Abstract

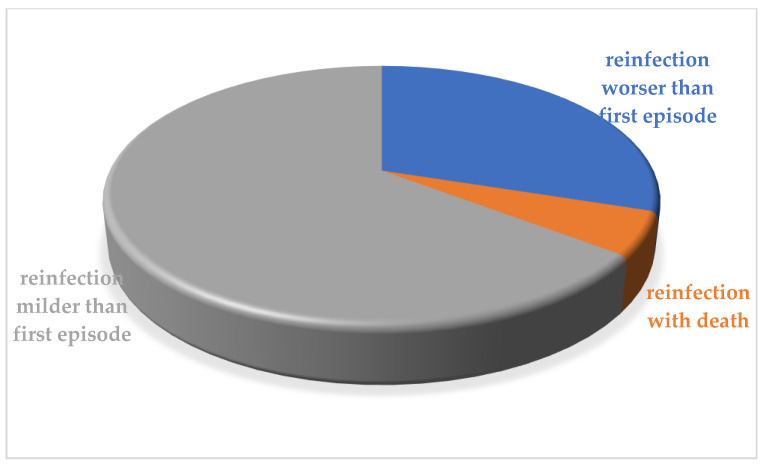

Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 seems to be a rare phenomenon. The objective of this study is to carry out a systematic search of literature on the SARS-CoV-2 reinfection in order to understand the success of the global vaccine campaigns. A systematic search was performed. Inclusion criteria included a positive RT-PCR test of more than 90 days after the initial test and the confirmed recovery or a positive RT-PCR test of more than 45 days after the initial test that is accompanied by compatible symptoms or epidemiological exposure, naturally after the confirmed recovery. Only 117 articles were included in the final review with 260 confirmed cases. The severity of the reinfection episode was more severe in 92/260 (35.3%) with death only in 14 cases. The observation that many reinfection cases were less severe than initial cases is interesting because it may suggest partial protection from disease. Another interesting line of data is the detection of different clades or lineages by genome sequencing between initial infection and reinfection in 52/260 cases (20%). The findings are useful and contribute towards the role of vaccination in response to the COVID-19 infections. Due to the reinfection cases with SARS-CoV-2, it is evident that the level of immunity is not 100% for all individuals. These data highlight how it is necessary to continue to observe all the prescriptions recently indicated in the literature in order to avoid new contagion for all people after healing from COVID-19 or becoming asymptomatic positive.

Keywords: coronavirus, reinfection, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, systematic review

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak since December 2019 has continued to exhibit devastating consequences, and was declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization in early 2020 [1,2,3]. To date, as of 17 October 2021, 240,421,359 infections have been confirmed, with 4,895,034 deaths [4]. In many countries, the vaccination campaign has started with the use of various vaccines recently put on the market and the total number of vaccine doses administered is 6,609,632,994. However, a new problem is emerging with regard to the evolution of the behavior of SARS-CoV-2: the possibility of reinfection of healed subjects after the first infection. On 25 August 2020, the first case of reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 was reported in international literature [5]. This event pointed out that infection by this virus does not uniformly confer protective immunity to all infected individuals [6]. Therefore, several critical questions are intriguing the researchers. Is SARS-CoV-2 reinfection a widespread phenomenon or is it limited to few subjects with immune deficits or specific comorbidities [6]? Can this phenomenon be due to a too weak, too short, or too narrow natural immune response to SARS-CoV-2, that is unable to protect from subsequent exposure [6]? What is the clinical behavior, in regard to the evolution of the reinfections? Can these reinfected patients transmit the viruses? This important problem needs to be addressed, because the possibility of reinfection could drastically reduce the effectiveness of the vaccination campaigns in progress. Protective, sustainable and long-lasting immunity following COVID-19 infection is uncertain, but it is essential for the efficacity of vaccine strategy.

For some viruses, the first infection can provide lifelong immunity, for seasonal coronaviruses protective immunity is short-lived [7]. Over the years, other viruses responsible for various infectious respiratory diseases have been able to present reinfection in the originally cured subjects, such as the coronavirus HCoV-NL63 (NL63) [8] and the human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) [9].

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses a challenge regarding the follow-up of recovered patients and the question of the reinfection risk. Several reports confirmed that most patients with SARS-CoV-2 produce antibodies against spike and N-proteins of the virus within 30 days after the infection [10,11]. In fact, an outbreak of the virus on a fishery vessel showed that fishers with prior neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were not reinfected [12]. The potential mechanisms that mediate immunity post-COVID-19 are not yet fully understood. COVID-19 typically follows a course similar to other respiratory viral illnesses, and it is self-limiting in more than 80% of cases [13]. An innate immune response involving T cells and B cells is activated, leading to the production of neutralizing antiviral antibodies [13]. The specific IgM antibody response starts to peak within the first 7 days [13]. Specific IgG and IgA antibodies develop a few days after IgM and are hypothesized to persist at low levels, conferring lifelong protective antibodies [14]. While this hypothesis may hold true for symptomatic patients, emerging data have revealed negative IgM and IgG during the early convalescent phase in asymptomatic patients [15] and 40% of asymptomatic patients became seronegative for IgG 8 weeks after discharging compared with 12.9% who were seronegative for the symptomatic group [15]. A seronegative status could leave open the possibility of reinfection. Immunosuppression and comorbid diseases can be other risk factors for a reinfection [16].

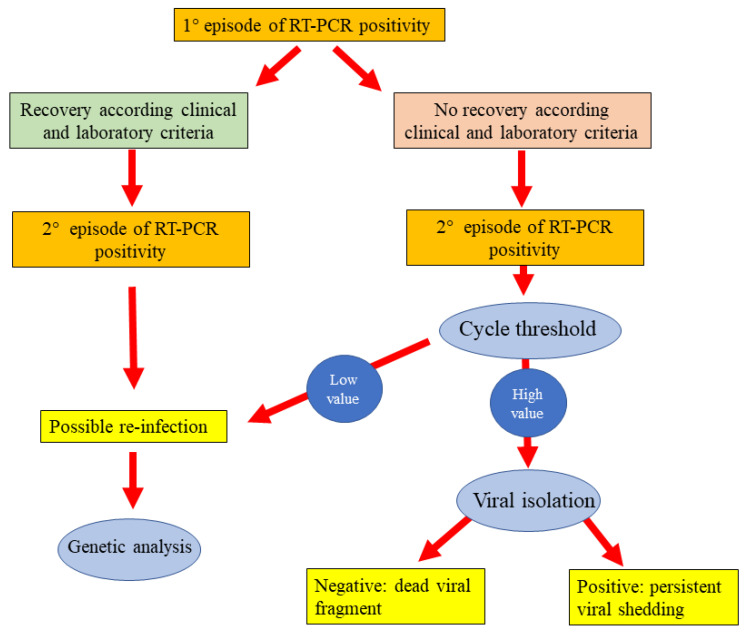

However, a distinction must be made between prolonged shedding/reactivation and true reinfection [17], in fact one of the features of SARS-CoV-2 infection is prolonged virus shedding. Several studies reported persistent or recurrent elimination of viral RNA in nasopharyngeal samples starting from first contact with a positive subject [18,19,20]. For this reason, recently the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a guidance protocol designed to identify cases of real SARS-CoV-2 reinfection [21]. This guidance defines some criteria about sequencing parameters, epidemiological data and laboratory diagnostic data (Table 1). Specifically, investigative criteria include a positive RT-PCR test more than 90 days after the initial test in healed patients or a positive RT-PCR test more than 45 days after the initial test that is accompanied by compatible symptoms or epidemiological exposure, after confirmed healing.

Table 1.

Protocol of Center for Disease Control and Prevention for investigating suspected SARS-CoV-2 reinfection.

| Investigative Criteria | Laboratory Evidence |

|---|---|

|

Best evidence Differing clades as defined in Nextstrain and GISAID of SARS-CoV-2 between the first and second infection, ideally coupled with other evidence of actual infection (e.g., high viral titers in each sample or positive for subgenomic mRNA, and culture) |

with a symptomatic second episode and no obvious alternate etiology for COVID-19-like symptoms or close contact with a person known to have laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 |

Moderate evidence >2 nucleotide differences per month * in consensus between sequences that meet quality metrics above, ideally coupled with other evidence of actual infection (e.g., high viral titers in each sample or positive for subgenomic mRNA, and culture) |

|

Poor evidence but possible ≤2 nucleotide differences per month * in consensus between sequences that meet quality metrics above or >2 nucleotide differences per month * in consensus between sequences that do not meet quality metrics above, ideally coupled with other evidence of actual infection (e.g., high viral titers in each sample or positive for subgenomic mRNA, and culture) |

* The mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 is estimated at 2 nucleotide differences per month, therefore if suspected reinfection occurs 90 days after initial infection, moderate evidence would require >6 nucleotide differences.

Another emerging problem that can influence the possibility of reinfection and the vaccination efficacity is the new variants of SARS-CoV-2, such us alpha, beta, gamma and delta. A recent study on 9119 patients with SAS-CoV-2 infection identified reinfection in 63 cases (0.7%, 95% confidence interval 0.5–0.9%) [22]. The mean period between two positive tests was 116 ± 21 days [22]. There were no significant differences based on age or sex, while nicotine dependence/tobacco use, asthma were higher in patients with reinfection [22]. There was a significantly lower rate of pneumonia, heart failure, and acute kidney injury during reinfection compared with primary infection [22]. There were two deaths (3.2%) associated with reinfection [22].

Another study conducted in Switzerland reported five cases of reinfection (1%) in 498 seropositive individuals followed for 35 weeks [23]. Breathnach et al. examined data of 10,727 patients with COVID-19 in the first wave and individuated eight reinfection cases (0.07%), all in female patients, and only one was admitted in hospital [24]. Bongiovanni et al. examined 677 subjects with at least a positive nasopharyngeal swab, 328 during the first wave and 349 during the second individuating 13 (1.9%) cases of reinfection [25]. Vitale et al. examined a cohort of 1579 patients and reported five reinfections (0.31%, 95% CI, 0.03–0.58%), of whom only one was hospitalized and the mean (SD) interval between primary infection and reinfection was longer than 230 (90) days [26].

The understanding of COVID-19 reinfection will be key in guiding government and public health policy decisions in the coming months.

A systematic review of literature was performed in order to individuate cases of reinfection for SARS-CoV-2. To date there are more than 300 reported cases of COVID-19 reinfection from different countries such as United States [27], Ecuador [28], Hong Kong [5], and Belgium [29]. It is necessary to understand if all these cases are really reinfection.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review of literature on reinfections of SARS-CoV-2 was conducted in August 2021. Our study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist to ensure the reliability and validity of this study and results.

2.1. Data Sources

By application of a systematic search and using the keywords in the online databases including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, EMBASE, and preprint servers (MedRxiv, BioRxiv, and SSRN) on 31 July 2021, we extracted all the papers published in English from December 2019 to July 2021. We included several combinations of keywords in the following orders to conduct the search strategy: (1) “CoVID-19” or “SARS-CoV-2” or “2019-nCoV” [all field]; (2) “Reinfection” or “Re-infection” [all field].

2.2. Study Selection

Three independent investigators retrieved the studies that were the most relevant by titles and abstracts (ELM, LLM, MA). Subsequently, the full text of the retrieved papers was reviewed, and the most relevant papers were chosen according to the eligibility criteria. Then, we extracted the relevant data and organized them in tables. The original papers that were peer-reviewed and published in English and fulfilled the eligibility criteria were included in the final report, together with two works not reviewed at the time of preparation of this report [30,31].

The following inclusion criteria was used: a positive RT-PCR test carried out more than 90 days after the initial test in healed patients or a positive RT-PCR test carried out more than 45 days after the initial test that is accompanied by compatible symptoms or epidemiological exposure, after confirmed healing. This criteria corresponds to the CDC protocol designed to identify cases of real SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (Table 1) [32].

We considered the exclusion criteria for this study as follows: (1) papers conveying non-human studies including in vitro observations or articles focusing on animal experiments; (2) papers in which their full text were out of access; (3) any suspicious and duplicated results in the databases.

2.3. Data Extraction

After summarizing, we transferred the information of the authors, type of article (e.g., case reports), publication date, country of origin, age, gender, and clinical symptoms to a data extraction sheet. Three independent investigators collected this information and subsequently organized them in the tables. Finally, to ensure no duplications or overlap existed in the content, all the selected articles were cross-checked by other authors.

2.4. Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

As aforementioned, we applied the PRISMA checklist to ensure the quality and reliability of selected articles. Two independent researchers evaluated the consistency and quality of the articles and the risk of bias. In either case of discrepancy in viewpoints, a third independent researcher resolved the issue. The full text of selected articles was read, and the key findings were extracted.

Included studies underwent quality check and risk of bias assessment. This qualitative analysis was performed according Murad’s quality checklist of case series and case report [33]. As reported, the scale consists of four parameters, to evaluate the (a) patient selection; (b) exposure ascertainment; (c) causality; (d) reporting. Each section contains one to four question to be addressed. As it is suggested we performed an overall judgement about methodological quality since questions 4, 5 and 6 are mostly relevant to cases of adverse drug events. Each requested field will be considered as adequate, inadequate or not evaluable. The table showing this tool for evaluating the methodological quality of case reports and case series, is reported in the original manuscript [33].

3. Results

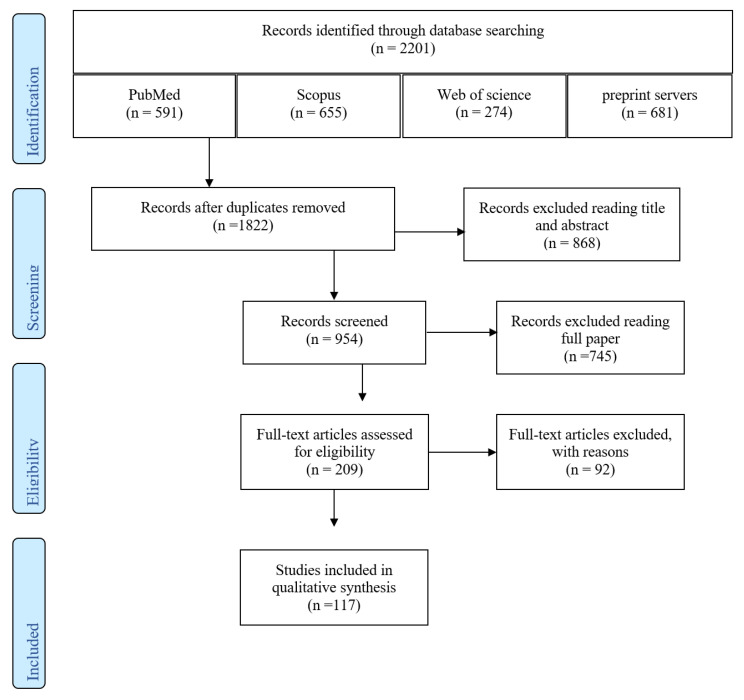

In this study, 117 documents were identified using the systematic search strategy. After a primary review of 2201 retrieved articles, 379 duplicates were removed, and the title and abstract of the remaining 1822 resources were reviewed. After applying the selection criteria, only 117 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review (Figure 1). Therefore, the cases confirmed according to these parameters were 260 (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the selection process of identified articles.

Table 2.

Cases of SARS-CoV2 reinfection in the international literature (all cases were again positive for SARS-CoV-2 after complete symptomatic recovery in addition to negative RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2, according to WHO recommendations [34]).

| Authors | Year | Patient Country | Patient | Interval Time between 1 Infection and Reinfection | Viral Genome Sequence | COVID-19 | Symptoms | Antibody after First Infection or Reinfection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2021 | Qatar | 25–29-year-old man | 46 | 9 SNVs compared to initial infection strain, including D614G | Mild | N/A | N/A |

| Mild | N/A | |||||||

|

2021 | Qatar | 40–44-year-old man | 71 | 11 SNVs compared to initial infection strain, including D614G | Mild | N/A | N/A |

| Mild | N/A | |||||||

|

2021 | Qatar | 45–49-year-old woman | 88 | 3 SNVs compared to initial infection strain, including D614G | Mild | N/A | ROCHE elecsys antiSARS-CoV-2 negative at time of reinfection |

| Mild | N/A | |||||||

|

2021 | Qatar | 25–29-year-old woman | 55 | 1 SNVs compared to initial infection strain, including D614G | Mild | N/A | N/A |

| Mild | N/A | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 44-year-old healthcare man with systemic arterial hypertension, obesity | 53 | 20A | Mild | Dry cough, dyspnea, dysgeusia, diarrhea, asthenia, sneezing/runny nose | N/A |

| Clade B.1.1.28 | Worse | Dry cough, dyspnea, fever, myalgia, asthenia, arthralgia, headache, nausea/vomiting, sneezing/runny nose, severe respiratory symptoms and was admitted to ICU, dying after 20 days of symptoms | ||||||

|

2021 | Spain | 39-year-old healthcare man | 290 | N/A | Mild | Sore throat, fever, general malaise, nasal congestion, tachycardia, chest pain, loss of smell and taste | Rapid antibody test: positive |

| 201/501Y.V1.Britain variant B.1.17 | Milder | Sore throat, slight general malaise, nasal congestion, tiredness | Rapid antibody test: positive | |||||

|

2021 | Iran | 36-year-old healthcare man | 60 | N/A | Mild | Lethargy, fatigue, shortness of breath, headache, fever, chills | N/A |

| Milder | Eye infection, fever, fatigue, shortness of breath, muscle pain | |||||||

|

2021 | Pakistan | Healthcare worker man | 118 | N/A | Mild | Arthralgia, weakness, anosmia, ageusia | N/A |

| Milder | Fever, sore throat, dry cough | |||||||

|

2021 | Pakistan | Healthcare worker man | 86 | N/A | Mild | Fever, sore throat | N/A |

| Milder | Sinusitis | |||||||

|

2021 | Pakistan | 40-year-old male | 94 | N/A | Mild | Fever | N/A |

| Worse | Sore throat, cough, diarrhea | |||||||

|

2021 | Bahrain | 47-year-old woman without comorbidities | 60 | N/A | Mild | Mild respiratory tract symptoms | N/A |

| Worse | Abdominal pain, fulminant hepatic failure > death | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 20s year age range, male | 89 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 6.7 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, myalgia, cough, loss of taste, loss of smell | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 30s year age range, female | 55 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 10.3 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 40s year age range, male | 55 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 15.5 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Mild | Fever, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 50s year age range, male | 46 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 10.3 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 50s year age range, female | 53 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, loss of taste and smell | 5.35 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Milder | Fever, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 40s year age range, male | 76 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 7.22 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 40s year age range, female | 45 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 11.2 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 40s year age range, male | 50 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia | 12.51 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Mild | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 40s year age range, male | 62 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, cough | 7.11 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 40s year age range, female | 49 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever | 8.37 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 40s year age range, male | 72 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever | 5.11 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 30s year age range, male | 59 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia | 6.3 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Mild | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 50s year age range, male | 53 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 9.3 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 20s year age range, male | 49 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 7.25 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 40s year age range, female | 52 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | 6.21 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Worse | Loss of taste and smell, myalgia | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 20s year age range, female | 54 ** | N/A | Mild | Fever | 11.9 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Mild | Fever, cough | |||||||

|

2020 | Iran | 30s year age range, male | 138 ** | N/A | Moderate | Fever, loss of taste and smell, myalgia, cough | 2.08 IgG (s/ca) after recovery |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |||||||

|

2020 | Qatar | 46-year-old woman with mild asthma | 80 | N/A | Mild | Sore throat | N/A |

| Moderate | Chest pain, fever, sore throat, body pain, cough, mild dyspnea | |||||||

|

2021 | Saudi Arabia | 51-year-old woman with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 160 | 19B | Mild | Fever, cough, malaise, and headache | Negative COVID-19 serology after 1st infection and reinfection |

| 20B | Mild | Fever and dyspnea | ||||||

|

2021 | Turkey | 34-year-old man with chronic glomerulonephritis | >150 | N/A | Mild | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Worse | Cough, fever, bilateral infiltrates at computed chest tomography | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 35-year-old healthcare worker woman | 55 | N/A | Mild | Fever, headache, chills, sneezing, coryza, myalgia | N/A |

| Mild | Headache, nasal congestion, odynophagia, ageusia, anosmia | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 61-year-old healthcare worker woman with chronic bronchitis | 170 | N/A | Mild | Headache, cough, myalgia, odynophagia, coryza, diarrhea, ageusia | N/A |

| Mild | Cough, myalgia, odynophagia, anosmia, diarrhea | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 40-year-old healthcare worker woman | 131 | N/A | Mild | Nasal congestion, coryza, cough, ageusia | N/A |

| Mild | Odynophagia, sneezing, coryza, diarrhea, ageusia, anosmia | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 40-year-old healthcare worker woman | 148 | N/A | Mild | Fever, headache, myalgia, coryza, dry cough, vomiting, malaise | N/A |

| Mild | Odynophagia, dry cough, myalgia, malaise, coryza, headache | |||||||

|

2021 | Peru | 42-year-old healthcare worker woman | 107 | N/A | Mild with home management | Odynophagia, headache, malaise, rhinorrhea, ageusia, anosmia, cough | IgM and IgG+ |

| Worse with home management | Chest pain, productive cough, anosmia, pneumonia | |||||||

|

2021 | Turkey | 46-year-old healthcare worker man | 114 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, sore throat, headache, cough, weakness, nausea and diarrhea, bilateral ground glass opacities and peribronchial thickening predominating on the right lung |

N/A |

| Mild | Sore throat, fever, headache, myalgia, weakness and nausea | |||||||

|

2021 | Turkey | 47-year-old healthcare worker woman | 128 | N/A | Mild | Myalgia, headache and abdominal pain started without fever and cough | N/A |

| Worse | Sore throat, headache and myalgia, fever, cough and mild respiratory symptoms, ground glass opacities and subpleural nodule on the left lung base consistent with COVID-19 on chest CT imagine | |||||||

|

2021 | Lebanon | 27-year-old man | 56 | N/A | Mild | Fever, chills, diffuse arthralgia, myalgia, headache, back pain | N/A |

| Milder | Fever, headache | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 73-year-old man with obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pancreatic insufficiency, type II diabetes mellitus | 60 | N/A | Mild | Shortness of breath | N/A |

| Worse | Dyspnea, fevers, confusion with worsening clinical situation and intubation | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 28-year-old male with diabetes mellitus type 1, hypertension, and end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis with multiple past admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis and uncontrolled hypertension | 122 | N/A | Mild | Nausea and vomiting | N/A |

| Worse | Headaches and altered mental status, left-hand weakness. The patient became unresponsive and was intubated for airway protection > cerebrovascular accident | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 76-year-old female with end-stage kidney disease related to lambda light chain multiple myeloma | 126 | N/A | Moderate | Hip pain, confusion, respiratory distress | N/A |

| Worse | Dyspnea, acute respiratory failure, hypoxemia > death | |||||||

|

2020 | Italy | 48-year-old nurse female | 90 | N/A | Mild | Dry cough, mild fever | LIASON ® SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG+ 30 Au/mL |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | IgG+ 102.9 Au/mL | ||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 24-year-old white female without comorbidities | 76 | N/A | Mild with complete resolution at home within 10 days | Headache, malaise, adynamia, feverish sensation, sore throat, nasal congestion | N/A |

| Worse with home resolution in 12 days, headache and hyposmia for 63 days | Malaise, myalgia, severe headache, fatigue, weakness, feverish sensation, sore throat, anosmia, dysgeusia, diarrhea, coughing | IgG/IgM– at NAAT+IgG/IgM+ 28 days after NAAT+ | ||||||

|

2021 | Italy | 52-year-old man with transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis | 110 | Clade 20B and Pangolin lineage B.1.1 | Mild | Cough, fever | |

| Clade 20A and Pangolin lineage B.1 | Milder | Fever | Very low levels of IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, positive IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 N protein | |||||

|

2021 | Germany | 27-year-old female nurse | 282 | HH-24.I (19A) |

Mild | Fever, chills, dyspnea | IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein: 40 AU/mL in July 2020, 15 AU/mL in September 2020 |

| HH-24.II (20EU1) with differences in 21 positions, including 2 typical variations in spike proteins A222V and D614G | Milder | Dry cough, mild rhinorrhea | IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein: 97 AU/mL on 29 December | |||||

|

2021 | The Netherlands | 16-year-old girl | 390 | Classic | Moderate | High fever, mild conjunctivitis, malaise, chest pain, coughing, abdominal pain and diarrhea. She was diagnosed with myocarditis, shock and had high inflammatory parameters. | IgG SARS-CoV-2 was negative (Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG; Abbott Laboratories) |

| B.1.1.7 variant (UK variant), | Mild | Mild respiratory symptoms | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 60 with diabetes | 72 | N/A | Mild | Acute renal failure | |

| Milder | Fatigue | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 27 with psoriatic arthritis | 79 | N/A | Mild | Fever, flu-like | IgG+ |

| Milder | Fatigue, loss taste | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 33 year-old woman with allergic rhinitis | 172 | N/A | Mild | Fever, cough, diarrhea | IgG+ |

| Milder | Fever headache | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 71 with renal/liver transplant HIV, diabetes | 93 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, pneumonia, respiratory insufficiency | |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 72 with pulmonary/cardiac sarcoidosis | 111 | N/A | Mild | Dyspnea, fatigue, headache | |

| Milder | Fatigue | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | M (80–89 years old) | 101 | N/A | Asymptomatic | asymptomatic | N/A |

| Mild | Lethargy, decreased appetite, dry cough for 14 days | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | F (80–89 years old) | 103 | N/A | Asymptomatic | asymptomatic | N/A |

| Worse | Congestion, respiratory failure and death | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | F (60–69 years old) | 109 | N/A | Mild | nausea | N/A |

| Mild | Cough, sore throat, loss of appetite, malaise, muscle aches for 17 days | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | F (70–79 years old) | 109 | N/A | Mild | Gastrointestinal symptoms for 17 days | N/A |

| Milder | Loss of appetite, malaise for 12 days | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | Female (90–99 years old) | 110 | N/A | Asymptomatic | asymptomatic | N/A |

| Mild | Cough, loss of appetite, malaise, muscle aches for 6 days | |||||||

|

2021 | France | 70-year-old man | 105 | Clade 20A | Moderate | Fever, cough | IgG+ on D26 |

| 20A.E2, 34 nucleotide differences | Asymptomatic, during a systematic screening | Asymptomatic | ||||||

|

2021 | Bangladesh | A 35–49-year-old man with hypertension | 98 | N/A | Mild | Fever, cough | |

| Milder | Fever, cough, cold | |||||||

|

2021 | Bangladesh | A 35–49-year-old researcher woman | 92 | N/A | Mild | Malaise | |

| Milder | Sore throat, fever, cough, headache | |||||||

|

2021 | Bangladesh | 35–49 hypertensive physician | 94 | N/A | Mild | Fever, headache, sore throat | |

| Mild | Fever, cold, low oxygen saturation | |||||||

|

2021 | Bangladesh | 35–49 man with asthma | 93 | N/A | Mild | Fever | |

| Mild | Fever, cough | |||||||

|

2021 | Bangladesh | 35–49-year-old health worker woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism | 131 | N/A | Mild | Fever, cough | |

| Worse | Chest pain, headache, sore throat, hospitalized | |||||||

|

2021 | Libya | 52-year-old healthy male | 72 | N/A | Mild | Cough, sore throat, fever, myalgias, headache | N/A |

| Worse | Fever, cough, shortness of breath, gastrointestinal symptoms | |||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 40-year-old male doctor | 46 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, cough, sore throat, fatigue, myalgia, headache, diarrhea | IgG and IgM– 42 days after 1 infection |

| Moderate | Fever, cough, sore throat, fatigue, myalgia, headache, diarrhea, anosmia and dysgeusia | IgG and IgM– | ||||||

|

2021 | Panama | 36-year-old man without comorbidities | 181 | A.2.4 | Mild | Myalgia, chest pain, fever, cephalea, rhinorrhea, hyposmia, ageusia | |

| A.2.5 containing Spike mutations D614G and L452R | Milder | Cephalea, myalgia, rhinorrhea | ||||||

|

2021 | France | 25-year-old female healthcare worker | >90 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | No neutralizing antibodies |

| Moderate | Fever, rhinorrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, dysgeusia, anosmia, asthenia, myalgia, eye pain, pharyngitis; not hospitalized | Yes, neutralizing antibodies | ||||||

|

2021 | France | 40-year-old female healthcare worker | >90 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | No neutralizing antibodies |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | No neutralizing antibodies | ||||||

|

2021 | France | 46-year-old female healthcare worker | >90 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, rhinorrhea, cough, dyspnea, chest pain, intestinal disorders, dysgeusia, anosmia, asthenia, headache, myalgia, not hospitalized | Yes, neutralizing antibodies |

| Mild | Fever, cough, dyspnea, chest pain, headache, asthenia, myalgia, pharyngitis; not hospitalized | Yes, neutralizing antibodies | ||||||

|

2021 | France | 31-year-old male healthcare worker | >90 | N/A | Mild | Anosmia; not hospitalized | Yes, neutralizing antibodies |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | Yes, neutralizing antibodies | ||||||

|

2021 | France | 50-year-old female healthcare worker | >90 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | Yes, neutralizing antibodies |

| Mild | Cough, headache; not hospitalized | Yes, neutralizing antibodies | ||||||

|

2021 | Spain | 29-year-old female healthcare worker | 212 | N/A | Mild | 60 days | Seronegative after 1st infection, seroconverted after re-infection |

| Mild | 70 days | |||||||

|

2021 | Spain | 41-year-old female healthcare worker | 154 | N/A | Mild | 61 days | Seronegative after 1st infection, seroconverted after re-infection |

| Milder | ||||||||

|

2021 | Spain | 58-year-old female healthcare worker | 58 | N/A | Mild | 3 days | Unknow after 1st infection, seropositive after reinfection |

| Mild | 3 days | |||||||

|

2021 | Spain | 44-year-old female healthcare worker | 211 | N/A | Mild | 11 days | Seropositive after 1st infection with antibody low-level |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |||||||

|

2020 | USA | 82-year-old male with Parkinson, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hypertension | 48 | N/A | Severe with intubation | Fever, shortness of breath, hypoxia, pneumonia | N/A |

| Severe without intubation | Fever, hypoxia, hypotension, tachycardia, pneumonia | |||||||

|

2021 | Saudi Arabia | 51-year-old man without comorbidities | 58 | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | 7.04 SARS-CoV-2 IgG (Abbot) during second admission | |

| Worse | Fever, cough, generalized weakness, and shortness of breath, bilateral diffuse patchy airspace disease while a CT scan revealed bilateral patchy 4 central and peripheral ground glass opacities most likely related to COVID-19 | |||||||

|

2021 | Saudi Arabia | 55-year-old man with relapsed NHL | 31 | Mild | Mild | 0.01 SARS-CoV-2 IgG (Abbot) index negative during second admission | |

| Worse | High grade fever, dry cough, sore throat, tachycardia and (SPO2) 93% on room air | |||||||

|

2021 | Saudi Arabia | 60-year-old man with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease | 27 | Mild | Mild | N/A | |

| Milder | Cough, shortness of breath | |||||||

|

2021 | Saudi Arabia | 48-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer | 85 | Moderate | Pneumonia | N/A | |

| Mild | Fever, shortness of breath | |||||||

|

2021 | Saudi Arabia | 24-year-old male dental student | 90 | N/A | Mild | Sore throat, cough, headache, nausea, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell, insomnia, loss of appetite, and fatigue, fear and anxiety, increased insomnia, and increased body ache | N/A |

| Mild | Coughing, body ache, loss of taste and smell, and diarrhea symptoms were slightly less severe, the patient was less anxious and slept well. Fever | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 60-year-old man with diabetes | 177 | N/A | Mild | Mild—long term care facility | N/A |

| Moderate | Mild—hospitalized | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 75-year-old man with diabetes, cardiovascular disease | 102 | N/A | Mild | Mild—long term care facility | N/A |

| Severe | Mild—hospitalized | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 72-year-old man with malignity | 205 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 62-year-old woman with asthma | 137 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 57-year-old woman without comorbidities | 203 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 56-year-old woman without comorbidities | 216 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 55-year-old man without comorbidities | 212 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 53-year-old man without comorbidities | 214 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 50-year-old woman with malignity | 197 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 49-year-old woman without comorbidities | 195 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 49-year-old woman without comorbidities | 200 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 47-year-old man without comorbidities | 141 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Moderate | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 47-year-old man without comorbidities | 206 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 46-year-old man without comorbidities | 154 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 46-year-old woman without comorbidities | 231 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 45-year-old woman without comorbidities | 101 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 45-year-old woman with diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, allergy | 196 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 45-year-old woman with cardiovascular disease | 211 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 44-year-old woman with hypertension | 169 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 44-year-old man without comorbidities | 224 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 42-year-old woman without comorbidities | 206 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 39-year-old woman without comorbidities | 229 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 34-year-old man without comorbidities | 158 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 30-year-old woman without comorbidities | 219 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 29-year-old woman without comorbidities | 139 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 27-year-old woman without comorbidities | 172 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 27-year-old woman without comorbidities | 215 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Czech Republic | 25-year-old man without comorbidities | 222 | N/A | Mild | Mild—home | N/A |

| Mild | Mild—home | |||||||

|

2021 | Portugal | 28-year-old man with asthma | 285 | N/A | Mild | Fever, chills, sneezing | N/A |

| Worse | Fever, tiredness, productive cough, frontal headache, dizziness, dark urine, dysuria | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 24-year-old woman without comorbidities | 109 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | No IgG antibodies after first infection |

| P1 variant | Worse | Headache, sore throat, odynophagia, nasal congestion, tiredness, fatigue, chest pain, lack of appetite, hypertension, tachycardia | ||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 54-year-old man without comorbidities | 65 | N/A | Mild | Headache | IgM, IgA, IgG detected <1:4 |

| Clade 20B | Worse | Fever, dry cough, tiredness, body ache, anosmia, ageusia | IgM, IgA, IgG detected 1:128 | |||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 57-year-old woman with discoid lupus erythematous | 61 | Clade 19A | Mild | Mild diarrhea | IgM, IgA, IgG detected <1:4 |

| Clade 20B | Worse | Fever, diarrhea, headache, body ache, anosmia, ageusia | IgM, IgA, IgG detected 1:32 | |||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 34-year-old man without comorbidities | 64 | Clade 20B | Mild | Asymptomatic | IgM, IgA, IgG detected <1:4 |

| Clade 20B | Worse | Fever, nausea, tiredness, headache, body ache | IgM, IgA, IgG detected 1.64 | |||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 34-year-old woman without comorbidities | 60 | N/A | Mild | Mild diarrhea | IgM, IgA, IgG detected <1:4 |

| Clade 20B | Worse | Dry cough, diarrhea, tiredness, headache, body ache, anosmia, ageusia | IgM, IgA, IgG detected 1:64 | |||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 29-year-old health care worker man without comorbidities | 225 | B.1.1.28 Spike D614G |

Mild | Fever, myalgia cough, sore throat, diarrhea | IgG negative 180 days after the 1st infection |

| B,1,2 Spike D614G |

Mild | Again symptoms | ||||||

|

2021 | Mexico | 40-year-old healthcare worker woman with hypertension, smoking | 134 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, dry cough, nasal drainage, dyspnea, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, anosmia, dysgeusia, decreased oxygen saturation up to 84%, maculopapular rash on the upper and lower limbs, chest, face, neck | |

| Worse | Sneezing, runny nose, myalgia, arthralgia, fever, dry cough, headache, dyspnea, emphysema of the right lung | |||||||

|

2021 | Mexico | 49-year-old health care worker woman with hypothyroidism | 129 | N/A | Mild | Nasal congestion, myalgia, arthralgia, chills, headache, dry cough, dysgeusia, anosmia, maculopapular exanthema, insomnia | |

| Mild | Headache, dry cough, odynophagia, myalgia, dyspnea, conjunctivitis | |||||||

|

2021 | Mexico | 53-year-old health care worker man without comorbidities | 107 | N/A | Mild | Fever, dyspnea, pneumonia | |

| Mild | Fever, chills, anosmia, dysgeusia dry cough, rhinorrhea, general malaise, chest pain, | |||||||

|

2021 | Mexico | 52-year-old health care worker man without comorbidities | 82 | N/A | Mild | Odynophagia, dry cough, nasopharyngeal exudate | |

| Worse | Myalgias, arthralgias, dry cough, dyspnea, odynophagia, pneumonia> intensive care for hypoxia | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 30-year-old health care worker man without comorbidities | 90 | N/A | Mild | Fever | 30 days after initial diagnosis IgG antibody negativity |

| Worse | Fever, severe myalgia, anosmia, loss of taste | 30 days after reinfection diagnosis IgG antibody positivity | ||||||

|

2021 | UK | 92-year-old man with dementia | 207 | 1st wave | Moderate | Pyrexia, dry cough, shortness of breath, bilateral pneumonia | |

| B.1.177 (Spain variant) | Moderate | Lethargy, persistent cough, pyrexia, pneumonia | ||||||

|

2021 | UK | 84-year-old man with dementia and Paget’s disease | 224 | 1st wave | Mild | Lethargy, confusion, headache, fatigue | |

| B.1.177 (Spain variant) | Mild | Positive | ||||||

|

2021 | UK | 59-year-old man with end stage renal failure | 236 | 1st wave | Mild | Cough, fluctuating temperature | |

| B.1.1.7 (Kent variant) | none | None | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 59-year-old man with end stage renal failure and hemodialysis | 59 | N/A | Moderate | Cough, fever, pneumonia > hospitalization | |

| Milder | Cough, shortness of breath, >hospitalization | SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody positive after re-infection | ||||||

|

2020 | USA (Washington) | Sexagenarian (age between 60 and 69) with emphysema and hypertension | 140 | Clade 19B | Severe | Fever, chills, productive cough, dyspnea, chest pain | |

| Clade 20A harboring the spike variant D614G | Severe, but milder than first | Dyspnea, dry cough, weakness | RBD, spike and NC IgG, spike IgM, NC IgA+ on D14 of reinfection | |||||

|

2021 | UK | 61-year-old south Asian with immunosuppression for ANCA-associated vasculitis | 180 | N/A | Severe | Dry cough, dyspnea, fever, myalgia, kidney dysfunction, pneumonia | N/A |

| Moderate | Fever, myalgia, dyspnea, pneumonia | |||||||

|

2020 | India | 25-year-old male healthcare worker | 108 | 9 SNVs compared to initial infection (19A first infection–20A second infection) | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic with higher viral load | |||||||

|

2020 | India | 28-year-old female healthcare worker | 111 | 10 SNVs compared to initial infection; mutation 22882T > G (S:N440K) within the receptor binding domain found in the second episode | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic with higher viral load | |||||||

|

2021 | SAU | 44-year-old woman healthcare worker | 108 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, chills, severe sore throat, fatigue | N/A |

| Moderate | Severe persistent productive cough, runny nose, loss of smell, partial loss of taste | |||||||

|

2021 | SAU | 35-year-old heavy male smoker | 94 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Worse | Fever, cough, body ache, abdominal pain, loss of taste | |||||||

|

2020 | Pakistan | 58-year-old cardiac surgeon male without comorbidities | 55 | N/A | Hospitalized for 30 days | Fatigue, headache, sore throat, pneumonia | N/A |

| Hospitalized for 14 days | Fever >39 °C, headache, muscle aches | |||||||

|

2021 | UK | 78-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus, diabetic nephropathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, sleep apnea, ischemic heart disease | 250 | Lineage B.2 with no mutations in the S region | Discharged home | Mild illness | SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (using the Roche anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM/IgG assay detecting antibodies targeting viral nucleocapsid “N” antigen) were detectable on 6 occasions between 4 June 2020 and 13 November 2020 with no evidence of antibody waning seen |

| Variant VOC-20201/01 of lineage B.1.1.7 with 18 amino acid replacement and deletions in the S region | Emergency intubation, worse | Shortness breath, severe hypoxia, pneumonia, myocardial infarction | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 30-year-old female healthcare worker with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, pancreatitis, GERD, anxiety, recurrent pneumonia | 183 | N/A | Mild | Fever, fatigue, sore throat, nasal congestion, dry cough, chest tightness | After 1st infection anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG were negative |

| Mild | Headaches, fever, sinus congestion | After 2nd infection anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG were positive | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 81-year-old woman with immunosuppression for rheumatoid arthritis | 62 | N/A | Mild | Altered mental status, | N/A |

| Moderate | Cough, shortness of breath, oxygen requirement | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 39-year-old man with hypertension | 112 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, dry cough, hypoxemia | SARS-CoV-2 2 months after discharge |

| Mild | Fever, not hypoxemia | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 32-year-old man | 82 | N/A | Mild | Myalgia, fever | N/A |

| Mild | Myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 40-year-old man | 50 | N/A | Severe | Fever, loss of smell, myalgia, dyspnea | N/A |

| Mild | Fever, sore throat | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 46-year-old man | 74 | N/A | Mild | Fever, dry cough | N/A |

| Moderate | Fever, sore throat, loss of taste and smell | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 39-year-old man | 122 | N/A | Severe | Fever, dry cough, dyspnea | N/A |

| Mild | Fever, sore throat | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 32-year-old woman | 174 | N/A | Mild | Fever, dry cough, loss of smell, sore throat | N/A |

| Mild | Fever, sore throat, myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 44-year-old man with colon cancer | 51 | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | N/A |

| Mild | Myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 26-year-old woman | 84 | N/A | Mild | Headache, sweating, loss of taste | N/A |

| Mild | Headache, myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 26-year-old woman | 84 | N/A | Mild | Headache, loss of taste | N/A |

| Moderate | Myalgia, cough, dyspnea | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 36-year-old woman with diabetes | 51 | N/A | Mild | Sore throat, fever | N/A |

| Severe | Fever, myalgia, cough, dyspnea | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 34-year-old man | 49 | N/A | Mild | Headache, fever | N/A |

| Severe | Myalgia, fever, headache, anorexia | |||||||

|

2021 | Iraq | 79-year-old woman with heart failure and hypertension | 58 | N/A | Severe | Fever, dyspnea | N/A |

| Severe | Cough, anorexia, fever | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 59-year-old Caucasian male with Hodgkin lymphoma | 150 | N/A | Moderate | Shortness of breath, dry cough, tachycardia, oxygen desaturation to 85% | N/A |

| Moderate | Chills, worsening shortness of breath, productive cough, fever, tachycardia, hypoxemia | |||||||

|

2021 | Japan | 58-year-old with mild dyslipidemia | 105 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, bilateral pneumonia | After 1st episode IC50 of neutralizing antibodies anti-SARS-CoV-2 was 50.0 microg/mL |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | After 2nd episode IC50 of neutralizing antibodies anti-SARS-CoV-2 was 14.8 microg/mL | ||||||

|

2020 | India | 21-year-old female | 50 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| mild | Complete loss of smell for 2 weeks | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 39-year-old male with multiple myeloma | 84 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Severe | High grade fever, chills, shortness of breath, bilateral pneunomia | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 33-year-old male with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 60 | N/A | Severe | Fever, cough, pneumonia | N/A |

| Severe | Headache, vomiting, high grade fever, pneumonia | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 26-year-old male with Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 91 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Moderate | Fever | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 70-year-old man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease | 45 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | COVID-19 IgG positive after 1st infection |

| Worse | Shortness of breath, cough, chest pain, myalgias | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | Late 50s woman with hypertension, hepatitis C, heart failure | 75 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Worse | Fever, myalgias, sore throat | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 66-year-old man with bipolar disorder, end-stage renal disease due to lithium toxicity and renal transplantation | 210 | Clade B.1 | Mild | Fever, fatigue, dry cough | Failure of humoral immunity with defective response of the neutralizing antibodies after primary infection |

| Clade B.1.280 | Milder | Fatigue and nonproductive cough | ||||||

|

2021 | India | 61-year-old male healthcare worker | 75 | 20B clade | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| 20B clade with 10 variations | Mild | Cough, weakness | ||||||

|

2020 | USA (Virginia) | 42-year-old man military healthcare provider | 64 | Lineage B.1.26 | Moderate, clinical resolution in 10 days | Cough, fever, myalgias | |

| Lineage B.1.26 with several potential variations | Severe, worse | Fever, cough, shortness of breath, gastrointestinal symptoms, pneumonia | Spike IgG+ on D8 of reinfection | |||||

|

2020 | France | 42-year-old Parisian male | 7 months | N/A | Home-managed | Dyspnea, fever, headache, diarrhea, abdominal pain, ageusia, total less of smell | IgG 2 months after |

| Milder | Fever, nasal burning, total loss of taste and smell | |||||||

|

2020 | Spain | 38-year-old Spanish health care worker female | 6 months | N/A | Moderate—hospitalized for 7 days | Dyspnea, fever, headache, diarrhea, loss of smell | N/A |

| Milder | Fever, headache, new total loss of smell and taste | |||||||

|

2020 | South Korea | 21-year-old healthy woman | 26 | Clade V—found in Asia and Europe | Hospitalized with few symptoms | Sore throat | |

| Clade G—found in south Korea | Mild | Cough, sore throat | IgG+ | |||||

|

2021 | Italy | 41-year-old healthcare worker woman | 289 | 20B | Mild | Fever, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, anosmia, ageusia | IgG positive after 1st infection and after 2nd infection |

| 20E (EU1) | Mild | Headache, sore throat, diarrhea | ||||||

|

2021 | UK | 55-year-old man with X-linked agammaglobulinemia | 56 | N/A | Moderate | Purulent sputum, fever, breathlessness, fever, headache, myalgia, chest tightness | N/A |

| Worse | Short of breath, fevers > death | |||||||

|

2020 | Italy | 69-year-old man, heavy smoker with classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma with mixed cellularity | 131 | N/A | Moderate with 3 months of hospitalization | Pneumonia, fever, diarrhea | IgG+ 50 days after hospitalization |

| Moderate with 64 days of hospitalization | Fever, dyspnea, anemia, leukopenia, pneumonia | N/A | ||||||

|

2021 | India | 33-year-old man | 90 | N/A | Mild | Sore throat | N/A |

| Worse | Influenza like Illness symptoms with breathing difficulty | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 27-year-old man | 69 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Worse | Fever, cough, myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 48-year-old woman | 97 | N/A | Mild | Myalgia | N/A |

| Mild | Myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 26-year-old woman | 55 | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgia | N/A |

| Mild | Fever, sore throat, myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 25-year-old man | 89 | N/A | Mild | Fever, sore throat, myalgia and loss of smell and taste | N/A |

| Mild | Fever | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 31-year-old man | 70 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Worse | Myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 51-year-old woman | 157 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Worse | Myalgia, headache, pneumonia (25% lung involvement) | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 16-year-old woman with end-stage renal disease | 90 | B.1.2 | Mild | Sore throat, fatigue, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, dry cough | IgM+ and IgG− after the 2nd infection |

| B.1.1.7 | Milder | Leg pain, fatigue, swelling leg, fever | ||||||

|

2021 | Spain | 62-year-old male healthcare worker with previous history of mild asthma, hypertension, dyslipidemia, liver steatosis, hyperuricemia, and overweight (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 158 | Mild | Fever of 38 °C, diarrhea, anosmia, dysgeusia, cough, intense asthenia, and arthromyalgia | After reinfection weak immune response, with marginal humoral and specific T-cell responses against SARS-CoV-2. All antibody isotypes tested as well as SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies increased sharply after day 8 post symptoms. A slight increase of T-cell responses was observed at day 19 after symptom onset | |

| B.1.79 (G) | Worse | Intense arthromyalgias, headache, fever, cough, and dyspnea > admitted to the emergency room for worsening dyspnea, cough, chills, fever 39 °C, myalgias, anosmia, and ageusia. His respiratory rate was 36 breaths/minute, his heart rate was 100 beats/minute, and he had bilateral inspiratory crackles. The chest radiograph showed bilateral alveolar-interstitial infiltrates | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 53-year-old female with liver transplant in 2010 due to alcoholic cirrhosis, hypertension, hypothyroidism, anxiety, and chronic kidney disease | 90 | N/A | Severe | Encephalopathy due to her COVID-19 | N/A |

| Mild | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and myalgias | |||||||

|

2020 | Denmark | 89-year-old immunocompromised woman (Waldestrom macroglobulinemia) | 59 | The 2 strains differed at 10 nucleotide positions in ORF1a (4), ORF1b (2), spike (2), ORF3A (1), M (1) genes | Hospitalized for 5 days | Fever, severe cough, persisting fatigue | IgM- |

| Worse | Fever, cough, dyspnea > death after 2 weeks | N/A | ||||||

|

2020 | USA | 51-year-old African American male with hypertension and hemodialysis history | 2 months | N/A | Asymptomatic | Positive for NAAT and IgG at a routine control during hemodialysis | IgM−, IgG+ |

| Severe, hospitalized with non-invasive positive pressure mechanical ventilation | Fever 38.3 °C, severe dyspnea, pneumonia | IgG+, IgM+, IgA+ | ||||||

|

2020 | Israel | 22-year-old woman without comorbidities | 111 | N/A | Mild with home back after 23 days | Fever, cough | |

| Asymptomatic | Tachycardia | IgG+ | ||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 29-year-old | 281 | 20A | Mild | Fever, myalgia, cough, sore throat, nausea, and back pain | |

| 20J (P.1) | Mild | Fever, cough, sore throat, diarrhea, anosmia, ageusia, headache, runny nose, and resting pulse oximetry of 97% | ||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 50-year-old | 153 | 20B | Mild | Fever, cough, and tiredness | |

| 20J (P.1) | Mild | Cough, headache, and runny nose | ||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 40-year-old woman | 282 | 20A | Mild | Fever, headache, chest pain, and weakness | |

| 20J (P.1) | Mild | Sore throat and running nose | ||||||

|

2020 | India | 26-year-old man healthcare worker | 97 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 46-year-old man with hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, plantar fasciitis | >90 | N/A | Mild | Fever, myalgias, sore throat, chills, headaches, nausea, shortness of breath | SARS-CoV−2 IgG testing 1st test: 1:4096 (BCM laboratory) |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | SARS-CoV−2 IgG testing 2nd test: 1:2048 (BCM laboratory) | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 27-year-old woman | >90 | N/A | Mild | Congestion, fatigue, loss of taste, loss of smell, headache | N/A |

| Milder | Fever, chills, fatigue | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 53-year-old man with hypertension, sleep apnea | >90 | N/A | Mild | Cough, congestion, loss of taste, loss of smell | SARS-CoV−2 IgG testing 1st test: 1:2048 (BCM laboratory) |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | SARS-CoV−2 IgG testing 2nd test: 1:1024 (BCM laboratory) | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 66-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, congestive heart failure, renal disease, gout, hypertension | >90 | N/A | Mild | Fatigue | N/A |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 73-year-old woman with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression | >90 | N/A | Mild | Congestion, sore throat, headache | N/A |

| Mild | Cough, shortness of breath, congestion, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, headache | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 42-year-old woman with breast cancer | >90 | N/A | Mild | Cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, loss of taste, loss of smell, headache, fever | SARS-CoV−2 IgG testing 1st test: 1:4096 (BCM laboratory) |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 36-year-old man | >90 | N/A | Mild | Cough, fatigue, nausea, loss of smell, fever | SARS-CoV−2 IgG testing 1st test: 1:4096 (BCM laboratory), 2nd test: 1:4096 (BCM laboratory) |

| Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 45-year-old woman | 147 | Lineage B.1.1.33 with S:G1219C mutation | Mild | Diarrhea, myalgia, asthenia, odynophagia for 7 days | N/A |

| Lineage P.2 (or B.1.1.28.2) with S:E484K mutation | Moderate | Headache, malaise, ageusia, muscle fatigue, insomnia, mild dyspnea, shortness of breath | ||||||

|

2021 | Colombia | 44-year-old male, healthcare worker | 103 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| Moderate | Malaise, chills, headache, fever, odynophagia | |||||||

|

2020 | Turkey | 23-year-old woman | 116 | N/A | Hospitalized | Fever >39 °C, chills, fatigue, cough, headache, sore throat, muscle and joint pain | N/A |

| Recovered in 10 days | Fever 28.7 °C, chills, fatigue, loss of appetite, taste and smell loss, muscle and joint pain | IgG slightly positive | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 40-year-old man | 89 | N/A | Mild | Fever, cough | N/A |

| Worse | Dyspnea, tachycardia > death | |||||||

|

2020 | Ecuador | 46-year-old man | 63 | Nextstrain 20A/GISAID B1.p9 lineage | Mild | Intense headache, drowsiness | IgM+ IgG− on D7 of initial infection |

| Nextstrain 19B/GISAID A.1.1 lineage; 18 mutations difference | Moderate | Odynophagia, nasal congestion, fever 39 °C, back pain, productive cough, dyspnea | IgM+ IgG+ on D28 | |||||

|

2021 | Spain | 60-year-old male, with chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis that received his first kidney transplant 2004 |

149 | N/A | Mild | Cough and low-grade fever | Antibodies (IgM and IgG) for SARS-CoV2 resulted negative after reinfection |

| Worse | Respiratory fever and acute injury of the allograft function. A chest X-ray showed bilateral infiltrates with unilateral pleural effusion > death | |||||||

|

2021 | Colombia | 54-year-old woman with hypertension, gastritis, arthrosis | 33 | B.1 | Mild | Fever, cough, odynophagia, fatigue | N/A |

| B.1.1.269 | Milder | Fever, odynophagia | ||||||

|

2021 | India | 47-year-old man | 46 | 15 genetic variants with 22882T > G (Spike N440K) | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| 17 genetic variants with 22882T > G (Spike N440K) | Worse | Fever, cough, malaise | ||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 37-year-old healthcare worker woman | 116 | B.1.1.33 | Mild | Headache, runny nose, diarrhea, myalgia | IgG+ after re-infection |

| VOI P.2 with mutation S-E484K | Mild | Headache, ageusia, anosmia, fatigue | ||||||

|

2021 | Spain | 76-year-old man with hypertension, biological aortic heart valve replacement, and end-stage kidney disease secondary to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | 58 | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | IgG and IgM to SARS-CoV-2 tested negative after 1st and 2nd episode | |

| Worse | Fever, cough, and shortness of breath, bilateral pneumonia > death 18 days after admission | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 26-year-old woman | 128 | Non-VOC virus | Mild | Dry cough, dizziness, headache, fatigue, stuffy nose, back pain, loss of taste, nausea, diarrhea | |

| VOC-virus P.1 variant | Mild | Dry cough, dizziness, headache, fatigue, diarrhea, joint pain legs, difficult breathing | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 62-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism, chronic lower back pain | 90 | N/A | Hospitalized | Worsening shortness of breath, cough, hypoxia | N/A |

| Worse with intubation twice | Tachypnea, hypoxia, pneumonia | |||||||

|

2021 | Iran | 42-year-old man | 128 | 20G with 11 mutations | Mild | Cough, headache, severe diarrhea | IgG and IgM negative |

| 20G with 17 mutations | Mild | Body pain, shortness of breath, headache, anosmia | IgG and IgM negative | |||||

|

2021 | Iran | 32-year-old woman | 63 | N/A | Mild | Headache, sore throat, cough, fever | The antibody titration was achieved positive by the rapid test (sensitivity 72%, specificity: 76%) for IgM (At the time of second infection, IgG titration was assessed as 4.89 AU/mL which after two months turned to a significant raise (over ELISA reader standard range). |

| D614G mutation | Worse | Severe cough, fever, fatigue | ||||||

|

2021 | Iran | 54-year-old man | 156 | L139L non-synonymous mutation | Mild | Fatigue, anxiety, chest pain, cough, fever | IgM and IgG were detected in the first incidence, and he was being followed up to the second virus presentation. In the whole duration between two incidences, IgG test was positive. Antibody titration at the time of second infection showed that IgG level was 5.25 IU/mL which increased to 27.5 IU/mL after about 2 weeks. |

| L139L non-synonymous mutation | Mild | Milder fatigue, chest pain, dizziness, diarrhea | ||||||

|

2021 | Iran | 42-year-old man | 111 | N/A | Mild | Shortness of breath, sore throat, shaking chills, pain, diarrhea | The IgG titration was 17.5 IU/mL which decreased to 6.5 IU/mL after almost 2 weeks. |

| D614G mutation | Mild | Similar to the first infection with severe diarrhea | ||||||

|

2021 | Austria | 95-year old man with dementia, hypertension, total thyroidectomy | 124 | N/A | Mild | Fever, leukopenia | N/A |

| Severe | Pneumonia | |||||||

|

2021 | Gambia | 31-year-old woman without comorbidities | 145 | B1 | Mild | Mild | |

| B1.1.74 | Mild | Mild | ||||||

|

2021 | Gambia | 36-year-old woman without comorbidities | 184 | B.1.235 | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |

| B.1 | Worse | Mild | ||||||

|

2021 | Italy | 63-year-old healthcare man with type II diabetes, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 299 | Clade 20A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | |

| Clade 20E | Worse | Shortness of breath with rapid worsening of clinical presentation and recovering in intensive care unit > death | ||||||

|

2020 | Belgium | 39-year-old female immunocompetent healthcare worker | 185 | Different clades: 19A | Mild | Cough, dyspnea, headache, fever, general malaise | IgG+ |

| 20A | Milder | Dyspnea | IgM and IgG+ | |||||

|

2020 | USA | 70-year-old male with obesity, neuropathy, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension | 7 months | N/A | Hospitalized | Worsening shortness of breath, tachypneic, mild, patchy mid and lower lung airspace disease bilaterally | SARS-CoV-2 IgG− |

| Hospitalized | Shortness of breath, fever, body aches, nausea, malaise | |||||||

|

2020 | India | 78-year-old man with coronary artery disease | 57 | N/A | Mild | Fever, cough for 2 days | N/A |

| Mild | Fever, cough, dyspnea for 1 day | |||||||

|

2021 | Ecuador | 28-year-old man | 102 | B.1.1 | Mild | Sore throat, cough, headache, nausea, diarrhea, anxiety, panic attack | IgM and IgG negative after 1st infection |

| Different in 27 nucleotides | Mild | Anosmia, ageusia, fever, headache | IgM and IgG negative after 2nd infection | |||||

|

2020 | Qatar | 57-year-old male with diabetes mellitus | 86 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic, screening for exposition to an infected work colleague | N/A |

| Symptomatic | Fever, myalgia, headache, productive cough | IgM and IgG+ | ||||||

|

2021 | India | 27-year-old male doctor | 66 | Lineage B.1 | Mild, 2 days of symptoms | Sore throat, nasal congestion, rhinitis | N/A |

| Lineage B with 7 differences | Mild, worse than initial (1 week) | Myalgia, fever, non-productive cough, fatigue | Abbott anti-NC IgG− on D5 of reinfection | |||||

|

2021 | India | 31-year-old male doctor | 65 | Lineage B.1.1 | Asymptomatic | Nothing | N/A |

| Lineage B.1.1 with 8SPSs in initial strain compared to reference not present in reinfection strain including D614G | Mild, worse than initial (2 days) | Myalgia, malaise | Abbott NC IgG− on D7 of reinfection | |||||

|

2021 | India | 27-year-old male doctor | 19 | Lineage B.1.1 | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic—screening prior going home to visit parents | N/A |

| Lineage B.1.1 with 9 SNPs compared to reference not present in initial infection strain including D614G | Mild | Fever, headache, myalgia not productive cough | IgG/IgM/IgA− | |||||

|

2021 | India | 24-year-old woman nurse | 55 | Lineage B.1.1 | Mild, 5 days | Sore throat, rhinitis, myalgia | N/A |

| Lineage B.1.1 with 10SNPs compared to reference not present in initial infection strain including D614G | Mild, worse than initial—3 weeks | Fever, myalgia, rhinitis, sore throat, not productive cough, fatigue | IgG/IgM/IgA− | |||||

|

2021 | USA | 31-year-old healthcare worker man | 79 | N/A | Severe | Malaise, cough, shortness of breath, anosmia, =2 saturation to 88%, pneumonia | N/A |

| Milder | Malaise, aphthous gingival ulcer, desquamating palmar lesion, fever, myalgia | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | 69-year-old woman with asthma, hypercholesteremia, hypertension, OSA (obstructive sleep apnea) | 70 | N/A | Mild | Shortness of breath, dry cough, headache, fatigue, fevers | N/A |

| Moderate | Cough, fever, ageusia | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 76-year-old woman with chronic renal failure and renal squamous cell carcinoma | 104 | 9 single nucleotide variations (SNVs) | Severe | Cough, fever, pneumonia | N/A |

| Worse | Cough, fever, pneumonia > death | |||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 39-year-old man with chronic cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus | 101 | P.1 | Not reported | Not reported | N/A |

| P.2 | Worse | Dyspnea, fatigue, respiratory distress > intubated > death 12 days after the onset of symptoms | ||||||

|

2021 | France | Mid-20s healthcare worker man without comorbidities | >83 | November N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | N/A |

| B1.351—identified in December 2020 in South Africa | Worse | Cough | ||||||

|

2021 | France | Mid-20s healthcare worker woman without comorbidities | 288 | April 2020—N/A | Mild | Fever, headache, chills, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell | N/A |

| B1.351 | Milder | Fever, headache, chills | ||||||

|

2021 | France | Late-20s healthcare worker woman without comorbidities | 90 | November 2020—N/A | Mild | Fever, muscle pain, headache, loss of taste and smell | N/A |

| B1.351 | Milder | Cough, muscle pain | ||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 29-year-old man healthcare professional without comorbidities | 53 | N/A | Mild | Myalgia, fever | N/A |

| Mild | Fever, anosmia, loss of taste | |||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 63-year-old man healthcare professional without comorbidities | 58 | N/A | Mild | Diarrhea, fever | N/A |

| Mild | Hypoxemia, fever | |||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 40-year-old woman healthcare professional with ankylosing spondylitis and asthma | 70 | N/A | Moderate | Fever, Pneumonia, myalgia | Not specified |

| Mild | Anosmia, fever | |||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 67-year-old man healthcare professional with obesity, apnea syndrome, rhinitis | 54 | N/A | Mild | Coryza, arthralgia | Not specified |

| Hospitalized with high-flow oxygen therapy | Hypoxia | |||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 47-year-old man healthcare professional without comorbidities | 56 | N/A | Mild | Myalgia, fever | Not specified |

| Mild | Fever | |||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 31-year-old man healthcare professional without comorbidities | 57 | N/A | Moderate | Hypoxemia, myalgia, diarrhea, fever | Not specified |

| Moderate | Hypoxemia, fever | |||||||

|

2021 | USA | Female in 20s with asthma, obesity, anxiety, depression | 19 | PANGOLIN A.3 lineage | Mild | Cough, chills, exertional dyspnea, sore throat, dizziness, rhinorrhea, fever | N/A |

| PANGOLIN B.1.1 lineage | Milder | |||||||

| Cough, fatigue, dyspnea | ||||||||

|

2021 | Iran | 15-year-old boy with acute myeloid leukemia M3 | 43 | N/A | Moderate | Cough, dyspnea, patchy infiltration in the left lung | IgG+ IgM− |

| Severe | Fever, neutropenia, cough, myalgia and shivering, O2 saturation at 75%, pneumonia | IgG− | ||||||

|

2021 | Libya | 18-year-old man | 80 | N/A | Mild | Fever, headache, sore throat, cough, shortness of breath, anosmia | IgG positive after re-infection |

| Worse | Fever, cough, muscle pain, dyspnea, hypoxia | |||||||

|

2020 | USA (Nevada) | 25-year-old man without comorbidities | 48 | Clade 20C | Mild | Sore throat, cough, headache, nausea, diarrhea | N/A |

| Clade 20C with 11SNP mutation | Severe with hospitalization | Fever, headache, dizziness, cough, nausea, diarrhea, hypoxia, shortness of breath | Roche Elecsys Anrti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM/IgG+ on D8 of reinfection | |||||

| 2020 | Hong Kong | A 33-year-old male | 142 | Nextstrain 19A/GISAID V/Pangolin lineage B.2 | Mild—hospitalized | Fever, headache, cough, sore throat | IgG negativity by ELISA or microsphere based antibody assay 10 days post symptom onset; IgG positivity but IgM negativity by indirect immunofluoresence assay; neutralizing antibody presence 10 days post-symptom onset with conventional and pseudovirus-based neutralization tests (VNTs) | |

| Nextstrain 20A/GISAID G/Rambout B.1.79; 24 nucleotides difference | Asymptomatic, systematic screening | Asymptomatic | IgG negativity by ELISA or microsphere based antibody assay 1 day post-hospitalization, but positivity at day 5; absence of neutralizing antibodies by VNTs and IgM negativity by IFI assay and CLIA 1 day post-hospitalization; then positivation on day 3; neutralizing antibody detection on day 3; IgG detection by IFon day 3; high affinity IgG | |||||

|

2021 | USA | 61-year-old man with liver transplant due to chronic hepatitis B and C infections | 111 | Genome of 2nd episode differed by 11 to 12 single base substitutions | Mild | Fever, nausea, vomiting, cough | |

| Worse | Confusion, hallucination, lethargy, hypoxia | Anti-SARS-CoV-2 assay positive after 2nd episode | ||||||

|

2021 | UK | 93-year-old British male with multiple myeloma, cognitive impairment | 55 | N/A | 14 days—hospitalized | Lethargy, reduced appetite, diarrhea | |

| Cough, fever, dyspnea | Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG+ on D58 | |||||||

|

2021 | UK | 82-year-old British male with atrial fibrillation, congestive cardiac failure, abdominal aortic aneurism, lung cancer, diabetes | 87 | N/A | Mild—hospitalized | Fever, cough, sore throat, dyspnea, hemoptysis, hypoxia | |

| Milder | Fever, cough, dyspnea | Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG+ on D88. 92 | ||||||

|

2020 | Brazil | 36-year-old female medical doctor without comorbidities | 87 | N/A | Moderate | Rhinorrhea, sore throat, low fever, diarrhea, asthenia, mild headache, erythematous vesicles on her right calf, severe musculoskeletal pain of the lower limbs, hyperesthesia | IgG− 23 days after the onset, IgM/IgG− after 33 and 67 days from onset |

| Worse | Nasal obstruction, hyaline rhinorrhea, sudden and complete anosmia and ageusia, frontal headache and asthenia, pneumonia | IgG+ at the 20th day | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 44-year-old Hispanic man with type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity | 4 months | N/A | Severe with tracheostomy | Dyspnea, stridor, difficulty at breath, | IgG+ |

| Mild | Fever, respiratory decompensation | |||||||

|

2020 | Pakistan | 41-year-old healthcare worker man | 133 | N/A | Mild | Fever, oxygen saturation of 90–92%, bilateral lung infiltrates, mild shortness of breath, loss of taste, severe restlessness, insomnia, body-aches | SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: 1.97 |

| Milder | Fever, moderate shortness of breath, loss of smell, moderate restlessness, insomnia, body aches | SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: 0.08 | ||||||

|

2020 | Belgium | 51-year-old woman with asthma | 93 | Pangolin Lineage B.1.1 | Moderate with self-quarantine for 2 weeks | Headache, myalgia, fever, cough, chest pain, dyspnea; some persisting symptoms for 5 weeks | N/A |

| Lineage A; 11 nucleotide differences | Milder with resolution in 1 week | Headache, cough, fatigue, rhinitis | Roche nucleocapsid IgG+ on D7 of reinfection | |||||

|

2021 | Switzerland | 36-year-old female physician | 205 | Clade 20A | Mild | Asthenia, headache, slight memory loss | Positivity for anti-S1 IgG and anti-N Ig at 14th and at 30th days |

| Clade 20A.EU2 with non-synonymous mutation in the S (S477N) | Mild | Asthenia, shivering, rhinorrhea, anosmia, arthralgia, headache, exertional dyspnea for 10 days | Positivity for anti-S1 IgG and anti-N Ig | |||||

|

2021 | India | 58-year-old woman with hypertension, hypothyroidism | 120 | N/A | Mild | Fever, generalized body ache, running nose, soreness of throat | Total antibody and immunoglobulin G antibody test for COVID-19 were negative after first infection |

| Milder | Fever, generalized body ache, dry cough, throat pain | |||||||

|

2021 | India | 58-year-old woman with hypertension and hypothyroidism | 91 | N/A | Mild | Low-grade intermittent fever, generalized body ache, running nose and soreness of throat | N/A |

| Mild | Intermittent fever, generalized body ache, dry cough, and throat pain | |||||||

|

2021 | UK | 25-year-old male UK doctor | 17 | N/A | Mild | High-grade fevers, headache of 3-day duration, severe fatigue lasting 3 weeks | N/A |

| Milder | Fatigue, coryzal symptoms for 4 days | Rest at home | ||||||

|

2021 | USA | 25-year-old female medical student with vitiligo | 120 | N/A | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | IgG+ |

| Severe | Fever, abdominal pain, fatigue, vomiting and fulminant myocarditis with co-infection of parvovirus and SARS-CoV-2 | N/A | ||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 41-year-old woman with gastroplasty history | 146 | B.1.1.33 lineage | Mild | Headache, myalgia, fatigue, fever, dry cough, shortness of breath, anosmia, loss of taste | N/A |

| B.1.1.28 lineage | Mild | Headache, myalgia, fatigue, fever, dry cough, shortness of breath, anosmia, loss of taste, diarrhea, loss of appetite, dizziness | ||||||

|

2021 | Brazil | 34-year-old healthcare worker woman with chronic respiratory disease | 173 | B.1.1.28 lineage | Mild | Fever, cough, odynophagia, dyspnea | N/A |

| P2 | Mild | Headache, running nose, fever, sore throat | ||||||

|

2021 | Iran | 50-year-old man | 230 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

2021 | Iran | 81-year-old woman | 234 | N/A | Moderate | N/A | N/A |

| Worse | Death for COVID-19 | |||||||

|

2021 | Iran | 42-year-old woman | 107 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

2021 | Iran | 27-year-old man | 115 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

2021 | Iran | 79-year-old man | 150 | N/A | Moderate | N/A | N/A |

| Worse | Death for COVID-19 | |||||||

|

2021 | Iran | 86-year-old man | 164 | N/A | Moderate | N/A | N/A |

| Worse | Death for COVID-19 | |||||||

|

2021 | Iran | 90-year-old woman | 130 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

2021 | Iran | 13-year-old woman | 124 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

2020 | China | 33-year-old female | 59 | N/A | Moderate—hospitalized for 16 days | Reduction of IgG+ to − | |

| Moderate | IgG+ | |||||||

|

2020 | China | 33-year-old female | 86 | N/A | Severe—hospitalized for 38 days | Reduction of IgG+ to weak+ | |

| Moderate | IgM+ and IgG+ | |||||||

|

2021 | South African | 58-year-old male with asthma | 120 | N/A | Mild | Dyspnea, fever | IgG+ |

| South African variant 501Y.V2 | Severe with intubation and mechanical ventilation | Dyspnea, fever, severe acute respiratory distress syndrome |

* data from papers which are not certified by peer review, medRxiv or Research Square preprints. ** days from recovery not from 1 infection. NAAT: nasopharyngeal nucleic acid amplification test; AT: antibody test.

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Features of Reinfection Cases

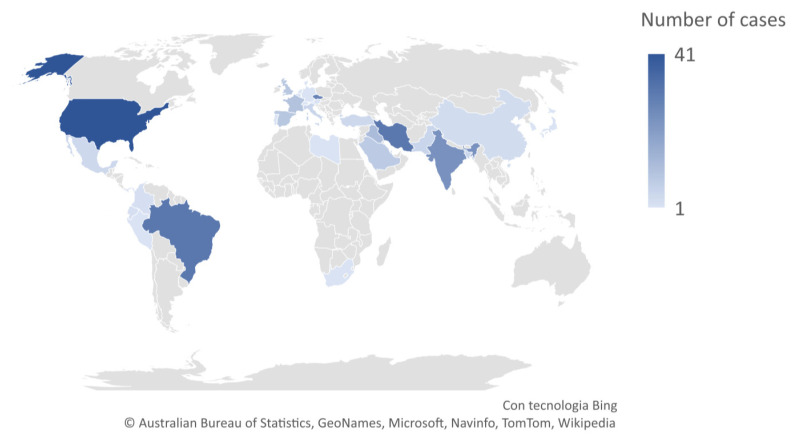

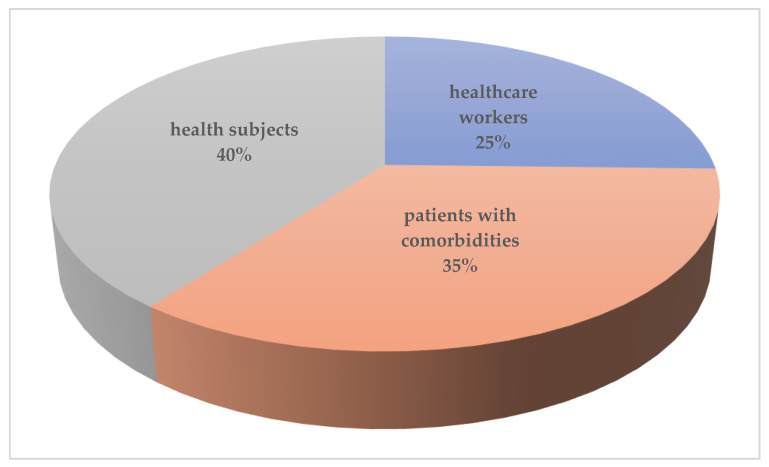

Reinfection occurred across the world: 1 case from Austria, 1 from Bahrain, 5 from Bangladesh, 2 from Belgium, 31 from Brazil, 3 from China including 1 from Hong Kong, 2 from Colombia, 28 from the Czech Republic, 1 from Denmark, 2 from Ecuador, 10 from France, 2 from Gambia, 1 from Germany, 24 from India, 31 from Iran, 12 from Iraq, 1 from Israel, 5 from Italy, 1 from Japan, 1 from Lebanon, 1 from Libya, 4 from Mexico, 5 from Pakistan, 1 from Panama, 1 from Peru, 1 from Portugal, 6 from Qatar, 1 from South Korea, 1 from Switzerland, 8 from Saudi Arabia, 1 from South Africa, 9 from Spain, 1 from the Netherlands, 4 from Turkey, 9 from the United Kingdom, 42 from the United States of America (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of cases worldwide.

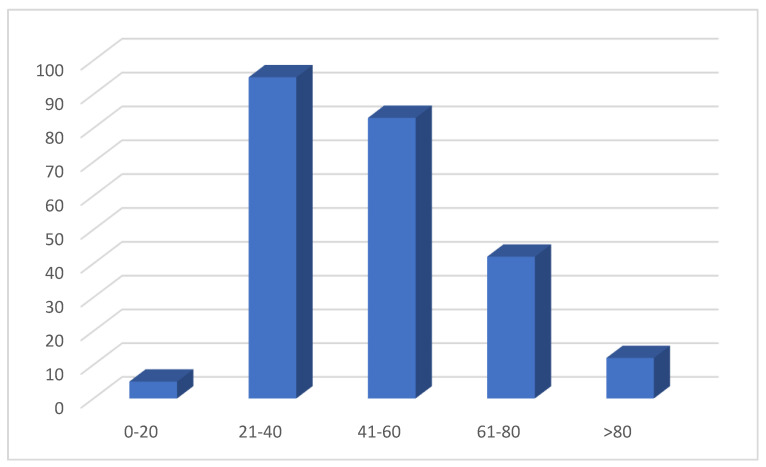

Age was reported in 237 cases: 5/237 patients (2.1%) were between 0 and 20 years old, 95/237 (40%) between 21 and 40 years old, 83/237 (35%) between 41 and 60, 42/237 (17%) between 61 and 80, and 12/237 (5%) > 80 years old (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of cases according age.

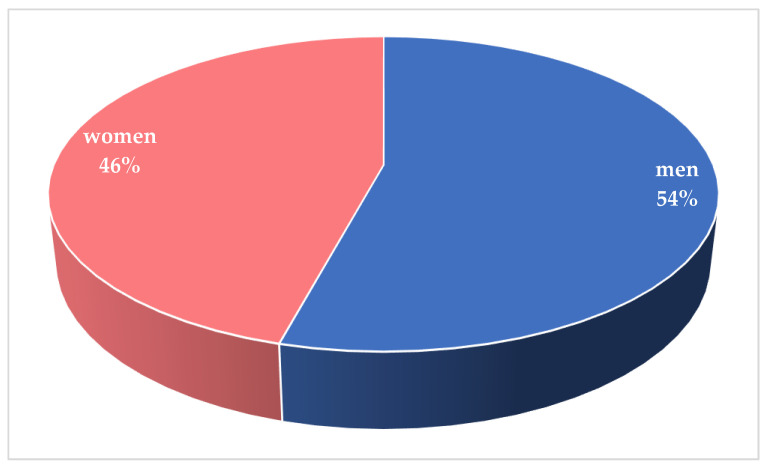

Gender was reported in 251/260 cases, among which 115/251 patients (45.8%) were female and 136/251 (54.2%) were male (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of cases according sex.