Abstract

Mexico is the center of origin and diversification of domesticated chile (Capsicum annuum L.). Chile is conceived and employed as both food and medicine in Mexico. In this context, the objective of this paper is to describe and analyze the cultural role of chile as food and as medicine for the body and soul in different cultures of Mexico. To write it, we relied on our own fieldwork and literature review. Our findings include a) the first matrix of uses of chile across 67 indigenous and Afrodescendants cultures within Mexican territory and b) the proposal of a new model of diversified uses of chile. Traditional knowledge, uses and management of chile as food and medicine form a continuum (i.e., are not separated into distinct categories). The intermingled uses of Capsicum are diversified, deeply rooted and far-reaching into the past. Most of the knowledge, uses and practices are shared throughout Mexico. On the other hand, there is knowledge and practices that only occur in local or regional cultural contexts. In order to fulfill food, medicinal or spiritual functions, native communities use wild/cultivated chile.

Keywords: Capsicum, food-medicine continuum, indigenous communities, Afrodescendants, body healer

1. Introduction

Chile (common Spanish name derived from the Nahuatl language to be used here) is native to the Americas; however, it now flavors cuisines around the globe [1,2,3]. Mexico is considered the center of origin and diversity of domesticated Capsicum annuum L. chile with a continuous use of wild and domesticated varieties of at least 6000 years [4,5,6]. Thus, chile along with maize (Zea mays), beans (Phaseolus spp.) and squash (Cucurbita spp.) have co-evolved with local groups even before the establishment of civilizations was recognized [7]. Currently, in Mexico there are about 60–70 indigenous groups that have safeguarded traditional/local environmental knowledge (TEK) related to the management, production and diversified use of natural resources including chile [8,9]. Two works framed in Mexico have described various uses of chile but were not exhaustive. Long-Solís [10] described various cultural aspects of chile at different times in the winding and intricate history of this region of the world. Data from Aguilar’s doctoral dissertation [9] also describe other linguistic, historical, and archaeological data on the versatility and complexity of cultural patterns of chile production and use.

Due to the economic and food importance of chile around the world, hundreds of studies have been conducted on the nutraceutical importance of the spicy fruits when consumed directly in fresh bites or as part of a dish prepared with fresh or dried chile (without industrial additives) in daily or festive food preparations throughout the world [11,12,13]. The use of chile as a food emerged in the Americas and with the exchange of plants and global cultural processes that occurred 500 years ago, this plant spread to virtually all continents [1,14]. Today, in many Asian, African, European, and American countries, chile is part of the daily diet and is even an essential ingredient in emblematic dishes such as the masalas in India, goulash in Turkey, curries in Thailand, etc. [15,16]. Nowadays, there is a whole food industry that uses technology to transform Capsicum fruits into flavoring, coloring and preservation of other foods that are produced on a large scale and distributed over long distances [17,18,19]. Therefore, chile are in great demand depending on the purpose for which they are used worldwide.

Chiles are utilized for many purposes. They pertain to many varieties, mainly of C. annuum [20]. However, few studies of this species have adopted an ethnobotanical approach in order to analyze ethnographic aspects in the center of origin and diversity. These indicate ancient/modern uses of chile in each of the indigenous cultures within a multiethnic territory where the fruit is a deeply rooted element of intensive daily use. For example, there are studies of the Nahua of the Huastec region, Tlapanecs of Guerrero, Mixtecs and Zapotecs of Oaxaca where chile is the protagonist, most of them documented by the authors of the present study [21,22,23]. There are other biocultural studies of the past that only mentioned chile as part of a list [24].

Currently, with a disciplinary vision within the hard sciences, modern uses of chile for medicinal purposes have also been validated in a scheme unrelated to traditional Mexican medicine [25]. These studies explored the effectiveness of functional properties often attributed to carotenoids, vitamin C and E, alkaloids, flavonoids, and capsaicin that support the maintenance of health and well-being [11]. However, by eliminating chile and analyzing them separately from their primary cultural context, the complex biocultural relationships that are part of the cultural construction of health-related ideas and practices are occult for the academic eye.

It stands out that the secondary metabolites of the spicy fruits have been managed, selected, and diversified for use as food and/or medicine without interruption by different cultures of Mexico [26]. Indigenous territories of Mexico have been culturally divided into Mesoamerica (central and southern Mexico) and Arid America (northern Mexico). In Mesoamerica there is a particular conceptualization of the natural world as a living being that holds intimate relationships of exchange and mutual dependence with the social, human world [10,11]. This interdependence is expressed in the multifaceted way in which people interact with and use biological resources. Within the same region, health is understood as being the combination of physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being while life is thought of as a combination of body, mind, and soul. The Nahuatl terms refer to major concentrations of soul forces and vital fluids distributed throughout the organism, but concentrated in the head, heart, and liver, respectively [12,13]. The soul or spirit of a person can be affected by various natural and supernatural agents, causing psychosocial and somatic imbalance. The ailing person then turns to traditional medicine to regain balance, health, and well-being. In practically all ancient cultures as well as their modern descendants, healthcare was a concern that remained mainly on the family level, based on basic knowledge linked to the use of medicinal herbs, roots, and minerals, which could be acquired without any problem at markets [27,28]. In addition, there are specialists that utilize herbalism, bone manipulation, various basic surgical techniques, divination and incantations in their practice [28,29]. Under this cosmology, traditional medicine can be preventive or corrective. Therefore, it seems relevant to highlight that chile has been used as a food–medicine continuum as mentioned by other resources elsewhere [30,31,32,33]. In this context, the objective of this paper is to describe and analyze the cultural role of chile as food and as medicine for the body and soul in the different cultures of Mexico.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

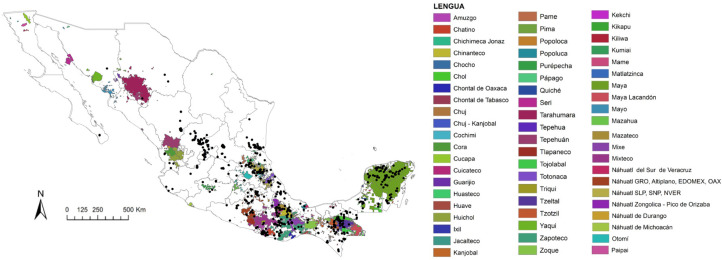

Mexico is the study area and it has a population with blurred ethnic boundaries [34] (see Figure 1), as other Latin American countries. In 2015, speakers of indigenous languages represent 6.5% of the total population in Mexican territory [35], but many people considered today as descend from indigenous people who lost their language [36,37]. They often share many cultural elements with the native communities of the same region, including agricultural and culinary traditions. The names of the native languages spoken were taken as a reference to delimit the modern cultures which descended from Mesoamerican intellectual traditions [38]. The list is based on the catalogue of indigenous languages of Mexico [39] that counts 67 linguistic groupings, used here as a unit of study, distributed in 364 linguistic variants (formerly linguistic groupings were considered as languages and their variants as dialects, but linguists have demonstrated that these last ones were actually languages). In addition, for the current analysis of the human-Capsicum relationship in Mexico, two groups of Afro-descendants were considered (one of Guerrero and Veracruz, and the Mascogo community of Coahuila).

Figure 1.

Distribution map of Capsicum annuum var. annuum in Mexico in relation to the indigenous cultures. The colored backgrounds indicate the territories of the 67 indigenous languages spoken in Mexico. (Map elaborated by A. Aguilar-Meléndez and Andrés Lira-Noriega from personal and CONABIO databases, and for the Amerindian territories, from maps provided by INALI and the anthropologist Eckart Boege).

2.2. Field Study

Araceli Aguilar has collected ethnobotanical data over 20 years, focusing on indigenous territories, following The Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology. Datapoints of botanical samples gathered from fieldwork, national herbarium specimens and other datasets such as the CONABIO were utilized to draw the map of Figure 1. The map was already published (with graphical variation) in previous studies [20]. The others authors recovered ethnobotanical and ethnographic information regarding the genus Capsicum while focusing on the ethnoecology of chile, nurse plants, fowl, and Mexican indigenous people, such as the Chontales of Tabasco, the Zapotecs of Guelavía, and the Mixe of Guichicovi, Oaxaca (MAVD); working on Zapotec home gardens, ethnobotany of traditional agroforestry systems and traditional markets in Oaxaca (GIMM), and on food and agriculture with Mixtec people in Oaxaca and food studies around the country (EK).

2.3. Bibliographic Research

The authors reviewed articles of natural sciences, articles, books, and thesis of social sciences and cookbooks of the CONACULTA (cultural branch of Mexican federal government) collection called Cocina indígena y popular (Indigenous and popular cuisine). The search for natural sciences articles (original or review) was performed using the PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus electronic databases until March 2021. The main keywords used were: “Capsicum medicine”; “traditional use of Capsicum”; “Mesoamerica and Capsicum”; among others. All the included references were manually selected, reviewed, and added to the database in Filemaker by the authors.

2.4. Analysis of Cookbooks

In total, 77 cookbooks from the series Cocina indígena y popular and other Spanish written documents were reviewed. A database was constructed to determine the possible variety by inferring it with the common name. Recipes and culinary processes were registered as well. Annotations about the languages were important to determine the cultural context of the cookbook.

2.5. Classification of Illnesses

Diseases or symptoms associated with potential modern diseases were classified according to the 2021 WHO system, the ICD-11 version 09-2020 (https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 1 March 2021)), into 12 categories: (1) infectious or parasitic diseases, (2) mental, behavioural, or neurodevelopmental disorders, (3) diseases of the nervous system; (4) diseases of the visual system; (5) diseases of the ear or mastoid process; (6) diseases of the respiratory system; (7) diseases of the digestive system, (8) diseases of the skin; (9) diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue, (10) diseases of the genitourinary system, (11) pregnancy, childbirth or puerperium and (12) poisoning. This classification is an interpretation/translation of the authors of this paper and is not based on an emic view of the local medicine of each culture. Medicine for the soul area: to describe cultural-bound syndromes that Western mental health professionals and scientists fail to validate as “real illnesses” [40].

3. Results

Chile functions as a multifocal symbol operating intimately on many levels of people’s lives. Plant use is an integral part of the mental and physical life of people who live in direct contact with their natural resources. This is a resilient factor among indigenous communities worldwide. Like another Latin American countries, Mexico has a mixed population with blurred ethnic boundaries [34]. Presently speakers of indigenous languages represent 6% of the population [41], but many people considered today as mestizos descend from indigenous people who lost their language [36,37]; they often share many cultural elements, including agricultural and culinary traditions, with the native communities of the same region. Chile are always part of all of them since it is a crop that has intertwined its history with the history of the cultures that domesticated it [38].

The analysis of 77 cookbooks edited by CONACULTA gave some clues as to which chile are depicted on modern written documents (Table 1). Only six cookbooks were bilingual; Nahuatl [42], Tarahumara [43], Mayo [44], Yaqui [44], Purepecha [45], Totonac [46], Tepehuan [47] and also included common names for chile on each languages. In total, 32 out of 77 have some common names for ingredients in local languages but not terms referring to chile were included. Culinary processes mentioned for cooking or using chile were: deveined, roasted, boiled, grilled, ground, molcajeteado (crushed in a stone such as mortar), chopped, sieved, crushed, seeded, cut into small pieces, washed, blended, stuffed, stuffed, fried, cooked, shredded, scrambled, burned, soaked, ground, parboiled, strained, soaked, browned in oil, ground in metate, sprinkled, filleted, finely chopped, stewed, seasoned, sautéed, mashed, chopped, sliced.

Table 1.

Use of chile as food, medicine for the body and the soul in Mexico.

| Family language | Language/Cultural Group | Food | Medicine for the Body | Medicine for the Soul |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oto-manguean | Otomi | [48] | [10] | |

| Mazahua | [49] | |||

| Matlatzinca | [49] | |||

| Tlahuica | [49] | |||

| Pame | [50] | |||

| Chichimeco jonaz | [51] | |||

| Chinantec | [52] | [10] | ||

| Tlapanec | [53] | [54] | ||

| Mazatec | [55] | |||

| Ixcatec | [56] | |||

| Chocholtec | [57] | [57] | ||

| Popoloca | [58] | |||

| Zapotec | [23,59,60] | [61] | [23] | |

| Chatino | [62] | |||

| Amuzgo | [53] | |||

| Mixtec | [22,53,63] | [22] | ||

| Cuicatec | [64] | |||

| Triqui | [65] | |||

| Maya | Tenek | [29] | [29] | [29] |

| Maya Yucatec | [66,67,68] | [69] | [69] | |

| Lacandon | [70] | |||

| Ch’ol | [71] | |||

| Chontal of Tabasco | [72] | |||

| Tseltal | [73] | |||

| Tsotsil | [73] | [74] | [74] | |

| Q’anjob’al | [75] | |||

| Akateko | [76] | |||

| Jakalteko | [77] | |||

| Qato’k | [78] | |||

| Chuj | [79] | |||

| Tojolabal | [73] | |||

| Q’eqchi’ | [80] | |||

| K’iche’ | [81] | |||

| Kaqchikel | [81] | |||

| Teko | [75] | |||

| Mam | [73] | |||

| Awakateko | [82] | |||

| Ixil | [83] | |||

| Totonaco-Tepehua | Totonac | [46] | [46] | [46] |

| Tepehua | [84] | |||

| Purepecha | Purepecha | [45] | [45] | |

| Mixe-zoque | Mixe | [85] | [86] | |

| Sayulteco | [87] | |||

| Oluteco | [88] | |||

| Texistepequeño | [89] | |||

| Ayapaneco | [90] | |||

| Popoluca | [60] | |||

| Zoque | [70] | |||

| Chontal de Oaxaca | Chontal of Oaxaca | [91] | ||

| Huave | Huave | [92] | [93] | |

| Algica | Kickapoo | [94] | ||

| Yuto-nahua del sur | Pápago | [95] | ||

| Pima | [96] | [96] | ||

| Northern Tepehuan | [47] | |||

| Southern Tepehuan | [47] | |||

| Tarahumara | [43] | [97] | ||

| Guarijio | [98] | |||

| Yaqui | [44,99] | |||

| Mayo | [44] | |||

| Cora | [100] | |||

| Huichol | [101] | |||

| Nahuatl | [53,60,102] | [21] | ||

| Yuto-nahua del sur | Paipai | [103] | ||

| Cucapá | [103] | |||

| Kumiai | [103] | |||

| Kiliwa | [103] | |||

| Seri | Seri | [104] | ||

| No language affiliation | Mascogos | [105] | ||

| No language affiliation | Afrodescendants | [106,107] |

Out of 3641 records, 561 chile with no specific name, 105 wild chile, and 2975 domesticated chile were used. Three main groups of chile were commonly used in recipes all over Mexico. The grouping was made by the fresh and dry state of the same variety (except for guajillo) (1) complex Poblano/Ancho/Color (550 records); (2) Guajillo (445 records) and (3) Jalapeño/Chipotle (337 records), common names for fresh chile of this group are: Jalapeño, Cuaresmeño, Gordo and Huauchinango, common names for dry chile are: Chipotle, Mora and Morita. Another classification was the rarely mentioned names (44 records with less than 3 records), 89 chile are C. chinense and C. pubescens versus 2535 corresponding mainly to domesticated varieties of C. annuum. The variability of the amount of spice consumed in Mexico’s culinary mosaic is impossible to describe by scientific standards. Some studies have made metabolomics studies that give some hints as to the biochemical variants expressed in the flavor, heat, and odor of chile [108] but tests have yet to be conducted on the complex culinary dishes of multi-ethnic Mexico.

3.1. Chile as Food

Chile is ubiquitous in all Mexican food. According to Elisabeth Rozin [109], it is its “flavoring principle”. However, it is much more than a flavor. For Mexican people, most foods cannot be eaten without chile. Not only would it be bland, but also it would not be a balanced meal. Most Mexicans conceive that hot and cold principles rule food and body health. According to cultures and regions, different qualities may be attributed to foodstuffs, but they are usually the same for the staples: corn is considered as warm, beans as cold and chile is hot. “Cold” food is not good for the body, a meal must tend toward “warm” food, without being too hot, except in case of a “cold” disease, when food must heat up the body [110].

For centuries, Mexican peasants have been basing their diet on boiled beans and corn tortillas, with chile. For city dwellers, corn and beans may not be the basis of their diet, if they consume more meat, for instance, but are at least the side dish. Corn and beans balance each other, beans cannot be eaten alone, and usually are cooked with chile, as “cold” food is supposed to be heavy to digest. Then raw chile or a chile sauce is served on the table, and each eater adds it to the plate according to the individual taste. Most dishes are cooked together with raw or dry chile (meat, vegetables, etc) or in elaborated chile sauces (mole, adobo, etc). Chile is added to industrial food, such as tortilla chips, to sweets, even when designed for children. Corn on the cob and sliced fruits (such as mango) eaten as snacks, and often sold on the street, are served with lemon and chile powder. Without chile, the body balance would be in danger. However, if the person is sick, chile is not recommended [102]. Many people we interviewed declared that they were strong or resistant thanks to chile. This was particularly true in rural areas, where people compared themselves to city dwellers, or to “gringos”, whom they judged weaker. Children get used to chile from their earliest age, in their mother’s womb, through their mother’s milk, from the smells of their family’s kitchen. Chile is progressively introduced in their food so that at an early age (some beginning at the age of four), children like to eat chile [111].

3.2. Chile as Medicine for the Body

Due to the effectiveness of using chile to heal, dozens of modern scientific studies have currently been carried out to recognize its therapeutic action [112,113,114,115] and that have indirectly validated the ancestral and traditional uses. Here we depicted a brief description:

-

(1)

Certain infectious or parasitic diseases: antibacterial and antimicrobial [96,116]; the Pimas of Sonora use it as antibacterial [96]; Nematicide [10,117]: the Pimas of Sonora use it as a nematicide [96]; Fever: in Santo Domingo Petapa and Santa María Petapa, the Zapotecs of the Isthmus to relieve fever [61]; the korí chókame (black chile) of the Raramuris is used to prepare a tea to relieve fever [97]; in Santo Domingo Petapa and Santa María Petapa, the Zapotecs of the Isthmus use chile to relieve fever [61].

-

(2)

Mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders: the Raramuris and Mestizos use isíburi (plant mixture with chile) to treat hangovers and fever [97].

-

(3)

Diseases of the nervous system. The BDMTM mentions that it is used as an antineuralgic [118]; the Raramuris use a mixture of chiltepín (C. annuum var. glabriusculum) with chupate (Ligusticum porter, Apiaceae) to treat headaches; a BDMTM mentions that it is used as an antineuralgic [118].

-

(4)

Diseases of the visual system [61,112,114]: the Mestizos of Querétaro State use it to relieve an eye infection by applying a crushed quipín chile (C. annuum var. glabriusculum) [119]; in Santo Domingo Petapa and Santa María Petapa, the Zapotecs of the Isthmus apply chile leaves for eye problems [61]; Tenek of San Luis Potosí use it to cure eye problems [29].

-

(5)

Diseases of the ear or mastoid process [61,112,114]: Sahagún quoted by López Austin [120] says that the Nahua cured ear ulcers with warm drops of coyoxóchitl with chile; the Raramuris use it to treat ear pain [97]; mestizos from Sonora use the oil of chiltepín (C. annuum var. glabriusculum) to cure ear pain [121].

-

(6)

Diseases of the respiratory system [46,69,113,120]: Nahua to treat cough in Tlanchinol, Hidalgo [122]; mestizos in the State of Querétaro cure certain pulmonary ailments and fevers by smoking dried chile to cause sweating and coughing [119]; Sahagún quoted by López Austin [120] says that the Nahua drank water from the root of the tlacopópotl, and lime water with chile and a decoction of iztáuhyatl to cure coughs and expel phlegm. Mestizos from Sonora eat a lot of chiltepín (C. annuum var. glabriusculum) to avoid the flu and smoke it with tobacco to remove the cough [121].

-

(7)

Diseases of the digestive system including teeth conditions [69,113,120,123]; mestizos in the State of Querétaro use it to prevent constipation and gastritis [119]; Sahagún quoted by López Austin [120] says that the Nahua cured constipation by administering through the anus a suppository made with soot and a little saltpeter, kneaded with rubber filled with chile, made into a ball and inserted from behind, and to tartar diarrhea they drank chía (Salvia hispanica) atole (maize based drink) mixed with chía totopos (grilled tortillas) and sprinkled with chile; Mestizos from Sonora use chiltepín to cure ulcers, gastritis, and hemorrhoids [121]; the BDMTM mentions that it is used as an antidiarrheal, carminative, eupeptic [118]; Lacandon Maya uses chile to soothe toothache and inflamed gums [124].

-

(8)

Diseases of the skin [113]: mestizos in the State of Querétaro apply an patch of ground piquín chile to areas of the skin affected with erysipelas or festering so that the wound does not become infected and that it helps with pain [119]; mestizos in Sonora use chiltepín (C. annuum var. glabriusculum) to heal wounds [121]; the BDMTM mentions that in Veracruz and Oaxaca it is used to treat chincual de criatura (cultural illness), erysipelas and wounds, as well as being used as an antiseptic [118]; Tenek of San Luis Potosí use it to cure skin problems [29]; the Zapotecs of San Juan Guelavía use it roasted and dried to remove pimples from the face [23]; in the Tzotzil of Zinacantán, Chiapas [74].

-

(9)

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue: the BDMTM mentions that it is used as antirheumatic [118]: the Raramuris use chiltepín in poultice to relieve arthritic pain in the hands [97]; to cure broken bones: Otomí bonesetters use to massage the rib cage while the patient blows into a bottle to reset broken ribs. Then they put a cataplasm of sacasil tuber ground with cumin (Cuminum cyminum), cayenne chile (Capsicum sp.), and cloves (Eugenia caryophyllus) over the lesion [125].

- (10)

-

(11)

Pregnancy, childbirth, or puerperium help to mitigate labor pain and promotes delivery [69].

-

(12)

Poisoning. Mestizos from Sonora use chiltepín (C. annuum var. glabriusculum) with tallow for tarantula bites [121].

3.3. Chile as Medicine for the Soul

The use of herbal medicines, and complementary and alternative medicine, is increasing globally. There is an emphasis on a holistic approach, consistent with definition of health of the World Health Organization (WHO). Health is understood as being the combination of physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being and life as being a union of body, mind, and soul. In this section, we will describe chile as medicine for the soul. The concept of the soul is not universal, nor is it found in all cultures. In Mexico, several native terms are translated as soul, such as tonalli among the Nahua [126] or pixan among the Maya [127]. According to the Nahua, the fetus receives both a soul and a heart during the gestation process. The soul is given by the Sun-God and is therefore considered “warm”; based in the heart, it endows the infant with life and the capacity for movement and growth [128]. The soul or spirit of a person can be affected by various natural and supernatural agents, causing psychosocial and somatic imbalance. The sick person then turns to traditional medicine to regain balance, health, and well-being. Many traditional cultures in Mexico use diverse species of plants (and a few animals) to cure people of the evil eye (mal de ojo in Spanish). Generally, it can be characterized as the personal emanation of a force that arises involuntarily due to a strong desire and that harms the desired being. The evil eye is a recognized cause of health care in Mexico, especially by rural inhabitants and traditional healers. This condition is considered a culture-bound syndrome in which there is a state of restlessness characterized by anxiety, depression, insomnia, and loss of appetite [129]. Children are the main population affected by the evil eye. Chile is used in various ways to prevent and cure the evil eye in several ethnic cultures of Mexico; for example, the Zoques of Chiapas [130], the Zapotecs of Oaxaca [23], five ethnic groups of Puebla [128], the Huastecs of Veracruz [131], the peasants of Querétaro [119], and the Guarijío and Mayo of Sonora [121]. Other ailments related to the soul and in which chile is used as medicine are: “dead people’s evil wind” (mal aire de muerto in Spanish), a bad entity that comes from people who just died, registered in Oaxaca with Mixes and Mixtecs [22,132]; evil supernaturals, fright, and witchcraft among Zapotecs of Oaxaca [23,133].

3.4. A Model of Human Management of Chile in Mexico

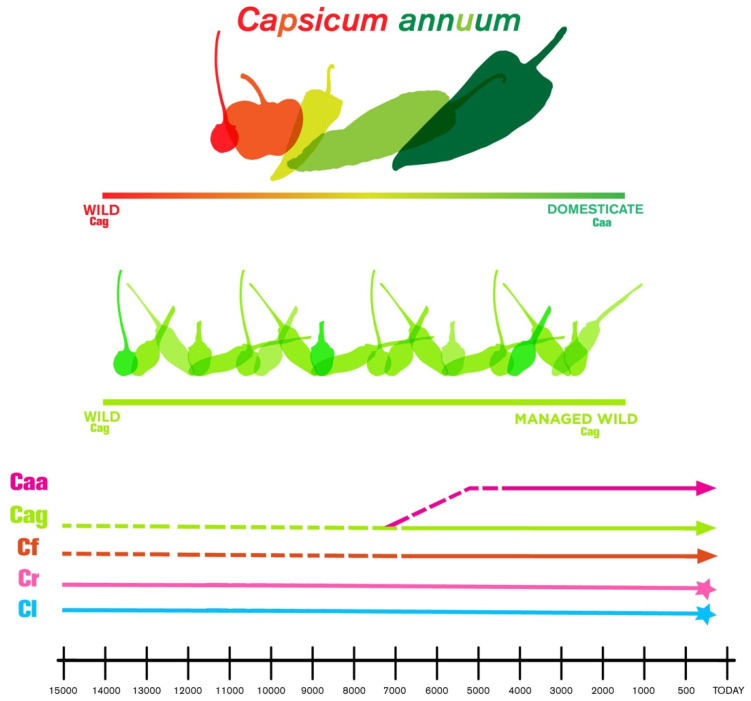

The model of human management of chile proposed here is shown as a continuum that goes from wild to domesticate with blur limits (Figure 2). As an addition to this model, the native species utilized are wild and domesticates of C. annuum and C. frutescens.

Figure 2.

Model of human management of chile in Mexico. C. lanceolatum (Cl) and C. rhomboideum (Cr) were never utilized by humans (blue and pink ending in a star); C. frutescens (Cf) that includes wild and domesticates; C. annuum var. glabriusculum (Cag) are the wild chile and putative ancestor of Caa, and C. annuum var. annuum (Caa) includes the modern domesticated landraces and commercial varieties.

There is a wide range of uses where the spicy fruit is consumed and putatively act as a protector element, medicine, and/or food. A more holistic way of presenting natural resources within the academic world is increasing in popularity [134] recognizing the need to present a more “real” picture of how natural resources are perceived and utilized.

4. Conclusions

This work shows that Mexico’s ethnic cultures conceive, use and manage chile as a food-medicine continuum and can possibly be explained because it is a fruit that, similar to corn, has a deep symbolic meaning in Mesoamerican and Arid American cultures.

The use of chile in food is common to the whole territory providing nutrients to the Mexicans who consume them [25]. The present study shows data confirming this fact. However, regional studies that connect the studies of secondary metabolites of local cultivars with the preferences of the uses of each culture are needed to achieve a better understanding of the patterns of human selection on a plastic crop of the Solanaceae family. This study also concluded that medicinal uses for the body and soul have very restricted use in current times when compared to the presence of chile as food.

We need to further test the local concepts of illness (imbalance) and health (equilibrium) using chile as a theoretical axis to approach descendants of the Mesoamerican intellectual traditions within the multiethnic territory. Chile has been used in different cultural spaces at different times to cure various diseases that were classified here in 12 categories. Scientific results validated many of the ancient uses of chile as medicine (see Table 1 and section chile as medicine for the body). Some questions to be pursued for future studies are (1) have medicinal uses been lost at different scales (community, language/culture, or nationwide)? (2) do we have knowledge of the ingredients, preparation processes, and utensils to prepare chile as a medicine for a particular ailment?

Although there are many studies that validate the efficacy of chile in curing diseases such as cancer [135]. Other healing properties have been attributed to chile, as documented in this study, particularly the properties to cure culturally affiliated diseases whose biochemical foundation is unclear or it might be healing in other forms. Eleven ethnic groups of Chiapas, Oaxaca, Puebla, Veracruz, Querétaro, and Sonora use chile to prevent and cure the evil eye. In Oaxaca, Mixes, Mixtecs, and Zapotecs use chile against evil beings, fright, and witchcraft. Therefore, we should initiate systematic studies in Mesoamerican cultural contexts to acknowledge more complex illnesses that have been made invisible for the global academic world.

There are shared uses, practices, and knowledge throughout the Mexican territory such as the spicy fruits being used as condiments and vegetables to prepare food. On the other hand, specific uses within the medicinal (body and soul) categories are found in local contexts unique to a particular indigenous culture that are not repeated in the rest of the country. It may be the reason why there is a high diversity of chile in the form of cultivars of C. annuum var. annuum that are the result of locally selected unique morphotypes.

Further research is needed to fill the gaps in local and indigenous knowledge by training local ethno-scientists [136] to carry out participatory research with a dual purpose: to generate academic knowledge and to restitute that knowledge to the communities where biodiversity is being conserved [137]. This is particularly relevant in one of the most megadiverse countries of the world, Mexico.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Edmundo Rodríguez Campos for technical support, Reyna Pelcastre Reyes for graphical design and Jumko Ogata Aguilar for English proofreading.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.-M., M.A.V.-D., and E.K.; Data curation, A.A.-M. and G.I.M.-M.; Investigation, A.A.-M.; Resources, G.I.M.-M.; Writing—original draft, A.A.-M., M.A.V.-D., and E.K.; Writing—review and editing, M.A.V.-D. and E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Instituto Politécnico Nacional, grant number SIP: 20211931, Proyect name: Ethnoecology of chile (Capsicum spp.) in indigenous localities of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Andrews J. Peppers the Domesticated Capsicums. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX, USA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nabhan G.P. Why Some Like It Hot: Food, Genes, and Cultural Diversity. Island Press; Washington, DC, USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripodi P., Rabanus-Wallace M.T., Barchi L., Kale S., Esposito S., Acquadro A., Schafleitner R., van Zonneveld M., Prohens J., Diez M.J., et al. Global range expansion history of pepper (Capsicum spp.) revealed by over 10,000 genebank accessions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2104315118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2104315118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry L., Flannery K.V. Precolumbian use of chili peppers in the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11905–11909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704936104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goettsch B., Urquiza-Haas T., Koleff P., Acevedo Gasman F., Aguilar-Meléndez A., Alavez V., Alejandre-Iturbide G., Aragón Cuevas F., Azurdia Pérez C., Carr J.A., et al. Extinction risk of Mesoamerican crop wild relatives. Plants People Planet. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ppp3.10225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguilar-Meléndez A., Morrell P.L., Roose M.L., Kim S.C. Genetic diversity and structure in semiwild and domesticated chiles (Capsicum annuum; Solanaceae) from Mexico. Am. J. Bot. 2009;96:1190–1202. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenswig R.M., Rosenswig R.M. The Beginnings of Mesoamerican Civilization: Inter-Regional Interaction and the Olmec. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallejo-Ramos M., Moreno-Calles A.I., Casas A. TEK and biodiversity management in agroforestry systems of different socio-ecological contexts of the Tehuacan Valley. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016;12:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0102-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aguilar-Meléndez A. Ethnobotanical and Molecular Data Reveal the Complexity of the Domestication of Chiles (Capsicum annuum L.) in Mexico. University of California; Riverside, CA, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long-Solís J. Capsicum y Cultura: La Historia del Chilli. 1st ed. Fondo de Cultura Económica; Mexico City, Mexico: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernández-Pérez T., Gómez-García M.d.R., Valverde M.E., Paredes-López O. Capsicum annuum (hot pepper): An ancient Latin-American crop with outstanding bioactive compounds and nutraceutical potential. A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020;19:2972–2993. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badia A.D., Spina A.A., Vassalotti G. Capsicum annuum L.: An overview of biological activities and potential nutraceutical properties in humans and animals. J. Nutr. Ecol. Food Res. 2017;4:167–177. doi: 10.1166/jnef.2017.1163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiang Q., Guo W., Tang X., Cui S., Zhang F., Liu X., Zhao J., Zhang H., Mao B., Chen W. Capsaicin—the spicy ingredient of chili peppers: A review of the gastrointestinal effects and mechanisms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;116:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.08.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz E. Chili Pepper, from Mexico to Europe: Food, imaginary and cultural identity. In: Medina F.X., Ávila R., de Garine I., editors. Food, Imaginaries and Cultural Frontiers. Essays in Honour of Helen Macbeth. Universidad de Guadalajara, Colección Estudios del Hombre, Serie Antropología de la Alimentación; Guadalajara, México: 2009. pp. 213–232. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dott B.R. The Chile Pepper in China: A Cultural Biography. Columbia University Press; New York, NY, USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz E. Flavors and Colors: Chili Pepper in Europe. In: Kaller M., Jacob F., editors. Transatlantic Trade and Global Cultural Transfers Since 1492: More than Commodities. Routledge; London, UK: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baenas N., Belović M., Ilic N., Moreno D., García-Viguera C. Industrial use of pepper (Capsicum annum L.) derived products: Technological benefits and biological advantages. Food Chem. 2019;274:872–885. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu M., Chen C., Lan Y., Xiao J., Li R., Huang J., Huang Q., Cao Y., Ho C.-T. Capsaicin—the major bioactive ingredient of chili peppers: Bio-efficacy and delivery systems. Food Funct. 2020;11:2848–2860. doi: 10.1039/D0FO00351D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Sá Mendes N., de Andrade Gonçalves É.C.B. The role of bioactive components found in peppers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;99:229–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguilar-Meléndez A., Lira-Noriega A. ¿Dónde crecen los chiles en México? In: Aguilar-Meléndez A., Vásquez-Dávila M.A., Katz E., Hernández C.M.R., editors. Los Chiles que le dan Sabor al Mundo. Contribuciones Multidisciplinarias. Universidad Veracruzana, y el Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo (IRD, Francia); Xalapa, Veracruz, México: 2018. pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Güemes Jiménez R., Aguilar-Meléndez A. Etnobotánica nahua del chile en la Huasteca meridional. In: Aguilar-Meléndez A., Vásquez-Dávila M.A., Katz E., Hernández C.M.R., editors. Los Chiles Que le Dan Sabor al Mundo. Contribuciones Multidisciplinarias. Universidad Veracruzana, y el Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo (IRD, Francia); Xalapa, Veracruz, México: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz E. El chile en la Mixteca alta de Oaxaca: De la comida al ritual. In: Aguilar-Meléndez A., Vásquez-Dávila M.A., Katz E., Hernández C.M.R., editors. Los Chiles Que le Dan Sabor al Mundo. Contribuciones Multidisciplinarias. Universidad Veracruzana, y el Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo (IRD, Francia); Xalapa, Veracruz, México: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz-Núñez N.d.C., Vásquez-Dávila M.A. Etnoecología del chile de campo en Guelavía, Oaxaca. In: Aguilar-Meléndez A., Vásquez-Dávila M.A., Katz E., Hernández-Colorado M.R., editors. Los Chiles Que le Dan Sabor al Mundo. Contribuciones Multidisciplinarias. Universidad Veracruzana, y el Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo (IRD, Francia); Xalapa, Veracruz, México: 2018. pp. 260–280. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clement C.R., Casas A., Parra-Rondinel F.A., Levis C., Peroni N., Hanazaki N., Cortés-Zárraga L., Rangel-Landa S., Alves R.P., Ferreira M.J. Disentangling domestication from food production systems in the neotropics. Quaternary. 2021;4:4. doi: 10.3390/quat4010004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganguly S., Praveen K.P., Para P.A., Sharma V. Medicinal properties of chilli pepper in human diet. ARC J. Public Health Community Med. 2017;2:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luna-Ruiz J.d.J., Nabhan G.P., Aguilar-Meléndez A. Shifts in Plant Chemical Defenses of Chile Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Due to Domestication in Mesoamerica. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018;6:48. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gómez-Dantés O., Frenk J. La atención a la salud en Mesoamérica antes y después de 1519. Salud Pública de México. 2020;62:114–117. doi: 10.21149/10996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López Austin A. Cuerpo Humano e Ideologia las Concepciones de los Antiguos Nahuas. 3rd ed. UNAM; Mexico City, Mexico: 1989. p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alcorn J.B. Huastec Mayan Ethnobotany. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX, USA: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pieroni A., Price L. Eating and Healing: Traditional Food as Medicine. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y., Liang D., Wang G.-T., Wen J., Wang R.-J. Nutritional and functional properties of wild food-medicine plants from the coastal region of South China. J. Evid.-Based Integr. Med. 2020;25:2515690X20913267. doi: 10.1177/2515690X20913267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattalia G., Sõukand R., Corvo P., Pieroni A. Blended divergences: Local food and medicinal plant uses among Arbëreshë, Occitans, and autochthonous Calabrians living in Calabria, Southern Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2020;154:615–626. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2019.1651786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Etkin N.L. Edible Medicines: An Ethnopharmacology of Food. University of Arizona Press; Tucson, AZ, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitt-Rivers J. La culture métisse: Dynamique du statut ethnique. L’homme. 1992;32:133–148. doi: 10.3406/hom.1992.369529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Government F. INEGI. [(accessed on 5 October 2021)]. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/

- 36.Navarrete-Linares F. Las Relaciones Interétnicas en México. UNAM; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Del Popolo F., Oyarce A.M. Población indígena de América Latina: Perfil sociodemográfico en el marco de la CIPD y de las Metas del Milenio. Notas de Población. 2005;79:35–62. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Good E.C. Las cosmovisiones, la historia y la tradición intelectual en Mesoamérica. In: Gámez Espinosa A., López Austin A., editors. Cosmovisión Mesoamericana. Reflexiones, Polémicas y Etnografías. FCE, Colmex, FHA, BUAP; Mexico City, Mexico: 2015. pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- 39.INALI Catálogo de las Lenguas Indígenas Nacionales: Variantes lingüísticas de México con sus Autodenominaciones y Referencias Geoestadísticas. 2008. [(accessed on 15 May 2021)]. Available online: http://www.inali.gob.mx/pdf/CLIN_completo.pdf.

- 40.Yamada A.-M., Marsella A.J. Handbook of Multicultural Mental Health. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2013. The study of culture and psychopathology: Fundamental concepts and historic forces; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.INEGI . Estadísticas a Propósito del Día Internacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (9 de Agosto) INEGI; Mexico City, Mexico: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramírez Mar M. Recetario nahua del norte de Veracruz. Volume 1 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mares Trias A. Comida de los Tarahumaras. Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yocupicio Buitimea R. Recetario Indígena de Sonora. Volume 9 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martínez Márquez J.S., Méndez Agustín M.R., Tomás Martínez E. Recetario de Atápakuas Purépechas. Volume 37 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aguilera Madero R. Recetario Totonaco de la Costa de Veracruz. Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivas Vega J., Solís Arellano Y., Flores Domene A. Recetario Tepehuano de Chihuahua y Durango. Volume 53 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Latapí López H. Voces y Sabores de la Cocina Otomí de Querétaro. Volume 59 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cano Garduño L., Gómez Sánchez D. Cinco Sabores Tradicionales Mexiquenses. Cocina Mazahua, Otomí, Nahua, Matlatzinca y Tlahuica. Consejo Estatal para el Desarrollo Integral de los Pueblos Indígenas del Estado de México y Universidad Intercultural del Estado de México; Mexico City, Mexico: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chemin Bäsler H. Recetario pame de San Luis Potosí y Querétaro. Volume 26 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Escobar Ledesma A. Recetario del Semidesierto de Querétaro. Volume 08 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hernández López J., Merlín Arango R. Recetario Chinanteco de Oaxaca. Volume 20 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.González Villalobos S. Recetario Indígena de Guerrero. Volume 36 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dehouve D. El uso ritual del chiltepín entre los tlapanecos (me’ phaa) del estado de Guerrero. In: Aguilar-Meléndez A., Vásquez-Dávila M.A., Katz E., Hernández-C M.R., editors. Los Chiles Que le Dan Sabor al Mundo. Contribuciones Multidisciplinarias. Universidad Veracruzana, Instituto de investigación para el Desarrollo (IRD, Francia); Xalapa, Veracruz, México: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Merlín Arango R., Hernández López J. Recetario Mazateco de Oaxaca. Volume 42 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rangel-Landa S., Casas A., Rivera-Lozoya E., Torres-García I., Vallejo-Ramos M. Ixcatec ethnoecology: Plant management and biocultural heritage in Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016;12:s13002–s13016. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0101-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caltzontzin Andrade T. Recetario Chocholteco de Oaxaca. Volume 30 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Santos Tanús A., Aldasoro Maya E.M., Rojas Serrano C., Morales H. Especies alimenticias de recolección y cultura culinaria: Patrimonio biocultural de la comunidad popoloca Todos Santos Almolonga, Puebla, México. Nova Sci. 2019;11:296-342. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henestrosa Río C. Recetario Zapoteco de Istmo. Volume 33 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arias Rodríguez E. Recetario Indígena del sur de Veracruz. Volume 11 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frei B., Baltisberger M., Sticher O., Heinrich M. Medical ethnobotany of the Zapotecs of the Isthmus-Sierra (Oaxaca, Mexico): Documentation and assessment of indigenous uses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998;62:149–165. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(98)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palacios A.B.S. “Me echaba a buscar al monte”. La recolección de alimentos en Santa Catarina Juquila, Oaxaca (1963–2013. In: Licona Valencia E., García López I.C., Cortés Patiño A., editors. Alimentación, Cultura y Territorio. Acercamientos Etnográficos. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla; Puebla, México: 2017. pp. 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vázquez Peralta R. Recetario Mixteco Poblano. Volume 2 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arellanes Y., Casas A., Arellanes A., Vega E., Blancas J., Vallejo M., Torres I., Rangel-Landa S., Moreno A.I., Solís L., et al. Influence of traditional markets on plant management in the Tehuacán Valley. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:38. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zapata E.P.B.E. Dioses, Huipiles y Conejos: Tres Canciones Infantiles en el triqui de Chicahuaxtla. Latin Am. Lit. Rev. 2020;47 doi: 10.26824/lalr.138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferrer García J.C. Recetario Maya de Quintana Roo. Volume 3 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maldonado Castro R. Recetario Maya del Estado de Yucatán. Volume 17 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 68.May Dzib S. Recetario Maya de Campeche. Volume 72 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roys R.L. The Ethno-Botany of the Maya. Tulane University; New Orleans, LA, USA: 1931. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mayorga Mayorga F., de la Cruz S. Recetario Zoque de Chiapas. Volume 47 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sapper K. Choles y chortíes. LiminaR. Estud. Soc. Hum. 2004;2:119–142. doi: 10.29043/liminar.v2i1.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Javier Quero J.C. Bebidas y Dulces Tradicionales de Tabasco. Volume 23 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mayorga Mayorga F., Sánchez Balderas A.F. Recetario Indígena de Chiapas. Volume 39 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Breedlove D.E., Laughlin R.M. The Flowering of Man: A Tzotzil Botany of Zinacantan. Smithsonian Institution Press; Washington, DC, USA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala: Guatemala . Jit’il Q’anej yet Q’anjob’al. Vocabulario Q’anjob’al. Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala; Guatemala City, Guatemala: 2003. p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ouellet S. Plantas Alimenticias Nativas de San Rafael Independencia. Estudio Etnobotánico y Nutricional de Plantas Nativas Comestibles para Seguridad Alimentaria en San Rafael La Independencia, Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Cooperativa Rafaeleña, Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala, Universidad de Sherbrooke.; Guatemala City, Guatemala: 2016. p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Montejo V.D. Diccionario de la Lengua Maya Popb’al Ti. FAMSI; Point Loma, CA, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petrich P. Qato’k (o mochó): La Alimentación Mochó: Acto y Palabra (Estudio Etnolingüístico) Centro de Estudios Indígenas, Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas; San Cristobal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buenrostro C. Chuj de San Mateo Ixtatán. El Colegio de México; Mexico City, Mexico: 2009. p. 250. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Estrada Ochoa A.C. Li Tzuultaq’a ut li ch’och’. Una visión de la tierra, el mundo y la identidad a través de la tradición oral q’eqchi’ de Guatemala. Estudios de Cultura Maya. 2006;27:149–163. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Azurdia C. Plantas Mesoamericanas Subutilizadas en la Alimentación Humana: El Caso de Guatemala: Una Revisión del PASADO hacia una SOLUCIÓN Actual. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala; Guatemala City, Guatemala: 2016. p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala . Tqan Qayool. Vocabulario Awakateko. Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala; Guatemala City, Guatemala: 2001. p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala . K’ujb’ab’ yol tu ixil. Vocabulario ixil. 2st ed. Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala; Guatemala City, Guatemala: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 84.De la Cruz Tiburcio E., Gutiérrez Morales S., Jiménez García N., García Ramos C. Vocabulario Tepehua Español Tepehua. Tepehua de Tlachichilco. INALI-AVELI; Mexico City, Mexico: 2013. p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pérez Castro E. Recetario Mixe de Oaxaca. Volume 38 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Leonti M., Sticher O., Heinrich M. Antiquity of medicinal plant usage in two Macro-Mayan ethnic groups (Mexico) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;88:119–124. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clark L.E. Vocabulario Popoluca de Sayula: Veracruz, México. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano; Tucson, AZ, USA: 1995. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clark L.E. Diccionario Popoluca de Oluta: Popoluca-Español, Español-Popoluca. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano; Tucson, AZ, USA: 1981. p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wichmann S. Diccionario Analítico del Popoluca de Texistepec. IIF Universidad nacional Autónoma de México; Mexico City, Mexico: 2002. p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alvarez-Quiroz V., Caso-Barrera L., Aliphat-Fernández M., Galmiche-Tejeda Á. Plantas medicinales con propiedades frías y calientes en la cultura Zoque de Ayapa, Tabasco, México. Boletín Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromáticas. 2017;16:428–454. [Google Scholar]

- 91.O’Connor L. Chontal de San Pedro Huamelula, Sierra Baja de Oaxaca. México. El Colegio de México; Mexico City, Mexico: 2014. p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Flores U.J. Mucho Gusto!: Gastronomía y Turismo Cultural en el Istmo de Tehuantepec. CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Millán S. El cuerpo de la Nube: Jerarquía y Simbolismo ritual en la Cosmovisión de un Pueblo Huave. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia; Mexico City, Mexico: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moctezuma Zamarrón J.L. El sistema Fonológico del Kickapoo de Coahuila Analizado Desde las Metodologías Distribucional y Funcional. INALI; Mexico City, Mexico: 2011. p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Medina M.A., Alcaraz Miranda M., Santiago Hernández V.G. Pérdida de la Identidad Culinaria: Caso de la Sierra alta de Sonora. UNAM y Asociación Mexicana de Ciencias para el Desarrollo Regional, A.C.; Mexico City, Mexico: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oseguera-Montiel A. La Persistencia de la Costumbre Pima. Interpretaciones Desde la Antropología Cognitiva. UAM, INAH y ENAH del Norte de México; Mexico City, Mexico: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Irigoyen-Rascón F., Paredes A. Tarahumara Medicine: Ethnobotany and Healing among the Rarámuri of Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press; Norman, OK, USA: 2015. p. 417. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bañuelos Flores N.B., Salido-Araiza P.L. Enredados con la sierra. Las plantas en las estrategias sostenibles de sobrevivencia del grupo indígena Guarijío/Makurawe de Sonora, México. Rev. Tecnol. Marcha. 2020;33:78–192. doi: 10.18845/tm.v33i1.3849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guerrero L. Jiak bwa’ame. Textos de la cocina yaqui. Tlalocan. 2011;16:117–146. doi: 10.19130/iifl.tlalocan.2009.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Benciolini M. Noches de trabajo y días de fiesta. Intercambios de comida en dos rituales coras (México) Anthropol. Food [Online] 2014;S9 doi: 10.4000/aof.7612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Medina Ávila J.R. Recetario Huichol de Nayarit. Volume 46 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Aguilar Meléndez A., Güemes Jiménez R. Apuntes del sistema alimentario de los nahuas de la Huasteca meridional: El chile como alimento indispensable de la vida. [(accessed on 10 May 2021)];Graffylia. 2020 4:60–79. Available online: http://rd.buap.mx/ojs-dm/index.php/graffylia/article/view/481. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Piñón Flores I. Recetario Indígena de Baja California. Volume 34 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Diana L.A. Del mar y del Desierto: Gastronomía Comcaac (seri). Ecoturismo y Pueblos Indígenas. Ediciones Ciad, A.C.; Mexico City, Mexico: 2012. p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Del Moral P., Siller V.A. Recetario Mascogo de Coahuila. Volume 51 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Prudente F.A. La Sazón de la Cocina Afromestiza de Guerrero. Volume 56 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Torres Cerdán R., Careaga Gutiérrez D.E. Recetario Afromestizo de Veracruz. Volume 13 Dirección General de Culturas Populares de CONACULTA; Mexico City, Mexico: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wahyuni Y., Ballester A.-R., Tikunov Y., de Vos R.C.H., Pelgrom K.T.B., Maharijaya A., Sudarmonowati E., Bino R.J., Bovy A.G. Metabolomics and molecular marker analysis to explore pepper (Capsicum sp.) biodiversity. Metabolomics. 2013;9:130–144. doi: 10.1007/s11306-012-0432-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rozin E. The Flavor-Principle Cookbook. Hawthorn; New York, NY, USA: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Katz E. Del frío al exceso de calor: Dieta alimenticia y salud en la Mixteca. In: Sesia P., editor. Medicina Tradicional, Herbolaria y Salud Comunitaria en Oaxaca. Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social y Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca; Oaxaca, México: 1992. pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rozin P., Schiller D. The nature and acquisition of a preference for chili pepper by humans. Motiv. Emot. 1980;4:77–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00995932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fiedor J., Burda K. Potential role of carotenoids as antioxidants in human health and disease. Nutrients. 2014;6:466–488. doi: 10.3390/nu6020466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sharma S.K., Vij A.S., Sharma M. Mechanisms and clinical uses of capsaicin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;720:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sousa A.M., Carro L., Velàzquez E., Albuquerque C., Silva L.R. Bioactive Compounds from Capsicum Annuum as Health Promoters. In: Silva L.R., Silva B.M., editors. Natural Bioactive Compounds from Fruits and Vegetables as Health Promoters: Part II. Bentham Books; Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: 2016. pp. 92–109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Batiha G.E.-S., Alqahtani A., Ojo O.A., Shaheen H.M., Wasef L., Elzeiny M., Ismail M., Shalaby M., Murata T., Zaragoza-Bastida A. Biological properties, bioactive constituents, and pharmacokinetics of some Capsicum spp. and capsaicinoids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:5179. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Acero-Ortega C., Dorantes-Alvarez L., Hernández-Sánchez H., Gutiérrez-López G., Aparicio G., Jaramillo-Flores M.E. Evaluation of phenylpropanoids in ten Capsicum annuum L. varieties and their inhibitory effects on Listeria monocytogenes Murray, Webb and Swann Scott A. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2005;11:5–10. doi: 10.1177/1082013205050902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rakhsandehroo E., Asadpour M., Jafari A., Malekpour S.H. The effectiveness of Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Punica granatum flower and Capsicum annuum extracts against Parascaris equorum infective larvae. İstanbul Üniversitesi Veteriner Fakültesi Dergisi. 2016;42:132–137. doi: 10.16988/iuvfd.2016.91882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.BDMTM Biblioteca Digital de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana; 2009. [(accessed on 10 May 2021)]. Available online: http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/

- 119.Martínez-Torres H.L. Master’s Thesis. Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo; Montecillo, Texcoco, Mexico: 2007. Etnobotánica del Chile Quipín (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum) en la Sierra Gorda y Semidesierto de Querétaro. [Google Scholar]

- 120.López Austin A. Textos Acerca de las Partes del Cuerpo Humano y de las Enfermedades y Medicinas en los “Primeros Memoriales de Sahagún”. [(accessed on 10 May 2021)]. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3722897. [PubMed]

- 121.Bañuelos N., Salido P.L., Gardea A. Etnobotánica del chiltepín: Pequeño gran señor en la cultura de los sonorenses. Estud. Soc. 2008;16:177–205. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Andrade-Cetto A. Ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants from Tlanchinol, Hidalgo, México. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Magaña Alejandro M.A., Gama Campillo L.M., Mariaca Méndez R. El uso de las Plantas Medicinales en las Comunidades Maya-Chontales de Nacajuca, Tabasco, México. [(accessed on 5 May 2021)]. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-27682010000100011.

- 124.Cook S. The Forest of the Lacandon Maya: An. Ethnobotanical Guide. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2016. p. 402. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Paul B.D., McMahon C. Mesoamerican bonesetters. In: Huber B.R., Sandstrom A.R., editors. Mesoamerican Healers. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX, USA: 2001. pp. 243–269. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Olko J., Madajczak J. An animating principle in confrontation with christianity? de(re)constructing the Nahua “soul”. Anc. Mesoam. 2019;30:75–88. doi: 10.1017/S0956536118000329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Canul H.C. Cuerpo, alma y carne de la lengua maya. Vitalidad lingüística: Desde la lengua maya, a lo maya y con lo maya. Rev. Can. Estud. Hispánicos. 2014;39:213–237. doi: 10.18192/rceh.v39i1.1678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lorente Fernández D. Medicina indígena y males infantiles entre los nahuas de texcoco: Pérdida de la guía, caída de mollera, tiricia y mal de ojo. Anales de Antropol. 2015;49:101–148. doi: 10.1016/S0185-1225(15)30005-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mata-Pinzón S., Pérez-Ortega G., Reyes-Chilpa R. Plantas medicinales para el tratamiento del susto y mal de ojo. Análisis de sus posibles efectos sobre el sistema nervioso central por vía transdérmica e inhalatoria. Rev. Etnobiología. 2018;16:30–47. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Geck M.S., Cabras S., Casu L., Reyes García A.J., Leonti M. The taste of heat: How humoral qualities act as a cultural filter for chemosensory properties guiding herbal medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;198:499–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Laughlin R.M. The Huastec. Handb. Middle Am. Indians. 1969;7:298–311. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Corona de la Peña L.E., Martínez Miranda E.P. Uso ritual del chile ayuuk (mixe) In: Aguilar-Meléndez A., Vásquez-Dávila M.A., Katz E., Hernández C.M.R., editors. Los Chiles Que le DAN SABOR al Mundo. Contribuciones Multidisciplinarias. Universidad Veracruzana, y el Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo (IRD, Francia); Xalapa, Veracruz, México: 2018. pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sault N. Los Chiles Que le Dan Sabor al Mundo. Contribuciones Multidisciplinarias, Aguilar-Meléndez, A., Vásquez-Dávila, M.A., Katz, E., Hernández Colorado, M.R., Eds. Universidad Veracruzana, Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo (IRD, Francia); Xalapa, Veracruz, México: 2018. Chiles que arden: El rojo picante que protege y sana en Oaxaca; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Masood E. The battle for the soul of biodiversity. Nature. 2018;560:423–426. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05984-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Alonso-Castro A.J., Villarreal M.L., Salazar-Olivo L.A., Gomez-Sanchez M., Dominguez F., Garcia-Carranca A. Mexican medicinal plants used for cancer treatment: Pharmacological, phytochemical and ethnobotanical studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133:945–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Schmiedel U., Araya Y., Bortolotto M.I., Boeckenhoff L., Hallwachs W., Janzen D., Kolipaka S.S., Novotny V., Palm M., Parfondry M., et al. Contributions of paraecologists and parataxonomists to research, conservation, and social development. Conserv. Biol. 2016;30:506–519. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Nabhan G.P. Ethnobiology for the Future. Linking Cultural and Ecological Diversity. The University of Arizona Press; Tucson, AZ, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.