Abstract

Activation of the macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) induces the expression of gene products involved in host defense, among them type 2 nitric oxide synthase. Treatment of cells with 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15dPGJ2) inhibited the LPS- and IFN-γ-dependent synthesis of NO, a process that was not antagonized by similar concentrations of prostaglandin J2, prostaglandin E2, or rosiglitazone, a peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor γ ligand. Incubation of activated macrophages with 15dPGJ2 inhibited the degradation of IκBα and IκBβ and increased their levels in the nuclei. NF-κB activity, as well as the transcription of NF-κB-dependent genes, such as those encoding type 2 nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase 2, was impaired under these conditions. Analysis of the steps leading to IκB phosphorylation showed an inhibition of IκB kinase by 15dPGJ2 in cells treated with LPS and IFN-γ, resulting in an impaired phosphorylation of IκBα, at least in the serine 32 residue required for targeting and degradation of this protein. Incubation of partially purified activated IκB kinase with 2 μM 15dPGJ2 reduced by 83% the phosphorylation in serine 32 of IκBα, suggesting that this prostaglandin exerts direct inhibitory effects on the activity of the IκB kinase complex. These results show rapid actions of 15dPGJ2, independent of peroxisomal proliferator receptor γ activation, in macrophages challenged with low doses of LPS and IFN-γ.

Macrophage activation in response to proinflammatory cytokines and bacterial cell wall products constitutes a key component of the immune response (23, 31, 50). Resolution of the process occurs after removal of the proinflammatory stimuli and through the action of negative regulators of the activation-signaling pathways, among them interleukin-10 (IL-10), IL-13, alpha/beta interferons (IFN-α/β), and more recently several cyclopentenone prostaglandins (PGs) (8, 21, 35, 36, 49). In particular, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15dPGJ2) has been shown to exert important anti-inflammatory effects on several cell types such as monocytes/macrophages and microglia (4, 16, 35, 36). Controversy exists about the identification of intracellular targets involved in the mechanism of action of cyclopentenone PGs: some of these effects have been explained through the transcriptional inhibition exerted by 15dPGJ2-activated peroxisome proliferator receptor gamma (PPARγ) (12, 14, 36, 39); however, other data suggest a main contribution of PPARγ-independent mechanisms on the anti-inflammatory action of this PG, in view of the lack of effect of synthetic PPARγ ligands such as thiazolidinediones (17, 35).

It has been shown that 15dPGJ2 inhibits the expression of genes requiring the activation of the transcription factors NF-κB, AP-1, and Stat1 (17, 35, 36), which are involved in the induction of several enzymes participating in the development of the inflammatory process, such as type 2 nitric oxide synthase (NOS-2) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) (7, 42, 51). In macrophages, activated NF-κB complexes are composed mainly of p50 and p65 subunits that translocate to the nucleus in response to cell stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and proinflammatory cytokines (13, 45, 48). This activation of NF-κB requires phosphorylation by IκB kinase (IKK) of IκB proteins in specific serine residues that target these proteins for ubiquitin conjugation and degradation by the 26S proteasome (26, 45). The IKK complex contains two catalytic subunits, IKK1 and IKK2, and a regulatory subunit termed NF-κB essential modulator (10, 54, 56). In turn, activation of IKK is mediated by phosphorylation through NF-κB-inducing kinase, which acts preferentially over IKK1, and MEK kinase 1 (MEKK1), which phosphorylates IKK2 (6, 30). Biochemical and genetic data indicate that IKK1 and IKK2, despite the sequence similarity, have different functions (15, 55). IKK1 participates in differentiation of various cell types (20), whereas IKK2 is involved in LPS signaling in monocytes/macrophages and in general the response to proinflammatory stimuli (34, 55). IKK2 is rapidly activated after cell challenge with LPS, IL-1β, or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and progressively undergoes phosphorylation at multiple serine residues that decreases the kinase activity and therefore contributes to the transient activation of this enzyme (6). In this regard, we have investigated the possibility of early effects of 15dPGJ2 on LPS and IFN-γ (collectively termed LPS/IFN-γ) cooperative signaling in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Our data show that treatment of macrophages with 15dPGJ2 results in a significant inhibition of IKK2 activity. As a result, the phosphorylation of IκBα and the degradation of IκBα and IκBβ are inhibited, causing a partial inhibition of NF-κB activity. Accordingly, the expression of genes requiring NF-κB activation is significantly impaired by this mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Reagents were from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany), and Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Antibodies and glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Anti-phospho-(Ser32)κBα antibody (Ab) was from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). Electrophoresis equipment and reagents were from Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.) and Amersham (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). PGs were from Cayman (Ann Arbor, Mich.). Serum and media were from BioWhittaker (Walkersville, Md.).

Cell culture.

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at 6 × 104 to 8 × 104/cm2 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and antibiotics (50 μg each of penicillin, streptomycin, and gentamicin per ml). After 2 days, the cell layers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and the culture medium was replaced by phenol red-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.5 mM arginine and 0.5% FCS, followed by the addition of the indicated stimuli. PGs and rosiglitazone were added 5 min prior to activation with LPS and IFN-γ.

Plasmid constructs and preparation.

The (κB)3ConA.CAT plasmid construct, which contains three copies of the κB motif from the human immunodeficiency virus long-terminal repeat enhancer with the conalbumin A promoter, was used to measure κB transactivation capacity (8, 9, 48). The ConA.CAT vector, lacking the κB tandem, was used as a control. A 1-kb fragment corresponding to the 5′-flanking region of the NOS-2 gene fused to a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter [p2iNOS(+,+).CAT vector] and the same vector with mutated κB sequences corresponding to nucleotides −971 to −961 and −85 to −75 [p2iNOS(−,−).CAT] were also used. Plasmid kSV2.CAT was used as a reference for efficiency of the transfection (42, 48). Plasmids were purified using EndoFree columns (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Bacterial expression and purification of GST fusion proteins.

GST-IκBα(1-317) was from Santa Cruz. GST-IκBα(1-54) and GST-IκBα(1-54) mutated from Ser32/36 to Ala32/36 (GST-IκBαS/A) were expressed in the DH5αF′ strain of Escherichia coli as described elsewhere (19, 44), and the fusion proteins were purified on a glutathione-Sepharose 4B column (Pharmacia Biotech).

Preparation of cytosolic and nuclear extracts.

Cells (1.5 × 106) were washed with PBS and collected by centrifugation. Cell pellets were homogenized with 100 μl of buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin [2 μg/ml], leupeptin [10 μg/ml], Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone [TLCK; 2 μg/ml], 5 mM NaF, 1 mM NaVO4, 10 mM Na2MoO4). After 10 min at 4°C, Nonidet P-40 was added to reach a 0.5% concentration. The tubes were gently vortexed for 15 s, and nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 15 min (9, 40). The supernatants were stored at −80°C (cytosolic extracts); the pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of buffer A supplemented with 20% glycerol–0.4 M KCl and gently shaken for 30 min at 4°C. Nuclear protein extracts were obtained by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was stored at −80°C. Protein content was assayed using the Bio-Rad protein reagent. All cell fractionation steps were carried out at 4°C.

EMSA.

The sequences 5′TGCTAGGGGGATTTTCCCTCTCTCTGT3′, corresponding to the consensus NF-κB binding site (nucleotides −978 to −952) of the murine NOS-2 promoter (8, 51, 52), and 5′CGAACGTGACCTTTGTCCTCCCCTTTTGCTCGATC3′, corresponding to the PPARα binding site of the promoter of acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) oxidase (11), were used. Oligonucleotides were annealed with their complementary sequence by incubation for 5 min at 85°C in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–50 mM NaCl–10 mM MgCl2–1 mM DTT. Aliquots of 50 ng of these annealed oligonucleotides were end labeled with Klenow enzyme fragment in the presence of 50 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP and the other unlabeled deoxynucleoside triphosphates in a final volume of 50 μl. A total of 5 × 104 dpm of the DNA probe was used for each binding assay of nuclear extracts as follows. Three micrograms of nuclear protein was incubated for 15 min at 4°C with the DNA and 2 μg of poly(dI-dC)–5% glycerol–1 mM EDTA–100 mM KCl–5 mM MgCl2–1 mM DTT–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8) in a final volume of 20 μl. The DNA-protein complexes were separated on native 6% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5% Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (9). Supershift assays were carried out after incubation of the nuclear extracts with 2 μg of Ab (anti-p50, anti-c-Rel, anti-p65, and anti-PPARα) for 1 h at 4°C, followed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (not shown).

Transfection of RAW 264.7 cells and assay of CAT activity.

The cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 1.5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium without FCS (6-cm-diameter dishes). Cells were transfected for 6 h by lipofection with DOTAP as instructed by the supplier (Boehringer Mannheim). After transfection, the cells were maintained for 24 h prior to stimulation in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FCS. Equal amounts of DNA were used in the transfection experiments, and CAT activity was determined after 18 h of treatment of the cells with the indicated stimuli following a previous protocol based on thin-layer chromatography separation of the acetylated chloramphenicol (9). The amount of acetylated substrate was quantified in a Fuji BAS1000 radioactivity detection system.

Characterization of gene expression by Northern blotting.

Total RNA (2 × 106 to 4 × 106 cells) was extracted by the guanidinium thiocyanate method (2, 9, 24, 48). After electrophoresis in a 0.9% agarose gel containing 2% formaldehyde, the RNA was transferred to a Nytran membrane (NY 13-N; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany), and the levels of NOS-2, COX-2, IκBα, and IκBβ mRNAs were determined using an EcoRI-HindII fragment from the NOS-2 cDNA, or the cDNA of the other genes (48), labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using a Rediprime labeling kit (Amersham). The membranes were exposed to X-ray films (Hyperfilm; Amersham), and the intensity of the bands was measured by laser densitometry (Molecular Dynamics). The lane charge was normalized by hybridization with an 18S rRNA probe.

Determination of NO synthesis.

NO was measured as the accumulation of nitrite and nitrate in the incubation medium. Nitrate was reduced to nitrite with nitrate reductase and determined spectrophotometrically with Griess reagent (9).

Characterization of proteins by Western blotting.

Cytosolic protein extracts were size separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% gels. The gels were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore) and incubated with several anti-NOS-2, anti-IκBα, anti-IκBβ, anti-p85α (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase subunit), and anti-IKK2 Abs (Santa Cruz). In experiments using anti-phospho-(Ser32) IκBα Ab, the blot incubation solution contained GST-IκBα(1-317) (50 ng/ml) treated previously with alkaline phosphatase-agarose (47). The blots were submitted to sequential reprobing with Abs after treatment with 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 2% SDS in Tris-buffered saline and were heated at 60°C for 30 min. The blots were revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence as instructed by the manufacturer (Amersham).

Confocal microscopy.

RAW cells were grown on coverslips and incubated for 45 min with the indicated stimuli. After the disks were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, the cells were fixed with methanol at −20°C for 2 min, blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin for 30 min at room temperature, and incubated for 30 min with 1:100 anti-IκBα or anti-IκBβ Ab. After three washes with ice-cold PBS, the cells were revealed using a secondary Ab (1:300) against rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig) conjugated with Cy3 (Amersham). The cells were visualized using an MRC-1024 confocal microscope (Bio-Rad), and fluorescence was measured and electronically evaluated. Laser Sharp software (Bio-Rad) was used to determine the relative intensity of the fluorescence per pixel and the percentage of cytosolic and nuclear localization.

Measurement of IKK2 activity.

Cells (107) were homogenized in buffer A and centrifuged for 10 min in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant (1 ml) was precleared, and IKK2 was immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of anti-IKK2 Ab (10, 29). After extensive washing of the immunoprecipitate with buffer A, the pellet was resuspended in kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 0.1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin [2 μg/ml], leupeptin [10 μg/ml], TLCK [2 μg/ml], 5 mM NaF, 1 mM NaVO4, 10 mM Na2MoO4, 10 nM okadaic acid). Kinase activity was assayed in 100 μl of buffer A containing 100 ng of immunoprecipitate, 50 μM [γ-32P]ATP (0.5 μCi), and as substrate 100 ng of GST-IκBα(1-317) or GST-IκBα(1-54) and the corresponding Ala32/36-mutated protein. Aliquots of the reaction mixture were stopped at various times in 1 ml of ice-cold buffer A supplemented with 5 mM EDTA. The same protocol was used when the activity of IKK2 was followed by Western blotting using anti-phospho-(Ser32)IκBα Ab, except for the use of 1 mM MgATP instead of [γ-32P]ATP. GST-IκBα was purified by glutathione-agarose chromatography and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% gel). The linearity of the kinase reaction was confirmed over a period of 30 min.

Data analysis.

The number of experiments analyzed is indicated in the corresponding figure legend. Statistical differences (P < 0.05) between mean values (presented with standard errors of the means [SEM]) were determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Student's t test. In experiments using X-ray films (Hyperfilm), different exposure times were used to ensure that bands were not saturated.

RESULTS

15dPGJ2 inhibits the activation of NF-κB.

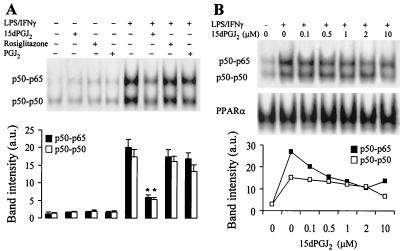

Incubation of cultured RAW 264.7 cells with 2 μM 15dPGJ2 inhibited significantly (79% after densitometry of the p50-p65 band) the activation of NF-κB elicited after LPS/IFN-γ challenge, as measured by EMSA (Fig. 1A). However, PGJ2 (2 μM) and rosiglitazone (10 μM) failed to exert a significant inhibition. A dose-dependent effect of 15dPGJ2 on NF-κB activity in LPS/IFNγ-stimulated cells is shown in Fig. 1B. The half-maximal inhibition was obtained at ca. 0.5 μM, as judged from the intensity of the p50-p65 band as assessed by supershift assays (not shown). The binding of nuclear proteins to the PPARα response element of the acyl-CoA oxidase promoter (11) was used as an internal control to ensure that 15dPGJ2 did not influence the extraction of nuclear proteins and as a control of lane charge.

FIG. 1.

NF-κB binding is inhibited in activated RAW 264.7 cells treated with 15dPGJ2. (A) Macrophages were incubated for 1 h with different combinations of 15dPGJ2 (2 μM), PGJ2 (2 μM), rosiglitazone (10 μM), LPS (500 ng/ml), and IFN-γ (10 U/ml). After homogenization of the cells, nuclear extracts were prepared and the binding of nuclear proteins to the distal κB motif of the NOS-2 promoter was determined by EMSA. Supershift assays with Abs against proteins of the c-Rel family (not shown) identified p50-p50 and p50-p65 as the complexes present in the lower and upper bands, respectively. (B) Dose-dependent effect of 15dPGJ2 on NF-κB activity. The binding of nuclear proteins to the PPARα R response element of the acyl-CoA oxidase promoter was used as control of extraction of nuclear proteins and lane load. The intensity of the bands was determined, and the corresponding values are expressed as mean ± SEM of three experiments (A). ∗, P < 0.005 with respect to the LPS/IFN-γ condition. a.u., arbitrary units.

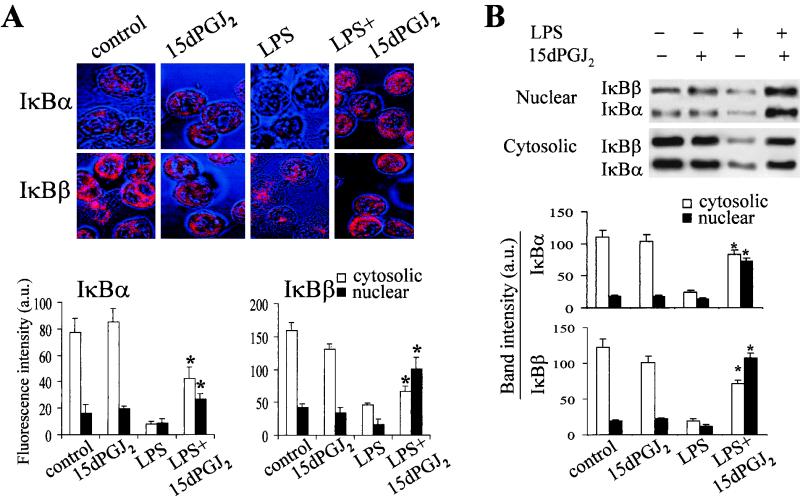

To evaluate whether 15dPGJ2 could influence the turnover and subcellular distribution of IκB proteins, and therefore NF-κB activation, the amounts of IκBα and IκBβ were determined in the cytosol and nucleus by confocal microscopy and by immunoblot analysis. As Fig. 2A shows, 15dPGJ2 did not modify significantly the levels and subcellular distribution of either IκBα or IκBβ; however, the marked decrease of IκB proteins elicited by LPS was notably impaired in the presence of 15dPGJ2. Moreover, an important nuclear accumulation of IκBβ (7-fold greater than in the LPS condition) and, to a lesser extent, of IκBα (3.1-fold greater than in the LPS condition) was observed in cells treated with LPS and 15dPGJ2. These results were confirmed when the amounts of IκBα and IκBβ were determined by Western blotting using nuclear and cytosolic extracts prepared from these cells (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Subcellular distribution of IκBα and IκBβ in cells treated with 15dPGJ2. Macrophages were incubated for 45 min with LPS (500 ng/ml) and 15dPGJ2 (1 μM). After the cells were fixed, IκB proteins were detected with specific Abs and revealed using Cy3-labeled anti-rabbit Ig. (A) The intensity of the fluorescence in the cytosolic and nuclear compartments was digitalized and quantified (n = 14 to 21 cells per condition). (B) The corresponding amount of IκBα and IκBβ present in cytosolic and nuclear extracts was determined also by Western blotting. Results show the mean ± SEM of three experiments. ∗, P < 0.05 with respect to the corresponding LPS condition.

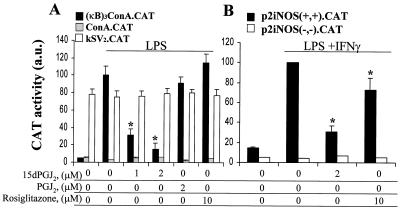

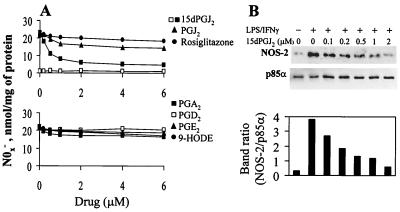

The inhibitory effect of 15dPGJ2 on NF-κB activity was further analyzed in cells transfected with the (κB)3ConA.CAT vector, by monitoring the reporter activity in response to LPS challenge. Incubation with 1 and 2 μM 15dPGJ2 decreased the LPS-dependent activation of the reporter by 69 and 85%, respectively. Treatment of cells with PGJ2, and rosiglitazone did not affect significantly the reporter activity (Fig. 3A). Transfection with ConA.CAT and kSV2.CAT vectors was used to ensure that the stimuli used did not influence transcription of the reporter gene. In addition to the κB-responsive vector, cells were transfected with the p2iNOS(+,+).CAT vector, a construct strictly dependent on NF-κB activation. As Fig. 3B shows, 15dPGJ2 decreased (75%) the CAT activity induced by LPS/IFN-γ, whereas 10 μM rosiglitazone inhibited only 27% of the expression of the reporter gene under identical experimental conditions. Interestingly, the use of a fragment of the NOS-2 promoter deleted in the κB sites [p2iNOS(−,−).CAT] completely abolished the activity of the promoter, reflecting the necessity of this motif for expression of the reporter gene in response to LPS/IFN-γ stimulation. To better assess the relevance of the changes of NF-κB activity on the expression of genes regulated by this transcription factor, we stimulated cells with different PGs and measured the activity and expression of NOS-2. As Fig. 4A shows, the synthesis of nitrite plus nitrate in LPS/IFN-γ-activated macrophages was inhibited (73%) in cells incubated with 2 μM 15dPGJ2, whereas PGJ2 exerted a moderate inhibition (27%) and rosiglitazone and other bioactive PGs had no significant effect. The dose-dependent effect of 15dPGJ2 on NOS-2 protein levels showed a half-maximal inhibition at ca. 0.2 to 0.5 μM PG (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 3.

15dPGJ2 inhibits CAT expression in cells transfected with (κB)3ConA.CAT and p2iNOS.CAT vectors. Macrophages were transfected with DOTAP, and cells were incubated with the indicated stimuli followed by activation with LPS (500 ng/ml) (A) or LPS (500 ng/ml) plus IFN-γ (10 U/ml) (B). After 14 h of incubation with the indicated stimuli, CAT activity was determined. Transfection with ConA.CAT and kSV2.CAT was used to ensure that the ligands did not affect the basal activity of the promoters and the efficiency of the transfection. Results show the mean ± SEM of three experiments. ∗, P < 0.01 with respect to the LPS or LPS/IFN-γ condition.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of NOS-2 expression by 15dPGJ2 in RAW 264.7 cells activated with LPS/IFN-γ. Cells were treated for 5 min with the indicated concentrations of PGs, rosiglitazone and hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (9-HODE), followed by activation with LPS (200 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (10 U/ml). (A) After 18 h of incubation,the amount of nitrite and nitrate in the culture medium was measured. (B) The dose-dependent effect of 15dPGJ2 on NOS-2 levels was determined by Western blotting, using the levels of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase subunit p85α as a control of lane charge. Results show the mean of three experiments (A) and a representative blot out of two (B).

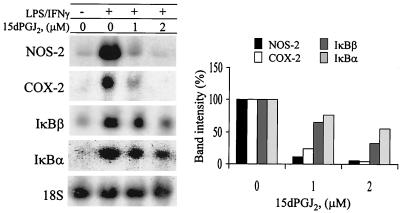

To better evaluate the biological effects of 15dPGJ2 on the transcription of genes that require NF-κB activation, the RNA levels of NOS-2 and COX-2 (both dependent on NF-κB activity in response to LPS/IFNγ challenge [24, 48]) and those of IκBα and IκBβ (involved in the resynthesis of these inhibitory proteins) were determined after 4 h of stimulation. Incubation with 1 μM 15dPGJ2 decreased by more than 90% the levels of NOS-2 and COX-2 mRNAs in activated macrophages. However, the effects were less remarkable for IκBα and IκBβ, due probably to the different kinetics of the steady-state levels of these RNAs (Fig. 5). Indeed, the levels of IκB mRNA measured in these cells may account for the accumulation of IκB observed at 2 to 3 h in LPS-activated cells treated with 15dPGJ2 (not shown).

FIG. 5.

15dPGJ2 decreases the mRNA levels of COX-2 and NOS-2. Cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of PG and activated with LPS (200 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (10 U/ml). After 4 h of treatment, the cells were homogenized and the RNA was extracted and analyzed by Northern blotting using probes specific for the indicated genes. Results show the mean band intensity expressed as a percentage of that in the absence of PG and after normalization for the content of 18S rRNA (n = 3).

Inhibition of IKK activity by 15dPGJ2.

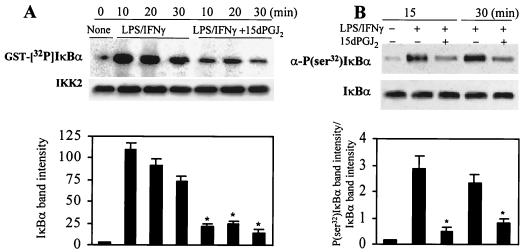

The preceding results show an inhibition of NF-κB activity, likely due to an impaired IκB targeting in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells treated with 15dPGJ2. To investigate the possibility of a reduced phosphorylation of IκB under these conditions, cells were incubated with 15dPGJ2 and stimulated with LPS/IFN-γ. The IKK complex was immunoprecipitated at various times using an anti-IKK2 Ab, and its kinase activity was evaluated with GST-IκBα as the substrate. As Fig. 6A shows, phosphorylation of GST-IκBα by IKK following the incorporation of [32P]phosphate at 20 and 30 min of reaction decreased by 70 and 75% with respect to the corresponding LPS/IFN-γ controls when cells were treated with 2 μM 15dPGJ2. Moreover, in a parallel experiment using cells incubated with 10 μM MG132 (Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-CHO) to inhibit IκB degradation, the specific phosphorylation in vivo of IκBα in Ser32 was inhibited in response to 15dPGJ2 (Fig. 6B). These results support the occurrence of a reduced activity of IKK2 in cells treated with 15dPGJ2.

FIG. 6.

Inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation in activated RAW 264.7 cells treated with 15dPGJ2. Macrophages were incubated with 2 μM 15dPGJ2 5 min prior to stimulation with LPS (200 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (10 U/ml). At the indicated times, cell extracts were prepared, IKK was immunoprecipitated, and the in vitro kinase activity of 100 ng of IP protein was assayed using GST-IκBα(1-317) and [γ-32P]ATP as substrates. (A) After 10 min of incubation, GST-IκBα was purified with glutathione-agarose and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% gel). Aliquots (5 μl) of the kinase reaction mixture were analyzed by Western blotting to determine the amount of IKK2 present in each assay. (B) Cells treated with 10 μM MG132 were stimulated as described previously; at the indicated times, cytosolic extracts were prepared and the amount of endogenous P(Ser32)IκBα was determined using a specific Ab. The blot was reprobed with anti-IκBα Ab. The intensity of the bands of phosphorylated IκBα (A) and the ratio between the band intensities of P(Ser32)IκBα and IκBα (B) are given. Results show the mean ± SEM of three experiments. ∗, P < 0.005 with respect to the corresponding LPS/IFN-γ condition.

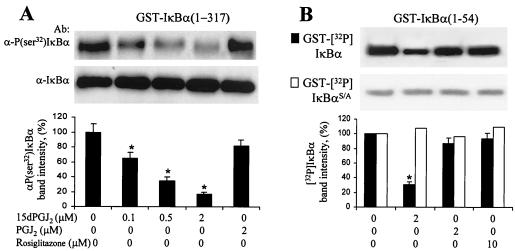

The mechanism by which 15dPGJ2 affects IKK activity appears to include a direct effect of this PG on the kinase activity of the complex. When IKK was immunoprecipitated from LPS/IFN-γ-treated cells and activity was assayed by monitoring GST-(Ser32)IκBα phosphorylation by Western blotting, a dose-dependent inhibition by 15dPGJ2 was observed; however, PGJ2 assayed at 2 μM failed to inhibit significantly the activity, suggesting a specific effect of 15dPGJ2 on the complex (Fig. 7A). Moreover, when kinase activity was assayed following the incorporation of [32P]phosphate into GST-IκBα or GST-IκBαS/A, the inhibitory effect of 15dPGJ2 was abolished after removal of the Ser32 and Ser36 phosphorylation sites. These results suggest that the direct effects of 15dPGJ2 on IKK activity are preferentially due to the inhibition of the phosphorylation of these residues (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Inhibition of IKK activity by 15dPGJ2. Macrophages were incubated for 20 min with LPS (200 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (10 U/ml); after homogenization, the IKK complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-IKK2 Ab. Kinase activity was monitored in vitro for 10 min, using GST-IκBα(1-317) as the substrate and in the presence of the indicated concentrations of PGs and rosiglitazone. P(Ser32)IκBα was detected using a specific anti-P(Ser32)IκBα Ab. The membrane was reprobed with anti-IκBα Ab (A). The incorporation of [32P]phosphate into GST-IκBα(1-54) or IκBαS/A was determined as previously described (B). Results show the mean ± SEM of the band intensities, expressed with respect to the condition in the absence of PG and rosiglitazone. ∗, P < 0.01 with respect to the condition in the absence of addition.

DISCUSSION

The biological effects of cyclopentenone PGs have been the subject of intense research in recent years, and multiple targets mediating their actions have been proposed, ranging from specific interactions with PPARγ, in which case they act as transcriptional regulators (14, 18, 36, 41), to effects on early signaling in response to a wide range of extracellular stimuli (5, 14, 38). In monocytes/macrophages, 15dPGJ2 exerts an anti-inflammatory action due to the attenuation of the expression of genes recognized classically as activators and mediators of different steps of the host defense response: first, it inhibits the synthesis and release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α that amplify the activation process (14); second, this PG inhibits the expression of effector proteins such as COX-2, NOS-2 (end products of which exert cytotoxic effects), and matrix metalloproteinases (4, 25, 36); third, it contributes to the resolution of the inflammatory process by promoting apoptosis of activated macrophages (1). This variety of effects produced by 15dPGJ2 and related cyclopentenone PGs is compatible with the existence of multiple sites of actions for these molecules (28, 33).

The anti-inflammatory actions of 15dPGJ2 have been considered to be mediated through the interaction with PPARγ. Ricote et al. (36) reported the absence in RAW 264.7 cells of such a transcription factor, and most of the effects observed in these cells were obtained after transient expression of PPARγ. However, PPARγ was present in elicited peritoneal macrophages, and exogenous expression of this factor was not required to observe 15dPGJ2-dependent actions. In agreement with previous results, specific PPARγ ligands, such as rosiglitazone assayed up to 10 μM (apparent dissociation constant [Kd], <100 nM), had no effect on NO synthesis or NF-κB inhibition in RAW cells (18, 36). The Kd of 15dPGJ2 for murine PPARγ was estimated to be between 1 and 10 μM. Moreover, portions of the experiments from this work were repeated using primary cultures of peritoneal macrophages, and the effects of 15dPGJ2 were very similar to those observed in RAW cells at short periods of times (up to 4 h). However, the effects were more pronounced when some parameters (for example, the synthesis of NO and the levels of NOS-2 protein) were measured at longer periods of times (18 to 24 h). These observations suggest the concurrence of other mechanisms, mediated possibly via PPARγ, that are also triggered by 15dPGJ2.

In this work, our attention was focused on the effects of 15dPGJ2 on the initial steps of macrophage activation after challenge with low doses of LPS and IFN-γ acting in a synergistic way (22, 32, 52). The observation of a decreased LPS/IFN-γ-dependent NF-κB activation by this PG precludes the expression of a large number of genes that require the engagement of this transcription factor (13, 23). 15dPGJ2 not only inhibited significantly the degradation of IκBα and IκBβ in these cells but also exerted marked effects on the nuclear distribution of these proteins. Moreover, the presence of IκB in the nucleus contributes to the inhibition of the binding of the active NF-κB complexes to the κB sites located in regulatory sequences of various genes (3, 46, 48). Indeed, the studies of the traffic of IκBα through the nuclear membrane suggest a physiological inhibitory role for the IκB proteins that are retained in the nucleus (37, 38). These data are in agreement with the observation of an important decrease in the binding of nuclear proteins to the κB sequences as determined by EMSA, as well as a very efficient repression of the transcription of genes requiring NF-κB activity, such as NOS-2 and COX-2 (mRNA levels were determined at 4 h), or in cells transfected with a κB reporter gene. However, when synthesis of nitrites was measured after 18 to 24 h of culture, the inhibitory action of 1 μM 15dPGJ2 was not as effective as that reflected by the action on mRNA levels (4 h). This might be due to the degradation of 15dPGJ2 in the cell, a process for which, to our knowledge, no kinetic control has been established. In contrast to this high efficiency in the repression of NOS-2 and COX-2 at 4 h, in experiments monitoring the mRNA levels of IκBα and IκBβ we observed the prevalence of an important upregulation of both RNAs, probably because of a higher sensitivity of these genes to NF-κB activation. Indeed, this particular regulation of IκB proteins might help to turn off NF-κB activity, precluding a persistent activation of this transcription factor (13, 46, 48).

In view of the rapid effects of 15dPGJ2 inhibiting IκB degradation, we investigated the action of this PG upstream of this step. In human monocytes, triggering with LPS activates IKK2, and this kinase is responsible for the specific phosphorylation of IκBs that targets these proteins for ubiquitination and degradation (27, 34, 43). In RAW 264.7 cells, we observed that 15dPGJ2 inhibits in vivo the specific phosphorylation of IκBα at Ser32. Moreover, when IKK activity was immunoprecipitated from activated cells, those treated with 15dPGJ2 showed a lower kinase activity with GST-IκBα as substrate, assayed by either monitoring [32P]phosphate incorporation or detecting phosphorylation of Ser32. The effect of 15dPGJ2 on other kinases was assayed; it failed to inhibit the activity of protein kinase A and the classic and new isotypes of protein kinase C assayed as Ca2+ and diacylglycerol-dependent activities, as well as the Jak activity associated with the IFN-γ receptor and followed by the specific phosphorylation of Stat1α in these cells (not shown). Moreover, the inhibition of IKK activity observed in cells treated with 15dPGJ2 can be explained through a direct and specific effect mediated by this PG, as confirmed by in vitro experiments. However, because the loss of activity persisted even when the IKK complex was immunoprecipitated and assayed in vitro, it is possible that 15dPGJ2 alters the structure of the IKK complex or favors an accelerated hyperphosphorylation state of IKK2 that has been described as impairing the kinase activity (6). In this regard, a positive and negative regulation of IKK through the phosphorylation of IKK2 has been described (6). In HeLa cells stimulated with TNF-α, IKK activity decreased faster than its phosphorylation. This is because phosphorylation of two loops of IKK is essential for the activation in response to proinflammatory stimuli, whereas autophosphorylation at the carboxyl terminus of a serine cluster contributes to the reduction of the activity. Preliminary experiments performed in cells labeled with [33P]phosphate showed an impairment in the phosphorylation state of IKK2 analyzed over a 30-min period, suggesting that 15dPGJ2 inhibits the activation of IKK2 rather than enhances its time-dependent phosphorylation (unpublished data). Taken together, the effects of 15dPGJ2 on the inhibition of IKK activity are reminiscent of those observed for other anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin and salicylate (53), suggesting an important role for IKK as a physiological and pharmacological target to mediate anti-inflammatory actions.

In conclusion, our data show a specific action of 15dPGJ2 on the activity of the IKK complex, an inhibitory effect that can be observed directly when the kinase is assayed in vitro. In addition, 15dPGJ2 redistributes IκBα and in particular IκBβ in the nuclei of activated macrophages, a process that may contribute to the impairment of NF-κB activation. Unraveling the presumably sequential targets for 15dPGJ2 and related PGs might contribute to a better understanding of the mechanism of action of physiologically occurring anti-inflammatory PGs as well as those pertaining to the process of resolution of inflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Q.-W. Xie and C. Nathan for the generous gift of the NOS-2 promoter, T. J. Evans for the gift of the mutated κB sequences of the NOS-2 promoter, J. Moscat for the mutated GST-IκBα constructs, and A. Alvarez from the Centro de Citometría de Flujo and Microspopía Confocal for the immunofluorescence analysis. The technical support of O. G. Bodelón and the help of E. Lundin in preparing the manuscript are acknowledged.

This work was supported by DGESIC (PM98-0120) and Comunidad de Madrid (08.3/004/97).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chinetti G, Griglio S, Antonucci M, Torra I P, Delerive P, Majd Z, Fruchart J C, Chapman J, Najib J, Staels B. Activation of proliferator-activated receptors α and γ induces apoptosis of human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25573–25580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu Z L, McKinsey T A, Liu L, Qi X, Ballard D W. Basal phosphorylation of the PEST domain in the IκBβ regulates its functional interaction with the c-rel proto-oncogene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5974–5984. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colville-Nash P R, Qureshi S S, Willis D, Willoughby D A. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists: correlation with induction of heme oxygenase 1. J Immunol. 1998;161:978–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Acquisto F, Sautebin L, Iuvone T, Di Rosa M, Carnuccio R. Prostaglandins prevent inducible nitric oxide synthase protein expression by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB activation in J774 macrophages. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, Karin M. Positive and negative regulation of IκB kinase activity through IKKβ subunit phosphorylation. Science. 1999;284:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeWitt D L. Prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase: regulation of enzyme expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1083:121–134. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(91)90032-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz-Guerra M J M, Castrillo A, Martin-Sanz P, Bosca L. Negative regulation by protein tyrosine phosphatase of IFN-γ-dependent expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Immunol. 1999;162:6776–6783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz-Guerra M J M, Velasco M, Martin-Sanz P, Bosca L. Evidence for common mechanisms in the transcriptional control of type II nitric oxide synthase in isolated hepatocytes. Requirement of NF-κB activation after stimulation with bacterial cell wall products and phorbol esters. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30114–30120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiDonato J A, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf D M, Zandi E, Karin M. A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowell P, Peterson V J, Zabriskie T M, Leid M. Ligand-induced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α conformational change. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2013–2020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forman B M, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun R P, Spiegelman B M, Evans R M. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPARγ. Cell. 1995;83:803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh S, May M J, Kopp E B. NF-κB and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang C, Ting A T, Seed B. PPAR-γ agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391:82–86. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karin M. The beginning of the end: IκB kinase (IKK) and NF-κB activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27339–27342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitamura Y, Kakimura J, Matsuoka Y, Nomura Y, Gebicke-Haerter P J, Taniguchi T. Activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR γ) inhibit inducible nitric oxide synthase expression but increase heme oxygenase-1 expression in rat glial cells. Neurosci Lett. 1999;262:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kliewer S A, Lenhard J M, Willson T M, Patel I, Morris D C, Lehmann J M. A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1995;83:813–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krey G, Braissant O, L'Horset F, Kalkhoven E, Perroud M, Parker M G, Wahli W. Fatty acids, eicosanoids, and hypolipidemic agents identified as ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors by coactivator-dependent receptor ligand assay. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:779–791. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lallena M J, Diaz-Meco M T, Bren G, Paya C V, Moscat J. Activation of IκB kinase β by protein kinase C isoforms. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2180–2188. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Van Antwerp D, Mercurio F, Lee K F, Verma I M. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IκB kinase 2 gene. Science. 1999;284:321–325. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez-Collazo E, Hortelano S, Rojas A, Bosca L. Triggering of peritoneal macrophages with IFN-α/β attenuates the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase through a decrease in NF-κB activation. J Immunol. 1998;160:2889–2895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowenstein C J, Alley E W, Raval P, Snowman A M, Snyder S H, Russell S W, Murphy W J. Macrophage nitric oxide synthase gene: two upstream regions mediate induction by interferon γ and lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9730–9734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacMicking J, Xie Q W, Nathan C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin-Sanz P, Callejas N A, Casado M, Diaz-Guerra M J, Bosca L. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in foetal rat hepatocytes stimulated with lipopolysaccharide and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:1313–1319. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marx N, Sukhova G, Murphy C, Libby P, Plutzky J. Macrophages in human atheroma contain PPARγ: differentiation-dependent peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptorγ (PPARγ) expression and reduction of MMP-9 activity through PPARγ activation in mononuclear phagocytes in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65540-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May M J, Ghosh S. Signal transduction through NF-κB. Immunol Today. 1998;19:80–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.May M J, Ghosh S. IκB kinases: kinsmen with different crafts. Science. 1999;284:271–273. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGeer P L, Schulzer M, McGeer E G. Arthritis and anti-inflammatory agents as possible protective factors for Alzheimer's disease: a review of 17 epidemiologic studies. Neurology. 1996;47:425–432. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray B W, Shevchenko A, Bennett B L, Li J, Young D B, Barbosa M, Mann M, Manning A, Rao A. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakano H, Shindo M, Sakon S, Nishinaka S, Mihara M, Yagita H, Okumura K. Differential regulation of IκB kinase α and β by two upstream kinases, NF-κB-inducing kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase kinase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;5:3537–3542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nathan C. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: what difference does it make? J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2417–2423. doi: 10.1172/JCI119782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nathan C, Xie Q W. Nitric oxide synthases: roles, tolls, and controls. Cell. 1994;78:915–918. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Negishi M, Koizumi T, Ichikawa A. Biological actions of delta 12-prostaglandin J2. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal. 1995;12:443–448. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(95)00029-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Connell M A, Bennett B L, Mercurio F, Manning A M, Mackman N. Role of IKK1 and IKK2 in lipopolysaccharide signaling in human monocytic cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30410–30414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrova T V, Akama K T, Van Eldik L J. Cyclopentenone prostaglandins suppress activation of microglia: down-regulation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase by 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4668–4673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricote M, Li A C, Willson T M, Kelly C J, Glass C K. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez M S, Thompson J, Hay R T, Dargemont C. Nuclear retention of IκBα protects it from signal-induced degradation and inhibits nuclear factor κB transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9108–9115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.9108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossi A, Elia G, Santoro M G. Inhibition of nuclear factor κB by prostaglandin A1: an effect associated with heat shock transcription factor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:746–750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rozera C, Carattoli A, De Marco A, Amici C, Giorgi C, Santoro M G. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by cyclopentenone prostaglandins in acutely infected human cells. Evidence for a transcriptional block. J Clin Investig. 1996;97:1795–1803. doi: 10.1172/JCI118609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller M M, Schaffner W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spiegelman B M. PPAR-γ: adipogenic regulator and thiazolidinedione receptor. Diabetes. 1998;47:507–514. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spink J, Cohen J, Evans T J. The cytokine responsive vascular smooth muscle cell enhancer of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Activation by nuclear factor-κB. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29541–29547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stancovski I, Baltimore D. NF-κB activation: the IκB kinase revealed? Cell. 1997;91:299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor J A, Bren G D, Pennington K N, Trushin S A, Asin S, Paya C V. Serine 32 and serine 36 of IκBα are directly phosphorylated by protein kinase CKII in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:839–850. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thanos D, Maniatis T. NF-κB: a lesson in family values. Cell. 1995;80:529–532. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson J E, Phillips R J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. IκB-β regulates the persistent response in a biphasic activation of NF-κB. Cell. 1995;80:573–582. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai S H, Lin-Shiau S Y, Lin J K. Suppression of nitric oxide synthase and the down-regulation of the activation of NFκB in macrophages by resveratrol. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:673–680. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Velasco M, Diaz-Guerra M J, Martin-Sanz P, Alvarez A, Bosca L. Rapid up-regulation of IκBβ and abrogation of NF-κB activity in peritoneal macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23025–23030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright K, Ward S G, Kolios G, Westwick J. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by interleukin-13. An inhibitory signal for inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression in epithelial cell line HT-29. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12626–12633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie Q, Nathan C. The high-output nitric oxide pathway: role and regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:576–582. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.5.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie Q W, Kashiwabara Y, Nathan C. Role of transcription factor NF-κB/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4705–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie Q W, Whisnant R, Nathan C. Promoter of the mouse gene encoding calcium-independent nitric oxide synthase confers inducibility by interferon γ and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1779–1784. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yin M J, Yamamoto Y, Gaynor R B. The anti-inflammatory agents aspirin and salicylate inhibit the activity of IκB kinase-β. Nature. 1998;396:77–80. doi: 10.1038/23948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zandi E, Chen Y, Karin M. Direct phosphorylation of IκB by IKKα and IKKβ: discrimination between free and NF-κB-bound substrate. Science. 1998;281:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zandi E, Karin M. Bridging the gap: composition, regulation, and physiological function of the IκB kinase complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4547–4551. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zandi E, Rothwarf D M, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M. The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell. 1997;91:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]