Abstract

TFIID is a multiprotein complex composed of the TATA binding protein (TBP) and TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs). The binding of TFIID to the promoter is the first step of RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex assembly on protein-coding genes. Yeast (y) and human (h) TFIID complexes contain 10 to 13 TAFIIs. Biochemical studies suggested that the Drosophila (d) TFIID complexes contain only eight TAFIIs, leaving a number of yeast and human TAFIIs (e.g., hTAFII55, hTAFII30, and hTAFII18) without known Drosophila homologues. We demonstrate that Drosophila has not one but two hTAFII30 homologues, dTAFII16 and dTAFII24, which are encoded by two adjacent genes. These two genes are localized in a head-to-head orientation, and their 5′ extremities overlap. We show that these novel dTAFIIs are expressed and that they are both associated with TBP and other bona fide dTAFIIs in dTFIID complexes. dTAFII24, but not dTAFII16, was also found to be associated with the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) dGCN5. Thus, dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are functional homologues of hTAFII30, and this is the first demonstration that a TAFII-GCN5-HAT complex exists in Drosophila. The two dTAFIIs are differentially expressed during embryogenesis and can be detected in both nuclei and cytoplasm of the cells. These results together indicate that dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 may have similar but not identical functions.

Initiation of transcription of protein-encoding genes by RNA polymerase II requires transcription factor TFIID, which is comprised of the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and 10 to 12 TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs) (2, 40, 42). TFIID directs preinitiation complex assembly on both TATA-containing and TATA-less promoters. To date, most of the TFIID components from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and humans have been identified, partially characterized, and shown to be well conserved during evolution (2, 25, 42). However, despite intensive biochemical analysis and genetic studies of Drosophila melanogaster TFIID (dTFIID) (8, 22, 43, 47) several human and yeast TAFIIs have no known Drosophila homologues.

The different TAFII compositions of the distinct TFIID complexes appear to play key roles in the functional specificity of these complexes. A series of TAFIIs, designated core TAFIIs, may be present in all TFIID complexes, whereas other TAFIIs are only found in defined TFIID subpopulations, often detected in substoichiometric amounts compared to TBP and core TAFIIs (2–4, 6, 9, 15, 17). Recently, a novel human multiprotein complex has been characterized which contains neither TBP nor TBP-like factor but is composed of several TAFIIs and a number of other polypeptides (5, 45). This complex, called TBP-free TAFII-containing complex (TFTC), contains the GCN5 histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity, is able to direct preinitiation complex formation and initiation of transcription in in vitro transcription assays, and can mediate transcriptional activation by GAL-VP16 (5, 45).

Following the discovery of the TFTC, TAFIIs have also been identified in different other HAT complexes, such as TAFII90, TAFII68/61, TAFII60, TAFII25, and TAFII20/17 in the yeast SPT-ADA-GCN5 acetyltransferase (SAGA) complex (13), TAFII31, TAFII30, and TAFII20/15 in the human PCAF/GCN5 complex (30), and TAFII31 in the human SPT3-TAFII31-GCN5 acetyltransferase (STAGA) complex (26). The finding that coactivators of transcription contribute to HAT activity further strengthens the idea that histone acetylation and deacetylation can regulate gene activation (24, 46). Recent analyses have particularly shown that GCN5 not only displays a HAT activity but also is required for correct expression of various genes in yeast by catalyzing promoter-specific histone acetylation (7, 48) and chromatin remodelling (14). All TBP-free TAFII-HAT complexes, including SAGA, TFTC, PCAF/GCN5, and STAGA, contain a HAT belonging to the GCN5 family and can acetylate histone H3 in mononucleosomes (5, 13, 26, 30, 45). These data suggest that TAFII-GCN5-HAT complexes form transcriptional adapters able to interact with chromatin templates and to potentiate transcriptional activation. Differences in the polypeptide composition of the different TBP-free TAFII-HAT complexes (5) suggest that like TFIID, different subpopulations of TAFII-GCN5-HAT complexes may exist in the cell and may confer a broad range of regulatory capabilities in polymerase II transcription.

Human TAFII30 (hTAFII30) is present in about 50% of the hTFIID complexes (17). hTAFII30 interacts in vitro with activation function 2-containing region E of the human estrogen receptor (17). Moreover, not only are hTAFII30 and its yeast homologue yTAFII25 (21, 35) present in TFIID but also they were detected in all of the TBP-free TAFII-GCN5-HAT complexes (13, 26, 30, 45). Surprisingly, in spite of the fact that a functional homologue of human TAFII30 in yeast has been identified (21), to date no hTAFII30 homologue in Drosophila has yet been described (20). Moreover, previous biochemical studies suggested that the Drosophila TFIID complex contains only eight TAFIIs, including TAFII230, TAFII150, TAFII110, TAFII80, TAFII60, TAFII40, TAFII30α, and TAFII30β (8, 22, 43, 47), whereas human and yeast TFIIDs contain 10 to 12 subunits (2, 42). In this report we demonstrate the existence of two hTAFII30/yTAFII25 homologues in Drosophila, designated dTAFII16 and dTAFII24. These two dTAFIIs are encoded by two partially overlapping genes whose transcription is oriented in opposite directions. Furthermore we present evidence that both novel dTAFIIs are bona fide TAFIIs and that they are differentially expressed during Drosophila embryogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Poly(A)+ RNA preparation and cDNA library screening.

Preparation of poly(A)+ RNA from 0- to 9-h and 0- to 16-h embryos, the construction of cDNA libraries, and the screening of the cDNA libraries have been described (16, 44).

Immunization and antibody production.

To generate anti-dTAFII16 and anti-dTAFII24 polyclonal antibodies (PAbs), peptides (see Fig. 2) were synthesized, coupled to ovalbumin as a carrier protein, and used for immunization of rabbits. Rabbit sera were collected and purified on a SulfoLink column (Pierce), to which the synthesized peptides had been previously conjugated through the terminal cysteine of each peptide, according to manufacturer's instructions. Antibodies against GCN5 (38), dTBP, and dTAFIIs (10, 22, 23) were previously described.

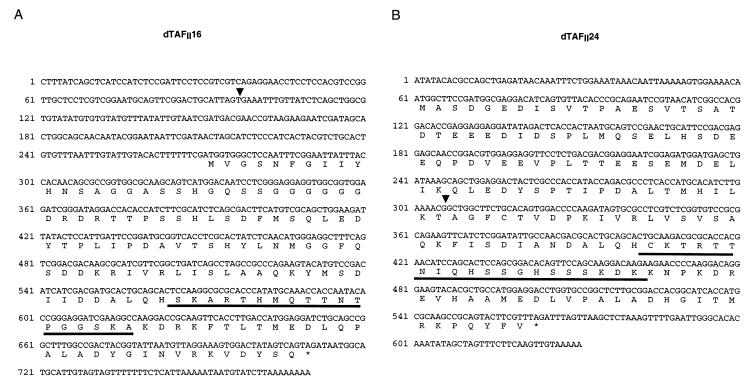

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the two novel dTAFIIs. (A) The dTAFII16 ORF extends from nucleotide 272 to 719. (B) The dTAFII24 ORF extends from nucleotide 61 to 562. Both transcripts were aligned with the genomic sequences, and the insertion points of the intronic sequences are indicated with an arrowhead. The peptide sequences which were used to generate PAbs are underlined in both amino acid sequences. (Accession numbers of the dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 cDNAs are AJ243837 and AJ243836, respectively.)

IP and Western blot analysis.

Routinely, 100 to 500 μl (approximately 500 μg) of the indicated protein fractions was immunoprecipitated with 50 μl of protein A-Sepharose (Pharmacia) and approximately 2 μg of the different antibodies (as indicated in the figures). Antibody–protein A-Sepharose-bound protein complexes were washed three times with immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2) containing 0.5 M KCl and twice with IP buffer containing 100 mM KCl. After the washing, 5 to 10 μl of beads was boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and protein was analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and probed with primary antibodies. The purified anti-dTAFII16 and anti-dTAFII24 antibodies were diluted 1,000-fold, the PAbs raised against dTAFII230, dTAFII110, dTAFII80, and dTAFII40 were diluted 3,000-fold, and the anti-dTBP antibodies were diluted 2,000-fold. Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (heavy plus light chain) specific antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) were used as secondary antibodies. Detection by an ECL kit (Amersham) was performed using standard methods.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization.

Wild-type Oregon R embryos in different developmental stages were prepared and fixed as previously described (44). Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes were synthesized in vitro by using dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 cDNAs inserted in BlueScript SK(+) vector (Stratagene Corp., La Jolla, Calif.) and T3 or T7 RNA polymerase. Before hybridization, the RNA probes were reduced in size by mild alkaline hydrolysis.

Immunochemistry.

Embryos were dechorionated in 3% bleach (Roth GMbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) and washed extensively in 0.1% Triton X-100 followed by deionized H2O. Fixation was performed by shaking the embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer with an equal volume of heptane. The embryos were then devitellinized by vigorous shaking in 1:1 heptane–0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS buffer, washed in PBS, treated with methanol for 60 s, and rehydrated in PBS containing 0.1% Tween and 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBTT). The embryos were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in PBTT containing 5% normal goat serum and 1% bovine serum albumin. Anti-TAFII16 and anti-TAFII24 antibodies were diluted 1:100 in the blocking solution and incubated with the embryos overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. After three washes in PBTT, the embryos were incubated for 60 min at room temperature with anti-rabbit Cy3 secondary antibodies diluted 1:400 in PBTT. The embryos were washed with PBS, treated for 90 min at room temperature with 0.4 mg of RNase A per ml in PBS, washed with PBS at room temperature with 5 mg of propidium iodide per ml, washed extensively with PBS, mounted in Vectashield embedding medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.), and examined under a Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany).

Immunostaining of polytene chromosomes was performed as described previously (33, 39) except that the anti-dTAFII antibodies were diluted 100-fold.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The accession numbers for the dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 cDNAs are AJ243837 and AJ243836, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification of two Drosophila genes encoding novel dTAFIIs.

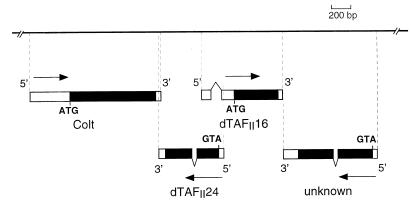

As a result of the isolation and nucleotide sequencing of the congested-like tracheae (colt) locus from Drosophila (16), we noticed that the genomic sequence located downstream from colt contained transcribed sequences whose products may correspond to two proteins displaying similarity to human TAFII30. To identify the putative dTAFII transcripts, the nucleotide sequences of previously isolated cDNA clones from the colt locus were determined and aligned with the genomic DNA sequence. As shown in Fig. 1, sequence analysis allowed us to classify these transcripts into four groups: (i) 10 cDNA clones originating from the colt gene, (ii) 2 cDNA clones which correspond to the dTAFII gene adjacent to colt and whose 3′ extremities partially overlap with the 3′ extremity of the colt transcript, (iii) 3 cDNAs representing a more distal dTAFII gene, and (iv) 9 cDNA clones representing a fourth gene that encodes a novel protein with a high content of hydrophobic amino acids. Comparison of the full-length cDNA sequences corresponding to both dTAFII genes showed that while the 3′ halves of both dTAFII coding sequences were relatively well conserved, their 5′ halves showed essentially no homology. Alignment of the two classes of dTAFII cDNA with the genomic DNA sequences revealed that they were synthesized from opposite strands, that the 5′ ends of both genes overlapped with each other, and that each dTAFII transcript was made of two exons (Fig. 1 and 2). Interestingly, the colt locus (second chromosome, 23A region) contains an unusually high number of genes. Transcripts from three of these genes partially overlap: the transcripts of both dTAFII genes overlap at their 5′ halves, and the 3′ extremity of the colt transcript has a 17-nucleotide overlap with the 3′ end of the adjacent dTAFII gene (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Map of the colt locus of D. melanogaster with the novel dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 genes. Localization of the two dTAFII genes together with an unknown gene encoding a novel protein (with a high content of hydrophobic amino acids) identified in the immediate vicinity of the colt gene are shown. The coding sequences of the different transcripts are indicated by solid boxes, and the noncoding transcribed regions are indicated by open boxes. The exon organization and the 5′ and 3′ orientation of the transcripts were determined from sequence analysis of cDNAs and from their alignment with the genomic DNA.

TAFII30 homologues from various species contain a highly conserved C-terminal domain.

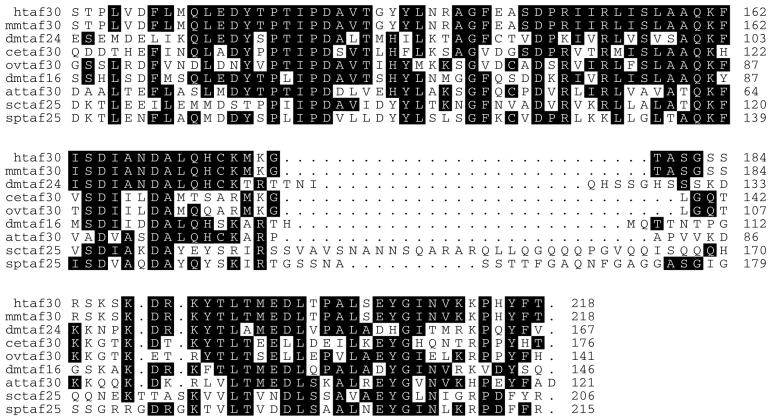

The two Drosophila TAFII proteins were named according to their apparent molecular weights in SDS-PAGE (see below). The more distal dTAFII gene in relation to the colt gene was designated dTAFII16, whereas the gene adjacent to colt was called dTAFII24 (Fig. 1 and 2). The dTAFII16 transcript contains an open reading frame (ORF) encoding a protein of 146 amino acids (Fig. 2A) with a molecular mass of 16,060 Da, which is in good agreement with its apparent molecular mass (see Fig. 4). The dTAFII24 transcript contains an ORF producing a protein of 167 amino acids (Fig. 2B) with a predicted molecular mass of 18,370 Da. However, the protein encoded by this gene migrates with an apparent molecular mass of ∼24 kDa (see Fig. 4). This is not unprecedented among the human and yeast homologues of dTAFII24, which all migrate at higher masses in SDS-PAGE than their predicted molecular masses (17, 21). The sequences of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 proteins were then used as query sequences in searches of different databases to find homologues. The result of this analysis confirmed that the two novel dTAFIIs are indeed homologous to each other and to human TAFII30 as originally hypothesized, but it also revealed the presence of several homologues in different species, including S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Arabidopsis thaliana, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Onchocerca volvulus. This comparison indicated that both dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 proteins are members of the TAFII30 family of proteins with an evolutionarily well conserved C-terminal domain (Fig. 3) and a divergent N-terminal moiety (data not shown). The C-terminal domains of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are 75% similar to each other and 77 and 75% similar to the core domain of hTAFII30, respectively (Fig. 3 and data not shown).

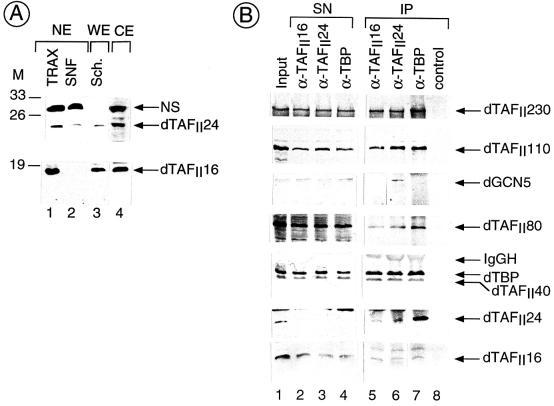

FIG. 4.

dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are bona fide TAFIIs. (A) Proteins extracted from either Drosophila embryos or Schneider cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a membrane. The blots were probed with affinity-purified anti-dTAFII16 antibodies (lower panel) or anti-dTAFII24 antibodies (upper panel). Drosophila embryo NE were prepared according to the procedures of either Kamakaka et al. (19) (SNF) or Sandaltzopoulos and Becker (34) (TRAX). Whole cell extract (WE) was prepared from Drosophila Schneider cells (Sch). Cytoplasmic extract (CE) was prepared according to Becker and Wu (1). Molecular mass markers (M) are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) TBP and several bona fide dTAFIIs coimmunoprecipitate with both dTAFII16 and dTAFII24, whereas dGCN5 coimmunoprecipitates only with dTAFII24. TRAX nuclear extract was immunoprecipitated with anti-dTAFII16 (α-dTAFII16), anti-dTAFII24 (α-dTAFII24), and anti-dTBP (α-dTBP) antibodies, as indicated. The input TRAX nuclear fraction (Input), the supernatant of the immunoprecipitations (SN), and the immunoprecipitated protein A-Sepharose-antibody bound proteins (IP) were resolved on a 10% (upper panels) and a 15% (two lower panels) SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred. The blots were then probed with antibodies raised against dTAFII230, dTAFII110, GCN5, dTAFII80, dTBP, dTAFII40, dTAFII24, and dTAFII16, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Both novel dTAFIIs, dTAFII16 and dTAFII24, are evolutionarily well conserved TAFIIs containing a highly conserved C-terminal region. TAFII coding sequences from various species were aligned using the ClustalX program (18). The one-letter amino acid code is used. TAFII sequences and their accession numbers are as follows: TAFII30, U13991; mouse (mm) TAFII30, AJ249987; S. cerevisiae (sc) TAFII25, Q12030; S. pombe (sp) TAFII25, spt:O60171; A. thaliana (at) TAFII15, spt:O04173; C. elegans (ce) TAFII30, spt:Q21172; O. volvulus (ov) TAFII30, GB_NEW:AI111274. The presence of three or more identical amino acids in all factors is indicated by a black background. Note that when at certain positions there are equal numbers (three or four) of two different amino acids they are not boxed by the program.

dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are both associated with TFIID, whereas dTAFII24 is also associated with the dGCN5 HAT.

To identify the proteins encoded by the two dTAFII transcripts, rabbit PAbs were raised against unique peptides derived from each of the dTAFIIs (Fig. 2) (see Materials and Methods). Western blots of nuclear proteins (NE) extracted from 0- to 6-h embryos (TRAX and SNF) (19, 34), cytoplasmic proteins from embryos (1), or total proteins from Drosophila Schneider cells were probed with either anti-dTAFII16 or anti-dTAFII24 PAbs (Fig. 4A). The anti-dTAFII16 PAb specifically recognized a polypeptide having an apparent molecular mass of about 16 kDa, and the anti-dTAFII24 PAb specifically recognized a protein species migrating around 24 kDa (Fig. 4A). These results demonstrate that the newly identified dTAFIIs are expressed during early Drosophila embryogenesis and in Schneider cells, indicating that the isolated cDNAs encode the predicted protein sequences (Fig. 4A). Note that both purified polyclonal sera cross-reacted with polypeptides other than the dTAFIIs on the Western blots, but these proteins were also recognized by the corresponding preimmune sera (Fig. 4A, and data not shown). Interestingly, dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 have been detected in both nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts (Fig. 4A, lane 1 and 4). Furthermore, dTAFII16 was detected only in the TRAX-type NE, not in the SNF-type NE (19, 34) (Fig. 4A, lower panel). As the TRAX-type NE is prepared by using a more stringent extraction procedure (34), this suggests that dTAFII16 may be more tightly associated with the chromatin than dTAFII24.

To determine whether the newly identified dTAFIIs are indeed bona fide TBP-associated factors, we investigated whether dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are associated with dTBP in the different immunopurified TBP-containing complexes. To this end we have carried out an IP experiment using an anti-dTBP PAb (22). The anti-TBP IP depleted all the dTAFII24 and about 50% of dTAFII16 from the input TRAX NE (Fig. 4B, compare lane 1 with 4), and both dTAFII24 and dTAFII16 were found to be associated with TBP (lane 7). Note that other bona fide dTAFIIs, such as dTAFII230, dTAFII110, dTAFII80, and dTAFII40, were also coimmunoprecipitated with dTBP (lane 7). When the purified antisera raised against either dTAFII24 or dTAFII16 were used as antibodies in the IP experiments, both antibodies coimmunoprecipitated dTBP as well as dTAFII230, dTAFII110, dTAFII80, and dTAFII40 from the TRAX NE (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 6). In contrast, in the control IP using only protein A-Sepharose, no TBP or dTAFIIs were detected (Fig. 4, lane 8). These results demonstrate unequivocally that the two newly identified dTAFIIs are associated with dTBP in dTFIID complexes.

Since the human and the yeast homologues of the two novel dTAFIIs have also been found in several TBP-free TAFII-GCN5-HAT-containing complexes (2), we tested whether the antisera raised against either dTAFII16 or dTAFII24 would also coimmunoprecipitate the Drosophila GCN5 HAT (38). Thus, we analyzed the protein complexes which were immunoprecipitated with either the anti-dTAFII16 or the anti-dTAFII24 PAb, as well as with the anti-dTBP PAb as a negative control, for the presence of dGCN5 by Western blot analysis using an anti-hGCN5 antibody that cross-reacts with the Drosophila protein (38). Interestingly, we found that the anti-dTAFII24 PAb, but neither the anti-dTAFII16 PAb nor the anti-dTBP PAb, coimmunoprecipitated dGCN5 (Fig. 4B, compare lane 6 with lanes 5 and 7), indicating that dTAFII24 is present in a novel Drosophila TAFII-GCN5-HAT complex as well as in dTFIID. These data also provide the first demonstration that a TAFII-GCN5-HAT complex exists in Drosophila.

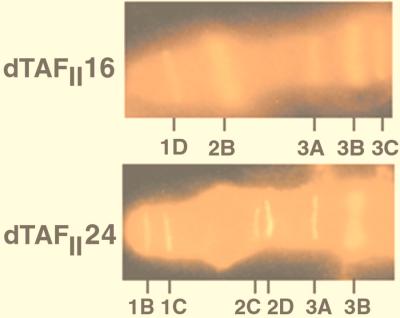

dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 do not always target the same set of genes.

If transcriptional selectivity can be achieved at the level of distinct TAFII-containing multiprotein complexes, then the different TAFII30 family members (dTAFII16 and dTAFII24) might be expected to be associated with different loci of the genome. Immunostainings of Drosophila salivary gland polytene chromosomes show that both dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are found to be located at a large number of loci (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Antibody stainings revealed that both dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are associated with a unique subset of loci. As shown by the localization of the binding sites of the two dTAFIIs on the distal region of the polytene X chromosome in wild-type strains, there are (i) loci which are stained by both anti-dTAFII16 and anti-dTAFII24 antibodies (i.e., puff sites 3A and 3B) and (ii) loci which are recognized only by either the anti-dTAFII16 (i.e., puff sites 1D, 2B, and 3C) or anti-dTAFII24 (i.e., puff sites 1B, 1C, 2C, and 2D) antibodies (Fig. 5 and data not shown). These observations further suggest that these two novel dTAFIIs have not identical but overlapping functions and that functionally different TAFII-containing complexes exist in Drosophila.

FIG. 5.

Localization of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 proteins on the distal region of Drosophila X chromosome. Immunostaining of polytene X chromosome from wild-type larvae (Oregon R) was done with antibodies raised against dTAFII16 (upper panel) and dTAFII24 (lower panel) and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies. The labeled regions of chromosome X are indicated under both panels.

dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are differentially expressed during Drosophila embryogenesis.

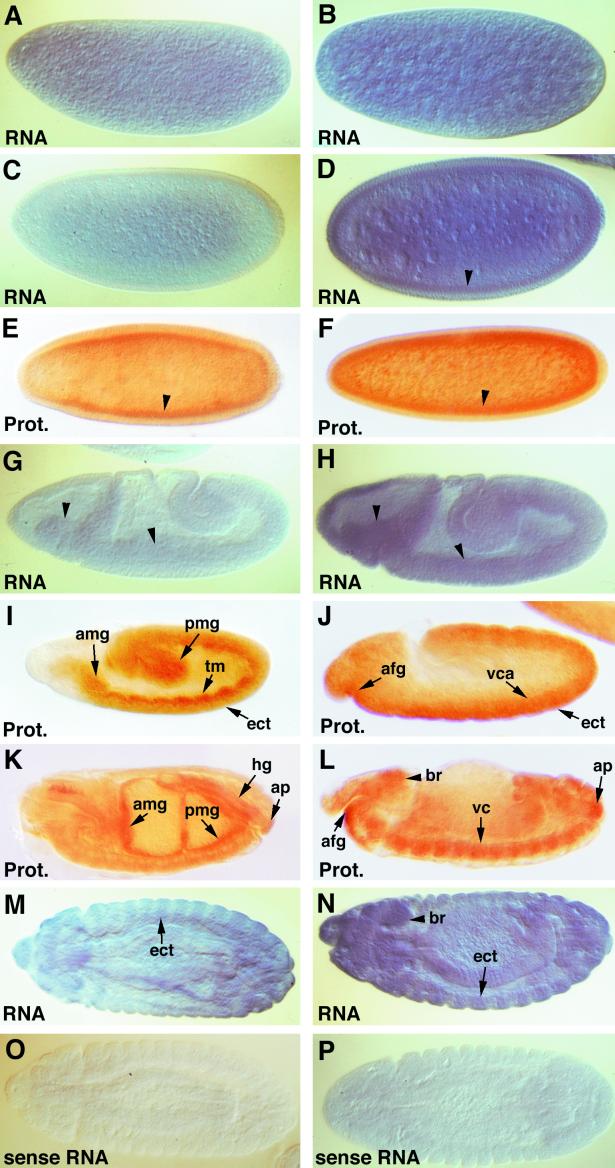

Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA extracted from embryonic stages using either cDNA probes specific for each dTAFII gene or a genomic fragment encompassing both dTAFII genes showed that dTAFII16 produces a 0.95-kb poly(A)+ RNA transcript whereas dTAFII24 produces a 0.75-kb poly(A)+ RNA transcript (data not shown) and that both classes of transcripts are produced during embryogenesis. We investigated the spatiotemporal expression of both dTAFII genes by either in situ hybridization of whole-mount embryos using digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes (and sense RNA probes as controls) or immunocytochemistry using purified antibodies raised against dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 proteins. For both dTAFII genes, the developmental profile of protein expression follows that of RNA expression (Fig. 6 and data not shown). We found that at all embryonic stages examined, the level of RNA and protein expression of dTAFII24 is constantly higher than that of dTAFII16, and we also observed that maternally derived dTAFII24 and dTAFII16 gene products (Fig. 6A to F) are present when the embryos undergo rapid nuclear divisions during the syncytial preblastoderm stage. Similarly, ubiquitous distribution of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 transcripts was detected during early germ band elongation with significantly higher levels of dTAFII24 RNA than of dTAFII16 (compare Fig. 6G and H). The differences in the expression patterns of dTAFII genes appear at the end of germ band elongation, when different embryonic tissue primordia are specified. At stage 9, the dTAFII16 protein is preferentially synthesized in the mesodermal layer and in the midgut primordia (Fig. 6I) while the highest dTAFII24 level is detected within the ectoderm, the ventral chord, and the anterior foregut primordium (Fig. 6J). The mesoderm-specific expression of dTAFII16 persists in later stages of development and at its highest level was detected in midgut, hindgut (Fig. 6K), and differentiating somatic muscle fibers (Fig. 7C). At the same time dTAFII24 is preferentially expressed in the foregut (Fig. 6L and 7D), the proventriculus (Fig. 7D), and the central nervous system (Fig. 6L and N and 7D). In addition, both genes are coexpressed in the lateral epidermis (Fig. 6M and N) and the anal plate (Fig. 6K and L). The finding that the dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 genes display different levels of transcription and tissue specificities during embryogenesis suggests that their transcription is regulated by separate regulatory elements and may thus have different functions.

FIG. 6.

Expression of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 during embryonic development. Whole-mount embryos were hybridized with dTAFII16 (A, C, G, and M) and dTAFII24 (B, D, H, and N) antisense single-stranded RNA probes labeled by incorporation of dioxigenin-11-dUTP, as well as with dTAFII16 (O) and dTAFII24 (P) sense probe. The dTAFII16 (E, I, and K) and dTAFII24 (F, J, and L) proteins were detected with purified PAbs and visualized using the ABC Elite horse radish peroxidase detection kit (Vector Laboratories). All embryos are oriented to the left and viewed laterally unless otherwise indicated. (A and B) Evenly distributed dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 transcripts in early cleavage stage embryos, ∼45 to 70 min after egg deposition. (C to F) Blastoderm embryos, ∼120 to 130 min after egg deposition. Arrowheads indicate an accumulation of dTAFII RNA (D) and proteins (E and F) close the surface. (G and H) During germ band extension, ∼260 to 320 min after egg deposition, both dTAFII transcripts are seen in the neuroectodermal and the mesodermal layers of the head and the trunk (arrowheads). (I and J) Differential expression of dTAFII proteins in embryos at the end of germ band extension, 190 to 220 min after egg deposition. The dTAFII16 protein (I) was highly expressed in the trunk mesoderm (tm) and the anterior (amg) and the posterior midgut (pmg) primordia. In contrast, the highest expression of dTAFII24 (J) appeared in the anterior foregut (afg) and the ectodermal cells (ect) and in anlagen of the ventral cord (vca). (K and L) Differential accumulation of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 proteins after germ band retraction. High levels of dTAFII16 (K) was detected in the visceral musculature of the midgut (amg and pmg) and the hindgut (hg) while dTAFII24 (L) was preferentially expressed in the anterior foregut (afg) and in the central nervous system (br and vc). Both proteins are coexpressed in the anal plate (ap). (M, N, O, and P) Dorsal (M, O, and P) and lateral (N) views of embryos at the time of completion of germ band retraction, ∼620 to 750 min after egg deposition. Arrows in panels M and N show high transcript levels in the lateral epidermis (ect) and in the brain (br).

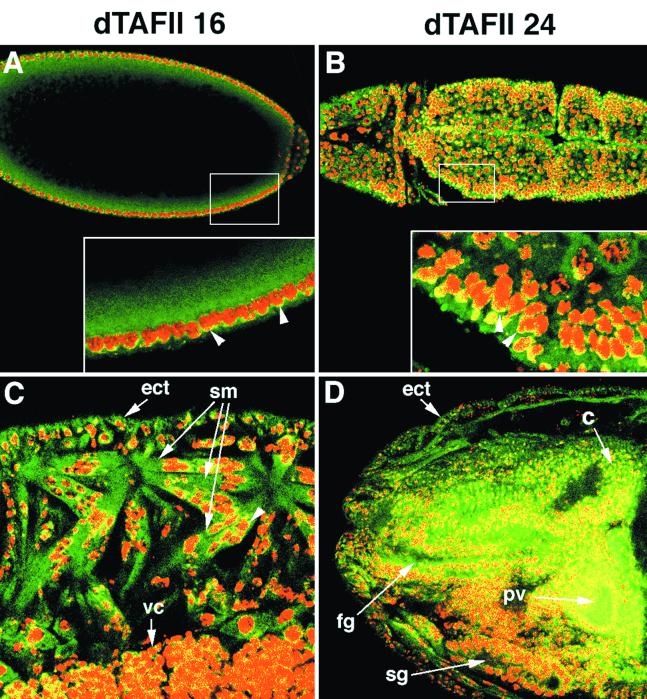

FIG. 7.

Intracellular distribution of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 in Drosophila embryos. Confocal scanning micrographs showing localization of dTAFIIs labeled with purified anti-dTAFII16 (A and C) or dTAFII24 (B and D) rabbit antibodies and secondary anti-rabbit-Cy3 antibody (green) and of DNA labeled with propidium iodide (red). (A) In the early preblastoderm embryos, dTAFII16 is predominantly distributed in the cytoplasm. (B) During germ band extension, a significant amount of dTAFII24 is accumulated in the cytoplasm of ectodermal cells. Both dTAFII proteins are also detected in the periphery of nuclei (yellow; arrowheads in insets in A and B). (C) In late-stage embryos, dTAFII16 localizes to the cytoplasm of ectodermal cells (ect) and syncytial muscle fibers (sm) with nuclear staining of the protein at the internal rim of the myocyte nuclei (yellow; an example is indicated by an arrowhead). A scattered nuclear dTAFII16 staining (yellow) appears also in the neural cells of the ventral chord (vc). (D) After germ band retraction dTAFII24 is essentially expressed in the ectoderm (ect) and central nervous system (c) as well as in the foregut (fg) and proventriculus (pv) primordium and moderately expressed in the salivary gland (sg). In these tissues the dTAFII24 protein localizes to the cytoplasm (green) and to the periphery of the nuclei (yellow).

To monitor the intracellular distribution of the dTAFII24 and dTAFII16 proteins, we used confocal microscopy (Fig. 7). Confocal scans were performed on whole-mount preparations of wild-type embryos double-stained with propidium iodide to visualize DNA (red) and fluorescent antibodies to visualize the dTAFII proteins (green). From early preblastoderm stages (Fig. 7A) up to germ band elongation (Fig. 7B), we found that both proteins were essentially distributed throughout the cytoplasm with a higher concentration around the nuclei and were also detected at the periphery of the nuclei (Fig. 7A and B). Similar intracellular distribution was seen in different embryonic tissues after germ band retraction. For example, expression of dTAFII16 was predominant in the cytoplasm of syncytial muscle fibers (Fig. 7C) and detected at a lower level in the periphery of the myoblast nuclei (Fig. 7C). During late embryogenesis, a weak scattered nuclear staining of dTAFII16 in the ventral chord (Fig. 7C) and a relatively stronger nuclear expression of dTAFII24 in the brain (Fig. 7D) were also detected. These data, together with the observation that full-length dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 proteins were detected in both nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts (Fig. 4A), indicate that dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 proteins display a bicompartmental cellular distribution occurring both in the cytoplasm and also in the nuclei, where they seem to play a role in the transcriptional activity of the different TAFII-containing complexes.

DISCUSSION

Two homologue dTAFIIs appear by gene duplication to have similar but not identical functions.

Initial studies describing TFIID complexes from various species suggested that their complexity may be higher in yeast and vertebrates than in Drosophila. The recent progress made in the sequencing of the Drosophila genome prompted us to look more carefully for TAFII homologues. Through this analysis we discovered that Drosophila contains not one but two hTAFII30 homologues. In this study we have demonstrated that these two newly identified dTAFII genes, dTAFII16 and dTAFII24, are transcribed and expressed throughout embryonic development.

Extensive searches in different databases for homologue sequences revealed that to date, Drosophila is the only organism known to have two different TAFII30 type factors (Fig. 3). In the genomes of S. cerevisiae and C. elegans, for which the entire genome sequence has been recently completed, only one TAFII30 homologue has been found for each (scTAFII25 and ceTAFII30 [Fig. 3]). The occurrence of two TAFII30-related genes in the Drosophila genome indicates that they have arisen through a relatively complex mechanism of duplication, resulting in an inverted orientation of the duplicate genes with partial overlapping of their 5′ regions. As indicated by the overlapping of the dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 gene structure, the different positions of the intron located in each of these genes, and the divergence of the encoded proteins with conserved C-terminal moieties and divergent N-terminal moieties, we can postulate that the duplication of the dTAFII genes occurred early in arthropod ancestry. Further analysis of the genomic organization of these genes in other invertebrates species will shed light on the origin of their duplication.

The organization of both genes is relatively unusual, with overlapping of their putative promoter and 5′ regions. In particular, the promoter region of the dTAFII16 gene is found on the opposite strand within the dTAFII24 coding sequence, while the promoter region of dTAFII24 is located within the 5′ untranslated region of the second exon of dTAFII16 (Fig. 1). Moreover, the putative promoter regions show no or very little homology, suggesting different mechanisms of regulation for each gene. Interestingly, the overlap in the 5′ regions of both transcripts, which covers at least 128 nucleotides, does not prevent either the transcription of the dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 genes or the translation of their transcripts into proteins.

Surprisingly, the full-length dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 proteins are not more similar to each other (48% identity) than they are to hTAFII30 (54% identity between dTAFII16 and hTAFII30 and 48% identity between dTAFII24 and hTAFII30). Furthermore, dTAFII16 displays a higher sequence similarity to the other members of the TAFII30 family than dTAFII24. This sequence divergence suggests that dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 have different functions and that their functions have been subject to different evolutionary constraints. While the dTAFII16 function may be similar in yeasts and humans, dTAFII24 may be important for a function(s) that tolerates more diversity.

In the classical model for the evolution of duplicate genes, one member of the duplicated pair usually degenerates within a few million years by accumulating deleterious mutations, while the other duplicate retains the original function. This model further predicts that on rare occasions, one duplicate may acquire a new adaptive function, resulting in the preservation of both members of the pair, one having the new function and the other retaining the old (references 12, 29, 31, and 32 and references therein). However, empirical data suggest that a much greater proportion of gene duplication is preserved than is predicted by the classical model. Alternatively, complementary degenerative mutations in different regulatory elements of duplicated genes can facilitate the preservation of both duplicates, thereby increasing long-term opportunities for the evolution of new gene functions (11). For a newly duplicated paralog, survival depends on the outcome of the race between entropic decay and chance acquisition of an advantageous regulatory mutation (37). Duplicated genes persist only if mutations create new and essential protein functions, an event that is predicted to occur rarely (28). Our analysis of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 gene expression and our studies on the distribution of both dTAFIIs in different multiprotein complexes support a mechanism of evolution involving subfunctionalization rather than the acquisition of a totally novel function by one of the dTAFIIs. In particular, we have found that both newly identified dTAFII genes exhibit similar expression during early embryogenesis and a more restricted pattern of expression during late embryogenesis that is nearly complementary. At this stage, the dTAFII16 protein is predominantly found in muscle cells whereas the dTAFII24 protein is more strongly expressed in the foregut and midgut.

Different dTAFII16- and dTAFII24-containing multiprotein complexes with distinct functions.

When dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are expressed simultaneously in cells, like in 0- to 6-h embryos, both proteins were found to be associated with TBP and a number of other bona fide dTAFIIs, demonstrating that they are both present in TFIID complexes. Since IP using an anti-dTAFII16 antibody coimmunoprecipitates dTAFII24 and vice versa, these results suggest that both dTAFIIs can be present in the same dTFIID complex at the same time. Alternatively, as TFIID complexes have been shown to dimerize when not bound to DNA (41), it is also conceivable that in a given dTFIID the presence of dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 is mutually exclusive but they can be found in the coimmunoprecipitations because a dTAFII16-containing TFIID could dimerize with a dTAFII24-containing TFIID. Moreover, since both hTAFII30 and yTAFII25 were shown to bind to themselves (17, 21), it is possible that dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 behave similarly and thus may participate in the dimerization of different dTFIIDs. During development there are cells where only one of the two dTAFIIs is expressed; therefore, the presence of the two dTAFIIs in different complexes is more likely.

Interestingly, our studies showed that dTAFII24, but not dTAFII16, can be recovered in association with the dGCN5 HAT, suggesting that dTAFII24 has functional homology with hTAFII30 and yTAFII25. This result suggests that a Drosophila HAT complex exists that may be equivalent to the yeast SAGA or human TFTC, hPCAF/GCN5, and hSTAGA complexes. Moreover, the preferential association of dTAFII24 with the GCN5 HAT complex further suggests that each dTAFII protein carries out a defined function, with dTAFII24 being present in both TFIID and Drosophila TAFII-GCN5 complexes whereas dTAFII16 is only a component of dTFIID. The occurrence of distinct dTAFII16- and dTAFII24-containing multiprotein complexes in Drosophila cells suggests that in Drosophila, similar to mammalian cells, distinct functionally different TAFII-containing complexes exist (2, 5). Alternatively, it is possible that the dTAFII16 protein is incorporated into only a very small number of dTAFII-GCN5 complexes, which would remain undetectable under the conditions used in our studies. The distinct dTAFII16- and dTAFII24-containing complexes may have different affinities for the chromatin, since under less stringent conditions only the dTAFII24-containing complexes could be recovered from nuclei (Fig. 4A), further suggesting differential roles for the dTAFII16- and dTAFII24-containing complexes. Moreover, the observation that dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 are not always associated with the same transcriptionally active loci on polytene chromosomes indicates that the different dTAFII16- and dTAFII24-containing complexes have distinct functions in gene regulation.

The finding that the two dTAFIIs have different spatiotemporal expression levels, or eventually are not expressed at all, during embryogenesis suggests that (i) the composition of the different TFIID and TAFII-GCN5 complexes may change during development, (ii) the functions of these complexes may vary according to the promoter to which they become recruited, (iii) there may be gene regulatory pathways which require either dTAFII16 or dTAFII24, and (iv) there may be cells which can function without dTAFII16 and dTAFII24. These observations are in good agreement with our recent results showing that in murine F9 cells TAFII30 is required for cell cycle progression and parietal endodermal differentiation, but not for primitive endodermal differentiation (27). Thus, in metazoan organisms TAFIIs belonging to the TAFII30 family may be dispensable, but they are required for cells undergoing either rapid cell division or specific developmental differentiation programs. Moreover, the observation that in several different cell types dTAFIIs can be found in the cytoplasm raises new questions about the role of TAFIIs in other functions than those strictly restricted to the nucleus. In agreement with our finding, a fission yeast TAFII has recently been found to participate in nucleocytoplasmic transport of mRNAs (36). Further genetic and biochemical studies will now be required in order to analyze the functions of these two newly identified dTAFIIs, to help further our understanding of the functional differences between dTAFII16 and dTAFII24 during the regulation of polymerase II transcription, and to analyze their potential new functions in the context of an intact organism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to E. Scheer and R. Schmitt for excellent technical assistance, to G. Duval for generating the anti-dTAFII16 and anti-dTAFII24 PAbs, to Y. Nakatani and R. Tjian for antibodies, to P. B. Becker and K. P. Nightingale for Drosophila extracts, and to F. Müller and B. Bell for critically reading the manuscript. We also thank P. Eberling for peptide synthesis, the cell culture group for providing Schneider cells, F. Ruffenach for oligonucleotide synthesis, and R. Buchert and J. M. Lafontaine for preparing the figures.

S.G. was supported by a fellowship from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), S.G. and E.N. were supported by a grant from the University of Oslo, Center of Medical Studies, Moscow, Russia, and D.B.K. was supported by a Marie Curie fellowship from the European Community. This work was supported by funds from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the CNRS, the Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, the Human Frontier Science Program, and the Commission of the European Union (contracts CII*-CT92-0109, BMH1-94-1572, and BIO4-CT95-0202), the Swiss Cancer League, and the International Office of the Bundesministerium für Bildung, Forschung und Technologie (contract INI-316).

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker P B, Wu C. Cell-free system for assembly of transcriptionally repressed chromatin from Drosophila embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2241–2249. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell B, Tora L. Regulation of gene expression by multiple forms of TFIID and other novel TAFII-containing complexes. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246:11–19. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertolotti A, Lutz Y, Heard D J, Chambon P, Tora L. hTAFII68, a novel RNA/ssDNA-binding protein with homology to the pro-oncoproteins TLS/FUS and EWS is associated with both TFIID and RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 1996;15:5022–5031. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertolotti A, Melot T, Acker J, Vigneron M, Delattre O, Tora L. EWS, but not EWS-FLI-1, is associated with both TFIID and RNA polymerase II: interactions between two members of the TET family, EWS and hTAFII68, and subunits of TFIID and RNA polymerase II complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1489–1497. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand M, Yamamoto K, Staub A, Tora L. Identification of TATA-binding protein-free TAFII-containing complex subunits suggests a role in nucleosome acetylation and signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18285–18289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brou C, Chaudhary S, Davidson I, Lutz Y, Wu J, Egly J M, Tora L, Chambon P. Distinct TFIID complexes mediate the effect of different transcriptional activators. EMBO J. 1993;12:489–499. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Candau R, Zhou J X, Allis C D, Berger S L. Histone acetyltransferase activity and interaction with ADA2 are critical for GCN5 function in vivo. EMBO J. 1997;16:555–565. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J L, Attardi L D, Verrijzer C P, Yokomori K, Tjian R. Assembly of recombinant TFIID reveals differential coactivator requirements for distinct transcriptional activators. Cell. 1994;79:93–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dikstein R, Zhou S, Tjian R. Human TAFII105 is a cell type-specific TFIID subunit related to hTAFII130. Cell. 1996;87:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dynlacht B D, Weinzierl R O, Admon A, Tjian R. The dTAFII80 subunit of Drosophila TFIID contains beta-transducin repeats. Nature. 1993;363:176–179. doi: 10.1038/363176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Force A, Lynch M, Pickett F B, Amores A, Yan Y L, Postlethwait J. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–1545. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganfornina M D, Sanchez D. Generation of evolutionary novelty by functional shift. Bioessays. 1999;21:432–439. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199905)21:5<432::AID-BIES10>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant P A, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant M G, Steger D J, Reese J C, Yates J R, Workman J L. A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell. 1998;94:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregory P D, Schmid A, Zavari M, Lui L, Berger S L, Horz W. Absence of Gcn5 HAT activity defines a novel state in the opening of chromatin at the PHO5 promoter in yeast. Mol Cell. 1998;1:495–505. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen S K, Tjian R. TAFs and TFIIA mediate differential utilization of the tandem Adh promoters. Cell. 1995;82:565–575. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartenstein K, Sinha P, Mishra A, Schenkel H, Torok I, Mechler B M. The congested-like tracheae gene of Drosophila melanogaster encodes a member of the mitochondrial carrier family required for gas-filling of the tracheal system and expansion of the wings after eclosion. Genetics. 1997;147:1755–1768. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.4.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacq X, Brou C, Lutz Y, Davidson I, Chambon P, Tora L. Human TAFII30 is present in a distinct TFIID complex and is required for transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor. Cell. 1994;79:107–117. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeanmougin F, Thompson J D, Gouy M, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:403–405. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamakaka R T, Tyree C M, Kadonaga J T. Accurate and efficient RNA polymerase II transcription with a soluble nuclear fraction derived from Drosophila embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1024–1028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kazantsev A, Mu D, Nichols A F, Zhao X, Linn S, Sancar A. Functional complementation of xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group E by replication protein A in an in vitro system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5014–5018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klebanow E R, Poon D, Zhou S, Weil P A. Isolation and characterization of TAF25, an essential yeast gene that encodes an RNA polymerase II-specific TATA-binding protein-associated factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13706–13715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokubo T, Gong D-W, Wootton J C, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G, Nakatani Y. Molecular cloning of Drosophila TFIID subunits. Nature. 1994;367:484–487. doi: 10.1038/367484a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kokubo T, Gong D W, Yamashita S, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G, Nakatani Y. Drosophila 230-kD TFIID subunit, a functional homolog of the human cell cycle gene product, negatively regulates DNA binding of the TATA box-binding subunit of TFIID. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1033–1046. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo M H, Allis C D. Roles of histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases in gene regulation. Bioessays. 1998;20:615–626. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<615::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee T I, Young R A. Regulation of gene expression by TBP-associated proteins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1398–1408. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez E, Kundu T K, Fu J, Roeder R G. A human SPT3-TAFII31-GCN5-L acetylase complex distinct from transcription factor IID. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23781–23785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metzger D, Scheer E, Soldatov A, Tora L. Mammalian TAF(II)30 is required for cell cycle progression and specific cellular differentiation programmes. EMBO J. 1999;18:4823–4834. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nadeau J H, Sankoff D. Comparable rates of gene loss and functional divergence after genome duplications early in vertebrate evolution. Genetics. 1997;147:1259–1266. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.3.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nei M, Roychoudhury A K. Probability of fixation and mean fixation time of an overdominant mutation. Genetics. 1973;74:371–380. doi: 10.1093/genetics/74.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogryzko V V, Kotani T, Zhang X, Schlitz R L, Howard T, Yang X J, Howard B H, Qin J, Nakatani Y. Histone-like TAFs within the PCAF histone acetylase complex. Cell. 1998;94:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohno S. Patterns in genome evolution. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:911–914. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90013-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohno S, Wolf U, Atkin N B. Evolution from fish to mammals by gene duplication. Hereditas. 1968;59:169–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1968.tb02169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Platero J S, Sharp E J, Adler P N, Eissenberg J C. In vivo assay for protein-protein interactions using Drosophila chromosomes. Chromosoma. 1996;104:393–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00352263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandaltzopoulos R, Becker P B. Analysis of protein-DNA interaction by solid-phase footprinting. Methods Mol Cell Biol. 1995;5:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders S L, Klebanow E R, Weil P A. TAF25p, a non-histone-like subunit of TFIID and SAGA complexes, is essential for total mRNA gene transcription in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18847–18850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibuya T, Tsuneyoshi S, Azad A K, Urushiyama S, Ohshima Y, Tani T. Characterization of the ptr6(+) gene in fission yeast. A possible involvement of a transcriptional coactivator TAFII in nucleocytoplasmic transport of mRNA. Genetics. 1999;152:869–880. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidow A. Gen(om)e duplications in the evolution of early vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:715–722. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith E R, Belote J M, Schiltz R L, Yang X J, Moore P A, Berger S L, Nakatani Y, Allis C D. Cloning of Drosophila GCN5: conserved features among metazoan GCN5 family members. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2948–2954. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soldatov A, Nabirochkina E, Georgieva S, Belenkaja T, Georgiev P. TAFII40 protein is encoded by the e(y)1 gene: biological consequences of mutations. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3769–3778. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Struhl K, Moqtaderi Z. The TAFs in the HAT. Cell. 1998;94:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taggart A K, Pugh B F. Dimerization of TFIID when not bound to DNA. Science. 1996;272:1331–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tansey W P, Herr W. TAFs: guilt by association? Cell. 1997;88:729–732. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81916-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tjian R, Maniatis T. Transcriptional activation: a complex puzzle with few easy pieces. Cell. 1994;77:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torok I, Strand D, Schmitt R, Tick G, Torok T, Kiss I, Mechler B M. The overgrown hematopoietic organs-31 tumor suppressor gene of Drosophila encodes an Importin-like protein accumulating in the nucleus at the onset of mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1473–1489. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wieczorek E, Brand M, Jacq X, Tora L. Function of TAF(II)-containing complex without TBP in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nature. 1998;393:187–191. doi: 10.1038/30283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Workman J L, Kingston R E. Alteration of nucleosome structure as a mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:545–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yokomori K, Chen J L, Admon A, Zhou S, Tjian R. Molecular cloning and characterization of dTAFII30 alpha and dTAFII30 beta: two small subunits of Drosophila TFIID. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2587–2597. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W, Bone J R, Edmondson D G, Turner B M, Roth S Y. Essential and redundant functions of histone acetylation revealed by mutation of target lysines and loss of the Gcn5p acetyltransferase. EMBO J. 1998;17:3155–3167. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]