitudinal data from 13,875 American students. The study reports the predominance of males being excluded, but recognises that the proportion of females excluded tends to increase from elementary (23.7%), to secondary (32.7%), to high school (35.2%). More specifically, Bowman‐Perrott et al. (2013, p. 91) concluded that, based on a sample of 2,597 pupils, the predominance of males in exclusion rates (OR = 2.28) was even larger in the case of pupils with learning disabilities (OR = 4.31). 2

Ethnicity

Research outcomes suggest a clear and consistent disproportionality in the prevalence of ethnic minorities as a target for disciplinary exclusion (Anyon et al., 2014; Gregory, Skiba, & Noguera, 2010). In the US, different sources of data show that school exclusion overly affects minorities such as Afro‐Caribbean (Noltemeyer & Mcloughlin, 2010), Latino (Skiba et al., 2011) and American Indian students (Gregory et al., 2010) in comparison with their White peers. In the UK, data from the (DfE, 2012) showed that: “The rate of exclusions was highest for Travellers of Irish Heritage, Black Caribbean and Gypsy/Roman ethnic groups. Black Caribbean pupils were nearly 4 times more likely to receive a permanent exclusion than the school population as a whole and were twice as likely to receive a fixed period exclusion.” Notably, recent multivariate analysis points out that racial disproportionality in exclusion still remains significant after controlling by behaviour, number and type of school offences, age, gender, teacher's ethnicity, and socio‐economic status (Fabelo et al., 2011; Noltemeyer & Mcloughlin, 2010; Rocque & Paternoster, 2011; Skiba, Michael, Nardo, & Peterson, 2002). Consider, for instance, a substantial longitudinal report produced by Fabelo et al., (2011) in Texas (N=928,940), intended to isolate the effect of race alone on disciplinary actions. The study used a multivariate analysis controlling for 83 different variables. The findings suggest that African‐American students were 31% more likely to be removed from classrooms compared to White and Hispanic students. In the same vein, Skiba (2015) has argued that, in the United States at least, racial disproportionality in school discipline is ubiquitous. In his opinion, ethnic minorities are overrepresented in almost all types of school punishment. Even more worryingly, instances of exclusionary discipline among African Americans have continued to increase over the years.

Possible reasons for this overrepresentation of Black students, even when controlling for demographic and risk factors, have been addresses by some scholars, who suggest that a racist bias could explain the phenomenon (Losen, 2011; Skiba et al., 2002; Skiba, 2015). In particular, Simson (2014) asserts that racial stereotyping (conscious or unconscious) as well as a cultural mismatch between teachers and students can explain at least some part of the existing racial disproportionality in school discipline.

It is important to say that, as stated by Theriot, Craun, & Dupper (2010, p.14), “the over‐representation of ethnic minority students, especially African American students, in school suspension and expulsion is one of the most consistent—and perhaps most controversial—findings in the extant literature on school discipline.” In general, studies using solid and strong multivariate models highlight the discrimination against racial minorities compared to White students.

Age as a predictor of exclusion

The likelihood of being punished by exclusion increases with age, being more frequent during adolescence. In England, 52% of permanent exclusions are imposed on pupils aged between 13 and 14 (DfE, 2013). In the case of American students, the results follow a similar trend. In fact, data reported by Liu, (2013) pointed out that suspensions reach a peak in ninth grade (i.e., 14 to 15 years of age). Also based on a sample of American students, Raush & Skiba, (2004) concluded that the number of out‐of‐school suspensions was significantly higher in secondary schools compared to elementary schools.

Socio‐economic status (SES)

Low SES has also been identified as a predictor of high rates of disciplinary exclusion. The UK Department of Education (DfE, 2012) compared the rates of exclusion by eligibility for free school meals (FSM). Those eligible for FSM were 4 times more likely to be punished by a permanent exclusion and around 3 times more likely to get a fixed‐period exclusion than children who were not eligible. In the US, Nichols, (2004) using a sample of 52 schools (37,000 students), found a similar pattern – but the correlation between FSM and exclusion was higher and more significant for pupils in middle school (r = .84; p <. 01) than for elementary (r = ‐.12) or high school pupils (r = .48). In Australia, Hemphill et al., (2010), using multilevel mixed‐effects logistic regression (N = 8,028 students), concluded that pupils settled in low SES neighbourhoods were exposed to higher rates of exclusion (8.7%) when compared with pupils in high SES areas (2.9%).

However, the evidence still seems to be inconclusive in this respect. Recently, Skiba et al., (2012), using a multilevel approach, tested data from 365 schools and a total number of 43,320 students. They concluded that when comparing those students eligible for free or reduced‐cost lunches with their non‐eligible peers, the first were more likely to get out‐of‐school exclusions (OR= 1.27; p<.05). However, contrary to expectations, the eligibility for free or reduced meals resulted in a negative predictor of permanent exclusion (OR= 0.03; p<.05).

Special educational needs (SEN)

Although an increasing amount of research has focused on predictors of school exclusion, analysis of the role of SEN still seems to be limited. In 2007, Achilles, McLaughlin, and Croninger differentiated the role of three different SEN, namely emotional/behavioural disorders (EBD), attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADHD), and learning disabilities (LD). Higher rates of exclusion were more likely among those with EBD (OR = 1.49; p<. 001) compared with ADHD (OR = 2.58; p < .001) or LD (OR = 5.44; p < .001). Recently, Bowman‐Perrott et al. (2013), using three waves from the Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study (SEELS), confirmed that children with emotional or behavioural disorders (OR = 3.95; p <.05) and attention‐deficit or hyperactivity disorders (OR = 4.96; p <.05) were more likely to get suspended or expelled from school than children with learning disabilities (OR = 2.54; p <.05). In a study involving 2,750 students and 39 American schools, Sullivan, Van Norman, & Klingbeil (2014) also observed differences between types of disabilities: those presenting an EBD were at a far greater risk of exclusion (OR = 6.78; SE=0.21) than those presenting other health impairments (i.e., a specific learning disability, intellectual disability, speech and language impairment). When controlling for race and gender, and parents’ education, this trend remained stable and significant. It is important to emphasize that the associations between this disability and exclusion mainly reflect differences in behaviour, respectively psychological or chronic behavioural problems.

1.2.2 Negative outcomes linked to school exclusion

Supporters of zero tolerance policies have pointed out that the use of exclusion can persuade students to account for their behaviour and lead to a decrease in rule‐breaking (Bear, 2012). However, most of the research has consistently documented the negative impact of these types of sanctions (APA Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008; Chin, Dowdy, Jimerson, & Rime, 2012; Hemphill, Toumbourou, Herrenkohl, McMorris, & Catalano, 2006; Sharkey &Fenning, 2012). In particular, previous research suggests that school exclusion is related to serious negative outcomes in at least three dimensions of young people's development: behavioural, academic, and future social inclusion.

Behaviour

Some literature related to the relationship between exclusionary punishments and behaviour suggests that such harsh punishments could result in a spiral into more defiant behaviour by students. Raffaele‐Mendez, (2003), for instance, found a moderate and significant correlation (r = .39) between out‐of‐school exclusion (grades 4 to 5) and subsequent exclusion (grade 6). Similarly, Theriot, Craun, & Dupper, (2010) found that pupils punished by in‐school and out‐of‐school exclusion were slightly more likely to get the same punishment again (ORin‐school = 1.25; p < .001; N = 9706 and ORout‐of‐school = 1.32; p < .001; N = 9706).

Using longitudinal data, Arcia, (2006:366) concluded that school dropout was another behavioural consequence of exclusion. In fact, “43% of students who were suspended 21 or more days dropped out 3 years after their ninth‐grade enrolment.” Similarly, Cratty (2012:649) found a positive correlation between out‐of‐school suspensions and dropout rates. In particular, “those who had an early record of multiple exclusions registered 60% dropout during high school” when compared with non‐excluded students.

The use of exclusion, in turn, is linked with more serious behavioural outcomes such as antisocial conduct, delinquency and entry into the juvenile justice system. Longitudinal research carried out by Hemphill et al. (2006:736) argues that “school suspensions significantly increased antisocial behaviour 12 months later, after holding constant established risk and protective factors (OR = 1.5; 95%CI 1.1 to 2.1; p< .05; N = 3655)”In terms of the involvement of school excludees in the criminal justice system, Costenbader & Markson, (1998) found significant differences between excluded students and those never excluded. In their view, “while 6% of the students who had never been suspended reported having been arrested, on probation, or on parole, 32% of the externally suspended subsample and 14% of the internally suspended subsample responded positively to this question. Males reported significantly more involvement with the legal system than did females.” (p.67). Meanwhile, Challen & Walton, (2004), studying a population of males in the criminal justice system, concluded that more than 80% had been previously excluded from school 3 .

Academic achievements

Evidence suggests that periods of exclusion may have detrimental effects on pupils’ learning outcomes. Exclusion is accompanied by missed academic activities, alienation, and demotivation in relation to academic goals (Brown, 2007; Michail, 2011). In particular, Hemphill et al., (2006) found that excluded pupils were slightly more prone to fail in the academic curriculum when compared with non‐excluded students (OR = 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.5, p< .01). Along similar lines, Arcia, (2006) produced a longitudinal retrospective study regarding the associations between exclusions and achievements from fourth to seventh grade. After three years, non‐excluded students displayed substantially higher reading achievement scores when compared with their non‐excluded peers. In fact, seventh‐grade students who were excluded for 21 days or more achieved scores similar to fourth‐grade students that had not been excluded. Finally, Raffaele‐Mendez, (2003) added that those excluded were also less likely to graduate from high school on schedule.

Future social inclusion

Some studies have pointed out that young people excluded from school can also register a high risk of becoming “Not in Education, Employment, or Training” (NEET) in the future. In 2007, Brookes, Goodall, & Heady stated that students who had been excluded were 37% more likely to be unemployed during adulthood. Spielhofer et al. (2009) showed that among individuals with long‐term status as NEET, the majority had previous experienced of exclusions and truancy. More precisely, Massey (2011) argued that approximately one out of two excluded children will be NEET within two years of their exclusion.

Research has also illustrated the long‐term implications of exclusion for society as a whole. In economic terms, the cost of excluding children from school places a demand on public resources. Although the literature on this matter is still limited, Brookes et al. (2007) produced a report regarding the costs of permanent exclusion in the United Kingdom. The analysis encompasses an estimation of costs for the individual as well as for the educational, health, social and criminal justice services. Overall the cost, in 2005 prices, of permanently excluding a student was estimated at £63,851 per year to society.

While there is a stark link between the aforementioned negative outcomes and school exclusion, these should not be regarded as causal. Notwithstanding decades of research on school exclusion and its impact on later behaviour, we are still at an initial stage for testing causal associations in these matters. The association between exclusion and these negative outcomes may simply reflect underlying behavioural tendencies that lead to conduct problems, exclusion and poor outcomes later in life – that is, the antisocial syndrome depicted by Farrington (1997). In fact, school exclusion and the behaviours described here as “negative outcomes” could be explained by the same underlying factors or personality traits characterising the syndrome.

Despite the lack of empirical support for a causal association, some criminological theories provide a plausible explanatory framework to understand the connection between punishment and the persistence of deviant behaviour. Labelling theory, for example, suggests that those punished (by exclusion) and labelled as “deviant” may start behaving in ways that conform to their newly formed self‐image: by limiting their interactions with integrated students, for example, and shunning conventional social systems such as school (Krohn, Lopes, & Ward, 2014, p. 179). Likewise, Sherman's defiance theory (1993) elucidates the circumstances in which a punishment can produce more antisocial behaviour, such as defiance, instead of compliance with rules. In his view, punishment can increase the prevalence, incidence or seriousness of future offending when offenders deny responsibility, and when they perceive sanctions as unfair, stigmatising and imposed by an illegitimate authority.

Finally, in addition to all these findings and the rationale around the negative outcomes linked to school exclusion, it is important to mention that, so far, there is no evidence demonstrating that exclusion is effective for improving school discipline (Skiba, 2014). What is more, in the short term, exclusion seems to directly deny students’ right to access education as well as reducing adult supervision for those who are most at risk of further deviant behaviour, or most in need of teachers’ support.

1.3 THE INTERVENTION

1.3.1 School‐based programmes

The prevalence of exclusion and its adverse correlated consequences have caught the attention of policy makers and programme developers. As a result, a range of interventions have been designed and implemented to improve school discipline. In the present review, we include different types of school‐based intervention aimed at reducing school exclusion as a punishment for inappropriate behaviour. These interventions include those targeting individual risk factors or school‐related factors, as well as those using a more comprehensive strategy that includes parents, teachers, school administrators, and the community.

Interventions targeting individual risk factors include, for instance, cognitive‐behavioural approaches such as anger management programmes or skills training for children (e.g., Humphrey & Brooks, 2006). Another type of intervention focusing on student behaviour – or, more precisely, students’ skills for conflict resolution – are restorative justice programmes (e.g., Schellenberg & Parks‐Savage, 2007; Shapiro, Burgoon, Welker, & Clough, 2002)In general, these interventions target motivated children and train them in practical skills to deal with anger, solve conflicts or become more assertive in social relationships. Such interventions are normally organised within a curriculum and implemented during school hours. The curriculum involves a package of group or one‐to‐one sessions using a wide range of techniques such as instruction, modelling, role‐play, feedback, and reinforcement, among others (Gottfredson, Cook, & Na, 2012; Schindler & Yoshikawa, 2012).

At the classroom level, interventions may target teachers’ abilities in classroom management (Pane, Rocco, Miller, & Salmon, 2013). The training for teachers encompasses instructional skills, such as guidelines for teaching rules and maintaining attendance, and non‐instructional skills, such as group management techniques, reinforcing positive conduct, and techniques to explain expected behaviour. Both skill sets are aimed at improving the learning process, preventing misbehaviour and encouraging positive participation by pupils (Averdijk, Eisner, Luciano, Valdebenito, & Obsuth, 2014).

Some schools offer mental health services independently or via community agencies. Experienced clinicians are located in schools in order to deliver individual, group, and/or family therapy. Clinicians may also be available for teacher consultation on matters related to students’ behavioural and emotional issues. All these interventions may target a reduction in out‐of‐school exclusion (Bruns, Moore, Stephan, Pruitt, & Weist, 2005).

Alternatively, comprehensive prevention strategies target students, families, teachers and school managers as well as the community as a whole (Bradshaw, Waasdorp, & Leaf, 2012; Flay & Allred, 2003; Colin Pritchard & Williams, 2001; Snyder et al., 2010). A well‐known comprehensive programme is the School‐Wide Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS). The programme aims to provide support for positive conduct by building proactive school‐wide disciplinary procedures (i.e., improving school climate and reducing problem behaviours). SWPBIS incorporates a multi‐level approach: from whole school prevention, to group‐based intervention for problematic pupils, and personalised, tailored interventions for high‐risk students. The basic elements of the programme are: i) building a school culture for both social and academic attainment, ii) early prevention of problem behaviours, iii) teaching social skills to all students, iv) using behaviour support practices, and v) actively using data for decision‐making. Research reports promising results, although further and stronger evaluation designs need to be undertaken (Gottfredson et al., 2012; Maag, 2012).

Previous reviews

In 2013/14 we conducted a systematic search of reviews and meta‐analyses assessing the effectiveness of school‐based programmes for promoting early prevention of risks (Averdijk et al., 2014). The results suggested there had been no previous meta‐analysis aimed at assessing the effectiveness of different types of interventions for reducing disciplinary school exclusion. Probably the most similar study is one published by Burrell, Zirbel, & Allen, (2003) who conducted a meta‐analysis on the effectiveness of mediation programmes in educational settings. Among many other outcomes, the analysis suggested that these interventions had a desirable effect (r = ‐.287, k = 17, N = 5,706, p < .05) on administrative suspensions, expulsions and disciplinary actions. However, in this meta‐analysis suspension was reported along with other disciplinary actions, and the study did not compare mediation with any other intervention (as proposed in the present meta‐analysis). The authors also call for a cautious interpretation given the high heterogeneity of primary results. A similar type of analysis was followed by Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, (2011) and Gottfredson, Wilson, & Najaka, (2002). In both studies, school exclusion was coded as an outcome, but the final meta‐analysis did not report on the impact of the intervention specifically in relation to this targeted outcome.

Likewise, Solomon, Klein, Hintze, Cressey, & Peller, (2012) conducted a meta‐analysis exclusively testing the effectiveness of School‐Wide Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS) programme. Despite a small number of included studies reporting data on exclusion, the review does not report effect sizes by measuring their increase/decrease. Rather, the review reports effect sizes on the reduction of office discipline referrals and problematic behaviour.

In addition, two narrative reviews have recently been produced looking at intervention as a means of reducing disciplinary exclusion. Spink, (2011) explored qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies. Overall, 10 reports were found. The review concluded that multi‐agency interventions were the most frequent and that they could have a positive effect on reducing exclusion of pupils who are at risk. As expected, the study did not report a meta‐analysis of effect sizes. In 2012, Johnson produced another narrative review identifying programmes that may be an alternative for suspension in school systems. The search strategies were not clear enough to allow replication and, again, the nature of the design does not allow for the calculation of effect sizes.

1.4 WHY IT IS IMPORTANT TO DO THE REVIEW

Despite a growing body of research on the negative side effects of exclusion, no previous meta‐analysis based on a comprehensive systematic review has been conducted to synthesize evidence assessing the impact of school‐based interventions in reducing disciplinary exclusion. The current review addresses this gap by meta‐analysing results from existing published and unpublished studies, providing a statistical assessment of the overall effect of school‐based interventions at reducing exclusion.

This meta‐analytic investigation has clear implications for policy making. The results provided by the present study would produce a much‐needed evidence base for school managers, policymakers and researchers alike. These results can contribute to tackling the adverse developmental, social and economic effects of school exclusion mentioned in the previous pages, as well as potentially identifying alternative and less punitive approaches to school discipline.

2. Objectives

The main goal of the present research is to systematically examine the available evidence for the effectiveness of different types of school‐based interventions for reducing disciplinary school exclusion. Secondary goals include comparing different types of interventions (e.g., school‐wide management, classroom management, restorative justice, cognitive‐behavioural interventions) and identifying those that could potentially demonstrate larger and more significant effects.

We also aim – potentially – to run analysis controlling for characteristics of participants (e.g., age, ethnicity, level of risk); interventions (e.g., theoretical bases, components); implementation (e.g., facilitators’ training, doses, quality), and methodology (e.g., research design).

The research questions underlying this project are as follows:

Do school‐based programmes reduce the use of exclusionary sanctions in schools?

Are some school‐based approaches more effective than others in reducing exclusionary sanctions?

Do participants’ characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity) affect the impact of school‐based programmes on exclusionary sanctions in schools?

Do characteristics of the interventions, implementation, and methodology affect the impact of school‐based programmes on exclusionary sanctions in schools?

3. Methods

3.1 TITLE REGISTRATION AND REVIEW PROTOCOL

The title of the present review was registered in The Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews on January 2015. The final version of the review protocol was approved in November 2015. The title registration and the respective protocol are available at: https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/library/reducing‐school‐exclusion‐school‐based‐interventions.html

3.2 CRITERIA FOR CONSIDERING STUDIES FOR THIS REVIEW

3.2.1 Research design

Our original proposal was to include both randomised controlled trials and high‐quality quasi‐experimental studies (defined as studies using a comparison group, pre‐post testing and a statistical matching approach). To be eligible for inclusion, we stated that manuscripts must clearly report the method used to ensure equivalence between treatment and control groups, taking into account major risk factors (e.g. behavioural measures) and demographic characteristics. 4

In this review, we only present results from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). There were three reasons for our decision:

-

1.

First, even though a number of quasi‐experimental studies initially fulfilling our inclusion criteria were found by our searches, many of them fail to report baseline measures (e.g., Guardino, 2013; Hawkins, Catalano, Kosterman, Abbott, & Hill, 1999; Munoz, Fischetti, & Prather, 2014), the matching procedures were not described (e.g., Hasson, 2011; Risner, Vanderhaar, Muñoz, & Abati, 2005; St James‐Roberts & Singh, 2001) or the balance procedures did not produce statistical equivalence (e.g., Gao, Hallar, & Hartman, 2014).

-

2.

A number of the school‐based intervention programmes included in this review presented several studies, involving quasi‐experiments as well as RCTs. Some examples involve interventions such as the Positive Action Program or the School‐Wide Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports (e.g., Lewis et al., 2013; Snyder et al., 2010). In both cases, RCTs (e.g., Lewis et al., 2013; Snyder et al., 2010) were preceded by quasi‐experimental studies (Barrett, Bradshaw, & Lewis‐Palmer, 2008; Flay & Allred, 2003) . In this context, we decided to keep the strongest study design.

-

3.

RCTs are regarded to be the most compelling methodological design to test the impact of a particular treatment. This type of study has the strengths of isolating confounding factors, reducing the likelihood of alternative explanations for observed effects (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002; Sherman, Farrington, Welsh, & Mackenzie, 2002). We believe that by selecting only these studies we will achieve a more precise final estimation of the effect of school‐based interventions.

To offer a broad overview of the research testing the impact of school‐based intervention at reducing school exclusion, a list of the quasi‐experimental studies can be provided on request.

Qualitative studies were excluded from the present review as stated in the published protocol.

3.2.2 Types of participants

The present review is focused on the general population of students in primary and secondary schools irrespective of nationality, ethnicity, language, and cultural or socio‐economical background. By targeting primary and secondary schools, participants could theoretically be aged from 4 to 18 years of age.

Reports involving students who presented special education needs, disabilities or learning problems but were educated in mainstream schools were included in this review. However, reports involving students with serious mental disabilities or those in need of special schools were excluded. The rationale for this is that the results of this review are intended to be generalisable to mainstream populations of students in non‐specialised schools from all the included countries.

Students in college or higher levels of education have been excluded. Their exclusion from the review is based on previous evidence suggesting the largest number of exclusions affect pupils aged about 10 to 15 (e.g., Liu, 2013; Raush & Skiba, 2004; DfE, 2012).

3.2.3 Included interventions

We include interventions defined as school‐based: that is, delivered on school premises, or supported by schools with at least one component implemented in the school setting. In the present review, we include interventions explicitly aimed at preventing/reducing school exclusion or those measuring exclusion as an outcome.

Interventions in the present review cover a wide range of psychosocial strategies for targeting students (e.g., Cook et al., 2014), teachers (e.g., Ialongo, Poduska, Werthamer, & Kellam, 2001), or the whole school (e.g., Bradshaw, Waasdorp, & Leaf, 2012). Types of intervention include, for example, those focused on:

instructing students to identify risky behaviours and expanding their alternatives for responding appropriately to risks or harms (e.g., social skills training)

developing teachers’ skills to improve the quality of their classroom management (e.g., reward schemes)

cognitive‐behavioural treatment, such as anger management, counselling, social work, and mentoring programmes;

school‐wide interventions.

Since there was no previous review analysing school‐based prevention programmes for reducing exclusionary discipline, we wanted to include a wide range of school‐based interventions that could be effective for reducing exclusionary practices.

3.2.4 Excluded interventions

We excluded studies where the intervention was not school‐based or school supported. Even though some of these interventions targeted school students, they were community programmes or purely focused on mental health issues without any connection to schools (e.g., Henderson & Green, 2014; Schwartz, Rhodes, Spencer, & Grossman, 2013; Wiggins et al., 2009).

We also excluded interventions designed for children or adolescents who have committed a crime, that is, specialised interventions aimed at reducing reoffending or reconviction. Although suspended students may commit offences, such specialised interventions were excluded from the present review because they exceed the strategies used by schools to prevent misbehaviour and their levels of complexity make them too specific for a general population of students. School‐based prevention programmes targeting outcomes related only to students’ physical health (e.g., AIDS/ HIV prevention programmes, programmes to develop healthy eating programmes) were also excluded.

3.2.5 Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Eligible studies addressed school exclusion as an outcome. As mentioned in the background section, school suspension or exclusion is defined as an official disciplinary sanction imposed by an authority and consisting of the removal of a child from their normal schooling. This removal happens as a reaction to student behaviour that violates the school rules. We included studies testing fixed or permanent, long‐term or short‐term suspension as well as in‐school and out‐of‐school suspensions.

We excluded studies testing other disciplinary sanctions implemented in schools if they do not share the criteria described above. For instance, we excluded disciplinary sanctions such as loss of privileges, extra work, break/lunch detention, and after‐school detentions. These interventions do not involve exclusion from school or exclusion from regular teaching hours, and as such they are not covered by this review.

Secondary outcomes

For any identified study that reported findings on school exclusion as an outcome, we also coded the effects of the intervention on specific behaviour domains, focusing on internalising (e.g., inhibition, social withdrawal, anxiety or depression) and externalising (e.g., defiant or delinquent behaviours or aggressive behaviours such as bullying)problem behaviour (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1979; Achenbach, 1978; Farrington, 1989)

By coding secondary outcomes, we aimed to assess the extent to which reductions in problem behaviour are a mediator of treatment effects on school exclusion. Indeed, interventions may affect exclusion in two different ways. The first is by improving behaviour that might otherwise lead to an exclusionary measure. The second possibility is that behaviour stays the same, but that the school develops an alternative strategy to deal with the disciplinary problems.

3.2.6 Included literature

Databases and journals were searched from 1980 onwards with the aim of comprising more contemporary interventions or prevention programmes. Eligible studies included both published and unpublished book chapters, journal articles, government reports, and Doctoral theses. When the same data was published in more than one source (e.g., a book chapter and a journal article) we used all the linked manuscripts but the most complete report or the report measuring suspension was defined as the main source of data (see Section 3.4.5). That way we kept as much information as possible from a specific study but avoided over‐estimation of effect sizes. In cases where it was not clear if the manuscripts referred to the same study, we contacted the main author for further information (e.g., email communication with Barnes, Bauza, & Treiber, 2003; Bradshaw et al., 2012; Lewis, Romi, & Roache, 2012; Snyder et al., 2010; Sprague, Biglan, Rusby, Gau, & Vincent, 2016).

3.3 SEARCH METHODS FOR IDENTIFICATION OF STUDIES

The electronic searches were conducted between September 1 and December 1, 2015. In order to reduce the effect of publication bias, an attempt was made to locate the most complete collection of published and unpublished papers.

3.3.1 Electronic searches

Below we list details of the 27 electronic databases searched. As noted above, these databases included both published (e.g., ISI web of knowledge, PsycINFO) and unpublished reports (e.g., Dissertation Abstracts, EThOS) as well as reports from Latin‐American countries (e.g., Scientific Electronic Library Online – SciELO).

Table 2.

Electronic searches

|

Databases |

|---|

|

For each database, we ran pilot searches including the key terms described in Table 3. Four categories of key words were used, including: i) type of study; ii) type of intervention; iii) population; and iv) outcomes. The pilot searches were useful to adjust the terms, synonyms and wildcards as appropriate. They were also helpful in creating combinations of terms that capture relevant sets of studies in each database.

Table 3.

Key words for searches

|

Type of study |

Interventions |

Population |

Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Evaluation Effectiveness Intervention Program Programme Programme effectiveness Impact Effect Experimental evaluation Quasi‐experimental evaluation RCT Random evaluation Efficacy trial |

Disciplinary methods Token economy Classroom management program/ intervention/ strategies School management Early interventions School support projects Skills training |

Schoolchildren Pupils Children Adolescents School‐aged children Student Youth Adolescent Young people |

School exclusion Suspension Out‐of‐school suspension In‐school suspension Out‐of‐school exclusion In‐school exclusion Suspended Expelled Expulsion Outdoor suspension Stand‐down Exclusionary discipline Discipline |

We kept a record with the date of searches, number of reports found, number of reports retrieved, key terms included, synonyms, and wildcards used when appropriate. Further details of electronic searches are presented in Section 13.

3.3.2 Other resources searched

As planned, we contacted key authors requesting information on primary studies that could potentially be integrated in this systematic review and meta‐analysis. We also reviewed reference lists of previous primary studies or reviews related to the intervention/outcomes (e.g., Burrell, Zirbel, & Allen, 2003; Gottfredson, Cook, & Na, 2012; Johnson, 2012; Mytton, DiGuiseppi, Gough, Taylor, & Logan, 2006; Wilson, Tanner‐Smith, Lipsey, Steinka‐Fry, & Morrison, 2011).

3.4 DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

3.4.1 Selection of studies

Eligible studies met the following criteria:

Reported results of interventions from 1980 onwards

Tested the impact of a school‐based intervention on different types of exclusion (e.g., in‐school, out‐of‐school, expulsion)

Included students from primary and secondary school levels settled in mainstream schools

Based on an experimental design, where participants are randomly allocated treatment or control conditions

Reported statistical results for computed an effect size

3.4.2 Data extraction and management

Data extraction was the responsibility of two researchers (AC & SV). Descriptive data of all studies potentially includable in the meta‐analysis was extracted using the data collection instrument presented in Section 12.2. The instrument facilitated the extraction of the following information:

Bibliographical data (e.g., type of publication, year of publication, name of the publication, main author discipline)

Ethics (e.g. declaration of conflicts of interest, use of informed consent)

Research methods (e.g., type of design, units of randomisation, unit of analysis, variables used for matching)

Sample selection (e.g., methods to select sample, attrition)

Primary outcome coding (e.g., type of exclusion, duration of exclusion)

Secondary outcomes coding (e.g., internalising and externalising behaviours, name of the instrument used to measure the outcome data)

Base‐line measurements (e.g., source of data, quantitative measure of the primary outcome)

Programme delivery (e.g., programme deliverer, training, type of intervention, frequency of the intervention)

Post‐intervention and follow‐up measurement (e.g. official records, surveys)

Data for calculation on effect sizes

The same two researchers extracted data for effect‐size calculations. The process was carried out independently. In general, discrepancies were solved by agreement but when the information reported was contentious, we asked for input from the more senior members of the team (ME & DF). Details on the data extracted from each included report can be found in section 9.1, 9.2 and 9.3 of the present review.

When data for calculation of effect sizes was incomplete we used two different strategies. First, we tried to find more details in other sources (e.g., published protocols or reports). Secondly, the lead researcher or members of the research team were contacted regarding the additional data needed.

Endnote X7 software was used to manage references, citations and documents. Data extracted to characterise studies was inputted in STATA v.13 in order to produce inferential/descriptive statistics. Effect sizes were inputted in Version 3.0 of the Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis software.

3.4.3 Strategy to test inter‐rate reliability