Abstract

Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) has increased substantially since the industrial revolution began, and physiological responses to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations reportedly alter the biometry and wood structure of trees. Additionally, soil nutrient availability may play an important role in regulating these responses. Therefore, in this study, we grew 288 two-year-old saplings of sessile oak (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) in lamellar glass domes for three years to evaluate the effects of CO2 concentrations and nutrient supply on above- and belowground biomass, wood density, and wood structure. Elevated CO2 increased above- and belowground biomass by 44.3% and 46.9%, respectively. However, under elevated CO2 treatment, sapling wood density was markedly lower (approximately 1.7%), and notably wider growth rings—and larger, more efficient conduits leading to increased hydraulic conductance—were observed. Moreover, despite the vessels being larger in saplings under elevated CO2, the vessels were significantly fewer (p = 0.023). No direct effects of nutrient supply were observed on biomass growth, wood density, or wood structure, except for a notable decrease in specific leaf area. These results suggest that, although fewer and larger conduits may render the xylem more vulnerable to embolism formation under drought conditions, the high growth rate in sessile oak saplings under elevated CO2 is supported by an efficient vascular system and may increase biomass production in this tree species. Nevertheless, the decreased mechanical strength, indicated by low density and xylem vulnerability to drought, may lead to earlier mortality, offsetting the positive effects of elevated CO2 levels in the future.

1. Introduction

Global atmospheric CO2 concentration has increased by more than 45% since the industrial revolution began, reaching above 410 ppm in 2020 [1]. By and large, this substantial increase has been caused by CO2 released from anthropogenic emissions, such as the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and other land-use changes. Currently, the average rate of increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration is 2 ppm per year, whereby the global atmospheric CO2 level is likely to increase to 550–1000 ppm by the end of the century [2], depending on the success of our efforts to reduce CO2 emissions [3]. Further, elevated CO2 concentrations (hereafter, eCO2) are the main cause of global warming and are predicted to cause an increase in air temperature from 2 to 5 °C by the end of the 21st century [3]. Through photosynthesis, forests sequester approximately 26% of anthropogenic carbon emissions each year [4], thus playing an important role in preventing global warming. Additionally, an increase in anthropogenic nitrogen deposition enhances soil nitrogen availability, which may reportedly hinder the CO2-sequestering ability of plants [5, 6].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the effects of eCO2 levels on plant growth and function over the last few decades [7–12], wherein increased atmospheric CO2 levels were shown to improve tree growth through a process known as the “fertilisation effect”. Photosynthesis is directly influenced by variations in CO2 concentrations and is one of the most studied physiological processes. Previous studies have shown that at the leaf level, eCO2 concentrations increase photosynthesis rates while reducing stomatal conductance, thereby enhancing water use efficiency (WUE) [13–16]. The carbohydrates produced in the process serve as the building blocks for plant biomass production and many other processes in which carbon is metabolised [17]. Therefore, the enhancement of photosynthesis and the resulting carbohydrate surplus promoted by eCO2 levels lead to a consistent increase in biomass growth. However, these effects have been mostly observed in young saplings [10, 14, 18], whereas mature trees usually do not show a positive growth response to eCO2 levels [19]. In addition, growth stimulation by eCO2 may be limited by the progressive scarcity of soil nutrients, particularly nitrogen [20–24]. Indeed, the effects of N deficiency on eCO2-induced growth stimulation are evident in plants growing on severely nutrient-deficient substrates [25]. Thus, any generalisation of plant responses to nutrient unavailability under eCO2 levels is difficult to make [13].

Although previous studies have investigated the effects of eCO2 levels on plant physiological and growth responses, few studies have addressed the changes in wood structure resulting from elevated CO2 concentrations [26]. Furthermore, the changes in the physiology and growth of a plant not only alter the internal water balance [27] but also affect the structure and functioning of tracheids and vessel elements in the secondary xylem [28, 29] as well as xylem hydraulic conductance [30]. Nonetheless, the effects of eCO2 levels on xylem elements vary among species. For instance, the tracheid lumen area in coniferous species such as Larix sibirica Ledeb. [31] and Pinus sylvestris L. [29] increased under eCO2 levels. In contrast, diffuse-porous tree species were less responsive to eCO2 levels and no effect was observed on the vessel area in Populus tremuloides Michx. [32], Betula pendula Roth. [33], or Fagus sylvatica L. [34]. Moreover, the lesser-investigated ring-porous tree species showed inconsistent results under eCO2 levels, for example, increased vessel area in Quercus robur L. [35] but no changes in Quercus mongolica Fisch. Ex Ledeb. [28, 36]. Nevertheless, Watanabe et al. [28] also observed wider vessels and higher hydraulic conductance in Q. mongolica trees grown in N-rich soil regardless of CO2 concentration.

The lumen area of xylem conduits is an important factor that influences not only the water flux capacity of xylem [37] but also wood density. Wood density is a key determinant of plant ecological strategies [38], including both hydraulic and mechanical strategies, as denser wood is more resistant to cavitation and is stiffer and less susceptible to wind damage [39]. Increased plant growth rate is another wood density-related factor associated with lower wood density [40–42] that renders fast-growing trees more susceptible to high winds [43]. Information about the effect of eCO2 on wood density is rather scarce in the literature. Conifers are known to exhibit higher wood density under eCO2, owing to their characteristically higher proportion of latewood. In contrast, angiosperms show no changes in wood density under eCO2 levels [26]; however, they have been much less studied.

Therefore, with the simultaneous increase in CO2 levels and nitrogen deposition in the coming decades, forest ecosystems will face many challenges that will force plants to adapt to warmer temperatures, higher evaporative demand, and increased frequency and severity of drought events [44]. Nonetheless, as difficult as it may seem to predict how forests will respond to these changes, the range of tree species in Central Europe will likely be substantially altered from the presently dominant conifers, to angiosperms, particularly thermophilous oak species [45, 46].

Sessile oak (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.), a broad-leaved, ring-porous tree species, is widespread in the temperate zone and is one of the most ecologically and economically important hardwood tree species in Central Europe [47, 48]. Owing to the morphological (deep rooting, leaf curling, and leaf loss) and physiological (osmotic adjustment and stomatal control to reduce transpiration water loss) mechanisms to overcome drought stress [49, 50], sessile oaks are considered well adapted for future climate scenarios [51, 52].

Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the effects of (i) eCO2 concentration and (ii) nutrient supply on biomass growth, wood density, and wood structure of the conductive tissue in sessile oak saplings. Our main hypothesis was that the growth of sessile oak saplings will be stimulated by the fertilisation effect of eCO2. Previous studies have reported that higher growth rates in sessile oak in Western and Central Europe are associated with lower wood density [41, 42, 53]; accordingly, we tested the hypothesis that eCO2 concentration is the cause for the observed morphological difference. Furthermore, it was expected that the higher growth rates would be followed by altered wood anatomy, which in turn would be reflected in a larger more efficient conductive system. Finally, we also hypothesised that the magnitude of the CO2 fertilisation effect is regulated by nutrient supply.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

The experiment was conducted in two neighbouring glass domes (area: 10 × 10 m2; central height: 7 m) in the Bílý Kříž experimental ecological station situated in the Moravian-Silesian Beskydy mountains (49°30’77″ N, 18°32’28″ E; Elevation: 908 m asl). The mean air temperature and the mean precipitation during the period 1998–2014 were 6.8 °C and 1,260 mm, respectively. The soil type is ferric podzol, overlying the Mesozoic Godula sandstone (flysch-type), which is moderately rich and has a high humus content (5%–7%).

Under the scenario that has most closely tracked human historical emission trajectories, the atmospheric CO2 concentrations will reach approximately 550 to 700 ppm by the middle-to-late 21st century [2, 3]. Previous studies on the effect of elevated CO2 on different tree species were conducted mostly based on these concentrations [16, 54, 55], whereas more pessimistic predictions of 900–1000 ppm, which are expected by the end of 21 century, have been rarely used [13, 18]. In our study, ambient CO2 (hereafter aCO2) and eCO2 treatment concentrations in the open-top glass domes were 400 and 700 ppm, respectively, and CO2 was continuously supplied from April to November, from 2017 to 2019. The design and installation of the glass domes was as described previously [56]. The microclimatic conditions inside the two domes were maintained at similar levels, as shown by the non-significant differences in temperature (p = 0.953) and relative air humidity (p = 0.485). The soil inside the glass domes was natural and not mechanically altered, representing the same soil type as at the study site.

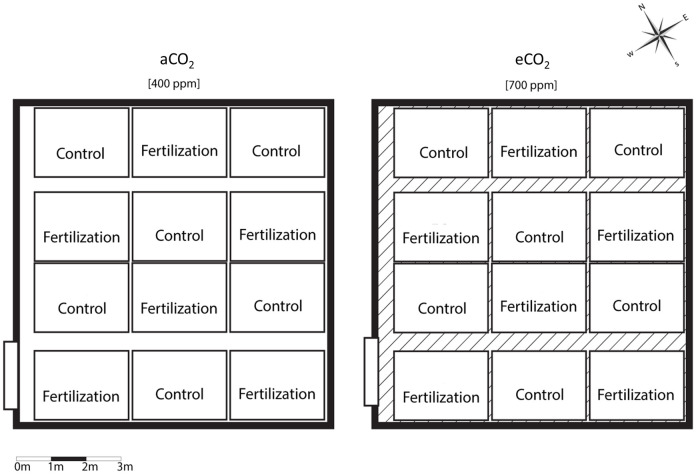

A total of 144 two-year-old sessile oak saplings were planted in each glass dome in 2017, following a specific fertilisation experimental design (Fig 1). Each glass dome was split into twelve blocks: no fertiliser was added to six blocks (control), while the other six blocks were annually supplied with calcium nitrate (AGRO, Czech Republic) containing 15% nitrogen, at a rate of 5 g m-2 year-1 in mid-April during the study period (2018–2019).

Fig 1. Experimental design scheme.

aCO2—ambient CO2 concentration, eCO2—elevated CO2 concentration, Control—plots without nutrient supply, Fertilization—plots with nutrient supply.

2.2. Sampling and biometrical analyses

At the end of the growth season of 2019, we sampled all (72 per treatment) sessile oak saplings to compare their biometric characteristics. Before harvesting, plant height (H, cm) and stem diameter at a height of 5 cm above the ground (D0.05m, mm) were recorded, and the cross-sectional area (CSA, cm2) was calculated using D0.05m. Then, ten fresh leaves were randomly selected from the upper, middle, and bottom parts of the crown of each harvested oak sapling, scanned, and oven-dried at 70 °C to measure their dry biomass using a precision scale (Radwag PS 6000.R1; precision: 0.01 g). Then, the specific leaf area (SLA; cm2 g-1) was calculated according to procedure described by Pietras et al. [42].

Subsequently, the above- and belowground biomass fractions of all samples were subdivided into leaves, branches, stems, and roots, which were further subdivided into coarse (> 2 mm) and fine roots (≤ 2 mm), based on root diameter. After measuring their fresh weight, the fractions were oven-dried at 70 (leaves) and 105 °C (woody biomass) to constant weight [57], and their dry biomass (g plant-1) were measured. Then, SLA and leaf biomass were used to calculate the leaf area (LA, m2 plant-1) of each plant.

2.3. Wood density

To determine the density of oven-dried wood, 5–8 cm long wood segments from a height of 10 cm above the ground were collected from all saplings and oven-dried (as described above). Their dry biomass and volume were measured using a digital scale (see above) and the water displacement method based on the Archimedes’ principle; briefly, a container filled with water was placed on the digital scale calibrated to the nearest 0.01 g and re-zeroed. The pith of each oven-dried wood segment was connected to a needle, and the segment was immersed into the water, ensuring that it did not touch the sides or bottom of the container. The weight of the water displaced was equal to the volume of the oven-dried segment, as 1 g of displaced water was equivalent to 1 cm3. Subsequently, the wood density (WD, g cm-3) of the oven-dried sample was calculated as the dry biomass of the wood sample divided by its volume [29].

2.4. Anatomical measurements

Immediately after harvesting, 1.8 mm thick microcores were collected from the base of the stems of 18 saplings per treatment using a Trephor increment borer [58]. Following the methodology of Fajstavr [59], the samples were dehydrated in successive baths of ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Then, 8–12 μm thick transverse wood sections were cut using a rotary microtome, stained in safranin and astra blue solutions, and mounted in Euparal. The cross-sections were then photographed using a digital video camera (Zeiss Axiocam 305 colour) attached to a light microscope (Zeiss Axio scope A1) at 100 × magnification.

Two to three sectors of the outermost ring, formed in 2019 (third year of CO2-enrichment experiment), from each cross-section were used to measure the width of the growth ring (RW) and the vessel lumen area (VLA) using ImageJ version 1.52a [60]. Cells with a lumen area ≤ 200 μm2 were excluded to distinguish xylem vessels from other cell types [61]. Then, average VLA, vessel density (VD; n mm-2), total vessel lumen area (TVA; μm2), and the proportion of TVA per analysed sector (PTVA; %) were calculated as described by Lotfiomran et al. [34]. The lumen diameter of each circular vessel was derived from VLA and used to calculate their hydraulically weighed diameter (Dhp, μm) according to the equation: , where D is the diameter of the vessel and N is the number of vessels [37]. The potential specific hydraulic conductivity of vessels (KS; kg m-1 s-1 MPa-1) was calculated using the Hagen–Poiseuille equation [62]: where η is the viscosity of water (1,002 × 10−9 MPa s), ρ is the density of water (998.21 kg m-3), Dhp is the hydraulically weighed diameter of vessels, and VD is the mean vessel density. The potential hydraulic conductivity of a growth ring (Kring; kg m s-1 MPa-1) was estimated using the following equation by Noyer et al. [63]: Kring = KS × BAI2019, where the basal area increment of 2019 (BAI2019; cm2) was calculated using the equation BAI2019 = π (R22019 − R22018), where R is the radius of the tree in two subsequent years, 2018 and 2019 [64]. Subsequently, the xylem vulnerability index [65] was calculated by dividing the vessel diameter (D) by VD to obtain a rough estimation of the xeromorphic or mesomorphic character of the stem xylem.

According to the Hagen–Poiseuille law, large earlywood vessels in ring-porous oak species play a dominant role in axial water flow, wherein a few large earlywood vessels can transport an equal amount of sap as that transported by many small latewood vessels [37, 62]. However, the rationale of using all the vessels in the study was that the sampled wood sections had a semi-ring-porous to diffuse-porous structure instead of the ring-porous wood structure. In addition, the role of smaller vessels in ring-porous species is reportedly underestimated [66], considering their importance in tree survival when large vessels lose their transport capacity owing to drought-induced [67] or freeze-/thaw-induced embolism [68].

2.5. Statistical analyses

To assess the impact of CO2 concentration and fertilisation on sessile oak saplings, a split-plot experimental design was applied. After examining the normality assumption and variance homogeneity of the data, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the effects of CO2, nutrient supply, and their interactions on each measured biometrical and wood anatomical parameter. Additionally, Duncan’s method was used for the post-hoc comparisons of the treatment pairs. Non-normal data were transformed using a square root transformation and normality was then confirmed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test before performing the ANOVA.

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 13.0 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA), and statistical significance for all analyses was set at p ≤ 0.05. Boxplots were created using the software SigmaPlot® 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Generalised additive models (GAMs) were fitted to each individual tree image using the mgcv package of R software [69], and average values were then calculated per treatment to evaluate the vessel-area size changes within the tree rings.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of eCO2 and nutrient supply on biometrical characteristics

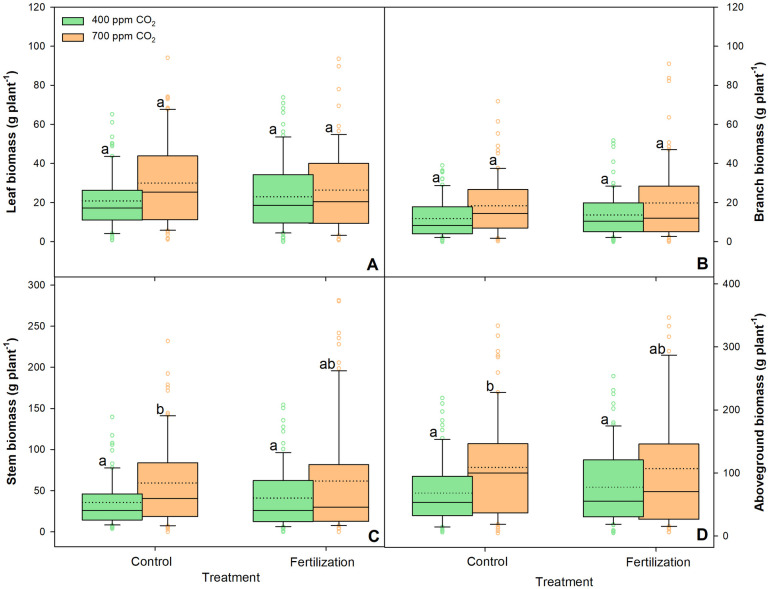

All aboveground morphological parameters measured were significantly affected by eCO2 treatment, whereas nutrient supply did not significantly affect them, except for SLA (p = 0.021) (Table 1). Furthermore, there was no significant effect of CO2 concentration–nutrient supply interactions on the aboveground biomass (Table 1). We observed a significant increase in all the biometrical parameters (H, D0.05m, and CSA0.05m) and all the aboveground biomass (i.e. leaves, branches, and stems) fractions (Fig 2, Table 1) under eCO2 treatment. Moreover, LA of the saplings was increased by 27%, and SLA was decreased by approximately 5.4% under eCO2 than under aCO2 (Table 1).

Table 1. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the influence of CO2, nutrient supply and their interactions on sessile oak saplings aboveground and belowground biometrical characteristics.

| CO2 | Nutrition | CO2 × Nutrition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | P | F | p | |

| Height (cm) | 4.15 | 0.043 ↑ | 0.438 | 0.509 | 0.001 | 0.975 |

| D0.05m (mm) | 10.99 | <0.001 ↑ | 0.28 | 0.596 | 1.54 | 0.215 |

| CSA0.05m (mm) | 13.92 | <0.001 ↑ | 0.16 | 0.686 | 1.22 | 0.270 |

| Leaf biomass (g) | 6.22 | 0.014 ↑ | 0.16 | 0.691 | 0.03 | 0.862 |

| Branch biomass (g) | 4.67 | 0.033 ↑ | 0.03 | 0.857 | 0.02 | 0.893 |

| Stem biomass (g) | 7.77 | 0.006 ↑ | 0.77 | 0.381 | 0.18 | 0.673 |

| Total aboveground biomass (g) | 7.36 | 0.007 ↑ | 0.45 | 0.501 | 0.06 | 0.809 |

| Fine root (≤2 mm) biomass (g) | 25.03 | <0.001 ↑ | 0.13 | 0.716 | 0.02 | 0.884 |

| Coarse root (>2mm) biomass (g) | 12.91 | <0.001 ↑ | 1.67 | 0.198 | 0.77 | 0.382 |

| Total belowground biomass (g) | 14.65 | <0.001 ↑ | 1.49 | 0.223 | 3.19 | 0.435 |

| Total plant biomass (g) | 11.58 | <0.001 ↑ | 0.07 | 0.985 | 0.53 | 0.467 |

| WD (g/cm3) | 8.70 | 0.003 ↓ | 2.70 | 0.102 | 0.00 | 0.961 |

| LA (m2/plant) | 6.65 | 0.011 ↑ | 0.02 | 0.889 | 0.85 | 0.356 |

| SLA (cm2 g-1) | 14.37 | <0.001 ↓ | 5.43 | 0.021 ↓ | 0.75 | 0.390 |

D0.05m—diameter at 5 cm above ground; CSA0.05m—cross-sectional area at 5 cm above ground; WD—wood density; LA—leaf area; SLA—Specific leaf area;

↑—increase with eCO2;

↓—decrease with eCO2.

Statistically significant effects and interactions are indicated in bold (p ≤ 0.05).

Fig 2. Changes in leaf biomass (A), branch biomass (B), stem biomass (C), and above-ground biomass (D) of sessile oak saplings (n = 72) treated under ambient (400 ppm CO2) and elevated (700 ppm CO2) and different nutrient supplies.

The data are expressed as medians (solid lines) and means (dotted lines) of measurements. The box boundaries mark the 25th and 75th percentiles and whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles. Circles marks outliners. Different letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) estimated on the basis of Duncan’s ANOVA post-hoc test.

Additionally, eCO2 had a positive effect on total sapling biomass, with an increase of 49% (Table 1). In turn, nutrient supply had a non-significant positive effect (an increase of 12%) on total sapling biomass under aCO2 treatment, whereas a non-significant negative effect (a decrease of 3%) was observed under eCO2 treatment (Figs 2 and 3, S1 Table).

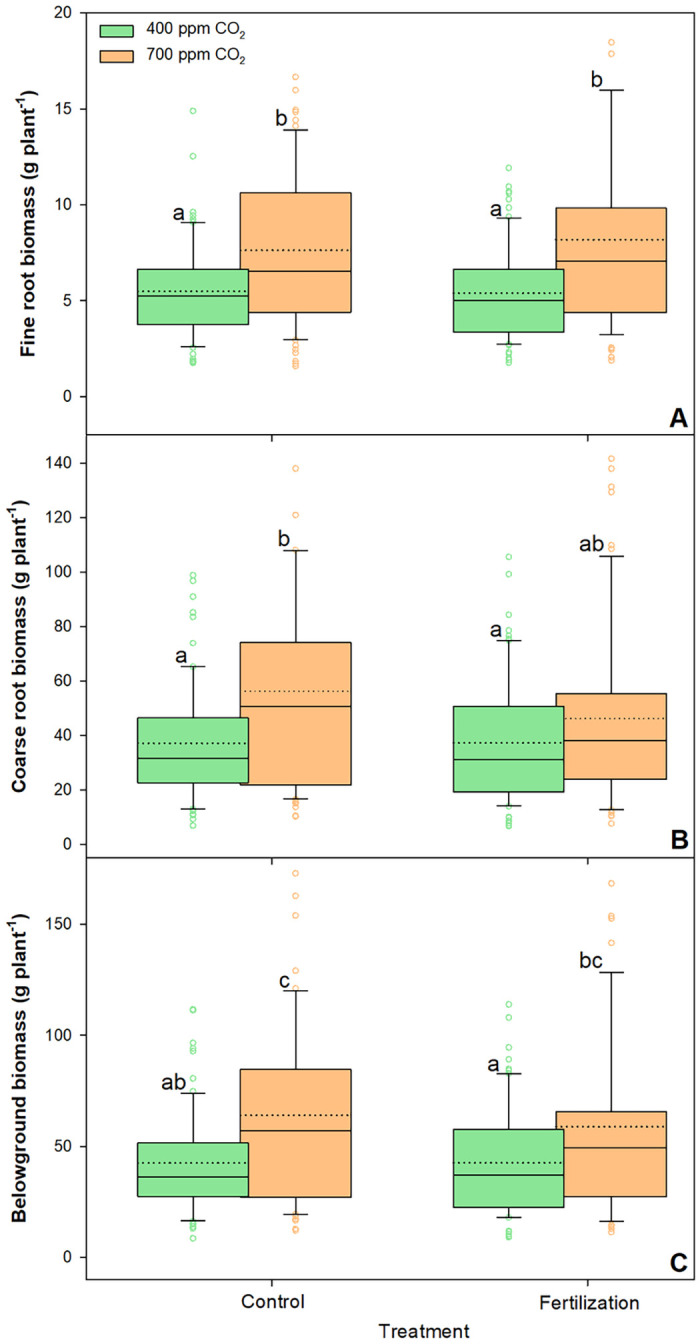

Fig 3. Changes in fine roots biomass (A), coarse roots biomass (B), and belowground biomass (C) of sessile oak saplings (n = 72) treated under ambient (400 ppm CO2) and elevated (700 ppm CO2) and different nutrient supplies.

The data are expressed as medians (solid lines) and means (dotted lines) of measurements. The box boundaries mark the 25th and 75th percentiles and whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles. Circles mark outliners. Different letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) estimated on the basis of Duncan’s ANOVA post-hoc test.

Furthermore, eCO2 treatment had a positive effect on total belowground biomass, i.e. an increase of 47% in fine and coarse roots (Table 1). However, nutrient supply had a negative effect on both fine and coarse roots (Fig 3). The saplings growing under eCO2 treatment had significantly higher amounts of fine roots (45%) than those growing under aCO2 treatment.

3.2. Effects of eCO2 and nutrient supply on wood structure

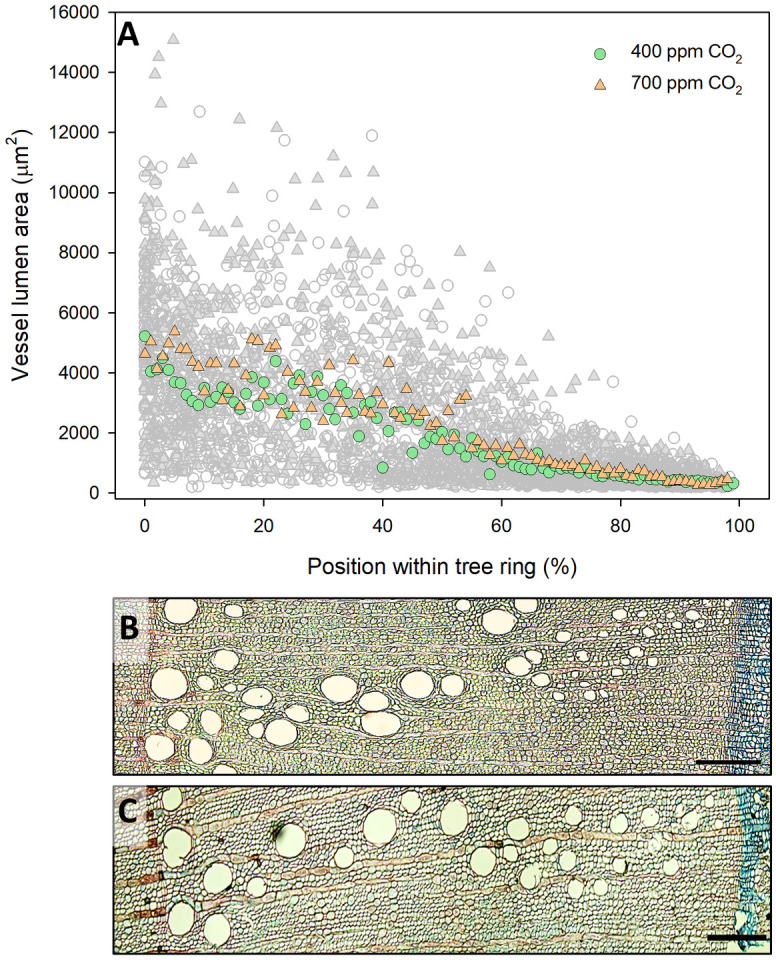

All wood anatomical parameters showed significant differences under eCO2 treatment, except for TVA, PTVA, and Ks, whereas neither nutrient supply nor the interaction between CO2 concentration and nutrient supply showed any influence on wood structure, except for BAI (Table 2). Larger vessels were observed in the earlywood and transition zones under eCO2 treatment (tree-ring position <50%), while latewood zone vessels tended to display similar lumen area regardless of the CO2 treatments (Fig 4).

Table 2. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the influence of CO2, nutrient supply, and their interactions on sessile oak saplings anatomical characteristics.

| CO2 | Nutrition | CO2 × Nutrition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Vessel diameter (μm) | 8.06 | 0.006 ↑ | 0.34 | 0.560 | 0.42 | 0.519 |

| VLA (μm2) | 9.32 | 0.003 ↑ | 0.69 | 0.410 | 0.74 | 0.394 |

| TVA (μm2) | 0.56 | 0.455 | 0.34 | 0.560 | 1.49 | 0.226 |

| PTVA (%) | 0.56 | 0.459 | 0.58 | 0.450 | 0.25 | 0.621 |

| Dhp (μm) | 8.69 | 0.004 ↑ | 0.49 | 0.484 | 2.19 | 0.143 |

| RW (μm) | 8.31 | 0.005 ↑ | 0.50 | 0.483 | 0.02 | 0.891 |

| BAI (mm2) | 11.61 | 0.001 ↑ | 0.53 | 0.471 | 4.20 | 0.044 |

| VD (No mm-2) | 5.43 | 0.023 ↓ | 0.59 | 0.443 | 0.62 | 0.434 |

| Ks (kg m-1 s-1 MPa-1) | 0.46 | 0.499 | 0.13 | 0.722 | 0.40 | 0.531 |

| Kring (kg m s-1 MPa-1) | 7.88 | 0.007 ↑ | 0.55 | 0.461 | 2.44 | 0.123 |

| Vulnerability index | 14.57 | 0.001 ↑ | 1.73 | 0.192 | 1.27 | 0.263 |

VLA—Vessel lumen area; TVA—total lumen vessel area; PTVA—the proportion of the total vessel lumen area per analyzed sector; Dhp -hydraulic weighted diameter; RW—ring width; BAI—Basal area increment; VD—Vesel density; Ks—potential specific hydraulic conductivity; Kring—potential hydraulic conductivity for a growth ring; Vulnerability index was calculated after Carlquist [65].

↑—increase with eCO2;

↓—decrease with eCO2.

Statistically significant effects and interactions are indicated in bold (p ≤ 0.05).

Fig 4. Overview of tree ring in 2019.

(A) The relative position of vessel lumen areas within tree ring created in 2019 with applied GAMs denoted by orange (elevated CO2) and green characters (ambient CO2). Microscope images of a cross-section of the 2019 annual ring of a sessile oak saplings growing in (B) ambient CO2 glass dome and (C) elevated CO2 glass dome. Scale bars = 200 μm.

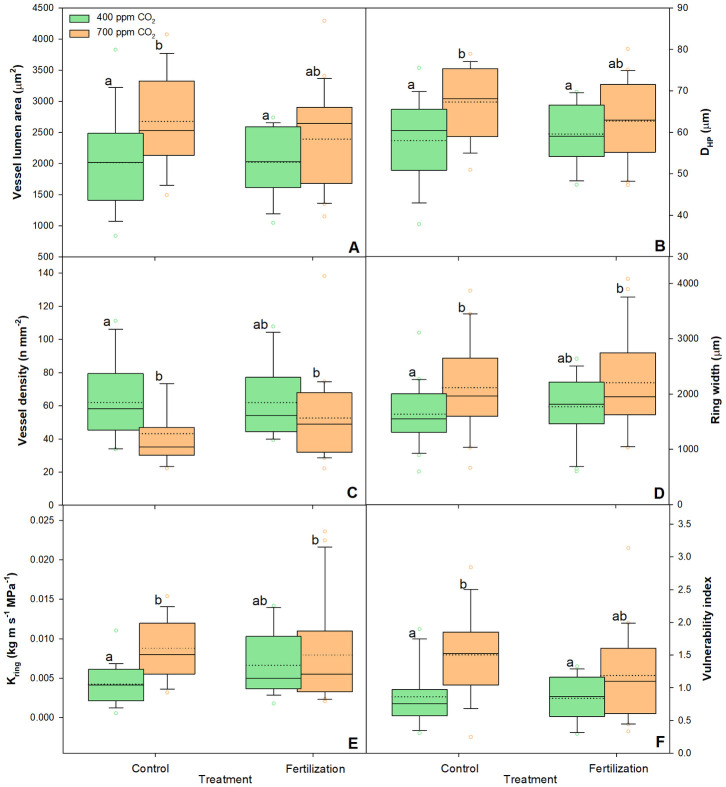

The VLA was significantly increased at eCO2, whereas VD was significantly lower (Fig 5, Table 2), with the highest VLA and lowest VD recorded in the saplings under eCO2 treatment without nutrient supply (Fig 5, S2 Table). In contrast, TVA and PTVA showed no significant differences under eCO2 as compared with aCO2 (Table 2, S2 Table), and RW exhibited the largest increase under the nutrient supply plus eCO2 combination treatment (Fig 5, S2 Table).

Fig 5. Changes in vessel lumen area (A), DHP (B), vessel density (C), Ring width (D), Kring (E), and Vulnerability index (F) of sessile oak saplings (n = 18) treated under ambient (400 ppm CO2) and elevated (700 ppm CO2) and different nutrient supplies.

The data are expressed as medians (solid lines) and means (dotted lines) of measurements. The box boundaries mark the 25th and 75th percentiles and whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles. Circles mark outliners. Different letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) estimated on the base of Duncan’s ANOVA post-hoc test.

The values of all the traits associated with hydraulic conductivity increased under eCO2 (Table 2), and the highest statistically significant values of Dhp were observed in saplings under eCO2 without nutrient supply (Fig 5, S2 Table). The Ks values were not significantly different between any of the treatments (S2 Table), whereas Kring values were significantly higher in saplings grown at eCO2 than in the saplings grown at aCO2, regardless of nutrient supply (Fig 5, S2 Table). Furthermore, the vulnerability index was significantly higher in the former case (Table 2), with the highest value observed in unfertilised saplings (Fig 5, S2 Table).

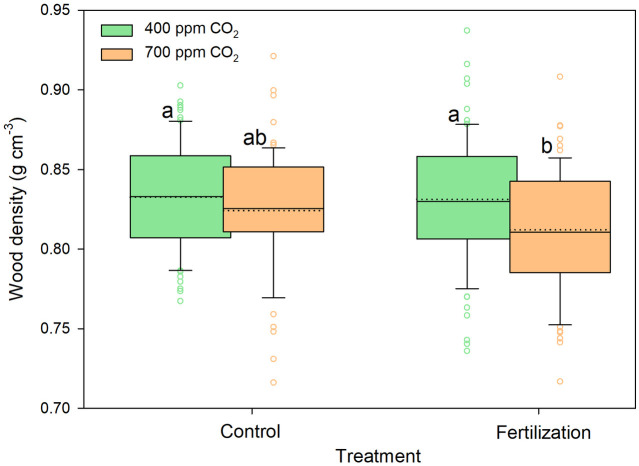

Overall, the saplings grown under eCO2 concentration treatment had significantly lower densities (approximately 1.7%); however, nutrient supply or the CO2-concentration—nutrient -supply interaction had no effect (Table 1). Saplings with nutrient supplementation had lower wood densities than the saplings grown without nutrient supply under the two different CO2 concentrations tested here; furthermore, the saplings grown with nutrient supply under eCO2 exhibited significantly lower wood densities than those in any other treatment (Fig 6, S1 Table).

Fig 6. Changes in over-dry wood density of sessile oak saplings (n = 72) treated under ambient (400 ppm CO2) and elevated (700 ppm CO2) and different nutrient supplies.

The data are expressed as medians (solid lines) and means (dotted lines) of measurements. The box boundaries mark the 25th and 75th percentiles and whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles. Circles mark outliners. Different letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) estimated on the base of Duncan’s ANOVA post-hoc test.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of eCO2 on biometrical characteristics of sessile oak saplings

Our study revealed a high growth benefit for sessile oak saplings grown in the eCO2 environment. After three years of exposure to eCO2 concentration treatment, the saplings grew taller and wider stems and accumulated 49% more dry biomass (both above- and belowground) than the saplings grown under aCO2 concentration treatment (Figs 2 and 3, Table 1). Previous studies have shown growth stimulation in young saplings of many different tree species in response to eCO2 [10, 70]. In sessile oak saplings grown under eCO2, Ofori-Amanfo et al. [15] revealed an increase in the light-saturated CO2 assimilation rate, a decrease in stomatal conductance, and consequently improved WUE. Evidently, eCO2 concentrations directly influence plant growth by increasing photosynthesis and decreasing stomatal conductance, resulting in a subsequent increase in WUE and carbohydrate availability for growth, eventually leading to greater biomass production [12]. Consistent with our results, Saxe et al. [71] reported that eCO2 significantly increased plant size and aboveground biomass, with angiosperms responding less (average increase of 49%) than conifers, which showed an average biomass increase of 130% (Figs 2 and 3, Table 1 and S1 Table).

Increased plant productivity is directly related to greater LA, which is crucial for radiation interception, photosynthetic assimilation, and, ultimately, plant growth and performance. Previous studies have reported larger LA and leaf biomass and reduced SLA in plants growing under eCO2 [11]. This study also showed that LA increased by 27% and SLA decreased by 5.4% in saplings grown under eCO2 treatment (Table 1 and S1 Table). Evidence suggest that eCO2 affects plant cell proliferation by enhancing cell division and cell enlargement [30], although, according to Pritchard et al. [11], increased leaf growth under eCO2 conditions is the result of cell proliferation stimulated by cell enlargement rather than cell division. Cell enlargement under eCO2 levels is achieved by the decreasing osmotic potential in the cell driven by excess carbohydrates in the sap, which in turn promotes further water intake by the cell, thereby increasing turgor-driven cell wall enlargement [72]. Nevertheless, under eCO2 conditions, the properties of the cell wall might be altered, and the cells may stretch to a greater extent than cells developing under lower CO2 concentrations [73].

However, the tree response to eCO2 is rather complex and we need to take into account complex interactions among CO2 concentrations, photosynthesis and other environmental factors, as well as even more complex relationships among carbon assimilation, plant respiration and growth [9, 10, 16]. For example, mature trees do not show greater biomass production under eCO2 despite the stimulated photosynthesis [19] suggesting that C availability itself is not necessarily the most limiting factor for tree growth [74, 75]. Instead, it was suggested that growth is limited by environment, and in particular water stress limits the ability of cambium to convert the carbon into growth [76]. In fact, many studies on different plant species have shown that during heat and water stress, C demand for growth always declines before photosynthesis (carbon supply) is affected [74, 75]. However the surplus in carbon is usually allocated in different sink other than growth (biomass), such as respiration [9, 19]. Thus, climate changes are widely expected to increase more extreme weather events, in particular heat and drought stress [44, 45], which will certainly mitigate the potential of eCO2 to stimulate tree growth in many regions [9].

4.2. Effects of eCO2 on wood structure of sessile oak saplings

Yazaki et al. [31] reported that both enhanced cell division and cell enlargement were responsible for increased wood formation under eCO2 conditions. In this study, sessile oak saplings grown under eCO2 treatment exhibited significantly increased RW, BAI, VLA, and, consequently, xylem hydraulic conductance (Figs 4 and 5, Table 2 and S2 Table). Wood formation is affected by cambial activity, which in turn may be affected by eCO2 concentrations. Consistently, Watanabe et al. [36] reported a high number of active cambium cells in two ring-porous species under eCO2 conditions, implying that the rate of cell division might be affected under varying CO2 concentrations [5]. Moreover, the systematic review by Yazaki et al. [26] reported that the diameter and number of angiosperm xylem conduits increased owing to the changes in the inner water balance induced by eCO2. This was confirmed in the ring-porous Q. robur saplings, where both size and density of the vessels increased under eCO2, resulting in a two-fold increase in TVA [35]. The results of our study are partly in agreement with the findings of the above study, because we observed an increased VLA and a significantly decreased VD in the saplings grown under eCO2, whereas TVA remained unchanged (Fig 5, Table 2).

Although information on the effects of eCO2 conditions on WD is limited and the results of previous studies are inconsistent [5, 26, 29, 30], eCO2 conditions reputedly affect the duration or extent of secondary cell wall deposition in addition to cell division and enlargement [5, 26, 77]. Domec et al. [30] reported that photosynthesis stimulation under eCO2 yielded sufficient building material for both thicker cell walls and sustained cell wall enlargement, which simultaneously increased WD and xylem conductivity. However, these findings are partly in agreement with those of Yazaki et al. [31], who suggested a major effect of eCO2 concentrations on cell division and enlargement rather than on cell wall deposition, resulting in a low WD in L. sibirica saplings growing under eCO2 treatment. The findings of Yazaki et al. [31] are consistent with our study results, which revealed a significantly low WD in saplings growing under eCO2 (Fig 6, Table 1).

The tree ring structure, defined by the number and dimensions of the constituent cells, is the primary determinant of WD. Angiosperm wood is a complex tissue that comprises vessels to conduct water, fibres to provide mechanical support, and parenchyma cells to store nutrients; furthermore, their relative proportions in the wood influences WD [39]. Vessels of ring-porous tree species have wider lumens than those in other wood cells. Moreover, vessel lumens have zero density and consequently negatively affect WD [78, 79]. However, we could not verify this observation in this study, as no statistical differences in TVA or PTVA were observed between saplings grown under the aCO2 and eCO2 treatments (Table 2 and S2 Table). Therefore, other anatomical characteristics, such as fibres, living parenchyma [39], and cell wall thickness of each cell type [77] may be responsible for the low WD in the saplings grown in an eCO2 environment. As this study was limited to wood anatomy of the conductive tissue in the last formed ring, we cannot draw any definite conclusions regarding this issue.

Moreover, studies by Bergès et al. [53] and Pretzsch et al. [41] reported long-term increased growth and reduced WD in sessile oak trees using dendrochronological and long-term inventory data, respectively, which are in agreement with our observations. Additionally, Pretzsch et al. [41] suggested that N supply via atmospheric deposition might be a major reason for a decrease in WD, rather than the increase in CO2 concentration, which contradicts our results (Table 1). Nevertheless, although we observed the highest WD decrease in the saplings grown with nutrient supplementation under the eCO2 treatment (Fig 6), we unexpectedly did not find significant effects of the interaction between CO2 concentration and nutrient supply (Table 1).

4.3. Response of sessile oak saplings to nutrient supply

Neither nutrient supply nor its interaction with CO2 concentration exhibited any significant effect on the experimental saplings, except for SLA (Tables 1 and 2). Similar results were reported by Lotfiomran et al. [34], who found that the anatomical features in F. sylvatica saplings were more strongly affected by eCO2 than by fertilisation. Similarly, although eCO2 enhanced the growth of Quercus alba saplings on N-limited soils, tissue N concentrations were significantly reduced compared to those in saplings grown under aCO2 treatment [80]. This implies that plants under eCO2 concentration were highly efficient, with less investment in their tissue [81], which was indirectly verified in our study via the reduced WD measured in the saplings grown under eCO2 treatment (Table 1).

The increase in sapling growth observed in our study required sufficient nutrients to take advantage of the eCO2 condition; that increased nutrient demand was met by the relatively fertile native soil where the saplings were planted. It has been demonstrated that eCO2 conditions accelerate the effects of nutrient unavailability with time [21–23]. For instance, Rolo et al. [82] reported that the enhanced growth in F. sylvatica and Picea abies Karst. saplings induced by eCO2 rendered the soil nutrient-deficient after six years. Therefore, we hypothesise that nutrient limitation in the glass dome supplied with eCO2 treatment will develop gradually and eventually hinder the CO2-induced increase in plant biomass productivity [21].

4.4. Possible implications on future forest management

Higher biomass production in sessile oak saplings under eCO2 treatment was supported by an efficient xylem hydraulic system (Tables 1 and 2). However, the trade-off between hydraulic efficiency and safety (the ability of xylem to resist the formation and spread of embolisms) suggest that xylem comprising larger vessels may be less resistant to embolism during severe drought [83]. Similar to our findings, Levanic et al. [84] observed higher Dhp, BAI, and consequently Kring in dead Q. robur trees than in the trees that survived a drought period, suggesting that the trees which died had been hydraulically maladjusted for dry conditions. This was also verified by the higher vulnerability index [65] observed in the saplings grown under eCO2 in our study (Fig 5, Table 2). According to the principles of Carlquist’s vulnerability index, saplings with wider and less abundant vessels express higher vulnerability indices and a higher mesic character, which are reflected in xylem conduits that are less resistant to embolism. However, enhanced WUE and larger absorptive area of the root system under eCO2, indicated by the increased biomass of both fine and coarse roots (Fig 3, Table 1), might compensate for xylem susceptibility and increase drought-resistance in sessile oak saplings [15]. Nevertheless, root capacity for water-uptake depends not only on root mass but also rooting depth as well as the area and activity of fine roots [11].

In this study, we found a significant effect of eCO2 treatment on WD (Fig 6, Table 1), which is reportedly associated with many wood characteristics [39]. Low WD is well associated with reduced wood stiffness and strength [85], as has been observed in conifer and angiosperm saplings growing under eCO2 conditions [29, 77], and higher susceptibility to wind and snow [43]. However, tree performances in response to mechanical constraints, such as wind or snow, are driven mainly by tree allometry, where the increase in stem diameter improves the fourth power resistance of stem to bending [86, 87] and proportionally to another mechanical stability trait [88]. Our results suggested that the mechanical performances are relayed by the improved growth rate under eCO2 and that the decrease in WD reflects the adjustments of the hydraulic system and management of construction cost to the increasing stem volume. Nevertheless, storm-mediated forest damage has increased in recent decades [89]. As suggested by Pretzsch et al. [41], although changes in forest management are primarily responsible for these observations, low mechanical stability—as indicated by lower WD values—might also contribute to forest damage.

Our study focused on juvenile wood, and it is uncertain how mature trees will respond to future atmospheric conditions, though correlations between the qualities of juvenile and mature wood have been reported [90]. However, Pretzsch et al. [41] reported that unlike older trees with denser and more stable wood, young saplings growing under conditions leading to lower WD and less mechanical stability will be more affected by high winds [43]. Moreover, a recent study on tree ring-growth in many species and environments found that faster tree ring-growth directly reduces tree lifespan [91].

Therefore, despite the increased biomass production at eCO2 in this economically and ecologically important European tree species, the impacts of lower density on mechanical strength, and xylem becoming more vulnerable to drought, may lead to earlier mortality offsetting the positive effect of future eCO2.

Supporting information

The data represent mean (± standard error of the mean). Different letters indicate significant differences (p≤0.05) estimated on the basis of Duncan’s ANOVA post-hoc test. D0.05m—diameter at 5 cm above ground; CSA0.05m—cross-sectional area at 5 cm above ground; LA—leaf area; SLA—Specific leaf area.

(DOCX)

The data represent mean (± standard error of the mean). Different letters indicate significant differences (p≤0.05) estimated on the basis of Duncan’s ANOVA post-hoc test. TVA—Total vessel lumen area; PTVA—the proportion of the total vessel lumen area per analyzed sector; Dhp—hydraulic diameter; VD—vessel density; TRW2019—Tree ring width; BAI2019—Basal area increment; Ks—Potential specific hydraulic conductivity; Kring—potential hydraulic conductivity for a growth ring; VI—Vulnerability index calculated after Carlquist [65].

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to Martin Benz and Jiří Šlížek for their invaluable help during sampling campaigns. Further, the authors acknowledge SILVATECH from UMR 1434 SILVA, 1136 IAM, 1138 BEF, and 4370 EA LERMAB EEF research centre INRA Nancy-Lorraine for the development of ImageJ macro.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The work was supported by the Internal Grant Agency of Mendel University in Brno with grant number 030/2020, IGRÁČEK MENDELU project CZ.02.2.69/0.0/0.0/19_073/0016670, reg. numb. SGC-2021-013 and Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of CR within the CzeCOS program, grant number LM2018123. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dlugokencky E, Tans P. Trends in atmospheric carbondioxide, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, Earth SystemResearch Laboratory (NOAA/ESRL). 2020 [cited 20 Apr 2021]. http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/global.html

- 2.van Vuuren DP, Edmonds J, Kainuma M, Riahi K, Thomson A, Hibbard K, et al. The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Clim Change. 2011;109: 5–31. doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0148-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciais P, Sabine C, Bala G, Bopp L, Brovkin V, Canadell J, et al. Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles. In: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, editor. Climate Change 2013—The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. pp. 465–570. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Y, Birdsey RA, Fang J, Houghton R, Kauppi PE, Kurz WA, et al. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science (80-). 2011;333: 988–993. doi: 10.1126/science.1201609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hättenschwiler S, Schweingruber FH, Körner C. Tree ring responses to elevated CO2 and increased N deposition in Picea abies. Plant, Cell Environ. 1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1996.tb00015.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Churkina G, Brovkin V, Von Bloh W, Trusilova K, Jung M, Dentener F. Synergy of rising nitrogen depositions and atmospheric CO2 on land carbon uptake moderately offsets global warming. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2009;23: 1–12. doi: 10.1029/2008GB003291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norby RJ, Wullschleger SD, Gunderson CA, Johnson DW, Ceulemans R. Tree responses to rising CO 2 in field experiments: implications for the future forest. Plant, Cell Environ. 1999;22: 683–714. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00391.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker AP, De Kauwe MG, Bastos A, Belmecheri S, Georgiou K, Keeling R, et al. Integrating the evidence for a terrestrial carbon sink caused by increasing atmospheric CO 2. New Phytol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/nph.16866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dusenge ME, Duarte AG, Way DA. Plant carbon metabolism and climate change: elevated CO2 and temperature impacts on photosynthesis, photorespiration and respiration. New Phytol. 2019;221: 32–49. doi: 10.1111/nph.15283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauriks F, Salomón RL, Steppe K. Temporal variability in tree responses to elevated atmospheric CO2. Plant Cell Environ. 2020; 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pritchard SG, Rogers HH, Prior SA, Peterson CM. Elevated CO2 and plant structure: A review. Glob Chang Biol. 1999;5: 807–837. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1999.00268.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceulemans R, Mousseau M. Tansley Review No. 71 Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2on woody plants. New Phytol. 1994;127: 425–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb03961.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lotfiomran N, Köhl M, Fromm J. Interaction effect between elevated CO2 and fertilization on biomass, gas exchange and C/N ratio of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). Plants. 2016;5: 1010–1016. doi: 10.3390/plants5030038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchytilová T, Krejza J, Veselá B, Holub P, Urban O, Horáček P, et al. Ultraviolet radiation modulates C:N stoichiometry and biomass allocation in Fagus sylvatica saplings cultivated under elevated CO2 concentration. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;134: 103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ofori-Amanfo KK, Klem K, Veselá B, Holub P, Agyei T, Marek M V., et al. Interactive Effect of Elevated CO2 and Reduced Summer Precipitation on Photosynthesis is Species-Specific: The Case Study with Soil-Planted Norway Spruce and Sessile Oak in a Mountainous Forest Plot. Forests. 2020;12: 42. doi: 10.3390/f12010042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eamus D, Jarvis PG. The Direct Effects of Increase in the Global Atmospheric CO2 Concentration on Natural and Commercial Temperate Trees and Forests. Advances in Ecological Research. 2004. pp. 1–58. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2504(03)34001-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Körner C. Plant CO2 responses: An issue of definition, time and resource supply. New Phytol. 2006;172: 393–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01886.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milanović S, Milenković I, Dobrosavljević J, Popović M, Solla A, Tomšovský M, et al. Growth rates of lymantria dispar larvae and quercus robur seedlings at elevated CO2 concentration and phytophthora plurivora infection. Forests. 2020;11: 1–14. doi: 10.3390/f11101059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang M, Medlyn BE, Drake JE, Duursma RA, Anderson IC, Barton CVM, et al. The fate of carbon in a mature forest under carbon dioxide enrichment. Nature. 2020;580: 227–231. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2128-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reich PB, Hungate BA, Luo Y. Carbon-nitrogen interactions in terrestrial ecosystems in response to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2006;37: 611–636. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dieleman WIJ, Luyssaert S, Rey A, De Angelis P, Barton CVM, Broadmeadow MSJ, et al. Soil [N] modulates soil C cycling in CO2-fumigated tree stands: A meta-analysis. Plant, Cell Environ. 2010;33: 2001–2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norby RJ, Warren JM, Iversen CM, Medlyn BE, McMurtrie RE. CO2enhancement of forest productivity constrained by limited nitrogen availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006463107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo Y, Su B, Currie WS, Dukes JS, Finzi A, Hartwig U, et al. Progressive Nitrogen Limitation of Ecosystem Responses to Rising Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Bioscience. 2004;54: 731. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terrer C, Jackson RB, Prentice IC, Keenan TF, Kaiser C, Vicca S, et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus constrain the CO2 fertilization of global plant biomass. Nat Clim Chang. 2019;9: 684–689. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0545-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirschbaum MUF, Lambie SM. Re-analysis of plant CO2 responses during the exponential growth phase: Interactions with light, temperature, nutrients and water availability. Funct Plant Biol. 2015;42: 989–1000. doi: 10.1071/FP15103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yazaki K, Maruyama Y, Mori S, Koike T, Funada R. Effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentration on wood structure and formation in trees. Plant Responses to Air Pollution and Global Change. Tokyo: Springer Japan; 2005. pp. 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wullschleger SD, Tschaplinski TJ, Norby RJ. Plant water relations at elevated CO2—Implications for water-limited environments. Plant, Cell Environ. 2002;25: 319–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe Y, Tobita H, Kitao M, Maruyama Y, Choi DS, Sasa K, et al. Effects of elevated CO2 and nitrogen on wood structure related to water transport in seedlings of two deciduous broad-leaved tree species. Trees—Struct Funct. 2008;22: 403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00468-007-0201-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ceulemans R, Jach ME, Van De Velde R, Lin JX, Stevens M. Elevated atmospheric CO2 alters wood production, wood quality and wood strength of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L) after three years of enrichment. Glob Chang Biol. 2002;8: 153–162. doi: 10.1046/j.1354-1013.2001.00461.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domec JC, Smith DD, McCulloh KA. A synthesis of the effects of atmospheric carbon dioxide enrichment on plant hydraulics: implications for whole-plant water use efficiency and resistance to drought. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40: 921–937. doi: 10.1111/pce.12843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yazaki K, Funada R, Mori S, Maruyama Y, Abaimov AP, Kayama M, et al. Growth and annual ring structure of Larix sibirica grown at different carbon dioxide concentrations and nutrient supply rates. Tree Physiol. 2001;21: 1223–1229. doi: 10.1093/treephys/21.16.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaakinen S, Kostiainen K, Ek F, Saranpää P, Kubiske ME, Sober J, et al. Stem wood properties of Populus tremuloides, Betula papyrifera and Acer saccharum saplings after 3 years of treatments to elevated carbon dioxide and ozone. Glob Chang Biol. 2004;10: 1513–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00814.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kostiainen K, Jalkanen H, Kaakinen S, Saranpää P, Vapaavuori E. Wood properties of two silver birch clones exposed to elevated CO2and O3. Glob Chang Biol. 2006;12: 1230–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01165.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lotfiomran N, Fromm J, Luinstra GA. Effects of elevated CO2 and different nutrient supplies on wood structure of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) and gray poplar (Populus × canescens). IAWA J. 2015;36: 84–97. doi: 10.1163/22941932-00000087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atkinson CJ, Taylor JM. Effects of elevated CO2 on stem growth, vessel area and hydraulic conductivity of oak and cherry seedlings. New Phytol. 1996;133: 617–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1996.tb01930.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe Y, Satomura T, Sasa K, Funada R, Koike T. Differential anatomical responses to elevated CO2 in saplings of four hardwood species. Plant, Cell Environ. 2010;33: 1101–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02132.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tyree ME, Zimmermann MH. Xylem Structure and the Ascent of Sap (Second Edition). Springer Verlag. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chave J, Coomes D, Jansen S, Lewis SL, Swenson NG, Zanne AE. Towards a worldwide wood economics spectrum. Ecol Lett. 2009;12: 351–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziemińska K, Butler DW, Gleason SM, Wright IJ, Westoby M. Fibre wall and lumen fractions drive wood density variation across 24 Australian angiosperms. AoB Plants. 2013;5: 1–14. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plt046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enquist BJ, West GB, Charnov EL, Brown JH. Allometric scaling of production and life-history variation in vascular plants. Nature. 1999;401: 907–911. doi: 10.1038/44819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pretzsch H, Biber P, Schütze G, Kemmerer J, Uhl E. Wood density reduced while wood volume growth accelerated in Central European forests since 1870. For Ecol Manage. 2018;429: 589–616. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.07.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pietras J, Stojanović M, Knott R, Pokorný R. Oak sprouts grow better than seedlings under drought stress. iForest—Biogeosciences For. 2016;009: e1–e7. doi: 10.3832/ifor1823-009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDowell NG, Allen CD, Anderson-Teixeira K, Aukema BH, Bond-Lamberty B, Chini L, et al. Pervasive shifts in forest dynamics in a changing world. Science (80-). 2020;368: eaaz9463. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz9463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen CD, Macalady AK, Chenchouni H, Bachelet D, McDowell N, Vennetier M, et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For Ecol Manage. 2010;259: 660–684. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krejza J, Cienciala E, Světlík J, Bellan M, Noyer E, Horáček P, et al. Evidence of climate-induced stress of Norway spruce along elevation gradient preceding the current dieback in Central Europe. Trees. 2021;35: 103–119. doi: 10.1007/s00468-020-02022-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanewinkel M, Cullmann DA, Schelhaas MJ, Nabuurs GJ, Zimmermann NE. Climate change may cause severe loss in the economic value of European forest land. Nat Clim Chang. 2013;3: 203–207. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kohler M, Pyttel P, Kuehne C, Modrow T, Bauhus J. On the knowns and unknowns of natural regeneration of silviculturally managed sessile oak (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) forests—a literature review. Ann For Sci. 2020;77: 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s13595-020-00998-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mölder A, Meyer P, Nagel RV. Integrative management to sustain biodiversity and ecological continuity in Central European temperate oak (Quercus robur, Q. petraea) forests: An overview. For Ecol Manage. 2019;437: 324–339. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2019.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cochard H, Bréda N, Granier A. Whole tree hydraulic conductance and water loss regulation in Quercus during drought: evidence for stomatal control of embolism? Ann des Sci For. 1996;53: 197–206. doi: 10.1051/forest:19960203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stojanović M, Szatniewska J, Kyselová I, Pokorný R, Čater M. Transpiration and water potential of young Quercus petraea (M.) Liebl. coppice sprouts and seedlings during favourable and drought conditions. J For Sci. 2017;63: 313–323. doi: 10.17221/36/2017-JFS [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nölte A, Yousefpour R, Hanewinkel M. Changes in sessile oak (Quercus petraea) productivity under climate change by improved leaf phenology in the 3-PG model. Ecol Modell. 2020;438: 109285. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2020.109285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kunz J, Löffler G, Bauhus J. Minor European broadleaved tree species are more drought-tolerant than Fagus sylvatica but not more tolerant than Quercus petraea. For Ecol Manage. 2018;414: 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergès L, Nepveu G, Franc A. Effects of ecological factors on radial growth and wood density components of sessile oak (Quercus petraea Liebl.) in Northern France. For Ecol Manage. 2008;255: 567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2007.09.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lauriks F, Salomón RL, De Roo L, Steppe K. Leaf and tree responses of young European aspen trees to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration vary over the season. Tree Physiol. 2021; 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cha S, Chae HM, Lee SH, Shim JK. Effect of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration on growth and leaf litter decomposition of Quercus acutissima and Fraxinus rhynchophylla. PLoS One. 2017;12: 14–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Urban O, Janouš D, Pokorný R, Markova I, Pavelka M, Fojtík Z, et al. Glass domes with adjustable windows: A novel technique for exposing juvenile forest stands to elevated CO2 concentration. Photosynthetica. 2001. pp. 395–401. doi: 10.1023/A:1015134427592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williamson GB, Wiemann MC. Measuring wood specific gravity…correctly. Am J Bot. 2010;97: 519–524. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rossi S, Anfodillo T, Menardi R. Trephor: A New Tool for Sampling Microcores from tree stems. IAWA J. 2006;27: 89–97. doi: 10.1163/22941932-90000139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fajstavr M, Giagli K, Vavrčík H, Gryc V, Horáček P, Urban J. The cambial response of Scots pine trees to girdling and water stress. IAWA J. 2020;41: 159–185. doi: 10.1163/22941932-bja10004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9: 671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fonti P, Heller O, Cherubini P, Rigling A, Arend M. Wood anatomical responses of oak saplings exposed to air warming and soil drought. Plant Biol. 2013;15: 210–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tyree MT, Ewers FW. The hydraulic architecture of trees and other woody plants. New Phytol. 1991;119: 345–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1991.tb00035.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noyer E, Lachenbruch B, Dlouhá J, Collet C, Ruelle J, Ningre F, et al. Xylem traits in European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) display a large plasticity in response to canopy release. Ann For Sci. 2017;74: 46. doi: 10.1007/s13595-017-0634-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stojanović M, Sánchez-Salguero R, Levanič T, Szatniewska J, Pokorný R, Linares JC. Forecasting tree growth in coppiced and high forests in the Czech Republic. The legacy of management drives the coming Quercus petraea climate responses. For Ecol Manage. 2017;405: 56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2017.09.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carlquist S. Ecological factors in wood evolution: a floristic approach. Am J Bot. 1977;64: 887–896. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1977.tb11932.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Copini P, Vergeldt FJ, Fonti P, Sass-Klaassen U, den Ouden J, Sterck F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging suggests functional role of previous year vessels and fibres in ring-porous sap flow resumption. Steppe K, editor. Tree Physiol. 2019;39: 1009–1018. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpz019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taneda H, Sperry JS. A case-study of water transport in co-occurring ring- versus diffuse-porous trees: Contrasts in water-status, conducting capacity, cavitation and vessel refilling. Tree Physiol. 2008;28: 1641–1651. doi: 10.1093/treephys/28.11.1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sevanto S, Michele Holbrook N, Ball MC. Freeze/thaw-induced embolism: Probability of critical bubble formation depends on speed of ice formation. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wood SN. Generalized additive models: An introduction with R, second edition. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, Second Edition. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kirschbaum MUF. Direct and indirect climate change effects on photosynthesis and transpiration. Plant Biol. 2004;6: 242–253. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-820883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saxe H, Ellsworth DS, Heath J. Tree and forest functioning in an enriched CO2 atmosphere. New Phytol. 1998;139: 395–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00221.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Steppe K, Sterck F, Deslauriers A. Diel growth dynamics in tree stems: Linking anatomy and ecophysiology. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20: 335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pantin F, Simonneau T, Muller B. Coming of leaf age: Control of growth by hydraulics and metabolics during leaf ontogeny. New Phytol. 2012;196: 349–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04273.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Körner C. Carbon limitation in trees. J Ecol. 2003;91: 4–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00742.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muller B, Pantin F, Génard M, Turc O, Freixes S, Piques M, et al. Water deficits uncouple growth from photosynthesis, increase C content, and modify the relationships between C and growth in sink organs. J Exp Bot. 2011;62: 1715–1729. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peters RL, Steppe K, Cuny HE, De Pauw DJW, Frank DC, Schaub M, et al. Turgor—a limiting factor for radial growth in mature conifers along an elevational gradient. New Phytol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/nph.16872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bin Luo Z, Langenfeld-Heyser R, Calfapietra C, Polle A. Influence of free air CO2 enrichment (EUROFACE) and nitrogen fertilisation on the anatomy of juvenile wood of three poplar species after coppicing. Trees—Struct Funct. 2005;19: 109–118. doi: 10.1007/s00468-004-0369-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rao R V., Aebischer DP, Denne MP. Latewood density in relation to wood fibre diameter, wall thickness, and fibre and vessel percentages in Quercus robur L. IAWA J. 1997;18: 127–138. doi: 10.1163/22941932-90001474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leal S, Sousa VB, Knapic S, Louzada JL, Pereira H. Vessel size and number are contributors to define wood density in cork oak. Eur J For Res. 2011;130: 1023–1029. doi: 10.1007/s10342-011-0487-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Norby RJ, O’Neill EG, Luxmoore RJ. Effects of Atmospheric CO 2 Enrichment on the Growth and Mineral Nutrition of Quercus alba Seedlings in Nutrient-Poor Soil. Plant Physiol. 1986;82: 83–89. doi: 10.1104/pp.82.1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stitt M, Krapp A. The interaction between elevated carbon dioxide and nitrogen nutrition: the physiological and molecular background. 1999; 583–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00386.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rolo V, Andivia E, Pokorný R. Response of Fagus sylvatica and Picea abies to the interactive effect of neighbor identity and enhanced CO2 levels. Trees—Struct Funct. 2015;29: 1459–1469. doi: 10.1007/s00468-015-1225-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hacke UG, Sperry JS, Pittermann J. Efficiency Versus Safety Tradeoffs for Water Conduction in Angiosperm Vessels Versus Gymnosperm Tracheids. Vascular Transport in Plants. Elsevier; 2005. pp. 333–353. doi: 10.1016/B978-012088457-5/50018-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Levanic T, Cater M, McDowell NG. Associations between growth, wood anatomy, carbon isotope discrimination and mortality in a Quercus robur forest. Tree Physiol. 2011;31: 298–308. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Niklas KJ, Spatz H. Worldwide correlations of mechanical properties and green wood density. Am J Bot. 2010;97: 1587–1594. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Larjavaara M, Muller-Landau HC. Rethinking the value of high wood density. Funct Ecol. 2010;24: 701–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Badel E, Ewers FW, Cochard H, Telewski FW. Acclimation of mechanical and hydraulic functions in trees: impact of the thigmomorphogenetic process. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fournier M, Dlouhá J, Jaouen G, Almeras T. Integrative biomechanics for tree ecology: beyond wood density and strength. J Exp Bot. 2013;64: 4793–4815. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schelhaas MJ, Nabuurs GJ, Schuck A. Natural disturbances in the European forests in the 19th and 20th centuries. Glob Chang Biol. 2003;9: 1620–1633. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00684.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zobel BJ, Sprague JR. Predictions of Mature and Total Tree Wood Properties from Juvenile Wood. Juvenile Wood in Forest Trees. 1998. pp. 173–187. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72126-7_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brienen RJW, Caldwell L, Duchesne L, Voelker S, Barichivich J, Baliva M, et al. Forest carbon sink neutralized by pervasive growth-lifespan trade-offs. Nat Commun. 2020;11: 4241. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17966-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The data represent mean (± standard error of the mean). Different letters indicate significant differences (p≤0.05) estimated on the basis of Duncan’s ANOVA post-hoc test. D0.05m—diameter at 5 cm above ground; CSA0.05m—cross-sectional area at 5 cm above ground; LA—leaf area; SLA—Specific leaf area.

(DOCX)

The data represent mean (± standard error of the mean). Different letters indicate significant differences (p≤0.05) estimated on the basis of Duncan’s ANOVA post-hoc test. TVA—Total vessel lumen area; PTVA—the proportion of the total vessel lumen area per analyzed sector; Dhp—hydraulic diameter; VD—vessel density; TRW2019—Tree ring width; BAI2019—Basal area increment; Ks—Potential specific hydraulic conductivity; Kring—potential hydraulic conductivity for a growth ring; VI—Vulnerability index calculated after Carlquist [65].

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.